Abstract

Objectives To compare fertility rates after the three methods of managing early miscarriage in women recruited to the MIST (miscarriage treatment) randomised controlled trial.

Setting Early pregnancy clinics of acute hospitals in the south west region of England.

Participants 1199 women who had had an early miscarriage (<13 weeks) confirmed by scan.

Intervention Expectant, medical, or surgical management.

Main outcome measures Self reported pregnancy rates and live birth rates.

Results Of 1199 women recruited to the trial, 1128 consented to follow-up. Of these, 762 women replied giving pregnancy details (68% response rate). Respondents were representative of the trial participants. The live birth rate five years after the index miscarriage was similar in the three management groups: 177/224 (79%, 95% confidence interval 73% to 84%) in the expectant management group, 181/230 (79%, 73% to 84%) in the medical group, and 192/235 (82%, 76% to 86%) in the surgical group. There was also no significant difference according to previous birth history. Older women and those with previous miscarriages were significantly less likely to subsequently give birth.

Conclusion Method of miscarriage management does not affect subsequent pregnancy rates with around four in five women giving birth within five years of the index miscarriage. Women can be reassured that long term fertility concerns need not affect their choice of miscarriage management.

Trial registration National Research Register N0467011677/N0467073587.

Introduction

For decades the standard treatment of women who experienced an early miscarriage was evacuation of retained products of conception.1 This was increasingly questioned,2 3 4 and now women are usually offered expectant (watch and wait, no active intervention)5 6 and medical7 8 management as well. Trials have suggested that all three methods are probably equivalent in terms of gynaecological infection,9 10 11 12 13 including the largest trial, which recruited around 1200 women (the miscarriage treatment (MIST) trial).14

Little published evidence, however, has assessed the effect of management method on subsequent fertility—a key issue for women and those responsible for their care. One small trial found no significant difference in subsequent fertility rates up to 24 months after an index miscarriage.15 We examined subsequent fertility rates in women randomised to the three arms of the larger MIST trial. Our primary aim was to establish if the management method for early miscarriage affects subsequent fertility. We also assessed the effects of age, previous miscarriage, and previous birth history.

Methods

The methods of the MIST trial are described in detail elsewhere.14 Briefly, the trial recruited women who had had an early (<13 weeks’ gestation) miscarriage between May 1997 and December 2001 from early pregnancy assessment clinics in the south west of England. They were randomly allocated to surgical evacuation of retained products of conception, medical treatment with mifepristone or misoprostol, or both, or expectant management. The clinical and economic results of the trial are reported elsewhere,14 16 as are women’s experiences.17

A preliminary survey involving the general practitioners of 99 of the original participants was undertaken to assess ease of contacting women. This achieved a response rate of 79%. Subsequently, in 2005-7, women who completed the original trial and their general practitioners were sent a postal questionnaire; the only exclusions were women who opted out of any follow-up or for whom the original general practitioner advised against follow-up. The two items of primary interest were time to next pregnancy and time to next live birth. When questionnaire packs were returned “addressee unknown,” we used the Office for National Statistics tracing services to identify the woman’s current health authority information. Health authorities were then requested to forward a pack to her general practitioner for subsequent forwarding. The mailing period extended over two years because of the time delay in obtaining tracing authorisation from all four countries in the United Kingdom. Women’s general practitioners were also asked for details of subsequent pregnancies; women’s replies were used if there were discrepancies between the two.

The questionnaire was sent with a consent form, covering letter, and freepost envelope for return. We estimated from published studies18 19 20 that the MIST trial cohort would give 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of about 0.7 in fertility rates between any two of the management methods.

To assess representativeness, we compared respondents and non-respondents (including those not consenting to follow-up) using either χ2 test or Student’s t test. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed and log rank tests used to compare fertility rates for the following possible predictors: management method (expectant, medical, surgical); any previous birth after 24 weeks’ gestation (yes, no); previous miscarriages (0, 1, 2, ≥3); and age at recruitment to the MIST trial (<25, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39, ≥40). Significant (P<0.05) predictors were included in a proportional hazards multivariate model. Separate analyses were undertaken for fertility (not shown) and for live births. Quoted denominators vary slightly because of occasional non-response to individual questions. Sensitivity analyses considered how the results might be affected by extreme assumptions about the non-respondents.

Results

Of the 1199 women recruited to the original trial, we sent questionnaires to 1128 women and their GPs. For the 71 remaining we had no consent from the patient or her original general practitioner for such follow-up. Questionnaires providing subsequent pregnancy details were returned for 762 women (68% response rate), from the woman herself, her general practitioner, or both.

With data recorded as part of the original MIST trial protocol, table 1 compares respondents to this follow-up survey with non-respondents (including the 71 not sent a questionnaire as well as those not returning questionnaires). The respondents were broadly representative of the MIST trial population, with no significant differences between respondents and non-respondents.

Table 1.

Comparison of respondents and non-respondents to follow-up survey (using data collected as part of original MIST trial protocol). Figures are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Comparative factor | Respondents | Non-respondents | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomisation group: | |||

| Expectant | 247 (32.4) | 147 (34.1) | 0.71 |

| Medical | 252 (33.1) | 145 (33.6) | |

| Surgical | 263 (34.5) | 139 (32.3) | |

| Year entered trial: | |||

| 1997 | 83 (10.9) | 46 (10.7) | 0.18 |

| 1998 | 210 (27.6) | 146 (33.9) | |

| 1999 | 206 (27.0) | 114 (26.5) | |

| 2000 | 143 (18.8) | 68 (15.8) | |

| 2001 | 120 (15.7) | 57 (13.2) | |

| Mean (SD) age at recruitment (years) | 31.2 (6.1) | 30.1 (6.7) | 0.23 |

| Vaginal bleeding at recruitment | 650 (85.4) | 360 (83.5) | 0.38 |

| Abdominal pain at recruitment | 388 (51.1) | 243 (56.5) | 0.07 |

| Mean (SD) haemoglobin concentration at recruitment (g/l) | 132 (9.5) | 131 (10) | 0.13 |

| Any previous pregnancy loss | 269 (35.4) | 157 (36.8) | 0.65 |

| Any ERPC* | 284 (37.3) | 156 (36.2) | 0.71 |

*Evacuation of retained products of conception during management of index miscarriage, irrespective of actual randomised allocation.

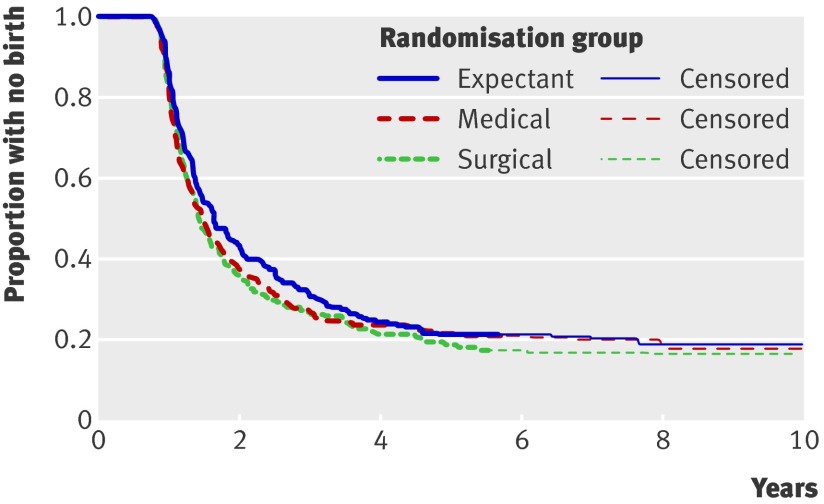

Among the survey respondents, 634/758 (84%, 95% confidence interval 81% to 86%) reported a subsequent pregnancy since the index miscarriage, with 565/689 (82%, 79% to 85%) having a live birth. Time to subsequently giving birth was similar in the three randomised groups (fig 1; P=0.41). Five years after the index miscarriage 177/224 (79%, 73% to 84%) of those who had been randomised to expectant management had given birth, compared with 181/230 (79%, 73% to 84%) in the medical group and 192/235 (82%, 76% to 86%) in the surgical group.

Fig 1 Time (years) to live birth after index miscarriage classified by type of randomly allocated management method (expectant, medical, surgical)

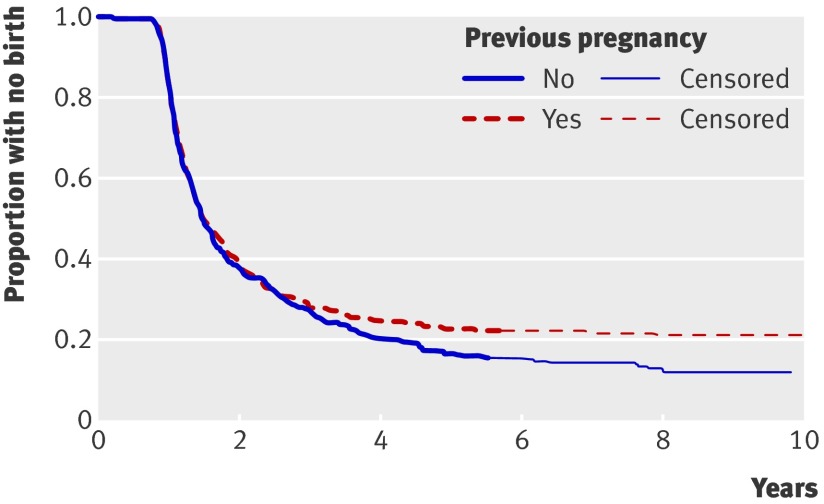

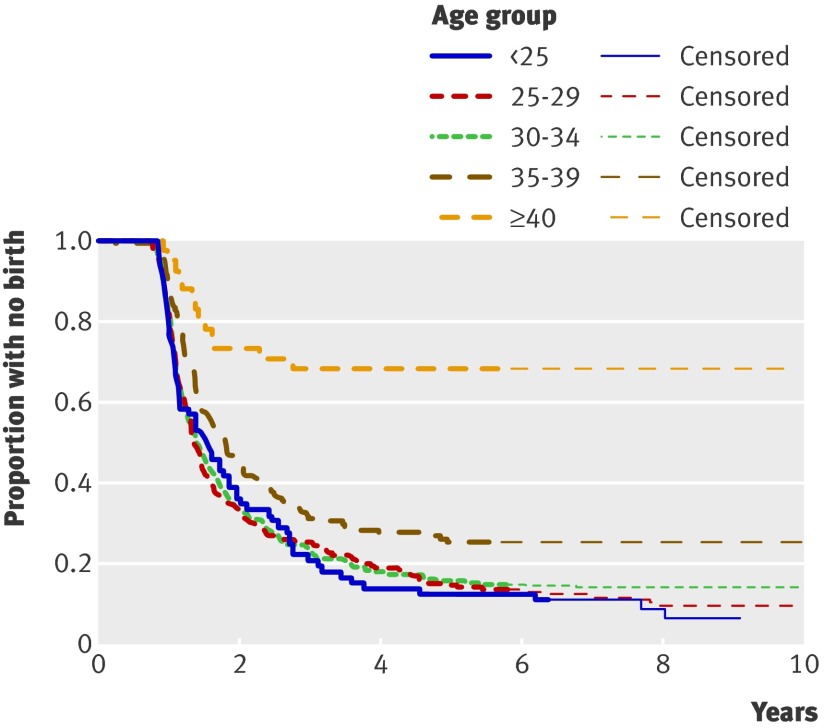

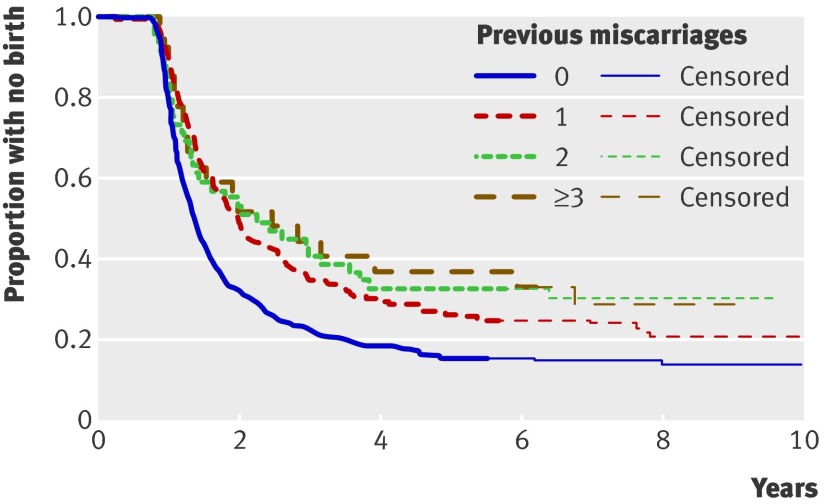

Having had one or more previous pregnancies before the index miscarriage did not significantly predict time to giving birth (fig 2; P=0.10). Time to subsequent birth, however, was predicted by maternal age (fig 3; P<0.001) and having had a previous miscarriage (fig 4; P<0.001). Proportional hazards regression confirmed that both age and previous miscarriages were significantly predictive, even when adjusted for each other (table 2). Five years after the index miscarriage, 378/447 (85%) of those women with no previous miscarriage had given birth; the corresponding figures for 1, 2, and ≥3 previous miscarriages were 122/166 (74%), 33/49 (67%), and 14/24 (58%), respectively. Analysis of time to first pregnancy produced similar findings to that of first birth (results not shown).

Fig 2 Time (years) to live birth after index miscarriage classified by previous pregnancy (yes/no)

Fig 3 Time (years) to live birth after index miscarriage classified by maternal age

Fig 4 Time (years) to live birth after index miscarriage classified by previous miscarriages (0, 1, 2, ≥3)

Table 2.

Proportional hazards regression for time to first birth

| Predictor | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age group: | ||

| <25 | 1.00* | <0.001 |

| 25-29 | 0.98 (0.74 to 1.31) | |

| 30-34 | 0.96 (0.73 to 1.27) | |

| 35-39 | 0.69 (0.50 to 0.94) | |

| ≥40 | 0.21 (0.12 to 0.38) | |

| Previous miscarriages: | ||

| 0 | 1.00* | 0.006 |

| 1 | 0.76 (0.62 to 0.93) | |

| 2 | 0.68 (0.48 to 0.97) | |

| ≥3 | 0.63 (0.40 to 1.01) | |

*Reference category.

The reported results relate only to survey respondents. To illustrate extreme sensitivity analysis scenarios, if none of the non-respondents had given birth within five years of the index miscarriage then the overall percentage having such a birth would reduce from 79.8% to 49.1%; conversely if all the non-respondents had given birth the figure would increase to 87.6%. In both cases there would still be no significant differences between management groups. Significant differences would arise only if the relative birth rate for non-respondents compared with respondents was different within the management groups.

Discussion

In this large study based on a randomised trial we found that the method of management of miscarriage did not affect subsequent fertility, with around 80% of women having a live birth within five years of the index miscarriage. This rate was somewhat lower than that reported in a previous trial that randomised women to expectant or surgical management.15 Blohm et al surveyed 127 women (28 excluded for various reasons) two to three years after the index miscarriage and obtained an 89% response rate. There was a non-significant difference in subsequent fertility rates up to 24 months after the index miscarriage of about 4% in favour of expectant compared with surgical management.

Previous cohort studies have found subsequent pregnancy rates of about 70%, but over different time scales (undefined,18 18 months,19 five years20). The only trial found a 75% rate at 12 months and a 90% rate at 24 months.15 The rate in our study of about 60% at two years and 80% at five years is comparable but will have been influenced downwards by those respondents (included in our analysis) who did not want to conceive again after their miscarriage. It is likely, however, that our figure of four in five women eventually conceiving is representative of those women included in the original trial as the live birth curve flattens after about six years; women might find this high success rate reassuring in the initial stages after a miscarriage. Our respondents were similar to trial participants in terms of age, previous pregnancy loss, miscarriage type, clinical symptoms, surgical intervention, and management method. It is conceivable that one management method might cause very early future losses that this type of questionnaire study might not detect, but this seems unlikely, given that women would be sensitised to a future pregnancy, have access to the wide availability of pregnancy tests, and would have recorded such losses on the questionnaire.

The low birth rate we observed in older women is not surprising because fertility reduces naturally with age, and some older women would probably not have planned the index pregnancy nor perhaps want to conceive again. Our results confirm that women experiencing three or more miscarriages might have problems subsequently giving birth and thus need to be investigated for a recurrent cause.21

Women can be reassured that after miscarriage their chance of a subsequent live birth is high, irrespective of management method. This information should complement the information that they might want to receive17 to enable them to choose which management method is personally preferable, bearing in mind the clinical14 and economic16 differences.

What is already known on this topic

All three of the methods of management of early miscarriage currently offered to women in the UK and elsewhere are probably equivalent in terms of gynaecological infection

Little published evidence has assessed the effect of management method on subsequent fertility—a key issue for women and those who care for them

What this study adds

Type of management method does not affect subsequent fertility, with around 80% of women having a live birth within five years of the index miscarriage

We thank all the women who participated in the study and to trustees of the Claire Wand Fund for providing funding.

Contributors: LFPS designed the study and is guarantor. PDE carried out the statistical analysis. All contributed to paper.

Funding: This study was funded by the BMA Claire Wand Fund. All authors are independent from the body providing funding for this research. Sponsorship and research governance management for this study was provided by East Somerset Research Consortium.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was given by South West MREC in December 2001: MREC/01/6/90.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3827

References

- 1.Clayton SG. Gynaecology by ten teachers. Edward Arnold, 1989.

- 2.Smith LFP. Should we intervene in uncomplicated miscarriage? BMJ 1993;306:1540-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forbes K. Management of first trimester spontaneous abortions. BMJ 1995;310:1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ankum WM, Van der Veen F. Management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet 1995;345:1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickey RP. Management of uncomplicated miscarriage. Patients’ safe with expectant management. BMJ 1993;307:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen S, Hahlin M. Expectant management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet 1995;345:84-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Refaey H, Hinshaw K, Henshaw R, Smith N, Templeton A. Medical management of missed abortion and anembryonic pregnancy. BMJ 1992;305:1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henshaw R, Cooper K. El-Refaey H, Smith N, Templeton A. Medical management of miscarriage: non-surgical uterine evacuation of incomplete and inevitable spontaneous abortion. BMJ 1993;306:8944-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chipchase J, James D. Randomised trial of expectant versus surgical management of spontaneous miscarriage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:840-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielson S, Hahlin M, Platz-Christensen J. Randomised trial comparing expectant with medical management for first trimester miscarriages. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999;106:804-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson N, Priestnall M, Marsay T, Ballard P, Watters J. A randomised trial evaluating pain and bleeding after a first trimester miscarriage treated surgically or medically. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Biol 1997;72:213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung TK, Lee DT, Cheung LP, Haines CJ, Chang AM. Spontaneous abortion: a randomised, controlled trial comparing surgical evacuation with conservative management using misoprostol. Fertil Steril 1998;71:1054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geyman JP, Oliver LM, Sullivan SD. Expectant, medical, or surgical treatment of spontaneous abortion in first trimester of pregnancy? A pooled quantitative literature evaluation. J Am Board Fam Pract 1999;12:55-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trinder J, Brocklehurst P, Porter R, Read, M, Vyas S, Smith L. Management of miscarriage: expectant, medical or surgical? Results of a randomised controlled trial (the MIST trial). BMJ 2006;332:1235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blohm F, Hahlin M, Nielsen S, Milsom I. Fertility after a randomised trial of spontaneous abortion managed by surgical evacuation or expectant treatment. Lancet 1997;349:995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrou S, Trinder J, Brocklehurst P, Smith L. Economic evaluation of alternative management methods of first-trimester miscarriage based on results from the MIST trial. BJOG 2006;113:879-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith LF, Frost J, Levitas R, Bradley H, Garcia J. Women’s experiences of three early miscarriage management options: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2006:56;198-205. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.David TJ, Smith CM. Outcome of pregnancy after spontaneous abortion. BMJ 1980:280;447-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Kaplan B, Pardo J, Rabinerson D, Fisch B, Neri A. Future fertility following conservative management of complete abortion. Hum Reprod 1996;11:92-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin S, Amsterdam E, Brook I, Insler V. The effect of missed abortion and spontaneous abortion on the fate of subsequent pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1979;58:371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green-top guideline no 17: the investigation and treatment of couples with recurrent miscarriage. In: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green-top guideline compendium. RCOG Press, 2003.