Abstract

Interleukin-2-inducible T cell kinase (ITK) is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase expressed in T cells, NKT cells and mast cells which plays a crucial role in regulating the T cell receptor (TCR), CD28, CD2, chemokine receptor CXCR4 and FcεR mediated signaling pathways. In T cells, ITK is an important mediator for actin reorganization, activation of PLCγ, mobilization of calcium, and activation of the NFAT transcription factor. ITK plays an important role in the secretion of IL-2, but more critically, also has a pivotal role in the secretion of Th2 cytokines, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13. As such, ITK has been shown to regulate the development of effective Th2 response during allergic asthma as well as infections against parasitic worms. This ability of ITK to regulate Th2 responses, along with it's pattern of expression, has led to the proposal that it would represent an excellent target for Th2 mediated inflammation. We discuss here the possibilities and pitfalls of targeting ITK for inflammatory disorders.

Introduction

Current treatment options for many inflammatory diseases mainly involve the use of steroids which cause serious side effects due to the ubiquitous expression of their molecular targets. Consequently the current focus for drug targets include signaling molecules that are specifically expressed in immune cells and play a central role in the regulation of signal transduction pathways that lead to the induction of the inflammatory diseases. ITK is involved in numerous signaling pathways and it is an important regulator of various signaling pathways in immune cells that contribute to the development of numerous inflammatory diseases, including allergies, allergic asthma and atopic dermatitis, and therefore, represents an excellent potential therapeutic target.

ITK belongs to the TEC family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases that includes four other members TEC, BTK, RLK/TXK and BMX [1]. The TEC kinases were recognized as important regulators of signaling cascades in immune cells in 1993 after the discovery that a single point mutation in the TEC kinase, BTK causes B-cell immunodeficiency X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA) in humans and X-linked immunodeficiency (XID) in mice [2, 3]. ITK was discovered after the discoveries of TEC and BTK during a degenerate PCR screen for other novel T cell specific kinases [2-9]. Since then, intensive studies have been performed to discover other immune disorders in which TEC family kinases might play a pivotal role and led to the revelation of ITK as an important player in inflammatory disorders such as allergic asthma and atopic dermatitis [10-14]. Studies in ITK knockout mice have implicated ITK as an important mediator not only of Th2 cell secretion of specific cytokines, but also the release of cytokines and chemokines from mast cells, factors involved in allergies and allergic asthma [15-17]. Genetic analysis in humans has also demonstrated that T cells from patients with atopic dermatitis have elevated levels of ITK [13]. In addition, SNP analysis has revealed a correlation between the presence of a specific haplotype of the ITK and seasonal allergic rhinitis [18]. These findings suggest that ITK may be a promising target for modulating these diseases. In this review, we will discuss the potential benefits and pitfalls of targeting ITK for such diseases.

ITK structure and function

ITK is mainly expressed in T cells (including NK, iNKT and γδ T cells) along with two other TEC kinases, TEC and TXK/RLK [4, 19-26]. In addition, ITK is also expressed in mast cells along with BTK and TEC [27]. In naïve T cells, ITK is expressed at 10-fold and 100-fold higher levels than TXK and TEC respectively and plays an important role both in the cell development as well as function [19, 28]. In differentiated T cells, the expression of ITK is elevated in Th2 cells in comparison to Th1 cells while TXK expression is exclusively increased in Th1 cells [26].

Structurally, ITK is similar to other TEC family kinase members in having a Pleckstrin-Homology (PH) domain at the amino-terminus that allows it to be reversibly recruited to the membrane and a TEC-homology (TH) domain [Fig. 1]. The exception to this is Txk/Rlk, which lacks the PH domain and has instead a cysteine rich region that is myristoylated, allowing it to be permanently anchored in the plasma membrane [27]. The TH domain is composed of a BTK motif, only found in the Tec kinases, and a Proline Rich Region (PRR) [29-31]. In addition to these two domains at the N-terminus, ITK and other Tec kinases have Src homology 3 (SH3), Src homology 2 (SH2) and kinase domains [32, 33]. The SH3 domain allows the interaction with proline rich regions in other proteins, and the PRR of ITK has several high affinity binding sites for SH3 domains. The SH2 domain allows the interaction with tyrosine phosphorylated proteins, while the kinase domain has catalytic function and carries out the tyrosine phosphorylation of substrates.

Figure 1. Domain structure of Tec kinases.

Tec kinases ITK, BTK, BMX and TEC have five domains- a N-terminal Pleckestrin homology (PH) domain, Tec homology (TH) domain, Src-homology 3 (SH3) domain, Src-homology 2 (SH2) domain and a C-terminal Kinase domain. Tec kinase, RLK/TXK is the only exception in having a cysteine-string motif instead of the PH domain at the N-terminus.

The subcellular localization of ITK, with membrane localized ITK being the active form, is critical for its function. This is due to the unique requirements for PI3 kinase generated lipids in the vicinity of specific receptors for activation, which generates inositol lipids phosphorylated at the D3 position to generate Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphates (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3). This creates a binding site for the PH domain of ITK, recruiting it to the plasma membrane [34]. This places ITK in close proximity with Src family kinases, such as Lck, which phosphorylate ITK, leading to its activation [33]. Thus, ITK is activated downstream of receptors that activate this pathway, including the T cell receptor (TCR) as well as the CD2 and CD28 receptor in T cells, the high affinity FcεRI in mast cells, the NKG2D and FcγRIIIA receptors in NK cells. In addition, ITK is also activated by chemokine receptors SDF1α/CXCR4 and CCL11/CCR3 [35-37].

Recent studies also suggest that the enzyme IP3 3-kinase B (ItpkB) can also provide another mechanism to promote the translocation of ITK to the membrane, through generation of a soluble ligand inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate (IP4) via phosphorylation of second messenger inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3). This can promote dimerization of the PH domain of ITK and increased binding to PIP3 at the plasma membrane [38] [Fig. 2]. Studies in Jurkat T cells also suggest that upon translocating to the membrane, the PH domain of ITK enables the formation of dimers of ITK at the vicinity of receptors that can specifically recruit PI3K. The formation of these dimers (or high order clusters) could enable efficient interaction of ITK with other signaling molecules involved in the TCR signaling pathway [39]. Membrane localization of ITK is negatively regulated in T cells via phosphatase PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue) that dephosphorylates PIP3, eliminating the recruitment of ITK via its PH domain [40]. Another phosphatase, SHIP, has also been reported to perform similar function in preventing TEC kinase membrane translocation and activation [41].

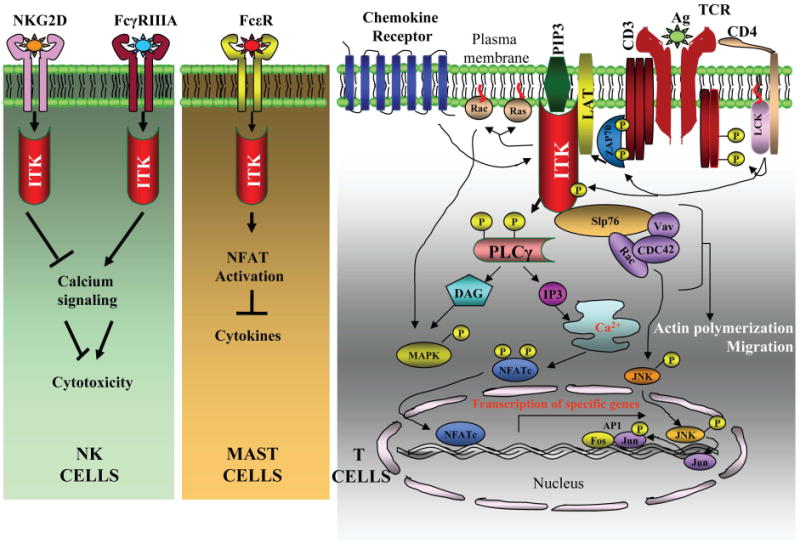

Figure 2. Signaling Pathways regulated by ITK.

ITK acts downstream of signaling pathways in various immune cells including NK cells, mast cells and T cells. In NK cells, ITK has inhibitory role downstream of NKG2D receptor and ITK activation reduces induction of cytotoxicity downstream of this receptor. By contrast, ITK has a stimulatory role downstream of FcγRIIIA receptor and leads to enhanced intracellular calcium increase and cytotoxicity. In mast cells, the absence of ITK results in enhanced calcium signaling and NFAT activation, leading to enhanced secretion of various cytokines such as IL-13 and TNF-α. In T cells, ITK is activated downstream of TcR via Src kinase, Lck. ITK then phosphorylates PLCγ1, resulting in increases in intracellular calcium and activation of MAP kinases, ERK and JNK as well as the transcription factors, NFAT and AP-1. ITK also forms a multimolecular complex with LAT, SLP-76, Vav, Rac and Cdc-42 which induce actin polymerization and cell migration. ITK is also activated downstream of chemokine receptors which can then activate downstream molecules such as Rac and Cdc42 which induce cell migration.

The TH domain of ITK has been suggested to regulate specific protein-protein interactions that control the activity of ITK. Deletion of the PRR of ITK leads to a reduction in the ability of Src kinase to activate ITK, however the ability to phosphorylate the CD28 receptor was not affected [42]. NMR studies of the isolated SH3 and PRR suggest that SH3 domain of ITK may interact in an intramolecular fashion with the PRR [29]. Furthermore, the SH3 domain has a conserved tyrosine residue, Y180, which upon autophosphorylation may regulate the interaction with the PRR [43-45]. Phosphorylation of this residue may also block binding of ITK to negative regulators such as c-Cbl, thereby prolonging the activation state of ITK [46]. These findings suggest a model for the regulation of ITK. In this model, the ITK PRR would interact with the SH3 domain of the same molecule, keeping it in a folded and inactive state [29, 43, 47-53]. Upon activation, or interaction with an SH3 ligand (or another SH3 domain), the ITK molecule would be in an open conformation and easy to activate.

The SH2 domain of ITK has also been reported to exist in either a cis or trans conformation around a conserved proline residue P287. P287 can form an imide bond with N286, to undergo cis/trans isomerization, which can regulate the nature of interaction of SH2 domain with other molecules [48]. In the cis-conformation, the SH2 domain of ITK has a higher affinity for its own SH3 domain, leading to an intramolecular interaction between 2 ITK molecules [29, 47, 49-51, 53]. However, in the trans-conformation, the SH2 domain has a higher affinity for phosphotyrosine containing proteins such as SLP-76 that also simultaneously interacts with the SH3 domain [33]. The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase cyclophilin A has been shown to directly bind to ITK, and is suggested to repress its activity, either by maintaining ITK in the trans-conformation or by catalyzing the rapid conversion between cis and trans conformers [28, 32]. This would suggest the formation of dimers of ITK that are regulated by interaction with Cyclophilin A. However, all of these studies were performed using isolated proteins, and without a structure for the full length ITK, it is not clear if these conformations exist in the full length protein, or in cells.

Recent studies have suggested that a linker region comprising of 17 amino acid residues that flank the SH2 domain plays an important role in regulating the catalytic activity of ITK which is similar to the regulatory mechanism seen in Csk [54]. Mutagenesis studies have revealed that among the 17 residues, W355 is the most crucial residue in the linker region that is required for the kinase activity of ITK. In addition, side chains, Y421 and M410 in the kinase domain that surrounds W355 and have been proposed to form the hydrophobic pocket which is important for the catalytic activity of ITK. In addition, E394 residue in N-terminal kinase lobe is also shown to be essential for regulating kinase activity by possible direct association with W355 residue.

The catalytic activity is a crucial function of ITK, and the crystal structure of the ITK kinase domain reveals that the kinase domain has a typical N-terminal lobe, a hinge region and a C-terminal lobe [54]. The N-terminal lobe comprises of amino-acid residues 357-437 that form a five-stranded anti-parallel β sheet that are connected by a single α helix. There are two loop regions present in the N-terminal lobe, one preceding the C-helix consisting of residues 393-413 and the glycine rich loop consisting of residues 362-378. These two loops along with the C-helix contribute to the formation of the hydrophobic pocket around the ATP binding site and regulate its shape and size. The amino acid residues that mainly contribute in the formation of the hydrophobic pocket are M398, F403, A407, M410 and M411 in the C-helix, F374 in the glycine rich loop and V424, L433 and K391 in the N-terminal lobe. In addition, a unique amino acid residue F435 present in the hinge region is located in the hydrophobic pocket of ITK and is suggested to act as the gatekeeper of the hydrophobic pocket and may be specifically exploited to inhibit the activity of ITK. The C-terminal lobe consists of residues 438-620 that form α-helices and it mainly provides a substrate binding site. The hinge region in the middle connects the two lobes and also contributes in the formation of the ATP binding site. The active ATP binding site of ITK comprises of the kinase sequence Gly-X-Gly-X-X-Gly from the glycine rich loop and the amino acid residues 435-442 from the hinge region of the N-terminal lobe [55]. The amino acid residues I369, V377 and A389 of the N terminal lobe, F435 and Y437 of the hinge region and L489 and C442 of the C-terminal lobe mainly comprise the active ATP-binding site. As previously discussed, the kinase activity of ITK is increased upon transphosphorylation of Y512 by the Src family of kinase, Lck in T cells [30]. This event does not seem to induce a conformational change in the kinase domain. The phosphorylation of this tyrosine residue triggers the catalytic activity of ITK and leads to the phosphorylation and activation of downstream proteins such as SLP-76, PLCγ1 and LAT on their tyrosine residues. Biochemical studies have suggested that the SH2 domain of ITK can interact with the tyrosine phosphorylated SLP-76, which then facilitates the further activation of ITK as well as the tyrosine phosphorylation of SLP-76. After initial activation of the downstream signals, ITK autophosphorylates Y180 within its SH3 domain, although it is not clear if that directly affects the kinase activity, and as discussed above, this event may affect the intra- or inter-molecular interactions between ITK molecules [33].

These findings highlight the potential for the PRR, SH2 and SH3 domains of ITK and their interactions in regulating the activity of ITK. However, the large majority of these experiments were done using isolated domains, and it is not clear if these conformations and interactions occur in cells. Indeed, our most recent findings suggest that in cells, ITK exists as a monomer in the cytoplasm, with the PH domain less than 80 Å from the C-terminus. This structure is maintained by Zn2+ coordinating residues in the TH domain, and not the proline rich region or the SH3 domain1. Clearly, the crystal structure of the full length molecule would shed significant light on the regulation of ITK.

Regulation of signaling pathways by ITK in immune cells

ITK is usually found in the cytoplasm and is recruited to the plasma membrane upon stimulation of specific receptors. In T cells, ITK is activated and recruited to the membrane when the T cell Receptor is triggered by specific antigen, or by the CD2 or CD28 receptors [56-61]. In mast cells, ITK is activated upon binding of IgE/allergen complex to the FcεR [62], and in NK cells upon triggering of NKG2D or binding of IgG and antigen to the FcγRIIIA [Fig. 2] [21, 37, 56, 59]. Although the downstream signals initiated by ITK appear similar in these different cell types, the large majority of the studies done to analyze ITK activation have been done in human Jurkat T cell lines and murine primary T cells [63-68]. Hence, further studies still need to be done in mast cells and NK cells to determine if these signals are the same.

When the TCR is triggered by antigen/MHC complexes, the plasma membrane concentration of phosphatidylinositol 3, 4, 5-triphosphate is increased by the activation of the lipid kinase phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. This generates a high affinity binding site for the PH domain of the ITK, leading to the recruitment of ITK to the plasma membrane [4, 69, 70]. ItpkB has also been suggested to be involved in the activation of ITK by generating phosphatidylinositol 1, 3, 4, 5-tetrakisphosphate, which also interacts with the PH domain of ITK and enhances its interaction with phosphatidylinositol 3, 4, 5-triphosphate [38]. Once at the membrane, ITK is phosphorylated and activated by the membrane resident Src family kinase Lck [67]. The Syk family kinase ZAP-70 is also required for the optimal membrane localization and activation of ITK, most likely via tyrosine phosphorylation of LAT, although the process that requires LAT's involvement remains unknown [4, 38, 69, 70]. Once activated, ITK is involved in tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of phospholipase-Cγ 1 (PLCγ1), and interacts with the adaptor proteins LAT and SLP-76 [30, 71-76]. The interaction between ITK and SLP-76 as confirmed by immunoprecipitation in WT and SLP-76 deficient Jurkat cell lines seem to be critical for the continued activation of ITK during this process because the kinase activity of ITK was completely abrogated upon depletion of SLP-76, but was restored upon addition of SLP-76 [76].

As a result of its ability to phosphorylate and activate PLCγ1, ITK regulates the increase in Ca2+ levels, observed downstream of the TcR [63]. However, while tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 leads to release of intracellular calcium stores as well as influx of calcium from the outside of the cell via the opening of store operated channels in the plasma membrane, T cells lacking ITK seem to have a specific defect in the latter function, while calcium release from intracellular stores are largely intact. T cells lacking ITK also exhibit a reduction in TcR mediated activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway, suggesting that ITK also regulates this process, although the exact mechanism by which the pathway is regulated remains unclear [66, 77]. Similarly, T cells lacking ITK have reduced activation of the transcription factor NFAT, most likely as a consequence of reduced calcium influx, reduced AP-1 activation, and reduced activation of NFκB [21, 64, 66, 77, 78]. ITK can also function as a scaffold, enabling the formation of multimolecular complexes involving the adaptors LAT and SLP-76, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav, the actin regulators Arp1/2 and WASP, and the small G proteins CDC42 and Rac. The latter proteins eventually induce increases in actin polymerization, which is essential for the induction of T cell activation. ITK may fulfill this role in a kinase independent fashion as observed by the rescue of actin polarization and Vav localization upon expression of kinase-inactive form of ITK in Jurkat T cells and human peripheral blood T (PBT) cells that had siRNA mediated inhibition of ITK expression [79-81]. The kinase domain of ITK was also found to be dispensable for antigen receptor mediated activation of an actin regulated transcription factor, Serum Response factor (SRF) [42].

ITK can also be activated by other receptors such as CD28 and CD2 in a Src dependent but ZAP-70 independent manner [56, 59-61]. In the case of CD28 mediated signaling pathway, proliferation and biochemical assays on naïve CD4+ T cells from ITK+/- and ITK-/- mice have shown that ITK is not required for proliferation induced by activation of TCR and CD28 activation. Similar results were found for IL-2 secretion, induction of Bcl-xL and CD40L mRNA levels, and induction of Akt and GSK3β proteins [82]. However, the consequences of ITK activation downstream of CD2 receptor is not fully clear.

ITK has also been reported to regulate chemokine receptor mediated signaling pathway via regulation of the small G-proteins Rac and Cdc42, such that T cells lacking ITK exhibit defects in chemokines CXCL12/SDF1-α and CCL11/Eotaxin mediated migration in vitro and in vivo [35-37]. Lack of ITK also leads to reduced activation of the small G proteins, Rac and Cdc42 in response to CXCL12 in T cells [37]. However, complete function of ITK in these signaling pathways is not yet fully elucidated.

In mast cells, ITK has been reported to be activated downstream of the FcεR1 signaling pathway, along with BTK [15-17, 62, 83]. However, studies using bone marrow derived mast cells (BMMCs) from ITK-/- mice have shown that unlike T cells, mast cells lacking ITK have normal increases in intracellular calcium in response to IgE/antigen stimulation via the FcεR1 mediated signaling pathway [16]. In addition, the FcεR1 mediated activation of the MAPK signaling cascade is also not significantly affected in ITK-/- mast cells and they display normal levels of phosphorylation of ERK and p38 upon activation, suggesting that ITK does not regulate the calcium and MAPK signaling pathways in mast cells. In contrast, these cells express elevated levels of IL-13 and TNF-α upon FcεR1 mediated stimulation. Analysis of expression level as well as cytoplasmic vs. nuclear localization of NFAT transcription factors suggest that even at a basal state, ITK-/- mast cells have increased level of expression of both NFAT-1 and 2, and NFAT1 is constitutively localized in the nucleus. These observations therefore suggest that in mast cells, ITK may play a negative role in regulating the activation of NFAT-1 transcription factor, that could eventually regulate the activation of cytokines IL-13 and TNF-α [16]. However, further studies would be required to elucidate the mechanisms by which ITK regulates the signaling pathway downstream of FcεR1 receptor in mast cells.

Role of ITK in T cell development

The net effect of various alterations in signaling in the absence of ITK is altered development of conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, reduced T cell differentiation to the Th2 lineage, and reduced production of interleukin-2 (IL-2), with accompanying reduced T cell proliferation [68, 77, 84-93]. However, the absence of ITK and accompanying downstream effects may be partially compensated to some extent by other Tec kinases expressed in T cells such as RLK/TXK, since mice lacking both ITK and RLK/TXK exhibit a slightly more severe phenotype [68, 88, 90]. It is not clear if Tec is also able to partially compensate for the lack of ITK in T cells.

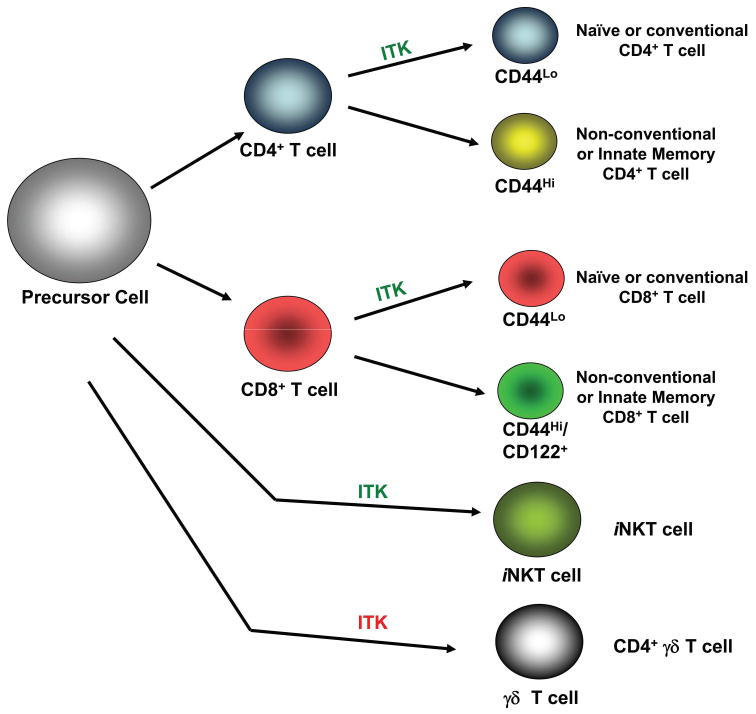

In the absence of ITK, the development of naïve CD4 and CD8 T cells is severely affected [Fig. 4] [68, 77, 84-93]. Indeed, in ITK-/- mice, the majority of the T cells are non-conventional or innate memory T cells [88, 91, 92]. The CD8+ T cells that develop are largely CD44Hi/NK1.1+/CD122+ and IL-15 receptor α chain positive, while the CD4+ T cells are largely CD44Hi/CD62Llo [88, 91, 92]. Both populations carry preformed message for cytokines such as IL-4 and IFN-γ, and rapidly secrete these cytokines upon activation [86-92, 94, 95]. However, ITK signaling does not seem to be required for the development and function of these non-conventional or innate memory CD4 and CD8 T cells. Instead, ITK plays a positive role in the development of conventional naïve CD4 and CD8 T cells. The transcription factors Eomesodermin and promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) have been suggested in playing mechanistic role in skewing the development of T cells towards the innate phenotype [96]. However, further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms through which ITK and the transcription factors Eomesodermin and PZLF regulate innate T cell development.

Figure 4. Role of ITK in the development of conventional and innate T cells.

ITK in green indicates that ITK positively regulates these pathways, while ITK in red indicates that the absence of ITK leads to enhanced development of these cells. The presence of ITK induces precursor T cells to develop into conventional CD4 or CD8 T cells that express low levels of CD44. However, in the absence ITK, development of conventional T cells is reduced, and the majority of T cells that remain are of the innate memory or non-conventional like T cells, with high of expression of CD44 as well as CD122 and preformed cytokine message. In other non-conventional T cells, ITK plays a positive role in the development of iNKT cells and a negative role in γδ-T cell development.

By contrast, ITK has been shown to be important in the development of other non-conventional T cells, iNKT cells and γδ T cells2 [25, 97-99]. The absence of ITK leads to a significant decrease in the number of iNKT cells as well as their function, and it has been suggested that this may be due to a regulatory role of ITK downstream of Fyn in signaling pathway regulated by SLAM family of receptors that eventually regulate the development of these cells [Fig. 4]. Further studies are required to fully understand the role of ITK in NKT cell development.

In γδ T cells, lack of ITK leads to increased development of a population of CD4+ γδ T cells, some of which also carry the NK1.1 receptor, suggesting that ITK has a negative role in regulating the development of these cells [Fig. 4] [98, 99]. These CD4+ γδ T cells carry preformed message for IL-4 and predominantly secrete this cytokine, but not IFN-γ or IL17. More importantly, these γδ T cells contribute to the paradoxically high levels of IgE observed in ITK-/- mice [16, 98, 99]. The increased levels of these cells in the absence of ITK may be the result of reduced signaling during the development of these γδ T cells, and their expression of PLZF, although the mechanism by which ITK regulates their development remains unclear.

Role of ITK in T cell differentiation

CD4+ T helper cells usually differentiate into Th1, Th2 or Th17 cells depending on the nature of the cytokine milieu and the expression of specific transcription factors [100, 101]. Th1 cells secrete IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF and Lymphotoxin-β (LT-β) and induce immune responses against intracellular pathogens. Th1 cells also mediate isotype switching to IgG2a upon stimulation. Th1 cells require cytokines IFN-γ, IL-12, IL-18, IL-23 and IL-27 in the cytokine milieu and increased activation of transcription factors, mainly, T-bet, Hlx, STAT4, and IRF1 for their differentiation [100]. Cytokines IFN-γ and IL-12 are crucial for the differentiation of Th1 cells as they induce the activation of transcription factors STAT1 and STAT4 via the JAK/STAT pathway. In addition, IL-12 works synergistically with IL-18, IL-23 and IL-27 to maintain optimal levels of IFN-γ which is essential for differentiation into Th1 cells. In addition, IFN-γ also stabilizes IL-12R which is required for IL-12 production. The transcription factor, T-bet is the master regulator of Th1 cells and it upregulates the production of IFN-γ by remodeling the chromatin of IFN-γ and exposing its hypersensitive sites as well as inducing IL-12/STAT4 mediated secretion of IFN-γ. In addition, T-bet also suppresses the expression of Th2 cytokines, IL-4 and IL-5. Other transcription factors, Hlx and IRF1 have also been reported to contribute to the upregulation of IFN-γ, although the exact mechanism is still unclear. Th1 cells have been implicated in the immune response to intracellular bacteria and viruses, and in models of autoimmune diseases such as EAE, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, lupus and intestinal inflammatory disorders [100, 102-109].

Th2 cells, by contrast, secrete IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13 and IL-19 and induce immune responses against extracellular parasites such as helminthes and mediate isotype switching to IgG1 and IgE [101]. Th2 cells require cytokines IL-4 and IL-2 and transcription factors GATA-3, c-maf, STAT6 along with NFAT, NFκB and AP-1 for their differentiation. While IL-2 is required for maintaining normal proliferation of Th2 cells and for inducing STAT5a mediated upregulation of IL-4 production, IL-4 is the key cytokine that regulates the differentiation of Th2 cells. IL-4 induces the activation of transcription factors STAT5a and STAT6 via the JAK/STAT pathway which then enables STAT-6 mediated activation of GATA3, which is the master regulator of Th2 cell differentiation. GATA-3 can induce the production of Th2 cytokines, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 by directly binding to the hypersensitive sites on the chromosome locus. In addition, GATA3 also specifically suppresses the expression of STAT-4 and IL-12Rβ2 thereby inhibiting Th1 cell differentiation. Transcription factor, c-maf also contributes to IL-4 production by directly binding to the MARE site in the IL-4 promoter. NFAT 1 and 2 transcription factors further enhance IL-4 production in association with IRF-4 which is activated by c-Rel, as well as AP-1 and c-maf. Th2 cells have been implicated in the immune response to parasites and other multicellular organisms, and in models of autoimmune diseases such as allergic asthma [110-113].

Th17 cells secrete IL-17A, IL-6, G-CSF, GMSCF and TNFα, and although less is known about these cells, IL-17 is critical for the recruitment of neutrophils [114]. These cells are dependent on IL-6 and TGF-β for their differentiation, and require the master transcriptional regulator RORγc. Th17 cells have been implicated in extracellular bacterial responses, as well as in models of autoimmune diseases such as EAE and multiple sclerosis [115-117].

Biochemical and in vivo studies have suggested that ITK plays an important role in the induction of Th2 cell responses since mice lacking ITK had defects in combating diseases and infections that usually require a Th2 response such as allergic asthma and helminthic infections [10, 12, 68, 84]. The defect in inducing Th2 response seen in the absence of ITK could be due to a variety of reasons. Most importantly, the absence of ITK affects the calcium pathway required for activation and nuclear translocation of transcription factors such as NFAT [21, 64, 66, 77, 84]. The activation of NFAT is essential for the expression of IL4, required for the elaboration of Th2 effector function. ITK may also negatively regulate the expression of the transcription factor T-bet, a master regulator of Th1 differentiation, such that T cells are prevented from differentiating along a Th2 pathway [26]. In fact, naïve T cells lacking ITK have increased expression of T-bet which could potentially skew the naïve T cells to differentiate into Th1 cells instead of Th2 cells [26, 91]. However, T cells lacking ITK can differentiate along the Th2 pathway when forced to do so in the presence of the Th2 promoting cytokine IL-4, but continue to be defective in secreting IL4 under those conditions [118]. A better understanding of these pathways downstream of ITK will reveal more insights into the molecular basis for the functional effects of its absence.

Role of ITK in inflammatory diseases

ITK has been shown to play an important role in the development of Th2 mediated disease. The lack of ITK results in impaired or altered immune response in a variety of diseases, mainly due to the defect in developing normal Th2 responses. T cells lacking ITK have reduced secretion of IL-4, indicating that ITK regulates the production of Th2 cytokines [26, 77]. Confirming this function, ITK is reported to be involved in the Th2 response during allergic asthma [10, 12, 14, 119]. Other studies have also suggested that ITK is involved in the acute phase response of allergic asthma, by regulating the degranulation of mast cells downstream of the IgE/FcεR. Indeed, ITK knockout mice show decreased mast cell degranulation and plasma extravasation in vivo, key symptoms of an acute phase response upon challenge [15]. These mice also show reduced airways hyperresponsiveness in an acute IgE/Allergen challenge in vivo [16]. However, our more recent studies using bone marrow derived mast cells from these mice suggest that ITK does not affect the ability of mast cells to degranulate and thus may not play a role in regulating the function of mast cells during acute phase of allergic asthma responses[16]. Indeed, transfer of ITK null mast cells to mast cell deficient mice indicates that these cells are perfectly capable of degranulating in vivo upon IgE/Allergen challenge. The observed discrepancy between the in vivo response and the in vitro and transfer responses in the development of an acute response in these ITK-/- mice can be attributed to high basal levels of IgE in these mice, which interfere with the binding of antigen-specific IgE to FcεR and prevent the activation of mast cells leading to nonresponsiveness during the acute phase of allergic asthma [16]. The cause of this high level IgE in the mice lacking mast cells may be the abnormal development of CD4+ γδ T cells that secrete elevated levels of IL-4, inducing class switch in B cells [16, 98, 99]. Furthermore, the absence of ITK causes increase in the level of Th2 cytokine production in mast cells, such that these cells secrete elevated levels of pro-inflammatory and Th2 cytokines in vitro, due in part to elevated activation of the NFAT transcription factor [16].

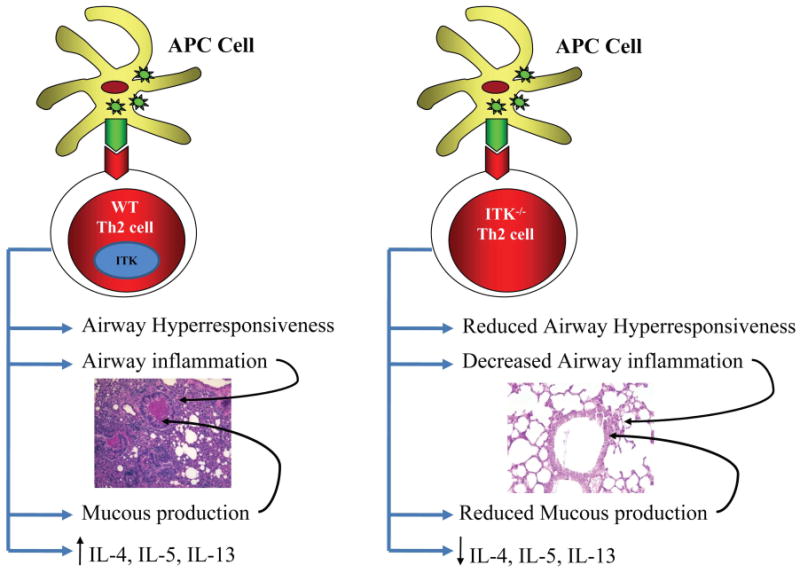

However, ITK has been shown to play a crucial role in the development of late phase responses of allergic asthma which is dependent on T cells [10-12, 14, 119]. Using ovalbumin or HDM3 as a model allergen, mice lacking ITK have been shown to exhibit reduced symptoms of late phase of allergic asthma. This includes airway inflammation, goblet cell hyperplasia, mucous production, airway hyperresponsiveness and tracheal responses [10, 12]. These mice also produce reduced levels of Th2 cell specific effector cytokines IL4, IL5 and IL13, cytokines that play a pivotal role in the development of allergic asthma [Fig. 3] [10, 12]. Furthermore, overexpression of another Tec family kinase, RLK/TXK in the ITK-/- mice has been shown to rescue the Th2 responses in these mice leading to increased production of Th2 cytokines, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 and the mice were able to develop allergic asthma [119]. These observations indicate that ITK and TXK have redundancy in their functions for T cell differentiation, despite having different structures. The data therefore suggest that the proposal by Berg and colleagues that selective expression of ITK in Th2 cells may render these cells more susceptible to inhibition of Th2 responses when ITK is absent, may be an accurate model of how these kinases regulate Th2 responses [120]. Using ITK-/- mice expressing an ITK kinase domain deleted transgene, we have also shown that the kinase domain of ITK is essential for the induction of normal Th2 response and for the production of Th2 cytokines and development of allergic asthma, suggesting that targeting the kinase domain of ITK may be sufficient to inhibit Th2 responses and development of allergic asthma [14]. By contrast, migration mediated by CCL-11/eotaxin was significantly reduced in WT T cells expressing this ITK kinase mutant, and these mice did not develop allergic asthma, although their T cells could generate normal levels of Th2 cytokines [14]. These studies suggest that while some of the signaling responses such as cell proliferation and cytokine production can be occur in the presence of presumably lower levels of TCR generated signal in the presence of decreased kinase activity of ITK, other signaling responses such as chemokine mediated migration are highly sensitive to the strength of signal, requiring high levels of kinase activity of ITK in order to respond to chemokine mediated signals. These studies therefore indicate that ITK inhibitors can potentially be used as pharmacological agents for the treatment of the late phase symptoms of allergic asthma. These studies also suggest that by manipulating the level of kinase activity of ITK, a therapeutic approach can be developed such that only the chemokine mediated responses are prevented while still maintaining normal Th2 responses that are required for combating numerous infections that require Th2 responses at other tissue sites.

Figure 3. Role of ITK in allergic asthma.

ITK plays an important role in the induction of asthma. In the presence of ITK, exposure to allergens induces airway hyperresponsiveness, increased airway inflammation, mucous production, increased infiltration of inflammatory cells and increased secretion of Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13. Absence of ITK leads to decreased airway hyperresponsiveness as well as reduced airway inflammation, mucous production and Th2 cytokine production.

Infections with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, Leishmania major or Schistosome mansonii normally result in a strong Th2 response with lack of clearance due to the absence of Th1 response, however, mice lacking ITK exhibit strong Th1 responses, and produce normal levels of T cell mediated IFN-γ [68], and are therefore effective in clearing these pathogens [77, 78]. In the case of Leishmania major infections, wild type mice (on a Balb/c background) have a predisposition toward generating a Th2 response instead of a Th1 response, and normally cannot clear infection with this parasite. However, mice lacking ITK (on the same background) efficiently clear the infection by this parasite [78]. This is most likely due to the enhanced Th1 response due to reduced Th2 response in the absence of ITK. These data suggest that by suppressing ITK activity, one can increase the effectiveness of the Th1 response towards L. major infection by suppressing the Th2 responses. This suppression should be helpful in humans who are infected with this parasite. Indeed, ITK null mice have enhanced anti-bacterial responses to infection with Listeria monocytogenes [92]. More importantly, ITK null mice have normal responses to infection with the respiratory pathogen Bordetella parapertussis, suggesting that an ITK inhibitor would not affect immune responses to this pathogen4.

Agents that suppress ITK function therefore, could potentially be beneficial in the treatment of allergic asthma without significantly affecting normal Th1 cell function. Nevertheless, normal Th1 response is not always sufficient for inducing effective immune responses required for clearing of some infections. Mice lacking ITK have been shown to succumb to infection caused by Toxoplasma gondii, even though this pathogen usually elicits a Th1 response [68]. However, the full nature of the immune response that leads to effective immunity against T. gondii is still unclear.

By contrast, increased levels of expression of ITK has been reported in patients with atopic dermatitis, unspecified peripheral T-cell lymphomas (U-PTCLs) and aplastic anemia. In the case of atopic dermatitis, high levels of ITK was detected in peripheral blood T cells of patients [13]. In patients suffering from atopic dermatitis, elevated levels of ITK and T-bet was detected in unstimulated T cells indicating that ITK and T-bet probably play important roles in regulating this disease. Although ITK is being suggested as a marker for screening patients for the active form of atopic dermatitis, the mechanism by which ITK possibly regulates the disease still needs to be explored. One possible mechanism suggested is that ITK regulates the activity of the serine/threonine kinase PKCθ, since specific inhibition of PKCθ using Rottlerin resulted in a 50% reduction in T-bet and IFN-γ expression.

More recently, humans with mutations in ITK have been reported. This work reported on a the occurrence of a novel type of immunodeficiency syndrome in two Turkish females due to a R335W homozygous mutation in the SH2 domain of ITK, that leads to increased susceptibility to EBV infection leading to EBV-positive B cell proliferation and Hodgkin's lymphoma [121]. This mutation is similar to other mutations in humans in the SH2 domains of BTK (Y361C) and SAP (Q99P) that lead to previously reported immunodeficiencies, X-Linked Aggammaglobulinemia (XLA) and X-Linked Lympho proliferative Disease (XLP) respectively. These subjects had undetectable levels of ITK protein despite normal levels of mRNA, indicating that the R335W mutation affects the stability of the protein and leads to the degradation of ITK. These subjects also had negligible levels of NKT cells, along with their parents who were heterozygous for this mutation, confirming a role for ITK in the development of these cells, and a role for NKT cells in combating EBV infection. However, the parents of these subjects never succumbed to EBV infection suggesting a role for other factors in the susceptibility to EBV infections. More interestingly, these patients also have the presence of CD8+ T cells that have the phenotype of non-conventional or innate memory (note that the CD4+ or γδ T cells were not analyzed). Further studies on individuals with either heterozygous or homozygous mutations would therefore shed more light on the impact of this ITK mutation on the function of various immune cells that contribute to the development of the disease and susceptibility to numerous infections. It is likely that as in the mouse, these phenotypes are due to changes in the development of T cells, and may not reflect the situation that would occur if these cells were allowed to develop, and the activity of ITK inhibited in the periphery. Studies of this nature are required to fully determine the function of ITK in peripheral T cells during an immune response.

ITK as an anti-inflammatory target

ITK plays a pivotal role in the regulation of signaling pathways that are central to inflammatory responses, such as production of various cytokines by Th2 cells and mast cells. ITK regulates the calcium dependent signaling pathways that lead to the activation of transcription factors such as NFAT, NFκB and AP1. These factors can regulate multiple inflammatory cytokines such as Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, but also other cytokines such as IL-2. ITK is also important in regulating signaling pathways required for cell adhesion and cell migration in response to specific chemokines such as SDF1-α and CCL-11. Since the kinase activity of ITK has been shown to play a crucial role in activation of downstream signals via phosphorylation of proteins such as PLCγ1, the kinase domain of ITK has therefore been the key target for potential inhibitors. Small molecules specifically binding to the ATP binding pocket in the kinase domain of ITK can prevent the initiation of kinase activity and will be discussed further below [122-126]. However, the PH domain of ITK can also be targeted, since preventing the recruitment of ITK to the plasma membrane can prevent its activation [69]. In addition, the PH domain has a binding pocket for a small molecule similar to that seen for the ATP binding pocket. Targeting this PH domain has been shown to be effective in pharmaceutically inhibiting the activation of other PH domain containing proteins such as Akt [127]. The SH3 and SH2 domains of ITK could also be potentially targeted, thus preventing interactions with potential substrates. However, since these domains may have functions in the regulation of ITK, as well as in regulating signaling pathways independent of the kinase domain, more work needs to be done to get a better understanding of this process before this approach is attempted.

Current ITK inhibitors

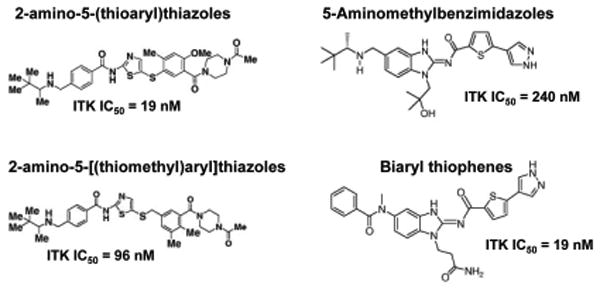

Numerous approaches for inhibiting ITK signaling activity have been developed and several others are currently being developed. One of the approaches involves targeting the kinase activity of ITK and numerous small molecule inhibitors have been synthesized for this approach. Specifically targeting ITK should in principle be possible, as ITK has within its catalytic site, a unique gatekeeper residue F435, that could be exploited in the development of small molecule inhibitors of the kinase domain [55]. A number of inhibitors of ITK have been reported, but it is not clear if any of them have exploited this unique area of the kinase domain [Fig. 5].

Figure 5. Structures of select ITK inhibitors.

Select ITK inhibitor scaffolds and their IC50s. 2-amino-5-(thioaryl)thiazoles, 5-Aminomethylbenzimidazoles and 2-amino-5-[(thiomethyl)aryl]thiazoles (Bristol-Myers Squibb), Biaryl thiophenes (Boehringer Ingelheim).

Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceuticals has developed small molecule inhibitors specific to ITK [BMS-488516 and BMS-509744] [Fig. 5] [122-124]. These inhibitors have been tested in vitro on the human Jurkat T cell line and shown to specifically inhibit ITK and block tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of PLCγ1. These inhibitors also demonstrated efficacy in suppressing lung inflammation and infiltration of total cells and eosinophils in a murine model of allergic asthma. Although these inhibitors look promising, more studies are needed to test their efficacy, stability and toxicity levels in humans.

Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals have also recently reported the discovery of 5-aminomethylbenzimidazole compounds that specifically inhibit ITK by targeting the kinase specificity pocket [Fig. 5] [125, 126]. In vitro studies using human whole blood assays indicate that these compounds are capable of inhibiting IL-2 secretion with an IC50 of 240 nM or 690 nM. Further in vivo studies in Balb/c mice showed that oral administration of these compounds inhibited IL-2 and IL-4 production in response to anti-CD3 antibody in a dose dependent manner with high potency [128, 129]. It should be noted that this anti-CD3 in vivo assay largely targets iNKT cells, and confirm the role of ITK in regulating the cytokine secretion of iNKT cells.

Astrazeneca has generated Thiazolyl and Triazine compounds as novel ITK inhibitors5. However, data on the characterization of these compounds have yet to be published in peer review articles. Cellzome has also reported on the discovery of Diazolodiazine and Triazole derivatives as inhibitors for ITK although they are still under investigation with regards to specificity and selectivity6. Sanofi-Aventis has generated Thienopyrazole compounds but has not yet published the specifications of these compounds7. Vertex Pharmaceuticals has reported Pyrid-2-one compounds as ITK inhibitors but has not reported any details about the specificity and activity of the drugs8. In addition, some of these compounds appear to have poor selectivity for ITK, as they have also been reported to bind to other proteins such as HSM801163, PCTK3, PFTK1, CRK7, PRKCN, CIT, STK6, PDK1, PAK4, BMX, PRKCM, NEK6 or PDPK18.

Certain natural products such as Rosmarinic acid and extracts from Polyscias murrayi have also been suggested to inhibit phosphorylation and activation of ITK, as well as the downstream enzyme PLCγ1 by inhibiting calcium mobilization and NFAT activation triggered by the T cell receptor [130]. However, these products do not appear to specifically inhibit ITK activity as in some studies they were also capable of inhibiting Lck [131, 132]. In addition, studies with extracts from Polyscias murrayi only analyzed the inhibition of the kinase activity of ITK and thus more work needs to be done to determine the specificity against other kinases as well as their effect on cell and animal models [133].

Finally, siRNA has also been used to reduce the expression of ITK in human NK cells. In one set of studies, reduction of ITK resulted in reduced NK cell activation via the FcγR receptor, but enhanced responses when the cells were stimulated with the NKG2D receptor [21]. In another set of studies, ITK expression was reduced in the Jurkat T cell line, which resulted in reduced biochemical responses to T cell receptor stimulation [79]. However, this approach is still at a very preliminary stage and further studies needs to be done to confirm if this approach could be effective in vivo.

Conclusions and challenges

Although intensive studies have been done to study the role of ITK in various signaling pathways and cell types, further research is required to elucidate the specific functions of ITK in mast cells, iNKT and γδ T cells. While ITK is required for the development and/or secretion of Th2 cytokines, development and secretion of cytokines from iNKT cells, it also seems to be dispensable for the development of non-conventional or innate memory T cells that can secrete these cytokines. In addition, the absence of ITK results in increased numbers of CD4+ γδ T cells that are potent IL-4 secretors and can induce class switch to IgE. Finally, ITK may negatively regulate cytokine secretion in mast cells. Thus while ITK null animals are resistant to developing allergic asthma, the differential response of individual cells to the absence of ITK suggest caution in interpreting these results. More work is needed to carefully unravel the role of ITK in the development in these cells, and determine whether it is different from their function during an inflammatory response. It is possible, that as seen in the association studies, elevated ITK is critical for the development of specific types of inflammation, and it is therefore feasible to attempt targeting ITK in order to manipulate the Th1/Th2 responses against specific infections or in specific diseases.

In addition, further studies are required to determine if ITK regulates the signaling pathways in these cells in a similar fashion as observed in CD4+ T cells or whether it couples to different downstream pathways in specific cell types. The role of ITK in chemokine mediated signaling pathways suggest that careful targeting of ITK may accomplish similar ends in inhibiting allergic inflammation.

The animal models of disease examined so far, have for the most part used mice lacking ITK. These mice provide a valuable tool in assessing the role of ITK in various disease processes. However, caveats remain since these animals have differential development of specific immune cells that have developed in the absence of ITK, and any changes observed may be due to these developmental changes. Therefore future experiments would need to assess the role of ITK in various diseases using “knockin” mice carrying kinase inactive forms of ITK, or inducible expression of ITK. These genetic experiments could be confirmed using ITK specific inhibitors. However, any ITK specific inhibitors need to be fully characterized with regards to their specificity and selectivity. Finally, there are other Tec family kinases expressed in T cells, TXK/RLK and TEC [1, 33, 119]. These other Tec kinases may rescue some functions of ITK and so the role of these other kinases in disease processes also have to be fully evaluated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (AI51626, AI065566 & AI073955) to AA. The CMIID at Penn State is supported in part by a grant from the PA Department of Health. There are no conflicts of interests to report.

Footnotes

Qi and August, Submitted.

Qi and August, Unpublished.

Sahu and August, In Preparation.

Wolfe et al, In Preparation.

References

- 1.Smith C, Islam T, Mattsson P, Mohamed A, Nore B, Vihinen M. The Tec family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases: mammalian Btk, Bmx, Itk, Tec, Txk and homologs in other species. Bioessays. 2001;23:436–446. doi: 10.1002/bies.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsukada S, Saffran D, Rawlings D, Parolini O, Allen R, Klisak I, Sparkes R, Kubagawa H, Mohandas T, Quan S, et al. Deficient expression of a B cell cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase in human X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Cell. 1993;72:279–290. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90667-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rawlings D, Saffran D, Tsukada S, Largaespada D, Grimaldi J, Cohen L, Mohr R, Bazan J, Howard M, Copeland N, et al. Mutation of unique region of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in immunodeficient XID mice. Science. 1993;261:358–361. doi: 10.1126/science.8332901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson M, Kane L, Su J, Kadlecek T, Mollenauer M, Weiss A. Expression and function of Tec, Itk, and Btk in lymphocytes: evidence for a unique role for Tec. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2455–2466. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2455-2466.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siliciano J, Morrow T, Desiderio S. itk, a T-cell-specific tyrosine kinase gene inducible by interleukin 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11194–11198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyeck S, Berg L. Developmental regulation of a murine T-cell specific tyrosine kinase gene, Tsk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:669–673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson S, Leung B, Squire J, Hill M, Arima N, Goss P, Hogg D, Mills G. Identification, cloning, and characterization of a novel human T-cell-specific tyrosine kinase located at the hematopoietin complex on chromosome 5q. Blood. 1993;82:1561–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka N, A H, Ohtani K, Nakamura M, Sugamura K. A novel human tyrosine kinase gene inducible in T cells by interleukin 2. FEBS Letters. 1993;324:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81520-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada N, Kawakami Y, Kimura H, Fukamachi H, Baier G, Altman A, Kato T, Inagaki Y, Kawakami T. Structure and expression of novel protein-tyrosine kinases, Emb and Emt, in hematopoietic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:231–240. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller C, August A. Attenuation of immunological symptoms of allergic asthma in mice lacking the tyrosine kinase Itk. J Immunol. 2003;170:5056–5063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrara T, August A, Ben-Jebria A. Modulation of tracheal smooth muscle responses in inducible T-cell kinase knockout mice. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2004;17:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrara T, Mueller C, Sahu N, Ben-Jebria A, August A. Reduced airway hyperresponsiveness and tracheal responses during allergic asthma in mice lacking tyrosine kinase inducible T-cell kinase. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:780–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto Y, O T, Obayashi I, Imai Y, Matsui K, Yoshida NL, Nagata N, Ogawa K, Obayashi M, Kashiwabara T, Gunji S, Nagasu T, Sugita Y, Tanaka T, Tsujimoto G, Katsunuma T, Akasawa A, Saito H. Identification of highly expressed genes in peripheral blood T cells from patients with atopic dermatitis. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2002;129:327–340. doi: 10.1159/000067589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahu N, Mueller C, Fischer A, August A. Differential sensitivity to Itk kinase signals for T helper 2 cytokine production and chemokine-mediated migration. J Immunol. 2008;180:3833–3838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forssell J, Sideras P, Eriksson C, Malm-Erjefalt M, Rydell-Tormanen K, Ericsson P, Erjefalt J. Interleukin-2-inducible T cell kinase regulates mast cell degranulation and acute allergic responses. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:511–520. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0348OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyer AS, A A. The Tec family kinase, IL-2-inducible T cell kinase, differentially controls mast cell responses. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180:7869–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felices M, F M, Kosaka Y, Berg LJ. Tec kinases in T cell and mast cell signaling. Advances in Immunology. 2007;93:145–84. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)93004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson M, M R, Barrenäs F, Halldén C, Naluai AT, Säll T, Cardell LO. A haplotype in the inducible T-cell tyrosine kinase is a risk factor for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2009 Feb 13; doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.01991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucas J, Miller A, Atherly L, Berg L. The role of Tec family kinases in T cell development and function. Immunol Rev. 2003;191:119–138. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colgan J, A M, Neagu M, Yu B, Schneidkraut J, Lee Y, Sokolskaja E, Andreotti A, Luban J. Cyclophilin A regulates TCR signal strength in CD4+ T cells via a proline-directed conformational switch in Itk. Immunity. 2004;21:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khurana D, A L, Schoon RA, Dick CJ, Leibson PJ. Differential regulation of human NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity by the tyrosine kinase Itk. Journal of Immunology. 2007;178:3575–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gadue P, S P. NK T cell precursors exhibit differential cytokine regulation and require Itk for efficient maturation. Journal of Immunology. 2002;169:2397–406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Au-Yeung BB, F D. A key role for Itk in both IFN gamma and IL-4 production by NKT cells. Journal of Immunology. 2007;179:111–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felices M, Yin C, Kosaka Y, Kang J, Berg L. Tec kinase Itk in gamma-delta-T cells is pivotal for controlling IgE production in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808459106. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felices M, Berg LJ. The Tec kinases Itk and Rlk regulate NKT cell maturation, cytokine production, and survival. J Immunol. 2008;180:3007–3018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller AT, Wilcox HM, Lai Z, Berg LJ. Signaling through Itk promotes T helper 2 differentiation via negative regulation of T-bet. Immunity. 2004;21:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt U, B N, Unger B, Ellmeier W. The role of Tec family kinases in myeloid cells. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2004;134:65–78. doi: 10.1159/000078339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colgan J, Asmal M, Neagu M, Yu B, Schneidkraut J, Lee Y, Sokolskaja E, Andreotti A, Luban J. Cyclophilin A regulates TCR signal strength in CD4+ T cells via a proline-directed conformational switch in Itk. Immunity. 2004;21:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andreotti AH, B S, Feng S, Berg LJ, Schreiber SL. Regulatory intramolecular association in a tyrosine kinase of the Tec family. Nature. 1997;385:93–97. doi: 10.1038/385093a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bunnell SC. Biochemical interactions integrating Itk with the T cell receptor-initiated signaling cascade. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2219–2230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamorro M. Requirements for activation and RAFT localization of the T-lymphocyte kinase Rlk/Txk. BMC Immunol. 2001;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brazin KN, Mallis RJ, Fulton DB, A H. Andreotti. Regulation of the tyrosine kinase Itk by the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase cyclophilin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1899–1904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042529199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg LJ, F L, Lucas JA, Schwartzberg PL. Tec family kinases in T lymphocyte development and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:549–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang WC, Ching KA, Tsoukas CD, Berg LJ. Tec Kinase Signaling in T Cells Is Regulated by Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase and the Tec Pleckstrin Homology Domain. J Immunol. 2001;166:387–395. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer A, Mercer J, Iyer A, Ragin M, August A. Regulation of CXC chemokine receptor 4-mediated migration by the Tec family tyrosine kinase ITK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29816–29820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sahu N, M C, Fischer A, August A. Differential sensitivity to Itk kinase signals for T helper 2 cytokine production and chemokine-mediated migration. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180:3833–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takesono A, H R, Mandai M, Dombroski D, Schwartzberg PL. Requirement for Tec kinases in chemokine-induced migration and activation of Cdc42 and Rac. Curr Biol. 2004;14:917. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang YH, Grasis JA, Miller AT, Xu R, Soonthornvacharin S, Andreotti AH, Tsoukas CD, Cooke MP, Sauer K. Positive regulation of Itk PH domain function by soluble IP4. Science. 2007;316:886–889. doi: 10.1126/science.1138684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qi Q, S N, August A. Tec kinase Itk forms membrane clusters specifically in the vicinity of recruiting receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:38529–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shan X. Deficiency of PTEN in Jurkat T cells causes constitutive localization of Itk to the plasma membrane and hyperresponsiveness to CD3 stimulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6945–6957. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6945-6957.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomlinson MG, Heath VL, Turck CW, Watson SP, Weiss A. SHIP family inositol phosphatases interact with and negatively regulate the Tec tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55089–55096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hao S, Qi Q, Hu J, August A. A kinase independent function for Tec kinase ITK in regulating antigen receptor induced serum response factor activation. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2691–2697. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joseph RE, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. Mechanism and functional significance of Itk autophosphorylation. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:1281–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nore BF, M P, Antonsson P, Bäckesjö CM, Westlund A, Lennartsson J, Hansson H, Löw P, Rönnstrand L, Smith CI. Identification of phosphorylation sites within the SH3 domains of Tec family tyrosine kinases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2003;1645:123–32. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilcox H, Berg L. Itk phosphorylation sites are required for functional activity in primary T cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37112–37121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304811200. Epub 32003 Jul 37113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bunnell SC, H P, Kolluri R, Kirchhausen T, Rickles RJ, Berg LJ. Identification of Itk/Tsk Src homology 3 domain ligands. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:25646–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brazin KN, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. A specific intermolecular association between the regulatory domains of a Tec family kinase. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:607–623. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mallis RJ, Brazin KN, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. Structural characterization of a proline-driven conformational switch within the Itk SH2 domain. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:900–905. doi: 10.1038/nsb864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laederach A, Cradic KW, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. Determinants of intra versus intermolecular self-association within the regulatory domains of Rlk and Itk. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00531-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breheny PJ, Laederach A, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. Ligand specificity modulated by prolyl imide bond Cis/Trans isomerization in the Itk SH2 domain: a quantitative NMR study. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15706–15707. doi: 10.1021/ja0375380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pletneva EV, Sundd M, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. Molecular details of Itk activation by prolyl isomerization and phospholigand binding: the NMR structure of the Itk SH2 domain bound to a phosphopeptide. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:550–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Severin A, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. Murine Itk SH3 domain. J Biomol NMR. 2008;40:285–290. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9231-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Severin A, Joseph RE, Boyken S, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. Proline isomerization preorganizes the Itk SH2 domain for binding to the Itk SH3 domain. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:726–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joseph RE, Min L, Andreotti AH. The linker between SH2 and kinase domains positively regulates catalysis of the Tec family kinases. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5455–5462. doi: 10.1021/bi602512e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown K, Long JM, Vial SC, Dedi N, Dunster NJ, Renwick SB, Tanner AJ, Frantz JD, Fleming MA, Cheetham GM. Crystal structures of interleukin-2 tyrosine kinase and their implications for the design of selective inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18727–18732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.August A, Gibson S, Kawakami Y, Kawakami T, Mills G, Dupont B. CD28 is associated with and induces the immediate tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of the Tec family kinase ITK/EMT in the human Jurkat leukemic T-cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9347–9351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibson S, August A, Branch D, Dupont B, Mills G. Functional LCK Is required for optimal CD28-mediated activation of the TEC family tyrosine kinase EMT/ITK. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7079–7083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gibson S, T K, Lu Y, Lapushin R, Khan H, Imboden JB, Mills GB. Efficient CD28 signaling leads to increases in the kinase activities of the TEC family tyrosine kinase EMT/ITK/TSK and the SRC family tyrosine kinase LCK. The Biochemical Journal. 1998;330:1123–1128. doi: 10.1042/bj3301123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gibson S, August A, Kawakami Y, Kawakami T, Dupont B, Mills GB. The EMT/ITK/TSK (EMT) tyrosine kinase is activated during TCR signaling: LCK is required for optimal activation of EMT. J Immunol. 1996;156:2716–2722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibson S, August A, Branch D, Dupont B, Mills GM. Functional LCK Is required for optimal CD28-mediated activation of the TEC family tyrosine kinase EMT/ITK. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7079–7083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.King P, Sadra A, Han A, Liu X, Sunder-Plassmann R, Reinherz E, Dupont B. CD2 signaling in T cells involves tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of the Tec family kinase, EMT/ITK/TSK. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1707–1714. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.11.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawakami Y, Yao L, Tashiro M, Gibson S, Mills G, Kawakami T. Activation and interaction with protein kinase C of a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase, Itk/Tsk/Emt, on Fc epsilon RI cross-linking on mast cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:3556–3562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu KQ, Bunnell SC, Gurniak CB, Berg LJ. T cell receptor-initiated calcium release is uncoupled from capacitative calcium entry in Itk-deficient T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1721–1727. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grasis J, Browne C, Tsoukas C. Inducible T cell tyrosine kinase regulates actin-dependent cytoskeletal events induced by the T cell antigen receptor. J Immunol. 2003;170:3971–3976. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Labno CM, Lewis CM, You D, Leung DW, Takesono A, Kamberos N, Seth A, Finkelstein LD, Rosen MK, Schwartzberg PL, Burkhardt JK. Itk functions to control actin polymerization at the immune synapse through localized activation of Cdc42 and WASP. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1619–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woods ML, Kivens WJ, Adelsman MA, Qiu Y, August A, Shimizu Y. A novel function for the Tec family tyrosine kinase Itk in activation of beta 1 integrins by the T-cell receptor. EMBO J. 2001;20:1232–1244. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller AT, Berg LJ. Defective Fas ligand expression and activation-induced cell death in the absence of IL-2-inducible T cell kinase. J Immunol. 2002;168:2163–2172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schaeffer EM. Requirement for Tec kinases Rlk and Itk in T cell receptor signaling and immunity. Science. 1999;284:638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.August A, Sadra A, Dupont B, Hanafusa H. Src-induced activation of inducible T cell kinase (ITK) requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity and the Pleckstrin homology domain of inducible T cell kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11227–11232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scharenberg AM, Kinet JP. PtdIns-3,4,5-P3: a regulatory nexus between tyrosine kinases and sustained calcium signals. Cell. 1998;94:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fluckiger AC, Li Z, Kato RM, Wahl MI, Ochs HD, Longnecker R, Kinet JP, Witte ON, Scharenberg AM, Rawlings DJ. Btk/Tec kinases regulate sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+ following B-cell receptor activation. EMBO J. 1998;17:1973–1985. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Su YW, Zhang Y, Schweikert J, Koretzky GA, Reth M, Wienands J. Interaction of SLP adaptors with the SH2 domain of Tec family kinases. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3702–3711. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3702::AID-IMMU3702>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ching KA, Grasis JA, Tailor P, Kawakami Y, Kawakami T, Tsoukas CD. TCR/CD3-Induced activation and binding of Emt/Itk to linker of activated T cell complexes: requirement for the Src homology 2 domain. J Immunol. 2000;165:256–262. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shan X, Wange RL. Itk/Emt/Tsk activation in response to CD3 cross-linking in Jurkat T cells requires ZAP-70 and Lat and is independent of membrane recruitment. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29323–29330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takata M, Kurosaki T. A role for Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cell antigen receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase C-gamma 2. J Exp Med. 1996;184:31–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bogin Y, A C, Beach D, Yablonski D. SLP-76 mediates and maintains activation of the Tec family kinase ITK via the T cell antigen receptor-induced association between SLP-76 and ITK. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:6638–6643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609771104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schaeffer E. Mutation of Tec family kinases alters T helper cell differentiation. Nature Immunol. 2001;2:1183–1188. doi: 10.1038/ni734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fowell D, Shinkai K, Liao X, Beebe A, Coffman R, Littman D, Locksley R. Impaired NFATc Translocation and Failure of Th2 Development in Itk Deficient CD4 T Cells. Immunity. 1999;11:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dombroski D, Houghtling RA, Labno CM, Precht P, Takesono A, Caplen NJ, Billadeau DD, Wange RL, Burkhardt JK, Schwartzberg PL. Kinase-independent functions for Itk in TCR-induced regulation of Vav and the actin cytoskeleton. J Immunol. 2005;174:1385–1392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reynolds LF, Smyth LA, Norton T, Freshney N, Downward J, Kioussis D, Tybulewicz VL. Vav1 transduces T cell receptor signals to the activation of phospholipase C-gamma1 via phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent and -independent pathways. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1103–1114. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Finkelstein LD, Schwartzberg PL. Tec kinases: shaping T-cell activation through actin. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li CR, Berg LJ. Itk is not essential for CD28 signaling in naive T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:4475–4479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hata D, Kawakami Y, Inagaki N, Lantz CS, Kitamura T, Khan WN, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Miura T, Han W, Hartman SE, Yao L, Nagai H, Goldfeld AE, Alt FW, Galli SJ, Witte ON, Kawakami T. Involvement of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in FcepsilonRI-dependent mast cell degranulation and cytokine production. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1235–1247. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fowell DJ. Impaired NFATc translocation and failure of TH2 development in Itk-deficient CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1999;11:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schwartzberg PL, Finkelstein LD, Readinger JA. TEC-family kinases: regulators of T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:284–295. doi: 10.1038/nri1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dubois S, Waldmann TA, Muller JR. ITK and IL-15 support two distinct subsets of CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12075–12080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605212103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Berg LJ. Signalling through TEC kinases regulates conventional versus innate CD8(+) T-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:479–485. doi: 10.1038/nri2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Broussard C, Fleischacker C, Horai R, Chetana M, Venegas AM, Sharp LL, Hedrick SM, Fowlkes BJ, Schwartzberg PL. Altered development of CD8+ T cell lineages in mice deficient for the Tec kinases Itk and Rlk. Immunity. 2006;25:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Prince AL, Yin CC, Enos ME, Felices M, Berg LJ. The Tec kinases Itk and Rlk regulate conventional versus innate T-cell development. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:115–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Atherly LO, Lucas JA, Felices M, Yin CC, Reiner SL, Berg LJ. The Tec family tyrosine kinases Itk and Rlk regulate the development of conventional CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2006;25:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hu J, August A. Naive and innate memory phenotype CD4+ T cells have different requirements for active Itk for their development. J Immunol. 2008;180:6544–6552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hu J, Sahu N, Walsh E, August A. Memory phenotype CD8+ T cells with innate function selectively develop in the absence of active Itk. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2892–2899. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ragin M, Hu J, Henderson A, August A. Aa role for the Tec family kinase ITK in regulating SEB induced Interleukin-2 production in vivo via c-jun phosphorylation. BMC Immunol. 2005;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Horai R, Mueller KL, Handon RA, Cannons JL, Anderson SM, Kirby MR, Schwartzberg PL. Requirements for selection of conventional and innate T lymphocyte lineages. Immunity. 2007;27:775–785. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Readinger JA, Mueller KL, Venegas AM, Horai R, Schwartzberg PL. Tec kinases regulate T-lymphocyte development and function: new insights into the roles of Itk and Rlk/Txk. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:93–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00757.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Raberger J, Schebesta A, Sakaguchi S, Boucheron N, Blomberg K, Berglöf A, Kolbe T, Smith C, Rülicke T, Ellmeier W. The transcriptional regulator PLZF induces the development of CD44 high memory phenotype T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17919–17924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805733105. Epub 12008 Nov 17912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gadue P, Stein P. NK T cell precursors exhibit differential cytokine regulation and require Itk for efficient maturation. J Immunol. 2002;169:2397–2406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Felices M, Yin CC, Kosaka Y, Kang J, Berg LJ. Tec kinase Itk in {gamma}{delta}T cells is pivotal for controlling IgE production in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808459106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Qi Q, Xia M, Hu J, Hicks E, Iyer A, Xiong N, August A. Enhanced development of CD4+ gamma delta T cells in the absence of Itk results in elevated IgE production. Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196345. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Peng SL, Glimcher LH. Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Th1 Immune Responses. Annual Review of Immunology. 2003;21:713–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mowen KA, Glimcher LH. Signaling pathways in Th2 development. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:203–222. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang ZE, Reiner SL, Zheng S, Dalton DK, Locksley RM. CD4+ effector cells default to the Th2 pathway in interferon gamma-deficient mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1367–1371. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-gamma receptor. Science. 1993;259:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.8456301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–2247. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Muller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LF, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Young HA, Hardy KJ. Role of interferon-gamma in immune cell regulation. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:373–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Neurath MF, Finotto S, Glimcher LH. The role of Th1/Th2 polarization in mucosal immunity. Nat Med. 2002;8:567–573. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lafaille JJ. The role of helper T cell subsets in autoimmune diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998;9:139–151. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]