Abstract

Lineage survival oncogenes are activated by somatic DNA alterations in cancers arising from the cell lineages in which these genes play a role in normal development.1,2 Here we show that a peak of genomic amplification on chromosome 3q26.33, found in squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) of the lung and esophagus, contains the transcription factor gene SOX2—which is mutated in hereditary human esophageal malformations3 and necessary for normal esophageal squamous development4, promotes differentiation and proliferation of basal tracheal cells5 and co-operates in induction of pluripotent stem cells.6,7,8 SOX2 expression is required for proliferation and anchorage-independent growth of lung and esophageal cell lines, as shown by RNA interference experiments. Furthermore, ectopic expression of SOX2 cooperated with FOXE1 or FGFR2 to transform immortalized tracheobronchial epithelial cells. SOX2-driven tumors show expression of markers of both squamous differentiation and pluripotency. These observations identify SOX2 as a novel lineage survival oncogene in lung and esophageal SCC.

To identify genomic aberrations in lung and esophageal SCCs, we determined copy number for 40 esophageal SCC DNA samples (29 primary tumors and 11 cell lines) and 47 primary lung SCC DNA samples using 250K Sty I Affymetrix single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays. Data were analyzed using GISTIC (Genomic Identification of Significant Targets in Cancer)1,9, which scores the significance of recurrent gains or losses and identifies peak regions likely to contain the driver gene(s).

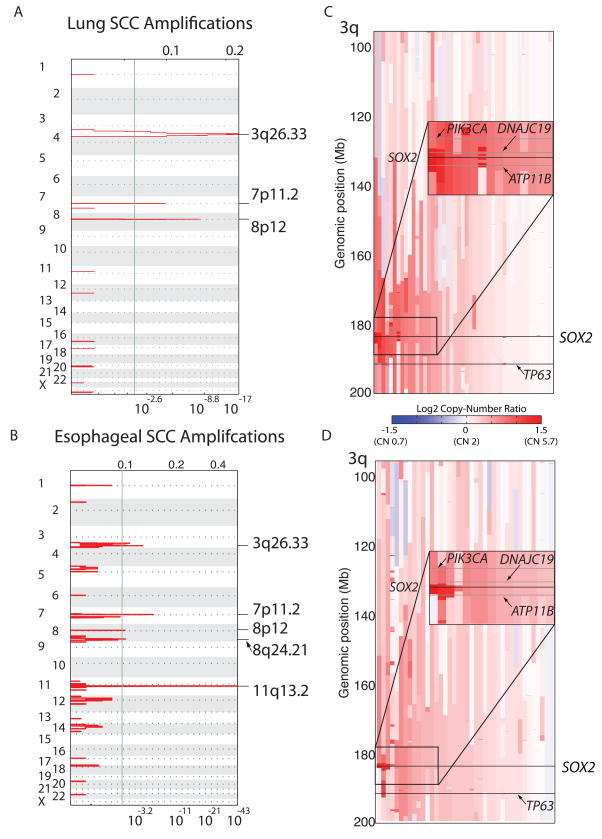

For lung SCC, the most significant amplification peak is located on chromosome segment 3q26.33, with the next most significant peaks encompassing the tyrosine kinase genes EGFR on 7p11.2 and FGFR1 on 8p12 (Figure 1a; Table 1; Supplemental Table 1). In esophageal SCC, the most significant amplification peak spans the cyclin gene CCND1 on 11q13.2; additional amplifications are found at EGFR, FGFR1, chromosome segment 3q26.33 and on 8q24.21 near MYC and POU5F1B (Figure 1b; Table 1; Supplemental Table 1). Significant focal deletions including deletions of CDKN2A/B on 9p21.3 were also identified (Supplemental Table 1; Supplemental Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Recurrent genomic amplifications of 3q target SOX2 in lung and esophageal squamous cell carcinomas.

A) Plots of recurrent high-level amplifications in 47 SCCs of the lung from GISTIC analysis of SNP array data. X-axis shows the G-score (top) and false discovery rate (q-value; bottom) for recurrent amplification across the genome with a green line demarcating an arbitrary FDR cut-off of 0.005. Labels on right denote the position of peaks of the most significantly altered regions. B) Depiction of GISTIC amplification peaks for 40 esophageal squamous cell carcinomas (29 primary tumors and 11 cell lines) C) Plot of copy-number data from chromosome 3q from lung SCC. Each sample is represented with a vertical line from centromere (top) to telomere (bottom). Areas of red indicate gain; blue indicates loss. The positions of SOX2 and TP63 are noted with horizontal lines. An inset box shows the 10-Mb region centered on SOX2 in greater detail in the 15 samples with highest SOX2 copy number. The grey lines depict the positions of the two nearest RefSeq genes to SOX2--ATP11B and DNAJC19--as well as PIK3CA. D) Plot of copy-number on chromosome 3q in esophageal SCC as described for panel C.

Table 1.

High-level amplifications in lung and esophageal squamous cell carcinomas

| Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma Amplifications | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoband | q value | Peak Boundaries | Genes in Peak | Candidate Target(s) |

| 3q26.33 | 4.8E-21 | 182.29–184.44 | 4 | SOX2 |

| 8p12 | 1.5E-07 | 38.25–39.72 | 10 | FGFR1, WHSC1L1 |

| 7p11.2 | 5.2E-06 | 54.31–55.74 | 7 | EGFR |

| Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Amplifications | ||||

| Cytoband | q value | Peak Boundaries | Genes in Peak | Candidate Target(s) |

| 11q13.3 | 4.1E-41 | 68.81–69.94 | 10 | CCND1 |

| 7p11.2 | 6.3E-06 | 54.60–55.36 | 2 | EGFR |

| 3q26.33 | 6.0E-06 | 182.71–183.93 | 1 | SOX2 |

| 8q24.21 | 0.003 | 128.35–128.70 | 2 | MYC, POU5F1B |

| 8p12 | 0.003 | 38.23–38.76 | 6 | FGFR1, WHSC1L1, PPADC1B |

GISTIC-defined peaks of high-level (inferred copy-number >3.6) recurrent genomic amplification in lung squamous cell carcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Chromosome segment 3q26.33 is amplified in 11 of the 47 (23%) lung and 6 of the 40 (15%) esophageal SCCs analyzed, as defined by SNP array-derived copy number of 3.6 or greater, which is generally a significant underestimate due to high tumor ploidy, normal DNA admixture, or signal saturation at high copy number. As five of the six amplified esophageal SCCs cases were cell lines, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on tissue microarrays (TMA) from 63 independent primary esophageal SCC samples and noted amplifications in 7 of 63 cases to confirm recurrent amplifications in primary tumors (data not shown).

The peaks on chromosome segment 3q26.33 occur within a previously defined focus of amplification within 3q26-3q28 in SCCs10,11 containing candidate oncogenes including TP63,12 PIK3CA13 and DCUN1D1.14 In our lung SCC analysis, the peak contains four genes (SOX2, ATP11B, DCUN1D1, and MCCC1) (Figure 1c; Table 1). In esophageal SCC, the 3q amplification peak includes only one annotated gene, SOX2 (Figure 1d; Table 1). Even for those samples with the highest copy number at PIK3CA and TP63, SOX2 is amplified to higher levels in the majority of these samples (Supplemental Figure 1b). While these results argue that SOX2 is a target of amplification, the absence of other genes from a GISTIC peak does not exclude an oncogenic role, nor does it exclude polygenic contributions. Indeed, one lung SCC sample did harbor higher amplification at DCUN1D1/ATP11B than at SOX2 (Supplemental Figure 1b), and also one lung SCC sample showed amplification at 183.03–183.27 Mb on chromosome 3, syntenic to the region containing lincRNA-Sox2, a non-coding RNA identified as a target of Sox2 in mouse ES cells.15

To evaluate the impact of 3q26.33 amplification on SOX2 expression, we measured SOX2 mRNA levels by quantitative RT-PCR in 27 lung SCCs for which matched SNP array data and RNA were available. Cases with SOX2 amplification had higher mRNA expression (p-value= 0.001; Supplemental Figure 2a–b). We noted several cases without 3q26.33 amplification with high SOX2 mRNA expression, suggesting that mechanisms other than amplification also can induce SOX2 overexpression. For esophageal SCC, we also documented the correlation of amplification and expression using immunohistochemistry and FISH on matched TMAs (Supplemental Figure 2c).

We next evaluated the essentiality of genes within and near the amplification peak at 3q26.33 for SCC cell lines bearing the amplification. We performed an arrayed RNAi screen targeting SOX2, ten neighboring genes, two additional candidates (PIK3CA and TP63) and control short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) specific for GFP and LacZ (Supplemental Table 2). Three to ten independent shRNAs were tested and analyzed after introduction into four SCC cell lines (esophageal lines TE10 and TT and lung lines NCI-H520 and HCC95) that harbor 3q26.33 amplification and two control lung adenocarcinoma cell lines that lack 3q26.33 amplification, NCI-H1437 and NCI-H1355.

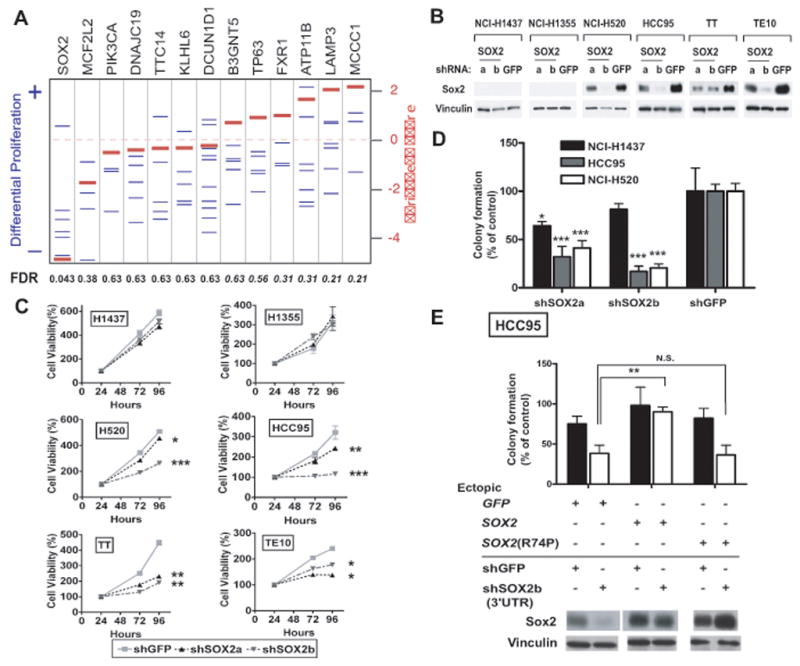

Each shRNA construct was evaluated for its differential impact on proliferation, comparing its effect on the four amplified SCC lines to the two control cell lines. Expression of several independent shRNAs targeting SOX2 reduced proliferation of the SCC cell lines compared to their effects in controls (Figure 2a). Analysis with the RIGER16,17 algorithm shows that suppression of SOX2 has the largest differential anti-proliferative effects on the 3q26.33 amplified SCC cell lines among all genes tested (Figure 2a). Since prior work had implicated DCUN1D1 as a potential transforming oncogene14 we further validated the results of shRNA constructs targeting this gene and noted consistently less effect for knockdown of this gene relative to SOX2 (Supplemental Note; Supplemental Figure 3a–b). These observations suggest that SOX2 is an essential gene in SCCs with 3q26.33 amplifications.

Figure 2. SOX2 knockdown via RNAi reduces anchorage-independent growth and proliferation of SOX2-overexpressing cell lines.

A) RIGER analysis of shRNA against SOX2 and genes neighboring SOX2. Differential effects of each shRNA construct on proliferation of the four 3q26.33-amplified SCC cell lines was calculated by comparison of the effect of each shRNA construct in the SCC cell lines compared to the construct’s effect in two control lung adenocarcinoma cell lines. Blue lines represent differential proliferation scores for each shRNA construct. Negative enrichment scores represent reduced proliferation in the four SCC cell lines. Red lines represent the normalized enrichment score calculated for each gene based upon the proliferative effect of all shRNAs to that gene compared to effects of other shRNAs in this screen. False discovery rates (FDRs) for significant enrichment are listed below the graph; FDRs for SCC cell-specific reduced proliferation are shown in plain text and for control cell-specific reduced proliferation in italics. All results were normalized against the effects of control shRNAs (shGFP, shLacZ) in each cell line. B)Anti-Sox2 and control anti-vinculin immunoblots of lysates from established tumor cell lines stably expressing shRNA targeting SOX2 (shSOX2a or shSOX2b) or shRNA specific for green fluorescent protein (shGFP). HCC95 and NCI-H520 are lung SCC lines; TT and TE10 are esophageal SCC cell lines; and NCI-H1437 and NCI-H1355 are lung adenocarcinoma cell lines used as controls. C)Effect of SOX2-specific shRNA on viable cell numbers over time. Cells were measured at 24, 72 and 96 hours after plating and corrected to equalize 24-hr values. Mean cell viabilities (+/- standard deviations of cell plated in quadruplicate) are plotted as percentage of 24-hour measurement at 24, 72 and 96 hours after plating. (Note, due to low standard deviations of some measurements, error bars are not visible for all data points.) Significance levels are indicated with * marking p<0.05, ** for p<0.01 and *** for p<0.001. D)Soft agar colony formation for HCC95 and NCI-H520 and control NCI-H1437 cells expressing SOX2 shRNA is shown relative to shGFP (+/− standard deviation) with p-values marked as above. E) Soft agar colony formation for HCC95 cells engineered with ectopic expression of GFP, SOX2 or SOX2 R74P followed by infection with shSOX2b or shGFP. Data are shown relative to shGFP in HCC95-GFP cells (+/− standard deviation) with p-values marked as above. Immunoblots for Sox2 and vinculin are shown.

To determine in more detail the requirement for amplified SOX2, we examined cell lines expressing SOX2-directed or control shRNAs (shSOX2a, shSOX2b and shGFP) (Figure 2b). Suppression of SOX2 with either of two shRNA constructs reduced proliferation in the four 3q26.33-amplified lines but not in controls without appreciable Sox2 expression (Figure 2c). We next evaluated anchorage-independent growth. TE10, TT and NCI-H1355 were not tested as these cell lines fail to form colonies in soft agar. ShRNA targeting SOX2 decreases colony formation in SOX2-amplified HCC95 and NCI-H520 cells compared to NCI-H1437 cells (Figure 2d). Further results suggest that the reduction in anchorage-independence upon SOX2 knockdown exceeds the reduction in proliferation and that SOX2 is essential for some tumor cells with lower-level copy-gain at 3q26.33 (Supplemental Note; Supplemental Figure 3c–d).

To confirm that the effects of SOX2 shRNA are attributable to SOX2 suppression, we tested whether we could rescue the effects of suppression of SOX2 with ectopic wild-type SOX2 or SOX2 R74P, a loss-of-function DNA-binding domain mutant identified in a patient with congenital tracheoesophageal fistula3. We introduced wild-type and mutant SOX2 into HCC95 cells and subsequently introduced shSOX2b, which targets the SOX2 3′ UTR. Expression of wild-type SOX2 restored anchorage-independent growth, whereas SOX2 R74P or GFP control failed to do so (Figure 2e). These observations demonstrate a clear requirement for SOX2 and argue against the possibility that the effects of shSOX2b on HCC95 cells are due to off-target toxicity.

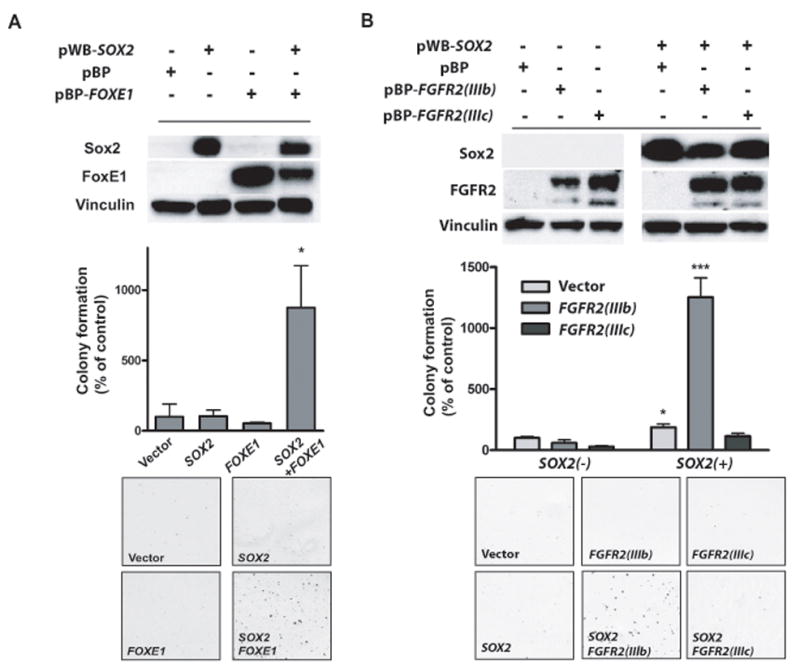

We next examined the ability of SOX2 to transform immortalized tracheobronchial epithelial (AALE) cells.18 As SOX2 alone was not transforming, we searched lung SCC expression data19 for genes whose expression correlates with SOX2 expression (Supplemental Table 3) as candidates for co-operative transformation. The most highly correlated gene is FOXE1, a forkhead transcription factor gene on chromosome 9q22.33, which is also the locus of the most significant germ-line risk allele for thyroid cancer (followed by the NKX2-1 locus).20 FOXE1 is expressed in the epithelium of the developing esophagus,21 and congenital mutations cause cleft palate and hypothyroidism.22 Another highly correlated gene, the receptor tyrosine kinase gene FGFR2, was of particular interest given that activating mutations are observed in lung SCC.23

While neither SOX2 nor FOXE1 ectopic expression alone was transforming, their co-expression induced anchorage-independent growth (Figure 3a). However, we were unable to demonstrate a stable physical interaction of Sox2 and FoxE1 with co-immunoprecipitation (data not shown), the suppression of FOXE1 with RNAi failed to reduce proliferation of SCC cell lines, and FoxE1 protein was not appreciably expressed in all SOX2-dependent SCC lines (data not shown), suggesting that FOXE1 is not broadly required for SOX2 function.

Figure 3. SOX2 can transform FOXE1- or FGFR2IIIb-expressing immortalized tracheobronchial epithelial cells.

A) Soft agar colony formation for AALE tracheobronchial epithelial cells expressing either SOX2, FOXE1 or the combination of factors. Graph shows number of colonies (+/− standard deviation of experiment) with p-values labeled with asterisks as in Figure 2. Also pictured are representative soft-agar images and immunoblots showing expression of Sox2 and FoxE1. B) Soft agar colony formation data (+/− standard deviations), immunoblots and representative soft-agar images from co-transformation assays in AALE cells with SOX2 and FGFR2 IIIb and FGFR2 IIIc ectopic expression.

To investigate potential cooperation between SOX2 and FGFR2, we similarly generated stable AALE lines by ectopic expression of SOX2, wild-type FGFR2 in the IIIb or IIIc splice variants, or both genes. Neither SOX2 nor FGFR2 expression alone could transform AALE cells, but the combination of SOX2 with the FGFR2 IIIb isoform found in epithelial cancers promoted anchorage-independent growth (Figure 3b). In contrast, expression of the ‘mesenchymal’ isoform IIIc failed to transform these cells with SOX2 (Figure 3b). These results demonstrate that SOX2 can be transforming with multiple cooperating genes. Further work will be required to elaborate the genes which can act with SOX2 in tumorigenesis and the subtypes of tumors in which these genes are active.

In prior reports, we and others have identified that the developmental transcription factor NKX2-1 (or TITF1) is an amplified lineage survival oncogene in lung adenocarcinoma.1,24,25,26 Within the primitive foregut there is reciprocal expression of Nkx2.1 and Sox2 in compartments that form the trachea and esophagus, respectively.4 Experimentally, Nkx2.1−/− mice form hypoplastic lungs that stem from an undivided foregut with Sox2+/p63+ squamous epithelium.4 By contrast, mice that express a hypomorphic Sox2 allele develop tracheoesophageal fistulae and form an esophagus with a ciliated Nkx2.1+/p63− mucosa.4 Hypothesizing that SOX2 may similarly represent a lineage survival oncogene, we compared the expression and amplification patterns of these two genes between lung adenocarcinomas and SCCs. We found SOX2 amplifications to be enriched in the lung SCC tumor population, while NKX2-1 amplification was enriched in lung adenocarcinoma (Supplemental Figure 4a–b), consistent with a previous study of NKX2-124 and with a report that the copy-number of lung adenocarcinoma and SCC are distinguished by SCC-specific amplification chromosome 3q at 180–200 Mb.27 SNP array analysis from multiple adenocarcinoma lineages including esophageal adenocarcinomas failed to identify significant SOX2 amplification (Beroukhim et al; submitted). Furthermore, mRNA expression data19,28 show that SOX2 mRNA levels are significantly higher in the lung SCC population compared to adenocarcinomas while NKX2-1 expression is significantly higher in adenocarcinomas (Supplemental Figure 4c–d). The complementary roles of SOX2 and NKX2-1 in distinct cancer lineages thus parallel their actions in development.

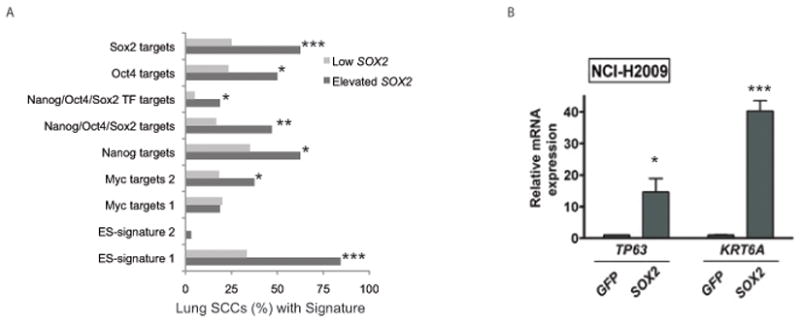

In addition to its role in the development and maintenance of esophageal and tracheal tissues, SOX2 is also a key factor in pluripotency and one of the factors that allows reprogramming of mature cells to pluripotent stem cells.6,7,8 Although the lineage-restricted nature of SOX2 amplifications in lung and esophageal SCC argues for a role as a lineage survival oncogene, we sought to determine how SOX2’s role as a pluripotency factor could contribute to its oncogenic activity. Expression analysis across other tumor lineages has identified signatures of embryonic stem cells (ES cells) in subsets of tumors; these tumors tend to be poorly differentiated and associated with decreased survival.29 Querying lung SCC expression data with these signatures, we noted ES-like signatures and expression of targets of the core ES transcription factors in tumors with higher SOX2 expression (Figure 4a). However, patients presenting with lung SCC tumors exhibiting the ES-signature had improved survival compared to those without the signature (p-value for Kaplan-Meier plot 0.03; not shown), and we did not identify significant association of SOX2 amplification or expression with clinical grade.

Figure 4. SOX2 induces expression of markers of both pluripotency and squamous differentiation.

A) The percentages of lung SCC tumors showing over-expression of each of nine gene sets that are characteristically induced in ES cells are shown for samples with and without elevated SOX2 expression. Gene sets for which the FDR-corrected hypergeometric enrichment P-value for the differences in over-expression in cases with and without SOX2 over-expression are marked as in Figure 2. B) Quantitative RT-PCR for mRNA expression of squamous markers TP63 and KRT6A in NCI-H2009 cells with ectopic SOX2 compared to ectopic GFP with asterisks indicating p-values.

In contrast, expression of SOX2 correlates with markers of squamous differentiation in lung SCCs. TP63 and KRT6A, which encode for the squamous markers p63 and cytokeratin 6A, respectively, were among the 50 transcripts most correlated with SOX2 expression in lung SCCs (Supplemental Table 3). When SOX2 was ectopically expressed in the lung adenocarcinoma line NCI-H2009, both TP63 and KRT6A were induced (Figure 4b), demonstrating actions of SOX2 that promote squamous identity rather than de-differentiation to a pluripotent state, thus consistent with a role as a lineage survival oncogene.

This is the first report to show that SOX2 is an amplified oncogene in lung or esophageal SCC. SOX2 has critical roles in foregut development where it regulates initial dorsal/ventral patterning4, shapes epithelial-mesenchymal interactions and is required for proper differentiation of both the squamous esophagus4 and of multiple respiratory cell types.5 SOX2 retains essential functions in the adult foregut where it is expressed in the proliferative basal esophagus30 and in the putative tracheal and airway stem cells5,31 where SOX2 is necessary for proliferation and response to injury.5 SOX2-driven SCCs likely co-opt multiple functions regulated by SOX2 in the normal foregut and may activate additional pathways controlled by SOX2 in early pluripotent cells. Given the complexity of these functions and the involvement of interactions of multiple cell types, further study of the oncogenic function of SOX2 will require engineered animal and organotypic tissue culture models. The elucidation of SOX2-dependent pathways in these models may identify novel therapeutic vulnerabilities in SCC and may uncover additional common pathways between cancer, normal development and the maintenance of pluripotency.

METHODS

Tumor Samples

DNA was provided for 47 lung SCC tumors with 17 matched normal samples (M.S.T, L.R.C., M.S.B and K.K.W), 29 esophageal SCCs and 11 matched normal samples (H.N., D.B.S, I.C., U.R.Jr., S.K.M. and A.K.R), and 11 esophageal SCC cell lines (A.K.R). Clinical information is listed in Supplemental Table 1. Primary tumors were all fresh-frozen with efforts to use samples with tumor content >70%. Tissue microarrays (TMAs) of esophageal SCC were provided by H.N., D.B.S and A.K.R..

SNP Array Experiments and Analysis

DNA was genotyped using the Sty I chip of the 500K Human Mapping Arrays (Affymetrix Inc).1 Data were analyzed using GISTIC.1,9 Copy number estimates were obtained using a tangent normalization, in which tumor signal intensities are divided by signal intensities from the linear combination of normal samples that are most similar to the tumor (manuscript describing methodology in preparation). After data normalization and segmentation/smoothing, GISTIC scores each SNP locus (G-score) as the product of frequency and mean amplitude of amplifications. Only amplifications exceeding log2 copy number ratio of 0.848 above diploid for amplifications or of 0.737 below diploid for deletions were included as has been standard in copy-number analyses with SNP arrays.1 This copy-number threshold for amplifications is lower than what is conventionally used to score FISH as done below. SNP array copy-numbers are diminished due to admixture of DNA from normal tissue and from microarray probe saturation effects leading to attenuation of inferred copy-number. G-scores were compared against a null model to determine a false discovery rate (q-value). Peaks with q-values below 0.005 were considered. Genomic coordinates of peaks of amplification were identified after capping copy number estimates at a log2 value of 1.0 to minimize peak calling due to hyper-segmentation; peak-finding also employed a peel-off step to remove the peak borders defined by the single sample(s) responsible for the minimal common regions. Genomic positions are mapped the hg18 genome build.

Two-Color Interphase FISH Assay

Probes for SOX2 (clone CTD-2348H10) and reference (clone RP11-286G5) were obtained from the BACPAC Resource Center (Oakland, CA) and also from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Tissue hybridization, washing, and color detection were performed as described previously.32 The samples were analyzed under a 60x oil immersion objective using an Olympus BX-51 fluorescence microscope, and the CytoVision FISH imaging and capturing software (Applied Imaging, San Jose, CA). Semi-quantitative evaluation of the assays was independently performed by three evaluators (S.P., C.J.L. and P.W.). Samples were called as high-level amplification if ten or more inferred copies of SOX2 were detected.

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

AALE cells were generated as previously described.18 HCC95, NCI-H1355, NCI-H2009 and NCI-H1437 were provided by J.D.M. NCI-H520 cells were purchased from ATCC. TT, TE10 and TE11 cell lines were provided by A.K.R.. Lung cancer cell lines were maintained in RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum. Esophageal SCC lines were maintained in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum. AALE cells were grown in SAGM media (Lonza). NIH-3T3 cells (ATCC) were grown in DMEM with 10% calf serum. All cells were grown in 1mM penicillin/streptomycin cells other than AALE’s also were grown with 2mM L-Glutamine.

RNAi Screen

Lentiviral vectors containing shRNA sequences were obtained from the RNAi Consortium (TRC) (http://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai/trc; Supplemental Table 2). For three genes, FXR1, MCCC1 and PIK3CA, the TRC had performed knockdown validation; for these genes the three top-scoring constructs were used. For the remaining 10 genes (SOX2, MCF2L2, DNAJC19, TTC14, KLHL6, DCUN1D1, B3GNT5, TP63, ATP11B, LAMP3), all shRNAs in the TRC collection (five to ten per gene) were used and analyzed including six shRNAs targeting SOX2. For the controls, two shRNAs against GFP and two against LacZ were included. Cells were plated in 384-well plates and on the following day infected with 1–3 ul of lentivirus with 8 ug/ml polybrene. Screens were performed with two replicates with and two replicates without puromycin, added 24 hours post-infection. Six days post-infection, wells were assayed using Cell-Titre Glo (Promega). Raw luminescence scores against the replicate wells with puromycin for a given shRNA construct in each cell line were normalized against readings for shGFP and shLacZ in that line. Analysis was performed with RIGER (RNAi Gene Enrichment Ranking)16,17 to compare the effects of each construct on the four 3q26.33-amplified lines to the construct’s effects in control cell lines to determine an enrichment score for each construct. Lower enrichment scores signify a greater decrease in proliferation in the 3q26.33-amplified cell lines. The enrichment scores were normalized against an enrichment score that would be generated by random permutation of an shRNA set of the same size to generate a normalized enrichment score for each gene. Comparison of the actual data to this permutation allows calculation of nominal P values and false discovery rate (FDR).

RNAi

Vectors with shRNA targeting SOX2 and GFP (Supplemental Table 2) were produced using TRC protocols (http://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai/trc). Cells were plated the day prior to infection and subsequently incubated with diluted virus in 8ug/mL polybrene for six hours. Puromycin was added the following day. After selection, cells were plated for proliferation or soft-agar assays. Protein was prepared for immunoblotting with anti-Sox2 polyclonal antibody (Abcam), anti-DCUN1D1 monoclonal antibody (Abcam) and anti-vinculin monoclonal antibody (Sigma) using standard techniques.

Retroviral Introduction of Genes

SOX2, and GFP were cloned into the pWZL vector with blasticidin resistance or the pBABE vector with puromycin resistance. FOXE1 and FGFR2 were cloned into the pBABE puro vector. Infections were performed with standard methods. Protein expression was confirmed via immunoblotting with antibodies to Sox2 (Abcam), vinculin (Sigma), FGFR2 (Santa Cruz) or FoxE1 (antibody kindly provided by Robert Di Lauro).

Anchorage-Independent Growth Assays

Cells were plated in triplicate in a top layer of growth media with 0.33% Noble Agar and plated onto a bottom layer of media with 0.5% Agar in a 6-well plate. Soft-agar colonies were counted at two to five weeks based upon growth rate. Images were acquired using Magnifire software by inverted microscopy (Olympus SZX9). ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) was used to quantify colony number.

Comparison of anchorage-independent growth vs. non-anchorage-independent growth was performed in NCI-H520 cells. Equal numbers of cells (in triplicate) were plated with either Noble Agar as above or regular growth media. Colony numbers in soft-agar were quantified as above. Foci formed in cells in regular media were identified with crystal violet staining using standard methods with foci quantified as for soft-agar.

Cell Proliferation Assays

Cells with stable expression of each shRNA construct were plated onto four replicate wells of a 96-well plate; and three identical plates were prepared. Cell proliferation was assayed at 24, 72 and 96 hours after plating with Cell-Titre Glo (Promega) on a Spectra Max5 plate reader. Cell numbers at 72 and 96 hours were corrected for the ratio of shSOX2 to shGFP cells from the 24-hour reading to correct for plating unevenness. A representative experiment is shown with viability +/− a standard deviation of the reading from the four wells shown.

Expression Analysis

From existing raw expression files expression data were generated using a gene-centric CDF file.33 We applied RMA and quantile normalization34 and the matchprobes package in the Bioconductor framework35 to create one single data set. Only patients with pathologic stage I/II disease and less than 80 years old at diagnosis had their tumor’s expression profile included in the analysis. To identify genes linked to SOX2, we identified the 10 lung SCCs with the highest and 10 lowest SOX2 expressions. To identify correlated genes, differential expression was calculated using the same package in Bioconductor.36 We used gene-set expression analysis37 to assess whether the signatures that define ES cell identity are active and related to SOX2 expression level in lung SCC tumors. SOX2 mRNA expression was characterized as high and low in cases with expression 0.5 standard deviations above or below the mean, respectively. The analysis utilized nine gene sets that were previously defined to be over-expressed in ES cells and performed as previously described.29

Real-Time PCR Assays

For expression analysis, RNA was extracted from cells using the Qiagen RNeasy kit and cDNA prepared with the Qiagen QuanTiTECT cDNA synthesis kit. All real-time PCRs were performed in triplicate with Power PCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with results normalized to GAPDH expression. Primers are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

Immunohistochemistry

TMAs were stained with a polyclonal Sox2 antibody (Chemicon) at 1:5000 dilution following Dako antigen retrieval38. After staining, we scanned the TMAs with the ZEISS MIRAX Scanner (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and then used the AxioVision Software to measure the grey scale value. Protein expression was quantified by the grey scale values of the epithelial cells and defined as a value from 0 (black) to 255 (white). For statistical analysis, values were inverted so that higher expression (black) corresponded to higher numerical values.

Statistical Analysis

For comparisons of all continuous variables between experimental groups, Student’s T-tests were used. Effects of SOX2 RNAi on cellular proliferation was modeled by fitting the growth curve of each cell line to an exponential growth model using GraphPad Prism software. Modeled growth curves for each shSOX2-expressing cell line were compared to that for the appropriate shGFP-expressing cell line curve; F-tests were used to determine p-value. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant; Bonferroni correction was performed for all experimental results in cell lines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Francis, J. Cho, A. Schinzel, R. Firestein, I. Guney, and J. Boehm for technical advice and discussions. A.J.B. is supported by the Harvard Clinical Investigator Training Program and American Society of Clinical Oncology. H.W. is supported by a Ruth L Kirschstein NRSA T32 institutional training grant. R.G.V. is supported by the KWF Kankerbestrijding. The Morphology, Molecular Biology and Cell Culture Core of 5P01CA098101-05 (A.K.R.) provided tissue processing for this project. This work was supported by Department of Defense VITAL grant (J.D.M./A.F.G.), National Cancer Institute grants K08CA134931 (A.J.B.), P50CA70907 (J.D.M/A.F.G.), R33CA128625 (W.C.H.), R01CA071606-12 (D.G.B), P01CA098101-05 (A.K.R.), and R01CA109038 and P20CA90578 (M.M.). Funding for lung SCC SNP arrays was provided by Genentech, Inc.

Footnotes

Data Accession

SNP array data are available via the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession GSE17958.

Author Contributions

L.R.C., H.N., D.B.S., L.L., T.J.G., J.D.M., A.F.G., M.S.B., I.C., U.R. Jr., S.K.M., O.D., M.S.T., K.K.W., and D.G.B., provided samples for analysis. S.P., P.W., C.J.L., V. S., T. W. and M.A.R. performed and analyzed FISH assays and immunohistochemistry analysis. C.H.M., R.G.V., P. T., I.G., A.H.R., B.A.W., G.G., R.B., M.O., J.K, C.M., S.R. and A.R. performed bioinformatic analysis. A.J.B, H.W., S.Y., S.K., L.W., P.D and C.Z. performed laboratory experiments. O.R., A.D. and M.S.W provided expression constructs and extensive technical expertise. R.A.S. and W.C.H. provided guidance regarding experimental design and data interpretation. A.J.B., H.W., A.K.R. and M.M. designed the study, analyzed data and prepared the manuscript. All authors discussed results and edited the manuscript.

Competing Interest Statement

Authors MM, WCH and RAS serve as consultants to Novartis. The authors know of no potential influence of this service upon the research presented in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Weir B, et al. Characterizing the cancer genome in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2007;450:893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature06358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garraway L, Sellers W. Lineage dependency and lineage-survival oncogenes in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:593–602. doi: 10.1038/nrc1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson KA, et al. Mutations in SOX2 cause anopthalmia esophageal-genital (AEG) syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1413–1422. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Que J, et al. Multiple dose-dependent roles for SOX2 in the patterning and differentiation of anterior foregut endoderm. Development. 2007;134:2521–31. doi: 10.1242/dev.003855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Que J, et al. Multiple roles for Sox2 in the developing and adult mouse trachea. Development. 2009;136:1899–1907. doi: 10.1242/dev.034629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wernig M, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beroukim R, et al. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: methodology and application to glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20007–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi Y, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization array analysis and real time PCR reveals genomic alterations in squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pack SD, et al. Molecular cytogenetic fingerprinting of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by comparative genomic hybridization reveals a consistent pattern of chromosomal alterations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;25:160–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199906)25:2<160::aid-gcc12>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massion PP, et al. Significance of p63 amplification and overexpression in lung cancer development and prognosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woenchhaus J, et al. Genomic gain of PIK3CA and increased expression of p110alpha are associated with progression of dysplasia into invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J Pathol. 2002;198:335–42. doi: 10.1002/path.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarkaria I, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma related oncogene/DCUN1D1 is highly conserved and activated by amplification in squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9437–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guttman M, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ebert BL, et al. Identification of RPS14 as a 5q-syndrome gene by RNA interference screen. Nature. 2008;451:335–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo B, et al. Highly parallel identification of essential genes in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20380–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810485105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundberg AS, et al. Immortalization and transformation of primary human airway epithelial cells by gene transfer. Oncogene. 2002;21:4577–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raponi M, et al. Gene expression signatures for predicting prognosis of squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the lung. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7466–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gudmundsson J, et al. Common variants on pp22.33 and 14q13.3 predispose to thyroid cancer in European populations. Nat Genet. doi: 10.1038/ng.339. In the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dathan N, Parlato R, Rosica A, De Felice M, Di Lauro R. Distribution of the titf2/foxe1 gene product is consistent with an important role in the development of foregut endoderm, palate, and hair. Dev Dyn. 2002;224:450–456. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clifton-Bligh RJ, et al. Mutation of the gene encoding human TTF-2 associated with thryoid agenesis, cleft palate and choanal atresia. Nat Gen. 1998;19:399–401. doi: 10.1038/1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dutt A, et al. Drug-sensitive FGFR2 mutations in endometrial carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8713–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803379105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kendall J, et al. Oncogenic cooperation coamplification of developmental transcription factor genes in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16663–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708286104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwei KA, et al. Genomic profiling identifieds TITF1 as a lienage-specific oncogene amplified in lung cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:3635–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka H, et al. Lineage-specific dependency of lung adenocarcinomas on the lung development regulator TTF-1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6007–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tonon G, et al. High-resolution genomic profiles of human lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9625–9630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504126102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shedden K, et al. Gene Expression-Based Survival Prediction in Lung Adenocarcinoma: A Multi-Site, Blinded Validation Study. Nat Med. 2008;14:822–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben-Porath I, et al. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X. Multilayered epithelium in a rat model and human Barrett’s esophagus: similar expression patterns of transcription factors and differentiation markers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rock JR, et al. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906850106. In the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perner S, et al. EML4-ALK fusion lung cancer: a rare acquired event. Neoplasia. 2008;10:298–302. doi: 10.1593/neo.07878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, et al. AffyProbeMiner: a web resource for computing or retrieving accurately redefined Affymetrix probe sets. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2385–90. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irizarry RA, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–64. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huber W, Gentleman R. Matchprobes: a Bioconductor package for the sequence-matching of microarray probe elements. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1651–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5116–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segal E, Friedman N, Koller K, Regev A. A module map showing conditional activity of expression modules in cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1090–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santagata S, Ligon KL, Hornick JL. Embryonic stem cell transcription factor signatures in the diagnosis of primary and metastatic germ cell tumors. Am J Surg Path. 2007;31:836–845. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31802e708a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.