Abstract

The NF1 gene that is altered in patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis encodes a neurofibromin (NF1) protein that functions as a tumor suppressor. In this report, we show for the first time physical interaction between neurofibromin and focal adhesion kinase (FAK), the protein that localizes at focal adhesions. We show that neurofibromin associates with the N-terminal domain of FAK, and that the C-terminal domain of neurofibromin directly interacts with FAK. Confocal microscopy demonstrates co-localization of NF1 and FAK in the cytoplasm, peri-nuclear and nuclear regions inside the cells. Nf1+/+ MEF cells expressed less cell growth during serum deprivation conditions, and adhered less on collagen and fibronectin-treated plates than Nf1−/− MEF cells, associated with changes in actin and FAK staining. In addition, Nf1+/+ MEF cells detached more significantly than Nf1−/− MEF cells by disruption of FAK signaling with the dominant-negative inhibitor of FAK, C-terminal domain of FAK, FAK-CD. Thus, the results demonstrate the novel interaction of neurofibromin and FAK and suggest their involvement in cell adhesion, cell growth, and other cellular events and pathways.

Keywords: Focal Adhesion Kinase, Neurofibromin, Neurofibromatosis, Protein interaction, Focal adhesions

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant disorder predominantly characterized by nerve sheath tumors called neurofibromas [1]. The tumors are caused by loss of function of both alleles of the NF1 gene (germline mutation and somatic mutation) in Schwann cells and can transform into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs). Mutations in the NF1 gene also predisposes to sarcomas, astrocytomas, juvenile myeloid leukemia and learning disabilities.

Neurofibromin is the 2,818 amino acid protein (est. 280 kDa) encoded by the NF1 gene on chromosome 17q11.2 [2]. The gene spans 280kb of genomic DNA and contains 60 exons [3]. Neurofibromin is ubiquitously expressed at low levels with highest expression levels seen in neural crest derived tissues including neurons, Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes [4]. It is a tumor suppressor with a functional GTPase-activating protein domain that negatively regulates Ras [5]. Recent reports suggest that neurofibromin may play a critical role in other signaling pathways and cellular functions. For example, inactivating mutations of the NF1 gene have been reported in non-NF1 related tumors without impaired regulation of ras [6–10]. Recently, neurofibromin was found to regulate mTor, the target of rapamycin [11], and to confer sensitivity to apoptosis through ras-independent pathways [12]. Furthermore, a nuclear localization sequence was recently identified in exon 43 of the protein [13] and was involved in neurofibromin shuttling between cytoplasm and nucleus, suggesting a possible novel role for the protein in the nucleus. The Akt signaling pathway is reportedly regulated by neurofibromin, in association with caveolin-1 [14]. Neurofibromin has also been suggested to associate with cytoskeletal and focal adhesion proteins such as actin filaments and microtubules [15, 16] and to regulate cell adhesion, motility and cytoskeletal reorganization [14, 16, 17]. In addition, Nf1 null mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells are highly motile and display a disorganized morphology with increased actin stress fibers [14], and knockdown of neurofibromin in HeLa and HT1080 cells with NF1 siRNA increased paxillin localization at focal adhesions, leading to increased focal adhesion formation [16].

One of the main proteins localized at focal adhesions (contact sites of cells with extracellular matrix) is the Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK), a 125kDa non-receptor tyrosine kinase that is encoded by the PTK2 gene located on chromosome 8q24 in humans and chromosome 15 in mice [18, 19]. FAK is a critical regulator of many cellular processes including adhesion, proliferation, cell spreading, motility and survival [20–24]. FAK has been shown to be overexpressed in many types of tumors [25–29] and to be up-regulated in the early stages of tumorigenesis [25, 30]. The FAK protein contains an N-terminal domain with a primary autophosphorylation site (Tyr-397) that directly interacts with the Src homology 2 domain [31] and PI-3 kinase [22]; a central catalytic domain with two major sites of phosphorylation (Tyr-576/577) and a C-terminal domain containing two proline-rich segments and a focal adhesion-targeting subdomain that binds paxillin, talin, and other proteins [22, 32]. The N-terminal domain of FAK associates with the epidermal growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor [33, 34], with cytoplasmic tails of integrins [35] and with death receptor complex-binding protein, RIP [36]. The N-terminal domain of FAK also complexes with a protein inhibitor of activated STAT1 (PIAS1) [37], which causes FAK sumoylation and increases its autophosphorylation activity, suggesting a novel FAK role in signaling between the plasma membrane and the nucleus [37]. Recently, the N-terminus of FAK was shown to interact directly with the tumor suppressor p53 to enhance its degradation in the nucleus [38, 39].

We have shown that an analogous C-terminal FAK fragment construct, called FRNK or FAK-CD, can regulate FAK function in a dominant negative way by decreasing FAK phosphorylation and displacing FAK from the focal adhesion [40, 41]. Overexpression of FAK-CD in cancer cells leads to cell rounding, detachment, reduction of invasion, and apoptosis [32, 42–45]. FAK has been shown to suppress both transformation-associated apoptosis [41] and anoikis (detachment-induced apoptosis) of epithelial cells [46], promoting survival in cells subjected to apoptotic signals. In addition, constitutively active forms of FAK prevented anoikis and stimulated transformation of epithelial cells, resulting in anchorage-independent growth and tumor formation in nude mice [46].

Because neurofibromin has been suggested to be important in many FAK signaling pathways such as focal adhesion formation, cell motility, and cytoskeletal reorganization [16], and several other reports suggesting indirect link of FAK and NF1 [14],[47], we analyzed whether FAK and neurofibromin can interact directly. First, we show that neurofibromin is expressed in many types of cancer cells. Then we show that neurofibromin interacts directly with FAK and mapped this interaction to the N-terminal domain of FAK by immunoprecipitation and pull-down assays. We show that FAK and neurofibromin co-localize by confocal microscopy. In addition, Nf1+/+ MEF cells expressed significantly less cell growth in low-serum conditions and adhered significantly less than Nf1−/− on collagen I and fibronectin-treated plates, associated with changes of actin and FAK cellular distribution. We show that the dominant-negative FAK protein, adenoviral FAK-CD caused more detachment of the Nf1+/+ MEF cells than in Nf1−/− MEF cells. Thus, this is the first report demonstrating direct interaction between FAK and neurofibromin that can play an important role in cellular signaling.

Materials and Methods

Cells and cell culture

The normal mouse embryonic fibroblast Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells and normal Schwann cells (pn97.4) and tumor Schwann cells (SNF02.2, SNF94.3, SNF96.2) were kindly provided by Dr. Margaret Wallace at the University of Florida, Gainesville and were maintained in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum and 1µg/ml penicillin/streptomycin. The SV40 Immortalized Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells were kindly provided by Dr. R. Stein, at the Tel Aviv University in Israel and were maintained in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum and 1µg/ml penicillin/streptomycin. BT474 (human breast cancer) cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1µg/ml penicillin/streptomycin and 5µg/ml insulin.

DNA Constructs

The N-terminal, Central/Kinase and C-terminal domains of FAK were generated by PCR with the gene-specific primers (available upon request). All sequences were analyzed by automatic sequencing in both directions (University of Florida Sequencing Facility). For generation of GST-fusion proteins, the C-terminal fragment of neurofibromin (aa 2205 – 2785) and FAK fragments (N-terminal (aa 1–423), kinase domain (aa 416–676), and C-terminal domain (aa 677–1052) were cloned into the pGEX-4T1 GST vector (Amersham Biosciences).

Antibodies and Reagents

Monoclonal anti-FAK (4.47) antibody specific to the N-terminal domain of FAK was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., and BD Transduction Laboratories, respectively. Polyclonal antibody for the C-terminal domain of FAK, C-20, was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Polyclonal antibody for the C-terminal domain of neurofibromin was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Monoclonal antibody for the C-terminal domain of neurofibromin was obtained from Abnova. HA-tagged antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Inc. The recombinant purified GPF expressed in baculoviral expression vector system was kindly provided by Dr. S. Haskill. The recombinant purified FAK expressed in baculoviral expression vector system was generated and described in [38]. Polyclonal antibody for neurofibromin (SC-67) was obtained from Santa Cruz. Monoclonal antibody for neurofibromin C-terminus was obtained from Abnova (H00004763-Q01).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Cells were washed twice with cold 1x PBS and lysed on ice for 30 min in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X, 0.5% NaDOC, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM NaVO3, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors: 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride, 1 µg/ml aprotinin. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were determined using Bio-Rad kit. The cleared lysates with equivalent amount of protein were incubated with 5 µl of primary antibody for 1 h at 4 °C and 25 µl of protein A/G-agarose beads (Oncogene Research Products Inc.). The precipitates were washed with the lysis buffer three times and re-suspended in 30 µl of 2x Laemmli buffer. The boiled samples were loaded on Ready SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) and used for Western blot analysis with the protein-specific antibody. The blots were stripped in a stripping solution (Bio-Rad) at 37 °C for 15 min and then re-probed with the primary antibody for checking equal loading of proteins. Immunoblots were developed with chemiluminescence Renaissance reagent (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences).

Immunostaining

Cells were fixed on coverslips with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1x PBS for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.2%Triton X-100 for 5 min on ice. Cells were blocked with 25% normal goat serum in 1x PBS for 30 min, washed in 1x PBS, and incubated with primary antibody diluted 1:200 in 25% goat serum in 1x PBS for 1h. Cells were washed in 1x PBS three times and a FITC or Rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (1:400 dilution in 25% goat serum) was applied to the coverslip for 1h. After washing three times with 1x PBS, cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 for detecting nuclei. After mounting, cells were examined under a fluorescent Zeiss microscope or Leica microscope.

Expression of Recombinant GST Fusion Proteins

GST fusion proteins containing different domains of FAK (GST-FAK-NT, FAK-Kinase, and FAK-CD) and C-terminal domain of neurofibromin (GST-NF1-CD) were engineered by PCR. The fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia Coli bacteria by incubation with 0.2mM isopropyl β-D-galactopyranoside for 6 h at 37 °C. The bacteria were lysed by sonication, and the fusion proteins were purified with glutathione-agarose beads as described in [38]. Isolated GST-FAK-NT, -Kinase domain and FAK-CD were confirmed by Western blot analysis with FAK-domain specific antibodies [38].

Pull-down Assay

For the pull-down binding assay, cell lysates (0.5mg) or purified recombinant baculoviral protein (0.1 µg) were precleared with 10 µg of GST immobilized on glutathione-agarose beads by rocking for 1 h at 4 °C. The washed pre-cleared lysates were incubated with 2–4 µg of GST fusion protein immobilized on the glutathione-agarose beads for 1 h at 4 °C and then washed three times with lysis buffer. Equal amounts of GST fusion proteins (2µg) were used for the binding assay. Bound proteins were boiled in 2x Laemmli buffer and and analyzed by Western blotting.

Phage display assay

Phage display assay was performed with the purified N-terminal domain of FAK protein (1–422 aa) using the 7 amino acid phage library consisting of >2 ×109 sequences (New England Biolabs) according to New England Biolabs protocol.

Apoptosis Assay

Cells treated with Ad FAK-CD were collected and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in 1x PBS solution. Detection of apoptosis was done with Hoechst 33342 method as previously described. Briefly, Hoechst 33342 in 1x PBS solution (1µg/ml) was added to the fixed cells for 10 min, and cells were washed twice with 1x PBS, spread evenly on the slide, and examined under a fluorescent microscope. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated on a blind basis as a ratio of apoptotic cells with fragmented nuclei to the total number of non-apoptotic cells with large non-fragmented, non-condensed nuclei in three independent experiments in several fields with the fluorescent microscope. More than 300 cells were analyzed for each experimental sample.

Adhesion Assay

96 well plates were coated with 1–10 µg /ml of collagen I, fibronectin or poly-L-lysine at 37°C for 1.5 hr and 1% BSA as control. The plate wells were washed with 1xPBS and blocked with 1% BSA at 37°C for 30 min. The blocking solution was aspirated and 20,000 cells in the medium with 0.1% BSA were added per well and incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 1 hour. The plate wells were then washed multiple times with 1% BSA in 1xPBS, fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature (R.T.), stained with 2% crystal violet (in 2% ethanol) for 10 minutes at R.T., washed 4 times with 1xPBS and allowed to dry for 30 minutes. The absorbed dye was dissolved with 2% SDS, and absorbance read at 562 nm on an Elisa plate reader to determine adhesion.

Confocal Microscopy

Immunostained slides were optically sectioned under a confocal laser inverted Leica microscope, as described [38]. Images were captured per channel and merged with Leica CS software.

Adenovirus Transfection

The adenoviral constructs Ad LacZ, Ad GFP, and Ad FAK-CD are previously described in [41]. Cells were plated and allowed to grow for 24 h and then infected with Ad LacZ (or Ad GFP) or Ad FAK-CD for various time points at a concentration of 300ffu/cell. Expression of HA-tagged FAK-CD was detected by Western blotting with anti-HA monoclonal antibody.

Cell Growth Assay

MEF cells were starved for 24h, split in to a density of 5 × 104 cells/6-cm plate in triplicate, and then stimulated with 0.5% and 2.5% serum. After indicated time, cells were trypsinized and counted.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Student’s t-test. A p-value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

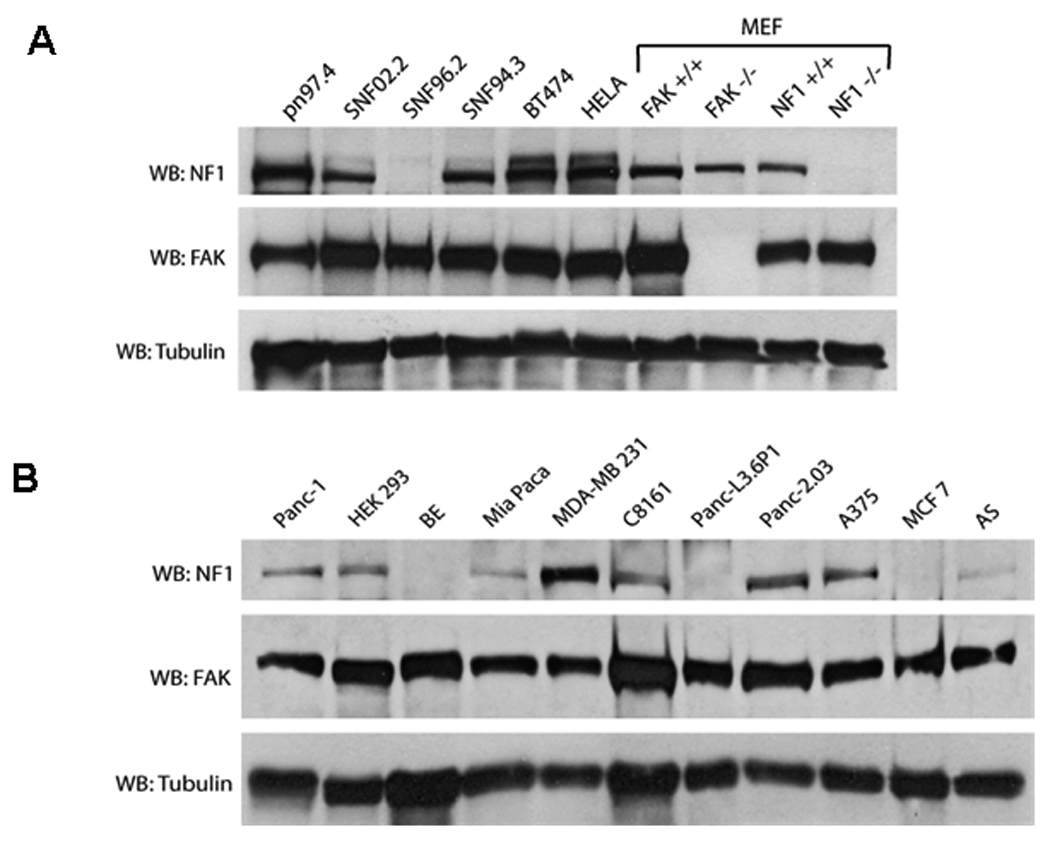

Neurofibromin and FAK are both expressed in normal and most tumor cells

We analyzed neurofibromin and FAK expression levels in many cancer cell lines including Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors (MPNST) (SNF02.2, SNF94.3, SNF96.2), neuroblastoma (BE, AS), melanoma (A375, C8161), pancreatic tumors (Panc-1, Panc-2.03, Panc-L3.6p1, Mia Paca), breast cancer (BT474, MCF7, MDA-MB 231), normal human Schwann cells (pn97.4), Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK 293) cells, human cervical cancer (HeLa) cells, and isogenic normal mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) FAK+/+ and FAK−/− and Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− cells (Figures 1 A and B). The results showed variable expression of both neurofibromin and FAK in many cancer types. Importantly, the results demonstrate that both FAK and neurofibromin are expressed in many types of tumor cells.

Figure 1. Expression of neurofibromin and FAK in different cancer cell lines.

Western blotting analysis of neurofibromin and FAK expression was performed in normal Schwann cells (pn97.4), Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors (MPNST) (SNF02.2, SNF94.3, SNF96.2), breast cancer cells BT474, human cervical cancer HELA cells, mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells (FAK+/+ and FAK−/−, Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− (upper panel), and in pancreatic tumors (Panc-1, Mia Paca, Panc-L3.6p1, Panc-2.03), HEK 293 cells, neuroblastoma (BE, AS), melanoma (A375, C8161) and breast cancer MCF7, MDA-MB231 cells (lower panel).

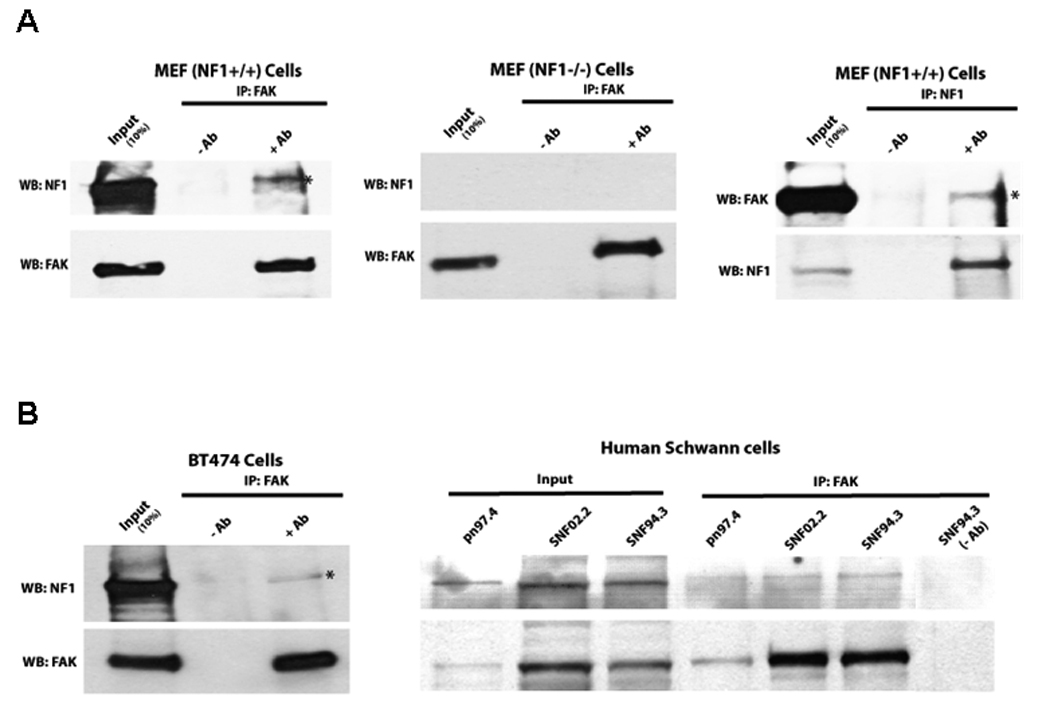

FAK and neurofibromin proteins interact in vivo

To determine whether FAK and neurofibromin (NF1) interact in vivo, we performed co-immunoprecipitation of FAK and NF1 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) cells (Figure 2A). First we immunoprecipitated endogenous FAK protein in Nf1+/+ (Figure 2A, left panels) and Nf1−/− MEF cells (Figure 2A, middle panels) and performed Western blot with neurofibromin antibody. Immunoprecipitation of FAK detected neurofibromin in complex with FAK in Nf1+/+ cells (Figure 2A, left panels), while it did not detect in control Nf1−/− MEF cells (Figure 2A, middle panels). In addition, we immunoprecipitated neurofibromin and detected FAK in complex with the neurofibromin in Nf1+/+ MEF cells (Figure 2A, right panels). FAK and neurofibromin binding was not detected in control immunoprecipitations without antibody (Figure 2A). Thus, neurofibromin and FAK interact in the Nf1+/+ mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells in vivo.

Figure 2.

Figure 2A. FAK and neurofibromin interact in Nf1+/+ cells in vivo. Left and middle panels: Immunoprecipitation of FAK was performed with anti-FAK C20 antibody followed by Western blotting with neurofibromin antibody in Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells. Immunoprecipitation without antibody was used as a control (-Ab). Then membrane was stripped and Western blotting with FAK antibody was performed. FAK and NF1 interact in Nf1+/+, but not in Nf1−/− MEF cells. Right panels: Immunoprecipitation with NF1 antibody detects interaction with FAK in Nf1+/+ MEF cells. Immunoprecipitation was performed with NF1 antibody, and then Western blotting with FAK antibody. Then membrane was stripped and Western blotting was performed with NF1 antibody. FAK and NF1 interacted in vivo in NF+/+ cells.

Figure 2B. FAK and neurofibromin interact in breast cancer BT474 cells and in Human Schwann cells in vivo Immunoprecipitation with FAK antibody detected interaction with NF1 in BT474 (left panels) and in normal pn97.4 and Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors (MPNST) SNF02.2 and SNF94.3 Schwann cells (right panels). Immunoprecipitation was performed as above.

To demonstrate interaction of FAK and neurofibromin in human cell lines, we performed co-immunoprecipitation of FAK and neurofibromin in human BT474 breast cancer cells (Figure 2B, left panels) and in human normal Schwann cells (pn97.4) and Schwann-derived MPNST cells (SNF02.2, SNF94.3) (Figure 2B, right panels). Immunoprecipitation of FAK detected neurofibromin in complex with FAK in all human cell lines (Figure 2B). Thus, endogenous FAK and neurofibromin interact in vivo.

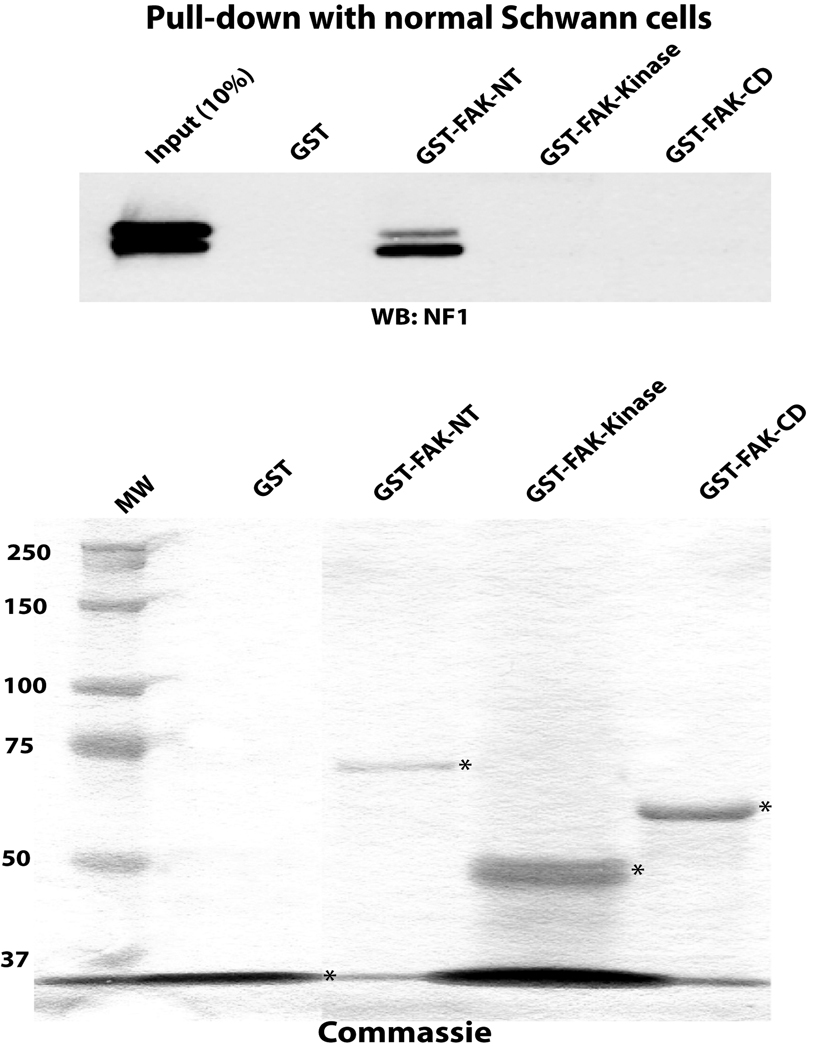

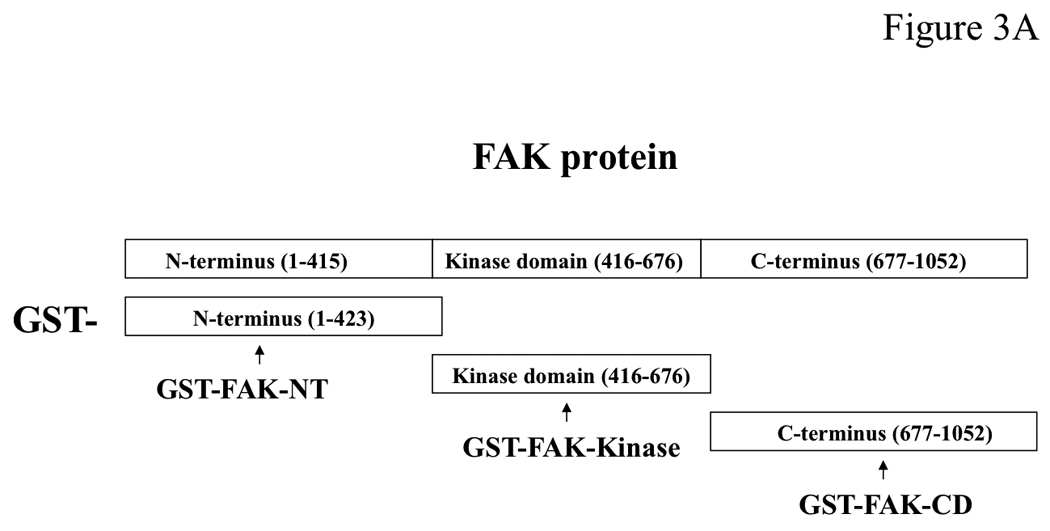

Neurofibromin interacts with the N-terminal domain of FAK in Vitro

To identify which domain of FAK interacts with neurofibromin, we performed pull-down assay with the N-terminal, FAK-NT; Central, FAK kinase domain, and C-terminal, FAK-CD domains of FAK shown on (Figure 3A) using cell extracts of normal (pn97.4) Schwann cells (Figure 3B, upper panel). The Coomassie stained GST-FAK domain proteins are shown on (Figure 3B, lower panel). Neurofibromin was pulled down in a complex with the FAK-NT protein (Figure 3B), while it did not interact with control GST protein or the kinase, GST-FAKKinase and C-terminal domains of FAK, GST-FAK-CD proteins (Figure 3B). These results demonstrate that neurofibromin interacts with the N-terminal domain of FAK.

Figure 3. NF1 interacts with the N-terminal domain of FAK.

A, The scheme of the GST FAK fusion proteins used for pull-down assay to demonstrate interaction of NF1 with FAK: GST-N-terminal FAK-NT; Central, FAK-Kinase and C-terminal FAK-CD domains. The GST proteins are marked by arrows. Upper panel: The three FAK domains (FAK-NT, FAK-Kinase and FAK-CD) were used in a pull-down assay with normal Schwann cells to identify which domain of FAK interacts with neurofibromin. After pull-down assay, Western blotting with the NF1 antibody was performed. The NF1 antibody detected of NF1 protein. Two bands of NF1 protein in normal Schwann cells were detected at high resolution gel electrophoresis conditions. Pull-down assay demonstrates interaction of NF1 with the N-terminal domain, but not with the Kinase or C-terminal domains of FAK. Lower panel: Coomassie staining of GST-FAK domain proteins. The GST-FAK protein domains were analyzed by Coomassie staining (lower panel, GST-proteins are marked by asterisks).

C-terminal domain of neurofibromin directly interacts with FAK in Vitro

Since we demonstrated interaction between the N-terminal domain of FAK (FAK-NT) and neurofibromin, we performed phage display assay with the purified FAK-NT protein using a degenerate 7 amino acid phage library consisting of >2 × 109 peptide sequences (New England Biolabs). We identified a 7 amino acid peptide HSTPPKM with 71% homology (5 out of 7a.a.; homologous amino acids are underlined) to neurofibromin peptide inside the nuclear localization sequence of neurofibromin (NF1-NLS) KRQEMESGITTPPKMRR (2534 – 2550a.a.) in the C-terminal domain of neurofibromin (not shown) that additionally supports our data on interaction of neurofibromin with the N-terminal domain of FAK. The C-terminal domain of neurofibromin has been suggested to have additional functions independent from the NF1 GAP-domain [1, 13, 47, 48].

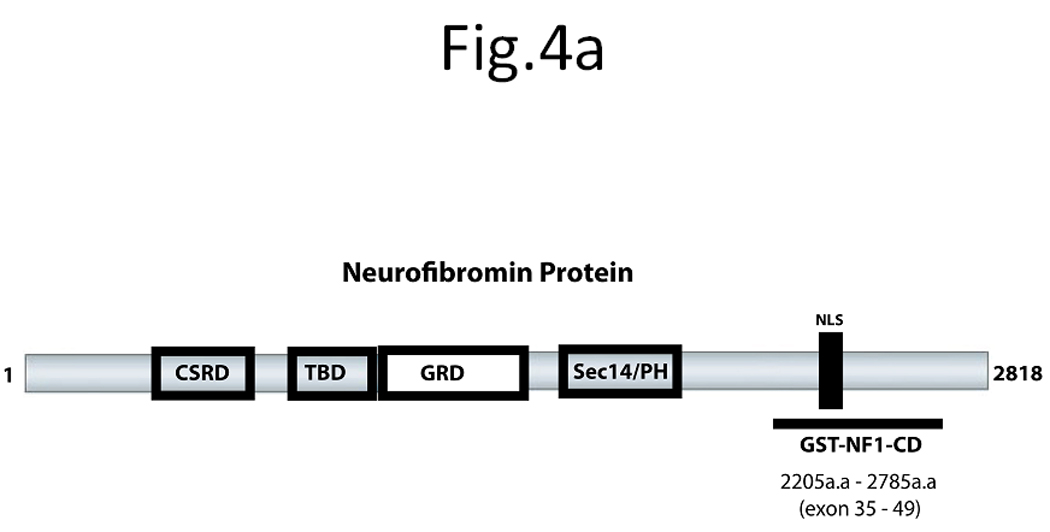

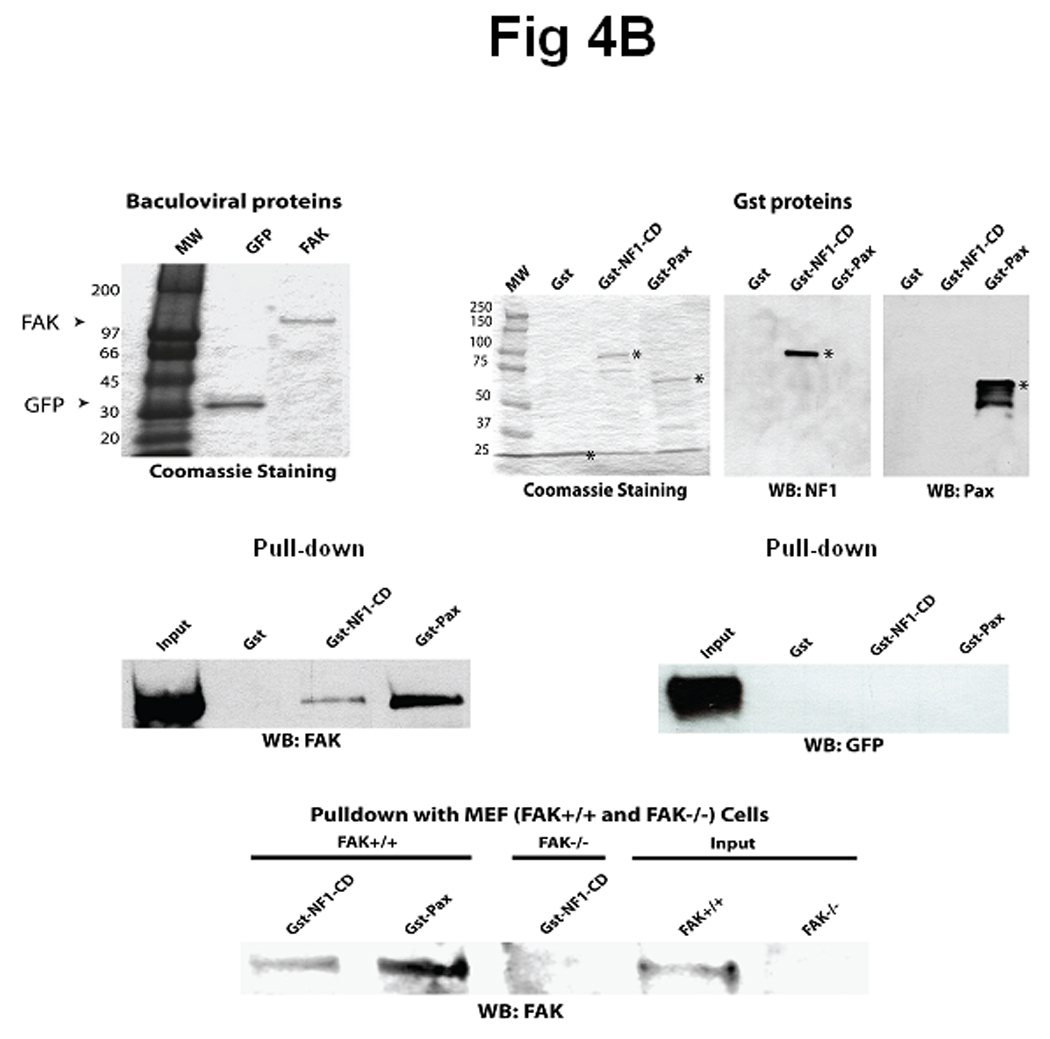

To determine that C-terminal domain of neurofibromin directly interacts with FAK, we generated the GST-NF1, containing the C-terminal part of neurofibromin, called GST-NF1-CD. To determine whether NF1 directly interacts with FAK, we expressed a GST-NF1-CD protein (C-terminal aa 2205 – 2785) (Figure 4A), containing a fragment of the C-terminal domain of neurofibromin and performed a pull-down assay with the baculoviral purified FAK (Figure 4B, left panel). As a control for non-specific binding, we used baculoviral purified GFP (Figure 4B, left panel). For pull-down-assay, we used GST-NF1-CD protein; GST-Paxillin (a known binding partner of FAK) used as a positive control for binding with FAK and GST protein, used as a negative control for non-specific binding (Figure 4B, right panels). All GST proteins were analyzed by Coomassie staining and confirmed by Western blotting with specific antibodies (Figure 4B, right panels). The pull-down assay showed binding of FAK with GST-NF1-CD protein and GST-Paxillin protein, but not with GST protein (Figure 4C, left panel). To check specificity of GST-NF1 binding with FAK, we used purified recombinant baculoviral GFP protein in the same pull-down assay with GST, GST-NF1-CD and GST-paxillin (Figure 4C, right panel). We did not detect binding of control GFP protein (Figure 4C, right panel) with the GST-NF1-CD protein compared with the FAK protein (Figure 4C, left panel), indicating the specificity of FAK and neurofibromin binding. Thus, the C-terminal domain of neurofibromin directly interacts with FAK in vitro.

Figure 4. Direct interaction between FAK and neurofibromin in vitro.

A) The scheme of neurofibromin domains structure. The scheme demonstrates the location of the recombinant C-terminal domain of NF1, GST-NF1-CD fusion protein (2205-2785 aa) inside neurofibromin protein, containing the CSRD (cysteine/serine Rich domain), TBD (tubulin binding domain, GRD (GAP-Related domain), Sec14 (sec14 domain) and NF1-NLS (nuclear localization signal). B) C-terminal domain of NF1 and FAK proteins directly interact in vitro. Left panel: Baculoviral purified FAK and GFP proteins were used for pull-down assay. Coomassie staining shows the fusion proteins that were confirmed by Western blotting with GFP and FAK antibodies [38]. Right panel: Coomassie staining and Western blotting analysis of GST, GST-NF1-CD and GST-paxillin fusion proteins (Materials and Methods) used in pull-down assay. Asterisks mark GST-fusion proteins. Western blotting with NF1 antibody and paxillin antibody confirmed NF1 and paxillin proteins. C). Pull-down with baculoviral FAK demonstrated direct binding with the C-terminal domain of NF1 protein. Left panel: Pull-down assay was performed with baculoviral FAK protein and GST, GST-NF1-CD and GST-paxillin. C-terminal domain of NF1 directly binds FAK protein. No binding of FAK with the negative control GST protein is detected, while it was detected with the positive control GST- paxilllin protein. Right panel: Pull-down with baculoviral GFP protein did not detect binding with FAK. The same pull-down as with baculoviral FAK protein was performed with baculoviral GFP protein. No binding of GST-NF1-CD was detected with GFP protein.

D) Interaction of neurofibromin with FAK in FAK+/+, but not in FAK−/− MEF cells. Pull-down assay of GST-NF1-CD protein and demonstrates interaction between GST-NF1-CD with endogenous FAK protein in FAK+/+, but not in FAK−/− MEF cell extracts.

To determine whether GST-NF1-CD binds to endogenous FAK protein and show specificity of the binding we performed the same pull-down assay using FAK+/+ and FAK−/− MEF cell extracts (Figure 4D). The pull-down assay showed binding of GST-NF1-CD with endogenous FAK protein in FAK+/+ MEF cells, but not in FAK−/− MEF cells (Figure 4D). Thus, C-terminal domain of NF1 specifically interacts with endogenous FAK.

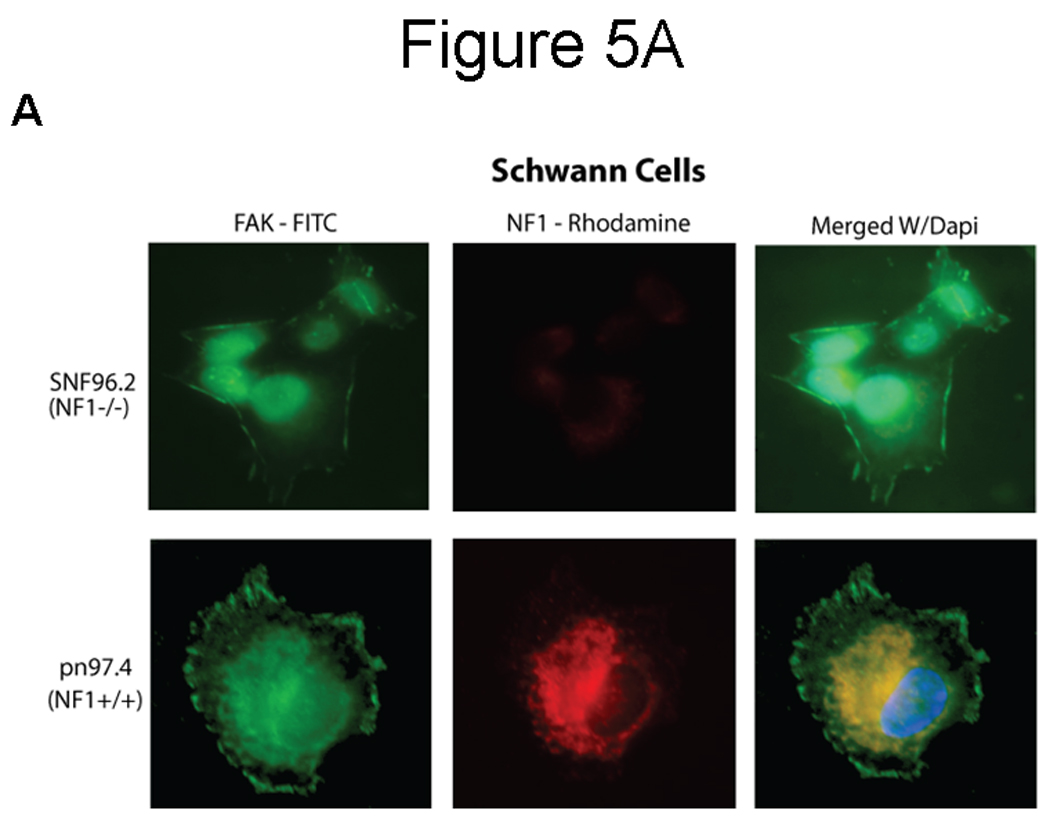

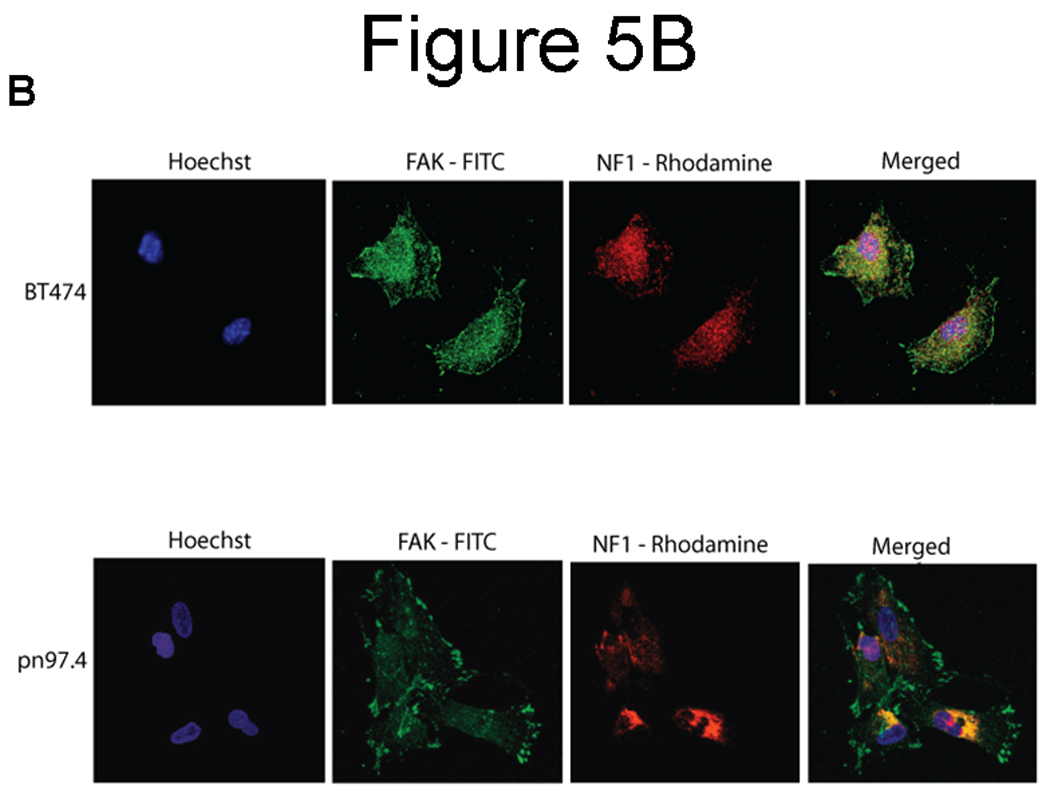

Neurofibromin co-localizes with FAK

To determine co-localization and intracellular distribution of FAK and neurofibromin, we performed immunostaining of normal human Schwann cells (pn97.4) Nf1+/+ and MPNST Schwann cells (SNF96.2) lacking neurofibromin expression, Nf1−/− (Figure 5A). Neurofibromin was detected mostly in the cytoplasm, while FAK was detected in the cytoplasm and at the focal adhesions (Figure 5A). FAK co-localized with neurofibromin in the cytoplasmic, peri-nuclear and nuclear regions (Figure 5A, lower panel) in pn97.4, Nf1+/+ cells. There were no NF1 expression and co-localization in control SNF96.2, Nf1−/− cells (Figure 5A, upper panel). To precisely determine co-localization, we performed confocal microscopy analysis of BT474 breast cancer cells (Figure 5B, upper panel) and pn97.4 (Figure 5B, lower panel). Confocal microscopy detected co-localization in the cytoplasmic, peri-nuclear and nuclear regions in both cell types (Figure 5B). These results demonstrate co-localization between neurofibromin and FAK proteins.

Figure 5. Co-localization of neurofibromin with FAK.

A) Immunocytochemical and fluorescence microscopy analysis of FAK and neurofibromin localization in normal Schwann cells (pn97.4) (lower panel) and tumor Schwann cells (SNF96.2) lacking neurofibromin expression) (upper panel). FAK and neurofibromin co-localized in the cytoplasmic, peri-nuclear and nuclear regions in pn97.4 (Nf1+/+) cells. No co-localization is detected in SNF96.2 (Nf1−/−) cells. B) Confocal microscopy detects interaction of NF1 and FAK in breast cancer BT474 cells and pn97.4 Schwann cells. FAK and neurofibromin co-localization was observed in the cytoplasmic, peri-nuclear and nuclear regions in both cell lines.

Nf1+/+ MEF cells express significantly less cell growth during serum deprivation and adhere significantly less than Nf1−/− MEF cells on Collagen-I and fibronectin

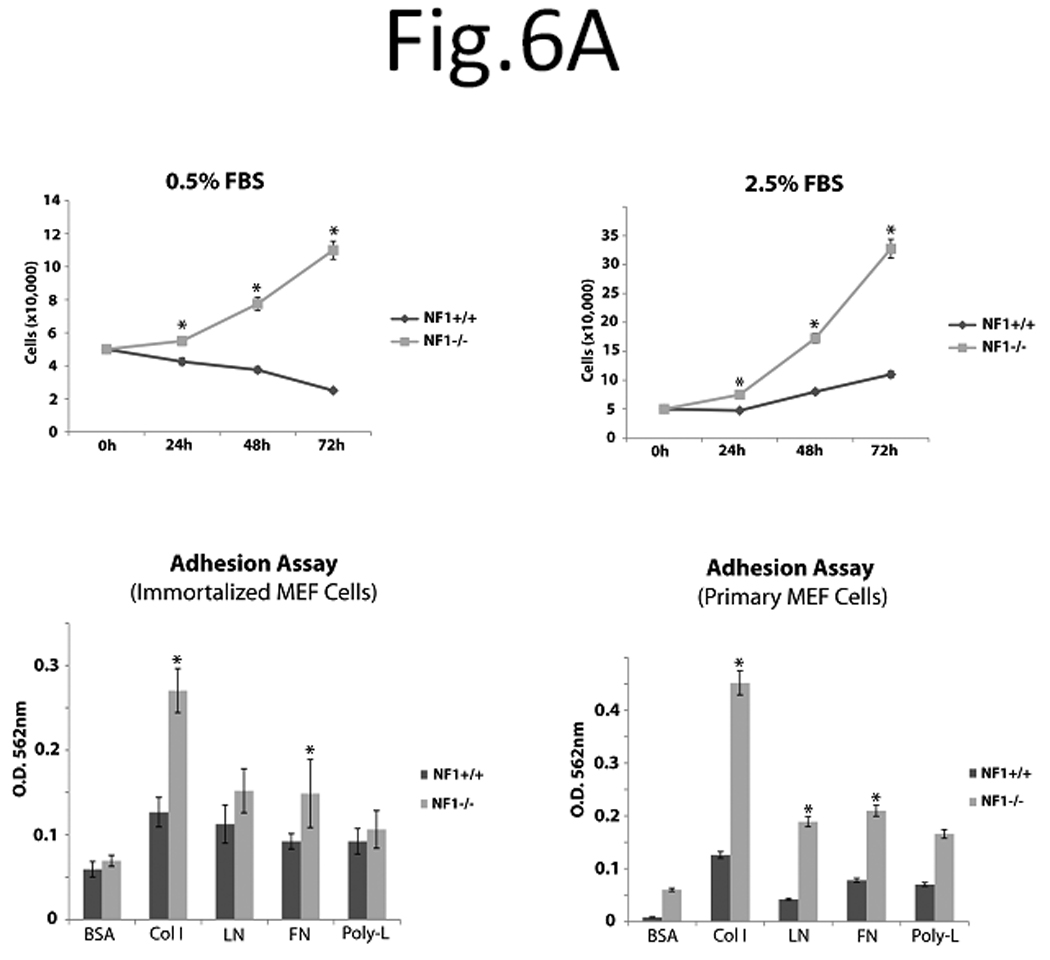

To characterize and compare Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells, we examined SV40 immortalized Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cell growth during nutrient deprivation. Cells were serum starved for 24h and then stimulated with 0.5% or 2.5% serum for 24, 48 and 72h (Figure 6A) There was significantly less growth in Nf1+/+ MEF cells stimulated with 0.5% serum (Figure 6A, upper left panel) or 2.5% serum (Figure 6A, upper right panel) compared to Nf1−/− MEF cells stimulated with the same serum (Figure 6A). The same results were obtained with normal primary MEF fibroblasts (not shown). Thus, neurofibromin significantly decreases cell growth in Nf1+/+ cells compared to Nf1−/− MEF cells during serum deprivation.

Figure 6.

Figure 6 A. Nf1+/+ MEF cells expressed significantly less cell growth at serum deprivation conditions and adhered less on Collagen I and Fibronectin compared with Nf1−/− MEF cells. SV40 Immortalized Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells were counted on hemocytometer at 0, 24, 48 and 72 hours after plating in medium with 0.5% FBS (upper left panel) or 2.5% FBS (upper right panel). Nf1+/+ MEF cells demonstrated significantly less cell growth at 0.5% and 2.5% serum versus Nf1−/− MEF cells. Lower left panel: Adhesion of SV40 immortalized Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells on BSA, Collagen I, Laminin, Fibronectin, and Poly-L lysine. SV40 immortalized Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells were plated on BSA, Collagen I, Fibronectin, Laminin and Poly-L-lysine-coated plates, and adhesion assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Immortalized Nf1+/+ cells had significantly less adhesion on Collagen I and Fibronectin than Nf1−/− cells. Lower right panel: Adhesion of normal primary Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells on BSA, Collagen I, Laminin, Fibronectin, and Poly-L lysine The same experiment as with immortalized MEF cells (above) was performed with primary MEF fibroblasts. Primary Nf1+/+ cells had significantly less adhesion than Nf1−/− cells.

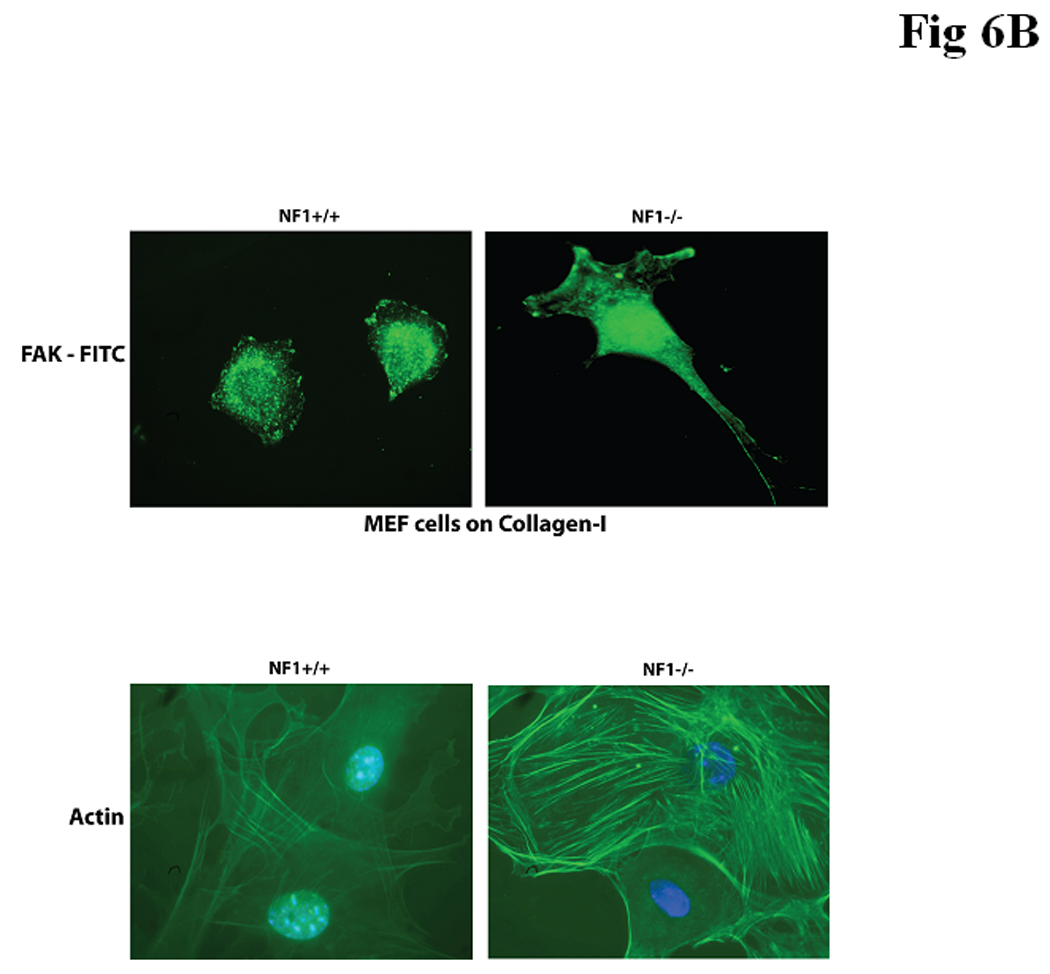

Figure 6B. FAK and actin staining in Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells. Upper panel. FAK immunostaining was performed on immortalized Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells, plated on Collagen I. Nf1−/− and Nf1+/+ MEF cells had different cell morphology and FAK localization. Nf1−/− cells had more elongated and more spread morphology and increased FAK staining at the leading edge of cells compared with less spread Nf1+/+ cells. Lower panel. Nf1−/− MEF cells expressed increased actin staining compared with Nf1+/+ cells. Actin staining was performed with FITC-conjugated Phallacidin. Actin staining was increased in Nf1−/− cells compared with Nf1+/+ MEF cells.

Because neurofibromin has been suggested to regulate focal adhesion formation [16], we examined the adhesion of SV40 immortalized Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF on Collagen-I, Laminin, Fibronectin and control poly-L-lysine or BSA (Figure 6A, lower left panel). Nf1+/+ MEF cells adhered significantly less than Nf1−/− MEF cells on Collagen-I and Fibronectin (Figure 6A, lower left panel). There was no significant difference on Laminin or control poly-L-lysine-treated plates (Figure 6A, lower left panel). The same results were obtained on normal primary MEF fibroblasts, where NF+/+ cells adhered significantly less than NF−/− cells (Figure 6A, lower right panel). There were also striking differences in the morphology and FAK staining in Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells on collagen (Figure 6B, upper panels). FAK was localized at the leading edge of elongated Nf1−/− cells with more spread morphology compared to Nf1+/+ MEF cells (Figure 6B, upper panels). In addition, Nf1+/+ MEF cells grown on Collagen-I displayed fewer actin stress fibers (Figure 6B, lower panels) than Nf1−/− MEF cells. Thus, Nf1+/+ MEF adhered less on Collagen I and Fibronectin compared to Nf1−/− cells, and expressed changes in FAK and actin distribution, suggesting the role of neurofibromin in cell adhesion and cytoskeletal and focal adhesion functions.

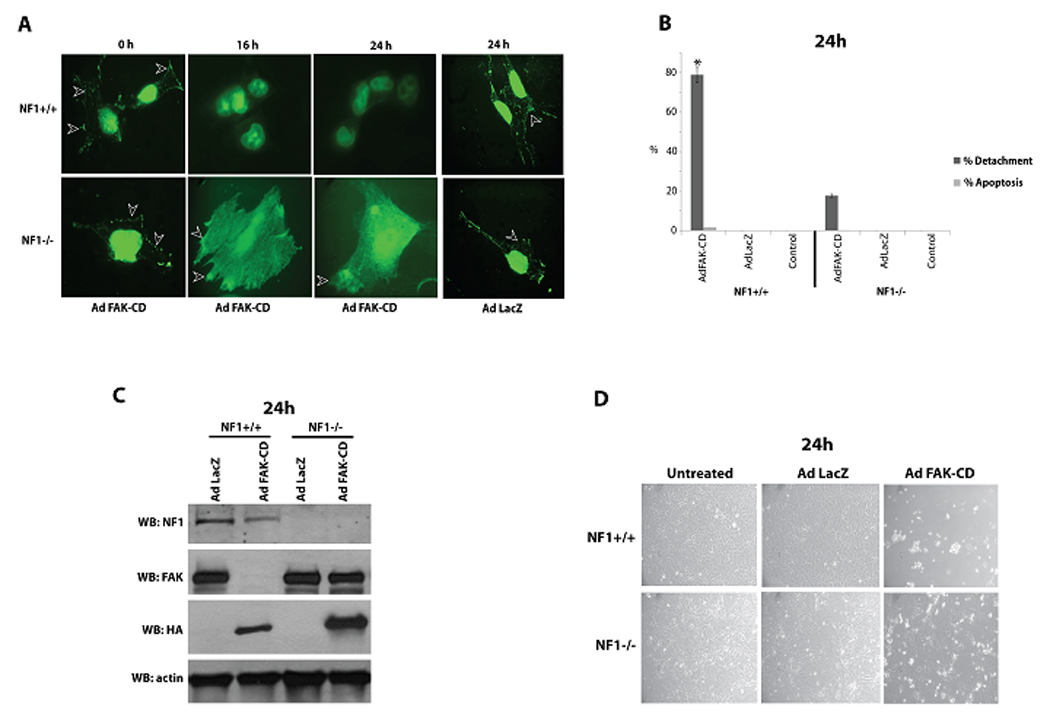

Dominant negative FAK inhibitor, FAK-CD causes significantly more detachment in Nf1+/+ MEF cells than in Nf1−/− MEF cells

To inhibit FAK signaling in both cell lines, we used our model system in which the trandsduction of an adenoviral C-terminal domain of FAK, FAK-CD (dominant-negative FAK inhibitor) into the cells causes inhibition of FAK and displacement of FAK from the focal adhesions [41]. We applied this model to test the effect of FAK attenuation on isogenic Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells (Figure 7). We studied focal adhesion formation of cells treated with Ad-FAK-CD for 16h and 24h (Figure 7A, upper panels). FAK was displaced by FAK-CD from focal adhesions in Nf1+/+ MEF cells at 16h and at 24h, but was not displaced from the focal adhesions in Nf1−/− MEF cells (Figure 7A, lower panels). No displacement of FAK from focal adhesion was detected with control Ad-LacZ at 24 h in both Nf1−/− and Nf1+/+ MEF cells (Figure 7A, right panels). Next, we looked at cell detachment and apoptosis induced by treatment with Ad-FAK-CD and control Ad-LacZ in Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells (Figure 7B). Nf1+/+ MEF cells showed significantly higher levels of detachment (78.9%) compared with Nf1−/− MEF cells (17.7%) after 24h treatment with Ad-FAK-CD (Figure 7B). No detachment was observed with control Ad-LacZ in both cell lines (Figure 7B). There was not significant level of Ad-FAK-CD-induced apoptosis in both Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells (Figure 7B). FAK-CD caused complete degradation of FAK in both Nf1+/+ MEF cells, while FAK was present in Nf1−/− MEF cells (Figure 7C). Control Ad-LacZ did not cause degradation of FAK compared with Ad-FAK-CD in Nf1+/+ cells (Figure 7C). Both cell lines showed efficient expression of HA-tagged FAK-CD, detected by Western blotting with HA-antibody (Figure 7C). Increased detachment and cell rounding was observed in Nf1+/+ cells compared with Nf1−/− MEF cells in response to Ad-FAK-CD are shown in Figure 7D. Thus, inhibition of FAK with FAKCD caused more detachment of Nf1+/+ MEF cells, suggesting that FAK inhibits neurofibromin functions critical for cytoskeletal and focal adhesion formation.

Figure 7.

A. Dominant-negative FAK inhibitor, Ad-FAK-CD causes displacement of FAK from focal adhesions in Nf1+/+ cells compared to Nf1−/− cells. Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells were infected with Ad FAK-CD (300 FFU/cell) and Ad LacZ for 16 h and 24 h and cells were immunostained with anti-FAK 4.47 antibody to analyze focal adhesion formation (white arrowheads). Ad FAK-CD displaced FAK from focal adhesions in Nf1+/+ MEF cells but not in Nf1−/− MEF cells at 16h and at 24h. No displacement of FAK from focal adhesion was detected with control Ad-LacZ at 16 h (not shown) and at 24 h. Focal adhesion marked by white arrowheads.

B. Detachment and apoptosis analysis of Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells treated for 24 h with Ad FAK-CD. Detachment and apoptosis were detected, as described in Materials and Methods. Nf1+/+ cells had significantly more detachment in response to Ad-FAK-CD than Nf1−/− MEF cells. C) FAK is displaced from focal adhesions by FAK-CD in Nf1+/+ cells compared with Nf1−/− cells. Western blotting analysis of Ad-LacZ and Ad-FAK-CD-treated Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells at 24 h. Western blotting with NF1, FAK, HA-tag and beta-Actin antibodies were performed. Western blotting with NF1 antibody shows NF1 expression in Nf1+/+ and absence in Nf1−/− cells. Ad-FAK-CD caused degradation of FAK in Nf1+/+ cells, while Ad-LacZ did not cause this effect on FAK. NF−/− cells did not have FAK degradation in response to Ad-FAK-CD. Western blotting with HA-tag antibody demonstrates that both cell lines effectively express HAtagged FAK-CD. Western blotting with beta-actin show equal protein loading. D) Images under microscope of Nf1+/+ and Nf1−/− MEF cells treated with Ad LacZ and Ad FAK-CD for 24 h. Ad-FAK-CD caused more detachment and cell rounding in Nf1+/+ cells compared with Nf1−/− MEF cells.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that neurofibromin is expressed in many types of cancers in addition to the cancer cells of nervous system. We demonstrated direct interaction between neurofibromin and Focal Adhesion Kinase. Using immunoprecipitation, we demonstrated association of FAK with neurofibromin in Nf1+/+ MEF cells and BT474 cancer cells. We also detected binding of neurofibromin and FAK in normal and tumor Schwann cells. We showed co-localization of neurofibromin and FAK in cytoplasm, perinuclear and nuclear regions. We demonstrated direct interaction between FAK and the C-terminal domain of neurofibromin in vitro. We also demonstrated interaction between neurofibromin and the N-terminal domain of FAK (FAK-NT). Interestingly, we performed phage display assay with the purified FAK-NT protein using a degenerate 7 amino acid phage library consisting of >2 ×109 sequences (New England Biolabs) and identified a 7 amino acid peptide with 71% (5 out of 7a.a.) homology to the nuclear localization sequence of neurofibromin that additionally supports our data on interaction of neurofibromin with the N-terminal domain of FAK (data not shown). Interestingly, the neurofibromin nuclear localization sequence (NF1-NLS) that is located in exon 43 (2534 – 2550a.a.) is present inside the cloned C-terminal fragment of neurofibromin that was used to demonstrate direct interaction with full length FAK. This neurofibromin fragment also contains a tyrosine kinase recognition site (2549 – 2556a.a.) next to the NF1-NLS, suggesting its potential role in intracellular functions and protein shuttling.

We showed that Nf1+/+ MEF cells have decreased cell growth under nutrient deprivation and that these cells adhered significantly less than Nf1−/− MEF cells on Collagen-I and Fibronectin. We also demonstrated that the dominant negative FAK protein, FAK-CD caused significant detachment and degradation of FAK in Nf1+/+ MEF cells but not in Nf1+/+ MEF cells. These results suggest that neurofibromin is important in cell adhesion and in modulating FAK survival signaling in the cell.

The N-terminal domain of FAK and FERM domain promote tumor cell proliferation and survival by binding to and enhancing p53 degradation in the nucleus [39]. It is interesting that FAK was only degraded by FAK-CD in the presence of neurofibromin in Nf1+/+ MEF cells, and that neurofibromin co-localizes with FAK around the nucleus. This may be a mechanism by which neurofibromin modulates FAK shuttling in to the nucleus and recruitment to the focal adhesions. By binding with FAK in the peri-nuclear region, neurofibromin may inhibit FAK transportation into the nucleus or recruitment to the focal adhesions or it may enhance FAK degradation via the ubiquitin-proteosome pathway that was recently reported to regulate neurofibromin levels in the cell [49].

The data demonstrating that Nf1+/+ cells adhered less to Collagen I and Fibronectin I than Nf1−/− cells and cells expressed differences in actin and FAK staining suggest that NF1 can regulate cytoskeletal reorganization consistent with data of Ozawa et al [16]. The authors demonstrated that neurofibromin affected cell adhesion and motility by reorganizing actin dynamics. NF1-depleted cells had increased focal adhesion, paxillin (focal adhesion protein and binding partner of FAK) staining and increased actin stress fiber formation compared with control cells [16]. We also showed that Nf1−/− cells had morphology of motile elongated cells with FAK distribution on the leading edge consistent with data on role of neurofibromin in motility [16]. The data show that NF1 and FAK complex can play role in cytoskeletal and focal adhesion functions.

Inhibition of FAK with FAK-CD demonstrated significantly higher detachment of Nf1+/+ cells, suggesting that FAK can sequester NF1 from growth inhibitory functioning, and once FAK is inhibited by FAK-CD, NF1 is released for cellular functioning. When FAK-CD expressed in the Nf1+/+ cells, FAK was displaced from focal adhesions and completely degraded, thus preventing formation of complex with NF1 protein and causing increased cell detachment. The data are consistent with our proposed model of FAK sequestering of pro-apoptotic proteins, such as RIP [36] and p53 [38], [50], suggesting a novel survival cellular mechanism in carcinogenesis, where FAK inhibits pro-apoptotic proteins in addition to integrating pro-survival signaling from integrins and growth factor receptors [50]. Interestingly, that Nf1−/− cells expressed increased resistance to down-regulation of FAK in response to Ad-FAK-CD that is important for developing FAK-targeted therapy.

Thus, in this report we have demonstrated an expression of neurofibromin in many types of cancer cells. We have shown a novel interaction of neurofibromin and FAK in vitro and in vivo, their co-localization and distribution inside the cells, and demonstrate that inhibition of FAK has differential effect on adhesion in Nf1−/− and Nf1+/+ cells, suggesting that FAK and NF1 interaction can play significant role in the intracellular signaling and carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by Susan Komen for the Cure grant BCTR0707148(V.M.G.) and NIH grant CA65910 (W.G.C.).

Abbreviations

- FAK

Focal Adhesion Kinase

- FAK-CD

C-terminal domain of FAK

- NF1

Neurofibromin

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- R.T.

room temperature

References

- 1.Gutmann DH, Wood DL, Collins FS. Identification of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9658–9662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace MR, Marchuk DA, Andersen LB, et al. Type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: identification of a large transcript disrupted in three NF1 patients. Science. 1990;249:181–189. doi: 10.1126/science.2134734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchuk DA, Saulino AM, Tavakkol R, et al. cDNA cloning of the type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: complete sequence of the NF1 gene product. Genomics. 1991;11:931–940. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daston MM, Scrable H, Nordlund M, Sturbaum AK, Nissen LM, Ratner N. The protein product of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene is expressed at highest abundance in neurons, Schwann cells, and oligodendrocytes. Neuron. 1992;8:415–428. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90270-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheffzek K, Ahmadian MR, Wiesmuller L, et al. Structural analysis of the GAP-related domain from neurofibromin and its implications. EMBO J. 1998;17:4313–4327. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guran S, Safali M. A case of neurofibromatosis and breast cancer: loss of heterozygosity of NF1 in breast cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;156:86–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez L, Rubio MP, Martin MT, et al. Chromosome 17 allelic loss and NF1-GRD mutations do not play a significant role as molecular mechanisms leading to melanoma tumorigenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:432–436. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12343578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogata H, Sato H, Takatsuka J, De Luca LM. Human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells fail to express the neurofibromin protein, lack its type I mRNA isoform and show accumulation of P-MAPK and activated Ras. Cancer Lett. 2001;172:159–164. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson MR, Look AT, DeClue JE, Valentine MB, Lowy DR. Inactivation of the NF1 gene in human melanoma and neuroblastoma cell lines without impaired regulation of GTP. Ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5539–5543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen LB, Fountain JW, Gutmann DH, et al. Mutations in the neurofibromatosis 1 gene in sporadic malignant melanoma cell lines. Nat Genet. 1993;3:118–121. doi: 10.1038/ng0293-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johannessen CM, Reczek EE, James MF, Brems H, Legius E, Cichowski K. The NF1 tumor suppressor critically regulates TSC2 and mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8573–8578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503224102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapira S, Barkan B, Friedman E, Fridman E, Kloog Y, Stein R. The tumor suppressor neurofibromin confers sensitivity to apoptosis by Ras-dependent and Ras-independent pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:895–906. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandenbroucke I, Van Oostveldt P, Coene E, De Paepe A, Messiaen L. Neurofibromin is actively transported to the nucleus. FEBS Lett. 2004;560:98–102. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00078-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyanapalli M, Lahoud OB, Messiaen L, et al. Neurofibromin binds to caveolin-1 and regulates ras, FAK, and Akt. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:1200–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregory PE, Gutmann DH, Mitchell A, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product (neurofibromin) associates with microtubules. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1993;19:265–274. doi: 10.1007/BF01233074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozawa T, Araki N, Yunoue S, et al. The Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Gene Product Neurofibromin Enhances Cell Motility by Regulating Actin Filament Dynamics via the Rho-ROCK-LIMK2-Cofilin Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang FC, Ingram DA, Chen S, et al. Neurofibromin-deficient Schwann cells secrete a potent migratory stimulus for Nf1+/− mast cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1851–1861. doi: 10.1172/JCI19195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agochiya M, Brunton VG, Owens DW, et al. Increased dosage and amplification of the focal adhesion kinase gene in human cancer cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:5646–5643. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiedorek FT, Jr, Kay ES. Mapping of the focal adhesion kinase (Fadk) gene to mouse chromosome 15 and human chromosome 8. Mammalian Genome. 1995;6:123–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00303256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabarra-Niecko V, Schaller MD, Dunty JM. FAK regulates biological processes important for the pathogenesis of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:359–374. doi: 10.1023/a:1023725029589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanks SK, Calalb MB, Harper MC, Patel SK. Focal adhesion protein-tyrosine kinase phosphorylated in response to cell attachment to fibronectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8487–8491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanks SK, Polte TR. Signaling through focal adhesion kinase. Bioessays. 1997;19:137–145. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaller MD, Borgman CA, Cobb BS, Vines RR, Reynolds AB, Parsons JT. pp125fak a structurally distinctive protein-tyrosine kinase associated with focal adhesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5192–5196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zachary I. Focal adhesion kinase. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:929–934. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cance WG, Harris JE, Iacocca MV, et al. Immunohistochemical analyses of focal adhesion kinase expression in benign and malignant human breast and colon tissues: correlation with preinvasive and invasive phenotypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2417–2423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owens LV, Xu L, Craven RJ, et al. Overexpression of the focal adhesion kinase (p125FAK) in invasive human tumors. Cancer Research. 1995;55:2752–2755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens LV, Xu L, Dent GA, et al. Focal adhesion kinase as a marker of invasive potential in differentiated human thyroid cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 1996;3:100–105. doi: 10.1007/BF02409059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiner TM, Liu ET, Craven RJ, Cance WG. Expression of focal adhesion kinase gene and invasive cancer. Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1024–1025. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92881-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiner TM, Liu ET, Craven RJ, Cance WG. Expression of growth factor receptors, the focal adhesion kinase, and other tyrosine kinases in human soft tissue tumors. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 1994;1:18–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02303537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lightfoot HM, Jr, Lark A, Livasy CA, et al. Upregulation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) expression in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is an early event in breast tumorigenesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;88:109–116. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-1022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cobb BS, Schaller MD, Leu TH, Parsons JT. Stable association of pp60src and pp59fyn with the focal adhesion-associated protein tyrosine kinase, pp125FAK. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:147–155. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hildebrand JD, Schaller MD, Parsons JT. Paxillin, a tyrosine phosphorylated focal adhesion-associated protein binds to the carboxyl terminal domain of focal adhesion kinase. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1995;6:637–647. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golubovskaya V, Beviglia L, Xu LH, Earp HS, 3rd, Craven R, Cance W. Dual inhibition of focal adhesion kinase and epidermal growth factor receptor pathways cooperatively induces death receptor-mediated apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38978–38987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sieg DJ, Hauck CR, Ilic D, et al. FAK integrates growth-factor and integrin signals to promote cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:249–256. doi: 10.1038/35010517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaller MD, Otey CA, Hildebrand JD, Parsons JT. Focal adhesion kinase and paxillin bind to peptides mimicking beta integrin cytoplasmic domains. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1181–1187. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurenova E, Xu L-H, Yang X, et al. Focal Adhesion Kinase Suppresses Apoptosis by Binding to the Death Domain of Receptor-Interacting Protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4361–4371. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4361-4371.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kadare G, Toutant M, Formstecher E, et al. PIAS1-mediated sumoylation of focal adhesion kinase activates its autophosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47434–47440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golubovskaya VM, Finch R, Cance WG. Direct interaction of the N-terminal domain of focal adhesion kinase with the N-terminal transactivation domain of p53. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25008–25021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim ST, Chen XL, Lim Y, et al. Nuclear FAK promotes cell proliferation and survival through FERM-enhanced p53 degradation. Mol Cell. 2008;29:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu J, Zutter MM, Santoro SA, Clark RA. A three-dimensional collagen lattice activates NF-kappaB in human fibroblasts: role in integrin alpha2 gene expression and tissue remodeling. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:709–719. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu L-h, Yang X-h, Bradham CA, et al. The focal adhesion kinase suppresses transformation-associated, anchorage-Independent apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30597–30604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910027199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hauck CR, Hunter T, Schlaepfer DD. The v-Src SH3 domain facilitates a cell adhesion-independent association with focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17653–17662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ilic D, Almeida EA, Schlaepfer DD, Dazin P, Aizawa S, Damsky CH. Extracellular matrix survival signals transduced by focal adhesion kinase suppress p53-mediated apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:547–560. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones G, Machado J, Jr, Tolnay M, Merlo A. PTEN-independent induction of caspase-mediated cell death and reduced invasion by the focal adhesion targeting domain (FAT) in human astrocytic brain tumors which highly express focal adhesion kinase (FAK) Cancer Res. 2001;61:5688–5691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu LH, Owens LV, Sturge GC, et al. Attenuation of the expression of the focal adhesion kinase induces apoptosis in tumor cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:413–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frisch SM, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E, Chan-Hui PY. Control of adhesion-dependent cell survival by focal adhesion kinase. Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;134:793–799. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsueh YP, Roberts AM, Volta M, Sheng M, Roberts RG. Bipartite interaction between neurofibromatosis type I protein (neurofibromin) and syndecan transmembrane heparin sulfate proteoglycans. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3764–3770. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03764.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng L, Yunoue S, Tokuo H, et al. PKA phosphorylation and 14-3-3 interaction regulate the function of neurofibromatosis type I tumor suppressor, neurofibromin. FEBS Lett. 2004;557:275–282. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cichowski K, Santiago S, Jardim M, Johnson BW, Jacks T. Dynamic regulation of the Ras pathway via proteolysis of the NF1 tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2003;17:449–454. doi: 10.1101/gad.1054703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cance WG, Golubovskaya VM. Focal adhesion kinase versus p53: apoptosis or survival? Sci Signal. 2008;1(20):pe22. doi: 10.1126/stke.120pe22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]