Abstract

Aims

FoxO4 is a member of the forkhead box transcription factor O (FoxO) subfamily. FoxO proteins are involved in diverse biological processes. In this study, we examine the role of FoxO4 in intestinal mucosal immunity and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Methods

Foxo4-null mice were subjected to trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-treatment. Microarray analysis and quantitative RT-PCR were used to identify the cytokine transcripts that were altered by Foxo4-deletion. The effects of Foxo4-deficiency on the intestinal epithelial permeability and levels of tight junction proteins were examined by permeable fluorescent dye and western blot. The molecular and cellular mechanism(s) by which FoxO4 regulates the mucosal immunity were explored through immunological and biochemical analyses. The expression level of FoxO4 in intestinal epithelial cells of patients with IBD was examined using immunohistochemistry.

Results

Foxo4-null mice were more susceptible to TNBS injury induced colitis. The chemokine CCL5 is significantly up-regulated in the colonic epithelial cells of Foxo4-null mice, with increased recruitment of CD4+ intraepithelial T cells and up-regulation of cytokines INFγ and TNFα in the colon. Foxo4-deficiency also resulted in an increase in intestinal epithelial permeability and downregulation of the tight junction proteins ZO-1 and claudin-1. Mechanistically, FoxO4 inhibited the transcriptional activity of NF-κB and Foxo4-deficiency is associated with increased NF-κB activity in vivo. FoxO4 transcription is transiently repressed in response to TNBS treatment and in patients with IBD.

Conclusion

These results indicate that FoxO4 is an endogenous inhibitor of NF-κB and identify a novel function of FoxO4 in the regulation of NF-κB mediated mucosal immunity.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a complex group of chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract that affect more than one million individuals in the United State and several millions worldwide (1). IBD comprises two prototypes, ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). The etiology of IBD remains unknown. It is widely believed that different genetic defects coupled with environmental antigens may contribute to the pathogenesis of different sub-types of IBD (2, 3). Because identification of the relevant susceptibility genes might provide a key step to understanding the disease pathogenesis, there are intense efforts to search for these genes and to understand their molecular functions.

The biological functions of IBD susceptibility genes are related to mucosal immunity and intestinal epithelial barrier function (2–4). As the gut is continuously exposed to a vast array of microorganisms and dietary antigens, there is a low-grade chronic mucosal inflammation that generates protective responses to combat possible injurious effects by this wide array of antigens. This low grade inflammation is normally tightly controlled under physiological conditions. Susceptibility alleles contribute to a break-down in this control circuitry, resulting in excessive immune responses to normal gut microflora that drive the development of the disease.

The intestinal epithelium provides barrier functions between the luminal triggers and the host. Impaired barrier function could lead to increased uptake of luminal antigens that promote mucosal inflammation. The intestinal barrier is formed by the epithelial cells and the junctional complexes including tight junctions (TJs) (5, 6). Patients with CD have a defective intestinal TJ barrier and abnormally high paracellular permeability (4, 6). A permeability defect may be an early event of IBD as increased intestinal epithelial permeability precedes clinical relapse in asymptomatic CD patients and in some healthy close relatives of the patients (4).

FoxO4 is a member of the forkhead box transcription factor O (FoxO) subfamily that also includes FoxO1, FoxO3, and FoxO6. FoxO proteins are involved in diverse cellular functions including regulation of the immune response (7–12). Foxo3-deficient T cells are hyperactivated with increased production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines (9). FoxO1 regulates transcriptional programs involved in early B cell development and peripheral B cell function (10). As individual members of the FoxO family have unique cell type-specific functions and their regulation of target genes is context-dependent (11, 12), it remains to be determined whether FoxO4 has a similar immunoregulatory activity and whether FoxO proteins have a role in innate immunity and in inflammatory diseases.

In this study, we investigated the role of FoxO4 in IBD using an animal model of colitis. Our results indicate that Foxo4-null mice have elevated susceptibility to TNBS injury induced colitis compared to wild type (WT) littermates, increased mucosal expression of proinflammatory cytokines, and intestinal epithelial permeability. Mechanistically, we found that FoxO4 interacts with NF-κB and inhibits its DNA binding and transcriptional activity. Furthermore, we showed that patients with IBD have decreased epithelial expression of FoxO4 that mirrors the expression profile of FoxO4 in colonic mucosa of mice during inflammation.

Results

Foxo4-null mice exhibit exacerbated inflammatory response to TNBS treatment

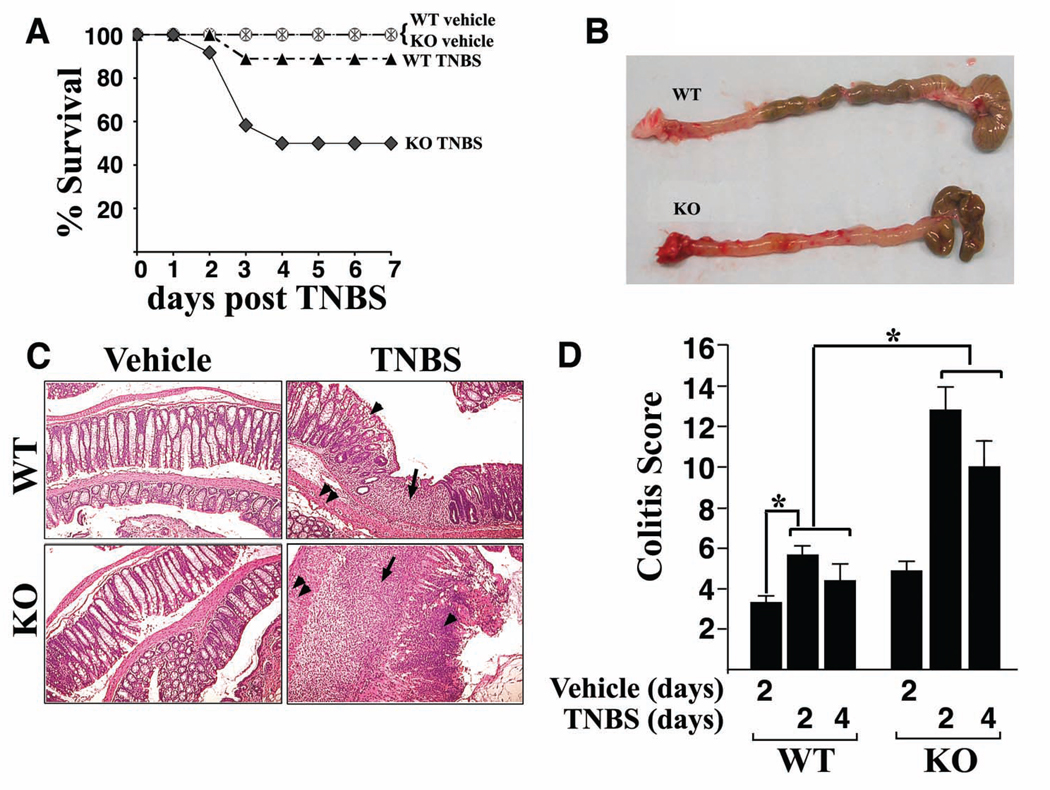

Foxo4-null mice were generated on FVB/N background and appeared generally healthy and fertile (11). Study of the large and small intestines did not show discernable histopathological anomalies under normal conditions (11; this study). Given the role of various FoxO family members in immunocyte biology, we considered the possibility that Foxo4-deficiency might render mice differentially responsive to inflammatory stimuli. To test this hypothesis, we subjected Foxo4-null and WT littermates to intra-rectal administration of a single dose of TNBS in ethanol. As shown in Figure 1A, Foxo4 knock out (KO) mice showed significantly higher mortality compared to WT controls following TNBS-treatment. The colons of survival TNBS-treated Foxo4 KO mice were found to be severely inflamed and hyperemic and contained less feces due to massive diarrhea (Figure 1B). The histological features of TNBS-treated Foxo4 KO mice include transmural inflammation, infiltration of lymphocytes, loss of goblet cells, and thickening of the vascular wall, characteristic of T helper cell type 1 (Th1)-mediated inflammation (Figure 1C). Focal ulceration and crypt architectural abnormalities were also observed. Quantification of the inflammation shows a small but significant degree of colitis in WT mice and further increased colitis score in Foxo4 KO mice (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Deletion of Foxo4 results in exacerbated TNBS injury induced colitis.

(A) Survival of mice given a single dose of ethanol (wt, circle, n=5; Foxo4 KO, star, n=5) or TNBS enema (wt, solid triangle, n=9; Foxo4 KO, solid diamond, n=12). (B) Macroscopic changes of colons of WT (top panel) and Foxo4 KO mice (lower panel) 4 days after the initial rectal TNBS administration. (C) H&E staining of colonic morphology in control and TNBS-treated WT and Foxo4 KO mice. In TNBS-treated Foxo4 KO mice, there is a significant increase in lymphocytic infiltration (black arrows), loss of goblet cells (arrow heads), and thickening of vascular wall (double arrow heads). (D) The inflammation in C was quantified as colitis score (n=6 ± SEM for each genotype, *, p<0.05).

Inflammatory cytokines are up-regulated in colons of Foxo4 KO mice

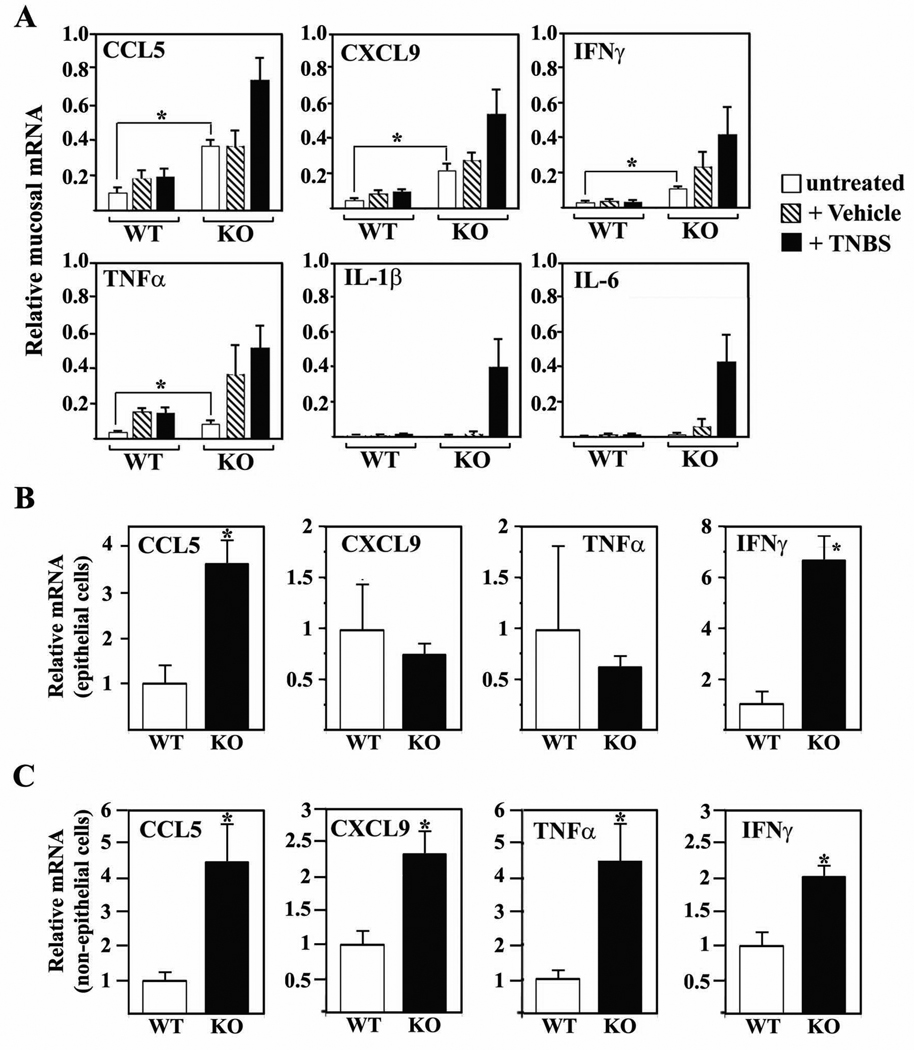

To understand the mechanism of elevated colitis susceptibility and the nature of the TNBS-induced colitis in Foxo4-null mice, we performed microarray analysis with mucosal cDNA samples from colons of untreated, ethanol and TNBS-treated WT and Foxo4-null mice. Unexpectedly, we found that cytokine CCL5, CXCL9, TNFα, and IFNγ, which are known to be involved in pathogenesis of IBD, were already significantly upregulated in untreated Foxo4-null mice compared to WT controls despite lack of visible colonic phenotypes (Figure 2A). Consistent with the exacerbated inflammatory phenotype in TNBS-treated Foxo4-null mice, the expression levels of these inflammatory cytokines are further upregulated after TNBS-treatment. In addition, we observed many more inflammatory cytokines that were upregulated in TNBS-treated Foxo4-null mice (for details, see Supplemental Table 1–Supplemental Table 3). Up-regulation of basal level of IFNγ, TNFα, CCL5, and CXCL9 expression in Foxo4-null mice is specific to colonic tissues, as no significant difference of mRNAs of these cytokines between WT and Foxo4-null mice was observed in other tissues, including thymus (Supplemental Figure S1A) and spleen (data not shown). We also tested whether the expressions of Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) and Th17 cytokines (IL-12, IL-17, and IL-23) are altered between WT and Foxo4-null mice under either basal or TNBS-treated conditions, and observed no significant differences (data not shown).

Figure 2. Inflammatory cytokines are upregulated in colons of FoxO4 KO mice.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of RNA transcripts from colonic mucosa of untreated, vehicle, and TNBS treated WT and Foxo4 KO mice (n=4 ± SEM, *, p < 0.05). Transcript levels are expressed relative to an internal control (GAPDH). (B) Relative mRNA of CCL5, CCL9, TNFα, and IFNγ from intestinal epithelial cells and (C) from epithelial-minus mucosal cell fraction (n=4 ± SEM, *, p<0.05). After normalizing to an internal control (GAPDH), the transcript level in WT was set to 1 and levels in KO were expressed as relative to WT.

As epithelial cells can also synthesize chemokines and cytokines that attract colonic lymphocytes in response to inflammatory stimuli (13), we wished to know the contribution of the epithelial cells to the increased inflammatory cytokines observed in Foxo4-null mice. We separated the colonic mucosal samples into two fractions; epithelial and non-epithelial cell populations. The non-epithelial cell population contains mixtures of predominantly intraepithelial lymphocytes, lymphocytes of lamina propria, and fibroblasts. Subsequent qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the chemokine CCL5 and the cytokine IFNγ from Foxo4-null mice are significantly up-regulated in both epithelial and non-epithelial cell populations (Figure 2, B and C). Transcript levels of TNFα and CXCL9 from Foxo4 KO mice were similar to those from WT mice in the epithelial cell fraction, but significantly higher in the non-epithelial cell population (Figure 2, B and C). We also examined the levels of Foxo3 and Foxo1 in both WT and Foxo4 KO cells, and observed no significant difference (Supplemental Figure S1B).

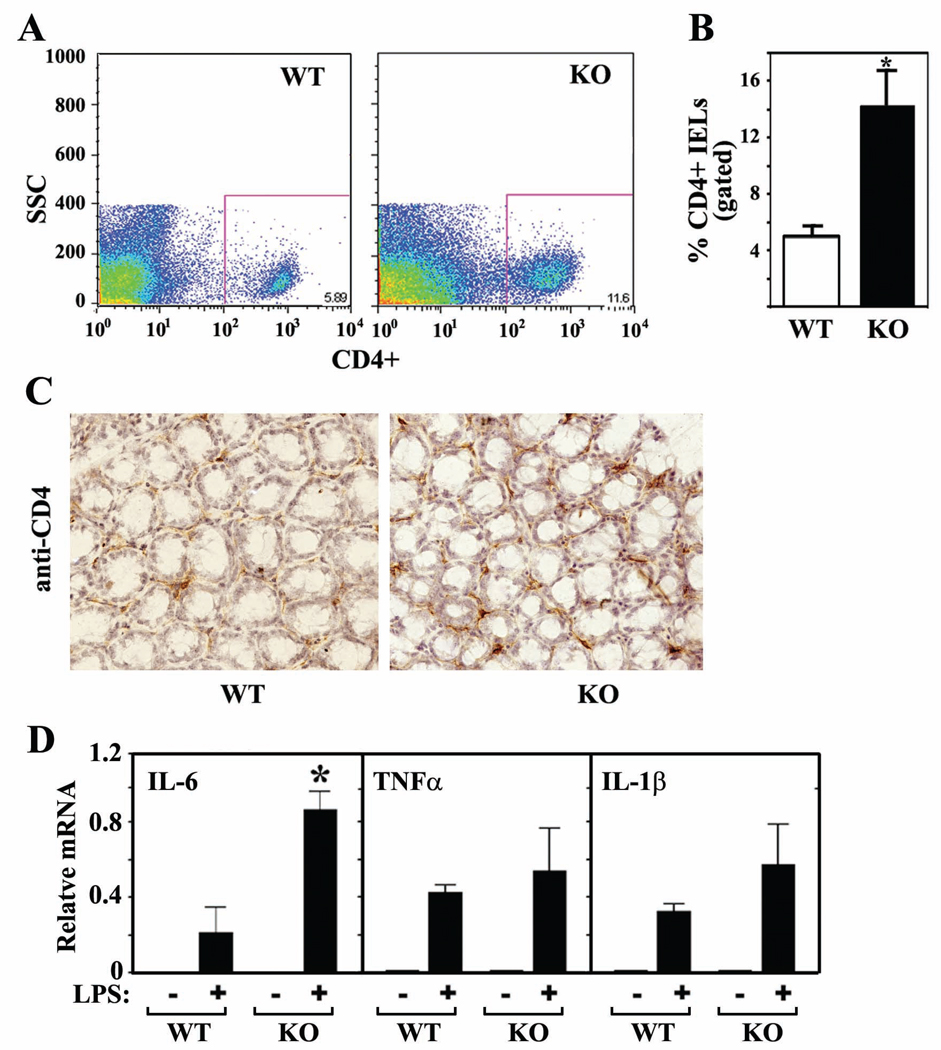

Intraepithelial CD4+ lymphocytes are increased in Foxo4 KO mice

Upregulation of cytokines in the non-epithelial cell population of Foxo4-null mucosa suggested involvement of mucosal lymphocytes, either increased number of lymphocytes or altered ability to produce higher levels of cytokines. To test these possibilities, intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) were isolated from untreated colons of WT and Foxo4 KO mice, labeled with various specific antibodies, and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. There was a significant increase in the percent of CD4+ IELs in Foxo4-KO mice compared to that in WT mice (Figure 3, A and B). The increased amount of CD4+ IELs in Foxo4 KO mice was further confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 3C, Supplemental Figure S2). These results suggest that the elevated levels of cytokines CCL5, CXCL9, TNFα, and IFNγ in colonic mucosa of Foxo4-null mice could be at least partially attributable to increased CD4+ T cells. We have also attempted to quantify the difference of the CD11+ dendritic cells between WT and Foxo4-null mice. The data were not conclusive because of the low yield of CD11+ cells (data not shown).

Figure 3. CD4+ IELs are upregulated in colons of Foxo4 KO mice.

(A and B) Relative percentages of CD4+ IELs from colons of WT and Foxo4-KO mice were analyzed by flow cytometry on the basis of forward/side scatter-based lymphocyte gating (n=3 ± SEM, *, p<0.05). (C) Colonic CD4+ IELs were stained with anti-CD4 antibody (dark brown) in an immunohistochemistry assay. A representative IHC staining from three different mice per genotype is shown. (D) Relative mRNA in peritoneal macrophages stimulated with or without LPS (n=3 ± SEM, *, p<0.05).

As Foxo4 is also expressed in the mucosal lymphocytes including macrophages (Supplemental Figure S3), we tested whether Foxo4-deficient macrophages have altered ability to produce inflammatory cytokines in response to antigens. We isolated peritoneal macrophages from both WT and Foxo4-null mice and stimulated the cells with LPS in culture. Foxo4-decificient macrophages produced significantly higher levels of IL-6 in response to LPS than WT control cells (Figure 3D).

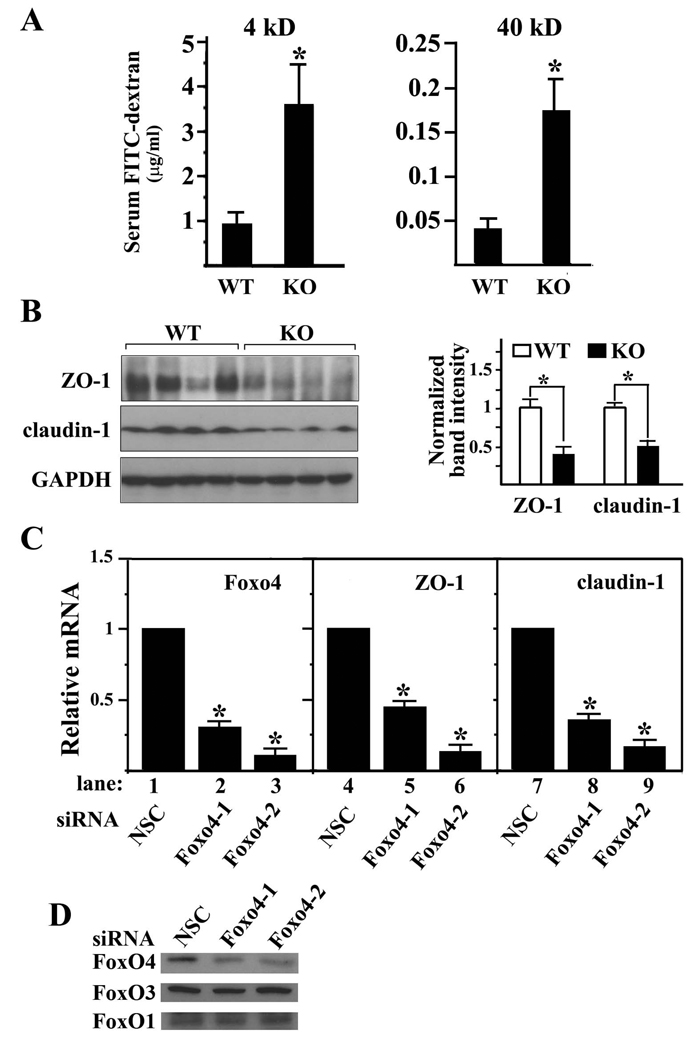

Given the increased number of activated colonic T cells and proinflammatory cytokine profile of Foxo4-null mice, we sought to address whether this immune picture might relate to defects of intestinal epithelial barrier function. We measured the epithelial permeability by orally gavaging mice with fluorescent permeability markers (4kD and 40kD FITC-dextran) and then measuring their levels in the serum after 6 hrs of digestion. Foxo4-null mice have markedly increased levels of both 4-kD and 40-kD FITC-dextran in their sera (Figure 4A). To test whether this leaky epithelial phenotype is related to epithelial cell death or the defect in the TJ barrier function, we first examined the apoptotic level of colonic epithelium of WT and Foxo4-KO mice, and observed no differences (Supplemental Figure S4). We next examined the expression level of TJ protein ZO-1, claudin-1, claudin-2, and occludin. Western blot of colonic mucosal lysates from Foxo4-null mice showed significant downregulation of ZO-1 and claudin-1 compared to WT controls (Figure 4B). No significant changes were observed for claudin-2 and occludin (data not shown).

Figure 4. Deletion of Foxo4 in vivo increases the intestinal epithelial permeability.

(A) Intestinal epithelial permeability was assessed with FITC-labeled dextran (4 kD and 40 kD) in vivo (n=10 ± SEM, *, p<0.05). (B) Left panel. Western blot of ZO-1 and claudin-1 from colonic mucosa of WT and Foxo4 KO mice. The intensities of the protein bands were quantified using Image J software (Right panel) (n=4 ± SEM, *, p<0.05). (C) Relative mRNA of Foxo4, ZO-1 and claudin-1 in caco-2 cells transfected with either non-specific control siRNA (NSC) or Foxo4 specific siRNAs (Foxo4-1 or Foxo4-2) (n=3 ± SEM *, p< 0.05). (D) Western blot of FoxO proteins in coca-2 cells transfected with Foxo4 siRNA and control siRNA.

It has been shown that cytokines inhibit expression of TJ proteins (14, 15). As TNFα and IFNγ are upregulated in colonic mucosa of Foxo4-null mice, we tested whether FoxO4 could regulate the expression of TJ proteins independently from inflammatory cytokines. We performed gene knock down experiments in the intestinal epithelial cell line caco-2 using Foxo4 specific siRNAs and measured the transcript levels of ZO-1 and claudin-1 in the knocked down cells. To rule out off-target effects, we used two independent Foxo4 specific siRNAs. Both mRNA and protein levels of Foxo4 were efficiently knocked down by both Foxo4 siRNAs compared to the control with a nonspecific siRNA (Figure 4, C and D). In these Foxo4 knocked down cells, both ZO-1 and claudin-1 transcripts were significantly downregulated (Figure 4C, lanes 4–9). We observed a similar effect of Foxo4 siRNA in another intestinal epithelial cell line, HT-29 (Supplemental Figure S5A). These results suggest that FoxO4 has a cytokine-independent regulatory function on the expression of TJ proteins.

We examined the TJ structures of six-week old mice by transmission electron microscopy. TJs in colonic epithelium of Foxo4-null mice appear to be intact and no visible breakage compared to those of WT mice (Supplemental Figure S5B), although they appear to be less organized. This is consistent with the fact that no spontaneous colitis was observed in Foxo4-null mice under physiological conditions. We speculate that the permeability defect observed in Foxo4-null mice is caused by changes in the expression within some of the TJ proteins and not by gross changes in structure. Such permeability defect may be sufficient to trigger and elevate the mucosal immune response but may not be sufficient to allow passage of larger harmful pathogens such as bacteria to cause colitis.

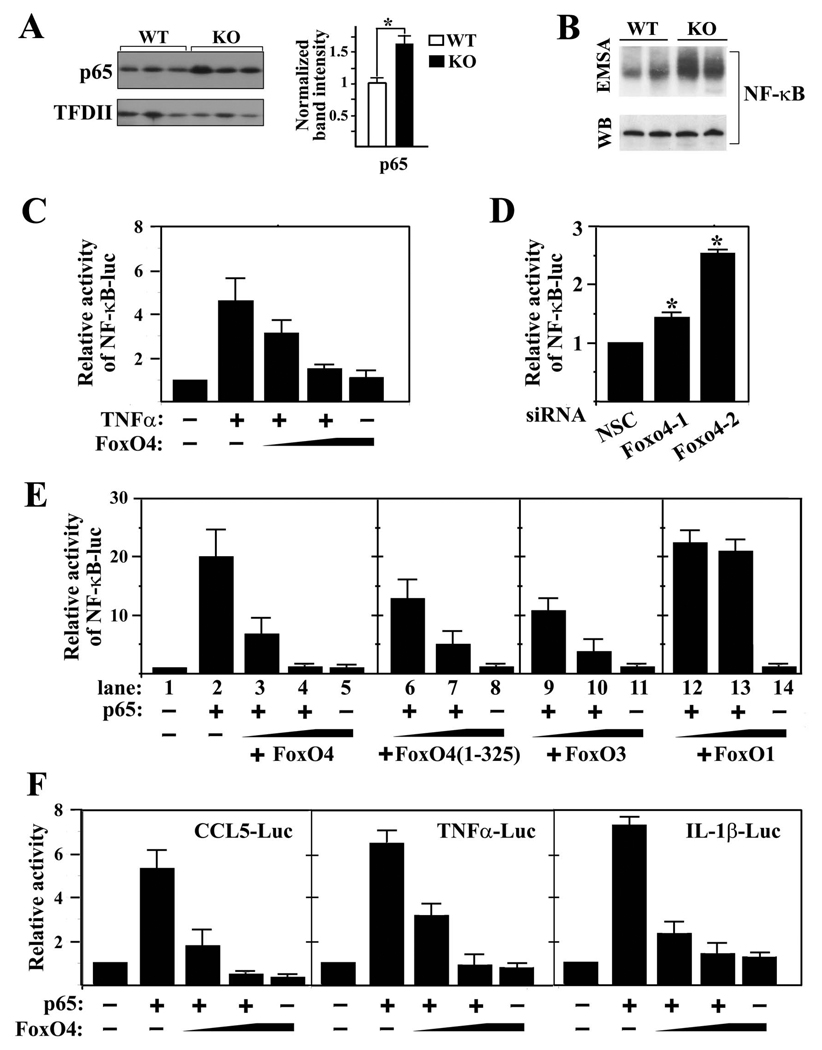

FoxO4 inhibits the transcriptional activity of NF-κB

As FoxO4 is a transcription factor and transcription of multiple cytokines is upregulated in colons of Foxo4-null mice, we hypothesized that FoxO4 may regulate cytokine expression through a common transcription factor, NF-κB, which was known to regulate mucosal cytokine expression and TJ proteins (5, 15, 16). To test this hypothesis, we examined the NF-κB activity in Foxo4-null epithelial cells by measuring its nuclear protein level. Western blot analysis indicated that nuclear NF-κB protein from Foxo4-null mice is significantly upregulated compared to that from the WT control (Figure 5A). The DNA binding activity of NF-κB in the colonic mucosa of Foxo4-null mice was also significantly increased relative to WT controls in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. FoxO4 inhibits the transcriptional activity of NF-κB.

(A) Western blot of nuclear NF-κB from colonic epithelial cells of WT and Foxo4-null mice. TFDII was used as loading control (n=3±SEM, *,p<0.05). (B) NF-κB DNA binding activities from colonic mucosa of WT and Foxo4-KO mice were measured using electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) with a κB oligonucleotide probe. Representative results from two WT and two Foxo4-KO mice are shown. Total p65 protein level was used as a loading control. (C) NF-κB-luc reporter activity from caco-2 cells transfected with a NF-κB-luc reporter and increasing amount of FoxO4 plasmid. The reporter was activated by endogenous NF-κB upon stimulation with TNFa (20 ng/ml) (n=3 ± SEM). (D) The basal activity of NF-κB in Foxo4 knocked down caco-2 cells was measured using NF-κB-luc reporter (n=3 ± SEM, *, p<0.05). (E) NF-κB-luc reporter activity from 293T cells transfected with a NF-κB-luc reporter and various constructs as indicated (n=3 ± SEM). (F) Luciferase reporter activities from 293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids (n=3 ± SEM).

We next examined the effects of either gain or loss of function of FoxO4 on NF-κB activation in caco-2 cells using NF-κB-luciferase as a reporter. NF-κB-luciferase reporter was transfected into caco-2 cells together with various amounts of FoxO4 plasmid. Endogenous NF-κB was activated by TNFα stimulation. FoxO4 inhibited TNFa activated endogenous NF-κB in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5C). In the gene knocked-down experiments, transfection of caco-2 cells with either of the two independent Foxo4 siRNAs resulted in a significant increase in the basal activity of NF-κB (Figure 5D). These data suggest that upregulation of NF-κB in vivo could at least partially be attributed to the loss of inhibition by FoxO4.

To understand the molecular mechanism of FoxO4 inhibition on NF-κB, we tested the effect of various deletion mutants of FoxO4 on the transcriptional activity of NF-κB p65 in 293T cells. FoxO4 inhibited p65-activated transcription in a dose dependent manner (Figure 5E, lanes 3 and 4). A C-terminal deletion mutant of FoxO4, FoxO4(1–325), had a similar dose-dependent inhibitory effect on the transcriptional activity of NF-κB as wild-type FoxO4 (Figure 5E, lanes 6 and 7). FoxO3, but not FoxO1, also inhibited NF-κB-activated transcription (Figure 5E, lanes 9 and 10, 12 and 13, respectively). A dose-dependent inhibition of FoxO4 on NF-κB-mediated transactivation of CCL5, TNFα, and IL-1β was observed as well (Figure 5F).

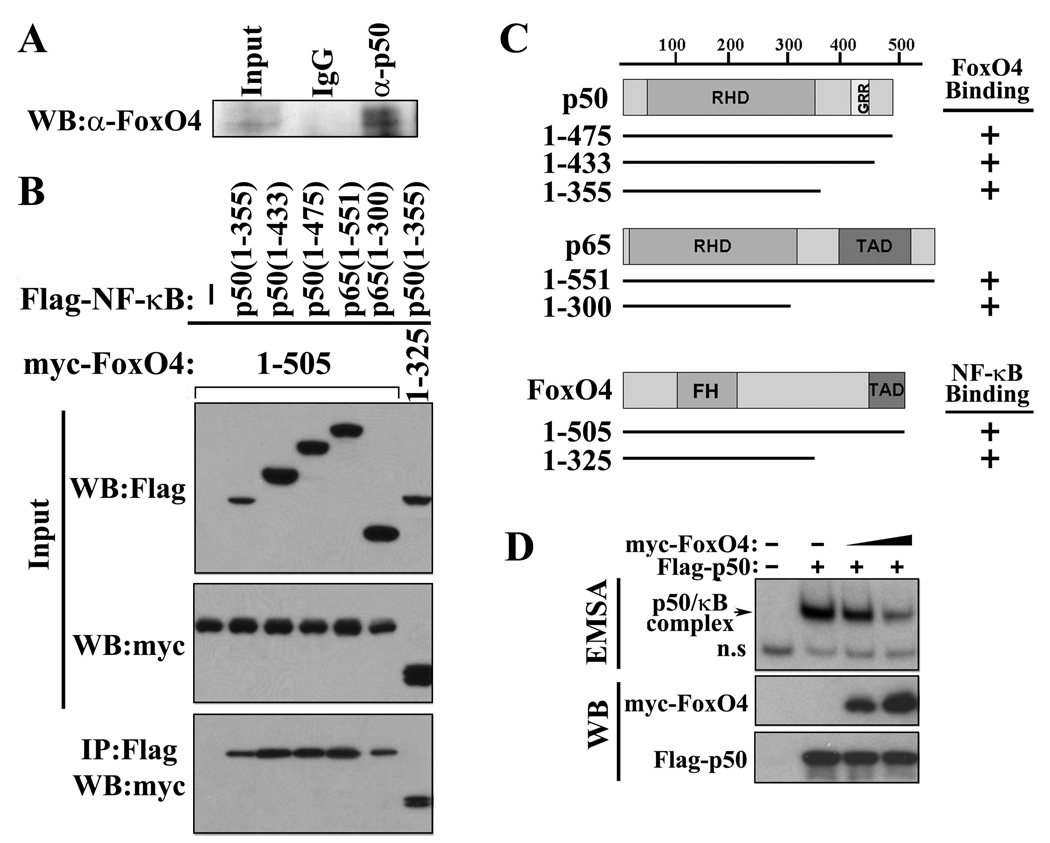

FoxO4 interacts with NF-κ B and inhibits its DNA binding activity

To understand the molecular mechanism by which FoxO4 regulates the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, we tested whether FoxO4 could physically interact with NF-κB by co-immunoprecipitation assays. Interaction between endogenous FoxO4 and NF-κB p50 was observed in colonic epithelial cells (Figure 6A). Using a series of deletion mutants of FoxO4 and NF-κBs, we have mapped the binding domain of FoxO4 on NF-κB to its Rel-homology domain (RHD) and the interactive domain of NF-κB on Foxo4 to its N-terminal region (residues 1–325) (Figure 6,B and C). As the RHD of NF-κB is involved in DNA binding, we hypothesized that FoxO4 may inhibit NF-κB activity by interfering with its DNA binding activity. Indeed, a lower amount of NF-κB was bound to κB DNA in a gel shift assay in the presence of ectopically expressed FoxO4 (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. FoxO4 interacts with NF-κB and inhibits its DNA binding activity.

(A)Endogenous NF-κB p50 and FoxO4 from mouse colonic epithelial cells were co-immunoprecipitated (IP) with control IgG and anti-p50 antibody. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to western blot (WB) analysis and probed with anti-FoxO4 antibody. (B) 293T cells were transfected with indicated expression plasmids. Cell lysates were used for IP with anti-Flag antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by WB with anti-myc antibody. Five percent of inputs are shown. TAD, transactivation domain. GRR, glycine rich region. (C) Schematic diagram of plasmids used in (B). (D) Protein extracts from 293T cells transfected without and with NF-κB Flag-50 and increasing amount of myc-FoxO4 were used for an EMSA (upper panel) and for western blot analysis with anti-Flag and anti-myc antibody (lower panels).

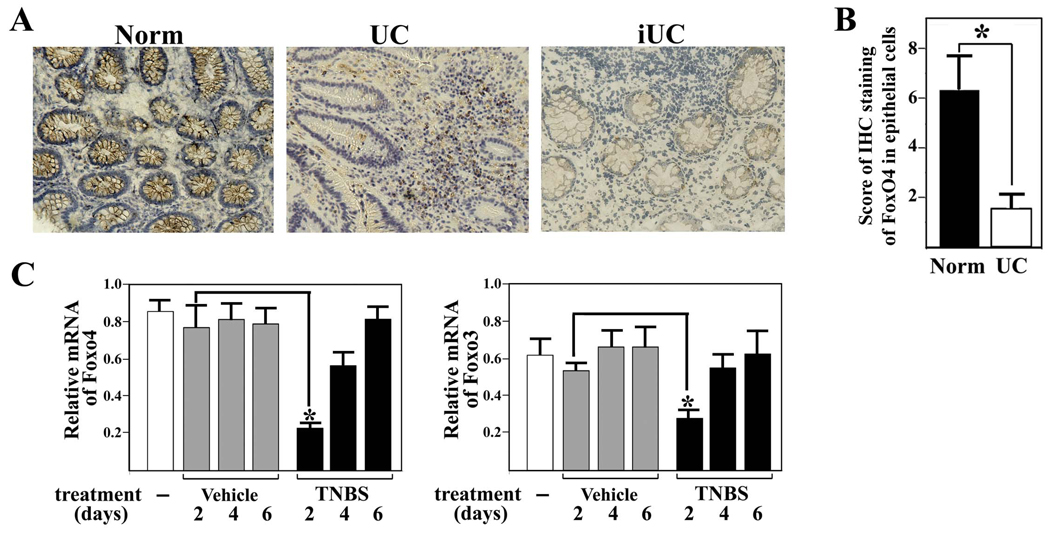

Expression of FoxO4 is downregulated in colonic epithelial cells of human patients with active UC

To examine the possible involvement of endogenous FoxO4 in human IBD, we performed immunohistochemistry of FoxO4 in colonic tissues of patients with UC. Our study with Foxo4-deficient mice suggests that FoxO4 expression should be decreased during inflammation, as NF-κB expression was upregulated in colonic epithelial cells of IBD patients (16, 17). Consistent with this prediction, FoxO4-immunostaining in epithelial cells of tissues with active disease was significantly downregulated compared to those in cells of control normal tissues (Figure 7, A and B). A weak positive FoxO4-staining reappeared in epithelial cells of inactive UC patients. A transit downregulation of both Foxo4 and Foxo3 transcripts was also observed in the colonic mucosa of mice after TNBS-treatment (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. Expression of FoxO4 is downregulated during inflammation.

(A) Representative micrographs of colonic mucosal biopsies from patients with active UC (middle panel), normal tissues (Norm, left panel), and inactive UC (iUC, right panel) stained with anti-FoxO4 antibody. (B) Immunohistochemistry of FoxO4 in epithelial cells was scored from colonic tissue samples of individual patients with active UC and normal controls (n=10, *, p<0.01). (C) WT mice were given a single dose of ethanol (vehicle) and TNBS intrarectally. Colonic mucosal mRNA of Foxo4 and Foxo3 following the treatment was measured by qRT-PCR (n=4, *, p<0.01).

Discussion

Mucosal immunity and epithelial permeability are two interconnected etiological factors in the pathogenesis of IBD. Increased intestinal permeability could allow luminal antigens to penetrate the intestinal tissue that activates and/or perpetuates the immune response. Abnormal immune reaction could overproduce inflammatory cytokines that regulate TJs and increase the epithelial permeability. In this study, we have identified a novel function of FoxO4 in regulation of mucosal immunity and epithelial permeability. Our results show that the mucosal immune reaction and intestinal epithelial permeability are both upregulated in Foxo4-null mice under physiological conditions, which could provide a mechanism for the exacerbated inflammatory response to TNBS-treatment. How does FoxO4 regulate mucosal immunity and epithelial permeability?

FoxO4 may regulate intestinal mucosal immunity by repressing inflammatory cytokine expression. Cytokines CCL5, CXCL9, TNFα, and IFNγ are upregulated in colons of Foxo4-null mice under physiological conditions. More importantly, part of the upregulated CCL5 is attributed to epithelial cells. CCL5 is an important chemoattractant cytokine for regulating movement of T cells in the intestine (18–20). Upregulation of epithelial derived CCL5 could result in an increased recruitment of T cells in the intestine and play an early role in the onset of IBD. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed increased number of CD4+ IELs in the Foxo4-null mice. We have also observed that Foxo4-deficient macrophages produce higher level of IL-6 in response to LPS than WT controls, suggesting that there might be an additional mechanism for the elevated colitis susceptibility in Foxo4-null animals that Foxo4-deficient colonic lymphocytes are more activated.

FoxO4 may regulate intestinal permeability through TJ proteins including occludins, claudins, and ZO proteins. Expression levels and distribution of these TJ proteins influence the epithelial permeability (5, 6, 15, 16). We have observed downregulation of ZO-1 and claudin-1 in both Foxo4-deficient epithelial cells in vivo and Foxo4-knocked down epithelial cells in vitro, which could provide a structural basis for the increased intestinal epithelial permeability in Foxo4-null mice.

The effects of FoxO4 on intestinal mucosal immunity and epithelial permeability are likely through NF-κB (16, 17, 20–22). Both loss and gain-of function of NF-κB have been shown to increase epithelial permeability through different mechanisms (15–16, 22). Nenci et al. showed that NF-κB-inactivated epithelial cells have increased permeability due to an increase in TNFα -mediated epithelial cell death (22). Upregulation of epithelial permeability in Foxo4-null mice is likely due to the downregulation of TJ protein levels as a result of increased NF-κB activity in the epithelial cells.

There are several mechanisms by which FoxO4 may inhibit NF-κB. FoxO4 may inhibit NF-κB by upregulating IκB expression indirectly through Foxj1 or compete with IκB for IκB kinase binding (9, 23). Alternatively, FoxO4 could inactivate NF-κB through direct physical interaction, which could prevent NF-κB from either entering the nucleus or binding to the DNA. No down-regulation of IκB protein level was observed in Foxo4-deficient epithelial cells compared to WT controls (data not shown), suggesting that inhibition of NF-κB by FoxO4 is likely IκB-independent. We found that FoxO4 indeed interacts with NF-κB both in vivo and in vitro. Binding of NF-κB to FoxO4 interferes with its nuclear translocation and its DNA binding activity. Together, our data favor the possibility that FoxO4 inhibits NF-κB through direct physical interaction.

In our TNBS-treated animals, we observed a transient down regulation of mucosal FoxO4 mRNA. Similar decreases of epithelial FoxO4 expression were also observed in UC patients. Although our mouse model of chemically induced colitis may not accurately reflect the immunological and histopathological aspects of IBD in humans, it is tempting to speculate nonetheless that FoxO4 may play an important role in the pathogenesis of human IBD.

In addition, FoxO4 may regulate the colonic mucosal immunity in a NF-κB-independent manner. FoxO4 is known to induce expression of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and catalase in response to oxidative stress signals to scavenge the reactive oxygen species (ROS) in vitro (8). It will be worth testing whether such an anti-oxidative stress function of FoxO4 plays a role in the elevated susceptibility of Foxo4-KO mice to colitis in vivo.

FoxO4 activity may be regulated at transcriptional level by inflammatory signals. We have identified several conserved cis- elements for transcription factors including interferon regulatory factor (IRF) and NF-κB in the promoter region of Foxo4 gene using ECR browser (www.dcode.org). We have found that NF-κB can activate Foxo4 transcription in a luciferase reporter assay whereas IRF1 inhibits it (WZ and ZPL, unpublished results). Although it remains to be determined, NF-κB could activate transcription of Foxo4 in vivo, providing a mechanism of negative feed-back loop for regulating NF-κB activity. In support of this hypothesis, we found that transcription of Foxo4 was returned to normal after transient downregulation in response to TNBS- treatment. It is noted that many of the proteins that inhibit NF-κB activity including IκB can also be transcriptionally activated by NF-κB (24).

In summary, our data support the following mechanistic model. Under physiological conditions, the transcriptional activity of NF-κB in the gut is tightly regulated by FoxO4 so that NF-κB is minimally activated to keep a low-grade chronic inflammation. Inflammatory signals activate NF-κB and in the mean time inactivate FoxO4 possibly through IRFs, releasing its inhibition of NF-κB to allow maximum activation to combat inflammation. Once the inflammation is resolved, FoxO4 expression returns to its normal level to keep NF-κB minimally activated. Although we favor the hypothesis that FoxO4 targets both intestinal epithelial permeability and mucosal cytokine expression in intestinal epithelial cells and lymphocytes, given the complexity of the cell types involved in mucosal immunity, studies with tissue-targeted deletion of Foxo4 will be needed to delineate the mechanisms of Foxo4 function in various cells and tissues.

Materials and methods

Mice, TNBS-treatment, and Histology

Six- to eight-week old littermates or age matched male WT and Foxo4-null mice were used as indicated in the experiment. Mice were fasted for 16 hrs before induction of colitis. Anesthesia was achieved by the intraperitoneal administration of freshly prepared Avertin (2%). A 100 ul enema of TNBS (250 mg, Sigma) in 50% ethanol was infused into the colonic lumen following published protocol (25). Animals were sacrificed at timed points and the colon was removed, weighted, measured, and used for subsequent analysis as indicated. All methods used in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the UT Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas.

The entire mouse colon was Swiss-rolled, formalin-fixed, and paraffin-embeded. Colon sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The colitis were analyzed and scored by a blinded pathologist according to the published graded histopathological changes (26).

RNA and cDNA preparation and microarray analysis

Mucosa samples were obtained from longitudinally cut large intestines of mice by gentle scraping with a blunt edged slide. RNAs and cDNAs were prepared from colonic mucosa or cells using Trizol and superscript III reagents following manufacture’s protocol (Invitrogen). SYBR Green-based qRT-PCR was used to examine relative levels of selected mRNAs. All data were normalized to an internal standard (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ΔΔCT method). Sequences for gene specific primer pairs are available upon request. For microarray analysis, cDNAs of colonic mucosal tissue from five mice per each treatment group (untreated, two days after ethanol or TNBS-treatment) were pooled. Microarrays were performed using Illumina bead array platform and the data are accessible in NCBI GEO database (GSE16033).

Isolation of epithelial cells and IELs, flow cytometry, and measurement of colonic epithelial permeability

The entire large intestine was cut open longitudinally and washed with PBS. The tissue was cut into < 5mm pieces and washed extensively in HBSS and used for subsequent isolation of epithelial cells and IELs following published protocols (27, 28). The IELs were labeled with anti-CD4 antibody (BD bioscience) and subjected to flow cytometry (BD Fascalibur system). CD3+ T cell contamination in the epithelial cell preparation was routinely confirmed to be less than 2% by flow cytometry. Colonic epithelial permeability was assessed in vivo in mice using FITC-labeled dextran (FD4 and FD40, Sigma) method as described (29).

Plasmids, cell culture, luciferase reporter assays, siRNA , and TUNEL assay

The mammalian expression vectors of FoxO4 and various deletion mutants were described previously (7). Human NF-κB p65 and p50 were made by subcloning PCR-amplified inserts into Flag-tagged pcDNA3.1. NF-κB-Luciferase reporter was obtained from Clonetech. CCL5-, TNFα, and IL-1β-luciferase reporters were constructed by subcloning PCR-amplified inserts corresponding to the promoter sequence from human genomic DNA into the pGL3-basic vector (Promega). Detailed information about the plasmids is available upon request.

293T and Caco-2 cells (ATCC) were maintained in standard DMEM plus supplements (Invitrogen). Cells were transfected with combination of plasmids indicated for each experiment using Fugene 6 (Roche). Cell extracts were assayed for luciferase expression using a luciferase assay kit (Promega). Relative promoter activities were expressed as luminescence relative units normalized for cotransfected β-galactosidase expression in the cells. siRNAs were transfected into caco-2 cells using oligofectimine reagent (Invitrogen). GFP siRNA and/or FITC-labeled non-silencing duplex siRNA were used as negative controls. Sequences of Foxo4 specific siRNA are available upon request. TUNEL assays were performed using a kit from Roche.

Immunoprecipitation, Western blotting, and EMSA

293T cells were transfected with a various plasmids as indicated. Twenty-four hrs after transfection, cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation following a previous described procedure (7), using antibody as indicated for the experiments. Western blot was performed according to standard protocols using either anti-Flag (Sigma) or anti-myc (Santa Cruz) antibody. Antibodies used for western blot analysis are ZO-1, claudin-1, and occluding (Invitrogen), p50, p65, and FoxO4 (AFX(N-19), 7) (Santa Cruz), FKHR( FoxO1) and FKHRL1(FoxO3) (Cell Signaling). EMSA was performed according to a procedure described previously (7). The probe containing a NF-κB binding site from TNFα promoter was prepared by end labeling with 32P-γ-ATP using polynucleotide kinase.

Tissue samples from patients and immunohistochemistry of FoxO4

Colorectal mucosal biopsy samples were obtained from 10 patients with UC and 3 patients with inactive UC who had undergone colonoscopy examination at Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Hangzhou, China. These patients were diagnosed by certified hospital gastroenterologists. Disease activity was assessed using Modified Mayo Clinic Score that consists of 4 criteria: stool frequency, rectal bleeding, colonoscopy findings, and assessment of patients’ function. Each diagnose is graded on a scale of 0 to 3. Total grade of 11–12 indicates severely active UC, 6–10 moderately active; 3–5 mildly active; and grade below 2 indicates remission. Among the thirteen patients, one has severely active UC, three have moderately active UC, six have mildly active UC, and three have inactive UC. The medication list includes Mesalazine alone, Mesalazine plus Prednisone, or Azathioprine plus Prednisone. Tissue samples from patients who have normal mucosa according to endoscopic and histological criteria were used as normal control. All tissue samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen-chilled isopentane. Frozen sections were used for routine H&E staining and immunohistochemistry. A pathologist confirmed all the histological diagnoses. The study was approved by Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital Ethics committee and conducted with the consent of all patients. Immunohistochemical staining of FoxO4 were evaluated according to a published procedure (30).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a SDG from the American Heart Association, Texas Advanced Research Program under grant number 010019-0070-2007, and RO1 HL085749 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to Z.-P. L. Q.C. was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China NO : R2080029.

RAD is an American Society Research Professor and Senior Scholar of the Ellison Medical Foundation and is supported by the Renee E. and Robert A. Belfer Institute for Innovative Cancer Science.

Grant support: scientist development grant from the American Heart Association, Texas Advanced Research Program-010019-0070-2007, RO1 HL085749 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China NO : R2080029

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Loftus EV., Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Nimmo ER, et al. The genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2820–2831. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elson CO, Cong Y, McCracken VJ, et al. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease reveal innate, adaptive, and regulatory mechanisms of host dialogue with the microbiota. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:260–276. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Incà R, Di Leo V, Corrao G, et al. Intestinal permeability test as a predictor of clinical course in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2956–2960. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma TY, Iwamoto GK, Hoa NT, et al. TNF-alpha-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability requires NF-κB activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G367–G376. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00173.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma TY, Anderson JM. Tight Junctions and Intestinal Barrier. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Academic Press; 2006. pp. 1559–1594. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu ZP, Wang Z, Yanagisawa H, et al. Phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells through interaction of Foxo4 and myocardin. Dev Cell. 2005;9:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgering BM. A brief introduction to FOXOlogy. Oncogene. 2008;27:2258–2262. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin L, Hron JD, Peng SL. Regulation of NF-kappaB, Th activation, and autoinflammation by the forkhead transcription factor Foxo3a. Immunity. 2004;21:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dengler HS, Baracho GV, Omori SA, et al. Distinct functions for the transcription factor Foxo1 at various stages of B cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1388–1398. doi: 10.1038/ni.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, et al. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 2007;128:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tothova Z, Kollipara R, Huntly BJ, et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 2007;128:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitman RS, Blumberg RS. First line of defense: the role of the intestinal epithelium as an active component of the mucosal immune system. J Gastroenterol. 2007;35:805–814. doi: 10.1007/s005350070017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang F, Graham WV, Wang Y, et al. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergize to induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by up-regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:409–419. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62264-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye D, Ma I, Ma TY. Molecular mechanism of tumor necrosis factor-alpha modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G496–G504. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00318.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atreya I, Atreya R, Neurath MF. NF-κB in inflammatory bowel disease. J Intern Med. 2008;263:591–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andresen L, Jørgensen VL, Perner A, et al. Activation of nuclear factor kappaB in colonic mucosa from patients with collagenous and ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54:503–509. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong W, Kolls JK, Chen H, et al. Chemokines orchestrate leukocyte trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Biosci. 2008;13:1654–1664. doi: 10.2741/2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strober W, Fuss IJ, Blumberg RS. The immunology of mucosal models of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:495–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montufar-Solis D, Garza T, Klein JR. T-cell activation in the intestinal mucosa. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:189–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gadjeva M, Wang Y, Horwitz BH. NF-κB p50 and p65 subunits control intestinal homeostasis. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2509–2517. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nenci A, Becker C, Wullaert A, et al. Epithelial NEMO links innate immunity to chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2007;446:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature05698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu MC, Hung MC. Role of IkappaB kinase in tumorigenesis. Future Oncol. 2005;1:67–78. doi: 10.1517/14796694.1.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun SC, Ganchi PA, Ballard DW, et al. NF-kappa B controls expression of inhibitor I kappa B alpha: evidence for an inducible autoregulatory pathway. Science. 2003;259:1912–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.8096091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirtz S, Neufert C, Weigmann B, et al. Chemically induced mouse models of intestinal inflammation. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:541–546. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ten HoveT, Corbaz A, Amitai H, et al. Blockade of endogenous IL-18 ameliorates TNBS-induced colitis by decreasing local TNF-alpha production in mice. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1372–1379. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denning TL, Campbell NA, Song F, et al. Expression of IL-10 receptors on epithelial cells from the murine small and large intestine. International Immunology. 2000;12:133–139. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weigmann B, Tubbe I, Seidel D, et al. Isolation and subsequent analysis of murine lamina propria mononuclear cells from colonic tissue. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:2307–2311. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vijay-Kumar M, Sanders CJ, Taylor RT, et al. Deletion of TLR5 results in spontaneous colitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3909–3921. doi: 10.1172/JCI33084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagai MA, Fregnani JH, Netto NM, et al. Down-regulation of PHLDA1 gene expression is associated with breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106:49–56. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.