Abstract

Selection may prove to be a powerful tool for the generation of functional RNAs for in vivo genetic regulation. However, traditional in vitro selection schemes do not mimic physiological conditions, and in vivo selection schemes frequently use small pool sizes. Here we describe a hybrid in vitro/in vivo selection scheme that overcomes both of these disadvantages. In this new method, PCR-amplified expression templates are transfected into mammalian cells, transcribed hammerhead RNAs self-cleave, and the extracted, functional hammerhead ribozyme species are specifically amplified for the next round of selection. Using this method we have selected a number of cis-cleaving hammerhead ribozyme variants that are functional in vivo and lead to the inhibition of gene expression. More importantly, these results have led us to develop a quantitative, kinetic model that can be used to assess the stringency of the hybrid selection scheme and to direct future experiments.

Keywords: hammerhead, ribozyme, in vitro selection, in vivo kinetics

INTRODUCTION

Nucleic acid catalysts may prove to be extremely useful as genetic regulatory elements in vivo (Breaker 2004), including in genetic circuits (Davidson and Ellington 2007). For example, hammerhead ribozymes (HHRz) have been engineered to silence gene expression in vivo. Cleavage has been optimized by identifying target sites on the mRNAs (Scherr et al. 2001) and by controlling the expression level and localization of HHRz (Bertrand et al. 1997). However, although a number of successful examples of HHRz-mediated gene regulation have been reported (for a recent review, see Khan 2006), there have also been a number of examples where HHRz cleavage was not observed to regulate gene expression in vivo (e.g., Tatout et al. 1998; Drew et al. 1999).

It is possible that in vitro selection could be used to optimize functional RNA catalysts, such as the HHRz, for improved performance in vivo. In vitro selection has previously been used to evolve ribozymes (Wilson and Szostak 1999; Chen et al. 2007) and even allosteric ribozymes (Breaker 2002). In particular, selection has previously been used to diversify the cleavage sites that can be utilized by the HHRz (Nakamaye and Eckstein 1994) and to optimize the sequence and function of the catalytic core (Tang and Breaker 1997), the stem-loop II (Long and Uhlenbeck 1994), or both (Ishizaka et al. 1995).

One of the greatest challenges to using HHRzs in vivo is that engineered variants frequently require ∼10 mM Mg2+ to be fully active, while the physiological free Mg2+ is only submillimolar. Therefore, a number of researchers (Zillmann et al. 1997; Conaty et al. 1999; Persson et al. 2002) selected HHRz variants that were active in 1 mM Mg2+ from pools with a minimized stem-loop II. Once the importance of tertiary structural interactions for efficient cleavage at submillimolar Mg2+ concentrations was identified (De la Pena et al. 2003; Khvorova et al. 2003), Burke and colleagues used in vitro selection to successfully engineer two natural HHRzs (schistosomal and PLMV) to perform trans-cleavage reactions at 100 μM Mg2+ (Saksmerprome et al. 2004).

However, magnesium concentration is only one of a number of variables (ionic strength, temperature, interaction with cellular components and compartments) that may limit ribozyme activity in vivo. Therefore, it would be useful to develop in vivo selection procedures that would guarantee that selected molecules are functional in a cellular environment. Many traditional in vivo selection procedures can be described as “phenotype selections” in which each cell possesses a unique variant that in turn produces a particular cellular phenotype—usually, modulation of the production of a genetic reporter. Phenotype selections have previously been used to select or optimize RNA-based regulators such as gene-targeting HHRzs (Unwalla et al. 2008), allosteric HHRzs (Wieland and Hartig 2008), trans-splicing Group I introns (Ayre et al. 2002), riboswitches (Lynch et al. 2007; Nomura and Yokobayashi 2007), and transcription activators (Buskirk et al. 2004). However, the transformation of common experimental organisms such as Escherichia coli or yeast usually limits the pool size in an in vivo phenotype selection to only 106–107 variants (compared with upward of 1014 variants in many in vitro selection experiments). While mammalian cells are easier to transfect, performing phenotype selections in mammalian cells is challenging because it is hard to deliver a single plasmid producing a single ribozyme variant to each cell, and thus active variants can be diluted by inactive ones, limiting either signal or preferential amplification or both.

To avoid these issues, we have developed a scheme we term genotype selection (Fig. 1A), in which a pool of PCR-amplified DNA templates is directly transfected into mammalian cells. The general concept of genotype selection has been previously used to identify exonic splicing enhancers (Coulter et al. 1997), and we now expand this strategy to catalytic RNAs. Following transfection, the RNAs are transcribed, cleaved, and are then extracted. Functional variants are then physically separated from nonfunctional ones in vitro. The functional variants are amplified, and the selected pool of templates is retransfected for additional rounds of selection and amplification.

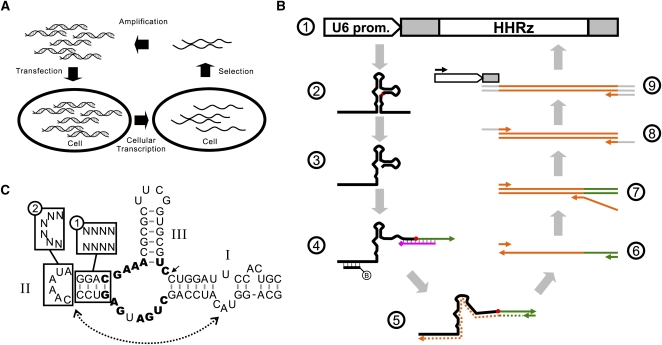

FIGURE 1.

Combined in vitro/in vivo selection for genotype. (A) The general scheme for a combined in vitro/in vivo genotype selection. (B) Detailed procedure for the in vitro/in vivo selection of functional schistosomal HHRz. PCR products encoding U6-driven HHRzs (①) are transfected into mammalian cells. The HHRzs (②) are transcribed, and functional variants yield 5′ cleavage products (③). The 3′ cleavage product is not shown. The 5′ cleavage product can be extracted (via hybridization to a biotinylated capture oligonucleotide) and ligated to a ssDNA adaptor (green in ④, arrow indicates 3′ terminus) in the presence of a splint oligonucleotide. (purple, diamond indicates a block to extension at the 3′ terminus). The extracted ligation product is reverse-transcribed (⑤) and PCR-amplified (⑥). Templates encoding the functional HHRz sequences (⑦), an added spacer (⑧), and the U6 promoter (⑨) were generated by PCRs. In ⑤–⑨, orange, green, gray, and white indicate the HHRz sequence, the adaptor sequence, the spacer sequence, and the U6 promoter, respectively. (C) Design of HHRz pools. Stem II and loop II were randomized in the StemPool (①) and LoopPool (②) constructs, respectively. The dashed line with arrows indicates the tertiary interaction between bulge I and loop II.

Although conceptually straightforward, this scheme faces a number of practical and theoretical challenges. The percentage of transfected DNA that enters the nucleus and is transcribed is low, which necessitates extremely efficient isolation and specific amplification of small amounts of diverse, cleaved ribozymes against a high background of endogenous RNA, template DNA, and nonspecifically degraded ribozymes. Moreover, it is more difficult to control the stringency of selection in vivo than is typically the case in vitro. These challenges required that we devise techniques to ensure the efficient recovery and specific amplification of cleaved ribozymes, and that we establish an in-depth theoretical framework to guide future selections. As a proof of principle, we show that this scheme can yield HHRz variants that are functional and inhibit gene expression in vivo.

RESULTS

Design and validation of selection scheme

In order to directly select for active ribozymes or other functional nucleic acids in vivo, we exploited the fact that PCR-amplified linear expression constructs can be directly introduced into mammalian cells by transfection (Castanotto et al. 2002). Following transcription, active variants will cleave themselves and can subsequently be recovered by lysing cells, isolating the cleaved ribozymes, and ligating primer-binding sequences to the isolated ribozymes.

In greater detail, ribozyme expression cassettes were constructed by using overlap PCR to fuse the U6 promoter with the HHRz (Fig. 1B, step ①). During the construction of the expression cassettes, spacer sequences were introduced both upstream and downstream of the HHRz. The downstream spacer increased the difference in length between the uncleaved precursor and the 5′ cleavage product and thus facilitated size selection on gels, while the upstream spacer assisted with affinity purification during selection (Fig. 1B, step ④).

The PCR-amplified, U6 promoter–driven linear DNA constructs were transfected into HeLa cells, where transcription of the HHRz and its self-cleavage took place (Fig. 1B, steps ②, ③). The use of linear DNA constructs bypasses the ligation step previously employed by Coulter et al. (1997). Ligation typically limits the pool size and at the same time significantly increases the complexity of and time required for selection. After transfection, the total HeLa RNA was extracted with TRIzol and resuspended in denaturing buffer to reduce the self-cleavage of HHRz after RNA preparation. The self-cleaved HHRz molecules were size-selected by denaturing PAGE, eluted into denaturing buffer, ethanol-precipitated, and resuspended in H2O. To prevent degradation products that were of similar size to the authentic self-cleavage product from being amplified, the 5′ self-cleavage product was pretreated with T4 polynucleotide kinase to remove the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate (Cameron and Uhlenbeck 1977) and then ligated to a ssDNA adaptor in a template-dependent manner using a splint oligonucleotide and T4 RNA ligase2 (Fig. 1B, step ④). The RNA/DNA chimera consisting of the 5′ cleavage product of HHRz and the DNA adaptor sequence was purified from excess splint oligonucleotides and adaptors by further hybridizing the HHRz-adaptor to a biotinylated oligonucleotide complementary to the 5′ spacer sequence that was appended to the HHRz. The biotinylated capture oligonucleotide was subsequently captured on a streptavidin-coated resin, and weakly or nonspecifically bound oligonucleotides were removed by multiple washes (Fig. 1B, step ④). The captured RNA was converted to cDNA by reverse transcription (Fig. 1B, step ⑤) and amplified by PCR (Fig. 1B, step ⑥). This amplification step not only prefers authentic cleavage products but also prevents the amplification of contaminating DNA template.

The PCR product corresponding to the cleaved ribozyme was used to build out the full-length HHRz template in a regenerative PCR with a long reverse primer that covered 11 nucleotides (nt) 5′ to the cleavage site and the complete HHRz sequence 3′ to the cleavage site (Fig. 1B, step ⑦). The product of the regenerative PCR was further extended in a third amplification reaction (Fig. 1B, step ⑧) with a spacer sequence that was in turn an anchor for a fourth amplification reaction (Fig. 1B, step ⑨) that again fused the U6 promoter to the 5′ end of the ribozyme, generating a selected expression construct for the next round of selection.

Note that the PCR product derived from the HHRz-adaptor (Fig. 1B, step ⑥) could potentially be extended with the U6 promoter even in the absence of regenerative PCR (Fig. 1B, step ⑦). This would in turn lead to the production of a RNA transcript that would survive the next round of selection even in the absence of cleavage and ligation. To avoid this problem, the adaptor and RT primer sequences were changed in each round (Supplemental Table S1).

While splitting the overall amplification and regeneration of expression constructs into multiple PCR steps may seem unwieldy, it in fact avoids the accumulation of artifacts that could arise from attempting to reconstruct expression constructs in fewer steps, and can readily be carried out by the simple transfer of the products of one amplification reaction to another.

The full selection procedure was first validated using wild-type HHRz (wtHHRz), and A14G-mutant HHRz (mutHHRz), whose self-cleavage activity is known to be abolished (Yen et al. 2004). The transfection of the U6-wtHHRz expression construct resulted in the production of a cleaved transcript 48 h after transfection (Fig. 2A, lane 2); this was not the case for U6-mutHHRz. We also observed a transcript slightly longer than the full-length HHRz in both transfections (Fig. 2A, lanes 2,3), which was probably due to the read-through of the U6 terminator, as has been observed in previous studies (Paul et al. 2003).

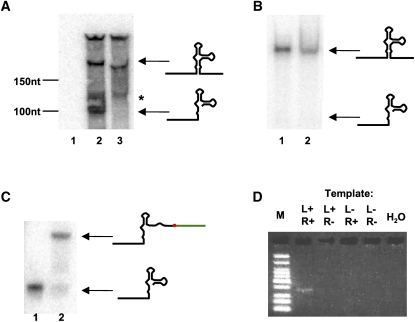

FIGURE 2.

Experimental validation of selection procedure. (A) Transcription in HeLa cells. Northern blotting of the total RNA from untransfected HeLa cells (lane 1) and HeLa cells transfected with U6-wtHHRz (lane 2) and U6-mutHHRz (lane 3) using a radiolabeled ssDNA oligonucleotide complementary to the catalytic core sequence of the HHRz. The upper arrow and lower arrow indicate the positions of the uncleaved HHRz and the 5′cleavage product, respectively. One band of unclear origin (*) was also seen for both transfected samples. (B) HHRz cleavage did not happen during or after RNA isolation. In vitro transcribed, internally radiolabeled wtHHRz precursor was mixed with a TRIzol lysate of HeLa cells, and then whole RNA was extracted from the lysate. The extracted RNA (lane 2) and an internally radiolabeled, uncleaved wtHHRz control (lane 1) were examined by 8% denaturing PAGE and autoradiography. The upper arrow and lower arrows indicate the uncleaved HHRz and 5′ cleavage product, respectively. (C) Dephosphorylation and ligation to an adaptor oligonucleotide were efficient. An in vitro transcribed, internally labeled transcript corresponding to the 5′ cleavage product was spiked into the TRIzol lysate of HeLa cells, and a mock selection was carried out up through the adaptor ligation step (Fig. 1B, Step ④). The extracted RNA (lane 2) and an internally labeled, 5′ cleavage product control (lane 1) were examined by 8% denaturing PAGE and autoradiography. The upper arrow and lower arrows indicate the HHRz:adaptor ligation product and the 5′ cleavage product, respectively. (D) Amplification of the HHRz:adaptor ligation product is ligation and RT dependent. The products of amplification reactions in the presence or absence of various combinations of ligation (L plus or minus) and reverse transcription (R plus or minus; L+R+, L+R−, L−R+, and L−R−) are shown after 35 cycles of PCR on a 4% agarose gel. A negative, no template control reaction is also shown. M: Low molecular-weight ladder (NEB). The results shown in this figure were in fact for the first round of selection of the StemPoolHHRz. PCR from other pools and rounds of selection showed similar results.

We verified that cleavage happened in vivo rather than during or after sample preparation by spiking a radiolabeled full-length wild-type HHRz into the TRIzol lysate. The ribozyme remained intact after RNA preparation (Fig. 2B, lane 2).

To test the overall efficiency of this selection and amplification scheme, a radiolabeled 5′ self-cleavage product was spiked into the TRIzol lysate, followed by extraction, T4 PNK treatment, and template-dependent ligation. As a result, >70% of the radiolabeled could be found ligated to the adaptor sequence (Fig. 2C, lane 2).

Adaptation of the selection scheme to dissecting loop interactions in the HHRz

HHRzs have long served as model systems for studying the biochemistry of RNA catalysis and have proved to be a promising tool for targeting and regulating gene expression. Early research into both the biochemistry and applications of the HHRz were confounded by a lack of detailed knowledge of the tertiary interactions between bulge/loop I and loop II (De la Pena et al. 2003; Khvorova et al. 2003). The molecular basis for this interaction and its role in priming catalysis have been nicely illustrated by the crystal structure of schistosomal HHRz (Martick and Scott 2006). An intricate interaction between bulge I and loop II that involves three noncanonical base pairs and stacking interactions stabilizes the active conformation of the catalytic core.

In order to further understand this tertiary structural interaction, we wanted to determine what variants might stabilize the active conformation in vivo. We therefore randomized Stem II (Pool 1) and Loop II (Pool 2) of the Schistozoma HHRz (Ferbeyre et al. 1998) as starting points for the development of our in vivo selection scheme (Fig. 1C). When the U6-StemPoolHHRz underwent selection, the same, specific PCR product was observed as in previous, control experiments (Fig. 2D). The same result was observed for the U6-LoopPoolHHRz (data not shown).

Functional HHRz selection

Five rounds of in vivo genotype selection were performed for both pools. To allow higher recovery of functional sequences at earlier rounds and higher selection stringency during later rounds, the time between transfection and cell lysis started at 4 h for the stem pool and 8 h for the loop pool in the first round, and this time was gradually reduced to 1.5 h by the fifth round. The initial incubation times were different for the two pools because the number of active variants in the stem pool was expected to be greater than in the loop pool: Any sequence with a paired stem II and a G:C pair adjacent to the catalytic core was expected to be functional (about one in 1000), whereas only the wild-type sequence (CAAACA) in the loop pool was expected to be functional (about one in 4000). We therefore used less stringent selection conditions (longer incubation times) for the loop pool.

Due to the technical challenges of testing the in vivo cleavage rates of the pools, we employed an in vitro cleavage assay at low Mg2+ concentration to initially assess the progression of the selections. As shown in Figure 3, A and B, cleavage activities increase at later rounds of the selection. The activity of the stem pool reached a plateau after five rounds of selection, whereas the activity of the loop pool was still increasing at round 5. Interestingly, there was little change in kobs between rounds, although the fraction of the population that cleaved did increase. This is consistent with our model (below) that shows that the stringency of selection is limited by the mRNA degradation rate.

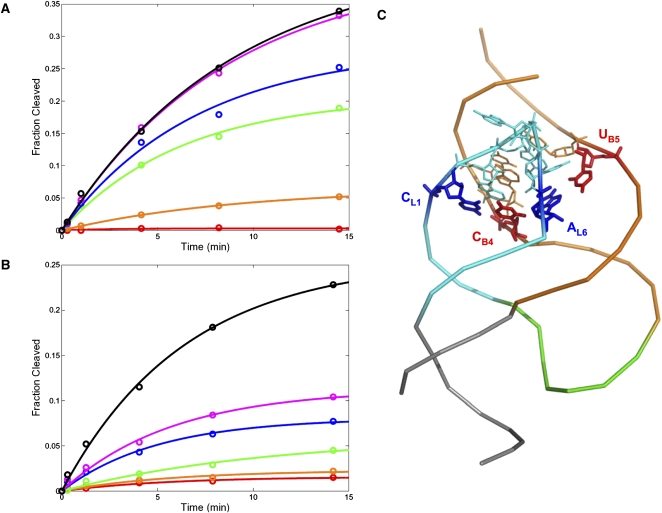

FIGURE 3.

In vitro cleavage assay of selected pools. All reactions were carried out at low (100 μM) Mg2+ concentration. (A) Cleavage kinetics (fitted to a single-exponential equation) for each round of the StemPoolHHRz selection. (B) Cleavage kinetics (fitted to a single-exponential equation) for each round of the LoopPoolHHRz selection. (C) The crystal structure of schistosomal HHRz (Protein Data Bank ID no. 2GOZ) (Martick and Scott 2006) highlighting the bulge I/loop II interaction. The bulged stem I, stem-loop II, stem III, and the single-stranded catalytic core are shown in orange, cyan, gray, and green, respectively. The first nucleotide (CL1) and last nucleotide (AL6) of loop II are shown in blue; and the two nucleotides (CB4 and UB5) that, respectively, form noncanonical base-pairs with them are shown in red.

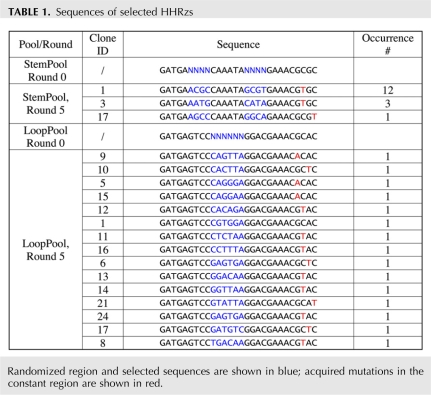

Sequencing of the loop pool revealed that round 5 still contained a diversity of sequences (Table 1), as expected by the fact that the activity of the pool was still increasing. In 14 out of 15 sequences, the last position of the hexameric loop is A (as in the wild-type ribozyme), and the first position is either C (as in the wild-type ribozyme) or G. This consensus is consistent with the role of the first and last nucleotides in loop II in anchoring stem II interactions with bulge I. This can also be seen in the crystal structure of the schistosomal HHRz (Fig. 3C; Martick and Scott 2006).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of selected HHRzs

In contrast, sequencing the StemPool, Round 5, revealed that the pool was dominated by three somewhat surprising sequences (Table 1): 5′-ACGC…GCGU-3′, 5′-AGCC…GGCA-3′, and 5′-AAUG…CAUA-3′, none of which has the known consensus G:C pair at the base of stem II, nearest to the catalytic core. The latter two ribozymes are predicted to have an A:A mismatch at this position. Even though an additional (compared with the consensus HHRz sequence) adenine or uridine has previously been observed at the junction of an otherwise perfectly paired stem II and the catalytic core in some natural HHRzs (Khvorova et al. 2003 and references therein), the A:A mismatch has only been found when hammerhead-like ribozymes were selected in vitro from a completely random sequence population (Salehi-Ashtiani and Szostak 2001). The A:U pair at the base of stem II has not been previously observed. We reason that the less stable A:U pair and A:A mispairs offer amplification advantages in vitro over the G:C pair. This notion was indirectly supported by the fact that point mutations that destabilize stem III (which was not randomized) could be found in many selected sequences (Table 1).

In vivo functionality of selected HHRz variants

As an assay for whether the HHRz and functional variants would be able to inhibit gene expression, we cloned several selected HHRz sequences as well as wtHHRz and mutHHRz controls into the 3′UTR of an mCherry-expression cassette in plasmid p2Color (Supplemental Fig. S1). The p2Color plasmid also contains an EGFP-expressing cassette that serves as internal transfection control. When transfected cells are examined by FACS, it can be seen that, as expected, wtHHRz significantly inhibits the expression of mCherry (almost to the detection limit of this assay) (Fig. 4A; data not shown) whereas mutHHRz did not cause observable inhibition (data not shown).

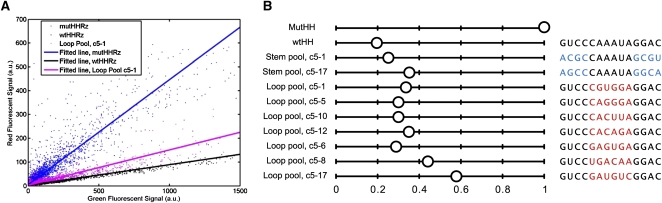

FIGURE 4.

Activities of selected HHRZs in mammalian cells. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of gene-expression inhibition mediated by HHRz cleavage (for data acquisition and processing, see Materials and Methods). The FL2 (red) value was plotted versus the FL1 (green) value on a linear scale for each gated cell. The cells transfected with p2Color-3′wtHHRz, p2Color-3′mutHHRz, and p2Color-3′Lc5-1 (Loop pool, round 5, clone 1) are shown with black, blue, and magenta dots, respectively. The linear regressions for each population are shown in solid lines with the same color coding. (B) The normalized red/green ratios for mutHHRz, wtHHRz, and selected HHRz clones. The stem-loop II sequences for each ribozyme are shown on the right panel. The selected stem and loop sequences are shown in blue and red, respectively.

This assay was used to evaluate selected variants in vivo. Interestingly, while selected HHRz pools were much slower than wtHHRz when tested in vitro, most selected HHRz variants showed strong inhibition in vivo, comparable to that observed with the wtHHRz. In line with our original structural hypothesis, those HHRz variants possessing the (C/G)NNNNA pattern in loop II (predicted to interact with bulge I) showed higher activities in the in vivo reporter assay (Fig. 4B) than did ribozymes without this motif. Moreover, all of the selected stem II HHRz variants were found to be active when assayed in vivo (see Fig. 4B), despite having decidedly nonconsensus base-pairs at the base of stem II.

DISCUSSION

Factors influencing the stringency of in vivo selection

Although it is obvious that physiologically active HHRz can be selected over nonphysiologically active HHRz using our in vivo genotype selection, it is not clear why nonoptimal sequences were chosen. While it is clear that the selection is not stringent enough, the variable that is leading to the survival of mediocre sequences is not immediately apparent. In traditional in vitro selection experiments, faster variants can be selected by reducing the reaction time. However, this strategy is not feasible for our in vivo genotype selection because both the transfection of templates and the transcription of RNA require times that are much longer than the typical cleavage half-life of HHRzs and their variants. For example, transfection takes hours to complete, during which time some templates have already been transcribed and processed (or self-cleaved), while others are still in the process of being transcribed.

Previously Donahue and Fedor (1997) proposed a kinetic model that predicted that, when a self-cleaving ribozyme is placed in the 3′UTR of a mRNA, as long as the cleavage rate constant of the ribozyme was similar to or faster than the degradation rate constant of the mRNA, strong inhibition of gene expression should be observed. We can adopt this kinetic model (Fig. 5) to analyze the variables that impact selection stringency. In this model, the uncleaved precursor of each HHRz variant is transcribed at the same rate (rTxn), and is degraded at the same rate constant (kDegPre) but has a distinct cleavage rate constant (kCle). The 5′ self-cleavage product of each HHRz variant also has the same degradation rate constant (kDeg5′). Since the 5′ cleavage product contains the randomized region and is amplified for the next round of selection, the fitness of each variant is proportional to the concentration of 5′ cleavage product at the point of RNA isolation.

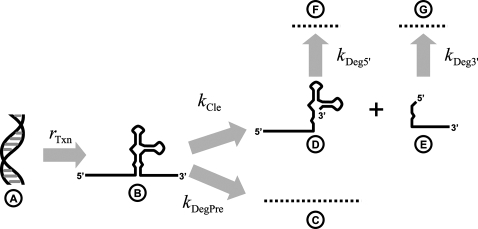

FIGURE 5.

Kinetic model for RNA genotype selection. A is the template DNA; B is the newly transcribed, uncleaved HHRz; C is the degradation product of the uncleaved HHRz; D is the 5′ cleavage product of the HHRz; E is the 3′ cleavage product of the HHRz; F is the degradation product of the 5′ cleavage product; and G is the degradation product of the 3′ cleavage product. The relevant rate constants are rTxn (the zero-order transcription rate constant), kDegPre (the first-order degradation rate constant for the uncleaved HHRz), kCle (the first-order cleavage rate constant for the uncleaved HHRz), kDeg5′ (the first-order degradation rate constant for the 5′ cleavage product), and kDeg3′ (the first-order degradation rate constant for the 3′ cleavage product).

To simplify the model, we assume that RNA transcription, cleavage, and degradation happen in a much shorter time scale than transfection. The concentration of DNA in the cell is assumed to be constant, and the transcription rate, consequently, can also be assumed to be constant. It should be noted that our conclusions remain valid even if the DNA concentration increases over time as a result of continuing transfection or delivery of DNA (simulation result not shown). We also assume that the degradation rates of different 5′ cleavage products in the pool are equivalent.

We first consider the situation where the time span between transfection and RNA isolation are much longer than ln 2/(kCle + kDegPre), in which case the concentration of 5′ cleavage product (c5′) can be seen to be at steady state. Under this condition, we consider the extreme case where degradation of the uncleaved transcript is absent (kDegPre = 0). In this situation, the precursor concentration (cPre) builds up until the cleavage rate (which equals cPre·kCle) approximates the transcription rate of HHRz, which is constant over all HHRz variants. Similarly, the concentration of 5′ cleavage product (c5′) builds up until its degradation rate (which equals c5′·kDeg5′) approximates the cleavage rate of the HHRz, which again approximates the universally equal transcription rate. Thus, at steady state, the concentration of 5′ cleavage product c5′ equals rTxn/kDeg5′, which is completely independent of cleavage rate, and thus there is little or no opportunity to select for improved variants.

In contrast, when the degradation of uncleaved HHRz precursors is greater than zero, the steady-state concentration of precursor becomes rTxn/(kDegPre + kCle) and the steady-state concentration of 5′ cleavage product becomes (rTxn/kDegPre)·[kCle/(kDegPre + kCle)] As shown in Supplemental Figure S1A, the faster cleavage rate constant can provide HHRz variants with a selection advantage, but the extent of the advantage is highly dependent upon the degradation rate constant of the HHRz precursor (kDegPre). The higher kDegPre is, the more stringent the selection is.

Unfortunately, in our selection scheme, kDegPre was determined to be 0.5–1.5 h−1 by quantitative RT-PCR (data not shown), therefore HHRz variants only have to have a kCle of >2 h−1 in order to be selected. Given that the wild-type HHRz has a cleavage rate of 1 min−1 as determined in vitro at physiological Mg2+, the selection was not stringent, and the accumulation of nonoptimized variants was to be expected.

While selection pressure could also be applied by shortening the time span between transfection and RNA isolation, since faster ribozymes reach steady state earlier, this is not really feasible since transfection is necessarily a slow process that likely cannot be shortened to less than 1–2 h, even with electroporation. Given these times, the fitness versus kCle curve is similar to that of the previous steady-state analysis (Supplemental Fig. S1B).

Implications for the development of ribozyme-based regulatory elements

Stable transformation of libraries into cells almost always limits the pool sizes available for directed evolution experiments. To bypass this limitation of pool size while still attempting to adapt ribozymes to the cellular environment, we have developed an in vivo genotype selection that takes advantage of transient transfection of PCR-amplified expression constructs into mammalian cells.

However, one challenge of using this selection scheme compared with traditional in vitro selection methods is that the stringency of selection cannot easily be adjusted. In the current scheme, the longevity of the transcript in which the ribozyme was embedded reduced the stringency of selection, leading to the survival of nonoptimal sequences that differed from the hammerhead consensus and were slower when assayed in vitro. While it is possible that more stringent selection pressure can be applied, decreasing the half-life of uncleaved ribozyme precursors and/or shortening the time span between transfection and cell lysing, it is unlikely that either of these parameters can be reduced to mere minutes or shorter. Therefore, and as our kinetic analyses show, there will likely always be inherent barriers to the selection of fast ribozymes in vivo via genotype selections.

This observation raises the question as to why a G:C pair at the base of stem II of the HHRz, which has higher catalytic activity than the variants selected from stem pool, is observed in nature. The answer is likely twofold. During natural selection, the advantage of fast-cleaving ribozymes may be greatly magnified. However, it is also possible that there may be more HHRzs, including ribozymes that contain A:U and A:A pairs at the base of stem II, than have previously been found, since previous bioinformatics studies have focused on refinding the wild-type template (Ferbeyre et al. 1998; Martick et al. 2008).

However, for many applications it will be the pool size, rather than speed, that is the more important consideration. Even though our proof-of-principle experiments used relatively small pool sizes, the success of these experiments and the method in general suggests that much larger pools can now be sieved in vivo than was previously possible. Despite being ∼100-fold slower than the wild-type in vitro, the selected ribozymes were more than fast enough for efficient gene knockdown in cultured mammalian cells, in part due to the otherwise relatively high stability of mRNA in mammalian cells (as analyzed by Donahue and Fedor [1997] and shown by Yang et al. [2003]).

The finding that “slow” ribozymes may be more than efficient enough for regulating gene expression has additional implications. While the use of allosteric self-cleaving ribozymes to regulate genes in eukaryotic cells has been widely attempted (Link et al. 2007; Win and Smolke 2007, 2008) the dynamic range of regulation has been relatively small. For instance, an allosteric self-cleaving ribozyme (Link et al. 2007) had a cleavage rate constant in the absence of ligand that was 1/100th that of the wild-type schistosomal HHRz (and similar to that of our selected pools), and thus was likely already high enough to achieve substantial gene knockdown even in the absence of ligand. Win and Smolke (2007, 2008) engineered allosteric ribozymes that showed modest (two- to fivefold) activation, and in so doing disrupted loop I/loop II interactions of the TRSV ribozyme, leading to a fivefold reduction in the cleavage (SI Figure 13 of Win and Smolke 2007). Our selection method should prove useful in identifying more dynamic allosteric ribozymes for in vivo applications.

Engineering molecular circuits in vivo is challenging in large measure because the complex systems within a cell can interact with and impact the function of the engineered circuit. Therefore, it is important to establish dynamic, quantitative models that take into account how the circuit and cell may interact. In particular, in order to engineer ribozymes to modulate gene expression, the rates of transcription and degradation, which can significantly alter the behavior of the engineered circuit, must be taken into account. Since the degradation rate constant of the HHRz transcripts by the cellular RNA-degrading machinery (kDegPre) is positively correlated with the stringency of the selection for faster-cleaving HHRzs, it may be important to embed pools in short-lived transcripts (which could in turn be engineered by the introduction of degradation signals) (Noonberg et al. 1996). Moreover, negative selections for allosteric ribozymes that do not cleave in the absence of their effectors should be carried out by transferring a pool to a more stable transcript (Samarsky et al. 1999). The model we have developed can now be used during directed evolution experiments to determine whether and how kinetic parameters of ribozymes in vivo can be selected.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides and pool construction

The oligonucleotides are summarized in Supplemental Table S1 and were obtained form IDT. The oligonucleotides encoding Stem.pool.U and Loop.pool.U were extended via the PCR with the primers Cap.hh.F and hh.t.R. A double-stranded, linear DNA containing the U6 promoter was generated from the template pSIREN-DNR-DsRed (Clontech) in a PCR with the primers U6_5.F and U6_3_Cap.R. The extended pools and the amplified U6 promoter were fused in an overlap PCR with the primers Eco.U6.F and hh.t.R. Overlap PCR was carried out with the KOD polymerase (Novagen), while all other amplifications were carried out with Taq polymerase. EconoSpin columns (Epoch Biolabs) were used to purify PCR products.

Selection procedure

HeLa cells (ATCC) were maintained in MEME (ATCC) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) and 1 U/mL Pen/Strep. One day before transfection, ∼106 cells were seeded in T25 flasks in antibiotic-free MEME with 10% FBS. The cells generally reached 50% confluency at the time of transfection. We mixed 2.5 μg of linear U6-HHRz constructs with 12.5 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) together with 7.5 μg of p2Color, which served as both carrier DNA and as a reporter of transfection efficiency.

From 1.5–8 h after transfection (depending on the round), HeLa cells were trypsinized for 5 min and then resuspended in MEME with 10% FBS. Resuspended cells were centrifuged at 300g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was lysed with 1 mL TRIzol (Invitrogen). Total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions, except that the RNA was resuspended in 20 μL of denaturing elution buffer (DE buffer: 7.8 M urea, 10 mM EDTA at pH 8) to reduce post-extraction ribozyme cleavage. Total RNA was sieved on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel alongside a radiolabeled Decade Ladder (Ambion). After electrophoresis, the gel was briefly visualized using a PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare), and the region corresponding to 90–110 nt was excised, crushed in a 1.5 mL tube, and soaked in 450 μL DE Buffer at 80°C for 10 min. The gel slurry was centrifuged at 16,000g for 2 min and 400 μL of supernatant was transferred to another 1.5 mL tube and ethanol-precipitated with 0.3 M NaAc and 40 μg glycogen (Roche).

Size-selected RNA was resuspended in 16 μL H2O and dephosphorylated at its 3′ end by incubation with 2 μL T4 polynucleotide kinase (10 U/μL, NEB) and 2 μL 10× T4 PNK Buffer (NEB) at 37°C for 30 min. Ligation followed by adding 100 pmole of splint oligonucleotide, 150 pmole of adaptor oligonucleotide, and 1.2 μL of 10 mM ATP and H2O to a total volume of 28 μL. This mixture was heated to 65°C for 5 min and slowly cooled to 25°C at the rate of 0.1°C/sec to allow hybridization of the cleaved HHRz to the splint and adaptor oligonucleotides. A portion (14 μL) of this mixture was transferred to another tube, and 1 μL T4 RNA ligase 2 (NEB) was added. The other half of the sample served as a no-ligation control. Both the ligation reaction and the no-ligation control were subsequently treated equivalently. After 1 h of ligation at 37°C, 1 μL of 50 μM 5′-biotinylated, 2′-O-methyl capture oligonucleotide (complementary to the 5′ spacer sequence on the HHRz-adaptor) was added. The sample was heated to 65°C for 5 min and slowly cooled to 25°C at the rate of 0.1°C/sec to allow hybridization between the capture oligonucleotide and the HHRz-adaptor. The reaction was added to 100 μL UltraLink NeutrAvidin (Pierce) in PBS and incubated for 30 min at 37°C on a rotator. The NeutrAvidin resin was washed three times with 1 mL PBS for to remove excess splint and adaptor oligonucleotides and was then eluted in 450 μL DE Buffer for 10 min at 80°C in the presence of 100 pmole of a DNA oligonucleotide that could compete with the HHRz-adaptor for the capture oligonucleotide. The NeutrAvidin resin was briefly centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected and ethanol-precipitated. The pellet was resuspended in 14 μL of H2O and divided into a 10 μL portion and a 3 μL portion. The 10 μL portion was reverse-transcribed in a total volume of 20 μL with SuperScript III (200 U/μL, Invitrogen) and a primer complementary to the 3′ portion of the adaptor oligonucleotide; the 3 μL portion was to create a mock-RT reaction only lacking SuperScript III.

In the end, four different samples covering two independent controls could be compared with one another: ligation+RT+ (L+R+ in 20 μL), L+R− in 6 μL, L−R+ in 20 μL, and L−R− in 6 μL. Aliquots (1 μL) from each reaction were used as templates in trial PCRs to verify that only the L+R+ sample yielded an amplification product and to estimate the optimal number of thermal cycles to obtain a clean product. A larger aliquot (10 μL) of the L+R+ sample was then amplified in 10 individual PCR reactions using the optimal thermal cycle number; this product was in turn used as the template for regenerative PCR (Fig. 1B, step ⑦). The regenerative PCR product was finally used to generate the U6-HHRz construct via a series of PCRs (Fig. 1B, steps ⑧, ⑨), as described above for pool construction.

In vitro cleavage assay

The T7 RNA polymerase promoter was added to HHRz constructs by amplifying PCR products with flaking spacers (Fig. 1B, step ⑧) with primers T7_Cap.F and hh.t.R. The templates were transcribed in vitro using the AmpliScribe T7 kit (Epicentre) and trace amounts of [α-32P] ATP (3000 Ci/mmole, PerkinElmer). An anti-HHcore RNA (20 μM) (aN79coreRNA in Supplemental Table S1) was added to the transcription reaction to reduce self-cleavage. After 15 min of transcription, 1 μL of DNase I (1 U/μL, Ambion) was added to digest the DNA template, after which the whole transcription reaction was passed through an illustra MicroSpin G-25 Column (GE Healthcare) to remove unused nucleotides. The eluate was mixed with an equal volume of denaturing loading buffer (DL Buffer: 7.8 M urea, 10 mM EDTA, spiked with xylene cyanol, and bromophenol blue) and heated to 80°C for 10 min. RNA substrates and products were separated by electrophoresis on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. After brief exposure of the gel on a PhosphorImager, the region containing the uncleaved HHRz (typically, 80%–90%) was excised, crushed and soaked in 400 μL DE Buffer for 10 min at 80°C. The eluate was ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 20 μL of prereaction buffer (PR buffer: 50 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 100 μM EDTA), heated to 80°C for 1 min, and slowly cooled to 25°C at the rate of 0.1°C/sec. The reaction was initiated by adding 5 μL PR Buffer supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2 (PRMg Buffer) to the HHRz in 20 μL PR Buffer at 25°C (final free Mg2+ concentration 100 μM). Reactions were carried out at room temperature rather than 37°C in order to better control the rate of reaction initiation over multiple samples; no changes in rank ordering were seen in reactions done at 25°C rather than 37°C. At each time point indicated in Figure 3, A and B, 5 μL of the reaction was mixed with 5 μL stop buffer (ST Buffer: 95% formamide, spiked with xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue). The samples were heated to 80°C for 10 min and separated by 8% denaturing PAGE. Gels were dried and analyzed on a PhosphorImager. Bands representing uncleaved and cleaved HHRz were quantified using ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics). The amounts of substrates and products were normalized to one another by dividing by expected number of adenines in each fragment.

Northern blotting

Northern blot analysis followed the protocol optimized by the Ruvkun Laboratory and the Bartel Laboratory (Pasquinelli et al. 2000). Briefly, 20 μg of total RNA and a readily detectable amount of radiolabeled Decade Ladder (Ambion) were run on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 1× TBE and then transferred to GeneScreen Plus membrane (PerkinElmer) with 1× TBE. A probe oligonucleotide (20 pmole of aN79coreSp3) (Supplemental Table S1) was end-labeled with 1 μL T4 PNK (10 U/μL, NEB) and 2.5 μL [γ-32P] ATP (5000 Ci/mmole, 10 Ci/mL, PerkinElmer) and then purified using an illustra MicroSpin G-25 Column (GE Healthcare). The radiolabeled probe was applied to the blot in Prehyb/Hyb Solution (5× SSC, 20 mM Na2HPO4 at pH7.2, 7% SDS, 2× Denhardt's) overnight at 50°C. The membrane was washed with Nonstringent Wash Solution (3× SSC, 25 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.5, 5% SDS, 10× Denhardt's) four times and with Stringent Wash Solution (1× SSC, 1% SDS) twice. The membrane was then sealed in a plastic bag and exposed to a PhosphorImager plate overnight.

Cell-based reporter assay

The p2Color plasmid was constructed by inserting the mCherry-coding sequence between the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) and replacing the neomycin-resistant gene (SmaI-BstBI fragment) with the EGFP-coding sequence. Different HHRz sequences were then inserted between the EcoRI and NotI sites of the p2Color plasmid to give rise to a series of p2Color-3′hh plasmids.

HeLa cells were seeded in a 12-well plate (4cm2 per well, Greiner Bio One) 1 d before transfection so that cells reached ∼70% confluency at the time of transfection. A p2Color-3′hh series plasmid (400 ng) was transfected using 2 μL Lipofectamine 2000 together with 1200 ng pUC19 as carrier DNA. Two days after transfection, cells were trypsinized and FACS analysis was carried out on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). The FL1 (representing green fluorescent signal) and FL2 (representing red fluorescent signal) values were recorded on a logarithm scale and the color compensation was set to “FL1-0%FL2” and “FL2-30%FL1.” Total events were gated using WinMDI software (version 2.8, http://facs.scripps.edu/software.html) to plot forward versus side scatter and identify intact, nonaggregated cells. The FL1 and FL2 values were then exported to Matlab and converted to a linear scale, from which the red/green ratio was calculated as the slope of the linear regression. The red/green ratio associated with each p2Color-3′wtHHRz series plasmid was normalized by dividing it by the red/green ratio of the negative control p2Color-3′mutHHRz, leading to the normalized red/green ratios that are reported in Figure 4B.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material can be found at http://www.rnajournal.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM077040) and the Welch Foundation (F-1654).

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1635209.

REFERENCES

- Ayre BG, Kohler U, Turgeon R, Haseloff J. Optimization of trans-splicing ribozyme efficiency and specificity by in vivo genetic selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E, Castanotto D, Zhou C, Carbonnelle C, Lee NS, Good P, Chatterjee S, Grange T, Pictet R, Kohn D, et al. The expression cassette determines the functional activity of ribozymes in mammalian cells by controlling their intracellular localization. RNA. 1997;3:75–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaker RR. Engineered allosteric ribozymes as biosensor components. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002;13:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaker RR. Natural and engineered nucleic acids as tools to explore biology. Nature. 2004;432:838–845. doi: 10.1038/nature03195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buskirk AR, Landrigan A, Liu DR. Engineering a ligand-dependent RNA transcriptional activator. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron V, Uhlenbeck OC. 3′-Phosphatase activity in T4 polynucleotide kinase. Biochemistry. 1977;16:5120–5126. doi: 10.1021/bi00642a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanotto D, Li H, Rossi JJ. Functional siRNA expression from transfected PCR products. RNA. 2002;8:1454–1460. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202021362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Li N, Ellington AD. Ribozyme catalysis of metabolism in the RNA world. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:633–655. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaty J, Hendry P, Lockett T. Selected classes of minimised hammerhead ribozyme have very high cleavage rates at low Mg2+ concentration. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2400–2407. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.11.2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter LR, Landree MA, Cooper TA. Identification of a new class of exonic splicing enhancers by in vivo selection. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2143–2150. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EA, Ellington AD. Synthetic RNA circuits. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:23–28. doi: 10.1038/nchembio846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Peña M, Gago S, Flores R. Peripheral regions of natural hammerhead ribozymes greatly increase their self-cleavage activity. EMBO J. 2003;22:5561–5570. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue CP, Fedor MJ. Kinetics of hairpin ribozyme cleavage in yeast. RNA. 1997;3:961–973. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew HR, Lewy D, Conaty J, Rand KN, Hendry P, Lockett T. RNA hairpin loops repress protein synthesis more strongly than hammerhead ribozymes. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:260–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbeyre G, Smith JM, Cedergren R. Schistosome satellite DNA encodes active hammerhead ribozymes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3880–3888. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaka M, Ohshima Y, Tani T. Isolation of active ribozymes from an RNA pool of random sequences using an anchored substrate RNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;214:403–409. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AU. Ribozyme: A clinical tool. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;367:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khvorova A, Lescoute A, Westhof E, Jayasena SD. Sequence elements outside the hammerhead ribozyme catalytic core enable intracellular activity. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:708–712. doi: 10.1038/nsb959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link KH, Guo L, Ames TD, Yen L, Mulligan RC, Breaker RR. Engineering high-speed allosteric hammerhead ribozymes. Biol Chem. 2007;388:779–786. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long DM, Uhlenbeck OC. Kinetic characterization of intramolecular and intermolecular hammerhead RNAs with stem II deletions. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:6977–6981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SA, Desai SK, Sajja HK, Gallivan JP. A high-throughput screen for synthetic riboswitches reveals mechanistic insights into their function. Chem Biol. 2007;14:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martick M, Scott WG. Tertiary contacts distant from the active site prime a ribozyme for catalysis. Cell. 2006;126:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martick M, Horan LH, Noller HF, Scott WG. A discontinuous hammerhead ribozyme embedded in a mammalian messenger RNA. Nature. 2008;454:899–902. doi: 10.1038/nature07117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamaye KL, Eckstein F. AUA-cleaving hammerhead ribozymes: attempted selection for improved cleavage. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1271–1277. doi: 10.1021/bi00171a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura Y, Yokobayashi Y. Reengineering a natural riboswitch by dual genetic selection. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13814–13815. doi: 10.1021/ja076298b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonberg SB, Scott GK, Benz CC. Evidence of post-transcriptional regulation of U6 small nuclear RNA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10477–10481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, Hayward DC, Ball EE, Degnan B, Muller P, et al. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature. 2000;408:86–89. doi: 10.1038/35040556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul CP, Good PD, Li SX, Kleihauer A, Rossi JJ, Engelke DR. Localized expression of small RNA inhibitors in human cells. Mol Ther. 2003;7:237–247. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(02)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson T, Hartmann RK, Eckstein F. Selection of hammerhead ribozyme variants with low Mg2+ requirement: Importance of stem-loop II. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:1066–1071. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20021104)3:11<1066::AID-CBIC1066>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saksmerprome V, Roychowdhury-Saha M, Jayasena S, Khvorova A, Burke DH. Artificial tertiary motifs stabilize trans-cleaving hammerhead ribozymes under conditions of submillimolar divalent ions and high temperatures. RNA. 2004;10:1916–1924. doi: 10.1261/rna.7159504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi-Ashtiani K, Szostak JW. In vitro evolution suggests multiple origins for the hammerhead ribozyme. Nature. 2001;414:82–84. doi: 10.1038/35102081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarsky DA, Ferbeyre G, Bertrand E, Singer RH, Cedergren R, Fournier MJ. A small nucleolar RNA:ribozyme hybrid cleaves a nucleolar RNA target in vivo with near-perfect efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:6609–6614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr M, LeBon J, Castanotto D, Cunliffe HE, Meltzer PS, Ganser A, Riggs AD, Rossi JJ. Detection of antisense and ribozyme accessible sites on native mRNAs: Application to NCOA3 mRNA. Mol Ther. 2001;4:454–460. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Breaker RR. Rational design of allosteric ribozymes. Chem Biol. 1997;4:453–459. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatout C, Gauthier E, Pinon H. Rapid evaluation in Escherichia coli of antisense RNAs and ribozymes. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1998;27:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwalla HJ, Li H, Li SY, Abad D, Rossi JJ. Use of a U16 snoRNA-containing ribozyme library to identify ribozyme targets in HIV-1. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1113–1119. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland M, Hartig JS. Improved aptazyme design and in vivo screening enable riboswitching in bacteria. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:2604–2607. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS, Szostak JW. In vitro selection of functional nucleic acids. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:611–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Win MN, Smolke CD. A modular and extensible RNA-based gene-regulatory platform for engineering cellular function. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:14283–14288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703961104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Win MN, Smolke CD. Higher-order cellular information processing with synthetic RNA devices. Science. 2008;322:456–460. doi: 10.1126/science.1160311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, van Nimwegen E, Zavolan M, Rajewsky N, Schroeder M, Magnasco M, Darnell JE., Jr Decay rates of human mRNAs: Correlation with functional characteristics and sequence attributes. Genome Res. 2003;13:1863–1872. doi: 10.1101/gr.1272403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen L, Svendsen J, Lee JS, Gray JT, Magnier M, Baba T, D'Amato RJ, Mulligan RC. Exogenous control of mammalian gene expression through modulation of RNA self-cleavage. Nature. 2004;431:471–476. doi: 10.1038/nature02844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zillmann M, Limauro SE, Goodchild J. In vitro optimization of truncated stem-loop II variants of the hammerhead ribozyme for cleavage in low concentrations of magnesium under non-turnover conditions. RNA. 1997;3:734–747. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]