Abstract

Previously we reported a broadly HIV-1 neutralizing mini-antibody (Fab 3674) of modest potency that was derived from a human non-immune phage library by panning against the chimeric gp41-derived construct NCCG-gp41. This construct presents the N-heptad repeat of the gp41 ectodomain as a stable, helical, disulfide-linked trimer that extends in helical phase from the six-helix bundle of gp41. In this paper, Fab 3674 was subjected to affinity maturation against the NCCG-gp41 antigen by targeted diversification of the CDR-H2 loop to generate a panel of Fabs with diverse neutralization activity. Three affinity-matured Fabs selected for further study, Fabs 8060, 8066 and 8068, showed significant increases in both potency and breadth of neutralization against HIV-1 pseudotyped with envelopes of primary isolates from the standard subtypes B and C HIV-1 reference panels. The parental Fab 3674 is 10-20 fold less potent in monovalent than bivalent format over the entire B and C panels of HIV-1 pseudotypes. Of note is that the improved neutralization activity of the affinity-matured Fabs relative to the parental Fab 3674 was, on average, significantly greater for the Fabs in monovalent than bivalent format. This suggests that the increased avidity of the Fabs for the target antigen in bivalent format can be partially offset by kinetic and/or steric advantages afforded by the smaller monovalent Fabs. Indeed, the best affinity-matured Fab (8066) in monovalent format (∼50 kDa) was comparable in HIV-1 neutralization potency to the parental Fab 3674 in bivalent format (∼120 kDa) across the subtypes B and C reference panels.

Introduction

Fusion of the HIV-1 virus and host cell membranes is mediated by the surface envelope (Env) glycoproteins gp120 and gp41 (Berger et al., 1999; Eckert et al., 2001a). The binding of gp120 to the primary receptor CD4 and the coreceptor CXCR4 triggers a series of conformational changes in both gp120 and gp41 that lead to the formation of a pre-hairpin intermediate (PHI) of the ectodomain of gp41 (Furuta et al., 1998). In the PHI the C-heptad repeat (C-HR; residues 623-663) and the helical coiled-coil trimer of the N-heptad repeat (N-HR, residues 542-591) do not interact with one another but bridge the viral and target cell membranes in an overall extended conformation through the C- and N-termini of gp41, respectively (Chan et al., 1998b; Furuta et al., 1998; Eckert et al., 2001a; Gallo et al., 2003; Melikyan et al., 2006). The subsequent formation of a six-helix bundle (6-HB) with the N-HR trimer surrounded by three C-HR helices (Chan et al., 1997; Tan et al., 1997; Weissenhorn et al., 1997; Caffrey et al., 1998) brings the viral and target cell membranes into contact eventually leading to fusion. The N-HR and C-HR in the PHI are accessible and can therefore be targeted by gp41-directed fusion inhibitors (Wild et al., 1992; Jiang et al., 1993; Wild et al., 1994; Eckert et al., 1999; Louis et al., 2001; Root et al., 2001; Eckert et al., 2001b; Bewley et al., 2002; Louis et al., 2003; Matthews et al., 2004; Root et al., 2004; Eckert et al., 2008).

The conserved nature of the gp41 N-HR suggests that it may represent an attractive target for generating antibodies with broadly neutralizing activity. However, the majority of antibodies raised against both the N-HR and 6-HB of gp41 have been only weakly inhibitory or non-neutralizing (Jiang et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2000; Golding et al., 2002; Louis et al., 2003), presumably because of the transient exposure of the N-HR trimer during the fusion process and the large size of IgG's making access difficult (Hamburger et al., 2005; Steger et al., 2006; Eckert et al., 2008). To date, six modestly neutralizing antibodies directed against the N-HR have been reported: Fab 3674 (Gustchina et al., 2007), D5 (Miller et al., 2005; Luftig et al., 2006), 8K8 (Nelson et al., 2008), DN9 (Nelson et al., 2008), m46 (Choudhry et al., 2007) and m44 (Zhang et al., 2008).

In recent work (Louis et al., 2005; Gustchina et al., 2007) we made use of a chimeric protein known as NCCG-gp41 (Louis et al., 2001) which presents the N-HR as a stable, helical, disulfide-linked trimer that extends in helical phase from the 6-HB core of gp41, to select monoclonal antibodies by phage display from a synthetic human combinatorial antibody library (HuCAL GOLD) comprising more than 1010 human specificities (Knappik et al., 2000; Kretzschmar et al., 2002; Rothe et al., 2008). The HuCAL GOLD library includes diversification of all six complementary determining regions (CDRs) according to the sequence and length variability found in naturally rearranged human antibodies (Rothe et al., 2008). Our initial attempts resulted in a set of Fabs that inhibited Env-mediated cell fusion in a vaccinia virus-based fusion assay but were non-neutralizing in an Env-pseudotyped virus neutralization assay (Louis et al., 2005). Subsequently, Fab 3674 with broad neutralizing activity against HIV-1 pseudotyped with Envs from diverse laboratory adapted B strains of HIV-1 and primary isolates of subtypes A, B and C, was isolated (Gustchina et al., 2007). Fab 3674 recognizes both the internal timeric N-HR coiled-coil, as well as the 6-HB of gp41 (Gustchina et al., 2007).

The D5 monoclonal antibody was derived from a naive scFv library selected by panning against the gp41-derived construct 5-helix (Miller et al., 2005; Luftig et al., 2006). 5-helix is a single chain construct in which the N-HR trimer is surrounded by only 2 C-HR helices, thereby exposing two of the three N-HR helices (Root et al., 2001). There are a number of interesting differences between Fab 3674 and D5. While Fab 3674 and the C34 peptide (derived from the C-HR and comprising residues 628-661 of gp41; (Chan et al., 1998a)) neutralize HIV-1 either additively (Fab in monovalent format) or synergistically (Fab in bivalent format) (Gustchina et al., 2007), binding of D5 and C34 appears to be mutually exclusive (Miller et al., 2005). 8K8 and DN9 (Nelson et al., 2008) monoclonal antibodies were selected from rabbit (b9 rabbit immunized against N35CCG-N13) and human (infected HIV-1 individual) phage display libraries, respectively, by panning against the N-HR trimer mimetic N35CCG-N13 (Louis et al., 2003). In contrast to Fab 3674, 8K8 and DN9 are targeted specifically to the N-HR trimeric coiled-coil and do not bind to the 6-HB of gp41. m46 (Choudhry et al., 2007) and m44 (Zhang et al., 2008) monoclonal antibodies were selected from a human immune phage library by panning against gp140, a soluble form of the Env ectodomain comprising uncleaved gp120 and gp41; m46 binds only to 5-HB but not to 6-HB or the N-HR trimer, while m44 binds to 5-helix and the 6-HB, but not to the N-HR trimer.

In this paper we set out to improve the potency of Fab 3674 (Gustchina et al., 2007) by affinity maturation against the NCCG-gp41 antigen using targeted diversification of the CDR-H2 loop. Due to their unique modular structure HuCAL antibodies are ideal for the specific optimization of CDRs (Knappik et al., 2000). Recently, an affinity improvement of 5000-fold was achieved by parallel CDR-L3 and CDR-H2 diversification and subsequent combination of optimized CDR-L3 and CDR-H2 antibodies (Steidl et al., 2008).

Affinity maturation of the CDR-H2 of Fab 3674 resulted in the generation of a panel of Fabs that displayed significantly improved affinity toward the target antigen NCCG-gp41 and exhibited diverse HIV-1 neutralizing activity. The three best Fabs displayed enhanced HIV-1 neutralization properties relative to the original Fab 3674, both in terms of IC50 values and neutralization breadth over a standard panel of Envs from primary isolates of HIV-1 subtypes B and C.

Results and Discussion

Affinity maturation of Fab 3674

The parental neutralizing Fab 3674 (Gustchina et al., 2007) was derived from the synthetic human Fab library HuCAL Gold comprising more than 1010 antibody genes (Knappik et al., 2000) by panning against NCCG-gp41 (Louis et al., 2001), a construct that presents the N-HR of gp41 as a stable helical, disulfide-linked trimer that extends in helical phase from the 6-HB core. Fab 3674 was subjected to affinity maturation by diversification of the heavy chain CDR-H2 loop. Specifically, the original CDR-H2 sequence of the Fab 3674 gene was replaced by a repertoire of CDR-H2 sequences designed according to the respective amino acid distribution at each position of naturally occurring, human rearranged antibody genes (Virnekas et al., 1994; Knappik et al., 2000; Rothe et al., 2008). A total of 1.3×106 Fab genes with different heavy chain CDR-H2 loops were generated in this manner. After two rounds of panning against NCCG-gp41 coupled to magnetic beads, applying increased washing stringency relative to that used for the parental Fab 3674, the enriched pool of Fab genes was subcloned into an expression vector. 368 clones were tested for binding to NCCG-gp41 coupled beads, the 10 clones with the best signal and an additional 10 clones selected at random were sequenced, and 12 unique Fabs were found. The 10 Fabs with the highest ELISA signal on NCCG-gp41 were selected for further characterization and were expressed in both monovalent (mF) and bivalent (bF) formats. The latter is obtained by the addition of a helix-loop-helix dimerization domain to the C-terminus of the heavy chain (Pluckthun, 1992).

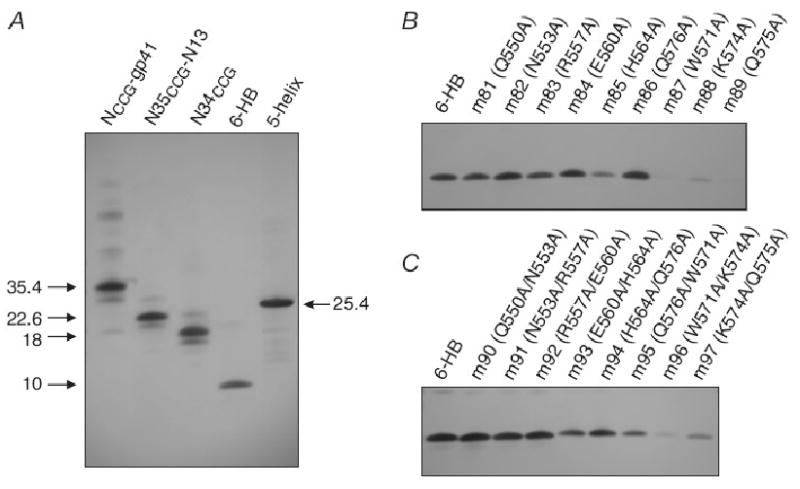

Table 1 summarizes the CDR-H2 sequences together with the equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) for the binding of Fab 3674 and the 10 affinity-matured Fabs (in monovalent format) to NCCG-gp41. The KD values, determined by solution equilibrium titration using an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) based affinity measurement (Haenel et al., 2005; Steidl et al., 2008), range from 7 to 25 nM, compared to ∼97 nM for the parental Fab 3674. Western blot analysis against a panel of gp41 ectodomain-derived constructs comprising NCCG-gp41, N35CCG-N13, N35CCG, 6-HB and 5-HB revealed the same pattern of binding for all the Fabs, including the parental Fab 3674 (cf. Fig. 2 of (Gustchina et al., 2007). Thus all the Fabs recognize the fully exposed internal trimer of N-HR helices (cf. NCCG-g41, N34CCG, N35CCG-N13), the (N-HR)3/C-HR)3 six helix bundle (cf. 6-HB and NCCG-gp41), and a partially exposed trimer of N-HR helices (cf 5-helix in which two of the three N-HR helices are exposed) (Fig. 1A). Likewise, the pattern of intensities observed for the single (Fig. 1B) and double (Fig. 1B) alanine mutants of 6-HB comprising surface exposed residues of the N-HR (Gustchina et al., 2007) is similar, indicating that the parental and affinity-matured Fabs bind to the same gp41 epitope comprising the shallow groove of N-HR residues that is surface exposed and lies between two C-HR helices of the 6-HB.

Table 1.

Affinity of monovalent, affinity-matured Fabs for the antigen NCCG-gp41 and corresponding CDR-H2 sequences.

| Antibody | KD (nM) |

CDR-H2 sequence | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3674 | 96.5 | G | I | I | P | I | F | G | M | A | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8059 | 7.2 | S | I | I | P | L | F | G | T | T | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8060 | 10.1 | S | I | I | P | I | F | G | S | T | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8061 | 21.4 | S | I | I | P | M | M | G | S | T | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8062 | 16.8 | S | I | I | P | L | F | G | F | A | V | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8063 | 19.9 | S | I | I | P | V | I | G | S | T | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8064 | 9.5 | S | I | I | P | W | F | G | S | T | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8065 | 25.1 | S | I | I | P | W | H | G | G | T | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8066 | 15.3 | S | I | I | P | I | F | G | T | T | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8068 | 15.9 | S | I | I | P | L | M | G | T | T | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 8069 | 7.1 | S | I | I | P | L | F | G | W | A | N | Y | A | Q | K | F | Q | G |

| 50 | 51 | 52 | 52a | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | ||

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis under non-reducing conditions of gp41-derived constructs reacting with the monovalent Fab mF-8066. (A) NCCG-gp41, N35CCG-N13, N34CCG, 6-HB and 5-helix. (B) Single and (C) double alanine scanning mutants of 6-HB involving solvent exposed N-HR residues that lie in the shallow groove between the two C-HR helices (Gustchina et al., 2007). The molecular weights of trimeric NCCG-gp41 (35.4 kDa), N35CCG-N13 (22.6 kDa) and N34CCG (18 kDa) held together by disulfide bridges are indicated. 6-HB is a 10 kDa popypeptide chain spanning the N-HR and C-HR that adopts a trimeric fold (comprising the minimal thermostable ectodomain core of gp41) during Western blotting upon transfer of the protein from the gel to the nitrocellulose membrane. 5-helix is a single chain polypeptide of 25.4 kDa.

Neutralization activity of affinity-matured Fabs against laboratory adapted strains of subtype B HIV-1

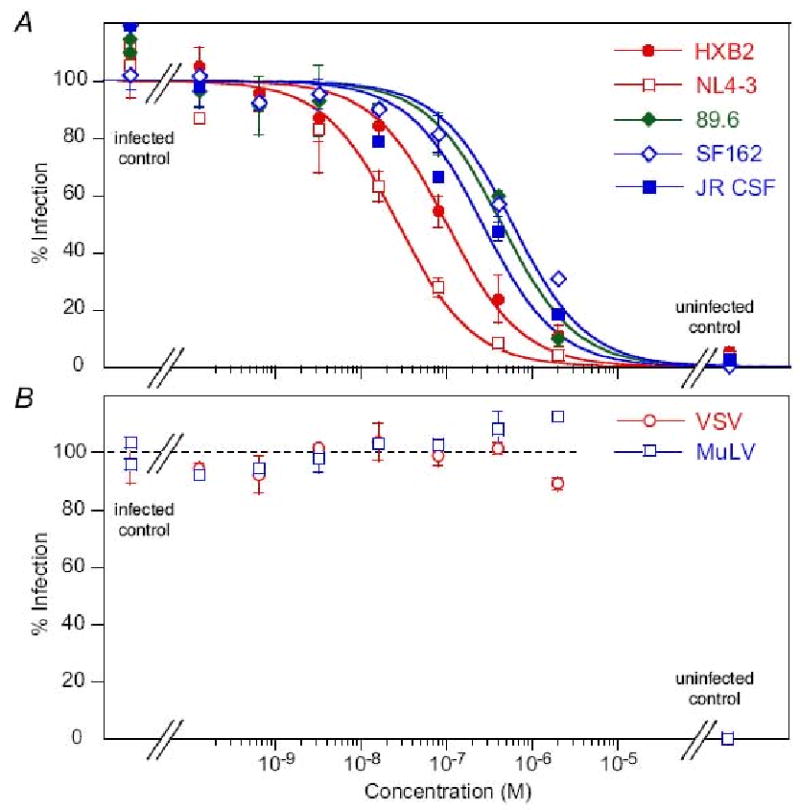

The neutralization activity of the parental Fab 3674 in monovalent format and the affinity-matured monovalent Fabs against diverse laboratory-adapted HIV-1 subtype B strains using an Env-pseudotyped virus neutralization assay are reported in Table 2. Examples of dose-response curves against diverse laboratory-adapted HIV-1 subtype B strains for one of the Fabs, mF-8066, is shown in Fig. 1A. As expected no neutralization activity is observed for two negative control viruses pseudotyped with an amphotrophic Env from Murine leukemia virus (MuLV) and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) (Fig. 1B).

Table 2.

Neutralization activity of affinity-matured Fabs against HIV-1 subtype B laboratory-adapted strains and primary isolates BaL01 and BaL26.

| HIV-1 Env strain, IC50 (nM)* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody | HXB2 | NL4-3 | SF162 | JR CSF | 89.6 | BaL01 | BaL26 |

| 3674 | 630 ± 160 | 480 ± 220 | 2500 ± 690 | 2100 ± 600 | NA | 1100 ± 270 | 1900 ± 960 |

| 8059 | 400 ± 89 | 98 ± 26 | 3200 ± 850 | 1500 ± 470 | 1100 ± 240 | 1100± 310 | 970 ± 420 |

| 8060 | 130 ± 30 | 36± 7 | 1000 ± 200 | 620 ± 380 | 500 ± 130 | 360 ± 120 | 360 ± 130 |

| 8061 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8062 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8063 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8064 | 790 ± 270 | 270 ± 140 | 5200 ± 1800 | NA | 1300 ± 560 | 2300 ± 1300 | 1100 ± 520 |

| 8065 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8066 | 82 ± 29 | 26 ± 9 | 510 ± 150 | 230 ± 160 | 380 ± 110 | 200 ± 73 | 280 ± 69 |

| 8068 | 160 ± 72 | 34 ± 11 | 1400 ± 380 | 110 ± 92 | 350 ± 110 | 450 ± 110 | 580 ± 220 |

| 8069 | 880 ± 300 | 360 ± 210 | NA | NA | 660 ± 400 | NA | 1900 ± 760 |

NA, no activity. Neutralization activity was too weak to reliably determine an IC50.

Surprisingly, not all of the Fabs with improved binding affinity towards the target NCCG-gp41 antigen showed HIV-1 neutralization activity. This points to the importance of kinetic restriction and suggests that the association and/or dissociation rate constants also play a key role in determining neutralization activity (Steger et al., 2006). Indeed, 4 Fabs (mF-8061, mF-8062, mF-8063 and mF-8065) with KD values ranging from 17-25 nM showed no detectable neutralization activity. By way of contrast, the parental mF-3674 (KD ∼ 97 nM) neutralized 6 out of 7 the strains with IC50 values ranging from ∼480 to ∼2100 nM. Of the 6 affinity-matured Fabs that were neutralizing, the KD values for binding to NCCG-gp41 were ≤ 15 nM, but beyond that there was no apparent correlation between the actual KD and IC50 values. For example, mF-8069 had the lowest KD value (7 nM) of all the affinity-matured Fabs but was comparable to or slightly worse than the original mF-3674 in terms of HIV-1 neutralization activity. Three matured Fabs, 8060, 8066 and 8068, however, displayed significantly improved neutralization activity relative to mF-3674 and were selected for further study. The best, mF-8066, exhibited a 5-20 fold increase in HIV-1 neutralization potency relative to mF-3674 for 6 out of the 7 HIV-1 strains; for the seventh HIV-1 strain, 89.6, mF-8066 was neutralizing while mF-3674 was not.

A comparison of the CDR-H2 sequences shown in Table 1 in the light of the neutralization results is of interest. Three (8061, 8062 and 8065) of the four non-neutralizing Fabs, have a substitution of Phe54 to a less bulky amino acid (Met, Ile and His, respectively). The fourth non-neutralizing Fab (8063), as well as the poorly neutralizing Fab 8069 have a substitution to an aromatic residue (Phe and Trp, respectively) at position 56. An aromatic residue at position 53 (cf. Fabs 8064 and 8065) is also unfavorable. The three best Fabs, 8060, 8066 and 8068, all have an Ile or Leu at position 53, and a Ser or Thr at position 56. The original Fab, 3674 also has an Ile at position 53, but a longer amino acid, Met, at position 56. One can therefore conclude that residues at position 53, 54 and 56, with an optimal sequence of Ile/Leu, Phe and Ser/Thr, respectively, likely make key contacts with gp41.

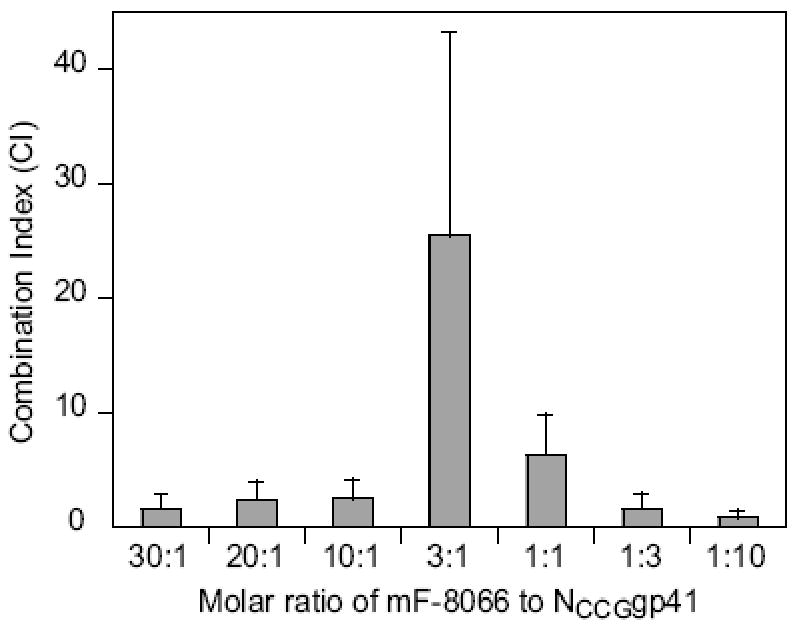

NCCG-gp41 and Fab mF-8066 are mutually antagonistic

To rule out any potential non-specific effects inherent in the Env-pseudotyped HIV neutralization assay, we tested whether addition of the target antigen, NCCG-gp41, in the assay could adsorb out the neutralization activity of the most potent monovalent Fab mF-8066. Since NCCG-gp41 was designed to bind to the C-HR of the PHI and is itself a potent nanomolar inhibitor of HIV-1 fusion (Louis et al., 2001), we tested the neutralizing activity of mixtures of mF-8066 and NCCG-gp41 in various fixed molar ratios ranging from 30:1 to 1:10, and analyzed the combination effects using the method of Chou and Talalay (Chou et al., 1981; Chou et al., 1984) as described previously (Gustchina et al., 2006). Since the NCCG-gp41 trimer has three symmetrically related binding sites for Fab 8066, one would expect that maximum antagonism between mF-8066 and NCCG-gp41 would be observed at a molar ratio of 3:1. When an excess of either mF-8066 or NCCG-gp41 is present in the mixture, one would predict that neutralization activity is dominated by the inhibitor in excess. The dose reduction index (DRI) of inhibitor x in combination with inhibitor y is given by DRIx = (IC50)x/IC50)x,y, where (IC50)x and IC50)x,y are the IC50's of x alone and in combination with y, respectively. The combination index (CI) which describes the summation of the effects of the two inhibitors is given by CI = (DRIx)-1 + (DRIy)-1 + (DRIxDRIy)-1 (Chou et al., 1984; Gustchina et al., 2006). CI values equal to, greater than, or less than 1 are indicative of additive, antagonistic and synergistic effects, respectively. The results are displayed in Fig. 3 and are as predicted above. At high molar ratios (mF-8066 to NCCG-gp41 ratios of 30:1 and 1:10), the effects are essentially additive with CI values close to 1. Maximum antagonism is observed at a molar ratio of mF-8066 to NCCG-gp41 of 3:1 with a CI of ∼25. At intermediate molar ratios, increasing antagonism (i.e. larger CI values) is observed as the molar ratio approaches 3:1 of mF-8066 to NCCG-gp41.

Figure 3.

Antgonism of Fab mF-8066 and the NCCG-gp41 antigen observed in an HXB2 Env-pseudotyped HIV neutralization assay. IC50's were obtained from dose-response curves measured for a range of fixed molar combination ratios of mF 8066 and NCCG-gp41. The IC50's for mF-8066 and NCCG-gp41 alone are 82±29 and 34±10 nM, respectively. The KD for the binding of mF-8066 to NCCG-gp41 is 15 nM (Table 1). Combination index (CI) values greater than 1 indicate that two inhibitors are mutually antagonistic. Maximum antagonism is observed at a molar ratio of mF-8066 to NCCG-gp41 of 3:1, as expected given that NCCG-gp41 is a symmetric trimer with three symmetric binding sites for mF-8066.

Breadth of neutralizing activity of Fabs 8060, 8066 and 8068 against a standard reference panel of subtype B and C strains

On the basis of the neutralization data obtained with laboratory adapted HIV-1 strains, further studies were confined to the three most potent Fabs, 8060, 8066 and 8068. The breadth of HIV-1 neutralization activity of the Fabs in both mono- and bivalent formats was investigated using HIV pseudotyped with Envs from the Standard Reference Panels of HIV-1 subtypes B (Mascola et al., 2005) and C (Williamson et al., 2003) (Tables 3 and 4). A summary of the results in the form of a comparison of neutralization activity of the affinity-matured Fabs to the parental Fab 3674 is presented in Table 5.

Table 3.

Neutralization activity of monovalent and bivalent, affinity-matured Fabs against primary isolates of subtype B HIV-1.

| IC50 (nM)* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monovalent Fabs | Bivalent Fabs | |||||||

| Env | mF3674 | mF8068 | mF8060 | mF8066 | bF3674 | bF8068 | bF8060 | bF8066 |

| Ac10.0.29 | 2000 ± 680 | 520 ± 300 | 450 ± 290 | 340 ± 110 | 120 ± 47 | 130 ± 91 | 35 ± 25 | 85 ± 34 |

| WITO4160.33 | 1800 ± 820 | 270 ± 110 | 310 ± 170 | 180 ± 73 | 200 ± 83 | 43 ± 26 | 31 ± 17 | 47 ± 27 |

| THRO4156.18 | 6800 ± 2100 | 830 ± 270 | 550 ± 230 | 500 ± 110 | 2000 ± 470 | 340 ± 77 | 370 ± 96 | 210 ± 31 |

| CAAN5342.A2 | 2700 ± 480 | 1000 ± 360 | 580 ± 170 | 450 ± 83 | 340 ± 51 | 290 ± 58 | 210 ± 67 | 220 ± 45 |

| PVO.4 | NA | 1200 ± 690 | 2000 ± 1100 | 1100 ± 450 | NA | 450 ± 200 | 310 ± 160 | 210 ± 58 |

| TRO.11 | 2000 ± 470 | 710 ± 310 | 940 ± 460 | 610 ± 180 | 200 ± 25 | 170 ± 79 | 150 ± 57 | 150 ± 35 |

| RHPA4259.7 | 3000 ± 890 | 970 ± 430 | 710 ± 290 | 560 ± 180 | 940 ± 460 | 360 ± 160 | 270 ± 120 | 190 ± 77 |

| TRJO4551.58 | 990 ± 410 | 540 ± 320 | 460 ± 260 | 300 ± 100 | 1100 ± 420 | 140 ± 66 | 96 ± 48 | 93 ± 23 |

| 6535.3 | 9000 ± 4000 | 430 ± 230 | 740 ± 220 | 540 ± 170 | 550 ± 190 | 280 ± 110 | 310 ± 89 | 280 ± 77 |

| REJO4541.67 | 5900 ± 1500 | 3800 ± 1500 | 2600 ± 860 | 1400 ± 190 | 2300 ± 810 | 5200 ± 4200 | 1200 ± 400 | 1300 ± 180 |

| SC422661.8 | 2300 ± 1100 | 1100 ± 380 | 860 ± 310 | 450 ± 120 | 160 ± 45 | 170 ± 62 | 94 ± 35 | 110 ± 32 |

| QH0692.42 | 7100 ± 1900 | 770 ± 270 | 850 ± 380 | 700 ± 240 | 2000 ± 690 | 1800 ± 720 | 1400 ± 650 | 860 ± 230 |

NA, no activity. Neutralization activity was too weak to reliably determine an IC50.

Table 4.

Neutralization activity of monovalent and bivalent, affinity-matured Fabs against primary isolates of subtype C HIV-1.

| IC50 (nM)* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monovalent Fabs | Bivalent Fabs | |||||||

| Env | mF3674 | mF8068 | mF8060 | mF8066 | bF3674 | bF8068 | bF8060 | bF8066 |

| DU172.17 | 4900 ± 2500 | 140 ± 62 | 180 ± 82 | 93 ± 22 | 77 ± 31 | 72 ± 41 | 40 ± 17 | 48 ± 14 |

| ZM214M.PL15 | 6500 ± 1400 | 2200 ± 760 | 1200 ± 320 | 770 ± 130 | 550 ± 140 | 680 ± 270 | 230 ± 99 | 310 ± 48 |

| DU422.1 | 1300 ± 450 | 240 ± 96 | 240 ± 69 | 170 ± 40 | 93 ± 22 | 85 ± 30 | 57 ± 23 | 60 ± 18 |

| ZM197M.PB7 | NA | 890 ± 380 | 1700 ± 720 | 640 ± 160 | 1900 ± 660 | 410 ± 210 | 280 ± 110 | 300 ± 110 |

| ZM135M.PL10a | NA | 680 ± 220 | 840 ± 450 | 340 ± 110 | 340 ± 92 | 380 ± 120 | 200 ± 80 | 150 ± 45 |

| CAP210.2.00.E8 | NA | 490 ± 190 | 560 ± 230 | 310 ± 88 | 450 ± 120 | 150 ± 55 | 110 ± 33 | 83 ± 25 |

| CAP45.2.00.G3 | NA | 490 ± 140 | 610 ± 300 | 250 ± 110 | 500 ± 260 | 78 ± 53 | 53 ± 32 | 53 ± 33 |

| ZM249M.PL1 | 2900 ± 1100 | 690 ± 250 | 510 ± 230 | 370 ± 76 | 3000 ± 190 | 170 ± 110 | 66 ± 44 | 56 ± 23 |

| DU156.12 | 2500 ± 1100 | 290 ± 150 | 520 ± 240 | 190 ± 82 | 110 ± 46 | 60 ± 39 | 41 ± 23 | 46 ± 23 |

| ZM109F.PB4 | 800 ± 120 | 490 ± 54 | 340 ± 47 | 330 ± 93 | 260 ± 74 | 510 ± 130 | 350 ± 88 | 250 ± 85 |

| ZM53M.PB12 | 1000 ± 310 | 280 ± 91 | 450 ± 180 | 240 ± 51 | 150 ± 37 | 120 ± 48 | 97 ± 34 | 59 ± 20 |

| ZM233M.PB6 | 430 ± 210 | 90 ± 42 | 120 ± 64 | 73 ± 27 | 29 ± 10 | 35 ± 15 | 31 ± 13 | 27 ± 13 |

NA, no activity. Neutralization activity was too weak to reliably determine an IC50.

Table 5.

Improvement in potency and breadth of neutralizing activity of affinity-matured Fabs against diverse primary isolates from the standard subtypes B and C reference panels.

| Antibody | Panel B | Panel C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average ratio of IC50's relative to Fab 3674 | Fold decrease in IC50's relative to Fab 3674 | Neutralization breadth | Average ratio of IC50's relative to Fab 3674 | Fold decrease in IC50's relative to Fab 3674 | Neutralization breadth | |

| Monovalent | ||||||

| mF-3674 | 1 | 1 | 92 | 1 | 1 | 67 |

| mF-8068 | 0.31±0.19 | 1.6 - 20.7 | 100 | 0.25±0.18 | 1.6 - 35.3 | 100 |

| mF-8060 | 0.26±0.15 | 2.1 - 12.4 | 100 | 0.24±0.14 | 2.3 - 27.1 | 100 |

| mF-8066 | 0.17±0.09 | 3.2 - 16.8 | 100 | 0.16±0.12 | 2.4 - 53.0 | 100 |

| Bivalent | ||||||

| bF-3674 | 1 | 1 | 92 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| bF-8068 | 0.76±0.60 | 0.5 - 7.7 | 100 | 0.79±0.55 | 1.5 - 17.9 | 100 |

| bF-8060 | 0.43±0.24 | 1.3 - 11.3 | 100 | 0.51±0.39 | 0.8 - 45.4 | 100 |

| bF-8066 | 0.44±0.24 | 1.4 - 11.7 | 100 | 0.45±0.30 | 1.1 - 53.4 | 100 |

For the parental Fab 3674, the bivalent format is 10-20 fold more potent than the monovalent format in terms of neutralization activity across the panel of HIV-1 B and C clades. The differential in neutralization potency between bivalent and monovalent formats is reduced to 2-5 fold for the affinity-matured Fabs (Tables 3-4). Thus, the affinity-matured monovalent Fabs showed markedly improved potency relative to the parental monovalent Fab, compared to their bivalent counterparts. On average the IC50 value for the most potent Fab, mF-8066, was reduced by over 5 fold, when compared to the IC 50 of the parental mF-3674 (average ratio of 0.17±0.1 and 0.16±0.1 for HIV-1 subtype B and C panels, respectively), whereas the IC50 value for bF-8066 was only reduced by about 2 fold (average ratio of 0.44±0.2 and 0.45±0.3 for HIV-1 subtype B and C panels, respectively). All of the affinity-matured monovalent Fabs neutralized all pseudoviruses of the HIV-1 subtype B and C Env panels, which correspond to Tier2 contemporary primary isolates (Mascola et al., 2005). This is a significant improvement in breadth of neutralization, compared to the parental mF-3674, which neutralized 92% of pseudoviruses from the subtype B panel and only 67% of pseudoviruses from the subtype C panel.

With regard to the affinity-matured Fabs in bivalent format it is interesting to note that while the neutralization activity against many of the strains is only slightly better than that for the parental Fab bF-3674, there are four B strains (TRJO4551.58, THRO41456.18, WITO4160.33 and RHPA4259.7) and three C strains (ZM249M.PL1, CAP45.2.00.G3 and ZM197M.PB7) for which improvements in potency ranging from 5 to 50-fold are observed.

Temporal window of inhibition of viral infectivity

Using HXB2 Env-pseudotyped HIV infections that are synchronized and temperature-arrested at the CD4-bound step, we measured viral infectivity as a function of time of addition of fully inhibitory concentrations of antibody (Gustchina et al., 2008). The results are summarized in Table 6. We have previously shown that the neutralizing activity of bF-3674 had a comparable half-life to that of the C34 peptide, indicating that the two fusion inhibitors act at approximately the same stage of the fusion process (Gustchina et al., 2008). Although we were able to demonstrate that mF-3674 is able to inhibit HIV infection at the same stage of the fusion process as C34, bF-3674 and the affinity-matured Fabs, a very high concentration (approximately 5.5 μM) of mF-3674 was required to achieve such inhibition. Within a reasonable concentration range (≤2 μM) mF-3674 was essentially inactive post-CD4 engagement due to its poor IC50 in the post-attachment neutralization assay (Table 6). At a concentration of 2 μM the affinity-matured Fabs neutralized HIV-1 infection post-CD4 engagement with essentially the same half-lives (23-26 min) as C34 (Table 6), which may provide an explanation for the marked increase in their neutralization potency.

Table 6.

Comparison of pre-attachment (regular assay) and post-attachment (following CD4 engagement) HIV-1 HXB2 neutralization activity together with the half-lives of the inhibitor sensitive state obtained from assays synchronized at the CD4-bound step.

| Fusion inhibitor | Pre-attachment IC50 (nM) | Post-attachment IC50 (nM) | Half-life of inhibitor sensitive state (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| bF-3674 | 42±12 | 85±11 | 24±2 |

| mF-3674 | 630±160 | 1600±320 | 24±2 |

| mF-8068 | 160±72 | 820±68 | 26±3 |

| mF-8060 | 130±30 | 480±110 | 24±1 |

| mF-8066 | 82±29 | 400±61 | 23±2 |

| C34a | 6±2 | 4±0.4 | 23±1 |

C34 is a peptide fusion inhibitor derived from the C-HR of gp41 that targets the N-HR of gp41 (Chan et al., 1998a).

Concluding remarks

Affinity maturation of the broadly neutralizing Fab 3674 resulted in the generation of a panel of Fabs with improved binding affinity (ranging from 4 to 12-fold) towards the target antigen, NCCG-gp41 a chimeric construct that presents both the trimeric N-HR coiled-coil and the 6-HB (Table 1). However, not all of the Fabs selected on the basis of binding affinity possessed improved HIV-1 neutralization activity (Table 2). Thus higher binding affinity to the target antigen did not necessarily correlate with improved neutralization activity of the Fabs in the Env-pseudotyped HIV neutralization assays, providing evidence for the importance of kinetic restriction as a determinant of neutralization activity (Steger et al., 2006). However, for the three Fabs (8060, 8066 and 8068) selected for further study on the basis of their improved neutralization activity (Table 2), a marked decrease in IC50 values against HIV pseudotyped with the Envs of Tier2 viruses was observed (Table 3-5). The improved neutralization potency was on average more pronounced for the Fabs in monovalent than bivalent format. This observation raises the question as to whether the avidity advantage of the Fabs in bivalent format gives way to a potential kinetic and/or steric advantage for the monovalent Fabs once high affinity binding has been achieved. In addition, the breadth of neutralization activity of the monovalent Fabs was significantly enhanced (Tables 3-5). The monovalent Fabs mF-8060, mF-8066 and mF-8068 showed neutralization activity against 100% of HIVs pseudotyped with Tier2 Envs from the Standard Reference Panels of subtype B and C, whereas the parental monovalent Fab, mF-3674, neutralized 92% of the Panel B and only 67% of the Panel C pseudoviruses.

Materials and Methods

gp41-derived proteins

Expression, purification and folding of NCCG-gp41, N-terminal His-tagged N35CCG-N13, N34CCG, and 6-HB were performed as described previously (Louis et al., 2001; Louis et al., 2003; Louis et al., 2005). (The His-tag comprises 20 residues.) NCCG-gp41 is a chimeric protein comprising N35CCG (residues 546-580 of gp41 HIV-1 Env with Leu576, Gln577 and Ala578 substituted by Cys, Cys and Gly, respectively) fused onto the minimal thermostable ectodomain core of gp41 (Louis et al., 2001). Thus, each chain of NCCG-gp41 comprises N35CCG-N34-(L6)-C28, where N34 and C28 represent portions of the N-HR and C-HR regions of gp41 (residues 546-579 and 628-655, respectively) and L6 is a six-residue linker (SGGRGG). N35CCG-N13 is a 48 residue polypeptide that comprises N35CCG immediately followed by N13 (residues 546-548) (Louis et al., 2003). Three chains of NCCG-gp41, N35CCG-N13 and N34CCG are linked covalently via three intermolecular disulfide bridges. 6-HB is the minimal thermostable ectodomain core of gp41 comprising N34-(L6)-C28 (Tan et al., 1997). Single (m81-89) and double (m90-m97) alanine mutants of His-tagged 6-HB involving surface exposed residues of the N-HR that lie in a shallow groove between two C-HR helices were as follows (Gustchina et al., 2007): m81, Q550A; m82, N553A; m83, R557A; m84, E560A; m85, H564A; m86, Q576A; m87, W571A; m88, K574A; m89, Q575A; m90, Q550A/N553A; m91, N553A/R557A; m92, R557A/E560A; M93, E560A/H564A; m94, H564A/Q567A; m95, Q567A/W571A; m96, W571A/K574A; m97, K574A/Q575A. C-terminal His-tagged 5-helix (Root et al., 2001) was expressed and purified as described previously (Gustchina et al., 2007). All proteins underwent a final purification step using size exclusion chromatography and were characterized by gel electrophoresis and ES-MS.

Affinity maturation of Fab 3674 by exchange of the CDR-H2 loop

DNA encoding Fab 3674 was subcloned from an expression vector into a phagemid vector based on pMorph23 (US Patent 6,753,136). The heavy chain CDR-H2 sequence was removed by restriction digest and a repertoire of CDR-H2 sequences was cloned into this construct. The CDR-H2 repertoire was designed according to the respective amino acid distribution at each position of naturally occurring, human rearranged antibody genes using trinucleotides for gene synthesis (Virnekas et al., 1994; Knappik et al., 2000; Rothe et al., 2008). Electroporation into E. coli Top10F′ competent cells (Invitrogen) resulted in a library of about 1.3×106 antibodies with different heavy chain CDR-H2 loops.

Two rounds of panning were performed on NCCG-gp41 coupled magnetic beads (M-450 Epoxy, Invitrogen) applying increased washing stringency compared to the standard panning conditions used for selection of the parental Fab 3674 (Gustchina et al., 2007). After the second round of panning, the enriched pool of Fab genes was subcloned into the expression vector pMORPHx9_Fab-MH for the expression of myc-his6 tagged monovalent Fab fragments (Rauchenberger et al., 2003). E. coli TG1F- (TG1 without the F plasmid) was transformed with the ligation mixture and plated. 384 colonies were randomly picked and transferred to a 384-well microtiter plate. Then 368 clones were tested for binding to NCCG-gp41 coupled beads by FLISA on a CDS8200 instrument (Applied Biosystems). Briefly, NCCG-gp41 coupled beads, Fab containing E. coli lysates and fluorescence-labeled anti-human Fab secondary antibody were mixed and incubated for one hour. Fluorescence on beads settled at the bottom of the wells indicated positive lysates. More than 200 hits were obtained in the primary screening. The 10 clones with the best signal and in addition 10 clones selected at random were sequenced and 12 unique antibodies were found. These were expressed and purified via the his6 tag by affinity chromatography. Specific binding to NCCG-gp41 was confirmed by ELISA and the 10 antibodies with the highest signal on NCCG-gp41 were selected for further characterization. These Fabs were also subcloned and expressed in the bivalent Fab-dHLX-MH format (Jarutat et al., 2006; Gustchina et al., 2007). Composition and purity of antibodies were confirmed by SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis against the panel of gp41 ectodomain-derived constructs was carried out as described previously (Gustchina et al., 2007).

Determination of Fab affinities for NCCG-gp41 using Solution Equilibrium Titration (SET)

Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) based affinity determination by solution equilibrium titration was performed essentially as described previously (Haenel et al., 2005; Steidl et al., 2008).

Cell lines and molecular clones

The HIV-1 expression plasmid SG3Denv (catalog no. 11051), the Standard Reference panel of Subtype B HIV-1 Env clones (catalog no. 11227), the Standard Reference panel of Subtype C HIV-1 Env clones (catalog no. 11326), the HIV-1 Env molecular clone pCAGGS SF162 gp160 (catalog no. 10463), the murine leukemia virus (MuLV) Env clone SV-A-MLV-env (catalog no. 1065), the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) G glycoprotein clone pHEF-VSVG (catalog no. 4693), and indicator cells TZM-b1 (or JC53BL-13, catalog no. 8129) were obtained from National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. 293T cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Gp160 expression plasmids pSVIII HBXc2, 89.6 and JR CSF were provided by Dr. J.Sodroski, Department of Cancer Immunology and AIDS, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Sullivan et al., 1995; Karlsson et al., 1996), and the NL4-3 gp160 expression plasmid pHenv was provided by Dr. E. Freed, HIV Drug Resistance Program, NCI (Freed et al., 1989). Gp160 expression plasmids pSVIII BaL01 and BaL26 (Li et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006) were provided by Dr. J. Mascola, BSL-3 Core Virology Laboratory, Vaccine Research Center, NIAID.

Env-pseudotyped HIV-1 preparation

Env-pseudotyped HIV-1 stocks were prepared essentially as described (Li et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006; Gustchina et al., 2007). Exponentially dividing 293T cells were cotransfected using FUGENE6 transfection kit (Roche, Nutley, NJ) with the Env-deficient HIV-1 expression plasmid SG3Δenv and an Env-expressing plasmid in ratios proportional to their individual sizes (∼16 μg total DNA per 50 to 80% confluent T-150 culture flask). Culture supernatants were collected 2 days post-transfection, filtered through 0.45 μM filter, and stored at -80 °C.

HIV-1 neutralization assay

Env-pseudotyped HIV neutralization assays were performed essentially as described (Li et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006; Gustchina et al., 2007). Serial dilutions of Fabs in phosphate buffer saline (10 ml) were added to Env-pseudotyped virus (in 40 μl Dulbecco modified Eagle medium plus 10% fetal calf serum), followed by the addition of freshly trypsinized TZM-bl indicator cells (JC53BL-13), a HeLa-derived cell line genetically modified to constitutivelyexpress CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 (10,000 cells in 20 μL of the same medium). After incubation at 37 °C overnight, 150 μL of fresh growth medium was added. Approximately 48 h postinfection cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured using the BrightGlo luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) with a Synergy2 luminescence microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Pseudovirus stocks were diluted to yield approximately 200 to 1000-fold increase of luminescence for an infected control over the uninfected control. IC50 values were obtained by a non-linear least-squares fit of a simple dose-activity relationship, given by % infection = 100/(1+[Fab]/IC50), to the experimental data.

Analysis of neutralizing activity of mF-8066 in combination with NCCG-gp41

Neutralizing activity of multiple constant-ratio combinations of mF-8066 antibody and NCCG-gp41 protein were tested in serial dilutions in HXB2 Env-pseudotyped HIV neutralization assays. The data were analyzed as described previously (Gustchina et al., 2006).

Post-attachment HIV-1 neutralization assay

Neutralizing activity of Fabs after attachment of pseudovirus to the target cells following CD4 engagement was measured as described previously (Gustchina et al., 2008).

Synchronized and “time-of-addition” Env-pseudotyped HIV neutralization assay

Synchronized viral infection assays in the context of the HXB2 Env-pseudotyped virus neutralization assay were performed using the spinoculation technique (O'Doherty et al., 2000; Reeves et al., 2002) as described previously (Gustchina et al., 2008). The infectivity (y) as a function of the time post-infection (t) of addition of the Fabs was fit to a sigmoidal function given by y =ymax/[1+e(t1/2−t)/k] where t1/2 is the half-life of the inhibitor-sensitive state of Env and k is a constant that determines the shape of the sigmoidal curve (Reeve s et al., 2002).

Figure 2.

Dose-response curves for antiviral activity of the monovalent Fab mF-8066 against (A) diverse laboratory-adapted HIV-1 subtype B strains and (B) MuLV and VSV (negative controls) in an Env-pseudotyped virus neutralization assay.

Acknowledgments

We thank Annie Aniana for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Intramural program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, and by the AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health (to G.M.C. and C.A.B.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berger EA, Murphy PM, Farber JM. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley CA, Louis JM, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Design of a novel peptide inhibitor of HIV fusion that disrupts the internal trimeric coiled-coil of gp41. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14238–14245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey M, Cai M, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Covell DG, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Three-dimensional solution structure of the 44 kDa ectodomain of SIV gp41. EMBO J. 1998;17:4572–4584. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DC, Chutkowski CT, Kim PS. Evidence that a prominent cavity in the coiled coil of HIV type 1 gp41 is an attractive drug target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998a;95:15613–15617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM, Kim PS. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DC, Kim PS. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell. 1998b;93:681–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Greenberg ML, Bolognesi DP, Matthews TJ. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to the core of fusion-active glycoprotein 41. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16:2037–2041. doi: 10.1089/088922200750054765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Talalay P. Generalized equations for the analysis of inhibitions of Michaelis-Menten and higher-order kinetic systems with two or more mutually exclusive and nonexclusive inhibitors. Eur J Biochem. 1981;115:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb06218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enz Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry V, Zhang MY, Sidorov IA, Louis JM, Harris I, Dimitrov AS, Bouma P, Cham F, Choudhary A, Rybak SM, Fouts T, Montefiori DC, Broder CC, Quinnan GV, Jr, Dimitrov DS. Cross-reactive HIV-1 neutralizing monoclonal antibodies selected by screening of an immune human phage library against an envelope glycoprotein (gp140) isolated from a patient (R2) with broadly HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies. Virology. 2007;363:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert DM, Kim PS. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001a;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert DM, Kim PS. Design of potent inhibitors of HIV-1 entry from the gp41 N-peptide region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001b;98:11187–11192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201392898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert DM, Malashkevich VN, Hong LH, Carr PA, Kim PS. Inhibiting HIV-1 entry: discovery of D-peptide inhibitors that target the gp41 coiled-coil pocket. Cell. 1999;99:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert DM, Shi Y, Kim S, Welch BD, Kang E, Poff ES, Kay MS. Characterization of the steric defense of the HIV-1 gp41 N-trimer region. Protein Sci. 2008;17:2091–2100. doi: 10.1110/ps.038273.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed EO, Myers DJ, Risser R. Mutational analysis of the cleavage sequence of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein precursor gp160. J Virol. 1989;63:4670–4675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4670-4675.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta RA, Wild CT, Weng Y, Weiss CD. Capture of an early fusion-active conformation of HIV-1 gp41. Nature Struct Biol. 1998;5:276–279. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo SA, Finnegan CM, Viard M, Raviv Y, Dimitrov A, Rawat SS, Puri A, Durell S, Blumenthal R. The HIV Env-mediated fusion reaction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1614:36–50. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding H, Zaitseva M, de Rosny E, King LR, Manischewitz J, Sidorov I, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Dimitrov DS, Weiss CD. Dissection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry with neutralizing antibodies to gp41 fusion intermediates. J Virol. 2002;76:6780–90. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6780-6790.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustchina E, Bewley CA, Clore GM. Sequestering of the prehairpin intermediate of gp41 by peptide N36Mut(e,g) potentiates the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralizing activity of monoclonal antibodies directed against the N-terminal helical repeat of gp41. J Virol. 2008;82:10032–10041. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01050-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustchina E, Louis JM, Bewley CA, Clore GM. Synergistic inhibition of HIV-1 envelope-mediated membrane fusion by inhibitors targeting the N and C-terminal heptad repeats of gp41. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustchina E, Louis JM, Lam SN, Bewley CA, Clore GM. A Monoclonal Fab Derived From a Human Non-Immune Phage Library Reveals a New Epitope on gp41 and Neutralizes Diverse HIV-1 Strains. J Virol. 2007;81:12946–12953. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01260-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenel C, Satzger M, Ducata DD, Ostendorp R, Brocks B. Characterization of high-affinity antibodies by electrochemiluminescence-based equilibrium titration. Anal Biochem. 2005;339:182–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger AE, Kim S, Welch BD, Kay MS. Steric accessibility of the HIV-1 gp41 N-trimer region. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12567–12572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarutat T, Frisch C, Nickels C, Merz H, Knappik A. Isolation and comparative characterization of Ki-67 equivalent antibodies from the HuCAL phage display library. Biol Chem. 2006;387:995–1003. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Lin K, Lu M. A conformation-specific monoclonal antibody reacting with fusion-active gp41 from the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1998;72:10213–10217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10213-10217.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Lin K, Strick N, Neurath AR. HIV-1 inhibition by a peptide. Nature. 1993;365:113. doi: 10.1038/365113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson GB, Gao F, Robinson J, Hahn B, Sodroski J. Increased envelope spike density and stability are not required for the neutralization resistance of primary human immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1996;70:6136–6142. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6136-6142.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappik A, Ge L, Honegger A, Pack P, Fischer M, Wellnhofer G, Hoess A, Wolle J, Pluckthun A, Virnekas B. Fully synthetic human combinatorial antibody libraries (HuCAL) based on modular consensus frameworks and CDRs randomized with trinucleotides. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:57–86. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar T, von Ruden T. Antibody discovery: phage display. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002;13:598–602. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Gao F, Mascola JR, Stamatatos L, Polonis VR, Koutsoukos M, Voss G, Goepfert P, Gilbert P, Greene KM, Bilska M, Kothe DL, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Wei X, Decker JM, Hahn BH, Montefiori DC. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2005;79:10108–10125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10108-10125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Svehla K, Mathy NL, Voss G, Mascola JR, Wyatt R. Characterization of antibody responses elicited by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate trimeric and monomeric envelope glycoproteins in selected adjuvants. J Virol. 2006;80:1414–1426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1414-1426.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis JM, Bewley CA, Clore GM. Design and properties of NCCG-gp41, a chimeric gp41 molecule with nanomolar HIV fusion inhibitory activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29485–29489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis JM, Bewley CA, Gustchina E, Aniana A, Clore GM. Characterization and HIV-1 fusion inhibitory properties of monoclonal Fabs obtained from a human non-immune phage library selected against diverse epitopes of the ectodomain of HIV-1 gp41. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:945–951. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis JM, Nesheiwat I, Chang L, Clore GM, Bewley CA. Covalent trimers of the internal N-terminal trimeric coiled-coil of gp41 and antibodies directed against them are potent inhibitors of HIV envelope-mediated cell fusion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20278–20285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luftig MA, Mattu M, Di Giovine P, Geleziunas R, Hrin R, Barbato G, Bianchi E, Miller MD, Pessi A, Carfi A. Structural basis for HIV-1 neutralization by a gp41 fusion intermediate-directed antibody. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:740–747. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascola JR, D'Souza P, Gilbert P, Hahn BH, Haigwood NL, Morris L, Petropoulos CJ, Polonis VR, Sarzotti M, Montefiori DC. Recommendations for the design and use of standard virus panels to assess neutralizing antibody responses elicited by candidate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccines. J Virol. 2005;79:10103–10107. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10103-10107.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews T, Salgo M, Greenberg M, Chung J, DeMasi R, Bolognesi D. Enfuvirtide: the first therapy to inhibit the entry of HIV-1 into host CD4 lymphocytes. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:215–225. doi: 10.1038/nrd1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikyan GB, Egelhofer M, von Laer D. Membrane-anchored inhibitory peptides capture human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 conformations that engage the target membrane prior to fusion. J Virol. 2006;80:3249–3258. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3249-3258.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD, Geleziunas R, Bianchi E, Lennard S, Hrin R, Zhang H, Lu M, An Z, Ingallinella P, Finotto M, Mattu M, Finnefrock AC, Bramhill D, Cook J, Eckert DM, Hampton R, Patel M, Jarantow S, Joyce J, Ciliberto G, Cortese R, Lu P, Strohl W, Schleif W, McElhaugh M, Lane S, Lloyd C, Lowe D, Osbourn J, Vaughan T, Emini E, Barbato G, Kim PS, Hazuda DJ, Shiver JW, Pessi A. A human monoclonal antibody neutralizes diverse HIV-1 isolates by binding a critical gp41 epitope. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14759–14764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506927102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JD, Kinkead H, Brunel FM, Leaman D, Jensen R, Louis JM, Maruyama T, Bewley CA, Bowdish K, Clore GM, Dawson PE, Frederickson S, Mage RG, Richman DD, Burton DR, Zwick MB. Antibody elicited against the gp41 N-heptad repeat (NHR) coiled-coil can neutralize HIV-1 with modest potency but non-neutralizing antibodies also bind to NHR mimetics. Virology. 2008;377:170–183. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty U, Swiggard WJ, Malim MH. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 spinoculation enhances infection through virus binding. J Virol. 2000;74:10074–10080. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10074-10080.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluckthun A. Mono- and bivalent antibody fragments produced in Escherichia coli: engineering, folding and antigen binding. Immunol Rev. 1992;130:151–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauchenberger R, Borges E, Thomassen-Wolf E, Rom E, Adar R, Yaniv Y, Malka M, Chumakov I, Kotzer S, Resnitzky D, Knappik A, Reiffert S, Prassler J, Jury K, Waldherr D, Bauer S, Kretzschmar T, Yayon A, Rothe C. Human combinatorial Fab library yielding specific and functional antibodies against the human fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38194–38205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves JD, Gallo SA, Ahmad N, Miamidian JL, Harvey PE, Sharron M, Pohlmann S, Sfakianos JN, Derdeyn CA, Blumenthal R, Hunter E, Doms RW. Sensitivity of HIV-1 to entry inhibitors correlates with envelope/coreceptor affinity, receptor density, and fusion kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16249–16254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252469399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root MJ, Kay MS, Kim PS. Protein design of an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. Science. 2001;291:884–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1057453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root MJ, Steger HK. HIV-1 gp41 as a target for viral entry inhibition. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:1805–1825. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe C, Urlinger S, Lohning C, Prassler J, Stark Y, Jager U, Hubner B, Bardroff M, Pradel I, Boss M, Bittlingmaier R, Bataa T, Frisch C, Brocks B, Honegger A, Urban M. The human combinatorial antibody library HuCAL GOLD combines diversification of all six CDRs according to the natural immune system with a novel display method for efficient selection of high-affinity antibodies. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:1182–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger HK, Root MJ. Kinetic dependence to HIV-1 entry inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25813–25821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidl S, Ratsch O, Brocks B, Durr M, Thomassen-Wolf E. In vitro affinity maturation of human GM-CSF antibodies by targeted CDR-diversification. Mol Immunol. 2008;46:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan N, Sun Y, Li J, Hofmann W, Sodroski J. Replicative function and neutralization sensitivity of envelope glycoproteins from primary and T-cell line-passaged human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. J Virol. 1995;69:4413–4422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4413-4422.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K, Liu J, Wang J, Shen S, Lu M. Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12303–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virnekas B, Ge L, Pluckthun A, Schneider KC, Wellnhofer G, Moroney SE. Trinucleotide phosphoramidites: ideal reagents for the synthesis of mixed oligonucleotides for random mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5600–5607. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–30. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild C, Oas T, McDanal C, Bolognesi D, Matthews T. A synthetic peptide inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus replication: correlation between solution structure and viral inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10537–10541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild CT, Shugars DC, Greenwell TK, McDanal CB, Matthews TJ. Peptides corresponding to a predictive alpha-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9770–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson C, Morris L, Maughan MF, Ping LH, Dryga SA, Thomas R, Reap EA, Cilliers T, van Harmelen J, Pascual A, Ramjee G, Gray G, Johnston R, Karim SA, Swanstrom R. Characterization and selection of HIV-1 subtype C isolates for use in vaccine development. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:133–144. doi: 10.1089/088922203762688649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang MY, Vu BK, Choudhary A, Lu H, Humbert M, Ong H, Alam M, Ruprecht RM, Quinnan G, Jiang S, Montefiori DC, Mascola JR, Broder CC, Haynes BF, Dimitrov DS. Cross-reactive human immunodeficiency virus type 1-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody that recognizes a novel conformational epitope on gp41 and lacks reactivity against self-antigens. J Virol. 2008;82:6869–6879. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00033-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]