Abstract

Autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), result from deficiencies in self-antigen tolerance processes, which require regulated dendritic cell (DC) function. In this study we evaluated the phenotype of DCs during the onset of SLE in a mouse model, in which deletion of the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIb leads to the production of anti-nuclear antibodies and glomerulonephritis. Splenic DCs from FcγRIIb-deficient mice suffering from SLE showed increased expression of co-stimulatory molecules. Furthermore, diseased mice showed an altered function of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) transcription factor, which is involved in DC maturation. Compared with healthy animals, expression of the inhibitory molecule IκB-α was significantly decreased in mice suffering from SLE. Consistently, pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB activity in FcγRIIb-deficient mice led to reduced susceptibility to SLE and prevented symptoms, such as anti-nuclear antibodies and kidney damage. Our data suggest that the occurrence of SLE is significantly influenced by alterations of NF-κB function, which can be considered as a new therapeutic target for this disease.

Keywords: andrographolide, autoimmunity, dendritic cells, nuclear factor-κB, rosiglitazone, systemic lupus erythematosus

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic multisystem autoimmune disease that can manifest with a diverse array of clinical symptoms and which is characterized by the production of autoantibodies directed against nuclear antigens.1 Systemic injury may arise as a consequence of inflammation caused by direct autoantibody-mediated tissue injury and the deposition of complement-fixing immune complexes (ICs).2,3 IC-mediated inflammation has been shown to damage multiple organs, such as skin, joints, kidneys, brain and blood vessels.3,4 Although cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying this autoimmune disease are not completely understood, it has been proposed that deficiencies in peripheral tolerance to self-antigens could play a key role in the pathogenesis of SLE. Autoantigens, including nucleosomes, ribonucleoproteins and phospholipids, are targeted by T-cell-dependent humoral immunity.5 Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells, capable of promoting either immunity or tolerance to specific antigens.6–8 DCs play an important role in maintaining peripheral tolerance by preventing the activation of self-reactive T cells. Thus, alterations in the DC physiology are likely to contribute to a deficient process of tolerance to self-antigens.9,10 Maturation of DCs is a critical step in the induction of effector T-cell responses and relies on the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) transcription factors.11–13 NF-κB is a family of transcription factors that contribute to the transcriptional regulation of several genes required for the immune response.11–14 In DCs, NF-κB can be activated by several stimuli, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling.12 These stimuli lead to phosphorylation of the NF-κB inhibitor IκB-α, which is subsequently targeted for proteasomal degradation.15 As a result, NF-κB is translocated to the nucleus and promotes the transcription of several genes, including IκB-α and E-selectin, among others.15,16 As the majority of DC maturation stimuli mediate their activity by inducing transcription of genes controlled by NF-κB, this transcription factor is a key element in determining the phenotype of DCs. Therefore, inhibition of NF-κB activation has been proposed as a strategy to maintain DCs in an immature state to promote immune tolerance.14,17–19

In the present study, using mice that suffer from a spontaneous form of SLE as a result of the genetic deletion of FcγRIIb,20 we evaluated NF-κB expression and tested the potential of NF-κB inhibitors as a treatment for this disease. Our data suggest that FcγRIIb-deficient mice display altered NF-κB expression compared withwild-type animals. Accordingly, upon treatment with NF-κB inhibitors, mice exhibited a reduction in the incidence and severity of SLE. We observed milder glomerulonephritis and lower titers of anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs) in drug-treated animals compared with controls. Importantly, drug treatment increased NF-κB transcription to levels observed in control animals. Our results support the notion that NF-κB activity in DCs may play a critical role in the induction of autoimmune diseases, such as SLE. Moreover, treatment with NF-κB inhibitors may be relevant for the reduction of SLE severity.

Materials and methods

Animals

FcγRIIb-deficient mice in the C57BL/6 background were generously provided by Drs Jeffrey Ravetch (The Rockefeller University, NY) and Kenneth Smith (University of Cambridge, UK). Animals were kept under specific conditions at the pathogen-free animal facility of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Animals obtained food and water ad libitum. All animal work was performed according to institutional guidelines and was supervised by a veterinarian.

Reagents

The NF-κB inhibitors andrographolide and rosiglitazone were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO) and Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), respectively. A stock solution was prepared by dissolving these drugs in dimethylsulphoxide at 50 mm, which was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) immediately prior to each experiment, as described previously.17,19

Treatment with NF-κB inhibitors

Female FcγRIIb-deficient mice, 6–8 weeks of age, were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 4 mg/kg of andrographolide or rosiglitazone in PBS (total volume 100 μl), twice a week for 7 months. The dose used was significantly lower than the lethal dose 50% (LD50) described for i.p. administered andrographolide (11·6 g/kg).21 As controls, age-matched FcγRIIb-deficient mice received intraperitoneal injections of PBS. Five to nine treated and control mice were included in each independent experiment. Treated and control mice were clinically evaluated on a weekly basis. At the doses used, andrographolide and rosiglitazone were well tolerated by mice and no evidence of toxicity was observed.

SLE assessment

Starting at 2 months of age, blood and urine samples were collected from control and treated mice for assessment of ANAs, extractable nuclear antigens (ENAs) and proteinuria. ANA determination was performed over HEp-2 cells in 12-well slides (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to previous reports.20 Briefly, cells were incubated for 30 min with dilutions of serum derived from control and treated mice, followed by staining for 10 min with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (clone R12-3; PharMingen BD, San Diego, CA). ENAs were analyzed in mice sera using Bindazyme™ Human anti-Smith antigen (Sm)/ribonucleic protein (RNP), Ro ribonucleoprotein particle (Ro)/RNP, lupus anticoagulant antigen (La)/RNP and RNP enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits (The Binding Site, Birmingham, UK), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Proteinuria was estimated by examining fresh urine with Combur Test sticks for urinalysis (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) using a scale of 0–3, where 0/trace = negative, 1 = 30 mg/dl, 2 = 100 mg/dl, and 3 = 500 mg/dl. Proteinuria scores above 2 were considered to represent severe glomerulonephritis. After 7 months of treatment, histological examination of the kidneys was performed. To assess IC deposition, kidneys were embedded in Tissue-tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and snap frozen. Ten-micrometer sections were fixed with cold acetone and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (clone R12-3; PharMingen BD).20

DC maturation and mixed lymphocyte reaction assays

To evaluate DC maturation, cell suspensions obtained from the spleens of wild-type or FcγRIIb-deficient mice (control and treated) were analyzed for the expression of surface markers CD86-FITC (clone GL1; PharMingen BD), CD40-FITC (clone 3/23; PharMingen BD) and CD11c-PE (clone HL3; PharMingen BD) fixed on 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using winmdi software (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). For the mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLRs) splenic DCs from C57BL/6 and FcγRIIB−/− mice were purified with anti-CD11c-coated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech Inc., Auburn, CA). DCs were titrated and co-cultured during 36 hr with a fixed number of T cells (1 × 105) obtained from BALB/c mice. As a positive control, T cells were stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) (0.5 μg/ml), and T-cell activation was determined by measuring CD69 expression and interleukin (IL)-2 secretion, as previously described.22–24 For IL-12 secretion, purified DCs from FcγRIIB−/− and wild-type mice were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 μg/ml) for 36 hr and the supernatants were transferred to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates coated with purified anti-IL-12 (clone 9A5; PharMingen BD) and revealed with biotin-labeled anti-IL-12 (clone C17.8; PharMingen BD). For proliferation assays, T cells were stained with 10 μm carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE) for 10 min, washed and co-cultured with DCs purified from the spleens of FcγRIIB−/− or wild-type mice. Dilution of CFSE-derived fluorescence as a result of proliferation was quantified by flow cytometry.

DC purification from spleens

Spleens were obtained from wild-type and FcγRIIb-deficient mice and treated for 3 hr with 400 U/ml of collagenase type IV (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Single-cell suspensions were incubated with anti-CD11c–biotin (clone HL-3; Pharmingen BD). Cells were then washed and incubated with magnetic beads (Dynabeads M280-Streptavidin; Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway) and CD11c-positive cells were isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the MLRs, DCs were purified from spleens using anti-CD11c-coated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech Inc.), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was obtained from spleens using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was synthesized using ImProm-II Reverse Transcrption System with Random Primers (Promega, Madison, WI). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) quantification was conducted in a total volume of 20 μl containing 2 μl of cDNA, 10 μl of Brilliant SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix and 10 μm of each oligonucleotide primer. Primers used were as follows: IκB-α_sense 5′-AAC CTG CAG CAG ACT CCA CT-3′; IκB-α_antisense 5′-AGA CAC GTG TGG CCA TTG TA-3′; p65_sense 5′-GGG CCT TGCT TGG CAA CAG CACA-3; p65_antisense 5′-CGC AAT GGA GGA GAA GTC TTC ATC TCC-3′; β-actin_sense 5′-AGA GGG AAA TCG TGC GTG AC-3′; and β-actin_antisense 5′-GAC TCA TCG TAC TCC TGC TTG-3′. Amplification steps consisted of 40 cycles of denaturation at 94° for 30 seconds, annealing at 60° (β-actin and p65) or 58° (IκB-α) for 1 min, and extension at 72° for 30 seconds, using an MX3000P thermocycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). PCR products (expected size 481 bp for β-actin, 260 bp for p65 and 236 bp for IκB-α) were analyzed using mx3000p qpcr software (Stratagene). The relative expression of IκB-α was normalized to β-actin levels for each sample.

Results

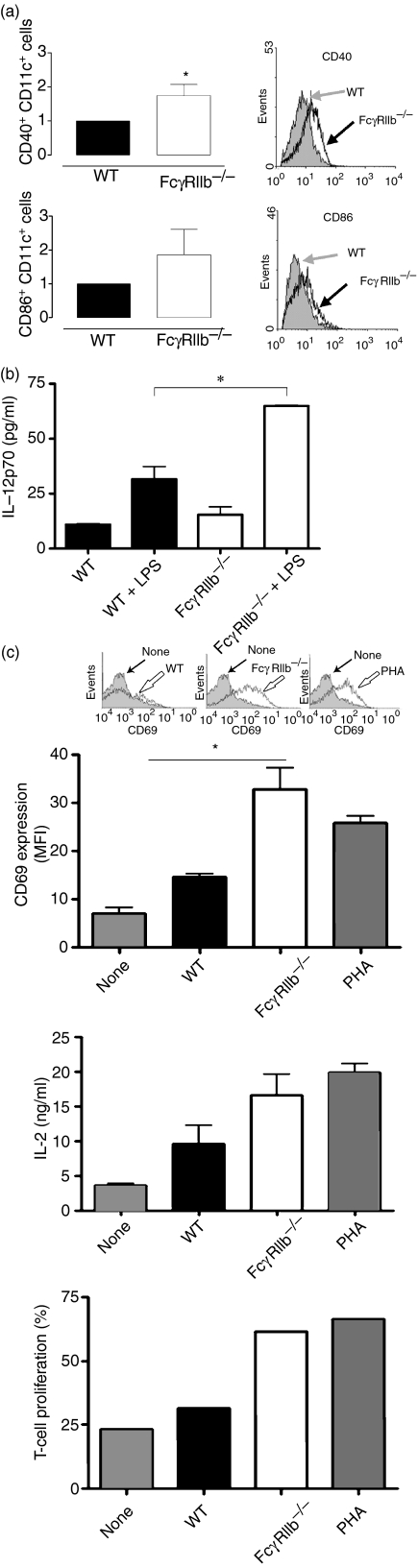

DCs obtained from FcγRIIb-deficient mice with SLE display a mature phenotype

Previous reports have suggested that the alterations in DC phenotype which are observed in autoimmune diseases can promote constant T-lymphocyte activation and consequently defects in tolerance maintenance.25 To investigate the role of DCs in SLE development in FcγRIIb-deficient mice, we first examined whether there was a difference in the maturation state of DCs between wild-type mice and SLE-prone mice. Spleen and lymph node cell suspensions from 8-month-old FcγRIIb-deficient and wild-type mice were analyzed for the expression of maturation markers in CD11c+ cells. Increased expression of co-stimulatory molecules CD40 and CD86 could be observed on the surface of FcγRIIb−/− DCs when compared with DCs obtained from age-matched wild-type mice (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, in response to stimulation with LPS, DCs purified from the spleens of FcγRIIb−/− mice secreted significantly more IL-12 than did DCs obtained from wild-type mice (Fig. 1b). In addition, DCs obtained from FcγRIIb−/− mice showed a significant enhancement in their capacity to prime alloreactive T cells compared with DCs obtained from wild-type mice. In MLR assays, T cells stimulated with allogeneic FcγRIIb−/− DCs showed a significant increase in expression of the activation marker CD69, and in IL-2 secretion and proliferation, compared with T cells stimulated with wild-type allogeneic DCs (Fig. 1c). These results indicate that the absence of FcγRIIb can confer a more immunogenic phenotype on DCs and enhance their capacity to prime T cells.

Figure 1.

Dendritic cells (DCs) obtained from spleens of FcγRIIb-deficient mice display a mature phenotype and show enhanced immunogenicity. (a) Splenic DCs (CD11c-positive cells) derived from FcγRIIb-deficient and wild-type mice were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) for maturation markers CD40 and CD86. Representative FACS profiles from individual mice (filled histograms for wild-type mice and empty histograms for FcγRIIb-deficient mice) and graphs with mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) averages for each group are shown. (b) Interleukin (IL)-12 secretion, in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), by DCs obtained from spleens of FcγRIIb-deficient and wild-type mice. (c) Expression of CD69 (top panel, MFI averages), secretion of IL-2 (middle panel) and proliferation (bottom panel) by alloreactive T cells (BALB/c background) stimulated by DCs obtained from spleens of FcγRIIb-deficient or wild-type mice (C57BL/6 background). Phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) stimulation was included as a positive control. For CD69 up-regulation (top panel), representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) profiles from individual mice are shown. Data on each panel are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least three independent experiments [(a) *P< 0·05, Student’s t-test; (b and c) *P< 0·05, one-way analysis of variance (anova)]. WT, wild type.

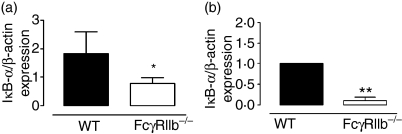

FcγRIIb-deficient mice with SLE show altered IκB-α expression

It has been suggested that FcγR signaling is mediated through activation of the NF-κB pathway.26 Considering that NF-κB activity can be modulated by the expression level of the inhibitor protein IκB-α,27 we determined the mRNA levels for this molecule in spleens of age-matched FcγRIIb-deficient and wild-type mice using real-time PCR. We observed that spleens from FcγRIIb-deficient mice showed significantly reduced expression of IκB-α mRNA, as compared with spleens of wild-type mice (Fig. 2a). To analyze in greater detail the expression of IκB-α, equivalent analyses were performed using DCs purified from the spleens of FcγRIIb-deficient or wild-type mice. Accordingly, DCs from FcγRIIb-deficient mice showed significantly reduced amounts of IκB-α mRNA (Fig. 2b). These data are consistent with the notion that FcγRIIb-deficient mice suffering from lupus have enhanced NF-κB activity in DCs, which could contribute to the mature phenotype observed.

Figure 2.

IκB-α expression in FcγRIIb-deficient and wild-type mice. (a) IκB-α mRNA expression in total spleen. (b) IκB-α mRNA expression in dendritic cells (DCs) purified from spleens obtained from wild-type or FcγRIIb-deficient mice. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least three independent experiments (*P< 0·05, **P< 0·01, Student’s t-test). WT, wild type.

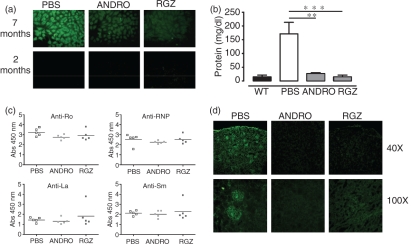

Treatment with NF-κB inhibitors can reduce the susceptibility to develop SLE

To assess the effect of NF-κB inhibition over susceptibility to develop SLE, FcγRIIb-deficient mice (6–8 weeks of age) were injected i.p. twice a week for 7 months with PBS, andrographolide or rosiglitazone. While andrographolide can covalently modify NF-κB, preventing its interaction with DNA,28 rosiglitazone is thought to promote the translocation of nuclear NF-κB back to the cell cytoplasm.29 ANAs, ENAs and proteinuria were evaluated on a monthly basis for FcγRIIb-deficient mice, which were treated either with vehicle (PBS, control) rosiglitazone or andrographolide. We observed that mice treated with NF-κB inhibitors had a lower incidence of ANAs when compared with PBS-treated mice (Fig. 3a). While in the control group almost 100% of mice became ANA positive around month 5, at this time-point only 50% of mice treated with rosiglitazone or andrographolide were ANA positive (Table 1). Moreover, we observed that 25% of mice treated with the NF-κB inhibitors were ANA negative up to month 8 of life. Thus, treatment with andrographolide and rosiglitazone significantly delayed the initiation of SLE symptoms in FcγRIIb-deficient mice. Furthermore, treatment with NF-κB inhibitors led to an 80% reduction in urine protein levels in FcγRIIb-deficient mice when compared with untreated mice (Fig. 3b). Finally, while FcγRII-deficient mice showed significantly higher anti-ENA titers compared with age-matched wild-type mice, treatment with andrographolide or rosiglitazone only led to a slight reduction in the titers of anti-Ro and anti-RNP, without altering the titers for anti-Sm and anti-La (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)inhibitors andrographolide (ANDRO) and rosiglitazone (RGZ) can reduce the severity of the symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in FcγRIIb-deficient mice. Representative results of anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs) (a), proteinuria (b), extractable nuclear antigens (ENAs) (c) and immunofluorescence detection of immune complex (IC) deposition in kidney sections (d), in treated and control FcγRIIb-deficient mice. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least three independent experiments [**P< 0·01, ***P< 0·001, one-way analysis of variance (anova)]. Abs, absorbance; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; WT, wild type.

Table 1.

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) inhibition can reduce the severity of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) symptoms in FcγRIIb-deficient mice

| Group | Percentage of positive ANAs | Proteinuria (mg/dl) (mean ± SE)*** | Initiation of Symptoms (mean ± SE)** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control FcγRIIb−/− | 100 | 158·2 ± 13·41 | 4·25 ± 0·24 |

| Andrographolide FcγRIIb−/− | 75 | 23·3 ± 1·46 | 7·5 ± 0·33 |

| Rosiglitazone FcγRIIb−/− | 75 | 18·5 ± 2·5 | 8·3 ± 0·38 |

Percentage positive anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs) and proteinuria (mg/dl) are shown after 7 months of treatment. Initiation of symptoms is expressed in months.

**P < 0·02 [analysis of variance (anova)].

***P < 0·0001 anova.

SE, standard error.

In view of the fact that the NF-κB inhibitors andrographolide and rosiglitazone were able to reduce ANAs, ENAs and proteinuria in FcγRIIb-deficient mice, we evaluated whether these drugs could also prevent glomerulonephritis, an important and characteristic symptom caused by the deposition of ICs at glomerulae. Glomerulonephritis in mice was evaluated by detecting IgG-containing ICs in kidney sections by immunofluorescence. As shown in Fig. 3(d), andrographolide and rosiglitazone-treated FcγRIIb-deficient mice showed significantly less IC deposition in glomerulae when compared with untreated mice. These data suggest that treatment with NF-κB inhibitors can prevent IC deposition and subsequent glomerulonephritis development in lupus-prone mice.

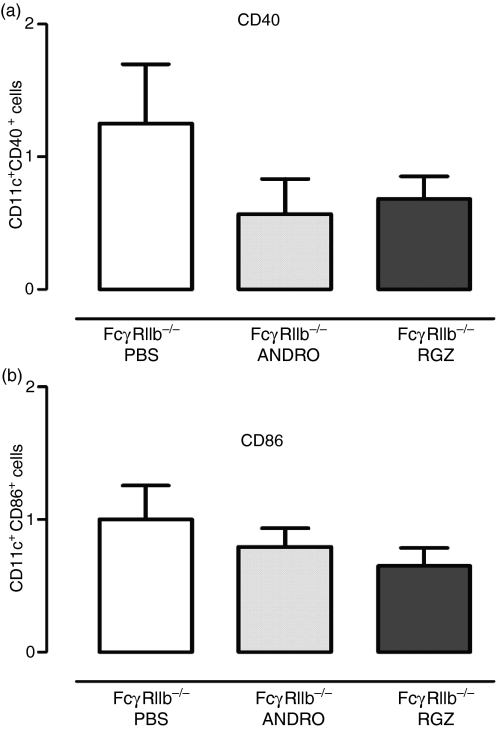

NF-κB inhibitors modulate the phenotype of FcγRIIb-deficient DCs

As described above, we observed increased expression of CD40 and CD86 in CD11c-positive cells in FcγRIIb−/− mice when compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 1). To evaluate whether NF-κB blockade by rosiglitazone and andrographolide could interfere with the process of DC maturation in vivo, we measured the expression of maturation markers in CD11c-positive cells in treated and non-treated FcγRIIb-deficient mice. After treatment with NF-κB inhibitors, spleen DCs exhibited a lower expression of the maturation markers CD40 and CD86 in treated animals, when compared with the PBS control group (Fig. 4). These data support the notion that treatment with NF-κB inhibitors promotes an immature phenotype on DCs derived from FcγRIIb-deficient mice, which could contribute to self-antigen tolerance in these animals.

Figure 4.

Maturation profile of dendritic cells (DCs) obtained from spleens of FcγRIIb-deficient mice treated with nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) inhibitors. Relative expression of costimulatory molecules CD40 (a) and CD86 (b) in splenic CD11c-positive cells after treatment with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (white), andrographolide (light gray) and rosiglitazone (dark grey). Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least two independent experiments.

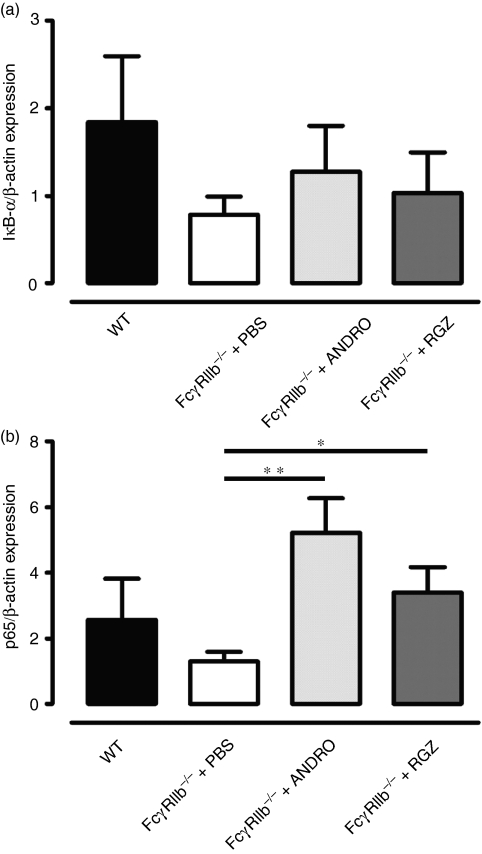

IκB-α expression is increased in FcγRIIb-deficient mice treated with NF-κB inhibitors

The data shown above indicated a decreased expression of IκB-α in spleen and DCs from FcγRIIb−/− mice, when compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 2). To evaluate the effects of andrographolide and rosiglitazone treatment on NF-κB activity, we measured IκB-α and p65 mRNA transcript levels in total RNA from the spleens of treated and non-treated FcγRIIb-deficient mice. Although not reaching statistical significance, animals treated with andrographolide or rosiglitazone showed increased IκB-α RNA levels when compared with untreated FcγRIIb-deficient animals (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, we observed that p65 mRNA levels were reduced in 8-month-old FcγRIIb-deficient mice compared with age-matched wild-type mice (Fig. 5b). In contrast, FcγRIIb-deficient mice treated with either andrographolide or roziglitazone showed higher mRNA levels for p65 than did untreated animals (Fig. 5b). Thus, treatment with these drugs can increase splenic mRNA IκB-α and p65 levels, which correlates with the reduced susceptibility of treated animals to develop SLE. These results suggest that treatment with andrographolide and rosiglitazone can contribute to normalize NF-κB activity, reducing inflammation in FcγRIIb-deficient mice.

Figure 5.

IκB-α (a) and p65 (b) mRNA expression in total spleens from FcγRIIb-deficient mice after treatment with nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) inhibitors. Graphs show real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) quantification of IκB-α (a) and p65 (b) in total mRNA from spleens of FcγRIIb-deficient mice treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), andrographolide or rosiglitazone. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments [*P< 0·05, **P< 0·01, one-way analysis of variance (anova)].

Discussion

DCs are professional antigen-presenting cells that play a fundamental role in the initiation and regulation of the adaptive immune response.8,30,31 The notion that DCs are capable of controlling immunity and tolerance has led to the hypothesis that pathogenic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as SLE may be driven by unabated DC activation. Inappropriate or constant activation of DCs presenting self-antigens may lead to a break in peripheral tolerance and initiate immunity to self.32 This idea is supported by the observation that administration of mature DCs loaded with autologous apoptotic cells can trigger autoimmune responses in genetically susceptible mice.33 The NF-κB family of transcription factors plays an important role in the activation, maturation and T-cell-activation capacity of DCs.11–13 Thus, alterations in NF-κB activity and regulation could account for inappropriate activation of DCs. Here we have evaluated the participation of NF-κB in SLE development in lupus-prone mice and showed that the NF-κB inhibitors andrographolide and rosiglitazone are able to reduce mice susceptibility to SLE and restore normal NF-κB function.

When the maturation status of DCs in lupus-prone mice was compared with that of wild-type mice, a significantly increased expression of the maturation markers CD40 and CD86 was observed for CD11c-positive DCs derived from spleens obtained from SLE mice (Fig. 1a). In addition, DCs obtained from FcγRIIb−/− mice secreted significantly more IL-12 in response to LPS than did DCs obtained from wild-type mice (Fig. 1b). A higher level of expression of co-stimulatory molecules and of IL-12 secretion could account for an increased T-cell-activation capacity of these DCs (Fig. 1c) and thus contribute to autoimmunity development in this mouse model of SLE. These results are supported by recent reports indicating that DCs from SLE patients showed increased expression of CD86.10,34 Increased expression of co-stimulatory molecules on the surface of DCs could contribute to SLE pathogenesis in FcγRIIb-deficient mice.

Elevated constitutive levels of active NF-κB are associated with chronic inflammatory diseases.35 As the NF-κB family of transcription factors is regulated by inhibitors such as IκB-α, we assessed the expression of this molecule in FcγRIIb-deficient and wild-type mice. Lower expression of IκB-α mRNA was observed in spleens and DCs derived from lupus-prone mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 2). To inhibit NF-κB activation, animals were treated with either andrographolide, a bicyclic diterpenoid lactone,36,37 or rosiglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) agonist, commonly used for the treatment of type II diabetes.38 It has been reported that andrographolide can exert an anti-inflammatory effect on immune cells through covalent binding to a reduced cysteine in position 62 of p50, thus preventing NF-κB oligonucleotide binding to p50, and inhibiting nuclear NF-κB transcriptional activity.28 Rosiglitazone has also been shown to inhibit NF-κB function.39 Some studies have suggested that PPARγ (a receptor for rosiglitazone) would induce NF-κB to shuttle from the cell nucleus back to the cytoplasm, thus preventing this transcription factor from binding to its DNA response elements.29 Other studies have shown that PPARγ stimulation retains NF-κB in the cytoplasm by increasing the expression of the IκB inhibitor.40,41 Consistent with those previous observations, we have shown that andrographolide and rosiglitazone inhibit NF-κB-mediated gene expression induced by LPS in murine MLE-12 cells transfected with an NF-κB reporter system.17 Several independent studies have shown that these two molecules can reduce the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in C57BL/6 mice.19,27 Here, we expand these findings by showing that these drugs can diminish SLE manifestations in the FcγRIIb-deficient mouse model. After treatment, we observed an 80% reduction in urine protein levels in FcγRIIb-deficient mice and a lower incidence of positive ANAs when compared with untreated FcγRIIb-deficient mice (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we observed that treatment with andrographolide and rosiglitazone delayed the initiation of symptoms (Table 1). Moreover, treatment with andrographolide and rosiglitazone reduced the severity of glomerulonephritis, as determined by immunofluorescence. Animals were also evaluated for ENAs during treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report where ENAs have been evaluated in FcγRIIb-deficient mice, showing that they present significant anti-Sm, anti-Ro, anti-RNP and anti-La titres. FcγRIIb-deficient mice treated with either andrographolide or rosiglitazone showed reduced titres for anti-Ro and anti-RNP (Fig. 3c).

Consistent with the clinical findings, after 7 months of treatment we observed reduced expression of co-stimulatory molecules in DCs from spleens derived from treated FcγRIIb-deficient animals compared with controls (Fig. 4). This finding supports the notion that treatment with NF-κB inhibitors could favor an immature phenotype on DCs and promote their tolerogenic capacity to self-antigens. Additionally, when IκB-α expression was evaluated we observed increased mRNA expression in treated FcγRIIb-deficient animals compared with the controls. Furthermore, p65 mRNA levels were reduced in FcγRIIb-deficient mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 5b). Similarly to IκB-α, treatment of FcγRIIb-deficient mice with either andrographolide or rosiglitazone significantly increased p65 mRNA levels. Recent reports have shown that IκB-α degradation rates are influenced by NF-κB binding42,43 and that p65 also can influence IκB-α expression levels.42 Thus, by increasing IκB-α and p65 mRNA levels in treated FcγRIIb-deficient animals, it seems that andrographolide and rosiglitazone can contribute to the re-establishment of normal NF-κB function. These results provide support to the notion that inhibition of NF-κB in FcγRIIb-deficient mice can reduce inflammation and delay SLE onset.

It is probable that alterations in the activity of NF-κB can influence the function of DCs and their capacity to regulate adaptive immunity. The findings reported here suggest that blockade of NF-κB activation can be used to down-modulate detrimental autoimmune responses. Our data are consistent with previous studies showing that NF-κB blockade can interfere with unwanted T-cell responses, such as seen in EAE19,44 and transplant rejection.45,46 Here, we provide new evidence suggesting that pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB in SLE-prone mice significantly reduced the incidence and severity of disease in mice. Our data support the notion that NF-κB blockade could be considered an important pharmacological approach to promote DC-mediated tolerance to autoantigens.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Margrit Wiesendanger for critical review of this manuscript and J. P. Zúñiga and J. P. Lezana for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants FONDECYT # 1050979 and # 1070352; Proyecto PBCT RED15; FONDEF D04I1075; INCO-CT-2006-032296 and Millennium Nucleus on Immunology and Immunotherapy (P04/030-F). MII is a VRAID fellow; and PAG and AAH are CONICYT fellows.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ANAs

anti-nuclear antibodies

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester

- DC

dendritic cell

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- ENAs

extractable nuclear antigens

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- ICs

immune complexes

- IL

interleukin

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- La

lupus anticoagulant antigen

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MLR

mixed lymphocyte reaction

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PHA

phytohaemagglutinin

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- RNP

ribonucleic protein

- Ro/SSA

Ro ribonucleoprotein particle/Sjögren’s syndrome A

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- Sm

Smith antigen

References

- 1.Croker JA, Kimberly RP. SLE: challenges and candidates in human disease. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:580–6. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yurasov S, Wardemann H, Hammersen J, Tsuiji M, Meffre E, Pascual V, Nussenzweig MC. Defective B cell tolerance checkpoints in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:703–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn BH. Antibodies to DNA. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1359–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mok CC, Lau CS. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:481–90. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.7.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:929–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nat Rev. 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung S. Good, bad and beautiful – the role of dendritic cells in autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:54–60. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9972(03)00066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Regulation of T cell immunity by dendritic cells. Cell. 2001;106:263–6. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banchereau J, Pascual V, Palucka AK. Autoimmunity through cytokine-induced dendritic cell activation. Immunity. 2004;20:539–50. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding D, Mehta H, McCune WJ, Kaplan MJ. Aberrant phenotype and function of myeloid dendritic cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2006;177:5878–89. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouaaz F, Arron J, Zheng Y, Choi Y, Beg AA. Dendritic cell development and survival require distinct NF-kappaB subunits. Immunity. 2002;16:257–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saccani S, Pantano S, Natoli G. Modulation of NF-kappaB activity by exchange of dimers. Mol cell. 2003;11:1563–74. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanetti M, Castiglioni P, Schoenberger S, Gerloni M. The role of relB in regulating the adaptive immune response. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;987:249–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan PH, Sagoo P, Chan C, et al. Inhibition of NF-kappa B and oxidative pathways in human dendritic cells by antioxidative vitamins generates regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:7633–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siebenlist U, Brown K, Claudio E. Control of lymphocyte development by nuclear factor-kappaB. Nat Rev. 2005;5:435–45. doi: 10.1038/nri1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iruretagoyena MI, Sepulveda SE, Lezana JP, Hermoso M, Bronfman M, Gutierrez MA, Jacobelli SH, Kalergis AM. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B enhances the capacity of immature dendritic cells to induce antigen-specific tolerance in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:59–67. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Sullivan BJ, Thomas R. CD40 ligation conditions dendritic cell antigen-presenting function through sustained activation of NF-kappaB. J Immunol. 2002;168:5491–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iruretagoyena MI, Tobar JA, Gonzalez PA, Sepulveda SE, Figueroa CA, Burgos RA, Hancke JL, Kalergis AM. Andrographolide interferes with T cell activation and reduces experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:366–72. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.072512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolland S, Ravetch JV. Spontaneous autoimmune disease in Fc(gamma)RIIB-deficient mice results from strain-specific epistasis. Immunity. 2000;13:277–85. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handa SS, Sharma A. Hepatoprotective activity of andrographolide from Andrographis paniculata against carbontetrachloride. Indian J Med Res. 1990;92:276–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bueno SM, Gonzalez PA, Carreno LJ, Tobar JA, Mora GC, Pereda CJ, Salazar-Onfray F, Kalergis AM. The capacity of Salmonella to survive inside dendritic cells and prevent antigen presentation to T cells is host specific. Immunology. 2008;124:522–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez PA, Carreno LJ, Coombs D, Mora JE, Palmieri E, Goldstein B, Nathenson SG, Kalergis AM. T cell receptor binding kinetics required for T cell activation depend on the density of cognate ligand on the antigen-presenting cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4824–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500922102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrada AA, Contreras FJ, Tobar JA, Pacheco R, Kalergis AM. Immune complex-induced enhancement of bacterial antigen presentation requires Fcgamma receptor III expression on dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13402–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700999104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Schuler G, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of interleukin 10-producing, nonproliferating CD4(+) T cells with regulatory properties by repetitive stimulation with allogeneic immature human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1213–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banki Z, Kacani L, Mullauer B, et al. Cross-linking of CD32 induces maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells via NF-kappa B signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2003;170:3963–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feinstein DL, Galea E, Gavrilyuk V, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists prevent experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:694–702. doi: 10.1002/ana.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia YF, Ye BQ, Li YD, et al. Andrographolide attenuates inflammation by inhibition of NF-kappa B activation through covalent modification of reduced cysteine 62 of p50. J Immunol. 2004;173:4207–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly D, Campbell JI, King TP, Grant G, Jansson EA, Coutts AG, Pettersson S, Conway S. Commensal anaerobic gut bacteria attenuate inflammation by regulating nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of PPAR-gamma and RelA. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:104–12. doi: 10.1038/ni1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ronnblom L, Eloranta ML, Alm GV. Role of natural interferon-alpha producing cells (plasmacytoid dendritic cells) in autoimmunity. Autoimmunity. 2003;36:463–72. doi: 10.1080/08916930310001602128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bave U, Magnusson M, Eloranta ML, Perers A, Alm GV, Ronnblom L. Fc gamma RIIa is expressed on natural IFN-alpha-producing cells (plasmacytoid dendritic cells) and is required for the IFN-alpha production induced by apoptotic cells combined with lupus IgG. J Immunol. 2003;171:3296–302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Decker P, Kotter I, Klein R, Berner B, Rammensee HG. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells over-express CD86 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2006;45:1087–95. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajagopal S, Kumar RA, Deevi DS, Satyanarayana C, Rajagopalan R. Andrographolide, a potential cancer therapeutic agent isolated from Andrographis paniculata. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2003;3:147–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-4117.2003.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gabrielian ES, Shukarian AK, Goukasova GI, Chandanian GL, Panossian AG, Wikman G, Wagner H. A double blind, placebo-controlled study of Andrographis paniculata fixed combination Kan Jang in the treatment of acute upper respiratory tract infections including sinusitis. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:589–97. doi: 10.1078/094471102321616391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee CH, Olson P, Evans RM. Minireview: lipid metabolism, metabolic diseases, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2201–7. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohanty P, Aljada A, Ghanim H, et al. Evidence for a potent antiinflammatory effect of rosiglitazone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2728–35. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klotz L, Schmidt M, Giese T, Sastre M, Knolle P, Klockgether T, Heneka MT. Proinflammatory stimulation and pioglitazone treatment regulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy controls and multiple sclerosis patients. J Immunol. 2005;175:4948–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.4948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Setoguchi K, Misaki Y, Terauchi Y, Yamauchi T, Kawahata K, Kadowaki T, Yamamoto K. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma haploinsufficiency enhances B cell proliferative responses and exacerbates experimentally induced arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1667–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI13202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Dea EL, Barken D, Peralta RQ, Tran KT, Werner SL, Kearns JD, Levchenko A, Hoffmann A. A homeostatic model of IkappaB metabolism to control constitutive NF-kappaB activity. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3 doi: 10.1038/msb4100148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathes E, O’Dea EL, Hoffmann A, Ghosh G. NF-kappaB dictates the degradation pathway of IkappaBalpha. EMBO J. 2008;27:1357–67. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma L, Qian S, Liang X, et al. Prevention of diabetes in NOD mice by administration of dendritic cells deficient in nuclear transcription factor-kappaB activity. Diabetes. 2003;52:1976–85. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saemann MD, Kelemen P, Bohmig GA, Horl WH, Zlabinger GJ. Hyporesponsiveness in alloreactive T-cells by NF-kappaB inhibitor-treated dendritic cells: resistance to calcineurin inhibition. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1448–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tomasoni S, Aiello S, Cassis L, et al. Dendritic cells genetically engineered with adenoviral vector encoding dnIKK2 induce the formation of potent CD4+ T-regulatory cells. Transplantation. 2005;79:1056–61. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000161252.17163.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]