Abstract

Retinoids and carotenoids are frequently used as antioxidants to prevent cancer. In this study, a panel of retinoids and carotenoids was examined to determine their effects on activation of RXR/CAR-mediated pathway and regulation of CYP3A gene expression. Transient transfection assays of HepG2 cells revealed that five out of thirteen studied retinoids significantly induced RXRα/CAR-mediated activation of luciferase activity that is driven by the thymidine kinase promoter-linked with a PXR binding site in the CYP3A4 gene [tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter]. All-trans retinoic acid (RA) and 9-cis RA were more effective than CAR agonist TCBOPOP in induction of the tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter. Addition of retinoid and TCBOPOP further enhanced the inducibility and the induction was preferentially mediated by RXRα/CAR and RXRγ/CAR heterodimer. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay showed that retinoids recruit RXRα and CAR to the proximal ER6 and distal XREM nuclear receptor response elements of the CYP3A4 gene promoter. The experimental data demonstrates that retinoids can effectively regulate CYP3A gene expression through the RXR/CAR-mediated pathway.

Keywords: RXR, CAR, Retinoid, CYP3A, Nuclear receptor

1. INTRODUCTION

The cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs) 2B and 3A subfamilies are the important enzymes involved in the oxidative metabolism of endogenous and exogenous compounds. Their expression is highly inducible by drugs as well as by environmental pollutants. Pregnane x receptor (PXR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), which heterodimerize with retinoid x receptor (RXR), are the principal regulators of hepatic CYP3A and CYP2B gene expression, respectively [1, 2]. Studies have revealed that the cross talk between PXR and CAR results in reciprocal activation of CYP2B and CYP3A genes [3, 4, 5]. Thus, dexamethasone, a PXR ligand, can induce Cyp2b10 in CAR-null mice, and phenobarbital (PB), a CAR activator, induces Cyp3a11 in PXR-null mice [4, 5, 6]. In addition to NR1 and NR2 sequences in the CYP2B promoter, CAR binds to the proximal response elements located in the CYP3A4 gene promoter region and can transcriptionally regulate CYP3A4 gene expression [4, 7, 8]. Moreover, human PXR and human CAR can also bind and activate the NR3 site (DR4) in the CYP2B6 XREM (xenobiotic-responsive enhancer module located in the distal region) and the DR3 (direct repeats spaced by 3 nucleotides) and ER6 (an everted repeat with a 6-nucleotide spacer) sites in the CYP3A4 XREM [8, 9].

Retinoids belong to the polyisoprenoid lipid family, which includes vitamin A (retinol) and its natural and synthetic analogs. In human, dietary animals and plants are the main sources of retinoids. A number of retinoids in this class possess anti-proliferative, differentiation, and pro-apoptotic effects [10]. Retinoids are used clinically to treat acute promyelocytic leukemia, skin cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma as well as acne and psoriasis [11]. The action of retinoids is mediated via activation of retinoid x receptors (RXRs). At least one third of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily members form dimmer with RXRs. RXR agonists activate certain RXR heterodimer complexes, which are termed permissive, in contrast, other non-permissive complexes do not respond to RXR agonists.

Retinoids exert complex effects on CYP gene expression. Several groups have reported the inductive effects of retinoids on CYP gene expression [12, 13, 14]. Conversely, it has been shown that 9-cis and all-trans RA repress phenobarbital-induced CYP2B1/2 in primary cultured rat hepatocytes and inhibit TCPOBOP-dependent CAR trans-activation of Cyp2b10 in mouse primary hepatocytes [15, 16]. In both cases, the authors proposed that the inhibitory effect of RA was due to competition between CAR and RARβ for binding to RXR. If this is the case, RA should also be able to inhibit other nuclear receptor-mediated pathways such as PXR/RXR. However, we recently reported that retinoids are capable of activating the RXR/hPXR-mediated pathway and RXR/VDR-mediated pathway leading to CYP3A4 induction in human hepatoma cells and mouse hepatocytes [17, 18]. Thus, it seems RXRs are permissive partners for activation of RXR/PXR-mediated CYP3A gene expression. The CAR/RXR heterodimers are neither strictly permissive nor non-permissive for RXR signaling [19]. Instead, the effects of retinoids on activation of RXR/CAR are distinct in different contexts. These findings suggest that retinoids may have complex and variable effects on xenobiotic responses [19]. The current study examines the effects of retinoids on activation of CAR-mediated pathways in regulation of CYP3A and CYP2B gene expression.

2. EXPERIMENTAL

2.1. Materials

All-trans RA, 9-cis retinal, 13-cis retinol, 9-cis RA, all-trans retinol palmitate (all-trans RP), β-carotene, lycopene, 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene (TCPOBOP), 4-(E-2-[5,6,7,8-tet-rahydro-5,5,8,8-tetramethyl-2-naphthalenyl]-1-propenyl) benzoic acid (TTNBP), and sterile dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Retinol acetate, 13-cis retinal, and fenretinide were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals. Lutein was purchased from US Biological, and 13-cis RA was obtained from BIOMOL Research Laboratories.

2.2. Cell culture and transient transfection

CV-1 cells were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA, USA). HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s Medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA, USA). The media was supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum (Biomeda, Foster City, CA, USA). Cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere with a relative humidity of 95%. Cells were plated onto 24-well plates with a cell density of approximately 8 × 104 cells/well (CV-1 cells) and 2.5 × 105 cells/well (HepG2 cells). The plated cells were cultured overnight and then transfected using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for CV-1 cells or Fugene 6 (Roche Diagnostics) for HepG2 cells with a mixture containing the tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter construct (300 ng), mRXRα and/or mCAR expression plasmid (50 ng each), and the internal control plasmid pRL-SV40 (10 ng).. The pRL-SV40 renilla luciferase expression plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used for co-transfection as an internal control for normalization of transfection efficiency. The total amount of plasmid DNA was adjusted to 410 nµg by addition of the control plasmid DNA lacking the cDNA. The tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter construct (provided by Dr. Wen Xie, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA), containing three copies of an everted repeat with a everted repeat 6-nucleotide spacer (ER-6) element from the CYP3A4 gene, was used as a reporter. Expression plasmids of mouse RXRα, β, or γ (gifts from Dr. Ronald Evans, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, CA, USA), mRXRαY402A (a gift from Dr. Hinirch Gronemeyer, Institut de Génétique et de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire, France), and mouse CAR (a gift from Dr. Wen Xie) were used for cotransfection as indicated. After transfection, cells were treated with retinoids (10 µM). Fresh medium and retinoids or TCPOBOP were provided every 24 hours. After forty-eight hour treatments, cells were harvested and luciferase assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

2.3. Isolation of mouse hepatocytes

The C57BL/6 mice were housed at 22°C with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle and provided food and water ad libitum. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Kansas University Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Hepatocytes were isolated from 3-month-old mice, weighing 20 to 28 g using a modified in situ two-step collagenase perfusion method [20]. Briefly, livers were perfused in situ via the portal vein, first with calcium and magnesium free Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS-; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 0.5 mM EGTA and 10 mM HEPES (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 6–8 min, and then with HBSS with calcium and magnesium (HBSS+; Invitrogen) containing 10 mM HEPES, 0.5 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma–Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) and 0.05 mg/ml soybean type IIS trypsin inhibitor (Sigma–Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) for 6–7 min, at a flow rate of 10 ml/min. Perfused livers were gently isolated, decapsulated on ice, and dispersed in ice-cold HBSS−. Dispersed cells were filtered through 100 µm nylon meshes, rinsed, suspended in ice-cold 35% (v/v) Percoll (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and centrifuged at 150 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Hepatocytes were rinsed and suspended in William’s E culture medium (Sigma–Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), 10% fetal calf serum (Biomeda, Foster City, CA, USA), 2.5 µg/ml insulin (Sigma–Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were seeded in 24-well type I collagen-coated plates at 37°C in 5% CO2 with a relative humidity of 95%. Initial cell viability assessed by 0.4% Trypan blue stain (Sigma–Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) exclusion was greater than 80%. After 48-h culture, cells were treated with different compounds for 48 h. Fresh medium with retinoids or TCPOBOP were provided after the initial 24 h treatment.

2.4. Real-Time PCR

Hepatocytes were harvested after 48 h treatments and total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (1 µg) using random primer and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cyp3a11 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) TaqMan PCR primers and fluorescent probes (Sigma–Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The sequences are shown as follows, in the order of forward primer, reverse primer, and probe (FAM, 5-carboxyfluorescein; BHQ1, Black Hole Quencher 1): Cyp3a11, 5’-TCACAGACCCAGAGACGATTAAGA-3’, 5’-CCCGCCGGTTTGTGAAG-3’, 6FAM-TGTGCTAGTGAAGGAATGTTTTTCT-BHQ1; and GAPDH, 5’-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA-3’, 5’-CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGA-3’, 6FAM-CCGCCTGGAGAAACCTGCCA-BHQ1. To avoid potential genomic DNA contamination, 5’ and 3’ primers were designed to span exon-exon junctions. Moreover, the primers and probe were confirmed to be specific using BLAST. TaqMan PCR assays were performed in 96-well optical plates on an ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Cycling parameters for each of the PCR reactions were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Cyp3a11 mRNA level was normalized against that of mouse GAPDH. Fold induction values were calculated using ΔΔCt method according to manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

HepG2 cells were grown to 80% confluence in 6-well plates then transfected with mCAR and mRXRα expression plasmids (0.2 µg). Following the treatment of retinoids or TCPOBOP for 48 h, the cells were harvested for ChIP assay using a ChIP Assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were washed twice with PBS and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min, then sonicated on ice with 10-s ultrasound bursts generated by a Model 500 Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) at 10% power for a total of 1 minutes. One tenth of the chromatin solution was reserved for subsequent amplification of total input. Soluble chromatin was immunoprecipitated with antibodies against RXRα, CAR or nonimmune rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and then incubated with protein A-agarose beads. The beads were washed and the samples were eluted. Cross-links were reversed by heating samples at 65°C overnight and DNA was purified using a Qiaquick Spin Column (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA). To identify the immunoprecipitated DNA fragments, PCR was performed using specific primers flanking either the proximal ER6 region (−281 to −80; sense: 5'- GGCGATTTAATAGATTTTATGC-3'; antisense: 5'- TGCTCTGCCTGCAGTTGGAA-3') or distal XREM region (dDR3/ER6; −7,771 to −7,562; sense: 5'-CCCAATTAAAGGTCATAAA-3'; antisense: 5'- CAGAAGTTCAGCTTGTGATTC -3') of CYP3A4 promoter. The number of amplification cycles used for each target gene was empirically determined. Amplified fragments were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel. A gel-imager with Quantity One software version 4.5.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to visualize and quantitate the intensity of the bands.

3. RESULTS

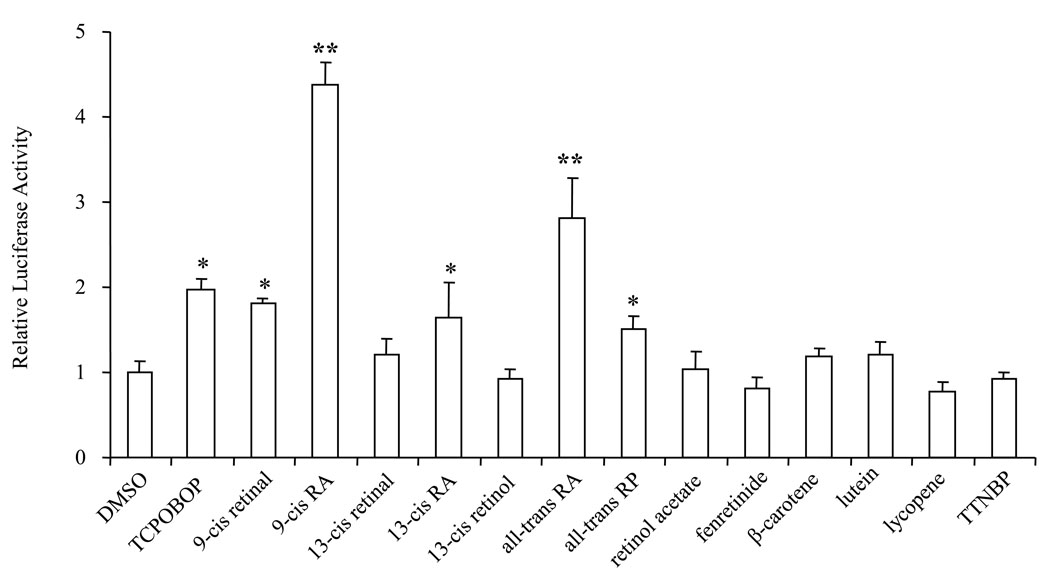

3.1. Retinoids transactivate the RXRα/CAR-mediated pathway

To determine whether retinoids can activate RXRα/CAR-mediated pathway and regulate CYP3A gene expression, transient transfection assays were performed using HepG2 cells. We used HepG2 cells because this cell line expresses low level of CAR, and endogenous CYP2B6 mRNA cannot be induced by TCPOBOP [21]. HepG2 cells were transfected with CAR and RXRα expression plasmids and the reporter construct tk-(3A4)3-Luc, which contains three copies of the ER6 motif located in the regulatory region of the CYP3A4 gene. Figure 1 shows that CAR agonist TCPOBOP, which typically induces CYP2B gene expression, induced tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter activity by 2-fold in the presence of CAR and RXRα expression plasmids. This result is consistent with published findings (7, 19) and indicates cross talk between CAR and PXR in activating CYP3A. Among the thirteen retinoids and cartenoids studied, five increased tk-(3A4) 3-Luc activity in HepG2 cells when CAR and RXRα were expressed. There was no induction when CAR and RXRα were not included in the transfection (data not shown). 9-cis RA (4.4-fold) and all-trans RA (2.8-fold) were more effective than TCPOBOP and demonstrated the highest inducibility. All-trans retinol palmitate (all-trans RP), 9-cis retinal, and 13-cis RA moderately induced reporter activity with a similar induction fold as TCPOBOP.

Figure 1. Activation of the RXRα/CAR-mediated pathway by retinoids.

HepG2 were transiently transfected with mRXRα and mCAR expression plasmids (50 ng each), the tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter construct (300 ng), and the renilla luciferase expression vector (10 ng). The transfected cells were treated with TCPOBOP (10 µM), the indicated retinoids (10 µM), or DMSO (0.1%) for 48 h and then assayed for luciferase activity. The results are expressed as relative fold changes of luciferase activity to DMSO control. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared to control (DMSO).

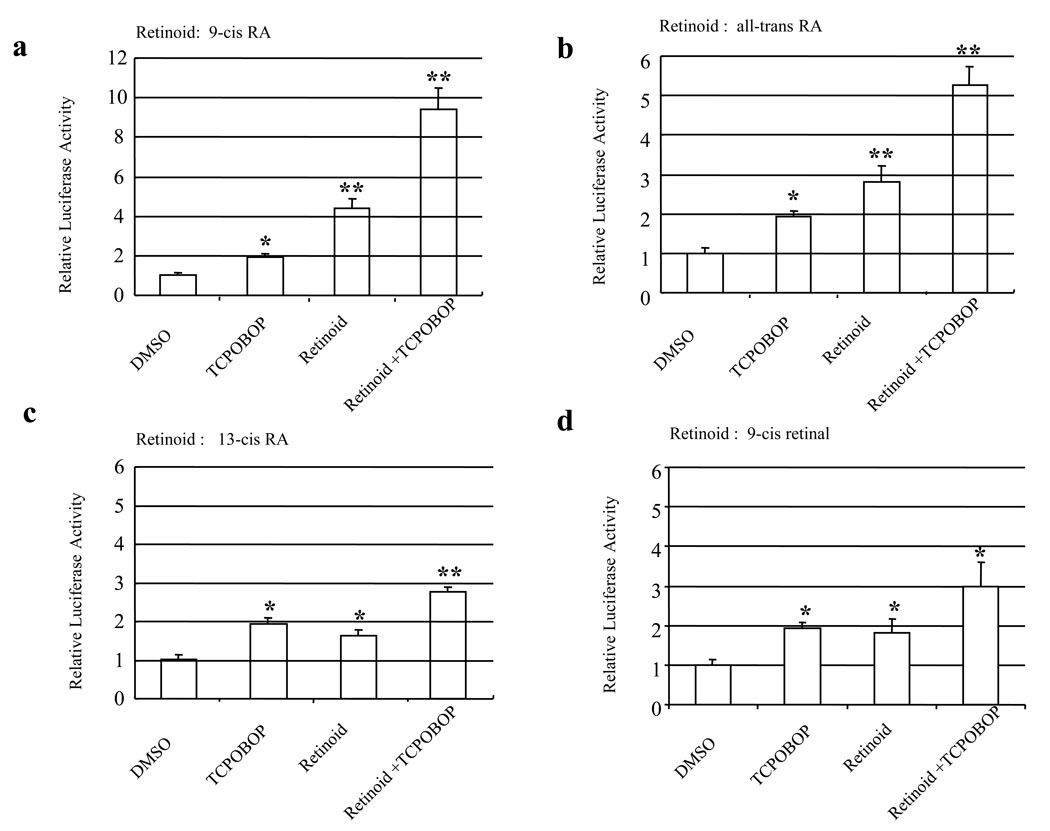

Combination treatments were performed to test the interaction between retinoids and TCPOBOP (Fig. 2). The fold induction was further increased when both retinoids and TCPOBOP were used to treat the cells in comparison with when single chemical was used. For example, the fold induction was 2.0, 4.4, and 9.4 when TCPOBOP, 9-cis RA, and combination of both were used to treat the cells, respectively.

Figure 2. The combination effects of retinoids plus TCPOBOP on activation of RXRα/CAR activation.

HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with the mRXRα and mCAR expression plasmids (50 ng each), the tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter construct (300 ng), and the renilla luciferase expression vector (10 ng). Cells were treated with DMSO (0.1%), retinoid (Re, 10 µM), TCPOBOP (10 µM), or their combination for 48 h. Then cells were harvested for luciferase assays. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared to control (DMSO).

3.2. Retinoids induce Cyp3a11 mRNA

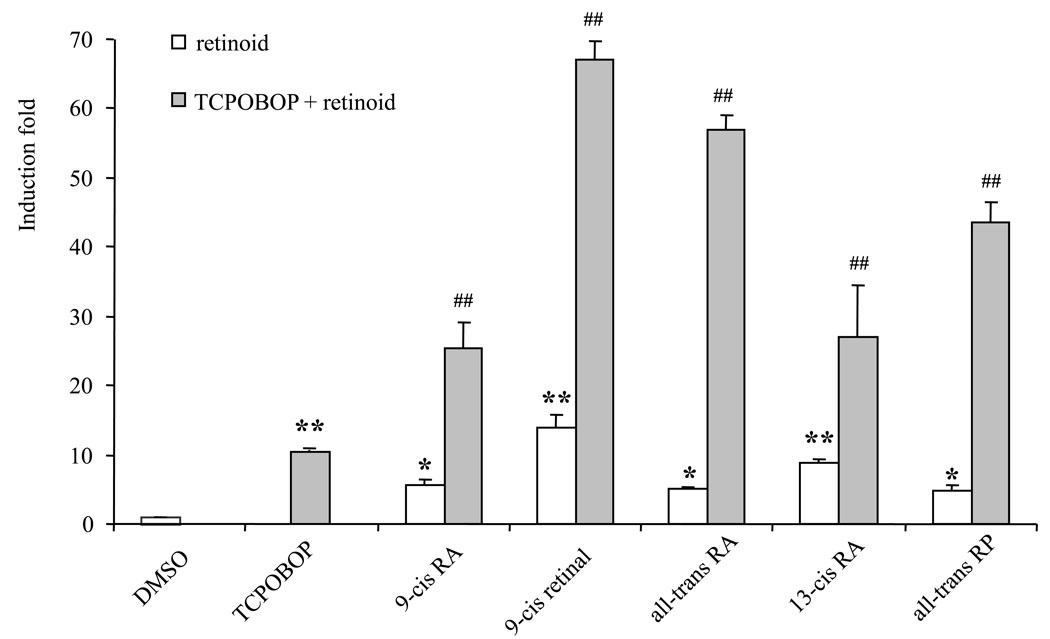

Retinoid-mediated Cyp3a11 induction was confirmed using mouse primary hepatocytes by real-time PCR. The expression of Cyp3a11 mRNA was monitored in primary hepatocytes treated with TCPOBOP, retinoids, and combination of TCPOBOP plus retinoids. As anticipated, basal Cyp3a11 mRNA was detectable in mouse primary hepatocytes, and Cyp3a11 mRNA was induced 10.5-fold by TCPOBOP (Fig. 3). The five retinoids which induced CAR/RXR-mediated activation of tk-(3A4) 3-Luc also increased Cyp3a11 mRNA levels in primary mouse hepatocytes. However, the relative strength of these retinoids in activation of tk-(3A4)3-Luc in HepG2 cells was different from the induction of Cyp3a11 mRNA in primary mouse hepatocytes. This is probably due to the presence of different levels of co-factors or enzymes in these two types of cells. 9-Cis retinal, which only moderately trans-activated tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter in HepG2 cells, exhibited the highest Cyp3a11 mRNA induction in mouse primary hepatocytes. Consistent with transient transfection assay results, the levels of Cyp3a11 mRNA were further increased when both retinoids and TCPOBOP were utilized than when a single agent was used (Fig. 3). We cannot rule out the possibility that retinoids might activate nuclear receptors other than RXR/CAR to induce Cyp3a11 expression. However, the fold induction was much greater using a combination of CAR agonist and retinoids than when a single chemical was used, suggesting that retinoids could further activate TCPOBOP-activated RXR/CAR signaling pathway. The experimental data, therefore, strongly suggest that retinoids play a role to activate the RXR/CAR signaling pathway and induce Cyp3a11 gene expression in mouse primary hepatocytes. On the other hand, the retinoids employed were ineffective in inducing the levels of Cyp2b10 mRNA (data not shown).

Figure 3. The effect of retinoids and TCPOBOP on Cyp3a11 gene expression in primary mouse hepatocytes.

Forty-eight hours after plating, mouse hepatocytes were treated with DMSO (0.1%), retinoids (10 µM), TCPOBOP (10 µM), or their combination for 48 h. Total RNA was extracted; Gapdh and Cyp3a11 mRNA levels were quantified by Taqman real-time PCR. The results are expressed as relative fold changes of compound-treated to DMSO-treated control. Each value represents the mean ± SD of each treatment in triplicate. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared to DMSO, ## P < 0.01, compared to TCPOBOP.

3.3. Differential activation of RXR isoforms and CAR by retinoids

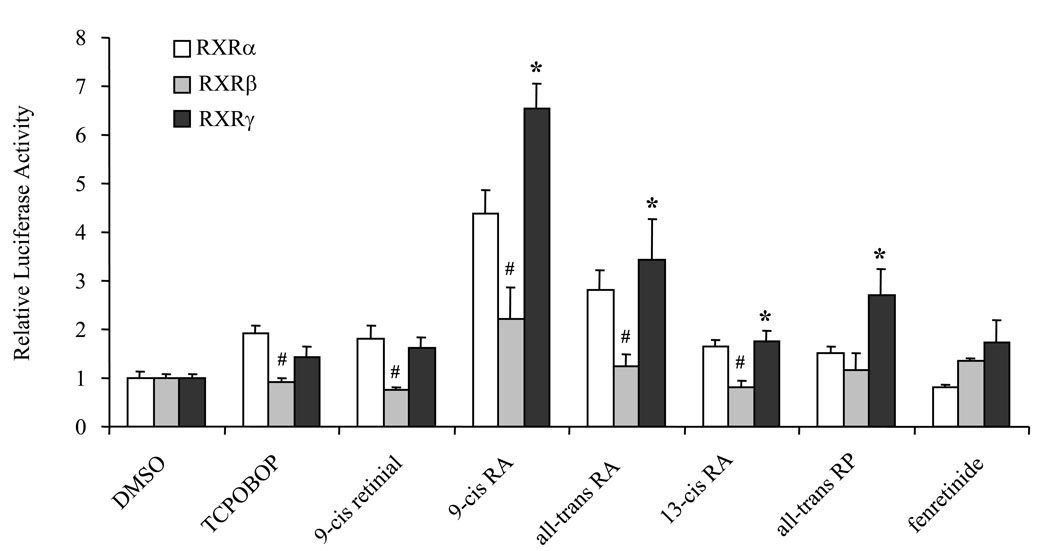

To understand the differential role of RXRα, β, and γ in retinoid-mediated CYP3A induction through the CAR signaling pathway, expression plasmids of RXRα, β, γ, and CAR as well as tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter were transfected into HepG2 cells. The cells were treated with DMSO, TCPOBOP, and retinoids for 48 h after transfection. The results revealed that expression of RXRα, β, and γ in HepG2 cells leads to differential induction of luciferase activity in response to retinoids and TCPOBOP (Fig. 4). 9-Cis retinal, 9-cis RA, 13-cis RA, all-trans RA, and all-trans RP preferentially activated the RXRα/CAR- and RXRγ/CAR-, but not RXRβ/CAR-, mediated pathways. Only 9-cis RA and all-trans RA could modestly induce the luciferase activity mediated by RXRβ/CAR. Fenretinide, a synthetic retinoid, did not induce luciferase activity through any of the RXR isoforms.

Figure 4. Differential activation of RXR isoforms and CAR by retinoids in HepG2 cells.

HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with the mCAR expression plasmids (50 ng), one of the mRXR isoforms (α, β, and γ) (50 ng), the tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter construct (300 ng), and the renilla luciferase expression vector (10 ng). Cells were treated with DMSO (0.1%), retinoid (10 µM), TCPOBOP (10 µM) for 48 h and then assayed for luciferase activity. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. # P < 0.05, compared to RXRα within each treatment group. * P < 0.05 compared to RXRβ within each treatment group.

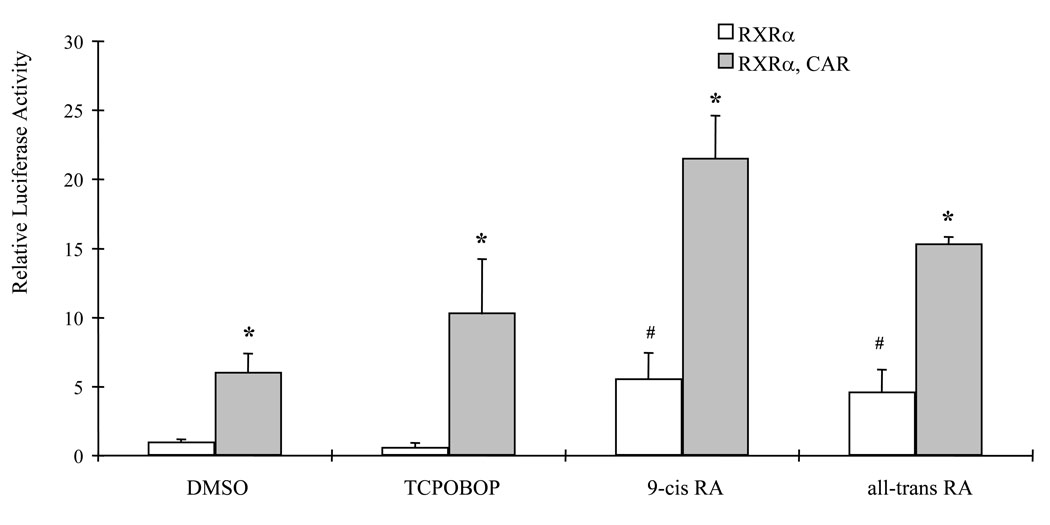

3.4. Retinoids differentially activate the RXRα homodimers and RXRα/CAR heterodimers

To investigate the role of RXRα homodimer and RXRα/CAR heterodimer in activation of tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter, CV-1 cells, which have low levels of endogenous nuclear receptors, were transfected with the RXRα expression plasmid and the tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter construct in the absence or presence of a CAR expression plasmid. Transfected cells were treated with DMSO, TCPOBOP, or retinoids for 48 h. In the absence of CAR, TCPOBOP did not induce the reporter activity, suggesting that the level of endogenous CAR in CV-1 cells were too low to activate tk-(3A4)3-Luc (Fig. 5). Expression of RXRα alone in the cells treated with 9-cis RA or all-trans RA induced the reporter activity about 5-fold in CV-1 cells. When both RXRα and CAR were expressed, luciferase activity was induced by DMSO treatment (6.0-fold) indicating the constitutive activation nature of CAR. In addition, all-trans RA (15.3-fold) and 9-cis RA (21.6-fold) were able to further induce tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter activity when both RXRα and CAR were expressed in the CV-1 cells (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Retinoids preferentially activate RXRα/CAR heterodimer rather than RXRα homodimer.

CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with the tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter construct (300 ng), the renilla luciferase expression vector (10 ng), and the mRXRα and mCAR expression plasmids as indicated (50 ng each). Cells were treated with DMSO (0.1%), TCPOBOP (10 µM), or retinoids (10 µM) for 48 h. Cells were then harvested for luciferase assays. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. * P < 0.05, compared to RXRα within each treatment group. # P < 0.05, compared to control (DMSO) treatment group without CAR expression plasmid.

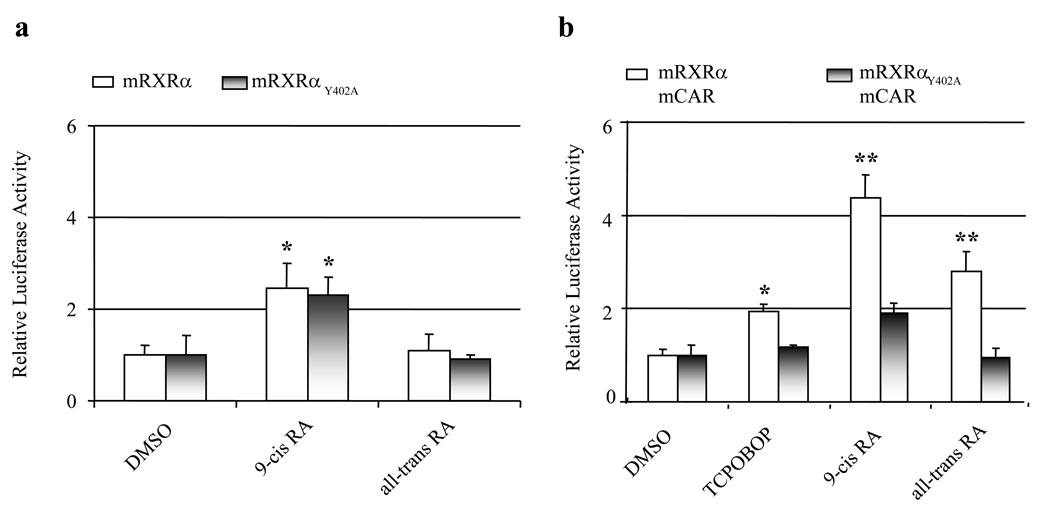

A mutant RXRα plasmid mRXRαY402A, which preferentially forms homodimers rather than heterodimers [22], was used to confirm that retinoids preferentially activate the RXRα/CAR heterodimer-mediated pathways. Transfection of wild type RXRα or mRXRαY402A produced over 2-fold induction of the reporter activity upon 9-cis RA treatment of HepG2 cells. However, all-trans RA, which could induce tk-(3A4)3-Luc activity in CV-1 cells, neither activated RXRα homodimer nor mRXRαY402A homodimer in HepG2 cells (Fig. 6a). In comparison with transfection of RXRα and CAR expression plasmids into cells in which retinoids significantly induced luciferase activity, expression of mRXRαY402A and CAR significantly reduced retinoid-mediated induction of luciferase activity (Fig. 6b). These findings indicated that it is the heterodimer of RXRα/CAR that mediates retinoid-induced tk-(3A4)3-Luc activity.

Figure 6. The differential effects of RXRα homodimer and RXRα/CAR heterodimer on retinoid-induced tk-(3A4)3-Luc activity in HepG2 cells.

HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with the tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter construct (300 ng), the renilla luciferase expression vector (10 ng), and (a) mRXRα or mRXRαY402A (50 ng each), or (b) mCAR plus mRXRα or mRXRαY402A (50 ng each) expression plasmid. Cells were treated with indicated RA (10 µM) for 48 h, and then harvested for luciferase assays. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared to control (DMSO).

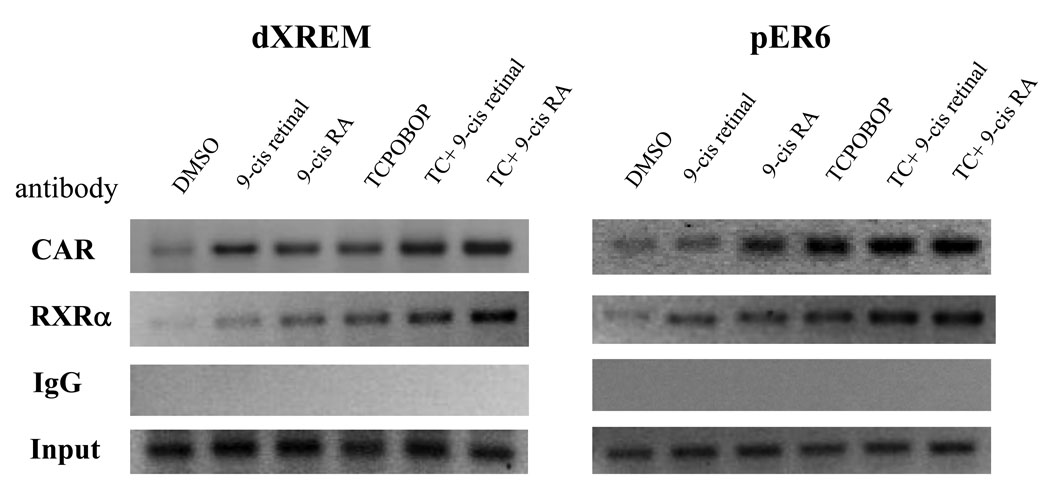

3.6. Retinoids recruit RXRα and CAR to the promoter region of the CYP3A4 gene

ChIP assay showed that 9-cis retinal, 9-cis RA, and TCPOBOP alone could recruit CAR and RXRα to the dXREM and ER6 in the regulatory region of the CYP3A4 gene. The recruitment was further enriched when both retinoid and TCPOBOP were used (Figure 7). Nonspecific IgG control did not immunoprecipitate appreciable amounts of promoter DNA. These results demonstrate that 9-cis retinal and 9-cis RA are effective in recruiting RXRα/CAR to the nuclear receptor response elements in the CYP3A4 gene.

Figure 7. Recruitment of CAR and RXRα to the CYP3A4 promoter by retinoids.

Cells were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), 9-cis retinal, 9-cis RA, TCPOBOP (TC), or their combinations for 48h and then subjected to ChIP analysis using antibodies against CAR, RXRα, or IgG. DNA precipitates were isolated and PCR was used to analyze the DNA fragments containing distal XREM (left panel) or proximal ER6 (right panel) response element. Ten percent of the total cell lysate was used as input.

4. DISCUSSION

The nuclear receptor CAR has been shown to be responsible for many important xenobiotic responses [23]. It functions as a heterodimeric partner of RXR and can recruit coactivators in the presence and absence of ligands [24, 25]. Besides CYP2B, CAR has been reported to directly regulate the transcriptional activity of the CYP3A4 gene both in vitro and in vivo [8]. Recently, Faucette et al. [26] reported that CAR exhibits a weak induction of CYP3A4 relative to CYP2B6 because of its weak binding and functional activation of the CYP3A4 ER6. The current paper demonstrates that several retinoids can activate the RXR/CAR-mediated pathway and induce CYP3A expression. Moreover, a strong induction is achieved with combination treatment of TCPOBOP and retinoids, which implicates the importance of CAR in regulating CYP3A gene expression.

Our transfection data show retinoids induce higher or similar reporter activity compared with the typical CAR agonist TCPOBOP. These findings are in agreement with the literature. Previous studies show a synthetic RXR agonist, LG1069, activates a CYP3A reporter containing an ER6 element through RXR/CAR-mediated pathway [19]. In addition, our data also show that retinoids as well as TCPOBOP induce Cyp3a11 gene expression in mouse primary hepatocytes suggesting the role retinoids play in the induction of Cyp3a11 in normal hepatocytes. It is known that PXR [4, 8], CAR [27], and VDR [28, 29] can directly regulate CYP3A expression in vivo. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that these nuclear receptors might also participate in retinoid-mediated Cyp3a11 induction in mouse primary hepatocytes. However, the role of CAR in mediating retinoid-induced Cyp3a11 expression is evidenced by enhanced Cyp3a 11 expression when a combination of retinoids and TCBOPOP were used as well as in the transient transfection experiment using CV-1 cells, which have low endogenous nuclear receptors. It has been shown that the addition of 9-cis RA and TCPOBOP simultaneously can increase the affinity for coactivators by improving the entropic component of binding [30]. Thus, the enhanced induction of Cyp3a expression by combination treatment can be due to an increase in binding affinity of a cofactor or recruitment of additional and/or different cofactors. Moreover, the ChIP assay data also showed combinational treatment of retinoids and TCPOBOP enhanced the recruitment of CAR and RXRα to the regulatory region of the CYP3A4 gene. However, it should be noted that the expression of exogenously expressed receptors may be much greater than what is found in normal cells, thus the results of modulated CYP3A4 expression will need to be confirmed in normal cells (i.e., primary hepatocytes) or in vivo.

In primary hepatocytes, the induction effects of certain retinoids are different from those observed in the HepG2 cells. All-trans RP, 9-cis retinal, and 13-cis RA, which only moderately activate luciferase reporter activity in HepG2 cells, highly induce Cyp3a11 mRNA level in mouse primary hepatocytes. This discrepancy may be due to differential retinoid metabolism in primary mouse hepatocytes and established human cell line. Retinyl palmitates, retinol, and retinal can be converted into retinoic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALHDs), CYP2C19, CYP3A4, and CYP1A1/2 in hepatocytes. Primary hepatocytes maintain most phase I and phase II enzymes necessary for retinoid metabolism, while cell lines may express a limited range of CYP450 and conjugation enzymes [31]. The difference in expression of transcription cofactors in these two cell types might also contribute to differential inducibility.

Though the activation of CAR may aid in the clearance of the toxic xenobiotics and endogenous molecules, its activity can also be deleterious, as CAR-mediated induction of cytochrome P450 contributes to cocaine-induced hepatotoxicity [32]. CAR has also been proven to be responsible for the induction of hepatomegaly and liver tumors by xenobiotic stresses [23, 33, 34]. Furthermore, the interindividual variations in CAR activity have a significant impact on the metabolism of a wide range of pharmacological agents and other foreign compounds, and could be the basis for the relatively rare but clinically significant hepatotoxicity [35]. In this sense, further investigation of the activation of downstream target genes of CAR by retinoids may facilitate better understanding of the diverse effects of retinoid therapy and may help avoid adverse drug-drug interactions.

Retinoids are used as cancer therapeutic and chemopreventive agents. They exert multiple biological effects due to their diverse structures, nuclear receptor binding affinities, and toxicity profiles [10]. The concentration of retinoids used in our experiments might not be physiologically relevant. However, it is likely to have a pharmacological or potential toxicological effect when high dose of retinoids is used. The rapid resistance of therapeutic doses of retinoids has not been studied [36]. Some of the CYP enzymes under retinoid-mediated transcriptional control [12, 13] are themselves responsible for retinoid metabolism [37, 38]. Thus, induction of CYP3A by retinoids may enhance the metabolism of retinoids themselves, which in turn may partially account for the development of retinoid resistance.

CYP3A4, the predominant CYP gene expressed in liver and small intestine, is involved in the metabolism of approximately 60% of all therapeutic drugs and is reported to be involved in many clinically important drug interactions [39, 40]. CYP3A4 expression is affected by factors such as hormonal status, nuclear receptor activity, xenobiotic exposure, and possibly by genetic polymorphisms. We show enhanced induction of CYP3A by retinoids and CAR agonists. Increased expression of CYP3A4 may produce adverse drug-drug interactions [40]. While this effect could improve the clearance of potentially toxic compounds, it could also lead to reduction in treatment efficacy by rapidly decreasing drug concentrations below therapeutic effect ranges. Additionally, CYP3A up regulation may cause acute toxicity through production of detrimental metabolites. The xenobiotic induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes underlies many reported drug interactions and is vital for patients subjected to combination drug therapy [39]. Our findings provide insights into the appropriate therapeutic use of retinoids during clinical treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Hinrich Gronemeyer for the mRXRαY402A expression plasmid, Dr. Ronald Evans for the RXRα, β, and γ expression plasmids, and Dr. Wen Xie for the CAR expression plasmid and the tk-(3A4)3-Luc reporter construct. The authors are grateful to Mr. Matthew Wortham and Ms. Barbara Brede for editing the manuscript.

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA53596 and COBRE P20 RR021940.

Abbreviations used

- ALHD

aldehyde dehydrogenases

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- RA

retinoic acid

- all-trans RP

all-trans retinol palmitate

- PXR

pregnane x receptor

- CAR

constitutive androstane receptor

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- mCAR

mouse constitutive androstane receptor

- mRXR

mouse retinoid x receptor

- ER

everted repeat

- DR

direct repeat

- NR

nuclear receptor

- NR1, NR2

nuclear receptor site1, 2

- XREM

xenobiotic-responsive enhancer module

- RT

reverse transcription

- Gadph

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- TCPOBOP

1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blumberg B, Sabbagh W, Jr, Juguilon H, Bolado J, Jr, van Meter CM, Ong ES, et al. SXR, a novel steroid and xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3195–3205. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honkakoski P, Zelko I, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M. The nuclear orphan receptor CAR-retinoid X receptor heterodimer activates the phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module of the CYP2B gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5652–5658. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore LB, Parks DJ, Jones SA, Bledsoe RK, Consler TG, Stimmel JB, et al. Orphan nuclear receptors constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor share xenobiotic and steroid ligands. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(20):15122–15127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie W, Barwick JL, Simon CM, Pierce AM, Safe S, Blumberg B, et al. Reciprocal activation of xenobiotic response genes by nuclear receptors SXR/PXR and CAR. Genes Dev. 2000a;14:3014–3023. doi: 10.1101/gad.846800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei P, Zhang J, Dowhan DH, Han Y, Moore DD. Specific and overlapping functions of the nuclear hormone receptors CAR and PXR in xenobiotic response. Pharmacogenomics J. 2002;2(2):117–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie W, Barwick JL, Downes M, Blumberg B, Simon CM, Nelson MC, et al. Humanized xenobiotic response in mice expressing nuclear receptor SXR. Nature. 2000b;406:435–439. doi: 10.1038/35019116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzameli I, Pissios P, Schuetz EG, Moore DD. The xenobiotic compound 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene is as agonist ligand for the nuclear receptor CAR. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2951–2958. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.2951-2958.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin B, Hodgson E, D'Costa DJ, Robertson GR, Liddle C. Transcriptional regulation of the human CYP3A4 gene by the constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62(2):359–365. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Faucette S, Sueyoshi T, Moore R, Ferguson S, Negishi M, et al. A novel distal enhancer module regulated by pregnane X receptor/constitutive androstane receptor is essential for the maximal induction of CYP2B6 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(16):14146–14152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dragnev KH, Rigas JR, Dmitrovsky E. The retinoids and cancer prevention mechanisms. ↰Oncologist. 2000;5(5):361–368. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vincent CO Njar, Lalji Gediya, Puranik Purushottamachar, Pankaj Chopra, Tadas Sean Vasaitis, Aakanksha Khandelwal, et al. Retinoic acid metabolism blocking agents (RAMBAs) for treatment of cancer and dermatological diseases. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;14:4323–4340. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray WJ, Bain G, Yao M, Gottlieb DI. CYP26, a novel mammalian cytochrome P450, is induced by retinoic acid and defines a new family. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(30):18702–18708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reijntjes S, Gale E, Maden M. Expression of the retinoic acid catabolising enzyme CYP26B1 in the chick embryo and its regulation by retinoic acid. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3(5):621–627. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashkar S, Mesentsev A, Zhang WX, Mastyugin V, Dunn MW, Laniado-Schwartzman M. Retinoic acid induces corneal epithelial CYP4B1 gene expression and stimulates the synthesis of inflammatory 12-hydroxyeicosanoids. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(1):65–74. doi: 10.1089/108076804772745473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada H, Yamaguchi T, Oguri K. Suppression of the expression of the CYP2B1/2 gene by retinoic acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:66–71. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakizaki S, Karami S, Negishi M. Retinoic acids repress constitutive active receptor-mediated induction by 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene of the CYP2B10 gene in mouse primary hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:208–211. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang K, Mendy AJ, Dai G, Luo HR, He L, Wan YJ. Retinoids activate the RXR/SXR-mediated pathway and induce the endogenous CYP3A4 activity in Huh7 human hepatoma cells. Toxicol Sci. 2006;92:51–60. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K, Chen S, Xie W, Wan YJ. Retinoids induce cytochrome P450 3A4 through RXR/VDR-mediated pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(11):2204–2213. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tzameli I, Chua SS, Cheskis B, Moore DD. Complex effects of rexinoids on ligand dependent activation or inhibition of the xenobiotic receptor, CAR. Nucl Recept. 2003;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-1336-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selgen PO. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Meth Cell Biol. 1976;13:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swales K, Kakizaki S, Yamamoto Y, Inoue K, Kobayashi K, Negishi M. Novel CAR-mediated mechanism for synergistic activation of two distinct elements within the human cytochrome P450 2B6 gene in HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(5):3458–3466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vivat-Hannah V, Bourguet W, Gottardis M, Gronemeyer H. Separation of retinoid X receptor homo- and heterodimerization functions. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(21):7678–7688. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7678-7688.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei P, Zhang J, Egan-Hafley M, Liang S, Moore DD. The nuclear receptor CAR mediates specific xenobiotic induction of drug metabolism. Nature. 2000;407:920–923. doi: 10.1038/35038112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baes M, Gulick T, Choi HS, Martinoli MG, Simha D, Moore DD. A new orphan member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that interacts with a subset of retinoic acid response elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(3):1544–1552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dussault I, Lin M, Hollister K, Fan M, Termini J, Sherman MA, et al. A structural model of the constitutive androstane receptor defines novel interactions that mediate ligand-independent activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5270–5280. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5270-5280.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faucette SR, Sueyoshi T, Smith CM, Negishi M, Lecluyse EL, Wang H. Differential regulation of hepatic CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 genes by constitutive androstane receptor but not pregnane X receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317(3):1200–1209. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodwin B, Moore LB, Stoltz CM, McKee DD, Kliewer SA. Regulation of the human CYP2B6 gene by the nuclear pregnane X receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:427–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drocourt L, Ourlin JC, Pascussi JM, Maurel P, Vilarem MJ. Expression of CYP3A4, CYP2B6, and CYP2C9 is regulated by the vitamin D receptor pathway in primary human hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25125–25132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thummel KE, Brimer C, Yasuda K, Thottassery J, Senn T, Lin Y, et al. Transcriptional control of intestinal cytochrome P-4503A by 1alpha, 25-dihydroxy vitamin D3. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:1399–1406. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.6.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright E, Vincent J, Fernandez EJ. Thermodynamic characterization of the interaction between CAR-RXR and SRC-1 peptide by isothermal titration calorimetry. Biochemistry. 2007;46(3):862–870. doi: 10.1021/bi061627i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perocco P, Del Ciello C, Mazzullo M, Rocchi P, Ferreri AM, Paolini M, et al. Cytotoxic and cell transforming activities of the fungicide methyl thiophanate on BALB/c 3T3 cells in vitro. Mutat Res. 1997;394(1–3):29–35. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(97)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bornheim LM. Effect of cytochrome P450 inducers on cocaine-mediated hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;150(1):158–165. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto Y, Moore R, Goldsworthy TL, Negishi M, Maronpot RR. The orphan nuclear receptor constitutive active/androstane receptor is essential for liver tumor promotion by phenobarbital in mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7197–7200. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang W, Zhang J, Washington M, Liu J, Parant JM, Lozano G, et al. Xenobiotic stress induces hepatomegaly and liver tumors via the nuclear receptor constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(6):1646–1653. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selim K, Kaplowitz N. Hepatotoxicity of psychotropic drugs. Hepatology. 1999;29(5):1347–1351. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marill J, Idres N, Capron CC, Nguyen E, Chabot GG. Retinoic acid metabolism and mechanism of action: a review. Curr Drug Metab. 2003;4:1–10. doi: 10.2174/1389200033336900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang QY, Dunbar D, Kaminsky L. Human cytochrome P-450 metabolism of retinals to retinoic acids. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:292–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McSorley LC, Daly AK. Identification of human cytochrome P450 isoforms that contribute to all-trans-retinoic acid 4-hydroxylation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60(4):517–526. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michalets EL. Update: clinically significant cytochrome P-450 drug interactions. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:84–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maurel P. The CYP3A family. In: Ioannides C, editor. Cytochromes P450: Metabolic and Toxicological Aspects. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1996. pp. 241–270. [Google Scholar]