Abstract

Retroviruses can establish persistent infection despite induction of a multipartite antiviral immune response. Whether collective failure of all parts of the immune response or selective deficiency in one crucial part underlies the inability of the host to clear retroviral infections is currently uncertain. We examine here the contribution of virus-specific CD4+ T cells in resistance against Friend virus (FV) infection in the murine host. We show that the magnitude and duration of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response is directly proportional to resistance against acute FV infection and subsequent disease. Notably, significant protection against FV-induced disease is afforded by FV-specific CD4+ T cells in the absence of a virus-specific CD8+ T-cell or B-cell response. Enhanced spread of FV infection in hosts with increased genetic susceptibility or coinfection with Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) causes a proportional increase in the number of FV-specific CD4+ T cells required to control FV-induced disease. Furthermore, ultimate failure of FV/LDV coinfected hosts to control FV-induced disease is accompanied by accelerated contraction of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response. Conversely, an increased frequency or continuous supply of FV-specific CD4+ T cells is both necessary and sufficient to effectively contain acute infection and prevent disease, even in the presence of coinfection. Thus, these results suggest that FV-specific CD4+ T cells provide significant direct protection against acute FV infection, the extent of which critically depends on the ratio of FV-infected cells to FV-specific CD4+ T cells.

Recovery from infection requires concerted actions by the immune system, coordinated by CD4+ T helper cells. The importance of the CD4+ T-cell response in controlling multiple pathogens is illustrated in primary (8) or acquired CD4+ T-cell immunodeficiency, such as during human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (18, 47). Although the contribution of CD4+ T cells to the control of viral infection is mediated largely through the provision of T-cell help to cytotoxic T cells and B cells, CD4+ T cells have also been shown to exert antiviral activity, independently of other arms of adaptive immunity. Indeed, a variable degree of CD4+ T cell-mediated protection has been demonstrated in mouse models of infection with several different viruses, including gammaherpesvirus 68 (58), influenza A virus (6), Sendai virus (7), West Nile virus (4), herpes simplex virus type 1 (31), and mouse hepatitis virus (56). A notable exception is infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), in which a highly elevated frequency of virus-specific CD4+ T cells had no appreciable protective effect against infection (43, 44) and even promoted viral replication in certain cases (51). Thus, these mouse studies, together with a substantial amount of knowledge gained from the study of viral infections in humans, emphasize that the pattern and protective value of antiviral T cells depends on the type and nature of the infecting virus (34).

The protective role of virus-specific CD4+ T cells against retroviral infection remains incompletely understood. A strong virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response positively correlates with control of viral replication in HIV-infected individuals with long-term nonprogressive disease or receiving early antiretroviral drug therapy (29, 48, 54). However, virus-specific CD4+ T cells are also directly affected by HIV replication (14, 17, 24, 29, 48), and it thus remains unclear whether a strong CD4+ T-cell response is the cause or a consequence of reduced viral loads (17, 24, 29, 48). Models for retroviral infection offer an opportunity to elucidate the cause-and-effect relationship between virus-specific CD4+ T-cell responses and retroviral infection. To this end, we have examined the fate and protective effect of virus-specific CD4+ T cells in an experimental mouse model for retroviral infection, using the Friend virus (FV).

FV is a retroviral complex of a replication-competent murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV) and a replication-defective spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV) (21, 39). Efficient infection of mice with F-MuLV or F-MuLV-pseudotyped SFFV requires the absence of a restricting allele at the polymorphic mouse Fv1 locus (39, 61). For example, in comparison with the B-tropic variant of F-MuLV (F-MuLV-B), replication of the N-tropic variant (F-MuLV-N) is attenuated ∼100-fold in B6 mice, due to expression of the Fv1b restriction factor in these mice (39, 61). FV infection of Fv1-susceptible mice can lead to severe splenomegaly, susceptibility to which is also genetically determined. The F-MuLV helper component does not cause disease by itself in adult immunocompetent mice. The viral gp55 encoded by the SFFV genome stimulates the erythropoietin receptor and is responsible for acute erythroblastosis, which can progress to erythroleukemia during chronic infection (32, 39, 41). This effect of SFFV gp55 is dependent on the presence of the dominant susceptibility allele at the mouse Fv2 locus (32, 39, 41). In addition to products of the Fv1 and Fv2 loci, several other mouse genes influence the development of FV-induced disease by affecting stages of viral replication, the development of erythroid cells, or the induction of the antiviral immune response (21, 39).

Previous studies using CD4-deficient or antibody-depleted mice highlighted an indispensable role for CD4+ T cells in the control of chronic FV infection but did not indicate an important role for the FV-specific primary CD4+ T-cell response in the early stages of acute infection or disease (19, 20, 52). The protective value of virus-specific CD4+ T cells induced by immunization or vaccination prior to FV infection was also studied in two independent systems. Miyazawa et al. used immunization with synthetic peptides, which contain CD4+ T-cell epitopes from the surface (SU; gp70) product of the F-MuLV envelope (env) gene (38). A peptide corresponding to gp70 amino acid residues 121 to 141 (env121-141) accelerated recovery of immunized mice from splenomegaly, but only partially protected the animals from acute disease, whereas an env462-479 peptide provided almost complete protection from acute disease (38). In contrast, by adoptively transferring immune cells from F-MuLV-N-vaccinated mice into naive recipients, Hasenkrug and coworkers showed that primed virus-specific CD4+ T cells were necessary, together with CD8+ T cells and B cells, but alone were not sufficient to protect against acute disease and were either unnecessary or insufficient to accelerate recovery from splenomegaly (13). Methodological differences notwithstanding, the variation in CD4+ T cell-mediated protection in the two systems could be reflecting differences in the number or functional state of primed virus-specific CD4+ T cells present before FV challenge. Since the magnitude of virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response induced by immunization or vaccination is not known, direct comparisons of its protective value are difficult to make. Furthermore, the recent discovery of lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) contamination in FV stocks, which dramatically alters the course of FV infection and impairs the immune response to it (36, 53), has not been consistently examined in previous studies, thus confounding interpretation of the results.

We have used a recently developed T-cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic mouse model (1) to examine the interrelation between acute FV infection and the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response. We report here that resistance to acute FV infection and associated disease is directly proportional to the precursor frequency of FV-specific CD4+ T cells. Notably, FV-specific CD4+ T cells mediate efficient protection against FV-induced disease independently of a virus-specific CD8+ T-cell or B-cell response or responsiveness of the host to gamma interferon (IFN-γ). We further show that enhancement of FV replication by LDV coinfection overcomes the protective effect of an elevated frequency of FV-specific CD4+ T cells. By following the dynamics of virus-specific CD4+ T cells during the course of infection, we show that failure of initial CD4+ T-cell-mediated control of FV replication in FV/LDV coinfection is associated with accelerated contraction of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response. More importantly, counteracting the contraction of FV-specific CD4+ T cells, by providing a higher precursor frequency or constant supply, effectively contains acute FV replication and splenomegaly induction, even during FV/LDV coinfection. Thus, our results suggest that resistance to acute FV infection critically relies on a favorable balance between the extent of initial FV replication and the magnitude and duration of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

F-MuLV env-specific TCR-transgenic mice (EF4.1 strain) were generated at the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) and have been previously described (1). B6, B6-CD45.1+ (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ), B6-MHC II−/− (B6.129-H2dlAb1-Ea/J) mice (12) and IFN-γ receptor 1 (IFN-γR1)-deficient mice (B6.129S7-Ifngr1tm1Agt/J or Ifngr1−/−) (25) have been previously described and were also maintained at the NIMR animal facilities. B6.A-Fv2s and B6.A-Fv2s Rag1−/− mice have also been generated at the NIMR and have been previously described (36). B6.A-Fv2s mice were additionally crossed with EF4.1 TCRβ-transgenic mice to produce B6.A-Fv2s EF4.1 mice. Fv1n-congenic B6 mice (B6.C3H-Fv1n) were generated by 10 consecutive back-crosses of C3H (Fv1n) mice onto the B6 background, selecting for the Fv1n allele in each generation. B6.C3H-Fv1n mice were subsequently crossed with EF4.1 TCRβ-transgenic mice and rendered homozygous for the Fv1n allele. All animal experiments were conducted according to UK Home Office regulations and local guidelines.

Viruses.

The FV used in the present study was a retroviral complex of a replication-competent B-tropic helper murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV) and a replication-defective polycythemia-inducing spleen focus-forming virus (SFFVp), referred to as FV. In addition, a stock of FV containing LDV was used (36, 53). Stocks were propagated in vivo and prepared as 10% (wt/vol) homogenate from the spleen of 12-day-infected BALB/c mice. Mice received an inoculum of ∼1,000 spleen focus-forming units of FV. The N-tropic helper F-MuLV (F-MuLV-N) stock used in the present study (10) was prepared as culture supernatants harvested from chronically infected Mus dunni cells. Mice received an inoculum of ∼104 infectious units of F-MuLV-N. All viral stocks were free of Sendai virus, murine hepatitis virus, parvoviruses 1 and 2, reovirus 3, Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus, murine rotavirus, ectromelia virus, murine cytomegalovirus, K virus, polyomavirus, Hantaan virus, murine norovirus, LMCV, and murine adenoviruses FL and K87. Viruses were injected via the tail vein in 0.1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline.

Assessment of infection.

FV-infected cells were detected by flow cytometry using surface staining for the glycosylated product of the viral gag gene (glyco-Gag), using the matrix (MA)-specific monoclonal antibody 34 (mouse immunoglobulin G2b [IgG2b]) (10), followed by an anti-mouse IgG2b-fluorescein isothiocyanate secondary reagent (BD, San Jose, CA). Cell-free virus was assayed by using a modification of previously described methods (3, 36). Briefly, single-cell suspensions were prepared from the spleens in 10% (wt/vol) Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium and spun at 1,200 rpm for 10 min. Cell-free supernatants were titrated onto M. dunni cells transduced with the XG7 replication-defective retroviral vector, expressing green fluorescent protein from a human cytomegalovirus promoter. Three days later culture supernatants were transferred onto untransduced M. dunni cells and incubated for another 3 days. The percentage of green fluorescent protein-positive M. dunni cells in the second culture was assessed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur (BD, San Jose, CA), and an endpoint dilution method of the rescued XG7 vector was used to calculate the titer of MuLV present in the original biological samples, which is expressed as infectious units per milliliter. Splenomegaly in infected mice was expressed as the spleen index, which is the ratio of the weight of the spleen (in milligrams) to the weight of the rest of the body (in grams).

T-cell purification, adoptive transfer, and detection.

CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes of donor TCRβ-transgenic mice, using immunomagnetic positive selection (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purity of the isolated CD4+ T-cell population was routinely higher than 92%. Indicated numbers of TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into recipient mice by intravenous injection via the tail vein, in 0.1 ml of air-buffered Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium. Engraftment of transferred cells was assessed 1 day after transfer. Transferred T cells were detected in the spleen of recipient mice at various time points following infection by six-color flow cytometry, using the CyAn ADP Analyzer (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark). Flow cytometry data were analyzed with Summit v4.3 software (Dako). Directly conjugated antibodies were obtained from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA) or CALTAG/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Statistical analysis.

Linear percentages of FV-infected cells and Spleen indices were compared by using nonparametric two-tailed Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests. All other comparisons were made by using two-tailed Student t tests.

RESULTS

CD4+ T cells contribute to control of acute FV infection.

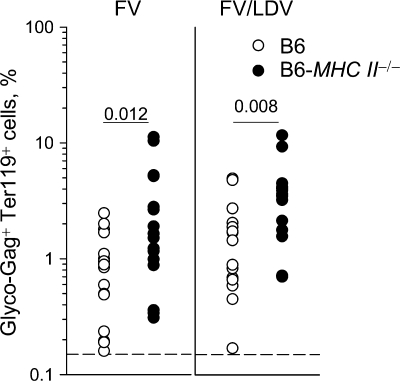

To examine the contribution of CD4+ T cells to resistance of B6 mice to the early stages of FV infection we have used mice deficient in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II expression, in which development of CD4+ T cells is blocked in the thymus (12). Compared to control B6 mice, the frequencies of FV-infected cells, assessed by staining for retroviral glyco-Gag on the surfaces of erythroblasts (Ter119+), which are the predominant cell type infected by FV, were significantly elevated in MHC class II-deficient mice 7 days after either FV infection or FV/LDV coinfection (Fig. 1). Although this finding demonstrated that lack of CD4+ T cells increased susceptibility to FV infection, it did not reveal whether CD4+ T cells were acting at the time of infection, since MHC class II deficiency was congenital.

FIG. 1.

Contribution of endogenous CD4+ T cells to protection against acute FV infection. MHC class II-deficient (B6-MHC II−/−) and control B6 mice were infected with FV or coinfected with FV and LDV, and the percentage of FV-infected (glyco-Gag+) Ter119+ cells in the spleen, 7 days postinfection, is shown. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. The dashed line indicates the limit of flow cytometric detection.

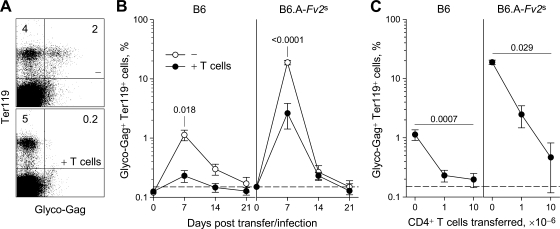

To test whether FV-specific CD4+ T cells could contribute to control of acute FV infection we used a recently described TCRβ chain-transgenic mouse strain, referred to as EF4.1 (1), in which the precursor frequency of the F-MuLV env122-141-specific CD4+ T cells was elevated to ca. 4% of all CD4+ T cells. B6 mice received 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells (containing 40,000 env-specific CD4+ T cells), and cell engraftment was determined the following day to be approximately 8,000 env-specific CD4+ T cells per spleen of recipient mice. Recipient mice were infected with FV 1 day after cell transfer. Transfer of env-specific CD4+ T cells dramatically reduced the number of infected erythroblasts at the peak of infection compared to control B6 mice (Fig. 2A and B, left), indicating a strong protective effect of the env-specific TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 2.

Protection against FV infection by additional env-specific CD4+ T cells. (A) B6 control mice (−) and B6 mice, which received 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells 1 day before infection (+ T cells), were infected with FV and the percentage of FV-infected (glyco-Gag+) Ter119+ cells in the spleen, 7 days postinfection, is shown. Numbers within the quadrants denote the percentages of positive cells. (B) Percentage of glyco-Gag+ Ter119+ cells in the spleen of B6 (left) or B6.A-Fv2s mice (right), after FV infection, with (+ T cells) or without (−) adoptive transfer of 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells 1 day before infection. Values are the means (± the SEM) of 4 to 12 mice per group per time point. The dashed line indicates the limit of flow cytometric detection. (C) Percentage of glyco-Gag+ Ter119+ cells in the spleen of B6 (left) or B6.A-Fv2s mice (right), 7 days after FV infection, with adoptive transfer of titrated numbers TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells 1 day before infection. Values are the mean (± the SEM) of three to nine mice per group per CD4+ T-cell inoculum. The dashed line indicates the limit of flow cytometric detection.

B6 mice experience limited infection with FV due to a combination of a strong immune response and the lack of the Fv2s dominant susceptibility allele (21, 36). We thus examined whether adoptively transferred env-specific CD4+ T cells would also protect Fv2s-congenic B6 mice (B6.A-Fv2s), in which FV infection peaks at 10-fold higher levels (36). Indeed, transfer of 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells provided significant, albeit incomplete protection against FV infection of B6.A-Fv2s mice (Fig. 2B, right). Increasing the number of adoptively transferred TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells improved protection in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). Together, these results suggested that env-specific CD4+ T cells afford significant protection against acute FV infection, the extent of which depended on the ratio of FV-infected cells to FV-specific CD4+ T cells.

CD4+ T cells control acute FV infection independently of CD8+ T cells and B cells.

Immune control of FV infection is thought to rely on the concerted effort of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and antibody production by B cells (19, 20, 52). However, studies with immunization with an MHC class II-restricted peptide epitope have indicated a direct protective effect mediated by the primed CD4+ T cells (38). Moreover, protection induced by peptide immunization was also observed in cytotoxic T cell-deficient mice and before the appearance of FV neutralizing antibodies (33). Similarly, our results suggested that CD4+ T-cell-dependent protection against acute FV infection was not mediated by FV neutralizing antibodies, since these are not detectable until the second week of infection (36), and adoptive transfer of TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells did not accelerate their induction (data not shown).

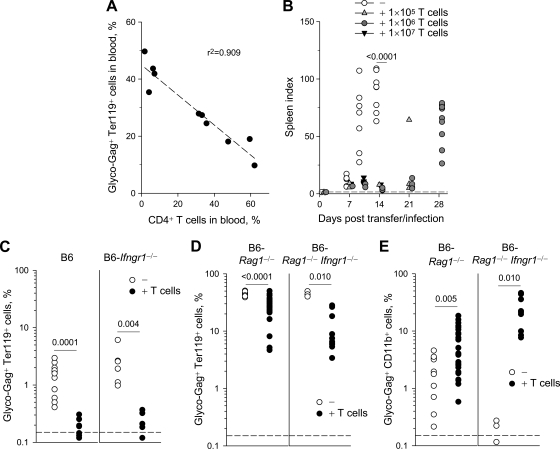

To directly test whether or not protection against acute FV infection by env-specific CD4+ T cells required the presence of an FV-specific CD8+ T-cell or antibody response, we have performed adoptive transfer of FV-specific CD4+ T cells into lymphocyte-deficient B6.A-Fv2s Rag1−/− recipients. FV infection of B6.A-Fv2s Rag1−/− mice causes fatal disease within 11 to 14 days (36). Between 105 and 107 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into B6.A-Fv2s Rag1−/− recipients, which were infected with FV 1 day later. In a dose-dependent manner, adoptively transferred env-specific CD4+ T cells significantly reduced the levels of FV-infected erythroblasts in the blood of recipient mice 7 days postinfection (Fig. 3A). Importantly, env-specific CD4+ T cells also protected the recipient mice from splenomegaly. Transfer of high numbers (107) of TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells, albeit protective against infection, was also associated with the development of more severe anemia at later time points (data not shown). Notably, transfer of as few as 105 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells (corresponding to splenic engraftment of ∼800 env-specific CD4+ T cells) was sufficient to significantly delay FV-induced splenomegaly (Fig. 3B). In stark contrast to control B6.A-Fv2s Rag1−/− mice, all of which developed severe splenomegaly by day 10 and had to be euthanized by day 14, none of the B6.A-Fv2s Rag1−/− recipients of 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells displayed significant splenic enlargement during the first 21 days of infection (Fig. 3B). However, env-specific CD4+ T cells did not protect B6.A-Fv2s Rag1−/− recipients indefinitely, and splenomegaly did eventually develop by 28 postinfection (Fig. 3B). Thus, our results indicated that acute FV infection and splenomegaly could be directly controlled by env-specific CD4+ T cells independently of an FV-specific cytotoxic and antibody response.

FIG. 3.

CD8+ T-cell-, B-cell-, and IFN-γR-independent protection by env-specific CD4+ T cells. (A) Negative correlation between the percentage of FV-infected (glyco-Gag+) Ter119+ cells and the percentage of donor CD4+ T cells in the blood, 7 days after FV infection of lymphopenic B6.A-Fv2s Rag1−/− mice, which received titrated numbers of TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells. (B) Spleen index after FV infection of B6.A-Fv2s Rag1−/− mice, with (+ T cells) or without (−) adoptive transfer of indicated numbers of TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. The dashed line indicates the spleen index of uninfected mice. (C) Percentage of glyco-Gag+ Ter119+ cells in the spleen of B6 (left) or B6-Ifngr1−/− mice (right), 7 days after FV infection, with (+ T cells) or without (−) adoptive transfer of 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells 1 day before infection. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. The dashed line indicates the limit of flow cytometric detection. (D) Percentage of glyco-Gag+ Ter119+ cells in the spleen of B6-Rag1−/− (left) or B6-Rag1−/− Ifngr1−/− mice (right), 35 days after FV infection, with (+ T cells) or without (−) adoptive transfer of 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells 1 day before infection. (E) Percentage of glyco-Gag+ CD11b+ myeloid cells in the spleen of the same mice as in panel D. Each symbol in panels D and E represents an individual mouse. The dashed lines indicate the limit of flow cytometric detection.

Previous in vitro studies indicated that FV-infected cells are exquisitely sensitive to CD4+ T-cell-produced IFN-γ, which can inhibit viral replication in these cells and additionally affect their survival (28), suggesting that the protective effect of CD4+ T cells against FV infection may be mediated by IFN-γ in vivo as well. We therefore compared the extent of protection conferred by env-specific CD4+ T cells to either wild-type recipients or recipients unable to respond to IFN-γ due to lack of IFN-γR (25). Interestingly, adoptive transfer of env-specific CD4+ T cells significantly reduced the percentage of FV-infected erythroblasts on day 7 postinfection even in IFN-γR-deficient mice (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the degree of protection conferred by env-specific CD4+ T cells was comparable between wild-type and IFN-γR-deficient recipients (Fig. 3C), indicating that IFN-γR-signaling had no major involvement in this process. To examine whether env-specific CD4+ T cell-mediated protection was independent of IFN-γR-signaling in target cells even in the absence of an FV-specific CD8+ T-cell and antibody responses, we have used B6-Rag1−/− and B6-Rag1−/− Ifngr1−/− recipients. As previously reported (1), infection of B6-Rag1−/− mice with FV led to chronic infection with ∼50% of splenic erythroblasts expressing viral glyco-Gag on their surface (Fig. 3D). Adoptive transfer of env-specific CD4+ T cells into FV-infected B6-Rag1−/− recipients did not completely eliminate erythroblasts infection, but significantly reduced the frequency for the whole duration of the observation period (up to day 35 postinfection) (Fig. 3D) (1). Importantly, the reduction in the percentage of FV-infected erythroblasts caused by adoptive transfer of env-specific CD4+ T cells was also evident in B6-Rag1−/− Ifngr1−/− recipients (Fig. 3D), suggesting that IFN-γR-signaling was not required. Notably, adoptive transfer of env-specific CD4+ T cells was also associated with an unexplained increase in the percentage of FV-infected CD11b+ myeloid cells, which was otherwise relatively low, in B6-Rag1−/− recipients and, to a higher degree, B6-Rag1−/− Ifngr1−/− recipients (Fig. 3E). Together, these findings suggest that although IFN-γR-signaling may partly contribute to resistance of CD11b+ myeloid cells to CD4+ T-cell-enhanced FV-infection, it was not required for the control of FV-infected erythroblasts by env-specific CD4+ T cells in either lymphocyte-deficient or lymphocyte-replete mice.

Enhancement of FV replication by LDV coinfection limits CD4+ T cell-mediated protection.

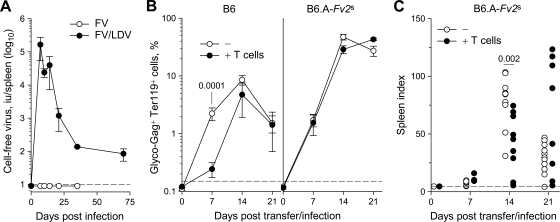

Coinfection by LDV has been shown to exacerbate acute FV infection and subsequent disease in immunocompetent mice and to delay induction of FV-specific CD8+ T-cell and antibody responses (36, 53). However, our results suggested that an elevated frequency of FV-specific CD4+ T cells alone was sufficient to protect against acute FV infection. To examine whether this was true also for FV/LDV coinfection and to directly compare our findings with previously published studies, which used LDV-containing FV stocks, we repeated the adoptive transfer experiments in FV/LDV-coinfected hosts. We have previously shown that frequencies of FV-infected cells in B6 and B6.A-Fv2s mice were similar between FV infection and FV/LDV coinfection during the first 7 days (36). In contrast to FV infection, which was then rapidly controlled, the frequencies of FV-infected cells continued to rise during FV/LDV coinfection and were not controlled until 4 to 5 weeks postinfection (36). However, the presence of LDV during FV infection led to much higher levels of cell-free FV in the spleens of infected mice, already evident from the first week of coinfection compared to infection with FV alone, which did not generate measurable cell-free FV in the spleens of B6 mice (Fig. 4A). However, lack of measurable cell-free FV in the spleens of infected B6 mice was not due to a complete lack of viremia during FV infection. Indeed, using focal infectivity assays, viremia was detectable in a previous study, albeit at low levels, in plasma samples from B6 mice infected with a higher dose of FV (55). Nevertheless, plasma FV viremia during FV/LDV coinfection was ∼10-fold higher than during FV infection (data not shown). Thus, LDV coinfection exacerbated and prolonged FV infection.

FIG. 4.

Enhancement of FV replication by LDV coinfection overcomes protection by env-specific CD4+ T cells. (A) Cell-free virus in spleen homogenates from B6 mice after infection with FV or coinfection with FV and LDV. Values are the mean (± the SEM) of three to five mice per group per time point. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection. (B) Percentage of glyco-Gag+ Ter119+ cells in the spleen of B6 (left) or B6.A-Fv2s mice (right), after FV/LDV coinfection, with (+ T cells) or without (−) adoptive transfer of 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells 1 day before infection. Values are the means (± the SEM) of six to nine mice per group per time point. The dashed line indicates the limit of flow cytometric detection. (C) Spleen index following FV/LDV coinfection of B6.A-Fv2s mice, with (+ T cells) or without (−) adoptive transfer of TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. The dashed line indicates the spleen index of uninfected mice.

Adoptive transfer of 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells into FV/LDV-coinfected B6 mice provided significant protection against FV infection on day 7 postinfection (Fig. 4B, left). However, the protective effect of transferred env-specific CD4+ T cells was subsequently lost and adoptive recipient and control mice displayed similar frequencies of FV-infected cells by day 14 (Fig. 4B, left). To examine whether env-specific CD4+ T cells could protect against FV-induced splenomegaly in the presence of LDV coinfection, we used B6.A-Fv2s mice, which develop severe splenic enlargement when coinfected with FV and LDV (36). Adoptive transfer of 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells into FV/LDV-coinfected B6.A-Fv2s mice had little effect on the percentage of FV-infected erythroblasts in the spleen (Fig. 4B, right). However, the transferred CD4+ T cells caused significant reduction in splenomegaly at the peak of disease on day 14 (Fig. 4C). Nevertheless, protection against splenomegaly by env-specific CD4+ T cells was subsequently lost and many of the CD4+ T-cell B6.A-Fv2s recipients displayed severe splenomegaly on day 21, a time point at which control B6.A-Fv2s mice had recovered from the disease (Fig. 4C). Thus, env-specific CD4+ T cells mediated significant, but transient protection against FV infection and disease in the presence of LDV coinfection.

Enhancement of FV replication by LDV coinfection curtails the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response.

Our results indicated that env-specific CD4+ T cells could directly control acute FV infection and that LDV coinfection restricted their protective effect. We therefore examined whether LDV coinfection affected the magnitude or kinetics of the CD4+ T-cell response to FV infection.

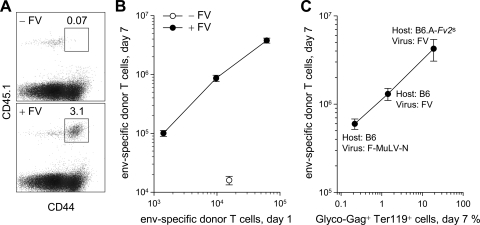

To follow the in vivo dynamics of env-specific CD4+ T cells during infection, 106 CD45.1+ TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into B6 (CD45.2+) recipient mice. TCR-transgenic CD4+ T cells transferred into uninfected B6 recipients maintained a naive phenotype (CD44lo) and did not expand in number (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, FV infection led to the emergence of an activated (CD44hi) population of donor CD4+ T cells, which comprised 2 to 5% of all CD4+ T cells by day 7 postinfection (Fig. 5A) and which we considered to represent env-specific CD4+ T cells among the donor T-cell population. Titration of the number of transferred cells revealed that expansion of env-specific CD4+ T cells was always ∼100-fold, such that the recovery of env-specific CD4+ T cells on day 7 was directly proportional to the number of the same cells on day 1 (Fig. 5B). This finding suggested that peak expansion of env-specific CD4+ T cells was limited by their precursor frequency. To examine whether the CD4+ T-cell response to FV infection was also affected by the level of infection, we compared three types of infection with various replication levels: (i) infection of B6 mice with F-MuLV-N, which replicates poorly because of the action of Fv1b in these mice (61), and also because it lacks the pathogenic SFFV component of the viral complex; (ii) infection of B6 mice with FV; and (iii) infection of B6.A-Fv2s mice with FV. Expansion of env-specific CD4+ T cells was proportional to the level of FV-infected cells reached in each infection, with ∼3-fold increases in CD4+ T-cell expansion for every 10-fold increase in infection level (Fig. 5C). Thus, both the precursor frequency of env-specific CD4+ T cells and the level of infection influenced, to a different degree, the magnitude of the CD4+ T-cell response to FV infection.

FIG. 5.

Priming of adoptively transferred env-specific CD4+ T cells during FV infection. (A) 106 CD45.1+ TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells were transferred into B6 (CD45.2+) recipients, which remained uninfected (− FV) or were infected with FV 1 day later (+ FV). The percentage of activated donor (CD44+ CD45.1+) CD4+ T cells in gated total splenic CD4+ T cells is shown. (B) Correlation between numbers of grafted env-specific CD4+ T cells in the spleen 1 day after transfer and numbers of the same cells 7 days postinfection with FV (+ FV). Numbers of env-specific CD4+ T cells recovered from uninfected mice (− FV) are also shown for comparison. Values are the mean (±SEM) of 3 to 7 mice per group per CD4+ T-cell inoculum. (C) Correlation between the peak percentage of FV-infected (glyco-Gag+) Ter119+ cells in the spleen, 7 days postinfection of the indicated host with the indicated virus and the numbers of env-specific CD4+ T cells recovered at the same time point. Values are the mean (±SEM) of 4 to 11 mice per virus-host combination.

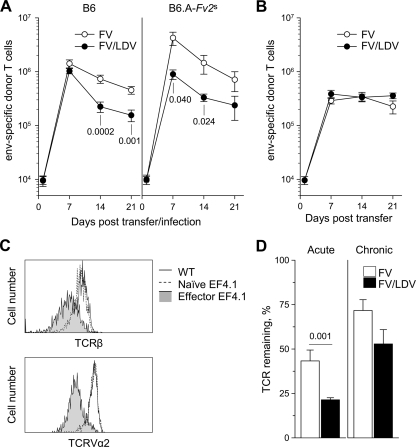

After their peak expansion on day 7, numbers of env-specific CD4+ T cells transferred into FV-infected B6 mice declined steadily over the next two weeks to ca. 30% of peak numbers by day 21 postinfection (Fig. 6A, left). Notably, env-specific CD4+ T cells transferred into FV/LDV-coinfected B6 mice expanded to a comparable peak on day 7 but declined more rapidly thereafter than those in FV-infected B6 mice (Fig. 6A, left). Furthermore, increased FV replication in B6.A-Fv2s mice coinfected with FV and LDV was not accompanied with an enhanced CD4+ T-cell response, and env-specific CD4+ T-cell expansion was overall significantly reduced in these mice in comparison with B6.A-Fv2s mice infected with FV alone (Fig. 6A, right). These results suggested that the presence of LDV during FV infection did not alter the timing of induction but adversely affected the duration of the CD4+ T-cell response to FV.

FIG. 6.

Curtailed env-specific CD4+ T-cell response during FV/LDV coinfection. (A) 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into recipient mice 1 day before infection. Numbers of env-specific CD4+ T cells recovered from the spleen of B6 (left) or B6.A-Fv2s recipients (right), 7 days after FV infection or FV/LDV coinfection is shown. Values are the mean (± the SEM) of 4 to 10 mice per group per time point. (B) 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into recipient mice 35 days postinfection. Numbers of env-specific CD4+ T cells recovered from the spleen of chronically infected B6 recipients 7 days after adoptive transfer is shown. Values are the means (± the SEM) of five to eight mice per group per time point. (C) Flow cytometric comparison of TCRβ (top) and TCRVα2 levels (bottom) between env-specific CD4+ T cells recovered from recipient mice on day 7 after FV infection (effector EF4.1) and naive TCR-transgenic CD4+ T cells before transfer (naive EF4.1). For comparison, wild-type CD4+ T cells of the host are also included (WT). Histograms show electronically gated CD4+ T cells (top) or CD4+ TCRVα2+ T cells (bottom) and are representative of at least seven mice per group. (D) Remaining levels of TCR in env-specific CD4+ T cells recovered from recipient mice on day 7 after acute (left) or chronic (right) FV infection or FV/LDV coinfection. Values are expressed as the percentage of the full amount of TCR found in wild-type host CD4+ T cells that remains in env-specific CD4+ T cells, and are the means (± the SEM) of five to nine mice per group.

The faster decline of the CD4+ T-cell response to FV caused by LDV coinfection could be due to the dramatic enhancement of FV replication by LDV. Alternatively, it could reflect a direct effect of LDV on env-specific CD4+ T cells, independently of FV replication. To confirm that the levels of FV replication were the major determinant of the env-specific CD4+ T-cell response, we adoptively transferred 106 TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells into FV-infected or FV/LDV-coinfected B6 mice 35 days postinfection. By this time FV infection was controlled to comparably low and stable levels in both groups of mice, whereas LDV infection persisted in the FV/LDV-coinfected group. Expansion of env-specific CD4+ T cells in chronically infected hosts was less pronounced than expansion in acutely infected hosts (Fig. 6B). In contrast to what was seen in acutely infected hosts, however, the numbers of expanded env-specific CD4+ T cells were stably maintained throughout the observation period, with little evidence of contraction (Fig. 6B). More importantly, the kinetics of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response in chronically infected hosts was not affected by the LDV status of the recipient (Fig. 6B), indicating that env-specific CD4+ T-cell numbers were determined by levels of FV replication rather than the presence of LDV.

TCR interaction with cognate peptide-MHC complexes causes reversible TCR downmodulation from the cell surface through internalization (62). Therefore, the level of TCR remaining on the surface of env-specific CD4+ T cells would be inversely proportional to their recent history of env122-141 recognition. Compared to either naive TCR-transgenic CD4+ T cells or host wild-type CD4+ T cells, the level of TCRβ chain in env-specific donor-type CD4+ T cells was substantially reduced 7 days after adoptive transfer into B6 mice acutely infected with FV (Fig. 6C), indicating recent antigenic stimulation. This TCR downmodulation was similarly evident with staining for TCR Vα2 (Fig. 6C), an endogenous Vα chain enriched in env-specific CD4+ T-cell clones (1). Thus, both TCRα and TCRβ chains were downmodulated in env-specific CD4+ T cells at the peak of their response to FV infection. Importantly, TCR downmodulation was significantly more pronounced in env-specific CD4+ T cells recovered on day 7 from FV/LDV acutely coinfected recipients than from FV acutely infected ones (Fig. 6D), suggesting that the former cells were receiving stronger antigenic stimulation. In contrast, TCR downmodulation was much less pronounced in env-specific CD4+ T cells recovered 7 days after transfer into chronically infected mice and was not significantly influenced by the presence or absence of chronic LDV coinfection (Fig. 6D). These results revealed a correlation between the kinetics of env-specific CD4+ T-cell responses and the degree of TCR downmodulation, further supporting the idea that excessive antigenic stimulation contributed to the decline of env-specific CD4+ T cells during acute FV/LDV coinfection.

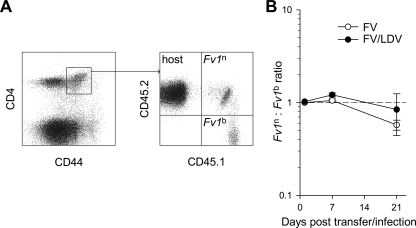

The effect of FV replication on the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response could be mediated by the relative availability of FV-derived antigens. Alternatively, enhanced FV replication could adversely affect the CD4+ T-cell response by direct FV infection of the effector CD4+ T cells. To exclude the latter possibility, we used CD4+ T cells, which can resist infection with FV. TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells from CD45.1+ B6 mice (Fv1b) were mixed in equal ratio with TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells from CD45.1/2+ Fv1n-congenic B6 mice (Fv1n) and injected into CD45.2+ B6 recipients infected with FV containing a B-tropic helper virus (Fig. 7A). Expression of Fv1n in CD45.1/2+, but not in CD45.1+ env-specific CD4+ T cells would restrict FV, and any deviation from the injected ratio of the two donor CD4+ T-cell populations would reveal a direct viral effect. However, Fv1-mediated restriction did not confer any advantage to Fv1n env-specific CD4+ T cells over their Fv1b counterparts (Fig. 7B), during either FV infection or FV/LDV coinfection, suggesting that direct FV infection, at least to the extent that is restricted by Fv1, did not contribute to the contraction of env-specific CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 7.

Independence of env-specific CD4+ T-cell kinetics from the potential influence of direct FV infection. Fv1b CD45.1+ TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells were mixed in equal ratio with Fv1n CD45.1/2+ TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells and injected into CD45.2+ B6 recipients, which were infected the following day. (A) Flow cytometric detection of host (CD45.2+) and Fv1n (CD45.1/2+) and Fv1b (CD45.1+) donor CD4+ T cells in gated CD44+ CD4+ splenic T cells. (B) Ratio of Fv1n to Fv1b donor CD4+ T cells over the course of FV infection or FV/LDV coinfection. Values are the means (± the SEM) of three to four mice per group per time point. The dashed line indicates the injected ratio.

Elevated precursor frequency of env-specific CD4+ T cells provides complete control of FV infection.

Our results indicated that env-specific CD4+ T cells provided significant control over FV infection, which was transient when FV replication was enhanced by LDV coinfection. Moreover, loss of CD4+ T-cell-mediated protection in the latter situation was also associated with reduced env-specific CD4+ T-cell responses. However, the reduced env-specific CD4+ T-cell response seen at high levels of FV replication could be explained by two different underlying mechanisms. Env-specific CD4+ T cells could be directly responsible for controlling FV replication and their loss would be a requirement for FV replication to reach high levels. Alternatively, env-specific CD4+ T cells could be simply reflecting, but not directly affecting FV replication, and their loss would be a consequence rather than the cause of high FV replication levels.

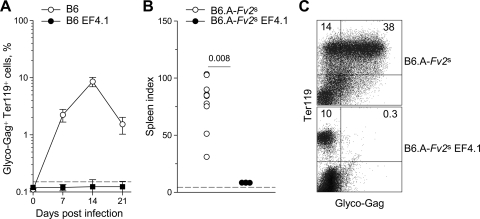

We reasoned that if contraction of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response allowed high levels of FV replication in the second week of FV/LDV coinfection, maintaining a strong and lasting antiviral CD4+ T-cell response should extend its protective effect beyond the first week and throughout infection. Indeed, TCRβ-transgenic mice, in which env-specific CD4+ T-cell were in very high frequency (>106 env-specific CD4+ T cells per spleen) and continually produced from the thymus, potently controlled FV replication when coinfected with FV and LDV, throughout the observation period (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, in contrast to littermate B6.A-Fv2s control mice Fv2s-congenic TCRβ-transgenic mice (B6.A-Fv2s EF4.1) were protected against splenomegaly induction after FV/LDV coinfection (Fig. 8B) and almost completely lacked FV-infected erythroblasts detectable by flow cytometry (Fig. 8C). Thus, a high precursor frequency of env-specific CD4+ T cells was sufficient to control FV replication and associated splenomegaly throughout FV/LDV coinfection, suggesting that uncontrolled FV replication during the second week of this coinfection was mechanistically caused by an insufficiently maintained FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response.

FIG. 8.

Complete protection against FV infection by an elevated env-specific CD4+ T-cell precursor frequency. (A) TCRβ-transgenic mice (B6 EF4.1) and littermate B6 control mice were coinfected with FV and LDV, and the percentage of FV-infected (glyco-Gag+) Ter119+ cells in the spleen over the course of the infection is shown. The dashed line indicates the limit of flow cytometric detection. Values are the means (± the SEM) of six to eight mice per group per time point. (B) Fv2s-congenic TCRβ-transgenic mice (B6.A-Fv2s EF4.1) and littermate B6.A-Fv2s control mice were coinfected with FV and LDV, and the peak spleen index was assessed 14 days postinfection. The dashed line indicates the spleen index of uninfected mice. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (C) The percentage of glyco-Gag+ Ter119+ cells in the spleen of the same mice 14 days postinfection is shown. Numbers within the quadrants denote the percentages of positive cells.

DISCUSSION

There is growing consensus that the ultimate outcome of retroviral infection is determined by events taking place very early following infection. Here we have shown that the kinetics of the virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response, relative to the speed with which FV spreads during acute infection, is a primary factor in resistance or susceptibility of mice to FV-associated disease.

Our results revealed that the primary CD4+ T-cell response induced by FV infection provides significant, albeit partial, protection during the first 7 days of acute infection, since mice deficient in MHC class II molecules displayed increased susceptibility to both FV infection and FV/LDV coinfection. A protective role for this early FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response was not evident in previous studies investigating mice depleted of CD4+ T cells (52) or mice genetically deficient in CD4 (19). However, antibody-mediated CD4+ T-cell depletions are often incomplete and, in contrast to MHC class II-deficient mice, mice deficient in CD4 still exhibit residual MHC class II-restricted function and resist infection to some extent (23, 35, 37, 50). Furthermore, the earlier studies assessed infection by measuring splenomegaly, which may not be as sensitive as frequencies of infected cells. These factors may have obscured the relatively small increase in susceptibility caused by the complete lack of MHC class II-restricted T-cell activity.

This primary FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response is a significant contributor to the rapid and potent immune-mediated control of FV infection in B6 mice (36). Despite evidence for immune-mediated control of FV during the first week of FV/LDV coinfection, the dramatic enhancement of FV replication caused by LDV overcomes immune defenses and FV-induced disease in immunocompetent B6 mice progresses as fast as, if not faster than, in immunodeficient ones, during the following weeks (36). The presence of LDV has been previously shown to delay induction of the FV-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell response until after the first week of FV/LDV coinfection (53). Furthermore, neutralizing FV-specific antibodies are not present during the first week of FV infection and are further delayed by LDV (36). In contrast to the FV-specific CD8+ T-cell and antibody response, our results indicated that the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response peaks 1 week after FV infection or FV/LDV coinfection and is thus not delayed by the presence of LDV. The FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response does, however, contract during the following weeks, and this contraction is further exacerbated by LDV. These findings therefore reveal an important asynchrony between the CD4+ T-cell response and the other two arms of adaptive immunity. The finding that only the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response is active during early FV/LDV coinfection supports the notion that early control of FV spread in FV/LDV coinfection is mediated by virus-specific CD4+ T cells. Interestingly, specific CD4+ T cells have been shown to develop earlier than specific CD8+ T cells also in response to retrovirus-induced tumors (57).

As with other retroviruses, FV establishes persistence and causes disease in virus-naive mice, in spite of the induction of a virus-specific primary immune response, and this ability of FV is amplified by additional genetic susceptibility or by coinfection. In contrast, mice vaccinated or immunized against FV can potently control the infection and subsequent disease (13, 38), and both T-cell-dependent and antibody-dependent mechanisms have been implicated in protective immunity to FV (13). Despite their importance in providing help for the cytotoxic T-cell and B-cell response, virus-specific CD4+ T cells have not been traditionally considered as the leading protective subset in viral infection. In LCMV infection, a vastly elevated frequency of virus-specific T helper cells does not positively contribute to viral clearance (43, 44). In HIV infection, the duality of CD4+ T cells as both immune effectors and infectible targets may mask any protective effect from enhancing the T helper response (59, 60). However, to a variable degree, CD4+ T cells have been shown to provide protection in several models of viral infection, independently of cytotoxic T cells and B cells (4, 6, 7, 31, 56, 58). Our results demonstrate that the presence of virus-specific CD4+ T cells is both necessary and, more importantly, sufficient to contain FV infection, highlighting their protective effect against retroviruses, in particular.

Previous studies on vaccination- or immunization-induced CD4+ T cells have given variable results regarding the role of these cells in protection against FV infection. For example, CD4+ T cells from F-MuLV-N vaccinated mice failed to protect naive recipients (13), whereas env121-141-immunized mice were only partially protected against acute infection (38). In contrast, mice immunized with the env462-479 peptide were almost completely protected against acute FV infection in an earlier study (38). Differences in the extent of virus-specific CD4+ T-cell-mediated protection is likely due to differences in the functional state or simply the number of FV-specific memory CD4+ T cells present before FV challenge. Indeed, our preliminary data suggest that peptide immunization induces a higher number of FV-specific memory CD4+ T cells than F-MuLV-N vaccination. Furthermore, studies with env peptide immunization have demonstrated that repeated immunizations are more protective than a single one (38), suggesting a correlation between the magnitude of the primed CD4+ T-cell response and protection against acute FV infection. However, the result was not definitive because repeated immunization would also enhance differentiation to provide better effector function. The use of TCR-transgenic env-specific CD4+ T cells, which are found predominantly in the naive subset of CD4+ T cells (1), allowed us to eliminate the functional state of FV-specific CD4+ T cells as a variable and focus on the contribution of precursor frequency. Although, per-cell, antigen-experienced memory CD4+ T cells would display enchanted protective capacity, in comparison with naive CD4+ T cells, we found that the contribution of precursor frequency was critical and an increased frequency of otherwise naive virus-specific CD4+ T cells could provide significant protection against FV infection.

Using TCRβ-transgenic CD4+ T cells with an increased frequency of FV-specific clones also allowed us to follow the precise dynamics of expansion and contraction of a cohort of FV-specific CD4+ T cells. Our analysis revealed that the magnitude of FV-specific CD4+ T-cell peak expansion varies according to their precursor frequency and the level of virus load. Interestingly, peak expansion of FV-specific CD4+ T cells is always reached 1 week postinfection, irrespective of the severity or chronicity of infection. Indeed, studies from LCMV infection in mice have shown that contraction of the virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response in chronic viral infection may display similar, if not accelerated kinetics compared to acute resolving infection (5). Contraction of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response in the second and third weeks of infection coincides with the peak of FV replication and is not due to lack of stimulation from diminishing antigen presentation or competition with an endogenous response because TCRβ-transgenic T cells adoptively transferred into B6 recipients infected 35 days previously also expand efficiently. Thus, the majority of T helper cells activated and expanded during the first week of FV infection subsequently disappear despite (or perhaps because of) continuous presentation of viral antigens. Importantly, having excluded the effects of direct viral infection, the finding that contraction of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response is accelerated during enhanced FV replication (induced by LDV coinfection) implicates excessive antigenic stimulation as a cause of the contraction. This interpretation is further supported by the observed correlation between the degree of TCR downmodulation in FV-specific CD4+ T cells, an indicator of recent antigenic encounter, and the rate of their decline. However, the precise reasons behind the fast decline of the virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response during FV infection, or any other chronic viral infection, are not entirely clear and require further investigation. The accelerated contraction of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell response in the presence of LDV coinfection observed in the present study was not immediately apparent in a previous study, which used MHC II Ab/env121-141 tetramers for the detection of FV-specific CD4+ T cells (53). The difference in outcome is most likely due to fact that this particular MHC II Ab/env121-141 tetramer does not bind all env121-141-reactive CD4+ T-cell clones (1, 57) and may thus only reveal a partial picture of the FV-specific CD4+ T-cell kinetics.

Irrespective of the mechanisms behind contraction of the FV-specific CD4+ T cells, our results firmly associate the presence of a strong antiviral CD4+ T-cell response with protection against acute infection. These findings indicate that an elevated virus-specific CD4+ T-cell frequency is sufficient to provide protection against FV infection as long as the CD4+ T-cell response is preserved. The FV specific cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell and B-cell responses undoubtedly contribute to more robust resistance to FV infection and are absolutely required for full control of FV replication (13, 36, 53, 53). This is also evident in the present study, where adoptive transfer of FV-specific CD4+ T cells completely prevents FV infection from reaching flow cytometry detectable levels in lymphocyte-replete, but not in lymphocyte-deficient hosts, and although it controls splenomegaly induction in both types of host, long-term protection against FV-induced disease is eventually lost in highly susceptible lymphocyte-deficient hosts. However, the close correlation between the numbers of virus-specific CD4+ T cells and FV spread suggests that FV-specific CD4+ T cells may also exert a direct effect against infection. This idea that virus-specific CD4+ T cells may also be acting independently of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and B cells is further supported by a number of observations. First, although polyclonal antibodies are partly responsible for the difference between control of acute FV infection and lack of control of acute FV/LDV coinfection, FV infection is controlled better than FV/LDV coinfection even in the absence of FV-specific antibodies (36), highlighting a T-cell-mediated mechanism. Second, only the antiviral CD4+ T-cell response rapidly reaches its peak during the first week of infection, whereas the cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell and B-cell response is not yet fully induced. Although coinfection with LDV delays the FV-neutralizing antibody response, this delay is not apparent before the third week of infection (36). FV-neutralizing antibody titers are generally low and not appreciably different between FV-infected and FV/LDV-coinfected mice during the first 2 weeks of infection (36). Moreover, our preliminary data suggested that increasing the frequency of FV-specific CD4+ T cells does not accelerate the cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell and B-cell response in mice infected with FV or coinfected with FV and LDV. Lastly, significant, albeit incomplete, protection is provided by FV-specific CD4+ T cells in lymphocyte-deficient hosts, excluding any contribution from cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and B cells. Furthermore, although long-term protection against FV infection induced by env462-479 peptide immunization is dependent on antibody production, Miyazawa and coworkers did report a short delay in disease induction even in immunized B cell-deficient mice (33).

Virus-specific CD4+ T cells have been shown to acquire direct perforin- or FasL-dependent cytotoxic activity in a number of infection models (9, 22, 30, 45), including infection with FV (27). Furthermore, FV also infects MHC II-expressing cells, such as B cells and macrophages (11, 20, 26), and bone marrow precursors of MHC II-expressing macrophages and dendritic cells (1, 2). However, FV replicates mainly in nucleated erythroid precursors, which do not express MHC class II molecules and would not therefore be directly recognized by FV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nevertheless, it has long been demonstrated that effector CD4+ T cells are an essential contributor to rejection of MHC class II-negative FV-induced tumor cells (15, 16), and CD4+ T cells can be as efficient effectors as cytotoxic CD8+ T cells against a variety of tumors (40, 42, 46). Although this anti-tumor effect of CD4+ T cells is generally attributable to production of IFN-γ (40, 49), our data suggest that the protective effect of virus-specific CD4+ T cells against acute FV infection is largely independent of IFN-γR-signaling, and it would therefore be of interest to further elucidate the mechanisms responsible for the observed antiviral effect of FV-specific CD4+ T cells in this model.

The fate of virus-specific CD4+ T cells during primary retroviral infection of a virus-naive individual may be largely determined by the viral kinetics, with the level of preservation of the CD4+ T-cell response simply reflecting, but not substantially affecting, the viral load (29, 48). Our data suggest that this may be reversible by appropriate vaccination as a sufficiently elevated frequency of virus-specific CD4+ T cells would reduce viral loads enough to prevent their own decline and thus tip the balance toward long-term control. Moreover, protection against FV infection effected by an elevated frequency of antigen-naive CD4+ T cells indicates that sufficient numbers might be the most important attribute of a protective response against overpowering pathogens, such as retroviruses.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. Stoye and members of his lab for advice and members of Biological Services and the Flow Cytometry Facility at the NIMR for their support.

This study was supported by the UK Medical Research Council and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Division of Intramural Research, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 August 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antunes, I., M. Tolaini, A. Kissenpfennig, M. Iwashiro, K. Kuribayashi, B. Malissen, K. Hasenkrug, and G. Kassiotis. 2008. Retrovirus-specificity of regulatory T cells is neither present nor required in preventing retrovirus-induced bone marrow immune pathology. Immunity 29:782-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balkow, S., F. Krux, K. Loser, J. U. Becker, S. Grabbe, and U. Dittmer. 2007. Friend retrovirus infection of myeloid dendritic cells impairs maturation, prolongs contact to naive T cells, and favors expansion of regulatory T cells. Blood 110:3949-3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bock, M., K. N. Bishop, G. Towers, and J. P. Stoye. 2000. Use of a transient assay for studying the genetic determinants of Fv1 restriction. J. Virol. 74:7422-7430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brien, J. D., J. L. Uhrlaub, and J. Nikolich-Zugich. 2008. West Nile virus-specific CD4 T cells exhibit direct antiviral cytokine secretion and cytotoxicity and are sufficient for antiviral protection. J. Immunol. 181:8568-8575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks, D. G., L. Teyton, M. B. A. Oldstone, and D. B. McGavern. 2005. Intrinsic functional dysregulation of CD4 T cells occurs rapidly following persistent viral infection. J. Virol. 79:10514-10527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, D. M., A. M. Dilzer, D. L. Meents, and S. L. Swain. 2006. CD4 T cell-mediated protection from lethal influenza: perforin and antibody-mediated mechanisms give a one-two punch. J. Immunol. 177:2888-2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, S. A., J. L. Hurwitz, A. Zirkel, S. Surman, T. Takimoto, I. Alymova, C. Coleclough, A. Portner, P. C. Doherty, and K. S. Slobod. 2007. A recombinant Sendai virus is controlled by CD4+ effector T cells responding to a secreted human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 81:12535-12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carneiro-Sampaio, M., and A. Coutinho. 2007. Immunity to microbes: lessons from primary immunodeficiencies. Infect. Immun. 75:1545-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casazza, J. P., M. R. Betts, D. A. Price, M. L. Precopio, L. E. Ruff, J. M. Brenchley, B. J. Hill, M. Roederer, D. C. Douek, and R. A. Koup. 2006. Acquisition of direct antiviral effector functions by CMV-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes with cellular maturation. J. Exp. Med. 203:2865-2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesebro, B., W. Britt, L. Evans, K. Wehrly, J. Nishio, and M. Cloyd. 1983. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies reactive with murine leukemia viruses: use in analysis of strains of friend MCF and Friend ecotropic murine leukemia virus. Virology 127:134-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chesebro, B., K. Wehrly, and D. Housman. 1978. Lack of erythroid characteristics in Ia-positive leukemia cell lines induced by Friend murine leukemia virus: brief communication. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 60:239-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosgrove, D., D. Gray, A. Dierich, J. Kaufman, M. Lemeur, C. Benoist, and D. Mathis. 1991. Mice lacking MHC class II molecules. Cell 66:1051-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dittmer, U., D. M. Brooks, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 1999. Requirement for multiple lymphocyte subsets in protection by a live attenuated vaccine against retroviral infection. Nat. Med. 5:189-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douek, D. C., J. M. Brenchley, M. R. Betts, D. R. Ambrozak, B. J. Hill, Y. Okamoto, J. P. Casazza, J. Kuruppu, K. Kunstman, S. Wolinsky, Z. Grossman, M. Dybul, A. Oxenius, D. A. Price, M. Connors, and R. A. Koup. 2002. HIV preferentially infects HIV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nature 417:95-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg, P. D., M. A. Cheever, and A. Fefer. 1981. Eradication of disseminated murine leukemia by chemoimmunotherapy with cyclophosphamide and adoptively transferred immune syngeneic Lyt-1+2− lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 154:952-963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg, P. D., D. E. Kern, and M. A. Cheever. 1985. Therapy of disseminated murine leukemia with cyclophosphamide and immune Lyt-1+,2− T cells. Tumor eradication does not require participation of cytotoxic T cells. J. Exp. Med. 161:1122-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman, Z., M. Meier-Schellersheim, W. E. Paul, and L. J. Picker. 2006. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: what the virus spares is as important as what it destroys. Nat. Med. 12:289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haase, A. T. 1999. Population biology of HIV-1 infection: viral and CD4+ T-cell demographics and dynamics in lymphatic tissues. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:625-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasenkrug, K. J. 1999. Lymphocyte deficiencies increase susceptibility to Friend virus-induced erythroleukemia in Fv-2 genetically resistant mice. J. Virol. 73:6468-6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasenkrug, K. J., D. M. Brooks, and U. Dittmer. 1998. Critical role for CD4+ T cells in controlling retrovirus replication and spread in persistently infected mice. J. Virol. 72:6559-6564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasenkrug, K. J., and B. Chesebro. 1997. Immunity to retroviral infection: the Friend virus model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7811-7816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heemskerk, B., T. van Vreeswijk, L. A. Veltrop-Duits, C. C. Sombroek, K. Franken, R. M. Verhoosel, P. S. Hiemstra, D. van Leeuwen, M. E. Ressing, R. E. M. Toes, M. J. D. van Tol, and M. W. Schilham. 2006. Adenovirus-specific CD4+ T-cell clones recognizing endogenous antigen inhibit viral replication in vitro through cognate interaction. J. Immunol. 177:8851-8859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heemskerk, M. H., M. W. Schilham, H. M. Schoemaker, G. Spierenburg, W. J. Spaan, and C. J. Boog. 1995. Activation of virus-specific major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in CD4-deficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:1109-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hel, Z., J. R. McGhee, and J. Mestecky. 2006. HIV infection: first battle decides the war. Trends Immunol. 27:274-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang, S., W. Hendriks, A. Althage, S. Hemmi, H. Bluethmann, R. Kamijo, J. Vilcek, R. M. Zinkernagel, and M. Aguet. 1993. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-gamma receptor. Science 259:1742-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isaak, D. D., J. A. Price, C. L. Reinisch, and J. Cerny. 1979. Target cell heterogeneity in murine leukemia virus infection. I. Differences in susceptibility to infection with Friend leukemia virus between B lymphocytes from spleen, bone marrow and lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 123:1822-1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwanami, N., A. Niwa, Y. Yasutomi, N. Tabata, and M. Miyazawa. 2001. Role of natural killer cells in resistance against Friend retrovirus-induced leukemia. J. Virol. 75:3152-3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwashiro, M., K. Peterson, R. J. Messer, I. M. Stromnes, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2001. CD4+ T cells and gamma interferon in the long-term control of persistent Friend retrovirus infection. J. Virol. 75:52-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansen, C. A., D. van Baarle, and F. Miedema. 2006. HIV-specific CD4+ T cells and viremia: who's in control? Trends Immunol. 27:119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jellison, E. R., S. K. Kim, and R. M. Welsh. 2005. Cutting edge: MHC class II-restricted killing in vivo during viral infection. J. Immunol. 174:614-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson, A. J., C. F. Chu, and G. N. Milligan. 2008. Effector CD4+ T-cell involvement in clearance of infectious Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 from sensory ganglia and spinal cords. J. Virol. 82:9678-9688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabat, D. 1989. Molecular biology of Friend viral erythroleukemia. Curr. Top. Micriobiol. Immunol. 148:1-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawabata, H., A. Niwa, S. Tsuji-Kawahara, H. Uenishi, N. Iwanami, H. Matsukuma, H. Abe, N. Tabata, H. Matsumura, and M. Miyazawa. 2006. Peptide-induced immune protection of CD8+ T cell-deficient mice against Friend retrovirus-induced disease. Int. Immunol. 18:183-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klenerman, P., and A. Hill. 2005. T cells and viral persistence: lessons from diverse infections. Nat. Immunol. 6:873-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Locksley, R. M., S. L. Reiner, F. Hatam, D. R. Littman, and N. Killeen. 1993. Helper T cells without CD4: control of leishmaniasis in CD4-deficient mice. Science 261:1448-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marques, R., I. Antunes, U. Eksmond, J. Stoye, K. Hasenkrug, and G. Kassiotis. 2008. B lymphocyte activation by coinfection prevents immune control of Friend virus infection. J. Immunol. 181:3432-3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matechak, E. O., N. Killeen, S. M. Hedrick, and B. J. Fowlkes. 1996. MHC class II-specific T cells can develop in the CD8 lineage when CD4 is absent. Immunity 4:337-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyazawa, M., R. Fujisawa, C. Ishihara, Y. A. Takei, T. Shimizu, H. Uenishi, H. Yamagishi, and K. Kuribayashi. 1995. Immunization with a single T helper cell epitope abrogates Friend virus-induced early erythroid proliferation and prevents late leukemia development. J. Immunol. 155:748-758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyazawa, M., S. Tsuji-Kawahara, and Y. Kanari. 2008. Host genetic factors that control immune responses to retrovirus infections. Vaccine 26:2981-2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mumberg, D., P. A. Monach, S. Wanderling, M. Philip, A. Y. Toledano, R. D. Schreiber, and H. Schreiber. 1999. CD4+ T cells eliminate MHC class II-negative cancer cells in vivo by indirect effects of IFN-γ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8633-8638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ney, P. A., and A. D. D'Andrea. 2000. Friend erythroleukemia revisited. Blood 96:3675-3680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ossendorp, F., E. Mengede, M. Camps, R. Filius, and C. J. M. Melief. 1998. Specific T helper cell requirement for optimal induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against major histocompatibility complex class ii negative tumors. J. Exp. Med. 187:693-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oxenius, A., M. F. Bachmann, R. M. Zinkernagel, and H. Hengartner. 1998. Virus-specific MHC-class II-restricted TCR-transgenic mice: effects on humoral and cellular immune responses after viral infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:390-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oxenius, A., R. M. Zinkernagel, and H. Hengartner. 1998. Comparison of activation versus induction of unresponsiveness of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells upon acute versus persistent viral infection. Immunity 9:449-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paludan, C., K. Bickham, S. Nikiforow, M. L. Tsang, K. Goodman, W. A. Hanekom, J. F. Fonteneau, S. Stevanovic, and C. Munz. 2002. Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1-specific CD4+ Th1 cells kill Burkitt's lymphoma cells. J. Immunol. 169:1593-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perez-Diez, A., N. T. Joncker, K. Choi, W. F. N. Chan, C. C. Anderson, O. Lantz, and P. Matzinger. 2007. CD4 cells can be more efficient at tumor rejection than CD8 cells. Blood 109:5346-5354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Picker, L. J. 2006. Immunopathogenesis of acute AIDS virus infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Picker, L. J., and V. C. Maino. 2000. The CD4+ T-cell response to HIV-1. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:381-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qin, Z., and T. Blankenstein. 2000. CD4+ T cell-mediated tumor rejection involves inhibition of angiogenesis that is dependent on IFN-γ receptor expression by nonhematopoietic cells. Immunity 12:677-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahemtulla, A., T. M. Kundig, A. Narendran, M. F. Bachmann, M. Julius, C. J. Paige, P. S. Ohashi, R. M. Zinkernagel, and T. W. Mak. 1994. Class II major histocompatibility complex-restricted T-cell function in CD4-deficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 24:2213-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Recher, M., K. S. Lang, L. Hunziker, S. Freigang, B. Eschli, N. L. Harris, A. Navarini, B. M. Senn, K. Fink, M. Lotscher, L. Hangartner, R. Zellweger, M. Hersberger, A. Theocharides, H. Hengartner, and R. M. Zinkernagel. 2004. Deliberate removal of T-cell help improves virus-neutralizing antibody production. Nat. Immunol. 5:934-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robertson, M. N., G. J. Spangrude, K. Hasenkrug, L. Perry, J. Nishio, K. Wehrly, and B. Chesebro. 1992. Role and specificity of T-cell subsets in spontaneous recovery from Friend virus-induced leukemia in mice. J. Virol. 66:3271-3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robertson, S. J., C. G. Ammann, R. J. Messer, A. B. Carmody, L. Myers, U. Dittmer, S. Nair, N. Gerlach, L. H. Evans, W. A. Cafruny, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2008. Suppression of acute anti-Friend Virus CD8+ T-cell responses by coinfection with lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus. J. Virol. 82:408-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenberg, E. S., J. M. Billingsley, A. M. Caliendo, S. L. Boswell, P. E. Sax, S. A. Kalams, and B. D. Walker. 1997. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T-cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science 278:1447-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santiago, M. L., M. Montano, R. Benitez, R. J. Messer, W. Yonemoto, B. Chesebro, K. J. Hasenkrug, and W. C. Greene. 2008. Apobec3 encodes Rfv3, a gene influencing neutralizing antibody control of retrovirus infection. Science 321:1343-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Savarin, C., C. C. Bergmann, D. R. Hinton, R. M. Ransohoff, and S. A. Stohlman. 2008. Memory CD4+ T-cell-mediated protection from lethal Coronavirus encephalomyelitis. J. Virol. 82:12432-12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schepers, K., M. Toebes, G. Sotthewes, F. A. Vyth-Dreese, T. A. M. Dellemijn, C. J. M. Melief, F. Ossendorp, and T. N. M. Schumacher. 2002. Differential kinetics of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in the regression of retrovirus-induced sarcomas. J. Immunol. 169:3191-3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sparks-Thissen, R. L., D. C. Braaten, S. Kreher, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin IV. 2004. An optimized CD4 T-cell response can control productive and latent Gammaherpesvirus infection. J. Virol. 78:6827-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staprans, S. I., B. L. Hamilton, S. E. Follansbee, T. Elbeik, P. Barbosa, R. M. Grant, and M. B. Feinberg. 1995. Activation of virus replication after vaccination of HIV-1-infected individuals. J. Exp. Med. 182:1727-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Staprans, S. I., A. P. Barry, G. Silvestri, J. T. Safrit, N. Kozyr, B. Sumpter, H. Nguyen, H. McClure, D. Montefiori, J. I. Cohen, and M. B. Feinberg. 2004. Enhanced SIV replication and accelerated progression to AIDS in macaques primed to mount a CD4 T-cell response to the SIV envelope protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:13026-13031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stoye, J. P. 1998. Fv1, the mouse retrovirus resistance gene. Rev. Sci. Technol. 17:269-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valitutti, S., S. Muller, M. Cella, E. Padovan, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1995. Serial triggering of many T-cell receptors by a few peptide-MHC complexes. Nature 375:148-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]