Abstract

Objective

To produce a simple, effective, and inexpensive training ophthalmoscope.

Design

Case study.

Setting

A coffee table in a sitting room and an eye clinic.

Participants

10 friends and relatives, several patients, and a cooperative Persian cat.

Interventions

Direct ophthalmoscopy with instrument made with easily available material and tools from art and office equipment shops.

Main outcome measures

Efficiency, clarity of view, and price of ophthalmoscope.

Results

The instrument was readily made; of the 50 manufactured two thirds gave a good view; and each cost less than £1 to make.

Conclusion

The ophthalmoscope is fun to make, works well, and anyone can make one.

Introduction

As a medical student in Lahore, I wished I had my own ophthalmoscope but could not afford one. Now retired after 40 years in the NHS, I decided to try to make one.

The ophthalmoscope was invented in December 1850 by Helmholtz (fig 1).1–3 He had neither the Leclanché dry cell battery (1867) nor Edison's electric light bulb (1881), yet he succeeded. In his original invention he looked through one side of a glass plate while light was reflected into the subject's eye from the other.

Figure 1.

Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-94), inventor of the ophthalmoscope

The modern ophthalmoscope is a highly sophisticated but expensive instrument. I reasoned that with modern materials it should be possible to make a simple, efficient, and inexpensive ophthalmoscope that medical students and doctors might make for themselves. A mirror made from reflecting card in one of my grandson's books showed me how I could avoid working with glass.

Materials and methods

Materials

—Black card of gauge 300 g/m2, mirror card such as Mirriboard (white card with a reflecting surface on one side), adhesive tape such Sellotape, and a pen torch.

Tools—Scissors, pointed scalpel, ruler, protractor, pencil, and stencil to draw circles.

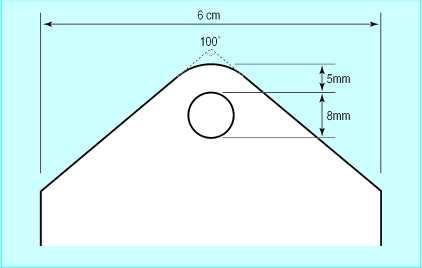

Manufacture—One end of a 14×6 cm length of black card is shaped as shown in figure 2. The card is rolled lengthways into a tube round the barrel of a pen torch and secured with adhesive tape. Its bevelled upper end is covered with an oval piece of mirror card with a 2.5 mm viewing hole just below its centre, reflecting side down. The edge of the hole, especially anteriorly, is covered by overlapping it with the edge of a 2 mm hole in a disc of black card to prevent glare.

Figure 2.

Design for the ophthalmoscope tube

The ophthalmoscope is now ready (fig 3). The pen torch is inserted, and light intensity is adjusted by advancing or withdrawing the torch. The instrument weights 2.6 g without the torch and 32 g with the one I used. Six pen torches (code FFE980, NHS Logistic Authority, April 2000) can be purchased for £4.35 (72.5p each). The other materials used to make one ophthalmoscope cost 2.5p. Outside the NHS pen torches cost £1.91-£3.49.

Figure 3.

Front view of ophthalmoscope. Note sight hole seen through light aperture. (Pen torch not shown)

Results

I made 50 ophthalmoscopes. Two thirds of these gave a good view. I tried the ophthalmoscope on 10 relatives and friends aged 1-72 years and obtained a good view in all but one (small pupils). A consultant ophthalmologist colleague tested it in his clinic and was surprised by the clarity of the view. With him, I saw macular degeneration, retinal haemorrhage, glaucomatous cupping, etc. I then taught two non-medical people how to use it. One, a nurse, described the optic disc as “like a sunset.” Finally I saw the optic fundi of my Persian cat, Tabley. I could see the vessels and dark discs clearly against the brilliant tapetal glow of the upper fundi, and I also saw the black pigmented and rather mysterious non-tapetal lower fundi.4 Tabley showed only curiosity.

Discussion

All countries are struggling to keep up with the soaring costs of their health services and of training medical students and doctors. This includes teaching direct ophthalmoscopy. My ophthalmoscope costs 75p ($1.13).

Charles Babbage, the British mathematician, actually invented the first ophthalmoscope in 1847, but the surgeon friend he gave it to failed to use it, and it was not reported until 1854. Helmholtz is therefore rightly credited with the invention.5 Modern manufactured ophthalmoscopes are exquisitely intricate instruments: even the less expensive ones cost £80-£130, and their range of lenses and lights are rarely used by the non-specialist. Common problems for the novice learning to operate one include breath holding, difficulty keeping both eyes open to relax the accommodation and avoid strain, blocking the subject's gaze with the head, and difficulty aligning the view with the light beam and the subject's pupils. These difficulties can be largely ironed out by practising with my ophthalmoscope at home. My instrument would allow the beginner to study the normal fundus and appreciate its beauty before moving on to diseased fundi. I could find no reference to a similar instrument.

Of course, the instrument does have flaws. The light beam gives light and dark patches and is not polarised. The field of view is small. The absence of lenses may cause problems in some cases of ametropia, but these may be partially resolved by allowing myopic subjects to keep their glasses on and by asking hypermetropic subjects to try to focus on a near object.6 However, this simple device should enable the user to achieve considerable skill at direct ophthalmoscopy and to prepare for advanced training. It should be taken everywhere—I carry mine in my top pocket—and it is fun at parties (fig 4).

What is already known on this topic

Most medical students and doctors do not own their own ophthalmoscopes

What this study adds

For less than £1, a home-made training ophthalmoscope can be produced that works well on most people

Figure 4.

A spectrum of training ophthalmoscopes. A black lining is necessary with light-coloured instruments to prevent glow. Note black glare shields

Acknowledgments

I thank Mr Bachittar Sandhu, consultant ophthalmologist, for trying the instrument; my family, friends, and cat for allowing me to observe their optic fundi; and Mrs Clair Daniel for typing the paper. I also thank the staff of the Lister Hospital library and the department of medical photography and illustration.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The instrument may be offered for manufacture in a modified form.

References

- 1.Duke-Elder WS. Parson's diseases of the eye. 12th ed. London: J and A Churchill; 1954. pp. 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman H. Vom Ohrenspiegel zum Augenspiegel und zurück [From otoscopy to ophthalmoscopy and back again] Laryngo-Rhino-Otology. 1995;74:707–717. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-997830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helmholtz H. Beschreibung eines Augenspiegels zur Untersuchung der Netzhaut im lebenden Auge [Description of an eye mirror for the investigation of the retina of the living eye]. Berlin. 1851. . (The original monograph could not be found by the major British libraries as it is extremely rare. Recently a copy was found in the Bascomb Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, Florida. I thank P Kelly and JEE Keunen for locating it and R Hurtes for supplying it.) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RG, Bedford P. In: Small animal ophthalmology. 2nd ed. Peiffer RL, Petersen-Jones SM, editors. London: WB Saunders; 1997. p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duke-Elder WS. Textbook of ophthalmology. Vol 1, part 2, 2nd impression with corrections. London: Henry Kimpton; 1938. pp. 1159–1160. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trevor-Roper PD, Curran PV. The eye and its disorders. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1984. pp. 225–227. [Google Scholar]