Abstract

Phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosyltransferase A (PimA) is an essential glycosyltransferase (GT) involved in the biosynthesis of phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides (PIMs), which are key components of the mycobacterial cell envelope. PimA is the paradigm of a large family of peripheral membrane-binding GTs for which the molecular mechanism of substrate/membrane recognition and catalysis is still unknown. Strong evidence is provided showing that PimA undergoes significant conformational changes upon substrate binding. Specifically, the binding of the donor GDP-Man triggered an important interdomain rearrangement that stabilized the enzyme and generated the binding site for the acceptor substrate, phosphatidyl-myo-inositol (PI). The interaction of PimA with the β-phosphate of GDP-Man was essential for this conformational change to occur. In contrast, binding of PI had the opposite effect, inducing the formation of a more relaxed complex with PimA. Interestingly, GDP-Man stabilized and PI destabilized PimA by a similar enthalpic amount, suggesting that they formed or disrupted an equivalent number of interactions within the PimA complexes. Furthermore, molecular docking and site-directed mutagenesis experiments provided novel insights into the architecture of the myo-inositol 1-phosphate binding site and the involvement of an essential amphiphatic α-helix in membrane binding. Altogether, our experimental data support a model wherein the flexibility and conformational transitions confer the adaptability of PimA to the donor and acceptor substrates, which seems to be of importance during catalysis. The proposed mechanism has implications for the comprehension of the peripheral membrane-binding GTs at the molecular level.

Glycans are not only one of the major components of the cell but also are essential molecules that modulate a variety of important biological processes in all living organisms. Glycans are used primarily as energy storage and metabolic intermediates as well as being main structural constituents in bacteria and plants. Moreover, as a consequence of protein and lipid glycosylation, glycans generate a significant amount of structural diversity in biological systems. This structural information is particularly apparent in molecular recognition events including cell-cell interactions during critical steps of development, the immune response, host-pathogen interactions, and tumor cell metastasis. Most of the enzymes encoded in eukaryotic/prokaryotic/archaeans genomes that are responsible for the biosynthesis and modification of glycan structures are GTs3 (1). Here we have focused in the phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosyltransferase A (PimA), an essential enzyme of mycobacterial growth that initiates the biosynthetic pathway of key structural elements and virulence factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides (PIM) lipomannan and lipoarabinomannan (2–5). This amphitropic enzyme catalyzes the transfer of a Manp residue from GDP-Man to the 2-position of PI to form phosphatidyl-myo-inositol monomannoside (PIM1) on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane (2) (Fig. 1).

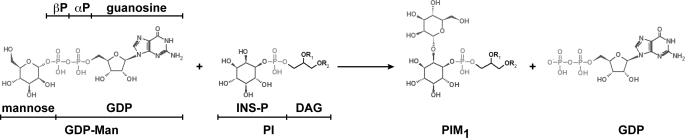

FIGURE 1.

PIM1 biosynthesis in mycobacteria. PimA transfers a Manp residue from GDP-Man to the 2-position of the myo-inositol ring of PI to form PIM1 (where DAG is di-acyl-glycerol, and INS-P is 1-l-myo-inositol phosphate). The reaction occurs with retention of the anomeric configuration of the sugar donor.

Although considerable progress has been made in recent years in understanding the mode of action of GTs at the molecular level, the mechanisms that govern recognition of lipid acceptors and membrane association of peripheral membrane-binding GTs remains poorly understood. GTs can be classified as either “inverting” or “retaining” enzymes according to the anomeric configuration of the reaction substrates and products. A single displacement mechanism in which a general base assists in the activation of the acceptor substrate for nucleophilic attack by the sugar donor is well established for inverting enzymes (6, 7). In contrast, the catalytic mechanism for retaining enzymes, including PimA, remains unclear. By analogy with glycosylhydrolases, a double displacement mechanism via the formation of a covalent glycosyl-enzyme intermediate was first proposed (8). However, in the absence of direct evidence of a viable covalent intermediate, an alternative mechanism known as the SNi “internal return” has been suggested where phospho-sugar donor bond breakage and sugar-acceptor bond formation occur in a concerted, but necessarily stepwise manner on the same face of the sugar (6, 9). Only two protein topologies have been found for nucleotide-diphospho-sugar-dependent enzymes among the first 30 GT sequence-based families (10) (see the carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZy) data base) for which three-dimensional structures have been reported (11). These topologies are variations of “Rossmann-like” domains and have been defined as GT-A (12) and GT-B (13). Both inverting and retaining enzymes were found in GT-A and GT-B folds, indicating that there is no correlation between the overall fold of GTs and their catalytic mechanism. The primary sequence of PimA contains the GPGTF (glycogen phosphorylase/GT) motif, a signature present in enzymes of the GT-B fold (14). GT-B proteins do not use divalent cations and consist of two Rossmann-like (β-α-β) domains separated by a deep fissure. Therefore, an important interdomain movement has been predicted in some members of this superfamily during catalysis, including MurG (15), glycogen synthase (16),and the myo-inositol 1-phosphate N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase MshA (17).

To perform their biochemical functions, membrane-binding GTs interact with membranes by two different mechanisms. Whereas integral membrane GTs are permanently attached through transmembrane regions (e.g. hydrophobic α-helices) (18) peripheral membrane-binding GTs temporarily bind membranes by (i) a stretch of hydrophobic residues exposed to bulk solvent, (ii) electropositive surface patches that interact with acidic phospholipids (e.g. amphipathic α-helices), and/or (iii) protein-protein interactions (19–22). A close interaction of the enzyme with membranes might be a strict requirement for PI modification by PimA. We recently solved the crystal structure of PimA from Mycobacterium smegmatis (MsPimA) in complex with the donor substrate GDP-Man (23, 24). The notion of a membrane-associated protein via electrostatic interactions is consistent with the finding of an amphipathic α-helix and surface-exposed hydrophobic residues in the N-terminal domain of MsPimA. Despite the fact that sugar transfer is catalyzed between the mannosyl group of the GDP-Man donor and the myo-inositol ring of PI, the enzyme displays an absolute requirement for both fatty acid chains of PI in order for the transfer reaction to take place. Furthermore, PimA was able to bind monodisperse PI, but its transferase activity was stimulated by high concentrations of nonsubstrate anionic surfactants, indicating that the reaction requires a lipid-water interface. We thus proposed a model of interfacial catalysis in which PimA recognizes the fully acylated substrate PI with its polar head within the catalytic cleft and the fatty acid moieties only partially sequestered from the bulk solvent (24).

This study describes a detailed investigation of the lipid acceptor binding site and the conformational properties of PimA in solution. Using a combination of limited proteolysis, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), circular dichroism (CD), analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) and site-directed mutagenesis, we propose a plausible model for substrates recognition and binding. The implications of this model for the comprehension of the early steps of PIM biosynthesis and the catalytic mechanism of other members of the peripheral membrane-binding GT family are discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Methods

The pimA gene from M. smegmatis (MSMEG_ 2935, Rv2610c, genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList/) was subcloned from pQE70-MspimA DNA by standard PCR using oligonucleotide primers pimA_NdeI_Fwd (5′-GGGAATTCCATATGCGTATCGGGATGGTCTGCC-3′) and pimA_ BamHI_Rev (5′-CGCGGATCCTCAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATG-3′) with Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). The PCR fragment was digested with NdeI and BamHI and ligated to the expression vector pET29a (Novagen) generating pET29a-MspimA. The recombinant MsPimA (378 residues) has an additional peptide of 8 amino acids (379RSHHHHHH386) at the C terminus that includes a histidine tag. MsPimA and MsPimA mutants were purified to apparent homogeneity by a combination of metal ion affinity, anionic exchange, and gel filtration chromatography steps as described previously (23). The enzymatic activity of MsPimA and MsPimA mutants was monitored using a radiometric assay. Briefly, the reaction mixture contained 0.0625 μCi of GDP-[C14]Man (specific activity, 305 mCi mmol−1; Amersham Biosciences), membrane preparations from M. smegmatis mc2155 (0.5 mg of proteins) as the source of lipid acceptors, 50 μg of purified MsPimA or MsPimA mutants, and 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, in a final volume of 250 μl. Reactions were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C and stopped with 1.5 ml of CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1 (v/v)). The PIM-containing organic phase was prepared and analyzed by TLC as described by Korduláková et al. (2). The bands recorded by a PhosphorImager Typhoon TRIO (GE Healthcare) were quantified using volume integration with the ImageQuant TL v2005 program (GE Healthcare).

Gel Filtration

Gel filtration chromatography was performed using a BioSuite 250 5-μm HR SEC column (Waters Corp.) equilibrated in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, and 150 mm NaCl at 1 ml min−1. The column was previously calibrated using gel filtration standards (Sigma) including β-amylase (200 kDa), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), and cytochrome c (12.4 kDa).

Limited Proteolysis of MsPimA

Recombinant purified MsPimA (25 μg) was incubated with 0.05 μg of elastase (Sigma) in 100 μl of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, in the presence of 1 mm guanosine, 1 mm GDP (Sigma), 1 mm GDP-Man (Sigma), or 1.25 mm PI (Sigma) for 0–90 min at 37 °C. Aliquots of 12 μl were mixed with 3 μl of 250 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 50% glycerol, 500 mm dithiothreitol, and 0.01% bromphenol blue at the indicated times. Samples were boiled for 3 min and run onto an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Protein bands were visualized by staining the gel with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250.

N-terminal Sequence Analyses

Proteolytic fragments were electrotransferred to Hybond-P polyvinylidene difluoride (Amersham Biosciences) in 50 mm Trizma base and 50 mm boric acid buffer for 16 h at room temperature. Bands were stained with 0.1% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 and subjected to N-terminal sequence analysis using an AABI494 protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Ligand binding to MsPimA was assayed using the high precision VP-ITC system (MicroCal Inc.) as described previously (24, 25) with the following modifications. The ITC cell (1.4 ml) contained 10 μm MsPimA in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 5% Me2SO, and the syringe (300 μl) contained 150 μm GDP-Man, 150 μm GDP, or 250 μm guanosine in the same buffer. Binding of PI aggregates to MsPimA-GDP and mutant MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E-GDP complexes was assayed as follows. The protein was first titrated with GDP, and at the end of the titration, the solution containing the protein complex was kept in the ITC cell and titrated with 1.25 mm solution of PI in the same buffer preparation. Sample solutions were thoroughly degassed under vacuum, and each titration was performed at 25 °C by one injection of 2 μl followed by 29 injections of 10 μl, with 210 s between injections, using a 290 rpm rotating syringe. Raw heat signal collected with a 16-s filter was corrected for the dilution heat of the ligand in the MsPimA buffer and normalized to the concentration of ligand injected. Data were fit to a bimolecular model (26) using the OriginTM software provided by the manufacturer.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Thermal unfolding of MsPimA and of the MsPimA complexes was quantified by DSC using the high precision VP-DSC system (MicroCal Inc.) as described previously (27). Sample solutions contained 9.5 μm MsPimA alone or mixed with one of the following ligands at a saturating concentration determined by ITC: GDP-Man, 50 μm; GDP, 30 μm; PI, 150 μm (24); or guanosine, 250 μm (this study). One protein sample contained both GDP and PI added in this order at the same concentrations as above. Protein and ligands were dissolved in the same buffer preparation (50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 0.2% Me2SO) and degassed under vacuum for 10 min with gentle stirring prior to being loaded into the calorimetric cell (0.5 ml). Sample solutions were held in situ under a constant external pressure of 25 p.s.i., equilibrated for 30 min at 25 °C, and then heated at a constant rate of 1 °C min−1. Experimental heat capacity functions were collected with a 16-s filter. Data normalization and quantification were carried out with the Origin7 software (28) provided by the manufacturer. The partial molar heat capacity (Cp) was derived from the experimental heat capacity by subtraction of the instrumental base line. The partial molar excess heat capacity (Cp,ex) was derived from the Cp function by subtraction of the molar intrinsic heat capacity (Cp,int). Cp,int was calculated as an interpolation over the transition region of the folded and unfolded states weighted in proportion to their relative contributions. For free MsPimA, the partial molar heat capacity of the native state was obtained by linear extrapolation of the pre-transition base line. The partial molar heat capacity of the unfolded state was calculated by summing up the heat capacities of the amino acid residues constituting the polypeptide chain using the known quadratic dependence of Cp of the unfolded state with temperature (29, 30) (cf. Fig. 3A, inset). Fitting and deconvolution of Cp,ex required the use of a non-two-state transition model.

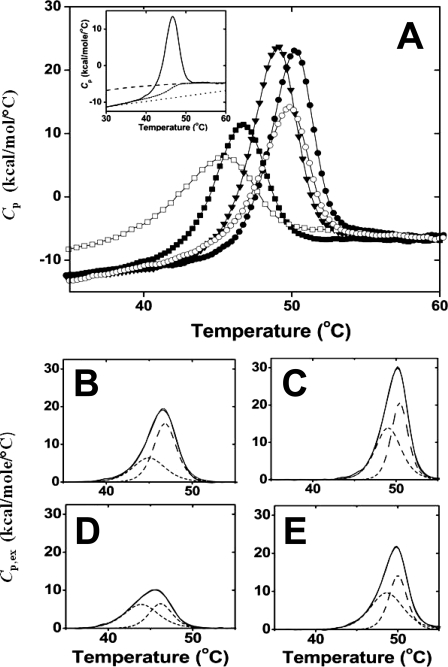

FIGURE 3.

Calorimetric study of the temperature-induced unfolding of MsPimA and of MsPimA-substrate complexes. A, temperature dependence of the partial molar heat capacity (Cp) of MsPimA (■) and MsPimA complexes with PI (□), GDP-Man (▾), GDP (●), and GDP and PI (○). Inset, the intrinsic molar heat capacity (Cp,int) of MsPimA (■) connecting the Cp function of the native state (····) and the calculated Cp function of the unfolded state (-----). B–D, deconvolution of the molar excess heat capacity (Cp,ex) of MsPimA (B) and MsPimA complexes with GDP (C), PI (D), and GDP and PI (E) using a non-two-state model. The experimental (—) and calculated (– – –) Cp,ex functions of free and bound MsPimA are shown together with the Cp,ex functions of the low temperature (-----) and high temperature (– – –) unfolding transitions.

Calculation of MsPimA Intrinsic Unfolding Enthalpy

On free MsPimA unfolding, the observed unfolding enthalpy (ΔHu) measured as the surface under the heat absorption peak (Cp,ex) of the DSC endotherm is the intrinsic unfolding enthalpy of the protein (ΔHu (free) = ΔHu,int (free)). On unfolding of a MsPImA-substrate complex, the observed unfolding enthalpy equals the intrinsic unfolding enthalpy of the protein inside the protein complex minus the substrate binding enthalpy,

The change in ΔHu,int from the free to the bound state of MsPimA then equals

Values of ΔHbind for the binding of GDP-Man and GDP to free MsPimA were measured by ITC (Fig. 2D). Values of ΔHbind for the binding of PI to free MsPimA (ΔHbind = −1.3 kcal/mol) and to the MsPimA-GDP complex (ΔHbind = 13.6 kcal mol−1) were taken from Guerin et al. (24). From repeated experiments, the value of ΔHbind is ±0.2 kcal/mol.

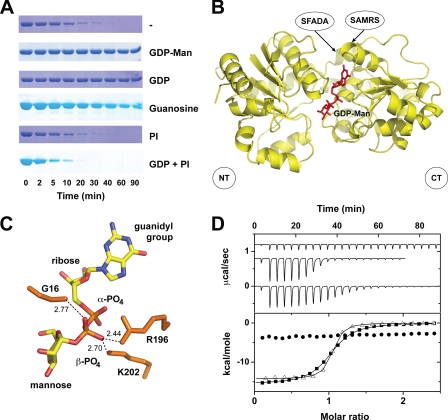

FIGURE 2.

Substrate-induced conformational changes in MsPimA. A, elastase cleavage of MsPimA preincubated with different ligands. B, surface representation of MsPimA three-dimensional structure in a closed conformation. The GDP-Man is buried at the N- (NT) and C-terminal (CT) domains interface. The N-terminal residues of selected proteolytic fragments are indicated. C, MsPimA residues Gly16 (N-terminal) and Arg196/Lys202 (C-terminal) involved in the β-PO4 stacking interaction. D, ITC measurements of MsPimA-ligand interactions. The upper panel shows the raw heat signal of the titration of MsPimA with GDP-Man (■), GDP (▵), and guanosine (●). The lower panel shows the integrated heats of injections of the above titrations corrected for the ligand heat of dilution and normalized to the ligand concentration. Solid lines correspond to the best fit of data using a bimolecular interaction model. GDP-Man and GDP bind to MsPimA with a 1:1 stoichiometry, dissociation constants (Kd) of 0.23 and 0.04 μm, and heats of binding (ΔHbind) of −15.6 kcal mol−1 and −14.2 kcal mol−1, respectively. Guanosine binds with a weak binding affinity generating a linear variation of ΔHbind with guanosine concentration, Ka ≤ 104 m−1 and −ΔHbind ≤ 4 kcal mol−1.

Circular Dichroism

MsPimA thermal unfolding was determined by recording the ellipticity change at 222 nm as a function of the temperature. An Aviv 215 spectropolarimeter was used. The protein sample at 10 μm in 10 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, with or without ligand(s), was placed in a rectangular fused silica cuvette of 0.2-cm path length. The cuvette was inserted in the cell holder with a Peltier temperature control. The sample was heated with a slope of 1 °C min−1, and ellipticity was recorded each 0.5 °C after an equilibration time of 15 s. The CD signal was averaged over 10 s. Each set of data collected was then converted to Δq/ΔT using the first derivative converter available in the software of the CD instrument with a window of 11 data points and a second degree polynomial smoothing. The observed difference in T½ between the CD and DSC melting curves was shown to result from the difference in the phosphate buffer concentration (data not shown).

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

AUC experiments were performed with a Beckman XL-1 analytical ultracentrifuge using absorbance optics. Velocity measurements utilized a two-sector charcoal-filled Epon centerpieces, quartz windows, 400-μl sample, and 420-μl reference (buffer: 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl) volumes. All samples were centrifuged in a Beckman 8-hole An50Ti rotor at 22 °C at 40,000 rpm, and the data were collected at 280 nm with a radial increment of 0.003 cm for ∼6 h. Velocity data were edited and analyzed using the boundary analysis method of Demeler and van Holde as implemented in Ultrascan, version 7.3 for Windows (31, 32). Sedimentation coefficients (s) are reported in Svedberg units (S), where 1 S = 1 × 10−13 s, and were corrected to that of water at 20 °C (s20,w). The partial specific volume of full-length MsPimA was calculated from the amino acid sequence within Ultrascan. Modeling of hydrodynamic parameters was performed using Ultrascan. The frictional ratio (f/f0) was calculated from the known molecular mass and the measured sedimentation coefficient using Ultrascan.

Structural Alignment

Structural alignments of MsPimA (PDB code 1GEJ) with CgMshA (PDB code 3C4V), WaaG (PDB code 2IV7), WaaF (PDB code 1PSW), WaaC (PDB code 2H1F), MurG (PDB code 1NLM) and GumK (PDB code 3CV3) were performed by the distance alignment matrix method using DALI Lite (33). The images were generated with PyMOL, version 0.99 (34).

Molecular Docking Calculations

We used the program ICM, version 3.6 (35), to dock Ins-P to the structure of the MsPimA-GDP-Man complex (PDB code 2GEJ). Interaction grids were calculated in the acceptor binding site after the preliminary selection of key residues chosen within 6 Å of the reactive axial oxygen of the mannose moiety. Ins-P and GDP-Man input files were extracted from the PubChem data base (pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Both structures were protonated and optimized, and all water molecules were removed from the receptor using standard ICM protocols. The thoroughness parameter was set to a value of 2 to increase the Monte Carlo steps and ensure a greatest exploration. The best solution showed a predicted energy below 60 kcal m−1 and was used for structural analysis.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

M. smegmatis pimA was subcloned in the pET29a expression vector (Novagen) using the NdeI and BamHI restriction sites, allowing for the production of a C-terminal His6-tagged fusion protein. The mutants MsPimAQ18A, MsPimAY62A, MsPimAN63A, MsPimAS65A, MsPimAR68A, MsPimAR70A, MsPimAN97A, MsPimAT119A, MsPimAK123A, MsPimAR196A, MsPimAE199A, and MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E were generated by the two-step PCR overlap method using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) and pET29a-MspimA as the DNA template. The flanking oligonucleotides that annealed with the NdeI and BamHI sites were pimA_NdeI_Fwd and pimA_BamHI_Rev, respectively. The overlapping oligonucleotides for each mutant are described in supplemental Table 1S. The 1100-bp fragments obtained were digested with NdeI/BamHI and ligated to pET29a treated with the same enzymes. All plasmids were sequenced at the Proteomics and Metabolomics Facility at Colorado State University.

Functionality of MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E Mutant in M. smegmatis

A two-step homologous recombination procedure was used earlier to provide evidence of the essentiality of pimA in M. smegmatis (2). In the course of this experiment, strains having undergone a single crossover at the pimA locus were easily isolated, but it was shown that a second crossover leading to gene knock-out was achievable only in the presence of a rescue wild-type copy of pimA carried by a replicative plasmid. To determine whether the MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E mutant encoded an active enzyme in mycobacteria, a mycobacteria/Escherichia coli shuttle plasmid (pVV16) expressing this gene was tested for its ability to serve as a rescue plasmid in the gene knock-out experiment. A pVV16 construct carrying a wild-type copy of the pimA gene from M. smegmatis was used as a positive control, and the empty pVV16 plasmid served as the negative control in this experiment (2).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Conformational Flexibility Studies Using Limited Proteolysis

To study the effect of substrate binding on the conformation of PimA, we first determined the oligomeric state of MsPimA in solution by subjecting the purified protein to size exclusion chromatography (supplemental Fig. 1S). Results showed that MsPimA is a monomer with no sign of higher order oligomers in the purified preparation. The monomeric state of the full-length protein was independent of the presence of substrates (data not shown).

Limited proteolysis has proven to be a powerful technique to study ligand-induced conformational changes in proteins (36). In the case of MsPimA, a monomeric globular protein, the reaction is expected to occur primarily at flexible exposed loops. However, the presence of ligands can have considerably effect on the susceptibility of the protein to the protease. When incubated with elastase, MsPimA was rapidly degraded (Fig. 2A). Microsequencing of the two predominant small species of 23 and 15 kDa revealed the sequences SAMRS, located in α9 (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. 2S) and SFADA, in the connecting loop β7-β8 at the junction between N- and C-terminal domains (Fig. 2B). It is worth noting that helix α9 contains two critical residues involved in donor substrate recognition: Asp253, which interacts with N2 of the guanidyl group of GDP-Man, conferring MsPimA its specificity for the nucleoside; and Lys256, which participates in ribose binding. Similar proteolysis experiments performed in the presence of GDP or GDP-Man suggest, in contrast, a conformational rearrangement, as MsPimA was protected from the action of elastase even after 90 min incubation (Fig. 2A). The crystal structure of the MsPimA-GDP-Man complex revealed that the enzyme crystallizes in a “closed” conformation with its active site located in a deep cleft formed between the N- and C-terminal domains (Ref. 24, Fig. 2B). The GDP-Man binding site resides mainly in the C-terminal domain, where it makes a number of hydrogen bonds with the protein. However, two residues of the N-terminal domain were found to interact with GDP-Man: Pro14, in the connecting loop β1-α1 stabilizing the guanine heterocycle by a van der Waals stacking interaction; and Gly16, at the beginning of α1, establishing a hydrogen bond with the β-PO4 of GDP (Fig. 2C). Gly16 is located in the Gly-Gly loop, a conserved nucleoside-diphospho-sugar binding motif that has been found to be essential for enzymatic activity in other GT-B enzymes (37). Interestingly, two other residues, Arg196 and Lys202, located in the C-terminal domain, also make electrostatic interactions with the β-PO4, thereby restricting its position in the active site of MsPimA (Fig. 2C). It is worth mentioning that the α-PO4 of GDP-Man does not interact with any particular residue from the enzyme (24). To determine the relevance of the β-PO4 in the stabilization of the closed conformation, MsPimA was incubated with elastase in the presence of guanosine, in which the α-PO4 and β-PO4 of GDP are missing. As shown in Fig. 2A, guanosine only partially protected MsPimA from degradation by the protease. Moreover, ITC measurements revealed that GDP-Man and GDP bind to MsPimA with high association constants and favorable binding enthalpies (Fig. 2D, Ref. 24). In contrast, guanosine binds to MsPimA with a binding constant ∼103-fold smaller than that of GDP and with a ∼3-fold reduced binding enthalpy (Fig. 2D). This observation was confirmed by the small differences in the unfolding parameters of the protein in a guanosine-saturated solution as measured by DSC (supplemental Fig. 3S). These results clearly demonstrate that the interactions between MsPimA and the β-PO4 of GDP-Man are essential for generating a closed state, which is a critical event for maintaining a functional active site.

The effect of PI binding to MsPimA and the MsPimA-GDP complex was analyzed by proteolysis experiments. Surprisingly, in both cases, MsPimA became highly sensitive to elastase, indicating that PI triggers a yet significant conformational change that modifies the closed GDP-Man-induced conformation (Fig. 2A).

Unfolding Thermodynamics of Free and Substrate-bound MsPimA

To further characterize the effect of substrate binding on MsPimA conformation, the thermal stabilities of the free and bound protein were compared in solution by DSC and CD. The temperature dependence of the partial molar heat capacity (Cp) of free MsPimA revealed a significant heat absorption peak occurring at a low temperature (T½ = 46.5 °C; Fig. 3A and Table 1). Cp for the native state was linear with temperature (dCp/dT ∼ 0.27 kcal K−1 mol−1) as expected (29, 30). As shown in Fig. 3A, at high temperatures the Cp of MsPimA approaches the value of the completely unfolded state calculated from the known sequence, assuming that all amino acid residues are exposed to water (29). Because the partial heat capacity of a protein is a very sensitive indicator of the exposure of protein groups to water (29, 30), it can be concluded that upon completion of the large heat absorption peak, MsPimA is completely unfolded. Thus, MsPimA unfolds with a small total heat capacity increment (ΔCp(60 °C) = 2.4 kcal K−1 mol−1 at 60 °C) (Fig. 3A, Ref. 38).

TABLE 1.

Unfolding parameters of free and bound MsPimA measured by DSC

T1 and T2 are temperatures at half denaturation.

| Ligand | T1 | DHu,1 | DDHu,1a | T2 | ΔHu,2 | ΔDHu,2a | DHub | ΔDHu,intc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | kcal mol−1 | % | °C | kcal mol−1 | % | kcal mol−1 | kcal mol−1 | |

| 45.0 ± 0.2 | 33.8 ± 0.7 | 46.9 ± 0.2 | 53.1 ± 0.7 | 86.9 ± 1.4 | ||||

| GDP-Man | 47.9 ± 0.1 | 55.6 ± 0.5 | 58.4 ± 6.9 | 49.2 ± 0.1 | 68.6 ± 0.5 | 41.6 ± 5.9 | 124.2 ± 1.0 | 21.7 ± 2.6 |

| GDP | 48.9 ± 0.1 | 57.3 ± 0.5 | 94.4 ± 5.9 | 50.4 ± 0.1 | 54.5 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 4.8 | 111.8 ± 1.0 | 10.7 ± 2.6 |

| PI | 43.9 ± 0.2 | 32.9 ± 1.0 | −3.0 ± 6.0 | 46.2 ± 0.2 | 23.6 ± 1.0 | −97.0 ± 16.4 | 56.5 ± 2.0 | −31.7 ± 3.6 |

| GDP + PI | 48.7 ± 0.1 | 51.5 ± 0.5 | −31.2 ± 8.7d | 50.0 ± 0.1 | 41.7 ± 0.5 | −68.8 ± 12.8d | 93.2 ± 1.0 | −5.0 ± 2.6 |

a ΔΔHu is the ΔHu difference of an unfolding transition between the bound and free MsPimA protein. It is expressed as % of total unfolding enthalpy difference between the bound and free protein.

b ΔHu is the total unfolding enthalpy, ΔHu = ΔHu,1 + ΔHu,2.

c DDHu,int is the change of intrinsic unfolding enthalpy of MsPimA in the protein complexes (Equation 2; see “Experimental Procedures”). Mean values ± S.E. are reported for T½ and ΔHu based on three independent DSC experiments per protein samples. Errors for ΔΔHu and DDHu,int were calculated literally.

d ΔΔHu, same as in footnote a, taking the unfolding of MsPimA-GDP complex as reference.

Both GDP-Man and PI induced large and opposite effects on the Cp curve (Fig. 3A) upon binding to MsPimA. Whereas GDP-Man increases the thermal stability of the protein, as well as its cooperativity of unfolding, PI acts in a reversed way (compare the temperatures and the peak heights and widths of the various molecular species in Fig. 3A). The same opposing trends were observed upon binding of product GDP to free MsPimA or PI to the MsPimA-GDP complex, respectively. Differences in the Cp curve of MsPimA could be quantified easily by considering the molar excess heat capacity function (Cp,ex) (Fig. 3, B–D). The Cp,ex curve of free MsPimA is asymmetric with a gradual increase in heat uptake at low temperature followed by a sharper transition peak at high temperature, consistent with a complex unfolding process (Fig. 3B). Calculation of Cp,ex showed two overlapping unfolding transitions separated by 1.9 °C with a 1.6-fold difference in unfolding enthalpy, in agreement with the unfolding of the two domains of MsPimA (Fig. 3B and Table 1). The binding of GDP-Man (and GDP) shifts the unfolding of the two domains toward higher temperatures while largely increasing the unfolding enthalpies (e.g. T1 increased by 3.9 °C, whereas ΔHu,1 increased by 23.5 kcal mol−1 on GDP binding; Table 1). Conversely, PI binding to free MsPimA (and to the MsPimA-GDP complex) shifted the unfolding of the two domains toward lower temperatures while largely decreasing the unfolding enthalpies (e.g. T2 decreased by 0.7 °C while ΔHu,2 decreased by 29.5 kcal mol−1; Table 1).

The simultaneous changes of the two unfolding transitions show that the two domains of MsPimA unfold cooperatively. However, a comparison of the enthalpy changes upon GDP and PI binding clearly shows that although both ligands affect the unfolding enthalpy of the entire protein, GDP predominantly interacts with the low temperature (and PI with the high temperature) melting domain of MsPimA (ΔΔHu,1 = 94% and ΔΔHu,2 = −97% of ΔHu of the GDP and PI complexes, respectively; Table 1). GDP-Man increases, almost evenly, the unfolding enthalpies of the two transitions.

Taken together, the large differences between the unfolding cooperativity and unfolding enthalpy of free and bound MsPimA clearly demonstrate large conformational changes in the protein upon substrate binding. The importance of these conformational changes can be estimated in terms of energy. The difference in MsPimA intrinsic unfolding enthalpy between the free and substrate-bound states (ΔΔHu,int, Equation 2) reflects the number of noncovalent interactions lost or gained by the protein on substrate binding. ΔΔHu,int was obtained by subtracting the binding enthalpy (ΔHbind (24) from the unfolding enthalpy difference (between the bound and free states of the protein (Table 1). Values of ΔΔHu,int are large as a result of GDP-Man and PI binding and, of note, almost equal and of opposite sign (ΔΔHu,int = 28 kcal/mol and −32 kcal/mol for the GDP-Man and PI complexes, respectively; Table 1).

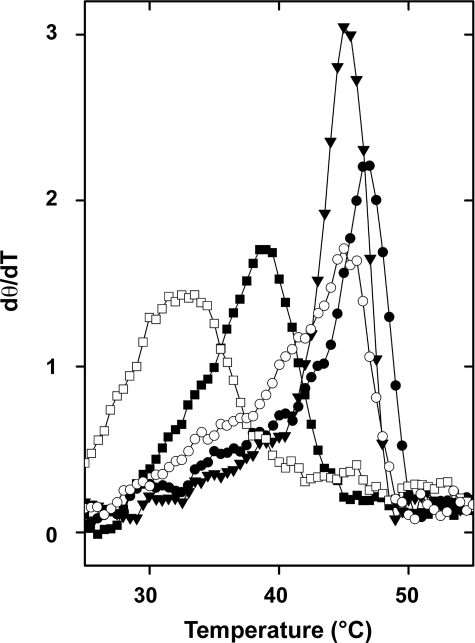

CD experiments were performed, confirming the two-domain unfolding process of MsPimA as well as the changes in thermal stability of the MsPimA complexes (Fig. 4). Changes in the ellipticity of free and bound MsPimA at 222 nm as a function of temperature clearly reproduced the asymmetry of the Cp curves as well as the T½ and unfolding cooperativity differences evidenced by DSC.

FIGURE 4.

Thermal unfolding of MsPimA alone and in complex with its substrates as monitored by circular dichroism. The first derivative of the ellipticity change at 222 nm is recorded as a function of the temperature. MsPimA (■), and MsPimA complexes with PI (□), GDP-Man (▾), GDP (●), and GDP and PI (○).

Hydrodynamic Properties of Free and Substrate-bound MsPimA

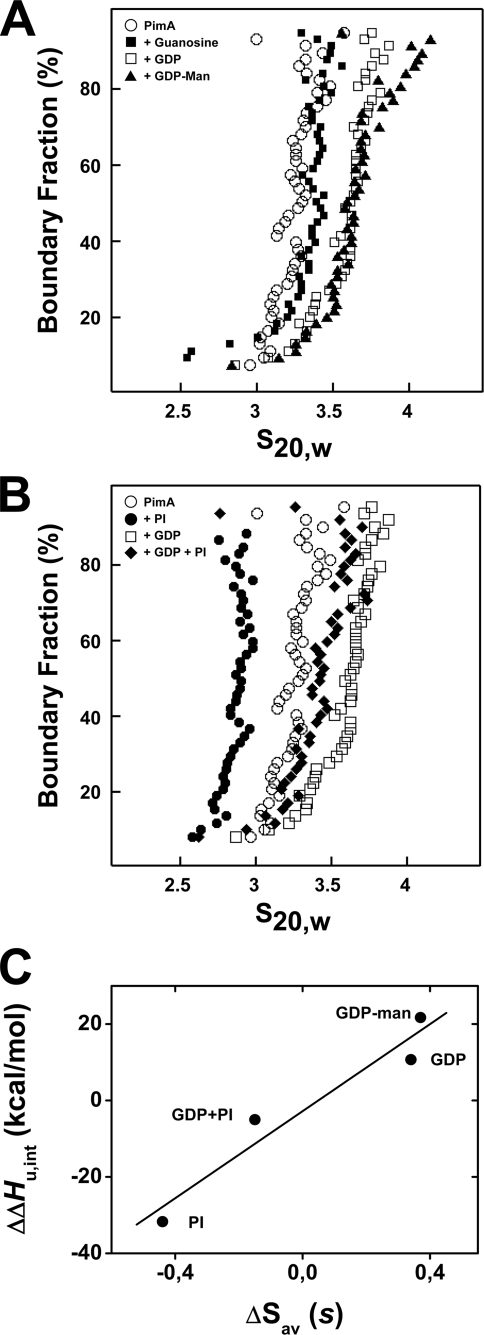

AUC, an accurate tool for the determination of hydrodynamic properties of proteins in solution, has been used successfully for detecting and characterizing substrate-induced conformational changes (39). To monitor the conformational changes in PimA in the absence and presence of GDP-Man, GDP, guanosine, and PI, sedimentation velocity AUC studies of pure MsPimA were performed. Velocity data were analyzed and corrected for diffusion using the boundary analysis method of Demeler and van Holde (31, 32). The diffusion-corrected sedimentation coefficient distributions are plotted in Fig. 5. The nearly vertical distribution (s) indicates that MsPimA sedimented as a single homogeneous species with an average sedimentation coefficient of 3.22 s, which is consistent with a moderately asymmetric (f/f0 = 1.4) monomeric protein (Table 2, Fig. 5A). Upon the addition of equimolar GDP or GDP-Man, the sedimentation coefficients increased slightly to 3.53 and 3.50 s, respectively. Taking into the account the apparent 1:1 stoichiometry of binding and the relatively insignificant increase in the molecular weight of the complexes due to binding of these ligands, this change indicates the formation of a slightly more symmetrical and compact structure (Table 2, Fig. 5A). In contrast, the presence of guanosine did not significantly affect the sedimentation coefficient value of MsPimA, consistent with the requirement of the enzyme for the β-PO4 to achieve the closed conformation.

FIGURE 5.

AUC studies of MsPimA and of MsPimA-substrate complexes. A and B, sedimentation velocity. MsPimA was incubated alone (○) or with equimolar amounts of guanosine (■), GDP (□), GDP-Man (▴), PI (●), and GDP-PI (♦) prior to sedimentation velocity. The resulting integral distribution of s (corrected for water at 20 °C (s20,w)) is shown. C, correlation between MsPimA compaction and unfolding energy variations inside the various protein-substrate complexes. For each MsPimA complex, the intrinsic unfolding enthalpy variation of the protein, ΔΔHu,int (Table 1), is plotted against the sedimentation coefficient variation of the protein complex, ΔSAV (Table 2). Linear fit of the data gives ΔΔHu,int = −1.995 + 54.129 × ΔSAV with r = 0.958.

TABLE 2.

Hydrodynamic properties of free and bound MsPimA measured by AUC

| SAVa | DSAVab | f/f0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MsPimA | 3.22 ± 0.05 | 1.40 ± 0.02 | |

| MsPimA + GDP-Man | 3.50 ± 0.14 | 0.28 ± 0.14 | 1.29 ± 0.01 |

| MsPimA + GDP | 3.53 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 1.27 ± 0.01 |

| MsPimA + GUA | 3.21 ± 0.11 | −0.01 ± 0.12 | 1.40 ± 0.01 |

| MsPimA + PI | 2.79 ± 0.04 | −0.43 ± 0.06 | 1.61 ± 0.03 |

| MsPimA + GDP + PI | 3.33 ± 0.13 | −0.20 ± 0.14c | 1.35 ± 0.01 |

a SAV and ΔSAV are in Svedberg units (S).

b SAV variation with respect to free MsPimA.

c SAV variation with respect to the MsPimA-GDP complex. Mean values ± S.E. are reported based on two independent AUC experiments using two different preparations of MsPimA.

The addition of PI to MsPimA resulted in a more significant change in the distribution and a resulting change in the average s-value from 3.22 to 2.79 s, consistent with the formation of a significantly less compact structure. PI also induced a conformational change of the MsPimA-GDP complex, in agreement with the proteolysis experiments (Table 1, Fig. 5B). It is noteworthy that the differences in MsPimA compactness among the various substrate complexes paralleled the variation of unfolding energy of the protein substrate complexes (ΔΔHu,int; Table 1). As shown in Fig. 5C, a linear correlation is observed between the sedimentation coefficient variations and the intrinsic unfolding enthalpy variations of MsPimA inside the various protein complexes (Tables 1 and 2). These observations are in agreement with the existence of large conformational changes of MsPimA between a more relaxed or “open” PI-bound conformation and a more compact or closed GDP-bound conformation. Furthermore, the linear correlation between ΔSAV and ΔΔHu,int together with the opposite values of ΔSAV and ΔΔHu,int on GDP-Man and PI binding strongly suggests that the formation of the open and closed protein conformations results from the disruption and formation of the same intra protein contacts.

Molecular Architecture of Ins-P Binding Site

Despite much effort, we were unable to crystallize MsPimA-GDP-PI ternary complexes even when assaying PI derivatives such as Ins-P, glycerophosphoryl-myo-inositol, 1,2-dibutyryl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol, or 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol. To describe the architecture of the MsPimA Ins-P binding site, we thus generated a three-dimensional model of the MsPimA-GDP-Man-Ins-P complex by in silico molecular docking approaches. The Ins-P ring was placed in a well-defined pocket with its O2 atom favorably positioned to receive the mannosyl residue from GDP-Man (Fig. 6, A and B). Interestingly, the overall structure of MsPimA is very similar to that of the recently solved MshA from Corynebacterium glutamicum (CgMshA) even though the sequence identity of the two proteins is low (24%, after structural alignment) (Fig. 6A). MshA is involved in the biosynthesis of mycothiols where it catalyzes the transfer of N-acetylglucosamine from UDP-N-acetylglucosamine to Ins-P. The structure of MshA has been determined both in the absence of substrates and in complex with UDP and Ins-P (17). A detailed comparison of the CgMshA-UDP-Ins-P complex with the three-dimensional model of MsPimA-GDP-Man-Ins-P revealed common features in the Ins-P binding site (Fig. 6B). Thus, the C-terminal domain of MsPimA (residues 1–169 and 349–373) superimposes well with the equivalent domain in CgMshA (residues 1–196 and 390–409) (r.m.s.d. of 1.8 Å for 171 aligned residues, 31% identity). In addition, the central β-sheet of the N-terminal domains of MsPimA (residues 170–348) and CgMshA (residues 197–389) display a similar topology (r.m.s.d. of 2.8 Å for 162 aligned residues, 19% identity).

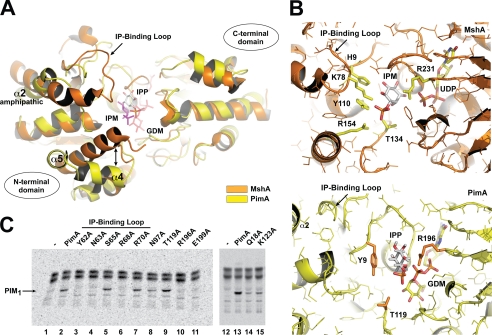

FIGURE 6.

Molecular architecture of the inositol binding site. A, structural alignment between MsPimA (PDB code 1GEJ (yellow)) and CgMshA (PDB code 3C4V (orange)). B, detailed comparison of the Ins-P binding sites from MsPimA and CgMshA. C, enzymatic activities of wild-type MsPimA and selected mutants (see “Experimental Procedures”). TLC autoradiograph of the incorporation of GDP-[14C]Man into mycobacterial membrane mannolipids from M. smegmatis mc2155. Enzymatic activity is shown as a percentage of MsPimA activity (set at 100%). Lane 1, membranes alone; lane 2, membranes + MsPimAWT; lane 3, membranes + MsPimAY62A (0%); lane 4, membranes + MsPimAN63A (0%); lane 5, membranes + MsPimAS65A (100%); lane 6, membranes + MsPimAR68A (0%); lane 7, membranes + MsPimAR70A (100%); lane 8, membranes +MsPimAN97A (71%); lane 9, membranes + MsPimAT119A (100%); lane 10, membranes + MsPimAR196A (0%); lane 11, membranes + MsPimAE199A (0%); lane 12, membranes alone; lane 13, membranes + MsPimAWT; lane 14, membranes + MsPimAQ18A (9%); lane 15, membranes + MsPimAK123A (23%).

However, two important regions that interact with the Ins-P ring in CgMshA have a different conformation in MsPimA. The first one is the region including the connecting loop between β4 and α2 (residues 68–79) and the amphipatic helix α2 (residues 80–99) (Fig. 6A). This loop contains the Lys78, which as a side chain that forms an important salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of Ins-P in CgMshA (Fig. 6B, Ref. 17). We have previously shown that the equivalent loop in MsPimA (residues 59PIPYNGSVARLR70) is disordered in the crystal structure, indicating conformational flexibility. This loop is strictly conserved in all mycobacterial PimA orthologues, and its deletion drastically impairs the interaction of the protein with PI aggregates in vitro (24). To investigate the role of this loop in Ins-P binding in MsPimA, we prepared a series of five point mutants: MsPimAY62A, MsPimAN63A, MsPimAS65A, MsPimAR68A, and MsPimAR70A (Fig. 6, B and C). Using a radiometric assay (Fig. 6C) (2), no detectable activity could be observed for the MsPimAY62A, MsPimAN63A, and MsPimAR68A mutants, strongly supporting a role for these residues in Ins-P binding. The second major difference between MshA and PimA involves CgMshA α4 (residues 148–165), which has a similar length (17 residues) as the sum of two consecutive α-helices in MsPimA, α4 (residues 123–131) and α5 (residues 134–140) (Fig. 6A). The phosphate group of Ins-P makes a hydrogen bond interaction with the guanidinium group of Arg154 in CgMshA (Fig. 6B). To investigate whether the homologous MsPimA residue (Lys123) is involved in Ins-P binding, this residue was replaced by alanine. As shown in Fig. 6C, the mutant MsPimAK123A was 23% less active than MsPimAWT, suggesting an involvement of Lys123 in substrate binding.

Other important residues and their interactions in the Ins-P binding pocket are preserved in MsPimA/CgMshA (Fig. 6B), further supporting a common Ins-P binding mechanism. The residue Gln18 is structurally equivalent to Asn25 in CgMshA, which interacts with the O-4 of the Ins-P ring. Substitution of Gln18 by alanine also resulted in a strong reduction (91%) of the enzymatic activity (Fig. 6C). The O-5 hydroxyl interacts with His9 in CgMshA, which is structurally equivalent to the essential Tyr9 in MsPimA (24). In addition to the previously described Arg78 and Arg154, the side chain of Tyr110 (Thr134 in MsPimA) also forms hydrogen-bonding interactions with the phosphate moiety of Ins-P in CgMshA. This Thr134 corresponds to Thr119 in MsPimA. Moreover, Arg231, which was found to be a very important residue in delineating the substitution and conformation of the Ins-P ring in CgMshA, has an equivalent in MsPimA, Arg196, located in the β10-α8 loop (residues 194–200) in the C-terminal domain. This arginine was also found to change its conformation upon substrate binding in other GT-B enzymes (9, 16, 40). Its substitution by alanine in MsPimA completely abolished enzymatic activity (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, the MsPimA-GDP-Man-Ins-P model predicted that Glu199, which is located in the same loop as the essential residues Arg196 and Arg201, might be positioned favorably to interact with the phosphate group of Ins-P. The role of Glu199 in acceptor substrate binding was confirmed by directed mutagenesis; its replacement by alanine completely inactivated the enzyme.

Altogether, these site-directed mutants validated our model and provided evidence that Ins-P binding is defined by key interactions with residues located in the β1-α1 loop (residues 7–16), the β3-α2 loop (residues 59–70), the β6-α4 loop (residues 117–123), two α-helices (α4 and α5) from the N-terminal domain, and the β10-α8 loop (residues 194–200) from the C-terminal domain. These results also suggest that an important conformational change most likely takes place upon PI binding, in agreement with the limited proteolysis, DSC, CD, and AUC data.

Amphipathic Helix α2 Is Essential for Membrane Binding in Vivo

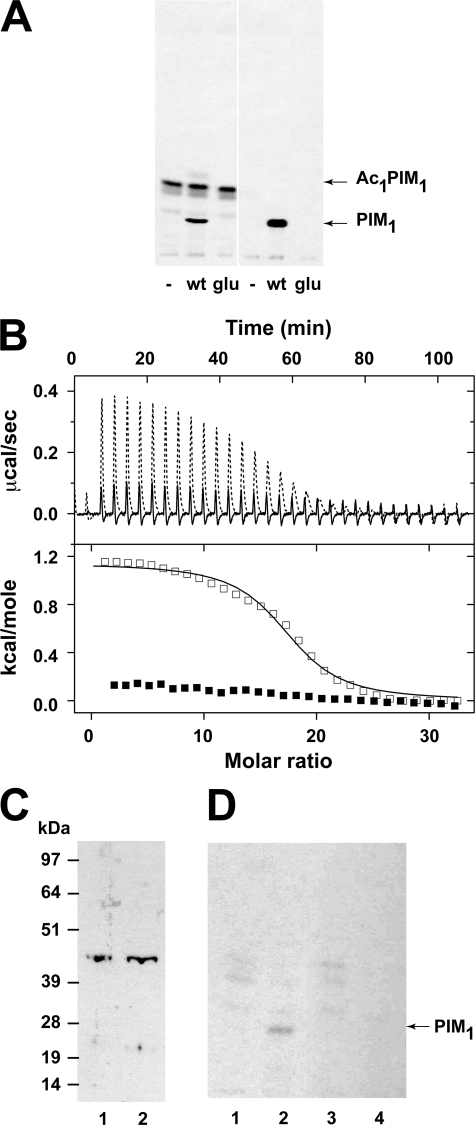

Amphipathic α-helices represent a common membrane-binding motifs in proteins. They bind to lipid membranes by a physical adsorption mechanism in which electrostatic and hydrogen bond interactions are dominant (21). This process usually follows three thermodynamic steps: (i) the binding is initiated by the electrostatic attraction of a cationic peptide to the anionic membrane head group; (ii) the peptide is then disposed into the plane of binding where its exact position depends on the hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance of the molecular groups and forces involved; and (iii) the bound peptide changes its conformation. In some cases peptides that are in random coil conformation in solution can adopt an α-helix conformation when associated with the lipid membrane (22). There is evidence suggesting that PimA binds to the membrane in a process mediated by electrostatic interactions (24). Although the enzyme lacks hydrophobic transmembrane α-helices, it has been localized to a subfraction of the plasma membrane, termed PMf. A salt wash of the PMf fraction significantly reduces the synthesis of PIM1 (41). Moreover, the addition of negatively charged lipids (e.g. cardiolipin or 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate) to a reaction mixture that included sub-critical mycelle concentrations of the acceptor 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol drastically increased enzymatic activity (24). We have previously postulated that the amphiphatic α2 might be an important recognition element to determine binding of PimA to the membrane. To further investigate this possibility, four amino acid substitutions were introduced by replacing Arg77, Lys78, Lys80, and Lys81 with glutamic acid residues (MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E). These basic residues are well conserved in other PimA orthologues including Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium leprae, and M. tuberculosis (24). These substitutions by negatively charged residues completely inactivated MsPimA (Fig. 7A). The binding properties of MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E were further compared with those of the wild-type protein using ITC. The mutant protein was observed to bind GDP with a binding affinity in the submicromolar range in an enthalpy-driven reaction (ΔH = −12.7 kcal mol−1, ΔH/ΔG = 149%) similar to that observed for the wild-type protein (ΔH = −14.0 kcal mol−1, ΔH/ΔG = 136%), strongly suggesting that the integrity of the protein was not affected by the amino acid substitutions. Instead, significant differences were observed in the membrane binding properties of the wild-type and mutant enzymes. MsPimA binds phospholipid aggregates (micelles or liposomes), and these interactions induce significant increase in the enzyme activity (24). When MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E was assessed for PI binding at a high PI concentration (Fig. 7B), no detectable binding (Kd > 200 μm) could be observed in conditions where the wild-type protein bound to PI aggregates of 15–20 PI molecules with high affinity (Kd ∼ 3.0 μm). Taken together, the amphipathic helix α2 seems to be a major element for MsPimA membrane interaction.

FIGURE 7.

The MsPimA amphiphatic α2 is essential for membrane binding in vivo and in vitro. A, enzymatic activity of MsPimA and MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E mutant expressed in E. coli cells. TLC autoradiograph of the incorporation of GDP-[14C]Man into mycobacterial membrane mannolipids from M. smegmatis mc2155. Lane 1, membranes alone; lane 2, membranes + MsPimA; lane 3, membranes + MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E; lane 4, PI alone; lane 5, PI + MsPimA; lane 6, PI + MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E. B, ITC binding isotherms for the binding of PI aggregates to the MsPimA-GDP (□) and MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E-GDP (■) complexes at 25 °C. Heats of injections were corrected for the heat of dilution of PI and normalized to the concentration of PI injected. Solid and dotted lines correspond to best fit of data using a bimolecular interaction model. C, Western blot analysis of the cytoplasmic fractions of M. smegmatis mc2155 cells expressing: lane 1, MsPimA; lane 2, MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E. The recombinant proteins were detected using anti-His-tag antibodies. D, cytosol fractions were used for the enzymatic activity assays of MsPimA and MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E mutants expressed in M. smegmatis mc2155 cells. TLC autoradiograph of the incorporation of GDP-[14C]Man into PIM1. Lane 1, MsPimA cytosol alone; lane 2, MsPimA cytosol + PI; lane 3, MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E cytosol alone; lane 4, MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E cytosol + PI.

The mutated MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E gene was then expressed in M. smegmatis mc2155, and the cytosolic and membrane fractions from the recombinant strain were prepared and used in in vitro assays (2). Although production of PIM1 was observed in the cytosol in the strain overproducing MsPimAWT upon addition of PI, no PIM1 was formed under the same conditions in the strain overproducing MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E (Fig. 7, C and D). Because M. smegmatis produced similar amounts of PimA when transformed with MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E or with MsPimAWT (Fig. 7C), this result was clearly not due to a defect in the production of the recombinant protein. That MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E encodes an inactive protein was also confirmed by complementation experiments. As mentioned above, it has been established that PimA is an essential enzyme of M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis (2). 4 Using a homologous recombination strategy, we found that whereas the wild-type chromosomal locus of pimA in M. smegmatis could be disrupted in the presence of a rescue copy of MsPimA, MsPimAR77E/K78E/K80E/K81E failed to rescue the knock-out mutant (data not shown). The amphiphatic α2 helix is thus required for activity in vivo. Taken together, these results strongly argue in favor of the amphiphatic helix α2 as being a major MsPimA component in membrane interaction, which seems to be essential for the growth of mycobacteria.

A Model of Action for PimA

The substrate-induced conformational changes and the mutagenesis studies described above support a mechanism for the binding of the donor and lipid acceptor substrates that seems to be of importance during catalysis. According to this model, the donor GDP-Man induces a striking conformational change from an open to a closed state wherein the β-PO4 plays a critical role in the stabilization of the enzyme (Fig. 8A). The open to closed motion brings together critical residues from the N- and C-terminal domains, allowing the formation of a functionally competent active site. When the lipid acceptor PI binds to PimA, an opposite structural rearrangement takes place that destabilizes the enzyme. It could be speculated that PI binding allows the initiation of the enzymatic reaction and induces the ”opening“ of the protein in order to release the products.

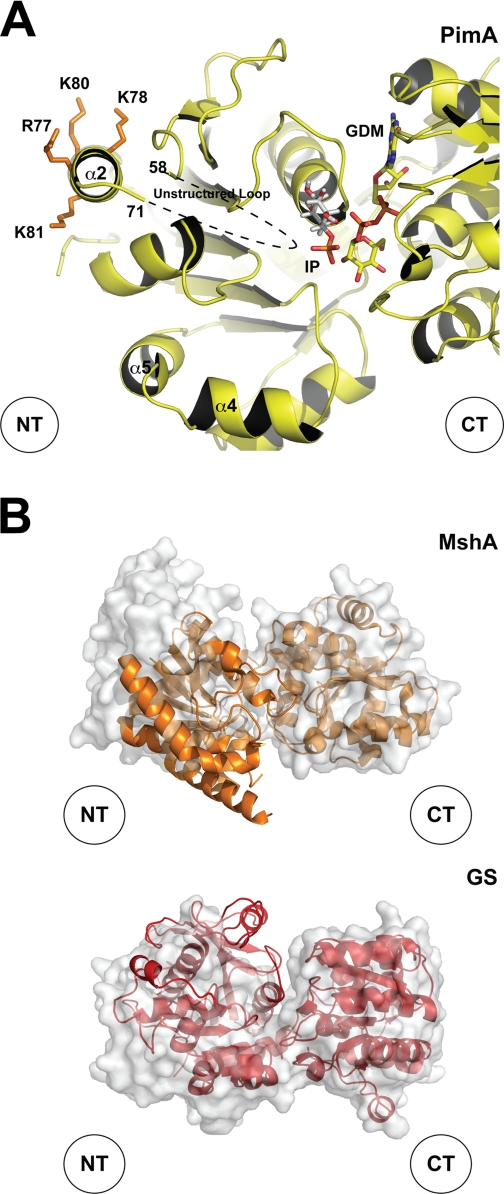

FIGURE 8.

A proposed model of action for PimA. A, schematic representing the secondary structure of a selected region of MsPimA including the GDP-Man binding site, the Ins-P binding site, and the amphipathic α2 helix involved in membrane association. B, structural comparison between the open (molecular surface representation) and closed (schematic) states of MshA from C. glutamicum and GS from A. tumefaciens.

Several lines of evidence support this model. The crystal structures of the MsPimA-GDP and MsPimA-GDP-Man complexes revealed that the proteins crystallize in a closed conformation. Both structures superimpose well (r.m.s.d. of 0.3Å for 361 identical residues), clearly showing that residues Gly16, from the N-terminal domain, and Arg196/Lys202, from the C-terminal domain, participate in the stacking interaction of β-PO4 upon GDP or GDP-Man binding (24). These residues are largely conserved not only in PimA orthologues from other mycobacterial species but also in other GT-B enzymes (14). For instance, structural comparisons of the free and nucleotide-diphospho-sugar-bound forms of CgMshA and the glycogen synthase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens (AtGS) revealed that an important subdomain rotation is required to achieve the closed state (Fig. 8B) (16, 17). Residues Gly23, Arg231, and Lys236 in MshA and Gly18, Arg299, and Lys304 in AtGS interact with the β-PO4 of uridine 5′-diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) and adenosine 5′-diphosphate glucose (ADP-Glc), respectively. Interestingly, these amino acids occupy the same location as the residues Gly16, Arg196, and Lys202 in the closed conformation of MsPimA. The catalytic mechanism of retaining GT-B enzymes is still a controversial matter of debate. Recent work suggests the direct implication of the β-PO4 in catalysis in the context of the proposed SNi internal return mechanism. This model proposes that the β-PO4 is responsible for the nucleophilic attack of the acceptor substrate and the cleavage of the sugar-nucleotide bond (17).

How does PimA recognize PI? The answer to this question is still incomplete, in part because no direct structural information is available for any peripheral membrane-binding GT in the presence of its lipid acceptor substrate. In general, peripheral membrane-binding proteins tend to penetrate one leaflet of the lipid bilayer membrane. In the case of PimA, this interaction is mediated mainly by electrostatic forces located in the essential amphiphatic helix α2 on the N-terminal domain. Our site-directed mutagenesis studies not only validate the position of Ins-P in a pocket in close proximity with the α2 helix and the mannose ring of GDP-Man but also suggest an important rearrangement of two α-helices (α2 and α4) after PI binding. Furthermore, our biophysical studies strongly argue in favor of the formation of a new open state after PI binding.

Structural Similarity with Peripheral Membrane-binding GT-B Superfamily

GTs have been classified into distinct families based on amino acid sequence similarities. Within each family, GTs are expected to adopt a unique three-dimensional fold (see the CAZy data base). On the basis of this classification, the three-dimensional structures of 12 GT-B family representatives, including GT1, GT4, GT5, GT9, GT10, GT20, GT23, GT28, GT35, GT63, GT70, and GT80, have been reported. As shown in supplemental Table 2S, GTs from families GT5 (e.g. GS (16)), GT20 (e.g. OtsA (9)), GT35 (e.g. GP (42)), GT63 (e.g. BGT (13)), and GT72 (e.g. AGT (40)) are soluble proteins with no indication of membrane association and include both retaining and inverting enzymes. In contrast, families GT9 (e.g. WaaC (43)), GT10 (e.g. FucT (44)), GT23 (e.g. FUT8 (45)), GT28 (e.g. MurG (15)), GT70 (e.g. GumK (46)), and GT80 (e.g. ST1 (47)) comprise exclusively peripheral membrane-associated proteins, all of which are inverting enzymes. Peripheral membrane-associated GTs were also observed or predicted in the retaining GT4 family (e.g. PimA), indicating that the membrane association process is independent of the catalytic mechanism. Interestingly, the GT1 family, like the GT4 family, includes both soluble and membrane-associated proteins, where members of family GT1 bind membranes using a variety of mechanisms including transmembrane α-helices, amphipathic α-helices, and protein-protein interactions (20, 48).

It was reported previously that the calculation of the isoelectric points in GT-B enzymes lacking transmembrane domains proved to be useful in discriminating soluble from peripheral membrane-bound proteins (19). Typically, N-terminal domains have higher pI values than C-terminal domains, reflecting the presence of a positively charged surface, including potential amphipathic α-helices. The electrostatic surface potential of MsPimA reveals a polar protein with a positively charged N-terminal domain (pI 8.1) in agreement with the presence of the amphipathic helix α2 (24). A detailed comparison of MsPimA with the available three-dimensional structures of GT-B enzymes reveals the presence of amphipathic α-helices in the N-terminal domains of some homologues including WaaG (GT4), WaaC and WaaF (GT9), MurG (GT28), and GumK (GT70), all of which are peripheral membrane-associated proteins (supplemental Fig. 4S). Interestingly, a similar mechanism of membrane association was also recently described for GT-A enzymes (49). The close proximity between the amphipathic α-helices and the acceptor binding site may be required to improve the efficient glycosylation of membrane-bound compounds such as PI. As lipid acceptors exhibit a huge diversity of structures, the corresponding N-terminal recognition domains in GT-B GTs are not expected to display significant similarities in their tertiary structures. In fact, the N-terminal domains in PimA, WaaG, WaaC, WaaF, MurG, and GumK are structurally more distant (r.m.s.d. of 2.5–3.4 Å) than the nucleotide-diphospho-sugar-binding C-terminal domains (r.m.s.d. of 2.2–2.9 Å) as a consequence of the different rearrangement of secondary structural elements. Although the superimposition of the N-terminal domains shows that the amphipathic α-helices display very different orientations, all of them have been found to be exposed to the solvent and disposed almost perpendicular to the entrance of the interdomain cleft. Inspection of these structures also indicates the presence of a pocket compatible with a putative binding site for lipid acceptor in close proximity to the positively charged clusters. These observations suggest a common molecular mechanism of membrane association and lipid recognition for this family of peripheral membrane-binding GTs.

Conclusions

PimA catalyzes an essential step in the biosynthesis of PIMs, key structural elements of the cell envelope of mycobacteria that also play a role in host-pathogen interactions. The enzyme is a paradigm of a large family of peripheral membrane-binding GTs for which the molecular mechanism of substrate/membrane recognition and catalysis is unknown. This article reports a detailed investigation of the substrate-induced conformational changes of PimA in solution. Altogether, our findings support the notion that flexibility and conformational transitions confer adaptability of PimA to the donor/acceptor substrates and to the membrane, which is essential for the reaction to take place. The proposed mechanism has fundamental implications for the comprehension of the early steps of PimA-mediated PIM biosynthesis as well as of peripheral membrane-binding GTs at the molecular level.

Substrate-induced conformational changes in proteins are known to be critically important in drug discovery and development strategies (50). Given the fact that PimA is an essential enzyme for mycobacterial growth, the information presented here may thus prove valuable in the rational design of specific PimA inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Karolin Luger (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Colorado State University) for providing us with full access to their protein purification facilities. We also thank Dr. Otto Pritsch (Unit of Protein Biophysics, Pasteur Institute of Montevideo, Uruguay) and Dr. Silvia Altabe (Department of Microbiology, Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology of Rosario, Argentina) for valuable scientific discussions and Dr. Steven McBryant (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Colorado State University) for help with AUC experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI064798 from NIAID. This work was also supported by the Infectious Disease SuperCluster at Colorado State University, Institut Pasteur Program GPH-5, Contract 01-B-0095 from the Ministère de la Recherche, France, and European Commission Contract LSHP-CT-2005-018923 (New Medicines for Tuberculosis).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1S–4S and Tables 1S and 2S.

- GT

- glycosyltransferase

- PIM

- phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannoside

- PI

- phosphatidyl-myo-inositol

- PIM1

- phosphatidyl-myo-inositol monomannoside

- MsPimA

- PimA from Mycobacterium smegmatis

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- DSC

- differential scanning calorimetry

- AUC

- analytical ultracentrifugation

- Ins-P

- myo-inositol 1-phosphate

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- r.m.s.d.

- root-mean-square deviation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lairson L. L., Henrissat B., Davies G. J., Withers S. G. (2008) Ann. Rev. Biochem. 77, 521–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korduláková J., Gilleron M., Mikusova K., Puzo G., Brennan P. J., Gicquel B., Jackson M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31335–31344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briken V., Porcelli S. A., Besra G. S., Kremer L. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 53, 391–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg S., Kaur D., Jackson M., Brennan P. J. (2007) Glycobiology 17, 35R–56R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilleron M., Jackson M., Nigou J., Puzo G. (2008) The Mycobacterial Cell Envelope (Daffe M., Reyrat J. M. eds) pp. 75–105, ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persson K., Ly H. D., Dieckelmann M., Wakarchuk W. W., Withers S. G., Strynadka N. C. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 98–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lairson L. L., Withers S. G. (2004) Chem. Commun. 20, 2243–2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lairson L. L., Chiu C. P., Ly H. D., He S., Wakarchuk W. W., Strynadka N. C., Withers S. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28339–28344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson R. P., Turkenburg J. P., Charnock S. J., Lloyd R., Davies G. J. (2002) Chem. Biol. 9, 1337–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coutinho P. M., Deleury E., Davies G. J., Henrissat B. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 328, 307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies G. J., Gloster T. M., Henrissat B. (2005) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 637–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charnock S. J., Davies G. J. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 6380–6385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vrielink A., Rüger W., Driessen H. P., Freemont P. S. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 3413–3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wrabl J. O., Grishin N. V. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 314, 365–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu Y., Chen L., Ha S., Gross B., Falcone B., Walker D., Mokhtarzadeh M., Walker S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 845–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buschiazzo A., Ugalde J. E., Guerin M. E., Shepard W., Ugalde R. A., Alzari P. M. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 3196–3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vetting M. W., Frantom P. A., Blanchard J. S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15834–15844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morita Y. S., Sena C. B., Waller R. F., Kurokawa K., Sernee M. F., Nakatani F., Haites R. E., Billman-Jacobe H., McConville M. J., Kinoshita T. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25143–25155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lind J., Rämö T., Rosen Klement M., Bárány-Wallje E., Epand R., Epand R. F., Mäler L., Wieslander A. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 5664–5677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X., Weldeghiorghis T., Zhang G., Imperiali B., Prestegard J. H. (2008) Structure 16, 965–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seelig J. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1666, 40–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieprecht T., Apostolov O., Beyermann M., Seelig J. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerin M. E., Buschiazzo A., Korduláková J., Jackson M., Alzari P. M. (2005) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 61, 518–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerin M. E., Kordulakova J., Schaeffer F., Svetlikova Z., Buschiazzo A., Giganti D., Gicquel B., Mikusova K., Jackson M., Alzari P. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20705–20714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaeffer F., Matuschek M., Guglielmi G., Miras I., Alzari P. M, Béguin P. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 2106–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiseman T., Williston S., Brandts J. F., Lin L. N. (1989) Anal. Biochem. 179, 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hible G., Renault L., Schaeffer F., Christova P., Zoe Radulescu A., Evrin C., Gilles A. M., Cherfils J. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 352, 1044–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plotnikov V. V., Brandts J. M., Lin L. N., Brandts J. F. (1997) Anal. Biochem. 250, 237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makhatadze G. I., Privalov P. L. (1990) J. Mol. Biol. 213, 375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griko Y. V., Freire E., Privalov G., Van Dael H., Privalov P. L. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 252, 447–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demeler B., Behlke J., Ristau O. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 321, 38–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Demeler B., van Holde K. E. (2004) Anal. Biochem. 335, 279–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holm L., Park J. (2000) Bioinformatics 16, 566–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLano W. L. (2003) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abagyan R. A., Totrov M. M., Kuznetsov D. N. (1994) J. Comp. Chem. 15, 488–506 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubbard S. J. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1382, 191–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furukawa K., Tagaya M., Tanizawa K., Fukui T. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 23837–23842 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Privalov P. L., Dragan A. I. (2007) Biophys. Chem. 126, 16–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lebowitz J., Lewis M. S., Schuck P. (2002) Protein Sci. 11, 2067–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moréra S., Larivière L., Kurzeck J., Aschke-Sonnenborn U., Freemont P. S., Janin J., Rüger W. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 311, 569–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morita Y. S., Velasquez R., Taig E., Waller R. F., Patterson J. H., Tull D., Williams S. J., Billman-Jacobe H., McConville M. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21645–21652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Reilly M., Watson K. A., Schinzel R., Palm D., Johnson L. N. (1997) Nat. Struct. Biol. 4, 405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grizot S., Salem M., Vongsouthi V., Durand L., Moreau F., Dohi H., Vincent S., Escaich S., Ducruix A. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 363, 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun H. Y., Lin S. W., Ko T. P., Pan J. F., Liu C. L., Lin C. N., Wang A. H., Lin C. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9973–9982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ihara H., Ikeda Y., Toma S., Wang X., Suzuki T., Gu J., Miyoshi E., Tsukihara T., Honke K., Matsumoto A., Nakagawa A., Taniguchi N. (2007) Glycobiology 17, 455–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barreras M., Salinas S. R., Abdian P. L., Kampel M. A., Ielpi L. (2008). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25027–25035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ni L., Chokhawala H. A., Cao H., Henning R., Ng L., Huang S., Yu H., Chen X., Fisher A. J. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 6288–6298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miley M. J., Zielinska A. K., Keenan J. E., Bratton S. M., Radominska-Pandya A., Redinbo M. R. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 369, 498–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leipold M. D., Kaniuk N. A., Whitfield C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1257–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teague S. J. (2003) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2, 527–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.