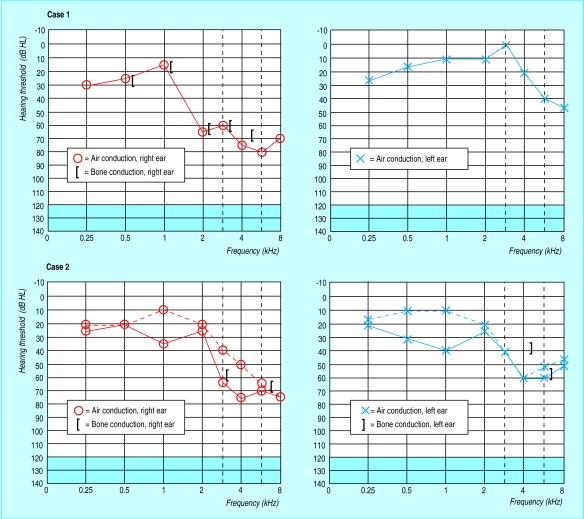

Air bags have contributed substantially to the safety of car occupants in road accidents, but concern exists that they may inflate unnecessarily in low speed crashes.1 Previous articles have reported eye, face, upper limb, and chest injuries caused by air bag inflation.2 Despite the high noise level generated by the bags on inflation, we are aware of only one paper reporting that air bag inflation might induce hearing loss.3 We describe two cases of hearing loss and persistent tinnitus that may have resulted from air bag inflation in low speed collisions. Neither subject sustained other injuries. Audiometry results are shown in the figure.

Case reports

Case 1—

A 38 year old woman was in a collision in the United States while driving at about 20 miles an hour (32 km/h). The air bag struck her on the right side of the face. She noticed an immediate bilateral hearing loss and tinnitus. She also had unsteadiness, which lasted 2 weeks. The hearing on the left improved over the next 5 days but on the right remained impaired and was accompanied by mild, persistent tinnitus. She had noticed no prior hearing loss and had no history of serious illness. Examination was normal, and audiometry showed a bilateral, high frequency, sensorineural hearing loss—much worse in the right ear.

Case 2—

A 68 year old man drove into the back of another vehicle at about 15 mph. The air bag inflated, and he noticed an immediate bilateral hearing loss and tinnitus. He had no history of serious illness except hyperlipidaemia, which was being treated. Examination was normal, and audiometry showed a bilateral, sensorineural hearing loss. His hearing had been tested 18 months earlier as part of a health screen, and the audiogram was available.

Comment

The pre-injury hearing level in case 1 is unknown, but the pattern of the hearing loss, its severity in a woman of this age, and her apparently previously normal hearing strongly suggest a causal link. In case 2, the subject had a pre-existing hearing loss, but his hearing deteriorated substantially in the right ear—at 1 kHz and in the higher frequencies. Alteration of hearing at 1 kHz is unusual but recognised after noise trauma. Both subjects perceived an immediate threshold shift, which decreased in severity with time and so was not as great by the time audiometry was performed.

The inflation of an air bag is triggered by vehicle deceleration and can generate a sound pressure level of 150-170 dB in <100 ms.4 The level depends on the size of car, number of occupants, ventilation, size and number of air bags, and inflation rate. In a study of the effect of air bag “slap” on the ears of squirrel monkeys, the researchers found no permanent hearing damage, ear drum perforation, or disruption of ossicles in air bag velocities of up to 100 mph with a sound pressure level on inflation of 150 dB.5 None the less, this level might cause acoustic trauma in some humans. Cochlear damage may arise from the effects of noise or blast injury. The likelihood of damage depends on the noise level, the exposure time, and individual sensitivity.

Injury from air bags may be more likely in the future. Current safety design is moving towards vehicles with air bags that inflate in frontal and side crashes for both front seat positions. Lack of space means that side air bags inflate very quickly and are closer to the ear.

It is surprising that hearing loss is not reported more frequently after air bag inflation. Any loss identified is perhaps ascribed to other factors associated with a car accident. Also, in an accident the victim is unlikely to register and remember the noise of the air bag. It is therefore unclear whether these cases are isolated or represent a more widespread occurrence.

Figure.

Audiograms for subjects in both cases (pre-exposure thresholds are shown in dotted line for case 2)

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Third report to Congress. Effectiveness of occupant protection systems and their use (http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov:80/cars/rules/rulings/208con2e.html).

- 2.Antosia RE, Partridge RA, Virk AS. Air bag safety. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:794–798. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saunders JE, Slattery WH, III, Luxford WM. Automobile airbag impulse noise: otologic symptoms in six patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:228–234. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)80021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rouhana SW, Webb SR, Wooley RG, McCleary JD, Wood FD, Salva DB. Investigation into the noise associated with air bag deployment. Part 1. Measurement technique and parameter study. Warrendale, PA: Society of Automotive Engineers; 1994. (Report 942218.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter HJ II, Stalnaker RL, Pugh JE Jr. Otologic hazards of airbag restraint system. Society for Automotive Engineers, 1974. (Paper No 741185; can be ordered through the SAE at www.sae.org.)