Abstract

T lymphocyte (T cell) activation is predicated on the interaction between the T cell receptor and peptide–major histocompatibility (pMHC) ligands. The factors that determine the stimulatory potency of a pMHC molecule remain unclear. We describe results showing that a peptide exhibiting many hallmarks of a weak agonist stimulates T cells to proliferate more than the wild-type agonist ligand. An in silico approach suggested that the inability to form the central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC) could underlie the increased proliferation. This conclusion was supported by experiments that showed that enhancing cSMAC formation reduced stimulatory capacity of the weak peptide. Our studies highlight that a complex interplay of factors determines the quality of a T cell antigen.

INTRODUCTION

The activation of T lymphocytes (T cells) is stimulated by the binding of the T cell receptor (TCR) to its ligand, short peptides (p) bound to major histocompatibility (MHC) gene products. Initially it was thought that each TCR was specific for a single pMHC molecule, but it is now clear that a variety of related peptides can stimulate signaling through a particular TCR. The specific sequence of a peptide determines its stimulatory ability and the resulting functional outcome.

Altered peptide ligands (APLs), generated by mutating residues of the wild-type agonist peptide, have been used to investigate the role of antigen quality on T cell activation as well as mechanisms underlying TCR signaling (Evavold et al., 1993). APLs can have enhanced or reduced stimulatory ability compared to the wild type (WT) agonist peptide. The stimulatory potency of a peptide has been correlated with a variety of parameters that include the dissociation rate of the TCR/pMHC complex, the ability to downregulate TCRs, the ability to form an immunological synapse (IS), and the ability to generate fully phosphorylated TCR-ζ chains (Bachmann et al., 1997; Grakoui et al., 1999; Itoh et al., 1999; Kersh et al., 1998a; Madrenas et al., 1995; Sloan-Lancaster et al., 1994; Valitutti et al., 1995). The importance of the density of antigenic pMHC molecules expressed on an APC has also been noted (Gonzalez et al., 2005). How each of these parameters is linked to biophysical features of the TCR-pMHC interaction, stimulatory potency, and T cell signaling is not clearly understood. In this paper, we try to parse some of these connections by studying the relationship between TCR-pMHC binding parameters, formation of the IS, and T cell signaling and activation. For these studies, we.stimulated AND TCR transgenic T cells (which recognize the moth cytochrome C (MCC) peptide presented by I-Ek (Kaye et al., 1989)) with a series of APLs.

The IS refers to the spatially organized motif of membrane proteins and cytosolic molecules that forms at the junction between a T cell and an antigen presenting cell (APC) (Grakoui et al., 1999; Monks et al., 1998). In some ISs, TCR and pMHC ligands are clustered in the center of the contact area (a structure called the cSMAC). In spite of numerous studies, the function of the cSMAC remains elusive (e.g., Grakoui et al., 1999; Monks et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2002; Campi et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2005; Yokosuka et al., 2005).

We combined in vitro experiments with computational studies to examine how TCR signaling may be influenced by the biophysical parameters characterizing TCR-pMHC binding and cSMAC formation. The computational results show that, for pMHC ligands that bind the TCR with a sufficiently long half-life, the primary function of the cSMAC is to enhance TCR downregulation. One surprising consequence of this effect is our finding that a weak pMHC ligand that does not induce cSMAC formation results in enhanced T cell proliferation compared to the wild-type agonist. To prove that inability to induce cSMAC formation underlies the hyperproliferative response, we used NKG2D, a receptor expressed on NK cells and some CD8 T cells which can enhance cSMAC formation regardless of antigen quality (Markiewicz et al., 2005), and found that cSMAC formation inhibited the stimulatory capacity of the weak peptide agonist. Our computational studies, however, also indicated that currently available data cannot unequivocally conclude that the cSMAC always inhibits T cell signaling and activation. Future experimentation that could help resolve this issue are suggested.

RESULTS

Identification of APLs for AND T cells

To determine the relationship between antigen quality, IS formation, and signaling, we used T cells from the AND TCR transgenic mouse (Kaye et al., 1989). This TCR recognizes the MCC 88–103 peptide presented by I-Ek. While the stimulatory potency of a range of peptides obtained by mutating residues of MCC is known for the other cytochrome C TCR transgenic systems (Berg et al., 1989; Lyons et al., 1996; Matsui et al., 1994; Reay et al., 1994; Seder et al., 1992; Wulfing et al., 1997), APLs for AND were less well defined. We therefore tested the ability of several variants of the MCC peptide (including T102S, K99A, Y97K and T102L) to stimulate AND T cells. Two of the peptides, Y97K and T102L, were previously known to behave as null peptides for AND (Rogers et al., 1998).

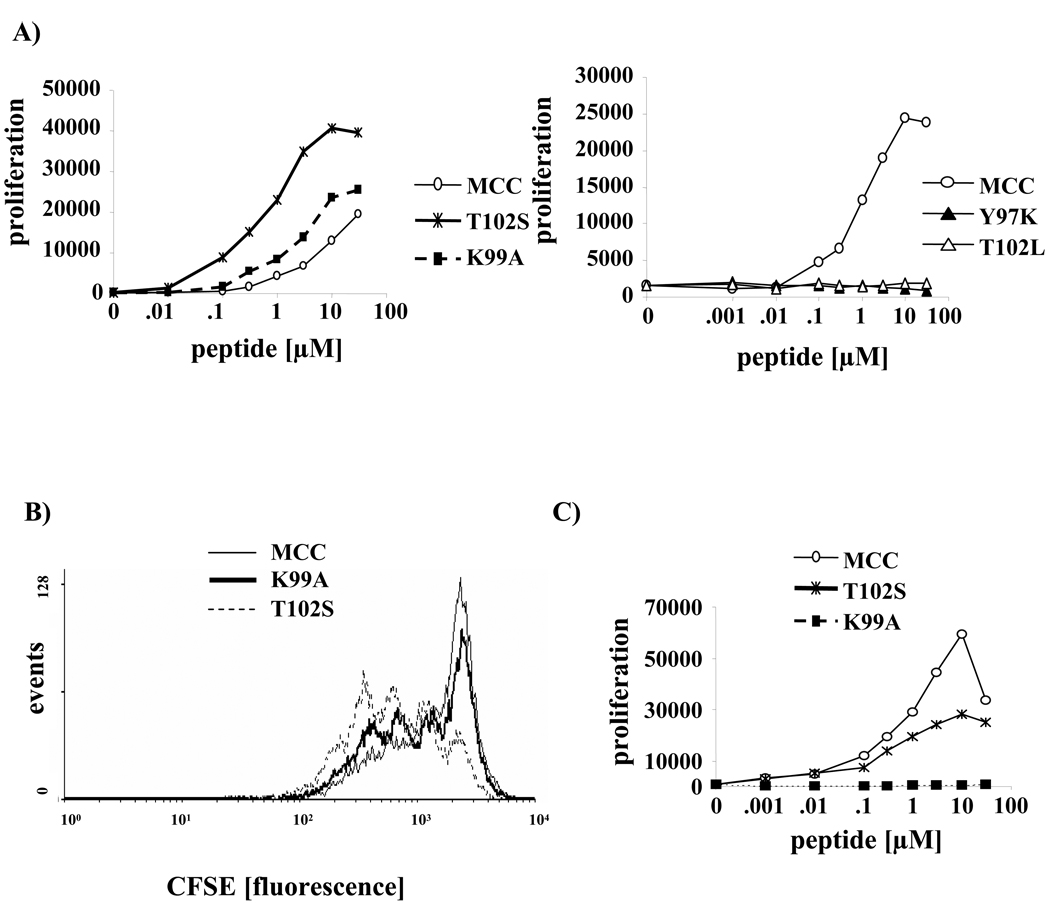

First, we tested each peptide for its ability to induce T cell proliferation. Naïve T cells were stimulated with WT or mutated MCC peptides, and T cell proliferative responses measured by both [3H]-thymidine uptake and CFSE dilution. As expected, the two null peptides, Y97K and T102L, did not induce any T cell proliferation (Fig. 1A right panel). T102S and K99A both induced a stronger T cell proliferative response than WT MCC peptide (Fig. 1A left panel). Results from CFSE-dilution experiments were consistent with the thymidine incorporation data (Fig. 1B). We excluded the possibility that these differences were related to differences in activation-induced cell death by measuring the percentages of live and dead cells as well as by staining with annexin V (Fig. S1). These results suggest that both the K99A and T102S peptides function as strong agonists.

Fig. 1. Proliferative response of AND and 5C.C7 T cells to WT and altered MCC peptides.

AND CD4+ T cells (A, B) and 5C.C7 CD4+ T cells (C) were isolated from spleens of TCR transgenic mice and stimulated with irradiated B10.BR splenocytes and the indicated peptides for 72 hours. The T cell proliferative response was assessed by the incorporation of [3H]-thymidine added for the last 18 hours of the stimulation. (n=10). C) AND T cells were CFSE labeled and stimulated for 3 days with irradiated B10.BR splenocytes loaded with 1 µM of the indicated peptides. The T cell proliferative response was assessed by CFSE dilution. (n=3).

We confirmed the identity of the peptides by assessing the proliferative response of T cells to these same peptides in another MCC-specific TCR transgenic model, the 5C.C7 TCR (Seder et al., 1992). As expected, T102S and K99A behaved as a weak agonist and a null peptide, respectively, for 5C.C7 T cells (Fig. 1C) (Lyons et al., 1996; Reay et al., 1994; Wulfing et al., 1997).

Determining dissociation kinetics and relative affinities of WT, K99A and T102S MCC peptides

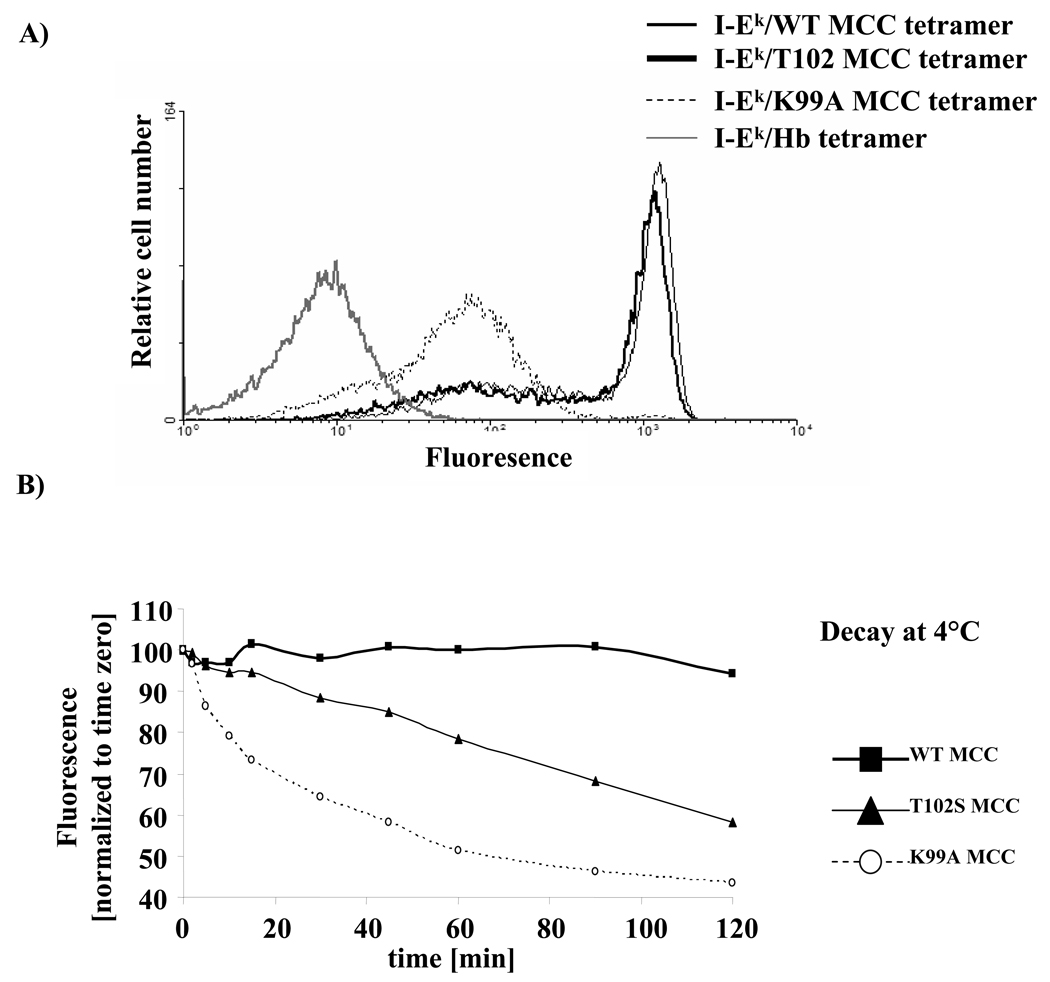

To determine the relative affinities of MCC, K99A and T102S for the AND TCR, we generated I-Ek tetramers with each of the peptides and analyzed the levels of equilibrium tetramer staining of AND T cells by flow cytometry. While WT and T102S showed comparable levels of tetramer binding at the same dose, the level of K99A tetramer staining of AND T cells was much lower (Fig. 2A). This suggested that I-Ek/K99A has a lower relative affinity for the AND TCR compared to the WT and T102S loaded I-Ek complexes.

Fig. 2. Staining of AND cells with I–Ek tetramers presenting MCC and its APLs.

Naïve CD4+ AND T cells were stained with the indicated tetramers for 3 hours at 10 degrees (in azide-containing buffer) and with anti-CD8-FITC and anti-B220-CyChrome during the last 30 minutes, washed 3 times in ice cold FACS buffer and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry (A) or resuspended in FACS buffer with 100 µg/ml of 14.4.4 antibody and incubated at 4°C. At indicated timepoints aliquots were taken and analyzed by flow cytometry for tetramer staining (B). Gate was set on FS/SS bright, CD8 negative and B220 negative cells. (n=3)

Since differences in affinity for the TCR are often related to the off-rates characterizing TCR-pMHC binding, a tetramer decay assay was performed to determine the relative off-rates for MCC, K99A and T102S. AND T cells were incubated with the three tetramers, and tetramer disassociation was monitored by flow cytometry over 2 hours. The T102S and K99A tetramers disassociated much faster than the tetramers containing the WT peptide (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that complexes of T102S and K99A pMHC with the AND TCR have a shorter apparent half-life compared to the WT MCC peptide. In addition, while we do not have a measurement of the on-rate, combining the relative affinity measurements with the results of the tetramer decay experiments suggests that T102S binds the AND TCR with a larger on-rate compared to MCC.

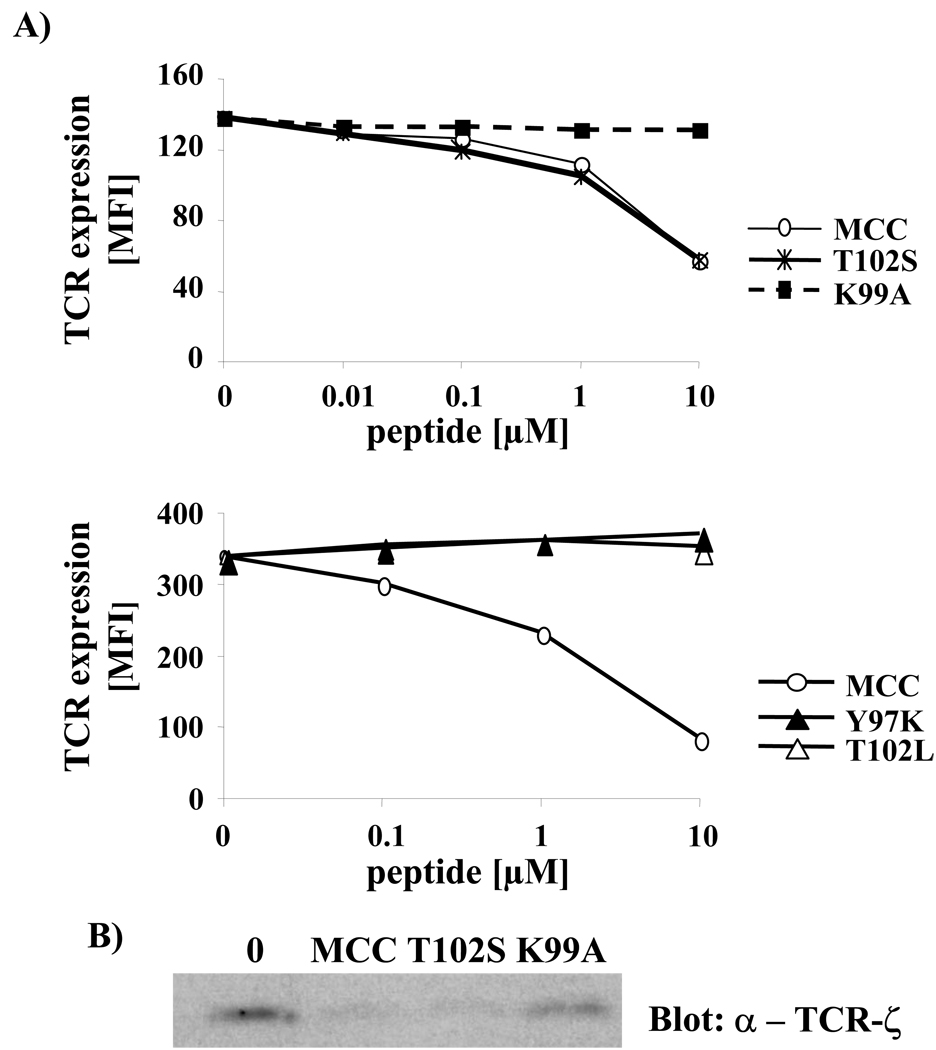

TCR downregulation and degradation

The paradoxical finding that the T102S and K99A peptides have faster off rates but stimulate higher levels of proliferation led us to examine other measures of agonist quality, such as the ability to induce TCR downregulation and degradation (Bachmann et al., 1997; Itoh et al., 1999; Valitutti et al., 1995). I-Ek-expressing CH27 cells were loaded with a range of peptide concentrations, incubated with T cells, and TCR downregulation was assessed by flow cytometry. The WT and T102S peptides both induced a dose-dependent downregulation of the TCR (Fig. 3A). In contrast, K99A induced low downregulation and the Y97K and T102L peptides induced essentially none (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the idea that TCR downregulation is due to degradation, immunoblotting for TCR-ζ chains showed that the WT and T102S peptides induced significantly greater TCR degradation compared to the K99A peptide (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. TCR downregulation and degradation in AND T cells stimulated with WTand APLs for MCC 88–103 peptide.

A) CD4+ T cells were purified from AND TCR tg mice spleens and stimulated for 3 hours with CH27 cells loaded with increasing amounts of the indicated peptides. Upon stimulation, cell conjugates were disrupted by trypsin-EDTA treatment, cells were stained with anti-Vβ3 and anti-CD4 antibodies, washed and analyzed by flow cytometry for surface TCR expression. (n=7) B) Rested AND CD4+ T cells were pretreated for 45 minutes with cyclohexamide and subsequently stimulated for 3 hours with CH27 cells loaded with 30 µM of the indicated peptide. Upon stimulation, cells were lysed and TCR-ζ expression was assessed by western blotting. (n=3)

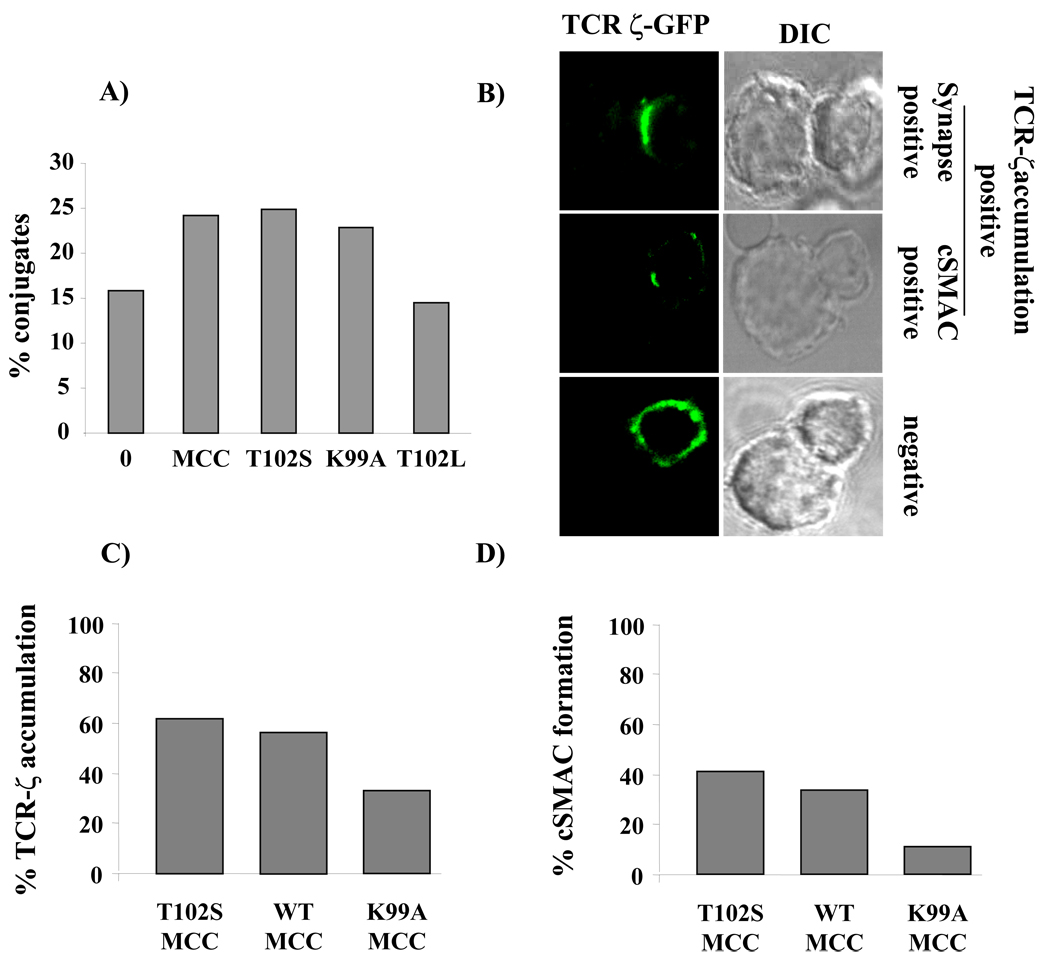

Antigen-induced IS and cSMAC formation

We next evaluated the ability of these peptides to induce conjugate formation, IS formation, and cSMAC formation. To assess conjugate formation, T cells and peptide-loaded APCs were labeled with two different colored dyes, incubated together for 30 minutes, and quantitated by flow cytometry. Conjugate formation between T cells and APCs loaded with T102S, K99A, and WT MCC was comparable and higher than conjugate formation with APCs without peptide or loaded with a null peptide (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Conjugate and immunological synapses formation induced by WT, K99A and T102S MCC peptides.

A) CD4+ AND T cells were labeled with CFSE and incubated for 30 minutes with peptide pulsed, Cell Trace-calcein labeled CH27 cells. Cells were then gently washed and conjugate formation assessed by flow cytometry. The percentage of T cells forming conjugates is presented as percentage of total T cells. (n=3) B-D) CD4+ AND T cells were retrovirally transduced with GFP-TCR-ζ, and sorted for GFP expression. T cells were incubated with CH27 cells pulsed with 30 µM of the indicated peptide. After 30 minutes, cells were fixed, mounted on poly-L-lysine treated slides and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Over 100 individual T cell-CH27 conjugates (n=3) were assessed for each tested peptide. Examples of how cell conjugates were scored for TCR-ζ accumulation at the contact site are shown in B. The percentages of T cells accumulating TCR-ζ at the contact site (C) and forming cSMACs (D) is presented as percentage of total conjugates analyzed.

To assess IS and cSMAC formation in T cell-APC conjugates, AND T cells were transduced with a retrovirus encoding TCR-ζ-GFP (Krummel et al., 2000) or doubly transduced with retroviruses encoding CD11a–YFP and CD28-CFP. After sorting, cells were incubated with APCs preloaded with peptides and conjugates fixed and analyzed for IS and cSMAC formation. Conjugates were scored as having formed an IS if the mean fluorescence of the cSMAC marker, TCR-ζ or CD28 at the contact site was at least two times higher than the mean fluorescence of the rest of the T cell membrane (Fig. 4B and Fig. S2A). Conjugates were scored as cSMAC-positive if there was an area of the contact site, not bigger than one third of the contact site, that had at least a two-fold enrichment of TCR-ζ or CD28 (Fig. 4B and Fig S2A). In the doubly transduced cells, we also confirmed that when the cSMAC formed, CD28 accumulated in the center and lacked the pSMAC marker, CD11a (Fig. S2A). Finally, conjugates with no obvious TCR-ζ or CD28 accumulation at the contact site were scored as negative (Fig. 4B and Fig. S2A).

The percentage of IS-positive conjugates was highest for the T102S peptide, followed by the WT peptide, and then by the K99A peptide (Fig. 4C). Scoring the conjugates for cSMAC formation revealed a similar pattern with cSMACs forming most readily with T102S, followed by MCC, and then by K99A (Fig. 4D and Fig. S2A). Finally, the reduced ability of K99A to form a mature IS was also seen when T cells were incubated on lipid bilayers (Fig. S3).Taken together, our results suggest that ability to efficiently form cSMACs does not always correlate with the stimulatory capacity of the peptide.

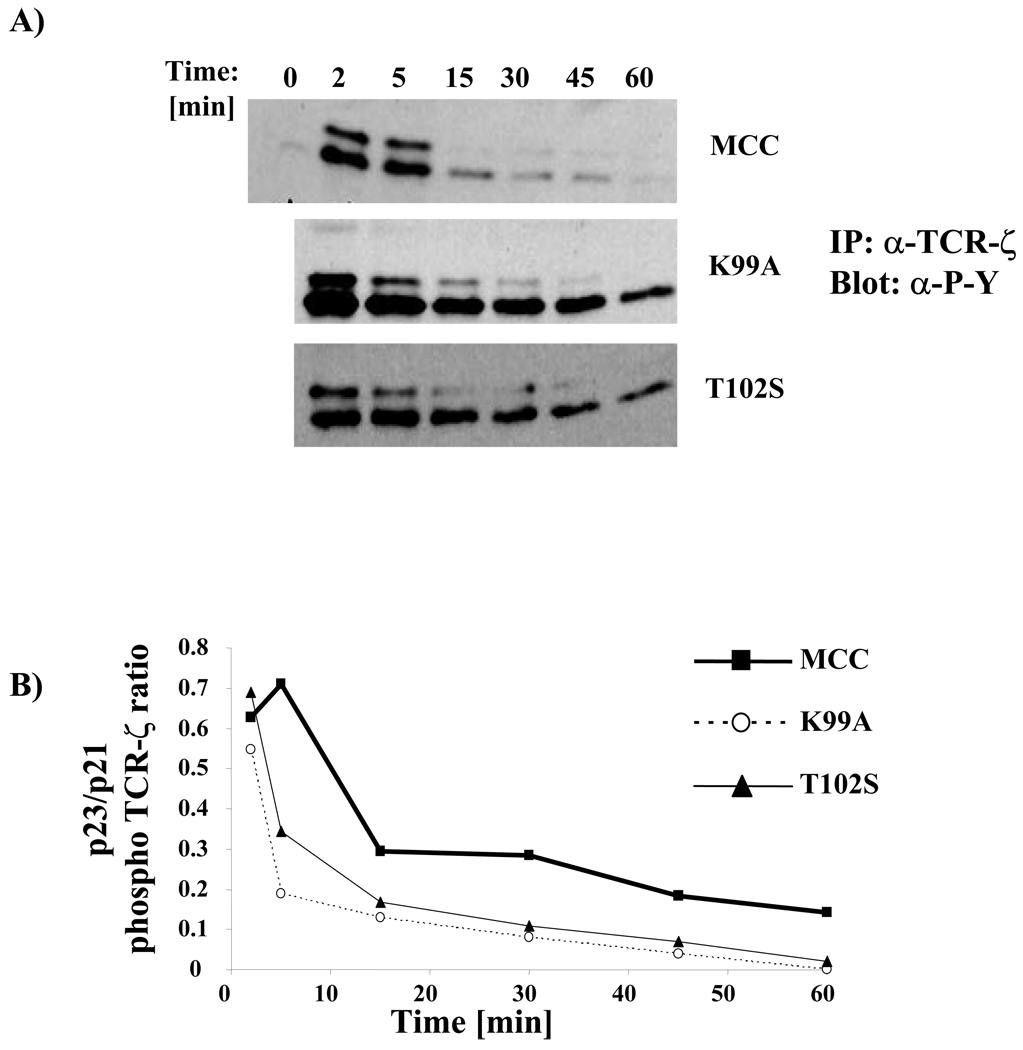

Full and partial TCR-ζ phosphorylation

Another indicator of agonist quality is the ratio of fully (p23) to partially (p21) phosphorylated TCR-ζ chains (Madrenas et al., 1995; Sloan-Lancaster et al., 1994). Stimulation with stronger agonists is thought to lead to a greater proportion of fully phosphorylated receptors and is reflected in the ratio of p23/p21 TCR-ζ phosphorylated forms. T cells were stimulated with APCs loaded with the K99A, T102S and WT MCC peptides. Compared to stimulation with the WT MCC peptide, both T102S and K99A showed lower p23/p21 ratios (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Kinetics of TCR-ζ phosphorylation in AND cells upon stimulation with WT, K99A and T102S MCC.

(A) Rested AND CD4+ Tells were stimulated with CH27 cells loaded with 10 µM of the indicated peptide for the indicated times. Upon stimulation cells were lysed, TCR-ζ was immunoprecipitated and tyrosine phosphorylation was assessed by immunoblotting. (n=4) (B) p23/p21 ratio after WT, K99A and T102S MCC stimulation over time. The data shown in (A) was analyzed using densitometry.

The time-course of TCR-ζ phosphorylation over one hour revealed differences in the kinetics of phosphorylation. While the WT MCC peptide induced a fast increase in TCR-ζ phosphorylation that attenuated rapidly (Fig. 5A), stimulation with both K99A and T102S was prolonged and detectable even after one hour of stimulation (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained when lysates were stained for activated ERK (Fig. S4). The prolonged kinetics of signaling was specific for the peptide as it was detectable even with a hundred fold less peptide loaded (data not shown). Lastly, the overall level of ζ-phosphorylation was stronger after T102S and K99A–stimulation compared to WT peptide. Thus, while the p23/p21 ratio was consistent with the shorter apparent half lives of the T102S and K99A complexes, the intensity of tyrosine phosphorylation and the prolonged kinetics correlated with the proliferative response.

Integrated signal depends upon antigen quality in a complicated manner

These seemingly paradoxical results showing, for example, that the K99A peptide does not induce efficient cSMAC formation but elicits a greater proliferative response compared to the WT peptide (which induces a cSMAC) suggested a complex interplay between competing phenomena that was difficult to intuit. We therefore undertook a computational study to gain further insights.

Since T cell activation requires prolonged signaling, we assumed that the integrated amount of signaling over time would correlate with proliferation. How the integrated amount of signal depends upon the on and off-rates characterizing TCR-pMHC binding and cSMAC formation was then analyzed. Because the role of the cSMAC in regulating TCR degradation is still unresolved, we examined the consequences of two different hypotheses. In the first hypothesis, no special assumption was made regarding where receptor degradation can occur. Receptor-ligand binding, downstream signaling reactions, and receptor degradation were allowed to occur wherever the appropriate molecules mediating specific chemical reactions encountered each other. In the second hypothesis, following suggestions in the literature (Campi et al., 2005; Yokosuka et al., 2005), it was a-priori assumed that receptor degradation could only occur in the cSMAC.

Computational investigation of either hypothesis requires a model for TCR signaling. The TCR signaling model that we studied (described in the Methods) is a modification of our previous model (Lee et al., 2003). In the current model, TCR degradation is treated more realistically by incorporating ubiquitination by allowing for the recruitment of the E3 ubiquitin ligase, Cbl, to phosphorylated ZAP-70 and CD3ζ molecules. These interactions resulted in ubiquitination, and only ubiquitinated receptors were subject to degradation. Thus, degradation is naturally linked to the level and concentration of phosphorylated substrates. In the first model, no restriction was imposed as to where Cbl could interact with receptors. In the second hypothesis, it was assumed that these processes can only occur in the cSMAC.

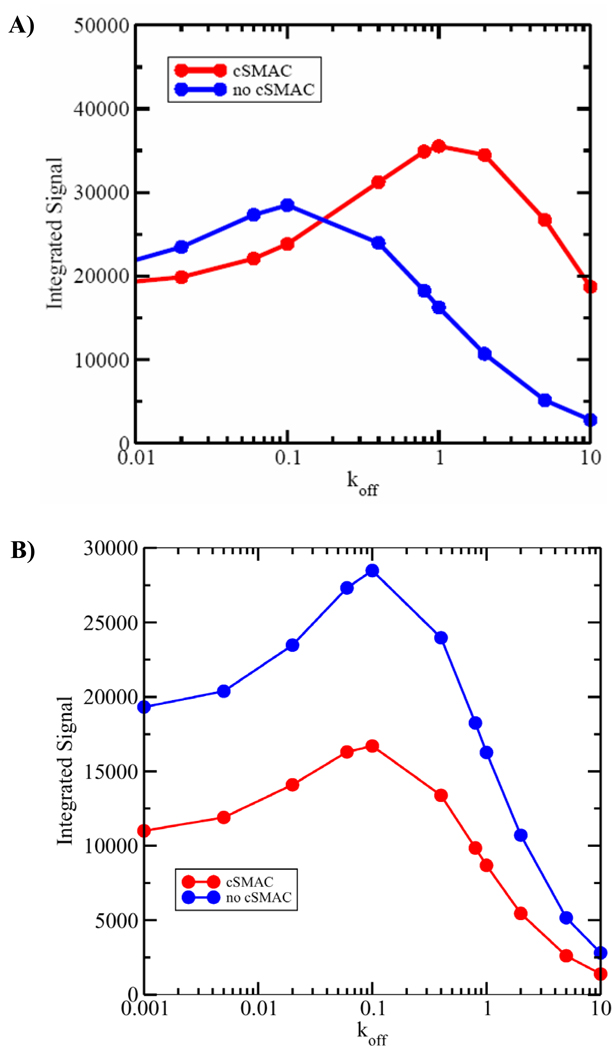

Relationships between half-life of TCR-pMHC complexes, cSMAC formation, and integrated signal

Calculations were first carried out to examine the effects of koff and cSMAC formation on the integrated signal, fixing the on-rate for TCR-pMHC binding. We studied two situations, one where a cSMAC was allowed to form regardless of the value of koff, and the other where the cSMAC never forms. Consider first representative data for the first hypothesis where no special assumption was made about where receptor degradation can occur (Fig. 6A). These results showed that, for ligands that bind the TCR with a long half-life, cSMAC formation led to a reduced amount of integrated signal. On the other hand, for ligands that bind the TCR with a short half-life, cSMAC formation is predicted to lead to an increase in the total integrated signal.

Fig. 6. Dependence of integrated signal on antigen quality.

(A) Results for the first hypothesis described in the text. Data for calculations are compared for two cases, one where a cSMAC (red circles) is allowed to form regardless of the value of koff and the other where no cSMAC (blue circles) is ever present. For small values of koff, cSMAC formation inhibited the total amount of integrated signal, while the opposite was true for ligands that bind TCR weakly. These calculations were carried out with a pMHC density of 1 molecule/(µm)2. Higher pMHC densities (e.g., 10 molecules/(µm)2) did not change the qualitative behavior (figure S19 ). These calculations were carried out for a value (Li et al., 2004) of kon equal to 2200 M−1 s−1. (B) Results for the second hypothesis described in the text. Integrated signal from a model (red line) where the cSMAC serves as a site for degradation only is compared with the situation where there is no cSMAC formation (blue line). All parameters are the same as in (A). The signal is always higher when there is no cSMAC formation and there is no intersection point as in Fig. 6A.

Analyses of our results showed that, for ligands with long half-lives (small koff), receptors are triggered efficiently without need for clustering in the cSMAC. However, we found that, for these ligands, cSMAC formation increases the rate of degradation (Fig. S11A). Our analysis showed that this is because concentrating receptors in one spatial location (cSMAC) enhances the ability of Cbl to ubiquitinate substrates (Fig. S9). Thus, the lower total integrated signal seen for strong ligands when cSMACs can form is explained by increased receptor downregulation (Fig. S11A).

At larger values of koff (half-life is short), this was reversed. Since weakly binding ligands did not trigger TCR efficiently, clustering of receptors, ligands, and kinases in the cSMAC aids in the generation of phosphorylated receptors and activated signaling intermediates because the enhanced concentration increased receptor occupancy and rates of phosphorylation. For these qualities of ligand, the integrated signal was distinctly smaller when the cSMAC did not form (Fig. S11B). Because these ligands induce lower levels of phosphorylation, the effects of cSMAC formation on signaling dominated over the effects of cSMAC formation on receptor downregulation. Importantly, the two curves in Fig. 6A (with and without cSMAC formation) intersect at a particular value of koff where the advantages and disadvantages of cSMAC formation are balanced.

A critical issue in the interpretation of these simulations for the first hypothesis is the threshold value of koff required to stimulate cSMAC formation (Grakoui et al., 1999; Sumen et al., 2004) and the relationship between this threshold and the point at which the two integrated signaling curves intersect. If the value of koff that triggers cSMAC formation does not correspond to the intersection point, the amount of integrated signal will exhibit a discontinuous change when T cells are stimulated by a ligand that is slightly weaker than that required for efficient cSMAC formation. For example, if the threshold value of koff that triggers cSMAC formation is higher (to the right) than the intersection point, the amount of integrated signal will precipitously decrease for a ligand that has a value of koff just above this threshold required for forming cSMACs. If the threshold value of koff that triggers cSMAC formation is smaller (to the left) of the intersection point, the amount of integrated signal will abruptly increase for ligands whose binding to TCR has a value of koff just above this threshold. Our experimental results showing that K99A elicits a stronger proliferative response than MCC, but does not form cSMACs efficiently, suggests that, if the first model is valid, the threshold for cSMAC formation lies to the left of the intersection point for AND T cells. It also suggests that if T cells stimulated by K99A could be manipulated to efficiently form a cSMAC, the integrated signal (i.e., stimulatory capacity) would be lower.

Calculations for the second hypothesis, where it is assumed that receptor downregulation can only occur in the cSMAC are shown in figure 6B. In contrast to Fig. 6A, the curves with and without cSMAC formation do not cross at any value of koff. In this model, cSMAC formation is predicted to reduce the amount of integrated signal for all antigen qualities. Thus, this hypothesis is also consistent with our experimental data on K99A as it suggests that the inability to form a cSMAC.will enhance stimulatory capacity regardless of TCR-pMHC off-rate. Differences between the results in Figs. 6A and B suggest a way to distinguish between the two hypotheses. For example, if a sufficiently weak ligand that normally cannot stimulate cSMAC formation could be coerced to form a cSMAC and the stimulatory potency increased then the first hypothesis would be correct.

NKG2D mediated cSMAC formation reduces the proliferative response to K99A

Previously, we showed that the engagement of NKG2D on CD8+ T cells allows for antigen independent formation of the cSMAC (Markiewicz et al., 2005). We reasoned, therefore, that expressing NKG2D on AND T cells might induce cSMAC formation, and thereby enable us to test whether the stimulatory potency of K99A would be reduced by cSMAC formation. AND T cells were doubly transduced with retroviruses containing cDNAs for NKG2D and its required signaling adapter, DAP10-YFP. NKG2D positive cells were conjugated with APCs expressing the NKG2D ligand, Rae-1ε, pre-incubated with the K99A peptide. As expected, NKG2D engagement strongly enhanced cSMAC formation both in the presence or absence of K99A peptide (Fig. 7A , 7B and 7C). Importantly, expression of NKG2D significantly reduced the level of proliferation induced by K99A (Fig. 7D). This supports our prediction that the enhanced proliferation seen with K99A is due to its inability to form cSMACs.

Fig. 7. Coerced cSMAC formation inhibits the proliferative response of AND T cells to K99A.

CD4+ AND T cells were retrovirally transduced with DAP10-YFP and NKG2D, and sorted for YFP and NKG2D expression. T cells were incubated, as indicated, with wt CH27 cells or CH27 cells transduced with Rae-1ε, unpulsed or pulsed with 20 µM of the indicated peptide. After 30 minutes, cells were fixed, mounted on poly-L-lysine treated slides and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Over 50 individual T cell-CH27 conjugates (n=2) were assessed. Examples of how cell conjugates were scored for DAP10-YFP accumulation at the contact site are shown in (A). The percentages of T cells accumulating DAP10 at the contact site (B) and forming cSMACs (C) are presented as the percentage of total conjugates analyzed. (D) NKG2D/DAP10-double positive AND T cells (dashed line) and wt AND T cells (full line) were stimulated with mitomycin C-treated, Rae-1e–expressing CH27 cells pulsed with 3µM or 0.1µM (data not shown) of the indicated peptide. The T cell proliferative responses were assessed by the incorporation of [3H]-thymidine added for the last 18 hours of the stimulation. (n=2).

Relationship between on-rate for TCR-pMHC binding, cSMAC formation and integrated signal

We next used our in silico model to explore how a higher proliferative response could be induced by the T102S peptide. Tetramer binding experiments suggested that the T102S/MHC complex binds the AND TCR with both a faster relative on and off-rate compared to MCC. We therefore used the model to compare the effects of different on-rates on the total integrated signal. An example of one of our simulations (following the first hypothesis) where the on-rate was increased by a factor of 10 is shown (Fig. S20). When the off-rate is small and cSMACs form, changing the on-rate by a factor of 10 had relatively little effect on the integrated signal. This can be explained by the fact that when the half-life is long, receptor occupancy is largely limited by the availability of pMHC. Under these conditions, enhancing the on rate 10 fold led to only a ~10 % change in receptor occupancy. The on-rate, however, became important when the off-rate was larger (half-life becomes shorter). Under these conditions, pMHC availability is not the limiting factor; increases in the on-rate resulted in increased receptor occupancy and increased integrated signal.

These computational results can potentially explain why the T102S peptide, which has a larger apparent off-rate and a larger apparent on-rate, can stimulate a stronger proliferative response than MCC. The similar affinities of T102S with MCC suggest that the level of receptor occupancy is similar. But the faster on-rate and larger off-rate suggests that binding by T102S is much more dynamic than MCC with much greater levels of receptor-ligand exchange. The concomitant increased “serial triggering” could explain the higher integrated signal.

DISCUSSION

How different parameters determine the ability of a pMHC molecule to stimulate T cell activation remains unclear. Many studies (Kalergis et al., 2001; Kersh et al., 1998b) have suggested that the off-rate characterizing the binding of pMHC ligands to TCR correlates well with its ability to stimulate T cell activation. However, several anomalies have been reported that raise questions about whether this is the only measure of antigen quality. Thus, other parameters and phenomena such as the change in heat capacity upon receptor-ligand binding (Krogsgaard et al., 2003; Qi et al., 2006), serial triggering, synergy between endogenous and agonist ligands (Wulfing et al., 2002; Krogsgaard et al., 2005; Li et al., 2004), and co-stimulatory interactions (Markiewicz et al., 2005; Purtic et al., 2005; Wulfing et al., 2002) have been implicated in modulating how T cells respond to antigen. Our studies combined in vitro and in silico investigations to examine the interplay between signaling, peptide quality and cSMAC formation.

Our results emphasize that the stimulatory potency of a pMHC ligand depends upon many factors, and that agonist quality does not correlate with any one variable. A dramatic example of this is provided by our experimental data for the stimulatory potency of the K99A peptide for AND T cells. This ligand binds the AND TCR with a larger value of the off-rate compared to the WT MCC and does not induce cSMAC formation. Yet, it elicited a greater proliferative response. This result raises the question as to whether other APLs classified only by proliferation assays as superagonists might actually be weaker binding ligands that do not induce cSMAC formation resulting in a higher total integrated signal.

Integrated signaling responses depend on TCR-pMHC binding and unbinding rates

Our results suggest that the on-rate characterizing TCR-pMHC binding may be important but only when the half-life of the complex is relatively short. When the half-life is long, receptor occupancy is limited by the availability of pMHC molecules, not the on-rate. But when half-life is short, a faster on-rate will strongly enhance receptor occupancy. Note, however, that these results apply to in vitro experiments where the agonist ligand density is relatively high. In vivo, antigen is limiting, and in this circumstance synergy between endogenous and agonist ligands could be important for signal amplification (Krogsgaard et al., 2005; Li et al., 2004); this could lead to complications that we have not considered.

When pMHC density is high, as in our in vitro experiments, endogenous ligands are not necessary for receptor triggering. In this circumstance, competition between serial triggering and kinetic proofreading is predicted to lead to an optimal half-life; i.e., pMHC that bind TCR with this half-life are most stimulatory. The AND TCR is not a physiological TCR and selects poorly on the k haplotype. This suggests that the half-life of the AND TCR for MCC peptide bound to I-Ak might be higher than optimal. Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that T102S, which binds the AND TCR with a shorter half-life compared to MCC, enhances signaling.

The role of the cSMAC

One idea emerging from our studies is that the dependence of cSMAC formation on TCR-pMHC half-life can modulate how the integrated amount of TCR signaling (and proliferative response) varies with receptor-ligand binding parameters. Our calculations showed that, for ligands that bind TCR sufficiently strongly, weaker ligands that do not induce cSMAC formation should induce greater proliferative responses. This explanation for our experimental data on AND T cells stimulated by the K99A peptide are clearly supported by our results showing the reduced stimulatory potency of this peptide upon forcing cSMAC formation by expression of NKG2D. The results of this experiment are especially striking as NKG2D is thought to function as a co-stimulator to enhance signaling through the TCR.

We should also note that the results of the experiment using NKG2D are consistent with both hypotheses whose consequences we examined using in silico modeling. Both Figs. 6A and B show that, if the half-life for TCR-pMHC complexes is relatively long, a ligand that cannot induce cSMAC formation will result in a larger integrated signal. This result is also consistent with our previously reported experimental results that showed that disruption of cSMAC formation due to CD2AP deficiency resulted in prolonged signaling and a more robust response when T cells were stimulated by a strong agonist (Lee et al., 2003).

The cSMAC and degradation

Recent work using single molecule imaging of T cells interacting with artificial lipid bilayers loaded with strong agonists suggest that signaling occurs mainly at the periphery of the contact area in microclusters (Campi et al., 2005; Yokosuka et al., 2005). Consistent with this result, our computer simulations showed that, for high affinity agonists, TCRs are efficiently triggered in the periphery without need for clustering of molecules in the cSMAC (Fig S13A). Our computational model, however, does not explicitly treat microclusters since it is a coarse-grained model that describes species in terms of concentrations. However, we expect the qualitative results reported by us to be similar if we were to carry out a simulation where individual receptor-ligand interactions and their clusters were treated explicitly. This is because, for strong agonists, we find that receptor triggering occurs efficiently in the pSMAC in our coarse-grained calculations just as is posited to occur in microclusters.

The paucity of phosphotyrosine staining in the cSMAC when T cells are stimulated by strong agonists has been interpreted to signify that the cSMAC functions only as a site of degradation (Mossman et al., 2005; Campi et al, 2005). Our computational results suggest that these past studies and the results reported by us in the present paper cannot unequivocally reach this conclusion because the situation could be different for weak ligands that are yet to be studied.

The major difference between the two hypotheses that we examined is manifested in the response to a peptide with a much shorter half-life than any we have tested. For peptides with very short half-lives, the first hypothesis (wherein no assumption is made about where degradation may occur) predicts that if cSMAC formation could occur, it would result in enhanced recognition of weak peptides. In contrast, the second hypothesis (where it is posited that degradation can only occur in the cSMAC) predicts that cSMAC formation will always weaken signaling. Our efforts to distinguish between these two hypotheses in this way are currently constrained by the fact that no adequate weak peptides are known for the AND TCR system.

It could be argued that the weak peptides that would distinguish between these two models are not physiologically relevant as they would probably be too weak to activate T cells. However, it has recently become clear that endogenous peptides that are unable to stimulate T cell activation on their own are likely to play significant roles in TCR triggering (Krogsgaard et al., 2005; Li et al., 2004; Gascoigne, 2006). The presence or absence of cSMACs could potentially determine the stimulatory capacity of such endogenous peptides at late time points in T cell signaling. This also raises important issues about in vivo situations where mixtures of both weak and strong ligands are present. Furthermore, the function of the cSMAC for less sensitive naïve T cells requires careful examination.

Our understanding of the function of the cSMAC is still evolving. We hope that continued synergy between modeling and experiments will help unravel this enigma.

METHODS

Mice

AND TCR transgenic mice (B6;SJL-Tg(TcrAND)53Hed/J) and B10.BR mice (B10.BR-H2k H2-T18a/SgSnJ) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. 5C.C7 TCR transgenic mice (5C.C7 TCRtg RAG-2−/− H-2a) were obtained from Taconic Farms. Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions in the Washington University animal facilities in accordance with institutional guidelines.

MCC Peptides

Wild type and mutated moth cytochrome C (MCC) peptides 88–103 were synthesized using standard F-moc chemistry. The peptides were purified to homogeneity by reverse-phase HPLC, and their composition was confirmed by mass spectrometry and amino acid analysis (Washington University Mass Spectrometry Facility, St. Louis, MO).

T cell purification

For purification of splenic T cells, splenocytes were depleted of CD8+, MHC class II-positive and immunoglobulin-positive cells by antibody-mediated nanoparticle negative selection (EasySep CD4+ negative selection cocktail, StemCell Technologies). The CD4+ T cells were used immediately as naïve T cells or stimulated for 4 days with irradiated B10.BR splenocytes and MCC peptide, rested for 2 days, and then used.

TCR downregulation

AND T cells were stimulated for 3 hours, in a 1:1 ratio, with peptide pulsed or unpulsed CH27 I-Ek cells. Upon stimulation, cells were pelleted and treated with trypsin-EDTA to break cell conjugates, washed, and labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 and PE-conjugated anti-Vβ3 antibodies (BD PharMingen). Vβ3 surface expression was assessed by flow cytometry (FACScan, BD Biosciences) on CD4-positive gated cells. Data was analyzed by WinMDI 2.8 software (facs.scripps.edu/software.html) or CellQuest (BD PharMingen).

Cell lysis, immunoprecipitation and western blotting

AND T cells were pretreated with cyclohexamide for 45 minutes and stimulated with an equal number of unpulsed or peptide pulsed- CH27 I-Ek cells. After stimulation, cells were lysed for 10 min on ice in 1% NP-40 containing lysis buffer and cleared by centrifugation. For TCR degradation assays, postnuclear supernatants were resolved on SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoblotted with an anti-TCR-ζ antiserum. For TCR-ζ phosphorylation, postnuclear supernatants immunoprecipitated with an anti-TCR-ζ antiserum, resolved on SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (clone 4G10; Upstate Biotechnology). Blots were visualized using ECL Western blotting kit (Pierce). Densitometry was performed using IPLab software (Scanalytics).

T cell proliferation assays

Naïve or rested CD4+ AND or 5C.C7 T cells were stimulated for 48 hours with irradiated B10.BR cells and various amounts of peptides, pulsed with 1 µCi of [3H] thymidine/well, harvested 16 h later, and scintillation counted. Cells were labeled with CFSE, stimulated for 3 days with irradiated B10.BR splenocytes pre-pulsed with peptides and assessed for CFSE staining by flow cytometry.

Transfection and retroviral transduction

The Plat E ecotropic packaging cell line was transfected with a TCR-ζ-GFP retroviral construct (kindly provided by M. Davis, Stanford University) or a mixture of NKG2D and DAP10-YFP retroviral constructs. AND T cells were stimulated with irradiated B10.BR splenocytes and 10 µM MCC peptide. At 18 and 42 hours after stimulation, T cells were incubated for 4 hours with the viral supernatants upon spinfection for 45 minutes in the presence of Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen). At day 4 after stimulation, GFP positive T cells were sorted by using FACSVantage flow sorter (BD Biosciences) at the Washington University Pathology Cell Sorting Facility. After NKG2D/DAP10-YFP double transduction, cells were stained with a PE-labeled anti-NKG2D antibody and YFP-positive, PE-positive cells were sorted and used for further experimentation.

T cell-APC conjugate formation

T cells and APCs were labeled with CFSE and Cell TraceTM calcein red-orange, AM (Molecular Probes), respectively, and incubated for 30 minutes to allow conjugate formation. Cells were then gently washed and conjugate formation was assessed by flow cytometry as the ratio of CFSE/Cell Trace double positive cells to total CFSE-positive cells. Data was analyzed by WinMDI 2.8 software (facs.scripps.edu/software.html) or CellQuest (BD PharMingen).

IS and cSMAC formation

Sorted retrovirally transduced AND T cells were incubated with peptide loaded or unloaded CH27 I-Ek cells for 30 minutes. Cells were then fixed, mounted on coverslips, and confocal images taken using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. Unprocessed images were scored, using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2006), as described in the text.

Tetramer production, tetramer staining and tetramer-decay experiments

I-Ek/MCC tetramers (with WT, K99A or T102S MCC) were generated as described previously (Gutgemann et al., 1998). For equilibrium staining, AND T cells were stained with I-Ek/MCC tetramers for 3 hours at 10°C, washed twice, resuspended in FACS buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry. For relative koff measurements, AND T cells were stained for 3 hours at 4° C, washed twice, resuspended in FACS buffer in the presence of 100mg/ml of 14.4.4 antibody and incubated at 4°C to allow tetramer decay. At specific time points, cells were removed and analyzed for staining by flow cytometry. A tetramer with an irrelevant peptide bound (Hb) was used as a negative control. Mean fluorescence at each time point was calculated by subtracting the mean fluorescence of the negative control and then normalizing to the fluorescence at time zero.

The computational model

A continuum model that parallels and complements our previous stochastic models (Lee et al., 2003) was developed This enables us to readily examine large systems under diverse conditions and exhaustively examine the sensitivity of the model to values of unknown parameters. However, stochastic models (Lee et al., 2003; Li et al. 2004) are necessary if the copy number of certain species is very small. Since most in vitro experiments are carried out with a rather high antigen dose (e.g., concentration of agonist peptides loaded on supported lipid bilayers is 1 – 100 molecules/µm2 (Grakoui et al., 1999))., use of the continuum model is appropriate. Varying the densities of various species led to qualitatively similar results over a range of values, and the effects of fluctuations for low pMHC densities and small values of the off-rate, were not large for the conditions of interest in this paper (web supplement).

In the model, the membrane associated and cytosolic molecules undergo biochemical reactions according to the signaling cascade shown in Fig. S5. As described in the text, receptor degradation is treated more accurately with incorporation of ubiquitination. Some details found not to affect qualitative results of interest in this paper were not incorporated in the present study (feedback loops regulating Lck activity (Altan-Bonnet and Germain, 2005; Stefanova et al., 2003) and downstream signaling molecules (Ras, Rac, etc. that are downstream of ZAP70 activation).

cSMAC is modeled as described previously (Lee et al., 2003). We link cSMAC formation to downstream signaling by turning on a potential field that acts on certain species and drives them to form a cSMAC when activated ZAP70 exceeds a threshold. The spatially varying potential field is a coarse-grained representation of forces (derivative of a potential) that direct cSMAC formation. The magnitude of the potential is chosen so that a cSMAC forms in a few (~ 5) minutes. The depth and spatial variation of this potential field determine the rate of cSMAC formation and the concentration of species therein.

The spatio-temporal distribution of each species varies due to diffusion, biochemical reactions that are part of the signaling cascade, and convective motion if a cSMAC is formed. The relevant equations are provided in the web supplement. The numerical methods used to solve the large set of partial differential equations is provided in the web supplement, which also contains a list of parameters used to carry out our calculations and a discussion of our relatively extensive parameter sensitivity studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Dustin for fruitful discussions. This research is supported by the NIH (grants AI034094, AI057966, AI071195-01)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altan-Bonnet G, Germain RN. Modeling T cell antigen discrimination based on feedback control of digital ERK responses. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann MF, Oxenius A, Speiser DE, Mariathasan S, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM, Ohashi PS. Peptide-induced T cell receptor down-regulation on naive T cells predicts agonist/partial agonist properties and strictly correlates with T cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2195–2203. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg LJ, Pullen AM, Fazekas de St Groth B, Mathis D, Benoist C, Davis MM. Antigen/MHC-specific T cells are preferentially exported from the thymus in the presence of their MHC ligand. Cell. 1989;58:1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campi G, Varma R, Dustin ML. Actin and agonist MHC-peptide complex-dependent T cell receptor microclusters as scaffolds for signaling. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1031–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello PS, Gallagher M, Cantrell DA. Sustained and dynamic inositol lipid metabolism inside and outside the immunological synapse. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1082–1089. doi: 10.1038/ni848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evavold BD, Sloan-Lancaster J, Allen PM. Tickling the TCR: selective T-cell functions stimulated by altered peptide ligands. Immunol Today. 1993;14:602–609. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez PA, Carreno LJ, Coombs D, Mora JE, Palmieri E, Goldstein B, Nathenson SG, Kalergis AM. T cell receptor binding kinetics required for T cell activation depend on the density of cognate ligand on the antigen-presenting cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4824–4829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500922102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM, Dustin ML. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutgemann I, Fahrer AM, Altman JD, Davis MM, Chien YH. Induction of rapid T cell activation and tolerance by systemic presentation of an orally administered antigen. Immunity. 1998;8:667–673. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80571-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine DJ, Purbhoo MA, Krogsgaard M, Davis MM. Direct observation of ligand recognition by T cells. Nature. 2002;419:845–849. doi: 10.1038/nature01076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Hemmer B, Martin R, Germain RN. Serial TCR engagement and down-modulation by peptide:MHC molecule ligands: relationship to the quality of individual TCR signaling events. J Immunol. 1999;162:2073–2080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalergis AM, Boucheron N, Doucey MA, Palmieri E, Goyarts EC, Vegh Z, Luescher IF, Nathenson SG. Efficient T cell activation requires an optimal dwell-time of interaction between the TCR and the pMHC complex. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:229–234. doi: 10.1038/85286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye J, Hsu ML, Sauron ME, Jameson SC, Gascoigne NR, Hedrick SM. Selective development of CD4+ T cells in transgenic mice expressing a class II MHC-restricted antigen receptor. Nature. 1989;341:746–749. doi: 10.1038/341746a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersh EN, Shaw AS, Allen PM. Fidelity of T cell activation through multistep T cell receptor zeta phosphorylation. Science. 1998a;281:572–575. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5376.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersh GJ, Kersh EN, Fremont DH, Allen PM. High- and low-potency ligands with similar affinities for the TCR: the importance of kinetics in TCR signaling. Immunity. 1998b;9:817–826. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80647-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogsgaard M, Li QJ, Sumen C, Huppa JB, Huse M, Davis MM. Agonist/endogenous peptide-MHC heterodimers drive T cell activation and sensitivity. Nature. 2005;434:238–243. doi: 10.1038/nature03391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogsgaard M, Prado N, Adams EJ, He XL, Chow DC, Wilson DB, Garcia KC, Davis MM. Evidence that structural rearrangements and/or flexibility during TCR binding can contribute to T cell activation. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1367–1378. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00474-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krummel MF, Sjaastad MD, Wulfing C, Davis MM. Differential clustering of CD4 and CD3zeta during T cell recognition. Science. 2000;289:1349–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Dinner AR, Tu C, Campi G, Raychaudhuri S, Varma R, Sims TN, Burack WR, Wu H, Wang J, et al. The immunological synapse balances T cell receptor signaling and degradation. Science. 2003;302:1218–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.1086507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Holdorf AD, Dustin ML, Chan AC, Allen PM, Shaw AS. T cell receptor signaling precedes immunological synapse formation. Science. 2002a;295:1539–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.1067710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Hori Y, Groves JT, Dustin ML, Chakraborty AK. Correlation of a dynamic model for immunological synapse formation with effector functions: two pathways to synapse formation. Trends Immunol. 2002b;23:492–499. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QJ, Dinner AR, Qi S, Irvine DJ, Huppa JB, Davis MM, Chakraborty AK. CD4 enhances T cell sensitivity to antigen by coordinating Lck accumulation at the immunological synapse. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:791–799. doi: 10.1038/ni1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Miller MJ, Shaw AS. The c-SMAC: sorting it all out (or in) J Cell Biol. 2005;170:177–182. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons DS, Lieberman SA, Hampl J, Boniface JJ, Chien Y, Berg LJ, Davis MM. A TCR binds to antagonist ligands with lower affinities and faster dissociation rates than to agonists. Immunity. 1996;5:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrenas J, Wange RL, Wang JL, Isakov N, Samelson LE, Germain RN. Zeta phosphorylation without ZAP-70 activation induced by TCR antagonists or partial agonists. Science. 1995;267:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.7824949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz MA, Carayannopoulos LN, Naidenko OV, Matsui K, Burack WR, Wise EL, Fremont DH, Allen PM, Yokoyama WM, Colonna M, Shaw AS. Costimulation through NKG2D Enhances Murine CD8+ CTL Function: Similarities and Differences between NKG2D and CD28 Costimulation. J Immunol. 2005;175:2825–2833. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui K, Boniface JJ, Steffner P, Reay PA, Davis MM. Kinetics of T-cell receptor binding to peptide/I-Ek complexes: correlation of the dissociation rate with T-cell responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;17:12862–12866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks CR, Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Sciaky N, Kupfer A. Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells. Nature. 1998;395:82–86. doi: 10.1038/25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman KD, Campi G, Groves JT, Dustin ML. Altered TCR signaling from geometrically repatterned immunological synapses. Science. 2005;310:1191–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.1119238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purtic B, Pitcher LA, van Oers NS, Wulfing C. T cell receptor (TCR) clustering in the immunological synapse integrates TCR and costimulatory signaling in selected T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2904–2909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406867102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi S, Krogsgaard M, Davis MM, Chakraborty AK. Molecular flexibility can influence the stimulatory ability of receptor-ligand interactions at cell-cell junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510991103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi SY, Groves JT, Chakraborty AK. Synaptic pattern formation during cellular recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6548–6553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111536798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reay PA, Kantor RM, Davis MM. Use of global amino acid replacements to define the requirements for MHC binding and T cell recognition of moth cytochrome c (93–103) J Immunol. 1994;152:3946–3957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers PR, Grey HM, Croft M. Modulation of naive CD4 T cell activation with altered peptide ligands: the nature of the peptide and presentation in the context of costimulation are critical for a sustained response. J Immunol. 1998;160:3698–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seder RA, Paul WE, Davis MM, Fazekas de St Groth B. The presence of interleukin 4 during in vitro priming determines the lymphokine-producing potential of CD4+ T cells from T cell receptor transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1091–1098. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan-Lancaster J, Shaw AS, Rothbard JB, Allen PM. Partial T cell signaling: altered phospho-zeta and lack of zap70 recruitment in APL-induced T cell anergy. Cell. 1994;79:913–922. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somersalo K, Anikeeva N, Sims TN, Thomas VK, Strong RK, Spies T, Lebedeva T, Sykulev Y, Dustin ML. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes form an antigen-independent ring junction. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:49–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanova I, Hemmer B, Vergelli M, Martin R, Biddison WE, Germain RN. TCR ligand discrimination is enforced by competing ERK positive and SHP-1 negative feedback pathways. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:248–254. doi: 10.1038/ni895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumen C, Dustin ML, Davis MM. T cell receptor antagonism interferes with MHC clustering and integrin patterning during immunological synapse formation. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:579–590. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valitutti S, Muller S, Cella M, Padovan E, Lanzavecchia A. Serial triggering of many T-cell receptors by a few peptide-MHC complexes. Nature. 1995;375:148–151. doi: 10.1038/375148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stipdonk MJ, Hardenberg G, Bijker MS, Lemmens EE, Droin NM, Green DR, Schoenberger SP. Dynamic programming of CD8+ T lymphocyte responses. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:361–365. doi: 10.1038/ni912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola A, Lanzavecchia A. T cell activation determined by T cell receptor number and tunable thresholds. Science. 1996;273:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann A, Muller S, Favier B, Penna D, Guiraud M, Delmas C, Champagne E, Valitutti S. T-cell activation is accompanied by an ubiquitination process occurring at the immunological synapse. Immunol Lett. 2005;98:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulfing C, Davis MM. A receptor/cytoskeletal movement triggered by costimulation during T cell activation. Science. 1998;282:2266–2269. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulfing C, Rabinowitz JD, Beeson C, Sjaastad MD, McConnell HM, Davis MM. Kinetics and extent of T cell activation as measured with the calcium signal. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1815–1825. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulfing C, Sumen C, Sjaastad MD, Wu LC, Dustin ML, Davis MM. Costimulation and endogenous MHC ligands contribute to T cell recognition. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:42–47. doi: 10.1038/ni741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachi PP, Ampudia J, Zal T, Gascoigne NR. Altered peptide ligands induce delayed CD8-T cell receptor interaction--a role for CD8 in distinguishing antigen quality. Immunity. 2006;25:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosuka T, Sakata-Sogawa K, Kobayashi W, Hiroshima M, Hashimoto-Tane A, Tokunaga M, Dustin ML, Saito T. Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1253–1262. doi: 10.1038/ni1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.