Abstract

Context:

Cheerleading injuries are on the rise and are a significant source of injury to females. No published studies have described the epidemiology of cheerleading injuries by type of cheerleading team and event.

Objective:

To describe the epidemiology of cheerleading injuries and to calculate injury rates by type of cheerleading team and event.

Design:

Prospective injury surveillance study.

Setting:

Participant exposure and injury data were collected from US cheerleading teams via the Cheerleading RIO (Reporting Information Online) online surveillance tool.

Patients or Other Participants:

Athletes from enrolled cheerleading teams who participated in official, organized cheerleading practices, pep rallies, athletic events, or cheerleading competitions.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

The numbers and rates of cheerleading injuries during a 1-year period (2006–2007) are reported by team type and event type.

Results:

A cohort of 9022 cheerleaders on 412 US cheerleading teams participated in the study. During the 1-year period, 567 cheerleading injuries were reported; 83% (467/565) occurred during practice, 52% (296/565) occurred while the cheerleader was attempting a stunt, and 24% (132/563) occurred while the cheerleader was basing or spotting 1 or more cheerleaders. Lower extremity injuries (30%, 168/565) and strains and sprains (53%, 302/565) were most common. Collegiate cheerleaders were more likely to sustain a concussion (P = .01, rate ratio [RR] = 2.98, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.34, 6.59), and All Star cheerleaders were more likely to sustain a fracture or dislocation (P = .01, RR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.16, 2.66) than were cheerleaders on other types of teams. Overall injury rates for practices, pep rallies, athletic events, and cheerleading competitions were 1.0, 0.6, 0.6, and 1.4 injuries per 1000 athlete-exposures, respectively.

Conclusions:

We are the first to report cheerleading injury rates based on actual exposure data by type of team and event. These injury rates are lower than those reported for other high school and collegiate sports; however, many cheerleading injuries are preventable.

Keywords: injury rates, injury epidemiology, trauma, accidents, athletes

Key Points

During the study period, most cheerleading injuries occurred during practice, with more than one-half of injuries sustained while the cheerleader was attempting a stunt and nearly one-quarter sustained while the cheerleader was basing or spotting another cheerleader.

The lower extremity was injured most often, and the most common injuries were sprains and strains.

Collegiate cheerleaders were more likely to sustain concussions and All Star cheerleaders more likely to sustain fractures or dislocations than were cheerleaders on other types of teams.

Cheerleading injuries are increasing and present a significant source of injury to females.1 According to a recent study,1 the number of cheerleading-related injuries sustained by children 5 to 18 years of age and treated in US hospital emergency departments has more than doubled, from an estimated 10 900 injuries in 1990 to an estimated 22 900 injuries in 2002. Thirty years ago, cheerleading routines consisted primarily of toe-touch jumps, the splits, and claps.2 Today, cheerleading routines incorporate gymnastic tumbling runs and partner stunts, consisting of human pyramids, lifts, catches, and tosses (eg, basket tosses).3 This change to more gymnastic-style cheerleading routines may be associated with the increasing number of cheerleading injuries.4–7 An increase in the number of cheerleading participants may also be a factor. Although the actual number of cheerleading participants is not known, American Sports Data Inc8 reported that the number of US cheerleading participants aged 6 years and older increased from 3 039 000 in 1990 to 3 579 000 in 2003.

Compared with other sports, cheerleading injuries have not received the same amount of concern with regard to tracking and reportability.9 Few epidemiologic studies of cheerleading injuries exist in the literature, and none of the existing studies describe the epidemiology of cheerleading injuries by type of cheerleading team (All Star, college, high school, middle school, elementary school, or recreation league) and type of cheerleading event (practice, pep rallies, athletic events, or cheerleading competitions). In response to the need for more information regarding cheerleading participation and injuries, our study objective was to describe the epidemiology of cheerleading injuries and to calculate cheerleading injury rates by type of cheerleading team and type of cheerleading event.

METHODS

Participants

All US cheerleading teams interested in participating in the study were permitted to enroll. Excluded from the study were impromptu teams formed by friends who got together to cheer for neighborhood sports teams. We used a convenience sample because there is no comprehensive or authoritative list of all cheerleading teams in the United States that can be accessed to aid in sampling the cheerleading population. Therefore, we were unable to use a statistically based procedure to obtain a nationally representative sample of cheerleading teams for the study.

Recruitment of Participants

Participants were recruited via e-mail, flyers, advertisements in cheerleading magazines and newsletters, a cheerleading radio show, cheerleading coaches' conferences, and the National Cheerleading Safety Summit meeting. Interested people were directed to a Web site that contained detailed information about the study: confidentiality assurance, study tasks to be completed by participants, compensation for participation, and a link to the enrollment form.

Enrollment

The enrollment form, created using SelectSurvey ASP Advanced software (version 8.0.2; ClassApps, Overland Park, KS), collected information about the designated team reporter, contact information, team type, team demographics, and information about the team coach (demographics and training). Upon completion of the enrollment form, the designated reporter was e-mailed a unique, randomly assigned, 6-digit reporter identification number; study timetable; contact information for the research team; link to an online training program for using Cheerleading RIO (Reporting Information Online; The Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH), an online, Internet-based surveillance tool; and a link for filing weekly online reports.

Online Training Program

The online training program consisted of a PowerPoint (version 2003; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) presentation designed to teach reporters how to use the online reporting tools for cheerleader exposures and injuries. Reporters were guided step by step through the reporting process using exposure and injury examples.

Our online exposure and injury report forms consisted of multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank questions. Because our report forms were simple to complete and, as described below, included instructions on the report forms, the online training program was optional.

Exposure and Injury Report Forms

Team reporters received a weekly e-mail containing a link to the reporting Web site to remind them to complete their exposure and injury reports. Reporters were asked to provide this information on a weekly basis.

The exposure report collected data on the number of athlete-exposures (AEs) for cheerleading practices, pep rallies, athletic events, and cheerleading competitions and the number of reportable injuries. An AE was defined as 1 cheerleader participating in 1 cheerleading event. An athletic event was defined as a sporting event during which cheerleading teams performed, such as a football or basketball game. To assist the reporter in calculating exposures, instructions and examples appeared directly on the exposure report form. We asked the reporters to calculate the AEs, because Cheerleading RIO was modeled after High School RIO (The Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital),10 and this procedure worked well for that surveillance tool.

A reportable injury was defined as an injury that met all 3 of the following criteria: (1) it occurred as a result of participation in an organized cheerleading practice, pep rally, athletic event, or cheerleading competition; (2) it prevented the injured cheerleader from participating in cheerleading for the remainder of that practice, pep rally, athletic event, or cheerleading competition or for a longer period of time; and (3) it required the injured cheerleader to seek medical attention. Medical attention was defined as meeting all 4 of the following criteria: (1) treatment at the scene or at a medical facility; (2) treatment administered at the time of the injury or at a later date (no more than 2 weeks after the injury event); (3) treatment required as a result of the injury; and (4) treatment administered by a certified athletic trainer, person trained in first aid, emergency medical technician, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or physician. For each injury reported on the exposure form, the reporter was required to fill out a separate injury report form. The criteria for reportable injuries appeared on the exposure report form. Information collected on the injury report form included body part injured, type of injury, circumstances surrounding the injury event, mechanism of injury, medical treatment received, final medical outcome, and the injured cheerleader's experience as a cheerleader. If the team reporter was not the coach or assistant coach, data for the exposure and injury reports were obtained from the coach and, if necessary, the injured cheerleader. Data were collected from June 5, 2006, through June 3, 2007 (52 complete weeks).

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS (version 15.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and Epi Info software (version 5.01b; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). Statistical analyses included calculation of rate ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), χ2 tests with the Yates correction, Fisher exact tests, t tests, and Mann-Whitney U tests. The level of significance for all statistical tests was α = .05.

Injury rates, defined as the number of injuries divided by the number of AEs, were calculated overall, by type of cheerleading team, and by type of cheerleading event. The 95% CI for each injury rate was calculated using the method described by Knowles et al.11 Numerous authors12–16 of sports-related injury studies in the literature defined a reportable injury as preventing the injured athlete from participating in the sport for 1 day or longer. To make our injury rates directly comparable with those injury rates, we adjusted the numerator in our injury rate calculations by subtracting the number of injuries for which the injured cheerleader was able to resume participation in cheerleading at the next practice or performance from the total number of injuries sustained.

Cheerleading does not have the equivalent of a “game,” as in other sports. Cheerleaders perform at pep rallies, athletic events, and cheerleading competitions, and the type of routine performed varies among and within these events. For example, cheerleaders performing at a basketball or football game may perform one type of routine on the sidelines while the game is being played but perform an entirely different, more gymnastic routine during halftime. To compare cheerleading injury rates with those for other sports, we grouped pep rallies, athletic events, and cheerleading competitions into one category, performances, as a proxy for “game” in other sports.

Data Quality Control

The data collected from Cheerleading RIO were audited on a weekly basis. This audit consisted of a check for missing data and typographic errors and a review to determine if the number of injuries reported on the weekly exposure report corresponded with the number of injury reports submitted for that week. If problems were discovered, the reporter was notified by e-mail and asked to make the required changes.

Three comprehensive audits were conducted during the 1-year study period: weeks 1 through 19, weeks 20 through 40, and weeks 41 through 52. These audits checked for errors in all data collected to date. The reporters were asked to supply all missing data and to fix all errors. If any data appeared to be inconsistent, the reporter was contacted by telephone, and necessary corrections were made.

Compensation for Participants

All team reporters who submitted exposure and injury data during the study received a copy of the “summary of findings” report. Team reporters who completed the full year of the study received an individual report of the data that they provided for their team, a package of incentives donated by numerous cheerleading organizations, and a certificate of participation in Cheerleading RIO 2006–2007. The incentive package included discounts for coach safety certification courses, cheerleading competition fees, an online cheerleading safety course, and cheerleading magazine subscriptions, among other items.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the institutional review board at our institution. We were granted a waiver of the informed consent/assent requirement under the IRB Latitude to Approve a Consent Procedure that Alters or Waives Some or All of the Elements of Consent (§46.116).

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 803 cheerleading teams were officially enrolled in the study; 243 of these teams (30%, 243/803) completed all 52 weeks of the study, 173 teams (22%, 173/803) withdrew from the study but submitted valid data before withdrawing, and 387 teams (48%, 387/803) never reported any data. Reasons for withdrawing from the study included dissolution of the cheerleading team, not having enough time to complete the reports, and personal or family illness. Data were not compromised by including the data from the 173 teams that withdrew from the study, because exposure and injury reports were collected on a weekly basis, and only data from completed weeks were included in the final database. Four of the teams were from Canada and the United Kingdom and were excluded from all data analyses. Data from the 412 US teams were used for analyses.

Team and Coach Demographics

The 412 US cheerleading teams (113 All Star, 37 college, 180 high school, 39 middle school, 3 elementary school, and 40 recreation league) represented 43 of the 50 US states (86%). All Star teams are generally under the direction of cheerleading or gymnastic gyms, are strictly competitive teams (do not support another athletic team), and have different rules than those for school and recreation league teams. Recreation league teams are under the direction of a city recreation department or a nonprofit youth association, such as Pop Warner or Police Athletic Leagues, and generally cheer for recreation or youth football and basketball teams. They can compete, but competition is not their main goal. Cheerleaders on all 6 types of teams are amateur athletes.

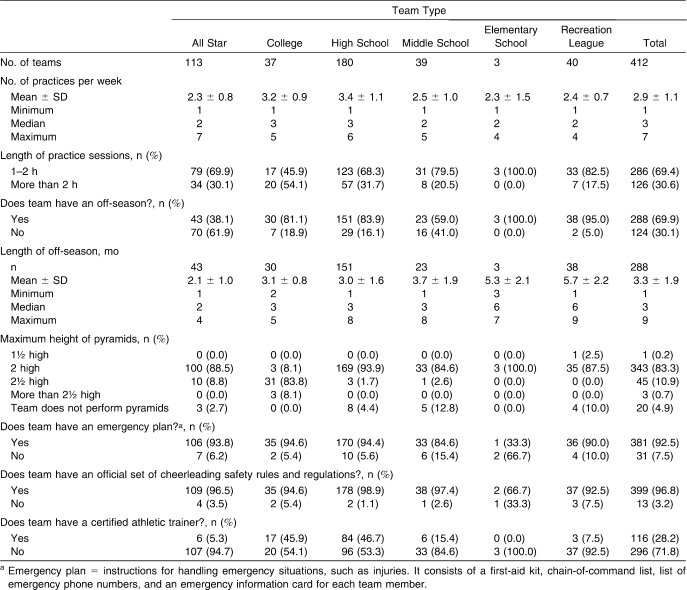

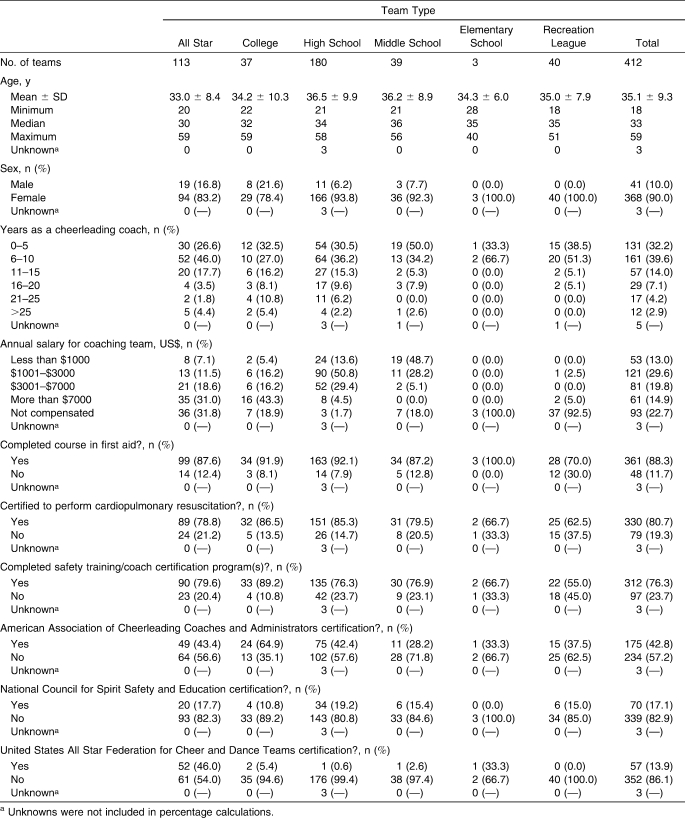

The 412 teams comprised 9022 cheerleaders, ranging in age from 3 to 29 years, and 96% (8694/9022) were female. All but 3 of the 412 teams (99%) had an official team coach who was not a member of the team. The 3 teams without an official coach were high school teams. Cheerleading teams are further described in Table 1, and the demographics and training of team coaches are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cheerleading Teams by Team Type

Table 2.

Cheerleading Coach Demographics and Credentials by Team Type

Injury Epidemiology

Description of Injured Cheerleaders

A total of 567 cheerleading injuries were reported during the 1-year study. Fifty cheerleaders were injured multiple times during the study period: 40 cheerleaders were injured on 2 occasions, and 10 cheerleaders were injured on 3 occasions. These 50 cheerleaders were members of 5 All Star, 5 collegiate, and 13 high school teams. Two of the injuries were sustained by elementary school cheerleaders (ankle strain or sprain and head pain) and are only included in injury rate and time lost calculations.

Injured cheerleaders ranged in age from 5 to 29 years (mean = 15.8 ± 3.1 years, median = 16 years), and 92% (519/565) were female. Male cheerleaders were older (mean = 20.2 ± 3.9 years) than female cheerleaders (mean = 15.4 ± 2.7 years) (P < .01). Forty-one percent (230/563) of the injured cheerleaders had participated in cheerleading for 5 years or longer. The others had participated in cheerleading for less than 7 months (6%, 36/563), 7 to 12 months (8%, 46/563), 2 years (14%, 77/563), 3 years (17%, 94/563), or 4 years (14%, 80/563), and the length of participation was unknown for 4 cheerleaders.

Injury Event Description

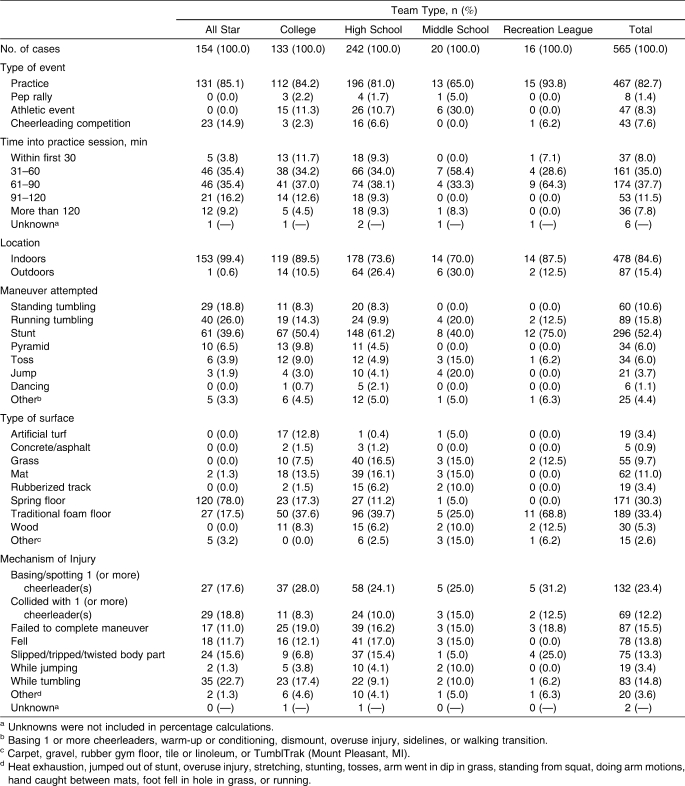

Eighty-three percent of injuries (467/565) were sustained during practice, and 38% (174/461) of these occurred 61 to 90 minutes into the practice session. Most of the injuries (85%, 478/565) occurred indoors. Injuries sustained outdoors involved extreme heat in 8% (7/87) of cases, extreme cold in 2% (2/87) of cases, and gusty winds in 1% of cases (1/87).

Most of the injuries occurred when the injured cheerleader was attempting a stunt (52%, 296/565) or tumbling (26%, 149/565). All Star cheerleaders were more likely to be injured while attempting a tumbling maneuver (P < .01, RR = 2.30, 95% CI = 1.77, 3.00) than were cheerleaders on other types of teams.

Cheerleaders were most often performing on a traditional foam floor (34%, 189/565) or spring floor (30%, 171/565) at the time of injury. All Star cheerleaders were more likely to be injured while performing on a spring floor (P < .01, RR = 6.28, 95% CI = 4.79, 8.23) and high school cheerleaders were more likely to be injured while performing on grass (P < .01, RR = 3.56, 95% CI = 2.01, 6.29) than were cheerleaders on other types of teams.

The most common mechanisms of injury were basing or spotting 1 (or more) cheerleader(s) (24%, 132/563), failure to complete a maneuver (15%, 87/563), tumbling (15%, 83/563), and falls (14%, 78/563). One cheerleader was injured when she was performing a back handspring on grass, and her arm went into a dip in the grass. Another cheerleader was injured when her foot went into a small hole in the grass while she was performing a jump. The mechanisms of injury were unknown in 2 cases. Injury events by team type are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of Injury Events by Team Type

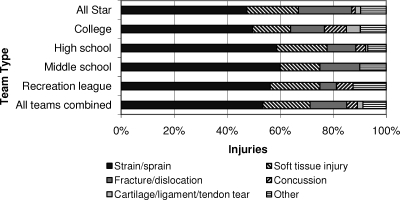

Injuries Sustained

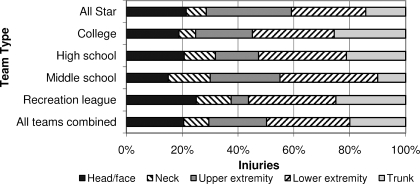

Lower extremity (30%, 168/565) and upper extremity (21%, 117/565) injuries were most common. For all team types combined, the top 5 body parts injured were the ankle (16%, 93/565), knee (9%, 51/565), neck (9%, 51/565), lower back (7%, 41/565), and head (7%, 38/565). All Star cheerleaders were more likely to injure the upper extremity (P < .01, RR = 1.79, 95% CI = 1.30, 2.46) than were cheerleaders on other types of teams. The body regions injured by team type are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cheerleading injuries in the United States, 2006–2007, according to Cheerleading RIO (Reporting Information Online). Body region injured by team type.

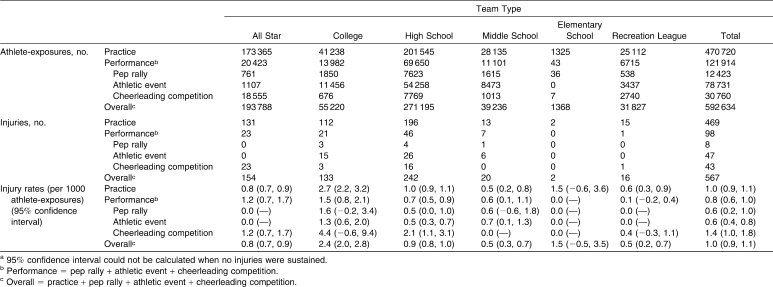

For all team types combined, the top 5 types of injury were strain or sprain (53%, 302/565); abrasion, contusion, or hematoma (13%, 76/565); fracture (10%, 55/565); laceration or puncture (4%, 25/565); and concussion or closed head injury (4%, 23/565). From this point forward in the article, concussions and closed head injuries will be referred to as concussions. One high school and 1 collegiate cheerleader sustained fractures of the cervical vertebrae, 1 high school cheerleader fractured a thoracic vertebra, and 1 All Star cheerleader fractured a lumbar vertebra. All Star cheerleaders were more likely to sustain a fracture or dislocation (P = .01, RR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.16, 2.66) and collegiate cheerleaders were more likely to sustain a concussion (P = .01, RR = 2.98, 95% CI = 1.34, 6.59) than were cheerleaders on other types of teams. The types of injury by team type are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Cheerleading injuries in the United States, 2006–2007, according to Cheerleading RIO (Reporting Information Online). Type of injury by team type. Soft tissue injury includes abrasion, contusion, hematoma, laceration, and puncture. Other includes avulsion, crush/pinch, dental injury, diaphragm spasm (“wind knocked out”), epistaxis, foreign body, friction burn, herniated disk, nerve damage, overuse injury, and spondylolysis.

For all team categories combined, the top 5 injuries sustained by cheerleaders were ankle strain or sprain (15%, 86/565), neck strain or sprain (7%, 37/565), lower back strain or sprain (5%, 31/565), knee strain or sprain (5%, 26/565), and wrist strain or sprain (4%, 24/565).

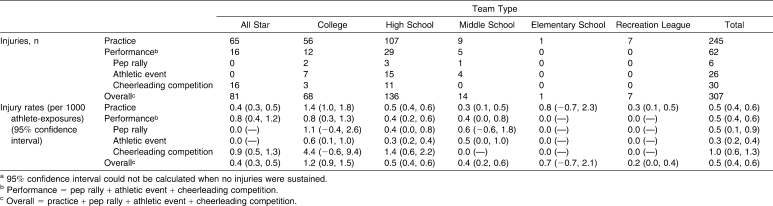

Injury Rates

During the 1-year period, AEs totaled 592 634. The overall injury rate for all types of events and teams combined was 1.0 injury per 1000 AEs (95% CI = 0.9, 1.1). Collegiate teams had the highest overall injury rate (2.4 injuries per 1000 AEs, 95% CI = 2.0, 2.8). Middle school and recreation league teams had the lowest injury rates (0.5 injuries per 1000 AEs, 95% CI = 0.3, 0.7). The number of exposures, number of injuries, and injury rates with 95% CIs by team type and event type are reported in Table 4. The adjusted number of injuries and adjusted injury rates with 95% CIs by team type and event type are shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Exposures, Injuries, and Injury Rates by Type of Team and Eventa

Table 5.

Adjusted Number of Injuries and Injury Rates by Type of Event and Team Typea

Injury rates for cheerleading competitions were higher than those for practices for All Star, collegiate, and high school teams (Table 4). The cheerleading competition injury rate for collegiate teams was greater than the rates for All Star and high school teams, although these differences were not statistically significant. Practice injury rates were higher than those for athletic events for both collegiate (P < .01, RR = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.21, 3.55) and high school (P < .01, RR = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.35, 3.05) teams. No statistically significant difference was noted between practice and pep rally injury rates for collegiate or high school teams. None of the All Star cheerleaders were injured during pep rallies or athletic events.

Relationship Between Coach Credentials and Injury Rates

Individual team injury rates ranged from 0.0 to 10.2 injuries per 1000 AEs and were skewed toward the lower values: 71% of the injury rates were less than or equal to 1.0, and 87% of the injury rates were less than or equal to 2.0. Injury rates were converted to a categorical variable for analyses: less than or equal to 2.0 injuries per 1000 AEs versus more than 2.0 injuries per 1000 AEs. Injury rates were not associated (P > .05) with the number of cheerleading safety training or certification programs completed by the coach, the coach's age, the number of years the coach had instructed cheerleaders, completion of the American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Administrators (AACCA) coach certification program, completion of the National Council for Spirit Safety and Education training program, or completion of the United States All Star Federation for Cheer and Dance Teams training program.

Final Medical Outcome

Medical Treatment

The most common location of medical treatment for injured cheerleaders was at the scene of the injury (32%, 178/561), followed by the doctor's office (25%, 143/561), hospital emergency department (22%, 124/561), certified athletic trainer's office (16%, 88/561), and urgent care center (5%, 27/561). One cheerleader was treated at a dentist's office. The location of medical treatment was unknown for 4 cheerleaders.

Hospitalization, Surgery, and Physical Therapy

Seven cheerleaders (3 All Star, 3 college, and 1 high school) were hospitalized (1.2%, 7/562). Hospitalization status was unknown for 3 cheerleaders. The injuries requiring hospitalization included fractures; cartilage, ligament, or tendon tears; a dislocation; and a herniated disk.

Eighteen cheerleaders (3%, 18/562) required surgery. The surgical status was unknown for 3 cheerleaders. Injuries requiring surgery included cartilage, ligament, or tendon tears; fractures; and dislocations. Fourteen percent of the cheerleaders (78/561, unknown = 4) required physical therapy.

Time Lost

Forty-six percent (257/563) of the injured cheerleaders resumed participation in cheerleading at the next practice or performance. Six cheerleaders (1%, 6/563) did not continue participating in cheerleading for nonmedical reasons, 1 cheerleader was medically prohibited from participating in cheerleading for her entire career, 16 cheerleaders (3%, 16/563) were medically prohibited from participating in cheerleading for the remainder of the season, and 2 cheerleaders were medically prohibited from participating in cheerleading indefinitely. The amount of time lost was unknown for 4 cheerleaders. The remaining cheerleaders (50%, 281/563) were medically prohibited from participating in cheerleading for a specified number of days. The total number of days of cheerleading participation lost by these 281 cheerleaders was 4618 (mean = 16.4 ± 21.9 days, minimum = 1 day, median = 10 days, maximum = 240 days, and mode = 14 days). The number of days lost by team type was as follows: All Star = 1369, college = 1103, high school = 1832, middle school = 257, elementary school = 7, and recreation league = 50.

DISCUSSION

We are the first authors to prospectively collect data on cheerleading exposures and injuries for US cheerleading teams, grouped by practices, pep rallies, athletic events, and cheerleading competitions, as well as by 6 team categories. In the media, cheerleading has been described as “by far the most perilous sport for female athletes in high school and college”17; however, our injury rates do not support that claim. Our overall cheerleading injury rates per 1000 AEs, including adjusted injury rates, for all 6 categories of teams were lower than those reported for other sports (per 1000 AEs): collegiate women's gymnastics12 (practice = 6.1, game = 15.2), collegiate women's basketball13 (practice = 4.0, game = 7.7); collegiate women's soccer13 (practice = 5.2, game = 16.4), collegiate men's wrestling14 (7.2), collegiate men's football15 (8.6), and high school boys' football15 (4.4). Our adjusted overall injury rate for high school cheerleading teams (0.5 injuries per 1000 AEs, 95% CI = 0.4, 0.6) was lower than that reported by Schulz et al16 for North Carolina high school competitive cheerleaders from 1996 to 1999 (0.9 injuries per 1000 AEs, 95% CI = 0.6, 1.2). This difference may be attributable to the fact that the cheerleading team in the Schulz et al16 study was strictly competitive, and the cheerleaders may have been performing more advanced maneuvers than the high school cheerleaders in our study (for whom competition was a minor focus and not as important as cheering at pep rallies and athletic events), thus exposing them to a greater risk for injury.

We found the highest overall injury rate in collegiate cheerleaders (2.4 injuries per 1000 AEs, 95% CI = 2.0, 2.8). This result agrees with those results reported14,15 for other sports, in which collegiate teams had higher injury rates than high school teams. Collegiate cheerleaders may be expected to be more experienced than high school cheerleaders. Therefore, collegiate cheerleaders may be expected to incorporate more difficult stunts into their routines and, as a result, may be more likely to be injured while performing the routines.

Similar to the findings of Knowles et al,18 we found that the experience, qualifications, and training of cheerleading coaches had no effect on cheerleading injury rates. These results disagree with those of Schulz et al,16 who found lower injury rates among cheerleaders supervised by more experienced, trained, and qualified coaches. This discrepancy needs to be explored further in future studies.

The following results from our study agree with those reported in other cheerleading injury studies: (1) lower extremity injuries were most common, followed by upper extremity injuries1; (2) the ankle was injured most often3,9,16; (3) strains and sprains were the most common types of injury1,3,16; and (4) most cheerleading injuries occur during gymnastic maneuvers, partner stunts, and pyramids.3,16 We noted that the most common mechanism of injury was basing or spotting 1 (or more) cheerleader(s). However, Schulz et al16 found that falls from heights and contact with another cheerleader resulted in the greatest percentage of injuries. Although their results were for a competitive high school team, the most common mechanism of injury for the strictly competitive All Star teams in our study was tumbling. The second most common mechanism of injury for the All Star teams was collision with other cheerleader(s), which does agree with the results reported by Schulz et al.16 This discrepancy may be the result of different types of maneuvers being performed by different cheerleading teams, different teaching methods by different cheerleading coaches, or other factors. Additional studies should be conducted on a larger number of cheerleading teams to further explore this issue.

Although concussions represented only 4% of the injuries in the present study and in the study by Shields and Smith1 and 6% in the study by Schulz et al,16 they can be a serious injury, exposing the cheerleader to the potential for repetitive traumatic brain injury (formally known as second-impact syndrome). Repetitive traumatic brain injury occurs after an initial head injury, usually a concussion, when an individual sustains a second head injury before symptoms associated with the first have fully cleared. The second blow may be minor and results in brain swelling. Although repetitive traumatic brain injury is most common in contact and collision sports in which head trauma is likely, such as football, ice hockey, and boxing,19–21 and is usually associated with athletes 19 years of age and younger,20,22 it may also be sustained when cheerleaders collide with other cheerleaders. Cheerleaders, their parents, cheerleading coaches, athletic trainers, and health care providers should be aware of the signs and symptoms of concussion and the potential for repetitive traumatic brain injury.

Strains and sprains were the most common injuries sustained by cheerleaders on all types of teams in our study. Conditioning and strength training can help prevent strain and sprain injuries.23–27 We suggest that cheerleaders focus on increasing the frequency of their conditioning and strength training in an effort to decrease the number of strain and sprain injuries. Increasing the number of cheerleading teams that have a certified athletic trainer may also help to promote prevention and appropriate identification and treatment of those and other injuries.

One major concern identified by our study is that some of the injuries were sustained while the cheerleaders were practicing or performing on concrete and asphalt. Both of these extremely hard surfaces fail to absorb impacts. The 2007–2008 AACCA College Cheerleading Safety Rules28 specifically stated that “technical skills should not be performed on concrete, asphalt, wet or uneven surfaces, or surfaces with obstructions.” This guideline should apply not only to collegiate cheerleaders but to all cheerleaders on all types of teams. Concrete, asphalt, grass, and dirt are not considered appropriate protective surfacing materials for use under playground equipment,29 and fall heights from playground equipment are generally less than the 15 ft (4.57 m) or more that cheerleaders may fall during tosses or from the tops of pyramids.

Although conclusive evidence that coach experience, qualifications, and training decrease the number of cheerleading injuries does not currently exist, we feel that all coaches should be required to complete a cheerleading safety training or coach certification program, such as those offered by the AACCA and the National Council for Spirit Safety and Education, before being allowed to coach a cheerleading team. In addition, all cheerleading teams should adopt and enforce a set of cheerleading safety rules and regulations appropriate for their type of cheerleading team. Examples of such rules are the AACCA High School Safety Rules30 and the AACCA College Safety Rules.28

This study has several limitations. First, only 52% of the teams that enrolled in the study submitted data. The other 48% never logged onto the reporting Web site to submit data. However, no statistically significant differences in team demographics, coach demographics, or coach training existed between the teams that submitted data and those that did not, based on the enrollment data collected. Second, teams participating in this study were not selected based on a probability sample because of the lack of a comprehensive or authoritative list (sampling frame) of all cheerleading teams in the United States; therefore, the study results may not be generalizable to all cheerleading teams in the United States. Third, completion of the online training program was optional. In addition, because cheerleading coaches in the United States are not required to maintain injury logs or submit injury reports to state agencies, a source for cross-checking the accuracy of the injury data reported to Cheerleading RIO was not available. The use of certified athletic trainers as study reporters may have increased the accuracy of the injury data reported, but requiring reporters to be certified athletic trainers would have severely limited the number of cheerleading teams eligible to participate in the study, because only 28% of the cheerleading teams in the present study (mostly high school and collegiate teams) had a certified athletic trainer.

Despite its limitations, this study is the first to report cheerleading injury rates based on actual exposure data by type of team and event. Cheerleading injury rates, as noted in this study, were lower than those reported for other high school and collegiate sports. Overall injury rates were highest for cheerleading competitions, followed by practices, pep rallies, and athletic events. Many cheerleading injuries are preventable. Development of a national database to collect cheerleading exposure and injury data, via mandatory reporting, would aid in the identification of risk factors for cheerleading injuries and guide the development of injury prevention strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this study was provided by The Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital. We thank Jason Morrison for designing the Cheerleading RIO Web site, programming the exposure and injury report questionnaires, and maintaining the Web site and database throughout the study year. Terri Bleeker used her outstanding artistic talent to design the certificates presented to study participants. Debbie Bracewell, Lisa Thompson, and Steve Wedge helped to categorize the cheerleading maneuvers. Gwen Holtsclaw provided the cheerleading photographs used on the Web site and on the certificates and was invaluable in offering advice, answering questions, and helping with issues that arose during the study year. We thank the cheerleading industry for assistance in identifying and contacting potential study participants and for donating incentives for the participants who completed the full study year.

Footnotes

Brenda J. Shields, MS, contributed to conception and design; acquisition and analysis and interpretation of the data; and drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the article. Gary A. Smith, MD, DrPH, contributed to conception and design and critical revision and final approval of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shields B. J., Smith G. A. Cheerleading-related injuries to children 5 to 18 years of age: United States, 1990–2002. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):122–129. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giannone L., Williamson T. L. A philosophy of safety awareness. In: George G. S., editor. American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Administrators Cheerleading Safety Manual. Memphis, TN: UCA Publications Department; 2006. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchinson M. R. Cheerleading injuries: patterns, prevention, case reports. Physician Sportsmed. 1997;25(9):83–96. doi: 10.3810/psm.1997.09.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boden B. P., Tacchetti R., Mueller F. O. Catastrophic cheerleading injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(6):881–888. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310062501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luckstead E. F., Patel D. R. Catastrophic pediatric sports injuries. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49(3):581–591. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(02)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luckstead E. F., Satran A. L., Patel D. R. Sport injury profiles, training and rehabilitation issues in American sports. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49(4):753–767. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(02)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller F. O., Cantu R. C. National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research: twenty-fifth annual report, fall 1982–spring 2007. http://www.unc.edu/depts/nccsi/AllSport.htm. Accessed September 5, 2008.

- 8.American Sports Data Inc. The Superstudy of Sports Participation: Volume II. Recreational Sports 2003. Hartsdale, NY: American Sports Data Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson B. H., Hubbard M., Redus B., et al. An assessment of high school cheerleading: injury distribution, frequency, and associated factors. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(5):261–265. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2004.34.5.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sports-related injuries among high school athletes: United States, 2005–06 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(38):1037–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowles S. B., Marshall S. W., Guskiewicz K. M. Issues in estimating risks and rates in sports injury research. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):207–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall S. W., Covassin T., Dick R., Nassar L. G., Agel J. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's gymnastics injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2003–2004. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):234–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hootman J. M., Dick R., Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):311–319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yard E. E., Collins C. L., Dick R. W., Comstock R. D. An epidemiologic comparison of high school and college wrestling injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(1):57–64. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shankar P. R., Fields S. K., Collins C. L., Dick R. W., Comstock R. D. Epidemiology of high school and collegiate football injuries in the United States, 2005–2006. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(8):1295–1303. doi: 10.1177/0363546507299745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulz M. R., Marshall S. W., Yang J., Mueller F. O., Weaver N. L., Bowling J. M. A prospective cohort study of injury incidence and risk factors in North Carolina high school competitive cheerleaders. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(2):396–405. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kingsbury K. Cheerleading's risky lack of rules. Yahoo News Web site. http://news.yahoo.com/s/time/20080819/us_time/cheerleadingsriskylackofrules. Accessed September 4, 2008.

- 18.Knowles S. B., Marshall S. W., Bowling J. M., et al. A prospective study of injury incidence among North Carolina high school athletes. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(12):1209–1221. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proctor M. R., Cantu R. C. Head and neck injuries in young athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19(4):693–715. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantu R. C. Recurrent athletic head injury: risks and when to retire. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22(3):593–603. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(02)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantu R. C. Second-impact syndrome. Clin Sports Med. 1998;17(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buzzini S. R. R., Guskiewicz K. M. Sport-related concussion in the young athlete. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(4):376–382. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000236385.26284.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adirim T. A., Cheng T. L. Overview of injuries in the young athlete. Sports Med. 2003;33(1):75–81. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrick J. G., Requa R. K. Epidemiology of women's gymnastics injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8(4):261–264. doi: 10.1177/036354658000800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence J. P., Greene H. S., Grauer J. N. Back pain in athletes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(13):726–735. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200612000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rechel J. A., Yard E. E., Comstock R. D. An epidemiologic comparison of high school sports injuries sustained in practice and competition. J Athl Train. 2008;43(2):197–204. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thacker S. B., Gilchrist J., Stroup D. F., Kimsey C. D., Jr The impact of stretching on sports injury risk: a systematic review of the literature. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(3):371–378. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000117134.83018.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Administrators. 2007–2008 AACCA college cheerleading safety rules. http://www.aacca.org/collegesafety.asp. Accessed June 16, 2008.

- 29.U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Public Playground Safety Handbook. Section 2.4.2, Selecting a surfacing material. http://www.cpsc.gov/CPSCPUB/PUBS/325.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2008.

- 30.American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Administrators. 2007–08 high school safety rules. http://www.aacca.org/hssafety.asp. Accessed June 13, 2008.