Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) has been associated with several human cancers, including cervical cancer, vulvar cancer, vaginal and anal cancer, and a subset of head and neck cancers. The identification of HPV as an etiological factor for HPV-associated malignancies creates the opportunity for the control of these cancers through vaccination. Currently, the preventive HPV vaccine using HPV virus-like particles has been proven to be safe and highly effective. However, this preventive vaccine does not have therapeutic effects, and a significant number of people have established HPV infection and HPV-associated lesions. Therefore, it is necessary to develop therapeutic HPV vaccines to facilitate the control of HPV-associated malignancies and their precursor lesions. Among the various forms of therapeutic HPV vaccines, DNA vaccines have emerged as a potentially promising approach for vaccine development due to their safety profile, ease of preparation and stability. However, since DNA does not have the intrinsic ability to amplify or spread in transfected cells like viral vectors, DNA vaccines can have limited immunogenicity. Therefore, it is important to develop innovative strategies to improve DNA vaccine potency. Since dendritic cells (DCs) are key players in the generation of antigen-specific immune responses, it is important to develop innovative strategies to modify the properties of the DNA-transfected DCs. These strategies include increasing the number of antigen-expressing/antigen-loaded DCs, improving antigen processing and presentation in DCs, and enhancing the interaction between DCs and T cells. Many of the studies on DNA vaccines have been performed on preclinical models. Encouraging results from impressive preclinical studies have led to several clinical trials.

Keywords: antigen-presenting cell, dendritic cell, DNA vaccine, HPV

Introduction to human papillomavirus vaccination

Association of human papillomavirus with human cancers

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases in the world and is the etiologic agent in approximately 5% of all cancer cases worldwide [1], including cervical cancer and a subset of anal, vaginal, vulval, penile, and head and neck cancers [2]. Among HPV-associated cancers, cervical cancer is the second largest cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide [1] and is primarily caused by HPV infection, with HPV DNA present in 99.7% of cervical cancers [3]. More than 100 HPV genotypes have been identified and are classified into low- or high-risk types, depending on their propensity to cause cancer [4]. High-risk types, such as HPV-16 and HPV-18, are the most frequent HPV types associated with cervical cancer. High-risk HPV types are frequently associated with squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix, also called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) precursor lesions of cervical cancer [5].

Molecular biology of HPV

Human papillomavirus has a circular dsDNA genome containing approximately 8000 bp and encoding two classes of proteins: early (E) proteins and late (L) proteins. The early proteins regulate viral DNA replication (E1 and E2), viral RNA transcription (E2), cytoskeletal reorganization (E4) and cellular transformation (E5, E6 and E7), whereas the late proteins (L1 and L2) are structural components of the viral capsid. The expression of each of the HPV viral proteins is tightly regulated and associated with the differentiation state of infected epithelial cells. E2 is the master regulator that controls the expression of all the other viral genes, and is particularly involved in the repression of E6 and E7. The viral oncogenes E6 and E7 are responsible for cellular transformation. In almost all cases of cervical cancer, the HPV genome integrates into the host chromosomal DNA, leading to the disruption of the viral E2 gene. Since E2 is a transcriptional repressor of E6 and E7, loss of E2 leads to constitutive expression of E6 and E7 genes. The uncontrolled expression of E6 and E7 proteins disrupts normal cell-cycle regulation by interacting with p53 and retinoblastoma (Rb), thereby prolonging the cell cycle and suppressing apoptosis, contributing to the progression of HPV-associated cervical cancer [6].

Currently available preventive HPV vaccines

The understanding of HPV biology is important for vaccine development. In order to generate protective humoral immune responses, it is critical to develop vaccines that are capable of neutralizing the HPV virus by targeting L1 and/or L2 HPV viral capsid proteins. It has been shown that cells transfected with the gene encoding HPV L1 capsid protein are capable of assembling into HPV virus-like particles (VLPs). Furthermore, vaccination with animal papillomavirus VLPs is capable of inducing neutralizing antibodies, leading to protective immunity against papillomavirus infection in preclinical models [5,7]. Recently, a quadrivalent HPV L1 VLP recombinant vaccine called Gardasil® was developed by Merck (NJ, USA) and has been approved by the US FDA [201,202]. This vaccine protects against four of the most medically relevant HPV genotypes: HPV-16 and HPV-18 for cervical cancer, and HPV-6 and HPV-11 for benign genital warts. HPV-16 and -18 account for approximately 70–75% of all cervical cancers. Gardasil has been extremely successful in inducing nearly complete protection from persistent HPV infection and CIN lesions associated with these four HPV genotypes. A similar vaccine developed by GlaxoSmithKline that contains HPV-16 and -18 (Cervarix®) is available in European countries, and may be available in the US market soon. These preventive HPV vaccines are well tolerated, highly immunogenic and capable of generating high titers of neutralizing antibody to the HPV types included in the vaccine, thus inducing protection from persistent HPV injection and HPV-related lesions [8–10]. There is also some cross-protection with other HPV types not included in the vaccine, such as HPV-31 and -45, thus leading to protection against up to approximately 80% of cervical cancers [11].

These vaccines have also been shown to be effective over a 5-year period [9,11]. Furthermore, Phase III trials employing the quadrivalent L1 VLP vaccine against HPV-6, -11, -16 and -18 have been shown to reduce the incidence of high-grade CIN related to HPV-16 or -18 [12], as well as HPV-associated anogenital diseases [10], compared with those in the placebo-treated groups. The employment of adjuvants may also influence the level and length of humoral immune response generated by L1 VLP vaccines. For example, a recent study using L1 VLPs formulated with AS04 adjuvants (3-O-deacyl-4′-monophosphoryl lipid A and aluminum salt) has been shown to generate enhanced humoral and memory B-cell immunity compared with formulations with aluminum salt alone [13].

Necessity for HPV therapeutic vaccines

Although preventive vaccines are safe and highly effective in preventing HPV infection, it is important to develop therapeutic HPV vaccines to facilitate the control of HPV-associated malignancies. Several key factors highlight the need for the development of therapeutic vaccines for the control of HPV-associated malignancies. First, the currently available preventive HPV vaccines are relatively expensive and require appropriate facilities for storage; thus, they are unlikely to be available soon to third-world countries, where most cases of cervical cancer occur. Therefore, the incidence of cervical cancer and its associated precursor lesions are not expected to be significantly reduced in these countries in the next few decades. Second, since HPV-infected basal epithelial cells and cervical cancer cells do not express detectable levels of capsid antigen (L1 and/or L2), preventive vaccines are unlikely to be effective in the elimination of pre-existing infection and HPV-related cancer [14]. This is a serious concern, since there is a considerable burden of HPV infections worldwide. Third, it is estimated that it would take at least 20 years from the implementation of mass vaccination for preventive vaccines to impact the cervical cancer rates owing to the significant prevalence of populations with existing HPV infections and the slow process of carcinogenesis. Thus, in order to accelerate the control of cervical cancer and treat currently infected patients, it is important to continue the development of therapeutic vaccines against HPV.

HPV E6 & E7 antigens as ideal targets for therapeutic vaccine development

The major factor involved in the design of therapeutic vaccines is the choice of target antigen. Quite different from the preventive HPV vaccines that target HPV capsid proteins, therapeutic HPV vaccines should focus on HPV viral antigens that are constitutively expressed in HPV-associated malignancies and their precursor lesions. In this regard, the HPV E6 and E7 proteins represent potentially ideal targets for therapeutic vaccine development. Not only are E6 and E7 essential for transformation, they are also coexpressed in HPV-infected cells but not in normal cells [15]. Furthermore, HPV E6 and E7 are completely foreign antigens and thus there is no issue of immune tolerance. Thus, E6 and E7 have become popular target antigens for therapeutic HPV vaccine development [16].

Different forms of therapeutic HPV vaccination

There are a number of therapeutic vaccine approaches, mainly targeting E6 and E7, that have been tested in preclinical and clinical trials, such as peptide or protein-based vaccines, live vector vaccines, DNA vaccines, cell-based vaccines and combined approaches. In general, the efficacy of these various vaccination approaches also depends on the method of delivery of the vaccines [16].

Various forms of therapeutic vaccines have been developed and each has its own advantages and disadvantages. For example, peptide-based therapeutic vaccines are stable, easily produced and safe [17,18]. However, they have low immunogenicity and therefore require adjuvants such as cytokines, chemokines, costimulatory molecules or Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands. Another drawback with respect to peptide-based vaccines is that these vaccines are MHC restricted (i.e., a particular peptide may not be effective at inducing cell-mediated immunity in individuals with different MHC class I molecules). Nevertheless, recent studies have demonstrated the employment of HPV long peptide-based vaccines for the generation of effective antigen-specific T-cell immunity [19–21].

Protein vaccines, on the other hand, have the ability to bypass MHC restriction since they contain all possible MHC class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes of the antigen [22–24]. However, protein vaccines are weakly immunogenic and usually induce a better antibody response than the CTL response [25,26]. Viral and bacterial vectors, especially those that are able to replicate in the host, are highly immunogenic and can generate strong humoral and cell-mediated immune responses [27–30]. However, there are safety concerns that need to be considered, especially in cancer patients with weakened immune systems. Another potential concern is the prevalence of pre-existing vector immunity that may decrease the efficacy of the vaccine and inhibit repeated vaccination. The dendritic cell (DC)-based vaccine approach involves the pulsing of DCs with E7 peptides or the transduction of DCs with DNA, RNA or viral vectors encoding E7. Presentation of HPV E7 peptides to the immune system by DCs is a promising method for circumventing tumor-mediated immunosuppression [31,32]. However, the preparation of DCs is labor intensive, costly and requires individual cell processing. Some of these types of therapeutic HPV vaccines have been tested in clinical trials [33].

Therapeutic HPV vaccines employing naked DNA vectors

DNA vaccines have emerged as an attractive approach for the development of therapeutic HPV vaccines. DNA vaccines generate effective CTL and antibody responses by delivering foreign antigen to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that stimulate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Compared with live viral or bacterial vectors, naked DNA plasmid vaccines are relatively safe and can be administered easily. Furthermore, DNA vaccines are easy to prepare on a large scale at high purity and stability, and can be engineered to express tumor antigenic peptides or proteins [34,35]. In addition, DNA enables the prolonged expression of antigens and enhancement of immunologic memory. Using DNA vaccines to express proteins bypasses MHC restriction and can thus be applicable to a wide variety of patients with different MHC class I molecules. DNA vaccines can also be repeatedly administered to the same patient safely and effectively, unlike live vector vaccines.

DNA vaccines are, however, limited by their low immunogenicity because DNA lacks cell-type specificity. Furthermore, DNA lacks the intrinsic ability to amplify or spread to surrounding cells in vivo. The potency of DNA vaccines can be enhanced by targeting DNA-encoding antigens to professional APCs and by modifying the properties of antigen-expressing APCs in order to boost vaccine-elicited immune responses.

DCs as central players for therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine development

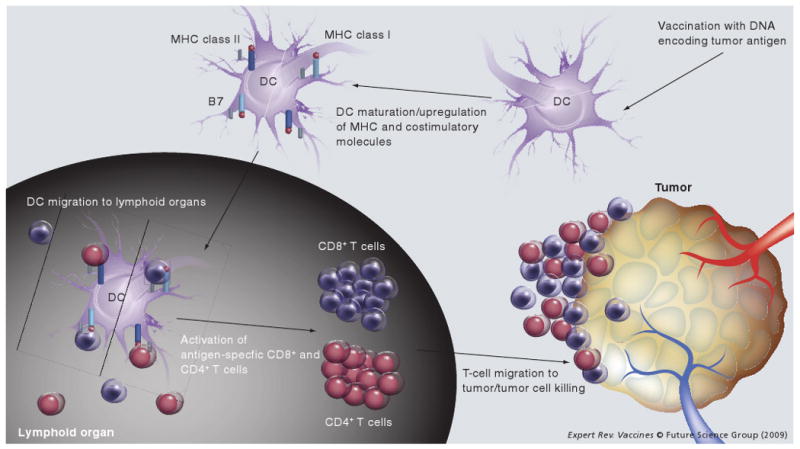

Professional APCs, especially DCs, are central players in the initiation of the adaptive immune response. Accumulating evidence suggests that cell-mediated immunity is critical for the control of viral infections and malignant tumors. It is now clear that DCs play a key role in the generation of antigen-specific antiviral and antitumor T-cell immune responses. The generation of CD8+ T cells allows for direct killing of viral-infected cells or tumors, while the generation of CD4+ T-helper cells leads to the augmentation of CD8+ immune responses. DCs are mainly responsible for the presentation of antigen to naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and for the activation of armed effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Immature DCs, which are located in peripheral tissues, efficiently uptake antigens, process the antigens into antigenic peptides, and load the peptides onto MHC class I and II molecules in order to present them on the cell surface. These immature DCs possess various types of surface receptors that enable them to respond to danger signals, such as bacterial or viral components or inflammatory cytokines, indicating the presence of an infection [36]. In response to a danger signal, the DCs undergo a maturation process, upregulating adhesion and costimulatory molecules, and transforming into efficient APCs and potent activators of T cells. These DCs then migrate to the lymphoid organs to select and stimulate antigen-specific T cells [36-38]. Figure 1 is a schematic diagram depicting the activation of DCs and migration to lymphoid organs where they activate antigen-specific T cells for tumor killing.

Figure 1. Role of dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy.

After administration of a DNA vaccine encoding tumor antigen, DCs express the antigen and undergo a maturation process, upregulating MHC class I and class II molecules as well as costimulatory molecules, such as B7. Antigen-expressing DCs then migrate to lymphoid organs, where they select for and stimulate antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to become effector T cells. These T cells then home to antigen-expressing tumors and effect tumor cell killing. DC: Dendritic cell.

In this article, we will describe various strategies to enhance the potency of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines through the modification of DCs. We will focus on strategies to:

Increase the number of antigen-expressing DCs

Improve antigen expression, processing and presentation in DCs

Enhance DC and T-cell interactions to augment vaccine-elicited T-cell immune responses

In addition, we will discuss the various therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine clinical trials employing these strategies.

Strategies to enhance the potency of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines

Increasing the number of antigen-expressing and/or antigen-loaded DCs

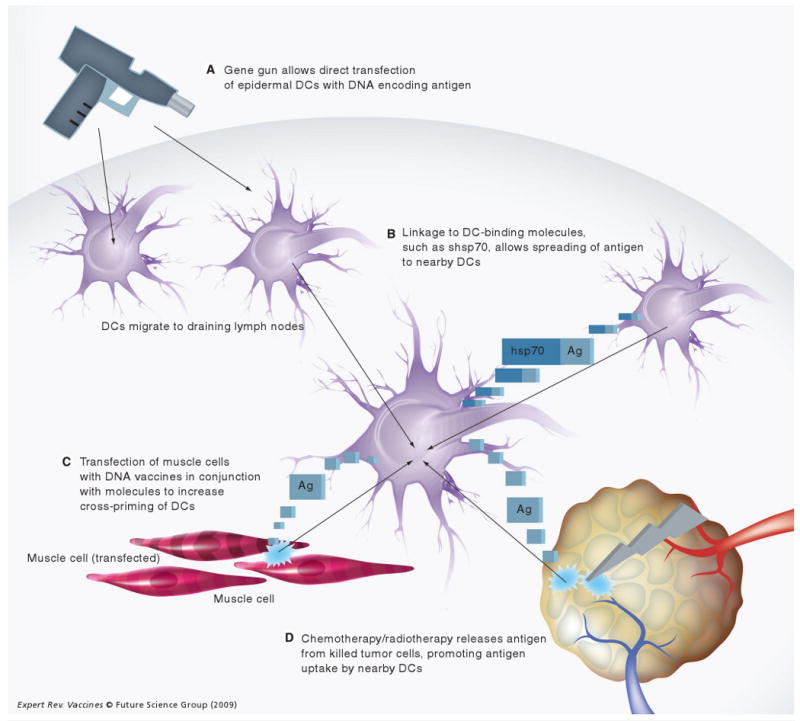

Several strategies have been developed to improve therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine potency by increasing the number of antigen-expressing and/or antigen-loaded DCs. Figure 2 summarizes the various strategies to increase the number of antigen-expressing and/or antigen-loaded DCs.

Figure 2. Strategies to increase the number of antigen-loaded/antigen-expressing DCs.

(A) Gene gun administration allows direct gene transfection of large numbers of epidermal DCs. (B) Vaccination with DNA encoding antigen linked to DC-binding molecules, such as shsp70 or Flt-3L, can lead to the expression of fusion constructs that are targeted to other DCs. (C) Transfection of muscle cells with DNA vaccines along with DNA-encoding allogeneic MHC class I DNA leads to immune-mediated destruction of transfected muscle cells and release of antigen for uptake by nearby DCs. (D) Administration of chemotherapeutic drugs (such as cisplatin or bortezomib) or radiotherapy can lead to tumor-cell killing and release of antigen for uptake by nearby DCs.

Ag: Antigen; DC: Dendritic cell; Flt-3L: Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3-ligand; hsp70: Heat-shock protein 70; shsp70: Secreted form of heat-shock protein 70.

Intradermal administration of DNA vaccines via gene gun as an efficient route for the delivery of DNA to DCs

One strategy for increasing antigen-expressing DC populations is to find convenient and effective routes for the delivery of DNA vaccines directly into DCs in vivo. To date, DNA vaccines have been most commonly administered either via the intramuscular or intradermal route [35]. Among the previously explored routes of DNA administration, intradermal vaccination via gene gun represents one of the most efficient methods for delivering DNA directly into DCs. The gene gun can deliver DNA-coated gold particles into Langerhans cells and/or dermal DCs in vivo [39]; these cells then mature and migrate to the lymphoid organs for T-cell priming [40]. In addition, gene gun immunization is significantly more dose efficient than intramuscular or subcutaneous injection [35,41]. Thus, the intradermal administration of DNA by gene gun allows us to test several strategies that require the delivery of DNA directly into DCs (Figure 2A). We have used this system to modify the properties of DCs to enhance DNA vaccine potency [42].

Electroporation as an efficient method for improving cellular DNA uptake to increase the number of antigen-expressing DCs

Once DNA vaccines have been delivered, however, their potency may be limited by inefficient cellular DNA uptake in situ. The employment of electroporation, a technique widely used to improve in vitro gene transfection, can potentially facilitate the uptake and expression of DNA by target cells in vivo and lead to an increase in the number of antigen-expressing DCs, augmenting vaccine-elicited immune responses. Several reports have demonstrated improved antigen expression and enhanced HPV DNA vaccine-elicited antigen-specific immune responses by electroporation in vivo [43,44]. Thus, electroporation may represent a strategy for overcoming the barrier of limited DNA transfection efficiency after the delivery of HPV DNA vaccines.

Intercellular antigen spreading as a strategy to increase the number of antigen-expressing DCs

The potency of DNA vaccines is still limited by the inability of naked DNA to naturally amplify and spread among DCs in vivo. This limitation can potentially be overcome by promoting the spread of encoded antigen from transfected cells to DCs. Linkage of antigen to proteins capable of intercellular transport has been shown to facilitate the spread of encoded antigen. For example, we have previously employed the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) tegument protein VP22 for our DNA vaccine development. When HSV-1 VP22 is linked to thymidine kinase [45], cytosine deaminase [46], p53 [47] or green fluorescent protein (GFP) [48], it has been shown to distribute these proteins to the nuclei of surrounding cells. A fusion gene consisting of VP22 linked to a model antigen HPV-16 E7 was demonstrated to dramatically increase the number of E7-expressing DCs in the lymph nodes of mice [49], as well as enhance E7-specific long-term memory CD8+ T-cell immune responses and antitumor effects against E7-expressing tumor cells [49,50]. Similarly, HSV-1 VP22 has been employed in a DNA vaccine to enhancing vaccine-elicited immune responses against HPV-16 E6 [51], as well as influenza nucleoprotein antigen [52].

Two other proteins with some homology to VP22, bovine herpesvirus VP22 (BVP22) and Marek's disease virus VP22 (MVP22), have also been shown to be capable of intercellular spreading and transport [53–56]. We have shown that vaccination with a fusion gene consisting of MVP22 linked to HPV-16 E7 enhances E7-specific CD8+ T-cell responses and antitumor effects in mice relative to immunization with wild-type E7 DNA [57].

Some concerns are raised that the intercellular trafficking ability of VP22 may potentially be attributed to fixation artifacts [58]. For example, one group found that transfection of mammalian cells with DNA encoding HSV-1 VP22 fused to enhanced GFP (EGFP) did not lead to increased intercellular spread of the fusion protein in vitro, but could lead to significantly enhanced production of EGFP-specific antibodies in mice vaccinated with this construct [59]. However, the transport properties of VP22 without fixation have been demonstrated [60]. In particular, binding and transport of an RNA (Us8.5-EGFP) into surrounding cells by VP22 without fixation has been shown [61]. Since no intercellular transport of Us8.5-EGFP mRNA was observed in the absence of VP22, this study supports the conclusion that VP22 can move between cells. To date, the ability of VP22 to bind and transport non-Us8.5-EGFP mRNA has not been shown. However, if these issues are addressed, it is possible that in the future, coadministration of DNA encoding VP22 and DNA encoding the antigen of interest may represent a method for the distribution of antigen to surrounding cells.

Linkage of antigen to molecules capable of binding to DCs as a method to target antigen to DCs

Another strategy to increase the number of antigen-expressing or antigen-loaded DCs is the linkage of antigen to molecules that target the antigen to the surface of DCs in the context of DNA vaccines (Figure 2B). For example, DNA vaccines encoding antigen linked to a secreted form of heat-shock protein (hsp)70, which bind to scavenger receptors on the surface of DCs, such as CD91, may represent an effective method for targeting linked antigen to DCs and enhancing antigen-specific immunity [62–64]. We have also shown that linkage of antigen to the Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand can also target antigen to DCs; a chimeric Flt–3L–E7 fusion gene can significantly improve CTL responses in mice compared with vaccination with wild-type E7 DNA [65].

Coadministration of DNA encoding allogeneic MHC class I molecules with DNA vaccines to enhance cross-priming

Intramuscular administration of DNA vaccines can lead to the generation of antigen-specific immune responses through cross-priming mechanisms. Therefore, a strategy capable of causing the destruction of APCs and enhancing cross-priming would lead to improved antigen-specific immune responses. Kang et al. have recently shown that the coadministration of a DNA vaccine in conjunction with DNA encoding an allogeneic MHC molecule could significantly enhance the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses, as well as antitumor effects against an E7-expressing tumor, TC-1, in C57BL/6 tumor-bearing mice (Figure 2C) [Kang TH, Chung J-Y, Monie SI et al., Submitted manuscript]. Kang et al. also showed that the coadministration of allogeneic MHC class I molecules led to an increase in the number of infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes and CD11b/c+ APCs at the injection site. The presence of APCs in the injection site raises the possibility that cross-priming may occur in the local environment in the vicinity of antigen-expressing cells. It has been shown that DCs can be recruited to the local tissues for cross-priming of CD8+ T cells [66]. Thus, it is plausible that the inflammation generated by the coadministration of allogeneic MHC class I DNA may lead to the recruitment of APCs, leading to cross-priming in the local muscle tissue. This suggests that intramuscular coadministration of DNA encoding allogeneic MHC class I can further improve the antigen-specific immune responses as well as antitumor effects generated by DNA vaccines through the induction of apoptosis in transfected cells, resulting in the enhancement of cross-priming mechanisms.

Employment of chemotherapy/radiation-induced apoptotic cell death to increase the number of antigen-loaded DCs

Coadministration of DNA vaccines with chemotherapeutic agents in the presence of an established HPV-associated tumor can promote the release of HPV antigens from apoptotic tumor cells. This can potentially facilitate the uptake of antigen by local DCs and subsequent cross-presentation of this antigen by DCs, resulting in the enhancement of the immune responses induced by DNA vaccines. For example, Kang et al. have recently shown that the chemotherapeutic agent epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG), a chemical derived from green tea, could induce tumor cellular apoptosis and enhance the tumor antigen-specific T-cell immune responses elicited by DNA vaccination [67]. Furthermore, the combination of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines with several other chemotherapeutic agents has also been shown to significantly enhance antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses in vaccinated mice compared with HPV DNA vaccination alone. For example, Tseng et al. have previously demonstrated that pretreatment of mice with chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin [68], bortezomib [69] or death receptor-5 [70], or treatment with low-dose radiation [71] can significantly enhance the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses induced by HPV DNA vaccination. The observed enhancement of E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses is most likely related to apoptotic tumor cell death caused by treatment with these agents. Thus, the combination of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccination with chemotherapeutic agents that cause apoptotic tumor cell death would generate significantly enhanced E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses, resulting in potent antitumor effects (Figure 2D). It may be of interest to explore whether other chemotherapeutic agents could exhibit similar synergistic effects when combined with DNA vaccines.

Improving HPV antigen expression, processing & presentation in DCs

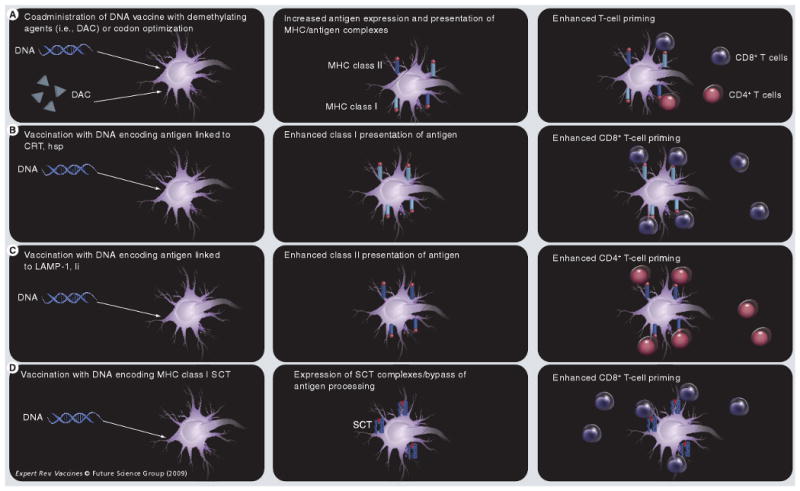

Several strategies have been employed to improve HPV DNA vaccine potency through the enhancement of antigen expression, processing and presentation in DCs (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Strategies to enhance antigen processing/presentation in dendritic cells.

(A) Coadministration of DNA vaccines with demethylating agents, such as DAC, or codon optimization can lead to increased expression of antigen in DCs, and thus enhanced antigen presentation and subsequent T-cell priming. (B) Administration of DNA-encoding antigen linked to CRT or hsp can target antigen directly to the endoplasmic reticulum and facilitate class I presentation of antigen, while (C) administration of DNA encoding antigen linked to LAMP-1 or Ii chain targets antigen to the class II presentation pathway. (D) Vaccination with DNA encoding MHC class I SCT enables bypassing of antigen processing and direct presentation of MHC class II antigen complexes on the cell surface.

CRT: Calreticulin; DAC: 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine; DC: Dendritic cell; hsp: Heat-shock protein; LAMP-1: Lysosome-associated membrane protein 1; Ii: MHC class II-associated invariant chain; SCT: Single-chain trimer.

Codon optimization as a strategy to enhance antigen expression in DCs

Codon optimization has emerged as an important strategy to enhance the expression of encoded HPV antigens in DCs (Figure 3A). This technique involves the modification of antigenic gene sequences by the replacement of codons that are rarely recognized by cellular protein synthesis machinery with more commonly recognized codons. This strategy can enhance the translation of HPV DNA vaccines in DCs. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the immunization of mice with codon-optimized HPV-16 E6 DNA generated stronger E6-specific immune responses than the vaccination of mice with wild-type E6 DNA [72,73].

Employment of demethylating agents to increase the expression of HPV antigens encoded by the DNA vaccine

Another strategy to improve HPV DNA vaccine potency is to enhance the level of expression of the antigen encoded in the vaccine [74]. Methylation of CpG islands in the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter regions has been shown to lead to silencing of gene expression [75,76]. This silencing would significantly affect the expression of the encoded antigen in HPV DNA vaccines, since most DNA vaccines use expression vectors containing CMV promoters. One strategy by which to overcome the limitation of gene silencing by DNA methylation is the employment of demethylating agents, such as 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (DAC). The nucleotide analogue DAC has been shown to inhibit DNA methyltransferase, resulting in the reactivation of several methylation-silenced genes [77–79]. Lu et al. have recently shown that therapeutic HPV DNA vaccination in combination with DAC would lead to the upregulation of E7 antigen expression, resulting in improved DNA vaccine potency (Figure 3A) [80]. We found that pretreatment with DAC led to increased E7 DNA expression, leading to enhanced E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses as well as the antitumor effects generated by the HPV E7 DNA vaccine. Thus, treatment with demethylating agents, such as DAC, may represent a potentially promising approach enhancing therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine potency.

Employment of intracellular targeting strategies to enhance MHC class I & II antigen presentation in DCs

With increased progress in our understanding of intracellular pathways for antigen presentation, we can now rely on this knowledge to develop strategies to enhance HPV DNA vaccine potency. Strategies to facilitate MHC class I antigen processing in DCs can lead to the activation of larger populations of CD8+ T cells and the generation of stronger antitumor or antiviral immunity. It has been demonstrated that linkage of HPV antigen to proteins that target the antigen for proteasomal degradation [81] or entry into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) can facilitate MHC class I presentation of linked antigen in DCs. For example, linkage of the HPV E7 antigen to Mycobacterium tuberculosis hsp70 [82], hsp60 [83], γ-tubulin [84], calreticulin (CRT) [85,86] or the translocation domain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A (ETA[dII]) [87] can significantly improve MHC class I presentation of HPV E7 antigen (Figure 3B). In a head-to-head comparison of HPV-16 E7 DNA vaccines employing intracellular targeting strategies, Kim et al. found that a DNA vaccine encoding E7 linked to CRT generated the greatest E7-specific CTL responses and antitumor effects against E7-expressing tumors in a preclinical model [88].

Strategies have also been developed to enhance MHC class II presentation of antigen encoded by DNA vaccines. It is increasingly evident that CD4+ helper T cells also play a major role in the priming of CD8+ T cells, as well as the generation of memory T cells [89]. Thus, strategies to facilitate MHC class II presentation of vaccine-encoded antigen can significantly improve the potency of DNA vaccines. For example, Wu et al. have demonstrated that the fusion of HPV-16 E7 with the sorting signal of lysosomal-associated membrane protein type 1 (LAMP-1) can target the E7 antigen to cellular endosomal/lysosomal compartments and facilitate the class II presentation of E7 (Figure 3C) [90]. This construct was tested in the context of a DNA vaccine and generated higher numbers of E7-specific CD4+ T cells, as well as greater E7-specific CTL activity, in mice than DNA vaccines encoding wild-type E7 alone [91].

Bypassing antigen processing as a method for generating stable antigen presentation in DCs

Recently, Huang et al. developed a MHC class I single-chain trimer (SCT) technology to bypass antigen processing and presentation. This strategy involves the linkage of the gene encoding an E6 antigenic peptide to β2-microglobulin and a MHC class I heavy chain, producing a single-chain construct encoding the peptide antigen fused to an MHC class I molecule. The expression of this construct within DCs may allow for stable presentation of the E6 antigenic peptide through MHC class I molecules on the cell surface. Huang et al. have shown that a DNA vaccine encoding a SCT encoding a HPV-16 E6 CTL epitope, β2-microglobulin and H-2Kb MHC class I heavy chain generated enhanced E6 peptide-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in vaccinated mice relative to immunization with DNA encoding wild-type HPV-16 E6 (Figure 3D) [92]. In addition, such strategies have also been applied to enhance DNA vaccine potency in the HPV E7 antigenic system.

Enhancing DC & T-cell interaction

Prolonging DC survival to enhance T-cell interaction

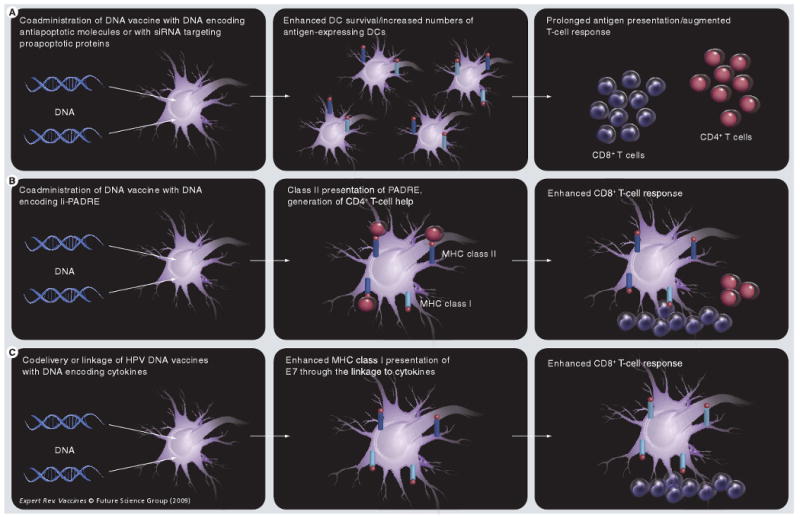

After T-cell priming, DCs may become targets of T-cell-mediated apoptosis. Thus, strategies to prolong the life of DCs may further increase the number of activated T cells. Kim et al. have developed a strategy to prolong DC survival using DNA encoding antiapoptotic proteins, including Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein and dominant-negative mutants (dn) of caspases, such as dn caspase-9 and dn caspase-8 (Figure 4A). These studies have indicated that coadministration of a DNA vaccine encoding HPV-16 E7 with DNA encoding any of these antiapoptotic factors could augment E7-specific CTL responses and elicit potent antitumor effects against E7-expressing tumors in vaccinated mice [93]. However, delivery of DNA encoding antiapoptotic proteins into cells raises concerns for cellular malignant transformation. The use of gene knockdown strategies, such as RNA interference targeting key proapoptotic proteins, may provide a novel method for accomplishing the same goal while alleviating the concern of oncogenicity. Thus, Kim et al. have shown that coadministration of a DNA vaccine encoding HPV-16 E7 with siRNA targeting the key proapoptotic proteins Bak and Bax can prolong the survival of transfected DCs and augment E7-specific CD8+ T-cell responses against E7-expressing tumors in mice [94]. These studies suggest that the prolongation of DC survival may represent an effective strategy for improving antigen presentation by DCs to T cells and for enhancing vaccine-elicited T-cell immune responses. It would be of interest to further explore coadministration of DNA vaccines with siRNA targeting other key proapoptotic proteins, such as caspase-8, caspase-9 and/or caspase-3, as a method to enhance DNA vaccine potency.

Figure 4. Strategies to enhance dendritic cell and T-cell interaction.

(A) Coadministration of DNA vaccines with DNA encoding antiapoptotic molecules (such as Bcl-xL) or with siRNA targeting proapoptotic proteins (such as Bak and Bax) can prolong DC survival, increasing the number of antigen-expressing DCs and augmenting antigen-specific T-cell responses. (B) Coadministration of DNA vaccines with DNA encoding Ii-PADRE leads to class II presentation of PADRE, which activates CD4+ T cells that provide help in generating CD8+ T-cell responses.

DC: Dendritic cell; E7: Early cellular transformation protein 7; HPV: Human papillomavirus; Ii: MHC class II-associated invariant chain; PADRE: Pan HLA-DR-binding epitope.

Induction of CD4+ T-cell help as a strategy for augmenting HPV DNA vaccine-elicited CD8+ T-cell responses

The activation of CD8+ T cells is dependent upon, and augmented by, T-cell help from CD4+ T cells. Thus, strategies to induce CD4+ T-helper cells at sites of CD8+ T-cell priming can potentially enhance CTL immune responses. Recently, Hung et al. developed a DNA vaccine strategy employing MHC class II-associated invariant chain (Ii) for enhancing CD4+ T-cell help, by improving class II presentation of antigen in DCs. In the ER, Ii binds with MHC class II molecules, and the class II-associated peptide (CLIP) region of Ii occupies the peptide-binding groove of the MHC molecule, preventing premature binding of antigenic peptides into the groove (for reviews, see [95,96]). In the endosomal/lysosomal compartments, CLIP is replaced by a peptide antigen, and the MHC class II molecule/antigenic peptide complex is then presented on the cell surface. By substituting the CLIP region of Ii with a desired epitope, the epitope can be efficiently presented through the MHC class II pathway in DCs for the stimulation of peptide-specific CD4+ T cells. Using this rationale, Hung et al. created a DNA vaccine encoding Ii with the CLIP region replaced with the pan HLA-DR binding epitope (PADRE) and showed that this DNA vaccine could elicit potent PADRE-specific CD4+ T-cell responses in vaccinated mice (Figure 4B) [97]. In addition, coadministration of this vaccine (termed Ii-PADRE) with DNA encoding HPV-16 E7 generated significantly greater CD8+ T-cell immune responses relative to coadministration of DNA encoding HPV-16 E7 with DNA encoding unmodified Ii [97]. This suggests a potentially effective vaccine strategy for CD4+ T-cell-mediated augmentation of CD8+ T-cell priming for potentiating DNA vaccines. Furthermore, the strategy to enhance CD4+ T-cell help can be used in conjunction with other strategies, such as strategies to prolong the life of DCs and/or other intracellular targeting strategies, to further enhance therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine potency, since these strategies are not mutually exclusive [98].

Employment of cytokines, costimulatory molecules & TLR ligands to enhance T-cell & DC activation

The stimulation of antigen-specific T cells by DCs during T-cell priming is dependent on two signals delivered by DCs to T cells. First, the appropriate peptide–MHC complexes on the surface of DCs must interact with T-cell receptors. Second, costimulatory molecules on the surface of DCs must stimulate their counterparts on T cells. Cytokines secreted by DCs may augment or even serve as the secondary costimulatory signal. Studies have shown that codelivery or linkage of HPV DNA vaccines with DNA encoding various cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-12, IL-18, or granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor can enhance vaccine- elicited immune responses (Figure 4C) [35]. For example, DNA vaccines encoding IL-2 linked to HPV-16 E7 antigen have been shown to generate enhanced E7-specific CTL responses and antitumor activity [99]. Furthermore, the immunogenicity of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines may also be enhanced by coadministration with sequence-optimized cytokines as genetic adjuvants [100].

Dendritic cell activation is a prerequisite to T-cell priming and the generation of antigen-specific immune responses. In the presence of ‘alert’ signals, such as TLR ligands or inflammatory cytokines, DCs are stimulated to mature and differentiate into potent activators of antigen-specific T cells [36]. The strength of the immune response elicited by DNA vaccines can thus be enhanced by strategies that provide alert signals and other maturation-inducing stimuli to DCs in order to facilitate DC activation. TLR ligands may also be useful for enhancing DNA vaccine potency through their actions on TLRs on the surface of DCs or intracellularly. It is now clear that TLRs on DCs play a crucial role in both innate and adaptive immune responses [101–103]. HPV DNA vaccines have been administered in conjunction with TLR ligands, which function as immunomodulators, leading to DC activation and resulting in enhanced vaccine-elicited immune responses [104]. It has also been shown that the expression of HPV-16 E6 and E7 can suppress the host immune response by deregulating the TLR9 transcript [105]. These immunomodulating agents improve antigen presentation by DCs. Topical immunotherapy with immunostimulatory agents shows significant potential for enhancing the potency of HPV DNA vaccines [104]. Furthermore, CpG motifs, which are bacterial-derived immunostimulatory gene sequences, can promote the growth and activation of transfected DCs via stimulation through TLR9 [106], and enhance DNA vaccine potency [107]. The employment of potent immunostimulatory adjuvants, such as TLR ligands – lipopolysaccharide, monophosphoryl lipid A, CpG DNA, polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid or muramylpeptides in combination with therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines – may lead to significant enhancements in HPV DNA vaccine potency [108].

Therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine clinical trials

Encouraging data from preclinical models have led to several therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine clinical trials. For example, a micro-encapsulated DNA vaccine encoding multiple HLA-A2-restricted E7-derived epitopes, termed ZYC-101 (ZYCOS, Inc., now acquired by MGI Pharma; MN, USA), has been tested in patients with CIN-2/3 lesions [109] and in patients with high-grade anal intraepithelial lesions [110]. The vaccine was well tolerated in both trials. A new version of the vaccine, termed ZYC-101a (ZYCOS, Inc., now acquired by MGI Pharma), encodes HPV-16 and -18 E6- and E7-derived epitopes, and was tested in a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted in a group of women with biopsy-confirmed CIN-2/3. The subjects received three intramuscular doses of ZYC-101a or placebo. The proportion of subjects who resolved was higher in ZYC-101a groups compared with the placebo but this difference was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, a population of women younger than 25 years of age was shown to resolve CIN-2/3 lesions more compared with women receiving the placebo [111].

For clinical translation, it is essential to address concerns regarding the potential for oncogenicity associated with the administration of E6 and E7 as DNA vaccines into the body. Thus, it is important to use attenuated (detox) versions of E6 and E7 that have been mutated. It has been demonstrated that a mutation at E7 position 24 and/or 26 will disrupt the Rb binding site of E7, abolishing the capacity of E7 to transform cells [112]. Furthermore, mutation at E6 positions 63 or 106 has been shown to destroy several HPV-16 E6 functions, preventing the mutated E6 protein from immortalizing human epithelial cells [113,114]. Additional strategies to alleviate concerns for oncogenicity include employment of a shuffled E7 molecule, in which sequences encoding regions of the E7 protein were rearranged and certain sequences were duplicated to maintain all possible T-cell epitopes [100,115,116].

DNA vaccines encoding a signal sequence linked to an attenuated form of HPV-16 E7 (with a mutation that abolishes the Rb binding site; E7detox) and fused to hsp70 (Sig/E7detox/hsp70) has been tested in Phase I trials on HPV-16-positive patients with high-grade CIN lesions at Johns Hopkins [117]. The trial design was a straight dose–escalation Phase I trial, testing a homologous DNA–DNA–DNA prime–boost vaccination regimen of three vaccinations per patient at three dose levels delivered intramuscularly at 1-month intervals, prior to standard therapeutic resection of remaining lesion 7 weeks after the last vaccination. No adverse or dose-limiting side effects were observed at any dose level of the DNA vaccine, and the vaccination was considered to be feasible and tolerable in patients with CIN-2/3 lesions. Another Phase I trial using the same naked DNA vaccine (Sig/E7detox/hsp70) is currently ongoing in HPV-16-positive patients with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [Gillison M, Pers. Comm.] at Johns Hopkins University. Likewise, no significant adverse effects have been observed in this study. Some of the DNA-treated patients developed appreciable E7-specific immune responses. A Phase I trial is currently being planned to assess the immunogenicity, safety, tolerability and efficacy of the Sig/E7detox/hsp70 DNA vaccine prime followed by boost with vaccinia expressing HPV-16 and -18 E6 and E7 antigens (TA-HPV construct) [118] in combination with locally applied TLR7 agonist, imiquimod, in patients with HPV-16-positive high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions to assess the ability of the immune effector cells to access and infiltrate the epithelial compartment of lesions [Trimble C, Pers. Comm.].

Another candidate DNA vaccine that is currently being prepared for clinical trials conducted at Johns Hopkins in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (AB, USA) is a DNA vaccine encoding CRT fused to HPV-16 E7 (E7detox) [Trimble C, Pers. Comm.]. Intradermal administration of the CRT/E7 DNA vaccine has been shown to generate significant E7 antigen-specific immune responses in preclinical models [85]. This therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine trial will be performed in HPV-16-positive patients with high-grade squamous intraepithelial (CIN-3) lesions using a PowderMed/Pfizer proprietary gene gun device ND-10, which is an individualized gene gun device suitable for clinical trials. This study aims to compare the gene gun administration with different routes of administration of the pNGVL4a-CRT/E7(detox) DNA, including intramuscular and intravaginal routes of delivery for their ability to generate E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses, as well as therapeutic effects against HPV-16-associated CIN-3 lesions. Another clinical study is currently being planned using the same DNA vaccine (pNGVL4a-CRT/E7 [detox]) administered intramuscularly following electroporation in patients with HPV-16-positive head and neck cancer [Pai S, Pers. Comm.]. In addition, clinical trials involving intramuscular administration of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines in conjunction with electroporation in patients with CIN-2/3 lesions have also been initiated [203].

Expert commentary & five-year view

The identification and characterization of high-risk HPV as a necessary causal agent for cervical cancer provides a promising possibility for the eradication of HPV-related malignancies. In the development of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines, we have discussed strategies to enhance HPV DNA vaccine potency by increasing the number of antigen-expressing DCs, improving antigen expression, processing and presentation in DCs, and enhancing DC and T-cell interaction, in order to augment vaccine-elicited T-cell immune responses. These strategies can potentially be combined to further enhance therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine potency. Furthermore, it is important for HPV therapeutic DNA vaccines to consider using strategies such as prime–boost regimens and/or combinations strategies using molecules that are capable of blocking the negative regulators on T cells to further enhance the T-cell immune responses. Moreover, increasing understanding of the molecular mechanisms that hinder immune attack in the tumor microenvironment will lead to the identification of novel molecular targets that can be blocked in order to enhance the therapeutic effect of HPV DNA vaccines. With continued efforts in the development of HPV therapeutic vaccines, we can foresee that HPV therapeutic DNA vaccines will emerge as a significant approach that can be combined with existing forms of therapy, such as chemotherapy and radiation, leading to effective translation from bench to bedside for the control of HPV-associated malignancies.

Key issues

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is an etiological factor for cervical cancer.

There is a necessity for the development of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are central players in therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine development.

-

Strategies to enhance the potency of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines are necessary. These include:

– Increasing the number of antigen-expressing and/or antigen-loaded DCs

– Improving HPV antigen expression, processing and presentation in DCs

– Enhancing DC and T-cell interaction

– Several therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine trials have recently been completed or are currently ongoing

Acknowledgments

This review is not intended to be an encyclopedic one, and the authors apologize to those not cited.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure: This work was supported by the NIH grants including the Cervical Cancer SPORE (P50 098252) and the 1RO1 CA114425. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Archana Monie, Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD, USA, Tel.: +1 410 502 8097, Fax: +1 443 287 4295, amonie1@jhmi.edu.

Shaw-Wei D Tsen, Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Chien-Fu Hung, Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD, USA and Department of Oncology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD, USA, Tel.: +1 410 502 8215, Fax: +1 443 287 4295, chung2@jhmi.edu.

T-C Wu, Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Cancer Research Building II Room 309, 1550 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21231, USA, Tel.: +1 410 614 3899, Fax: +1 443 287 4295, wutc@jhmi.edu and Department of Oncology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD, USA and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD, USA and Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD, USA.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoory T, Monie A, Gravitt P, Wu TC. Molecular epidemiology of human papillomavirus. J Formos Med Assoc. 2008;107:198–217. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roden R, Wu TC. How will HPV vaccines affect cervical cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:753–763. doi: 10.1038/nrc1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:342–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roden RB, Monie A, Wu TC. Opportunities to improve the prevention and treatment of cervical cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:490–503. doi: 10.2174/156652407781387127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, et al. Prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in young women: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre Phase II efficacy trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:271–278. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villa LL, Ault KA, Giuliano AR, et al. Immunologic responses following administration of a vaccine targeting human papillomavirus Types 6, 11, 16, and 18. Vaccine. 2006;24:5571–5583. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1928–1943. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM, et al. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.FUTURE II Study Group. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915–1927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giannini SL, Hanon E, Moris P, et al. Enhanced humoral and memory B cellular immunity using HPV16/18 L1 VLP vaccine formulated with the MPL/aluminium salt combination (AS04) compared to aluminium salt only. Vaccine. 2006;24:5937–5949. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiller JT, Castellsague X, Villa LL, Hildesheim A. An update of prophylactic human papillomavirus L1 virus-like particle vaccine clinical trial results. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 10):K53–K61. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crook T, Morgenstern JP, Crawford L, Banks L. Continued expression of HPV-16 E7 protein is required for maintenance of the transformed phenotype of cells co-transformed by HPV-16 plus EJ-ras. EMBO J. 1989;8:513–519. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung CF, Ma B, Monie A, Tsen SW, Wu TC. Therapeutic human papillomavirus vaccines: current clinical trials and future directions. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:421–439. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.4.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudolf MP, Man S, Melief CJ, Sette A, Kast WM. Human T-cell responses to HLA-A-restricted high binding affinity peptides of human papillomavirus type 18 proteins E6 and E7. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(3 Suppl):788S–795S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Burg SH, Ressing ME, Kwappenberg KM, et al. Natural T-helper immunity against human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) E7-derived peptide epitopes in patients with HPV16-positive cervical lesions: identification of 3 human leukocyte antigen class II-restricted epitopes. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:612–618. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1119>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welters MJ, Kenter GG, Piersma SJ, et al. Induction of tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell immunity in cervical cancer patients by a human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 long peptides vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:178–187. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, et al. Phase I immunotherapeutic trial with long peptides spanning the E6 and E7 sequences of high-risk human papillomavirus 16 in end-stage cervical cancer patients shows low toxicity and robust immunogenicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:169–177. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melief CJ, van der Burg SH. Immunotherapy of established (pre) malignant disease by synthetic long peptide vaccines. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:351–360. doi: 10.1038/nrc2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenstone HL, Nieland JD, de Visser KE, et al. Chimeric papillomavirus virus-like particles elicit antitumor immunity against the E7 oncoprotein in an HPV16 tumor model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1800–1805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng S, Frazer IH, Fernando GJ, Zhou J. Papillomavirus virus-like particles can deliver defined CTL epitopes to the MHC class I pathway. Virology. 1998;240:147–157. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schafer K, Muller M, Faath S, et al. Immune response to human papillomavirus 16 L1E7 chimeric virus-like particles: induction of cytotoxic T cells and specific tumor protection. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:881–888. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990611)81:6<881::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fausch SC, Da Silva DM, Eiben GL, Le Poole IC, Kast WM. HPV protein/peptide vaccines: from animal models to clinical trials. Front Biosci. 2003;8:S81–S91. doi: 10.2741/1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerard CM, Baudson N, Kraemer K, et al. Therapeutic potential of protein and adjuvant vaccinations on tumour growth. Vaccine. 2001;19:2583–2589. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunn GR, Zubair A, Peters C, Pan ZK, Wu TC, Paterson Y. Two Listeria monocytogenes vaccine vectors that express different molecular forms of HPV-16 E7 induce qualitatively different T cell immunity that correlates with their ability to induce regression of established tumors immortalized by HPV-16. J Immunol. 2001;167:6471–6479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin CW, Lee JY, Tsao YP, Shen CP, Lai HC, Chen SL. Oral vaccination with recombinant Listeria monocytogenes expressing human papillomavirus type 16 E7 can cause tumor growth in mice to regress. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:629–637. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jabbar IA, Fernando GJ, Saunders N, et al. Immune responses induced by BCG recombinant for human papillomavirus L1 and E7 proteins. Vaccine. 2000;18:2444–2453. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00550-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Revaz V, Benyacoub J, Kast WM, Schiller JT, De Grandi P, Nardelli-Haefliger D. Mucosal vaccination with a recombinant Salmonella typhimurium expressing human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) L1 virus-like particles (VLPs) or HPV16 VLPs purified from insect cells inhibits the growth of HPV16-expressing tumor cells in mice. Virology. 2001;279:354–360. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doan T, Herd KA, Lambert PF, Fernando GJ, Street MD, Tindle RW. Peripheral tolerance to human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein occurs by cross-tolerization, is largely Th-2-independent, and is broken by dendritic cell immunization. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2810–2815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murakami M, Gurski KJ, Marincola FM, Ackland J, Steller MA. Induction of specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses using a human papillomavirus-16 E6/E7 fusion protein and autologous dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1184–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alphs HH, Wu TC, Roden RB. Prevention and treatment of cervical cancer by vaccination. In: Giordano A, Bovicelli A, Kurman RJ, editors. Molecular Pathology of Gynecologic Cancer. Humana Press; NJ, USA: 2007. pp. 125–153. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donnelly JJ, Ulmer JB, Shiver JW, Liu MA. DNA vaccines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurunathan S, Klinman DM, Seder RA. DNA vaccines: immunology, application, and optimization. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:927–974. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guermonprez P, Valladeau J, Zitvogel L, Thery C, Amigorena S. Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:621–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Condon C, Watkins SC, Celluzzi CM, Thompson K, Falo LD., Jr DNA-based immunization by in vivo transfection of dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:1122–1128. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Porgador A, Irvine KR, Iwasaki A, Barber BH, Restifo NP, Germain RN. Predominant role for directly transfected dendritic cells in antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells after gene gun immunization. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1075–1082. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Payne LG, Fuller DH, Haynes JR. Particle-mediated DNA vaccination of mice, monkeys and men: looking beyond the dogma. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2002;4:459–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hung CF, Wu TC. Improving DNA vaccine potency via modification of professional antigen presenting cells. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2003;5:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan J, Harris K, Khan AS, Draghia-Akli R, Sewell D, Weiner DB. Cellular immunity induced by a novel HPV18 DNA vaccine encoding an E6/E7 fusion consensus protein in mice and rhesus macaques. Vaccine. 2008;26:5210–5215. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan J, Reichenbach DK, Corbitt N, et al. Induction of antitumor immunity in vivo following delivery of a novel HPV-16 DNA vaccine encoding an E6/E7 fusion antigen. Vaccine. 2009;27:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dilber MS, Phelan A, Aints A, et al. Intercellular delivery of thymidine kinase prodrug activating enzyme by the herpes simplex virus protein, VP22. Gene Ther. 1999;6:12–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wybranietz WA, Gross CD, Phelan A, et al. Enhanced suicide gene effect by adenoviral transduction of a VP22–cytosine deaminase (CD) fusion gene. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1654–1664. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phelan A, Elliott G, O'Hare P. Intercellular delivery of functional p53 by the herpesvirus protein VP22. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:440–443. doi: 10.1038/nbt0598-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elliott G, O'Hare P. Intercellular trafficking and protein delivery by a herpesvirus structural protein. Cell. 1997;88:223–233. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81843-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim TW, Hung CF, Kim JW, et al. Vaccination with a DNA vaccine encoding herpes simplex virus type 1 VP22 linked to antigen generates long-term antigen-specific CD8-positive memory T cells and protective immunity. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:167–177. doi: 10.1089/104303404772679977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hung CF, Cheng WF, Chai CY, et al. Improving vaccine potency through intercellular spreading and enhanced MHC class I presentation of antigen. J Immunol. 2001;166:5733–5740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peng S, Trimble C, Ji H, et al. Characterization of HPV-16 E6 DNA vaccines employing intracellular targeting and intercellular spreading strategies. J Biomed Sci. 2005;12:689–700. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saha S, Yoshida S, Ohba K, et al. A fused gene of nucleoprotein (NP) and herpes simplex virus genes (VP22) induces highly protective immunity against different subtypes of influenza virus. Virology. 2006;354:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harms JS, Ren X, Oliveira SC, Splitter GA. Distinctions between bovine herpesvirus 1 and herpes simplex virus type 1 VP22 tegument protein subcellular associations. J Virol. 2000;74:3301–3312. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3301-3312.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koptidesova D, Kopacek J, Zelnik V, Ross NL, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J. Identification and characterization of a cDNA clone derived from the Marek's disease tumour cell line RPL1 encoding a homologue of α-transinducing factor (VP16) of HSV-1. Arch Virol. 1995;140:355–362. doi: 10.1007/BF01309869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dorange F, El Mehdaoui S, Pichon C, Coursaget P, Vautherot JF. Marek's disease virus (MDV) homologues of herpes simplex virus type 1 UL49 (VP22) and UL48 (VP16) genes: high-level expression and characterization of MDV-1 VP22 and VP16. J Gen Virol. 2000;81(Pt 9):2219–2230. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-9-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mwangi W, Brown WC, Splitter GA, Zhuang Y, Kegerreis K, Palmer GH. Enhancement of antigen acquisition by dendritic cells and MHC class II-restricted epitope presentation to CD4+ T cells using VP22 DNA vaccine vectors that promote intercellular spreading following initial transfection. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:401–411. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hung CF, He L, Juang J, Lin TJ, Ling M, Wu TC. Improving DNA vaccine potency by linking Marek's disease virus type 1 VP22 to an antigen. J Virol. 2002;76:2676–2682. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2676-2682.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lundberg M, Johansson M. Is VP22 nuclear homing an artifact? Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:713–714. doi: 10.1038/90741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perkins SD, Hartley MG, Lukaszewski RA, Phillpotts RJ, Stevenson FK, Bennett AM. VP22 enhances antibody responses from DNA vaccines but not by intercellular spread. Vaccine. 2005;23:1931–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oliveira SC, Harms JS, Afonso RR, Splitter GA. A genetic immunization adjuvant system based on BVP22-antigen fusion. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1353–1359. doi: 10.1089/104303401750271002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sciortino MT, Taddeo B, Poon AP, Mastino A, Roizman B. Of the three tegument proteins that package mRNA in herpes simplex virions, one (VP22) transports the mRNA to uninfected cells for expression prior to viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8318–8323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122231699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trimble C, Lin CT, Hung CF, et al. Comparison of the CD8+ T cell responses and antitumor effects generated by DNA vaccine administered through gene gun, biojector, and syringe. Vaccine. 2003;21:4036–4042. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hauser H, Chen SY. Augmentation of DNA vaccine potency through secretory heat shock protein-mediated antigen targeting. Methods. 2003;31:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hauser H, Shen L, Gu QL, Krueger S, Chen SY. Secretory heat-shock protein as a dendritic cell-targeting molecule: a new strategy to enhance the potency of genetic vaccines. Gene Ther. 2004;11:924–932. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hung CF, Hsu KF, Cheng WF, et al. Enhancement of DNA vaccine potency by linkage of antigen gene to a gene encoding the extracellular domain of Flt3-ligand. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1080–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Le Borgne M, Etchart N, Goubier A, et al. Dendritic cells rapidly recruited into epithelial tissues via CCR6/CCL20 are responsible for CD8+ T cell crosspriming in vivo. Immunity. 2006;24:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kang TH, Lee JH, Song CK, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor immunity induced by DNA vaccination. Cancer Res. 2007;67:802–811. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tseng CW, Hung CF, Alvarez RD, et al. Pretreatment with cisplatin enhances E7-specific CD8+ T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity induced by DNA vaccination. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3185–3192. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tseng CW, Monie A, Wu CY, et al. Treatment with proteasome inhibitor bortezomib enhances antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity induced by DNA vaccination. J Mol Med. 2008;86:899–908. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0370-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tseng CW, Monie A, Trimble C, et al. Combination of treatment with death receptor 5-specific antibody with therapeutic HPV DNA vaccination generates enhanced therapeutic anti-tumor effects. Vaccine. 2008;26:4314–4319. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tseng CW, Trimble C, Zeng Q, et al. Low-dose radiation enhances therapeutic HPV DNA vaccination in tumor-bearing hosts. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;58(5):737–748. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0596-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin CT, Tsai YC, He L, et al. A DNA vaccine encoding a codon-optimized human papillomavirus type 16 E6 gene enhances CTL response and anti-tumor activity. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13(4):481–488. doi: 10.1007/s11373-006-9086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Samorski R, Gissmann L, Osen W. Codon optimized expression of HPV 16 E6 renders target cells susceptible to E6-specific CTL recognition. Immunol Lett. 2006;107:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pamer E, Cresswell P. Mechanisms of MHC class I – restricted antigen processing. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:323–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ochiai H, Harashima H, Kamiya H. Intranuclear disposition of exogenous DNA in vivo: silencing, methylation and fragmentation. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:918–922. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brooks AR, Harkins RN, Wang P, Qian HS, Liu P, Rubanyi GM. Transcriptional silencing is associated with extensive methylation of the CMV promoter following adenoviral gene delivery to muscle. J Gene Med. 2004;6:395–404. doi: 10.1002/jgm.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suzuki H, Gabrielson E, Chen W, et al. A genomic screen for genes upregulated by demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition in human colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2002;31:141–149. doi: 10.1038/ng892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu N, Wang M. Anticancer drug discovery targeting DNA hypermethylation. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:1350–1375. doi: 10.2174/092986708784567653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arai M, Imazeki F, Sakai Y, et al. Analysis of the methylation status of genes up-regulated by the demethylating agent, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:405–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu D, Hoory T, Monie A, Wu A, Wang MC, Hung CF. Treatment with demethylating agent, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine enhances therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine potency. Vaccine. 2009;27(32):4363–4369. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Massa S, Simeone P, Muller A, Benvenuto E, Venuti A, Franconi R. Antitumor activity of DNA vaccines based on the human papillomavirus-16 E7 protein genetically fused to a plant virus coat protein. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:354–364. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen CH, Wang TL, Hung CF, et al. Enhancement of DNA vaccine potency by linkage of antigen gene to an hsp70 gene. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1035–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huang CY, Chen CA, Lee CN, et al. DNA vaccine encoding heat shock protein 60 co-linked to HPV16 E6 and E7 tumor antigens generates more potent immunotherapeutic effects than respective E6 or E7 tumor antigens. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hung CF, Cheng WF, He L, et al. Enhancing major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation by targeting antigen to centrosomes. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2393–2398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cheng WF, Hung CF, Chai CY, et al. Tumor-specific immunity and antiangiogenesis generated by a DNA vaccine encoding calreticulin linked to a tumor antigen. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:669–678. doi: 10.1172/JCI12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim D, Gambhira R, Karanam B, et al. Generation and characterization of a preventive and therapeutic HPV DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 2008;26:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hung CF, Cheng WF, Hsu KF, et al. Cancer immunotherapy using a DNA vaccine encoding the translocation domain of a bacterial toxin linked to a tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3698–3703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim JW, Hung CF, Juang J, et al. Comparison of HPV DNA vaccines employing intracellular targeting strategies. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1011–1018. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Castellino F, Germain RN. Cooperation between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells: when, where, and how. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:519–540. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu TC, Guarnieri FG, Staveley-O'Carroll KF, et al. Engineering an intracellular pathway for MHC class II presentation of HPV-16 E7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11671–11675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ji H, Wang TL, Chen CH, et al. Targeting HPV-16 E7 to the endosomal/lysosomal compartment enhances the antitumor immunity of DNA vaccines against murine HPV-16 E7-expressing tumors. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:2727–2740. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huang CH, Peng S, He L, et al. Cancer immunotherapy using a DNA vaccine encoding a single-chain trimer of MHC class I linked to an HPV-16 E6 immunodominant CTL epitope. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1180–1186. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim TW, Hung CF, Ling M, et al. Enhancing DNA vaccine potency by coadministration of DNA encoding antiapoptotic proteins. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:109–117. doi: 10.1172/JCI17293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim TW, Lee JH, He L, et al. Modification of professional antigen-presenting cells with small interfering RNA in vivo to enhance cancer vaccine potency. Cancer Res. 2005;65:309–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cresswell P. Assembly, transport, and function of MHC class II molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Trombetta ES, Mellman I. Cell biology of antigen processing in vitro and in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:975–1028. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hung CF, Tsai YC, He L, Wu TC. DNA vaccines encoding Ii-PADRE generates potent PADRE-specific CD4+ T-cell immune responses and enhances vaccine potency. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1211–1219. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kim D, Hoory T, Wu TC, Hung CF. Enhancing DNA vaccine potency by combining a strategy to prolong dendritic cell life and intracellular targeting strategies with a strategy to boost CD4+ T cell. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:1129–1139. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lin CT, Tsai YC, He L, et al. DNA vaccines encoding IL-2 linked to HPV-16 E7 antigen generate enhanced E7-specific CTL responses and antitumor activity. Immunol Lett. 2007;114:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ohlschlager P, Quetting M, Alvarez G, Durst M, Gissmann L, Kaufmann AM. Enhancement of immunogenicity of a therapeutic cervical cancer DNA-based vaccine by co-application of sequence-optimized genetic adjuvants. Int J Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1002/ijc.24333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Aderem A, Ulevitch RJ. Toll-like receptors in the induction of the innate immune response. Nature. 2000;406:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35021228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hengge UR, Benninghoff B, Ruzicka T, Goos M. Topical immunomodulators – progress towards treating inflammation, infection, and cancer. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hasan UA, Bates E, Takeshita F, et al. TLR9 expression and function is abolished by the cervical cancer-associated human papillomavirus type 16. J Immunol. 2007;178:3186–3197. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hartmann G, Weiner GJ, Krieg AM. CpG DNA: a potent signal for growth, activation, and maturation of human dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9305–9310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dzierzbicka K, Kolodziejczyk AM. Adjuvants – essential components of new generation vaccines. Postepy Biochem. 2006;52:204–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sheets EE, Urban RG, Crum CP, et al. Immunotherapy of human cervical high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia with microparticle-delivered human papillomavirus 16 E7 plasmid DNA. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:916–926. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Klencke B, Matijevic M, Urban RG, et al. Encapsulated plasmid DNA treatment for human papillomavirus 16-associated anal dysplasia: a Phase I study of ZYC101. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1028–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Garcia F, Petry KU, Muderspach L, et al. ZYC101a for treatment of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:317–326. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000110246.93627.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Munger K, Basile JR, Duensing S, et al. Biological activities and molecular targets of the human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Oncogene. 2001;20:7888–7898. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gao Q, Singh L, Kumar A, Srinivasan S, Wazer DE, Band V. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6-induced degradation of E6TP1 correlates with its ability to immortalize human mammary epithelial cells. J Virol. 2001;75:4459–4466. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4459-4466.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dalal S, Gao Q, Androphy EJ, Band V. Mutational analysis of human papillomavirus type 16 E6 demonstrates that p53 degradation is necessary for immortalization of mammary epithelial cells. J Virol. 1996;70:683–688. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.683-688.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]