Abstract

Vibrio cholerae is the etiologic agent of cholera in humans. Intestinal colonization occurs in a stepwise fashion, initiating with attachment to the small intestinal epithelium. This attachment is followed by expression of the toxin-coregulated pilus, microcolony formation, and cholera toxin (CT) production. We have recently characterized a secreted attachment factor, GlcNAc binding protein A (GbpA), which functions in attachment to environmental chitin sources as well as to intestinal substrates. Studies have been initiated to define the regulatory network involved in GbpA induction. At low cell density, GbpA was detected in the culture supernatant of all wild-type (WT) strains examined. In contrast, at high cell density, GbpA was undetectable in strains that produce HapR, the central regulator of the cell density-dependent quorum-sensing system of V. cholerae. HapR represses the expression of genes encoding regulators involved in V. cholerae virulence and activates the expression of genes encoding the secreted proteases HapA and PrtV. We show here that GbpA is degraded by HapA and PrtV in a time-dependent fashion. Consistent with this, ΔhapA ΔprtV strains attach to chitin beads more efficiently than either the WT or a ΔhapA ΔprtV ΔgbpA strain. These results suggest a model in which GbpA levels fluctuate in concert with the bacterial production of proteases in response to quorum-sensing signals. This could provide a mechanism for GbpA-mediated attachment to, and detachment from, surfaces in response to environmental cues.

Vibrio cholerae has adapted to lifestyles in dual environments, allowing survival in aquatic locations, as well as the ability to colonize the epithelium of the human small intestine. This intestinal colonization by V. cholerae is a prerequisite for the disease cholera in humans. Intestinal colonization proceeds in a stepwise manner, initiating with attachment to the epithelial cell layer by multiple attachment factors (26). This stable attachment localizes the bacterium in an environment conducive for activation of subsequent virulence factors, including the toxin-coregulated pilus, a type IVb pilus that mediates cell-cell interactions and microcolony formation (27). Cholera toxin (CT) is produced and extracellularly secreted by bacteria within the microcolonies and enters into intestinal epithelial cells. CT causes the disruption of fluid and electrolyte balance and results in the voluminous rice water diarrhea characteristically observed with cholera patients.

The ability of V. cholerae to bind to surfaces is crucial for the initial stages of colonization of both the aquatic and intestinal environments. Previous studies observing V. cholerae in the aquatic setting identified the ability of the bacteria to attach to zooplankton and phytoplankton, binding to surface structures that include chitin as a major component (7, 10, 11, 19, 21, 42). Chitin, a polymer consisting primarily of a β-1,4 linkage of GlcNAc monomers, is the most abundant aquatic carbon source and, when presented on the surfaces of zooplankton, aquatic exoskeletons, algae, and plants, provides a substrate for V. cholerae surface binding (8, 19-22). V. cholerae is able to break down chitin into carbon to use as a nutrient source via degradation by secreted chitinases (12). We have described a protein, GbpA (GlcNAc binding protein A), which facilitates the binding of V. cholerae to chitin, specifically to the chitin monomer GlcNAc, a sugar residue that is also found on the surface of epithelial cells (3, 16, 26). GbpA mediates binding to chitin, GlcNAc, and exoskeletons of Daphnia magna, as well as participates in effective intestinal colonization within the infant mouse model of cholera (26). GbpA is a secreted protein that exits the cell via the type 2 secretion system by which it mediates attachment by a yet uncharacterized mechanism (26). Previous studies examining the role of GbpA in binding to surfaces have been conducted utilizing various wild-type (WT) strains of V. cholerae, specifically O395 (26) and N16961 (33). These strains both are of the O1 serogroup but are differentially classified as classical (43) and El Tor biotypes (18), respectively. The classical biotype was responsible for the first six pandemics of cholera, whereas El Tor is the cause of the current pandemic (39).

Quorum sensing regulates multiple bacterial processes, including virulence, formation of biofilms, and bioluminescence (25, 35, 36). In contrast to many other bacterial quorum-sensing systems, virulence gene expression and biofilm formation in V. cholerae is expressed under conditions of low cell density and repressed at high cell density (17, 35, 48). HapR, a member of the TetR family of regulatory proteins, is a central regulator on which the three parallel inputs of the V. cholerae quorum-sensing system converge (30, 35). During low-cell-density conditions, characteristic of growth within the aquatic environment or stages of early intestinal colonization, the quorum-sensing system is not engaged. Under conditions of high cell density, bacterial numbers and secreted autoinducer molecules are increased to a level that triggers the V. cholerae quorum-sensing system.

HapR regulates gene function in two ways, serving as both an activator and repressor. At high cell density, HapR functions in the capacity of a repressor of the toxin-coregulated pilus and CT virulence cascade (29, 31) as well as a repressor of vps gene expression (17), preventing biofilm formation. In addition to repressing gene expression, at high cell density HapR activates the expression of genes encoding extracellularly secreted proteases HapA and PrtV (14, 17, 23, 45-47). HapA, also referred to as hemagglutinin/protease (HA/P), was first reported as a mucinase by Burnet (6) and later characterized as a zinc- and calcium-dependent metalloprotease (4). Extracellularly secreted via the V. cholerae type 2 secretion pathway (40), HA/P has been demonstrated to cleave fibronectin, lactoferrin, and mucin (15), as well as to participate in the activation of the CT A subunit (5). Further studies have led to the suggestion that HA/P is a detachase, critical for the release of V. cholerae from the surface of intestinal cells (2, 14, 38). PrtV is a second protease encoded by a gene that is activated by HapR (47). It has been demonstrated to be essential for both V. cholerae killing of Caenorhabditis elegans, as well as protecting V. cholerae from predator grazing by various flagellates (32, 45).

The data presented here indicate that HapA and PrtV participate in the targeted degradation of the attachment factor GbpA. We demonstrate that GbpA is present during the logarithmic phase of growth and conditions of low cell density but that it is not present in the supernatant of high-cell-density cultures of strains that express functional HapR. Further studies revealed that during stages of high cell density, proteases HapA and PrtV, encoded by HapR-activated genes, are responsible for GbpA degradation in the culture supernatant. These findings suggest that the attachment factor GbpA is potentially a ligand targeted for protease degradation during the epithelial detachment process. This process could aid in the release of V. cholerae back into the aquatic environment following late stages of intestinal colonization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains utilized in this study are described in Table 1. All strains were grown in aerated LB broth at 37°C. When necessary, cultures were supplemented with 2.5 or 5 mM GlcNAc (Sigma) for optimal GbpA expression (33) and 0.02% arabinose (Sigma) to induce expression of genes inserted into pBAD-TOPO. Strains cultivated on solid medium were grown on 1.5% LB agar supplemented with antibiotics, when appropriate. Bacterial cultures (16 h) were diluted 1:100 into fresh media at the time zero (T = 0) time point of the time course assays. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: streptomycin, 100 μg/ml; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; and kanamycin, 45 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids utilized in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Description/relevant genotypea | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae strains | ||

| O395 | Classical, Ogawa, Smr | 43 |

| C6706 Str2 | El Tor, Inaba, Smr | 44 |

| N16961 | El Tor, Inaba, Smr | 37 |

| KSK1789 | C6706 ΔhapR, Smr | 29 |

| BAJ2 | O395 ΔlacZ ΔgbpA::lacZ, Smr | 26 |

| BAJ21 | C6706 ΔlacZ ΔgbpA::lacZ, Smr | This study |

| BAJ118 | C6706 ΔlacZ ΔgbpA::lacZ ΔhapR, Smr | This study |

| BAJ332 | C6706 ΔprtV, Smr | This study |

| BAJ334 | C6706 ΔhapA, Smr | This study |

| BAJ338 | C6706 ΔhapA ΔprtV, Smr | This study |

| BAJ380 | C6706 ΔlacZ ΔgbpA::lacZ ΔprtV, Smr | This study |

| BAJ382 | C6706 ΔlacZ ΔgbpA::lacZ ΔhapA, Smr | This study |

| BAJ383 | C6706 ΔlacZ ΔgbpA::lacZ ΔhapA ΔprtV, Smr | This study |

| GK999 | N16961 HapRC6706, Smr | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| S17-1λpir | thi pro recA hsdR [RP4-2 Tc:Mu-Km::Tn7] λpir Tpr Smr | 13 |

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Smr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD-TOPO | Expression vector, PBAD promoter | Invitrogen |

| pKAS154 | Allelic exchange vector | 28 |

| pBro65 | pKAS154 ΔhapA, Kmr | This study |

| pBro63 | pKAS154 ΔprtV, Kmr | This study |

| pBro60 | pBAD-TOPO hapA, Apr | This study |

| pBro62 | pBAD-TOPO prtV, Apr | This study |

| pKAS187 | ΔhapR | 29 |

| pGKK288 | HapRC6706 | This study |

Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Smr, streptomycin resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance; Tpr, trimethoprim resistance.

Strain construction.

In-frame deletions of genes of interest were constructed using the plasmids listed in Table 1. PCR was used to amplify two approximately 500-base-pair fragments flanking the gene of interest and to introduce restriction sites for cloning purposes. Fragments were cloned into restriction-digested pKAS154 using a three-fragment ligation. Escherichia coli S17-1λpir harboring each plasmid was mated with C6706 Str2, and allelic exchange was carried out as described previously (41). Expression plasmids were constructed using PCR amplification and then cloned into the vector pBAD-TOPO (Invitrogen).

Western blotting analysis.

Bacterial cultures were grown as described, and samples were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 minutes to pellet bacteria. Culture supernatants were collected and passed though a 0.2-μm filter (Millipore). Equal volumes of culture supernatant samples were added to an appropriate volume of 4× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis loading buffer (1) boiled for 5 min, and proteins were separated on a 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-containing polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose at 4°C using a wet-transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad) and glycine buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol). Primary anti-GbpA antiserum (26) was utilized at a dilution of 1:1,000. Goat anti-rabbit secondary antiserum (Cappel) was applied at a dilution of 1:100,000. Immunodetection was achieved via use of chemiluminescent detection reagents (Amersham). Densitometry of bands was calculated using ImageJ (NIH), and results were graphed using Prism (GraphPad).

Chitin bead binding assay.

Strains were grown for 18 h at 37°C. Magnetic chitin beads (New England BioLabs) were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The beads were mixed with an equal volume of culture and rotated at 37°C for 30 min. The supernatant was removed by applying the mixture tube to a magnetic rack (Invitrogen), and 1 ml of PBS was added to the beads. The tube was inverted gently four to six times and then applied to the magnet in order to pipette away the unbound bacteria. This was repeated a total of three times. A total of 1 ml of PBS and 0.2 g of 0.5-mm glass beads were added to the washed chitin beads and vortexed for 60 s at high speed to remove bound bacteria. The resulting bacterial suspension was serially diluted and plated for enumeration. The adherence index was calculated by dividing the output by the input numbers of CFU/ml (output/input).

Casein hydrolysis assay.

Protease production was evaluated by hydrolysis of casein (milk) in plates. Strains were grown at 37°C on plates containing 18.4% brain-heart infusion (Difco), 3% agar (Difco-BD), and 4% nonfat evaporated milk (Carnation). The level of secreted protease activity was estimated by examination of zones of clearance surrounding bacterial growth.

β-Galactosidase assays.

Experiments measuring the transcriptional activation of V. cholerae lacZ fusions were carried out as previously described (34).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression of HapR results in the loss of GbpA.

In order to determine whether GbpA is a generalized attachment factor for V. cholerae, we examined the high-cell-density culture supernatant of several WT strains grown for 16 h for the presence and levels of GbpA. Western blotting analysis of the culture supernatants with anti-GbpA antisera revealed that GbpA was present in the classical biotype strain O395 but not in the El Tor biotype strain C6706 (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, when we examined N16961, another El Tor biotype strain, we found that GbpA was present (Fig. 1B). Although belonging to different biotypes, O395 and N16961 both have frameshift mutations in the coding sequence of hapR. The frameshift introduces a premature stop codon at residues 68 and 79, respectively (24), resulting in truncated, nonfunctional proteins and a loss in the ability of these strains to respond to changes in surrounding cell density (48). In contrast, C6706 encodes a full-length HapR protein. To determine if the lack of GbpA detected in the C6706 strain was a consequence of its HapR status, we examined an isogenic C6076 ΔhapR strain for the presence of GbpA in the culture supernatant. GbpA was detected in the culture supernatant of the C6706 ΔhapR strain at levels comparable to that observed for N16961 (Fig. 1A and B). Additionally, when the hapR mutant of N16961 was replaced with a WT allele at its native locus, GbpA was no longer detected in the culture supernatant (Fig. 1B). Although the levels of GbpA expressed by the El Tor biotype never reached those observed for the O395 classical biotype, we speculate that this is due to additional regulatory factors that are distinct between these two biotypes. These results link the presence of HapR and the resulting functional quorum-sensing system with a loss of GbpA in the culture supernatant at high cell density.

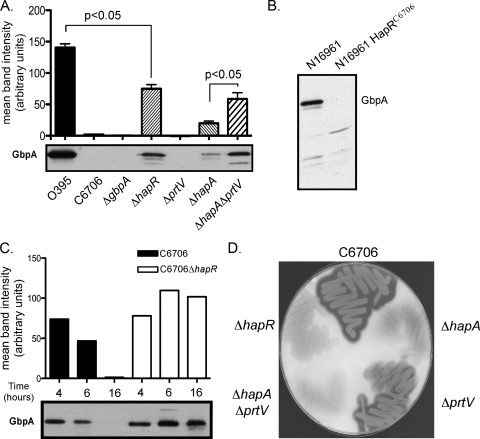

FIG. 1.

GbpA levels in culture supernatants correlate with the presence or absence of proteases encoded by HapR-activated genes. Representative Western blots of culture supernatants probed with anti-GbpA antiserum for a panel of strains. (A) From left to right: O395, C6706, C6706 ΔgbpA, C6706 ΔhapR, C6706 ΔprtV, C6706 ΔhapA, and C6706 ΔhapA ΔprtV. GbpA levels were quantified by performing densitometry of the bands detected by Western blotting. The histogram above the blot depicts the mean intensity of the bands observed in individual lanes, with each bar corresponding to the band located directly below. Paired Student's t tests were used for statistical analysis. (B) Western blot of culture supernatant probed with anti-GbpA antiserum for strains N16961 and N16961 HapRC6706. (C) GbpA levels are reduced in a time-dependent fashion when proteases encoded by HapR-activated genes are present. Representative Western blot of culture supernatants probed with anti-GbpA antiserum that were obtained at time points of 4, 6, and 16 h postinoculation for C6706 and C6706 ΔhapR. GbpA levels were quantified by performing densitometry of bands detected by Western blotting. Histogram above the blot depicts the mean intensity of the bands observed in individual lanes, with each bar corresponding to the band located directly below. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments. (D) Casein plate showing protease production as indicated by zones of clearing around cell growth.

GbpA is present at low cell density.

Due to the role of HapR in cell density-dependent gene regulation, we next examined whether C6706 produces GbpA under low-cell-density conditions when HapR levels are low. Samples of C6706 culture supernatants were obtained at intervals ranging from low to high cell density. We observed that at early time points, specifically at 4 and 6 h, GbpA was present in the C6706 culture supernatant (Fig. 1C). However, the levels of GbpA in the culture supernatant by 16 h were undetectable. In contrast, the levels of GbpA in the supernatant of the C6706 ΔhapR strain remained similar over time. These results indicate that C6706 produces GbpA during its early phase of growth and that its loss is dependent on the HapR regulatory effects that occur at high cell density.

GbpA loss at high cell density is due to protease degradation.

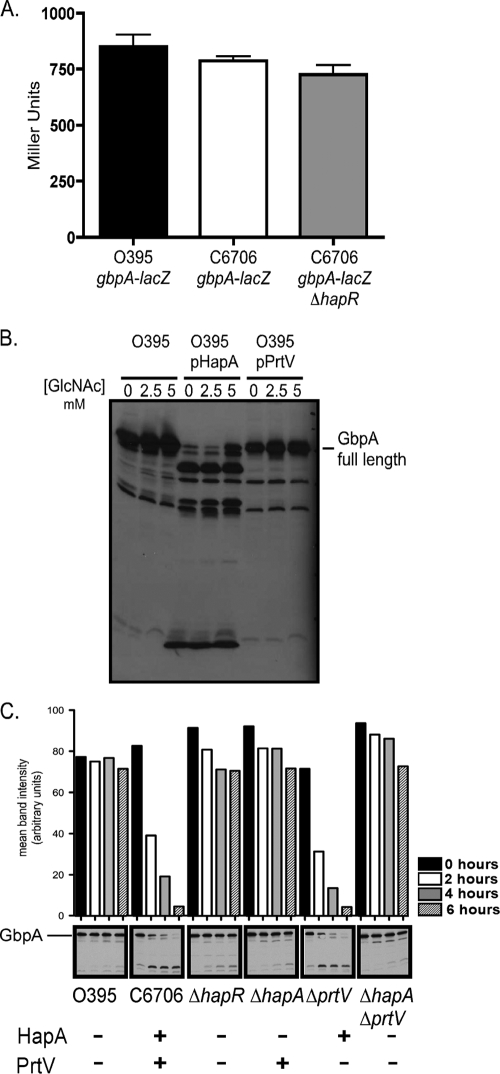

To test whether HapR directly regulates gbpA expression, we utilized a series of gbpA-lacZ fusions to measure transcriptional levels. We observed no change in the transcription of gbpA in ΔhapR strains compared to the C6706 WT at any cell density or in various growth and induction conditions (Fig. 2A). These results suggested that it was unlikely that HapR functions to repress gbpA at the level of transcription. This led us to hypothesize that extracellularly secreted proteases HapA and PrtV, which are encoded by HapR-activated genes, might degrade GbpA in the culture supernatant under conditions of high cell density.

FIG. 2.

GbpA loss at high cell density is due to protease degradation. (A) Overnight cultures of O395 ΔgbpA-lacZ, C6706 ΔgbpA-lacZ, and C6706 ΔgbpA-lacZ ΔhapR were assayed for β-galactosidase production. (B) Immunoblot of culture supernatants probed with anti-GbpA antiserum for strains O395, O395 + pHapA, and O395 + pPrtV, with 0, 2.5, or 5 mM of GlcNAc added for increased GpbA induction. (C) Supernatants containing proteases encoded by HapR-activated genes are sufficient for GbpA degradation. A high-cell-density culture supernatant from O395 containing GbpA was collected, filtered to remove bacterial cells, mixed with high-cell-density filtered culture supernatants from C6706 strains with different protease secretion profiles, and incubated at 37°C. Samples of the mixed supernatants were removed at time points of 0, 2, 4, and 6 h. GbpA levels were detected in the various samples via Western blotting with anti-GbpA antiserum and quantified by performing densitometry. The histogram above the blot depicts the mean intensity of the bands observed in individual lanes, with each bar corresponding to the band located directly below it. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

To test whether GbpA is specifically degraded by proteases produced at high cell density, we constructed in-frame deletions of hapA, prtV, or both in the C6706 background. Loss of protease production was evaluated by growth of strains on casein plates and examination of zones of clearance (Fig. 1D). Deletion of hapA resulted in a decreased zone of clearance on a casein plate compared to that produced by the WT strain. In contrast, the prtV mutant produced a zone of clearance that was not significantly decreased compared to that of the WT, indicating that PrtV may be expressed at lower levels or is less active on casein than HapA. However, the ΔhapA ΔprtV double mutant produced almost no zone of clearance, similar to the ΔhapR strain.

Analysis of high-cell-density culture supernatants with anti-GbpA antisera revealed a partial restoration of GbpA levels in the ΔhapA mutant (Fig. 1A). Loss of prtV alone did not significantly restore GbpA under these conditions, consistent with the observations with the casein plates. However, GbpA was restored in the ΔhapA ΔprtV double mutant to levels similar to those of the ΔhapR mutant, with more GbpA present in these strains than in either of the single protease gene deletion strains (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that both HapA and PrtV contribute to the degradation of GbpA in V. cholerae.

The degradation of GbpA by HapA and PrtV was also examined with the O395 background by expressing these proteins from an inducible promoter (Fig. 2B). Analysis of overnight culture supernatants of the O395 strain overexpressing HapA revealed that the full-length form of GbpA had been degraded into several smaller products recognized by anti-GbpA antisera. The O395 strain overexpressing PrtV showed a more subtle effect, only slightly reducing the levels of GbpA compared to the WT. These findings are consistent with those described above for the C6706 background, in which HapA appears to have a stronger influence on GbpA degradation than PrtV (Fig. 1A).

We next tested whether supernatants containing proteases encoded by HapR-activated genes are sufficient for GbpA degradation. To do this, an in vitro assay was developed whereby a supernatant from O395 containing high levels of GbpA was incubated with supernatants from WT C6706 and various mutant derivatives, the ΔhapR ΔgbpA, ΔhapA ΔgbpA, ΔprtV ΔgbpA, and ΔhapA ΔprtVΔgbpA strains. All strains were grown to high cell density. Supernatants obtained from all strains were filtered to remove contaminating bacteria and prevent the possibility of bacterial growth and de novo protease production during the assay. Supernatants were mixed and incubated. When the WT C6706 supernatant was mixed with a GbpA-containing supernatant, we observed GbpA degradation in a time-dependent fashion (Fig. 2C), similar to the results observed in vivo (Fig. 1A and C). When the GbpA-containing supernatant was incubated with a supernatant from a strain lacking HapA protease, GbpA remained present at stable levels throughout the duration of the experiment (Fig. 2C). Although no clear role for PrtV-mediated degradation was observed in this in vitro analysis, full degradation of GbpA appears to require PrtV during bacterial growth (Fig. 1A). These results suggest that proteases encoded by HapR-activated genes present in the culture supernatants are responsible for the degradation of GbpA. However, it cannot be ruled out that the target of these proteases is not GbpA directly but another intermediate protein, which itself cleaves GbpA.

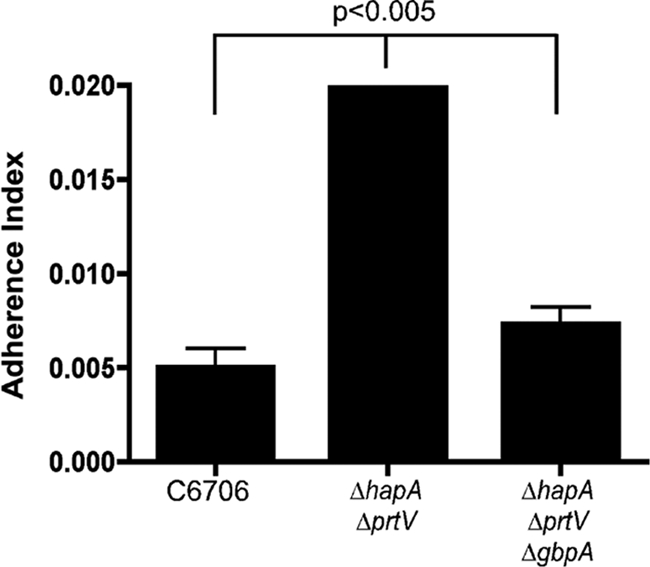

Finally, we examined the ability of C6706 strains to bind to chitin beads following high-cell-density growth. WT, ΔhapA ΔprtV, and ΔhapA ΔprtVΔgbpA strains were cultured for 18 h to high cell density. The cultures were then incubated with chitin beads, unbound bacteria were washed away, and the number of bound bacteria recovered from the beads was quantified. Under these conditions, approximately four times more ΔhapA ΔprtV bacteria were bound to the beads than were WT bacteria (Fig. 3). This enhanced attachment of the double ΔhapA ΔprtV mutant strain to the chitin beads is mediated by GbpA, since the ΔhapA ΔprtV ΔgbpA triple mutant appeared similar to the WT.

FIG. 3.

HapR-regulated proteases influence attachment to chitin surfaces. High-cell-density cultures of the C6706 WT, ΔhapA ΔprtV, and ΔhapA ΔprtV ΔgbpA strains were incubated with magnetic chitin beads. After unbound bacteria were washed away, the number of bound bacteria recovered from the beads was quantified. Paired Student's t tests were used for statistical analysis.

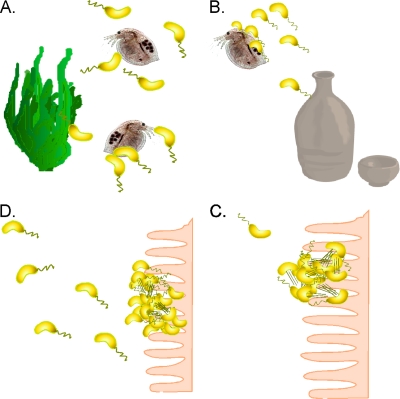

The protease-mediated degradation of GbpA by HapA and PrtV may provide a mechanism that enhances bacterial release from surfaces when the localized bacterial cell density is high (Fig. 4), as evidenced by the chitin bead binding assays. V. cholerae in the aquatic environment persists as both planktonic and surface-attached populations (Fig. 4A). V. cholerae cells are often ingested while attached to aquatic substrates (Fig. 4B) (9). Upon ingestion, planktonic bacteria swim toward sites of colonization, where additional secretion of GbpA would provide a ligand for attachment to epithelial cell surfaces (Fig. 4C). Following replication and virulence factor production in the host intestine, local cell density increases. This induces the quorum-sensing system, and the resulting degradation of GbpA by HapA and PrtV, which would facilitate release of the bacteria from the epithelial surface and expedite their return to the aquatic environment (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Cyclic transition of V. cholerae between the aquatic habitat and the human small intestine. (A) V. cholerae organisms persist in the aquatic environment as free-swimming, planktonic bacteria as well as bacteria bound to biotic and abiotic surfaces. (B) Ingestion of V. cholerae via contaminated food and water localize the bacteria to the small intestine. (C) Bacterial attachment to the epithelial surface is followed by virulence factor production, leading to sites of colonization from which CT is secreted, causing typical cholera symptoms. (D) Due to high localized cell density, the quorum-sensing system is activated. This leads to the repression of the expression of genes encoding virulence factors as well as activation of the expression of genes encoding secreted proteases that function to degrade attachment factors, such as GbpA, detaching bacteria to be released back into the aquatic environment.

Although the presence of a functional quorum-sensing system is not essential for the process of intestinal colonization, it may prove to be important for enhancing the V. cholerae transition between the host and the aquatic environment. This may provide an evolutionary advantage for C6706 over strains such as O395 and N16961, in which GbpA is present at all stages of growth and cell density. In these strains, GbpA may be able to facilitate colonization to surfaces but may not efficiently release from those surfaces.

In conclusion, this study has identified a novel cell density-dependent mechanism for regulating the presence of an attachment factor of V. cholerae. Although HapA has previously been hypothesized to be a detachase critical for the release of V. cholerae from the surface of intestinal cells (2, 14, 38), its precise target has remained unknown. The finding here, that GbpA is degraded by both HapA and PrtV, provides at least one attachment-specific role for these proteases. We are currently investigating the mechanism by which GbpA mediates attachment to surfaces. However, GbpA is not the sole attachment factor involved in V. cholerae binding to surfaces. It has previously been shown that loss of GbpA does not completely abolish V. cholerae binding to substrates either in vivo or in vitro (26). Thus, additional attachment factors not yet characterized may also serve as targets of HapA- and PrtV-mediated degradation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabriela Kovacikova and Binata Ray for the construction of strain GK999.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI025096 and AI039654 to R.K.T. and AI041558 to K.S. B.A.J. and R.M.M. were supported by training grants AI007363 and GM008704, respectively.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 September 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates and J. Wiley, New York, NY.

- 2.Benitez, J. A., R. G. Spelbrink, A. Silva, T. E. Phillips, C. M. Stanley, M. Boesman-Finkelstein, and R. A. Finkelstein. 1997. Adherence of Vibrio cholerae to cultured differentiated human intestinal cells: an in vitro colonization model. Infect. Immun. 65:3474-3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjork, S., M. E. Breimer, G. C. Hansson, K. A. Karlsson, and H. Leffler. 1987. Structures of blood group glycosphingolipids of human small intestine. A relation between the expression of fucolipids of epithelial cells and the ABO, Le and Se phenotype of the donor. J. Biol. Chem. 262:6758-6765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booth, B. A., M. Boesman-Finkelstein, and R. A. Finkelstein. 1983. Vibrio cholerae soluble hemagglutinin/protease is a metalloenzyme. Infect. Immun. 42:639-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth, B. A., M. Boesman-Finkelstein, and R. A. Finkelstein. 1984. Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease nicks cholera enterotoxin. Infect. Immun. 45:558-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnet, F. M. 1948. The mucinase of V. cholerae. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 26:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro-Rosas, J., and E. F. Escartin. 2002. Adhesion and colonization of Vibrio cholerae O1 on shrimp and crab carapaces. J. Food Prot. 65:492-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chowdhury, M. A., A. Huq, B. Xu, F. J. Madeira, and R. R. Colwell. 1997. Effect of alum on free-living and copepod-associated Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3323-3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colwell, R. R., A. Huq, M. S. Islam, K. M. Aziz, M. Yunus, N. H. Khan, A. Mahmud, R. B. Sack, G. B. Nair, J. Chakraborty, D. A. Sack, and E. Russek-Cohen. 2003. Reduction of cholera in Bangladeshi villages by simple filtration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1051-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colwell, R. R., J. Kaper, and S. W. Joseph. 1977. Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and other vibrios: occurrence and distribution in Chesapeake Bay. Science 198:394-396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colwell, R. R., and W. M. Spira. 1992. The ecology of Vibrio cholerae, p. 107-127. In Barua, D., and I. I. I. W. B. Greenough (ed.), Cholera. Plenum Medical Book Co, New York, NY.

- 12.Connell, T. D., D. J. Metzger, J. Lynch, and J. P. Folster. 1998. Endochitinase is transported to the extracellular milieu by the eps-encoded general secretory pathway of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 180:5591-5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lorenzo, V., and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Methods Enzymol. 235:386-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelstein, R. A., M. Boesman-Finkelstein, Y. Chang, and C. C. Hase. 1992. Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease, colonial variation, virulence, and detachment. Infect. Immun. 60:472-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finkelstein, R. A., M. Boesman-Finkelstein, and P. Holt. 1983. Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/lectin/protease hydrolyzes fibronectin and ovomucin: F.M. Burnet revisited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:1092-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finne, J., M. E. Breimer, G. C. Hansson, K. A. Karlsson, H. Leffler, J. F. Vliegenthart, and H. van Halbeek. 1989. Novel polyfucosylated N-linked glycopeptides with blood group A, H, X, and Y determinants from human small intestinal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 264:5720-5735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammer, B. K., and B. L. Bassler. 2003. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 50:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, R. R. Colwell, J. J. Mekalanos, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huq, A., E. B. Small, P. A. West, M. I. Huq, R. Rahman, and R. R. Colwell. 1983. Ecological relationships between Vibrio cholerae and planktonic crustacean copepods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45:275-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huq, A., P. A. West, E. B. Small, M. I. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 1984. Influence of water temperature, salinity, and pH on survival and growth of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae serovar O1 associated with live copepods in laboratory microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:420-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Islam, M. S., B. S. Drasar, and D. J. Bradley. 1989. Attachment of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae 01 to various freshwater plants and survival with a filamentous green alga, Rhizoclonium fontanum. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92:396-401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Islam, M. S., B. S. Drasar, and D. J. Bradley. 1990. Long-term persistence of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae 01 in the mucilaginous sheath of a blue-green alga, Anabaena variabilis. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:133-139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jobling, M. G., and R. K. Holmes. 1997. Characterization of hapR, a positive regulator of the Vibrio cholerae HA/protease gene hap, and its identification as a functional homologue of the Vibrio harveyi luxR gene. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1023-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joelsson, A., Z. Liu, and J. Zhu. 2006. Genetic and phenotypic diversity of quorum-sensing systems in clinical and environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 74:1141-1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kierek, K., and P. I. Watnick. 2003. Environmental determinants of Vibrio cholerae biofilm development. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5079-5088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirn, T. J., B. A. Jude, and R. K. Taylor. 2005. A colonization factor links Vibrio cholerae environmental survival and human infection. Nature 438:863-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirn, T. J., M. J. Lafferty, C. M. Sandoe, and R. K. Taylor. 2000. Delineation of pilin domains required for bacterial association into microcolonies and intestinal colonization by Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 35:896-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovacikova, G., W. Lin, and K. Skorupski. 2003. The virulence activator AphA links quorum sensing to pathogenesis and physiology in Vibrio cholerae by repressing the expression of a penicillin amidase gene on the small chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 185:4825-4836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovacikova, G., and K. Skorupski. 2002. Regulation of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae by quorum sensing: HapR functions at the aphA promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1135-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenz, D. H., K. C. Mok, B. N. Lilley, R. V. Kulkarni, N. S. Wingreen, and B. L. Bassler. 2004. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell 118:69-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, W., G. Kovacikova, and K. Skorupski. 2005. Requirements for Vibrio cholerae HapR binding and transcriptional repression at the hapR promoter are distinct from those at the aphA promoter. J. Bacteriol. 187:3013-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matz, C., D. McDougald, A. M. Moreno, P. Y. Yung, F. H. Yildiz, and S. Kjelleberg. 2005. Biofilm formation and phenotypic variation enhance predation-driven persistence of Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:16819-16824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meibom, K. L., X. B. Li, A. T. Nielsen, C. Y. Wu, S. Roseman, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2004. The Vibrio cholerae chitin utilization program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:2524-2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, NY.

- 35.Miller, M. B., K. Skorupski, D. H. Lenz, R. K. Taylor, and B. L. Bassler. 2002. Parallel quorum sensing systems converge to regulate virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Cell 110:303-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moorthy, S., and P. I. Watnick. 2005. Identification of novel stage-specific genetic requirements through whole genome transcription profiling of Vibrio cholerae biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1623-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richardson, K., and C. D. Parker. 1985. Identification and occurrence of Vibrio cholerae flagellar core proteins in isolated outer membrane. Infect. Immun. 47:674-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robert, A., A. Silva, J. A. Benitez, B. L. Rodriguez, R. Fando, J. Campos, D. K. Sengupta, M. Boesman-Finkelstein, and R. A. Finkelstein. 1996. Tagging a Vibrio cholerae El Tor candidate vaccine strain by disruption of its hemagglutinin/protease gene using a novel reporter enzyme: Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase A. Vaccine 14:1517-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sack, D. A., R. B. Sack, G. B. Nair, and A. K. Siddique. 2004. Cholera. Lancet. 363:223-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott, M. E., Z. Y. Dossani, and M. Sandkvist. 2001. Directed polar secretion of protease from single cells of Vibrio cholerae via the type II secretion pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:13978-13983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skorupski, K., and R. K. Taylor. 1996. Positive selection vectors for allelic exchange. Gene 169:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamplin, M. L., A. L. Gauzens, A. Huq, D. A. Sack, and R. R. Colwell. 1990. Attachment of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 to zooplankton and phytoplankton of Bangladesh waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1977-1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor, R. K., V. L. Miller, D. B. Furlong, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:2833-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thelin, K. H., and R. K. Taylor. 1996. Toxin-coregulated pilus, but not mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin, is required for colonization by Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor biotype and O139 strains. Infect. Immun. 64:2853-2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaitkevicius, K., B. Lindmark, G. Ou, T. Song, C. Toma, M. Iwanaga, J. Zhu, A. Andersson, M. L. Hammarstrom, S. Tuck, and S. N. Wai. 2006. A Vibrio cholerae protease needed for killing of Caenorhabditis elegans has a role in protection from natural predator grazing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:9280-9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yildiz, F. H., X. S. Liu, A. Heydorn, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2004. Molecular analysis of rugosity in a Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor phase variant. Mol. Microbiol. 53:497-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu, J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 2003. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev. Cell 5:647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu, J., M. B. Miller, R. E. Vance, M. Dziejman, B. L. Bassler, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2002. Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3129-3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]