Abstract

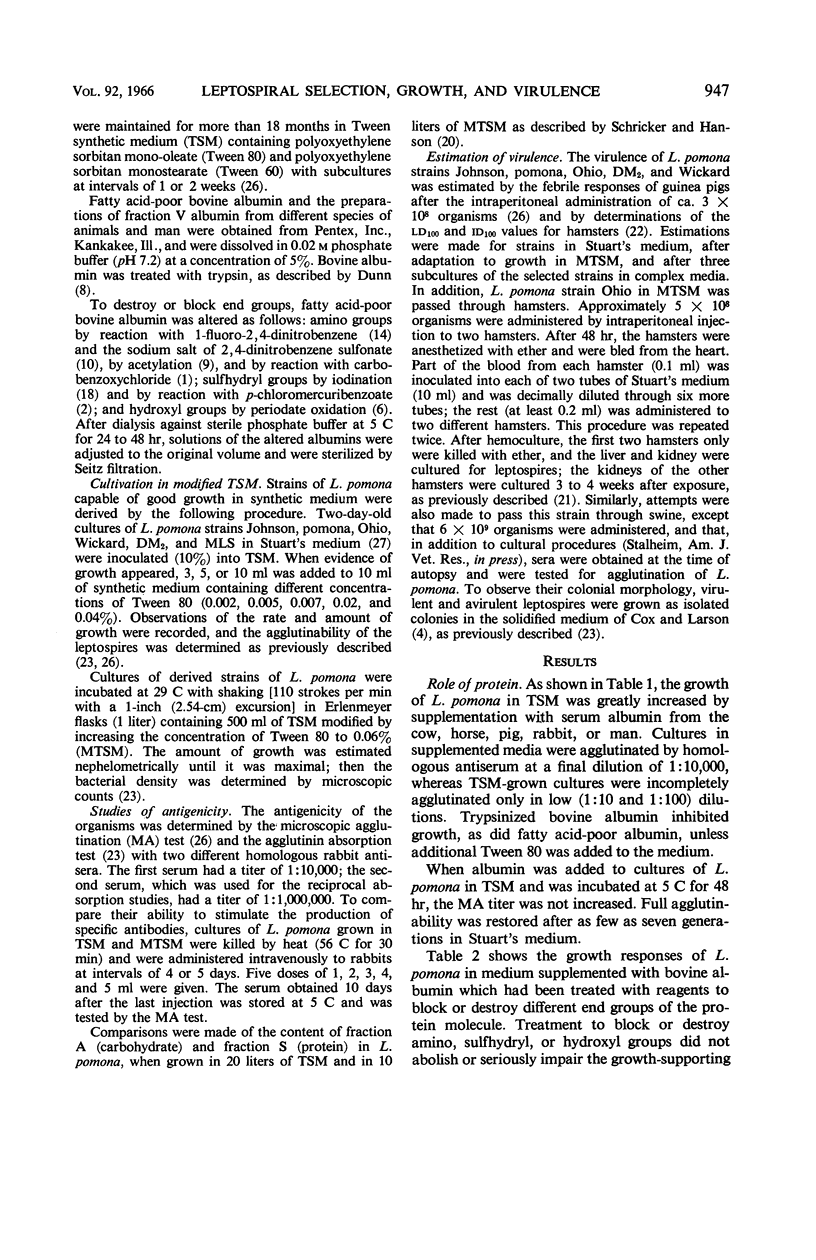

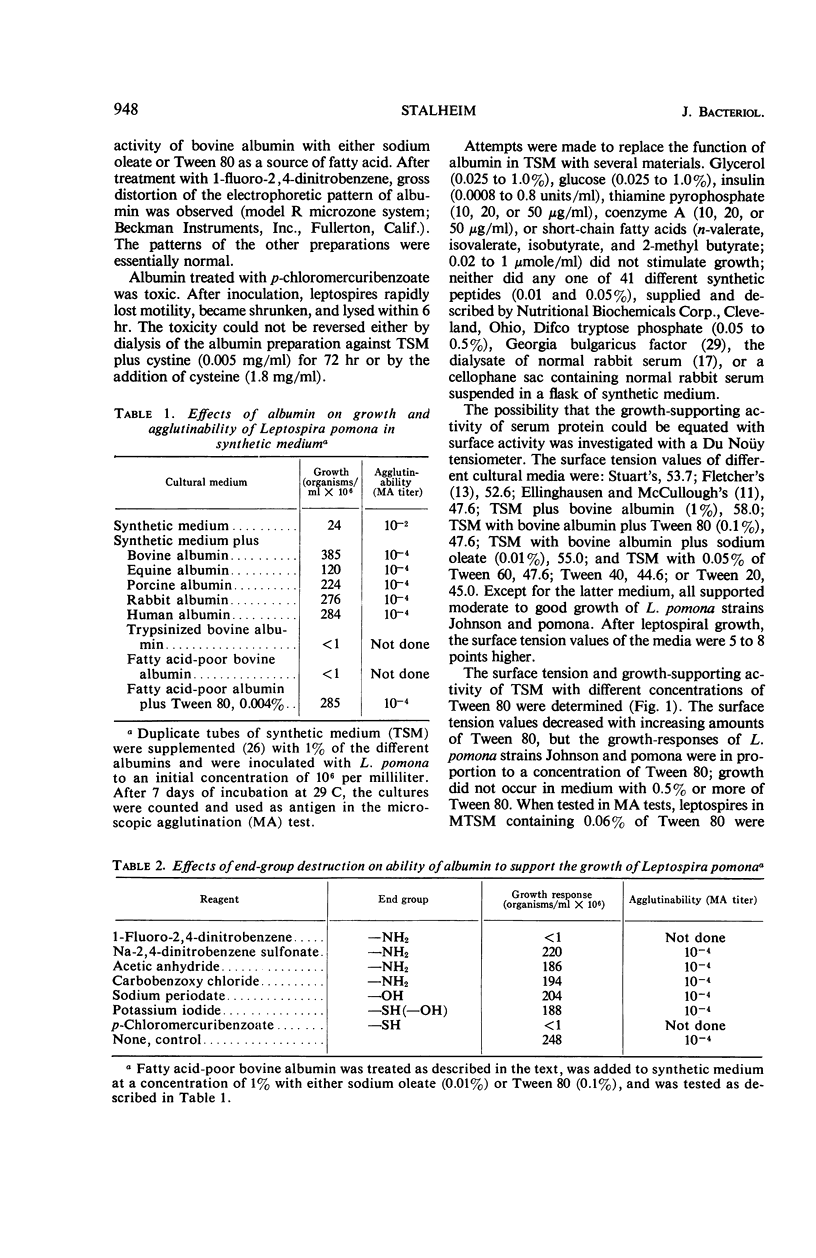

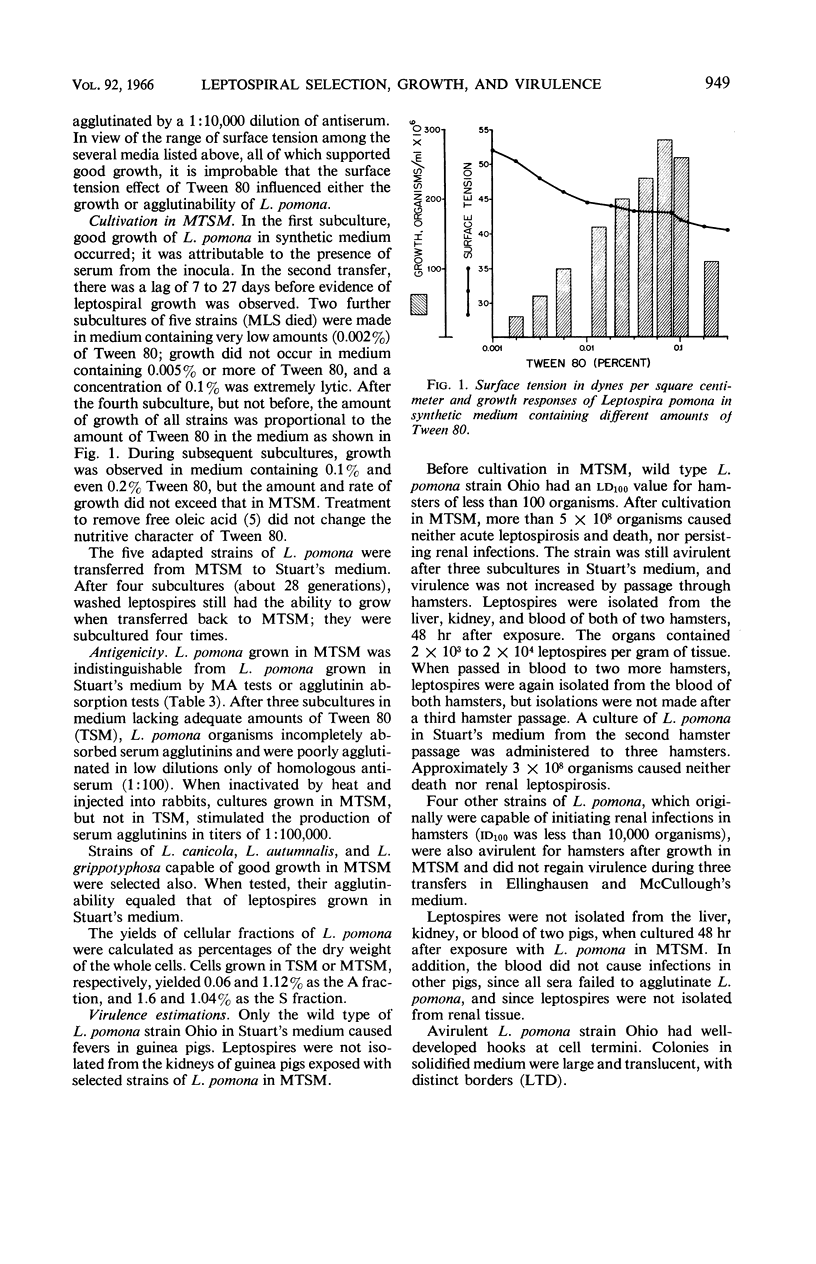

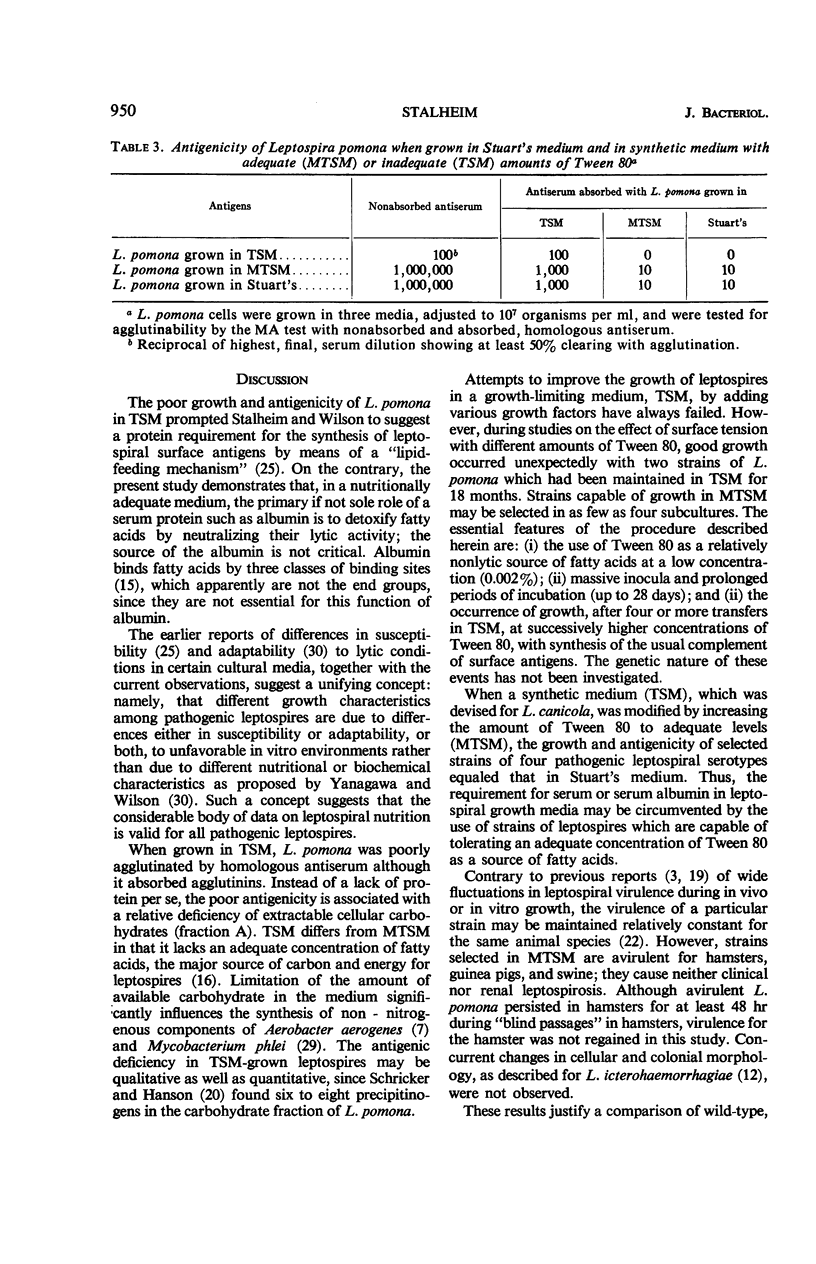

Stalheim, O. H. V. (National Animal Disease Laboratory, Ames, Iowa). Leptospiral selection, growth, and virulence in synthetic medium. J. Bacteriol. 92:946–951. 1966.—The need for protein in leptospiral cultural medium may be circumvented by the use of strains which tolerate the lytic activity of polyoxyethylene sorbitan monooleate (Tween 80), a relatively nonlytic source of essential fatty acids. In an otherwise adequate medium, the primary function of a serum protein (bovine albumin fraction V) in the cultivation of Leptospira pomona was detoxification of fatty acids. Treatment to destroy or block end groups (amino, sulfhydryl, or hydroxyl) did not impair this function, but, after treatment with trypsin, albumin was inactive. Synthetic and derived peptides or polyvinylpyrrolidone did not substitute for albumin. L. pomona grew in medium with surface tension values of 44 to 58 dynes/cm2; after growth, the values were increased slightly (5 to 8). The growth responses did not correlate with the surface tension of the medium, but they were in proportion to the concentration of Tween 80. Of six strains of L. pomona, five were transferred from medium containing rabbit serum and were subcultured in Tween synthetic medium (TSM) containing low, nonlytic concentrations (0.002%) of Tween 80. The poor antigenicity of L. pomona in carbon-limited TSM was associated with a deficiency of those carbonaceous cellular components which were extractable with 50% ethyl alcohol. After as few as four subcultures in TSM, L. pomona tolerated higher concentrations of Tween 80 (0.06% was optimal; MTSM). If grown on a shaker, the rate and amount of growth and the antigenicity of L. pomona in MTSM equaled that in medium supplemented with rabbit serum. After cultivation in MTSM, all of the five strains were avirulent when administered to hamsters, guinea pigs, and swine. They were still avirulent after three subcultures in complex media or after two serial passages in hamsters.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- CHINARD F. P., HELLERMAN L. Determination of sulfhydryl groups in certain biological substances. Methods Biochem Anal. 1954;1:1–26. doi: 10.1002/9780470110171.ch1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COX C. D., LARSON A. D. Colonial growth of leptospirae. J Bacteriol. 1957 Apr;73(4):587–589. doi: 10.1128/jb.73.4.587-589.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUGUID J. P., WILKINSON J. F. The influence of cultural conditions on polysaccharide production by Aerobacter aerogenes. J Gen Microbiol. 1953 Oct;9(2):174–189. doi: 10.1099/00221287-9-2-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLINGHAUSEN H. C., Jr, MCCULLOUGH W. G. NUTRITION OF LEPTOSPIRA POMONA AND GROWTH OF 13 OTHER SEROTYPES: FRACTIONATION OF OLEIC ALBUMIN COMPLEX AND A MEDIUM OF BOVINE ALBUMIN AND POLYSORBATE 80. Am J Vet Res. 1965 Jan;26:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAINE S., VANDERHOEDEN J. VIRULENCE-LINKED COLONIAL AND MORPHOLOGICAL VARIATION IN LEPTOSPIRA. J Bacteriol. 1964 Nov;88:1493–1496. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.5.1493-1496.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRAENKEL-CONRAT H., HARRIS J. I., LEVY A. L. Recent developments in techniques for terminal and sequence studies in peptides and proteins. Methods Biochem Anal. 1955;2:359–425. doi: 10.1002/9780470110188.ch12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON R. C., GARY N. D. NUTRITION OF LEPTOSPIRA POMONA. II. FATTY ACID REQUIREMENTS. J Bacteriol. 1963 May;85:976–982. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.5.976-982.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRESSMAN D., EISEN H. N. The zone of localization of antibodies. V. An attempt to saturate antibody-binding sites in mouse kidney. J Immunol. 1950 Apr;64(4):273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROLLE M., KALICH J. Antagonismus und Virulenzsteigerung der verschiedenen Leptospira-Arten und deren praktische Bedeutung. Berl Tierarztl Wochenschr. 1950 Oct;10:213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRICKER R. L., HANSON L. E. Precipitating antigens of leptospires. I. Chemical properties and serologic activity of soluble fractions of Leptospira pomona. Am J Vet Res. 1963 Jul;24:854–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STALHEIM O. H., WILSON J. B. ANTIGENICITY AND IMMUNOGENICITY OF LEPTOSPIRES GROWN IN CHEMICALLY CHARACTERIZED MEDIUM. Am J Vet Res. 1964 Jul;25:1277–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STALHEIM O. H., WILSON J. B. CULTIVATION OF LEPTOSPIRAE. I. NUTRITION OF LEPTOSPIRA CANICOLA. J Bacteriol. 1964 Jul;88:48–54. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.1.48-54.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STALHEIM O. H., WILSON J. B. CULTIVATION OF LEPTOSPIRAE. II. GROWTH AND LYSIS IN SYNTHETIC MEDIUM. J Bacteriol. 1964 Jul;88:55–59. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.1.55-59.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STALHEIM O. H., WILSON J. B. LEPTOSPIRAL COLONIAL MORPHOLOGY. J Bacteriol. 1963 Sep;86:482–489. doi: 10.1128/jb.86.3.482-489.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalheim O. H. Chemotherapy of renal leptospirosis in hamsters. Am J Vet Res. 1966 May;27(118):803–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEINMAN D. E., MORRIS G. K., WILLIAMS W. L. UNIDENTIFIED GROWTH FACTOR FOR A LACTIC ACID BACTERIUM. J Bacteriol. 1964 Feb;87:263–269. doi: 10.1128/jb.87.2.263-269.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANAGAWA R., WILSON J. B. Two types of Leptospirae distinguishable by their growth in boiled serum medium. J Infect Dis. 1962 Jan-Feb;110:70–74. doi: 10.1093/infdis/110.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]