Abstract

Francisella tularensis and related intracellular pathogens synthesize lipid A molecules that differ from their Escherichia coli counterparts. Although a functional orthologue of lpxK, the gene encoding the lipid A 4′-kinase, is present in Francisella, no 4′-phosphate moiety is attached to Francisella lipid A. We now demonstrate that a membrane-bound phosphatase present in Francisella novicida U112 selectively removes the 4′-phosphate residue from tetra- and pentaacylated lipid A molecules. A clone that expresses the F. novicida 4′-phosphatase was identified by assaying lysates of E. coli colonies, harboring members of an F. novicida genomic DNA library, for 4′-phosphatase activity. Sequencing of a 2.5-kb F. novicida DNA insert from an active clone located the structural gene for the 4′-phosphatase, designated lpxF. It encodes a protein of 222 amino acid residues with six predicted membrane-spanning segments. Rhizobium leguminosarum and Rhizobium etli contain functional lpxF orthologues, consistent with their lipid A structures. When F. novicida LpxF is expressed in an E. coli LpxM mutant, a strain that synthesizes pentaacylated lipid A, over 90% of the lipid A molecules are dephosphorylated at the 4′-position. Expression of LpxF in wildtype E. coli has no effect, because wild-type hexaacylated lipid A is not a substrate. However, newly synthesized lipid A is not dephosphorylated in LpxM mutants by LpxF when the MsbA flippase is inactivated, indicating that LpxF faces the outer surface of the inner membrane. The availability of the lpxF gene will facilitate re-engineering lipid A structures in diverse bacteria.

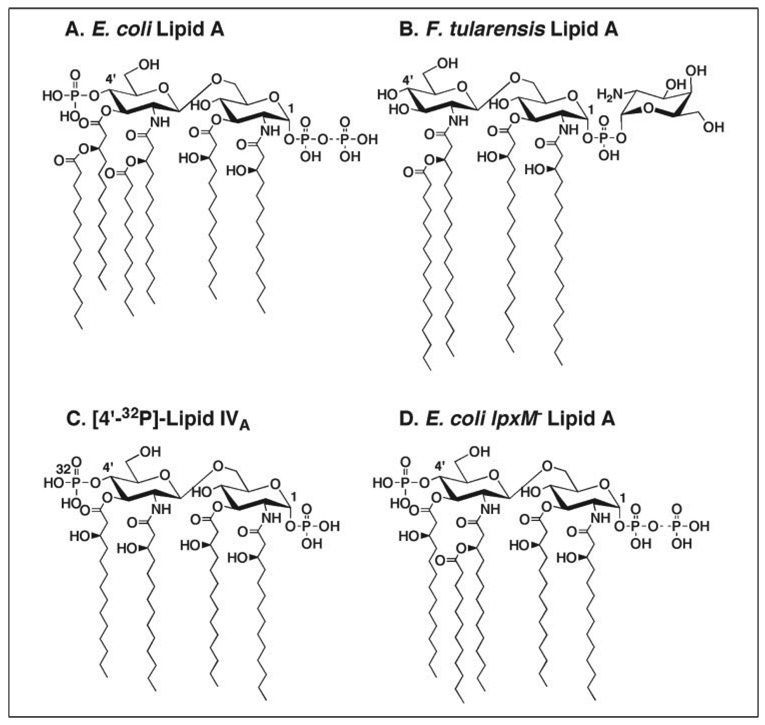

Francisella tularensis is an intracellular Gram-negative pathogen that causes tularemia, a severe and often fatal pulmonary infection of humans and animals (1, 2). Francisella novicida U112 is an environmental isolate that is relatively easy to grow and is much less virulent (3). It is a model system for studying F. tularensis biochemistry. The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 2 of F. tularensis and F. novicida shows low toxicity when compared with Escherichia coli LPS (4, 5). This phenomenon may be due to the unusual structure of the lipid A moiety of Francisella LPS (Fig. 1), which is tetraacylated and lacks the 4′-phosphate residue (6, 7). In contrast, E. coli lipid A (Fig. 1) is hexaacylated and is phosphorylated at both the 1- and 4′-positions (8, 9). E. coli lipid A is a potent activator of toll-like receptor 4 of the mammalian innate immune system (10, 11). The phosphate groups of lipid A are crucial for this bioactivity (12, 13). Lipid A variants lacking both phosphate groups are inactive. Mono-phosphorylated lipid A analogues retain some of the immunostimulatory properties of native lipid A, but they are not toxic and are often used as adjuvants (14–17).

FIGURE 1. Structures of lipid A molecules from E. coli and F. tularensis.

A, the major lipid A molecular species of E. coli is a hexaacylated disaccharide of glucosamine, substituted with monophosphate groups at the 1- and 4′-positions. About one-third of the molecules contain a diphosphate residue at position 1, as indicated by the dashed line (9, 69). B, the lipid A of F. tularensis 1547–1557 is a tetraacylated disaccharide of glucosamine, substituted with a galactosamine phosphate unit at the 1-position (7), which is similar to the more common 4-amino-4- deoxy-l-arabinose present in polymyxin-resistant strains (35, 70). C, the E. coli precursor [4′-32P]lipid IVA was used to assay the 4′-phosphatase (18). D, pentaacylated lipid A is made by the LpxM mutant MLK1067 (30).

Although they possess an orthologue of LpxK, the kinase that incorporates the lipid A 4′-phosphate group (18, 19), F. tularensis and related organisms synthesize lipid A molecules lacking the 4′-phosphatemoiety (6, 7). Similar phosphate-deficient lipid A variants have been reported in the plant endosymbionts Rhizobium etli and Rhizobium leguminosarum (20– 22). A specific lipid A 4′-phosphatase is present in the membranes of these organisms (23–25), but the structural gene encoding the 4′-phosphatase has not been identified.

We have recently cloned an inner membrane phosphatase, designated LpxE, from F. novicida (26) that selectively removes the 1-phosphate group of lipid A. We now report the expression cloning of a distinct F. novicida 4′-phosphatase by assaying members of an F. novicida U112 genomic DNA library (26) harbored in E. coli. Because E. coli does not contain an endogenous 4′-phosphatase (23), pools of five extracts were prepared from individual clones of the library and assayed for 4′-phosphatase activity. A single colony (XW4/pXYW4), expressing high levels of 4′-phosphatase, was identified and characterized. Sequencing of a 2.5-kb F. novicida DNA insert present in pXYW4 revealed the structural gene (lpxF) for the 4′-phosphatase. The sequence of LpxF, a protein of 222 amino acids, is not closely related to that of LpxE (26–28), but both enzymes contain six predicted transmembrane segments and share two of the three catalytic motifs found in many other lipid phosphate phosphatases (29). The lpxF gene was over-expressed in E. coli to produce large amounts of catalytically active enzyme. LpxF dephosphorylates the 4′-position of penta- and tetraacylated lipid A species but not of the hexaacylated lipid A normally made by wild-type E. coli. Expression of lpxF in E. coli MLK1067, a strain that synthesizes pentaacylated lipid A because of a mutation in the lpxM gene (30), results in the production of lipid A molecules that are almost completely dephosphorylated at the 4′-position. Unlike lipid A biosynthesis per se, the activity of LpxF is dependent upon the MsbA transporter in living cells (26, 31), indicating that its active site faces the periplasm. The availability of the lpxF gene should facilitate the re-engineering of lipid A structures in diverse Gram-negative bacteria and may prove useful for vaccine development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

[γ-32P]ATP and 32Pi were obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Glass-backed 0.25-mm Silica Gel 60 TLC plates were from Merck. Chloroform, ammonium acetate, and sodium acetate were obtained from EM Science, and pyridine, methanol, and formic acid were from Mallinckrodt. Trypticase soy broth, yeast extract, and tryptone were purchased from Difco. PCR reagents were purchased from Stratagene, and restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs. The Easy-DNA kit was from Invitrogen. The Spin Miniprep and gel extraction kits were from Qiagen. Shrimp alkaline phosphatase was purchased from the U. S. Biochemical Corp. Bicinchoninic (BCA) protein assay reagents (32) were from Pierce. E. coli phospholipids were purchased from Avanti.

Bacterial Growth Conditions and Membrane Preparation

F. novicida U112 was grown at 37 °C in 3% trypticase soy broth supplemented with 0.1% cysteine (33). E. coli strains were grown at 37 or 30 °C in LB broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl) (34) with one of the following antibiotics, as appropriate: ampicillin (100 µg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 µg/ml), and kanamycin (30 µg/ml). Table 1 describes the various bacterial strains and plasmids used.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| U112 | Wild-type F. novicida | Dr. F. Nano, University of Victoria, Canada |

| W3110 | Wild-type E. coli, F−, λ− | E. coli Genetic Stock Center (Yale University) |

| W3110A | W3110 aroA::Tn10 | 31 |

| W3110B | W3110 aroA::Tn10 lpxM:Ωcam | This work |

| WD2 | W3110 aroA::Tn10 msbA2 (A270T) | 31 |

| XW2 | W3110 aroA::Tn10 lpxM::Ωcam msbA2 (A270T) | This work |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac | Stratagene |

| XW4 | XL1-Blue transformed by pXYW4 | This work |

| NovaBlue | E. coli host strain used for expression | Novagen |

| NovaBlue/pET28b | NovaBlue transformed by pET28b | This work |

| NovaBlue/pET28b-LpxF | NovaBlue transformed by pET28b-LpxF | This work |

| MLK1067 | W3110 lpxM::Ωcam | 45, 50 |

| MLK1067/pWSK29 | MLK1067 transformed by pWSK29 | This work |

| MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF | MLK1067 transformed by pWSK29-LpxF | This work |

| XL1-Blue/pWSK29 | XL1-Blue transformed by pWSK29 | This work |

| XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF | XL1-Blue transformed by pWSK29-LpxF | This work |

| W3110B/pWSK29 | W3110B transformed by pWSK29 | This work |

| W3110B/pWSK29-LpxF | W3110B transformed by pWSK29-LpxF | This work |

| XW2/pWSK29 | XW2 transformed by pWSK29 | This work |

| XW2/pWSK29-LpxF | XW2 transformed by pWSK29-LpxF | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | Low copy vector, Tetr Camr | New England Biolabs |

| pXYW4 | pACYC184 with a 2.5-kb insert of F. novicida genomic DNA that includes lpxF | This work |

| pET28b | Expression vector, T7lac promoter, Kanr | Novagen |

| pET28b-LpxF | pET28b harboring lpxF | This work |

| pWSK29 | Low copy vector, Ampr | 42 |

| pWSK29-LpxF | pWSK29 harboring lpxF | This work |

The same procedures were used to prepare membranes from either F. novicida or E. coli. Typically, 100-ml cultures were grown to A600 of 1.0. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C. All subsequent steps were carried out at 4 °C or on ice. The cell pellets were washed with 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, and resuspended in 10 ml of the same buffer. The cells were disrupted by one passage through a French pressure cell at 18,000 p.s.i., and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min. The membranes were collected by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h, washed once by suspension in 10 ml of 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, and then resuspended in the same buffer at a protein concentration of about 5 mg/ml. The cytosol was double-spun. Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard (32).

Preparation of Lipid IVA

The substrate [4′-32P]lipid IVA was generated from [γ-32P]ATP and the tetraacyldisaccharide 1-phosphate using the overexpressed lipid A 4′-kinase present in membranes of E. coli BLR(DE3)/pLysS/pJK2 (18, 25).

Lipid IVA carrier was isolated from a triple mutant of E. coli MKV15, which makes lipid A lacking secondary acyl chains (30). Briefly, the cells were grown, harvested by centrifugation, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline. Glycerophospholipids were extracted with a single-phase Bligh-Dyer mixture. The lipid IVA was recovered from the cell residue by a second Bligh-Dyer extraction following hydrolysis at 100 °C in sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.5, in the presence of 1% SDS (35). The lipid IVA was then purified by chromatography on a DEAE-cellulose column, followed by a C18 reverse phase column, as described previously (36, 37).

Assay for the 4′-Phosphatase of F. novicida

The 4′-phosphatase was assayed at 30 °C. The reaction mixture contains 50mm potassium phosphate, pH 6, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/ml E. coli phospholipids, and 10 µM [4′- 32P]lipid IVA (3000–6000 cpm/nmol). The reaction was terminated by spotting 5-µl samples onto a silica TLC plate. The plate was developed in the solvent of chloroform, pyridine, 88% formic acid, water (50:50:16:5, v/v). After drying and overnight exposure of the plate to a PhosphorImager screen, product formation was detected and quantified with a Storm PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences), equipped with ImageQuant software.

Expression Cloning of the F. novicida 4′-Phosphatase Gene lpxF

Recombinant DNA manipulations were carried out according to standard protocols (38, 39). Genomic DNA was isolated from F. novicida U112 using the Easy DNA kit. Typically, 50 µg of genomic DNA was partially digested with 4 units of SauIIIAI in 200 µl at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction was then incubated at 65 °C for 20 min to inactivate the enzyme. The products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel, and the 2–6-kb DNA fragments were excised and purified using the gel extraction kit. Plasmid pACYC184 was opened with BamHI, purified by gel electrophoresis, and treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The 2–6-kb DNA fragments were then ligated into pACYC184 at 16 °C overnight in a 25-µl reaction mixture, containing 200 ng of genomic DNA fragments, 200 ng of pACYC184 vector, and 2 units of T4 DNA ligase (26). E. coli XL1-Blue cells were transformed by electroporation with the ligation mixture, and chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were selected on LB plates. About 15,000 colonies were pooled using a cell scraper and transferred into 250 ml of fresh LB broth, containing 30 µg/ml chloramphenicol. Cells were grown to saturation, and then 2-ml stocks adjusted to 16% glycerol were prepared and stored at −80 °C.

To screen for the 4′-phosphatase gene, a glycerol stock of the library was diluted to obtain about 200 colonies per LB plate, containing 30 µg/ml chloramphenicol. The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight. The single colonies were inoculated into 6 ml of LB broth and grown overnight. Next, 1-ml portions of the overnight cultures were stored as glycerol stocks. The remaining 5-ml portions of the overnight cultures were pooled into groups of five. Cell-free extracts were then prepared from the pools and assayed for 4′-phosphatase activity. A total of 200 pools was assayed over the course of 3 weeks. The individual clones from one pool (out of a total of two positive pools) with measurable 4′-phosphatase activity were recovered and grown individually to late log phase in 50 ml of LB broth containing 30 µg/ml chloramphenicol. The cell-free extracts of these cultures were again assayed for 4′-phosphatase. Only one positive clone expressing the 4′-phosphatase activity was found and was designated as XW4.

The hybrid plasmid (pXYW4) present in XW4 was isolated using the Qiagen Spin Miniprep kit. Its F. novicida DNA insert was sequenced by using the Terminator Cycle system and an ABI Prism 377 instrument at the Duke University DNA Analysis Facility. Using the program ORF Finder (40), we identified a putative open reading frame in the 2.5-kb insert that is distantly related to members of the nonspecific acid phosphatase family (29), as judged by BLASTp analysis (41). This potential open reading frame contains a 669-bp DNA fragment and starts with TTG. It was amplified by PCR and cloned into the pET28b vector behind the T7lac promoter. The forward primer was 5′-GCGCGCCATGGCAAGATTTCATATCATATTAGGTT-3′. It was designed with a clamp region, an NcoI restriction site (underlined), and a match to the coding strand starting at the putative translation initiation sites. The reverse primer was 5′-GCGCGCCTCGAGTCAATATTCTTTTTTACGATACATTAGTG-3′, which was designed with a clamp region, an XhoI restriction site (underlined), and a match to the anticoding strand including the stop codon. The PCR was performed using Pfu polymerase and plasmid pXYW4 as the template. Amplification was carried out in a 100-µl reaction mixture containing 100 ng of template, 250 ng of primers, and 2 units of Pfu polymerase. The reaction was started at 94 °C for 1 min, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (30 s at 94 °C), annealing (30 s at 55 °C), and extension (45 s at 72 °C). After the 25th cycle, a 10-min extension time was used. The reaction product was analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. The desired band was excised and gelpurified. The PCR product was then digested using NcoI and XhoI and ligated into the expression vector pET28b that had been similarly digested and treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The ligation mixture was transformed into XL1-Blue cells, and the kanamycin-resistant colonies were selected on LB plates. The plasmid pET28b-LpxF was isolated and transformed into NovaBlue cells after the structure of the insert was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Massive overexpression of 4′-phosphatase activity was observed in membranes of NovaBlue/pET28b-LpxF, but not of NovaBlue/pET28b.

To construct pWSK29-LpxF, pET28b-LpxF was digested using XbaI and XhoI, and the insert was ligated into the vector pWSK29 (42) that had been similarly digested and treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The ligation mixture was transformed into XL1-Blue cells, and ampicillin-resistant transformants were selected on LB plates. The plasmid pWSK29-LpxF was isolated from a positive clone and transformed into MLK1067 (lpxM) to obtain MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF. The strains and plasmids constructed in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Isolation of LipidASpecies from 32P-labeled Cells

Typically, 20 ml of LB broth cultures were labeled with 5 µCi/ml 32Pi, starting at an initial A600 of 0.02. The 32P-labeled cells were grown to A600 of 1.0, harvested, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline. The pellets were resuspended in 3 ml of a single-phase Bligh-Dyer mixture (43), incubated at room temperature for 60 min, and centrifuged to collect the pellets. The lipid A is covalently attached to the LPS in the insoluble pellets. To recover the lipid A, the pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of 12.5 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.5, containing 1% SDS, and heated at 100 °C for 30 min (35, 44). The suspension was converted to a two-phase Bligh-Dyer system by the addition of chloroform and water. After thorough mixing, the two phases were separated by centrifugation, and the upper phase was washed once with a fresh pre-equilibrated lower phase. The lower phases were pooled and dried under a stream of nitrogen. The dried lipids were re-dissolved in chloroform and methanol (4:1, v/v). The 32P-labeled lipid A species were spotted onto a TLC plate (10,000 cpm/lane), which was developed in the solvent of chloroform, pyridine, 88% formic acid, water (50:50:16:5, v/v). After drying, the plates were exposed to a PhosphorImager Screen overnight.

To isolate 32P-labeled hexaacylated or pentaacylated lipid A for use as 4′-phosphatase substrates, the plates were exposed to x-ray film to locate the relevant lipid A species. The compounds were scraped off the plates, and the silica chips were extracted with a single-phase Bligh-Dyer mixture for 1 h at room temperature. The suspension was centrifuged. The supernatant was passed through a Pasteur pipette fitted with a small glass wool plug and converted into a two-phase Bligh-Dyer system. The two phases were separated by centrifugation. The lower phase, containing the 32P-labeled lipid A, was dried, and the 32P-labeled lipid A was resuspended in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 6, with sonic irradiation in a bath apparatus and used for the in vitro 4′-phosphatase assay, as described above.

Preparation of 4′-Dephospho-pentaacylated Lipid A and Its 1-DiphosphateDerivative

The 4′-dephospho-pentaacylated lipid A and its 1-diphosphate derivative were isolated from the strain MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF and analyzed by using MALDI/TOF mass spectrometry. The cell pellets from 1 liter were extracted for 1 h at room temperature with a single-phase Bligh-Dyer mixture consisting of chloroform, methanol, and water (1:2:0.8, v/v) and centrifuged. To recover the lipid A, the pellet was resuspended in 50 ml of 12.5 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.5, containing 1% SDS and heated at 100 °C for 30 min (35, 44).The suspension was converted to a two-phase Bligh-Dyer system by the addition of chloroform and methanol. After thorough mixing, the two phases were separated by centrifugation, and the upper phase was washed once with a fresh pre-equilibrated lower phase. The lower phases were pooled and dried under a stream of nitrogen. The lipids were dissolved in chloroform, methanol, and water (2:3:1, v/v) and applied to a 1-ml DEAE-cellulose column (35, 44). The lipid A was eluted in steps with increasing amounts of ammonium acetate. The 4′-dephospho-pentaacylated lipid A was observed in fractions of 30 mm ammonium acetate and its diphosphate derivative in fractions of 90 mm ammonium acetate. Both fractions were pooled and converted to a two-phase Bligh-Dyer system. The lower phase was dried and analyzed by MALDI/TOF mass spectrometry.

MALDI/TOF Mass Spectrometry

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time-of-flight (MALDI/TOF) mass spectra were acquired using an AXIMA-CFR instrument from Kratos Analytical (Manchester, UK) with a nitrogen laser (337 nm), 20-kV extraction voltage, and time-delayed extraction. The samples were prepared for MALDI/TOF analysis by depositing 0.3 µl of the lipid sample, dissolved in chloroform and methanol (4:1, v/v), followed by 0.3 µl of a saturated solution of 6-aza-2-thiothymine in 50% acetonitrile and 10% tribasic ammonium citrate (9:1, v/v) as the matrix. The samples were left to dry at room temperature before the spectra were acquired in both the positive and negative ion linear modes. Each spectrum was the average of 100 laser shots.

Disk Diffusion Tests

Overnight cultures of E. coli XL1-Blue/pWSK29, MLK1067/pWSK29, XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF, and MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxFwere diluted into LB broth to A600 = 0.2. Lawns of each strain were spread onto LB agar plates with a sterile cotton swab. Sterile filter paper disks (6 mm diameter) were placed on top of the bacterial lawns, and 2 µg of polymyxin was spotted onto each disk. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C, and the diameters of the clear zones were measured.

P1vir Transduction of the lpxM Mutation into W3110A and WD2

To study the MsbA dependence of LpxF in living cells, we needed to construct strains that contain both the msbA and the lpxM mutations, because LpxF does not work on hexaacylated lipid A in vivo. Therefore, the lpxM(msbB) mutation from strain MLK1067 (30, 45) was transduced into the MsbA temperature-sensitive mutant WD2 (31). Briefly, cell pellets from 5 ml of overnight cultures of W3110A and WD2, grown at 30 °C, were resuspended in 100 µl of 100 mm MgSO4 and 5 mm CaCl2 and infected with 100 µl of the P1vir lysate of strain MLK1067 for 30 min at 30 °C (34). Next, the cell culture was diluted into 7 ml of LB broth, and 1 m citrate was added to a final concentration of 20 mm. The cells were shaken at 30 °C for 2 h, after which they were harvested and resuspended in 100 µl of LB broth containing 20 mm citrate. The cells were spread onto LB agar plates, containing chloramphenicol and 4 mm citrate, and were incubated at 30 °C for 2 days. Resistant colonies were purified and then were tested for all relevant antibiotic markers and temperature sensitivity. The two desired constructs, W3110B andXW2 (Table 1), were derived from W3110A and WD2, respectively.

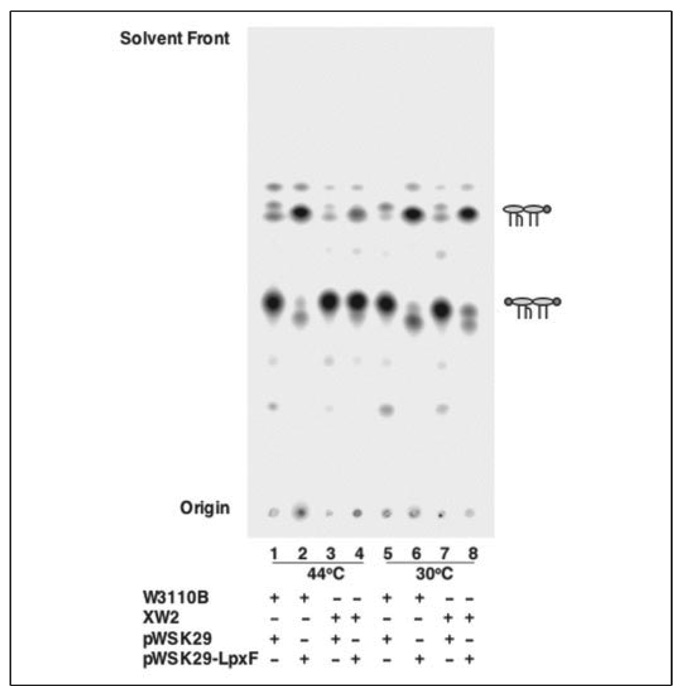

The plasmids pWSK29 and pWSK29-LpxF were transformed into W3110B and XW2 to yield W3110B/pWSK29, W3110B/pWSK29-LpxF, XW2/pWSK29, and XW2/pWSK29-LpxF. All four strains were grown at 30 °C in LB broth, supplemented with 100 µg/ml ampicillin, until A600 reached 1.0. Next, 10-ml portions of each culture were added to 15 ml of fresh LB broth, equilibrated at 30 or 44 °C. The cells were shaken at these temperatures for another 30 min, labeled with ~5 µCi/ml 32Pi for 20 min, and harvested (31). The 32P-labeled lipid A species were recovered from the solvent-extracted cell pellets by pH 4.5 hydrolysis in the presence of SDS (44) and analyzed by TLC.

RESULTS

Lipid A 4′-Phosphatase Activity in F. novicida U112

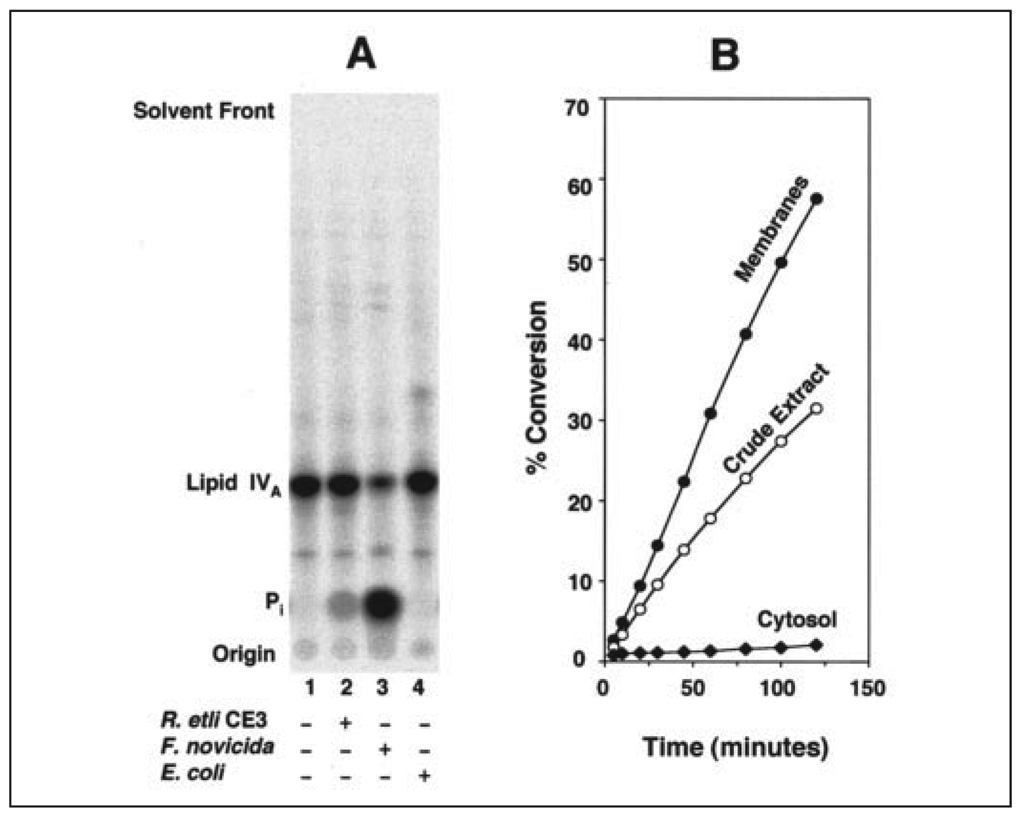

The F. tularensis and F. novicida genomes contain the lpxK gene, which encodes the lipid A 4′-kinase (18). The absence of the 4′-phosphate group in the lipid A molecules made by these organisms (Fig. 1) might be explained by a selective 4′-phosphatase, functioning at a later stage of lipid A assembly. To identify a phosphatase of this kind, F. novicida U112 membranes were assayed with the substrate [4′-32P]lipid IVA (Fig. 1). Rapid release of inorganic phosphate from [4′-32P]lipid IVA was observed with F. novicida but not E. coli membranes (Fig. 2A). R. etli CE3 membranes, which also contain a 4′-phosphatase (23, 25), were assayed in parallel. The 4′-phosphatase activity of F. novicida membranes was much higher than that of CE3, when normalized to protein (Fig. 2A). The F. novicida 4′-phosphatase activity was linear with time and protein concentration (Fig. 2B), and it was absent in the cytosol (Fig. 2B). The enzyme required Triton X-100 and was stabilized by E. coli phospholipids (data not shown). Standard conditions for the quantification of the 4′-phosphatase included 0.1 mg/ml E. coli phospholipids, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 6.0. The 4′-phosphatase specific activity of F. novicida U112 membranes, assayed with 10 µm [4′-32P]lipid IVA as the substrate, was 10.4 nmol/min/mg.

FIGURE 2. A membrane-bound 4′-phosphatase in F. novicida U112.

A, membranes of F. novicida U112,R. etli CE3, or E. coli W3110 (each at 0.2 mg/ml) were assayed at 30 °C for 30 min with 10 µm [4′-32P]lipid IVA as substrate. B, the F. novicida 4′-phosphatase is membrane-bound, as shown by comparison of the 4′-phosphatase activities in crude extract (○, 10 µg/ml), membranes (●,5 µg/ml) or cytosol (♦, 10 µg/ml). The products were separated by TLC with the solvent chloroform, pyridine, 88% formic acid, water (50:50:16:5,v/v) and detected with a PhosphorImager.

Expression Cloning of the 4′-Phosphatase of F. novicida U112

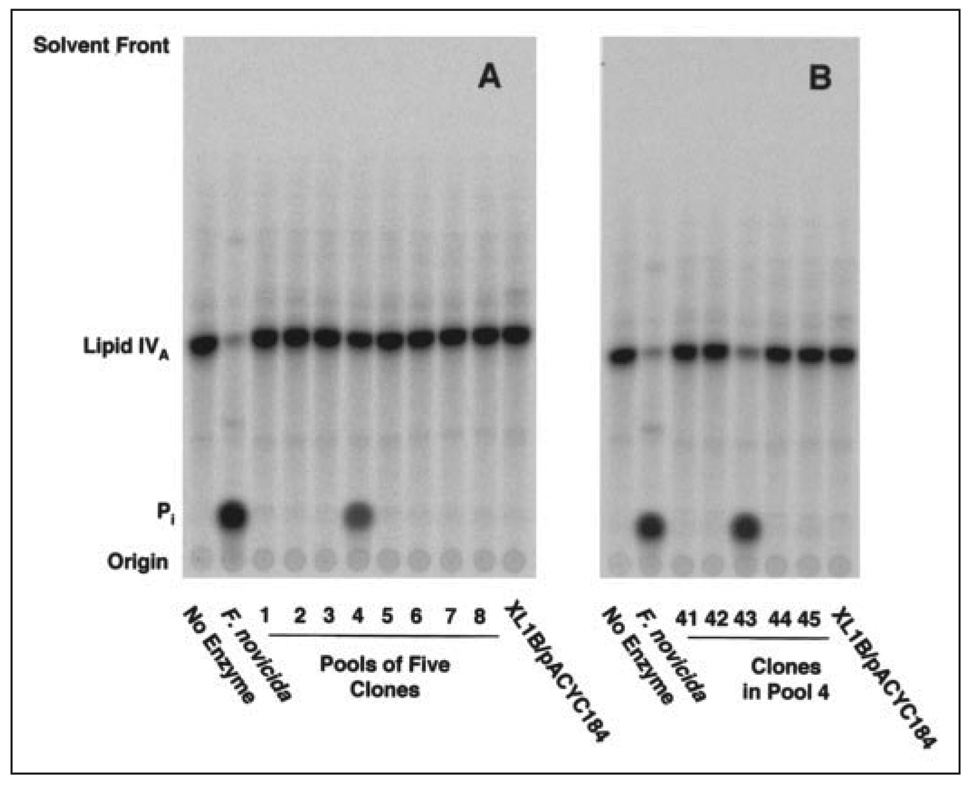

Previous attempts to expression-clone or purify the 4′-phosphatase from R. etli or R. leguminosarum were unsuccessful (25, 46). Rhizobium promoters do not function efficiently in E. coli, and expression-cloning strategies are therefore cumbersome (46). In contrast, efficient expression in E. coli of several F. novicida genes from their native promoters has been reported (26, 47). To identify the structural gene for the F. novicida 4′-phosphatase, a library of F. novicida U112 genomic DNA was constructed in the vector pACYC184 (26) and then transferred into E. coli XL1-Blue. Extracts were prepared from individual colonies of the library, pooled into groups of five, and assayed for 4′-phosphatase activity with [4′-32P]lipid IVA as the substrate. Approximately 200 pools were assayed. An extract of F. novicida U112 was used as the positive control and an extract of E. coli XL1-Blue/pACYC184 as the vector control. The results of a typical screening assay are shown in Fig. 3A. Strong 4′-phosphatase activity was observed in pool 4 but not in the vector control or the other pools. Only one additional pool of the 200 that were screened displayed 4′-phosphatase activity (data not shown). Next, extracts of the five colonies contained in each of the two positive pools were assayed individually, as shown in Fig. 3B for pool 4. Only the extract derived from colony 43 was active. Likewise, only one colony was positive for 4′-phosphatase activity in the second active pool (data not shown). The relevant plasmids were then isolated from the two positive colonies and their inserts sequenced. Both were identical, and therefore only colony 43 (designated XW4), recovered from pool 4, was further characterized. The 4′-phosphatase-specific activity of E. coli XW4 membranes, assayed with 10 µm [4′32P]lipid IVA as substrate, was 2.0 nmol/min/mg.

FIGURE 3. Expression cloning of the F. novicida 4′-phosphatase in E. coli.

A genomic F. novicida U112 DNA library was transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue. A, extracts were prepared from individual clones, pooled into groups of 5, and assayed at 30 °C for 60 min at 1 mg/ml, using [4′-32P]lipid IVA as the substrate. F. novicida U112 extracts were the positive controls and XL1-Blue/pACYC184 the negative controls. The 32Pi and [4′-32P]lipid IVA were separated by TLC, as in Fig. 2. Of the eight pools shown, only pool 4 had significant 4′-phosphatase activity. B, extracts from the five individual clones of pool 4 were re-assayed, showing that only clone 43 (renamed XW4) was active.

Sequencing and Subcloning of F. novicida lpxF

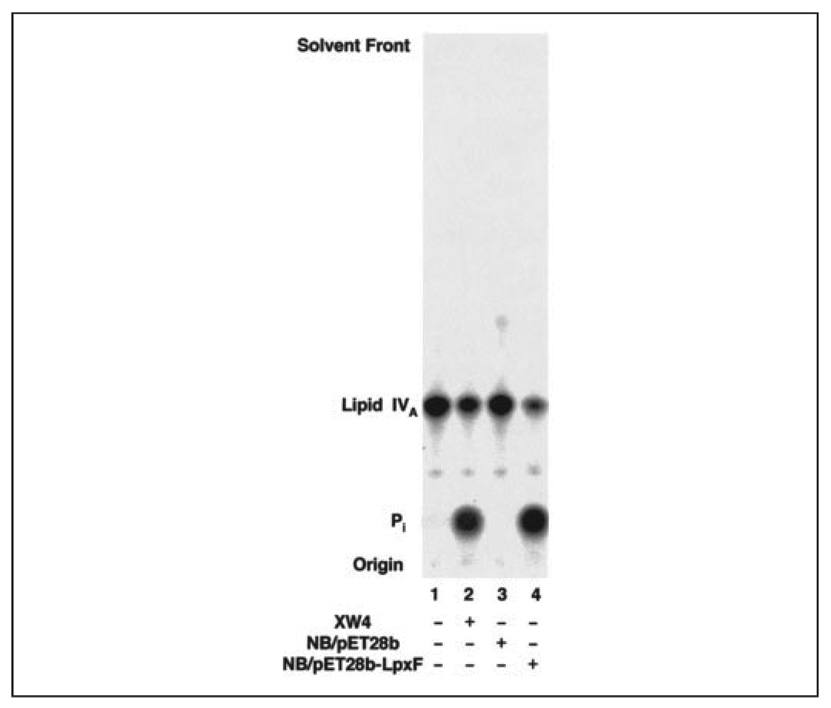

The hybrid plasmid pXYW4, present in XW4, contains a 2.5-kb genomic fragment of F. novicida U112 DNA. Within this insert we found an open reading frame of 669 bp encoding a putative protein of 222 amino acids with distant similarity to the family of nonspecific acid phosphatases (29). This open reading frame was amplified by PCR, ligated into pET28b, and transformed into E. coli NovaBlue to obtain NovaBlue/pET28b-LpxF. Membranes were prepared from isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside-induced cells and assayed for 4′-phosphatase activity with 10 µm [4′-32P]lipid IVA as the substrate. Significant expression of 4′-phosphatase activity was seen with NovaBlue/pET28b-LpxF (Fig. 4, lane 4, specific activity of 12 nmol/min/mg) but not with the vector control (Fig. 4, lane 3). Subcloning of the same 669-bp open reading frame behind the lac promoter in pWSK29 yielded membranes from isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside-induced cells with a 4′-phosphatase-specific activity of 800 nmol/min/mg. The 669-bp DNA insert is therefore the probable 4′-phosphatase structural gene, which we designate lpxF. The LpxF protein displays 99% identity to the unidentified protein FTT1643c of F. tularensis Schu 4 (48), with an E value of ~10−129 (Table 2) in a two-sequence BLASTp comparison (49). The full-length LpxF protein is predicted to have six membrane-spanning segments (Fig. 5).The sequence of F. novicida LpxF has been deposited under GenBank™ accession number DQ364143.

FIGURE 4. LpxF 4′-phosphatase activity expressed in E. coli.

Membranes of the indicated strains (0.2 mg/ml) were assayed for 4′-phosphatase activity at 30 °C for 30 min with 10 µm [4′-32P]lipid IVA and were analyzed as in Fig. 2.

TABLE 2. Orthologs of F. novicida LpxF in other organisms.

Possible orthologs in the NCBI data base as of January 5, 2006, were identified with the PSI-Blast algorithm, using the predicted F. novicida LpxF protein sequence as the probe. The low complexity filter was removed. Homology is given as the number of identities/number of positives/number of residues (including gaps) in the related segment when compared with F. novicida LpxF.

| Organism | Conserved domains | Homology (gaps) | E values |

|---|---|---|---|

| F. tularensis subsp. tularensis | KDHWGRPRP-NCSFVCG-RMSQGGHFFSD | 220/221/222(0) | 1 × 10−129 |

| Nitrosococcus oceani | KNHWDRARP-NCSFVCG-RIAQGAHFMSD | 82/124/220(4) | 6 × 10−36 |

| Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum MS-1 | KDNWGRPRP-NCSFPSG-RIAQGGHFLSD | 75/109/194(10) | 3 × 10−27 |

| Rhodospirillum rubrum | KENWGRARP-NCSFTSG-RIAVGGHFLSD | 71/110/214(9) | 1 × 10−26 |

| Microbulbifer degradans 2–40 | KDNSGRPRP-NCSFVSG-RIIQGGHFLSD | 82/116/216(7) | 2 × 10−26 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 | KSHWGRPRP-NCSFFSG-RMAFGGHFFTD | 70/111/219(2) | 2 × 10−25 |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 | KTYWGRPRP-NCSFFSG-RMAFGGHFFTD | 68/112/222(8) | 1 × 10−24 |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58 | KAMIGRARP-NCSFSSG-RIAAGGHFLSD | 63/107/203(5) | 1 × 10−18 |

| Dechloromonas aromatica RCB | KNHVGRARP-NCSFVSG-RMSTGGHFLSD | 63/104/220(7) | 1 × 10−18 |

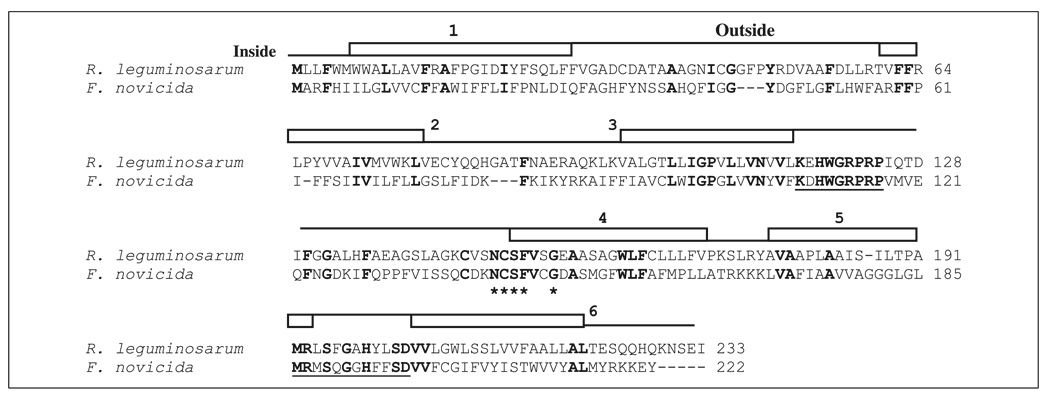

FIGURE 5. Alignment of the LpxF sequences from F. novicida and R. leguminosarum.

Conserved residues are in boldface type. The predicted LpxF proteins share two of the three motifs that are common to the lipid phosphate phosphatase family, which are underlined. However, the NCSFX2G motif, which is indicated with an asterisk, appears to be LpxF-specific. The E value in a two-sequence comparison is only 2 × 10−14. Related LpxF orthologues in other organisms are listed in Table 2. The predicted transmembrane sequences are indicated by rectangles. The hydrophilic sequences, connecting the transmembrane domains, are indicated by lines. The lower lines indicate cytoplasmic loops and the upper lines periplasmic loops. The three conserved LpxF motifs are predicted to lie at or near the periplasmic surface of the inner membranes.

Presence of an Orthologue of LpxF in R. leguminosarum

A possible orthologue of F. novicida LpxF was identified by tBLASTn searching of the R. leguminosarum genome (Fig. 5). The R. leguminosarum protein consists of 233 amino acid residues with six predicted membrane-spanning segments. In a pairwise sequence comparison (49), R. leguminosarum LpxF displays 33% identity and 47% similarity to F. novicida LpxF, with an E value of 2 × 10−14. Both proteins contain motif 1 and most of motif 3 of the three conserved motifs KX6RP, PSGH, and SRX5HX3D that are generally present in members of the nonspecific acid phosphatase family (29). However, motif 2 appears to be replaced with the sequence NCSFX2G in R. leguminosarum and F. novicida LpxF.

When expressed in E. coli, R. leguminosarum lpxF likewise results in the appearance of the 4′-phosphatase activity in cell membranes (data not shown), albeit at a much lower specific activity than with F. novicida lpxF. The LpxF orthologue encoded by the R. leguminosarum genome probably accounts for the fact that R. leguminosarum lipid A lacks the 4′-phosphate moiety (21, 22). Selective inactivation of the lpxF gene will be required to prove that there are no other lipid A 4′-phosphatases in R. leguminosarum or F. novicida. The sequence of R. leguminosarum LpxF has been deposited under GenBank™ accession number DQ364144.

Absence of the Lipid A 4′-Phosphate Group in E. coli lpxM Mutants Expressing lpxF

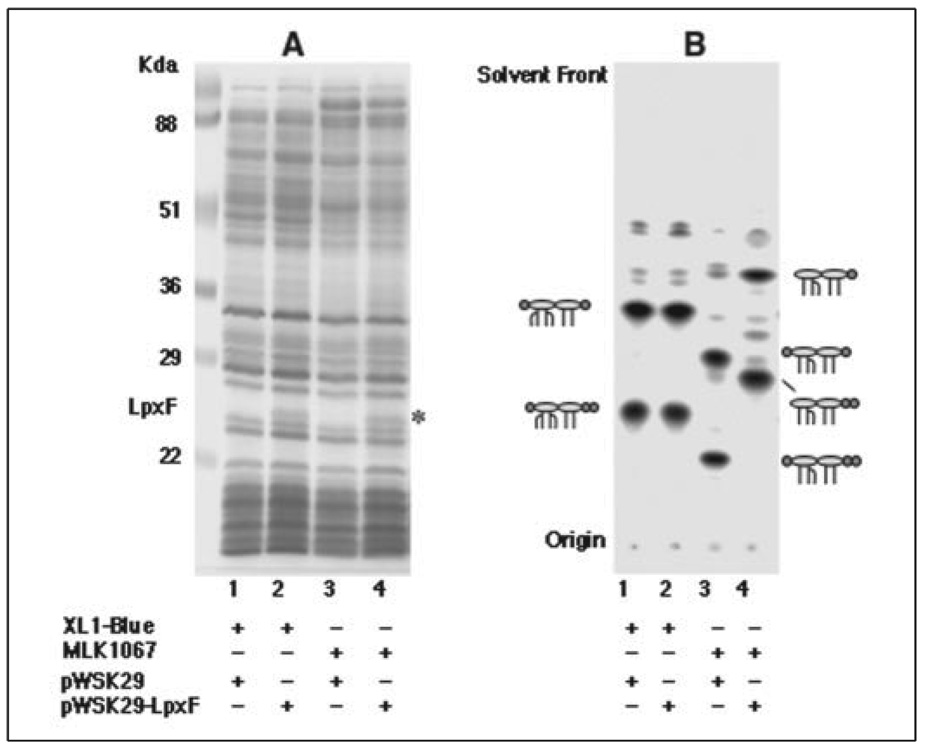

LpxF of F. novicida does not catalyze the dephosphorylation of phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylglycerophosphate, or the 1-phosphate group of lipid A and lipid A precursors. LpxF 4′-dephosphorylates lipid IVA (Fig. 1) and Kdo2-lipid IVA at comparable rates but only at the 4′-position. Most interestingly, LpxF does not utilize hexaacylated lipid A (Fig. 1) or Kdo2-lipid A, the predominant molecular species made by wild-type E. coli K12 (see below). To study its substrate specificity in vivo, LpxF was expressed in E. coli XL1-Blue and MLK1067 (45). The former synthesizes hexaacylated lipid A, like E. coli K12 W3110. The latter makes pentaacylated lipid A because of a mutation in the lpxM(msbB) gene (30), which encodes the 3′ secondary lipid A acyltransferase (50). Membrane proteins from XL1-Blue/pWSK29, MLK1067/pWSK29, XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF, and MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF were separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by staining with Coomassie Blue. When compared with the vector controls (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 and 3), an additional protein was observed in membranes of XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF andMLK1067/pWSK29-LpxFat ~ 25kDa(Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 4), the predicted size for LpxF.

FIGURE 6. Lipid A 4′-dephosphorylation in lpxM mutant MLK1067 expressing LpxF but not in E. coli XL1-Blue.

A, SDS-PAGE was used to analyze 25 µg of membrane protein samples from each of the indicated strains. A band corresponding to the predicted molecular weight of LpxF is visible at ~25 kDa in membranes of cells expressing LpxF. B, uniformly 32P-labeled lipid A species were extracted from the indicated strains and analyzed by TLC, as in Fig. 2. The proposed lipid A structure for each band is indicated schematically. The ovals represent glucosamine residues, the lines the acyl chains, and the circles the phosphate groups. The left circle is the 4′- and right circle is the 1-phosphate group. The structures of E. coli wild-type and lpxM− lipid A species are shown in Fig. 1.

To determine whether or not LpxF dephosphorylates lipid A at the 4′-position in living cells, strains XL1-Blue/pWSK29, XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF, MLK1067/pWSK29, and MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF were labeled with 32Pi for several generations. The 32P-labeled lipid A species were then isolated and separated by TLC. Only the unmodified, wild-type hexaacylated lipid A and its 1-diphosphate derivative were recovered from XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF and the vector control XL1- Blue/pWSK29 (Fig. 6B, lanes 1 and 2), showing that LpxF does not catalyze 4′-dephosphorylation of hexaacylated lipid A in vivo. In contrast, two more rapidly migrating lipid A species accumulated in MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF (Fig. 6B, lane 4), when compared with the vector control MLK1067/pWSK29 (Fig. 6B,lane 3). The Rf values of these lpxF-dependent lipid A species are consistent with 4′-dephosphorylation of the pentaacylated lipid A species made by MLK1067. The 4′-dephosphorylation of lipid A in MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF is nearly complete (>90%).

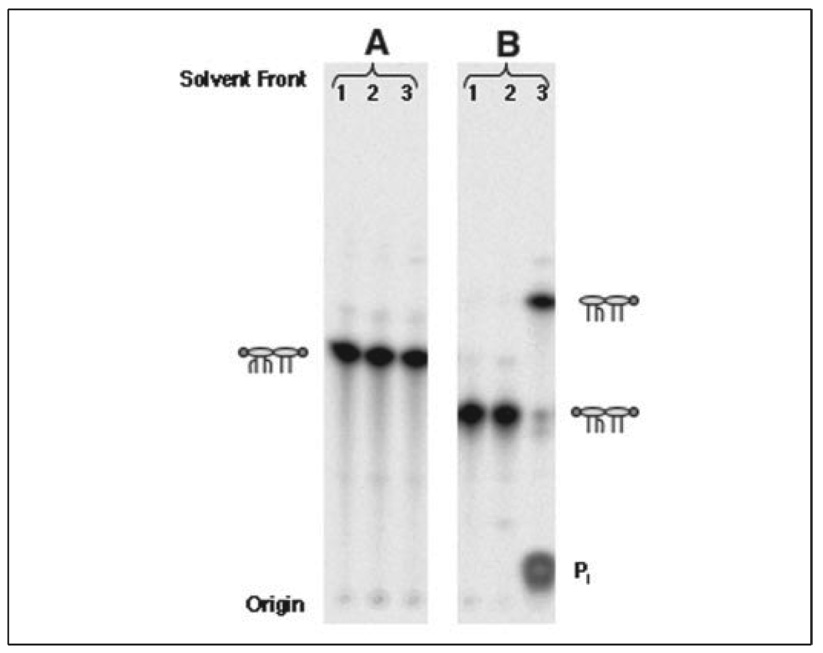

Selectivity of F. novicida LpxF for Pentaacylated Lipid A in Vitro

To confirm the selectivity of LpxF for pentaacylated lipid A under standard in vitro assay conditions, 32P-hexa- and pentaacylated lipid A (labeled at both the 1- and the 4′-positions) were isolated from the appropriate E. coli strains and labeled uniformly with 32Pi. The radioactive lipid A species were purified by preparative TLC. Lipid A dephosphorylation was assayed using membranes of E. coli expressing F. novicida LpxF (Fig. 7). Under matched assay conditions, membranes of XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF did not dephosphorylate hexaacylated lipid A (Fig. 7A, lane 3) but did dephosphorylate pentaacylated lipid A (Fig. 7B, lane 3).

FIGURE 7. Selectivity of LpxF for pentaacylated lipid A in vitro.

Hexaacylated [32P]lipid A or pentaacylated [32P]lipid A were purified from XL1-Blue/pWSK29 or MLK1067/pWSK29 cells, respectively, grown in the presence of 32Pi for several generations. The LpxF assay was performed under standard conditions at 30 °C for 60 min with 0.2 mg/ml membranes from cells expressing LpxF or the vector control. Each reaction mixture loaded on the TLC plate contained 3000 cpm [32P]lipid A. The products were separated by TLC, as in Fig. 2, and detected with a PhosphorImager. Lane 1, no enzyme; lane 2, XL1-Blue/pWSK29; lane 3, XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF. A, hexaacylated [32P]lipid A is the substrate. No reaction is observed. B, pentaacylated [32P]lipid A is the substrate. Given that both the 1- and 4′-positions are labeled with 32P in these substrates, both the 4′-dephosphorylated lipid product and the released inorganic phosphate are detected. The schematic lipid A structures are as described in Fig. 6.

Mass Spectrometry of 4′-Dephosphorylated Lipid A from MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF

The apparent accumulation of 4′-dephosphorylated lipid A and its 1-diphosphate derivative in MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF (Fig. 6) was confirmed by mass spectrometry (supplemental Fig. 1). Lipid A species were isolated from 1 liter of late log phase cells and separated from contaminating phospholipids on a DEAE-cellulose column. The 4′-dephosphorylated lipid A molecules bearing the 1-phosphate group (supplemental Fig. 2A) eluted with 30mm ammonium acetate in the aqueous component, whereas the 4′-dephosphorylated lipid A variant bearing the 1-diphosphate substitution (supplemental Fig. 2C) emerged with 90 mm ammonium acetate.

Supplemental Fig. 1A shows the negative ion MALDI/TOF mass spectrum of the lipid A that elutes in the 30 mm fraction. The predominant peak at m/z 1507.8 is interpreted as the molecular ion [M − H]− of a 4′-dephosphorylated, pentaacylated lipid A (supplemental Fig. 2A), which is the major species expected for MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF. The peak at m/z 1281.4 is derived from the parent ion at m/z 1507.8 by neutral loss of a hydroxymyristoyl moiety. The peak at m/z 1746.1 arises from a distinct lipid A molecule bearing an additional palmitoyl chain, likely generated in MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF by the outer membrane palmitoyltransferase PagP (supplemental Fig. 2B) (51).

The negative ion MALDI/TOF spectrum of the 90 mm ammonium acetate fraction is shown in supplemental Fig. 1B. The predominant peak at m/z 1587.8 is consistent with the parent ion of a 4′-dephosphorylated, pentaacylated lipid A variant, containing the 1-diphosphate modification (supplemental Fig. 2C). The ion at m/z 1361.4 is derived from the parent ion by neutral loss of a hydroxymyristoyl group. The smaller peaks at m/z 1507.9 and 1281.4 likely arise from small amounts of contaminating 4′-dephosphorylated pentaacylated lipid A, carried over from the 30 mm ammonium acetate elution step.

The lipid A molecules present in the 30 and 90 mm ammonium acetate fractions were also analyzed in the positive ion mode (supplemental Fig. 1, C and D). In the 30mm fraction, sodium ion adducts of the parent compounds [M+Na]+ of the 4′-dephosphorylated, pentaacylated lipid A (supplemental Fig. 2A) and its PagP derivative (supplemental Fig. 2B) were observed at m/z 1530.9 and 1769.1, respectively (supplemental Fig. 1C). The smaller peak at m/z 1553.0 is interpreted as the adduct ion [M − H+2Na]+. The ion at m/z 797.3 and the ion at m/z 1411.0 (supplemental Fig. 1C) confirm that the lipid A species eluting with 30 mm ammonium acetate are 4′-dephosphorylated (supplemental Fig. 2, A and B).

Supplemental Fig. 1D shows the positive ion spectrum of the lipid A species eluting with 90 mm ammonium acetate, the putative 4′-dephosphorylated, pentaacylated lipid A variant, bearing the 1-diphosphate moiety (supplemental Fig. 2C). The peak at m/z 1610.9 (supplemental Fig. 1D) is interpreted as [M + Na]+ (supplemental Fig. 2C), whereas the peak at m/z 1632.9 (supplemental Fig. 1D) arises from the adduct ion [M − H + 2Na]+ (supplemental Fig. 2C). The ion at m/z 797.3 and the ion at m/z 1411.1 (supplemental Fig. 1D) are essentially the same as in supplemental Fig. 1C, confirming that the 1-diphosphate variant (supplemental Fig. 2C) lacks a 4′-phosphate group. The smaller peak at m/z 1433.1 arises from the adduct ion [B2 − H + Na]+, and the ion at m/z 1530.9 is because of carryover of lipid A species from the 30 mm ammonium acetate fraction.

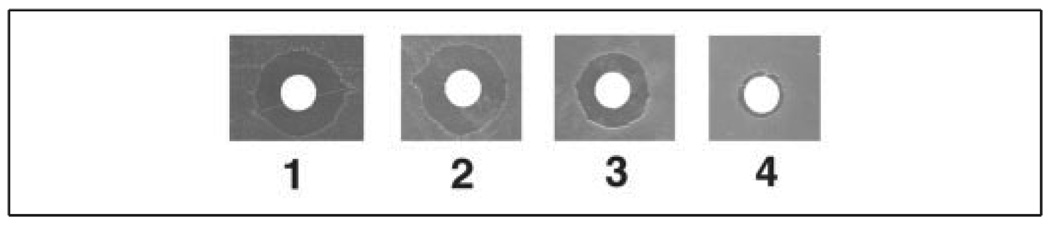

Dephosphorylation of Lipid A by LpxF in MLK1067 Confers Resistance to Polymyxin

In E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium addition of 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose and phosphoethanolamine to the 4′-phosphate group of lipid A confers resistance to polymyxin and various cationic antimicrobial peptides (9, 52). This resistance is probably because of the reduction of the net negative charge of the lipid A, preventing these substances from penetrating the outer membrane. The 4′-dephosphorylation of lipid A by LpxF also reduces the negative charge of lipid A. Consequently, E. coli MLK1067, expressing LpxF, might be more resistant to polymyxin than MLK1067 harboring the vector control. To test this idea, XL1-Blue/pWSK29, XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF, MLK1067/pWSK29, and MLK1067/ pWSK29-LpxF (Fig. 8) were evaluated with an antibiotic disk diffusion assay. Only MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF displayed resistance to polymyxin versus its matched vector control, consistent with the fact that LpxF dephosphorylates the 4′-position of the pentaacylated lipid A in MLK1067 but not of the hexaacylated lipid A in XL1-Blue (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 8. Disk diffusion assays of E. coli strains expressing LpxF.

Panel 1, XL1-Blue/pWSK29; panel 2, XL1-Blue/pWSK29-LpxF; panel 3, MLK1067/pWSK29; and panel 4, MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF. As described under “ Experimental Procedures,” 2 µg of polymyxin was applied to each disk. The polymyxin resistance seen in MLK1067/pWSK29-LpxF is consistent with the 4′-dephosphorylation of its lipid A.

LpxF Activity in Cells Is Dependent Upon a Functional msbA Gene

To determine whether or not the active site of LpxF faces the periplasmic surface of the inner membrane, a derivative of WD2 (aroA::Tn10 msbA2) (31) that harbors an inactivated lpxM gene was constructed by P1vir transduction (Table 1). This strain, designated XW2, synthesizes pentaacylated lipid A, bearing 1- and 4′-phosphate groups, at both 44 and 30 °C, as shown by pulse labeling with 32Pi (Fig. 9, lanes 3 and 7, respectively). The isogenic control strain W3110B, which is wild-type with respect to MsbA, synthesizes the same pentaacylated lipid A at both temperatures (Fig. 9, lanes 1 and 5). When expressing the 4′-phosphatase from pWSK29-LpxF, W3110B synthesizes mostly 4′-dephosphorylated lipid A species at 44 and 30 °C (Fig. 9, lanes 2 and 6). In contrast, when expressing the 4′-phosphatase from pWSK29-LpxF, XW2 does not 4′-dephosphorylate newly synthesized lipid A efficiently at 44 °C, following the inactivation of MsbA, although it does so efficiently at the permissive temperature of 30 °C (Fig. 9, lanes 4 and 8, respectively). The MsbA dependence of lipid A 4′-dephosphorylation in living cells provides very strong evidence that the active site of the 4′-phosphatase faces the outer surface of the inner membrane, as demonstrated previously for the 1-phosphatase, LpxE (26).

FIGURE 9. Lipid A 4′-dephosphorylation by LpxF is MsbA-dependent in vivo.

LpxF expressed in the temperature-sensitive MsbA mutant XW2, which also lacks LpxM, cannot dephosphorylate newly synthesized lipid A at 44 °C. Lipid A species were labeled for 20 min with 32Pi, following MsbA inactivation at 44 °C for 30 min, inhibiting lipid A 4′-dephosphorylation (lane 4 versus lane 8). W3110B is an isogenic lpxM mutant strain that harbors the wild-type msbA allele. The schematic structures are described in Fig. 6.

DISCUSSION

ManyGram-negative bacteria, including strains of Francisella (6, 7), Rhizobium (20–22), Leptospira (53), and Helicobacter (28, 54), synthesize lipid A molecules lacking one or both of the characteristic phosphate substituents present in E. coli or Samonella lipid A Fig. 1 (9). Absence of phosphate groups is expected to attenuate the potency of lipid A as an activator of innate immunity (13, 17) and to confer resistance to cationic anti-microbial peptides (27). All organisms with phosphate-deficient lipid A molecules nevertheless contain the enzymes that synthesize phosphorylated lipid A precursors, such as lipid IVA (Fig. 1) and Kdo2-lipid IVA, as first demonstrated with membranes of R. leguminosarum and R. etli (55), and later confirmed by genome sequencing. These observations indicated that selective lipid A phosphatases must exist in some bacteria, presumably functioning at a later stage of lipid A assembly (23, 24).

We have demonstrated previously the presence of distinct lipid A 1- and 4′-phosphatases in the membranes of R. leguminosarum (23, 24) and F. novicida (26). The lipid A 1-phosphatase of both organisms has been expression-cloned and characterized (26, 27). Heterologous expression in E. coli and Salmonella causes nearly complete 1-dephosphorylation of lipid A (26). The activity of the 1-phosphatase in living E. coli cells is dependent upon the proper functioning of the ABC transporter MsbA, the inner membrane flippase for LPS (26). The active site of the 1-phosphatase must therefore face the periplasmic surface of the inner membrane. When assayed in vitro in the presence of a nonionic detergent, however, the 1-phosphatase is not MsbA-dependent (26). It also does not dephosphorylate the lipid A 4′-position or unrelated glycerophospholipids (26, 27).

We have now expression-cloned the first example of a lipid A 4′-phosphatase. Like the 1-phosphatase (LpxE), the 4′-phosphatase (LpxF) is MsbA-dependent when expressed in E. coli, indicating that its active site also faces the periplasmic surface of the inner membrane (Fig. 9). Both LpxE and LpxF are predicted to contain six membrane-spanning segments (Fig. 5), but they show little or no sequence similarity to each other when aligned with the BLASTp or PSI-BLAST algorithms (41). When assayed in vitro in the presence of a nonionic detergent, LpxF is not MsbA-dependent, and it does not attack the lipid A 1-phosphate group (Fig. 4).

In contrast to the 1-phosphatase, the Francisella 4′-phosphatase does not utilize hexaacylated E. coli lipid A as a substrate (Fig. 6 and Fig7), possibly because of steric hindrance caused by the 3′ secondary myristoyl chain in the vicinity of the 4′-phosphate group (Fig. 1A). The R. leguminosarum 4′-phosphatase shows a similar selectivity for tetra- or pentaacylated lipid A molecules, consistent with the fact that this strain does not incorporate a secondary acyl chain at the 3′-position of its lipid A (21, 22). LpxF can function in E. coli only when the 3′ secondary myristoyl chain is absent, as is the case in LpxM mutants (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 and supplemental Figs. 1 and 2). Organisms like Leptospira interrogans and Helicobacter pylori, which synthesize hexaacylated lipid A species lacking the 4′-phosphate group (28, 53), do not possess LpxF orthologues. These findings suggest that additional, as yet unidentified, 4′-phosphatases exist in those organisms that have evolved to accommodate the presence of the secondary 3′-acyl chain.

Many lipid phosphatases, including LpxE (26), possess three conserved sequence motifs, KX6RP, PSGH, and SRX5HX3D (29), which are also found in mammalian glucose-6-phosphatases (56). The conserved histidine residue in motif 3 is proposed to attack the phosphate group of the substrate to generate a phosphoenzyme intermediate (29). The distantly related, soluble acid phosphatase of Escherichia blattae has been crystallized in the presence of molybdate (57). The x-ray structure reveals that the molybdate in motif 3 is covalently attached to the histidine residue (57). The conserved lysine and arginine residues in motif 1 are situated near the molybdate and may normally function to bind the phosphate group of the substrate (57). The conserved histidine residue in motif 2may be the proton donor for the leaving group of the substrate (57). The replacement of this histidine residue by an alanine in glucose-6-phosphatase results in a loss of enzymatic activity (56).

LpxF contains motif 1 and most of motif 3, but motif 2 (PSGH) is missing and apparently is substituted by the sequence NCSFX2G (see below). The absence of a histidine residue in this motif suggests that LpxF uses a different catalytic mechanism than LpxE. It may be relevant that LpxF functions not only as a lipid A 4′-phosphatase but also as a 4′-phosphotransferase, generating phosphatidylinositol [4′-32P]phosphate from phosphatidylinositol and Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (25). The most closely related LpxF orthologues found in other organisms are shown in Table 2. The lipid A structures of most of these bacteria have not been characterized. However, these LpxF orthologues all share the KX4RXRP, NCSFX2G, and RX3GXHX3D motifs. To study the mechanisms of LpxE and LpxF, it will be necessary to purify both proteins, perform site-directed mutagenesis, and characterize their structures.

The observation that 4′-dephosphorylation of lipid A happens on the periplasmic surface of the inner membrane (Fig. 9) is consistent with the fact that the 4′-phosphate group of lipid A is necessary for the attachment of the Kdo disaccharide (58), which occurs on the cytoplasmic side of the inner membrane. The 4′-phosphate group may also be needed for efficient flipping by MsbA of nascent lipid A and its attached core sugars (59). The conservation of the constitutive lipid A pathway, which generates phosphorylated Kdo2-lipid A (9), may therefore reflect critical LPS assembly events at the inner rather than at the outer membrane. Once exported, however, diverse structural modifications of lipid A, including dephosphorylation (23, 26), deacylation (60), and polar group attachments (61–63), are permissible. Some of these modifications can be introduced into E. coli by heterologous expression of the appropriate modification enzyme(s) (26, 61).

LpxE and LpxF may be very useful as reporters for measuring MsbA-catalyzed LPS flip-flop in inverted inner membrane vesicles. These enzymes have the advantage that water, which is available on both sides of the membrane, is their only required co-substrate. MsbA-mediated flip-flop would allow Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A, presented to the cytoplasmic side of the inverted vesicles, to gain access to the LpxE active site, located on the inside of the vesicles. The formation of 1-dephospho-Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A by LpxE, which can easily be distinguished by TLC from Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A, should be dependent upon a functional MsbA protein and exogenous ATP in such a system.

“Monophosphoryl-lipid A” (MPL) has recently been developed as an adjuvant for use in human vaccines, given its ability to induce antigenspecific primary immune responses (16, 17, 64). The commercially available MPL preparations all lack the lipid A 1-phosphate group, because they are obtained from Salmonella LPS by mild acid hydrolysis (16, 17). LpxE can also be used to synthesize MPL efficiently (26), either in vitro or in living cells. It can even be used to prepare 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A when expressed in the heptose-deficient mutant WBB06 (26). Selective cleavage of the 1-phosphate group with retention of the Kdo disaccharide is not possible with mild acid treatment (14). The availability of LpxF now makes it possible to generate the isomeric 4′-dephospho-lipid A variant of MPL, provided that tetra- or pentaacylated lipid A species are used as the LpxF substrates. It will be interesting to explore these substances as alternative adjuvants. The use of LpxE and LpxF, in conjunction with other lipid A-modifying enzymes, such as PagL (60), PagP (51), LpxQ (65), and LpxO (66), will provide many additional options for preparing novel lipid A-based adjuvants or for generating live bacterial vaccines with altered lipid A structures.

The biological activities of lipid A are thought to require the binding of its negatively charged phosphates groups to cationic amino acid side chains on key binding proteins and receptors (67, 68). The reduced negative charge of dephosphorylated lipid A species may limit the detection of bacteria by the innate immune system. Less negatively charged lipid Amolecules can also confer resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and polymyxin (Fig. 8). It will be important to determine whether or not Francisella mutants lacking LpxE or LpxF have altered virulence properties and polymyxin sensitivity. Similarly, the isolation and characterization Rhizobium mutants lacking LpxE and/or LpxF should provide insights into the role of lipid A structure during symbiosis with plants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Francis Nano (University of Victoria, Canada) for providing us with F. novicida U112.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R37-GM-51796 (to C. R. H. R.) and GM-54882 (to R. J. C.).

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBank™/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) DQ364143 and DQ364144.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

The abbreviations used are: LPS, lipopolysaccharide; Kdo, 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid; MALDI/TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time of flight; TLR, toll-like receptors; MPL, monophosphoryl-lipid A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ellis J, Oyston PC, Green M, Titball RW. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002;15:631–646. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.4.631-646.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjostedt A. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2003;6:66–71. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kieffer TL, Cowley S, Nano FE, Elkins KL. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ancuta P, Pedron T, Girard R, Sandstrom G, Chaby R. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:2041–2046. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2041-2046.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandstrom G, Sjostedt A, Johansson T, Kuoppa K, Williams JC. FEMS Microbiol. Immunol. 1992;5:201–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinogradov E, Perry MB, Conlan JW. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:6112–6118. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips NJ, Schilling B, McLendon MK, Apicella MA, Gibson BW. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:5340–5348. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5340-5348.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribeiro AA, Zhou Z, Raetz CRH. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1999;37:620–630. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Huffel CV, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loppnow H, Brade H, Dürrbaum I, Dinarello CA, Kusumoto S, Rietschel ET, Flad HD. J. Immunol. 1989;142:3229–3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rietschel ET, Kirikae T, Schade FU, Mamat U, Schmidt G, Loppnow H, Ulmer AJ, Zähringer U, Seydel U, Di Padova F, Schreier M, Brade H. FASEB J. 1994;8:217–225. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qureshi N, Takayama K, Ribi E. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:11808–11815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki S, Tsuji T, Hamajima K, Fukushima J, Ishii N, Kaneko T, Xin KQ, Mohri H, Aoki I, Okubo T, Nishioka K, Okuda K. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:3520–3528. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3520-3528.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Persing DH, Coler RN, Lacy MJ, Johnson DA, Baldridge JR, Hershberg RM, Reed SG. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:S32–S37. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldridge JR, McGowan P, Evans JT, Cluff C, Mossman S, Johnson D, Persing D. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2004;4:1129–1138. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.7.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrett TA, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:21855–21864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrett TA, Que NL, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12457–12465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhat UR, Forsberg LS, Carlson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:14402–14410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Que NLS, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:28006–28016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Que NLS, Ribeiro AA, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:28017–28027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004009200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price NJP, Jeyaretnam B, Carlson RW, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH, Brozek KA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:7352–7356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brozek KA, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:32112–32118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu SS, York JD, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11139–11149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Karbarz MJ, McGrath SC, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49470–49478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409078200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karbarz MJ, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39269–39279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305830200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran AX, Karbarz MJ, Wang X, Raetz CRH, McGrath SC, Cotter RJ, Trent MS. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:55780–55791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406480200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stukey J, Carman GM. Protein Sci. 1997;6:469–472. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vorachek-Warren MK, Ramirez S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol.Chem. 2002;277:14194–14205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doerrler WT, Reedy MC, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11461–11464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC. Anal.Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nano FE, Zhang N, Cowley SC, Klose KE, Cheung KK, Roberts MJ, Ludu JS, Letendre GW, Meierovics AI, Stephens G, Elkins KL. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:6430–6436. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.19.6430-6436.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller JR. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Z, Ribeiro AA, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:13542–13551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raetz CRH, Purcell S, Meyer MV, Qureshi N, Takayama K. J. Biol.Chem. 1985;260:16080–16088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hampton RY, Golenbock DT, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:14802–14807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl k, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook JG, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wheeler DL, Church DM, Federhen S, Lash AE, Madden TL, Pontius JU, Schuler GD, Schriml LM, Sequeira E, Tatusova TA, Wagner L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:28–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang RF, Kushner SR. Gene (Amst.) 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bligh EG, Dyer JJ. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou Z, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:18503–18514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karow M, Georgopoulos C. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:702–710. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.702-710.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basu SS, Karbarz MJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:28959–28971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204525200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McDonald MK, Cowley SC, Nano FE. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:7638–7643. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7638-7643.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larsson P, Oyston PC, Chain P, Chu MC, Duffield M, Fuxelius HH, Garcia E, Halltorp G, Johansson D, Isherwood KE, Karp PD, Larsson E, Liu Y, Michell S, Prior J, Prior R, Malfatti S, Sjostedt A, Svensson K, Thompson N, Vergez L, Wagg JK, Wren BW, Lindler LE, Andersson SG, Forsman M, Titball RW. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:153–159. doi: 10.1038/ng1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tatusova TA, Madden TL. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999;174:247–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clementz T, Zhou Z, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:10353–10360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bishop RE, Gibbons HS, Guina T, Trent MS, Miller SI, Raetz CRH. EMBO J. 2000;19:5071–5080. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdd507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nummila K, Kilpeläinen I, Zähringer U, Vaara M, Helander IM. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;16:271–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Que-Gewirth NLS, Ribeiro AA, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Bulach DM, Adler B, Saint Girons I, Werts C, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:25411–25419. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moran AP, Lindner B, Walsh EJ. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:6453–6463. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6453-6463.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Price NPJ, Kelly TM, Raetz CRH, Carlson RW. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:4646–4655. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4646-4655.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lei KJ, Pan CJ, Liu JL, Shelly LL, Chou JY. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:11882–11886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ishikawa K, Mihara Y, Gondoh K, Suzuki E, Asano Y. EMBO J. 2000;19:2412–2423. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Belunis CJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:9988–9997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reyes CL, Chang G. Science. 2005;308:1028–1031. doi: 10.1126/science.1107733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trent MS, Pabich W, Raetz CRH, Miller SI. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:9083–9092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol.Chem. 2001;276:43122–43131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trent MS, Raetz CRH. J. Endotoxin Res. 2002;8:158. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reynolds CM, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21202–21211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ismaili J, Rennesson J, Aksoy E, Vekemans J, Vincart B, Amraoui Z, Van Laethem F, Goldman M, Dubois PM. J. Immunol. 2002;168:926–932. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Que-Gewirth NLS, Karbarz MJ, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:12120–12129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300379200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gibbons HS, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32940–32949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gangloff M, Gay NJ. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim JI, Lee CJ, Jin MS, Lee CH, Paik SG, Lee H, Lee JO. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11347–11351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414607200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raetz CRH. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1990;59:129–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou Z, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Miller SI, Raetz CRH. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43111–43121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.