Abstract

In the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis, the fungal symbiont colonizes root cortical cells, where it establishes differentiated hyphae called arbuscules. As each arbuscule develops, the cortical cell undergoes a transient reorganization and envelops the arbuscule in a novel symbiosis-specific membrane, called the periarbuscular membrane. The periarbuscular membrane, which is continuous with the plant plasma membrane of the cortical cell, is a key interface in the symbiosis; however, relatively little is known of its composition or the mechanisms of its development. Here, we used fluorescent protein fusions to obtain both spatial and temporal information about the protein composition of the periarbuscular membrane. The data indicate that the periarbuscular membrane is composed of at least two distinct domains, an “arbuscule branch domain” that contains the symbiosis-specific phosphate transporter, MtPT4, and an “arbuscule trunk domain” that contains MtBcp1. This suggests a developmental transition from plasma membrane to periarbuscular membrane, with biogenesis of a novel membrane domain associated with the repeated dichotomous branching of the hyphae. Additionally, we took advantage of available organelle-specific fluorescent marker proteins to further evaluate cells during arbuscule development and degeneration. The three-dimensional data provide new insights into relocation of Golgi and peroxisomes and also illustrate that cells with arbuscules can retain a large continuous vacuolar system throughout development.

In order to survive on land, plants have evolved many strategies to take up essential nutrients from the soil. One important mechanism for nutrient acquisition that is shared by a majority of plant phyla is the arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbiosis (Bonfante and Genre, 2008; Parniske, 2008). At a functional level, the AM symbiosis is characterized by nutrient exchange, primarily phosphate and nitrogen, from obligate biotrophic fungi of the phylum Glomeromycota to the plant and reciprocal carbon transfer from the plant to the fungus (Parniske, 2008; Smith and Read, 2008). The ecological importance of the AM symbiosis is illustrated by its ancient origin, estimated at 460 million years ago and coincident with plant colonization of land (Remy et al., 1994; Redeker et al., 2000; Bonfante and Genre, 2008), its evolutionary conservation in approximately 80% of land plant species, and experimental data showing the prominent role of the symbiosis in nutrient uptake and improvement in plant health (Smith et al., 2003; Javot et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007; Smith and Read, 2008).

During AM symbiosis, the fungus grows within plant roots both intracellularly and intercellularly and subsequently colonizes the cortical cells, where it forms highly branched hyphae called arbuscules (Bonfante-Fasolo, 1984). Arbuscules are the site of mineral nutrient transfer to the plant and potentially the site of carbon acquisition by the fungus. Although arbuscules form within the cortical cells, they remain separated from the plant cell cytoplasm by a plant-derived membrane called the periarbuscular membrane. The resulting interface, delimited by the periarbuscular membrane, establishes a large surface area within the relatively small volume of a cell, which appears optimal for nutrient transfer. Arbuscules are transient structures, and following development, which is estimated to take 2 to 4 d, they collapse and degenerate. The complete arbuscule life cycle is estimated to take 7 to 10 d, although this varies depending on the symbionts involved (Alexander et al., 1989; Brown and King, 1991).

Arbuscule development is accompanied by drastic reorganization of the cortical cell. As the penetrating hypha enters the cortical cell, the plant plasma membrane is not breached but invaginates and is then extended to form the periarbuscular membrane (Cox and Sanders, 1974; Bonfante-Fasolo, 1984; Toth and Miller, 1984). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies showed accumulation of cytoplasm and organelles, including endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi bodies, plastids, and mitochondria, in the area around arbuscule branches (Cox and Sanders, 1974; Scannerini and Bonfante-Fasolo, 1982). In addition, the tonoplast invaginates, and the TEM micrographs revealed the presence of multiple small vacuole compartments (Cox and Sanders, 1974; Toth and Miller, 1984), which led to the interpretation that arbuscule development is accompanied by fragmentation of the plant central vacuole (Scannerini and Bonfante-Fasolo, 1982; Bonfante and Perotto, 1995; Gianinazzi-Pearson, 1996; Harrison, 1999). Immunolocalization studies showed that arbuscule development is accompanied by reorganization of plant cytoskeletal components that surround the developing arbuscule and likely directs membrane deposition and organelle accumulation (Genre and Bonfante, 1997, 1998; Blancaflor et al., 2001). Recently, live-cell imaging with fluorescently tagged proteins has been used to follow the rearrangement of plastids (Fester et al., 2001), mitochondria (Lohse et al., 2005), and ER (Genre et al., 2008) in cells with arbuscules. It has also been proposed that cellular reorganization in cortical cells precedes and guides arbuscule development in a similar manner to the prepenetration apparatus that facilitates AM fungal penetration into epidermal cells (Genre et al., 2005, 2008).

The periarbuscular membrane has been suggested to arise by de novo membrane synthesis (Bonfante and Perotto, 1995; Gianinazzi-Pearson, 1996); however, evidence for the origin of the membrane material and the secretion pathway is lacking. TEM studies have shown that the periarbuscular membrane is continuous with the plasma membrane, but relatively little is known of its lipid or protein composition. Phosphate transporters that are expressed exclusively in AM roots in cells with arbuscules have been cloned from monocots and dicots (Harrison et al., 2002; Paszkowski et al., 2002; Glassop et al., 2005; Nagy et al., 2005; Bucher, 2007) including Medicago truncatula, where the phosphate transporter, MtPT4, was shown to reside exclusively in the periarbuscular membrane (Harrison et al., 2002). In addition, H+-ATPases, which create proton gradients necessary for secondary active transporters such as MtPT4, are induced in AM roots and have been localized to the periarbuscular membrane. In contrast, the H+-ATPase activity of the plasma membrane of cortical cells is much lower than that of the periarbuscular membrane (Gianinazzi-Pearson et al., 1991, 2000; Bonfante and Perotto, 1995; Krajinski et al., 2002). These examples provided the first evidence that the periarbuscular membrane differs from the plasma membrane.

In a comparison of membrane proteins from AM and non-AM M. truncatula roots, Valot et al. (2006) identified two candidates present exclusively in mycorrhizal roots: a H+-ATPase, MtHA1, and a blue copper-binding protein, MtBcp1, which is predicted to be posttranslationally modified with a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) moiety. GPI anchors, which are added to secreted proteins in the ER after cleavage of a C-terminal peptide signal, result in localization of modified proteins to the extracellular leaflet of the plasma membrane (Eisenhaber et al., 2003). Consistent with detection of the protein in AM roots, MtBcp1 transcript levels are elevated in AM roots (Liu et al., 2003), and a transcriptional fusion of the promoter to the UidA reporter showed expression in cortical cells with arbuscules and in adjacent noncolonized cortical cells (Hohnjec et al., 2005).

Development and maintenance of arbuscules and the periarbuscular membrane is crucial to the symbiosis and influences its longevity and function. To begin to determine the mechanisms by which a root cortical cell reorganizes its structure to develop the periarbuscular membrane, we prepared fluorescently tagged M. truncatula protein markers that are expressed exclusively in the AM symbiosis and label the periarbuscular membrane. The markers are suitable for live-cell imaging and provide, to our knowledge, the first evidence of distinct domains within the periarbuscular membrane. Additionally, we used available fluorescent marker protein fusions to monitor plant membranes and plant organelle distribution during arbuscule development and degeneration in M. truncatula cells. The data complement the earlier TEM studies, and three-dimensional reconstructions offer new insights into cellular reorganization during arbuscule development.

RESULTS

MtPT4-GFP Provides a Live-Cell Marker of the Periarbuscular Membrane and Defines an Arbuscule Branch Domain of the Periarbuscular Membrane

The M. truncatula phosphate transporter MtPT4 is expressed specifically in cortical cells with arbuscules and was shown by immunolocalization to reside exclusively in the periarbuscular membrane (Harrison et al., 2002). In order to develop a fluorescent marker of the periarbuscular membrane suitable for live-cell imaging, we created an MtPT4-GFP fusion protein and determined whether this would localize to the periarbuscular membrane. An expression vector, pMtPT4:MtPT4-GFP, was constructed by fusing the promoter region of MtPT4 (Harrison et al., 2002) to the coding sequences of MtPT4 and GFP, resulting in a chimeric protein with GFP fused to the C terminus of MtPT4. This construct was introduced into M. truncatula roots by Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated root transformation (Boisson-Dernier et al., 2001). After colonization by the AM fungus Glomus versiforme, roots expressing GFP were excised and bisected longitudinally, and undisrupted cells in layers below the section plane were imaged by confocal microscopy. pMtPT4:MtPT4-GFP shows cell-specific expression in cortical cells with arbuscules, and the fusion protein is localized to the periarbuscular membrane (Fig. 1). Specifically, MtPT4-GFP was observed on the periarbuscular membrane in the region surrounding the branches of midsize and mature arbuscules, but there was no GFP signal on the membrane surrounding the trunk of arbuscules (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S1). The fusion protein was first visible when the arbuscules reached a developmental stage with several branches. These results are consistent with previous immunolocalization data that indicated that MtPT4 protein surrounded branches of arbuscules but not on arbuscule trunks or in very young arbuscules with a few branches (Harrison et al., 2002). As reported previously, MtPT4 is not located in the plasma membrane, and the MtPT4-GFP marker is consistent with this and did not label the plasma membrane. In the previous immunolocalization studies, MtPT4 protein was not detected around arbuscules undergoing collapse. In pMtPT4:MtPT4-GFP roots with collapsing arbuscules, a “haze” of GFP signal was observed throughout the cell but was excluded from the region of the arbuscule in a pattern that indicates GFP in the vacuole (Tamura et al., 2003; Kleine-Vehn et al., 2008; Supplemental Fig. S1). Together with the previous immunolocalization results, these data suggest that MtPT4 is degraded during arbuscule collapse.

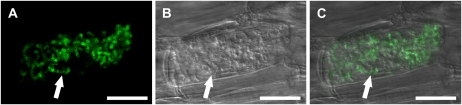

Figure 1.

Localization of MtPT4-GFP to the periarbuscular membrane. M. truncatula roots were transformed with pMtPT4:MtPT4-GFP and colonized with G. versiforme. A, GFP signal. B, Differential interference contrast bright-field image. C, Overlay. The images show that the fusion protein localizes to the periarbuscular membrane around the branches of a mature arbuscule (arrows). A and C are projections of eight optical sections on the z axis taken at 0.22-μm intervals. B is a single differential interference contrast section to best define structural outlines. Zoom = 2.0; bars = 20 μm.

MtBcp1 Is Localized in the Plasma Membrane and the Periarbuscular Membrane around the Arbuscule Trunk

To further evaluate the protein composition of the periarbuscular membrane, we set out to find additional proteins that would localize to this membrane. Based on previous array data and promoter analyses (Liu et al., 2003; Hohnjec et al., 2005), MtBcp1 is induced specifically in the root cortex in colonized regions of AM roots. While the specific function of MtBcp1 is unknown, the protein is predicted to be posttranslationally modified with a GPI anchor (Eisenhaber et al., 2003). GPI modifications are known to confer polar localization to proteins in animals (Brown et al., 1989; Lisanti et al., 1989) and plants (Schindelman et al., 2001; Roudier et al., 2005), and loss of plant genes involved in GPI biosynthesis results in defects in polar developmental processes (Lalanne et al., 2004; Gillmor et al., 2005). As development of the periarbuscular membrane likely involves polarized growth, we selected MtBcp1 as a potential candidate for a periarbuscular membrane resident protein.

To determine the subcellular localization of MtBcp1, GFP was translationally fused to the coding sequence of MtBcp1 and expressed under its endogenous promoter (Hohnjec et al., 2005). Because MtBcp1 has a predicted cleaved secretion signal, pMtBcp1:GFP-MtBcp1 was created by fusing GFP within the MtBcp1 open reading frame downstream of the cleavage site, resulting in an N-terminal fusion of GFP to the mature form of the MtBcp1 protein. This approach has been used successfully for tagging a GPI-anchored protein in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum; Sun et al., 2004).

Following transformation into M. truncatula roots and colonization with G. versiforme, expression of pMtBcp1:GFP-MtBcp1 was observed in cortical cells with arbuscules and also in cortical cells adjacent to fungal hyphae (Fig. 2, A–C). This is consistent with previous studies of transcriptional MtBcp1 promoter:UidA fusions (Hohnjec et al., 2005). In cortical cells without arbuscules, GFP signal was seen around the periphery of the cell, consistent with location in the plasma membrane, which is expected for a GPI-anchored protein (Fig. 2, A–C). During colonization of M. truncatula roots, G. versiforme shows linear, intercellular and intracellular hyphal growth within the cortex; in cortical cells harboring an intracellular hypha, we observed GFP signal on the plasma membrane and also around the hypha (Fig. 2, D–F; Supplemental Fig. S2). This suggests that the membrane that surrounds the hypha, termed the perihyphal membrane, shares characteristics of the plasma membrane. The perihyphal membrane is continuous with the plasma membrane, and the GFP signal is likewise continuous (Supplemental Fig. S2). In cells with arbuscules, the GFP signal was again visible on the plasma membrane, and in addition, there was a clear signal on the periarbuscular membrane around the arbuscule trunks. Occasionally, the initial thick, dichotomous branches of a very young arbuscule showed some staining (data not shown), but there was no GFP signal around the branches of the midsize or mature arbuscules (Fig. 2, D–F). Thus, the location of MtBcp1 is opposite to that of MtPT4. These results suggest that the periarbuscular membrane, defined previously as the membrane that surrounds the arbuscule, is in fact composed of distinct membrane domains: a domain surrounding the arbuscule trunk, which contains MtBcp1 and shares features with the plasma membrane, and a domain surrounding arbuscule branches, which contains MtPT4 and is likely active in nutrient exchange.

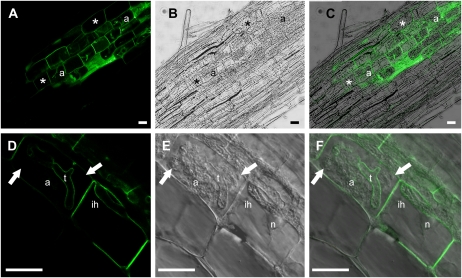

Figure 2.

Localization of GFP-MtBcp1 to the plasma membrane, perihyphal membrane, and periarbuscular membrane. M. truncatula roots were transformed with pMtBcp1:GFP-MtBcp1 and colonized with G. versiforme. A and D, GFP signal. B and E, Bright-field images. C and F, Overlays. A to C, GFP-MtBcp1 is present in the plasma membrane of root cortical cells with arbuscules (a) and cells without arbuscules (asterisks). Zoom = 2.2. D to F, GFP-MtBcp1 labels plasma membrane and periarbuscular membrane around an arbuscule trunk (t) in a cell with an arbuscule, but the signal is absent from the arbuscule branches (arrows). GFP-MtBcp1 signal also surrounds intracellular hyphae (ih). n, Nucleus. Zoom = 2.9. A to C, E, and F are single optical sections. D is a projection of four optical sections on the z axis taken at 0.4-μm intervals. Bars = 20 μm.

A Plasma Membrane Marker Displays Partial Overlap with MtBcp1-GFP

To determine whether a typical plasma membrane protein would also localize to the perihyphal membrane and trunk domain of the periarbuscular membrane, we evaluated expression of a plasma membrane aquaporin. An Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) aquaporin, AtPIP2a, with a C-terminal fusion to the red fluorescent protein mCherry, driven by the constitutive 35S promoter (p35s:PIP2a-mCherry; Nelson et al., 2007), was transformed into M. truncatula roots. In order to mark regions of fungal colonization, the transformation was performed in a transgenic M. truncatula line expressing GFP under the MtSCP1 promoter, which is specifically induced in cortical cells surrounding fungal colonization (Liu et al., 2003; Gomez et al., 2009). The free GFP signal enabled visualization of cytoplasm and nuclei in cells with arbuscules and neighboring cortical cells (Supplemental Fig. S3).

In noncolonized cortical cells, the AtPIP2a-mCherry marker labeled the plasma membrane as expected (Fig. 3, A–C). In cells with intracellular hyphae, AtPIP2a-mCherry labeled the plasma membrane and showed a strong perihyphal signal similar to that of GFP-MtBcp1 (Fig. 3, D–F; Supplemental Fig. S4). In cells with arbuscules, AtPIP2a-mCherry labeled the plasma membrane, and in most but not all cells, it displayed signal on the periarbuscular membrane at the base of the arbuscule trunks (Fig. 3). AtPIP2a-mCherry did not label the periarbuscular membrane around the arbuscule branches. This labeling pattern is essentially the same as that of GFP-MtBcp1, but the relative signal intensities differed slightly. GFP-MtBcp1 showed a stronger relative signal around the trunk domain of the arbuscules than that of AtPIP2a-mCherry. Taken together, the protein markers suggest that the perihyphal membrane and the periarbuscular trunk domains resemble the plasma membrane, while the branch domain of the periarbuscular membrane is clearly distinct. These data are consistent with a developmental transition in the periarbuscular membrane and suggest that biogenesis of a unique domain of the periarbuscular membrane may be coordinated with the repeated dichotomous branching of the fungal hyphae that creates the arbuscule.

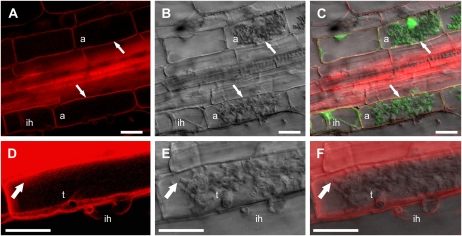

Figure 3.

Localization of a plasma membrane marker to the plasma membrane and to the periarbuscular membrane around arbuscule trunks. Roots of stable transgenic M. truncatula MtSCP1-GFP plants were transformed with the plasma membrane marker construct 35S:AtPIP2a-mCherry. The green signal in C is free GFP expressed from the MtSCP1 promoter. A, AtPIP2a-mCherry. B, Differential interference contrast. C, Overlay. Zoom = 1.7. In A to C, AtPIP2a signal is visible on the plasma membrane of cells with and without arbuscules (a) and also on the perihyphal membrane surrounding intracellular hyphae (ih). D to F, Enlarged images of the lower arbuscule from A to C. The enlarged images show AtPIP2a signal on the periarbuscular membrane surrounding the trunk (t) and surrounding an intracellular hypha in the neighboring cell, but signal is absent from arbuscule branches (arrows). Zoom = 2.6. Signal is continuous from the plasma membrane to the arbuscule trunk. A to C and E are single optical sections. D is a projection of 11 optical sections taken at 0.71-μm intervals along the z axis assembled and modified using VOLOCITY software. F is an overlay of D and E created using Photoshop. Bars = 20 μm.

Organelle Markers Uncover Cellular Dynamics in Live Cells

To gain insights into cellular processes that may contribute to periarbuscular membrane formation, we utilized this experimental platform to study the distribution of organelles in cells containing arbuscules at different stages of development. Previously, TEM studies have provided high-resolution images of organelles in colonized cortical cells. Live imaging offers an opportunity to extend these analyses and, in particular, enables additional three-dimensional information to be obtained.

mCherry fluorescent protein fusions that act as markers of the plasma membrane (see above), ER, Golgi, peroxisome, and vacuole have been developed and are well characterized in Arabidopsis (Nelson et al., 2007). Some have also been used in other species where the fidelity has been confirmed, including M. truncatula for analysis of the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis (Fournier et al., 2008) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) BY-2 cells (Nebenfuhr et al., 1999). These fusion proteins, expressed under the 35S promoter, were transformed into roots of the transgenic MtSCP1:GFP M. truncatula line.

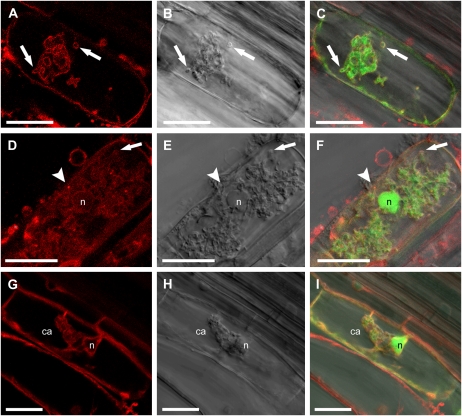

In plants expressing the ER marker, mCherry signal was observed in a characteristic reticulate pattern at the periphery of root cells as well as a perinuclear ring (Supplemental Fig. S5). In a cell containing a hypha with a single dichotomous branch, the hypha was surrounded by a layer of ER and cytoplasm and the nucleus was located close to the young arbuscule, as described previously (Fig. 4, A–C; Balestrini et al., 1992; Genre et al., 2008). While in some cells, the ER marker indicated significant accumulation of ER surrounding young arbuscules, in others, the ER appeared appressed to arbuscules (compare Fig. 4, A–C, and Supplemental Fig. S5, E–H). In cells with mature arbuscules, ER was distributed throughout the space surrounding the arbuscule, and perinuclear ER was also prominent (Fig. 4, D–F). In cells with degenerating arbuscules, the association of arbuscule, ER, and plant nucleus was maintained (Fig. 4, G–I). These patterns are consistent with the active secretion directed toward the periarbuscular membrane throughout arbuscule development and degeneration and may indicate a requirement for secreted proteins not only to build the periarbuscular membrane and the interfacial matrix but also to deconstruct it during the degeneration phase.

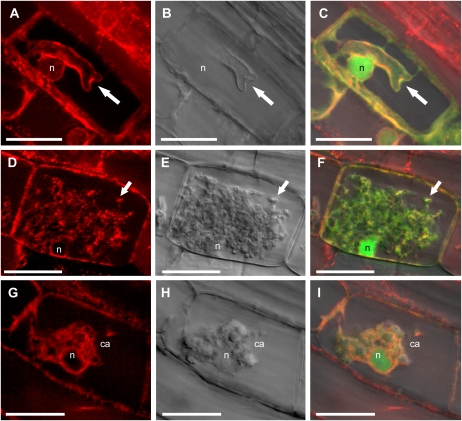

Figure 4.

Localization of ER in root cortical cells containing arbuscules at different stages of development. Roots of a stable transgenic M. truncatula MtSCP1-GFP plant were transformed with 35S:mCherry-HDEL. A, D, and G, mCherry-HDEL labeling the ER in cells with arbuscules. B, E, and H, Differential interference contrast of single z sections. C, F, and I, Overlay including free GFP (green signal) expressed from the MtSCP1 promoter. A to C show a hypha (arrows) making the first dichotomous branch of arbuscule development, surrounded by a thin layer of cytoplasm and ER. A and C are projections of 32 optical sections taken at 0.3-μm intervals along the z axis. Zoom = 4.3. Perinuclear ER surrounds the nucleus (n). D to F, Single confocal sections of a mature arbuscule surrounded by ER and cytoplasm. An arbuscule branch is highlighted with an arrow. Zoom = 4.6. G to I, ER and cytoplasm surround a collapsing arbuscule (ca) with closely associated plant nucleus. G and I are projections of four optical sections taken at 0.4-μm intervals on the z axis. Zoom = 4.7; bars = 20 μm.

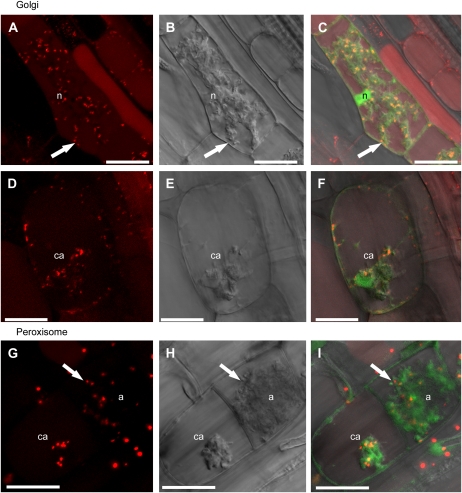

In noncolonized root cells, the Golgi marker labeled small, endosomal bodies located at the cell periphery, as described in Arabidopsis cells (Supplemental Fig. S6). A diffuse signal, potentially throughout the vacuole, was also observed, which suggests that this marker may be somewhat unstable in M. truncatula roots (Fig. 5, A–C). In cells with young and mature arbuscules, almost all of the Golgi bodies relocated to the area surrounding arbuscule branches and were was rarely present at the cell periphery (Fig. 5, A–C). Golgi bodies did not appear to associate with the extreme tips of arbuscule branches but rather along the sides of hyphae behind branching nodes (Fig. 5, A–C; Supplemental Fig. S6). In cells with degenerating arbuscules, some Golgi bodies clustered around the arbuscule (Fig. 5, D–F), but a significant proportion of the population relocated to the periphery of the cell.

Figure 5.

Golgi and peroxisome distribution in cells containing arbuscules at different stages of development. Roots of stable transgenic line M. truncatula MtSCP1-GFP were transformed with 35S:GmMan1-mCherry (A–F) and 35S:mCherry-PTS1 (G–I). A, C, D, and F, GmMan1-mCherry Golgi marker. G and I, mCherry-PTS1 peroxisome marker. B, E, and H, Differential interference contrast of single z sections. C, F, and I are overlays including free GFP expressed from the MtSCP1 promoter (green). A to C, Golgi cluster around the branches of a mature arbuscule and are generally absent from the cell periphery. Single arbuscule branch (arrows) and nucleus (n) are indicated. A and C are projections of 11 optical sections taken at 0.27-μm intervals on the z axis. Zoom = 3.5. D to F, Golgi surround a collapsing arbuscule (ca) and cell periphery. These are single optical sections. Zoom = 3.5. G to I, Peroxisomes are closely associated with mature arbuscules (a; arrows) and cluster around a collapsing arbuscule. G and I are projections of five optical sections taken at 0.25-μm intervals on the z axis. Zoom = 4.2; bars = 20 μm.

A peroxisome marker labeled bodies slightly larger than Golgi in cortical cells (Supplemental Fig. S7), as described previously for Arabidopsis epidermal cells (Nelson et al., 2007). In colonized cortical cells, peroxisomes localized predominantly adjacent to the arbuscules, in a pattern similar to the Golgi marker (Fig. 5, G–I; Supplemental Fig. S7). In contrast with the Golgi, in cells with degenerating arbuscules, the majority of the peroxisomes remained close to the degenerating arbuscule and almost entirely surrounded the degenerating mass (Fig. 5, G–I).

In nonmycorrhizal roots, the tonoplast marker revealed a large central vacuole appressed to the cell periphery with space representing nuclear invaginations (Supplemental Fig. S8). In mycorrhizal roots, cortical cells anticipating fungal penetration had repositioned nuclei and cytoplasmic accumulations, consistent with previous reports (Balestrini et al., 1992; Genre et al., 2008). During this response, cytoplasmic strands formed through the cell and were surrounded by tonoplast membrane (Supplemental Fig. S8). In cells with young arbuscules, the tonoplast surrounded the cytoplasm and nucleus, which are directly appressed to the arbuscule (Fig. 6, A–C), suggesting that the large vacuole is maintained but invaginated to allow for arbuscule development. In cells harboring fully developed arbuscules, the tonoplast marker labeled discrete spots that may represent fragmented tonoplast; however, there also appeared to be a continuous tonoplast surrounding arbuscule structures (Fig. 6, D–F), suggesting that the vacuole does not entirely fragment. Upon arbuscule turnover, the tonoplast continued to surround the collapsing fungus until the vacuole regained its original large central conformation (Fig. 6, G–I).

Figure 6.

The tonoplast membrane envelops arbuscules. Roots of stable transgenic line M. truncatula MtSCP1-GFP were transformed with 35S:γ-TIP-mCherry. A, D, and F, γ-TIP-mCherry tonoplast marker. B, E, and H, Differential interference contrast of single z sections. C, F, and I, Overlays including free GFP expressed under the SCP1 promoter (green). A to C, Tonoplast membrane surrounds the thin layer of plant cytoplasm appressed to an arbuscule (arrows). These are single confocal sections. Zoom = 3.3. D to F, A mature arbuscule. Some distinct points of fluorescence were observed, possibly representing fragmented vacuoles (arrowheads). However, it appeared that a continuous tonoplast surrounded the mature arbuscule (arrows) and plant nucleus (n). D and F are projections of three optical sections taken at 0.55-μm intervals on the z axis. Zoom = 2.6. G to I, Collapsing arbuscule (ca), nucleus, and cytoplasmic strands surrounded by tonoplast membrane. Bars = 20 μm.

To illustrate that the root cells selected for imaging remain viable beyond the typical 30-min time period used for our experiments, we prepared roots samples expressing free GFP driven from the MtSCP1 promoter and imaged a single cell harboring a young arbuscule for over 3 h (Supplemental Fig. S9; Supplemental Movie S1). Throughout the experiment, the cell showed a strong GFP signal and active cytoplasmic streaming, even 3 h after sample preparation (Supplemental Movie S1).

DISCUSSION

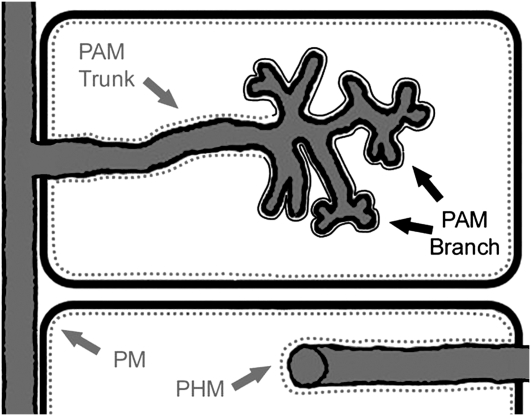

The periarbuscular membrane separates the arbuscule and the root cortical cell and plays a central role in nutrient exchange between the symbionts (Harrison, 2005; Parniske, 2008). As this membrane forms transiently in the inner cortical cells of the root, it is not readily accessible. Consequently, many membrane analysis techniques cannot be applied, and the composition of the membrane and its mode of development are not well understood. Fluorescent protein markers provide a way to visualize the periarbuscular membrane and also to evaluate its protein composition. Here, we developed two AM-specific marker protein fusions, MtPT4-GFP and GFP-MtBcp1. Both are driven by their native promoters so that protein location is observed in its correct spatial and temporal context. Consistent with previous immunolocalization studies (Harrison et al., 2002), the MtPT4-GFP marker is localized exclusively in the periarbuscular membrane in the region around the hyphal branches, and there is no signal arising from the membrane around the arbuscule trunk or from the plasma membrane of the cell. In contrast, GFP-tagged MtBcp1 shows the opposite location and labels the plasma membrane of cortical cells before and during the growth of arbuscules and the periarbuscular membrane surrounding arbuscule trunks, but not arbuscule branches (Fig. 7). The periarbuscular membrane is defined as a membrane that surrounds an arbuscule and is continuous with the plasma membrane. The finding that MtBcp1 and the plasma membrane marker AtPIP2a both label plasma membranes, perihyphal membranes, and trunk domains of the periarbuscular membrane suggests that transition to a periarbuscular membrane that is functionally distinct from the plasma membrane may not occur until an arbuscule develops branches. Whether the MtBcp1 and AtPIP2a proteins that label the trunk domain are newly synthesized and secreted or redistribute from the plasma membrane is not known, but our data do show continuous localization of these markers from plasma membrane to arbuscule trunk domain. The strong presence of MtBcp1 on trunks and the weaker relative signal of AtPIP2a also suggest that additional mechanisms may regulate protein composition in this membrane. Interestingly, Fournier and colleagues (2008) showed that AtPIP2a labels the infection thread membrane that develops to allow entry of Rhizobium bacteria into the root for nodule formation. In legumes, the genetic pathways that regulate symbioses with AM fungi and Rhizobium bacteria overlap, and it is possible that aspects of membrane synthesis and deposition that lead to microbial accommodation are also shared.

Figure 7.

Illustration of proposed periarbuscular membrane domains. Two cortical cells are depicted, with an arbuscule (top) and an intracellular hypha (bottom) shown in gray. Fluorescently tagged MtBcp1 and AtPIP2a mark the plasma membrane (PM), perihyphal membrane (PHM), and the trunk region of the periarbuscular membrane (PAM), represented by the gray dashed line. MtPT4 localizes on the branch region of the periarbuscular membrane, complementary to the trunk domain, represented by the unbroken black line.

Arbuscules share similar functions to the haustoria formed by biotrophic pathogens, and the interface of each with its respective host cells is morphologically analogous. Haustoria are surrounded by a plant extrahaustorial membrane (EHM) that is believed to mediate transport of nutrients to the pathogen (O'Connell and Panstruga, 2006). Studies of the interaction between Arabidopsis and a powdery mildew pathogen found that plasma membrane markers, including AtPIP2a, did not localize to the EHM but did localize to the haustorial neck (Koh et al., 2005). In addition, a monoclonal antibody has been reported that recognizes a protein on the EHM surrounding a mature haustorium and not the plasma membrane (Roberts et al., 1993). The haustorial neck region might be considered equivalent to the arbuscule trunk, and while there are important structural differences between these two types of biotrophic interfaces, there are also some intriguing similarities. The fact that the protein domains of the EHM transition from the plasma membrane protein-containing neck region to the plasma membrane protein-excluding EHM region, which also contains a specific epitope, essentially parallels our description of trunk and branch domains of the periarbuscular membrane. It is tempting to speculate that the mechanism that guides the localization of plasma membrane proteins to the haustorial neck might be similar to that which guides the localization of AtPIP2a and MtBcp1 to the trunk domain of the periarbuscular membrane. Conversely, parallels may exist between mechanisms that control MtPT4 localization to the periarbuscular membranes and localization of proteins on the EHM; however, proteins that localize to the EHM have not yet been identified.

Our study has focused on membrane domains as defined by protein composition; however, the lipid composition of the periarbuscular membrane may also differ from that of the plasma membrane or in fact may differ between domains of the periarbuscular membrane. While isolation of periarbuscular membranes has not been reported, in the symbiosis between M. truncatula and Rhizobium bacteria, peribacteroid membranes surrounding symbiotic bacteria can be purified and their lipid and protein compositions have been analyzed. Such studies have shown that the peribacteroid membrane has a higher concentration of galactolipids than the plasma membrane (Gaude et al., 2004) and also a number of proteins involved in transport and secretion, including a syntaxin, MtSyp132, and a putative GPI-anchored protein, MtEnod16 (Catalano et al., 2004, 2007).

It is likely that the secretory system plays an important role in arbuscule development, as synthesis of the periarbuscular membrane requires significant deposition of membrane and newly synthesized proteins (Alexander et al., 1989; Bonfante and Perotto, 1995; Gianinazzi-Pearson, 1996; Harrison et al., 2002). This hypothesis is supported by the presence of organelles involved in synthesizing and secreting proteins, namely the nucleus, ER, and Golgi, residing in close proximity to the developing periarbuscular membrane, in addition to cytoskeletal components, actin, and microtubules necessary to direct secretion (Bonfante and Perotto, 1995; Gianinazzi-Pearson, 1996; Genre and Bonfante, 1997, 1998; Blancaflor et al., 2001). Here, these organelles were observed by live-cell imaging and are consistent with, but extend, the data available from earlier electron microscopy studies.

Accumulation of cytoplasm and repositioning of the nucleus prior to fungal penetration into cortical cells were observed, consistent with the recent proposal from Genre et al. (2008) that hyphae are directed into cortical cells by a preformed apparatus marked by a large accumulation of ER and cytoplasm. We sometimes observed the ER marker comprising a large accumulation surrounding young arbuscules, but at other times the ER appeared appressed to arbuscules and an accumulation of ER in advance of fungal growth was not apparent. The slight differences between our results and those of Genre et al. (2008) may be due to differences in experimental conditions or different fungal symbionts: our study used the AM fungus G. versiforme, while Genre et al. (2008) used Gigaspora gigantea. Because each cell was only imaged at one time, it is also possible that an ER aggregation formed and was subsequently filled by the fungus before imaging.

Golgi bodies may be one of the last steps in the secretion pathway before fusion of membrane vesicles to the periarbuscular membrane (Jurgens, 2004). With this in mind, we observed carefully the distribution of Golgi and noted that they reside adjacent to arbuscule branch nodes and are not associated with branch tips. This finding supports the idea that secretion is active around growing arbuscules.

In cells with degenerating arbuscules, some Golgi bodies remain associated with the fungus but a proportion of the population relocates to the periphery of the cell. However, there is a striking accumulation of peroxisomes around the collapsing structures. While the nature of arbuscule degradation has received little research attention, it is an interesting question. It would seem appropriate for the plant to metabolize the carbon resources invested in the arbuscule interface, and secretion of a new set of proteins may support degradation. The localization of peroxisomes surrounding collapsed arbuscules may even signal an active lipid breakdown process through β-oxidation; alternatively, they may ensure the sequestration of active oxygen species generated during membrane breakdown (Nyathi and Baker, 2006). Although the arbuscule dies, the plant cell remains alive and regains its former cellular structure. Protection against damaging radicals may be important to maintain cellular integrity. Overall, the distribution of organelles supports the idea of arbuscule degradation as an active cellular process.

By monitoring the localization of a tonoplast marker in cortical cells, we observed that a continuous tonoplast envelops the arbuscules at all stages of their development. While we did observe some bright spots of tonoplast fluorescence that may correspond to small vacuoles, these cells also appeared to have an intact, albeit highly convoluted, central vacuole. This interpretation is in contrast with the majority of the recent literature, which suggests that the large central vacuole fragments, creating multiple small vacuoles. Although the latter interpretation has become established in the literature, the authors of the early TEM micrographs (Toth and Miller, 1984) noted that the multiple small vacuole compartments visible in the single-plane images might represent individual vacuoles but, alternatively, could represent a single vacuolar system that followed the elaborate contours of the arbuscule. Our confocal microscopy data contribute a third dimension to the discussion and provide support for the existence of both vacuole fragments and a large continuous vacuole system in cells with arbuscules.

In summary, the fluorescent markers provided insights into membrane dynamics and membrane domains within the periarbuscular membrane and provide tools and a foundation for further studies of the biogenesis of this essential symbiotic interface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material, Transformation, and Growth Conditions

Experiments were performed using Medicago truncatula ‘Jemalong’, line A17. Organelle markers fused to mCherry were expressed in a stable transgenic A17 line, MtSCP1-GFP, described by Gomez et al. (2009). Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated root transformation was performed according to Boisson-Dernier et al. (2001). Briefly, M. truncatula seeds were surface sterilized and germinated for 24 h in the dark to promote hypocotyl growth. Root tips were excised and inoculated with A. rhizogenes strain ARquaI carrying appropriate plasmids. Inoculated seedlings were grown on modified Fahraeus medium supplemented with 25 mg L−1 kanamycin to select for transgenic roots for 20 d. Seedlings were then transplanted to sterile Turface, four to six seedlings per 11-inch pot for 10 d, followed by inoculation with 250 to 350 surface-sterilized Glomus versiforme spores per plant as described (Liu et al., 2007). Plants were grown in growth rooms under a 16-h-light (25°C)/8-h-dark (22°C) regime and fertilized once a week with half-strength Hoagland solution with full-strength nitrogen and 20 μM potassium phosphate. Plants were evaluated 3 to 5 weeks post inoculation with G. versiforme.

Plasmid Construction

pMtPT4:MtPT4-GFP was constructed by fusing the 3′ end of the MtPT4 cDNA in frame to the 5′ end of the S65T variant of GFP (Chiu et al., 1996). The complete MtPT4 coding sequence was amplified with 5′-AAGCTTGTCGACATGGGATTAGAAGTCCTTGAG-3′ and 5′-AAGCTTCCATGGCCTCAGTTCTTGAG-3′, digested with SalI and NcoI, and ligated into the CaMV35S-sGFP(S65T)-Nos vector (Chiu et al., 1996). The vector was subsequently digested with XbaI and KpnI to remove the 35S promoter, and an XbaI-KpnI MtPT4 promoter-MtPT4 gene fragment was ligated between the same sites. The XbaI-KpnI MtPT4 promoter-MtPT4 gene fragment was obtained by amplification with forward (5′-GTCGGATCCTCTAGACTCGATCCACAACAAAG-3′) and reverse (5′-AAGCTTCCATGGCCTCAGTTCTTGAG-3′) primers, followed by digestion with XbaI and KpnI. Finally, the complete MtPT4 promoter-MtPT4 coding sequence:GFP gene fusion was released by digestion with HindIII and EcoRI, and this fragment was ligated between the same sites of the binary vector pCAMBIA 3300.

pMtBcp1:GFP-MtBcp1 was constructed to produce an N-terminal GFP fusion to the mature MtBcp1 protein similar to Sun et al. (2004). This arrangement enables visualization of the full-length protein, which is anchored in the membrane through a GPI anchor located at the C-terminal end of the protein. A genomic DNA sequence corresponding to the previously described MtBcp1 promoter region (Hohnjec et al., 2005) and an open reading frame of the cleavable secretion signal was amplified with the primers 5′-CACATCTAGAGAGAGGGAGATGTGTT-3′ and 5′-TCTCGGATCCTGCAATTGCAACTGATGAAAG-3′, which add 5′ XbaI and 3′ BamHI restriction sites, digested, and ligated to the 5′ end of GFP in the vector CaMV35S-sGFP(S65T)-Nos (Chiu et al., 1996). The remainder of the MtBcp1 coding sequence including the TGA stop codon was amplified from genomic DNA with the primers 5′-GAGATGTACACTGATCACATTGTTGGTGATG-3′ and 5′-TCTCGCGGCCGCTCATGCAAAGATGACTGCA-3′, which add 5′ BsrGI and 3′ NotI restriction sites, and ligated in frame to the 3′ end of GFP in the same vector. This fusion including promoter, coding sequence with GFP, and NOS terminator was subcloned into the expression vector pCAMBIA 2301 (http://www.cambia.org) with the restriction enzymes XbaI and EcoRI.

Organelle vectors are as described (Nelson et al., 2007) and are available from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. Markers used in this study were expressed in pBIN vectors behind double 35S promoters with the coding sequence for mCherry fluorescent protein fused to AtPIP2a (plasma membrane), HDEL retention signal (ER), GmMAN1 (Golgi), PTS1 targeting signal (peroxisome), and γ-TIP (tonoplast).

Confocal Microscopy

Root segments showing fluorescence associated with fungal colonization (from MtPT4, MtBcp1, or MtSCP1 promoter) were excised and cut longitudinally along the vascular tissue. Samples were sealed between slide and coverslip using VALAP (1:1:1, Vaseline:lanolin:paraffin) to avoid desiccation (McGee-Russell and Allen, 1971). Cells below the section plane that had not been disrupted by cutting were imaged within 30 min of preparation, and cell viability in this system was observed over 3 h after sample preparation. Roots were imaged using a Leica TCS-SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) with a 63×, numerical aperture 1.2 water-immersion objective. GFP was excited with the blue argon ion laser (488 nm), and emitted fluorescence was collected from 505 to 545 nm; mCherry was excited with the Diode-Pumped Solid State laser at 561 nm, and emitted fluorescence was collected from 590 to 640 nm. Controls were performed to ensure no crossover between channels. Differential interference contrast images were collected simultaneously with the fluorescence using the transmitted light detector. Images were processed using Leica LAS-AF software (versions 1.6.3 and 1.7.0), Adobe Photoshop CS2 version 7 (Adobe Systems), and VOLOCITY (Improvision). For MtBcp1-GFP, MtPT4-GFP, and PIP2a-mCherry, data were collected from a minimum of 20 independently transformed root systems for each construct. For the organelle markers, data were obtained from a minimum of five independently transformed root systems for each construct. In all cases, the interpretations are drawn from considering the whole data sets. The figures included in this article are representative images.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Localization of MtPT4-GFP.

Supplemental Figure S2. Localization of GFP-MtBcp1.

Supplemental Figure S3. Localization of MtSCP1:GFP.

Supplemental Figure S4. Localization of AtPIP2a-mCherry plasma membrane marker.

Supplemental Figure S5. Localization of mCherry-HDEL ER marker.

Supplemental Figure S6. Localization of GmMan1-mCherry Golgi marker.

Supplemental Figure S7. Localization of mCherry-PTS1 peroxisome marker.

Supplemental Figure S8. Localization of γ-TIP-mCherry tonoplast marker.

Supplemental Figure S9. MtSCP1:GFP expression 3 h after sample preparation.

Supplemental Movie S1. M. truncatula root cortical cells colonized with G. versiforme remain viable at least 3 h after sample preparation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary R. Dewbre for assistance with generation of the MtPT4-GFP fusion construct and members of the Harrison laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (grant nos. IBN–0343975 and DBI–0618969) and the Atlantic Philanthropies, Molecular and Chemical Ecology Initiative.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Maria J. Harrison (mjh78@cornell.edu).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Alexander T, Toth R, Meier R, Weber HC (1989) Dynamics of arbuscule development and degeneration in onion, bean and tomato with reference to vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae in grasses. Can J Bot 67: 2505–2513 [Google Scholar]

- Balestrini R, Berta G, Bonfante P (1992) The plant nucleus in mycorrhizal roots: positional and structural modifications. Biol Cell 75: 235–243 [Google Scholar]

- Blancaflor EB, Zhao LM, Harrison MJ (2001) Microtubule organization in root cells of Medicago truncatula during development of an arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis with Glomus versiforme. Protoplasma 217: 154–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisson-Dernier A, Chabaud M, Garcia F, Becard G, Rosenberg C, Barker DG (2001) Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed roots of Medicago truncatula for the study of nitrogen-fixing and endomycorrhizal symbiotic associations. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14: 695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfante P, Genre A (2008) Plants and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: an evolutionary-developmental perspective. Trends Plant Sci 13: 492–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfante P, Perotto S (1995) Strategies of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi when infecting host plants. New Phytol 130: 3–21 [Google Scholar]

- Bonfante-Fasolo P (1984) Anatomy and morphology of VA mycorrhizae. In CL Powell, DJ Bagyaraj, eds, VA Mycorrhizae. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 5–33

- Brown DA, Crise B, Rose JK (1989) Mechanism of membrane anchoring affects polarized expression of 2 proteins in Mdck cells. Science 245: 1499–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MF, King EJ (1991) Morphology and histology of vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizae. In NC Schenk, ed, Methods and Principles of Mycorrhizal Research. APS Press, St. Paul, pp 15–21

- Bucher M (2007) Functional biology of plant phosphate uptake at root and mycorrhiza interfaces. New Phytol 173: 11–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano CM, Czymmek KJ, Gann JG, Sherrier DJ (2007) Medicago truncatula syntaxin SYP132 defines the symbiosome membrane and infection droplet membrane in root nodules. Planta 225: 541–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano CM, Lane WS, Sherrier DJ (2004) Biochemical characterization of symbiosome membrane proteins from Medicago truncatula root nodules. Electrophoresis 25: 519–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu W, Niwa Y, Zeng W, Hirano T, Kobayashi H, Sheen J (1996) Engineered GFP as a vital reporter in plants. Curr Biol 6: 325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox G, Sanders F (1974) Ultrastructure of the host-fungus interface in a vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza. New Phytol 73: 901–912 [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhaber B, Wildpaner M, Schultz CJ, Borner GHH, Dupree P, Eisenhaber F (2003) Glycosylphosphatidylinositol lipid anchoring of plant proteins: sensitive prediction from sequence- and genome-wide studies for Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol 133: 1691–1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fester T, Strack D, Hause B (2001) Reorganization of tobacco root plastids during arbuscule development. Planta 213: 864–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier J, Timmers AC, Sieberer BJ, Jauneau A, Chabaud M, Barker DG (2008) Mechanism of infection thread elongation in root hairs of Medicago truncatula and dynamic interplay with associated rhizobial colonization. Plant Physiol 148: 1985–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaude N, Tippmann H, Flemetakis E, Katinakis P, Udvardi M, Dormann P (2004) The galactolipid digalactosyldiacylglycerol accumulates in the peribacteroid membrane of nitrogen-fixing nodules of soybean and Lotus. J Biol Chem 279: 34624–34630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genre A, Bonfante P (1997) A mycorrhizal fungus changes microtubule orientation in tobacco root cells. Protoplasma 199: 30–38 [Google Scholar]

- Genre A, Bonfante P (1998) Actin versus tubulin configuration in arbuscule-containing cells from mycorrhizal tobacco roots. New Phytol 140: 745–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genre A, Chabaud M, Faccio A, Barker DG, Bonfante P (2008) Prepenetration apparatus assembly precedes and predicts the colonization patterns of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi within the root cortex of both Medicago truncatula and Daucus carota. Plant Cell 20: 1407–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genre A, Chabaud M, Timmers T, Bonfante P, Barker DG (2005) Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi elicit a novel intracellular apparatus in Medicago truncatula root epidermal cells before infection. Plant Cell 17: 3489–3499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianinazzi-Pearson V (1996) Plant cell responses to arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi: getting to the roots of the symbiosis. Plant Cell 8: 1871–1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianinazzi-Pearson V, Arnould C, Oufattole M, Arango M, Gianinazzi S (2000) Differential activation of H+-ATPase genes by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in root cells of transgenic tobacco. Planta 211: 609–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianinazzi-Pearson V, Smith SE, Gianinazzi S, Smith FA (1991) Enzymatic studies on the metabolism of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas. New Phytol 117: 61–74 [Google Scholar]

- Gillmor CS, Lukowitz W, Brininstool G, Sedbrook JC, Hamann T, Poindexter P, Somerville C (2005) Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins are required for cell wall synthesis and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 1128–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassop D, Smith SE, Smith FW (2005) Cereal phosphate transporters associated with the mycorrhizal pathway of phosphate uptake into roots. Planta 222: 688–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez SK, Javot H, Deewatthanawong P, Torres-Jerez I, Tang YH, Blancaflor EB, Udvardi MK, Harrison MJ (2009) Medicago truncatula and Glomus intraradices gene expression in cortical cells harboring arbuscules in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. BMC Plant Biol 9: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MJ (1999) Molecular and cellular aspects of the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50: 361–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MJ (2005) Signaling in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Annu Rev Microbiol 59: 19–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MJ, Dewbre GR, Liu J (2002) A phosphate transporter from Medicago truncatula involved in the acquisition of phosphate released by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Cell 14: 2413–2429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohnjec N, Vieweg MF, Pühler A, Becker A, Küster H (2005) Overlaps in the transcriptional profiles of Medicago truncatula roots inoculated with two different Glomus fungi provide insights into the genetic program activated during arbuscular mycorrhiza. Plant Physiol 137: 1283–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javot H, Penmetsa RV, Terzaghi N, Cook DR, Harrison MJ (2007) A Medicago truncatula phosphate transporter indispensable for the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 1720–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens G (2004) Membrane trafficking in plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20: 481–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine-Vehn J, Leitner J, Zwiewka M, Sauer M, Abas L, Luschnig C, Friml J (2008) Differential degradation of PIN2 auxin efflux carrier by retromer-dependent vacuolar targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 17812–17817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh S, Andre A, Edwards H, Ehrhardt D, Somerville S (2005) Arabidopsis thaliana subcellular responses to compatible Erysiphe cichoracearum infections. Plant J 44: 516–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajinski F, Hause B, Gianinazzi-Pearson V, Franken P (2002) Mtha1, a plasma membrane H+-ATPase gene from Medicago truncatula, shows arbuscule-specific induced expression in mycorrhizal tissue. Plant Biol 4: 754–761 [Google Scholar]

- Lalanne E, Honys D, Johnson A, Borner GHH, Lilley KS, Dupree P, Grossniklaus U, Twell D (2004) SETH1 and SETH2, two components of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthetic pathway, are required for pollen germination and tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 229–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisanti MP, Caras IW, Davitz MA, Rodriguezboulan E (1989) A glycophospholipid membrane anchor acts as an apical targeting signal in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 109: 2145–2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Blaylock L, Endre G, Cho J, Town CD, VandenBosch K, Harrison MJ (2003) Transcript profiling coupled with spatial expression analyses reveals genes involved in distinct developmental stages of the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Cell 15: 2106–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Maldonado-Mendoza IE, Lopez-Meyer M, Cheung F, Town CD, Harrison MJ (2007) The arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis is accompanied by local and systemic alterations in gene expression and an increase in disease resistance in the shoots. Plant J 50: 529–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse S, Schliemann W, Ammer C, Kopka J, Strack D, Fester T (2005) Organization and metabolism of plastids and mitochondria in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots of Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol 139: 329–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee-Russell S, Allen R (1971) Reversible stabilization of labile microtubules in the reticulopodial network of Allogromia. Adv Cell Mol Biol 1: 153–184 [Google Scholar]

- Nagy F, Karandashov V, Chague W, Kalinkevich K, Tamasloukht M, Xu GH, Jakobsen I, Levy AA, Amrhein N, Bucher M (2005) The characterization of novel mycorrhiza-specific phosphate transporters from Lycopersicon esculentum and Solanum tuberosum uncovers functional redundancy in symbiotic phosphate transport in solanaceous species. Plant J 42: 236–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebenfuhr A, Gallagher LA, Dunahay TG, Frohlick JA, Mazurkiewicz AM, Meehl JB, Staehelin LA (1999) Stop-and-go movements of plant Golgi stacks are mediated by the acto-myosin system. Plant Physiol 121: 1127–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenfuhr A (2007) A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J 51: 1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyathi Y, Baker A (2006) Plant peroxisomes as a source of signalling molecules. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763: 1478–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell RJ, Panstruga R (2006) Tete a tete inside a plant cell: establishing compatibility between plants and biotrophic fungi and oomycetes. New Phytol 171: 699–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parniske M (2008) Arbuscular mycorrhiza: the mother of plant root endosymbioses. Nat Rev Microbiol 6: 763–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszkowski U, Kroken S, Roux C, Briggs SP (2002) Rice phosphate transporters include an evolutionarily divergent gene specifically activated in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 13324–13329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redeker D, Kodner R, Graham L (2000) Glomalean fungi from the Ordovician. Science 289: 1920–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remy W, Taylor T, Hass H, Kerp H (1994) Four hundred-million-year-old vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 11841–11843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AM, Mackie AJ, Hathaway V, Callow JA, Green JR (1993) Molecular differentiation in the extrahaustorial membrane of pea powdery mildew haustoria at early and late stages of development. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 43: 147–160 [Google Scholar]

- Roudier F, Fernandez AG, Fujita M, Himmelspach R, Borner GHH, Schindelman G, Song S, Baskin TI, Dupree P, Wasteneys GO, Benfey PN (2005) COBRA, an Arabidopsis extracellular glycosyl-phosphatidyl inositol-anchored protein, specifically controls highly anisotropic expansion through its involvement in cellulose microfibril orientation. Plant Cell 17: 1749–1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannerini S, Bonfante-Fasolo P (1982) Comparative ultrastructural analysis of mycorrhizal associations. Can J Bot 61: 917–943 [Google Scholar]

- Schindelman G, Morikami A, Jung J, Baskin TI, Carpita NC, Derbyshire P, McCann MC, Benfey PN (2001) COBRA encodes a putative GPI-anchored protein, which is polarly localized and necessary for oriented cell expansion in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 15: 1115–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SE, Read DJ (2008) Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Academic Press, San Diego

- Smith SE, Smith FA, Jakobsen I (2003) Mycorrhizal fungi can dominate phosphate supply to plants irrespective of growth responses. Plant Physiol 133: 16–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun WX, Zhao ZD, Hare MC, Kieliszewski MJ, Showalter AM (2004) Tomato LeAGP-1 is a plasma membrane-bound, glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored arabinogalactan protein. Physiol Plant 120: 319–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Shimada T, Ono E, Tanaka Y, Nagatani A, Higashi S, Watanabe M, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I (2003) Why green fluorescent fusion proteins have not been observed in the vacuoles of higher plants. Plant J 35: 545–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth R, Miller RM (1984) Dynamics of arbuscule development and degeneration in a Zea mays mycorrhiza. Am J Bot 71: 449–460 [Google Scholar]

- Valot B, Negroni L, Zivy M, Gianinazzi S, Dumas-Gaudot E (2006) A mass spectrometric approach to identify arbuscular mycorrhiza-related proteins in root plasma membrane fractions. Proteomics 6: 145–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.