Abstract

Nitrogen-fixing rhizobial bacteria and leguminous plants have evolved complex signal exchange mechanisms that allow a specific bacterial species to induce its host plant to form invasion structures through which the bacteria can enter the plant root. Once the bacteria have been endocytosed within a host-membrane-bound compartment by root cells, the bacteria differentiate into a new form that can convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. Bacterial differentiation and nitrogen fixation are dependent on the microaerobic environment and other support factors provided by the plant. In return, the plant receives nitrogen from the bacteria, which allows it to grow in the absence of an external nitrogen source. Here, we review recent discoveries about the mutual recognition process that allows the model rhizobial symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti to invade and differentiate inside its host plant alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and the model host plant barrel medic (Medicago truncatula).

The recent completion of the Sinorhizobium meliloti genome sequence, and the progress towards the completion of the Medicago truncatula genome sequence, have led to a surge in the molecular characterization of the determinants that are involved in the development of the symbiosis between rhizobial bacteria and leguminous plants. Aromatic compounds from legumes called flavonoids first signal the rhizobial bacteria to produce lipochitooligosaccharide compounds called Nod factors1. Nod factors that are secreted by the bacteria activate multiple responses in the host plant that prepare the plant to receive the invading bacteria. Nod factors and symbiotic exopolysaccharides induce the plant to form infection threads, which are thin tubules filled with bacteria that penetrate into the plant cortical tissue and deliver the bacteria to their target cells. Plant cells in the inner cortex internalize the invading bacteria in host-membrane-bound compartments that mature into structures known as symbiosomes. The internalized bacteria then develop into bacteroids, a differentiated form that is capable of nitrogen fixation. During invasion and symbiosis, rhizobial bacteria can evade the host plant innate immune response. In this Review, we summarize and integrate the advances that have been made towards understanding the invasion of plant tissues by rhizobia, and the differentiation of the specialized bacterial and plant structures that facilitate nutrient exchange.

Invasion of plant roots

Although plant roots are exposed to various micro-organisms in the soil, their cell walls form a strong protective barrier against most harmful species. The early steps in the invasion of barrel medic (M. truncatula) and alfalfa (Medicago sativa) roots by S. meliloti are characterized by the reciprocal exchange of signals that allow the bacteria to use the plant root hair cells as a means of entry.

Initial signal exchange

Flavonoid compounds (2-phenyl-1,4-benzopyrone derivatives) produced by leguminous plants are the first signals to be exchanged by host–rhizobial symbiont pairs1 (FIG. 1). Flavonoids bind bacterial NodD proteins, which are members of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators, and activate these proteins to induce the transcription of rhizobial genes1,2. For example, the M. sativa-derived flavonoid luteolin stimulates binding of an active form of NodD1 to an S. meliloti ‘nod-box’ promoter, which activates transcription of the downstream nod genes3. S. meliloti has two other NodD proteins — NodD2, which is activated by as-yet-unpurified plant compounds, and NodD3, which does not require plant-derived compounds to activate gene expression from nod box promoters1. The expression of NodD3 itself is controlled by a complex regulatory circuit2. Any of these NodD proteins can provide S. meliloti with the ability to nodulate M. sativa1. Flavonoids from non-host plants can inhibit the transcription of S. meliloti nod genes3.

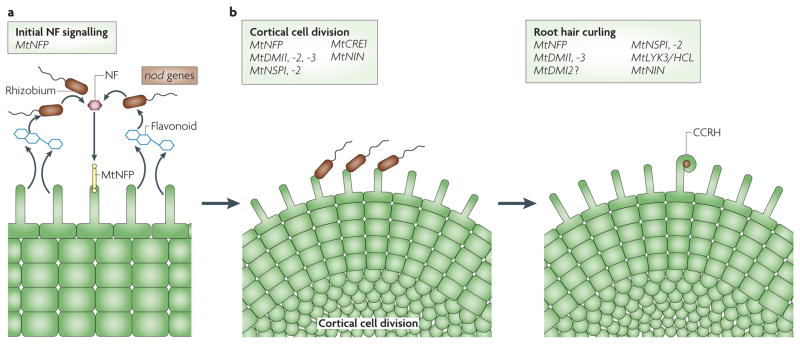

Figure 1. The initial signalling dialogue between Sinorhizobium meliloti and Medicago truncatula.

a | The induction of rhizobial nod genes requires plant flavonoids1,4. The nod gene products produce Nod factor (NF), which is initially perceived by the M. truncatula MtNFP receptor1,4,17. b | Root hair curling and cortical cell divisions require many M. truncatula gene products4,13: MtNFP17; MtDMI1 (REF. 20); MtDMI2 (REF. 25); MtDMI3 (REFS 22,23); MtNSP1 (REF. 27); MtNSP2 (REF. 26); MtCRE1 (REFS 58–60); and MtNIN58,61. MtLYK3/HCL is required for colonized curled root hair (CCRH) formation, but not for the induction of cortical cell divisions19 (P. Smit and T. Bisseling, unpublished data). The required rhizobial genes are boxed in brown and the required plant genes are boxed in light green.

Among the rhizobial genes induced by flavonoid-activated NodD proteins are several nod genes encoding enzymes that are required for the production of lipochitooligosaccharide Nod factors4. Bacterially produced Nod factors induce multiple responses required for nodulation of appropriate host plants, and are the best characterized of the signals that are exchanged between plant hosts and rhizobial symbionts1. Nod factors consist of a backbone of β-1,4-linked N-acetyl-D-glucosamine residues, which can differ in number not only between bacterial species but also within the repertoire of a single species1. Nod factors are N-acylated at the non-reducing terminal residue with acyl chains that can also vary between rhizobial species1. The genes of the nodABC operon encode the proteins that are required to make the core Nod factor structure1. The products of other nod genes (and noe and nol genes) make modifications to Nod factors that impart host specificity, including the addition of fucosyl, sulphuryl, acetyl, methyl, carbamoyl and ara-binosyl residues, as well as introducing differences to the acyl chain1,4. Many rhizobial species produce more than one type of Nod factor, but it is not yet possible to predict the range of possible host plants from the Nod factor structure1. See REFS 1,4–7 for in-depth reviews of Nod factor production by bacteria, and perception and signalling by plants.

Nod factors initiate multiple responses that are essential for bacterial invasion of the plant host4. One of the earliest plant responses to the correct Nod factor structure is an increase in the intracellular levels of calcium in root hairs, followed by strong calcium oscillations (spiking)4 and alterations to the root hair cytoskeleton8–11. These responses are followed by curling of the root hairs, which traps rhizobial bacteria within what is known as a tight colonized curled root hair (CCRH)12,13 (FIG. 1). Simultaneously, Nod factor stimulates root cortex cells to reinitiate mitosis, a process that is dependent on the inhibition of auxin transport by rhizobia and plant flavonoids8,14–16. These cells will form the nodule primordium, and give rise to the cells that will receive the invading bacteria14.

Multiple extracellular-domain-containing receptors are required for a complete plant response to Nod factor6 (FIG 2) and in the absence of a functional MtNFP (M. truncatula Nod factor perception) gene, M. truncatula cannot respond17. MtNFP is a member of the LysM family of receptors, and is required for root hair curling and the induction of a subset of transcriptional changes in response to Nod factor17,18. Recently, RNA interference (RNAi) partial depletion experiments demonstrated an additional role for MtNFP during a later step in bacterial penetration of the root hair18 (infection thread formation; see below). Another LysM family receptor, encoded by MtLYK3/HCL, is known to be required for CCRH formation and fine-tuning of the plant responses to Nod factor during infection thread formation (P. Smit and T. Bisseling, unpublished data)19.

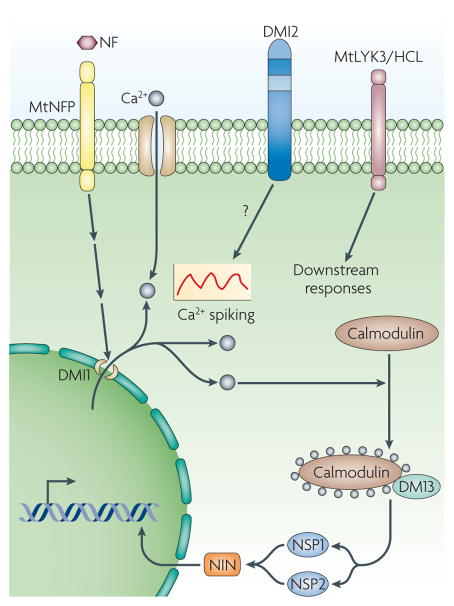

Figure 2. Downstream components of the Nod factor signal transduction system.

A complete response of Medicago truncatula to Nod factor (NF) from Sinorhizobium meliloti requires multiple extracellular-domain-containing cell-surface receptors, including the LysM family receptors MtNFP and MtLYK3/HCL. DMI2 encodes a leucine-rich-repeat receptor kinase that is localized to the membrane and is required for tight root hair curling around the bacteria. Downstream of NF, DMI1 encodes a ligand-gated ion channel that localizes to the nuclear membrane. DMI3 encodes a Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase that is required for the induction of cell division in the root cortex and for the transcriptional changes required for the establishment of the symbiosis. Two GRAS family transcriptional regulators, nodulation signalling pathway 1 (NSP1) and NSP2, are also required for Nod-factor-induced transcriptional changes. The response to NF also involves Ca2+ spiking.

Many downstream components of the Nod factor signal transduction system in leguminous plants have recently been identified4–7 (FIG. 2). DMI1 (does not make infections 1) encodes a ligand-gated ion channel that localizes to the nuclear membrane, and null mutations in DMI1 eliminate the calcium spiking response to Nod factor20,21. DMI3 encodes a Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CCaMk) that is necessary for the induction of cell division in the root cortex and for the transcriptional changes that are required for the establishment of the symbiosis22,23. Expression of a constitutively active allele of DMI3 induces these cell divisions and transcriptional changes, but does not induce root hair curling nor promote entry of bacteria, suggesting that these responses require other intermediates24. DMI2 encodes a leucine-rich-repeat receptor kinase that is required for tight root hair curling around the bacteria25. Two GRAS family transcriptional regulators, nodulation signalling pathway 1 (NSP1) and NSP2, are also required for Nod-factor-induced transcriptional changes26,27. Additionally, calcium spiking and transcript induction are dependent on phospholipid signalling pathways28. Transcriptional changes induced early in the nodulation programme, which are mainly due to the actions of Nod factor, have been characterized in several recent studies, and purified Nod factor can induce many of these signalling events in the absence of bacteria2,8. However, although Nod factor is necessary for nodule formation and S. meliloti invasion, it is not the only bacterially produced effector that is required for these symbionts to enter plant tissues and colonize plant cells.

Infection thread development

In all but the most primitive rhizobial–host symbioses, the bacteria must be internalized by plant cells in the root cortex before they can begin to fix nitrogen1. The bacteria penetrate these deeper plant tissues through the production of infection threads (FIG. 3). To form these structures, the bacteria must first become trapped at the root hair tip in a CCRH. Several S. meliloti mutants have been isolated that are inefficient in colonizing root hairs. Mutants that are unable to produce cyclic β-glucans cannot attach to root hairs effectively, a defect that might be due to a disrupted interaction with the host cell surface29,30. A constitutively active mutant of the transcriptional regulator exoS and a null mutant of the transcriptional regulator exoR are both less efficient than wild-type bacteria at colonizing root hairs31. Both of these mutants overproduce succinoglycan, but this does not appear to be the cause of their symbiotic defect, which could be caused by the lack of flagella or other currently unidentified factors31–33.

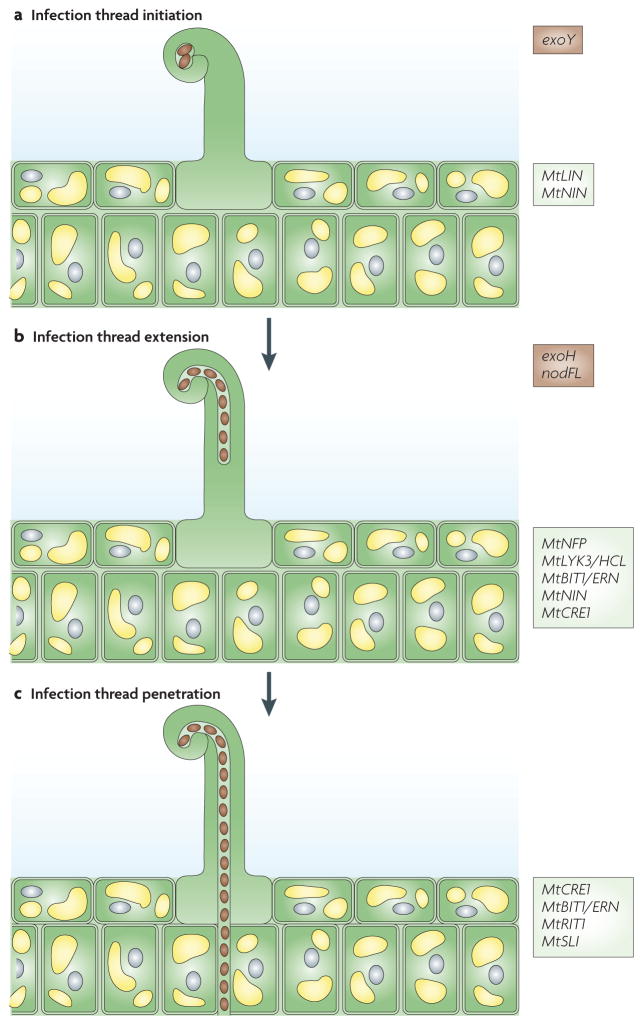

Figure 3. Root hair invasion by Sinorhizobium meliloti.

a | S. meliloti exoY36,39 and Medicago trunculata MtLIN43 and MtNIN61 are required for infection thread initiation. b | S. meliloti exoH39 and M. trunculata MtNFP18, MtLYK3/HCL19 (P. Smit and T. Bisseling, unpublished data), MtBIT1/ERN44, MtNIN61 and MtCRE1 (REFS 58–60) are required for infection threads to extend to the base of the root hair cell. c | MtCRE1 (REFS 58–60), MtBIT1/ERN44, MtRIT1 (REF. 62) and MtSLI64 are required for infection thread penetration into the underlying cell layers. The required rhizobial genes are boxed in brown and the required plant genes are boxed in light green.

Bacteria that have become trapped in a CCRH at the root hair tip, and can produce both Nod factor and a symbiotically active exopolysaccharide, induce the progressive ingrowth of the root hair cell membrane, resulting in bacterial invasion of interior plant tissue13. Efficient invasion occurs even if Nod factor and exopolysaccharide are supplied by separate S. meliloti strains that are co-inoculated and trapped together in the same CCRH34. The tip of the developing infection thread is a site of new membrane synthesis, and is proposed to involve inversion of the tip growth that is normally exhibited by the root hair and to be the result of reorganization of cellular polarity13. Microscopic analysis of fluorescently tagged bacteria within infection threads indicates that only the bacteria at the tip of the ingrowing infection thread are actively dividing35. Invasion appears to progress by continued bacterial proliferation at the tip and sustained induction of infection thread membrane synthesis.

S. meliloti produces the exopolysaccharides succinoglycan (also known as exopolysaccharide I, EPSI) and galactoglucan (EPSII), which facilitate infection thread formation36,37. Succinoglycan is a polymer of an octasaccharide repeating unit modified with acetyl, succinyl and pyruvyl substituents38 (BOX 1), is more efficient than galactoglucan in mediating infection thread formation on M. sativa and is the only exopolysaccharide produced by S. meliloti that can mediate the formation of infection threads on M. truncatula36,37. An S. meliloti exoY mutant, which cannot produce any succinoglycan, can form CCRHs but initiates almost no infection threads — these mutants remain trapped in a microcolony at the tip of the root hair39 (FIGS 3,4; TABLE 1).

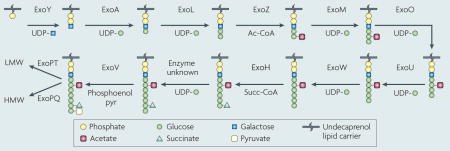

Box 1. Sinorhizobium meliloti succinoglycan biosynthesis.

Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 1021 requires the exopolysaccharide succinoglycan to establish a functional symbiosis with Medicago truncatula and Medicago sativa36,143. Bacterial mutants that are defective in succinoglycan production cannot initiate infection thread formation and yield nodules that are devoid of bacteria or bacteroids36,143. Succinoglycan is a polymer of an octasaccharide repeating unit composed of one galactose and seven glucose residues with acetyl, succinyl and pyruvyl modifications38,144 (see figure). Succinoglycan is produced in a high molecular weight (HMW) form, as a polymer containing hundreds of the octasaccharide repeating unit, and a low molecular weight (LMW) form that is composed of monomers, dimers and trimers of the repeating unit145. Application of the purified trimer fraction can partially rescue infection thread formation of a succinoglycan-deficient mutant. However, the variability of invasion under these conditions suggests that succinoglycan must be applied within the colonized curled root hair to function effectively145.

Many gene products are required for succinoglycan biosynthesis. ExoC, ExoB and ExoN are involved in the biosynthesis of the precursors UDP-galactose and UDP-glucose146,147. ExoY initiates the synthesis of the repeating unit, by transferring the galactosyl residue to the lipid carrier on the cytoplasmic side of the inner membrane148, and sugar transferases encoded by exoA, exoL, exoM, exoO, exoU and exoW subsequently elongate the octasaccharide backbone148. ExoZ, ExoH and ExoV transfer succinyl (Succ), acetyl (Ac) and pyruvyl (pyr) groups, respectively, to the growing backbone149,150. The mature repeating unit (linked to the lipid carrier) is flipped to the periplasmic side of the inner membrane, and then transferred to the growing polymer of succinoglycan by ExoP, ExoQ and ExoT148,149,151. The high molecular weight fraction of this polymer can be further processed by two extracellular endo-glycanases, ExoK and ExsH, to the low molecular weight form of succinoglycan40. UDP, uridine diphosphate.

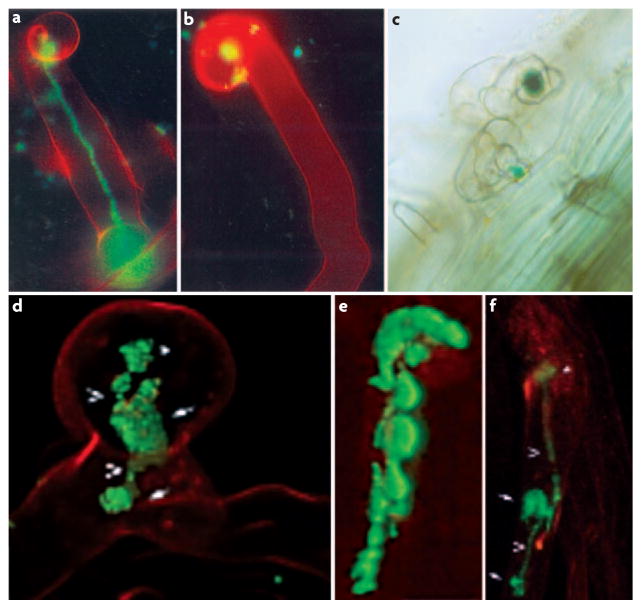

Figure 4. Infection thread failure can be caused by plant or bacterial defects.

Infection thread formation during invasion of Medicago truncatula or Medicago sativa by Sinorhizobium meliloti. a | An M. sativa root hair cell infected by S. meliloti wild-type bacteria, with a fully extended infection thread36. b | An M. sativa root hair arrested at the colonized curled root hair (CCRH) stage during infection by an S. meliloti exoY mutant36. c | A M. truncatula lin mutant arrested at the CCRH stage during infection by wild-type S. meliloti43. d | An arrested CCRH, formed during infection of M. truncatula with an S. meliloti nodF nodL mutant19. e | An aberrant, aborted infection thread formed by wild-type S. meliloti on M. truncatula partially depleted of MtNFP mRNA by RNA interference (RNAi)18. f | An aberrant infection thread formed by an S. meliloti nodF nodE mutant on M. truncatula partially depleted for MtLYK3 by RNAi19. Parts a and b reprinted with permission from REF. 36 © (2000) The American Society for Microbiology. Part c and e reprinted with permission from REF. 43 © (2004) American Society of Plant Biologists. Parts d and f reprinted with permission from REF. 19 © (2003) American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Table 1.

Bacterial and plant genes that are involved in infection thread development

| Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 genotype | Medicago truncatula genotype | Infection thread phenotype | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| exoY mutant: succinoglycan-deficient39 | Wild type | None initiated | Succinoglycan is necessary for infection thread initiation |

| Wild type | Mtlin mutant43 | Very few initiated; remainder aborted | Implies LIN is a possible plant product required for infection thread formation |

| exoH mutant: succinoglycan lacks succinyl modification, and consequently is mostly in HMW form39,40 | Wild type | Few initiated; remainder aberrant or aborted | Implies succinoglycan structural features are important for infection thread extension |

| NodFL double mutant: Nod factor lacks the acetyl substituent and carries an altered acyl chain19,42 | Wild type | Few initiated; remainder aberrant or aborted | Correct Nod factor structure is needed for infection thread formation as well as other responses |

| Wild type | RNAi knockdown of Nod factor receptor MtNFP18 | Aberrant | Implies a higher threshold of Nod factor perception or transduction is needed for infection thread formation than for other Nod factor responses |

| NodFE double mutant: Nod factor carries an altered acyl chain19 | RNAi knockdown of secondary Nod factor receptor MtLYK3/HCL19 | Aberrant | Suggests that secondary Nod factor receptor and Nod factor structural features interact to facilitate infection thread formation |

| Wild type | Mutant of putative transcription factor MtBIT1/ERN44 | Aberrant or aborted | Implies the function of putative transcription factor ERN is required for infection thread extension |

| Wild type | Mutant of MtNIN61 | Very few initiated; remainder aborted | Suggests reinitiation of cell division in the plant cortex is necessary for initiation and maintenance of infection threads. |

| Wild type | RNAi knockdown of putative cytokinin receptor MtCRE1 (REF. 58) | Aborted | Suggests re-initiation of cell division in the plant cortex is necessary for initiation and maintenance of infection threads |

| Wild type | Mutants of MtRIT1 (REF. 62) or MtSLI64 | Extended to base of root hair cell; aborted in underlying cell layers | Implies RIT1 and SLI are possible plant products required for infection thread penetration |

HMW, high molecular weight; RNAi, RNA interference.

An S. meliloti exoH mutant produces succinoglycan that lacks the succinyl substituent, and this mutant forms abortive, aberrant infection threads39 (TABLE 1). Unlike the normal condition, aberrant infection threads are bulbous and winding, as if the bacteria have continued to proliferate even though the tip of the infection thread has halted its inward progression36,39. In contrast to exoY-mutant-containing CCRHs, 70% of exoH-mutant-containing CCRHs initiate infection threads, but they all abort before reaching the base of the root hair39. Interestingly, the succinoglycan polymer produced by an exoH mutant is mostly in the high molecular weight form because the lack of the succinyl substituent renders it refractory to cleavage by extracellular glycanases40. It is not clear whether infection thread extension is dependent on the presence of the succinyl substituent of succinoglycan or on the production of low molecular weight (trimer, dimer and monomer) forms of succinoglycan. If succinoglycan has a role in signalling to the plant, perhaps the low molecular weight forms can interact more readily with the plant cell membrane, whereas the high molecular weight forms, which can be composed of polymers of hundreds of monomers, are sterically hindered by the plant cell wall. In a different host–symbiont pair, involving vetch (Vicia sativa) and Rhizobium leguminosarum, the structure of the bacterial exopolysaccharide appears to be less critical for infection thread extension41.

As mentioned earlier, in addition to succinoglycan, Nod factor is required for active and ongoing infection thread formation. Aberrant, abortive infection threads are formed when Nod factor is supplied in a structurally incomplete form, or if Nod factor perception is disrupted18,19,42. An S. meliloti nodF nodL double mutant that produces Nod factor that lacks the acetyl substituent and has an altered acyl chain cannot effectively invade plant cells, and induces approximately 20% of colonized root hairs to form infection threads19,42. Those infection threads that are formed are aberrant and ‘sac-like’, and abort before reaching the base of the root hair cell19 (FIG. 4 and TABLE 1). This is similar to the invasion phenotype of the exoH mutant described above39.

In relation to the host plant, mutant isolation and RNA interference have been used to identify genes encoding proteins that are involved in infection thread formation. The M. truncatula lin mutant, when inoculated with wild-type S. meliloti, has an abortive infection thread phenotype that is similar to that of a wild-type plant inoculated with an S. meliloti exoY mutant39,43 (TABLE 1). In both of these cases, infection arrests at the CCRH stage (FIG. 4). A deletion mutant of MtBIT1/ERN, which encodes a putative transcription factor involved in relay of the Nod factor signal, forms normal CCRHs but aberrant infection threads that cannot extend into deeper plant tissues44. RNAi knockdown has been used to assess the role of Nod factor receptors in infection thread formation. M. truncatula plants that are partially depleted by RNAi for the primary Nod factor receptor MtNFP, although capable of root hair curling and initiation of cortical cell divisions, form aberrant infection threads18 (FIG. 4 and TABLE 1). RNAi depletion of the secondary Nod factor receptor MtLYK3/HCL (also known as the entry receptor) does not cause wild-type S. meliloti to form aberrant infection threads; however, it does cause an S. meliloti nodFE mutant (which produces Nod factor with a modified acyl chain) to form defective infection threads19 (FIG. 4 and TABLE 1). These results indicate that the Nod factor signal requirement for infection thread formation is more stringent and perhaps of greater amplitude than that required for CCRH formation and the initiation of cortical cell divisions.

Other than the genetic and biochemical demonstrations of the requirement for succinoglycan and Nod factor, little is know about the way in which these factors mediate the extensive cytoskeletal remodelling that occurs during infection thread formation, or how the cytoskeleton might be involved in directing vesicular traffic to this site of new membrane synthesis. The cytoskeletal changes that occur during tip growth of polarized root hairs45 and the early effects of Nod factor on the root hair cytoskeleton that lead to root hair deformation have been subject to detailed analysis13,46,47. However, the cytoskeletal reorganizations involved in infection thread formation have not yet been thoroughly dissected. Inward movement of the root hair cell nucleus, in advance of the ingrowing infection thread, has been observed8. In these cells, a network of microtubules connects the nucleus to the tip of the infection thread and surrounds the infection thread itself 8. As the infection thread develops, the inside of this tubule is topologically outside the root hair cell and possesses a plant cell wall48. Interactions between plant cell-wall material and other components of the infection thread matrix might play an important part in infection thread growth48. Plant cell wall remodelling during root hair colonization and infection thread formation is another process that is not well understood, but is proposed to involve plant proteins that are exported to the cell wall and the infection thread matrix48. Plant glycoproteins that are associated with the infection thread matrix become crosslinked, probably by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in the infection thread49–51. One hypothesis is that solidification of the infection thread matrix, as a result of this crosslinking, generates a mechanical force that helps the ingrowth of the infection thread to proceed48. The production of ROS by plants is often part of a defence response against invading pathogens and it can also serve as an activating signal for other plant defences (see below)52. One intriguing possibility is that the facilitation of infection thread progression by ROS is one way that rhizobial bacteria have adapted a plant defence response for their own benefit.

The correct balance of ROS in the infection thread might be necessary for infection thread progression, and an excess of ROS could be detrimental to the rhizobia within the infection thread. However, the level of stress experienced by bacteria in the infection thread due to ROS is unknown. Single mutants in any of the three S. meliloti catalases, one of the two superoxide dismutases (sodB) or in the global regulator of H2O2 protection, oxyR, are sensitive to ROS, but are not defective in symbiosis53–56. However, double mutants in the genes encoding catalase B and catalase C (katB/katC) or catalase A and catalase C (katA/katC) are compromised in their ability to invade the host plant53,54. Mutants in a second superoxide dismutase, sodC, a predicted sodM (Smc00911) or a secreted chloroperoxidase (Smc01944) have not yet been analysed57. Further work is therefore required to elucidate how ROS, plant proteins and cell-wall materials interact with exopolysaccharides or other products that are secreted by the bacteria to influence development of the infection thread.

Targeting infection threads

Once an infection thread has penetrated to the base of a root hair cell the bacteria must induce new rounds of infection thread formation in each successive cell layer. Two important questions are: how is infection thread growth targeted to the cortical tissue layer; and, following the penetration of the cortex by an infection thread, what molecular processes mediate endocytosis of bacteria by plant cells into host-membrane-bound compartments?

The plant hormone cytokinin and the Nod-factor-dependent reinitiation of the cell cycle are involved in directing infection threads to the plant cortex. RNAi-mediated depletion of the M. truncatula putative cytokinin receptor/histidine kinase MtCRE1 results in a block in the reinitiation of cell division in the root cortical cells and the abortion of infection threads58 (TABLE 1). A mutation in the Lotus japonicus orthologue of MtCRE1, LHK1 (BOX 2), causes infection threads to arrest or loop and wander in the plant epidermal tissue instead of penetrating straight into the deeper cell layers59. It appears that this cytokinin receptor has an important role in initiating cortical cell division, as a constitutively active mutant of L. japonicus LHK1 induces spontaneous initiation of cell division in the absence of infecting bacteria60. The induction of the putative transmembrane-domain-containing transcription factor MtNIN is dependent on MtCRE158. Mtnin mutants are particularly interesting because they have early signalling responses to Nod factor but are impaired in both induction of cortical cell division and infection thread development, suggesting that MtNIN might be involved in integrating these processes61 (TABLE 1). This is consistent with a model in which cortical cell divisions provide a signal for the initiation and maintenance of infection threads. Mtrit1 and Mtsli mutants are also defective in penetration of the infection thread into deeper cortical tissue, but the genes carrying these mutations have not yet been cloned62–64 (TABLE 1).

Box 2. Mesorhizobium loti and Lotus japonicus: model system for determinate nodules.

Rhizobium–legume symbiosis research has progressed quickly using the Mesorhizobium loti–Lotus japonicus model system, in addition to the Sinorhizobium meliloti–Medicago truncatula model system as discussed in the text. The Nod factor signalling pathway in these two models is similar and has many conserved components (see table). However, what makes comparative study of both these systems most interesting is that they form different types of nodules, in which the nodule structure and the differentiation programme imposed on the symbiotic bacteria are different. M. truncatula and Medicago sativa are examples of indeterminate legumes, which form nodules that possess a persistent meristem, whereas L. japonicus forms determinate nodules, which lack a persistent meristem and in which all cells in the interior of the nodule proliferate, differentiate and senesce synchronously65. Engineering of bacterial symbionts that nodulate the opposite type of host has determined that the plant controls the degree of differentiation and the ultimate fate of the bacteria65. Differentiated bacterial symbionts isolated from L. japonicus nodules have not undergone genomic endoreduplication and can resume growth65. However, fully differentiated bacteroids isolated from M. truncatula are unable to resume growth, perhaps because of effects of extensive genomic endoreduplication on the bacterial cell cycle65.

| Medicago trunculata protein | Lotus japonicus orthologue | Function |

| MtNFP | LjNFR5 (REF. 4) | Nod factor receptor |

| Unknown | LjNFR1 (REF. 4) | Nod factor receptor |

| MtDMI2 (REF. 25) | LjSymRK4 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase |

| MtDMI1 (REFS 20,21) | LjCASTOR/POLLUX152 | Ion channel |

| Unknown | LjNUP133, LjNUP85 (REFS 153,154) | Nucleoporin |

| MtDMI3 (REFS 22,23) | LjSYM15/snf1 (REF. 155) | Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase |

| MtNSP1 (REF. 27) | LjNSP1 (REF. 156) | GRAS family transcriptional regulator |

| MtNSP2 (REF. 26) | LjNSP2 (REF. 156) | GRAS family transcriptional regulator |

| MtCRE1 (REF. 58) | LjLHK1 (REF. 59)(not required for infection thread formation) | Cytokinin receptor or histidine kinase |

| MtNIN61 | LjNIN157 | Predicted transmembrane transcription factor |

The earliest infection threads that penetrate the growing M. truncatula or M. sativa nodule must grow past the actively dividing cells in the developing nodule primordium14. Ultimately, cells adjacent to the initial primordium will give rise to a persistent nodule meristem that maintains a population of actively dividing cells and will continue to grow outward from the root for the life of the nodule8,14. M. truncatula and M. sativa are examples of indeterminate legumes, which form nodules that possess a persistent meristem. Determinate legumes, such as L. japonicus (BOX 2), produce nodules without a persistent meristem and in which all cells in the interior of the nodule proliferate, differentiate and senesce synchronously65. In developing indeterminate nodules, which we focus on here, infection threads grow through the developing meristematic zone to the underlying cell layers through which the wave of mitotic activity has already passed65. These layers of invasion-competent cells have exited mitosis and become polyploid owing to cycles of genomic endoreduplication without cytokinesis14,66. Plant cell endoreduplication is required for the formation of functional nodules, and is dependent on the degradation of mitotic cyclins by anaphase-promoting complex (APC), an E3 ubiquitin ligase66,67. The advantages of cellular polyploidy are a higher transcription rate and a higher metabolic rate than cells with the normal 2n DNA content68 — characteristics that might be important for the invaded plant cells to support bacterial nitrogen fixation (discussed later).

Endocytosis of rhizobia

When the bacteria reach the target tissue layer, the inner plant cortex, they must be internalized by a cortical cell and establish a niche within that cell. Each bacterial cell is endocytosed by a target cell in an individual, unwalled membrane compartment that originates from the infection thread48. The entire unit, consisting of an individual bacterium and the surrounding endocytic membrane, is known as the symbiosome48. In indeterminate nodules, a bacterial cell and its surrounding membrane divide synchronously before the bacteria differentiate into nitrogen-fixing bacteroids69. New lipid and protein material targeted to the symbiosome membrane imparts a distinct biochemical identity to this compartment69.

Both plant and bacterial defects can cause a failure of symbiosome formation. When the plant leucine-rich-repeat receptor kinase DMI2 is partially depleted by RNAi, the result is overgrown infection threads that fail to release bacteria into symbiosomes70. In wild-type infections, the DMI2 protein is localized to the infection thread and symbiosome membranes, which is consistent with a role for this protein in release of bacteria from infection threads and symbiosome development70. RNAi-mediated knockdown of the MtHAP2-1 gene, which encodes a predicted transcription factor, also prevents bacterial release from infection threads71. The M. truncatula nip mutant also produces overgrown infection threads and the bacteria fail to release from these infection threads72. The NIP gene has not yet been cloned, but it is likely that its gene product is involved in symbiosome development. Bacteria can also fail to release from infection threads owing to bacterial defects. The hemA mutant of S. meliloti, which has a primary defect in haem biosynthesis, is not released from infection threads and is not enclosed in symbiosomes73. Several bacterial components that are important for symbiosis are known to require haem, such as the oxygen sensor FixL and cytochrome haem proteins, which could explain this phenotype74,75.

Recent proteomic and immunolocalization studies have begun to define biochemical markers of the symbiosome membrane. These include previously identified nodule-specific proteins (ENOD8, ENOD16, nodulin 25 and nodulin 26), energy and transport proteins, bacterial proteins, and proteins predicted to be involved in folding, processing, targeting and storage76. Based on the types of protein that have been extracted from the symbiosome membrane, Catalano et al. proposed that proteins are added to this membrane by multiple mechanisms, one of which is being targeted by syntaxin proteins to the symbiosome via the Golgi and membrane-bound vesicles76. One particularly interesting protein that is predicted to be involved in the targeting of vesicles to the symbiosome membrane is the SNARE protein MtSYP132 (M. truncatula syntaxin of plants 132)77. Syntaxins are involved in the docking of vesicles at the target membrane, and might be crucial for the development of the rhizobium-containing vesicle into a mature symbiosome78.

As rhizobial bacteria are enclosed in the symbiosome membrane by endocytosis, it has been assumed that this compartment is a derivative of the lytic vacuole (the plant counterpart to the mammalian lysosome)79,80. Consistent with this hypothesis, several enzymes that localize to the lumen of the soybean symbiosome, or the peribacteroid space, have an acidic pH optimum79. However, parallels have also been drawn between the symbiosome and plant protein-storage vacuoles that are initially a non-lytic niche79,81.

Bacteroid differentiation and survival

Once the bacteria have been engulfed within host cell membranes, they must survive within the symbiosome compartment and differentiate into the nitrogen-fixing bacteroid form. Both bacterial and plant factors are involved in these processes (FIG. 5).

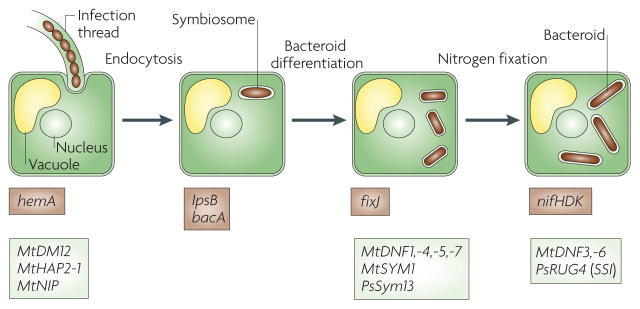

Figure 5. Endocytosis of bacteria and bacteroid differentiation.

Bacterial endocytosis requires the Sinorhizobium meliloti hemA gene73, the Medicago truncatula NIP gene72 and wild-type expression levels of the MtDMI2 (REF. 70) and MtHAP2-1 (REF. 71) genes. S. meliloti lpsB82 and bacA83 are required for bacterial survival within the symbiosome membrane. S. meliloti fixJ98, M. truncatula MtSYM1 (REF. 64), MtDNF1, -4, -5 and -7 (REFS 62,63), and pea (Pisum sativum) PsSYM13 (REF. 95) are required for bacteroid differentiation. The S. meliloti nifHDK genes encode nitrogenase and are required for nitrogen fixation98. The pea PsRUG4 gene encodes sucrose synthase and is required to support bacteroid nitrogen fixation115,116. The M. truncatula MtDNF3 and -6 genes are required for the maintenance of nitrogen fixation62,63. The required rhizobial genes are boxed in brown and the required plant genes are boxed in light green.

LPS and rhizobial survival

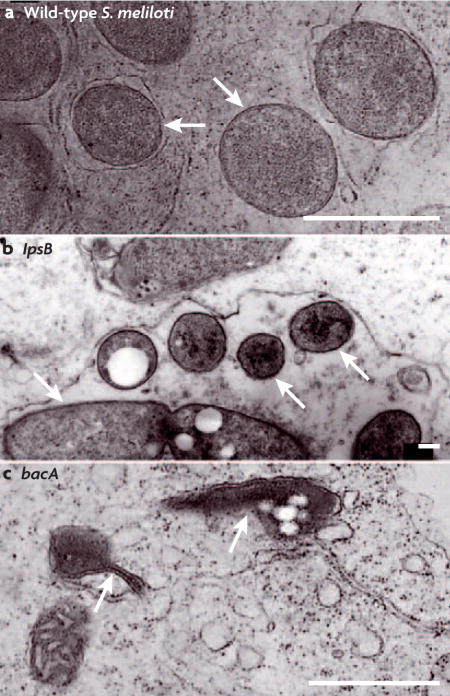

One of the most important defence mechanisms that Gram-negative bacteria use against the extracellular environment is the lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a major component of the outer membrane. LPS consists of a lipid A membrane anchor attached to a polysaccharide core that in turn is attached to an O-antigen repeating unit82. The S. meliloti bacA gene is required by S. meliloti for the production of lipid A of the appropriate structure and for survival within host cells83,84 (BOX 3). The bacA mutant cells lyse soon after endocytosis and do not exhibit any morphological changes that are characteristic of bacteroids, such as cell elongation83. BacA is required for modification of lipid A with a very-long-chain fatty acid moiety, and the fatty acid defect may be the cause of the bacA mutant symbiotic defect84 (BOX 3). An S. meliloti lpsB mutant produces an LPS core with an altered sugar composition82 (BOX 3). Although it can invade the plant root, become enclosed within a symbiosome membrane and begin to elongate into the bacteroid form, it cannot complete the bacteroid differentiation programme and fix nitrogen82. The lpsB mutant symbiotic defect is probably a result of its compromised outer membrane; however, as these bacteria also appear to lack contact with the plant symbiosome membrane, it is possible that they fail to survive because they cannot interact properly with the host82.

Box 3. Host invasion parallels between rhizobia and animal pathogens.

Symbiotic rhizobial bacteria and pathogenic Brucella species both form chronic infections of eukaryotic cells within a host-membrane-derived compartment158. Brucella spp. are α-proteobacteria that are closely related to Sinorhizobium meliloti and invade mammalian cells, causing brucellosis159. Both Brucella spp. and S. meliloti must gain entry to target host cells and prevent their own destruction by the lytic compartments of these cells. Bacterial production of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with the appropriate structure (see main text) is important for survival of both Brucella spp. and S. meliloti within host cells. The S. meliloti lpsB mutant produces an LPS core with altered sugar composition (see figure) and the Brucella abortus pmm mutant produces a truncated LPS core82,160,161. Neither mutant can survive within host cells and this might be because their outer membranes are compromised82,160. These mutants are also sensitive to detergents and to antimicrobial peptides, such as polymyxin B, that resemble defence compounds produced by phagocytic cells and plant cells82,162,163. LPS lipid A, with the appropriate structure, might also be important for the survival of S. meliloti and B. abortus within their respective hosts83,158. The bacA gene encodes a predicted inner membrane protein with similarity to peroxisomal-membrane transporters of fatty acids and is required for the modification of lipid A with very-long-chain fatty acids in both S. meliloti and B. abortus (see figure)84. However, S. meliloti mutants that are unable to synthesize this modified lipid A in the free-living form can form an effective symbiosis, raising the possibility that another function of BacA is required164. The production of periplasmic cyclic β-glucans is required for Brucella spp. to survive within intracellular compartments and for S. meliloti to adhere to root hair cells29,165. During host cell invasion by B. abortus, cyclic β-glucans prevent fusion of the bacteria-containing endocytic vacuole with the lysosome, by modulating lipid raft organization in host cell membranes165. This suggests that cyclic β-glucans are critical for correct cell surface interactions of B. abortus with endocytic vacuole membranes and of S. meliloti with root hair cells.

Regulatory genes conserved between Brucella spp. and S. meliloti are also important for either invasion or persistence within their respective hosts. For example, the B. abortus bvrS/bvrR sensor kinase/response regulator system is required for intracellular survival31,166. The B. abortus bvrS/bvrR system may be required for virulence, because it controls the expression of several outer membrane proteins and is involved in modulating the properties of bacterial lipopolysaccharide 162,167. It has not been possible to construct null mutants of the S. meliloti homologues of these genes, exoS and chvI, indicating that they are essential32,168. However, a mutant that produces a constitutively active ExoS sensor kinase is partially impaired in its ability to infect root hairs (see main text)31–33. A Tn5 insertion mutant of another S. meliloti sensor kinase, cbrA, is also symbiotically defective169. This mutant is sensitive to agents that stress the bacterial membrane, and this may be the cause of its symbiotic defect169. The B. abortus homologue of cbrA, pdhS, is essential for viability and therefore it has not been possible to assess its requirement for pathogenesis170. Panels a and c reprinted with permission from REF. 83 © (1993) Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Panel b reprinted with permission from REF. 82 © (2002) National Academy of Sciences. The scale bars represent 1 μm for a and c, and 0.21 μm for b.

Non-LPS factors and rhizobial survival

S. meliloti mutants that are defective in other aspects of physiology are also defective in symbiosis with the plant host. The sitA mutant invades plant cells at a reduced efficiency, but the bacteroids formed are senescent and cannot effectively fix nitrogen55. The sitA gene encodes a component of a manganese transporter, and the mutant cannot grow in minimal medium without additional manganese55. Although this mutant is sensitive to ROS, this is apparently not the cause of the symbiotic defect, suggesting that an Mn2+-requiring enzyme or intracellular Mn2+ homeostasis is important for symbiosis55. Mutants in the pha gene cluster have a symbiotic phenotype that is similar to that of sitA mutants, with a reduced efficiency of infection and formation of senescent bacteroids85. Interestingly, the product of the pha gene cluster is a K+-efflux system that is active under alkaline conditions85. This suggests that mechanisms that cope with specific ion stress are required for the bacteria that invade, and to persist in, the intracellular environment. Mutants that are defective in global bacterial transcriptional responses under stress conditions are also defective in symbiosis. A mutant in rpoH1, encoding a putative σ32-factor that is predicted to interact with bacterial RNA polymerase, appears to invade normally, but forms bacteroids that senesce prematurely86. By contrast, a mutant in relA is defective at multiple stages in nodule formation87; relA mutants lack the stringent response — a bacterial transcriptional response to starvation87.

Plant control and support of bacteroid differentiation

The host plant exerts control over the survival of bacteria within the symbiosome, and must not only provide nutritional support and the correct micro-aerobic environment required for nitrogen fixation, but also provide specifications for part of the bacterial differentiation programme. In indeterminate nodules, the internalized bacteria and the symbiosome membrane divide concomitantly before bacteroid differentiation, whereas in determinate nodules, bacteria divide within the membrane compartment and form a small mass of cells88. Surprisingly, plants that form indeterminate nodules impose a programme of genomic endoreduplication on the invading bacterial cells65. Bacteroids within indeterminate nodules increase their DNA content and cell size, which might allow them to reach a higher metabolic rate to support nitrogen fixation65,68. The intensive DNA synthesis that is required for endoreduplication within bacteroids requires a large quantity of dNTPs that must be supplied by ribonucleotide reductase (RNR)89. For many bacterial species, performing DNA synthesis in both an oxygen-rich environment, such as the infection thread, and an oxygen-depleted environment, such as the symbiosome, would present a lethal problem. This is because most aerobes possess an oxygen-requiring class I RNR, whereas obligate anaerobes typically have an exquisitely oxygen-sensitive class III RNR90. Some bacterial species, including rhizobia, have an adaptation that circumvents this problem — they possess a vitamin B12-dependent class II RNR that functions independently of oxygen concentration. Significantly, when the class I RNR of Escherichia coli is substituted for the class II RNR from S. meliloti, survival within the nodule, but not free-living growth, is impaired (M. E. T. and G. C. W., unpublished data). Phosphate must also be obtained by bacteria during the invasion process. S. meliloti that is mutated in both the phoCDET and pstSCAB phosphate-transport systems forms small nodules that cannot fix nitrogen91,92. However, these transporters are not expressed by mature bacteroids, suggesting that the requirement for phosphate declines after differentiation92.

Plants control bacteroid differentiation and survival in other ways that are in the process of being characterized. Bacteria fail to differentiate or senesce prematurely in several mutants of the host plants M. truncatula and pea (Pisum sativum), but none of the genes carrying these mutations has yet been cloned62–64,93,94. In the pea sym13 mutant, symbiosome membranes are not closely associated with the bacteroid and the bacteroids senesce early95. Immunological detection of plant glycoproteins that are still attached to bacteroids isolated from pea nodules suggests that there is a close physical interaction between the symbiosome and bacteroid membranes, at least in indeterminate nodules where a single bacteroid is enclosed within each symbiosome membrane96,97. A close association between the bacteroid outer membrane and the symbiosome membrane might be important for nutrient exchange between the bacteria and the plant.

Nodule development and nutrient exchange

Bacteria that have been enclosed within a functional symbiosome membrane, have been provided with a low oxygen environment and have completed the bacteroid differentiation programme can express the enzymes of the nitrogenase complex and begin to fix nitrogen98. An oxygen-sensing bacterial regulatory cascade controls the expression of the nitrogenase complex and the microaerobic respiratory enzymes that are required to provide energy and reductant to nitrogenase98. This cascade is induced by the presence of low oxygen tension within the differentiating bacteroid89,99,100. The bacterial regulators include the oxygen-sensing two-component regulatory system FixL and FixJ, NifA, σ54 and FixK98. These regulators are responsible for many of the changes in gene and protein expression that have been detected during bacteroid differentiation2. In general, the transcriptional changes in bacteroids are consistent with the downregulation of most metabolic processes and a concomitant increase in the expression of the gene products involved in nitrogen fixation and respiration2. Respiratory activity provides nitrogenase with the 16 molecules of ATP and 8 electrons that are estimated to be required to reduce 1 molecule of N2 to 2 molecules of NH4+ (REF. 101).

The NH4+ produced by nitrogenase can be secreted by bacteroids. Once secreted, it is thought to be taken up by the plant through NH4+ channels that have been detected in the peribacteroid membrane and then assimilated88,102. A complex amino-acid cycling system between plant cells and bacteroids might prevent the bacteroids from assimilating NH4+, and allow NH4+ to be secreted for uptake by the plant88,101,103,104. Metabolite analysis and RNAi depletion experiments suggest that NH4+ assimilation by plant cells occurs primarily through glutamine and asparagine synthetases105–107. In L. japonicus, RNAi depletion of the next enzyme in the nitrogen assimilation pathway, glutamate synthase, results in a reduction of nitrogenase activity and the growth of stunted plants108.

A constant carbon supply is required to provide metabolites and energy for bacteroid differentiation and nitrogen fixation. Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) granules, produced by S. meliloti during the invasion process, are degraded during bacteroid differentiation and appear to be used preferentially as a carbon source at this stage109. Surprisingly, mutants in PHB synthesis (phbC) or degradation (bdhA) are symbiotically competent, indicating that alternate carbon sources are available to the bacteria during differentiation109–111. In a mixed infection, phbC and bdhA mutants are less competitive for nodule occupancy than the wild type, suggesting that the ability to synthesize and use PHB might allow the bacteria to compete in situations of reduced carbon availability109,111. Fixed carbon from the plant is provided to the bacteria in the form of dicarboxylic acids, such as malate, through the bacterial Dct uptake system101,112. NAD+-malic enzyme activity, which produces pyruvate directly from malate, is required for nitrogen fixation by S. meliloti113. This suggests that the production of acetyl-CoA from malate using malic enzyme and pyruvate dehydrogenase, is important for the funnelling of carbon into the TCA cycle in bacteroids101.

Some plant proteins, in addition to glutamate synthase, have been shown to be required to support nitrogen fixation. Leghaemoglobins are plant-produced, oxygen-binding proteins that impart a red colour to functional root nodules, and which, it has long been proposed, can adjust the microaerobic environment within nodules114. It has recently been confirmed by RNAi that L. japonicus leghaemoglobin is required for nitrogen fixation and to maintain a microaerobic environment in the nodule114. Another required plant protein is sucrose synthase (SS), which has been characterized in pea using the SS1-defective rug4 mutant115,116. Contrary to its name, sucrose synthase in pea nodules catabolizes sucrose to UDP-glucose and fructose, which is ultimately metabolized to malate and transported to bacteroids101,105,115. The L. japonicus sulphate transporter Sst1 is also required for nitrogen fixation and has been detected in symbiosome membranes117,118. Sulphate is required to form iron–sulphur clusters in nitrogenase subunits119. Transcript profiling and proteomic analysis of plant nodules have identified new candidates for RNAi that will almost certainly lead to the discovery of more plant factors required for nodulation2.

Bacteria in indeterminate nodules might further benefit from the symbiosis by scavenging for nutrients in the ghost plant cells that are located in the root proximal section of the nodule, in which the original bacteroids have already senesced120. These bacteria are released from infection threads into the decaying plant tissue and appear to proliferate. They do not differentiate into bacteroids or fix nitrogen and can probably resume a free-living lifestyle once the nodule has decayed120.

Rhizobial evasion of plant innate immunity

It remains to be determined how the host plants tolerate such intimate contact with invading rhizobial bacteria without attacking the invaded tissues. Plants, as well as animals, can mount innate immune responses to microorganisms in response to the perception of conserved microbial factors (microorganism-associated molecular patterns or MAMPs)121. This usually results in the activation of signalling cascades, and the production of antimicrobial effectors that help the organism ward off microbial attack121. However, the plant perception of microorganisms differs from that of animals in the domain structure of receptor proteins and, in many cases, the epitopes perceived121. In the interaction between plants and rhizobial bacteria, some bacterial factors activate innate immune responses whereas other bacterial factors suppress these responses122. Defining how plants perceive the conserved microbial molecular patterns of rhizobia and respond to them is currently an active area of research.

MAMPs and host-specific elicitors

Microbial factors that induce innate immune responses in plants are classified as either general or host-specific elicitors52. General elicitors include flagellin, elongation factor Tu (EFTu), cold shock protein (CSP), chitin and LPS123–125. These compounds are conserved across multiple groups of bacteria, allowing plants to perceive and respond to an epitope that is common to many bacteria123–125. Plants respond to general elicitors with basal defence responses that can impart a measure of resistance to infection52. Basal defences include increases in extracellular pH, ethylene, ROS and reactive nitrogen species, phenolic compounds and changes in intracellular Ca2+, as well as cell signalling cascades and transcriptional changes52. Many plant species mount basal defence responses to the broadly conserved flg22 peptide found in bacterial flagellin123. However, rhizobial bacteria, along with many other α-proteobacteria, such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Brucella spp., do not have the flg22 epitope as part of their flagellin sequence126,127. Two other bacterial epitopes that induce plant defence responses are the elf18 peptide of EFTu and the csp15 peptide from bacterial CSP123. These peptides are conserved in rhizobial bacteria; however legumes lack the ability to mount an innate response to them123. Comparisons have been made between plant basal defence responses to pathogens and plant responses to rhizobial Nod factor51. One model, suggested by the production of ROS during infection thread formation, is that rhizobial effectors, such as Nod factor, provoke a defence reaction in host plants that is attenuated or modified by other rhizobial effectors, such as LPS (see below)51,128,129.

Unlike general elicitors, most host-specific elicitors are effector proteins that are injected by pathogens into plant cells by bacterial type 3 secretion systems (T3SSs) and which cause a hypersensitive response and programmed cell death52. These responses are more extreme and cause more tissue damage than basal defence responses52. One example is the root pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum, which requires the GALA7 type 3 secreted protein to cause wilting disease on M. truncatula130.

Nod factor and chitin

Chitin is another general elicitor that induces plant innate immune responses, such as the oxidative burst124. This response helps plants defend themselves against fungal attack, as chitin is a component of fungal cell walls124. Intriguingly, the chitin receptor of rice (Oryza sativa) is a LysM-domain-containing protein, as are the Nod factor receptors MtNFP and MtLYK3131. One possibility is that plant proteins containing extracellular, chitin-interacting LysM domains were co-opted in the legume lineage to recognize bacterially produced lipochitooligosaccharide Nod factors.

Negative feedback on nodulation

Plant defence responses have been implicated in restricting the number of nodules that form on a colonized root. After an initial round of nodule formation has begun, subsequent nodulation events are subject to autoinhibition132. Signalling that is antagonistic to the early responses to Nod factor is mediated by the plant hormones ethylene and jasmonic acid, which are involved in defence signalling in other plant–microorganism interactions52,133. It has been proposed that autoinhibition is controlled by the plant by the abortion of infection threads134. Late-initiating infection threads that abort are associated with necrotic cells, and with the accumulation of defence-related proteins and phenolic compounds in plant cells and cell walls134. This type of cellular damage is also found near aborted infection threads and failed symbiosomes formed by M. truncatula lin, nip and sym6 mutants, and aborted infection threads formed on wild-type M. sativa plants by S. meliloti exoY mutants29,43,72,122,134–136. M. truncatula plants inoculated with the exoY mutant also express several plant defence genes more strongly than plants inoculated with wild-type S. meliloti (K. M. J. and G. C. W., unpublished data). Another study established that plants depleted for a calcium-dependent protein kinase by RNAi over-express defence genes and have a reduced efficiency of nodulation137. It remains to be determined whether plant defence responses are a cause of infection thread abortion or a consequence of the failure of infection thread progression, and how the absence of succinoglycan might influence these defence responses.

Exopolysaccharides and β-heptaglucoside

It has been proposed that the exopolysaccharide(s) produced by a rhizobial species are actively involved in suppress ing defence responses in the host plant122. In fact, soybean defence responses provoked by the β-heptaglucoside elicitor from the plant pathogen Phytophthora sojae can be suppressed by cyclic-β-glucans produced by the soybean symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum138. As B. japonicum cyclic-β-glucans are effective antagonists of the soybean β-heptaglucoside receptor, the most likely mechanism for this suppression is competition for the same binding sites139. Legumes are the only plant group that possess the β-heptaglucoside receptor and the ability to mount a defence response to this elicitor140.

LPS

In most plant species, the response to bacterial LPS is different from the toxic shock that can be induced in animals141. Inoculation of a leaf with purified LPS from a plant pathogenic strain can often induce localized resistance in the treated tissue to subsequent infection by that strain141. In many cases, LPS pretreatment can prevent a plant hypersensitive response that would result in catastrophic tissue damage141. One possible explanation is that antimicrobials produced in the LPS-treated leaf tissue prevent the bacteria from proliferating enough to activate a hypersensitive response141. By contrast, plant cells in culture often respond to LPS fractions from bacteria with an oxidative burst and transcription of defence genes125. For example, S. meliloti LPS core oligosaccharide can induce an oxidative burst in cultured cells of the non-host plant tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum)128. However, the lipid A component of S. meliloti LPS can suppress both an oxidative burst and the expression of defence genes in cultured cells of its host plants M. truncatula and M. sativa128,129. An exciting area of research is in determining which LPS epitopes from rhizobial bacteria and plant pathogens elicit or suppress defence responses on plants of different lineages. Interestingly, the LPS lipid A component of Brucella abortus, which has a very similar structure to that of S. meliloti, is much less toxic to animal cells than the lipid A of other bacterial species84,142 (BOX 3).

Future perspectives

It is safe to say that the field of rhizobial–plant symbioses is booming. The genomes of multiple rhizobial species have been sequenced and the genomes of the model host plants M. truncatula and L. japonicus are nearing completion. The cloning of plant Nod factor receptors and signal transduction intermediates, and the dissection of early plant responses to Nod factor have opened a door between symbiosis research and the field of plant signal transduction. Plant hormones and signalling components are sure to have an even more prominent role in future symbiosis studies. Dissecting the plant signalling events that permit the subsequent steps of infection thread formation and bacterial endocytosis will be equally exciting. Another conceptual advance has been the recognition that rhizobia have many features in common with their mammalian pathogen cousins that also reside within intracellular, host-membrane-derived compartments. Despite the differences in the impact on the host of symbiotic and pathogenic bacteria, strategies that mammalian pathogens use to interact with their hosts and to survive within host cells should continue to provide clues as to how rhizobial bacteria accomplish the same mission.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to B. K. Minesinger, S. M. Simon, R. V. Woodruff and the reviewers for their helpful comments. We would like to thank members of the Walker laboratory for helpful discussions, and the National Institutes of Health (USA), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the National Science and Research Council of Canada, and the Jane Coffin Childs Fund for Medical Research for funding. G. C. W. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

- Flavonoid

A 2-phenyl-1,4-benzopyrone derivative, produced by plants, that serves as a defence and signalling compound

- Nod factor

A lipochitooligosaccharide compound that induces multiple responses that are required for nodulation of appropriate host plants

- Symbiotic exopolysaccharide

A rhizobial secreted β-glucan that is structurally distinct for different species and that mediates infection thread formation

- Infection thread

An ingrowth of the root hair cell membrane, populated with rhizobial bacteria, that progresses inward by new membrane synthesis at the tip

- Symbiosome

A host-derived membrane compartment that originates from the infection thread housing a bacteroid

- Bacteroid

A rhizobial bacterium that has been endocytosed by a plant cell and has elongated and/or branched, and has differentiated or is differentiating into a form that can perform nitrogen fixation

- Nitrogen fixation

The reduction of atmospheric dinitrogen to ammonia

- Colonized curled root hair

A root hair that has been induced by Nod factor to curl around a microcolony of rhizobial bacteria and entrap it

- Auxin

A plant hormone (chiefly indole acetic acid) that regulates plant growth in a concentration-dependent manner

- Nodule primordium

Dedifferentiated, proliferating tissue that develops in the plant cortex during nodule initiation

- Cyclic β-glucan

A cyclized β-1,2 chain of 17–25 glucose residues produced by rhizobial bacteria, Brucella spp. and Agrobacterium spp. that localizes to the periplasm and that functions in osmotolerance and in interaction with host membranes

- Succinoglycan

A symbiotic exopolysaccharide produced by S. meliloti, also known as EPS I, that mediates infection thread formation. An octasaccharide repeating unit modified with acetyl, succinyl and pyruvyl substituents that can be polymerized into a high molecular weight or a low molecular weight form composed of monomers, dimers and trimers

- Galactoglucan

A second exopolysaccharide of S. meliloti (EPS II) that can mediate infection thread formation on M. sativa at a low efficiency and that is produced when an intact copy of the ExpR regulator is present. A disaccharide repeating unit modified with acetyl and pyruvyl substituents

- Endoreduplication

Genomic replication without cytokinesis that results in greater than 2n DNA content within a cell

- Indeterminate nodule

A nodule formed by plants of some clades of legumes that develops a continuously growing nodule meristem at the distal end and has zones of tissue at different stages of development

- α-proteobacteria

A group of bacteria that contains several species able to persist within host-derived membrane-bound compartments in eukaryotic cells. Includes rhizobial bacteria and mammalian pathogens such as Brucella spp., Bartonella spp. and Rickettsia spp

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATABASES

The following terms in this article are linked online to:

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene

bacA | bdhA | hemA | katA | oxyR | phbC | sitA

Entrez Genome Project: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=genomeprj

Lotus japonicus | Medicago sativa | Medicago truncatula | Sinorhizobium meliloti

Entrez Protein: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene

Nod D1 | Nod D2 | Nod D3

UniProtKB: http://ca.expasy.org/sprot

leghaemoglobin | MtNFP

FURTHER INFORMATION

Graham C. Walker’s homepage: http://web.mit.edu/biology/www/facultyareas/facresearch/walker.html

Access to this links box is available online.

References

- 1.Perret X, Staehelin C, Broughton WJ. Molecular basis of symbiotic promiscuity. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:180–201. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.180-201.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett MJ, Fisher RF. Global gene expression in the rhizobial–legume symbiosis. Symbiosis. 2006;42:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peck MC, Fisher RF, Long SR. Diverse flavonoids stimulate NodD1 binding to nod gene promoters in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5417–5427. doi: 10.1128/JB.00376-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldroyd GE, Downie JA. Calcium, kinases and nodulation signalling in legumes. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:566–576. doi: 10.1038/nrm1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook DR. Unraveling the mystery of Nod factor signaling by a genomic approach in Medicago truncatula. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4339–4340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400961101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geurts R, Fedorova E, Bisseling T. Nod factor signaling genes and their function in the early stages of Rhizobium infection. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oldroyd GE, Downie JA. Nuclear calcium changes at the core of symbiosis signalling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timmers AC, Auriac MC, Truchet G. Refined analysis of early symbiotic steps of the Rhizobium–Medicago interaction in relationship with microtubular cytoskeleton rearrangements. Development. 1999;126:3617–3628. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3617. The definitive microscopy study of plant cytological changes during infection thread formation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sieberer BJ, Timmers AC, Emons AM. Nod factors alter the microtubule cytoskeleton in Medicago truncatula root hairs to allow root hair reorientation. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2005;18:1195–1204. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardenas L, et al. The role of nod factor substituents in actin cytoskeleton rearrangements in Phaseolus vulgaris. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2003;16:326–334. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Ruijter NCA, Bisseling T, Emons AMC. Rhizobium Nod factors induce an increase in subapical fine bundles of actin filaments in Vicia sativa root hairs within minutes. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1999;12:829–832. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esseling JJ, Lhuissier FG, Emons AM. Nod factor-induced root hair curling: continuous polar growth towards the point of nod factor application. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1982–1988. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021634. Demonstrated that Nod factor has a directional effect on root hair polar tip growth. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gage DJ. Infection and invasion of roots by symbiotic, nitrogen-fixing rhizobia during nodulation of temperate legumes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:280–300. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.280-300.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foucher F, Kondorosi E. Cell cycle regulation in the course of nodule organogenesis in Medicago. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;43:773–786. doi: 10.1023/a:1006405029600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidstra R, et al. Ethylene provides positional information on cortical cell division but is not involved in Nod factor-induced root hair tip growth in Rhizobium–legume interaction. Development. 1997;124:1781–1787. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.9.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasson AP, Pellerone FI, Mathesius U. Silencing the flavonoid pathway in Medicago truncatula inhibits root nodule formation and prevents auxin transport regulation by rhizobia. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1617–1629. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amor BB, et al. The NFP locus of Medicago truncatula controls an early step of Nod factor signal transduction upstream of a rapid calcium flux and root hair deformation. Plant J. 2003;34:495–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01743.x. Identified an M. truncatula mutant that was completely devoid of responses to Nod factor. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arrighi JF, et al. The Medicago truncatula lysine motif-receptor-like kinase gene family includes NFP and new nodule-expressed genes. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:265–279. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.084657. Cloned the NFP-encoded Nod factor receptor and demonstrated that it has a role in infection thread formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Limpens E, et al. LysM domain receptor kinases regulating rhizobial Nod factor-induced infection. Science. 2003;302:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1090074. Identified and cloned the MtLYK3 and MtLYK4 Nod factor receptors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ane JM, et al. Medicago truncatula DMI1 required for bacterial and fungal symbioses in legumes. Science. 2004;303:1364–1367. doi: 10.1126/science.1092986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riely BK, Lougnon G, Ane JM, Cook DR. The symbiotic ion channel homolog DMI1 is localized in the nuclear membrane of Medicago truncatula roots. Plant J. 2007;49:208–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitra RM, et al. A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for symbiotic nodule development: gene identification by transcript-based cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4701–4705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400595101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy J, et al. A putative Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for bacterial and fungal symbioses. Science. 2004;303:1361–1364. doi: 10.1126/science.1093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gleason C, et al. Nodulation independent of rhizobia induced by a calcium-activated kinase lacking autoinhibition. Nature. 2006;441:1149–1152. doi: 10.1038/nature04812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esseling JJ, Lhuissier FG, Emons AM. A nonsymbiotic root hair tip growth phenotype in NORK-mutated legumes: implications for nodulation factor-induced signaling and formation of a multifaceted root hair pocket for bacteria. Plant Cell. 2004;16:933–944. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalo P, et al. Nodulation signaling in legumes requires NSP2, a member of the GRAS family of transcriptional regulators. Science. 2005;308:1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1110951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smit P, et al. NSP1 of the GRAS protein family is essential for rhizobial Nod factor-induced transcription. Science. 2005;308:1789–1791. doi: 10.1126/science.1111025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charron D, Pingret JL, Chabaud M, Journet EP, Barker DG. Pharmacological evidence that multiple phospholipid signaling pathways link Rhizobium nodulation factor perception in Medicago truncatula root hairs to intracellular responses, including Ca2+ spiking and specific ENOD gene expression. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3582–3593. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.051110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickstein R, Bisseling T, Reinhold VN, Ausubel FM. Expression of nodule-specific genes in alfalfa root nodules blocked at an early stage of development. Genes Dev. 1988;2:677–687. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.6.677. First demonstrated that cyclic-β-glucan mutants and exopolysaccharide mutants of S. meliloti lack infection threads. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dylan T, Nagpal P, Helinski DR, Ditta GS. Symbiotic pseudorevertants of Rhizobium meliloti ndv mutants. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1409–1417. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1409-1417.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao SY, et al. Sinorhizobium meliloti ExoR and ExoS proteins regulate both succinoglycan and flagellum production. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6042–6049. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.18.6042-6049.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng HP, Walker GC. Succinoglycan production by Rhizobium meliloti is regulated through the ExoS-ChvI two-component regulatory system. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:20–26. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.20-26.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang XS, Cheng HP. Identification of Sinorhizobium meliloti early symbiotic genes by use of a positive functional screen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2738–2748. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2738-2748.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein S, Hirsch AM, Smith CA, Signer ER. Interaction of nod and exo Rhizobium meliloti in alfalfa nodulation. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1988;1:94–100. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-1-094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gage DJ. Analysis of infection thread development using Gfp- and DsRed-expressing Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:7042–7046. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.7042-7046.2002. Demonstrated that only bacteria near the tip of an infection thread proliferate and progress into plant tissue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pellock BJ, Cheng HP, Walker GC. Alfalfa root nodule invasion efficiency is dependent on Sinorhizobium meliloti polysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4310–4318. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4310-4318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glazebrook J, Walker GC. A novel exopolysaccharide can function in place of the calcofluor-binding exopolysaccharide in nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. Cell. 1989;56:661–672. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90588-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinhold BB, et al. Detailed structural characterization of succinoglycan, the major exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti Rm1021. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1997–2002. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1997-2002.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng HP, Walker GC. Succinoglycan is required for initiation and elongation of infection threads during nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5183–5191. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5183-5191.1998. Showed that succinoglycan must be succinylated and acetylated to efficiently facilitate infection thread formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.York GM, Walker GC. The succinyl and acetyl modifications of succinoglycan influence susceptibility of succinoglycan to cleavage by the Rhizobium meliloti glycanases ExoK and ExsH. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4184–4191. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4184-4191.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laus MC, van Brussel AA, Kijne JW. Exopolysaccharide structure is not a determinant of host-plant specificity in nodulation of Vicia sativa roots. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2005;18:1123–1129. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ardourel M, et al. Rhizobium meliloti lipooligosaccharide nodulation factors: different structural requirements for bacterial entry into target root hair cells and induction of plant symbiotic developmental responses. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1357–1374. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.10.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuppusamy KT, et al. LIN, a Medicago truncatula gene required for nodule differentiation and persistence of rhizobial infections. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3682–3691. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.045575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Middleton PH, et al. An ERF transcription factor in Medicago truncatula that is essential for Nod factor signal transduction. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1221–1234. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sieberer BJ, Ketelaar T, Esseling JJ, Emons AM. Microtubules guide root hair tip growth. New Phytol. 2005;167:711–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Esseling JJ, Emons AM. Dissection of Nod factor signalling in legumes: cell biology, mutants and pharmacological approaches. J Microsc. 2004;214:104–113. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2720.2004.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vassileva VN, Kouchi H, Ridge RW. Microtubule dynamics in living root hairs: transient slowing by lipochitin oligosaccharide nodulation signals. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1777–1787. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brewin NJ. Plant cell wall remodelling in the Rhizobium–Legume symbiosis. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2004;23:293–316. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandenbosch KA, et al. Common components of the infection thread matrix and the intercellular space identified by immunocytochemical analysis of pea nodules and uninfected roots. EMBO J. 1989;8:335–341. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03382.x. The first immunological detection of antigens localizing to the infection thread. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]