Abstract

Recent studies have demonstrated that network approaches are highly appropriate tools for understanding the extreme complexity of the aging process. Moreover, the generality of the network concept helps to define and study the aging of technological and social networks and ecosystems, which may generate novel concepts for curing age-related diseases. The current review focuses on the role of protein-protein interaction networks (inter-actomes) in aging. Hubs and inter-modular elements of both interactomes and signaling networks are key regulators of the aging process. Aging induces an increase in the permeability of several cellular compartments, such as the cell nucleus, introducing gross changes in the representation of network structures. The large overlap between aging genes and genes of age-related major diseases makes drugs that aid healthy aging promising candidates for the prevention and treatment of age-related diseases, such as cancer, atherosclerosis, diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders. We also discuss a number of possible research options to further explore the potential of the network concept in this important field, and show that multi-target drugs (representing 'magic-buckshots' instead of the traditional 'magic bullets') may become an especially useful class of age-related drugs in the future.

Introduction: network approaches for the study of the aging process

Aging is one of the most multifactorial, complex processes of living organisms. In spite of this complexity, until very recently the majority of studies focused on separate elements of the aging process. The multiplicity of research approaches in this field has contributed to the large number of theories and definitions in relation to aging:

• according to the antagonistic pleiotropy theory of aging, genes that are preferable during early development become detrimental in the aged organism

• the disposable soma theory of aging highlights the relocation of resources from somatic maintenance towards increased fertility, leading to a slow deterioration of the organism

• the reliability theory gives a rather descriptive picture of aging, emphasizing that aging is a phenomenon of increasing risk of failure with the passage of time

• the network theory of aging integrates many elements of the previous theories and describes the shifting balance between various types of damage and repair mechanisms during aging of cellular systems. The young state is characterized by well-repaired damage, while the aged organism cannot cope with the accumulated damage, and gradually surrenders [1-6].

Aging is accompanied by a number of age-related diseases, which include cancer, atherosclerosis, diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and others. Novel approaches are required for the understanding and complex treatment of these interrelated diseases.

The network approach has proved to be a highly efficient tool to describe the aging process and age-related diseases, since it provides an adequate framework to contain the multitude of factors influencing aging and longevity, and enables investigators to transfer the knowledge gained in the examination of other complex systems to explain the rather elusive phenomenon of aging [4-6]. For network description, we have to identify separable subsets of the system as network elements, and list their interactions as network contacts or links. Most network elements are also full networks themselves. Thus, in addition to being elements of social networks, human individuals are constituted by networks of organs and cells: cells are networks of proteins, and proteins are networks of amino acids. Networks display a lot of rather general properties, such as:

• small-worldness providing short pathways between most network elements

• scale-free topology (scale-free distribution of elements having various numbers of neighbors, meaning that the probability of finding an element with twice as many neighbors is halved) enabling the existence of hubs, which have a much higher number of neighbors than the average

• a community structure separating the networks into various overlapping groups

• co-existence of strong and weak links, where the link strength is usually defined as the real, physical strength of the connection, or as the probability of interactions

• existence ofa network skeleton, which is the subset of most important pathways within the network.

Networks provide a framework for the conceptualization of the aging process, but can also be used to understand aging in many ways. We may follow changes in the structure of the network during the aging process. One of the possible networks may be the protein-protein interaction network of the cell, where network elements are the cellular proteins and their links represent their physical interactions. We may also examine correlation networks, where elements that show parallel changes in a given time period are connected. The elements of various correlation networks may be proteins or genes, but also intracellular organelles, or neurons. Aging typically induces the disorganization of correlated changes, but novel elements of coherent behavior can also be observed. All of these can be nicely demonstrated and analyzed in the network representation. Subnetworks may also be defined, where the elements are restricted to only those genes (proteins) that participate in the aging process.

Networks provide a general framework for our understanding of the complexity of life, human conceptualization, culture and technology. It is therefore not surprising that the analysis of the phenomenon of aging can be expanded by the application of a network approach. Table 1 shows a few hierarchical examples of the aging process at different levels, from quantum systems, through the more familiar aging of proteins, cells, and organisms, up to the aging of ecosystems (such as forests), social groups (such as the economy) and human technological networks (such as our Windows programs) [6-15]. This generalization of the concept of aging will give us several novel approaches (and repair methods) to better understand the aging process and to approach therapy for age-related diseases in entirely novel ways.

Table 1.

Conceptualization of the aging process at the different hierarchical network levels

| Elements of the hierarchical network level | Hallmarks of the aging process |

|---|---|

| Elementary particles of quantum systems | Physical equations do not change in time (for example, Newton's laws have not changed in the past few centuries). However, the equations describing a system in a non-equilibrium state do change - this is called an aging process, which is a typical behavior of quantum particles embedded in a thermal bath, or of semi-ordered, glassy materials [7,8] |

| Monomers of biological macromolecules (amino acids, nucleotides, and so on) | Unrepaired replication, transcription and translation errors accumulate. Various forms of protein (and nucleic acid) damage become more and more prevalent (for example, in an 80-year-old human, half of all proteins are estimated to be oxidized): cross-links, occasional proteolytic cuts, amino acid truncations develop [6] |

| Proteins | Due to energy loss and protein damage, protein-protein interactions may disappear or lose their affinity. Novel, unexpected, quasi-random protein interactions may also occur. Protein complex composition becomes 'wobbly', fuzzy. Proteins are dislocated and appear in unusual cellular compartments [9,10] |

| Cells | Intercellular interactions may become irreversibly tight (for example, by developing cross-links) or too loose, gradually loosing their high-affinity contacts. Since the development of intercellular contacts is costly, functional brain networks show loss of their small-world properties in age-related Alzheimer's disease [11] |

| Organisms | The social network of aged individuals usually deteriorates and shrinks, keeping only the most important contacts for major remaining social functions. This contributes to age-related cognitive decline and to the loss of emotional support leading to increased frailty [12]. Ecosystems like forests also show the hallmarks of aging [13] |

| Social groups | A network of social groups, such as a network of firms, may also display the signs of aging as has been shown in the declining network of the New York garment industry by Brian Uzzi and colleagues [14] |

| Ecosystems forming a global ecological network | Aging research into the global ecosystem of Earth, Gaia, is in its infancy at the moment. However, our increasingly integrated knowledge, such as the global river network [15], gives us more and more tools to assess the rather worrisome aging of our habitat |

| Elements of human conceptual, cultural and technological systems | Human conceptual networks (such as arguments over a complex issue; cross-references in textbooks, and so on), cultural networks (such as the network of actors in a Shakespeare drama, movie actor networks, and so on), or technological networks (such as electric power grids, computer programs, the internet, and so on) may also show typical signs of aging. As a trivial example, we all experience more frequent errors of our Windows program network when the system gets older |

Since the creation and maintenance of newly established links between two network elements are costly, and aging is usually accompanied by a decline in the system's resources, aging generally induces a loss of links, leading to a declining network. However, aging is also hallmarked by the emergence of non-specific contacts due to the impaired recognition or positioning of potential partners. The increase of non-specific contacts leads to the appearance of novel links within the network, which affect the global network topology. Small-worldness is often lost during aging (distant elements cannot find each other so easily in an aged network), and many times elements with a large number of contacts (hubs) vanish, or, inversely, specific age-related hubs appear [6,10].

Link removal and link appearance are continuous, parallel events in the dynamic life of most networks. Somewhat surprisingly, their balance does not usually result in a 'mixed' network structure, but rather results in two distinguishable network forms. One of them is the 'forever-young', 'ageless', r-strategist-like (proliferation-optimized) network, where link formation is prevalent, the overlap of network communities (modules) is high, and the structure is flexible. The other prevalent type is the 'always old', overspecialized, K-strategist-like (survival-optimized) network, where link decay is most common, the overlap of network communities is small, and the structure is rigid [16]. The shift of topology towards a less overlapping, more rigid structure might by itself suggest the aging of the system described by a given network.

Networks not only age themselves, but also affect the aging of their components. The network context may slow down the aging of network elements, exemplified by the effect of social networks on elderly people [12]. On the contrary, networks may also channel unexpected damage, leading to an accelerated aging of their components, in a similar way as the avalanche of mitochondria-related free radicals accelerates the aging of all surrounding molecules [17].

Cellular networks may be divided into six categories [6]: three structural networks, including protein-protein interactions, cytoskeletal and membrane-organelle networks, and three functional networks, including gene transcription, signaling and metabolic networks. Our review focuses on the protein-protein interaction networks among these cellular networks.

Protein-protein interaction networks in aging

In protein-protein interaction networks (interactomes), elements are proteins and the links between them are their physical interactions. Ideally, the weight of a protein-protein interaction link should correspond to the affinity (strength) of the physical interaction between the two proteins. However, current protein-protein interaction databases use agglomerated data, which conceptualize the weight as the probability of the actual interaction and average the important effects of simultaneous expression, intracellular compartmentalization, post-translational modifica tions and so on. Due to this probability function-like network concept, the links of protein-protein interaction networks usually do not have directions. Signaling networks may be considered as subnetworks of protein-protein interaction networks, where the elements (signaling molecules) represent a segment of the proteins participating in the complete interactome, and are connected with directed and (so-called) colored links, where colors show if the interaction has an activating or inhibiting role.

Protein-protein interaction network of aging-associated genes

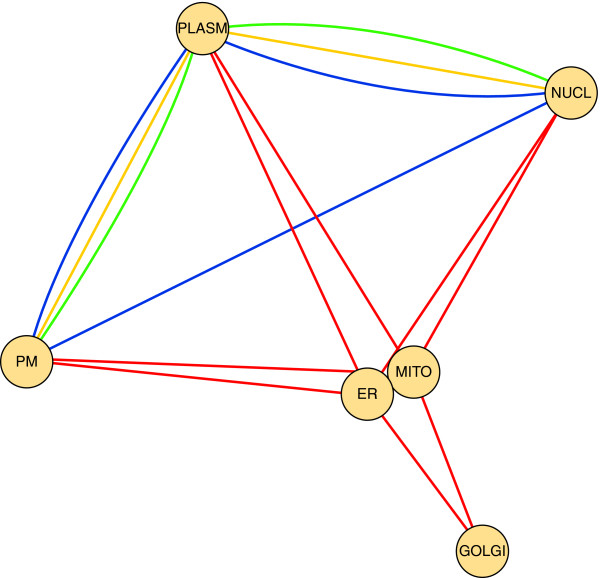

The protein-protein interaction network of aging-associated genes (or longevity networks as referred to by Budovsky et al. [18]) is another subnetwork of the inter-actome containing the proteins of aging-related genes [19] as well as the links between them. Figure 1 shows the human protein-protein interaction network of aging-associated genes [19-21]. Importantly, the network is a continuous network; only the GHRH (growth hormone-releasing hormone) and GHRHR (GHRH receptor) aging-associated proteins are not participating in its giant component shown in the figure. The extensive coverage of age-related genes by the giant component of the related longevity network has also been shown by Budovsky et al. [18]. The network shown in Figure 1 includes a large number of key signaling proteins. p53 and GRB2 (growth factor receptor-bound protein) are two prominent hubs having a large number of neighbors and occupying a central position in the network characterized by a high 'betweenness centrality'. p53 is a transcription factor that plays a prominent role in the regulation of the cell cycle stress response, apoptosis, and has both aging and anti-aging effects [22]. GRB2 is an important adaptor protein in growth signaling, although its direct role in aging has not been elucidated yet. Members of the MAPK/ERK (mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase), PI3K/AKT (phosphoinositide-3-kinase/protein kinase B) and JAK/STAT (Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathways are among the 20 largest hubs of the network (Figure 1). These pathways occupy key positions of the network, suggesting that they have a high impact on aging. The importance of hubs in age-related gene networks was also demonstrated by earlier studies by Promislow [23], Ferrarini et al. [24], Budovsky et al. [18] and Bell et al. [25]. The over-representation of signaling proteins was also noted by Wolfson et al. [26], who showed that a common signaling signature network of human longevity and major age-related disease genes exists, and that this includes the insulin pathway and, somewhat surprisingly, adherens junctions- and focal adhesion-related signaling.

Figure 1.

The human protein-protein interaction network of aging-associated genes. A total of 261 aging-associated genes were assembled using the GenAge Human Database [19]. Protein-protein interactions of the human interactome were collected from the 8.0 version of the STRING database [20] using physical contacts only. The network was visualized using the Cytoscape program [21]. The degree (number of neighbors) of nodes is represented by the size of the circle and the font. Note the high number of signaling pathway proteins among hubs (nodes with degrees - and therefore size - much greater than average), exemplified by the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT proteins.

Besides the subnetwork of aging-related gene protein products, a more extended network, including their neighbors and their neighbors' connections, can also be created [18,25,26]. This extended network contains the neighbors of age-related proteins, which have not been yet recognized as aging-related genes. These proteins give an excellent target set to identify further aging-related genes, as has been demonstrated by Bell et al. [25].

Changes of whole interactomes during the aging process

Xue et al. [27] went yet a step further, and examined changes in the whole fruit fly and human brain interactome during aging. They showed that age-related changes preferentially affect only a few modules (communities, groups) of the network, and aging-associated proteins are typically located between modules, providing an important element of the regulation of network functions. Molecular chaperones also have a preferential inter-modular localization. Their inter-modular position is special, since they link distant network modules with low-affinity, weak links, which stabilizes the network [10]. On the other hand, chaperones also constitute an important repair mechanism that slows down the aging process. During stress, chaperones become occupied by damaged proteins, which contributes to a larger separation of network modules [6,28]. We expect that the same mechanism occurs during the aging process. Chaperones, and presumably a large number of other proteins (in yeast this class constitutes 5% of the whole genome [29]), lose their module-connecting, stabilizing role in aging cells and organisms. The disappearing weak links destabilize the network, the modules fall apart, their regulation becomes deteriorated, and the separated modules cannot optimally fulfill their tasks. Such changes lead to increased noise and destabilization in the network, which correspond well with the typical signs of aging.

The GenAge Database [19] contains almost 300 aging-associated human genes. Most of these genes encode proteins that do not act alone, but rather as parts of many smaller or larger protein complexes. The complexity of the age-related protein-protein interactions is revealed by the cross-talk of age-related signaling pathways. As an example, the growth hormone-related pathways, the oxidative stress-induced pathway and the dietary restriction pathway all affect the FOXO (Daf-16) transcription factor [30]. Many more focal points of age-related signaling may emerge in the future. Network analysis will certainly offer great help in the identification of these key elements, which may also serve as drug targets.

Despite our enthusiasm, we must note that the network approach is only in its infancy with regard to its applications to aging research. As a result, most genes that have been predicted by network-related methods as participants in the aging process have not yet been verified experimentally. However, we may already highlight a number of novel longevity genes as neighbors of age-related proteins. Those candidates that are neighboring hubs with high centrality within the network show particular promise. Moreover, modern network-prediction methods [31] may also be able to predict links and network elements that should be a part of the network, but that have not yet been identified. These network extensions may also provide additional research targets for future age-related studies. Network-based analysis may also give a molecular-level explanation of age-related macroscopic features such as the increased unpredictability, diversity and destabilization of aged organisms, including elderly people. Such so-called 'emergent properties' of networks are features displayed by the whole network, but cannot be predicted from any single network element. Aging is characterized by a large number of such 'emergent-like' properties; an understanding of the whole cellular system is needed. Networks provide an efficient tool for accomplishing this goal.

Age-related changes in cell compartmentalization

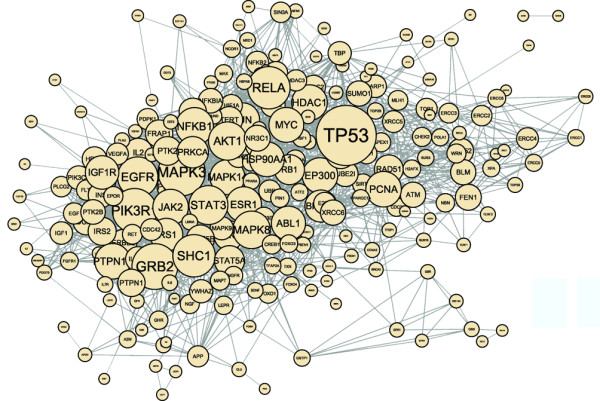

As discussed earlier, the signaling subnetwork becomes a prominent part of protein-protein interaction networks in the elucidation of the mechanisms related to aging. In this section we will consider the involvement of various cell compartments (such as the nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, plasma membrane and cytoplasm) in signaling processes. Figure 2 shows the age-related signaling network of cellular compartments, where network elements are the cellular compartments and links between two compartments represent various aging-related signaling pathways [30] involving both compartments. The major cell compartments contribute to the age-related signaling pathways to a similar extent, with the exception of the Golgi apparatus. This large spatial complexity of signaling events is in agreement with the multifactorial nature of age-related signaling. In the network representation, mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum are tightly coupled, which is in agreement with the results of cell biological studies.

Figure 2.

Age-related signaling network of cellular compartments. In this network representation, the elements of the network are the cellular compartments (PM, plasma membrane; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; MITO, mitochondria; GOLGI, the Golgi apparatus; NUCL, nucleus; PLASM, cytoplasm), while the links between them represent the age-related signaling pathways [30]. The network has been visualized using the Cytoscape program [21]. The colors represent the following pathways: orange, growth hormone pathways; green, MAP-kinase cascade; blue, dietary restriction pathway; red, reactive oxygen species.

During the aging process, the nuclear pore complexes become more permeable [9]. This key element of cellular aging not only disturbs the nuclear reassembly after mitosis and compromises nuclear integrity, exposing DNA to oxidative damage, but may also significantly disturb all nucleus-related signaling steps, including the growth hormone-, insulin TGF-β (transforming growth factor-β)-, dietary restriction-, and oxidative stress-mediated signaling pathways.

Other cellular compartments, such as mitochondria, the endoplasmic reticulum or the plasma membrane, may also become more permeable in aged cells. Indeed, an increased susceptibility of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore has been reported in aged mice [32] and in interfibrillar heart mitochondria of aged rats. The age-related reduction of Ca2+ retention capacity of interfibrillar heart mitochondria may explain the increased susceptibility to stress-induced cell death in the aged myocardium [33]. Similarly, an age-dependent decline of sarcoplasmic reticulum ultrastructure, leading to irregular Ca2+ signaling, has been reported. This structural change is related to the decreased expression of the mitsugumin-29 protein [34]. The increased fragility of the plasma membrane of senescent cells may be a result of increased exosome formation in the senescent state, as seen in normal and prostate cancer cells [35]. Increased exosome formation also accompanies the development of drusen, an extracellular deposit that represents a significant risk factor of age-dependent macular degeneration [36].

Age-related drug development

Currently, only a small number of drugs on the market directly target the aging process. Most of the available medicaments prevent skin aging, such as a kinetin-based drug that delays the effects of aging in human skin fibro-blasts [37], or an algae extract that activates the protea-some and delays the aging of human keratinocytes [38]. The skin-rejuvenating actions of several other compounds (for example, ethanolamine [39], or 4-oxo-retinol [40]) have been patented, although their mechanisms of action and biological importance have not yet been fully established. A recent study showed that rapamycin treatment started in already aged mice (at 600 days of life) extended both the median and maximal lifespan of the animals [41].

Several studies [42-44] have shown that the development of multi-target drugs might give better results than the traditional 'magic bullets' targeting a single protein. Single-target design might not always give satisfactory results, as there might be a cellular 'backup' system that replaces the functions of the inhibited target protein. The low-affinity binding of multi-target drugs increases the druggable proteome (that is, the number of proteins able to bind a drug-like, small and hydrophobic, orally administered compound with a reasonably high affinity), hence the number of potential drug targets. Multiple targeting allows lower doses, which often result in fewer side-effects and less toxicity and resistance. By using multi-target drugs we can decrease the functionality of entire protein cascades, which explains how multi-target design can produce more effective results, while not influencing drastically any components within the system.

The network approach opens several avenues for the design of a multi-target drug. One may attack hubs of the protein-protein interaction network, 'hub-links' (links connecting hubs), bridges (inter-modular links having a central position characterized by a high 'betweenness centrality') or elements in the overlaps of numerous network modules [43]. Moreover, perturbation analysis of protein-protein interaction networks may highlight those alternative target sets for multi-target drug design where the initial effects (for example, mutations or protein damage inducing an age-related disease or aging) accumulate their actions [45].

Recent studies have shown that aging is strongly linked with age-related diseases, and that these processes share a common signaling network [18,26]. Signaling hubs of the age-related protein-protein interaction subnetwork may be good candidates for age-related drug-targets, which may also help prevent or cure age-related diseases. Moreover, the extended age-related protein-protein interaction network, including the neighbors of ageing gene products, contains a large number of as-yet unknown age-related proteins that offer additional drug-target options [25,26]. The central position of key age-related proteins in the interactome raises the possibility that appropriately selected subsets may form efficient target sets for multi-target drug design, opening a way to ensure healthy aging instead of combating each age-related disease one by one.

Conclusions and perspectives

In the introduction to this review we showed that the network approach can grossly expand the aging concept from quantum systems up to the complex ecosystem of the Earth (Table 1). We are at the very beginning of both the conceptualization and study of the aging process of the internet, worldwide web, social networks, forests, trade and co-ownership networks of the economy, and so on. This network-related generalization of the aging concept will allow us to understand the aging and age-related diseases of our body from a number of entirely novel perspectives. The use of the dual concept of 'forever young' (flexible, proliferation/exploration-optimized) and 'always-old' (rigid/overspecialized, survival-optimized) networks [16] will certainly help the generalization of our biological and medical knowledge on aging of other complex systems.

Our review focuses on the role of protein-protein interaction networks (interactomes) and their subnetworks, signaling networks in aging. Hubs and inter-modular elements of both protein-protein interaction and signaling networks have proved to be of great importance in the regulation of the aging process. Looking to the future, the challenge for further studies is to enrich this list with other topologically or dynamically important network positions, such as creative network elements [46]. The thorough analysis of age-related network positions will increase the accuracy of the prediction of novel age-related genes. Signaling proteins are highly over-represented among age-related gene products, including network hubs. The age-related signaling network components can also be found among the major age-related disease genes, forming a common signaling signature.

Aging induces a rather general permeability increase of various cellular compartments, such as the nucleus, the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. However, this increase is probably not a consequence of increased membrane flexibility. On the contrary, the increased permeability (or susceptibility to increased permeability) may reflect an increased membrane rigidity causing membrane fragility. Changes in the permeability of cellular compartments certainly rearrange the actual representation of both interactomes and signaling networks. These assumptions open a number of exciting areas for further study.

All the above findings are good starting points for finding novel drug targets to help healthy aging and extend the healthy lifespan. Multi-target drugs will be especially suited to address the extreme complexity of aging. The large overlap between network components participating in the regulation of the aging process and in age-related major diseases, such as cancer, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases, makes the development of age-related multi-target drugs especially promising, since, with the help of these 'magic buckshots', we may help the prevention of many age-related diseases altogether.

Abbreviations

GHRH: growth-hormone-releasing hormone; GHRHR: growth-hormone-releasing hormone receptor; GRB2: growth factor receptor-bound protein; JAK/STAT: Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription protein signaling pathway; MAPK/ERK: mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase, 'classical' MAP kinase signaling pathway; PI3K/AKT: the phosphoinositide-3-kinase/protein kinase B signaling pathway; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GS prepared the figures, wrote a significant part of the protein-protein interaction network and drug-development sections and helped to finalize the manuscript; DG made important contributions to the introduction, Table 1 and the finalization of the manuscript; DV and TN contributed to Figure 2 and to the cell compartmentalization section; PC prepared the outline and integrated the sections.

Authors' information

All authors are members of the LINK-Group http://www.linkgroup.hu. GS and DG are completing their MSc theses, DV and TN are undergraduate research students and PC is a professor of biochemistry and network studies.

Contributor Information

Gábor I Simkó, Email: gsimko@gmail.com.

Dávid Gyurkó, Email: gyurko.david@e-arc.hu.

Dániel V Veres, Email: veresdani@msn.com.

Tibor Nánási, Email: nanasitibor@gmail.com.

Peter Csermely, Email: csermely@puskin.sote.hu.

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors' laboratory was supported by the EU (FP6-518230) and the Hungarian National Science Foundation (OTKA K69105).

References

- Kirkwood T, Austad S. Why do we age? Nature. 2000;408:233–238. doi: 10.1038/35041682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoro E, Austad S, (Eds) Handbook of the Biology of Aging. 6. San Diego: Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vasto S, Candore G, Balistreri C, Caruso M, Colonna-Romano G, Grimaldi M, Listi F, Nuzzo D, Lio D, Caruso C. Inflammatory networks in ageing, age-related diseases and longevity. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowald A, Kirkwood T. A network theory of ageing: the interactions of defective mitochondria, aberrant proteins, free radicals and scavengers in the ageing process. Mutat Res. 1996;316:209–236. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8734(96)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Valensin S, Bonafè M, Paolisso G, Yashin A, Monti D, De Benedictis G. The network and the remodeling theories of aging: historical background and new perspectives. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:879–896. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(00)00172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sõti C, Csermely P. Aging cellular networks: chaperones as major participants. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzakala F, Ricci-Tersenghi F. Aging, memory and rejuvenation: some lessons from simple models. J Phys Conf Ser. 2006;40:42–49. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/40/1/005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mauger A, Pottier N. Aging effects in the quantum dynamics of a dissipative free particle: non-ohmic case. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2002;65:056107. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.056107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo M, Raices M, Panowski S, Hetzer M. Age-dependent deterioration of nuclear pore complexes causes a loss of nuclear integrity in postmitotic cells. Cell. 2009;136:211–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csermely P. Weak Links: the Universal Key to the Stability of Networks and Complex Systems. Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Supekar S, Menon V, Rubin D, Musen M, Greicius M. Network analysis of intrinsic functional brain connectivity in Alzheimer's disease. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman R, Rebok G, Saczynski J, Kouzis A, Wilcox Doyle K, Eaton W. Social network characteristics and cognition in middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59:P278–P284. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.p278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond B, Franklin J. Aging in Pacific Northwest forests: a selection of recent research. Tree Physiol. 2002;22:73–76. doi: 10.1093/treephys/22.2-3.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra S, ReedTsochas F, Uzzi B. Asymmetric disassembly and robustness in declining networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16466–16471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804740105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki T, Sud Y. A global river network. Earth Interactions. 1998;2:1–36. doi: 10.1175/1087-3562(1998)002<0001:DOTRIP>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss HJ, Mihalik Á, Nánási T, Õry B, Spiró Z, Sõti C, Csermely P. Ageing as a price of cooperation and complexity: Self-organization of complex systems causes the ageing of constituent networks. BioEssays. 2009;31:651–664. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas E, Davie K. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Rad Biol Med. 2000;29:222–230. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budovsky A, Abramovich A, Cohen R, ChalifaCaspi V, Fraifeld V. Longevity network: construction and implications. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhaes JP, Budovsky A, Lehmann G, Costa J, Li Y, Fraifeld V, Church GM. The Human Ageing Genomic Resources: online databases and tools for biogerontologists. Aging Cell. 2009;8:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, Doerks T, Julien P, Roth A, Simonovic M, Bork P, von Mering C. STRING 8 - a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D412–D416. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killcoyne S, Carter G, Smith J, Boyle J. Cytoscape: a community-based framework for network modeling. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;563:219–239. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-175-2_12. full_text. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheu A, Maraver A, Serrano M. The Arf/p53 pathway in cancer and aging. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6031–6035. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promislow D. Protein networks, pleiotropy and the evolution of senescence. Proc Biol Sci. 2004;271:1225–1234. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarini L, Bertelli L, Feala J, McCulloch A, Paternostro G. A more efficient search strategy for aging genes based on connectivity. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:338–348. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R, Hubbard A, Chettier R, Chen D, Miller JP, Kapahi P, Tarnopolsky M, Sahasrabuhde S, Melov S, Hughes RE. A human protein interaction network shows conservation of aging processes between human and invertebrate species. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson M, Budovsky A, Tacutu R, Fraifeld V. The signaling hubs at the crossroad of longevity and age-related disease networks. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue H, Xian B, Dong D, Xia K, Zhu S, Zhang Z, Hou L, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Han JDJ. A modular network model of aging. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:147. doi: 10.1038/msb4100189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palotai R, Szalay SM, Csermely P. Chaperones as integrators of cellular networks: changes of cellular integrity in stress and diseases. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:10–15. doi: 10.1002/iub.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Siegal M. Network hubs buffer environmental variation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer E, Brunet A. Signaling networks in aging. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:407–412. doi: 10.1242/jcs.021519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauset A, Moore C, Newman ME. Hierarchical structure and the prediction of missing links in networks. Nature. 2008;453:98–101. doi: 10.1038/nature06830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Rottenberg H. Aging enhances the activation of the permeability transition pore in mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:603–608. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer T, Servais S, Seo A, Marzetti E, Hiona A, Upadhyay S, Wohlgemuth S, Leeuwenburgh C. Bioenergetics and permeability transition pore opening in heart subsarcolemmal and interfibrillar mitochondria: effects of aging and lifelong calorie restriction. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisleder N, Brotto M, Komazaki S, Pan Z, Zhao X, Nosek T, Parness J, Takeshima H, Ma J. Muscle aging is associated with compromised Ca2+ spark signaling and segregated intracellular Ca2+ release. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:639–645. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann B, Paine M, Brooks A, McCubrey J, Renegar R, Wang R, Terrian D. Senescence-associated exosome release from human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7864–7871. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, Lukas T, Yuan M, Du N, Tso M, Neufeld A. Autophagy and exosomes in the aged retinal pigment epithelium: possible relevance to drusen formation and age-related macular degeneration. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan S. N6-furfuryladenine (kinetin) as a potential anti-ageing molecule. J Anti-Aging Medicine. 2002;5:113–116. doi: 10.1089/109454502317629336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bulteau A, Moreau M, Saunois A, Nizard C, Friguet B. Algae extract-mediated stimulation and protection of proteasome activity within human keratinocytes exposed to UVA and UVB irradiation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:136–143. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manissier P, Morelli M, Le Fur A, Buronfosse A, Seigneurin A. Stable compositions containing ethanolamine derivatives and glucosides. Patent application WO/2003/028691. 2001.

- Gudas L, Achkar C, Buck J, Langston A, Derguini F, Nakanishi K. Regulating gene expression using retinoids with CH2 or related groups at the side chain terminal position. Patent application WO/1996/021438. 1996.

- Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter CS, Pahor M, Javors MA, Fernandez E, Miller RA. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csermely P, Ágoston V, Pongor S. The efficiency of multi-target drugs: the network approach might help drug design. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korcsmáros T, Szalay MS, Böde C, Kovács IA, Csermely P. How to design multi-target drugs: target search options in cellular networks. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2007;2:1–10. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann GR, Lehár J, Keith CT. Multi-target therapeutics: when the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antal M, Böde C, Csermely P. Perturbation waves in proteins and protein networks: applications of percolation and game theories in signaling and drug design. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2009;10:161–172. doi: 10.2174/138920309787847617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csermely P. Creative elements: network-based predictions of active centres in proteins, cellular and social networks. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]