Abstract

Objectives To study the analgesic effect of acupuncture and placebo acupuncture and to explore whether the type of the placebo acupuncture is associated with the estimated effect of acupuncture.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of three armed randomised clinical trials.

Data sources Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase, Biological Abstracts, and PsycLIT.

Data extraction and analysis Standardised mean differences from each trial were used to estimate the effect of acupuncture and placebo acupuncture. The different types of placebo acupuncture were ranked from 1 to 5 according to assessment of the possibility of a physiological effect, and this ranking was meta-regressed with the effect of acupuncture.

Data synthesis Thirteen trials (3025 patients) involving a variety of pain conditions were eligible. The allocation of patients was adequately concealed in eight trials. The clinicians managing the acupuncture and placebo acupuncture treatments were not blinded in any of the trials. One clearly outlying trial (70 patients) was excluded. A small difference was found between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture: standardised mean difference −0.17 (95% confidence interval −0.26 to −0.08), corresponding to 4 mm (2 mm to 6 mm) on a 100 mm visual analogue scale. No statistically significant heterogeneity was present (P=0.10, I2=36%). A moderate difference was found between placebo acupuncture and no acupuncture: standardised mean difference −0.42 (−0.60 to −0.23). However, considerable heterogeneity (P<0.001, I2=66%) was also found, as large trials reported both small and large effects of placebo. No association was detected between the type of placebo acupuncture and the effect of acupuncture (P=0.60).

Conclusions A small analgesic effect of acupuncture was found, which seems to lack clinical relevance and cannot be clearly distinguished from bias. Whether needling at acupuncture points, or at any site, reduces pain independently of the psychological impact of the treatment ritual is unclear.

Introduction

Acupuncture is commonly used for the treatment of pain. In traditional Chinese medicine the concepts of “meridian” and the vital energy “Qi” form part of the theoretical basis for needling at specific acupuncture points.1 2 Studies indicate that penetration of a needle through the skin, whether at an acupuncture point or not, has physiological effects.3 4 5 The “gate control theory” and the release of endogenous opioids have been suggested as explanations for the apparent analgesic effect of acupuncture.6 7 8

In 2005 two large, high quality trials in patients with headache found little difference between the effects of acupuncture and placebo acupuncture but a substantial difference between placebo acupuncture and no acupuncture.w1 w2 This result differed from that of a large systematic review comparing all placebo interventions with no treatment that found only a small to moderate analgesic effect of placebo, which could not be clearly distinguished from reporting bias owing to the inevitable lack of blinding of the no treatment groups.9 10 We therefore wanted to analyse all trials of acupuncture for pain that had two control groups consisting of placebo acupuncture and no acupuncture. Our objectives were to study the analgesic effect of acupuncture and placebo acupuncture and to explore whether the type of placebo acupuncture is associated with the estimated effect of acupuncture.

Methods

We systematically reviewed clinical trials of acupuncture treatment for pain that randomised patients to acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, or no acupuncture.

Search strategy

The literature searches were very comprehensive and have been described in the Cochrane review of the effect of placebo interventions.11 We searched the Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase, Biological Abstracts, and PsycLIT. The last search included all trials published before 1 January 2008.

Inclusion criteria

We included all trials that labelled the intervention “acupuncture”—for example, traditional acupuncture and electro-acupuncture. We excluded trials that used transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and manual acupressure.

No clear definition of placebo acupuncture exists, so we accepted the placebo interventions used by the authors of the trial reports, such as insertion of needles into non-acupuncture points or use of non-penetrating needles. We excluded trials in which the no acupuncture group received an intended basic care that differed from that provided to the acupuncture and placebo acupuncture groups—for example, if an educational programme was part of the intended basic care in the no acupuncture group but not in the other groups.

We included trials if the pain had been estimated by the patients (self reported pain) on a visual analogue scale or another ranking scale. When several pain scales had been used, they were presented to two of the authors (AH and PCG) who, blinded for the results, chose the most relevant one, preferably a visual analogue scale as this is the most commonly used scale in pain studies. When pain had been assessed at several time points we chose the first time point after the end of treatment. All authors evaluated the eligibility of the trials, resolving disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction

One author (MVM) extracted data, and the other authors checked them. We noted the type of clinical problem that caused the pain, type of pain scales, number of patients, duration of treatment, number of sessions, and nature of any concomitant treatment. We described in detail the type of acupuncture and type of placebo intervention in each trial. We noted the average pain after the end of treatment, and the standard deviation, or used changes from baseline if such data were not available.

Assessment of risk of bias

One author (AH) assessed risk of bias in the trials, and another author (PCG) checked it. We noted whether the allocation of patients in each trial was adequately concealed, whether patients had been described as blinded (or masked), and whether dropout was below 15%. We considered such trials to have low risk of bias. We assessed small sample size bias with funnel plots.12

Data analysis

For each trial, we calculated the standardised mean difference, which is the difference between the means divided by the pooled standard deviation. In three cases in which standard deviations were not available and could not be derived for a particular trial,w3-w5 we estimated the standard deviation on the basis of the values in the other trials. We calculated the standard deviation/mean for these trials, selected the median value, and multiplied it with the mean from the trial with a missing standard deviation.

In two cases in which more than one acupuncture group was used,w3 w6 such as high frequency and low frequency acupuncture treatment, we combined the results from both groups into a weighted mean and a pooled variance.13 After our initial data extraction we became aware that for one trial we had chosen a scale that primarily measured quality of pain (Schmerzempfindungsskala) and not intensity of pain. w7 Therefore, we used data from the only other eligible scale, the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities pain subscale.

We pooled the standardised mean differences from the trials by using meta-analysis, comparing the effect of acupuncture with that of placebo acupuncture and the effect of placebo acupuncture with that of no acupuncture.

In a pre-planned sensitivity analysis, we used the authors’ primary outcome.14 In unplanned sensitivity analyses, we also studied the impact of the methodological quality of the trials and of the type of acupuncture. We assumed that trials with clearly concealed allocation, explicit blinding of patients, and a dropout rate below 15% had lower risk of bias than other trials.9 10 13We also assumed that trials in which experienced acupuncturists were allowed to use individually chosen acupuncture points (in addition to several fixed points) could differ in effect from other trials.

We furthermore studied whether the difference between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture was related to the type of placebo, by using meta-regression. For this purpose, one author (PCG), blinded to the results, evaluated the placebo interventions on a ranking scale from 1 to 5, where 1 represented a placebo treatment that most likely could produce physiological effects and 5 represented the opposite. For this evaluation, we considered point of insertion, needle size, depth of insertion, penetration of the skin, achievement of Qi, and manual stimulation. Another author (AH) checked this evaluation. Finally, we did a supplementary subgroup analysis in which we compared the effect of acupuncture on the basis of whether or not the placebo acupuncture penetrated the skin.

We used Review Manager 5 and Stata 8.2 for final analyses. We used a random effects model if heterogeneity existed (P<0.10) and a fixed effect model otherwise.

Results

The search included 234 trials eligible for our updated Cochrane review (in progress) of all types of placebo interventions.9 10 From this sample we identified 20 potentially eligible trials for this review. We excluded seven trials—six because they studied transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and one because the intervention was manual acupressure. We included 13 trials of acupuncture for pain (3025 patients) (table 1).w1-w13

Table 1.

Characteristics of trials

| Trial | Clinical problem | Trial size—No randomised (No; % dropouts) | Blinding | Concealment of allocation | Pain scale | Treatment duration (No of sessions)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melchartw1 | Tension headache | 270 (30; 11%) | Patients | Centralised telephone randomisation | Rating scale (1-10) | 8 weeks (12); evaluation at 12 weeks |

| Lindew2 | Migraine | 302 (20; 7%) | Patients | Centralised telephone randomisation | Rating scale (0-10) | 8 weeks (12); evaluation at 12 weeks |

| Scharfw8 | Osteoarthritis | 1039 (57; 5%) | Patients | Central randomisation | WOMAC (0-10) | 6 weeks (10); evaluation at 13 weeks |

| Wittw7 | Osteoarthritis | 300 (14; 5%;) | Patients | Centralised telephone randomisation | WOMAC (0-10) | 8 weeks (12) |

| Fosterw9 | Osteoarthritis | 352 (19; 5%) | Patients | Central telephone randomisation | WOMAC (0-10) | 3 weeks† (6); evaluation at 6 weeks |

| Brinkhausw11 | Low back pain | 301 (17; 6%) | Patients | Centralised telephone randomisation | VAS (0-100 mm) | 8 weeks (12) |

| Molsbergerw10 | Low back pain | 186 (12; 6%) | Patients | Central telephone randomisation | VAS (0-100 mm) | 4 weeks (12) |

| Leibingw12 | Low back pain | 150 (36; 24%) | Patients | Unclear | VAS change (0-10 cm) | 12 weeks (20) |

| Wangw6 | Postoperative pain | 101 (unclear) | Patients | Unclear | VAS (0-100 mm) | 1 day (1) |

| Linw3 | Postoperative pain | 100 (unclear) | Patients | Unclear | VAS (0-100 mm) | 1 day (1) |

| Fantiw5 | Colonoscopy | 30 (unclear) | Unclear | Unclear | Rating scale (1-5) | 1 day (1) |

| Sprottw4 | Fibromyalgia | 30 (unclear) | Unclear | Unclear | VAS (0-10) | 3 weeks (6) |

| Kotaniw13 | Scar pain | 70 (unclear) | Unclear | Sequentially sealed opaque envelopes | VAS (0-10 cm) | 4 weeks (20) |

VAS=visual analogue scale; WOMAC=Western Ontario and McMaster Universities pain subscale.

*Timing of evaluation is identical to treatment duration if not otherwise specified.

†Acupuncture and placebo acupuncture groups received three weeks of needling during six week standard care programme.

The clinical conditions were knee osteoarthritis,w7-w9 tension type headache,w1 migraine,w2 low back pain,w10-w12 fibromyalgia,w4 abdominal scar pain,w13 postoperative pain,w3 w6 and procedural pain during colonoscopy.w5 The duration of treatment varied from one day to 12 weeks (table 1).

Eight trials had clearly concealed the allocation of patients.w1 w2 w7-w11 w13 No trials reported blinding of the clinicians managing the acupuncture and placebo acupuncture treatments, whereas blinding of the patients was explicitly reported in 10 trials.w1-w3 w6-w12 In five trials the acupuncture treatment involved multiple sessions with experienced acupuncturists who could choose additional acupuncture points at their discretion.w1 w2 w4 w7 w11

Table 2 describes the placebo treatments. In two trials the placebo procedures consisted of non-penetrative needling.w4 w9 In 11 trials the placebo procedure penetrated the skin: seven trials used superficial needling at non-acupuncture points with fine needles, avoiding Qi and manual stimulation, and four trials used other forms of penetrative needling.w3 w5 w6 w13

Table 2.

Type of interventions

| Trial | No acupuncture (standard care only) | Acupuncture + standard care | Placebo acupuncture + standard care | Potential differences in concomitant therapies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melchartw1 | Treatment of acute headaches as needed following current guidelines | Needling at “basic” points bilaterally; additional points chosen individually; achievement of “Qi” and manual stimulation at least once per session | Superficial needling at non-acupuncture points using fine needles; avoided Qi and manual stimulation | No acupuncture group had more days with analgesic drugs than acupuncture group (P<0.001); no difference between other groups (P=0.12) |

| Scharfw8 | 10 clinical visits; oral NSAID; up to six physiotherapy sessions | Local acupuncture points, according to theory of Bi syndrome, as obligatory points; additionally, 2 of 16 defined acupuncture points could be chosen | Superficial needling at non-acupuncture points; depth up to 0.5 cm without Qi; no stimulation; same type of needles used | No acupuncture group had more visits to physiotherapy and more use of analgesics than acupuncture and placebo acupuncture groups; no statistical significance of data reported |

| Lindew2 | Treatment of acute headaches as needed following current guidelines | Bilateral needle insertion in basic points; additional points chosen individually according to patients’ symptoms; achievement of Qi and manual stimulation at least once per session | Superficial needling at non-acupuncture points; fine needles used; Qi and manual stimulation avoided | No acupuncture group had more use of analgesics than acupuncture group (P<0.01); no difference between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture groups (P=0.65) |

| Brinkhausw11 | NSAID if required | Local and distant points bilaterally; additional points chosen individually; achievement of Qi and manual stimulation at least once per session | Superficial needling (needles 20-40 mm) on non-acupuncture points; fine needles used; Qi and manual stimulation avoided | Both placebo acupuncture (P=0.009) and no acupuncture groups (P<0.001) had more time on analgesics than acupuncture group |

| Wittw7 | NSAID if required | Local and distant points; additional points could be chosen; achievement of Qi and manual stimulation at least once per session | Superficial needling at non-acupuncture points; fine needles used; manual stimulation and Qi avoided | No statistically significant difference in days with drugs between the three groups |

| Fosterw9 | Advice and exercise by physiotherapist; fixed dose NSAID | 6-10 points from 16 local and distal points; manipulations to achieve Qi | Non-penetrative needling; no attempt to achieve Qi | No difference in use of analgesic drugs or visits to general practitioner |

| Molsbergerw10 | Oral NSAID, back school, physiotherapy, physical exercise, mud packs, and infrared therapy | Standard points in the lumbar region and distal points; mild to strong manipulation depending on pain; achievement of Qi | Superficial (depth <1 cm) needling at non-acupuncture points; apparently Qi and manipulation avoided | No acupuncture group had least use of analgesics; no statistical significance reported |

| Leibingw12 | Continuation of existing drugs; no new drugs; 26 sessions of physiotherapy | Body acupuncture and ear acupuncture, 10-30 mm; achievement of Qi and manual stimulation. | Superficial needling at non-acupuncture points; needles not stimulated (no Qi) | Differences in use of concomitant treatment not reported |

| Sprottw4 | Paracetamol, exercise, heating, cooling, and electrotherapy | Acupuncture points needled according to patient’s symptoms | Turned off “Laser Sonde” held over symptom points; no mechanical pressure | Differences in use of concomitant treatment not reported |

| Fantiw5 | Intravenous midazolam boluses on demand, and one dose before colonoscopy | Bilateral needling at acupuncture points considered relevant for both sedation and abdominal distension; electrical stimulation | Needling at non-acupuncture points with electrical stimulation | No acupuncture group had more additional midazolam boluses than acupuncture group and placebo acupuncture group (P=0.01) |

| Linw3 | One dose of intramuscular pethidine; intravenous morphine on demand | Bilateral needling at points Zusanli; after achievement of Qi electrical stimulation | Needling at acupuncture points but without current; indicator light on | No acupuncture group had more morphine delivered than other groups (P<0.05) |

| Kotaniw13 | Infiltration of local anaesthetics; oral NSAID before and after treatment | Needling at painful points; needles kept in place for 24 hours | Needling at non-painful points | No acupuncture

group had greater consumption of analgesics than acupuncture group

(P<0.001); 30% of no acupuncture patients

found infiltration of local anaesthetics painful |

| Wangw6 | Intravenous hydromorphine on demand; preoperative midazolam | Cutaneous electrodes placed at Hegu point, on hand, and on either side of incision; electrical alternating stimulation | Needling at acupuncture points but no electrical stimulation; indicator lights on | No acupuncture group had more hydromorphine delivered than acupuncture group (P<0.05) |

NSAID=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

In all trials, all patients were provided with standard care. This concomitant treatment, also given to the no acupuncture group, typically consisted of analgesics (n=13) and physiotherapy (n=5). In general, the patients in the no acupuncture groups used more concomitant treatment than did the patients in the placebo acupuncture and acupuncture groups, with no clear difference between the last mentioned groups (table 2).

Acupuncture versus placebo acupuncture

Substantial heterogeneity was present in the comparison between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture (P<0.001, I2=66%). A trial by Kotani et al was a clear outlier—standardised mean difference −1.66 (95% confidence interval −2.34 to −0.98).w13 This trial, done in Japan, included 70 patients (2% of our sample), involved an unusual procedure of needling in painful scars, and whether the patients in the placebo acupuncture and the acupuncture groups were blinded was unclear; one third of the patients in the untreated group complained of pain caused by repeated injections of local anaesthetics. We excluded this trial from all further analyses, after which the heterogeneity was substantially reduced (P=0.10, I2=36%).

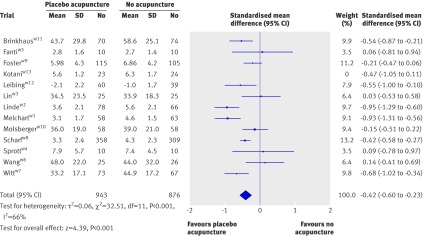

We found a statistically significant difference between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture (P<0.001)—pooled standardised mean difference −0.17 (−0.26 to −0.08) (fig 1). On visual inspection, the funnel plot was symmetrical with a clear peak (data not shown).

Fig 1 Meta-analysis of acupuncture versus placebo acupuncture

Placebo acupuncture versus no acupuncture

Substantial heterogeneity existed in the comparison between placebo acupuncture and no acupuncture (P<0.001, I2=66%) (fig 2). We found a statistically significant difference between placebo acupuncture and no acupuncture (P<0.001)—pooled standardised mean difference −0.42 (−0.60 to −0.23). On visual inspection, the funnel plot had a broad peak, as large trials reported both small and large effects of placebo; furthermore, small trials tended to report small effects (data not shown).

Fig 2 Meta-analysis of placebo acupuncture versus no acupuncture

Secondary analyses

In two trials,w3 w4 we could not define the authors’ primary outcome, so the sensitivity analysis included 10 trials. In two trials,w5 w12 our chosen outcome was the same as that of the authors (table 1). Substantial heterogeneity existed in the comparison between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture (P<0.001, I2=73%). The pooled standardised mean difference was −0.26 (−0.46 to −0.07) (P< 0.001). For the comparison of placebo acupuncture with no acupuncture, substantial heterogeneity was also present (P<0.001, I2=59%). The pooled standardised mean difference was −0.48 (−0.65 to −0.30) (P=0.009).

When we restricted the analysis to the seven trials with clearly concealed allocation, explicit blinding of patients, and dropout rate less than 15%, substantial heterogeneity existed in the comparison between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture (P=0.01, I2=63%). The pooled standardised mean difference was −0.19 (−0.35 to −0.02) (P=0.03). Heterogeneity was also present in the similar comparison between placebo acupuncture and no acupuncture (P=0.001, I2=72%). The pooled standardised mean difference was −0.54 (−0.75 to −0.33) (P<0.001).

When we restricted the analysis to the five trials that involved multiple sessions of acupuncture treatment with experienced acupuncturists who could choose additional acupuncture points at their discretion, we also found heterogeneity in the comparison between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture (P=0.07, I2=53%). The pooled standardised mean difference was −0.23 (−0.45 to −0.01) (P=0.04). Heterogeneity also existed in the similar comparison between placebo acupuncture and no acupuncture (P=0.09, I2=49%). The pooled standardised mean difference was −0.71 (−0.96 to −0.45) (P<0.001).

Type of placebo acupuncture

We ranked the various placebo acupuncture interventions on a 1-5 scale, where 1 represents a placebo treatment that was most likely to produce physiological effects. We ranked needling at acupuncture points without electrical stimulation but indicator lights on as 1w3 w6; needling at non-acupuncture points with electrical stimulation as 2w5; superficial needling at non-acupuncture points (20-50 mm) avoiding Qi and manual stimulation as 3w1 w2 w7 w8 w10-w12; non-penetrating needle as 4w9; and laser turned off, held over the symptomatic points without using any mechanical pressure as 5.w4

A meta-regression of the 12 trials found no statistically significant relation between the type of placebo intervention and the effect of acupuncture (P=0.60). Supplementary subgroup analyses found a statistically significant difference in effect of acupuncture between the two trials using non-penetrative placebo needles (pooled standardised mean difference 0.07, −0.18 to 0.32) and the 10 trials using penetrative placebo needles (pooled standardised mean difference −0.21, −0.30 to −0.11) (P=0.04). Thus, contrary to what would be expected, the tendency was for larger effects of acupuncture when the comparative placebo procedure was penetrative.

Discussion

We found a small difference between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture and a moderate difference between placebo acupuncture and no acupuncture. The effect of placebo acupuncture varied considerably.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our review is the first that identifies and analyses three armed trials of acupuncture for pain, thus providing an estimate of the general analgesic effect of acupuncture and its direct comparison with the analgesic effect of placebo acupuncture. The review is fairly large, includes several trials of high methodological quality, and covers a broad range of common painful conditions. Furthermore, our main results were similar to those found in the subgroups of trials with low risk of bias, in trials using multiple sessions of experienced acupuncturists choosing acupuncture points at their discretion, and when we analysed the primary outcomes of the trials (instead of the outcome we had chosen).

All included trials provided various types of standard care to the patients, and we excluded trials with different intended standard care for the no acupuncture group compared with the acupuncture and placebo acupuncture groups.15 16 17 Thus, our findings are limited to the additive effect of acupuncture and placebo acupuncture. The standard care was unlikely to have resulted in a “ceiling effect” preventing the detection of any beneficial effect of acupuncture, because we found an effect of placebo acupuncture beyond that of standard care.

Our meta-regression analysis found no association between type of placebo and effect of acupuncture. We did find a greater effect of acupuncture in the 10 trials with penetrative placebo needles compared with the only two trials that used non-penetrative placebo needles (P=0.04). This is contrary to what one would have expected, and we regard it as a chance finding. We note that our meta-regression was based on a subjective ranking of the possibility of a physiological effect of placebo, and that both the subgroup analysis and the meta-regression are observational in nature. However, our findings are similar to that of a randomised trial reporting no difference in analgesic effect between three types of placebo acupuncture: acupuncture considered specific for another disease, needle insertion at non-acupuncture points, and non-penetrative simulated acupuncture.18

We found a tendency for an increase in the use of analgesic drugs in the no acupuncture groups compared with the placebo and acupuncture groups, which would tend to underestimate the effect of placebo acupuncture. We found no tendency for any difference in use of concomitant treatment between the placebo groups and the acupuncture groups.

Our sensitivity analyses of the authors’ primary outcomes found slightly larger effects of acupuncture and placebo, as well as more heterogeneous results. However, the trials had very dissimilar primary outcomes (such as days with headache and number of analgesic doses) and primary outcomes in clinical trials are often changed retrospectively.14 We excluded one trial as a clear outlier, but the proportion of excluded patients was small and had little effect on our effect estimates.

Other studies

Our finding of limited, at best, analgesic effects of acupuncture corresponds with the seven Cochrane reviews on acupuncture for various types of pain, which all concluded that no clear evidence existed of an analgesic effect of acupuncture.19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Most stressed the methodological shortcomings of the included trials.

Our finding of a moderate difference between placebo acupuncture and no acupuncture (standardised mean difference −0.42) agrees fairly well with our previous review of the effect of placebo in general.9 10 Although we previously found an overall difference in standardised mean difference of −0.25 for pain, we also saw a tendency for larger effects when the placebo intervention was procedural—for example, a sham acupuncture needle (standardised mean difference −0.33)—and not merely a placebo tablet (standardised mean difference −0.20).

Meaning of our review

Interpreting a standardised mean difference clinically may be challenging. On the basis of the mean standard deviation from the trials that had used visual analogue scales, the effect of acupuncture (standardised mean difference −0.17, −0.26 to −0.07) corresponds to a reduction of 4 (2 to 6) mm on a 100 mm scale. The effect of placebo acupuncture (standardised mean difference −0.42 (−0.60 to −0.23), corresponds to a reduction of 10 (6 to 15) mm.

Attempts at defining a clinically minimal pain improvement have reached quite different conclusions and have often reported percentage improvement and not an absolute effect size as we have.26 27 However, a consensus report characterised a 10 mm reduction on a 100 mm visual analogue scale as representing a “minimal” change or “little change.”27 Thus, the apparent analgesic effect of acupuncture seems to be below a clinically relevant pain improvement.

Our pooled effect of placebo acupuncture (standardised mean difference −0.42) is based on trials with effects that vary much more than is expected by chance. Some of the large trials report an effect of placebo acupuncture that is of clear clinical relevance—for example, standardised mean difference −0.95,w2 corresponding to 24 mm on a 100 mm visual analogue scale—whereas others find effects that seem to be of limited clinical relevance—for example, standardised mean difference −0.21,w9 corresponding to 5 mm.

Considerable heterogeneity existed (I2=66%) when we compared placebo acupuncture with no acupuncture but not when we compared acupuncture with placebo acupuncture (I2=36%), although both analyses were based on the same trials and the same outcomes and approximately one third of the patients were identical (those in the placebo groups). Thus, more variation seems to occur in the no acupuncture groups than in the acupuncture groups.

Lack of blinding is inherent in the no acupuncture groups.28 Variations in reporting bias, in use of concomitant treatment, and in the interaction between the patient and the care provider could explain some of the observed variation in the effect of placebo. Insufficient blinding is also a problem for the comparison between acupuncture and placebo acupuncture. In all trials, the acupuncturist knew what constituted true acupuncture and sham acupuncture. Furthermore, in some trials, a noticeable difference existed between the acupuncture and the placebo acupuncture, in most cases because the placebo acupuncture did not involve manual stimulation and attempts to induce Qi. Close interaction between patient and therapist is typical for acupuncture and will often involve suggestive components. For example, when patients are asked whether they feel Qi a high proportion of patients will say yes, even when they have been treated with a non-penetrating placebo acupuncture needle.29 The incomplete blinding of the patients, and the interaction between the fully unblinded acupuncturist and the patients, could explain part of—or perhaps all of—the observed small effect.

Unanswered questions and future research

Our findings question both the traditional foundation of acupuncture, which is based on the existence of meridians and Qi sensations, and the prevailing hypothesis that acupuncture has an important effect on pain in general. If this hypothesis is wrong, and our results point to that, then acupuncture would seem to be unlikely to have an effect on pain related only to certain conditions, but further studies may examine this question.

In some situations placebo acupuncture is associated with large analgesic effects, but in other situations similar procedures cause no, or only small, effects. Thus, to regard placebo acupuncture as a universally effective “super placebo” would be inappropriate. Important heterogeneity remains unexplained and calls for further studies on the underlying mechanisms of the effects of placebo acupuncture and placebo in general.

We suggest that future trials on acupuncture for pain focus on two strategies. Firstly, researchers could try to reduce bias by ensuring blinding when possible. For example, blinding of the healthcare provider can be achieved by having the needling done by acupuncture naïve clinicians blinded to the hypothesis of the trial. Secondly, researchers could try to separate the effects involved: the physiological effect of needling at acupuncture sites or at other sites and the psychological effect of the treatment ritual or of the patient-provider interaction more broadly.30

Conclusion

We found a small analgesic effect of acupuncture that seems to lack clinical relevance and cannot be clearly distinguished from bias. Whether needling at acupuncture points, or at any site, reduces pain independently of the psychological impact of the treatment ritual is unclear.

What is already known on this topic

Acupuncture is commonly used for the treatment of pain

Acupuncture involves close patient-provider interaction with suggestive components

Blinding patients and especially treatment providers in acupuncture trials is a challenge

What this study adds

The analgesic effect of acupuncture is small and cannot be distinguished from bias resulting from incomplete blinding

The analgesic effect of placebo acupuncture is moderate but very variable as some large trials report substantial effects

The effect of acupuncture seems to be unrelated to the type of placebo acupuncture used as control

Contributors: AH and PCG had the idea for the study. PCG did the first data analyses, and AH did the final analyses. MVM wrote the first draft of the protocol and the paper. AH wrote the final draft of the paper and did the literature searches. All authors contributed to extracting and interpreting data and to revising the protocol and manuscript. AH and PCG are the guarantors.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:a3115

References

- 1.Vickers A, Zollman C. ABC of complementary medicine acupuncture. BMJ 1999;319:973-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaptchuk TJ. The web that has no weaver: understanding Chinese medicine. New York: Contemporary Books, 2000.

- 3.Irnich D, Beyer A. Neurobiological mechanisms of acupuncture analgesia. Schmerz 2002;16:93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghia JM, Mao W, Toomey TC, Gregg JM. Acupuncture and chronic pain mechanisms. Pain 1976;2:285-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewit K. The needle effect in the relief of myofascial pain. Pain 1979;6:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 1965;150:171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melzack R. Acupuncture and pain mechanisms. Anaesthesist 1976;25:204-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han JS. Acupuncture and endorphins: mini review. Neurosci Lett 2004;361:258-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no-treatment. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1594-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Is the placebo powerless? Update of a systematic review with 52 new randomised trials comparing placebo with no-treatment. J Intern Med 2004;256:91-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(2):CD003974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. (available from www.cochrane-handbook.org/).

- 14.Chan AW, Hróbjartsson A, Haahr MT, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG. Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA 2004;291:2457-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berman BM, Lao L, Langenberg P, Lee WL, Gilpin AM, Hochberg MC. Effectiveness of acupuncture as adjunctive therapy in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:901-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diener HC, Kronfeld K, Boewing G, Lungenhausen M, Maier C, Molsberger A, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of migraine: a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haake M, Müller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, Basler HD, Schäfer H, Maier C, et al. German acupuncture trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1892-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assefi NP, Sherman KJ, Jacobsen C, Goldberg J, Smith WR, Buchwald D. A randomized clinical trial of acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture in fibromyalgia. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:10-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC, Tsukayama H, Lao L, Koes BW, et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD001351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casimiro L, Barnsley L, Brosseau L, Milne S, Robinson VA, Tugwell P, et al. Acupuncture and electroacupuncture for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD003788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melchart D, Linde K, Berman B, White A, Vickers A, Allais G, et al. Acupuncture for idiopathic headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(1):CD001218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green S, Buchbinder R, Barnsley L, Hall S, White M, Smidt N, et al. Acupuncture for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(1):CD003527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trinh KV, Graham N, Gross AR, Goldsmith CH, Wang E, Cameron ID, et al. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD004870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green S, Buchbinder R, Hetrick S. Acupuncture for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(2):CD005319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proctor ML, Smith CA, Farquhar CM, Stones RW. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(1):CD002123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ten Klooster PM, Drossaers-Bakker KW, Taal E, van de Laar MA. Patient-perceived satisfactory improvement (PPSI): interpreting meaningful change in pain from the patient’s perspective. Pain 2006;121:151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hróbjartsson A. What are the main methodological problems in the estimation of placebo effects? J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streitberger K, Kleinhenz J. Introducing a placebo needle into acupuncture research. Lancet 1998;352:364-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, Davis RB, Kerr CE, Jacobson EE, et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 2008;336:999-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]