Abstract

Research on the pathogenicity of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) during cervical carcinogenesis often relies on the study of homogenized tissue or cultured cells. This approach does not detect molecular heterogeneities within the infected tissue. It is desirable to understand molecular properties in specific histological contexts. We asked whether Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) of archival cervical tumors in combination with real-time polymerase chain reaction and bisulfite sequencing permits (i) sensitive DNA diagnosis of small clusters of formalin fixed cells, (ii) quantification of HPV DNA in neoplastic and normal cells, and (iii) analysis of HPV DNA methylation, a marker of tumor progression. We analyzed 26 tumors containing HPV-16 or 18. We prepared DNA from LCM dissected thin sections of 100 to 2000 cells, and analyzed aliquots corresponding to between nine and 70 cells. We detected nine to 630 HPV-16 genome copies and one to 111 HPV-18 genome copies per tumor cell, respectively. In 17 of the 26 samples, HPV DNA existed in histologically normal cells distant from the margins of the tumors, but at much lower concentrations than in the tumor, suggesting that HPVs can infect at low levels without pathogenic changes. Methylation of HPV DNA, a biomarker of integration of the virus into cellular DNA, could be measured only in few samples due to limited sensitivity, and indicated heterogeneous methylation patterns in small clusters of cancerous and normal cells. LCM is powerful to study molecular parameters of cervical HPV infections like copy number, latency and epigenetics.

Introduction

The molecular biology of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) has been extensively studied in vitro, in cell culture, and in clinical samples, and the data garnered from these studies have led to detailed information about the productive life cycle of HPVs and HPV induced pathogenesis. Certain HPV types such as HPV-16 and HPV-18 are sexually transmitted, and a fraction of the infections in women, mostly those of epithelial cells at the squamo-columnar junction of the cervix, can progress from subclinical infections to non-invasive cancer precursors (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) to carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinomas (zur Hausen, 2002; Munoz et al., 2003; Bernard, 2005). Unfortunately, many experimental strategies provide data that reflect the average property of large numbers of HPV genomes or HPV infected cells. This overlooks the possibility that the viral biology is heterogeneous in cell populations of differentiating squamous epithelia (Lee and Laimins, 2007). Similarly the progression of neoplasia generates histological heterogeneities due to sequential mutations and clonal expansions. As a consequence, we have little information about the spatial and temporal changes of HPV infections at the same anatomic site. This limits our ability to detect HPVs in subclinical and “latent” infections, and to discern patterns of regulatory switches, sequential mutations and epigenetic changes during carcinogenic progression. These problems can only be overcome with techniques that target selected small groups of cells or even individual cells.

Laser capture microdissection (LCM) uses a laser beam targeted at tissue sections under microscopic control to isolate clusters of cells that allow the molecular comparison of cell populations that are histologically or pathologically distinct although topographically contiguous. This technique has opened new and successful avenues for enquiries about molecular histology and pathology in many fields of cancer research (for reviews, see Fuller et al, 2003; Espina et al., 2005; Domazet et al., 2008), but has only been sporadically used in the analysis of neoplastic tissue from the cervix. In the experiments reported here, we used LCM to investigate whether HPV DNA can be sensitively and quantitatively detected in small clusters of archival (i.e. formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded) samples. We also asked whether the HPV DNA is restricted to pathologically distinct cells or is present in adjacent normal cells. This question is of interest in order to understand the issue of subclinical disease, and to clarify the ill-defined concept of “latency” in HPV biology and pathogenesis. Lastly, we added pilot experiments to address whether the same DNA preparations can be used to study the epigenetics of HPV genomes, a powerful characteristic of this DNA to identify cancerous progression, since HPV-16 and HPV-18 genomes are targeted by epigenetic changes during productive infections and neoplasia of anogenital and oral lesions (Kalantari et al., 2004; Turan et al., 2006; Balderas-Loaeza et al., 2007; Kalantari et al., 2008). In these publications we have reported that single lesion normally contain HPV genomes with diverse methylation patterns, and that the HPV-16 and 18 L1 genes can become specifically hypermethylated in tumors, apparently as a consequence of recombination between the viral and the cellular DNA.

Results

Overall strategy

This study targeted thin sections of squamous and adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix to address the questions of (i) whether HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA can be detected with high sensitivity in groups of cells ranging from 100 to 2000 cells and in DNA aliquots corresponding to only a small fraction of these cells, (ii) whether we can estimate the copy number of the viral genomes in the lesion by comparison with a cellular gene, (iii) whether the viral DNA is present only in cancerous tissue or also detectable in surrounding histologically normal epithelial cells andp in mesenchyme, and (iv) whether DNA methylation as an epigenetic characteristics of HPV DNA and indicative of tumor progression can – in principle – be studied with these very small samples.

Sensitive detection of HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA in LCM samples from archival cervical carcinomas in multiple copies per cell

The first column of Table 1 lists the blinded designation of 26 cervical carcinomas sorted by the two HPV types. In the second column, the values in brackets represent the CT values for HPV DNA and as internal control the CT value of the cellular single copy gene for hydroxymethylbilane synthase (HMBS). HPV-16 or HPV-18 DNA could be detected in all of these samples, although the PCR reaction was initiated with a DNA amount equivalent to the content of nine to 70 cells only. In addition, we could detect the HMBS gene in 25 of these 26 samples, and quantify it by CT values in 20 samples. The CT values of different PCR amplicons (and therefore target genes) cannot be rigorously compared, but they are useful to estimate relative copy numbers. With this restriction in mind, we have calculated the number of HPV-16 and 18 genomes per cell of each tumor sample based on the assumptions that each cell contains two HMBS genes and that a difference of one unit of the CT values corresponds to a factor of two. As table 1 shows, the number of HPV genome copies per cell varies widely from tumor to tumor, namely between nine and 630 copies for HPV-16 and between one and 111 copies for HPV-18. We validated the quantification of the HPV genomes per cell by including SiHa and HeLa cells in Table 1. SiHa contains 2 HPV-16 genomes per cell and HeLa 50 HPV-18 genomes. Targeting 600 and 60 cells of each cell line, we measured 15 and 23 HPV-16 copies in SiHa cells, a roughly ninefold overestimate, and 30 and 22 HPV-18 copies in HeLa, a twofold underestimate. We conclude that the realtime PCR technique permits a quantitative approach, which is however sensitive to the identity of the primers and the amplicons. The deviation between the precision of measuring HPV-16 and 18 is too large to interpret the quantitative differences we found between HPV-16 and 18 in tumors.

Table 1.

Quantitative real-time PCR detection of HPV-16 and HPV-18 in LCM generated samples from squamous carcinomas of the cervix and in samples from adjacent normal epithelial and mesenchymal tissue. The first column lists the clinical/laboratory code of each of 26 cervical carcinomas. The second, third and fourth column list three numbers, in each case first the copy number of the virus per cell, then the CT value of the HPV-16/18 RT-PCR signal, and thirdly the CT value of the cellular marker, the HMBS gene. The second column lists data obtained with tumor samples, the third normal cell clusters flanking the tumors, and the fourth flanking mesenchymal tissues. Each CT value represents the average of the RT-PCR values obtained from two DNA preparations made from two juxtaposed LCM samples cleaved from the same thin section of the tumor. The abbreviations “pos.” and “neg.” refer to a positive or negative PCR signal, evaluated by gel electrophoresis, in cases where no quantitative real-time-PCR amplification could be achieved. The letter X replaces the copy number in those cases where the virus, but not the cellular gene as the denominator of the calculation could be quantified

| Name of tumor | HPV genome copy number (CT HPV/CT HMBS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HPV-16 | tumor: | normal epithelium: | stroma: |

| T16–1 | 74 (14.8/20.0) | <1 (24.1/21.3) | <1 (27.9/26.6) |

| T16–2 | X (15.6/pos.) | 0 (neg./pos.) | 0 (neg./pos.) |

| T16–3 | X (14.5/pos.) | 0 (neg./pos.) | 0 (neg./pos.) |

| T16–4 | 630 (18.9/27.2) | 0 (neg./28.2) | 0 (neg./26.9) |

| T16–5 | 208 (14.5/21.8) | 2 (26.8/26.7) | <1 (27.0/24.0) |

| T16–6 | 104 (14.5/20.2) | <1 (29.3/22.6) | 0 (neg./22.3) |

| T16–7 | 9 (20.1/22.2) | <1 (25.1/21.5) | 0 (neg./24.0) |

| T16–8 | 49 (17.8/22.4) | <1 (32.0/22.3) | 0 (neg./25.3) |

| T16–9 | 16 (17.6/20.6) | <1 (24.2/21.7) | 0 (neg./22.3) |

| T16–10 | 97 (15.3/20.9) | <1 (28.0/23.4) | 0 (neg./25.0) |

| T16–11 | 128 (18.5/24.5) | <1 (29.8/26.3) | 0 (neg./27.1) |

| T16–12 | 181 (18.6/25.1) | 11 (24.6/27.1) | 0 (neg./27.7) |

| T16–13 | 315 (20.4/27.7) | 0 (neg./27.6) | 16 (24.6/27.6) |

| SiHa (600 cells) | 15 (24.9/28.8) | ||

| SiHa (60 cells) | 24 (28.3/32.9) | ||

| HPV-18 | |||

| T18–1 | 30 (18.3/22.2) | <1 (29.2/25.8) | 0 (neg./25.1) |

| T18–2 | 3 (22.0/22.5) | 0 (neg./23.0) | 0 (neg./25.1) |

| T18–3 | <1 (24.1/22.5) | <1 (26.5/25.0) | 0 (neg./23.7) |

| T18–4 | X (19.9/pos.) | X (30.3/pos.) | 0 (neg./pos.) |

| T18–5 | X (19.8/pos.) | 0 (neg./neg.) | 0 (neg./pos.) |

| T18–6 | X (15.6/n.d.) | X (26.3/neg.) | 0 (neg./neg.) |

| T18–7 | X (20.9/pos.) | X (29.2/neg.) | 0 (neg./neg.) |

| T18–8 | 2 (24.3/24.4) | 0 (neg./24.6) | 0 (neg./26.2) |

| T18–9 | 111 (19.0/24.8) | 0 (neg./27.7) | 0 (neg./27.4) |

| T18–10 | 6 (23.6/25.2) | 0 (neg./24.2) | 0 (neg./27.6) |

| T18–11 | 2 (21.5/21.5) | <1 (24.8/21.1) | <1 (26.5/23.3) |

| T18–12 | 1 (21.8/20.5) | <1 (28.5/22.5) | 0 (neg./26.4) |

| HeLa (600 cells) | 30 (25.8/30.6) | ||

| HeLa (60 cells) | 22 (29.1/34.3) | ||

| HPV-16/18: | |||

| T16/18–1 | 97 (18.3-HPV-18/23.9) | <1 (26.8-HPV-16/22.3) | 0 (neg./24.5) |

We conclude that a specific cellular gene as well as HPV DNA can be readily detected and with some reliability quantified in small LCM generated clusters of formalin-fixed samples. HPV genomes are normally present at higher copy numbers than cellular genes and their quantities vary widely from lesion to lesion, and the CT values allow estimating the ratio between HPV genomes and cellular genes.

HPV-16 and HPV-18 in histologically normal squamous epithelial cells of the cervix sampled remote from detectable neoplasia

In order to address the question whether HPV-16 and HPV-18 DNA exists outside of the tumor margins, we generated DNA preparations from clusters of mesenchymal and squamous epithelial cells outside the cancerous tissue. The measures that we took to avoid cross-contamination between the samples have been described above.

In all samples, the heterologous control (kidney) led to HMBS signals but not to HPV detection (data not shown) excluding contaminations of the analyzed tissue associated with the manipulation processes.

The third column of Table 1 shows the analysis of normal tissue outside the histological margins of the tumor. Twenty-two of these 26 samples contained sufficient DNA for diagnoses as judged by HMBS signals. To our surprise, 16 of these 22 HMBS positive samples also gave rise to a CT value for HPV-16 or HPV-18. Our precautions and the much lower detection frequency in stroma samples (see below) make it very unlikely that these signals originate from cross-contamination. A contamination by mucus from the tumor is further unlikely, as tumors do not produce HPV particles, and are unlikely to release pure HPV DNA, and since many of our cuts of normal tissue avoided the epithelial surface area, where mucus could spread. We interpret these signals as evidence for the presence of HPV DNA in histologically normal cell populations. Notably, however, most samples contained less than one copy of HPV DNA per cell, indicative of single or small groups of infected cells among the hundreds analyzed. We interpret these data as evidence for low copy number replication of HPV DNA in a subset of histologically normal cells and point to the possibility that an expanded and refined study using this technology could shed light on the phenomenon of “latent” infection by HPVs.

The fourth column of Table 1 shows the analysis of stroma (mesenchyme) samples. Nineteen of the 26 samples gave a CT value for the HMBS, and another four, where PCR was done without quantification, a positive PCR signal. In other words, 23 samples were satisfactory for DNA diagnoses. Only four of these 23 samples gave a RT-PCR signal for HPV, and only one of them indicated a higher copy number than the HMBS control. This confirms the assumption that HPVs normally do not infect the stroma. It is not clear if the signals of four HPV positive samples represent histologically inconspicuous invasion of the mesenchyme by HPV containing tumor cells, or some other undefined process.

The last line of table 1 reports a peculiarity: Tumor T16/18-1 contained HPV-18, while flanking normal tissue generated a signal for HPV-16, showing the double infection with different HPV types can occur only a few cell diameters apart from one another.

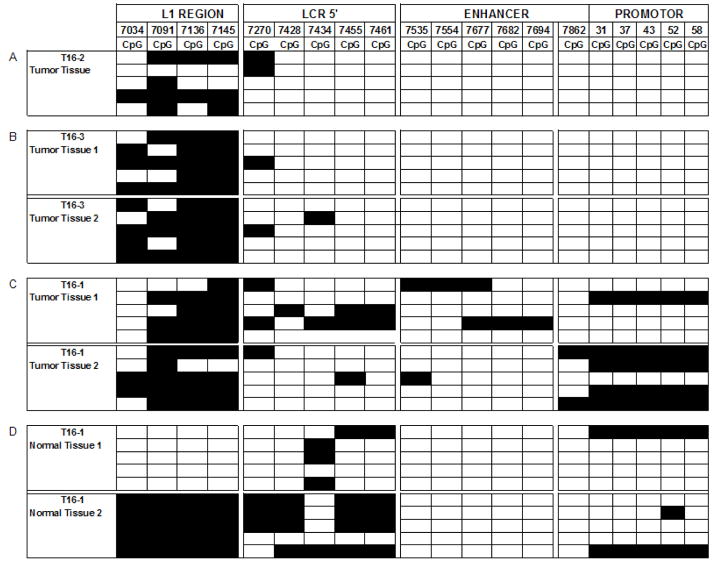

DNA methylation of HPV-16 can be measured in LCM generated samples

These pilot experiments relating to methylation were performed to explore whether the limited DNA preparations from LCM samples would permit methylation analyses, considering that the bisulfite technique is much less sensitive than the RT-PCR experiments reported above. Fig. 2 shows the outcome of studying three of the previously analyzed tumors, while the analysis of all others preparations was not possible due to limited sample size. This figure reports the methylation status of 19 CpG residues stretching from the 3′ flank of the HPV-16 L1 gene through the viral long control region to the promoter for the E6 gene. Details of this documentation have been reported in our previous publications on biopsies and cell lines of cervical, oral, and penile HPV-16 associated carcinomas (Kalantari et al., 2004; Balderas-Loaeza et al., 2007; Kalantari et al., 2008a and b).

Fig. 2. Distribution of methylated CpG residues at the 3′ flank of L1 and through the LCR of HPV-16.

Each vertical set of rectangles represents one of 19 specific CpG dinucleotides, the number on the top of the bar the position of this CpG in the genome of HPV-16. Each horizontal set of rectangles represents a 913 bp segment of the HPV-16 genome, covering the 3′ end of the L1 gene and the complete long control region. Unmethylated CpGs are indicated by white rectangles, methylated by black ones. The two vertical white separators indicate the borders between amplicons, and discontinuities between supposedly different HPV-16 molecules. Further experimental details of this approach and interpretation of the preferential methylation of the L1 gene has been addressed in detailed by multiple studies from our group that targeted cervical, oral, and penile HPV-16 infections (Kalantari et al., 2004; Balderas-Loaeza et al., 2007; Kalantari et al., 2008).

Fig. 2A shows the methylation pattern of HPV-16 in tumor T16–2. Twenty amplicons represent the methylation state of four contiguous but separately amplified short genomic regions of HPV-16, corresponding to the L1 gene, the 5′ part of the LCR, the central LCR, and the promoter region, of five independent clones from each region. As normally observed in tumors, methylation concentrates on the L1 region and is absent from most of the LCR. Fig. 2B represents 40 amplicons from the same genomic region of HPV-16 from tumor T16–3, and Fig. 2C 40 amplicons from tumor T16–1. Fig. 2D shows 40 amplicons derived from two separate LCM cuts of normal epithelium flanking tumor T16–1. All samples, representing a total of seven LCM dissection products, show that the diversity of methylation patterns, as observed previously in DNA preparations from whole lesions, is frequent on the microscopic level. There are some identical patterns among some clones of the same tumor, potential examples of clonal outgrowth of a cell with a particular epigenetic pattern. L1 gene hypermethylation, an indicator of integration of HPV into the chromosomal DNA, is apparent in all twenty L1 amplicons from the tumor tissue. It is also present in one of the two samples from normal tissue, while the other sample is unmethylated, indicating epigenetic changes in normal tissue, possibly due to HPV-cell DNA recombination, that has not yet become reflected in histological changes. Both cuts from the normal tissue could be considered as histological latent infection. But while unmethylated HPV genomes are likely episomal and indicate an infection that may resolve itself, the sample with methylated HPV genomes likely contains only integrated viral genomes, a state that is molecularly, although not yet histologically, committed to progress.

Discussion

This study confirmed that one can detect HPV genomes as well as a cellular control gene in LCM generated samples from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded samples with high sensitivity and in semi-quantitative manner. We interpreted the CT values generated RT-PCR experiments. Assuming that each cell contained two alleles of the HMBS gene, and that a difference in a CT value of one unit identifies one PCR depending duplication, we detected nine to 630 HPV-16 genome copies and one to 111 HPV-18 genome copies per tumor cell, respectively. Validation of the CT values against cell lines indicates that may have to be revised, and that the actual HPV-16 genomes copy numbers are by a factor of nine lower and the HPV-18 copies by a factor of two higher than measured. While we attempted to dissect cancer samples only down to clusters of minimally 100 cells, and while we did not use DNA dilutions corresponding to the content of less than nine cells, the measured sensitivities nevertheless suggest that one can amplify, quantify and characterize the HPV DNA load of single cells.

Our research also aimed to help to understand the phenomena of subclinical HPV infections and latency. The term “subclinical HPV infection” defines a situation where the DNA tests of smears or biopsies detect HPV DNA, while cytology and histology cannot detect abnormal cells nor can lesions be diagnosed by colposcopy. The term “latency” does not necessarily refer to the same scenario. While poorly defined in HPV biology, it has a defined meaning in unrelated viruses. For example, in herpes viruses it refers to defined stages of the viral life cycle and molecular biology in the absence of symptoms, and often in other cell types than those that are involved in disease. While we cannot resolve these matters for HPVs, our observations suggest that histologically normal squamous epithelia, contiguous with but remote from cancerous lesions, harbor HPV genomes. In contrast to tumors, there are often on the average less than one HPV genome per cell, although we observed HPV DNA in some normal tissues at nearly equal concentration as cellular genes, or, in the case of two tumors, significantly exceeding it. We worked with these specific normal cell preparations from tumor patients, as we could not sample cervical tissue biopsies from healthy patients for ethical reasons. Consequently, we do not know whether our observations would only apply to normal epithelia that are topographically linked to cancerous tissue, or whether our data describe a subclinical infection in the absence of any neoplasia. In spite of this limitation, we conclude that histologically normal squamous epithelia of the cervix can contain HPV genomes. One can speculate whether this means that these tissues represent productive infections or merely temporary replication of fortuitously infected tissue. Future research using our approach can possibly resolve whether there is a molecular difference between productive infections in neoplastic precursor lesions and “latent” infection in normal epithelia. The relevance of this question has been addressed previously by Abramson and colleagues (Abramson et al., 2004), who observed the presence of HPV-6 and 11 outside the margins of laryngeal warts, frequently often in the tracheal epithelium outside the squamous epithelium of the larynx. These authors proposed that such infections outside of histologically defined lesions may be the source for postsurgical recurrence of respiratory papillomatosis (Abramson et al., 2004).

We have previously published on the epigenetic modification of HPV-16 and HPV-18 genomes during carcinogenesis (Kalantari et al., 2004; Turan et al., 2006 and 2007; Balderas-Loeza et al., 2007; Kalantari et al., 2008a and b). An important aspect of our data was the observation that HPV genomes, and specifically the L1 genes, tend to become hypermethylated as a consequence of recombination with cellular DNA. As this occurs frequently during carcinogenesis, but not during the normal life cycle of HPVs, L1 gene methylation can be interpreted as a biomarker of cells that have taken an irreversible step toward the cancerous state. Since methylation studies depend on bisulfite treatment of DNA, which unavoidably involves some covalent degradation, we have learned in the research reported here that LCM generated samples are often too small for such epigenetic studies. We have reported that three cancers, whose DNA preparations were amenable to methylation studies, showed the expected L1 methylation. As in the analysis of whole tumors, we observed heterogeneous methylation patterns, indicating epigenetic diversity even in small clusters of cells. Surprisingly, two LCM preparations from the normal tissue close to the same tumor showed L1 methylation and lack of methylation, respectively. We can only speculate that the methylated HPV genomes may exist recombined with chromosomal DNA, and the unmethylated as episomes, suggesting that the former cell population might have progressed already molecularly in spite of normal histology. It would also be desirable to compare methylation data with direct measurements of HPV integration into chromosomes, as published recently (Kalantari et al., 2008b). Unfortunately, our LCM research was targeted at formalin fixed samples, which do not permit the restriction-ligation approach used in our previous publication, due to the need of amplicons larger than a few hundred basepairs, which can only be obtained from fresh samples.

In published LCM based studies of papillomavirus lesions the LCM technique helped to confirm the presence of HPV in endocervical adenocarcinoma cells (Chew et al., 2005a and b). It allowed detecting differential expression of cellular genes that correlated with the tissue substructures of HPV and of cottontail rabbit papillomavirus lesions (Baumgarth et al., 2004; Kendrick et al., 2007; Huber et al., 2004). LCM has also been used for DNA diagnosis of head-and-neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) (Anderson et al., 2008), and to elucidate molecular differences between HPV containing and HPV independent HNSCCs (Pyeon et al., 2007). These publications and our data confirm the power of LCM technology to investigate biological and pathogenic properties of papillomavirus infections that vary among the diverse cell populations affected by the virus. Future research may expand our limited knowledge of the molecular switches during the normal HPV life cycle and of mutational and epigenetic changes during multistep carcinogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Tissue samples

The tissue samples consisted of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues of squamous and glandular cell carcinomas of the cervix from 26 patients who were biopsied at the Service of Gynecology at the Instituto Nacional de Cancerologie in Mexico City, or underwent surgery at the Medical Center of the University of California Irvine, at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, or at the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. Thirteen of these samples contained HPV-16, twelve HPV-18, and one sample both viruses, based on detection of diagnostic amplicons after polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with type specific oligonucleotide primers. HPV genotypes were confirmed by PCR analysis of DNA preparations from thin sections that were not LCM treated following standard DNA extraction procedures and amplification with published primers (Kalantari et al., 2004; Turan et al., 2006).

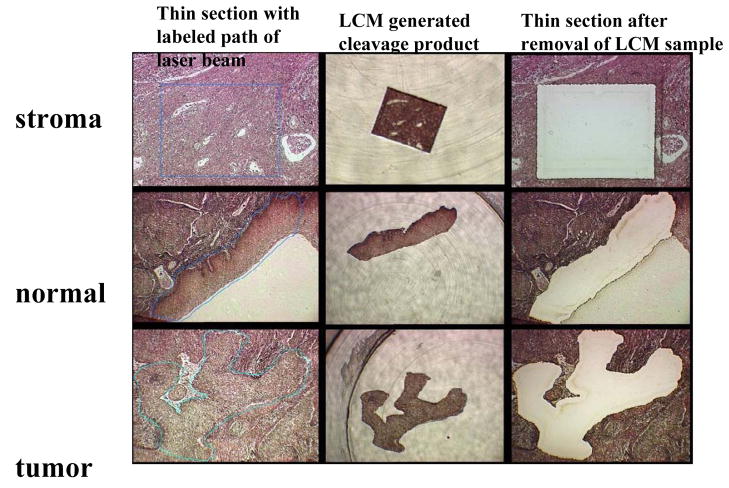

Laser Capture Microdissection

From each sample, five-micrometer sections were applied to membrane-coated slides with diluted tissue adhesive (TA, Diagnostic Products Corporation, van Golsteinlaan 26, 7339 GT Apeldoorn, the Netherlands) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). The margins of cancerous cell populations were microscopically defined and labeled by one of the pathologists in our team (R.Z., D.P.M). A Leica AS LMC Laser Microbeam Microdissection microscope with a 0.5 μm laser beam was used to dissect groups of variable numbers of cells, normally approximately 1000, but varying for some samples from 100 to 2000 cells. These dissected cell clusters were captured in test tubes after release from the inverted slide. Fig. 1 exemplifies the LCM generated separation of stromal, normal squamous epithelial and cancerous tissue from the same tumor biopsy.

Fig. 1. Laser Capture Microdissection of one cluster each of stromal, normal squamous and cancerous cells from a thin section of a biopsy of a cervical squamous carcinoma.

The first column of three microscopic pictures shows the fixed tissue after thin section, a blue line indicating the programmed path of the laser beam. The second column shows the cleaved sample after transfer to a test tube. The third column the remaining tissue after removal of the experimental sample. The three cuts were targeted at the same thin section of a tumor.

The possibility that contaminations may occur in the microtome was eliminated by using disposable blades. In order to minimize and monitor DNA contaminations by vapor potentially set free during the LCM process, we first cut mesenchymal tissue (supposed to have no HPV DNA), followed by histologically normal epithelial tissue (possibly not having HPV DNA), and only as the last step the carcinoma tissue, whose analysis gave rise to the tumor CT values in the first column of Table 1 as discussed above. In order to avoid contamination of the mesenchymal or normal epithelial cell preparations by imprecise dissection, we kept a space of at least five to ten cell diameter, i.e. about 50 μm, between the histologically defined margin of the tumor and the non-cancerous tissues.

DNA preparation

LCM generated samples were mixed with 140 μl digestion buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Tween-20) and 100 μg Proteinase K and incubated overnight at 37°C followed by 10 min incubation at 90°C. Five out of 140 μl of each DNA preparation was taken directly for all PCR analyses without further purification. This volume corresponded to the DNA of about nine to 70 cells depending on the size of the LCM cleaved cell cluster. DNA methylation analyses were attempted by bisulfite treatment of the DNA preparations followed by PCR, cloning of the amplification product into E. coli vectors, and DNA sequencing.

Detection and quantification of HPV-16 and 18 DNA

We used a real-time PCR approach to detect and quantify HPV-16 and 18 DNA. The principles of the probe technology, frequently referred to as TaqMan probes, have been published (Morris et al., 1996; Clement et al., 2005). For detection of HPV-16, we used oligos targeting the L1 gene of the virus as published by Moberg et al., 2003, namely F16E7 (5′-AGCTCAGAGGAGGAGGATGAA-3′) and R16E7 (5′-GGTTACAATATTGTAATGGGCTC-3′) for amplification and as TaqMan probe Pb1.1 (FAM-CCAGCTGGACAAGCAGAACCGG-TAMRA) linked to the 5′ fluorescent reporter dye (6FAM) and a 3′ quencher (TAMRA). For detection of HPV-18, we used F18E1 (5′-CATTTTGTGAACAGGCAGAGC-3′) and R18E1 (5′-ACTTGTGCATCATTGTGGACC-3′) for amplification and as a TaqMan probe Pb1.2 (VIC-AGAGACAGCACAGGCATTGTTCCATG-TAMRA). The human single copy gene for hydroxymethylbilane synthase (HMBS, GenBank accession no. M95623.1) served as positive amplification control with the primers and probes described by Moberg et al., 2003: HMBS-F (5′-GCCTGCAGTTTGAAATCAGTG-3′), HMBS-R (5′-CGGGACGGGCTTTAGCTA-3′) and the TaqMan probe VIC-TGGAAGCTAATGGGAAGCCCAGTACC-TAMRA.

Each analysis began with a preamplification, followed by quantitative RT-PCR amplification, using the same primers for both reactions. In the initial reaction, 4 μl of crude lysate was pre-amplified using 6.25 μl TaqMan preamp Master Mix kit (ABI), 1.6 μl of a mix of primers for HPV-16, HPV-18 and HMBS, and 1.15 μl water (total volume 13 μl) after an initial extension for 10 min at 95°C in 14 cycles (15 sec, 95°C, 4 min, 60°C). The reaction product was diluted 1:10, and 4 μl were amplified and quantified with an ABIprism 7900HT instrument, in reaction volume of 25 μl containing 1x Taqman Universal PCR Mastermix (Applied Biosystems), 0.6 μM of each primer and 0.2 μM of Taqman probe. The thermal cycler conditions were 10 min denaturation at 94 °C, and 45 cycles of 15 sec at 94 °C and 1 min at 58 °C. The results were analyzed using ABIPrism’s SDS v2.1 software.

Bisulfite sequencing

All procedures for determining the methylation status of the HPV-16 and 18 L1 genes and long control regions (LCRs) after bisulfite modification (Frommer et al., 1992), the design of primers for amplification of bisulfite treated DNA, and the sequencing of the amplification products after cloning into E. coli vectors have been described in detail (Kalantari et al., 2004; Turan et al., 2006; Kalantari et al., 2008).

Acknowledgments

Our research was supported by NIH grant R01 CA-91964 to H.U.B., by a grant from the Flight Attendants Medical Research Institute (FAMRI) to H.U.B, by funds from the Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center of the University of California Irvine to H.U.B., and by three grants from UC Mexus to I.E.C.M., A.G.C. and H.U.B., by Grants from the Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, and the Medical Research Council, as well as the Cancer Society in Stockholm, the Stockholm County Council, and the Swedish Labour Market Insurance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramson AL, Nouri M, Mullooly V, Fisch G, Steinberg BM. Latent Human Papillomavirus infection is comparable in the larynx and trachea. J Med Virol. 2004;72:473–477. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CE, McLaren KM, Rae F, Sanderson RJ, Cuschieri KS. Human papillomavirus in squamous carcinoma of the head and neck: a study of cases in southeast Scotland. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:439–441. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.033258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderas-Loaeza A, Anaya-Saavedra G, Ramirez-Amador VA, Guido-Jimenez MC, Kalantari M, Calleja-Macias IE, Bernard HU, Garcia-Carranca A. Human papillomavirus-16 DNA methylation patterns support a causal association of the virus with oral squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2165–2169. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarth N, Szubin R, Dolganov GM, Watnik MR, Greenspan D, Da Costa M, Palefsky JM, Jordan R, Roederer M, Greenspan JS. Highly tissue substructure-specific effects of human papilloma virus in mucosa of HIV-infected patients revealed by laser-dissection microscopy-assisted gene expression profiling. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:707–718. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63334-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HU. The clinical importance of the nomenclature, evolution, and taxonomy of papillomaviruses. J Clin Virol. 2005;32(suppl):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew GK, Cruickshank ME, Rooney PH, Miller ID, Parkin DE, Murray GI. Human papillomavirus 16 infection in adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1301–1304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew K, Rooney PH, Cruickshank ME, Murray GI. Laser capture microdissection and PCR for analysis of human papilloma virus infection. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;293:295–300. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-853-6:295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement G, Benhattar J. A methylation specific dot blot assay (MS-DBA) for the quantitative analysis of DNA methylation in clinical samples. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:155–158. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.021147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domazet B, Maclennan GT, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Cheng L. Laser capture microdissection in the genomic and proteomic era: targeting the genetic basis of cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;15:475–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espina V, Geho D, Mehta AI, Petricoin EF, Liotta LA, Rosenblatt KP. Pathology of the future: molecular profiling for targeted therapy. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:36–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer M, McDonald LE, Millar DS, Collis CM, Watt F, Grigg GW, Molloey PL, Paul CL. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller AP, Palmer-Toy D, Erlander MG, Sgroi DC. Laser capture microdissection and advanced molecular analysis of human breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2003;8:335–345. doi: 10.1023/b:jomg.0000010033.49464.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber E, Vlasny D, Jeckel S, Stubenrauch F, Iftner T. Gene profiling of cottontail rabbit papillomavirus-induced carcinomas identifies upregulated genes directly involved in stroma invasion as shown by small interfering RNA-mediated gene silencing. J Virol. 2004;78:7478–7489. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7478-7489.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari M, Calleja-Macias IE, Tewari D, Hagmar B, Barrera-Saldana HA, Wiley DJ, Bernard HU. Conserved methylation patterns of human papillomavirus-16 DNA in asymptomatic infection and cervical neoplasia. J Virol. 2004;78:12762–12772. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12762-12772.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari M, Lee D, Calleja-Macias IE, Lambert PF, Bernard HU. Effects of cellular differentiation, chromosomal integration and treatment by 5′-deoxy-2′azacytidine on human papillomavirus-16 DNA methylation in cultured cell lines. Virology. 2008a;374:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari M, Villa LL, Calleja-Macias IE, Bernard HU. Human papillomavirus-16 and 18 in penile carcinomas: DNA methylation, chromosomal recombination, and genomic variation. Intern J Cancer. 2008b;123:1832–1840. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick JE, Conner MG, Huh WK. Gene expression profiling of women with varying degrees of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:25–28. doi: 10.1097/01.lgt.0000230124.68996.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Laimins LA. The differentiation-dependent life cycle of human papillomaviruses in keratinocytes. In: Garcea RL, DiMaio D, editors. The Papillomaviruses. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Moberg M, Gustavsson I, Gyllensten U. Real-Time PCR-Based System for Simultaneous Quantification of Human Papillomavirus Types Associated with High Risk of Cervical Cancer. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3221–3228. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3221-3228.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris T, Robertson B, Gallagher M. Rapid reverse transcription-PCR detection of hepatitis C virus RNA in serum by using the TaqMan fluorogenic detection system. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2933–2936. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2933-2936.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, Snijders PJF, Meijer CJLM. Epidemiological classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:518–527. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyeon D, Newton MA, Lambert PF, den Boon JA, Sengupta S, Marsit CJ, Woodworth CD, Connor JP, Haugen TH, Smith EM, Kelsey KT, Turek LP, Ahlquist P. Fundamental differences in cell cycle deregulation in human papillomavirus-positive and human papillomavirus-negative head/neck and cervical cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4605–4619. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan T, Kalantari M, Calleja-Macias IE, Villa LL, Cubie HA, Cuschieri K, Skomedal H, Barrera-Saldana HA, Bernard HU. Methylation of the human papillomavirus-18 L1 gene: A biomarker of neoplastic progression? Virology. 2006;349:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:342–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]