Abstract

Purpose

To determine the effects of endogenous elevation of homocysteine on the retina using the cystathionine β-synthase (cbs) mutant mouse.

Methods

Retinal homocysteine in cbs mutant mice was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Retinal cryosections from cbs−/− mice and cbs+/− mice were examined for histologic changes by light and electron microscopy. Morphometric analysis was performed on retinas of cbs+/− mice maintained on a high-methionine diet (cbs+/− HM). Changes in retinal gene expression were screened by microarray.

Results

HPLC analysis revealed an approximate twofold elevation in retinal homocysteine in cbs+/− mice and an approximate sevenfold elevation in cbs−/− mice. Distinct alterations in the ganglion, inner plexiform, inner nuclear, and epithelial layers were observed in retinas of cbs−/− and 1-year-old cbs+/− mice. Retinas of cbs+/− HM mice demonstrated an approximate 20% decrease in cells of the ganglion cell layer (GCL), which occurred as early as 5-weeks after onset of the HM diet. Microarray analysis revealed alterations in expression of several genes, including increased expression of Aven, Egr1, and Bat3 in retinas of cbs+/− HM mice.

Conclusions

This study provides the first analysis of morphologic and molecular effects of endogenous elevations of retinal homocysteine in an in vivo model. Increased retinal homocysteine alters inner and outer retinal layers in cbs homozygous mice and older cbs heterozygous mice, and it primarily affects the cells of the GCL in younger heterozygous mice. Elevated retinal homocysteine alters expression of genes involved in endoplasmic reticular stress, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation, cell cycle, and apoptosis.

Homocysteine is a sulfur-containing, nonproteinogenic amino acid that is an intermediate in methionine metabolism. Markedly elevated levels of homocysteine are induced in humans by homozygous mutations in the enzymes cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) or N5,N10-methylene tetrahydrafolate reductase (MTHFR).1,2 CBS is an enzyme involved in the transsulfuration pathway of homocysteine. It mediates the conversion of homocysteine to cystathionine, which is then converted to cysteine. MTHFR reduces N5,N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to N5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate. Homozygous mutations in these enzymes result in a severe phenotype characterized by premature thromboembolism, severe mental deficits, lens dislocation, and skeletal abnormalities.3 Heterozygous mutations in cbs and mthfr or nutritional deficiencies of the vitamins folate, B12, or B6 are more common and lead to moderate elevations of plasma homocysteine. Moderate elevation of homocysteine has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disorders,4 including ischemic heart disease, stroke, and hypertension,5 and of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.6,7 There have been reports of hyperhomocysteinemia in patients with diabetes mellitus,8–11 the prevalence of which is increasing markedly.12

Homocysteine, like the neurotransmitter amino acid glutamate, is excitotoxic when elevated extracellularly.13 The neurotoxic effects of glutamate on retina are well known, whereas less is known about the effects of homocysteine on the retina. Several clinical studies implicate homocysteine in maculopathy, open-angle glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy.14–19 A recent report of a child with severe hyperhomocysteinemia due to methionine synthase deficiency demonstrated decreased rod response and retinal ganglion cell loss as analyzed by ERG and visual evoked potential.20 Other complications of hyperhomocysteinemia include glaucoma and optic atrophy.3 Glaucoma, one of the most common causes of visual impairment especially in older persons, is characterized by ganglion cell death and optic neuropathy.21 In the presence of hyperhomocysteinemia, glaucoma is thought to be caused by an increased intraocular pressure, secondary to lens dislocation.3 However, several recent studies have reported elevated levels of homocysteine in the plasma, aqueous humor, or tear fluid of patients with glaucoma.18,22–25

Over the past several years, we have explored the direct effects of homocysteine on the viability of retinal ganglion cells. Our initial in vitro studies explored a ganglion cell line derived from rat (RGC-5). Using this cell line, we determined that homocysteine induces apoptotic cell death; however, millimolar concentrations of homocysteine were necessary for such toxicity.26 To determine whether these observations had physiologic relevance, we established primary ganglion cells as a model for testing homocysteine toxicity. Using ganglion cells immunopanned from neonatal mouse retina, we found that micromolar concentrations of homocysteine were sufficient to induce significant cell death.27 Direct injection of micromolar concentrations of homocysteine into mouse vitreous provided the first in vivo experimental evidence of homocysteine-induced apoptotic ganglion cell death.28

Although these studies have established the detrimental effects of exogenous homocysteine on the retina, much less is known about the consequences of endogenously elevated levels of homocysteine. In the present study we used a transgenic animal model to investigate the effects of endogenous elevations of homocysteine on the retina. This mouse model, originally developed in the laboratory of Nobuyo Maeda (Osaka Medical School, Japan),29 has a deletion of the gene coding for cbs. As a consequence, the homozygous mice (cbs−/−) have an approximate 30-fold increase in plasma homocysteine levels (∼200 μM compared with ∼6 μM in wild-type mice) and a markedly shortened lifespan of only 3 to 5 weeks. The cbs−/− mice are a useful model of extreme elevations of homocysteine. Heterozygous mice (cbs+/−) have an approximate fourfold increase in plasma homocysteine, with a lifespan comparable to that of wild-type mice, making them a valuable model for slight elevation of endogenous homocysteine. Dietary supplementation of drinking water with methionine increases plasma homocysteine levels in cbs+/− mice to approximately sevenfold compared with levels in wild-type mice.30

The availability of the cbs mouse model offers a unique opportunity to examine in vivo the effects of long-term exposure of endogenously elevated levels of homocysteine to the retina. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that ganglion cell death and retinal disruption would be the consequence of endogenous hyperhomocysteinemia. In addition, we sought to provide insight into mechanisms of homocysteine-induced retinal disease through examination of the alterations in gene expression.

Methods

Animals

A total of 89 mice were used in the study (Table 1). Breeding pairs of cbs+/− mice (B6.129P2-Cbstm1Unc/J) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The development of this cbs-knockout mouse has been described by Watanabe et al.29; genotyping of mice was performed per their published method. The mice were maintained in clear plastic cages and exposed to 12-hour alternating light/dark cycles (light levels, 6.0–10.0 lux). Room temperature was 23 ± 1°C. The animals were fed a special rodent diet (Teklad no. 8604; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) and given tap water ad libitum. To generate cbs+/− high-methionine mice (cbs+/− HM), cbs+/− mice were given tap water containing methionine (final concentration, 0.5%) starting from the weaning period. Maintenance and treatment of animals adhered to the institutional guidelines for the humane treatment of animals and to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Table 1.

Average Mouse Weights of cbs Mutant Mice on Regular and HM Diets

| Treatment Group/Diet | n | Weight (g) | Age at Analysis/Diet Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular diet | |||

| cbs+/+ | 18 | 9.72 ± 1.18 | 3 wk |

| 8 | 19.26 ± 1.48 | 8 wk | |

| 7 | 22.40 ± 1.41 | 18 wk | |

| 5 | 24.11 ± 2.55 | 33 wk | |

| 2 | 41.98 ± 0.16 | >52 wk | |

| cbs+/− | 9 | 9.19 ± 0.14 | 3 wk |

| 3 | 37.33 ± 2.49 | >52 wk | |

| cbs−/− | 8 | 6.95 ± 0.01 | 3 wk |

| HM diet | |||

| cbs+/− HM | 13 | 18.91 ± 1.56 | 8 wk/5 wk |

| 7 | 24.42 ± 1.39 | 18 wk/15 wk | |

| 8 | 27.07 ±1.13 | 33 wk/30 wk |

Weight is expressed as the mean ± SEM. For those groups on regular diet, the duration was lifetime.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

HPLC analysis to measure retinal levels of homocysteine and glutathione was performed on neural retina isolated from 3-week-old wild-type, cbs+/−, and cbs−/− mice. Tissue for each sample group was homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline and analyzed according to the method of Sawuła et al.31 Commercial instrumentation was used that included a controller (LCNet II), a solvent mixing module (MX-2080-31), an autosampler (AS-2055), and a fluorescence detector (FP-1520; all by Jasco, Inc., Easton, MD). Two columns were used to execute this experiment (Supelco C18 [25 × 4.6 mm], and the Supel-guard C18 [20 × 4.6 mm]; Ascentis, Bellefonte, PA). Homocysteine and glutathione levels were measured as the fluorescence emitted by the marker 7-fluorobenzofurazan-4-sulfonic acid that tags thiol groups, normalized to the internal standard, N-acetyl cysteine. All chemicals used were purchased from Sigma Life Sciences (St. Louis, MO). The homocysteine and glutathione content of the tissue samples was calculated by using a standard curve. Values were normalized to protein content of the samples. Protein levels were estimated by the published method of Lowry et al.32 Two individual samples were prepared for each test group and measurements were repeated in duplicate.

Immunohistochemical Studies

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on frozen sections, as described previously.27 Sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, washed, and blocked (PowerBlock; Biogenx, San Ramon, CA) for 1 hour. The sections were incubated overnight in a humidified chamber at 4°C with a rabbit anti-mouse polyclonal antibody against homocysteine (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). For detection of immunopositive signals, retinal sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 555–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) secondary antibody (1:1000). Slides were washed in PBS, incubated with a 1:24,000 dilution of Hoechst stain, coverslipped, and viewed by epifluorescence microscope (Axioplan-2 equipped with the Axiovision Program and an HRM camera; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Oberkochen, Germany). All immunostaining experiments were performed in duplicate.

Microscopic Evaluation and Measurement Procedures

Mice were euthanatized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation, followed by cervical dislocation. Both eyes were enucleated and flash frozen in OCT (Tissue-Tek; Miles Laboratories, Elkhart, IN) by immersion in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections (10 μm) were obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Microscopic evaluation of retinas included scanning tissue sections for evidence of gross disease followed by systematic morphometric analysis, which included measurements of cell height of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), the number of cell rows in the inner nuclear layer (INL) and outer nuclear layer (ONL), the thickness of these layers, the thickness of the inner and outer plexiform layers (IPL and OPL), and the thickness of the inner and outer segments of the photoreceptor cells (IS and OS). The number of cells in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) was expressed as cell count per 100 μm. Measurements were made with three adjacent fields on the nasal and temporal sides for a total of six data points. The initial image on each side was taken ∼200 μm from the optic nerve. Layer thicknesses were measured at a single point in each field. All measurements were made by microscope (Axioplan-2 and an HRM camera; Carl Zeiss Meditec) and quantified (AxioVision ver. 4.5.0.0. program; Carl Zeiss Meditec). The average of measurements for these six images in each eye was determined for each animal, and an overall average was calculated for each parameter in each test group. In addition, eyes from cbs−/− mice (age, 3 weeks) were processed for electron microscopy according to our published method.33

Microarray Analysis

RNA was isolated from neural retinas of wild-type and cbs+/− HM mice at 5 weeks after onset of the methionine diet. Total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA probes (FairPlay Microarray labeling kit; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). These probes were labeled with Cy3 or -5 monofunctional reactive dye (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ). Hybridization of cDNA to mouse oligonucleotide slides (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD) was performed in triplicate at 43°C for 16 hours. Fluorescence imaging was obtained using a scanner (Genepix 4000B and Genepix Pro 4.1 software; Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). The Cy3/Cy5 intensity ratios were normalized and subsequently analyzed with commercial software (JMP; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to compare the gene expression profiles quantitatively.

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between retinal homocysteine levels in cbs mutant mice compared with wild-type mice. For morphometric studies, the two-sample t-test was used to determine whether there were significant differences in morphologic measurements between mouse groups in the hyperhomocysteinemia studies. Tukey's paired comparison test was the post hoc statistical test. Data were analyzed (NCSS 2007; NCSS, Kaysville, UT), with P < 0.05 considered to show significance.

The statistical validity of changes in gene expression levels obtained from microarray analysis was confirmed with Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM), a method published by Tusher et al.34 Genes with a q < 0.06 were considered significant.

Results

Levels of Homocysteine in Retinas of cbs Mutant Mice

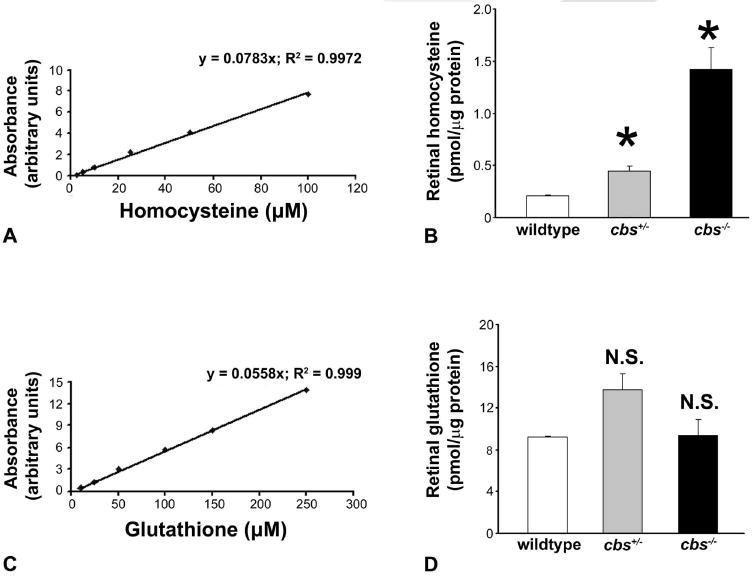

Plasma levels of homocysteine have been reported in cbs+/− and cbs−/− mice,29 but there is no information available on the levels of homocysteine in the retina of these mice. To determine these levels, we measured homocysteine in retinas of 3-week-old wild-type (cbs+/+), cbs+/−, and cbs−/− mice by HPLC. Figure 1A shows the data for the standard curve used to derive the homocysteine levels in retinas of the three groups of mice (Fig. 1B). Retinas of wild-type mice had low levels of homocysteine (0.21 ± 0.01 pmol/μg protein). Retinas of cbs+/− mice, known to have a two- to fourfold elevation of plasma homocysteine, had a concurrent approximate twofold increase in retinal homocysteine (0.44 ± 0.05 pmol/μg protein). Cbs−/− mice have extreme hyperhomocysteinemia, with plasma levels 30-fold that of wild-type mice. Retinal levels in these mice were approximately seven times greater than in wild-type mice (1.42 ± 0.21 pmol/μg protein). The increase in the retinal levels of homocysteine in heterozygous (cbs+/−) and homozygous (cbs−/−) mice was statistically significant compared with values in wild-type mice (P < 0.002).

Figure 1.

Quantification of homocysteine and glutathione in neural retina. Neural retina was subjected to HPLC analysis. (A) Standard curve used for derivation of homocysteine content; (B) homocysteine content. (C) Standard curve used for derivation of glutathione content; (D) glutathione content. *Significantly different from wild-type mice (P < 0.05); NS, not significantly different from wild-type (n = 12 wild-type, 6 cbs+/−, and 4 cbs−/− mice).

The transsulfuration pathway involving CBS results in the generation of cysteine, an amino acid necessary for the synthesis of glutathione. Since cbs mutant mice have a defect in this pathway, we compared retinal glutathione levels in wild-type, cbs+/−, and cbs−/− mice. No significant differences were observed in glutathione content among the three groups (P > 0.05; Fig. 1D). Figure 1C depicts the standard curve generated to quantify glutathione levels.

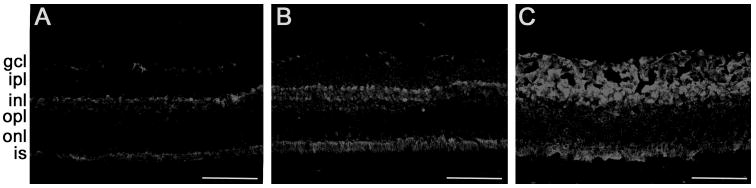

The retinal levels of homocysteine were also evaluated by immunohistochemistry using an antibody specific for homocysteine. The retinas of wild-type mice showed low levels of homocysteine (Fig. 2A), whereas retinas of 15-week-old cbs+/− mice displayed significantly elevated levels (Fig. 2B). Immunohistochemistry of retinas of mice maintained on the HM drinking water (cbs+/− HM) also showed an elevation of homocysteine (Fig. 2C). Homocysteine accumulation in cbs mutant mice was notably evident in the IPL, as well as the IS of the photoreceptor cells. These data indicate that increases in plasma homocysteine levels in cbs mutant mice are accompanied by increased homocysteine levels in the retina.

Figure 2.

Immunodetection of homocysteine in retinal cryosections. Retinal cryosections from wild-type (cbs+/+) (A), heterozygous (cbs+−) (B), and cbs+/− mice maintained 15 weeks on the HM diet (cbs+/− HM) (C) were subjected to immunodetection of homocysteine. The homocysteine-specific immunopositive signals were detected using an Alexa Fluor 555–conjugated secondary antibody. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Histologic Analysis of Mouse Retinas

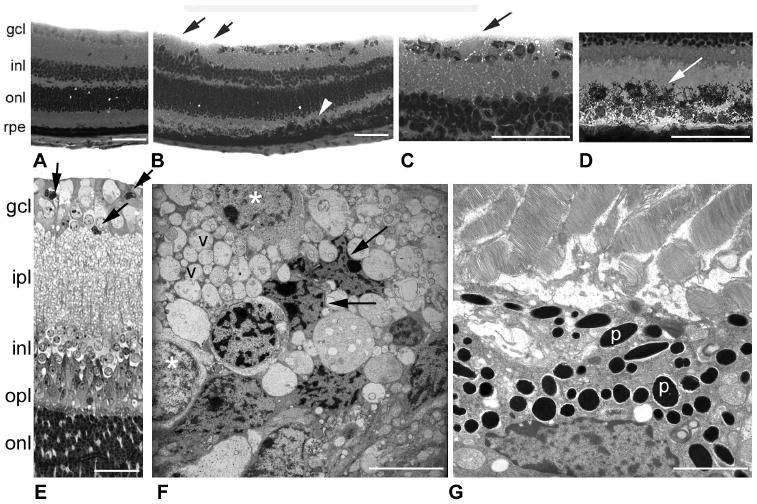

Retinas of cbs−/− mice were examined at ∼3 weeks of age, to assess the effects of high levels of homocysteine on the retina. Wild-type retinas at 3 weeks displayed cellular layers that were compact and well organized (Fig. 3A); no areas of cellular dropout in the GCL were observed. Retinas of cbs−/− mice showed retinal disruptions (Figs. 3B–D). There were fewer cells in the GCL of these retinas, with some regions devoid of cells (Fig. 3B, arrows). A higher magnification of the retina is shown in (Fig. 3C). The nerve fiber layer (NFL), which is composed of the axons of the ganglion cells, was typically thin, but in the cbs−/− mice was variable in thickness (Fig. 3C, arrow). The outer retina had more rows of photoreceptor cell nuclei (ONL) than in age-matched wild-type mice. There were areas of retina in which the RPE was disrupted (Fig. 3B, arrowhead). As seen at higher magnification (Fig. 3D), the height of the RPE was increased, there was multiple layering of cells, and in some regions there was marked dispersion of pigment granules into the region of the OS (Fig. 3D). Retinas of cbs−/− mice were prepared for electron microscopy (Figs. 3E–G). The thickened, vacuolated region of the NFL is prominent in Figure 3E and is shown at the ultrastructural level in Figure 3F. Some of the ganglion cells had shrunken, crenated nuclei (Fig. 3F, arrows), whereas adjacent cells were plump and healthy in appearance (Fig. 3F, asterisks). The nuclei of ganglion cells were surrounded by numerous vacuoles, presumably of the NFL. Figure 3G shows ultrastructural appearance of the RPE. Notable is the dense concentration of pigment granules. OS appeared generally intact in the mutant mouse retinas. Because of the limited life span of cbs−/− mice, long-term studies of the consequences of profound hyperhomocysteinemia on retina are not feasible in these homozygous mice.

Figure 3.

Histology of retinas of cbs−/− mice (age: 3 weeks). Light micrographs of hematoxylin and eosin-stained retinal cryosections from wild-type (cbs+/+) (A) and homozygous (cbs−/−) mice (B–D). (B, black arrows) Regions of cell dropout in the GCL; (white arrowhead) regions of RPE hypertrophy. Higher magnification of cbs−/− mouse retina showing foamy appearance of the NFL (C) and excess pigmentation of the RPE (D). Light micrograph of toluidine blue–stained, plastic-embedded cbs−/− mouse retina (E). Arrows: shrunken, darkly stained cells. Ultrastructural image of the GCL and NFL regions of cbs−/− mouse retina (F). Arrows: shrunken, dying cells; (*): normal-appearing cells, v, vacuoles, which are abundant in the image. (G) An ultrastructural image of the RPE of cbs−/− mice with abundant pigment granules (p) in RPE (n = 4 wild-type, 4 cbs−/− mice). Scale bar: (A–D) 50 μm; (E) 25 μm; (F, G) 7 μm.

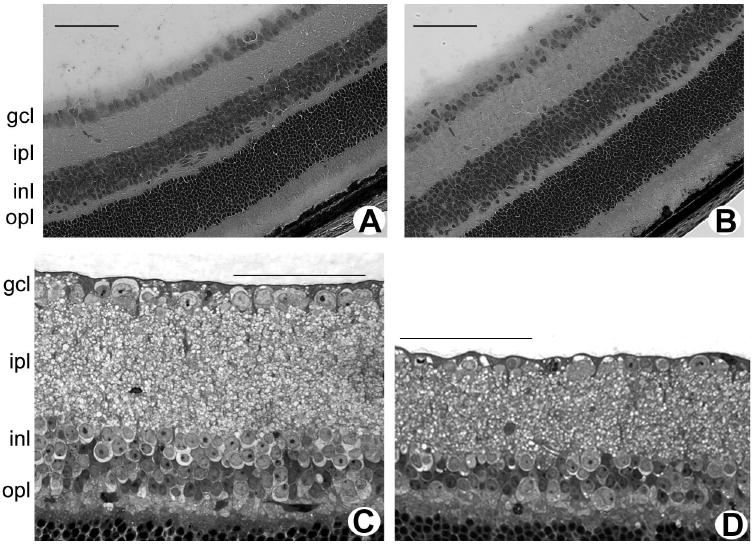

The heterozygous mice carrying only one mutant copy of the cbs gene (cbs+/−) have a normal lifespan, permitting assessment of the effects of chronic moderate hyperhomocysteinemia on retina. The retinas of cbs+/− mice (ages: 3 weeks and 1-2 years) were examined and compared to retinas of age-matched wild-type mice. At both ages, wild-type retinas were well organized and showed the normal stratification of the nuclear and plexiform layers. They displayed the typical distinct monolayer of cells in the GCL (Figs. 4A, 4C). Retinas of 3-week-old cbs+/− mice were similar to wild-type mice (Fig. 4B). Analysis of retinas of mice at this age showed that the number of cells in the GCL of cbs+/− mice was comparable to that in wild-type mice (13.05 ± 0.47 vs. 13.86 ± 0.53 cells per 100 μm, P > 0.05; n = 2 wild-type, 3 cbs+/− mice). By 1 to 2 years of age, however, cbs+/− mice had areas of cell dropout in the GCL (Fig. 4D), averaging 9.19 ± 0.55 cells per 100-μm length of retina compared with 12.51 ± 0.67 cells in wild-type mice, P < 0.05, n = 2 wild-type, 3 cbs+/− mice. At this advanced age, the IPL consistently appeared thinner in cbs+/− mice than in the wild-type control and the INL had fewer cells (approximately three rows of cells in mutants versus approximately five rows in wild-type).

Figure 4.

Histology of retinas of cbs+/− mice (age, 3 weeks and 1–2 years). Light micrographs of hematoxylin-eosin-stained cryosections of retinas of 3-week-old wild-type (cbs+/+) mice (A) and heterozygous (cbs+/−) mice (B). Light micrograph of toluidine blue–stained, plastic-embedded retinas of 1-year-old wild-type (cbs+/+) mice (C) and heterozygous (cbs+/−) mice (D). Scale bar, 50 μm.

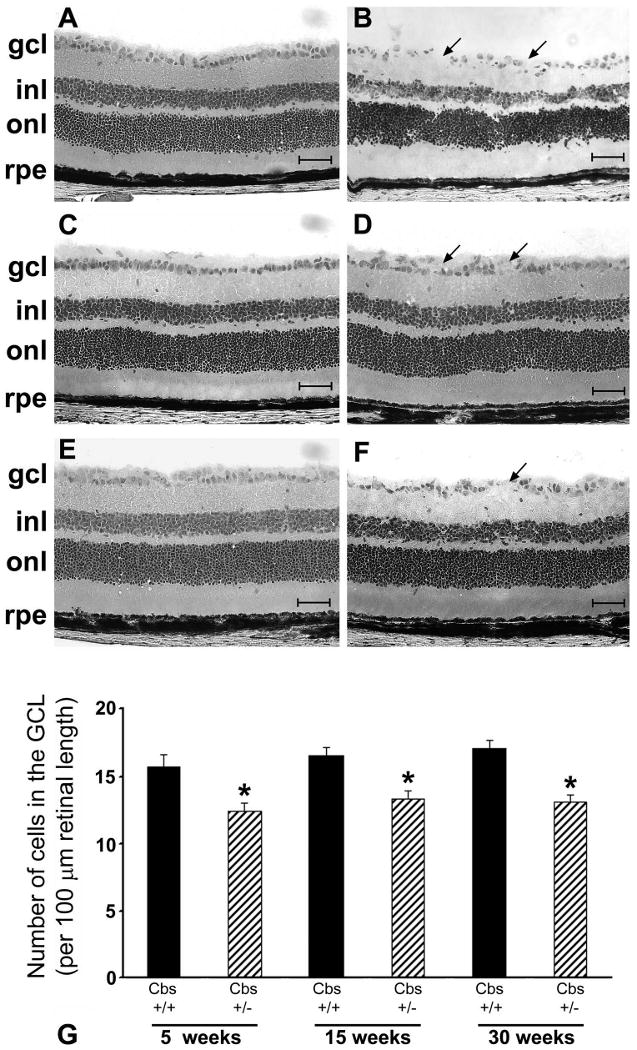

Cbs+/− mice have an approximate fourfold elevation in plasma homocysteine levels; levels can be elevated further by supplementing their drinking water with methionine at the time of weaning.30 This HM dietary supplementation leads to an approximate sevenfold increase in plasma homocysteine levels. The cbs+/− HM mice are well-suited for time-dependent examination of the effects of moderate elevations of homocysteine on retinal structure, especially the consequences on viability of cells in the GCL. Cbs+/− HM mice were analyzed at 5, 15, and 30 weeks after onset of the HM diet. The most prominent feature observed in these mice was a decrease in number of cells in the GCL in the retinas compared with the number in wild-type mice (Figs. 5A, 5B, 5 weeks; 5C, 5D, 15 weeks; 5E, 5F, 30 weeks). The distribution of cells in the GCL was uniform in the wild-type mice (Figs. 5A, 5C, 5E), whereas the cell layer became progressively uneven, with areas of cell dropout detected in the cbs+/− mice (Figs. 5B, 5D, 5F). Systematic morphometric analysis revealed that the number of cells in the GCL counted per 100-μm length of retina was decreased by ∼20% in the 5-week cbs+/− HM mice. The cell loss remained at ∼20% over this 30-week period, as shown in Figure 5G. Control mice at 5 weeks displayed a cell count of 15.67 ± 0.95 cells per 100 μm compared with a significantly decreased cell count of 12.44 ± 0.55 cells in cbs+/− HM mice (P < 0.007). Analysis showed a cell count of 13.30 ± 0.66 and 13.06 ± 0.61 cells per 100 μm GCL at 15 and 30 weeks, respectively; wild-type mice had an average of 16.72 ± 0.42 cells per 100 μm of GCL (P < 0.004). The histology of other layers of the retina remained intact in cbs+/− HM mice. A decrease in IPL thickness from 46.55 ± 1.32 to 41.01 ± 1.43 μm was observed in cbs+/− HM mice at 15 weeks (P < 0.009) and a significant decrease in INL thickness from 35.20 ± 1.47 to 30.04 ± 0.85 μm was observed in cbs+/− HM mice at 5 weeks (P < 0.008). Quantitative analysis of the number of rows of cells in the INL and ONL showed no difference between wild-type and cbs+/− HM mice at the ages studied. The average number of rows was ∼5 to 6 in the INL and ∼12 to 13 in the ONL in both mouse groups.

Figure 5.

Histology of retinas of cbs+/− mice maintained on an HM diet to promote modest elevation of plasma homocysteine. Light micrographs of hematoxylin-eosin-stained retinal cryosections of wild-type (cbs+/+) mice (A, C, E) and heterozygous mice maintained on 0.5% methionine drinking water (cbs+/− HM) (B, D, F). Retinas were harvested at 5 (A, B), 15 (C, D) and 30 (E, F) weeks. (B, D, F, arrows) Areas of cell dropout in the GCL. Scale bar, 50 μm. Retinas were subjected to morphometric analysis; data are shown in (G) and are expressed as neuronal cells/100 μm length of retina. Solid black bars: cbs+/+ HM mice; striped bars: cbs+/− HM mice. *Significantly different from wild-type mice, P < 0.05 (n = 5 weeks: three wild-type, eight cbs+/− HM mice; 15 weeks: seven wild-type, seven cbs+/− HM mice; 30 weeks: five wild-type, eight cbs+/− HM mice).

Microarray Analysis of Mouse Retinas

The effects of endogenous elevation of homocysteine on retinal gene expression were screened by microarray analysis, which was performed in triplicate (i.e., three different paired RNA samples) with RNA isolated from neural retinas of cbs+/− HM at 5-weeks after a methionine diet and age-matched wild-type mice. The microarray chips used in this study permitted the screening of 36,212 genes. Of particular interest were those genes in cbs+/− HM mice whose expression levels changed by at least a factor of 2 (increased or decreased expression) compared with the wild-type in each of the replicate experiments. Using these selection criteria, we identified 1219 genes. They were categorized into six functional groups: (1) proapoptosis, (2) antiapoptosis, (3) cell cycle, (4) antioxidant, (5) calcium signaling, and (6) axon growth/guidance, with the remaining genes with marked changes in expression placed in a miscellaneous group. After categorization, relevant genes were further narrowed by SAM analysis; q < 0.06 was considered significant.

Table 2 represents 68 selected genes with expression altered by endogenous elevations in homocysteine (the entire dataset will be deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] Gene Expression Omnibus database [Bethesda, MD] after the paper is accepted). Of note, several genes in both the pro- and antiapoptosis pathways were upregulated or downregulated in the cbs+/− HM mice. For example, the proapoptosis gene, Bat3, known to be activated in response to endoplasmic reticular stress and DNA damage,35,36 was significantly upregulated. There was a concurrent increase in the expression of antiapoptosis genes, such as Aven. Genes involved in cell cycle or transcriptional regulation were also altered; Egr1, or early growth response 1, showed an approximate fivefold increase in expression. This gene is known to be transcriptionally upregulated in response to N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation.37,38 Genes possessing antioxidant activity, including those coding for several subunits of glutathione-S-transferase and a subtype of superoxide dismutase, were downregulated in response to elevated homocysteine levels, suggesting that an increase in oxidative stress may be one mechanism by which homocysteine disrupts retinal integrity. In addition, the expression of genes involved in calcium signaling or in the removal of calcium from the cell was increased in mutant mice compared with wild-type: the gene encoding a calcium antiporter, Slc24a4, was upregulated. Examination of genes related to axon growth and guidance revealed that two genes involved in axon guidance, Efnb3 and Ablim2, showed increased expression. Tsc2, a suppressor of axon formation, was also upregulated. Of the genes categorized in the miscellaneous group, decreased expression of Vim, which codes for vimentin, proved to be interesting as upregulation of the gene is a well-known indicator of Müller cell gliosis. The expression of the gene encoding for transthyretin, Ttr, was also decreased.

Table 2.

Expression Changes of 68 Selected Genes in Retinas of cbs+/− HM Mice

| Accession Number | Gene | Function | Change (x-Fold) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proapoptosis Genes | |||

| NM_001085 409 | STEAP family member 3 (STEAP3) | p53 Signaling pathway | +3.34 |

| NM_057171 | HLA-B-associated transcript 3 (Bat3) | Regulator of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) stability in response to ER stress; regulator of p53 acetylation in response to DNA damage | +2.27 |

| NM_134062 | Death associated protein kinase 1 (Dapk1), transcript variant 2 | Tumor suppressor; p53 signaling pathway | +2.14 |

| NM_178590 | Inhibitor of kappaB kinase gamma (lkbkg), transcript variant 2 | CD40L signaling pathway; NF-κB signaling pathway; TNF/stress-related signaling; TNFR2 signaling pathway; Toll-like receptor pathway | −2.02 |

| NM_010721 | Lamin B1 (Lmnb1) | Caspase cascade in apoptosis; FAS signaling pathway (CD95); TNFR1 signaling pathway | −2.04 |

| NM_033217 | Nerve growth factor receptor (Ngfr) | Induces differentiation, tumor suppressor | −2.12 |

| NM_019752 | HtrA serine peptidase 2 (Htra2) | Promotes caspase-mediated apoptosis when dislocated from mitochondria | −2.20 |

| NM_008704 | Nonmetastatic cells 1, protein (NM23A) expressed in (Nme1) | Granzyme A mediated apoptosis pathway | −2.26 |

| NM_025562 | Fission 1 homolog (Fis1) | Mitochondrial fission; involved in intrinsic apoptosis pathways | −2.39 |

| Antiapoptosis Genes | |||

| NM_133752 | Optic atrophy 1 homolog (Opa1) | Mutated in dominant optic atrophy; role in mitochondrial fusion | +2.42 |

| NM_028844 | Aven | Caspase activation inhibitor; ATM activator in response to DNA damage | +2.31 |

| NM_009794 | Calpain 2 (Capn2) | Tumorigenic; regulator of autophagosome formation | +2.21 |

| NM_181585 | Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase, regulatory subunit, polypeptide 3 (Pik3r3) | Tumorigenic via Akt pathway | −2.09 |

| NM_025816 | Tax1 (human T-cell leukemia virus type 1) binding protein 1 (Tax|bp|) | Inhibitor of TNF-induced apoptosis | −2.11 |

| NM_053245 | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting proteinlike 1 (Aip|1) | Negative regulator of apoptosis | −2.17 |

| NM_009688 | X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (Xiap) | B-cell survival pathway; caspase cascade in apoptosis | −2.19 |

| NM_030152 | Nucleolar protein 3 (Nol3) | Inhibitor of caspase cascade | −2.19 |

| NM_011361 | Serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 (Sgk1) | Protective during oxidative stress and neurodegeneration | −2.22 |

| NM_029922 | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase family, member 6 (Parp6) | Regulates telomere elongation | −2.23 |

| NM_026669 | Testis enhanced gene transcript (Tegt) | Inhibitor of Bax | −2.32 |

| NM_009429 | Tumor protein, translationally-controlled 1 (Tpt1) | Antagonizes bax function | −2.44 |

| NM_009689 | Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 (Birc5) | B-cell survival pathway (Survivin) | −2.84 |

| NM_011810 | Fas apoptotic inhibitory molecule (Faim) | Inhibits Fas activity | −2.94 |

| Genes Involved in Cell Cycle | |||

| NM_007913 | Early growth response 1 (Egr1) | Downregulates the MAP kinase pathway; positive correlation with NMDA receptor stimulation | +4.73 |

| NM_145221 | Adaptor protein, phosphotyrosine interaction, PH domain and leucine zipper containing 1 (App11) | Regulator of Akt activity | +2.39 |

| NM_019726 | G protein pathway suppressor 2 (Gps2) | GTPase inhibitor activity; facilitates p53 activity; has been shown to interact with NR3 subunit of NMDA receptor | +2.17 |

| NM_001010 833 | Mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1 (Mdc1) | Regulates intra-S phase checkpoint in response to DNA damage | +2.03 |

| NM_028023 | Cell division cycle associated 4 (Cdca4) | Regulates cell proliferation via E2F/Rb pathway | −2.00 |

| NM_019712 | Ring-box 1 (Rbx1) | ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway; regulation of p27 phosphorylation during cell cycle progression | −2.01 |

| NM_019830 | Protein arginine N-methyltransferase 1 (Prmt1) | BTG family proteins and cell cycle regulation; control of gene expression by vitamin D receptor | −2.04 |

| NM_053089 | NMDA receptor-regulated gene 1 (Narg1) | N-terminal acetyltransferase that regulates entry into G0 phase of cell cycle; downregulated by NMDA receptor function | −2.05 |

| NM_011959 | Origin recognition complex, subunit 5-like (Orc5|) | CDK Regulation of DNA Replication | −2.16 |

| NM_008228 | Histone deacetylase 1 (Hdac1) | Deacetylation of histones; chromatin modification | −2.20 |

| NM_007836 | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha (Gadd45a) | ATM signaling pathway; cell cycle: G2/M checkpoint; p53 signaling pathway | −2.31 |

| NM_008683 | Neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated gene 8 (Nedd8) | Regulation of p27 Phosphorylation during Cell Cycle Progression | −2.43 |

| NM_007631 | Cyclin D1 (Ccnd1) | BTG family proteins and cell cycle regulation; cell cycle: G1/S check point; cyclins and cell cycle regulation; inactivation of Gsk3 by AKT causes accumulation of b-catenin in alveolar macrophages; influence of Ras and Rho proteins on G1 to S transition | −2.66 |

| NM_007691 | Checkpoint kinase 1 homolog (Chek1) | ATM signaling pathway; cdc25 and chk1 regulatory pathway in response to DNA damage; cell cycle: G2/M checkpoint; RB tumor suppressor/checkpoint signaling in response to DNA damage; role of BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATR in cancer susceptibility | −3.27 |

| NM_010730 | Annexin A1 (Anxa1) | Anti-inflammatory action; proapoptotic upon upregulation; mediates phagocytosis of apoptotic cells | −4.93 |

| Genes with Antioxidant Activity | |||

| NM_025823 | Prenylcysteine oxidase 1 (Pcyox1) | Oxidoreductase activity; prenylcysteine catabolic process | +2.85 |

| NM_145598 | Nucleoredoxin-like 1 (Nxnl1) | Cell redox homeostasis | −2.03 |

| NM_010358 | Glutathione S-transferase, mu 1 (Gstm1) | Glutathione metabolism; metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | −2.03 |

| NM_013711 | Thioredoxin reductase 2 (Txnrd2) | Mitochondrial redox homeostasis | −2.04 |

| NM_013541 | Glutathione S-transferase, pi 1 (Gstp1) | Glutathione metabolism | −2.13 |

| NM_008185 | Glutathione S-transferase, theta 1 (Gstt1) | Glutathione metabolism | −2.28 |

| NM_010357 | Glutathione S-transferase, alpha 4 (Gsta4) | Glutathione metabolism | −2.58 |

| NM_011435 | Superoxide dismutase 3, extracellular (Sod3) | Antioxidant activity | −2.61 |

| NM_025569 | Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 (Mgst3) | Glutathione metabolism | −2.68 |

| NM_010362 | Glutathione S-transferase omega 1 (Gsto1) | Glutathione metabolism | −5.18 |

| Genes Associated with Calcium Signaling | |||

| NM_172152 | Solute carrier family 24 (sodium/potassium/calcium exchanger), member 4 (Slc24a4) | Calcium ion antiporter | +3.36 |

| NM_133741 | SNF-related kinase (Snrk) | Calcium regulated Ser/Thr kinase; involved in low K+-induced neuronal apoptosis | +3.09 |

| NM_080465 | Potassium intermediate/small conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily N, member 2 (Kcnn2) | Calcium activated potassium channel activity; calmodulin binding | +2.96 |

| NM_001039 139 | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gamma (Camk2g) | Calcium signaling pathway; ErbB signaling pathway; Glioma; GnRH signaling pathway; Long-term potentiation; melanogenesis; olfactory transduction; Wnt signaling pathway | +2.52 |

| NM_001036 684 | ATPase, Ca++ transporting, plasma membrane 2 (Atp2b2) | Calcium signaling pathway | +2.51 |

| NM_007451 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier, adenine nucleotide translocator), member 5 (Slc25a5) | Calcium signaling pathway | −2.21 |

| NM_009112 | S100 calcium binding protein A10 (calpactin) (S100a10) | Calciumion binding | −2.23 |

| NM_007590 | Calmodulin 3 (Calm3) | Encodes a subunit of calmodulin, primary Ca+ binding protein | −2.24 |

| NM_011636 | Phospholipid scramblase 1 (Plscr1) | Calcium ion binding | −8.33 |

| Genes Related to Axon Growth | |||

| NM_007911 | Ephrin B3 (Efnb3), mRNA | Axon guidance | +2.69 |

| NM_177678 | Actin-binding LIM protein 2 (Ablim2) | Axon guidance | +2.66 |

| NM_001039 363 | Tuberous sclerosis 2 (Tsc2) | Control of gene expression by vitamin D receptor; mTOR signaling pathway; suppressor of axon formation | +2.53 |

| NM_016890 | Dynactin 3 (Dctn3) | Essential for axon growth cone advance; microtubule-associated complex | −2.10 |

| Miscellaneous | |||

| NM_011701 | Vimentin (Vim) | Cell communication; intermediate filament | −3.03 |

| NM_008806 | Phosphodiesterase 6B, cGMP, rod receptor, beta polypeptide (Pde6b) | 3′,5′-cyclic-GMP-phosphodiesterase activity; detection of light stimulus | −3.41 |

| NM_019439 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA-B) receptor 1 (Gabbr1) | Neuractive ligand-receptor interaction | −3.95 |

| NM_009089 | Polymerase (RNA) II (DNA directed) polypeptide A (Polr2a) | Chromatin remodeling by hSW1/SNF ATP-dependent complexes; nuclear receptors coordinate the activities of chromatin remodeling complexes and coactivators to facilitate initiation of transcription in carcinoma cells; repression of pain sensation by the Tr | −4.59 |

| NM_013697 | Transthyretin (Ttr) | Carrier protein for thyroxine and retinol binding protein | −7.13 |

| NM_207028 | Taste receptor, type 2, member 126 (Tas2r126) | Taste transduction | −7.25 |

| NM_033614 | Phosphodiesterase 6C, cGMP-specific, cone, alpha prime (Pde6c) | 3′,5′-cyclic-GMP-phosphodiesterase activity | −7.76 |

q < 0.06 for all genes included (n = 5 wild-type, 5 cbs+/− HM mice). GenBank accession numbers provided by NCBI (Bethesda, MD; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank).

Discussion

Elevations of plasma homocysteine, which are common particularly in the elderly population, are associated with increased total and cardiovascular mortality, stroke, dementia, Alzheimer's disease, bone fracture, and chronic heart failure.39 To understand the role of homocysteine in these diseases, several laboratories have used tissues from cbs mutant mice. For example, these mice were used to examine cerebral vascular dysfunction as relevant to stroke,40 endothelial dysfunction as relevant to numerous cardiovascular diseases,30 and the effects of excess homocysteine on liver homeostasis and the LDL receptor.41,42 A comprehensive list of studies performed using murine models of hyperhomocysteinemia has been described in a recent review.43

Over the past decade, elevated homocysteine has been implicated in visual diseases.14–20 including in glaucoma.3,18,44 These observations prompted the current analysis of the retinas of cbs mutant mice. Earlier work from our laboratory demonstrated that exposure of isolated retinal ganglion cells (both a cell line and primary mouse ganglion cells) to elevated levels of homocysteine induced apoptotic cell death within 18 hours of treatment.26,27 Whether these in vitro findings are relevant to the effects of homocysteine on the intact retina is not known. Our experiments in which homocysteine was injected into the vitreous cavity led to death of cells in the GCL,28 but again reflect an acute insult.

The availability of the cbs mouse allowed examination of the effects of sustained elevation of homocysteine on the retina. Of interest, the first report of this mutant mouse,29 described pathologic screening of several organs including the eye. It was stated that “no pathologic changes were notable in the eyes, knee joints, kidneys, lungs, and hearts of homozygous mice at day 21, except that they appeared immature when compared to their 21-day-old wild-type and heterozygous littermates.” That paper did not describe how the eyes were analyzed and did not mention any systematic examination of the retina. Most publications describing other tissues in the cbs mice have used heterozygous mice, since the homozygous mice die within 3 to 5 weeks of birth. In the present study, we evaluated retinas of both the homozygous and heterozygous cbs mice, and our data indicate that there were significant alterations in the retina of both groups.

The first step in our analysis of the cbs mutant retina was to determine whether elevated levels of plasma homocysteine translated to elevated levels of retinal homocysteine. The retina is separated from systemic circulation by the inner and outer blood–retinal barriers; thus, it cannot be assumed that the retina is exposed to the same level of homocysteine as other organs.29,30 Two approaches were used for this analysis: HPLC and immunohistochemistry. Both methods of analysis indicated that retinal homocysteine was elevated in homozygous and heterozygous cbs mice. HPLC analysis revealed very low levels of homocysteine in wild-type mice (∼0.21 pmol/μg protein) reflecting the tight regulation of homocysteine levels under normal conditions. Retinal homocysteine levels are approximately sevenfold greater in the cbs−/− mice compared to wild-type mice, whereas the cbs+/− have an approximate twofold elevation. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed the increase of homocysteine in these mice. These data suggest that cbs mice are relevant for analysis of excess homocysteine in retina.

After establishing that cbs mice had increased levels of retinal homocysteine, we examined retinas of several groups of mice (homozygous, heterozygous, and heterozygous fed an HM diet). Although our earlier in vitro studies examined effects of homocysteine only on ganglion cells,26,27 the analysis of retinas of the cbs mutant mice was not restricted to the GCL. In the cbs−/− mice, we observed alterations in several layers of the retina including the GCL, ONL, and RPE. Of interest, there was not a uniform ablation of cells in the GCL; rather there were pockets of cellular dropout. Examination of the retinas at the ultrastructural level showed the proximity of cells undergoing apoptosis to normal-appearing cells. The GCL is composed of two neuronal cell types: ganglion cells and amacrine cells.45 Our analysis did not distinguish between these two cell types, or the several subtypes of ganglion and amacrine cells. Nonetheless, there were fewer neurons in this cell layer, and the NFL was altered as shown by the presence of many vacuoles (unlike the uniform appearance in wild-type retinas.) The inner retina was not the only portion of the retina affected in the cbs−/− mice. The ONL had more rows of cells than in that of wild-type mice, thus appearing less differentiated. The RPE was also hypertrophic in discrete regions of cbs−/− mice and excessive pigmentation was noted. Thus, cbs−/− mice demonstrate disruptions in several retinal layers. However, many cells remained, and the laminar organization of the retina was preserved in these homozygous mice. This was somewhat surprising since in vitro studies with excessive homocysteine in isolated ganglion cells revealed marked sensitivity (leading to 50% cell death). The cbs−/− model most likely reflects the buffering capacity of this tissue to stressful insults, possibly mediated by glial cells. No studies have been performed regarding the capacity of glial cells to clear the retinal milieu of homocysteine.

Most of our analyses were performed in the heterozygous cbs mice. Examination of retinas of 1- to 2-year-old cbs+/− mice showed fewer cells in the GCL and a noticeable thinning of the retina. To accelerate our analysis of the effects of moderate elevation of homocysteine on the retina, heterozygous cbs mice were fed an HM diet.30 Morphometric analysis of the retinas of mice maintained on this diet revealed consistent loss of cells in the GCL. This was the cell layer most affected in the cbs+/− mice, although the inner plexiform and nuclear layers were also affected at 5 weeks. The HM diet commenced in heterozygous mice at the time of weaning, and retinas of mice maintained 5 weeks on this diet demonstrated an approximate 20% decrease in the number of cells in the GCL. We anticipated that there would be fewer cells in this layer with increasing age in mice that were maintained 15 and 30 weeks on this diet. However, cell loss in the GCL remained constant (∼20%). We asked whether the 20% decrease in cell number might reflect a developmental difference between heterozygous and wild-type mice, but did not observe a difference in the number of cells in this layer at 3 weeks. It is possible that the retina can buffer the effects of a modest increase in homocysteine induced by the HM diet/heterozygous gene mutation. It was not feasible to analyze retinas of the cbs−/− mice over an extended period because of their diminished viability; however, two new transgenic mouse strains have been introduced43 that could be used for long-term studies of homocysteine on retina.

It is clear from these morphologic data that sustained, moderate elevations of homocysteine alter retinal structure. It is noteworthy, however, that the retinas of cbs mutant mice (both heterozygous and homozygous) did not sustain profound disruption of retinal architecture nor massive loss of entire cellular layers (as occurs, for example, in the rd mouse in which rod photoreceptors are completely lost within the first 21 postnatal days46). This observation suggests that elevated homocysteine alters retinal gene expression and very likely upregulates not only genes that lead to apoptosis, but perhaps also those that are protective. To begin to understand the mechanisms underlying the retinal phenotype observed in the cbs mice, we initiated investigations of those retinal genes whose expression is altered due to moderate hyperhomocys-teinemia. Microarray analysis was performed to screen for gene changes in neural retinas of 5-week-old cbs+/− HM mice compared with wild-type mice; 1216 genes were identified with expression that was altered by twofold or higher. Genes whose expression was altered are consistent with reported mechanisms of homocysteine toxicity including stimulation of the NMDA receptor,47,48 increased in intracellular reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide,49,50 induction of ER stress51–53 and Ca2+ disequilibrium.54,55 Of note, the expression of some antiapoptosis genes was also increased. These preliminary findings set the stage for future comprehensive analyses of the temporal changes in gene/protein expression in this model, which will include RT-PCR, Western blot analysis, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry.

Based on the microarray screening, there are several genes that warrant comprehensive investigation over a series of ages in retinas of cbs mutant mice. These include the proapoptosis gene Bat3 because its protein product regulates apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) stability in response to ER stress-induced apoptosis35,36 as well as Aven, an inhibitor of the apoptosis pathway.56,57 The transcriptional regulator Egr1, a member of the immediate early gene (IEG) family, was increased by approximately fivefold in cbs+/− HM retinas compared with wild-type. This gene is a good candidate for future studies in cbs mutant mice, because its expression increases in response to excitotoxicity.37,38 The microarray screening revealed expression changes in several genes associated with antioxidant pathways, particularly those that use glutathione as a substrate to facilitate drug elimination (subunits of glutathione-S-transferase) and extracellular superoxide dismutase, Sod3; these genes deserve comprehensive analysis in cbs mouse retinas. The histologic observations that the NFL was altered in the cbs−/− mice and that the IPL was much thinner in the 1- to 2-year-old mice suggests that genes associated with axon guidance may also be worthy of further investigation. Genes involved in axon guidance, Ephb3 and Ablim2, were upregulated, as was expression of Tsc2, a suppressor of axon formation.58

In conclusion, this study represents the first systematic examination of the consequences of elevated homocysteine in an animal model of hyperhomocysteinemia. The data show effects on cells of the GCL in heterozygous mice, as well as in other layers in the more severe homozygous mutant mice. Future studies will examine comprehensively genes whose expression is changed under hyperhomocysteinemic conditions.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Grant R01 EY012830 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure: P.S. Ganapathy, None; B. Moister, None; P. Roon, None; B.A. Mysona, None; J. Duplantier, None; Y. Dun, None; T.K.V.E. Moister, None; M.J. Farley, None; P.D. Prasad, None; K. Liu, None; S.B. Smith, None

References

- 1.Mudd SH, Skovby F, Levy HL, et al. The natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37(1):1–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Z, Karaplis AC, Ackerman SL, et al. Mice deficient in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase exhibit hyperhomocysteinemia and decreased methylation capacity, with neuropathology and aortic lipid deposition. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(5):433–443. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mudd SH, Levy HL, Kraus JP. Disorders of transsulfuration. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, et al., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. 8th. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 2016–2040. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wierzbicki AS. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: a review of the evidence. Diabetes Vasc Dis Res. 2007;4(2):143–150. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2007.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin RC, Lentz SR, Werstuck GH. Role of hyperhomocysteinemia in endothelial dysfunction and atherothrombotic disease. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:56–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selhub J, Bagley LC, Miller J, Rosenberg IH. B vitamins, homocysteine, and neurocognitive function in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:614–620. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.2.614s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattson MP, Shea TB. Folate and homocysteine metabolism in neural plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:137–146. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aydemir O, Türkçüoğlu P, Güler M, et al. Plasma and vitreous homocysteine concentrations in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2008;28:741–743. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31816079fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ndrepepa G, Kastrati A, Braun S, et al. Circulating homocysteine levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;18:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soedamah-Muthu SS, Chaturvedi N, Teerlink T, Idzior-Walus B, Fuller JH, Stehouwer CD. Plasma homocysteine and microvascular and macrovascular complications in type 1 diabetes: a cross-sectional nested case-control study. J Intern Med. 2005;258:450–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agulló-Ortuño MT, Albaladejo MD, Parra S, et al. Plasmatic homocysteine concentration and its relationship with complications associated to diabetes mellitus. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;326:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore PA, Zgibor JC, Dasanayake AP. Diabetes: a growing epidemic of all ages. JAm Dent Assoc. 2003;134:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuénod M, Do KQ, Grandes P, Morino P, Streit P. Localization and release of homocysteic acid, an excitatory-sulfur containing amino acid. J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:1713–1715. doi: 10.1177/38.12.2254641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heuberger RA, Fisher AI, Jacques PF, et al. Relation of blood homocysteine and its nutritional determinants to age-related maculopathy in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:897–902. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.4.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Axer-Siegel R, Bourla D, Ehrlich R, et al. Association of neovascular age-related macular degeneration and hyperhomocysteinemia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:84–89. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00864-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsina EK, Marsden DL, Hansen RM, Fulton AB. Maculopathy and retinal degeneration in cobalamin C methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1143–1146. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.8.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seddon JM, Gensler G, Klein ML, Milton RC. Evaluation of plasma homocysteine and risk of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:201–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bleich S, Jünemann A, von Ahsen N, et al. Homocysteine and risk of open-angle glaucoma. J Neural Transm. 2002;109:1499–1504. doi: 10.1007/s007020200097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang G, Lu J, Pan C. The impact of plasma homocysteine level on development of retinopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus [in Chinese] Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2002;41:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poloschek CM, Fowler B, Unsold R, Lorenz B. Disturbed visual system function in methionine synthase deficiency. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243:497–500. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-1044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg EA, Sperazza LC. The visually impaired patient. Am Fam Phys. 2008;77:1431–1436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roedl JB, Bleich S, Reulbach U, et al. Homocysteine levels in aqueous humor and plasma of patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:445–450. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roedl JB, Bleich S, Reulbach U, et al. Vitamin deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia in pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. J Neural Transm. 2007;114(5):571–575. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0598-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roedl JB, Bleich S, Reulbach U, et al. Homocysteine in tear fluid of patients with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2007;16:234–239. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31802d6942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roedl JB, Bleich S, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, et al. Increased homocysteine levels in tear fluid of patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmic Res. 2008;40:249–256. doi: 10.1159/000127832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin PM, Ola MS, Agarwal N, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. The sigma receptor ligand (+)-pentazocine prevents apoptotic retinal ganglion cell death induced by homocysteine and glutamate. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;123:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dun Y, Thangaraju M, Prasad P, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Prevention of excitotoxicity in primary retinal ganglion cells by (+)-pentazocine, a sigma receptor-1 specific ligand. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4785–4794. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore P, El-sherbeny A, Roon P, Schoenlein PV, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Apoptotic cell death in the mouse retinal ganglion cell layer is induced in vivo by the excitatory amino acid homocysteine. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:45–57. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe M, Osada J, Aratani Y, et al. Mice deficient in cystathionine beta-synthase: animal models for mild and severe homocyst(e)inemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1585–1589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dayal S, Bottiglieri T, Arning E, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and elevation of S-adenosylhomocysteine in cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2001;88:1203–1209. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.092180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawuła W, Banecka-Majkutewicz Z, Kadziński L, et al. Improved HPLC method for total plasma homocysteine detection and quantification. Acta Biochim Pol. 2008;55:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SB, Duplantier JN, Dun Y, et al. In vivo protection against retinal neurodegeneration by the σR1 ligand (+)-pentazocine. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4154–4161. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desmots F, Russell HR, Michel D, McKinnon PJ. Scythe regulates apoptosis-inducing factor stability during endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3264–3271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706419200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasaki T, Gan EC, Wakeham A, Kornbluth S, Mak TW, Okada H. HLA-B-associated transcript 3 (Bat3)/Scythe is essential for p300-mediated acetylation of p53. Genes Dev. 2007;21:848–861. doi: 10.1101/gad.1534107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shan Y, Carlock LR, Walker PD. NMDA receptor overstimulation triggers a prolonged wave of immediate early gene expression: relationship to excitotoxicity. Exp Neurol. 1997;144:406–415. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giraldi-Guimarães A, de Bittencourt-Navarrete RE, Nascimento IC, Salazar PR, Freitas-Campos D, Mendez-Otero R. Postnatal expression of the plasticity-related nerve growth factor-induced gene A (NGFI-A) protein in the superficial layers of the rat superior colliculus: relation to N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function. Neuroscience. 2004;129:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selhub J. Public health significance of elevated homocysteine. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29:S116–S125. doi: 10.1177/15648265080292S116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dayal S, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, et al. Cerebral vascular dysfunction mediated by superoxide in hyperhomocysteinemic mice. Stroke. 2004;35:1957–1962. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131749.81508.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamelet J, Noll C, Ripoll C, Paul JL, Janel N, Delabar JM. Effect of hyperhomocysteinemia on the protein kinase DYRK1A in liver of mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:673–677. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noll C, Hamelet J, Matulewicz E, Paul JL, Delabar JM, Janel N. Effects of red wine polyphenolic compounds on paraoxonase-1 and lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 in hyperhomocysteinemic mice. J Nutr Biochem. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.06.002. Published online August 1, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dayal S, Lentz SR. Murine models of hyperhomocysteinemia and their vascular phenotypes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1596–1605. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.166421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clement CI, Goldberg I, Healey PR, Graham SL. Plasma homocysteine, MTHFR gene mutation, and open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:73–78. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31816f7631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farah MH. Neurogenesis and cell death in the ganglion cell layer of the vertebrate retina. Brain Res Rev. 2006;52:264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lolley RN. The rd gene defect triggers programmed rod cell death. The Proctor Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:4182–4191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Do KQ, Herrling PL, Streit P, Cuénod M. Release of neuroactive substances: homocysteic acid as an endogenous agonist of the NMDA receptor. J Neural Transm. 1988;72:185–190. doi: 10.1007/BF01243418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang D, Lipton SA. L-homocysteic acid selectively activates N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors of rat retinal ganglion cells. Neurosci Lett. 1992;139:173–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90545-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vergun O, Sobolevsky AI, Yelshansky MV, Keelan J, Khodorov BI, Duchen MR. Exploration of the role of reactive oxygen species in glutamate neurotoxicity in rat hippocampal neurones in culture. J Physiol. 2001;531:147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0147j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sattler R, Xiong Z, Lu WY, Hafner M, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M. Specific coupling of NMDA receptor activation to nitric oxide neurotoxicity by PSD-95 protein. Science. 1999;284:1845–1848. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim HJ, Cho HK, Kwon YH. Synergistic induction of ER stress by homocysteine and beta-amyloid in SH-SY5Y cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:754–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Althausen S, Paschen W. Homocysteine-induced changes in mRNA levels of genes coding for cytoplasmic- and endoplasmic reticulum-resident stress proteins in neuronal cell cultures. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 84:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00208-4. 200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jakubowski H, Perla-Kajan J, Finnell RH, et al. Genetic or nutritional disorders in homocysteine or folate metabolism increase protein N-homocysteinylation in mice. FASEB J. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-127548. Published online February 9, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dickhout JG, Sood SK, Austin RC. Role of endoplasmic reticulum calcium diequilibria in the mechanism of homocysteine-induced ER stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1863–1873. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin PY, Yang TH, Lin HG, Hu ML. Synergistic effects of S-adeno-sylhomocysteine and homocysteine on DNA damage in a murine microglial cell line. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;379:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chau BN, Cheng EH, Kerr DA, Harwick JM. Aven, a novel inhibitor of caspase activation, binds Bcl-xL and Apaf-1. Mol Cell. 2000;6:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo JY, Yamada A, Kajino T, et al. Aven-dependent activation of ATM following DNA damage. Curr Biol. 2008;18:933–942. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knox S, Ge H, Dimitroff BD, et al. Mechanisms of TSC-mediated control of synapse assembly and axon guidance. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]