Abstract

The chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL12) directs leukocyte migration, stem cell homing, and cancer metastasis through activation of CXCR4, which is also a coreceptor for T-tropic HIV-1. Recently, SDF-1 was shown to play a protective role after myocardial infarction, and the protein is a candidate for development of new anti-ischemic compounds. SDF-1 is monomeric at nanomolar concentrations but binding partners promote self-association at higher concentrations to form a typical CXC chemokine homodimer. Two NMR structures have been reported for the SDF-1 monomer, but only one matches the conformation observed in a series of dimeric crystal structures. In the other model, the C-terminal helix is tilted at an angle incompatible with SDF-1 dimerization. Using a rat heart explant model for ischemia/reperfusion injury, we found that dimeric SDF-1 exerts no cardioprotective effect, suggesting that the active species is monomeric. To resolve the discrepancy between existing models, we solved the NMR structure of the SDF-1 monomer in different solution conditions. Irrespective of pH and buffer composition, the C-terminal helix remains tilted at an angle with no evidence for the perpendicular arrangement. Furthermore, we find that phospholipid bicelles promote dimerization that necessarily shifts the helix to the perpendicular orientation, yielding dipolar couplings that are incompatible with the NOE distance constraints. We conclude that interactions with the alignment medium biased the previous structure, masking flexibility in the helix position that may be essential for the distinct functional properties of the SDF-1 monomer.

Keywords: NMR, bicelle, dipolar coupling, chemokine, monomer–dimer equilibrium, myocardial infarction

Introduction

Chemokines are a family of ∼50 small, secreted proteins that function as chemoattractants, directing leukocyte trafficking in normal immune function and a variety of disease states.1–3 They target a family of ∼20 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which enable cells to migrate in response to a chemokine concentration gradient.1–3 Beyond their normal roles in the innate immune system, chemokines and chemokine receptors participate in inflammatory diseases, HIV infection, and cancer progression, prompting numerous efforts to develop novel chemokine receptor antagonists for therapeutic use. For example, the CXC chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1, also known as CXCL12) and its receptor CXCR4 are essential for proper fetal development.4–6 CXCR4 is also the major coreceptor for T-tropic (X4) strains of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), and SDF-1 inhibits HIV-1 infection.7–10 Additionally, SDF-1 signaling mediates cancer cell migration and metastasis, and CXCR4 inhibition reduces metastatic tumor formation in a mouse model for human breast cancer.11

Following myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, it has recently been observed that there is an increased expression of SDF-1 in cardiac myocytes, endothelial cells, smooth muscle, and fibroblasts.12–14 The cardioprotective properties of SDF-1, which are observed both pre- and postischemic event, include reduced infarct zone, decreased scar tissue, increased angiogenesis, resistance to hypoxia/reoxygenation damage, and improved cardiac function.13–18 Cardioprotection by SDF-1 is evident in vitro and in vivo and two mechanisms of action have been proposed: SDF-1 may activate growth and survival signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes directly13,14 or enhance cardiac regeneration by recruiting hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells into the heart.12,18–22 Various methods for SDF-1 administration in ischemic tissue are currently in development. These include: SDF-1 attached to poly(ethylene glycol)-fibrin patches,18 self-assembling nanofibers with a timed SDF-1 release mechanism,15 and viruses engineered to produce SDF-1.12 In each case, SDF-1 treatment is effective, but variations in the protective effect may be dose-related.

SDF-1 exists in a monomer–dimer equilibrium that shifts toward dimer upon crystallization23–25 and in the presence of various binding partners,26 including an extracellular domain of its receptor CXCR4.27,28 To investigate the structure–function relationships of the two oligomeric states, we generated a symmetric disulfide-linked dimer [SDF-1(L36C/A65C)]27 and a preferentially monomeric variant (H25R).26 Surprisingly, the preferentially monomeric SDF-1 variant showed enhanced activity relative to the wild-type protein, whereas the constitutive dimer inhibited chemotactic responses to the wild-type chemokine.27 In this work, measurements of cardioprotection using the same SDF-1 variants also suggest that the monomeric species is primarily responsible for this effect. However, differences in the 3D structures of the SDF-1 monomer solved previously by NMR spectroscopy create uncertainty in the correct model for the CXCR4 agonist.27

Chemokine tertiary structure consists of a flexible N-terminus connected by an extended “N-loop” and a turn of 310-helix to a three-stranded β-sheet and a C-terminal α-helix. Four chemokine subclasses, C, CC, CXC, and CX3C, are distinguished by the spacing of conserved cysteines linking the N-terminus to the β-sheet. Most chemokines self-associate, with CC dimerization typically mediated by residues near the N-terminus. In contrast, CXC dimers are linked by the β1 strands to form a six-stranded sheet with the C-terminal helices crossing the dimer interface in an antiparallel arrangement.2

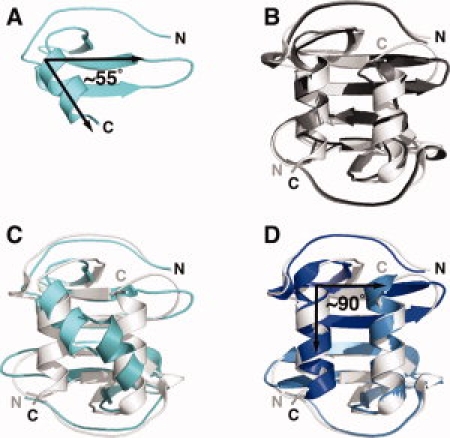

In the original SDF-1 structure solved by 2D NMR at pH 4.9, the α-helix and β-sheet are oriented at a ∼55° angle29 [Fig. 1(A)]. This configuration is incompatible with the CXC-type dimer observed in subsequent SDF-1 crystal structures25,30,31 [Fig. 1(B)], because the helices from each subunit of the dimer would clash with each other [Fig. 1(C)]. In a newer structure of the SDF-1 monomer solved at pH 5.5 using 3D heteronuclear NMR methods,32 the helix and sheet are perpendicular and superimposable on a subunit of the crystal structures [Fig. 1(D)].32 Noting this agreement with the SDF-1 dimer, Gozansky et al.32 argued that their model is more accurate than the original structure by Crump et al. owing to the use of [U-13C,15N]-enriched protein and refinement against residual dipolar coupling (RDC) constraints. Until this discrepancy is resolved with additional data showing that one of the NMR structures is incorrect or by identifying differences in solution conditions that alter the protein conformation, key aspects of the SDF-1 structure remain unclear.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of SDF-1 solution and crystal structures. (A) NMR structure of SDF-1 solved at pH 4.9 in acetate buffer (PDB ID 1SDF). The C-terminal α-helix and the strands of the β-sheet lie at an angle of ∼55°. (B) Three X-ray crystal structures (1A15, black; 1QG7, gray; 2J7Z, white) display the same SDF-1 dimeric arrangement. (C) Two copies of the SDF-1 monomer from (A) (cyan) superimposed on the SDF-1 dimer (white). (D) The SDF-1 NMR structure solved at pH 5.5 in phosphate buffer (PDB ID 1VMC; blue) superimposes with a Cα r.m.s.d. of 1.0 Å on the SDF-1 crystallographic dimer 2J7Z.

Concentration-dependent 15N relaxation measurements by Baryshnikova and Sykes33 indicated that even in the absence of monomer–dimer exchange the SDF-1 monomer undergoes millisecond–microsecond conformational fluctuations. Flexibility at the base of the SDF-1 helix would permit exchange between a unique conformation compatible with dimer formation (helix angle = 90°) and others that are not (helix angle < 90°). We speculated that the distinct helix positions in the two published structures reflect intrinsic conformational dynamics of the SDF-1 monomer and that the range of accessible conformations might be sensitive to changes in solution conditions.

Our previous work showed that the SDF-1 dimer is stabilized in solution by phosphate, sulfate, and other binding partners.26,28 One of the NMR structures (1SDF) was solved in acetate buffer at pH 4.9, whereas the 1VMC structure used 50 mM phosphate at pH 5.5. To understand why this important chemokine structure remains in dispute, we measured histidine pKa values and determined the solution structure of the SDF-1 monomer in the presence and absence of phosphate. We also investigated the effect of phospholipid bicelles on the SDF-1 conformation and oligomeric state. Our results show that NOE-based refinement of the SDF-1 monomer at pH 5.5 yields a helix position intermediate to the previous models. Furthermore, we find that RDC constraints bias the SDF-1 monomer structure toward a conformation consistent with the crystallographic dimers because bicelles promote SDF-1 dimer formation.

Results

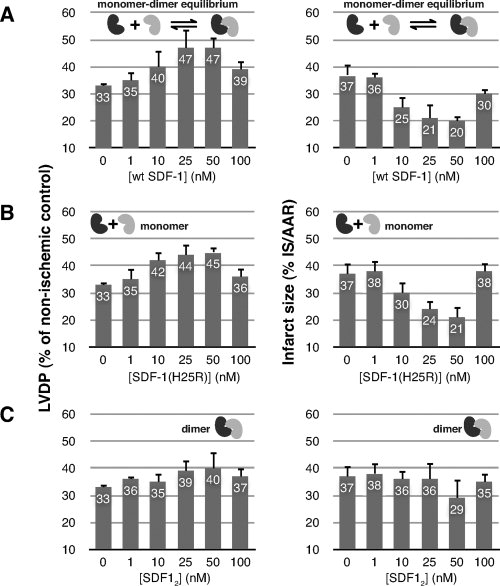

Monomeric SDF-1 is cardioprotective

We used an isolated, buffer-perfused rat heart explant model to assess the direct cardioprotective effects of pretreatment with wild-type SDF-1, preferentially monomeric SDF-1(H25R)26 and a constitutive SDF-1 dimer, SDF-1(L36C/A65C) (SDF12).27 Aerobic cardiac function (heart rate, coronary flow rate, and developed pressure) was measured before ischemia, and increased resistance to injury from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion was determined from reduction in infarct size and increased recovery of developed pressure relative to untreated control hearts. Wild-type SDF-1 [Fig. 2(A)] and the H25R mutant [Fig. 2(B)] show significant dose-dependent cardioprotection at 25 and 50 nM concentrations as indicated by infarct size and left ventricle diastolic pressure (LVDP). In contrast, the SDF12 dimer was less active at the tested concentrations [Fig. 2(C)], suggesting that monomeric SDF-1 is required for resistance to ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Figure 2.

Monomeric SDF-1 is cardioprotective. Perfused explanted rat hearts were pretreated (15 min) with (A) wild-type SDF-1, (B) a preferentially monomeric SDF-1 variant [SDF-1(H25R)], or (C) disulfide-locked SDF-1 dimer [SDF-1(L36C/A65C)]. Left ventricle developed pressure (LVDP) (left) and infarct size (right) were measured after global, no-flow ischemia (25 min) and subsequent reperfusion (180 min).

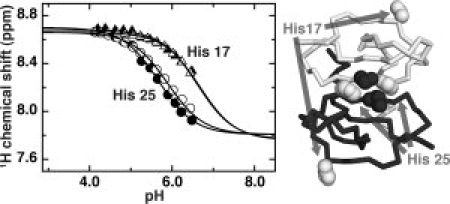

Histidine pKa values for SDF-1

The quaternary structure of SDF-1 is highly sensitive to changes in solution conditions. SDF-1 self-association occurs when electrostatic repulsion at the dimer interface is balanced by ions like phosphate or sulfate, combined with deprotonation of His 25 to the neutral species.26 Both of the previous NMR structures were solved at acidic pH (4.9 and 5.5), where His 25 is likely to be positively charged because the histidine pKa values are typically six or higher. However, histidine pKa values in proteins vary widely, and we speculated that proximity to other positively charged residues (Lys 24, Lys 27, and Arg 41) or the presence of 50 mM phosphate could depress the His 25 pKa. To determine whether differences in solution conditions could alter the structure of SDF-1, we monitored the protonation state of His 25 as a function of pH and phosphate concentration.

We determined histidine pKa values by nonlinear fitting of 1H and 15N chemical shifts to a modified Henderson–Hasselbalch equation (see Fig. 3). Chemical shift and pKa values measured in 0 and 50 mM phosphate for both histidines are listed in Table I. His 17, located far from the SDF-1 dimer interface, has a pKa of 6.6 in the presence and absence of phosphate. In contrast, the pKa of His 25, which participates in the dimer interface, is lower by nearly a full pH unit (5.7). At the pH values used for previous NMR structures, the fraction of positively charged His 25 ranges from ∼90% at pH 4.9 (1SDF) to only ∼50% at pH 5.5 (1VMC). Thus, the His 25 protonation state may contribute to structural differences, but our previous work suggested that phosphate could have an even more pronounced effect on conformation.

Figure 3.

Electrostatic repulsion alters the His 25 pKa. Hɛ1 chemical shifts from His 17 (triangles) and His 25 (circles) plotted as a function of pH. Equation (1) was used to fit the deprotonated chemical shift, protonated chemical shift, and pKa of the respective nuclei to changes in the monitored chemical shift as a function of pH. Solution conditions were 1 mM SDF-1 in either 0 mM sodium phosphate (open) or 50 mM sodium phosphate (filled). The lower pKa of His 25 reflects its proximity to Lys 27 of the opposing subunit (dark spheres) across the dimer interface, in contrast to the unperturbed pKa of His 17 located far from the interface.

Table I.

Histidine Side Chain 1H and 15N Chemical Shifts and pKa Values in 0 and 50 mM Phosphate

| Residue | Atom | Sodium phosphate (mM) | pKa | δAH+ (ppm) | δA (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| His 25 | Hɛ1 | 0 | 5.7 | 8.6988 | 7.8069 |

| 50 | 5.9 | 8.6604 | 7.8069 | ||

| Hδ2 | 0 | 5.6 | 7.3276 | 6.9035 | |

| 50 | 5.8 | 7.2817 | 6.9239 | ||

| Nɛ2 | 0 | 5.7 | 189.5488 | 194.7319 | |

| 50 | 5.7 | 189.5682 | 194.3376 | ||

| His 17 | Hɛ1 | 0 | 6.6 | 8.6791 | 7.7668 |

| 50 | 6.7 | 8.6586 | 7.7599 | ||

| Hδ2 | 0 | 6.5 | 7.4307 | 7.060 | |

| 50 | 6.7 | 7.4061 | 7.0288 | ||

| Nɛ2 | 0 | 6.7 | 189.1804 | 193.0362 | |

| 50 | 6.6 | 189.2218 | 192.720 |

Monomeric SDF-1 structures with and without phosphate

Phosphate, sulfate, and other SDF-1 binding partners have a dramatic stabilizing effect on the dimeric state.26 We speculated that the presence of 50 mM phosphate in the 1VMC solution conditions and its absence in the 1SDF solution could be responsible for the structural difference. To test this hypothesis, we solved the NMR structure of SDF-1 at pH 5.5 in the presence and absence of 50 mM sodium phosphate. Although we expected to see significant differences in helix orientation, our structures of SDF-1 in 0 or 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.5) superimpose with a Cα RMSD of 0.3 Å for residues 9–66 [Fig. 4(A)]. Refinement statistics for each structure are summarized in Supporting Information Tables I and II. In comparison with the Gozansky et al. (blue) and Crump et al. (cyan) structures, the helix is tilted at an intermediate angle [Fig. 4(B,C)].

Figure 4.

Solution structures of SDF-1 at 0 and 50 mM sodium phosphate. (A) Structures of SDF-1 in 0 mM (salmon; PDB ID 2KED) and 50 mM (red; PDB ID 2KEC) sodium phosphate at pH 5.5. (B) Solution structure of SDF-1 at pH 5.5 in 0 mM sodium phosphate (salmon) overlaid onto the SDF-1 structures 1VMC(blue) and 1SDF(cyan). (C) Solution structure of SDF-1 at pH 5.5 in 50 mM sodium phosphate (red) overlaid onto the SDF-1 structures 1VMC(blue) and 1SDF (cyan).

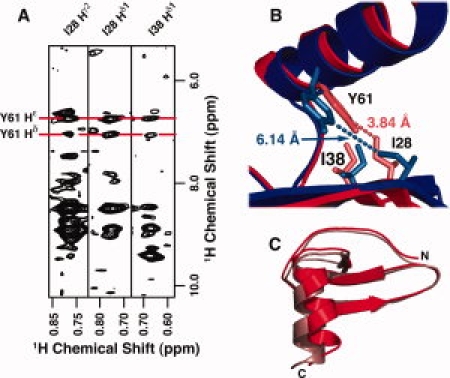

NOEs define the SDF-1 helix position

To determine why our structure of SDF-1 in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.5) disagrees with the 1VMC structure solved under identical solution conditions, we compared the restraints used in calculating the structures and found a key difference. A set of NOEs in the 3D 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC links Tyr 61 to the methyl groups of Ile 28 and Ile 38 [Fig. 5(A)]. Restraints between Tyr 61 and Ile 28 or Ile 38 were not present in the 1VMC restraint list*, and inspection of the 1VMC structure shows that the corresponding distances between the aromatic protons of Tyr 61 and the Hδ1 methyl protons of either Ile 28 or Ile 38 are >5.5 Å [Fig. 5(B)], whereas our NOE-derived restraints require distances <5.5 Å. Structures computed without the Tyr 61-Ile 28 and Tyr 61-Ile 38 restraints more closely resembled the 1VMC structure [Fig. 5(C)]. We concluded that these NOEs linking hydrophobic core residues of the C-terminal α-helix and β-sheet define a different helix position than the one reported by Gozansky et al. [Fig. 5(B,C)].

Figure 5.

NOEs linking Y61 to I28 and I38 define the SDF-1 helix position. (A) Strips from a 3D 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC showing NOEs between the Hδ1 and Hɛ1 protons of Y61 and the Hδ methyl protons of I28 and I38. (B) NOE-derived distance restraints between the Y61 Hδ and Hɛ protons and the Hδ methyl protons of I28 and I38 (light red) define a different helix position (red) than that observed in 1VMC (blue) where the Y61-I28 and Y61-I38 distances exceed 5 Å (light blue). (C) Comparison of SDF-1 structures in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 5.5 computed with (red) or without (pink) distance restraints derived from the Y61-I28 and Y61-I38 NOEs in (A).

RDCs constrain the SDF-1 helix in the 1VMC structure

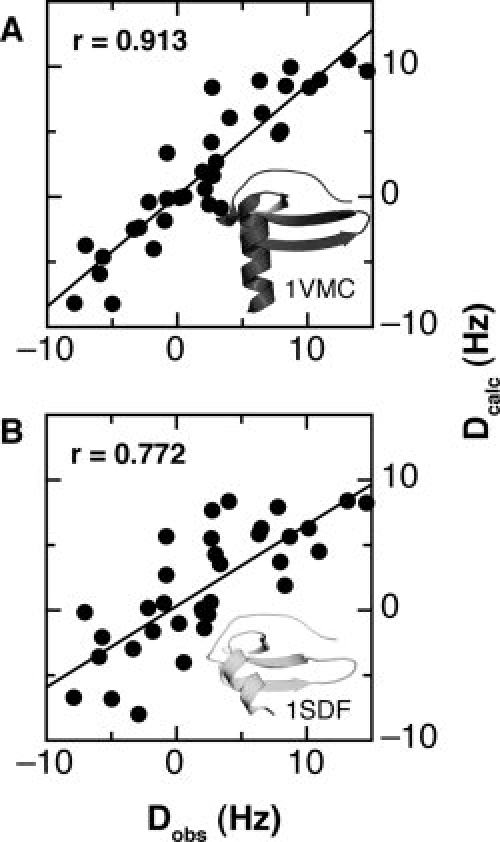

Restraints from RDCs were used to solve the 1VMC structure.32 We measured 1H-15N RDCs for SDF-1 under the same conditions using 5% DMPC/DHPC bicelles and compared the observed couplings with each SDF-1 solution structure. Figure 6 shows correlation plots of observed RDC values (Dobs) and calculated RDC values (Dcalc) for the 1VMC and 1SDF structures. As expected, Dcalc values from the 1VMC structure had the highest correlation with Dobs values (r = 0.913), whereas 1SDF had the lowest correlation (r = 0.772). Our SDF-1 structures determined in 0 and 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.5) had intermediate correlation coefficients (r = 0.838 and 0.846, respectively). Overall, the relationship between correlation coefficient and helix angle suggests that RDC restraints contributed to the perpendicular orientation observed in the 1VMC structure.

Figure 6.

Correlation of measured RDC values with 1VMC and 1SDF. Residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) were measured in 5% DMPC/DHPC bicelles and in isotropic (water) solution on 0.25 mM SDF-1 at 35°C. Singular value decomposition of the 35 measured RDC values was then used to calculate RDCs for the 1VMC and 1SDF structures and best-fit alignment tensors. Plots of the measured RDCs (Dobs) versus the calculated RDCs (Dcalc), and the respective structures are shown for (A) 1VMC and (B) 1SDF. Pearson's correlation coefficients for the 1VMC and 1SDF structures are 0.913 and 0.772, respectively.

Bicelles promote SDF-1 dimer formation

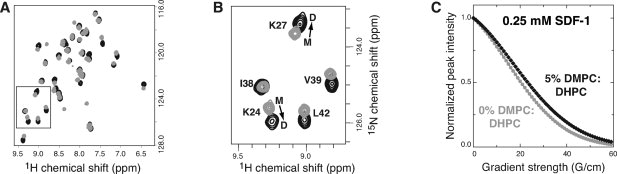

DMPC/DHPC bicelles form a liquid crystalline medium that orients with the magnetic field that is meant to induce a small degree of molecular alignment without altering the structure of the protein under investigation.34–37 To examine whether phospholipids used for RDC measurement could affect the helix configuration, we looked for evidence of changes in the SDF-1 structure in the presence of bicelles. A comparison of 15N-1H HSQC spectra of SDF-1 in the presence and absence of bicelles revealed noticeable chemical shift changes [Fig. 7(A)], suggesting that the DMPC/DHPC bicelles may influence the SDF-1 structure. We previously demonstrated that 1H and 15N shifts of K24 and K27, which lie in the β1-strand and contribute to the dimer interface, report on the SDF-1 oligomeric state.26 Addition of DMPC/DHPC bicelles shifted the peaks for K24 and K27 in a direction consistent with an increasing population of SDF-1 dimer [Fig. 7(B)].

Figure 7.

DMPC/DHPC bicelles promote SDF-1 dimer formation. (A) 15N-1H HSQC spectra of SDF-1 in the absence (gray) or presence (black) of 5% DMPC/DHPC bicelles (2.8:1 molar ratio). (B) Chemical shifts of residues at the dimer interface report on the oligomeric state of SDF-1. In the absence of bicelles, chemical shifts for K24 and K27 are consistent with monomer (M) but shift toward dimer (D) in the presence of DMPC/DHPC bicelles (2.8:1 molar ratio). (C) Differences in translational self-diffusion coefficients measured for 0.25 mM SDF-1 suggest that oligomerization is favored in the presence of bicelles. Nonlinear fitting of peak intensities from a series of 1D 1H spectra acquired in the absence (gray) and presence of DMPC/DHPC bicelles (black) using a longitudinal encode-decode pulse field gradient diffusion scheme (diffusion delay Δ = 80 ms; gradient pulse Δ = 5 ms) yielded self diffusion coefficients (Ds) of 1.74 × 10−6 and 1.42 × 10−6 cm2 s−1.

Pulse field gradient measurements of translational self-diffusion coefficients (Ds) confirmed the observation that DMPC/DHPC bicelles promote SDF-1 dimer formation. A decrease in the Ds value from 1.74 × 10−6 to 1.42 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 accompanied the addition of 5% DMPC/DHPC (2.8:1) bicelles to a sample of 0.25 mM SDF-1 at pH 7 [Fig. 7(C)]. To estimate the contribution of self-aggregation to the SDF-1 self-diffusion coefficient, we also measured diffusion in 5% DMPC/DHPC (2.8:1) bicelles for constitutively dimeric SDF-1(L36C/A65C) (15.9 kDa; Ds = 1.04 × 10−6 cm2 s−1) and ubiquitin (8.6 kDa; Ds = 1.70 × 10−6 cm2 s−1). Using Ds,ubiquitin and Ds,SDF-1α(L36C/A65C) as representative standards for monomer and dimer self-diffusion coefficients in the presence of DMPC/DHPC bicelles, we estimated the contribution of the dimeric species to the measured Ds value to be ∼40% at 0.250 mM SDF-1. At higher SDF-1 concentrations, most of the protein would be dimeric. Hence, restraints derived from RDCs measured in DMPC/DHPC bicelles will reflect significant contributions from the SDF-1 dimer.

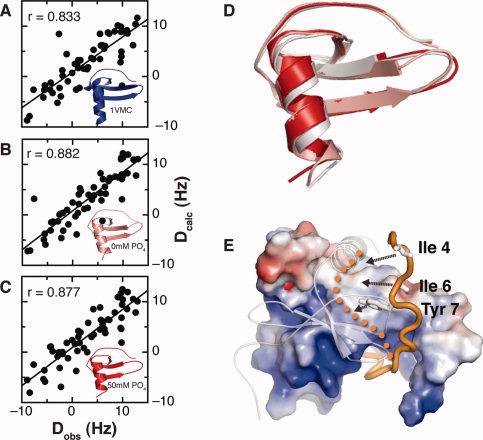

In DMPC/DHPC bicelles, RDC values could be determined for only 35 residues because of selective line broadening of many signals including four residues in the C-terminal helix. To discourage electrostatic interactions between SDF-1 (calculated pI = 9.9) and the negatively charged DMPC/DHPC bicelles, we measured 1H-15N RDCs in a fresh preparation of DMPC/DHPC bicelles doped with tetradecyltrimethylammonium bromide (TTAB), a cationic lipid, at lower pH (5.5 instead of 7.0) in an effort to prevent SDF-1 dimer formation. Addition of TTAB restored most of the broadened signals yielding RDCs for 55 residues, including all 12 residues of the helix (57–68). Comparison of Dobs measured in the TTAB/DMPC/DHPC bicelles with Dcalc shows the best correlation with our structures in 0 and 50 mM sodium phosphate (r = 0.882 and 0.877, respectively) compared with the 1VMC structure (r = 0.833) [Fig. 8(A–C)]. Although these RDC values agreed best with our SDF-1 structures, PFG diffusion measurements suggest that the addition of TTAB does not eliminate SDF-1 interactions with the phospholipid bicelles. To avoid bias or distortion from bicelle-induced conformational changes, we omitted RDC restraints from the refinement of SDF-1 NMR structures presented here.

Figure 8.

RDCs in TTAB/DMPC/DHPC bicelles are consistent with monomeric structure. RDC values measured in 0.8 mM TTAB, 5% DMPC/DHPC, and 10% 2H2O (pH 5.5). TTAB was added to minimize electrostatic interactions between bicelles and SDF-1, and the pH was lowered to shift the monomer–dimer equilibrium toward monomer. Plots of the RDCs measured in TTAB/DMPC/DHPC versus the calculated RDCs for 1VMC (A), 2KED (B), and 2KEC (C), and the respective structures are shown. A total of 55 RDC values were measured. The Pearson's correlation coefficients for the 1VMC, 2KED, and 2KEC structures are 0.833, 0.882, and 0.877. (D) Overlay of SDF-1 structures solved in 20 mM MES at pH 6.8 (gray; PDB ID 2KEE), 0 mM sodium phosphate at pH 5.5 (salmon; PDB ID 2KED), and 50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 5.5 (red; PDB ID 2KEC). (E) NMR structure of the SDF-1 locked dimer in complex with the CXCR4 N-terminus (orange). One SDF-1 subunit is illustrated with electrostatic potential surface and the opposing monomer is represented by a transparent ribbon. Tyrosine 7 of CXCR4 occupies a pocket at the dimer interface, but Ile 4 and Ile 6 do not make specific contacts with the SDF-1 dimer surface. Dissociation of the dimer reveals a hydrophobic surface that could be occupied by Ile 4, Ile 6, and Tyr 7 upon rearrangement of the CXCR4 N-terminus (orange dots).

SDF-1 structure at pH 6.8

Previous NMR structures were solved at acidic pH in an effort to prevent complications from the SDF-1 monomer–dimer equilibrium. However, we showed previously that SDF-1 is monomeric at near-neutral pH in organic buffers like MES and TRIS.26 To define the monomeric state at a more physiologically relevant pH, we solved the structure of SDF-1 at pH 6.8 in 20 mM MES buffer, conditions where His 25 is uncharged. The SDF-1 structure at pH 6.8 superimposes on the structures solved in 0 and 50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 5.5 with Cα r.m.s.d. values of 0.7 and 0.6 Å, respectively [Fig. 8(D)]. In each case, overlays of the NMR monomers on the SDF-1 dimer indicate that overlap between C-terminal helices of the opposing subunits would prevent self-association (data not shown).

Discussion

Full activation of chemokine receptors is thought to depend exclusively on binding of the monomeric ligand.38,39 Yet oligomerization is essential for in vivo chemokine function,39–42 presumably to support immobilization on cell-surface glycosaminoglycans (GAG). Interference with chemokine oligomerization and GAG binding can be used to create anti-inflammatory molecules, as demonstrated by CC chemokine variants that block leukocyte recruitment by the wild-type chemokine in vivo.43,44 Here, we show that a constitutively dimeric form of SDF-1 exerts none of the cardioprotective activity conferred by the wild-type chemokine or a preferentially monomeric mutant (H25R). Interestingly, SDF-1 is less effective at the highest concentration tested (100 nM) than at 10–50 nM, consistent with the bell-shaped activity profile observed in previous measurements of leukocyte chemotaxis.27 This reinforces and extends our recent discovery that, although monomeric SDF-1 fully activates CXCR4 to induce chemotaxis, dimerization of SDF-1 creates a partial CXCR4 agonist that inhibits chemotaxis toward wild-type SDF-1.27 In addition, because our measurements of ischemia/reperfusion injury were performed using explanted hearts, these results suggest that monomeric SDF-1 exerts a direct, prosurvival effect on cardiomyocytes, in addition to mobilization of cardiac progenitor cells that may occur in vivo. Interactions that promote SDF-1 dimerization may reduce its beneficial effects, and we speculate that SDF-1 variants that resist dimerization may be useful anti-ischemic compounds. Accurate three-dimensional structures of chemokines are invaluable tools in the design of novel mimics or inhibitors and are necessary to establish structure–function relationships for the monomeric and oligomeric species. To understand how the SDF-1 monomer binds and activates CXCR4, it was necessary to resolve a discrepancy between the published 1SDF and 1VMC structural models in the orientation of the C-terminal α-helix.

We solved the NMR structure of monomeric SDF-1 at pH 5.5 in buffers containing either 0 or 50 mM phosphate and found close agreement between the two structures (see Fig. 4). However, the intermediate helix angle in our models (75° relative to the β-sheet) was distinct from both published structures, which show the helix at either 90° (1VMC) or 55° (1SDF) (see Fig. 1). In NOESY spectra acquired under identical conditions, we assigned long-range NOEs that are incompatible with the 1VMC structure and found that distance restraints corresponding to those NOEs were not used to calculate that model. Chemical shift differences and self-diffusion measurements revealed that phospholipid bicelles used for RDC measurements in the Gozansky study32 promote SDF-1 dimerization (see Fig. 7). As illustrated in Figure 1(C), SDF-1 dimerization is incompatible with the monomeric conformations observed in the original NMR structure of Crump et al.,29 as well as the new structures we present here. We concluded that RDC restraints used in the 1VMC refinement do not describe the structure of monomeric SDF-1 but instead bias the helix toward the perpendicular orientation found in crystal structures of the dimer. RDC restraints can improve the accuracy of NMR structures. However, as others have cautioned, a suitable alignment medium must not interact strongly with the molecule under study to avoid distortions or errors in the resulting structural model.37 In this instance, we were alerted to bicelle-SDF-1 binding by chemical shift perturbations and line broadening in the HSQC spectrum. Doping the negatively charged DMPC/DHPC bicelles with the cationic lipid TTAB restored the majority of missing peaks in the HSQC, presumably by weakening electrostatic interactions with the highly basic SDF-1 protein.

The difference in helix angle between the original model from Crump et al.29 and our solution structures of SDF-1 may reflect real variations in the SDF-1 conformation, particularly if a fully charged His 25 at pH 4.9 shifts the helix to a more acute angle than the other structures measured at or above the pKa of His 25. NMR relaxation measurements by Baryshnikova and Sykes33 suggest that the SDF-1 monomer exists in a conformational equilibrium between two states, only one of which is compatible with dimer formation. We hypothesize that the helix position responds to interactions with SDF-1 binding partners, which can in turn shift the monomer–dimer equilibrium.

In particular, we showed previously that the CXCR4 N-terminal domain promotes SDF-1 dimerization by forming specific contacts with both subunits of the dimer.27,28 However, residues at the extreme CXCR4 N-terminus participate in unique interactions with monomeric SDF-1 that are not accounted for in the structure of a dimeric 2:2 complex.27 Residues 3–9 show the largest chemical shift perturbations in a titration of 15N-labeled N-terminal CXCR4 peptide with wild-type SDF-1,28 but Tyr 7 is the only residue in this region that makes a specific contact with the locked SDF-1 dimer.27 Figure 8(E) shows how the dimer interface conceals a hydrophobic surface on the SDF-1 monomer that could interact with apolar residues at the CXCR4 N-terminus. We hypothesize that when monomeric SDF-1 binds to CXCR4, Ile 4 and Ile 6 of the receptor dock into the hydrophobic cleft exposed upon dissociation of the SDF-1 dimer. This hydrophobic surface is largest when the helix angle is 90° and smaller when the helix pivots to a position incompatible with dimer formation. When monomeric SDF-1 encounters CXCR4, recognition by the receptor N-terminus may shift the helix angle toward the perpendicular arrangement. SDF-1 dimerization and rearrangement of the first few residues of CXCR4 would then be permitted, depending on the concentration of the chemokine. By defining the three-dimensional structure of monomeric SDF-1, the results presented here lay the foundation for future studies of the dynamics of molecular recognition in the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling system, as well as efforts to design SDF-1 variants with novel functional properties.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

SDF-1 was produced as previously described.26–28,45 Briefly, N-terminal hexa-His-tagged SDF-1 was expressed as insoluble inclusion bodies in E. coli and purified using metal affinity chromatography. Refolding of SDF-1 was done either while immobilized to a metal affinity column or in solution as described previously.45 Tobacco etch virus protease cleavage of the N-terminal hexa-His tag was followed by reverse phase HPLC purification to >98% homogeneity.

Cyanogen bromide cleavage to generate biologically active SDF-127,28,45 was omitted for these structural studies because the flexible SDF-1 N-terminus does not interact with the folded chemokine domain or influence the monomer–dimer equilibrium.24–27,32 Hence, SDF-1 used for structural studies contained an N-terminal Gly-Ser dipeptide for the structure solved in 25 mM MES at pH 6.8 or an N-terminal gly-met dipeptide for the structures solved in either 0 mM sodium phosphate at pH 5.5 or 50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 5.5.

Cardioprotection assay

Isolated rat hearts were perfused for 15 min, followed by aerobic perfusion with SDF-1 variants 15 min prior to 25 min global, no-flow ischemia and 180 min reperfusion. Hearts subjected to the perfusion sequence in the absence of SDF-1 served as ischemic controls. Hearts perfused continuously for 245 min served as nonischemic controls. The perfusion sequence was administered as previously described in Baker et al.46,47 Each dosage group consisted of six replicates. Resistance to injury from myocardial infarction/reperfusion was determined by a reduction in infarct size and increase in recovery of developed pressure.

Following 3-h reperfusion, hearts were removed from the perfusion apparatus and prepared for infarct size measurement as previously described.46,47 Briefly, hearts were sliced across the long axis of the left ventricle, from apex to base, into 2-mm-thick transverse sections and then incubated in 1% triphenyltetrazolium chloride in phosphate buffer (pH 7.3) at 38°C for 20 min. Infarcted tissue was visually enhanced by storage in 10% formaldehyde solution for 24 h before analysis. Infarcted tissue and the area at risk were surgically removed and measured in a blinded manner; tissue volumes were calculated by multiplying the weight of planimetered area by cross-section thickness and expressed as a percentage of left ventricular volume. Cardiac function was recorded continuously throughout each experiment as previously described.46,47 End-diastolic pressure was initially set at 3 mmHg for 2 min. The balloons were progressively inflated with a microsyringe to set end-diastolic pressures to 8 mmHg for the left ventricle and 3 mmHg for the right ventricle. Developed pressure was recorded during steady-state conditions. Coronary flow rate was measured throughout the experiment by timed collections of the coronary effluent from the right side of the heart into a graduated cylinder.

Determination of histidine pKa values

NMR experiments were performed on 0.5 mL solutions of 10% 2H2O, 1 mM protein, and 0 or 50 mM sodium phosphate. The pH was adjusted by adding either HCl or NaOH and was measured before each experiment. The protonation state of the nitrogen atoms of the imidazole ring of His 17 and His 25 was measured by a modified HCN experiment.48 The HCN technique utilizes the scalar coupling 1JCH and 1JCN for sequential magnetization transfer from imidazole ring 1H to 13C to 15N and reverse, resulting in a 2D spectrum correlating carbon-bonded protons to imidazole nitrogens. Changes in Hɛ1, Hδ2, Nɛ2, and Nδ1 chemical shifts as a function of pH were used for pKa determination. NMR data were analyzed with the program pro Fit 5.6 (QuantumSoft, Switzerland) and pH titration data were fitted to a modified Henderson–Hasselbalch equation:

| (1) |

in which δobs is the observed chemical shift at each pH value, and δAH+ and δA are the chemical shifts when the imidazole nitrogens are fully protonated or deprotonated, respectively.

Structure determination

Samples for structure determination contained [U-15N,13C]-SDF-1 in either 0 mM sodium phosphate at pH 5.5, 50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 5.5, or 25 mM MES at pH 6.8 at protein concentrations of 1.6, 1.6, and 1.2 mM, respectively. Standard NMR techniques were used for generating chemical shift assignments for SDF-1.49 3D 15N-edited NOESY-HSQC, 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC, and 13C(aromatic)-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra (τmix = 80 ms) were used to generate distance constraints. TALOS was used to generate backbone dihedral angle constraints from 1Hα, 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, and 15N chemical shifts.50 The NOEASSIGN module of the torsion angle dynamics program CYANA was used to determine initial structures and was followed by iterative manual refinement to eliminate constraint violations.51 X-PLOR was used for further refinement, in which physical force field terms and explicit water solvent molecules were added to the experimental constraints.52 Refinement and validation statistics for each ensemble of 20 conformers are given in Supporting Information Tables I–III, and they also list the statistics for Procheck-NMR validation of the final 20 conformers.

Self-diffusion measurements

Measurements of the self-diffusion coefficients, Ds, for SDF-1, SDF-1(L36C/A65C), and ubiquitin were acquired using a water-suppressed longitudinal encode-decode (water-sLED) experiment.53 A 1% (w/v) sample of β-cyclodextrin in 90% H2O and 10% 2H2O, with a diffusion coefficient 3.239 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 at 25°C,54 was used as a standard for gradient strength calibration. The diffusion delay was 80 ms, and the gradient pulse length was 5 ms. The gradient strength was varied from 10 to 80% in 1% intervals with 58.97 G cm−1 as the maximum (100%) gradient strength. Nonlinear least-squares fitting was used to obtain self-diffusion coefficients (Ds) from the following equation:

| (2) |

where γ is the magnetogyric ratio of 1H, δ is the gradient pulse length, G is the gradient intensity, and Δ is the diffusion delay.

RDC measurements

1H-15N RDCs were measured using an in-phase, anti-phase pulse scheme.55 The difference between 1JNH + DNH splittings recorded in anisotropic (5% bicelles, 2.8:1 DMPC/DHPC) and isotropic (water) solvent yields the RDC. Samples in both anisotropic and isotropic solvents contained 0.250 mM SDF-1 in 10% 2H2O (pH 7.0) at 35°C; bicelles were suspended and aligned according to Fleming and Matthews.37 Alignment was confirmed by monitoring the quadrupolar splitting of the HDO 2H resonance. Using the DC module of the NMRPipe program,56 alignment parameters were fitted via singular value decomposition with the dipolar interaction held constant at −21,585 Hz. Thirty-four RDCs were extracted and compared to various SDF-1 structures. Additional RDC measurements were performed in 5% DHPC/DMPC bicelles doped with 0.8 mM TTAB at pH 5.5. Under these conditions, 55 RDC values were extracted for comparison with SDF-1 structures.

Acknowledgments

NMR parameters for each SDF-1 structure have been deposited in the BioMagResBank with accession numbers 16142 (SDF-1 50 mM phosphate, pH 5.5), 16143 (SDF-1 0 mM phosphate, pH 5.5), and 16145 (SDF-1, pH 6.8).

Footnotes

References

- 1.Baggiolini M. Chemokines in pathology and medicine. J Intern Med. 2001;250:91–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez EJ, Lolis E. Structure, function, and inhibition of chemokines. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:469–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091901.115838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossi D, Zlotnik A. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:217–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Takakura N, Nishikawa S, Kitamura Y, Yoshida N, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature. 1996;382:635–638. doi: 10.1038/382635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tachibana K, Hirota S, Iizasa H, Yoshida H, Kawabata K, Kataoka Y, Kitamura Y, Matsushima K, Yoshida N, Nishikawa S, Kishimoto T, Nagasawa T. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature. 1998;393:591–594. doi: 10.1038/31261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 1998;393:595–599. doi: 10.1038/31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleul CC, Farzan M, Choe H, Parolin C, Clark-Lewis I, Sodroski J, Springer TA. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTR/fusin and blocks HIV-1 entry. Nature. 1996;382:829–833. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Souza MP, Harden VA. Chemokines and HIV-1 second receptors. Confluence of two fields generates optimism in AIDS research. Nat Med. 1996;2:1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Souza MP, Cairns JS, Plaeger SF. Current evidence and future directions for targeting HIV entry: therapeutic and prophylactic strategies. JAMA. 2000;284:215–222. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, Barrera JL, Mohar A, Verastequi E, Zlotnik A. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbott JD, Huang Y, Liu D, Hickey R, Krause DS, Giordano FJ. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha plays a critical role in stem cell recruitment to the heart after myocardial infarction but is not sufficient to induce homing in the absence of injury. Circulation. 2004;110:3300–3305. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147780.30124.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu X, Dai S, Wu WJ, Tan W, Zhu X, Mu J, Guo Y, Bolli R, Rokosh G. Stromal cell derived factor-1 alpha confers protection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: role of the cardiac stromal cell derived factor-1 alpha CXCR4 axis. Circulation. 2007;116:654–663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxena A, Fish JE, White MD, Yu S, Smyth JW, Shaw RM, DiMaio JM, Srivastava D. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha is cardioprotective after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117:2224–2231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.694992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segers VF, Tokunou T, Higgins LJ, MacGillivray C, Gannon J, Lee RT. Local delivery of protease-resistant stromal cell derived factor-1 for stem cell recruitment after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:1683–1692. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.718718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasaki T, Fukazawa R, Ogawa S, Kanno S, Nitta T, Ochi M, Shimizu K. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha improves infarcted heart function through angiogenesis in mice. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:966–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch KC, Schaefer WM, Liehn EA, Rammos C, Mueller D, Schroeder J, Dimassi T, Stopinski T, Weber C. Effect of catheter-based transendocardial delivery of stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha on left ventricular function and perfusion in a porcine model of myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2006;101:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang G, Nakamura Y, Wang X, Hu Q, Suggs LJ, Zhang J. Controlled release of stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha in situ increases c-kit+ cell homing to the infarcted heart. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2063–2071. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penn MS, Zhang M, Deglurkar I, Topol EJ. Role of stem cell homing in myocardial regeneration. Int J Cardiol. 2004;95(Suppl 1):S23–S25. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(04)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi J, Kusano KF, Masuo O, Kawamoto A, Silver M, Murasawa S, Bosch-Marce M, Masuda H, Losordo DW, Isner JM, Asahara T. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 effects on ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cell recruitment for ischemic neovascularization. Circulation. 2003;107:1322–1328. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055313.77510.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hattori K, Heissig B, Tashiro K, Honjo T, Tateno M, Shieh JH, Hackett NR, Quitoriano MS, Crystal RG, Rafii S, Moore MA. Plasma elevation of stromal cell-derived factor-1 induces mobilization of mature and immature hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells. Blood. 2001;97:3354–3360. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heissig B, Hattori K, Dias S, Friedrich M, Ferris B, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, Besmer P, Lyden D, Moore MA, Werb Z, Rafii S. Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell. 2002;109:625–637. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00754-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dealwis C, Fernandez EJ, Thompson DA, Simon RJ, Siani MA, Lolis E. Crystal structure of chemically synthesized [N33A] stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha, a potent ligand for the HIV-1 “fusin” coreceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6941–6946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohnishi Y, Senda T, Nandhagopal N, Sugimoto K, Shioda T, Nagal Y, Mitsui Y. Crystal structure of recombinant native SDF-1alpha with additional mutagenesis studies: an attempt at a more comprehensive interpretation of accumulated structure-activity relationship data. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:691–700. doi: 10.1089/10799900050116390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryu EK, Kim TG, Kwon TH, Jung ID, Ryu D, Park YM, Kim J, Ahn KH, Ban C. Crystal structure of recombinant human stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha. Proteins. 2007;67:1193–1197. doi: 10.1002/prot.21350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veldkamp CT, Peterson FC, Pelzek AJ, Volkman BF. The monomer-dimer equilibrium of stromal cell-derived factor-1 (CXCL 12) is altered by pH, phosphate, sulfate, and heparin. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1071–1081. doi: 10.1110/ps.041219505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veldkamp CT, Seibert C, Peterson FC, De la Cruz NB, Haugner JC, III, Basnet H, Sakmar TP, Volkman BF. Structural basis of CXCR4 sulfotyrosine recognition by the chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12. Sci Signal. 2008;1:ra4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1160755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veldkamp CT, Seibert C, Peterson FC, Sakmar TP, Volkman BF. Recognition of a CXCR4 sulfotyrosine by the chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha (SDF-1alpha/CXCL12) J Mol Biol. 2006;359:1400–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crump MP, Gong JH, Loetscher P, Rajarathnam K, Amara A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Virelizier JL, Baggiolini M, Sykes BD, Clark-Lewis I. Solution structure and basis for functional activity of stromal cell-derived factor-1; dissociation of CXCR4 activation from binding and inhibition of HIV-1. EMBO J. 1997;16:6996–7007. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohnishi Y, Senda T, Nandhagopal N, Sugimoto K, Shioda T, Nagal Y, Mitsui Y. Crystal structure of recombinant native SDF-1alpha with additional mutagenesis studies: an attempt at a more comprehensive interpretation of accumulated structure-activity relationship data. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:691–700. doi: 10.1089/10799900050116390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dealwis C, Fernandez EJ, Thompson DA, Simon RJ, Siani MA, Lolis E. Crystal structure of chemically synthesized [N33A] stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha, a potent ligand for the HIV-1 “fusin” coreceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6941–6946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gozansky EK, Louis JM, Caffrey M, Clore GM. Mapping the binding of the N-terminal extracellular tail of the CXCR4 receptor to stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baryshnikova OK, Sykes BD. Backbone dynamics of SDF-1alpha determined by NMR: interpretation in the presence of monomer-dimer equilibrium. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2568–2578. doi: 10.1110/ps.062255806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjandra N, Bax A. Direct measurement of distances and angles in biomolecules by NMR in a dilute liquid crystalline medium. Science. 1997;278:1111–1114. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tjandra N, Omichinski JG, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM, Bax A. Use of dipolar 1H-15N and 1H-13C couplings in the structure determination of magnetically oriented macromolecules in solution. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:732–738. doi: 10.1038/nsb0997-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ottiger M, Bax A. Characterization of magnetically oriented phospholipid micelles for measurement of dipolar couplings in macromolecules. J Biomol NMR. 1998;12:361–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1008366116644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleming K, Matthews S. Media for studies of partially aligned states. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;278:79–88. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajarathnam K, Sykes BD, Kay CM, Dewald B, Geiser T, Baggiolini M, Clark-Lewis I. Neutrophil activation by monomeric interleukin-8. Science. 1994;264:90–92. doi: 10.1126/science.8140420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen SJ, Crown SE, Handel TM. Chemokine: receptor structure, interactions, and antagonism. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:787–820. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoogewerf AJ, Kuschert GS, Proudfoot AE, Borlat F, Clark-Lewis I, Power CA, Wells TN. Glycosaminoglycans mediate cell surface oligomerization of chemokines. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13570–13578. doi: 10.1021/bi971125s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campanella GS, Grimm J, Manice LA, Colvin RA, Medoff BD, Wojtkiewicz GR, Weissleder R, Luster AD. Oligomerization of CXCL10 is necessary for endothelial cell presentation and in vivo activity. J Immunol. 2006;177:6991–6998. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Proudfoot AE, Handel TM, Johnson Z, Lau EK, LiWang P, Clark-Lewis I, Borlat F, Wells TN, Kosco-Vilbois MH. Glycosaminoglycan binding and oligomerization are essential for the in vivo activity of certain chemokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1885–1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334864100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Handel TM, Johnson Z, Rodrigues DH, Dos Santos AC, Cirillo R, Muzio V, Riva S, Mack M, Deruaz M, Borlat F, Vitte PA, Wells TN, Teixeira MM, Reoudfoot AE. An engineered monomer of CCL2 has anti-inflammatory properties emphasizing the importance of oligomerization for chemokine activity in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:1101–1108. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson Z, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Herren S, Cirillo R, Muzio V, Zaratin P, Carbonatto M, Mack M, Smailbegovic A, Rose M, Lever R, Page C, Wells TN, Proudfoot AE. Interference with heparin binding and oligomerization creates a novel anti-inflammatory strategy targeting the chemokine system. J Immunol. 2004;173:5776–5785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Veldkamp CT, Peterson FC, Hayes PL, Mattmiller JE, Haugner JC, III, de la Cruz N, Volkman BF. On-column refolding of recombinant chemokines for NMR studies and biological assays. Protein Expr Purif. 2007;52:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker JE, Curry BD, Olinger GN, Gross GJ. Increased tolerance of the chronically hypoxic immature heart to ischemia. Contribution of the KATP channel. Circulation. 1997;95:1278–1285. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.5.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker JE, Konorev EA, Gross GJ, Chilian WM, Jacob HJ. Resistance to myocardial ischemia in five rat strains: is there a genetic component of cardioprotection? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1395–H1400. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sudmeier JL, Ash EL, Gunther UL, Luo X, Bullock PA, Bachovchin WW. HCN, a triple-resonance NMR technique for selective observation of histidine and tryptophan side chains in 13C/15N-labeled proteins. J Magn Reson B. 1996;113:236–247. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Markley JL, Ulrich EL, Westler WM, Volkman BF. Macromolecular structure determination by NMR spectroscopy. Methods Biochem Anal. 2003;44:89–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herrmann T, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:209–227. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linge JP, Williams MA, Spronk CA, Bonvin AM, Nilges M. Refinement of protein structures in explicit solvent. Proteins. 2003;50:496–506. doi: 10.1002/prot.10299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Altieri AS, Hinton DP, Byrd RA. Association of biomolecular systems via pulsed field gradient NMR self-diffusion measurements. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:7566–7567. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uedaira H, Uedaira H. Translational frictional coefficients of molecules in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem. 1970;74:2211–2214. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ottiger M, Delaglio F, Bax A. Measurement of J and dipolar couplings from simplified two-dimensional NMR spectra. J Magn Reson. 1998;131:373–378. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]