Abstract

Context:

Over the past several decades, cheerleaders have been performing fewer basic maneuvers and more gymnastic tumbling runs and stunts. As the difficulty of these maneuvers has increased, cheerleading injuries have also increased.

Objective:

To describe the epidemiology of cheerleading fall-related injuries by type of cheerleading team and event.

Design:

Prospective injury surveillance study.

Setting:

Participant exposure and injury data were collected from US cheerleading teams via the Cheerleading RIO (Reporting Information Online) surveillance tool.

Patients or Other Participants:

Athletes from 412 enrolled cheerleading teams who participated in official, organized cheerleading practices, pep rallies, athletic events, or cheerleading competitions.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

The numbers and rates of cheerleading fall-related injuries during a 1-year period (2006–2007) are reported.

Results:

A total of 79 fall-related injuries were reported during the 1-year period. Most occurred during practice (85%, 67/79) and were sustained by high school cheerleaders (51%, 40/79). A stunt or pyramid was being attempted in 89% (70/79) of cases. Fall heights ranged from 1 to 11 ft (0.30–3.35 m) (mean = 4.7 ± 2.0 ft [1.43 ± 0.61 m]). Strains and sprains were the most common injuries (54%, 43/79), and 6% (5/79) of the injuries were concussions or closed head injuries. Of the 15 most serious injuries (concussions or closed head injuries, dislocations, fractures, and anterior cruciate ligament tears), 87% (13/15) were sustained while the cheerleader was performing on artificial turf, grass, a traditional foam floor, or a wood floor. The fall height ranged from 4 to 11 ft (1.22–1.52 m) for 87% of these cases (13/15).

Conclusions:

Cheerleading-related falls may result in severe injuries and even death, although we report no deaths in the present study. The risk for serious injury increases as fall height increases or as the impact-absorbing capacity of the surfacing material decreases (or both).

Keywords: injury surveillance, athletic injuries, elite athletes, collegiate athletes, high school athletes, youth athletes

Key Points

Cheerleading-related falls may result in catastrophic injuries and even death.

Most of the serious injuries in the present study were sustained on artificial turf, grass, traditional foam floors, or wood floors.

The risk for serious injury increases as fall height increases or the impact-absorbing capacity of the surfacing material decreases (or both).

In 2006, national attention was focused on a collegiate cheerleader who fell 15 ft (4.57 m) from a pyramid, landing on her head on a wood gym floor during a time-out performance for a basketball game.1 She sustained a chipped neck vertebra and a concussion.1 As cheerleading has increased in popularity, so has the difficulty of the routines performed by cheerleaders.2 Over the past 30+ years, cheerleaders have evolved from performing very basic maneuvers, such as toe-touch jumps, the splits, and claps,3 to performing gymnastic tumbling runs and stunts consisting of human pyramids, lifts, catches, and tosses (basket tosses).4 Associated with the increased difficulty of the cheerleading maneuvers being performed is an increased number of cheerleading-related injuries. Shields and Smith5 reported that cheerleading-related injuries to children 5 to 18 years of age in the United States increased 110%, from 10 900 in 1990 to 22 900 in 2002.

Although several studies5–7 of cheerleading-related injuries have been published in recent years, none have specifically described injury events in terms of the mechanism of injury, type of surface on which the cheerleader was performing, type of maneuver being attempted, or the interaction of these variables. Schulz et al6 reported that the most common mechanisms of injury for competitive North Carolina high school cheerleaders were falls from heights (25%) and contact with another cheerleader (25%). Mueller and Cantu8 described 59 catastrophic cheerleading injury cases. In 31 cases, the word fall was included in the description of the injury event, and a fall was implied as the mechanism of injury for 13 other cases. Only 3 of the 59 cases specifically described the surface on which the cheerleader landed (ie, damp grass, wet artificial turf, or hard rubberized basketball court). Boden et al9 described 29 catastrophic cheerleading injuries and included the type of maneuver and surface on which the cheerleader was performing, but they did not consistently associate the mechanism of injury, type of surface, and maneuver in each description. In some cases, the description of the surface was vague (eg, “hard gym surface” or “hard ground”).

The goal of our study was to describe the epidemiology of cheerleading fall-related injuries sustained by US cheerleaders during a 1-year period (2006–2007). We describe these injuries by type of cheerleading team and event.

METHODS

Cheerleading RIO (Reporting Information Online; The Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH), an Internet-based injury surveillance system for collecting cheerleading exposure and injury data, was described in detail previously.2 Briefly, all cheerleading teams with a designated reporter were eligible to participate. Using Cheerleading RIO, data were collected for a 1-year period: June 5, 2006, through June 3, 2007 (52 weeks). A reportable injury was defined as an injury that met all 3 of the following criteria: (1) it occurred as a result of participation in an organized cheerleading practice, pep rally, athletic event, or cheerleading competition; (2) it prevented the injured cheerleader from participating in cheerleading for the remainder of that practice, pep rally, athletic event, or cheerleading competition or for a longer period of time; and (3) it required the injured cheerleader to seek medical attention. Medical attention was defined as treatment meeting all 4 of the following criteria: (1) provided at the scene or at a medical facility, (2) administered at the time of the injury or at a later date (no more than 2 weeks after the injury event), (3) required as a result of the injury, and (4) administered by a certified athletic trainer, person trained in first aid, emergency medical technician, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or physician. Athletic events were defined as sporting events during which cheerleading teams performed, such as football and basketball games.

For the present study, a subset of the data collected from Cheerleading RIO, consisting of fall-related injuries sustained by cheerleaders on US cheerleading teams, was analyzed. One fall-related injury case was deleted because it occurred while the cheerleader was running on bleachers during practice and fell onto concrete. We defined the categories of tumbling as handsprings, layouts, tucks or flips, and miscellaneous tumbling. Stunts were categorized as basket tosses, cradles, elevators, extensions, pyramids, single-based stunts, single-leg stunts, transitions, stunt-cradle combinations, and miscellaneous stunts. Definitions of these maneuvers are available at https://secure.usasf.net/Documents/Rules/Cheer%2008-09/USASFGlossary0809.pdf.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 15.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Statistical analyses included calculation of rate ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and Fisher exact tests. The level of significance for all statistical tests was α = .05. Descriptive statistics included all US fall-related injuries, including multiple injury events for the same cheerleader, during the 1-year study.

Injury rates, defined as the number of injuries divided by the number of athlete-exposures, were calculated overall and by type of cheerleading team. The 95% CI for each injury rate was calculated using the method described by Knowles et al.10 The exposure data were presented in a previous manuscript.2 An athlete-exposure (AE) was defined as 1 cheerleader participating in 1 cheerleading event.

Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the authors' institution. We were granted a waiver of the informed consent/assent requirement under the Institutional Review Board Latitude to Approve a Consent Procedure that Alters or Waives Some or All of the Elements of Consent (§46.116).2

RESULTS

Sample Description

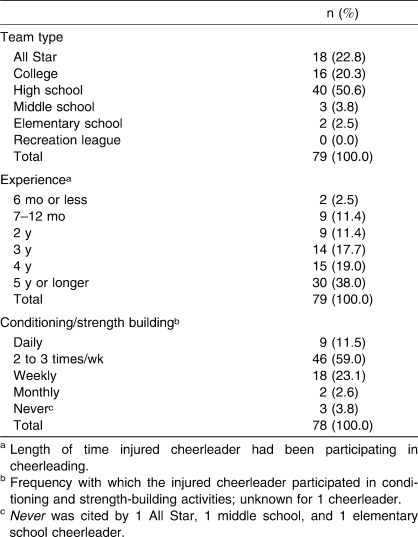

Fall-related injuries accounted for 14% (79/567) of the injuries reported to Cheerleading RIO during the study. These injuries were sustained by 77 cheerleaders on 56 of the 412 (14%) teams that participated in the study. Injured cheerleaders ranged in age from 6 to 27 years (mean = 15.5 ± 3.1 years, median = 16 years), and 96% (76/79) were female. Two cheerleaders sustained 2 fall-related injuries each. Characteristics of the injured cheerleaders are presented in Table 1. Team categories were All Star, college, high school, middle school, and elementary school. All Star teams included participants of all ages and were generally under the direction of cheerleading or gymnastic gyms, were strictly competitive teams (did not support another athletic team), and had rules that were different than those for school teams.2

Table 1.

Characteristics of Injured Cheerleaders

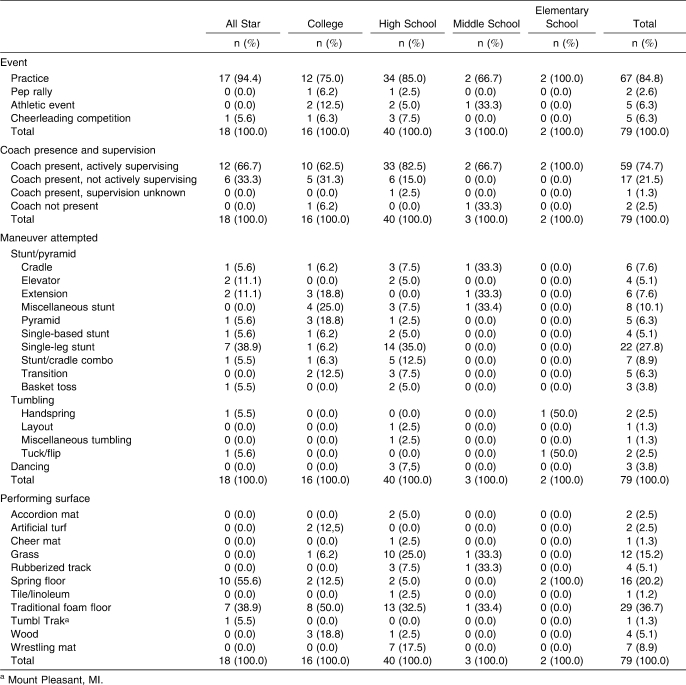

Description of Injury Event

Seventy-eight percent (62/79) of the falls occurred indoors, and none of those that occurred outdoors involved extreme heat, extreme cold, or gusty winds. Most of the injury events occurred during practices (85%, 67/79), and the coach was present and actively supervising the execution of the maneuver in 75% (59/79) of the injury events (Table 2). Spotters were actively spotting the execution of the maneuver in 62% (49/79) of the injury events. The number of spotters ranged from 1 to 6 (mean = 2.3 ± 1.2, median = 2.0). The presence of spotters, who were actively spotting the execution of the maneuver, was not significantly associated with a decrease in the number of serious injuries sustained (concussions or closed head injuries [CHIs]; fractures; dislocations; and cartilage, ligament, or tendon tears).

Table 2.

Description of Injury Event by Team Type

Most of the falls occurred when the injured cheerleader was attempting a stunt or pyramid (89%, 70/79), and single-leg stunts accounted for 28% (22/79) of the injuries (Table 2). At the time of injury, 38% (29/79) of the cheerleaders were performing on a traditional foam floor (Table 2). During one of the injury events, the injured cheerleader was performing on a TumblTrak (Mount Pleasant, MI) (photo at http://www.tiffinmats.com/Products/tumble_trak.html) and fell onto concrete. Fall heights ranged from 1 to 11 ft (0.30–3.35 m)(mean = 4.7 ± 2.0 ft [1.43 ± 0.61 m], median = 5.0 ft [1.52 m]). All fall heights were estimated based on athlete recollection and were not measured distances. High school cheerleaders were more likely to fall onto grass (P = .02, RR = 4.9, 95% CI = 1.1, 20.8) and All Star cheerleaders were more likely to fall onto a spring floor (P < .01, RR = 5.6, 95% CI = 2.4, 13.4) than were cheerleaders on other types of teams.

Forty-three percent (34/80) of the falls involved more than 1 cheerleader. The specific mechanisms of injury for these falls were as follows: the injured cheerleader landed on another cheerleader (47%, 16/34); another cheerleader landed on the injured cheerleader (18%, 6/34); another cheerleader served as the base for the injured cheerleader (12%, 4/34); another cheerleader landed on the injured cheerleader, pinning the injured cheerleader underneath (6%, 2/34); the injured cheerleader was being caught by another cheerleader(s) (6%, 2/34); the injured cheerleader provided the base for another cheerleader (3%, 1/34); another cheerleader landed on the injured cheerleader at the same time that the injured cheerleader landed on a third cheerleader (3%, 1/34); and the mechanism of injury was unknown for the remaining 2 cases (6%, 2/34).

Injuries Sustained

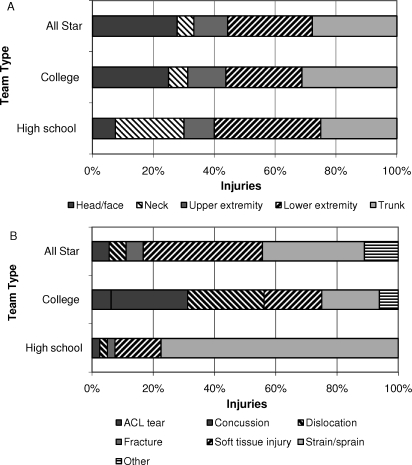

Strains and sprains accounted for 54% (43/79) of the injuries, and the lower extremity was injured most often (30%, 24/79). Ankle (18%, 14/79) and neck (13%, 10/79) strains and sprains were the 2 most common injuries sustained. Collegiate cheerleaders were more likely to sustain a concussion or CHI (P < .01, RR = 15.8, 95% CI = 1.9, 131.4) or a dislocation (P = 0.01, RR = 7.9, 95% CI = 1.6, 39.2) than were cheerleaders on other types of teams. The Figure presents the body region injured and type of injury, by team type, for All Star, collegiate, and high school cheerleaders. The injuries sustained by the 3 middle school cheerleaders were an abrasion, contusion, or hematoma of the sacrum/coccyx region; a wrist strain or sprain; and a neck strain or sprain. One of the 2 elementary school cheerleaders sustained a blow to the head, with no visible injury, only pain. The other sustained an ankle strain or sprain.

Figure.

Cheerleading fall-related injuries in the United States, 2006–2007, according to Cheerleading RIO (Reporting Information Online). A, Body part injured, and B, type of injury by team type. All Star: n = 18; college: n = 16; high school: n = 40. Other includes diaphragm spasm (“having the wind knocked out”), spondylolysis, and pain. Abbreviation: ACL, anterior cruciate ligament. Note: Middle and elementary school teams were not included in this figure because of small sample sizes.

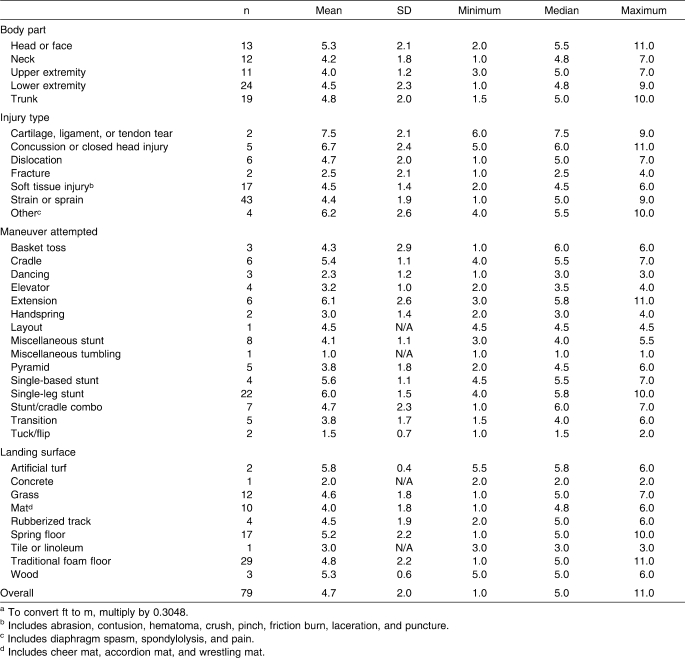

Summary statistics for fall height by body part, injury type, maneuver attempted, surface landed on, and all fall-related injuries combined are presented in Table 3. Average fall heights ranged from 4.0 ft (1.22 m) for upper extremity injuries to 5.3 ft (1.52 m) for head and face injuries. Fractures were sustained at an average fall height of 2.5 ft (0.76 m), whereas cartilage, ligament, or tendon tears were sustained at 7.5 ft (2.29 m) and concussions or CHIs at 6.7 ft (2.04 m). Cheerleaders injured while attempting extensions and single-leg stunts fell from an average of 6.0 ft (1.83 m); tumblers were injured during falls from as low as 1 ft (0.30 m). Injuries sustained while practicing or performing on concrete occurred at an average fall height of 2.0 ft (0.61 m); the highest average fall height was documented for artificial turf (5.8 ft [1.77 m]).

Table 3.

Fall Height (ft) by Body Part, Injury Type, Maneuver Attempted, Surface Landed On, and Overalla

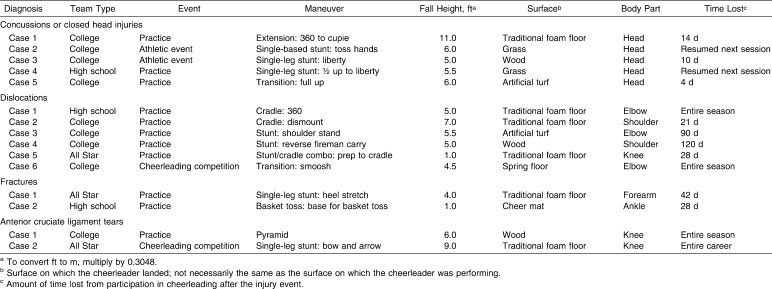

The injury events associated with concussions or CHIs, dislocations, fractures, and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are described in Table 4. Four of 5 concussions or CHIs were sustained by collegiate cheerleaders attempting single-based and single-leg stunts. Five of 6 dislocations were sustained during practice sessions, and 4 of the 6 were sustained by collegiate cheerleaders. All dislocations were sustained while attempting stunts, and half were sustained on a traditional foam floor. Two fractures were sustained, both during practice and both while attempting a stunt. Two ACL tears were sustained: 1 while practicing on a wood floor and 1 while competing on a traditional foam floor.

Table 4.

Descriptions of Injury Events Associated With Concussions or Closed Head Injuries, Dislocations, Fractures, and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears

Only 6% (5/79) of the fall-related injuries were reinjuries. Of these 5 reinjuries, the previous injury was related to cheerleading in 4 cases (80%, 4/5). The 5 reinjuries consisted of 2 ankle strains or sprains, 1 elbow dislocation, 1 shoulder dislocation, and 1 preexisting condition (spondylolysis).

Injury Rates

The injury rates per 100 000 AEs for falls, by team type, were as follows: All Star, 9.3 (95% CI = 5.0, 13.6); college, 29.0 (95% CI = 14.9, 43.1); high school, 14.7 (95% CI = 10.2, 19.2); middle school, 7.6 (95% CI = 0.0, 16.2); and elementary school, 146.2 (95% CI = 0.0, 348.9). The overall injury rate per 100 000 AEs was 13.3 (95% CI = 10.4, 16.2).

Medical Treatment, Hospital Admission, Surgery, and Physical Therapy

Thirty-four percent (27/79) of the injured cheerleaders were treated at the scene, 28% (22/79) at a hospital emergency department, 25% (20/79) at a doctor's office, 8% (6/79) at the athletic trainer's office, and 5% (4/9) at an urgent care center. Two of the injured cheerleaders (2%, 2/79) were admitted to the hospital. One of these cheerleaders was admitted for a torn ACL and the other for a dislocated shoulder. Three of the injured cheerleaders (4%, 3/79) required surgery. Two of the 3 had torn ACLs, and the third had a dislocated elbow. Physical therapy was required by 13 (16%, 13/79) of the injured cheerleaders.

Time Lost

Thirty-four (43%, 34/79) of the injured cheerleaders were able to resume participation in cheerleading at the next practice or performance. The others were medically prohibited from participating in cheerleading for the rest of her career (1%, 1/79), the rest of the season (5%, 4/79), and a specified number of days (51%, 40/79). For those cheerleaders who were prohibited from participating in cheerleading for a specified number of days (n = 40), the total number of days of cheerleading participation lost as a result of fall-related injuries was 739 days (mean = 18.5 ± 23.1, median = 10). The number of days lost by team type was as follows: All Star, 133 days (mean = 19.0 ± 18.0, median = 10); college, 295 days (mean = 29.5 ± 40.9, median = 12); high school, 279 days (mean = 14.7 ± 10.1, median = 14); middle school, 25 days (mean = 8.3 ± 5.1, median = 7); and elementary school, 7 days (n = 1).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to focus on the epidemiology of cheerleading fall-related injuries. Although fall-related injuries accounted for only 14% (79/567) of the injuries reported to Cheerleading RIO by US cheerleading teams during the 1-year study and 25% of the injuries to North Carolina competitive high school cheerleaders,6 these injuries have the potential to be catastrophic. As described previously, Mueller and Cantu8 published a description of 59 catastrophic cheerleading-related injury cases; 44 of these (75%) occurred as a result of a fall. Head injuries were sustained in 24 of these falls, 2 of which resulted in death. Four of the 59 cases involved cheerleaders who were tossed in the air and not caught by their teammates. In one case, a cheerleader sustained a fractured collarbone, damaged eardrum, and basilar skull fracture while practicing a pyramid 6 ft (1.83 m) above the gym floor with no spotters.

Pyramids and partner stunts accounted for 89% (70/79) of the fall-related injuries in the present study and 56% of the injuries in the study by Schulz et al.6 In our study, the maximum fall height was 11 ft (1.52 m); however, fall heights of 15 and 20 ft (4.57 and 6.10 m) have been reported.6,8,9 Macarthur et al11 found that the risk of severe injury increased 2-fold for falls from more than 4.9 ft (1.49 m), and Laforest et al12 reported that the risk of severe injury was 1.5 times greater for falls from playground equipment higher than 6.6 ft (2 m). The recommended maximum height for playground equipment ranges from 4.9 ft (1.5 m)13,14 to 6.6 ft (2 m).12 Fall heights of more than 2 ft (0.6 m) pose a significant risk for wrist fracture15; arm fracture risk is greatest for fall heights above 3.3 ft (1 m)14; and fall height is an important consideration when assessing the risk of sustaining a fatal head injury.16

In the study by Boden et al,9 the type of surface on which the injured cheerleader was performing was known for 74% (29/39) of the catastrophic injury cases described. In 21 of these 29 cases (72%), a hard, non–impact-absorbing surface was involved (asphalt, concrete, or a “hard gym surface”). In our study, 6% of the falls (5/79) occurred while the injured cheerleader was performing on a hard surface (wood, tile, or linoleum). In one case, a cheerleader was performing on an impact-absorbing surface (Tumbl Trak) but fell off onto a concrete floor.

Falls onto an impact-absorbing surface are less likely to cause serious injury than are falls onto a hard surface. The potential for life-threatening head-impact injuries can be minimized by increasing the shock-absorbing capacity of the surface and decreasing the height from which the person falls.17 Bare earth, grass, asphalt, and concrete are categorized as non–impact-absorbing surfaces,11 yet Hutchinson4 recommended that cheerleaders practice on grass rather than a hard gym floor. In the present study, 12 cheerleaders were injured when they fell onto a grass surface. Further research is needed to determine cheerleading-related injury rates associated with surfaces routinely used by cheerleaders during practices and performances.

In accordance with the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), guideline F1292-04, “Standard Specification for Impact Attenuation of Surfacing Materials Within the Use Zone of Playground Equipment,”17 Shields and Smith18 used a Triax 2000 (Alpha Automation, Trenton, NJ) to perform impact-attenuation tests on numerous surfaces on which cheerleaders routinely practice and perform and determined the critical height (maximum height below which a life-threatening head injury is not likely to occur) for each surface. In the current study, the most serious head injury sustained was a concussion or CHI. All 5 of the concussions or CHIs (100%) in the present study occurred during a fall from a height above the critical height for the surface upon which the cheerleader was performing at the time of injury.

One forearm fracture was sustained in the present study, and it occurred at a height of 4 ft (1.22 m), which was above the fall height at which the risk for arm fractures is greatest (3.3 ft [1.01 m])14 and at the critical height for the surface upon which the cheerleader was performing. Although the critical height is specifically related to the risk for a serious head injury, 80% (12/15) of the most serious types of injuries sustained by cheerleaders in our study occurred at or above the critical height for the surface on which the cheerleader was performing at the time of injury: concussion or CHI (100%, 5/5), dislocation (67%, 4/6), fracture (50%, 1/2), and ACL tear (100%, 2/2).

One major factor must be considered when using critical height data to assess the suitability of a surfacing material for use while performing a particular type of cheerleading maneuver: all of the Triax 2000 test results assume a straight vertical fall onto the surface. As the results of our study clearly show, cheerleading-related falls frequently involve collisions with other cheerleaders on the way down, before the injured cheerleader strikes the surfacing material. These collisions may decrease the velocity at which the cheerleader hits the surface. Future authors need to examine these types of situations and determine their effect on the probability of injury.

Additional research is needed to determine the critical height for injuries other than serious head injuries. Two studies14,15 were conducted to determine the critical height for arm fractures resulting from impact forces during falls. Another group19 determined that preventing playground fall-related arm fracture requires surface impact-attenuation guidelines that are distinct from head injury–prevention guidelines. In a different study,20 the investigators used a multidisciplinary approach to identify and quantify risk and protective factors for arm fracture resulting from falls from playground equipment. Test-dummy experiments have been used to assess pediatric injury risk in simulated short-distance falls,21 and Bertocci et al22 examined the influence of fall height and impact surface on the biomechanics of feet-first free falls among children. None of these authors presented conclusive data. However, until more definitive data are available, it seems prudent to limit the fall height during cheerleading maneuvers to less than the critical height (as defined by ASTM standard F1292-0416) for the surface upon which the maneuver is being performed.18

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small. Second, fall heights reported in this study are estimates made by the team coach or injured cheerleader (or both) and were not actually measured. Third, teams participating in this study were not selected based on a probability sample as a result of the lack of a comprehensive/authoritative list (sampling frame) of all cheerleading teams in the United States; therefore, the study results may not be generalizable to all cheerleading teams in the United States.2 In addition, because cheerleading coaches in the United States are not required to maintain an injury log or submit injury reports to state agencies, a source for cross-checking the accuracy of the injury data reported to Cheerleading RIO was not available. Last, we did not collect exposure data regarding the surfaces on which cheerleaders practiced and performed. This information would have provided additional insight into the association of surface type with serious injury.

CONCLUSIONS

Cheerleading-related falls may result in catastrophic injuries and even death. Most of the serious injuries in the present study were sustained on artificial turf, grass, traditional foam floors, or wood floors from fall heights ranging from 4 to 11 ft (1.22–1.52 m). Approximately half (51%) of the fall-related injuries were sustained by high school cheerleaders, and 89% of the fall-related injuries were sustained while the cheerleader was attempting a stunt or pyramid. The risk for serious injury increased as fall height increased or as the impact-absorbing capacity of the surfacing material decreased (or both). The incidence of cheerleading fall-related injuries may be decreased by requiring cheerleaders to perform maneuvers on appropriate impact-absorbing surfaces at heights that do not exceed the critical height for that surface (as defined by ASTM F1292-0417).18

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this study was provided by the Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital. Debbie Bracewell, from the National Council for Spirit Safety and Education, Lisa Thompson, from Cheer Ltd, and Steve Wedge, from Cheerleaders of America, Inc, helped to categorize the cheerleading maneuvers.

Footnotes

Brenda J. Shields, MS, contributed to conception and design; acquisition and analysis and interpretation of the data; and drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the article. Gary A. Smith, MD, DrPH, contributed to conception and design and critical revision and final approval of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.CBS Broadcasting Inc. Cheerleader injured in fall on court. March 6, 2006. http://wbztv.com/sports/Krisit.Yamaoka.Cheerleader.2.577025.html. Accessed June 25, 2008.

- 2.Shields B. J., Smith G. A. Cheerleading-related injuries in the United States: a prospective surveillance study. J Athl Train. 2009;44(6):567–577. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.6.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannone L., Williamson T. L. A philosophy of safety awareness. In: George G. S., editor. American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Administrators Cheerleading Safety Manual. Memphis, TN: The UCA Publications Department; 2006. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutchinson M. R. Cheerleading injuries: patterns, prevention, case reports. Physician Sportsmed. 1997;25(9):83–96. doi: 10.3810/psm.1997.09.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields B. J., Smith G. A. Cheerleading-related injuries to children 5 to 18 years of age: United States, 1990–2002. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):122–129. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz M. R., Marshall S. W., Yang J., Mueller F. O., Weaver N. L., Bowling N. M. A prospective cohort study of injury incidence and risk factors in North Carolina high school competitive cheerleaders. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(2):396–405. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson B. H., Hubbard M., Redus B., et al. An assessment of high school cheerleading: injury distribution, frequency, and associated factors. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(5):261–265. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2004.34.5.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller F. O., Cantu R. C. National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research: twenty-fifth annual report, fall 1982–spring 2007. http://www.unc.edu/depts/nccsi/AllSport.htm. Accessed August 19, 2008.

- 9.Boden B. P., Tacchetti R., Mueller F. O. Catastrophic cheerleading injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(6):881–888. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310062501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles S. B., Marshall S. W., Guskiewicz K. M. Issues in estimating risks and rates in sports injury research. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):207–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macarthur C., Hu X., Wesson D. E., Parkin P. C. Risk factors for severe injuries associated with falls from playground equipment. Accid Anal Prev. 2000;32(3):377–382. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laforest S., Robitaille Y., Lesage D., Dorval D. Surface characteristics, equipment height, and the occurrence and severity of playground injuries. Inj Prev. 2001;7(1):35–40. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalmers D. J., Marshall S. W., Langley J. D., et al. Height and surfacing as risk factors for injury in falls from playground equipment: a case-control study. Inj Prev. 1996;2(2):98–104. doi: 10.1136/ip.2.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherker S., Ozanne-Smith J., Rechnitzer G., Grzebieta R. Out on a limb: risk factors for arm fracture in playground equipment falls. Inj Prev. 2005;11(2):120–124. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.007310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu J., Robinovitch S. N. Prediction of upper extremity impact forces during falls on the outstretched hand. J Biomech. 1998;31(12):1169–1176. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cory C. Z., Jones M. D. Development of a simulation system for performing in situ surface tests to assess the potential severity of head impacts from alleged childhood short falls. Forensic Sci Int. 2006;163(1–2):102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM F1292-04 Standard Specification for Impact Attenuation of Surfacing Materials Within the Use Zone of Playground Equipment. West Conshohocken, PA: American Society for Testing and Materials; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shields B. J., Smith G. A. The potential for brain injury on selected surfaces used by cheerleaders. J Athl Train. 2009;44(6):595–602. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.6.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherker S., Ozanne-Smith J. Are current playground safety standards adequate for preventing arm fractures? Med J Aust. 2004;180(11):562–565. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherker S., Ozanne-Smith J., Rechnitzer G., Grzebieta R. Development of a multidisciplinary method to determine risk factors for arm fracture in falls from playground equipment. Inj Prev. 2003;9(3):279–283. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertocci G. E., Pierce M. C., Deemer E., Aguel F., Janosky J. E., Vogeley E. Using test dummy experiments to investigate pediatric injury risk in simulated short-distance falls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(5):480–486. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.5.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertocci G. E., Pierce M. C., Deemer E., Aguel F., Janosky J. E., Vogeley E. Influence of fall height and impact surface on biomechanics of feet-first free falls in children. Injury. 2004;35(4):417–424. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]