Abstract

Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is a potent hormone that stimulates growth and differentiation and inhibits apoptosis in numerous tissues. Preliminary evidence suggests that IGF-I exerts differentiating, mitogenic and restoring activities in the immune system but the sites of synthesis of local IGF-I are unknown. Identification of these sites would allow the functional role of local IGF-I to be clarified. The presence of IGF-I in non-immune cells suggests that it acts as a trophic factor, while its occurrence in subtypes of lymphocytes or antigen-presenting cells indicates paracrine/autocrine direct regulatory involvement of IGF-I in the human immune response. The present study investigated the location of IGF-I messenger RNA and protein on archival human lymph node samples by in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry and double immunofluorescence staining using an IGF-I probe and antisera specific for human IGF-I and CD3 (T lymphocytes), CD20 (B lymphocytes), CD68 (macrophages), CD21 (follicular dendritic cells), S100 (interdigitating dendritic cells) and podoplanin (fibroblastic reticular cells). Numerous cells within the B- and T-cell compartments expressed the IGF-I gene, and the majority of these cells were identified as macrophages. Solitary follicular dendritic cells exhibited IGF-I. A few T lymphocytes, and no B lymphocytes, contained IGF-I immunoreactive material. Furthermore, IGF-I immunoreactive cells outside the follicles that did not react with CD3, CD20, S100 or podoplanin markers were identified as high-endothelial venule (HEV) cells. From this we conclude that the main task of IGF-I in human non-tumoral lymph node may be autocrine and paracrine regulation of the differentiation, stimulation and survival of lymphocytes, antigen-presenting cells and macrophages and the differentiation and maintenance of HEV cells.

Keywords: B-cell, dendritic cell, fibroblastic reticular cell, human, macrophage, T-cell

Introduction

Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is a potent hormone that stimulates growth and differentiation and inhibits apoptosis. IGF-I is mainly produced in human liver, with growth hormone (GH) from the anterior pituitary as the major stimulus for the synthesis of liver IGF-I and its release into the circulation. There is general agreement that the amount of serum IGF-I influences GH release from the anterior pituitary via a negative-feedback mechanism by selective and specific inhibition of GH gene transcription and secretion.1–4 Generally, this system is termed the GH/IGF-I axis. However, IGF-I is not only expressed in liver but also in parenchymal cells of extrahepatic sites, such as cartilage,5 pancreas,6 testis7 and ovary,8 brain9 and pituitary,10 leading to the idea that IGF-I also exerts effects via local autocrine and paracrine actions.1,4

A role for GH in the regulation of the immune system was first suggested in 1930 when hypophysectomy led to thymus atrophy in rat. Thereafter, experience from Snell dwarf mice, which carry defects in GH, prolactin, thyroid hormones and IGF-I production, and from GH-deficient humans, led to the hypothesis that the whole GH/IGF-I axis may be involved (reviewed previously).11,12 Since then, numerous indications have been found that IGF-I plays a role in the proliferation and differentiation of lymphatic cells and tissues (reviewed previously1,12–17). For instance, in human T-lymphoblast cell lines the stimulatory action of GH on colony formation was attributed to a local production of IGF-I.18 This assumption has been supported by the retarded growth of T-acute lymphoblastic leukemic (ALL) cell lines by antibodies against IGF-I and the type 1 IGF-receptor (IGF-1R).19 Furthermore, reduced natural killer (NK) cell activity in GH-deficient patients has been attributed to low serum IGF-I levels as a result of the fact that IGF-I modulates NK cell activity.20 Vice versa, atrophied thymus in diabetic rats was repopulated by IGF-I,21 and GH treatment enhanced thymic volume and function, especially the percentage of CD4+ T cells and the CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratio, in human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)-infected adults, in parallel with the increased level of IGF-I in serum.22

Nevertheless, although manifold differentiating and mitogenic activities have been postulated for IGF-I in haematopoetic and lymphatic tissues, the distinct sites of IGF-I production in human immune tissues have not yet been identified. So far, IGF-I immunoreactivity has been observed in rat lymphopoetic, haematopoetic and myelopoetic bone marrow cells.23 Moreover, dispersed stromal cells and thymic epithelial cells have been proposed as local sources for IGF-I in the immune system,24–26 and recently, both IGF-I messenger RNA (mRNA) and immunoreactivity were detected in numerous non-tumoral cells of a lymph node biopsy, but the cell types expressing IGF-I were not identified.27

Knowledge of the sites of production of IGF-I would help us to establish the functional role of local IGF-I, but its localization in human lymph node is still unknown. As the exact localization of IGF-I creates a basis for understanding the impact of local IGF-I on lymph node function, the present study aimed to identify the cellular sites of IGF-I in human lymph node. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry were used to detect IGF-I mRNA and protein. In order to characterize the IGF-I immunoreactive cells, double immunofluorescence was used for IGF-I and specific immune markers: CD3 for T lymphocytes; CD20 for B lymphocytes; CD68 for histiocytic cells with phagocytic differentiation termed macrophages, in contrast to professional antigen-presenting dendritic cells, namely follicular dendritic cells (identified by CD21 surface marker) and interdigitating dendritic cells (identified by S100 protein immunoreactivity). Finally, fibroblastic reticular cells were detected by their immunoreactivity for podoplanin.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry were performed on routinely processed archival paraffin-embedded tissue specimens of non-tumoral lymph nodes. Sections were cut at 4 μm thickness, mounted onto glass slides and air-dried overnight at 42°. For further procedures, sections were dewaxed and rehydrated in descending series of ethanol. All lymph nodes were histologically investigated using conventional staining procedures and were free of malignant tumour cells. Lymph nodes showed no relevant signs of inflammation (in particular neither pronounced follicular hyperplasia nor variegated hyperplasia of the pulp) and no epitheloid cell reaction.

In situhybridization

Tissue specimens were subjected to in situ hybridization, as recently described.10,27 In brief, sections were postfixed with buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and 0·1% glutaraldehyde (GA) and pretreated by digestion at 37° with 0·02% proteinase K in 20 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·4, containing 2 mm CaCl2; the sections were then incubated with 1·5% triethanolamine for 10 min at room temperature and then with 0·25% acetic anhydride for 10 min at room temperature. Prehybridization for 3 hr and hybridization for 16 hr were performed at 54°. After high-stringency washes, [15 min at room temperature in 2× SSC and 30 min at specific hybridization temperatures at descending (2, 1, 0·5, and 0·2×) concentrations of SSC], sections were treated with 1% blocking reagent (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) in 100 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·4, containing 150 mm NaCl and incubated with alkaline phosphatase-coupled digoxigenin (DIG) antibody (1 : 4000 dilution). After washes, (2× in 100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7·4 containing 150 mM NaCl for 15 min), colour development was performed by incubation with 100 mm Tris–HCl, pH 9·5, containing 5 mm levamisole, 0·1% gelatin, nitroblue tetrazolium dye (188 μg/ml) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (375 μg/ml) for 16 hr at room temperature and was stopped by rinsing in tap water.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were microwaved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min at 160W, then blocked with PBS/2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland). Sections were then incubated for 16 hr at 4° with antiserum directed against human IGF-I (Table 1) followed by washing steps (3 × 5 min in PBS/2% BSA) and incubation for 30 min with anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 100 dilution). After repeated washes, (3 × 5 min in PBS/2% BSA), the sections were treated with ABC Mix (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min, rinsed with Tris-buffer, and then the colour was developed by application of Sigma Fast™ 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) in 1 ml of distilled water in the dark for 5–10 min. Nuclei were counterstained with hemalaun for 3 min.

Table 1.

Characterization of the antisera used

| Antiserum against | Reference | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Human CD3 (T lymphocytes) | Clone PS1, Abcam, UK28 | Predilute |

| Human CD20 (B lymphocytes) | Clone L26, Abcam29,30 | 1 : 200 |

| Human CD21 (follicular dendritic cells) | Clone 1F8, Dako31–33 | 1 : 25 |

| Human CD68 (macrophages) | Clone MPG-M1, Dako34 | 1 : 50 |

| Human S100 (interdigitating dendritic cells) | Clone B32.1-astrocyte marker, Abcam35,36 | 1 : 200 |

| Human podoplanin/gp36 (fibroblastic reticular cell) | Clone 18H5, Abcam37–39 | 1 : 200 |

| Human IGF-I | 116 (own antiserum)5,6,10,27,40 | 1 : 200 |

IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor I.

Immunofluorescence

Double immunofluorescence was performed, as recently described,10 with the modification that for demasking the surface marker, antigen sections were treated with antigen-retrieval solution according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark), blocked with PBS/2% BSA (pH 7·4) and incubated overnight at 4° with monoclonal mouse antibodies against different immune-cell markers (Table 1) followed by incubation with polyclonal rabbit IGF-I antiserum 116.5,10,40 Immunoreactions were visualized with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-coupled goat anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 50 dilution; Bioscience Products, Emmenbrücke, Switzerland) and Texas red-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1 : 50 dilution; Amersham International, Little Chalfont, Bucks., UK).

Imaging

After treatments, sections were mounted with Glycergel (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Conventional light and fluorescence photomicroscopy were performed with a Zeiss Axioscope using the axiovision software 3·1 (Zeiss, Zürich, Switzerland). Fluorescence images were analysed using the Imaris software (imaris 3·0; Bitplane AG, Zürich, Switzerland).

Results

IGF-I mRNA and peptide are localized within the human lymph node

Using in situ hybridization with a probe specific for human IGF-I, IGF-I gene expression was found to be localized in numerous cells of different shape within the lymph node (Figs 1a and 2a,c). In the germinal centres, IGF-I mRNA was detected in a mesh-like arrangement (Fig. 1a) similar to that formed by the CD21-positive follicular dendritic cells (Fig. 1c) but also in large single cells in the B-cell area, especially along the mantle zone (Fig. 1a), and in distinct cells within the T-cell area, especially in endothelial cells of the high endothelial venules (HEVs, Fig. 2a,c). Similarly, using an IGF-I-specific antiserum, IGF-I protein was detected in cells within the B- and T-cell compartments (Figs. 1b and 2b,d). Also, here, IGF-I protein was found in a mesh-like arrangement but more discretely (Fig. 1b) and in distinct large cells of different shapes (Figs. 1b and 2b,d), some of which were identified as HEV cells (Fig. 2b).

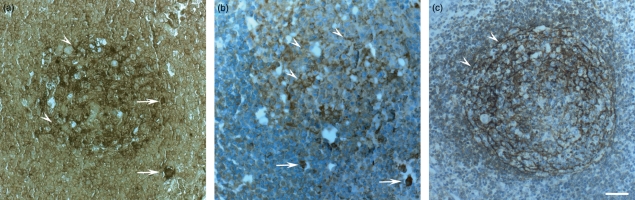

Figure 1.

(a,b) Localization of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein within the human lymph node B-cell area by (a) in situ hybridization with an IGF-I-specific probe and by (b,c) immunohistochemistry with (b) an IGF-I-specific antiserum and with (c) a mouse monoclonal CD21 surface marker. IGF-I gene (a) and protein (b) expressions are localized in solitary large cells (arrows) and in numerous cytoplasmic branches within the germinal center (arrowheads), forming a meshwork arrangement similar to (c) follicular dendritic cells. Bar: 50 μm.

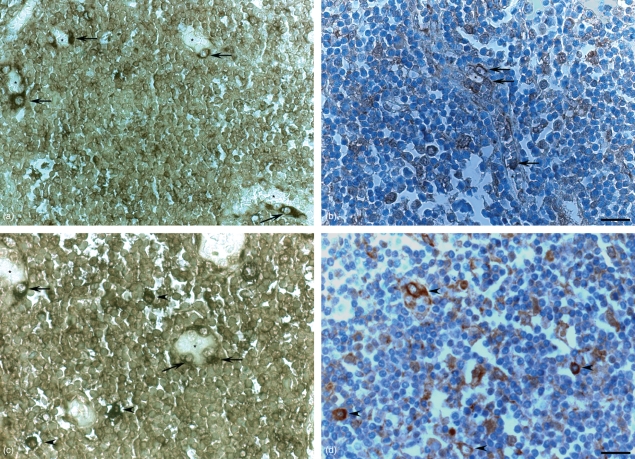

Figure 2.

(a,b) Localization of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein within the human lymph node T-cell area by (a,c) in situ hybridization with an IGF-I-specific probe and by (b,d) immunohistochemistry with an IGF-I-specific antiserum. IGF-I gene (a,c) and protein (b,d) expressions are localized in numerous high-endothelial venule (HEV) cells (arrows) around the blood vessel lumen (asterisk) and in large solitary cells (arrowheads), presumably macrophages. (a,b) Bar: 50 μm, (c,d) Bar: 25 μm.

For further characterization of the different IGF-I immunoreactive cell types, double immunofluorescence was applied (Figs 3–6).

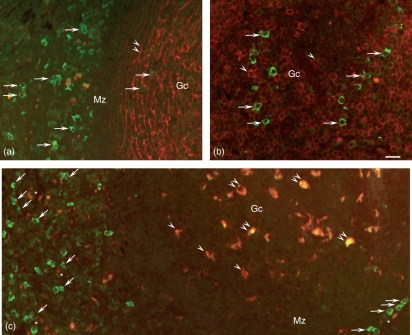

Figure 3.

Localization of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) immunoreactivity (green) by double immunofluorescence staining using a monoclonal antibody directed against (a) follicular dendritic cells (CD21), (b) B lymphocytes (CD20) and (c) macrophages (CD68), visualized in red. (a-c) Numerous cells contain IGF-I immunoreactivity (arrows) within the germinal centre (Gc) and along the mantle zone (Mz). (a,b) No IGF-I imunoreactivity is visible in co-localization with the cytoplasmic branches of the follicular dendritic cells (a, double arrowheads) and with the B cells (b, arrowheads). (c) Co-localization with IGF-I-immunoreactivity (yellow) is found in numerous macrophages within the Gc (double arrowheads), but some macrophages (red) do not contain IGF-I (single arrowheads). Numerous IGF-I immunoreactive cells (green) are not CD68 immunoreactive (arrows) the majority of which are arranged in an epithelial formation along the high-endothelial venule (HEV) lumina (asterisks). Bar: 25 μm.

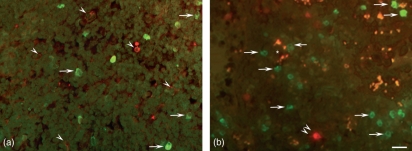

Figure 6.

Localization of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) immunoreactivity (green) by double immunofluorescence staining with a monoclonal antibody against podoplanin/gp36, which identified the fibroblastic reticular cells (red, arrowheads). IGF-I immunoreactivity is present in numerous cells (arrows), probably macrophages and high-endothelial venule (HEV) cells, arranged around the vessel lumen (asterisk), but not co-localized with podoplanin immunoreactivity. Bar: 25 μm.

Identification of IGF-I immunoreactive cells within the B-cell area

Using double immunofluorescence, numerous cells within the lymph follicle revealed IGF-I immunoreactivity but no co-localization was detectable with the follicular dendritic cells identified by their immunoreactivity for CD21 and their typical mesh-like arrangement (Fig. 3a). Moreover, B cells identified by the mouse monoclonal CD20 surface marker within the germinal centres did not contain IGF-I immunoreactive material (Fig. 3b).

Numerous macrophages visualized using a monoclonal antibody (mAb) against CD68 were observed within the B- and T-cell compartments. Almost all CD68-immunoreactive cells within the B-cell compartment also contained IGF-I immunoreactive material. Outside the follicles, especially along the mantle zone, numerous IGF-I immunoreactive cells were not immunoreactive for CD68 (Fig. 3c). Most were aligned along the HEVs in an epithelial arrangement and were thus identified as HEV cells.

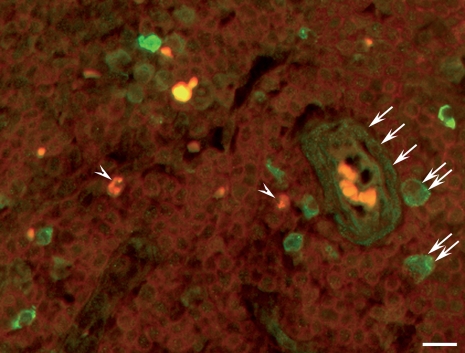

Identification of IGF-I immunoreactive cells within the T-cell area

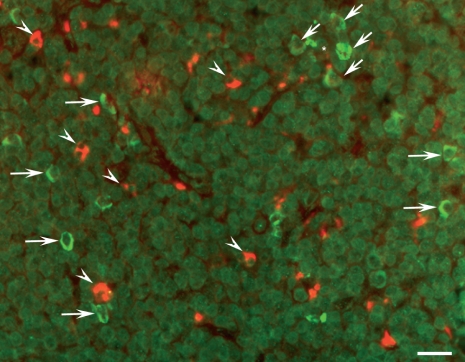

Within the T-cell compartment, using a mouse monoclonal CD3 surface marker, T lymphocytes were detected, but only very few (< 1%) exhibited a co-localization with IGF-I immunoreactivity (Fig. 4). Numerous macrophages, identified by their large cytoplasm, exhibited pronounced IGF-I immunoreactivity. Numerous other cells were immunoreactive for IGF-I, of which a high proportion were arranged around the HEV and were thus identified as HEV cells (Figs 4,5b and 6). Interdigitating dendritic cells were identified using a mouse mAb directed against S100 protein and exhibited the typical veil-like arrangement. No IGF-I immunoreactivity was detectable in the interdigitating dendritic cells (Fig. 5a,b). Fibroblastic reticular cells, as identified by their immunoreactivity for podoplanin/gp36, did not exhibit IGF-I immunoreactivity (Fig. 6).

Figure 4.

Localization of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) immunoreactivity (green) by double immunofluorescence staining with a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD3 surface marker (red). Only very few T lymphocytes also contain IGF-I-immunoreactive material (arrowheads). Numerous macrophages identified by their wide cytoplasm (double arrows) and high-endothelial venule (HEV) endothelial cells (arrows) exhibit IGF-I immunoreactivity. Bar: 25 μm.

Figure 5.

(a,b) Localization of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) immunoreactivity (green) by double immunofluorescence staining with a monoclonal antibody directed against S100 protein to detect the interdigitating dendritic cells (red) that reveal the typical veil-like appearance (double arrowheads). Numerous solitary cells, especially around the high-endothelial venule (HEV) (asterisk), contain IGF-I immunoreactivity (arrows), but this is not co-localized with S100 immunoreactivity (arrow heads). Bar: 25 μm.

Discussion

In the present study in human non-tumoral lymph node, IGF-I gene and IGF-I protein were mainly located in macrophages and follicular dendritic cells, and did not occur in interdigitating dendritic cells. In follicular dendritic cells, IGF-I mRNA was expressed more strongly than IGF-I protein as indicated by the fact that IGF-I immunoreactivity was very faint. This suggests that, after synthesis, IGF-I is released immediately into the surrounding environment where it exerts paracrine effects on B lymphocytes, which themselves do not contain IGF-I-immunoreactive material.

This suggestion is supported by studies where freshly isolated B lymphocytes did not secrete IGF-I in vitro.41 In further agreement, IGF-I mRNA and/or protein were detected in human peripheral lymphocytes at only low levels,13,42 or after stimulation with phytohaemagglutinin43 or modification. For instance, Epstein–Barr virus-transformed B lymphocytes were found to secrete IGF-I in vitro,41 and human B-lineage IM-9 lymphocytes expressed IGF-I mRNA.44 The presence of IGF-I mRNA and immunoreactivity in follicular dendritic cells, but not in B lymphocytes, as observed in the present study, suggests a local trophic role of IGF-I in the B-cell compartment. Furthermore, the precise mechanism of development of follicular dendritic cells and formation of the germinal centres is at present not fully understood.45 Thus, IGF-I synthesis and release to the environment may also be critical for the formation of germinal centres and for the rapid proliferation of B cells.

The presence of IGF-I in most cells capable of phagocytosis and antigen presentation, mainly macrophages, indicates a particular role for IGF-I in immune modulation. This hypothesis is in line with the few data currently available suggesting that human, rat and murine myeloid cells, particularly macrophages, produce IGF-I.13,23,46 The synthesis of IGF-I in macrophages was found to be under stimulatory and inhibitory control by cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-α,47,48 colony-stimulating factors49 and interferon-γ,50 respectively. In our study, macrophages were the immune cells that predominantly expressed IGF-I. The pronounced IGF-I immunoreactivity of the macrophages implies that there is a special need for macrophages to constitutively express autocrine IGF-I, probably as an anti-apoptotic protection factor, because they have to cope with numerous challenges, for example challenge from pathogens.

In the T-cell compartment of the human lymph node, which is adjacent to the follicles, no IGF-I immunoreactivity was observed in interdigitating dendritic cells, which were detected by their immunoreactivity for S100 protein and their typical veiled shape. Only very few T cells recognized by their CD3 surface-marker expression exhibited IGF-I immunoreactive material, which is in line with earlier findings in human T-lymphoblast cell lines18,19 and in human lymphocytes observed to synthesize and secrete IGF-I and to exhibit the IGF-1R.51 However, in a recent study in thymus, IGF-I immunoreactivity was not reported in T cells, and was restricted to thymic epithelial cells.26 Further studies in reactive and neoplastic T-cell proliferation are required to explore the relevance of IGF-I in different T-cell populations.

Fibroblastic reticular cells, in addition to their duty to form a conduit system critical for cortical cell interactions,45,52 are also considered as a reservoir of survival factors for T cells,38 which are postulated to compete for limited amounts of survival factors in the secondary lymphatic tissues.53 However, in the present study, IGF-I immunoreactivity was not detected in the fibroblastic reticular cells identified by their immunoreactivity for podoplanin.37–39 Some possibilities apply to explain the lack of IGF-I in this cell type. The fibroblastic reticular cells in fact may not synthetize IGF-I, which in light of their function seems quite unlikely. Rather, the amount of IGF-I in the fibroblastic reticular cells may be below the detection level, indicating that the cells secrete IGF-I immediately after it is synthesized. Cell culture experiments may help to clarify this point.

However, numerous other cells in the paracortical area contained IGF-I immunoreactivity and were identified as HEV endothelial cells. This finding accounts for the question, why should especially the HEV endothelial cells strongly express IGF-I? This cell type has been found to exhibit different shapes to suit their function. They are often described as cuboidal, which is the appearance of most of the IGF-I immunoreactive cells detected in the present study, in addition to the macrophages. This cuboidal shape is considered to be caused by the transformation of a squamous cell to a high HEV cell, which results in increased surface area of the luminal cell membrane. This transformation is achieved not only by a change of shape but also by hypertrophy of the cell.54 Mitosis, upon antigen stimulus, has for a long time been described in HEV cells55,56 and has been mainly located to hypertrophic HEV cells,57 which would be completely in agreement with our finding that IGF-I mRNA and peptide are located within most of the cuboidal endothelial cells that are probably critically invoved in cell mitosis, hypertrophy and differentiation.54 Furthermore, HEV cells have to encounter cell-differentiation steps, such as changes of cell-membrane composition, to improve lymphocyte recruitment and permanent challenge of cell integrity by lymphocyte penetration of the endothelial wall, which makes special sustainment and anti-apoptotic support substantial.

In summary, it can be stated that the role of IGF-I in the human lymph node appears to be more important than previously assumed and demands further studies on diverse pathologies of the immune system.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully appreciate the skilful technical assistance of Mrs Elisabeth Katz, Mrs Charlotte Burger and Mrs Regine Göhrt.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Jones JI, Clemmons DR. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: biological actions. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:3–34. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallenius K, Sjögren K, Peng XD, et al. Liver-derived IGF-I regulates GH secretion at the pituitary level in mice. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4762–70. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen P. Overview of the IGF-I system. Horm Res. 2006;65(Suppl. 1):3–8. doi: 10.1159/000090640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinecke M. Insulin and the insulin-like growth factors. In: Reinecke M, Zaccone G, Kapoor BG, editors. Fish Endocrinology. Vol. 1. Enfield (NH), Jersey, Plymouth, USA: Science Publishers; 2006. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinecke M, Schmid AC, Heyberger-Meyer B, Hunziker EB, Zapf J. Effect of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) on the expression of IGF-I messenger ribonucleic acid and peptide in rat tibial growth plate and articular chondrocytes in vivo. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2847–53. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.8.7624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maake C, Reinecke M. Immunohistochemical localization of insulin-like growth factor 1 and 2 in the endocrine pancreas of rat, dog, and man, and their coexistence with classical islet hormones. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;273:249–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00312826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatelain PG, Avallet MO, Nicolino M, Lejeune H, Clark A, Chuzel F, Penhoat A, Saez JM. Insulin-like growth factor I actions on steroidogenesis. Acta Paediatr. 1994;399(Suppl.):176–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mason HD, Cwyfan-Hughes SC, Heinrich G, Franks S, Holly JM. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) I and II, IGF-binding proteins, and IGF-binding protein proteases are produced by theca and stroma of normal and polycystic human ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:276–84. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.1.8550764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aberg ND, Brywe KG, Isgaard J. Aspects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I related to neuroprotection, regeneration, and functional plasticity in the adult brain. Scientif World J. 2006;6:53–80. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jevdjovic T, Bernays RL, Eppler E. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) mRNA and peptide in the human anterior pituitary. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:335–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gala RR. Prolactin and growth hormone in the regulation of the immune system. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1991;198:513–27. doi: 10.3181/00379727-198-43286b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorshkind K, Horseman ND. The roles of prolactin, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I, and thyroid hormones in lymphocyte development and function: insights from genetic models of hormone and hormone receptor deficiency. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:292–312. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.3.0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arkins S, Rebeiz N, Biragyn A, Reese DL, Kelley KW. Murine macrophages express abundant insulin-like growth factor-I class I Ea and Eb transcripts. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2334–43. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.8404686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark R. The somatogenic hormones ans insulin-like growth factors-1: stimulators of lymphopoesis and immune function. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:157–79. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.2.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster M, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Clark R, Dorshkind K. Regulation of B and T cell development by anterior pituitary hormones. CMLS, Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:1076–82. doi: 10.1007/s000180050236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velkeniers B, Dogusan Z, Naessens F, Hooghe R, Hooghe-Peters EL. Prolactin, growth hormone and the immune system in humans. CMLS, Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:1102–8. doi: 10.1007/s000180050239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley KW, Weigent DA, Kooijman R. Protein hormones and immunity. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:384–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geffner ME, Bersch N, Lippe BM, Rosenfeld RG, Hintz RL, Golde DW. Growth hormone mediates the growth of T-lymphoblast cell lines via locally generated insulin-like growth factor I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:464–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-2-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baier TG, Jenne EW, Blum W, Schonberg D, Hartmann KK. Influence of antibodies against IGF-I, insulin or their receptors on proliferation of human acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines. Leuk Res. 1992;16:807–14. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(92)90160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auernhammer CJ, Feldmeier H, Nass R, Pachmann K, Strasburger CJ. Insulin-like growth factor I is an independent coregulatory modulator of natural killer (NK) cell activity. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5332–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binz K, Joller P, Froesch P, Bonz H, Zapf J, Froesch ER. Repopulation of the atrophied thymus in diabetic rat by insulin-like growth factor I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3690–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Napolitano LA, Schmidt D, Gotway MB, et al. Growth hormone enhances thymic function in HIV-1-infected adults. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1085–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI32830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansson H-A, Nilsson A, Isgaard J, Billig H, Isaksson O, Skottner A, Andersson IK, Rozell B. Immunohistochemical localization of insulin-like growth factor I in the adult rat. Histochemistry. 1988;89:403–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00500644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelley KW, Arkins S. Role of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factorI in immunoregulation. In: Bercu BB, Walker RF, editors. Growth hormone II: Basic and clinical aspects. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1994. pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada M, Hato F, Kinshita Y, Tominaga K, Tsuji Y. The indirect participation of growth hormone in the thymocyte proliferation system. Cell Mol Biol. 1994;40:111–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marinova TT, Kuerten S, Petrow DB, Angelov DN. Thymic epithelial cells of human patients affected by myasthenia gravis overexpress IGF-I immunoreactivity. APMIS. 2008;116:50–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nauck MA, Reinecke M, Perren A, et al. Hypoglycemia due to paraneoplastic secretion of insulin-like growth factor-I in a patient with metastasizing large-cell carcinoma of the lung. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;92:1600–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steward M, Bishop R, Piggott NH, Milton ID, Angus B, Horne CH. Production and characterization of a new monoclonal antibody effective in recognizing the CD3 T-cell associated antigen in formalin-fixed embedded tissue. Histopathology. 1997;30:16–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.d01-553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montgomery JD, Jacobson LP, Dhir R, Jenkins FJ. Detection of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) in normal prostates. Prostate. 2006;66:1302–10. doi: 10.1002/pros.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polyak MJ, Li H, Shariat N, Deans JP. CD20 Homo-oligomers physically associate with the B cell antigen receptor; dissociation upon receptor engagement and recruitment of phosphoproteins and calmodulin-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18545–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800784200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muretto P. An immunohistochemical study on foetuses and newborns lymph nodes with emphasis on follicular dendritic reticulum cells. Eur J Histochem. 1995;39:301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan JKC, Fletcher CDM, Nayler SJ, Cooper K. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 17 cases suggesting a malignant potential higher than currently recognized. Cancer. 1997;79:294–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura S, Nagahama M, Kagami Y, et al. Hodgkin’s disease expressing follicular dendritic cell marker CD21 without any other B-cell marker. A clinocopathologic study of nine cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:363–76. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehses JA, Perren A, Eppler E, et al. Increased number of islet associated macrophages in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:2356–70. doi: 10.2337/db06-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imura T, Tane K, Toyoda N, Fushiki S. Endothelial cell-derived bone morphogenetic proteins regulate glial differentiation of cortical progenitors. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:1596–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wosik K, Cayrol R, Dodelet-Devillers A, et al. Angiotensin II controls occluding function and is required for blood brain barrier maintenance: relevance to multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9032–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2088-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Angel CE, Lala A, Chen CJ, Edgar SG, Ostrovsky LL, Dunbar PR. CD14 + antigen-presenting cells in human dermis are less mature than their CD1a+ counterparts. Int Immunol. 2007;19:1271–9. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Link A, Vogt TK, Favre S, Britschgi MR, Acha-Orbea H, Hinz B, Cyster JG, Luther SA. Fibroblastic reticular cells in lymph nodes regulate the homeostasis of naive T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1255–65. doi: 10.1038/ni1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiba H, Ishii G, Ito TK, Aoyagi K, Sasaki H, Nagai K, Ochiai A. CD105-positive cells in pulmonary arterial blood of adult human lung cancer patients include mesenchymal progenitors. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2523–30. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eppler E, Zapf J, Bailer N, Falkmer UG, Falkmer S, Reinecke M. IGF-I in human breast cancer: low differentiation stage is associated with decreased IGF-I content. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:813–21. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1460813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merrimee TJ, Grant MB, Broder CM, Cvalli-Sforza LL. Insulin-like growth factor secretion by human B-lymphocytes: a comparison of cells from normal and pygmy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;69:978–84. doi: 10.1210/jcem-69-5-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelley KW, Arkins S. A role for IGF-1 during myeloid cell growth and differentiation. In: Baxter RC, Gluckman PD, Psenfeld RG, editors. The role for insulin-like growth factors and regulatory proteins. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1994. pp. 315–27. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nyman T, Pekonen F. The expression of insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in normal human lymphocytes. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1993;128:168–72. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1280168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clayton PE, Day RN, Silva CM, Hellmann P, Day KH, Thorner MO. Growth hormone induces tyrosine phosphorylation but does not alter insulin-like growth factor-I gene expression in IM-9 lymphocytes. J Mol Endocrinol. 1994;13:127–36. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0130127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Batista FD, Harwood NE. The who, how and where of antigen presentation to B cells. Nature Rev Immunol. 2009;9:15–27. doi: 10.1038/nri2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arkins S, Liu Q, Kelley KW. Theoretical and functional aspects of measuring insulin-like growth factor-I mRNA expression in myeloid cells. Immunomethods. 1994;5:8–20. doi: 10.1006/immu.1994.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noble PW, Lake FR, Henson PM, Riches DWH. Hyaluronate activation of CD44 induces insulin-like gowth factor-1 expression by a tumor necrosis factor-alpha dependent mechanism in murine macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2368–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI116469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fournier T, Riches DW, Winston BW, Rose DM, Young SK, Noble PW, Lake FR, Henson PM. Divergence in macrophage insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) synthesis induced by TNF-alpha and prostaglandin E2. J Immunol. 1995;155:2123–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arkins S, Rebeiz N, Brunke-Reese DL, Minshall C, Kelley KW. The colony-stimulating factors induce expression of insulin-like growth factor-I messenger ribonucleic acid during hematopoesis. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1153–60. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.3.7532579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arkins S, Rebeiz N, Brunke-Reese DL, Biragyn A, Kelley KW. Interferon-gamma inhibits macrophage insulin-like growth factor-I synthesis at the transcriptional level. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:350–60. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.3.7776981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farmer JT, Weigent DA. Expression of insulin-like growth factor-2 receptors on EL4 lymphoma cells overexpressing growth hormone. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gretz JE, Anderson AO, Shaw S. Cords, channels, corridors and conduits: critical architectural elements facilitating cell interactions in the lymph node cortex. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:11–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marrack P, Kappler J. Control of T cell viability. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:765–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sainte-Marie G, Peng F-S. High endothelial venules of the rat lymph node. A review and a question: is their activity antigen specific? Anat Rec. 1996;245:593–620. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199608)245:4<593::AID-AR1>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith C, Hénon BK. Histological and histochemical study of high endothelium of postcapillary veins of the lymph node. Anat Rec. 1959;135:207–13. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091350306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burwell R. Studies of the primary and the secondary immune responses of lymph nodes draining homografts of fresh cancellous bone (with particular reference to mechanisms of lymph node reactivity) Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1962;99:821–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb45365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson ND, Anderson AO, Wyllie RG. Microvascular changes in lymph nodes during skin allografts. Am J Pathol. 1975;81:131–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]