Abstract

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes are critical in controlling levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are linked to aging, cancer and neurodegenerative disease. Superoxide (O2 •−) produced during respiration is removed by the product of the SOD2 gene, the homotetrameric manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD). Here, we examine the structural and catalytic roles of the highly conserved active-site residue Tyr34, based upon structure-function studies of MnSOD enzymes with mutations at this site. Substitution of Tyr34 with five different amino acids retained the active site protein structure and assembly, but causes a substantial decrease in the catalytic rate constant for the reduction of superoxide. The rate constant for formation of product inhibition complex also decreases but to a much lesser extent, resulting in a net increase in the product inhibition form of the mutant enzymes. Comparisons of crystal structures and catalytic rates also suggest that one mutation, Y34V, interrupts the hydrogen-bonded network, which is associated with a rapid dissociation of the product-inhibited complex. Notably, with three of the Tyr34 mutants we also observe an intermediate in catalysis, which has not been reported previously. Thus, these mutants establish a means to trap a catalytic intermediate that promises to help elucidate the mechanism of catalysis.

The superoxide dismutases are found in prokaryotes, archaea and eukaryotes, where they catalyze the disproportionation of the superoxide radical anion O2 •− in cellular processes detoxifying reactive oxygen species (1). The mechanism by which all superoxide dismutases carry out the catalytic removal of superoxide involves an oxidation-reduction cycle, as shown in the reactions below.

In humans three SOD enzymes exist, SOD1 is a cytoplasmic Cu,ZnSOD, SOD2 is a mitochondrial MnSOD and SOD3 is an extracellular Cu,ZnSOD. These SOD enzymes are critical in controlling levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are linked to aging, cancer and neurodegenerative disease (2). Structure-activity relationships for this class of enzymes need to be understood and distinguished, as their disease phenotypes likely occur through different mechanisms. SOD1 is a Cu,Zn dimeric enzyme with a β-barrel fold (3) with an active site channel containing a site for superoxide substrate and hydrogen peroxide product binding (4, 5) adjacent to the activity important Arg143 side chain (6). The structure of human Cu,ZnSOD resembles that of bacterial Cu,ZnSOD except the dimer contact is on the opposite surface (7, 8). For the human Cu,ZnSOD, dimer and framework-destabilizing mutations in SOD1 give rise to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease (9–11), a progressive neurological disease caused by the degeneration of motor neurons. Additionally, the Zn site of Cu,ZnSOD likely contributes to ALS (12, 13), suggesting that the presence of a bivalent metal ion site contributes to degenerative disease. MnSOD instead contains a single metal ion site and destabilizing mutations in MnSOD are not reported to cause severe disorders (14, 15), but a couple of polymorphisms are indicated in disease phenotypes (16–20). Moreover, MnSOD has a critical function in maintaining the integrity of mitochondrial enzymes that are susceptible to direct inactivation by superoxide (21).

MnSOD is a homotetrameric protein controlling the detoxification of O2•− produced as a minor side product of respiration in the mitochondria. Besides its intrinsic importance, this tetrameric MnSOD provides an important comparative enzyme of medical relevance as the smaller dimeric Cu,Zn SOD is rapidly cleared from human serum and mutants designed to form tetramers and larger assemblies result in structural distortions (22). The manganese site furthermore differs from the Cu,Zn SOD active site by being in a trigonal bipyramidal geometry with four ligands from the protein and a fifth solvent ligand (14). The bound solvent ligand is a hydroxide for the oxidized enzyme Mn3+SOD near physiologic pH; this is believed to be the acceptor for proton transfer upon reduction of the enzyme (23, 24). The structure of MnSOD resembles that of bacterial FeSOD; however, details of their active-site chemistries are different (25). Catalysis by MnSOD is subject to a substantial and reversible product inhibition by peroxide, arising from the oxidative addition of superoxide to Mn2+SOD (26). This is different from the deactivation of the active site of FeSOD through Fenton chemistry (27). The kinetics of catalysis by MnSOD is consistent with the formation of a reversible, dead-end complex, and although the structure of this complex has not been observed, spectroscopic and computational considerations seem to favor a side-on peroxo complex of the metal (26, 28). The complex was first observed as a rapidly emerging zero-order phase of catalysis (26, 29).

The active-site cavity of MnSOD is characterized by a hydrogen bonded network extending from the aqueous ligand of the metal and comprising the side chains of several residues including Tyr166 emanating from an adjacent subunit (14). Included in this network is the highly conserved residue Tyr34 (30) the side chain of which participates in hydrogen bonding with both Gln143 and an adjacent water molecule (14, 31). Tyr34 plays a key role in the hydrogen-bonding network, as nitration of the active-site residue Tyr34 causes nearly complete inhibition of catalysis (32). However, the precise role of this network in catalysis is not determined experimentally; yet, computational analyses support a role for proton transfer from Tyr34 providing one of the two protons to form H2O2 in catalysis (28). Replacement of Tyr34 in MnSOD has rather modest effects on kcat/Km of catalysis (33, 34); however kcat is decreased about ten-fold (33). The structure of human Y34F MnSOD has been determined (33) and the role of Tyr34 in the spectral and catalytic properties of human and bacterial MnSOD has been examined in several studies of Y34F MnSOD (33–37). The ionization of Tyr34 with a pKa near 9.5 is the source of spectroscopic changes in Mn3+SOD (25, 38) and probably is responsible for the decrease in catalytic activity as pH increases beyond 9 (34). There is a role of Tyr34 in avoiding product inhibition; the replacement of Tyr34 with Phe (Y34F) resulted in product inhibition greater by about 80-fold compared with wild type (35). The dissociation of hydrogen peroxide from product-inhibited enzyme is only decreased two-fold in Y34F (33) and is unchanged in a form of human MnSOD in which all tyrosine residues were replaced with 3-fluorotyrosine (39).

To address key questions regarding the role of residue 34 in MnSOD activity, we report here comprehensive mutational analyses of residue 34, which describe the effect of mutations on both the crystal structure and catalysis. The data show that substitution of Tyr34 with five different amino acids is associated with a substantial decrease in the rate constant for the reduction of superoxide in the catalytic cycle. The rate of formation of the product-inhibited complex is much less reduced however, which results in a net increase in the product-inhibited form of these mutant enzymes. Comparisons of crystal structures and rates of catalysis also indicate that interruption of the hydrogen bonded network in the active site results in a significantly increased rate of product dissociation, from the inhibited complex. Furthermore, an intermediate in catalysis that has not been reported previously is observed in three residue 34 mutants, which may eventually help elucidate the detailed molecular mechanism of catalysis.

Experimental Procedures

Crystallography

Orthorhombic crystals of Y34H and Y34N human MnSOD were grown by vapor diffusion from solutions consisting of 26 mg/ml and 24 mg/ml protein, respectively, buffered in 25 mM potassium phosphate, pH7.8 and 22% poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) 2000 monomethyl ether. Large hexagonal crystals of Y34V and Y34A human MnSOD were grown from 22 mg/ml and 18mg/ml protein, respectively, buffered in 2.5 M ammonium sulfate, 100 mM imidazole/malate buffer, pH 7.5. Single crystals were used for data collection and were cryoprotected by 20% ethylene glycol in the well solution, before freezing in a stream of liquid nitrogen. The Y34H, N and V MnSOD data sets were collected at the Stanford Synchotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) at beamline 9-1 and the Y34A mutant data set was collected at the Advanced Light Source (ALS), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory at beamline 8.3.1. The collected data sets were indexed and merged with DENZO and scaled with Scalepack (40). Phases were determined by molecular replacement from the wild-type structure using AMoRe (41). The structures were refined with several cycles of rigid body and restrained refinement, using Crystallography and NMR Systems, version 1.1 (CNS) (42). Final refinement steps for the higher resolution Y34N mutant MnSOD were completed using SHELX (43). Models were rebuilt to σA-weighted 2Fo - Fc and Fo - Fc maps using Xfit (41). The data collection and the refinement statistics of these four mutants are shown in Table 1. Atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes, ‘1ZSP.pdb’ for Y34A, ‘1ZTE.pdb’ for Y34H, ‘2P4K.pdb’ for Y34N and ‘1ZUQ.pdb’ for Y34V.

Table 1.

Crystallographic Data and Refinement Statistics.

| Dataset | Y34A | Y34H | Y34N | Y34V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit cell | P6122 | P212121 | P212121 | P6122 |

| Dimensions, a | 79.52, | 73.67 | 73.56, | 79.63, |

| b, | 79.52, | 77.84 | 73.56, | 79.63, |

| c | 242.99 | 136.22 | 136.10 | 241.64 |

| Wavelength, Å | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.95 |

| Resolution, Å | 50 – 1.9 | 37.4 – 1.85 | 39.2 – 1.48 | 39.7 – 2.0 |

| Theoretical/ | 34,791, | 67,566, | 130,469, | 31,662, |

| observed | 31,760, | 61,782, | 126,423, | 30,942, |

| reflections (last shell) | 5,658 | 8,683 | 20,100 | 4,984 |

| % Completeness | 91.2 | 91.4 | 96.9 | 97.6 |

| (last shell) | (94.6) | (82.9) | (93.4) | (96.8) |

| <I/σI>, (last shell) | 48.9 (11.5) | 15.2 (3.0) | 26.9 (5.0) | 28.6 (5.4) |

| Rmerge, (last shell) | 5.0 (15.2) | 8.6 (30.6) | 6.0 (29.9) | 5.5 (22.6) |

| Model statistics | ||||

| Rfree | 28.6 | 24.5 | 22.2 | 27.4 |

| Rwork | 23.9 | 20.6 | 16.0 | 23.5 |

| rmsd bond length, | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| angle | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| rmsd to WT MnSOD, | 0.25, 0.2 | 0.27, 0.33, | 0.26, 0.34, | 0.2, 0.25 |

| subunit a,b, c & d | 0.21, 0.26 | 0.23,0.25 | ||

Pulse radiolysis

These experiments were carried out at the Brookhaven National Lab using a 2 Mev van de Graaff accelerator. UV-visible spectra were obtained using a Cary 210 spectrophotometer with path lengths of 2.0 or 6.1 cm. Solutions contained enzyme and 30 mM sodium formate as a hydroxyl radical scavenger (44), 50 µM EDTA, and 2 mM buffer (Mops at pH 6.5–7.3; Taps at pH 7.4–9.3; Ches at pH 9.4–10.5). Reported rate constants were obtained using the manganese concentration from atomic absorption spectrometry rather than the total protein concentration, with all manganese assumed to be at the active site of MnSOD.

Superoxide radicals were generated by exposing air-saturated solutions to an electron pulse. In our solutions, the primary radicals created by the pulse are converted to superoxide by a number of scavenging reactions listed by Schwarz (44). In these experiments, superoxide formation is more than 90% complete within the first microsecond after the pulse. Catalysis was measured from the changes in absorption of superoxide (45) and of the enzyme itself (46, 47). Repeated pulses of electrons using the same enzyme sample gave identical catalytic rates; the radiolysis itself did not alter the catalysis. The data were analyzed and rate constants obtained by fits to changes in the spectra of enzyme and superoxide after generation of superoxide by pulse radiolysis. Analysis was performed using the BNL Pulse Radiolysis Program as described earlier (46, 47). Identical values were obtained by the enzyme kinetics curve-fitting package of Enzfitter (Biosoft).

Results

Crystal Structures

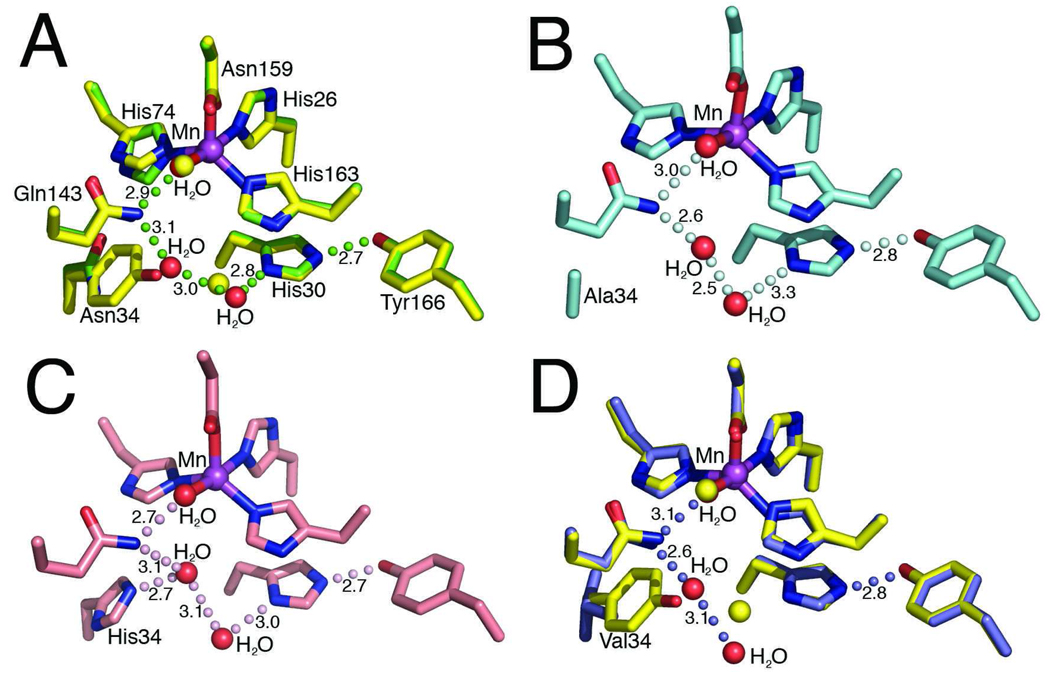

To examine the role of Tyr34 in MnSOD activity, we determined and refined x-ray crystal structures that define the effect of mutations on the detailed active site structural chemistry, as a structural framework for interpretation of their catalytic features. The Tyr34 mutants Y34A, H, N and V MnSOD mutants structurally determined in these studies demonstrate that their subunit fold and tetrameric assemblies closely resemble the wild-type structure (14), supporting the use of these mutants in mechanistic analyses. The root mean square deviations (rmsd) for superimposition of all 198 Cα atoms for each mutant structure onto the wild-type are shown in Table 1; the largest rmsd in the four mutants is only 0.34 Å from the wild-type structure, for one of the Y34N subunit structures in the asymmetric unit. These four mutant protein structures also show minimal changes to the position and orientation of the active site residues, including the manganese ion ligands (Figure 1).

Fig 1.

MnSOD active site structure and residue 34 mutations. (A) Superimposition of the active site side chains, manganese ion, and ordered solvent molecules of the human wild-type MnSOD (yellow) and Y34N (green). Y34N waters are depicted in red (wild-type waters in yellow), green spheres depict the Y34N hydrogen bond relay and the bond distances, in Å, are annotated. (B) Active site of the Y34A crystal structure, the hydrogen bonding relay is maintained and depicted in pale cyan. (C) Active site of Y34H crystal structure, with hydrogen bonding relay and distances, in Å, annotated. (D) Superimposition of the active site chains of the human wild-type MnSOD (yellow) and Y34V (blue). Replacement of Tyr34 with Val interrupts the hydrogen bond network. The Y34V waters are depicted in red (wild-type waters in yellow), and the hydrogen bond relay of Y34V MnSOD is depicted by blue spheres, and bond distances, in Å, are annotated.

In the wild-type enzyme a hydrogen-bonding network involving Tyr34 extends from the metal to Tyr166 (Mn-H2O-Gln143-Tyr34-H2O-His30-Tyr166), where Tyr166 emanates from an adjacent subunit. All the mutations tested at position 34 alter this network (Table 1). In each of the four mutant structures Y34A, N, H, and V, the replacement of Tyr34 by a smaller side chain creates a cavity that is filled by an additional water molecule (Figure 1). In three of the structures (Y34A, N, and H) this additional water molecule maintains the hydrogen-bonding network, (Figure 1A–C). This water molecule forms hydrogen bonds to Gln143 NE2 and to the water hydrogen bonded to His30 ND1 atom in all the four subunits of Y34H, two of the four subunits of Y34N, and one of the two subunits of Y34A within the crystallographic asymmetric unit. In the Y34H structure, this additional water molecule also forms a hydrogen bond to the His34 NE2 atom. Such additional water molecules have been often observed in cases of replacements by amino acids of smaller volume in human MnSOD (35, 46, 48, 49).

The mutation of Tyr34 to non-polar Val (Y34V MnSOD) differs from the other mutant structures by disrupting the hydrogen-bond relay observed in the crystal structure of the wild-type enzyme (Figure 1D). This disruption of the hydrogen-bond relay is however similar to some other active-site mutations of human MnSOD (33, 48, 50). In Y34V MnSOD, the hydrogen bond to Gln143 NE2 by the additional water molecule is maintained, but in both structures in the asymmetric unit this water molecule is observed to form a hydrogen bond to a water molecule on the edge of the active site cavity instead of the His30 ND1 (Figure 1D). An additional water was not observed in the crystal structure of Y34F MnSOD at 1.9 Å resolution (33); however at a higher resolution of 1.5 Å, such a water molecule was observed in Y34F human MnSOD in which all remaining tyrosine residues were replaced with 3-fluorotyrosine (31).

Catalysis

To examine the effect of Tyr34 mutations on catalysis, we observed the absorbance spectrum of MnSOD and mutants after the generation of superoxide by pulse radiolysis. Data were analyzed in terms of the model of catalysis shown in equations 1–4 (29) and based on pulse radiolysis studies of MnSOD from Bacillus stearothermophilus. The MnSOD catalysis comprises two stages of an oxidation-reduction cycle with proton transfer ultimately from solution to final product H2O2. The redox cycle of catalysis is represented as two irreversible steps, reactions 1, 2, justified in part by the favorable equilibrium constants associated with these processes. Reactions 3 and 4 are the formation and dissociation of an inhibited complex Mn3+(O2 2−)SOD; the structure of this inhibited complex is not known, but data suggest it is a peroxo complex of the metal formed by an oxidative addition of superoxide to Mn2+(H2O)SOD (26). These specific rate constants k1 – k4 were obtained from rates of change of absorbances of MnSOD and superoxide as described earlier (35). The results for Tyr34 mutants reveal the importance of this site for catalysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Kinetic constants of the dismutation of superoxide by MnSOD and mutants.a

| Enzyme | k1 | k2 | k3 | k3' | k4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (nM−1s−1) | (nM−1s−1) | (nM−1s−1) | (s−1) | (s−1) | |

| wild-type | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | -- | 120 |

| Y34A | 0.25 | <0.02 | 0.38 | 1,600 | 330 |

| Y34N | 0.14 | <0.02 | 0.15 | 850 | 200 |

| Y34H | 0.07 | <0.02 | 0.04 | 250 | 61 |

| Y34V | 0.15 | <0.02 | 0.15 | -- | 1000 |

| Y34Fb | 0.55 | <0.02 | 0.46 | -- | 52 |

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Table 2 shows rate constants for reactions of eq 1–eq 4 for five site-specific mutants of human MnSOD studied here including the previously reported Y34F mutant (33, 35). All of the examined Tyr34 mutants show substantial decreases in the second-order rate constants k1 – k3 in the catalytic cycle; however, k2 is decreased to a much larger extent. These constants can be viewed in terms of a gating ratio k2/k3 that determines the flux through the catalytic and inhibition pathways. When this gating ratio is large, the pathway favors catalysis by eq 1 and eq 2, and when the ratio is less than unity the pathway favors formation of the inhibited complex. For human wild-type MnSOD, the gating ratio k2/k3 is near unity, but for the mutants of Table 2 this ratio is considerably less than unity. The rate constants k4 describing the dissociation of the product-inhibited complex were also affected by these replacements (Table 2). They were greater for Y34V, Y34A, and Y34N compared with wild-type MnSOD, and smaller for Y34F and Y34H.

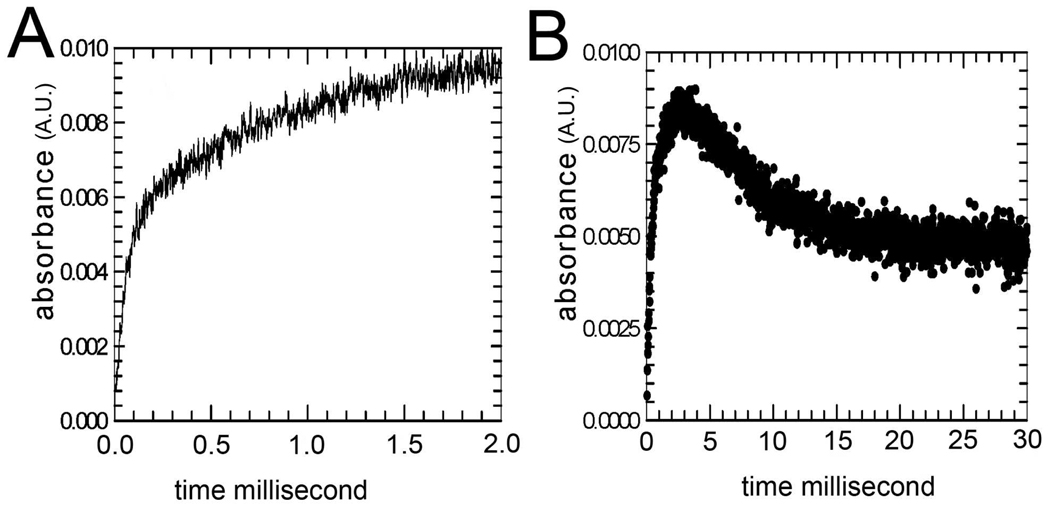

For wild-type Mn2+SOD, and mutants Y34F and Y34V Mn2+ SOD (Table 2), the increase in absorbance at 420 nm following introduction of superoxide by pulse radiolysis can be well fit by a single exponential with rate constant k3 describing the emergence of the product inhibited form (as in eq 3; typical data are presented in Figure S1). This has been the usual observation for many other mutants of human MnSOD studied by pulse radiolysis (35, 36). We report here the new observation that for the mutants Y34A, Y34N, and Y34H there was an intermediate apparent in the catalysis. This is evident in the biphasic increase in the 420 nm absorption measured at times less than 2 ms after generation of O2 •− by pulse radiolysis (Figure 2A). For these mutants (Y34A, Y34N, and Y34H), we observed an increase at 420 nm that is not described by a single exponential but is best fit by the sum of two exponentials with rate constants k3 and k3' given in Table 2. Here k3' represents the formation of an intermediate approaching a maximum at 420 nm that appears fully formed by 2 ms (Figure 2A, B).

Fig 2.

MnSOD activity and the effect of the Y34N mutation. (A) The increase in absorbance (absorbance units) at 420 nm of 120 mM Y34N MnSOD in the 2 ms after pulse radiolysis generated initial superoxide concentrations of 5 mM. (B) The same experiment at longer times. Solutions contained 30 mM formate, 50 µM EDTA, and 2 mM Taps at pH 8.2. The enzyme had been reduced prior to the experiment with 130 mM H2O2. The data are fit to eq 1–eq 4 resulting in the entries to Table 2.

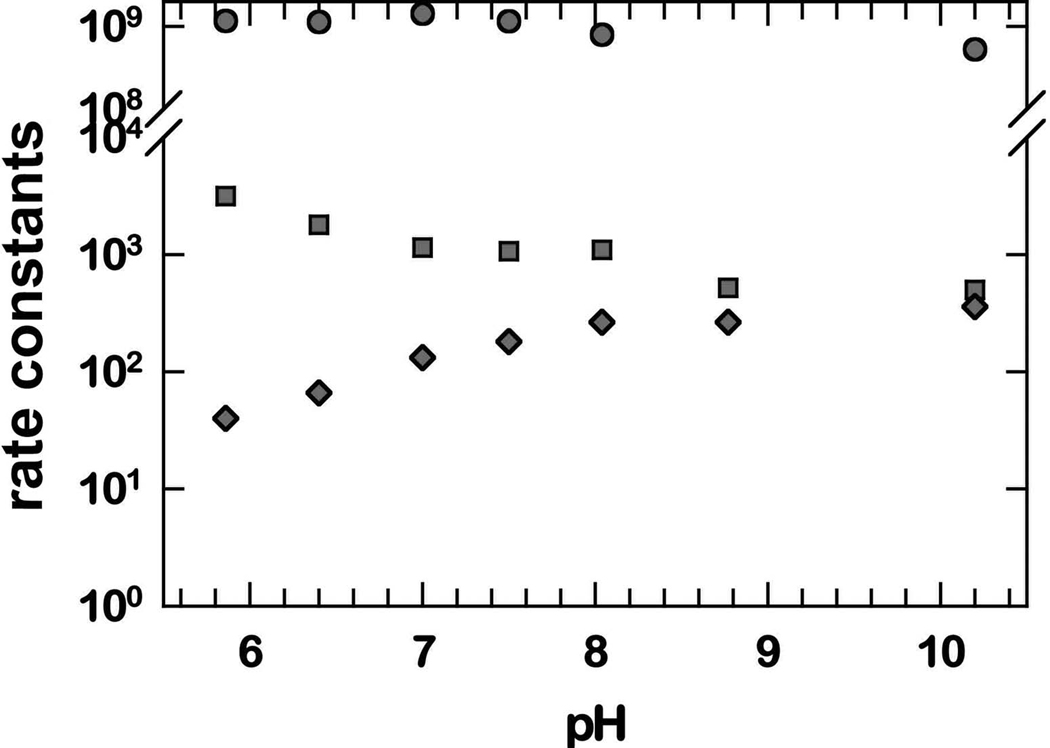

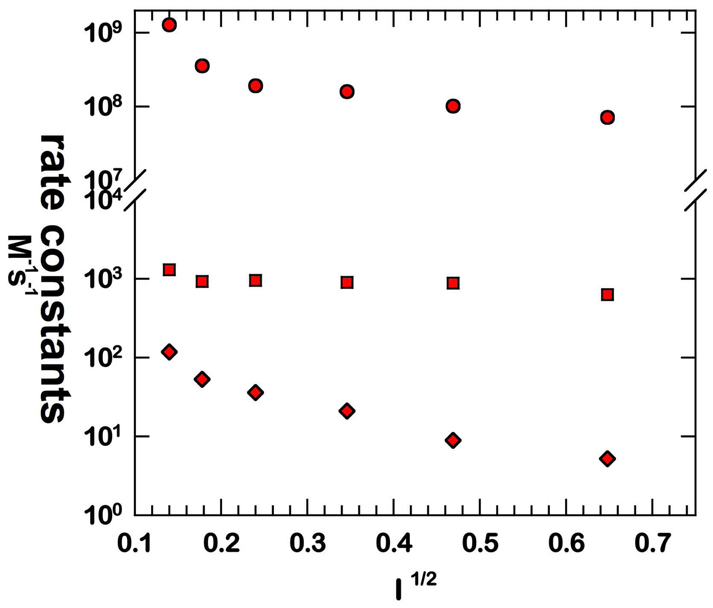

Three well-defined rate constants of the mechanism of eq 1–eq 4 are further investigated for Y34N in the pH and ionic strength profiles of Figure 3 and Figure 4. Here it appears that k1 is independent of pH in the range measured; however, k3' and k4 show a variation below pH 8 that is complex and not fit to a single ionization. One possible explanation for almost no pH dependence in k1 (Figure 3) is that the protons involved emanate from groups with values of pKa outside the pH range of these studies. The variation with ionic strength shows variations of k1 and k4, but most notably the rate constant k3' is independent of changes in ionic strength (Figure 4).

Fig 3.

pH profiles for the rate constants k1 (M−1s−1) (circles); k3' (s−1) (squares); and k4 (s−1) (diamonds) in catalysis by Y34N MnSOD. Experiments used no added NaCl, matching the lowest ionic strength on Figure 4. Experiments were carried out in 10 mM formate, 10 mM phosphate, 25 µM EDTA at 25 °C. The measurements were made at pH 7.0; somewhat lower than the pH used in the other studies.

Fig 4.

Ionic strength (I) profiles for the rate constants k1 (M−1s−1) (circles); k3' (s−1) (squares); and k4 (s−1) (diamonds) in catalysis by Y34N MnSOD. Conditions were as listed in Figure 3 with ionic strength adjusted by addition of NaCl.

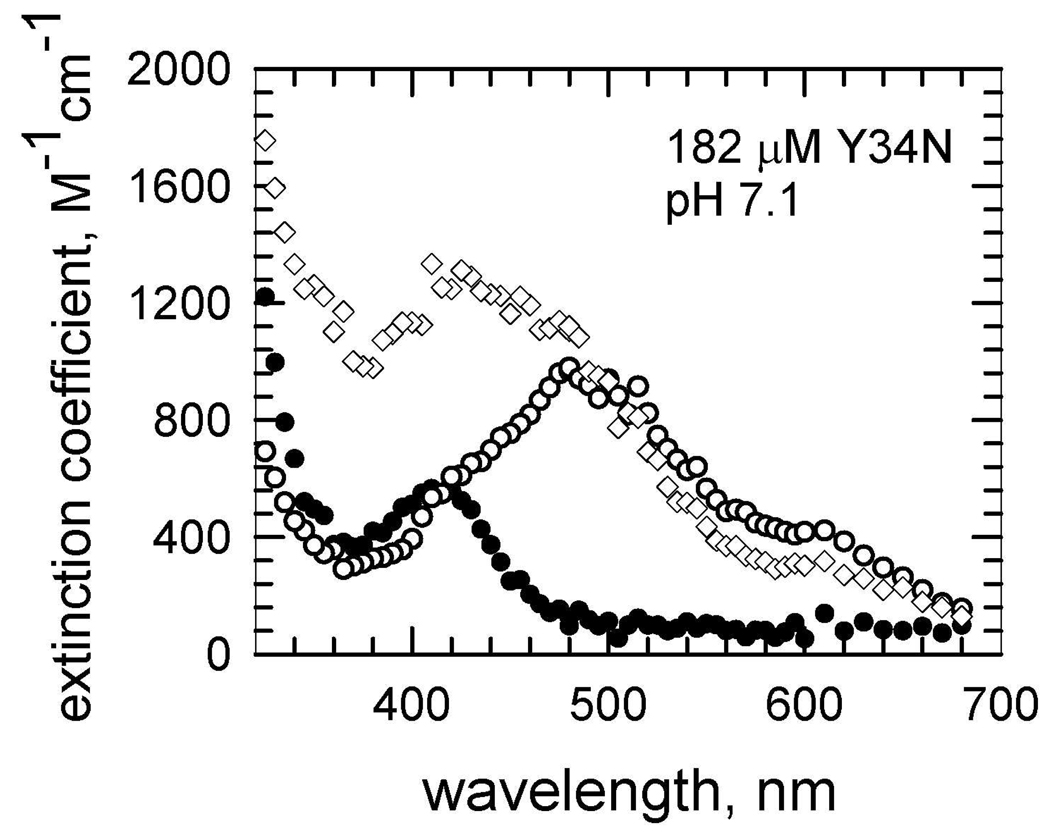

When the data of Figure 2A for Y34N were separated into their two exponential increases and the molar extinction coefficients near 2 ms were plotted as a function of wavelength, the resulting spectrum showed an absorption maximum at 420–440 nm with a molar extinction coefficient near 1300 M−1cm−1 (Figure 5). The maximal absorption of the initial, rapid increase (< 0.2 ms) when plotted as a function of wavelength is the spectrum of the inhibited complex. This has a maximum at 420 nm with a molar extinction coefficient of 600 M−1cm−1 (Figure 5), consistent with previous reports of the product-inhibited complex (26, 46). At long times near 30 ms, the enzyme species equilibrate (Figure 2B) to a maximum at 480 nm and an molar extinction coefficient near 600 M−1cm−1, which is consistent with Mn3+(OH)SOD (26). These plots were similar for the other variants that showed an intermediate, Y34A and Y34H. The plot for Y34A is shown in Figure S2.

Fig 5.

Molar extinction coefficient (M−1cm−1) observed after pulse radiolysis of a solution of Y34N MnSOD (182 µM) at pH 7.1 pre-reduced with H2O2. (Open squares) spectrum of Mn3+(OH)SOD obtained by extrapolating to long times in Figure 2A; (filled diamonds) spectrum of the product-inhibited complex obtained by extrapolating the initial increase (t # 0.2 ms) as in Figure 2A; (open diamonds) spectrum of a newly-detected intermediate obtained by extrapolating the second kinetic process at times near 2 ms as in Figure 2B. Solutions contained 30 mM formate, 50 µM EDTA, and 2 mM Mops.

Discussion

To investigate the function of residue 34 of human MnSOD in catalysis and inhibition, we replaced the highly conserved active-site residue Tyr34 with selected amino acids. Among the Tyr34 variants examined, only wild-type MnSOD maintains the most efficient catalysis (Table 2). Each of the mutants caused a decrease in the rate constants k1 and k2 describing the catalytic cycle, and in k3 which describes the formation of the product-inhibited complex (eq 1–eq 4). However, k2 was more greatly affected with values of rate constants that were too low to measure accurately. This observation helps to explain the increased product inhibition in Y34F MnSOD (33) and other mutants at position 34 compared with wild type; this is due to the much decreased rate constant k2 for the catalytic reduction of O2 •− to hydrogen peroxide, rather than an increased rate through the pathway described by k3 leading directly to the inhibited state.

The large decreases in k2 observed for the mutants of Table 2 are probably not due to changes in midpoint potential at the active site; the redox potential of Y34F MnSOD is not significantly different than that of wild type (51). Rather, k2 likely describes Tyr34 as a source of one of the two protons that is transferred to product H2O2, a scheme that is supported by experimental and computation evidence (28). This explains why, relative to the large decreases in k2, there are decreases of much smaller magnitude in k1 and k3, steps that do not involve rate-contributing proton transfer (46). The enzyme has a fast protonation pathway described by k2 of eq 2, and a slower protonation pathway described by k4. The data suggest that Tyr34 is involved in the fast pathway because k2 is greatly reduced in mutants at this site.

The values of the rate constant for the dissociation of the inhibited complex k4 appeared to be greater for some mutants and smaller for others compared with the wild-type MnSOD (Table 2). This rate constant is dependent on proton transfer as a rate contributing step (46). The mutant with the largest value of k4 is Y34V MnSOD; this is the only mutant of those studied in Table 2 for which no hydrogen-bonded network is observed. Hence, we suggest that the proton transfer involved in k4 does not involve this hydrogen-bonded network. This result is consistent with conclusions made using MnSOD containing 3-fluorotyrosine (31), that Tyr 34 is not involved in proton transfer to the product inhibited complex.

Beside the well-studied, reversible product-inhibited complex, this work shows evidence of a second intermediate formed with rate constant k3' in catalysis by Y34A, Y34N and Y34H that appears in the initial 2 ms of catalysis (Figure 2A). (The first intermediate is the product inhibited complex). By separation of the kinetic data into their individual exponential increases, we have an absorption spectrum of this intermediate showing a maximum at 420–440 nm and a molar extinction coefficient 1300 M−1cm−1 (Figure 5). Since this intermediate is observed in mutants for which Tyr34 is replaced, it is not due to formation of a tyrosine radical, nor are its absorption characteristics consistent with a tryptophan radical.

The variation of selected rate constants with pH in Figure 3 shows that k1 is independent of pH in the range studied. This means that the rapid electron transfer of eq 1 occurs without the influence of nearby ionizable groups such as Tyr34 or His30. Any proton transfer within the steps described by k1 is not influenced by groups having a pKa in the range from 6 to 10. This is not the case for k3' and k4, both of which show a variation with pH below about pH 8. In each case this variation with pH is not fit by a single ionization; that is, the variation of the rate constants depends on the ionization states of enzyme species in a more complex manner. The variation of these rate constants with ionic strength of solution (Figure 4) offers further information. Here k1 and k4 vary with ionic strength, consistent with the mechanism of eq 1 and eq 4 which show changes of electrostatic charge associated with formation of the products O2 and H2O2 in these steps.

However, the rate constant k3' does not vary with ionic strength. This suggests that an isomerization or transition not involving a change in electrostatic charge is involved, such as addition of a solvent molecule to the ligand field of the metal. Perhaps the second intermediate may represent an enzyme species with a solvent molecule as a sixth ligand of the metal. Support for a sixth ligand comes from both the cryo-crystal structure of E. coli MnSOD containing a six-coordinate, distorted-octahedral active site (52) and the six-coordinate manganese active site observed in the azide complex of archeal MnSOD (53). Moreover, one proposed mechanism for MnSOD catalysis is the ‘5-6-5 mechanism’, where in the resting state the metal ion is five-coordinated, while upon anion binding it forms a six-coordinate state (53). The steps associated with k3' may involve two binding sites the first of which represents a binding site not on the metal and the second represents a stable metal-bound species. This could involve for example displacement of a metal-bound peroxy intermediate or displacement of the ligand Asp159. This latter mechanism was suggested for non-heme iron-containing superoxide reductase for which Raman spectroscopy is consistent with a solvent ligand replacing a carboxylate of Glu at the metal accompanied by a blue shift of the visible spectrum from 30 nm to more than 100 nm (depending on the enzyme) with only minor changes in the maximal absorption (54) and (55). These characterized Tyr34 mutants may thus open the door to a variety of experiments to obtain more detailed insights in the MnSOD mechanism. The results and insights presented here furthermore provide a framework for comparative studies on the less studied hexameric NiSOD active site (56) as well as on peroxide interactions in the medically-important Cu,ZnSOD (5) and MnSOD (21).

Supplementary Material

A figure showing rate of change of absorbance upon introduction of superoxide to Y34N and Y34F human MnSOD, and a figure of extinction coefficients at different wavelengths for Y34A human MnSOD. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of the advanced light source, for help in crystallographic data collection.

This work was supported by GM54903 National Institutes of Health grant to D.N.S.

Abbreviations

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- rmsd

root mean squared deviation

- Taps

3-{(tris-[hydroxymethyl]methyl)amino}propanesulfonic acid

- Mops

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

References

- 1.Miller AF. Superoxide dismutases: active sites that save, but a protein that kills. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry JJ, Fan L, Tainer JA. Developing master keys to brain pathology, cancer and aging from the structural biology of proteins controlling reactive oxygen species and DNA repair. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1280–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tainer JA, Getzoff ED, Beem KM, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Determination and analysis of the 2 A-structure of copper, zinc superoxide dismutase. J Mol Biol. 1982;160:181–217. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tainer JA, Getzoff ED, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Structure and mechanism of copper, zinc superoxide dismutase. Nature. 1983;306:284–287. doi: 10.1038/306284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin DS, Didonato M, Barondeau DP, Hura GL, Hitomi C, Berglund JA, Getzoff ED, Cary SC, Tainer JA. Superoxide dismutase from the eukaryotic thermophile Alvinella pompejana: structures, stability, mechanism, and insights into amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1534–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher CL, Cabelli DE, Tainer JA, Hallewell RA, Getzoff ED. The role of arginine 143 in the electrostatics and mechanism of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase: computational and experimental evaluation by mutational analysis. Proteins. 1994;19:24–34. doi: 10.1002/prot.340190105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parge HE, Hallewell RA, Tainer JA. Atomic structures of wild-type and thermostable mutant recombinant human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:6109–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourne Y, Redford SM, Steinman HM, Lepock JR, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED. Novel dimeric interface and electrostatic recognition in bacterial Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12774–12779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiDonato M, Craig L, Huff ME, Thayer MM, Cardoso RM, Kassmann CJ, Lo TP, Bruns CK, Powers ET, Kelly JW, Getzoff ED, Tainer JA. ALS mutants of human superoxide dismutase form fibrous aggregates via framework destabilization. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:601–615. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00889-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardoso RM, Thayer MM, DiDonato M, Lo TP, Bruns CK, Getzoff ED, Tainer JA. Insights into Lou Gehrig's disease from the structure and instability of the A4V mutant of human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:247–256. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng HX, Hentati A, Tainer JA, Iqbal Z, Cayabyab A, Hung WY, Getzoff ED, Hu P, Herzfeldt B, Roos RP, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and structural defects in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Science. 1993;261:1047–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.8351519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts BR, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED, Malencik DA, Anderson SR, Bomben VC, Meyers KR, Karplus PA, Beckman JS. Structural characterization of zinc-deficient human superoxide dismutase and implications for ALS. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:877–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estevez AG, Crow JP, Sampson JB, Reiter C, Zhuang Y, Richardson GJ, Tarpey MM, Barbeito L, Beckman JS. Induction of nitric oxide-dependent apoptosis in motor neurons by zinc-deficient superoxide dismutase. Science. 1999;286:2498–2500. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borgstahl GE, Parge HE, Hickey MJ, Beyer WF, Jr, Hallewell RA, Tainer JA. The structure of human mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase reveals a novel tetrameric interface of two 4-helix bundles. Cell. 1992;71:107–118. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90270-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borgstahl GE, Parge HE, Hickey MJ, Johnson MJ, Boissinot M, Hallewell RA, Lepock JR, Cabelli DE, Tainer JA. Human mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase polymorphic variant Ile58Thr reduces activity by destabilizing the tetrameric interface. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4287–4297. doi: 10.1021/bi951892w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arsova-Sarafinovska Z, Matevska N, Petrovski D, Banev S, Dzikova S, Georgiev V, Sikole A, Sayal A, Aydin A, Suturkova L, Dimovski AJ. Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) genetic polymorphism is associated with risk of early-onset prostate cancer. Cell Biochem Funct. 2008;26:771–777. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakanishi S, Yamane K, Ohishi W, Nakashima R, Yoneda M, Nojima H, Watanabe H, Kohno N. Manganese superoxide dismutase Ala16Val polymorphism is associated with the development of type 2 diabetes in Japanese-Americans. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;81:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bica CG, de Moura da Silva LL, Toscani NV, da Cruz IB, Sa G, Graudenz MS, Zettler CG. MnSOD Gene Polymorphism Association with Steroid-Dependent Cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2008 June; doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9064-6. Epub 14th. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang D, Lee KM, Park SK, Berndt SI, Peters U, Reding D, Chatterjee N, Welch R, Chanock S, Huang WY, Hayes RB. Functional variant of manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2 V16A) polymorphism is associated with prostate cancer risk in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1581–1586. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tugcu V, Ozbek E, Aras B, Arisan S, Caskurlu T, Tasci AI. Manganese superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) gene polymorphisms in urolithiasis. Urol Res. 2007;35:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s00240-007-0103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Huang TT, Carlson EJ, Melov S, Ursell PC, Olson JL, Noble LJ, Yoshimura MP, Berger C, Chan PH, Wallace DC, Epstein CJ. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nature genetics. 1995;11:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallewell RA, Laria I, Tabrizi A, Carlin G, Getzoff ED, Tainer JA, Cousens LS, Mullenbach GT. Genetically engineered polymers of human CuZn superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry and serum half-lives. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5260–5268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han WG, Lovell T, Noodleman L. Coupled redox potentials in manganese and iron superoxide dismutases from reaction kinetics and density functional/electrostatics calculations. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:205–218. doi: 10.1021/ic010355z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller AF, Padmakumar K, Sorkin DL, Karapetian A, Vance CK. Proton-coupled electron transfer in Fe-superoxide dismutase and Mn-superoxide dismutase. J Inorg Biochem. 2003;93:71–83. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maliekal J, Karapetian A, Vance C, Yikilmaz E, Wu Q, Jackson T, Brunold TC, Spiro TG, Miller AF. Comparison and contrasts between the active site PKs of Mn-superoxide dismutase and those of Fe-superoxide dismutase. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:15064–15075. doi: 10.1021/ja027319z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bull CN, E C, Yoshida T, Fee JA. Kinetic-Studies of Superoxide Dismutases: Properties of the Manganese-Containing Protein from Thermus-Thermophilus. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4069–4076. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fridovich I. Biological effects of the superoxide radical. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;247:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson TA, Karapetian A, Miller AF, Brunold TC. Probing the geometric and electronic structures of the low-temperature azide adduct and the product-inhibited form of oxidized manganese superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1504–1520. doi: 10.1021/bi048639t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McAdam ME, Fox RA, Lavelle F, Fielden EM. A pulse-radiolysis study of the manganese-containing superoxide dismutase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. A kinetic model for the enzyme action. Biochem J. 1977;165:71–79. doi: 10.1042/bj1650071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wintjens R, Noel C, May AC, Gerbod D, Dufernez F, Capron M, Viscogliosi E, Rooman M. Specificity and phenetic relationships of iron- and manganese-containing superoxide dismutases on the basis of structure and sequence comparisons. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9248–9254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayala I, Perry JJ, Szczepanski J, Tainer JA, Vala MT, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Hydrogen bonding in human manganese superoxide dismutase containing 3-fluorotyrosine. Biophys J. 2005;89:4171–4179. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.060616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quint P, Reutzel R, Mikulski R, McKenna R, Silverman DN. Crystal structure of nitrated human manganese superoxide dismutase: mechanism of inactivation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guan Y, Hickey MJ, Borgstahl GE, Hallewell RA, Lepock JR, O'Connor D, Hsieh Y, Nick HS, Silverman DN, Tainer JA. Crystal structure of Y34F mutant human mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase and the functional role of tyrosine 34. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4722–4730. doi: 10.1021/bi972394l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whittaker MM, Whittaker JW. Mutagenesis of a proton linkage pathway in Escherichia coli manganese superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8923–8931. doi: 10.1021/bi9704212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenleaf WB, Perry JJ, Hearn AS, Cabelli DE, Lepock JR, Stroupe ME, Tainer JA, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Role of hydrogen bonding in the active site of human manganese superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7038–7045. doi: 10.1021/bi049888k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hearn AS, Fan L, Lepock JR, Luba JP, Greenleaf WB, Cabelli DE, Tainer JA, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Amino acid substitution at the dimeric interface of human manganese superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5861–5866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards RA, Whittaker MM, Whittaker JW, Baker EN, Jameson GB. Outer sphere mutations perturb metal reactivity in manganese superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15–27. doi: 10.1021/bi0018943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsu JL, Hsieh Y, Tu C, O'Connor D, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Catalytic properties of human manganese superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17687–17691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren XT, Chingkuang, Bhatt, Deepa, Perry J, Jefferson P, Tainer, John A, Cabelli, Diane E, Silverman, David N. Kinetic and structural characterization of human manganese superoxide dismutase containing 3-fluorotyrosines. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2005;790:168–173. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otwinowski ZaM, W . Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. In: Carter CW Jr, Sweet RM, editors. Methods Enzymol. New York: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McRee DE. XtalView/Xfit--A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J Struct Biol. 1999;125:156–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheldrick GM. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr A. 2008;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarz HA. Free radicals generated by radiolysis of aqueous solutions. J Chem Educ. 1981;58:101–105. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rabani JaN, S O. Absorption spectrum and decay kinetics of O2- and HO2 in aqueous solutions by pulse radiolysis. J Phys Chem. 1969;73:3736–3744. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hearn AS, Stroupe ME, Cabelli DE, Lepock JR, Tainer JA, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Kinetic analysis of product inhibition in human manganese superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12051–12058. doi: 10.1021/bi011047f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cabelli DE, Guan Y, Leveque V, Hearn AS, Tainer JA, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Role of tryptophan 161 in catalysis by human manganese superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11686–11692. doi: 10.1021/bi9909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leveque VJ, Stroupe ME, Lepock JR, Cabelli DE, Tainer JA, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Multiple replacements of glutamine 143 in human manganese superoxide dismutase: effects on structure, stability, and catalysis. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7131–7137. doi: 10.1021/bi9929958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsieh Y, Guan Y, Tu C, Bratt PJ, Angerhofer A, Lepock JR, Hickey MJ, Tainer JA, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Probing the active site of human manganese superoxide dismutase: the role of glutamine 143. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4731–4739. doi: 10.1021/bi972395d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramilo CA, Leveque V, Guan Y, Lepock JR, Tainer JA, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Interrupting the hydrogen bond network at the active site of human manganese superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27711–27716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leveque VJ, Vance CK, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Redox properties of human manganese superoxide dismutase and active-site mutants. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10586–10591. doi: 10.1021/bi010792p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borgstahl GE, Pokross M, Chehab R, Sekher A, Snell EH. Cryo-trapping the six-coordinate, distorted-octahedral active site of manganese superoxide dismutase, J Mol Biol. 2000;296:951–959. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lah MS, Dixon MM, Pattridge KA, Stallings WC, Fee JA, Ludwig ML. Structure-function in Escherichia coli iron superoxide dismutase: comparisons with the manganese enzyme from Thermus thermophilus. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1646–1660. doi: 10.1021/bi00005a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodrigues JV, Abreu IA, Cabelli D, Teixeira M. Superoxide reduction mechanism of Archaeoglobus fulgidus one-iron superoxide reductase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9266–9278. doi: 10.1021/bi052489k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mathe C, Niviere V, Mattioli TA. Fe3+-hydroxide ligation in the superoxide reductase from Desulfoarculus baarsii is associated with pH dependent spectral changes. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16436–16441. doi: 10.1021/ja053808y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barondeau DP, Kassmann CJ, Bruns CK, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED. Nickel superoxide dismutase structure and mechanism. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8038–8047. doi: 10.1021/bi0496081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A figure showing rate of change of absorbance upon introduction of superoxide to Y34N and Y34F human MnSOD, and a figure of extinction coefficients at different wavelengths for Y34A human MnSOD. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org