Abstract

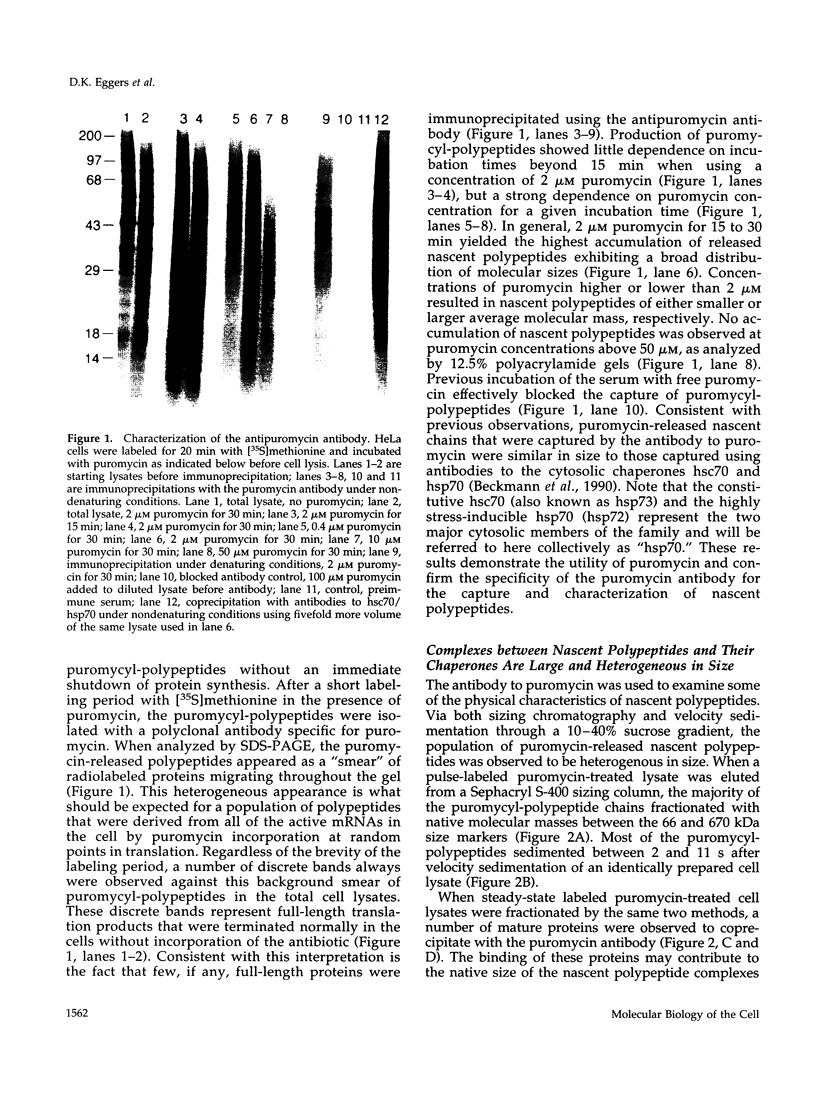

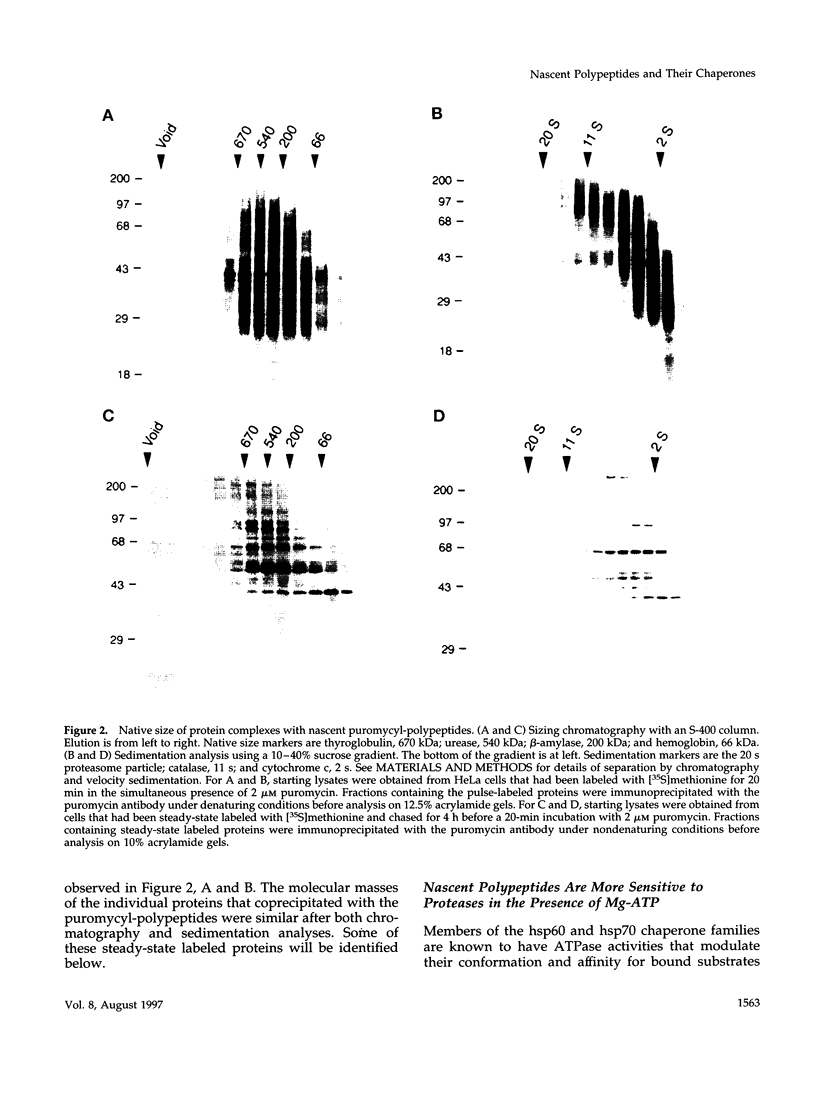

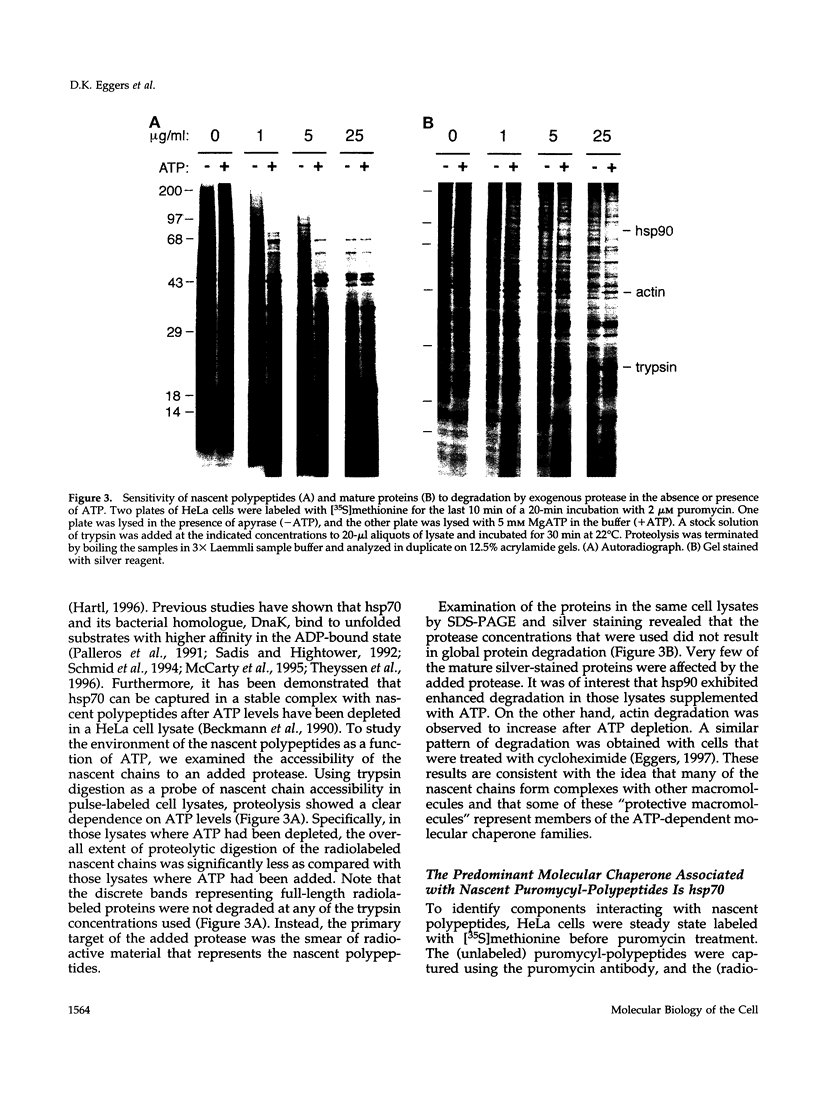

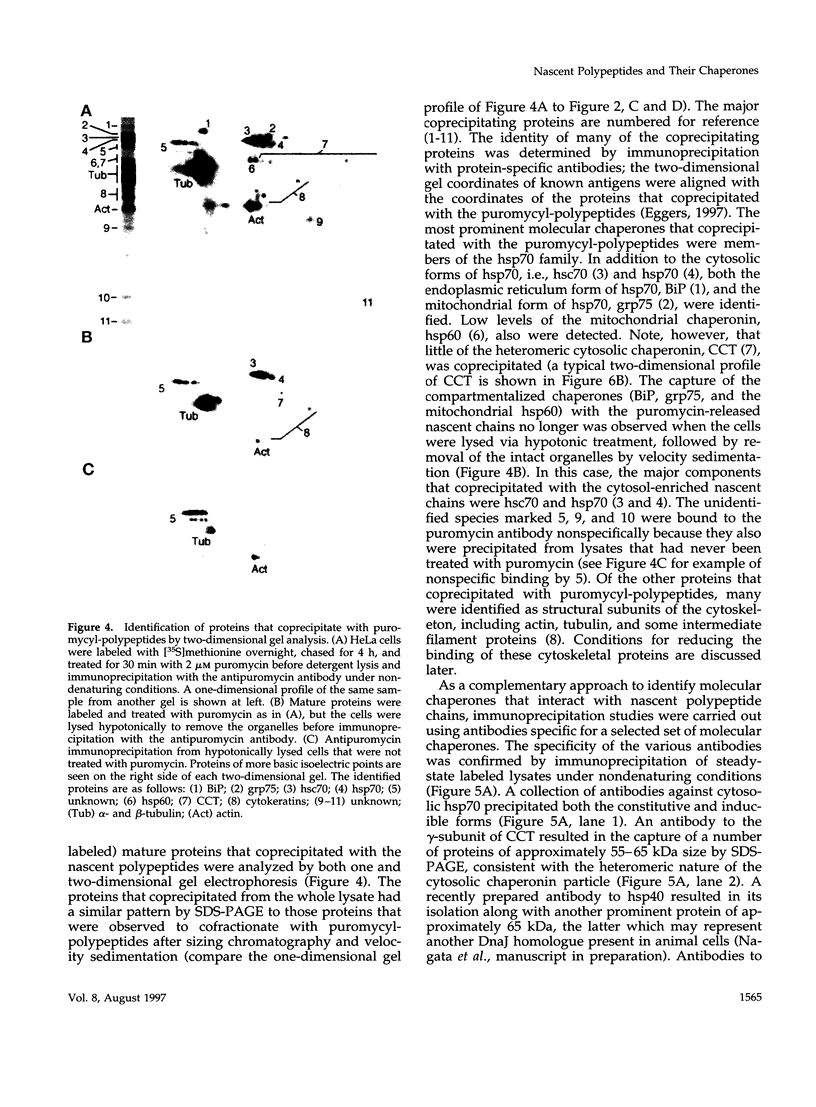

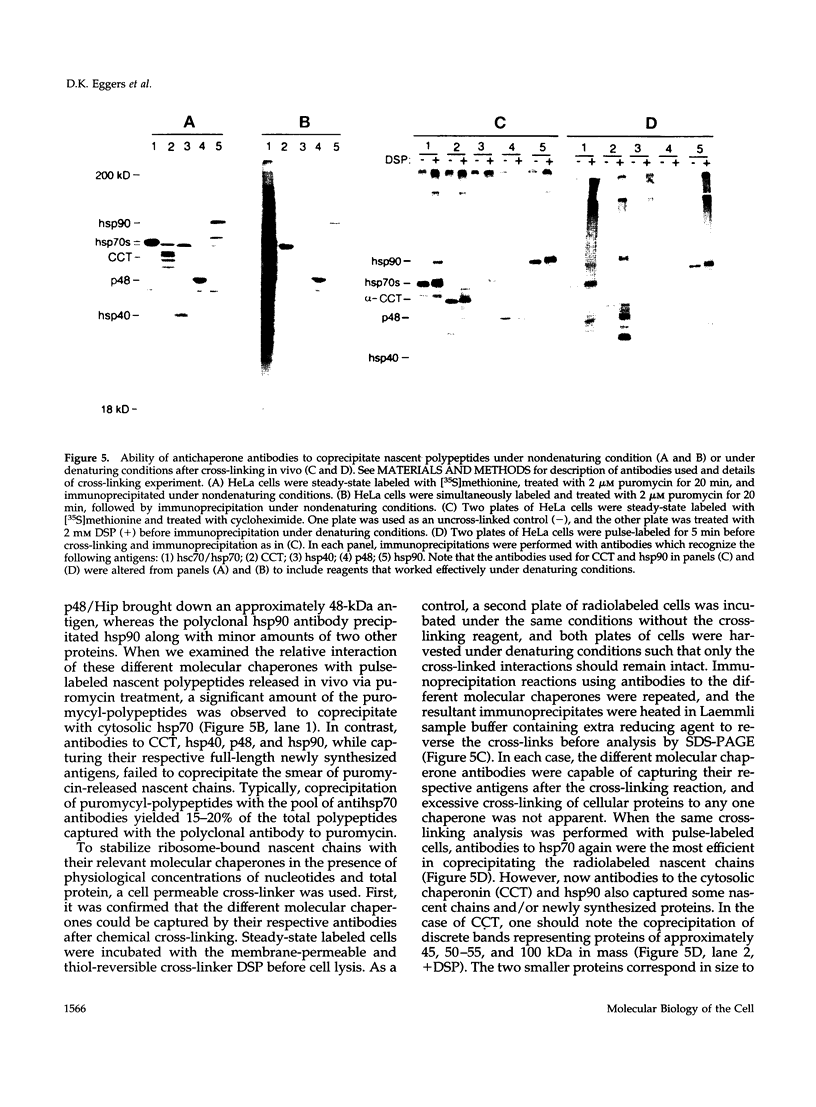

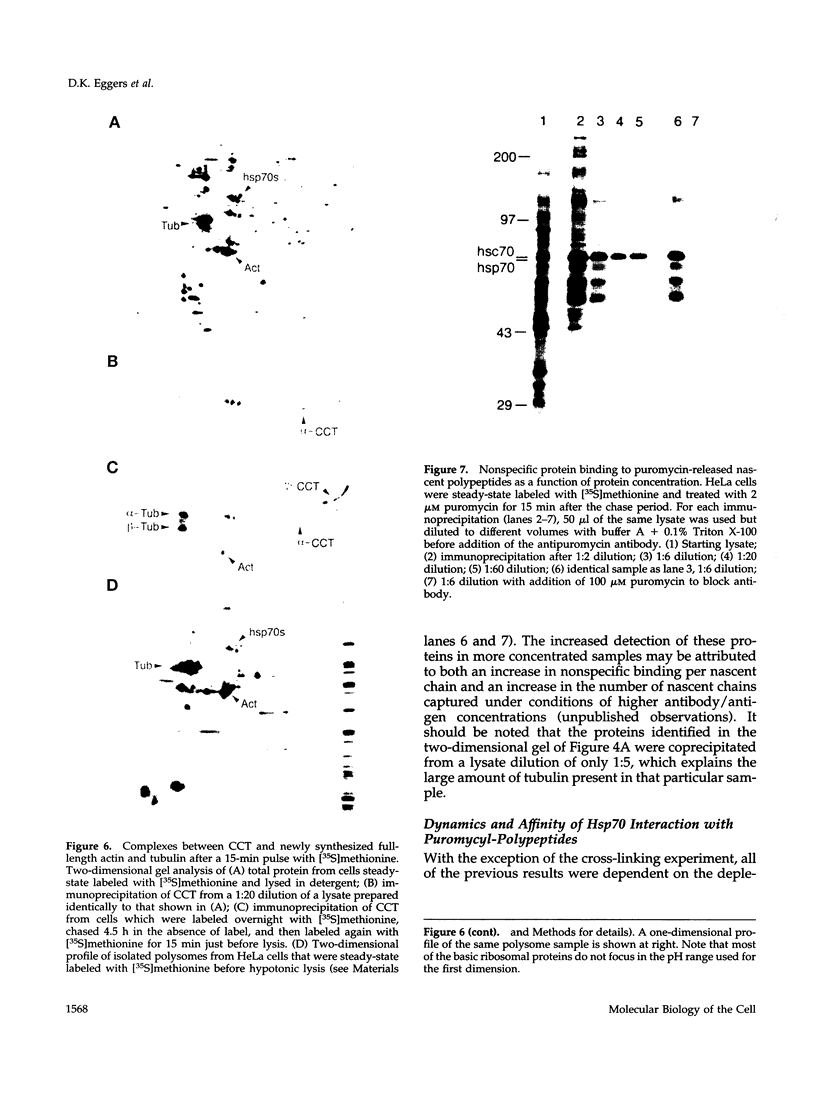

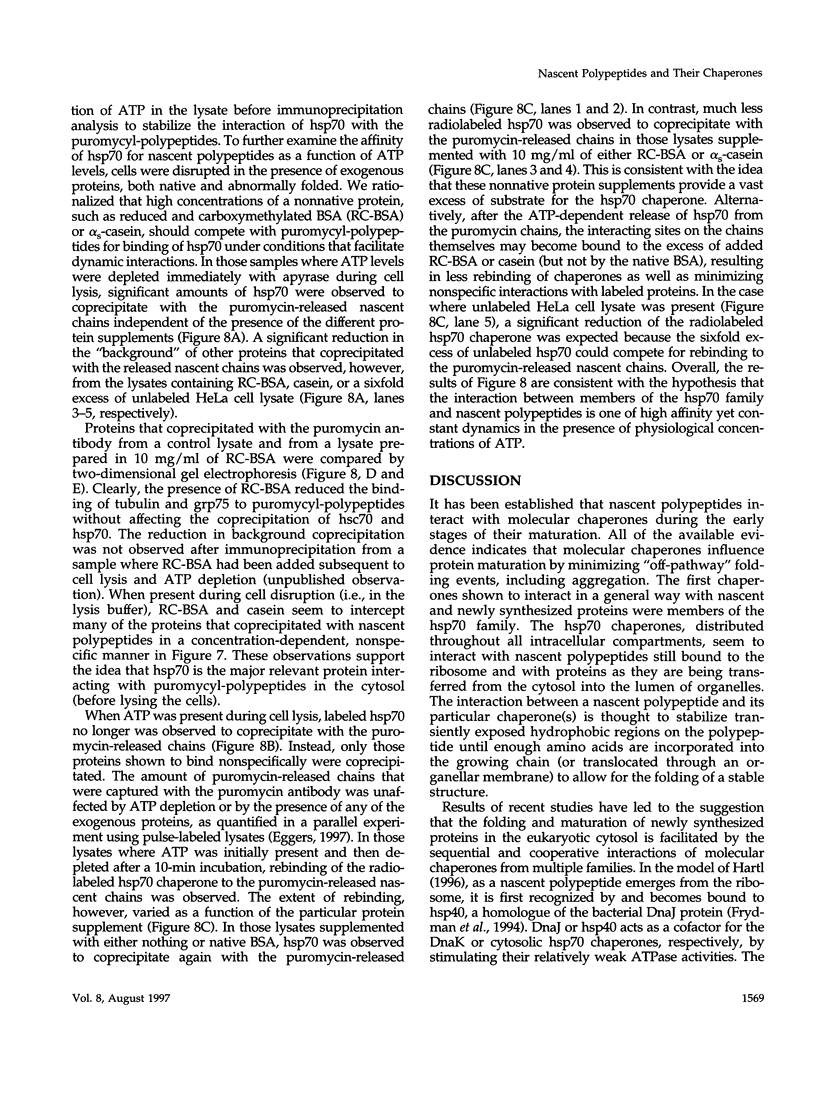

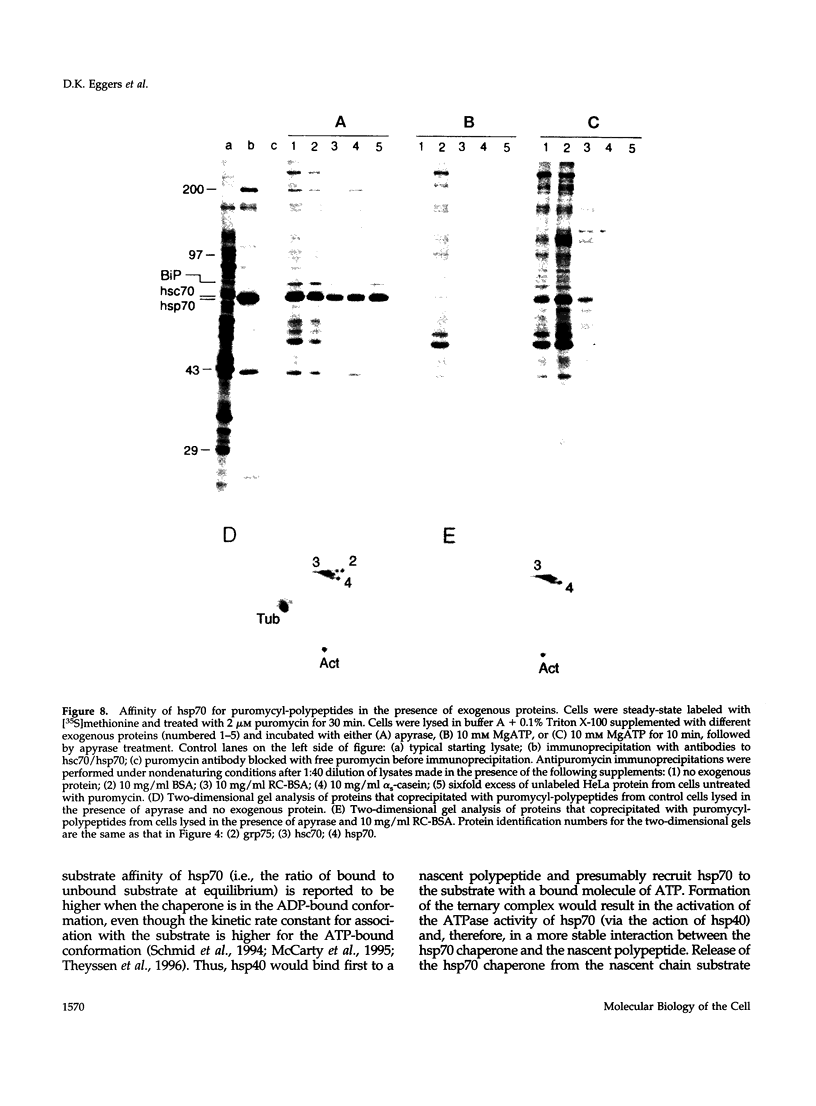

Folding of newly synthesized proteins in vivo is believed to be facilitated by the cooperative interaction of a defined group of proteins known as molecular chaperones. We investigated the direct interaction of chaperones with nascent polypeptides in the cytosol of mammalian cells by multiple methods. A new approach using a polyclonal antibody to puromycin allowed us to tag and capture a population of truncated nascent polypeptides with no bias as to the identity of the bound chaperones. In addition, antibodies that recognize the cytosolic chaperones hsp70, CCT (TRiC), hsp40, p48 (Hip), and hsp90 were compared on the basis of their ability to coprecipitate nascent polypeptides, both before and after chemical cross-linking. By all three approaches, hsp70 was found to be the predominant chaperone bound to nascent polypeptides. The interaction between hsp70 and nascent polypeptides is apparently dynamic under physiological conditions but can be stabilized by depletion of ATP or by cross-linking. The cytosolic chaperonin CCT was found to bind primarily to full-length, newly synthesized actin, and tubulin. We demonstrate and caution that nascent polypeptides have a propensity for binding many proteins nonspecifically in cell lysates. Although current models of protein folding in vivo have described additional components in contact with nascent polypeptides, our data indicate that the hsp70 and, perhaps, the hsp90 families are the predominant classes of molecular chaperones that interact with the general population of cytosolic nascent polypeptides.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anfinsen C. B. Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science. 1973 Jul 20;181(4096):223–230. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck S. C., De Maio A. Stabilization of protein synthesis in thermotolerant cells during heat shock. Association of heat shock protein-72 with ribosomal subunits of polysomes. J Biol Chem. 1994 Aug 26;269(34):21803–21811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J., Craig E. A. Heat-shock proteins as molecular chaperones. Eur J Biochem. 1994 Jan 15;219(1-2):11–23. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79502-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann R. P., Mizzen L. E., Welch W. J. Interaction of Hsp 70 with newly synthesized proteins: implications for protein folding and assembly. Science. 1990 May 18;248(4957):850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.2188360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. R., Martin R. L., Hansen W. J., Beckmann R. P., Welch W. J. The constitutive and stress inducible forms of hsp 70 exhibit functional similarities and interact with one another in an ATP-dependent fashion. J Cell Biol. 1993 Mar;120(5):1101–1112. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.5.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner J. Supervising the fold: functional principles of molecular chaperones. FASEB J. 1996 Jan;10(1):10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzynski J. K., Sternlicht M. L., Farr G. W., Sternlicht H. Newly-synthesized beta-tubulin demonstrates domain-specific interactions with the cytosolic chaperonin. Biochemistry. 1996 Dec 10;35(49):15870–15882. doi: 10.1021/bi961114j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman B. C., Morimoto R. I. The human cytosolic molecular chaperones hsp90, hsp70 (hsc70) and hdj-1 have distinct roles in recognition of a non-native protein and protein refolding. EMBO J. 1996 Jun 17;15(12):2969–2979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J., Hartl F. U. Principles of chaperone-assisted protein folding: differences between in vitro and in vivo mechanisms. Science. 1996 Jun 7;272(5267):1497–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J., Nimmesgern E., Erdjument-Bromage H., Wall J. S., Tempst P., Hartl F. U. Function in protein folding of TRiC, a cytosolic ring complex containing TCP-1 and structurally related subunits. EMBO J. 1992 Dec;11(13):4767–4778. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J., Nimmesgern E., Ohtsuka K., Hartl F. U. Folding of nascent polypeptide chains in a high molecular mass assembly with molecular chaperones. Nature. 1994 Jul 14;370(6485):111–117. doi: 10.1038/370111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos C., Welch W. J. Role of the major heat shock proteins as molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:601–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething M. J., Sambrook J. Protein folding in the cell. Nature. 1992 Jan 2;355(6355):33–45. doi: 10.1038/355033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen W. J., Lingappa V. R., Welch W. J. Complex environment of nascent polypeptide chains. J Biol Chem. 1994 Oct 28;269(43):26610–26613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl F. U. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996 Jun 13;381(6583):571–579. doi: 10.1038/381571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick J. P., Hartl F. U. The role of molecular chaperones in protein folding. FASEB J. 1995 Dec;9(15):1559–1569. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.15.8529835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick J. P., Langer T., Davis T. A., Hartl F. U., Wiedmann M. Control of folding and membrane translocation by binding of the chaperone DnaJ to nascent polypeptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Nov 1;90(21):10216–10220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesterkamp T., Hauser S., Lütcke H., Bukau B. Escherichia coli trigger factor is a prolyl isomerase that associates with nascent polypeptide chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Apr 30;93(9):4437–4441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höhfeld J., Minami Y., Hartl F. U. Hip, a novel cochaperone involved in the eukaryotic Hsc70/Hsp40 reaction cycle. Cell. 1995 Nov 17;83(4):589–598. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob U., Lilie H., Meyer I., Buchner J. Transient interaction of Hsp90 with early unfolding intermediates of citrate synthase. Implications for heat shock in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995 Mar 31;270(13):7288–7294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly E. C., Tremblay E., Tanguay R. M., Wu Y., Bibor-Hardy V. TRiC-P5, a novel TCP1-related protein, is localized in the cytoplasm and in the nuclear matrix. J Cell Sci. 1994 Oct;107(Pt 10):2851–2859. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.10.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota H., Hynes G., Willison K. The chaperonin containing t-complex polypeptide 1 (TCP-1). Multisubunit machinery assisting in protein folding and assembly in the eukaryotic cytosol. Eur J Biochem. 1995 May 15;230(1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudlicki W., Odom O. W., Kramer G., Hardesty B. Chaperone-dependent folding and activation of ribosome-bound nascent rhodanese. Analysis by fluorescence. J Mol Biol. 1994 Dec 2;244(3):319–331. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai B. T., Chin N. W., Stanek A. E., Keh W., Lanks K. W. Quantitation and intracellular localization of the 85K heat shock protein by using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Dec;4(12):2802–2810. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.12.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer T., Lu C., Echols H., Flanagan J., Hayer M. K., Hartl F. U. Successive action of DnaK, DnaJ and GroEL along the pathway of chaperone-mediated protein folding. Nature. 1992 Apr 23;356(6371):683–689. doi: 10.1038/356683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. A., Tian G., Vainberg I. E., Cowan N. J. Chaperonin-mediated folding of actin and tubulin. J Cell Biol. 1996 Jan;132(1-2):1–4. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis V. A., Hynes G. M., Zheng D., Saibil H., Willison K. T-complex polypeptide-1 is a subunit of a heteromeric particle in the eukaryotic cytosol. Nature. 1992 Jul 16;358(6383):249–252. doi: 10.1038/358249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingappa J. R., Martin R. L., Wong M. L., Ganem D., Welch W. J., Lingappa V. R. A eukaryotic cytosolic chaperonin is associated with a high molecular weight intermediate in the assembly of hepatitis B virus capsid, a multimeric particle. J Cell Biol. 1994 Apr;125(1):99–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty J. S., Buchberger A., Reinstein J., Bukau B. The role of ATP in the functional cycle of the DnaK chaperone system. J Mol Biol. 1995 May 26;249(1):126–137. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milarski K. L., Welch W. J., Morimoto R. I. Cell cycle-dependent association of HSP70 with specific cellular proteins. J Cell Biol. 1989 Feb;108(2):413–423. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. J., Ziegelhoffer T., Nicolet C., Werner-Washburne M., Craig E. A. The translation machinery and 70 kd heat shock protein cooperate in protein synthesis. Cell. 1992 Oct 2;71(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90269-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka K. Cloning of a cDNA for heat-shock protein hsp40, a human homologue of bacterial DnaJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993 Nov 30;197(1):235–240. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palleros D. R., Welch W. J., Fink A. L. Interaction of hsp70 with unfolded proteins: effects of temperature and nucleotides on the kinetics of binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Jul 1;88(13):5719–5723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prapapanich V., Chen S., Nair S. C., Rimerman R. A., Smith D. F. Molecular cloning of human p48, a transient component of progesterone receptor complexes and an Hsp70-binding protein. Mol Endocrinol. 1996 Apr;10(4):420–431. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.4.8721986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid B. G., Flynn G. C. GroEL binds to and unfolds rhodanese posttranslationally. J Biol Chem. 1996 Mar 22;271(12):7212–7217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadis S., Hightower L. E. Unfolded proteins stimulate molecular chaperone Hsc70 ATPase by accelerating ADP/ATP exchange. Biochemistry. 1992 Oct 6;31(39):9406–9412. doi: 10.1021/bi00154a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safiejko-Mroczka B., Bell P. B., Jr Bifunctional protein cross-linking reagents improve labeling of cytoskeletal proteins for qualitative and quantitative fluorescence microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996 Jun;44(6):641–656. doi: 10.1177/44.6.8666749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid D., Baici A., Gehring H., Christen P. Kinetics of molecular chaperone action. Science. 1994 Feb 18;263(5149):971–973. doi: 10.1126/science.8310296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder H., Langer T., Hartl F. U., Bukau B. DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE form a cellular chaperone machinery capable of repairing heat-induced protein damage. EMBO J. 1993 Nov;12(11):4137–4144. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher R. J., Hurst R., Sullivan W. P., McMahon N. J., Toft D. O., Matts R. L. ATP-dependent chaperoning activity of reticulocyte lysate. J Biol Chem. 1994 Apr 1;269(13):9493–9499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht H., Farr G. W., Sternlicht M. L., Driscoll J. K., Willison K., Yaffe M. B. The t-complex polypeptide 1 complex is a chaperonin for tubulin and actin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Oct 15;90(20):9422–9426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A., Langer T., Schröder H., Flanagan J., Bukau B., Hartl F. U. The ATP hydrolysis-dependent reaction cycle of the Escherichia coli Hsp70 system DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Oct 25;91(22):10345–10349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theyssen H., Schuster H. P., Packschies L., Bukau B., Reinstein J. The second step of ATP binding to DnaK induces peptide release. J Mol Biol. 1996 Nov 15;263(5):657–670. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G., Huang Y., Rommelaere H., Vandekerckhove J., Ampe C., Cowan N. J. Pathway leading to correctly folded beta-tubulin. Cell. 1996 Jul 26;86(2):287–296. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent Q. A., Kendall D. A., High S., Kusters R., Oudega B., Luirink J. Early events in preprotein recognition in E. coli: interaction of SRP and trigger factor with nascent polypeptides. EMBO J. 1995 Nov 15;14(22):5494–5505. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedmann B., Sakai H., Davis T. A., Wiedmann M. A protein complex required for signal-sequence-specific sorting and translocation. Nature. 1994 Aug 11;370(6489):434–440. doi: 10.1038/370434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willison K., Lewis V., Zuckerman K. S., Cordell J., Dean C., Miller K., Lyon M. F., Marsh M. The t complex polypeptide 1 (TCP-1) is associated with the cytoplasmic aspect of Golgi membranes. Cell. 1989 May 19;57(4):621–632. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]