Abstract

Objective To evaluate the effectiveness of treatment with collar or physiotherapy compared with a wait and see policy in recent onset cervical radiculopathy.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting Neurology outpatient clinics in three Dutch hospitals.

Participants 205 patients with symptoms and signs of cervical radiculopathy of less than one month’s duration

Interventions Treatment with a semi-hard collar and taking rest for three to six weeks; 12 twice weekly sessions of physiotherapy and home exercises for six weeks; or continuation of daily activities as much as possible without specific treatment (control group).

Main outcome measures Time course of changes in pain scores for arm and neck pain on a 100 mm visual analogue scale and in the neck disability index during the first six weeks.

Results In the wait and see group, arm pain diminished by 3 mm/week on the visual analogue scale (β=−3.1 mm, 95% confidence interval −4.0 to −2.2 mm) and by 19 mm in total over six weeks. Patients who were treated with cervical collar or physiotherapy achieved additional pain reduction (collar: β=−1.9 mm, −3.3 to −0.5 mm; physiotherapy: β=−1.9, −3.3 to −0.8), resulting in an extra pain reduction compared with the control group of 12 mm after six weeks. In the wait and see group, neck pain did not decrease significantly in the first six weeks (β=−0.9 mm, −2.0 to 0.3). Treatment with the collar resulted in a weekly reduction on the visual analogue scale of 2.8 mm (−4.2 to −1.3), amounting to 17 mm in six weeks, whereas physiotherapy gave a weekly reduction of 2.4 mm (−3.9 to −0.8) resulting in a decrease of 14 mm after six weeks. Compared with a wait and see policy, the neck disability index showed a significant change with the use of the collar and rest (β=−0.9 mm, −1.6 to −0.1) and a non-significant effect with physiotherapy and home exercises.

Conclusion A semi-hard cervical collar and rest for three to six weeks or physiotherapy accompanied by home exercises for six weeks reduced neck and arm pain substantially compared with a wait and see policy in the early phase of cervical radiculopathy.

Trial registration Clinical trials NCT00129714.

Introduction

Cervical radiculopathy is a common disorder characterised by neck pain radiating to the arm and fingers corresponding to the dermatome involved. On examination, diminished muscle tendon reflexes, sensory disturbances, or motor weakness with dermatomal/myotomal distribution can be found. The diagnosis is made primarily on clinical grounds. Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine usually shows the cause of the radiculopathy, which is usually spondylarthrosis or a herniated disc.1

Generally, degenerative cervical radiculopathy with subacute onset has a favourable prognosis, allowing a wait and see policy during the first six weeks.2 3 4 5 However, as pain is often excruciating during the first weeks to months, treatment to accelerate the improvement of pain and function would be highly valuable. Unfortunately, evidence is lacking for the effectiveness of any non-surgical treatment, including a wait and see policy, cervical collar, or physiotherapy. Two randomised trials comparing different non-invasive treatment methods in chronic cervical radiculopathy showed no benefit for physiotherapy or a cervical collar.6 7 Treatment in acute or subacute cervical radiculopathy has not yet been studied. Therefore, we evaluated the effectiveness of a semi-hard cervical collar in combination with taking as much rest as possible or physiotherapy and home exercises compared with a wait and see policy in recent onset cervical radiculopathy. We hypothesised that a treatment policy (collar or physiotherapy) would result in a faster decline in pain and improvement in function than would a wait and see policy.

Methods

We did a prospective, randomised controlled trial among patients with less than one month of symptoms and signs of cervical radiculopathy, to compare the time course of pain reduction in patients treated with a cervical collar or physical therapy with the natural course in a control group that did not receive any treatment other than tailored analgesics, as for all patients in the study. Three Dutch hospitals in The Hague, Gouda, and Amersfoort participated.

Sample size

We calculated the sample size for this three arm trial on the basis of the comparison treatment (cervical collar or physiotherapy) versus a wait and see policy, with equal allocation in the treatment arms and three repeated measurements (at entry and at three and six weeks’ follow-up), with an estimated correlation coefficient of the measurements of ρ=0.7 and a difference in the mean value of the visual analogue scale for arm pain of 10 mm, as a clinical relevant difference with an estimated standard deviation in each treatment group of 30 mm.8 As arm pain is the main complaint in cervical radiculopathy, we chose this outcome for calculating the sample size. The total sample size needed to detect this difference at a 5% level of significance with a power of 90% was 240 patients.

Participants

We asked general practitioners to refer patients with signs of recent onset (less than one month) cervical radiculopathy. All patients were examined by the local investigator (neurologist), who made a clinical diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. Inclusion criteria for the study were age 18-75 years, symptoms for less than one month, arm pain on a visual analogue scale of 40 mm or more, and radiation of arm pain distal to the elbow, plus at least one of provocation of arm pain by neck movements, sensory changes in one or more adjacent dermatomes, diminished deep tendon reflexes in the affected arm, or muscle weakness in one or more adjacent myotomes. Muscle weakness was measured with the 0 (paralysis) to 5 (normal strength) point Medical Research Council scale.9 Exclusion criteria were clinical signs of spinal cord compression, previous treatment with physiotherapy or a cervical collar, and insufficient understanding of the Dutch or English language.

Assignment

For each of the three participating hospitals, randomisation was based on a computer generated sequence that was kept in a separate box with sealed envelopes. The boxes had been prepared by an employee from the Department of Biostatistics who was not otherwise involved in the study. No other stratification or blocking procedure was used.

All envelopes were sequentially numbered. After the patient had given informed consent, the investigator opened the envelope with the next consecutive number and informed the patient about the treatment allocated. Patients and investigators were not blinded to the type of treatment.

Treatment protocols

All patients received written and oral reassurance about the usually benign course of the symptoms. We explained that a wait and see policy and treatment with collar or physiotherapy might be equally effective interventions.

Patients in all treatment groups were allowed to use painkillers. Usually, we chose paracetamol with or without a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, but if necessary we prescribed opiates. We asked patients to note their drug use, including over the counter analgesics, in a specially designed diary during the first six weeks after randomisation. Magnetic resonance imaging and electromyography were done in all cases except for patients with contraindications, such as claustrophobia. These results will be reported in a separate paper. If the patient and doctor considered pain reduction to be insufficient, the option of surgical treatment was discussed.

The cervical collar was a semi-hard collar (Cerviflex S, Bauerfeind) available in six sizes that could be snugly fitted. Patients were advised to wear the collar during the day for three weeks and to take as much rest as possible. Over the next three weeks the patients were weaned from the collar, and after six weeks they were advised to take it off completely. The patients were asked to record the time they wore the collar in a diary.

Physiotherapy with a focus on mobilising and stabilising the cervical spine was given twice a week for six weeks, by certified physiotherapists who participated in the study. The standardised sessions were “hands off” and consisted of graded activity exercises to strengthen the superficial and deep neck muscles. The physiotherapists also educated the patients to do home exercises. Patients were advised to practise every day and were asked to record the duration of the home exercises in their diary. The web appendix gives the physiotherapy protocol and the list of home exercises.

Patients in the control group were advised to continue their daily activities as much as possible. They noted in their diaries the number of parts of the day that they were able to continue their normal activities. All patients were encouraged to contact the investigators if they had questions.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures included neck pain and arm pain on a 100 mm visual analogue scale and disability assessed with the 100 point neck disability index.10 11 This index is a standardised and validated scale for neck pain with 10 five point questions on functional activities, symptoms, and concentration. The total score has to be multiplied by two. Secondary outcome measures were treatment satisfaction, use of opiates, and working status. Treatment satisfaction was assessed on a five point scale: 1=very satisfied, 2=satisfied, 3=equivocal, 4=unsatisfied, and 5=very unsatisfied; we classified scores of 1 and 2 as “satisfied” and scores of 4 and 5 as “unsatisfied.”

At entry and at three weeks, six weeks, and six months after randomisation, the patients filled out all the outcome scales in the presence of, but without interference from, the research nurse who also acted as data manager. If patients were not able to visit the outpatient clinic, the three week follow-up was done by a telephone interview. At entry and after six weeks and six months, the investigators did a standardised neurological history and examination.

Statistical analysis

For baseline values of continuous variables we used analysis of variance tests with post hoc comparisons using Bonferroni’s method. We used χ2 tests to compare dichotomous variables at baseline.

We used generalised estimating equations to examine the effect of cervical collar and physiotherapy on changes in pain scores and neck disability index during the first six weeks, with adjustment for baseline scores. Generalised estimating equations analysis is a linear regression analysis that takes into account the dependency of the observations within one patient.8 Because of expected non-normal distribution of pain scores and neck disability index scores at six months’ follow-up, we used non-parametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis test with Mann-Whitney tests for post hoc comparisons) to analyse differences between groups. We analysed secondary outcomes with χ2 statistics. We imputed missing values on the basis of the last observation carried forward technique. We used SPSS software version 16.0 for all statistical analysis except generalised estimating equations analyses, for which we used Stata 9.0.

Results

Participant flow and follow-up

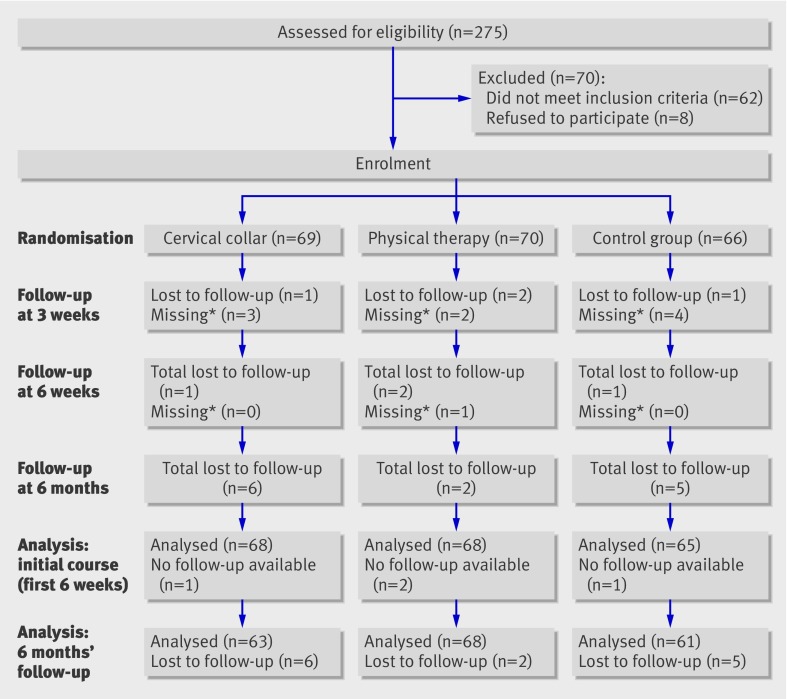

Between August 2003 and January 2007, 275 patients were assessed for eligibility. Reasons for exclusion of 70 patients were refusal to participate (n=9), previous treatment with physiotherapy (n=12) or cervical collar (n=1), longer than one month’s duration of arm pain (n=15), arm pain on visual analogue scale less than 40 mm (n=8), no cervical radiculopathy (n=26), language problems (n=6), and unknown (n=2). Some patients had more than one reason for exclusion. In January 2007 we had to terminate the recruitment of patients for practical reasons, although at that time only 205 of the planned 240 patients had been included. Of these 205 patients, 69 were allocated to cervical collar, 70 to physiotherapy, and 66 to the control group (fig 1).

Fig 1 Flow of participants. *Patients who missed one follow-up but were still participating and attended next follow-up visits

The baseline data in table 1 show that right arm pain occurred more often in the collar group. The other baseline characteristics were evenly distributed over the three groups, indicating that randomisation had been successful. The mean pain scores of 70 mm for arm pain and 60 mm for neck pain indicate the severity of the complaints. Neurological deficit consisted mainly of sensory disturbances; relatively few patients exhibited paresis or hyporeflexia (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 205 patients with recent onset cervical radiculopathy. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Collar (n=69) | Physiotherapy (n=70) | Controls (n=66) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 47.0 (9.1) | 46.7 (10.9) | 47.7 (10.6) |

| Male sex | 38 (55) | 34 (49) | 32 (48) |

| Mean (SD) body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.5 (4.8) | 26.2 (4.4) | 26.8 (4.8) |

| Mean (SD) duration of arm pain (weeks) | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.8 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.5) |

| Mean (SD) duration of neck pain (weeks) | 3.3 (2.3) | 3.0 (2.1) | 3.2 (2.0) |

| Mean (SD) VAS on arm pain (mm)* | 68.2 (19.6) | 72.1 (19.2) | 70.8 (21.2) |

| Mean (SD) VAS on neck pain (mm)* | 57.4 (27.5) | 61.7 (27.6) | 55.6 (31.0) |

| Mean (SD) neck disability index† | 41.0 (17.6) | 45.1 (17.4) | 39.8 (18.4) |

| Smoking | 30 (43) | 32 (46) | 32 (48) |

| Pain in right arm | 35 (51) | 30 (43) | 21 (32) |

| Sensory disturbances | 60 (87) | 63 (90) | 64 (97) |

| Hyporeflexia biceps reflex | 12 (17) | 13 (19) | 16 (24) |

| Hyporeflexia radial reflex | 8 (12) | 6 (9) | 6 (9) |

| Hyporeflexia triceps reflex | 16 (23) | 24 (34) | 16 (24) |

| Muscle weakness—m biceps‡ | 9 (13) | 5 (7) | 6 (9) |

| Muscle weakness—m triceps‡ | 7 (10) | 12 (17) | 6 (9) |

| Muscle weakness—m brachialis‡ | 8 (12) | 8 (11) | 8 (12) |

| Muscle weakness—m extensor digitorum communis‡ | 11 (16) | 9 (13) | 9 (14) |

| Muscle weakness—m deltoideus‡ | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 3 (5) |

| Muscle weakness—m flexor digitorum‡ | 8 (12) | 6 (9) | 4 (6) |

| Muscle weakness—m abductor digiti minimi*‡ | 5 (7) | 9 (13) | 4 (6) |

| Sick leave (partial or complete)§ | 29 (42) | 31 (44) | 26 (39) |

| Root compression on MRI¶ | 48/61 (79) | 50/61 (82) | 40/54 (74) |

MRI=magnetic resonance imaging; VAS=visual analogue scale.

*100 mm scale (0=no pain; 100=worst pain ever).

†100 point scale specific for neck pain, with 10 items on functional status (higher scores represent worse functional status).

‡As observed on standardised physical examination (MRC<5).

§Measured on three point scale (no sick leave, partial sick leave, fulltime sick leave).

¶According to original MRI report by radiologist.

Five of the 205 patients were not available for follow-up at six weeks. We found no significant difference between the three groups in the number of patients who had surgery (five in the collar group, three in the physiotherapy group, and four in the control group).

Primary outcomes

Table 2 shows the mean values for visual analogue scale and neck disability index scores at three and six weeks in the three groups. Table 3 summarises the comparison of these mean weekly changes in outcome measures in the control group with those of the collar and physiotherapy groups during the first six weeks. The amount of pain reduction per week is expressed by the estimated β coefficient.

Table 2.

Primary outcomes for collar and physiotherapy versus control group at three and six weeks. Values are mean (SD)

| Outcome measure | Three weeks | Six weeks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical collar | Physiotherapy | Control | Cervical collar | Physiotherapy | Control | ||

| Arm pain (VAS)* | 50.3 (27.7) | 55.1 (26.4) | 59.1 (26.4) | 33.5 (30.4) | 36.0 (30.7) | 48.6 (31.8) | |

| Neck pain (VAS)* | 38.0 (28.4) | 44.5 (32.5) | 55.0 (31.8) | 31.0 (28.2) | 36.2 (31.0) | 51.1 (32.7) | |

| NDI† | 33.8 (18.7) | 34.6 (16.1) | 34.3 (18.8) | 25.9 (19.1) | 27.8 (17.7) | 29.9 (20.0) | |

*Visual analogue scale from 0=no pain to 100=worst pain ever.

†Neck disability index: 10 point scale specific for neck pain with 10 items on functional status; high scores represent poor functional status.

Table 3.

Comparison of mean weekly changes* (95% confidence interval) in outcome measures in control group with those of collar and physiotherapy groups during first six weeks

| Outcome measure | Overall weekly change | Additional weekly change with collar | Additional weekly change with physiotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arm pain (VAS) (mm)† | −3.1 (−4.0 to −2.2) (P<0.001) | −1.9 (−3.3 to −0.5) (P=0.006) | −1.9 (−3.3 to −0.8) (P=0.007) |

| Neck pain (VAS) (mm)† | −0.9 (−2.0 to 0.3) (P=0.11) | −2.8 (−4.2 to −1.3) (P<0.001) | −2.4 (−3.9 to −0.8) (P=0.002) |

| NDI‡ | −1.4 (−1.9 to −0.9) (P<0.001) | −0.9 (−1.6 to −0.1) (P=0.024) | −0.8 (−1.8 to 0.2) (P=0.090) |

*On basis of generalised estimating equations (β coefficients).

†Visual analogue scale from 0=no pain to 100=worst pain ever.

‡Neck disability index: 10 point scale specific for neck pain with 10 items on functional status; high scores represent poor functional status.

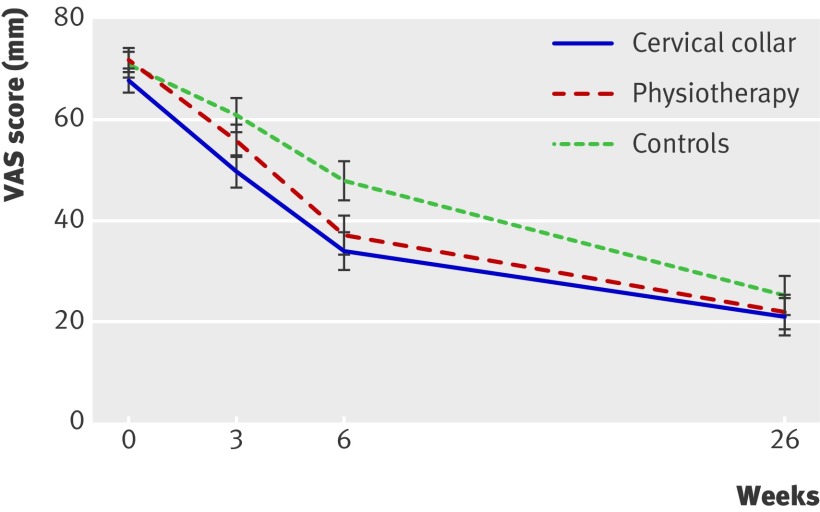

The reduction in arm pain in the control group had an estimated β of 3.1. In other words, the pain score for arm pain diminished by a little more than 3 mm/week, amounting to 19 mm after six weeks. In the collar and physiotherapy groups, the pain scores diminished significantly more than in the control group, with an extra pain reduction of 2 mm/week or 12 mm in six weeks (fig 2).

Fig 2 Arm pain over time. VAS=visual analogue scale

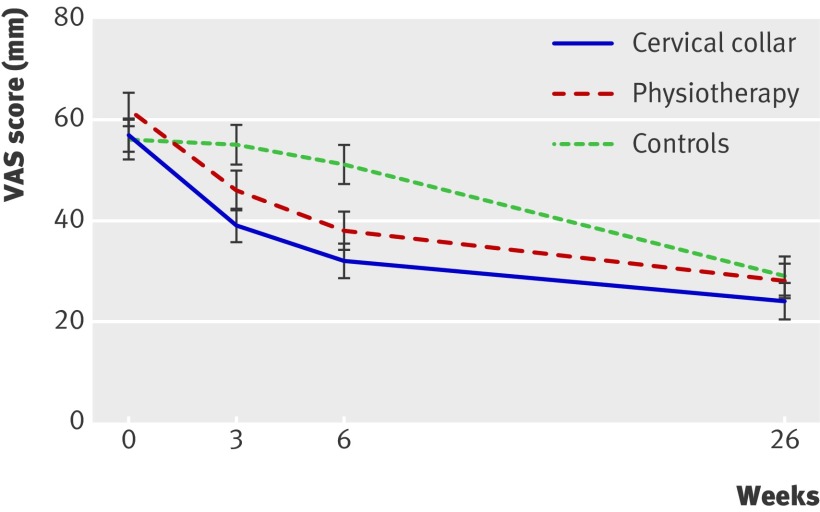

The decline in neck pain in the wait and see group over a period of six weeks had an estimated β of 0.9 mm (table 3). Treatment with a collar or physiotherapy resulted in a significant reduction in neck pain of 2.8 mm/week for the collar (amounting to 17 mm in six weeks) and 2.4 mm/week for physiotherapy (14 mm in six weeks) (fig 3).

Fig 3 Neck pain over time. VAS=visual analogue scale

The neck disability index scores of patients wearing a collar showed a significant difference in rate of improvement compared with the control group (table 3). The additional weekly change in the physiotherapy group showed a similar pattern but was not significantly different from that of the control patients.

After six months, most patients had no or limited pain (table 4). The median pain score for arm pain was zero. Median scores for neck pain were 10-20 mm. The pain scores in the two treatment groups did not differ from those of the control patients.

Table 4.

Primary outcomes for collar and physiotherapy versus control group at six months. Values are median (interquartile range) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome measures | Collar (n=63) | Physiotherapy (n=68) | Control (n=61) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm pain (VAS) (mm)† | 0 (0-30.0) | 0 (0-46.3) | 0 (0-50.0) | 0.928 |

| Neck pain (VAS) (mm)† | 10.0 (0-40.0) | 20.0 (0-43.8) | 10 (0-50.0) | 0.680 |

| NDI‡ | 8 (0-26.0) | 10 (2-29.2) | 8 (0-26.0) | 0.670 |

*Kruskal-Wallis test.

†Visual analogue scale from 0=no pain to 100=worst pain ever.

‡Neck disability index: 10 point scale specific for neck pain with 10 items on functional status; high scores represent poor functional status.

Secondary outcomes

We found no significant differences between the three groups for the secondary outcome measures (table 5). The satisfaction scores, which varied between 54% and 59%, were not different at the three and six weeks of follow-up. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opiates was similar in the three groups. Working status showed a non-significant pattern that patients treated with physiotherapy were more often on partial or complete sick leave than were those in the collar or control group.

Table 5.

Secondary outcomes: satisfaction scores, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and opiate use, and working status. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Three weeks | Six weeks | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collar (n=65) | Physiotherapy (n=66) | Control (n=61) | P value* | Collar (n=68) | Physiotherapy (n=67) | Control (n=63) | P value* | ||

| Satisfied (%)† | 38 (58) | 38 (58) | 33 (54) | 0.573 | 39/67 (58) | 39/66 (59) | 35 (56) | 0.870 | |

| NSAID use (%)‡ | 11 (17) | 10 (15) | 18 (30) | 0.094 | 7 (10) | 8 (12) | 12 (19) | 0.312 | |

| Opiate use (%)‡ | 20 (31) | 24 (36) | 19/59 (32) | 0.790 | 13 (19) | 13/66 (20) | 16 (25) | 0.630 | |

| Sick leave (%)§ | 25/64 (39) | 31 (47) | 19 (31) | 0.189 | 20 (29) | 30 (45) | 24 (38) | 0.215 | |

*Pearson χ2.

†Measured on 5 point scale: 1=very satisfied, 2=satisfied, 3=not satisfied nor unsatisfied, 4=unsatisfied, 5=very unsatisfied; 1 and 2 classified as “satisfied,” and 4 and 5 classified as “unsatisfied.”

‡Based on reported use in patients’ diaries.

§Percentage on partial or complete sick leave.

Adherence

We used the patients’ diaries to verify adherence to the allocated treatment. Dividing a day into four parts (morning, afternoon, evening, and night), patients wore the collar during the first three weeks for a mean of 2.4 parts of the day; six patients did not wear the collar at all. In weeks four to six, the collar was worn for a mean of 1.2 parts of the day.

In addition to the 12 physiotherapy sessions, 52% (34/65) of the patients exercised at home for more than 10 minutes a day during the first three weeks, 36% (24/65) exercised up to 10 minutes, and 12% (8/65) did not exercise at all. During weeks three to six, exercise time decreased slightly: 43% (28/65) exercised more than 10 minutes, 43% (28/65) exercised up to 10 minutes, and 14% (9/65) did not exercise at all. Sixty-one per cent (34/56) of patients in the control group noted in their diaries that they could continue their normal activities during three or four parts of the day.

Discussion

Clinical significance of results

In this randomised study of patients with recent onset cervical radiculopathy, we found that treatment with a semi-hard cervical collar in combination with taking as much rest as possible for three weeks, with a maximum of six weeks, or standardised physiotherapy and doing home exercises for six weeks resulted in a significant reduction in arm and neck pain compared with a wait and see policy. The differences in pain reduction between the treatment and control groups varied from 12 to17 mm on a 100 mm visual analogue scale in six weeks and were highly statistically significant. Studies on visual analogue scale scores consider this difference to be clinically meaningful.12 13 14 15 16 One such study in patients with acute pain, mainly in emergency departments, showed that the meaning of a difference in pain scores depends on the height of the scores. In patients with scores between 34 and 66 mm, as in our patients at three and six weeks, a difference of 17 (SD 10) mm was found to be clinically meaningful.16 However, the setting differed from our study in which patients with subacute onset cervical radiculopathy were treated, and this may limit the interpretation of these data for our study population.

Disability decreased 9 points on the neck disability index over six weeks in the control patients, with an additional 5 point decrease in both the collar and physiotherapy groups. The additional effect of the collar on disability was small but statistically significant. Although the additional effect of physiotherapy on disability was not significant, a favourable effect on disability occurred, presumably owing to reduction. The less prominent effect on the neck disability index compared with the pain scores may well be explained by the fact that the index predominantly measures the disability caused by neck pain, whereas arm pain scores were highest initially and showed the largest improvement. All differences between the groups on the visual analogue scale and the neck disability index scores were no longer present at the six month follow-up. Most patients had no or limited pain, confirming earlier reports of the favourable natural course of the disease.7 17 18 As the patients had arm and neck pain for a mean of three weeks before entering the study, and as they were treated for six weeks, we have shown that both the cervical collar and physiotherapy are efficacious within this time frame. Considering the degree of pain reduction obtained at six weeks, further interventions after this period are not likely to be of benefit in most patients.

Comparison with other studies

We could find no evidence in the literature showing the efficacy of a cervical collar or physiotherapy in patients with subacute onset degenerative cervical radiculopathy. In 1966 a randomised clinical trial included 493 patients with cervical root symptoms in five treatment arms (traction, positioning, collar, placebo tablets, placebo heat treatment). No significant difference in pain and ability to work was found between the five treatment groups. Seventy-five per cent of patients reported pain relief at four weeks’ follow-up.7 However, comparison of the results of this study with ours is hampered by the fact that the method as described in the 1966 article does not meet the current standard for clinical trials—for example, validated outcome scales were not available.

Persson et al did a randomised clinical trial comparing physiotherapy and a hard collar in patients with chronic (more than three months, median 21 months) cervical radiculopathy who were randomised to surgery, physiotherapy, or cervical collar. Surgery was superior for pain relief at four months’ follow-up. At 16 months’ follow-up, no difference existed between the three groups in terms of pain, muscle strength, or sensory loss.6 19 Marked differences exist between our study and that of Persson et al. Our target study group encompassed only patients with less than one month of arm pain. Our study also differed with respect to the type of collar used. A soft collar is reported to give insufficient support. A hard collar, as used in Persson’s study, can cause serious discomfort.20 Therefore, we decided to compromise with a snugly fitting semi-hard collar.6 19 21 In Persson’s study, the collar had to be worn over a three month period. However, several authors warn about counterproductive effects of prolonged immobilisation.20 22

Mechanisms of collar and physiotherapy

Little evidence exists on the mechanisms of collars and physiotherapy in giving pain relief, and the explanations provided in the literature are largely hypothetical. The collar probably reduces foraminal root compression and associated root inflammation by immobilising the neck, which might explain the larger reduction of arm pain compared with neck pain and neck disability as found in our study.23

Physiotherapy aims at restoring range of motion and strengthening the neck musculature,24 probably diminishing secondary musculoskeletal problems, although the mechanism of pain reduction is unclear. Thirteen (6.3%) of the 205 patients, equally distributed over the three groups, were surgically treated during the six months of follow-up. Considerably higher percentages of surgery for cervical radiculopathy are reported in the literature.18 25 We discussed surgical treatment options with patients who had persisting or intractable pain and referred them to our neurosurgical department. The low rate of surgery in our cohort may be due to the fact that our patients were included at an early stage, whereas previous studies including more chronic cases encompassed a larger number of patients who did not respond to non-surgical treatment. Furthermore, patients were possibly less inclined to have surgery because they participated in a study aimed at reducing signs and symptoms by non-surgical interventions.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, for obvious reasons, the patients could not be blinded, and neither were the examiners blinded. We tried to prevent bias by asking the patients to fill out the visual analogue scale scores and neck disability index in the presence of a research nurse who did not examine the patients.

Secondly, the positive results of a collar or physiotherapy might be partially explained by non-specific effects—for instance, by the attention given by a physiotherapist or the attention received when wearing a visible collar. By far the most professional attention, however, was given to patients receiving physiotherapy for the full six weeks, yet the treatment effect was largest for the collar that was worn mainly during the first three weeks. In addition, the treatment satisfaction scores did not differ between the three groups. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opiate use, and sick leave percentages were similar as well.

Thirdly, the quality of data on adherence to treatment obtained with diaries may be compromised in a condition that tends to improve quite rapidly. However, we conclude that adherence to the two treatment strategies, wearing a collar and taking rest versus exercise therapy, was reasonable. These approaches were sufficiently different from that of the control patients, who largely succeeded in continuing their normal activities of daily life.

A fourth limitation is that we included patients in our study on the basis of clinical criteria and used standardised magnetic resonance imaging and electromyography examinations after randomisation because we wanted to stay close to clinical practice. Degenerative cervical radiculopathy is primarily a clinical diagnosis, and magnetic resonance imaging is usually done if surgery is considered or if doubt exists about the cause of the radiculopathy. In addition, findings of imaging are often falsely negative,26 27 as was also shown by our study in which 20-25% of the clinically selected patients had no root compression on magnetic resonance imaging.

We cannot entirely exclude the possibility that patients with other causes of arm pain than cervical radiculopathy participated in the study. The number will have been small as we required a firm clinical diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy, followed by strict inclusion criteria. Patients with other causes of arm pain are unlikely to change the results of the study, as we would expect that they were equally distributed over the three arms.

A final limitation is that we did not reach the calculated sample size of 240 patients. Because of the magnitude of the differences in pain reduction, with comfortable 95% confidence intervals, an extra 35 patients would have been unlikely to have changed our results.

Conclusion and policy implication

The results of this randomised clinical trial show a clinically relevant short term reduction in pain in recent onset cervical radiculopathy with two therapeutic interventions—that is, a semi-hard cervical collar combined with taking rest and standardised physiotherapy accompanied by home exercises—compared with a wait and see policy. We recommend a semi-hard cervical collar and taking rest in recent onset cervical radiculopathy because the costs are lower than for physiotherapy, although physiotherapy is a good alternative with an almost similar efficacy.

What is already known on this topic

Cervical radiculopathy is a common disorder with a favourable prognosis

Pain is often excruciating during the first weeks to months

What this study adds

Treatment with a semi-hard cervical collar or physiotherapy together with home exercises led to relevant pain reduction in the acute and subacute phase of cervical radiculopathy

A semi-hard cervical collar is recommended on the basis of its low costs and best efficacy

Contributors: BK contributed to the development of the trial design and protocol, was responsible for the day to day management of the trial, contributed to recruiting patients, examined patients, and contributed to interpreting the data and preparing the manuscript. JTJT had overall responsibility for the conduct of the trial and contributed to developing the trial design, recruiting the patients, interpreting the data, and preparing the manuscript. AB did the statistical analysis and contributed to interpreting the data and preparing the manuscript. FN and MdV contributed to interpreting the data and preparing the manuscript. All authors have full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. JTJT is the guarantor. Other contributors were: Freek Verheul and Annelies Dalman, Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda, Netherlands, and Willem Oerlemans, Meander Medical Centre, Amersfoort, Netherlands, who examined patients; Hans van Houwelingen, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, Netherlands, who contributed to the initial design of the study; Bas van der Kallen and Geert Lycklama-a-Nijeholt, neuroradiologists, Medical Centre Haaglanden, The Hague, Netherlands; Ella de Wolf, research nurse, Medical Centre Haaglanden, who contributed to the organisation of the study and processed data in SPSS; Henk Franken, Leiden University Medical Centre, who prepared the randomisation envelopes; and Ando Kerlen, physiotherapist, Medical Centre Haaglanden, who contributed to developing the physiotherapy protocol.

Funding: The salary for the research nurse was paid by the Non-profit Foundation, dr Eduard Hoelen Stichting, Wassenaar, Netherlands.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The medical ethics review committees of the three contributing hospitals gave ethical approval. All patients gave informed consent before taking part.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3883

References

- 1.Kuijper B, Tans JTJ, Schimsheimer RJ, van der Kallen BFW, Beelen A, Nollet F, et al. Degenerative cervical radiculopathy: diagnosis and conservative treatment: a review. Eur J Neurol 2009;16:15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams C. Cervical spondylotic radiculopathy and myelopathy. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, eds. Handbook of clinical neurology. Vol 26. Elsevier Publishing Company, 1976:97-112.

- 3.Bush K, Chaudhuri R, Hillier S, Penny J. The pathomorphologic changes that accompany the resolution of cervical radiculopathy: a prospective study with repeat magnetic resonance imaging. Spine 1997;22:183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spurling RG, Segerberg LH. Lateral intervertebral disk lesions in the lower cervical region. JAMA 1953;151:354-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinas FC, Wilner H, Rengachary S. The spontaneous resorption of herniated cervical discs. J Clin Neurosci 2001;8:542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persson LC, Carlsson CA, Carlsson JY. Long-lasting cervical radicular pain managed with surgery, physiotherapy, or a cervical collar: a prospective, randomized study. Spine 1997;22:751-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pain in the neck and arm: a multicentre trial of the effects of physiotherapy, arranged by the British Association of Physical Medicine. BMJ 1966;1:253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Twisk JW. Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology: a practical guide. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- 9.Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom. Aids to the examination of the peripheral nervous system. Pedragon House, 1978. (Memorandum No 45.)

- 10.Vernon H, Mior S. The neck disability index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1991;14:409-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy MJ, Grevitt MP, Silcocks P, Hobbs G. The reliability of the Vernon and Mior neck disability index, and its validity compared with the short form-36 health survey questionnaire. Eur Spine J 2007;16:2111-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly AM. Does the clinically significant difference in visual analog scale pain scores vary with gender, age, or cause of pain? Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:1086-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly AM. The minimum clinically significant difference in visual analogue scale pain score does not differ with severity of pain. Emerg Med J 2001;18:205-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Todd KH. Clinical versus statistical significance in the assessment of pain relief. Ann Emerg Med 1996;27:439-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todd KH, Funk KG, Funk JP, Bonacci R. Clinical significance of reported changes in pain severity. Ann Emerg Med 1996;27:485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bird SB, Dickson EW. Clinically significant changes in pain along the visual analog scale. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:639-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binder AI. Cervical spondylosis and neck pain. BMJ 2007;334:527-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radhakrishnan K, Litchy WJ, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy: a population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain 1994;117:325-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persson LC, Moritz U, Brandt L, Carlsson CA. Cervical radiculopathy: pain, muscle weakness and sensory loss in patients with cervical radiculopathy treated with surgery, physiotherapy or cervical collar: a prospective, controlled study. Eur Spine J 1997;6:256-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazanec D, Reddy A. Medical management of cervical spondylosis. Neurosurgery 2007;60(1 supp1 1):S43-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellenberg MR, Honet JC, Treanor WJ. Cervical radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994;75:342-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polston DW. Cervical radiculopathy. Neurol Clin 2007;25:373-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naylor JR, Mulley GP. Surgical collars: a survey of their prescription and use. Br J Rheumatol 1991;30:282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosomoff HL, Fishbain D, Rosomoff RS. Chronic cervical pain: radiculopathy or brachialgia: noninterventional treatment. Spine 1992;17(10 suppl):S362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heckmann JG, Lang CJ, Zobelein I, Laumer R, Druschky A, Neundorfer B. Herniated cervical intervertebral discs with radiculopathy: an outcome study of conservatively or surgically treated patients. J Spinal Disord 1999;12:396-401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nardin RA, Patel MR, Gudas TF, Rutkove SB, Raynor EM. Electromyography and magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of radiculopathy. Muscle Nerve 1999;22:151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sengupta DK, Kirollos R, Findlay GF, Smith ET, Pearson JC, Pigott T. The value of MR imaging in differentiating between hard and soft cervical disc disease: a comparison with intraoperative findings. Eur Spine J 1999;8:199-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]