Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus CzrA is a zinc-dependent transcriptional repressor from the ubiquitous ArsR family of metal sensor proteins. Zn(II) binds to a pair of intersubunit C-terminal α5-sensing sites, some 15 Å distant from the DNA-binding interface, and allosterically inhibits DNA binding. This regulation is characterized by a large allosteric coupling free energy (ΔGc) of approximately +6 kcal mol−1, the molecular origin of which is poorly understood. Here, we report the solution quaternary structure of homodimeric CzrA bound to a palindromic 28-bp czr operator, a structure that provides an opportunity to compare the two allosteric “end” states of an ArsR family sensor. Zn(II) binding drives a quaternary structural switch from a “closed” DNA-binding state to a low affinity “open” conformation as a result of a dramatic change in the relative orientations of the winged helical DNA binding domains within the dimer. Zn(II) binding also effectively quenches both rapid and intermediate timescale internal motions of apo-CzrA while stabilizing the native state ensemble. In contrast, DNA binding significantly enhances protein motions in the allosteric sites and reduces the stability of the α5 helices as measured by H-D solvent exchange. This study reveals how changes in the global structure and dynamics drive a long-range allosteric response in a large subfamily of bacterial metal sensor proteins, and provides insights on how other structural classes of ArsR sensor proteins may be regulated by metal binding.

Keywords: allosteric coupling, allostery, metal sensor protein, metalloregulation, NMR solution structure

Metal ion homeostasis is a complex process that involves maintaining a delicate balance between metal uptake/efflux and other metal storage systems to meet the needs of the cell (1, 2). This process is tightly regulated at the level of transcription by means of specific metal-dependent transcriptional regulators that respond to changes in metal ion concentrations in the host environment (3). In Staphylococcus aureus, the czr operon encodes a CDF antiporter, CzrB, a homolog of Escherichia coli zinc transporter YiiP that confers resistance to Zn(II) and Co(II) (4, 5), and the metal-regulated repressor, CzrA (6, 7). CzrA binds Zn(II) with picomolar affinity and strong negative homotropic cooperativity (8, 9) and is thought to undergo a conformational change that alleviates transcriptional repression of the resistance gene czrB.

CzrA belongs to the ubiquitous ArsR (or ArsR/SmtB) family of metalloregulators found in many bacterial genomes that sense a wide variety of metals including biologically essential metals as well as toxic metal pollutants (10, 11). Members of this family appear to adopt a common winged helix-turn-helix homodimeric fold, but have evolved physically and structurally distinct pairs of allosteric metal-sensing sites (2, 12). These sites are thought to have arisen as a result of convergent evolution due to evolutionary pressures (12), a finding consistent with the “rule of varied allosteric control” in which protein families evolve seemingly random allosteric control pathways (13). CzrA and its homolog SmtB in Synechococcus (14) are α5 sensors that bind Zn(II) ions in two rotationally symmetric tetrahedral coordination sites formed by pairs of metal ligands derived from the α5 helix of each subunit (8). The crystal structure of CzrA and SmtB in the apo and the Zn(II)-bound states have been solved (8). Although the structures of CzrA were found to be very similar in these two states, SmtB revealed measurable differences in quaternary structure in which the apo form adopted a comparatively “flat” conformation not well suited to interact with canonical B-form DNA (8, 15). The structural and thermodynamic underpinnings of metalloregulation for any member of the ubiquitous ArsR family remains poorly understood due to a lack of detailed insight for the DNA operator-bound state (3).

We report here the NMR solution structure of CzrA in its DNA operator-bound state, a 42-kDa complex. The quaternary structure of CzrA in the DNA-bound state reveals that metal binding drives a “closed-to-open” conformational change. In addition, dynamics measurements suggest that DNA binding induces long-range disorder in the allosteric metal sites due in part to a less well-packed α5 helical interface; in contrast, Zn(II) binding globally quenches backbone motions well into the DNA-binding surface. These findings provide insights into allosteric metalloregulation in CzrA, as well as a better understanding of metal induced allosteric control of DNA binding by other metal sensors from the ubiquitous ArsR family.

Results

CzrA Binds a 28-bp DNA from the czr O/P Region.

Comparison of a series of 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra with several duplex DNAs ranging in length from 22–41 bp and containing the conserved core sequence (5′-TGAAxxxxxxTTCA) revealed that a 2-fold symmetric 28-bp operator fragment represented the minimal high-affinity CzrA DNA-binding unit. Fluorescence anisotropy experiments confirm these findings and reveal a 1:1 (dimer:DNA) stoichiometry and an affinity (Ka) of 6.8 × 1010 M−1 (Table 1), a finding consistent with previous studies (9).

Table 1.

czr operator (CzrO) DNA binding parameters for wild-type and mutant CzrAs

| CzrA | Kobs, M−1 | ro* | rP2·D | Fold-decrease in Kobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 6.7 (±0.9) × 1010 | 0.118 | 0.136 | 1.0 |

| Q53A | 6.2 (±1.1) × 109 | 0.106 | 0.121 | 11 |

| V42A | 4.3 (±0.3) × 108 | 0.105(1) | 0.120(1) | 160 |

| Q53E | 1.4 (±0.3) × 107 | 0.118 | 0.138 | 4800 |

| S54A | 6.6 (±0.8) × 105 | 0.1042(3) | 0.1205† | 100,000 |

| S57A | 1.3 (±0.2) × 105 | 0.1122(3) | 0.1295† | 520,000 |

| H58A | 1.7 (±0.3) × 106 | 0.1118(7) | 0.1295† | 39,000 |

| S57A/H58A | 1.6 (±0.2) × 105 | 0.1125(2) | 0.1300† | 420,000 |

Measured using a fluorescence anisotropy-based assay like that shown in Fig. 4B using a fluorescein-labeled 28-bp CzrO DNA duplex (see Methods). The parameters reflect the results from two or three independent titrations fitted to a dimer-linkage model with Kdimer fixed to the wild-type CzrA value of 1.7 × 105 M−1 under these solution conditions (31).

*The numbers in parentheses are the standard error on the fitted ri value(s) around the last significant figure; if not shown, this number is <1. Conditions: 10 mM Hepes, 0.4 M NaCl, pH 7.0, 25.0 (± 0.1) °C (9, 31).

†Fixed to the value that reflects the Δr (0.018) from the wild-type CzrA titration because saturation was not obtained for these mutant CzrAs.

Quaternary Structure of DNA-Bound CzrA.

The molecular weight of the CzrA-DNA complex (∼42 kDa) required a highly perdeuterated CzrA sample to solve the solution structure of DNA-bound CzrA. To do this, we used a well-established approach in which the only nonexchangeable protons in the molecule derive from the methyl groups of Val, Leu, and Ile residues (16–19). Since we were concerned with detecting what could be small changes in CzrA quaternary structure upon ligand binding, we first determined the solution structure of the Zn(II)-bound CzrA homodimer and compared that with the crystal structure (8). A superposition of the 20 lowest-energy structures (Fig. S1A) reveals excellent statistics (Table S1) and an overall fold similar to that of crystal structure (Fig. S1A). Interestingly, the solution structure of the dimer is slightly more open than in the crystal structure, with a global backbone r.m.s. difference between the two of 2.05 Å (Fig. S1B), a result consistent with a statistical analysis of the long-range orientational restraints (1DNH) (Fig. S1C).

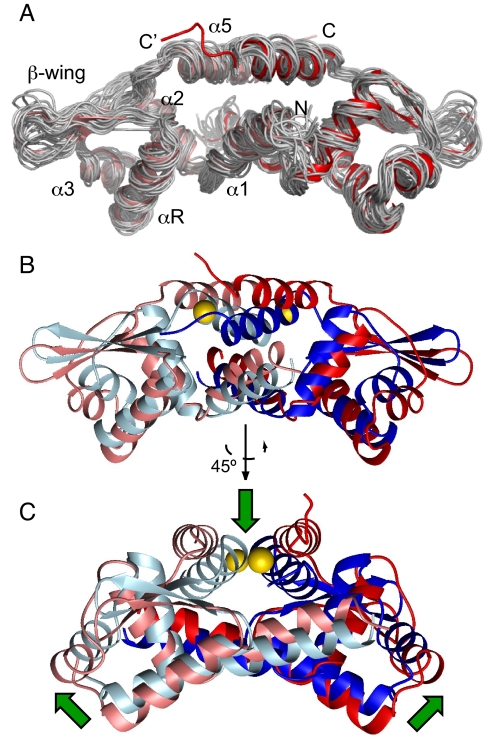

Fig. 1A shows the backbone superposition of 20 lowest-energy structures along with the ribbon diagram of the mean structure of DNA-bound CzrA calculated on the basis of experimental constraints (Table S2 and Fig. S1D). A ribbon representation of the global superposition of DNA-bound CzrA and the crystal structure of Zn(II) CzrA is shown in Fig. 1B. DNA-bound CzrA retains the overall architecture of CzrA, which adopts a winged helix-turn-helix fold. However, the quaternary structure of DNA bound CzrA differs dramatically from Zn(II) CzrA. In comparing the two states, the entire wing domain including the recognition head undergoes a pendulum-like motion, involving a significant rotation and translation of one protomer relative to the other. This results in a detectably poorer interprotomer packing of the C-terminal allosteric α5 helices distal to the DNA-binding site, resulting in an overall “closed” conformation (defined by the αR-αR' interprotomer distance) that enables the reading head α-helices (αR) to interact with the major groove of the DNA. Binding of Zn(II) to the pair of symmetry-related α5 sites (Fig. 1C) drives the pendulum in the opposite direction to a more “open” conformation that reestablishes the tight packing of the α1-α5 core of the dimer, which in turn, likely leads to the loss of specific major groove interactions (see below).

Fig. 1.

Solution structure of CzrO DNA-bound CzrA. (A) Backbone heavy atom (N, Cα, and C') overlay of 20 lowest-energy structures of DNA bound CzrA (see Table S2 for structure statistics; unstructured residues 100–103 of the bundle are not shown in this view for clarity). The ribbon diagram in the overlay represents the mean structure of the ensemble and the two subunits are shaded salmon and red. (B) Ribbon diagram representation of the global overlay of DNA bound CzrA and the crystal structure of Zn(II) CzrA (8). The subunits of DNA bound CzrA are colored as in A and the two subunits of Zn(II) CzrA are colored slate and blue. Zn(II) ions are colored yellow. (C) Another view of the same overlay as in B (rotated 45°) and the green arrows represent the direction of the quaternary structural change.

Comparison of DNA- and Zn(II)-Bound States with Apo-CzrA.

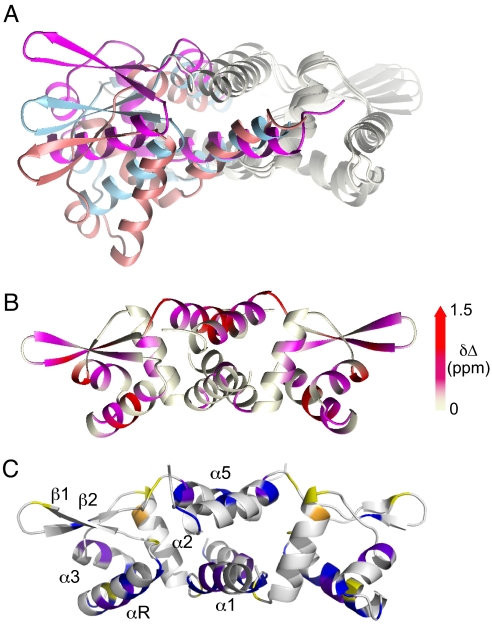

Although the crystallographic structures of apo- and Zn(II) CzrAs are virtually identical to one another (8), the degree to which apo-CzrA differs from Zn(II) CzrA in solution is unknown. The structure of apo SmtB, a homologous α5 metal sensor, shows a more “open” quaternary structure that is characterized by a longer αR-αR' interprotomer distance than in Zn(II) SmtB or Zn(II) CzrA (Fig. 2A). A chemical shift perturbation map (Fig. 2B) reveals that the binding of DNA drives a global perturbation of the quaternary structure in apo-CzrA, with these changes not limited to the αR reading heads and the β-wing region, but instead extending to the distal metal binding sites in the α5 helix; this result is consistent with the structure (Fig. 1). In contrast, the magnitude of the chemical shift changes upon Zn(II) binding are quantitatively smaller and localized to the α5 helix and the C-terminal region of the αR helix, the latter mediated by a proposed intersubunit hydrogen-bonding pathway critical for allosteric coupling (8, 9, 20). This suggests that Zn(II) binding results in only a small change in the global structure of apo-CzrA and/or simply reduces the structural heterogeneity of the conformational ensemble in the absence of DNA (see below).

Fig. 2.

Distinct conformational states of α5 metal sensor proteins. (A) Overlay of the apo SmtB (magenta ribbon), Zn(II)-bound CzrA (light blue ribbon) and DNA-bound CzrA (salmon ribbon). The “right” subunit is overlaid to better show the quaternary structural differences. (B) Effect of binding DNA on apo CzrA structure is mapped using a 1H HN chemical shift perturbation experiment. Colors on the ribbon are ramped according to Δδ ppm as follows: gray, Δδ<0.2 ppm; magenta, 0.2<Δδ<0.8 and red; 0.8<Δδ<1.5 ppm. (C) A comparison of the short time scale 15N relaxation dynamics of Zn2 CzrA vs. apo-CzrA (see Fig. S2 for primary data). Blue, increased S2 by ≥ 0.02 on Zn(II) binding; yellow, decreased S2 by ≤ –0.02 on Zn(II) binding; purple, residues in apo-CzrA that exhibit measurable Rex ≥ 1 s−1 that is completely dampened upon Zn(II) binding; orange, the single residue in Zn2 CzrA for which there is measurable Rex ≥ 1 s−1 (L35).

Induced Flexibility in the Allosteric Metal-Binding Sites in DNA-Bound CzrA.

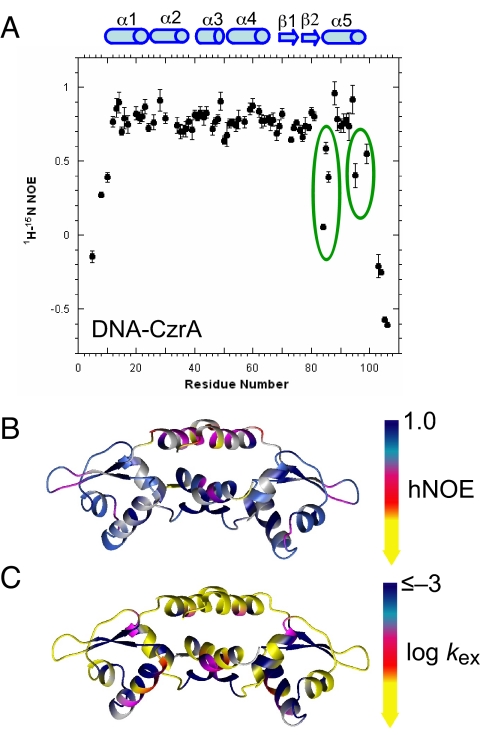

Fast motion dynamics provides insights into conformational entropy and ultimately, the underlying energetics of allostery (21–23). It was therefore of interest to compare the backbone dynamics of Zn2 and DNA-bound forms of CzrA to a common reference state, apo-CzrA, in an effort to determine the degree to which dynamics “fingerprints” of these two states might differ from one another. We first compared these short time scale backbone dynamics of apo-CzrA vs. Zn2 CzrA, focusing on the magnitude of the order parameter S2 and the number of those residues characterized by non-zero Rex, that is, those residues potentially experiencing (μs-ms) intermediate exchange line broadening (Fig. S2). Although the pattern of S2 vs. residue number is very similar for these two forms of CzrA, the binding of Zn(II) detectably “stiffens” the backbone in the α5 metal binding sites, as expected, but also into the αR, and to a lesser degree, the α1 helices, as evidenced by a ΔS2 values (S2Zn – S2apo) ≥0.02 (24) (Fig. 2C). Zn(II) binding also effectively eliminates the conformational exchange broadening and residue-specific dynamic heterogeneity in apo-CzrA, much of which is localized to the α1 and αR helices, i.e., those regions destined to interact with the DNA (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2D). In contrast, motional disorder of the β-hairpin appears complex in both apo- and Zn2 CzrA (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2D). This situation contrasts sharply with that of DNA-bound CzrA. Fig. 3A shows {1H}-15N hNOE values for the DNA-bound CzrA. Amide bonds (NH) that are immobile over this time scale show NOE values greater than or equal to 0.8, whereas those NH bonds that experience internal motions in subnanosecond time scale show lower hNOE values. Two non-overlapping clusters of residues on opposite sides of the allosteric α5 helices in DNA-bound CzrA, for example, zinc ligands D84 and H86, and I95 and N99 are characterized by lower hNOE values, and a comparison to unbound apo-CzrA reveals that all experience enhanced disorder in the DNA-bound state (Fig. S3 A–C). The amide protons of L68, in the linker between the αR helix and β1 strand, a proposed key allosteric residue (8), and A88 and Q93 in the α5 helices are also conformationally exchanged broadened (Fig. S3D). Additional evidence for this is a dramatic lack of sequential NOEs in the α5 helices (Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

Fast motion dynamics and hydrogen-deuterium (H-D) exchange rates for DNA-bound CzrA. (A) The 1H-15N steady-state heteronuclear NOE (hNOE) of DNA-CzrA complex. The region where there are pronounced internal motions are highlighted with solid circles. (B) Mapping of the hNOE values on ribbon diagram of DNA-bound CzrA. The colors are ramped as follows: dark blue, hNOE ≥ 0.8, light blue, 0.7 ≤ hNOE <0.8; magenta, 0.6 ≤ hNOE <0.7; red, 0.4 ≤ hNOE <0.6; yellow, NOE <0.4. Gray shading, no information due to spectral overlap. (C) Mapping of the H-D exchange rates (as log kex, h–1) on a ribbon diagram of DNA-bound CzrA. The colors are ramped as follows and correspond to roughly linear free energy increments: yellow, –0.2 ≤ log kex < 0.75; red, –0.9 ≤ log kex < –0.2; magenta, –1.6 ≤ log kex < –0.9; light blue, –2.3 ≤ log kex < –1.6; dark blue, log kex < –2.3.

A map of the H-D exchange rates on the structure of DNA-bound CzrA reveals, as anticipated, a slowing of the exchange rates of structured elements that form part of the DNA-binding site, with the possible exception of the β-wing tip region (Fig. 3C). In contrast, amide protons in the α5 helices in the allosteric ligand binding sites, for example, are comparatively less protected from solvent exchange relative to apo-CzrA (8) with kex measurable for just one residue in this helix (A91) in the complex. These dynamics could strongly influence the shift in the native populations to the open or closed state (23), and suggest that DNA binding is effectively communicated to the allosteric sites via long-range dynamic disorder and native-state destabilization (24–26), likely as a consequence of a large structural change in this region of the molecule (Fig. 1).

Key Determinants of High-Affinity, Specific Binding of Apo-CzrA to the czr Operator.

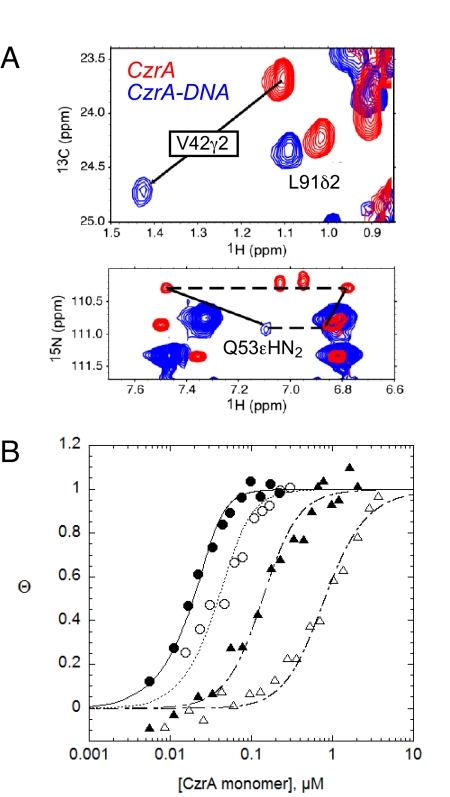

Although the methyl labeling strategy limits structural information available for the protein-DNA interface, the distribution of the intermolecular NOEs are fully consistent with a model in which the DNA binding interface is defined by the C-terminal region of the α1 helix, the N-terminal region of the α3 and αR helices, and the N-terminal region of the β2 strand (Fig. S5). In particular, the NMR data suggest that the side chains of V42, the invariant N-terminal residue of the α3 helix, and Q53, the second residue in the αR helix interact directly with the DNA major groove (Fig. 4A). A structure-based multiple sequence alignment of apo-CzrA with three MerR family proteins bound to their respective DNA operators (27–29), was therefore used to identify other candidate DNA-binding residues in CzrA (Fig. S6). This alignment makes the prediction that invariant residues S54, S57, and H58 in the N-terminal region of the αR helix would make key intermolecular contacts to conserved bases in the 5′-TGAA core sequence found in each DNA half-site (30).

Fig. 4.

CzrO binding isotherms for wild-type and mutant CzrAs. (A) Overlay of the same selected region of 1H-13C HMQC spectra (Upper) the 1H-15N TROSY spectra (Lower) acquired for apo-CzrA (red cross peaks) and the CzrA-CzrO complex (blue cross peaks) illustrating the large shifts in the side chains of Val-42 and Gln-53 upon binding DNA. (B) Representative CzrO binding isotherms obtained for wild-type (filled circles), Q53A (open circles), V42A (filled triangles) and Q53E (Δ) CzrAs. The continuous line through each data set represents a nonlinear least squares fit to a dissociable dimer model with the parameters compiled in Table 1.

To test this, we purified Ala substitution mutants of V42, Q53, S54, S57, and H58 and measured their CzrO DNA binding affinities (Ka) using the same 28-bp DNA used for the NMR experiments (Fig. 4B, Table 1, and Fig. S7). Control experiments reveal that each mutant CzrA binds stoichiometric Co(II) which confirms the homodimeric structural integrity of each mutant (Fig. S7A). Using a simple dimer linkage model (Kdimer = 1.7 × 105 M−1) (31), we find that Ka is reduced approximately 11-fold for Q53A and 160-fold for V42A CzrAs (Fig. 4B). Although the Q53A mutant suggests a relatively local modulation of the binding interface due to a loss of a potential hydrogen-bonding residue (Q53), the V42A mutant reveals a stronger disruption of the interface. Finally, the S54A, S57A, H58A, and S57A/H58A CzrAs bind operator DNA with a very low affinity similar to that of the fully inhibited Zn(II) CzrA (Fig. S7B and Table 1) (9). These data likely define the protein-DNA interface for all α5-site ArsR-family repressors, and are fully consistent with a proposed model of the protein-DNA interface (Fig. S6).

Discussion

The molecular basis that underlies transcriptional regulation by bacterial metal-sensing repressors requires a detailed understanding of the structure and dynamics of all relevant ligand-bound and unligated states (3). We have focused much of our efforts on the Zn(II)/Co(II) sensor S. aureus CzrA as a paradigm system for understanding allosteric regulation of ArsR/SmtB family repressors by metal ions (10). Previous work with CzrA and the homologous Zn(II) sensor from Synechococcus, SmtB, has investigated in detail the free repressor dimer (denoted P) and the allosterically inhibited metal-bound form (P·Zn2) (8, 9, 20, 31). Here, we present the solution structure of the DNA operator-bound form of S. aureus CzrA and define key determinants of the protein-DNA interface.

The global quaternary structure of DNA-bound CzrA differs dramatically from the apo- and Zn2 CzrA states primarily due to a marked pendulum-like rotation and translation of one protomer relative to the other, ultimately leading to a significantly compacted structure. The binding of Zn(II) to the distal α5 sensing sites then drives open the structure of the homodimer. As a result, metal binding drives the DNA-bound CzrA off the operator while inhibiting subsequent binding of Zn(II)-bound CzrA to the DNA, with both scenarios leading to reduced operator-promoter occupancy and transcriptional derepression in vivo (Fig. S5) These quaternary structural transitions may be facilitated by the relatively weak dimer interface (31), which would allow the protomers to readily reorient themselves to maximize the complementarity of the protein-ligand [Zn(II) or DNA] interface in each conformational allosteric “end” state, P·D and P·Zn2.

Although intermolecular contacts between the αR helix and the DNA major groove were anticipated, the finding that the side chain of Val-42 in the α3 helix makes an energetically important contact with the DNA immediately suggests a structural rationale for how the DNA binding affinity of members of another subclass of ArsR/SmtB sensors, the α3N family (10), are allosterically inhibited by metal binding. α3N sensors employ two cysteine residues in an invariant CVC sequence to coordinate the metal, with the intervening Val corresponding precisely to Val-42 in CzrA (Fig. S6) (32–34). Thus, if the protein-DNA interfaces for all ArsR/SmtB sensors that recognize the identical or similar operator sequence (Fig. S6) are similar, metal binding here would be expected to drive the Val side chain off the DNA and thus significantly decrease the affinity of α3N sensors for their cognate operators. Such an observation would represent structural support for the idea that homologous proteins are capable of evolving distinct pathways of heterotropic allosteric control (13).

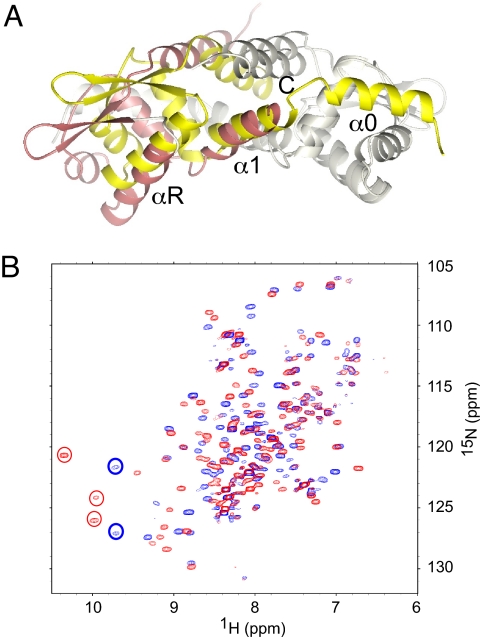

Knowledge of the structure of the CzrA-DNA operator complex also helps us to understand the origins of the differing magnitudes of the allosteric coupling free energy (ΔGc) of ArsR repressors that harbor distinct metal sensing sites (20, 34). A superposition of the structure of the apo-form of S. aureus pI258 CadC, an α3N metal sensor (35) with DNA-bound CzrA is striking in that the distance between the αR recognition helices within the dimer in apo CadC more similar to the DNA-bound form of CzrA than either apo-CzrA or apo-SmtB (Fig. 5A). CadC possesses a unique N-terminal α-helix (denoted α0 in Fig. 5A) which forms a significant part of the dimer interface in apo-CadC (35). If this α0-mediated interprotomer interaction also characterizes the DNA-bound conformation of CadC, we would hypothesize that metal binding simply “locks” the allosterically inhibited structure in place, that is, Cd(II) does not necessarily induce a large conformational change in the dimer. This hypothesis is consistent with the 1H-15N TROSY spectra of apo and cad operator DNA-bound C10G CadC from L. monocytogenes (32) (Fig. 5B). The amide cross peaks in the downfield region of the spectrum in unbound apo-CadC are indicative of a more closed or compacted conformation. When CadC binds to the DNA operator, the overall trajectory of the movement of these cross peaks is analogous to DNA-bound CzrA; however, the magnitude of the chemical shift perturbation of individual residues, as well as the fraction of residues that are strongly perturbed on binding DNA, appear much smaller (36). These spectra suggest that the quaternary structural change that occurs when CadC binds DNA may well be smaller than in the α5-site sensor CzrA, which in turn may translate into an experimentally observed smaller (less positive) ΔGc (2, 32).

Fig. 5.

Distinct mechanisms for allosteric control in α3N and α5 sensors. (A) A right protomer (shaded gray) superposition of the apo C11G S. aureus pI258 CadC dimer (35) and the DNA-bound form of apo-CzrA (this work). The subunits of apo-CadC are colored gray and yellow, while that for the DNA-bound CzrA are shaded gray and salmon. Note the N-terminal α0 helix in CadC is not present in CzrA; the N-terminal residue on this protomer is Gly-11, with the N-terminal 10 residues disordered. (B) Overlay of 1H-15N TROSY spectra acquired for apo C10G L. monocytogenes CadC (blue cross peaks) with the CadC-CadO complex (red cross peaks). See text for details.

Finally, the large structural change induced in DNA-bound CzrA when the α5 sensing sites are filled appears buttressed by a long-range dynamical communication that energetically couples the two ligand binding sites, albeit in largely opposite directions. Operator DNA-bound CzrA is characterized by detectably enhanced flexibility in the allosteric sites; in contrast, the opposite region of the molecule that makes direct protein-DNA contacts experiences detectably reduced mobility in the inhibited Zn2 form of CzrA (8). We propose that this reciprocal linkage of the opposite ligand binding site is mutually reinforcing and shifts this coupled equilibrium among P, P·D, P·Zn2 and P·Zn2·D in a coherent way. Additional dynamics and thermodynamic studies will be required to elucidate the degree to which disorder in the α5 helical region persists in the ternary Zn2-CzrA-DNA intermediate or contributes to the large ΔGc in this system. In any case, our findings are collectively consistent with the idea that residue-specific high frequency, low amplitude motions can be coincident with slower time scale, larger amplitude motions and may in fact represent a primary contributor for reciprocal allosteric effects in proteins (23).

Methods

Protein Production.

Recombinant CzrA was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells at 37°C and purified as described previously (31). For isotopic labeling, minimal media containing 15NH4Cl and [1H, 12C]-glucose in 70% D2O or [2H, 13C]-glucose in 99.9% D2O were used. For apo- and Zn(II)-loaded CzrA, U-15N labeled samples were produced without deuteration. For the production of (Ile/Leu/Val)-methyl-protonated and otherwise fully deuterated (ILV) CzrA, U-[2H,13C,15N] Ileδ1-[CH3] Leu, Val-[CH3/CH3], 85 mg α-[13C5, 3-2H1] ketoisovalerate, and 50 mg α-[13C4, 3,3-2H2] ketoisobutyrate (Isotech Inc.) were added to the culture 1 h before induction of protein expression with IPTG (at an A600 of ∼0.6) (36). A 28-bp self-complimentary oligonucleotide (IDT) containing the conserved 12–2-12 inverted repeat (italicized), 5′-TAACATATGAACATATGTTCATATGTTA −3′ was purified under denaturing conditions on Äkta 10 purifier using Source 15Q column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), the strands annealed and the duplex DNA further purified using the same column run under native conditions. The CzrA-DNA complex was reconstituted by diluting the DNA into a stock solution of CzrA. The final NMR samples were 1–2 mM (in CzrA dimer) after exchanging into 10 mM Mes-d13 containing 50 mM NaCl, 0.02% NaN3, and 7% D2O at pH 6.0.

NMR Experiments and Structure Calculations.

All NMR spectra were collected at 40°C on Varian Inova spectrometers operating at a 1H frequency of 600 MHz, 800 MHz, and 900 MHz. The spectrometers were equipped with a x–z- gradient triple resonance probes or z-gradient triple resonance cryoprobe. NMR Spectra were processed using NMRPipe/nmrDraw suite and analyzed using Sparky (37). Backbone and stereospecific methyl side chain resonance assignments were carried out as reported elsewhere (36). Backbone torsional angles (φ/ϕ) were derived from backbone 1H, 15N, and 13C chemical shifts using the program TALOS (38). Distance constraints for both intramolecular and intersubunit contacts were derived from 3D 13C/13C-separated methyl NOE and TROSY-version of the 3D 15N-separated NOE experiment. Backbone amide residual dipolar couplings, 1DNH, were obtained from the difference in the scalar coupling (1J) measured in 15 mg/ml phage Pf1 and isotropic media using a three-dimensional HNCO-based experiment (39). 1DNH couplings for the Zn(II)-loaded CzrA were obtained in the same manner except that the samples were aligned in stretched polyacrylamide gels (6%) and splittings measured using 2D IPAP-HSQC spectroscopy (40). NMR structural constraints for structure calculations were obtained from NOE-derived distances (NH-NH, Me-NH, Me-Me), backbone torsional angles from TALOS and one-bond residual dipolar couplings as long-range orientational constraints (Table S2). Other details of the structure calculations are described in SI Materials and Methods. Twenty lowest-energy structures were used to represent the final structure bundle of CzrO-bound apo-CzrA and analyzed using PROCHECK and WHATIF (Table S2). The solution structure of methyl-labeled Zn2 CzrA was calculated in exactly the same way (Table S1). Structure figures were generated using Molmol and Pymol (41). Resonance assignments for the DNA-bound, Zn(II)-bound and apo-CzrA have been deposited in the BioMagResBank (36) with the structure bundle and mean average solution structures of Zn2 CzrA and the CzrA-DNA complex deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 2KJC and 2KJB, respectively.

NMR Relaxation and H-D Exchange Experiments.

Backbone amide relaxation experiments (15N R1, R2 and 1H-15N steady-state heteronuclear NOE) were performed at 600 MHz using standard pulse sequences for the DNA-bound, Zn(II), and apo states of CzrA and analyzed as described in SI Materials and Methods. H-D exchange experiments were initiated by adding D2O to a dried sample of DNA-bound CzrA and recording 1H-15N TROSY spectrum every 45 min, with the exchange kinetics followed for several weeks. Amide proton exchange rates for apo- and Zn2 CzrA acquired under identical conditions were taken from Eicken et al. (8).

Fluorescence Anisotropy DNA-Binding Experiments.

Fluorescence anisotropy experiments were carried out on a PC1 spectrofluorometer as described previously (9) with binding data fit to a single binding site model (one dimer to DNA) coupled to a monomer-dimer equilibrium (Kdimer 1.7 × 105 M−1) (31) using Dynafit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We gratefully acknowledge Drs. Xiangming Kong, Texas A&M University, Geoff Armstrong, Rocky Mountain 900 MHz NMR Facility at the University of Colorado Medical School at Denver, and Joseph Ford, EMSL High Field NMR Laboratory at the Pacific National Laboratory (Proposal 19835) for help in acquiring NMR data. We also acknowledge Dr. Mario A. Pennella for assistance in the early stages of this project. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM042569) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (A-1295) to D.P.G., and by the Department of Chemistry, Indiana University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0905558106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Outten CE, O'Halloran TV. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science. 2001;292:2488–2492. doi: 10.1126/science.1060331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma Z, Jacobsen FE, Giedroc DP. Metal transporters and metal sensors: How coordination chemistry controls bacterial metal homeostasis. Chem Rev. 2009;109 doi: 10.1021/cr900077w. 10.1021/cr900077w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giedroc DP, Arunkumar AI. Metal sensor proteins: Nature's metalloregulated allosteric switches. Dalton Trans. 2007:3107–3120. doi: 10.1039/b706769k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu M, Fu D. Structure of the zinc transporter YiiP. Science. 2007;317:1746–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.1143748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherezov V, et al. Insights into the mode of action of a putative zinc transporter CzrB in Thermus thermophilus. Structure. 2008;16:1378–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh VK, et al. ZntR is an autoregulatory protein and negatively regulates the chromosomal zinc resistance operon znt of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:200–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuroda M, Hayashi H, Ohta T. Chromosome-determined zinc-responsible operon czr in Staphylococcus aureus strain 912. Microbiol Immunol. 1999;43:115–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eicken C, et al. A metal-ligand-mediated intersubunit allosteric switch in related SmtB/ArsR zinc sensor proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Arunkumar AI, Chen X, Giedroc DP. Structural insights into homo- and heterotropic allosteric coupling in the zinc sensor S. aureus CzrA from covalently fused dimers. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1937–1947. doi: 10.1021/ja0546828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busenlehner LS, Pennella MA, Giedroc DP. The SmtB/ArsR family of metalloregulatory transcriptional repressors: Structural insights into prokaryotic metal resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:131–143. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell DR, et al. Mycobacterial cells have dual nickel-cobalt sensors: Sequence relationships and metal sites of metal-responsive repressors are not congruent. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32298–32310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703451200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin J, et al. Convergent evolution of a new arsenic binding site in the ArsR/SmtB family of metalloregulators. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34346–34355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706565200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuriyan J, Eisenberg D. The origin of protein interactions and allostery in colocalization. Nature. 2007;450:983–990. doi: 10.1038/nature06524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morby AP, Turner JS, Huckle JW, Robinson NJ. SmtB is a metal-dependent repressor of the cyanobacterial metallothionein gene smtA: Identification of a Zn inhibited DNA-protein complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:921–925. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.4.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook WJ, Kar SR, Taylor KB, Hall LM. Crystal structure of the cyanobacterial metallothionein repressor SmtB: A model for metalloregulatory proteins. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:337–346. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner KH, Rosen MK, Kay LE. Global folds of highly deuterated, methyl-protonated proteins by multidimensional NMR. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1389–1401. doi: 10.1021/bi9624806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueller GA, et al. Global folds of proteins with low densities of NOEs using residual dipolar couplings: Application to the 370-residue maltodextrin-binding protein. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:197–212. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popovych N, Tzeng SR, Tonelli M, Ebright RH, Kalodimos CG. Structural basis for cAMP-mediated allosteric control of the catabolite activator protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6927–6932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900595106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y, et al. NMR solution structure of the integral membrane enzyme DsbB: Functional insights into DsbB-catalyzed disulfide bond formation. Mol Cell. 2008;31:896–908. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pennella MA, Arunkumar AI, Giedroc DP. Individual metal ligands play distinct functional roles in the zinc sensor Staphylococcus aureus CzrA. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:1124–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kern D, Zuiderweg ER. The role of dynamics in allosteric regulation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henzler-Wildman K, Kern D. Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature. 2007;450:964–972. doi: 10.1038/nature06522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henzler-Wildman KA, et al. A hierarchy of timescales in protein dynamics is linked to enzyme catalysis. Nature. 2007;450:913–916. doi: 10.1038/nature06407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popovych N, Sun S, Ebright RH, Kalodimos CG. Dynamically driven protein allostery. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freire E. The propagation of binding interactions to remote sites in proteins: Analysis of the binding of the monoclonal antibody D1.3 to lysozyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10118–10122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan H, Lee JC, Hilser VJ. Binding sites in Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase communicate by modulating the conformational ensemble. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12020–12025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220240297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe S, Kita A, Kobayashi K, Miki K. Crystal structure of the [2Fe-2S] oxidative-stress sensor SoxR bound to DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4121–4126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709188105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Godsey MH, Baranova NN, Neyfakh AA, Brennan RG. Crystal structure of MtaN, a global multidrug transporter gene activator. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47178–47184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heldwein EE, Brennan RG. Crystal structure of the transcription activator BmrR bound to DNA and a drug. Nature. 2001;409:378–382. doi: 10.1038/35053138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.VanZile ML, Chen X, Giedroc DP. Allosteric negative regulation of smt O/P binding of the zinc sensor, SmtB, by metal ions: A coupled equilibrium analysis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9776–9786. doi: 10.1021/bi020178t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pennella MA, Shokes JE, Cosper NJ, Scott RA, Giedroc DP. Structural elements of metal selectivity in metal sensor proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3713–3718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0636943100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busenlehner LS, Weng TC, Penner-Hahn JE, Giedroc DP. Elucidation of primary (α3N) and vestigial (α5) heavy metal-binding sites in Staphylococcus aureus pI258 CadC: Evolutionary implications for metal ion selectivity of ArsR/SmtB metal sensor proteins. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:685–701. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu T, Golden JW, Giedroc DP. A zinc(II)/lead(II)/cadmium(II)-inducible operon from the cyanobacterium Anabaena is regulated by AztR, an alpha3N ArsR/SmtB metalloregulator. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8673–8683. doi: 10.1021/bi050450+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu T, et al. A Cu(I)-sensing ArsR family metal sensor protein with a relaxed metal selectivity profile. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10564–10575. doi: 10.1021/bi801313y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye J, Kandegedara A, Martin P, Rosen BP. Crystal structure of the Staphylococcus aureus pI258 CadC Cd(II)/Pb(II)/Zn(II)-responsive repressor. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4214–4221. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.4214-4221.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arunkumar AI, Pennella MA, Kong X, Giedroc DP. Resonance assignments of the metal sensor protein CzrA in the apo-. Zn2- and DNA-bound (42 kD) states. Biomol NMR Assign. 2007;1:99–101. doi: 10.1007/s12104-007-9027-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delaglio F, et al. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Permi P, Rosevear PR, Annila A. A set of HNCO-based experiments for measurement of residual dipolar couplings in 15N, 13C, (2H)-labeled proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2000;17:43–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1008372624615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding K, Gronenborn AM. Sensitivity-enhanced 2D IPAP, TROSY-anti-TROSY, and E.COSY experiments: Alternatives for measuring dipolar 15N-1HN couplings. J Magn Reson. 2003;163:208–214. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. 29–32. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.