Abstract

Background

The fungivorus nematode, Aphelenchus avenae is widespread in soil and is found in association with decaying plant material. This nematode is also found in association with plants but its ability to cause plant disease remains largely undetermined. The taxonomic position and intermediate lifestyle of A. avenae make it an important model for studying the evolution of plant parasitism within the Nematoda. In addition, the exceptional capacity of this nematode to survive desiccation makes it an important system for study of anhydrobiosis. Expressed sequence tag (EST) analysis may therefore be useful in providing an initial insight into the poorly understood genetic background of A. avenae.

Results

We present the generation, analysis and annotation of over 5,000 ESTs from a mixed-stage A. avenae cDNA library. Clustering of 5,076 high-quality ESTs resulted in a set of 2,700 non-redundant sequences comprising 695 contigs and 2,005 singletons. Comparative analyses indicated that 1,567 (58.0%) of the cluster sequences had homologues in Caenorhabditis elegans, 1,750 (64.8%) in other nematodes, 1,321(48.9%) in organisms other than nematodes, and 862 (31.9%) had no significant match to any sequence in current protein or nucleotide databases. In addition, 1,100 (40.7%) of the sequences were functionally classified using Gene Ontology (GO) hierarchy. Similarity searches of the cluster sequences identified a set of genes with significant homology to genes encoding enzymes that degrade plant or fungal cell walls. The full length sequences of two genes encoding glycosyl hydrolase family 5 (GHF5) cellulases and two pectate lyase genes encoding polysaccharide lyase family 3 (PL3) proteins were identified and characterized.

Conclusion

We have described at least 2,214 putative genes from A. avenae and identified a set of genes encoding a range of cell-wall-degrading enzymes. This EST dataset represents a starting point for studies in a number of different fundamental and applied areas. The presence of genes encoding a battery of cell-wall-degrading enzymes in A. avenae and their similarities with genes from other plant parasitic nematodes suggest that this nematode can act not only as a fungal feeder but also a plant parasite. Further studies on genes encoding cell-wall-degrading enzymes in A. avenae will accelerate our understanding of the complex evolutionary histories of plant parasitism and the use of genes obtained by horizontal gene transfer from prokaryotes.

Background

The complete genome sequence of the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and the wealth of information on gene expression and function for this nematode [1,2] provide an excellent starting point for genome analysis of other nematodes. For less well studied organisms, where whole genome sequencing is currently unlikely, Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) analysis is a cost-effective method for gene discovery. EST analysis has been widely used within the Phylum Nematoda. However, most effort has been focused on plant or animal parasitic nematodes. Free living nematodes, with the notable exceptions of C. elegans, C. briggsae and Pristionchus pacificus, remain under represented in terms of ESTs.

Aphelenchus avenae is a well-known fungal feeding nematode that is currently placed in the superfamily Aphelenchoidea (family Aphelenchidae) [3]. This nematode is ubiquitous in soil and is associated with saprophytic, pathogenic, and mycorrhizal fungi. As a fungal feeder, A. avenae has potential as a bio-control agent against soil-borne fungal plant pathogens [4-8] and, as it has a remarkable ability to survive desiccation; it is also used as a model system for studying anhydrobiosis in animals [9].

Although A. avenae is commonly found in soil samples taken from the rhizospheres of diseased and healthy plants, it is widely considered to be incapable of attacking healthy tissues of higher plants [10,11]. It has been suggested that when the nematode is found in association with plant material this occurs as a result of the nematode feeding on fungi associated with the plant. Alternatively, the finding of A. avenae within plant tissues [12,13] and its demonstrated ability to reproduce on plant callus material [13,14] may show that it can survive in healthy plant tissues and act as a facultative plant parasite. The role, if any, of A. avenae in relation to plant disease therefore remains uncertain.

In a previous study [15], we described the generation, analysis and annotation of over 10,000 ESTs from the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, a pathogenic nematode species which was thought to belong to the same superfamily (Aphelenchoidea) as A. avenae [3] (but see below) and which can feed on live trees as well as on fungi. Genes encoding a range of cell-wall-degrading enzymes including cellulase (β-1,4-endoglucanase) [16], β-1,3-endoglucanase[17], pectate lyase [18] and expansin [19] were subsequently identified and characterized from this nematode. Similar enzymes [20-33] have also been identified and characterized from other plant parasitic nematodes including cyst and root-knot nematodes. These enzymes are produced within the esophageal gland cells of the nematode, secreted through the nematode stylet into host tissues and are thought to play an important role in the host-parasite interaction, allowing invasion and migration of the nematode through plant tissues. The presence of these enzymes is unusual; they are not usually present in animals and it is thought that the genes encoding them may have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer [34,35].

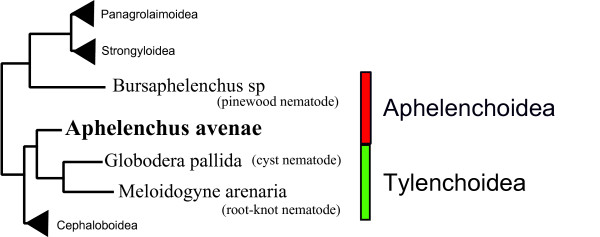

In classical taxonomic classification, A. avenae (family Aphelenchidae) has been placed in the same superfamily (Aphelenchoidea) as B. xylophilus (family Aphelenchoididae) whereas cyst and root-knot nematodes are placed in a different superfamily, the Tylenchoida (family Tylenchida), although the three nematode groups are all placed within the infraorder Tylenchromorpha [3]. However, recent phylogenetic studies using ribosomal DNA suggest that A. avenae is more closely related to cyst and root-knot nematodes than it is to B. xylophilus [36-38]. The current view of the taxonomy of three nematode groups is summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Simplified tree showing relationships of Aphelenchus avenae, Bursaphelenchus and cyst/root-knot nematodes. Recently published phylogenetic tree based on SSU of ribosomal DNA [38] has been adapted for drawing this simplified tree. Taxonomic positions are indicated based on superfamily [3].

Although some of the parasitism genes are common to both superfamiles, Aphelenchoidea (Bursaphelenchus) and Tylenchoidea (cyst and root-knot nematodes), there are also differences between the parasitism genes present in the two nematode groups [3]. For example, Bursaphelenchus and cyst/root-knot nematodes contain endogenous expansins and pectate lyases which appear to have been acquired by a common ancestor via horizontal gene transfer [18,19]. However, the cellulases in the two groups are different. Those present in cyst and root-knot nematodes are from glycosyl hydrolase family 5(GHF5) and are likely to have been acquired from bacteria whereas those in Bursaphelenchus are from GHF45 and appear to have been acquired from fungi [35]. Nothing is currently known about such pathogenicity genes in A. avenae and the presence or absence of such genes in this nematode may shed light onto whether this nematode can act as a plant parasite. In addition, the presence of such horizontally acquired genes in A. avenae may also help reveal the evolutionary history of these genes within nematodes.

To address these issues, we have generated over 5,000 high quality ESTs from a mixed-stage A. avenae cDNA library. We report the identification of genes that could encode enzymes that degrade the cell walls of plants or fungi. We have also analysed the clustered A. avenae sequences using the Gene Ontology (GO) classification system and undertaken comparative analysis with C. elegans and other nematode protein databases.

Results and Discussion

Generation of ESTs from an A. avenae cDNA library

A mixed-stage A. avenae cDNA library (Aamk) was constructed to generate ESTs (Table 1). Sixteen clones were randomly selected and the sizes of the inserts in these clones were assessed after digestion with appropriate restriction enzymes. These insert sizes ranged from 400 to 1,600 base pairs (bp) with an average of 1.1 kilobase pairs (kb). A total of 5,472 cDNA clones were subsequently randomly isolated and sequenced from the 5' end in order to generate ESTs. The sequences were trimmed of vector sequence, adaptor sequence, poly(A) tail and low-quality sequence and filtered for minimum length (150 bp), resulting in a total of 5,076 high quality ESTs. The average length of submitted ESTs was 468 nucleotides (nt).

Table 1.

A. avenae cDNA library, ESTs and clusters statistics

| Titre of cDNA library (pfu/ml) | 1.2 × 105 |

| Average cDNA insert size | 1.1 kb |

| Total cDNA clones picked and sequenced | 5472 |

| Sequences passing quality check | 5076 (93%) |

| Average length | 468 bp |

| Singletons | 2005 |

| Contigs | 695 |

| Total number of clusters | 2700 |

Cluster formation and analysis

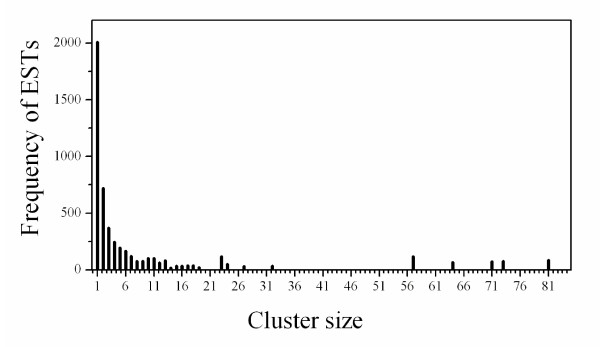

To identify overlapping EST sequences, improve base accuracy and transcript length, and to produce non-redundant EST data for further functional annotation and comparative analysis, the 5,076 ESTs from the A. avenae library were grouped by sequence identity into clusters. Based upon regions of nucleotide identity, EST sequences were merged into contiguous consensus sequences (contigs). 'Contig' member ESTs derive from identical transcripts while 'cluster' members may derive from the same gene but represent different transcript splice isoforms (i.e ESTs form contigs, contigs form clusters). Two thousand seven hundred non-redundant EST clusters were generated from the ESTs (Table 1). In 2,005 cases, clusters consist of a single EST, whereas the largest single cluster contains 81 ESTs (1 case) (Fig. 2). The majority of contigs (650 out of 695) were composed of 2-10 ESTs. 89 clusters were found to contain multiple contig members, revealing potential splice isoforms. By eliminating redundancy during this contig building, the total number of nucleotides used for further analysis was reduced from 2.82 million to 1.61 million. In addition, this process significantly increased the length of assembled transcript sequences from 468 ± 114 nt for submitted ESTs alone to 595 ± 321 nt for contigs. The longest sequence generated also increased from 724 to 2,154 nt.

Figure 2.

Histogram showing the distribution of ESTs from A. avenae by cluster size. For example, there were five clusters of size 23 containing a sum total of 115 ESTs. Distribution of contig sizes is not shown.

Based on the identified clusters 2,700 A. avenae genes were identified, corresponding to a new gene discovery rate of 53% (2,700/5,076). However, 2700 clusters is likely to be an overestimate of the true gene discovery rate, as one gene could be represented by multiple nonoverlapping clusters. Such "fragmentation" has been estimated at 18% using C. elegans as a reference genome [39]. After allowing for such potential fragmentation, we estimated that the A. avenae sequences derived from minimum of 2,214 genes giving a discovery rate of 44% (2,214/5,076). Assuming between 14,000 and 21,000 total genes, the range encompassed by Meloidogyne hapla [40], M. incognita [41] and C. elegans (Wormpep v. 203), the cluster dataset could represent approximately 11-16% of A. avenae genes.

Transcript abundance and highly represented genes

A high level of representation in a cDNA library usually correlates with high transcript abundance in the original biological sample [42], although artifacts of library construction can result in a selection for or against some transcripts. The A. avenae clusters were ranked according to the number of contributing ESTs, and the top 25 clusters are summarized in Table 2. Each of these clusters contained fifteen or more EST copies and represented 16% of the total number of ESTs obtained. Eighteen of the clusters had significant matches to genes with annotated functions based on BLASTX (E < 1e-5) against the non-redundant database, and all of these had homologues in nematodes. Transcripts abundantly represented in the A. avenae library included genes encoding structural proteins (such as actin, collagen, tropomyosin and troponin C) and proteins which carry out core metabolic processes (e.g. cytochrome c oxidase, ATP synthase). Other abundant ESTs included a small heat shock protein and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. The latter enzyme has previously been cloned from the parasitic nematodes, Haemonchus contortus and Ascaris suum [43,44]. Cluster AAC00541, containing 23 ESTs, was similar to an SXP/RAL-2 family protein from the parasitic nematode, Anisakis simplex. Similar genes have previously been characterized from plant parasitic nematodes [45], and individual genes have been shown to be expressed in a range of secretory tissues including the gland cells surrounding the main sense organs (amphids) and the hypodermis.

Table 2.

The most abundantly represented transcripts in the A avenae cDNA library

| Non-redundant GenBank | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Cluster ID | ESTs | Best identity descriptor | Accession | E-value | C. elegans gene |

| 1 | AAC00129 | 81 | Actin [Panagrellus redivivus] | AAM47606 | 0.0 | M03F4.2 |

| 2 | AAC00161 | 73 | Hypothetical protein F42A10.7 [C. elegans] | NP_498341 | 4e-40 | F42A10.7a |

| 3 | AAC00061 | 71 | Small heat shock protein OV25-2 [Onchocerca volvulus] | P29779 | 5e-10 | F08H9.4 |

| 4 | AAC00128 | 64 | Collagen family member (col-144) [C. elegans] | NP_505374 | 1e-25 | B0222.6a |

| 5 | AAC00023 | 57 | Troponin C [C. brenneri] | ACD88888 | 1e-71 | F54C1.7 |

| 6 | AAC00091 | 57 | Tropomyosin [Heligmosomoides polygyrus] | ABV44405 | 2e-82 | Y105E8B.1a |

| 7 | AAC00187 | 32 | Cuticular collagen [Teladorsagia circumcincta] | CAA65506 | 3e-30 | T07H6.3 |

| 8 | AAC00105 | 27 | Hypothetical protein CBG24046 [C. briggsae] | CAE56371 | 2e-66 | F09F7.2a |

| 9 | AAC00123 | 24 | Novel | -- | -- | -- |

| 10 | AAC00255 | 24 | Novel | -- | -- | -- |

| 11 | AAC00048 | 23 | Temporarily assigned gene name family member [C. elegans] | NP_501440 | 1e-141 | T01B11.4 |

| 12 | AAC00088 | 23 | Novel | -- | -- | -- |

| 13 | AAC00109 | 23 | Hypothetical protein CBG15446 [C. briggsae] | XP_001677444 | 3e-43 | ZK721.2 |

| 14 | AAC00321 | 23 | Novel | -- | -- | -- |

| 15 | AAC00541 | 23 | SXP/RAL-2 family protein [Anisakis simplex] | BAF43534 | 2e-14 | ZK970.7 |

| 16 | AAC00269 | 19 | Hypothetical protein CBG02561 [C. briggsae] | XP_001679653 | 3e-08 | ZK84.1a |

| 17 | AAC00121 | 18 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I [Steinernema carpocapsae] | YP_026087 | 1e-153 | MTCE.26 |

| 18 | AAC00143 | 18 | Cuticle preprocollagen [Meloidogyne incognita] | AAC48358 | 9e-22 | F41F3.4 |

| 19 | AAC00163 | 17 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase [Haemonchus contortus] | P29190 | 1e-151 | R11A5.4a |

| 20 | AAC00313 | 17 | ATP synthase subunit family member (atp-2) [C. elegans] | NP_498111 | 1e-149 | C34E10.6a |

| 21 | AAC00112 | 16 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit III [Ascaris suum] | NP_006947 | 7e-70 | MTCE.23 |

| 22 | AAC00295 | 16 | Novel | -- | -- | -- |

| 23 | AAC00024 | 15 | Hypothetical protein CBG21920 [C. briggsae] | XP_001678358 | 2e-21 | R06C7.4a |

| 24 | AAC00265 | 15 | Novel | -- | -- | -- |

| 25 | AAC00148 | 14 | Novel | -- | -- | -- |

a C. elegans homolog has higher probability match than the best GenBank descriptor

Seven of the 25 most abundantly represented transcripts from A. avenae had no significant similarity to any sequence in the non-redundant protein database (Table 2). Since most nematode data are available only as ESTs and therefore not included in the BLASTX analysis, we compared these 7 contigs against dbEST using BLASTN and TBLASTX. However, these searches returned no significant matches (E < 1e-5). We also conducted BLASTN and TBLASTX searches against the non-redundant nucleotide database for these sequences. Six of the clusters did not return any matches from this database but cluster AAC00148 produced a match using TBLASTX analysis (E < 1e-5) (Table 2).

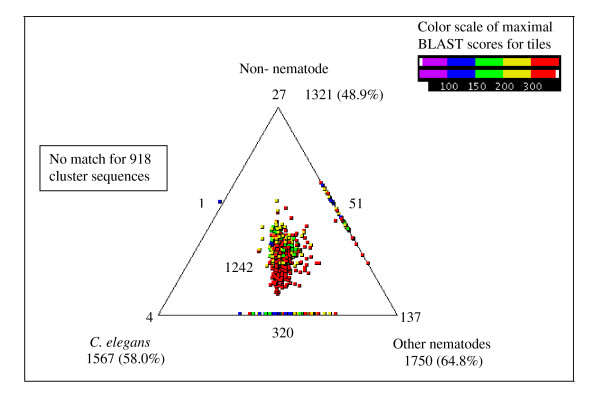

Comparisons to proteins from other species

We compared the 2,700 cluster sequences from A. avenae against three databases containing protein sequences from different organisms. The cluster sequences were compared with protein sequences from (i) C. elegans (WORMPEP v.203 [46]), (ii) other nematodes (available protein sequences and peptides from conceptually translated ESTs), and (iii) organisms other than nematodes (from the NCBI non-redundant protein database) [47]. 66% of the A. avenae clusters (1,782 of 2,700) had matches in one or more of the three databases and these matches were represented using SimiTri [48] (Fig. 3). In the majority of cases where homologies were found (1,242/1,782), matches were found in all three databases surveyed. Gene products in this category are generally widely conserved across metazoans and many are involved in core biological processes. Examination of the individual database searches showed that 1,567 (58.0%) had homologues in C. elegans, 1,750 (64.8%) in other nematodes and 1,321 (48.9%) in organisms other than nematodes. The 918 clusters (34.0%) which had no significant similarity to any sequences in these three protein databases were searched against non-redundant nucleotide and dbEST databases using BLASTN and TBLASTX (employing a cut-off of 1e-05). 56 clusters generated matches in these searches but no matches were obtained for the remaining 862 sequences (31.9%).

Figure 3.

Comparison of A. avenae cluster sequences with C. elegans, other nematodes and non-nematode protein sequence databases using SimiTri. The numbers at each vertex indicate the number of cluster sequences matching only that specific database. The numbers on the edges indicate the number of cluster sequences matching the two databases linked by that edge. The number within the triangle indicates the number of A. avenae genes with matches to sequences in all three databases.

Table 3 shows the 15 gene products with the highest level of conservation (E-value ranging from 0 to e-151) between A. avenae and C. elegans; these include gene products involved in cell structure (for example, actin, UNC-87), protein biosynthesis or regulation (for example, UBQ-1, elongation factor,) and metabolism (for example, enolase, cytochrome c oxidase). Representation of these clusters in the A. avenae EST collection varied from 81 ESTs to 2 ESTs. None of these most conserved gene products were nematode specific. Out of all clusters, 461 (17.1%) had homology only to nematodes, either C. elegans (4), other nematodes (137), or both (320) (Fig. 3). The most conserved (1e-111) of these nematode-specific proteins was a homolog of a serine proteinase inhibitor, previously characterized from C. elegans (K10D3.4) and parasitic nematodes [49,50]. Among the other most conserved nematode-specific clusters were homologs of previously characterized C. elegans structural proteins (for example cluster, AAC01973 matched to a collagen family protein, COL-176) as well as uncharacterized C. elegans hypothetical proteins (for example, cluster, AAC01948 matched C. elegans gene, C34E7.4 which has no known function).

Table 3.

Most conserved nematode genes between A. avenae and C. elegans

| A. avenae cluster | ESTs | Wormpep Accession | C. elegans Gene | Assignment | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAC01067 | 2 | CE01921 | F25B5.4 | UBQ-1, ubiquitin like protein | 0 |

| AAC00578 | 8 | CE18826 | H28O16.1 | ATP synthase alpha and beta subunits | 0 |

| AAC00675 | 6 | CE36954 | T21B10.2 | ENOL-1, enolase | 0 |

| AAC00196 | 10 | CE33098 | F46H5.3 | Kinase, protein-id: AAB37022.2 | 0 |

| AAC00129 | 81 | CE12358 | MO3F4.2 | ACT-4, actin 4 | 0 |

| AAC00222 | 7 | CE01270 | R03G5.1 | ELF-4, elongation factor 1-alpha | 0 |

| AAC00358 | 2 | CE31915 | F25B5.4 | UBQ-1, ubiquitin like protein | 1e - 178 |

| AAC00334 | 11 | CE36924 | F08B6.4 | UNC-87, calponin | 1e - 177 |

| AAC00339 | 4 | CE02477 | C14F11.1 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 1e - 166 |

| AAC00183 | 3 | CE07458 | T01C8.1 | AAK2, protein kinase | 1e - 160 |

| AAC01744 | 3 | CE18971 | T27E9.7 | ABCF-2, ABC transporter | 1e - 160 |

| AAC00121 | 18 | CE35350 | MTCE.26 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 | 1e - 153 |

| AAC00163 | 17 | CE36360 | R11A5.4 | Protein-id:CAF31483.1 | 1e - 152 |

| AAC00313 | 17 | CE29950 | C34E10.6 | ATP-2, ATP synthase beta subunit | 1e - 151 |

| AAC00262 | 8 | CE39807 | Y105C5B.28 | GLN-3, glutamine synthetase | 1e - 151 |

The 137 cluster sequences where homologs were present only in other nematodes were further categorized based on their BLAST (BLASTX and TBLASTX) results (Additional file 1). Matches were found in plant parasitic, animal parasitic and free living nematodes. 24.8% of sequences (34 of 137) had homology only to sequences from plant parasitic nematodes. Some of these sequences were similar to previously characterized cell-wall-degrading enzymes, which are known to be involved in the parasitism process of these nematodes. For example, cluster, AAC01592 matched an expansin-like protein from B. xylophilus [19] and cluster, AAC02968 matched a β-1,4-endoglucanase precursor from Globodera rostochiensis [20]. Further analysis of some of the cell-wall-degrading enzymes present in A. avenae is presented below.

Identification of transcripts similar to stress-response genes related to desiccation

BLASTX (E < 1e-5) searches of A. avenae cluster sequences against nr protein databases allowed identification of genes that can encode proteins or enzymes important in providing protection against desiccation or other environmental-stress (Additional file 2). One notable observation was the presence of sequences similar to late embryonic abundant (LEA) proteins, which are known to be associated with tolerance to water stress resulting from desiccation [9]. Protein aggregation during desiccation is likely to be a major potential hazard for anhydrobiotes; LEA proteins may act as molecular chaperones or molecular shields and play an important role in the prevention of this aggregation [51]. Thirteen ESTs, distributed in three clusters, (AAC00729, AAC00888, and AAC01781) were identified as having significant similarity to LEA proteins. Cluster, AAC01781 which was identified as a singleton matched a previously characterized LEA protein from desiccated A. avenae [9]. In addition, we also identified multiple copies of cytochrome P450, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione S-transferase, enzymes involved in protection against oxidative damage. Desiccation stress of nematodes caused significant up-regulation of transcripts encoding these genes [52,53].

Functional classification based on gene ontology

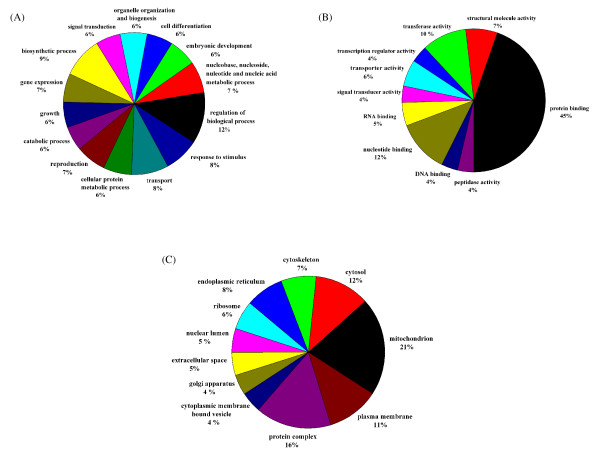

Gene Ontology (GO) has been used widely to predict gene function and classification [54]. BLAST2GO [55,56], a universal, web-based annotation tool was used to assign GO terms for the A. avenae cluster sequences, extracting them from each BLAST hit against Swiss-Prot obtained by mapping to extant annotation associations. 1222 sequences out of 2,700 did not retrieve any BLAST results within the set E-value threshold (< 1e-5). Mapping of GO terms and annotation were not possible for 173 and 205 sequences, respectively. The remaining 1,100 (40.7%) sequences were successfully annotated and mapped to one or more of the three organizing principles of GO: biological process, molecular function and cellular component. The matches obtained from this analysis are summarized in Figs 4A-4C.

Figure 4.

Summary of the Gene Ontology annotation as assigned by BLAST2GO. (A) Most represented GO terms (based on number of represented sequences) of the main category "biological process"; (B) Most represented GO terms of the main category "molecular function (C) Most represented GO terms of the main category "cellular component". Multi-level pie charts were generated using the sequence cut-offs 140, 50 and 40 for "biological process", "molecular function" and "cellular component", respectively.

1,003 of the A. avenae cluster sequences generated matches in the "molecular function" class, 933 in the "biological process" class and 924 in the "cellular component" class. Within the "biological process" class the "regulation of biological process (GO:0050789)", "biosynthetic process (GO:0009058)" and "transport (GO:0006810)" categories were the most represented followed by "response to stimulus (GO:0050896) ", based on the annotation assigned by BLAST2GO (Fig. 4A). Within the "molecular function" class the "protein binding (GO:0005515)" term is the most represented followed by "nucleotide binding (GO:0000166)" and "transferase activity (GO:0016740)" (Fig. 4B). Many cluster sequences encoding ribosomal proteins as well as highly expressed genes coding for structural molecules (such as actin) and regulatory molecules (such as transcription factors) are assigned to the "protein binding" term. Since those clusters are abundantly present in the dataset, this may cause overrepresentation of the "protein binding" term. Within the "cellular component" class the "mitochondrion (GO:0005739)" is the most highly represented (Fig. 4C). A complete listing of GO mappings assigned for the A. avenae cluster sequences is provided in Additional file 3.

Identification of transcripts encoding cell-wall-degrading enzymes

BLASTX analysis allowed us to identify various genes with significant similarity to genes encoding enzymes which degrade plant and fungal cell walls (Table 4). The plant cell-wall-degrading enzymes that were identified included cellulase, pectate lyase, polygalacturonase and expansin, while transcripts encoding fungal cell-wall-degrading enzymes included β-1,3-endoglucanase and chitinase.

Table 4.

A. avenae transcripts similar to plant or fungal cell-wall-degrading enzymes

| Enzyme name | Cluster ID | ESTs | Non-redundant GenBank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best identity descriptor | Accession | E-value | |||

| Cellulase | AAC00199 | 2 | β-1,4-endoglucanase [Pratylenchus penetrans] | BAB68522 | 1e-26 |

| AAC00418 | 1 | β-1,4-endoglucanase [P. penetrans] | BAB68522 | 1e-22 | |

| AAC00801 | 2 | β-1,4-endoglucanase precursor [Globodera rostochiensis] | AAC63989 | 5e-49 | |

| AAC00947 | 1 | β-1,4-endoglucanase [P. penetrans] | BAB68522 | 6e-15 | |

| AAC01152 | 6 | β-1,4-endoglucanase-1 precursor [Radopholus similis] | ABV54446 | 1e-79 | |

| AAC02961 | 1 | β-1,4-endoglucanase-1 precursor [Heterodera glycines] | AAC48327 | 2e-45 | |

| AAC02968 | 1 | β-1,4-endoglucanase precursor [G. rostochiensis] | AAC48325 | 3e-11 | |

| AAC03021 | 1 | β-1,4-endoglucanase precursor [G. rostochiensis] | AAD56392 | 2e-08 | |

| Pectate lyase | AAC01467 | 1 | Pectate lyase [Bursaphelenchus mucronatus] | BAE48373 | 3e-38 |

| AAC01649 | 1 | Pectate lyase [B. mucronatus] | BAE48373 | 1e-59 | |

| AAC02466 | 1 | Putative secreted lyase [Streptomyces ambofaciens] | CAJ90085 | 6e-25 | |

| AAC02527 | 1 | Pectate lyase [B. mucronatus] | BAE48373 | 4e-13 | |

| AAC02949 | 1 | Pectate lyase [B. mucronatus] | BAE48373 | 6e-42 | |

| AAC03048 | 1 | Pectate lyase [B. mucronatus] | BAE48373 | 4e-43 | |

| Polygalacturonase | AAC02157 | 1 | Extracellular polygalacturonase [Aspergillus clavatus] | XP_001272239 | 3e-44 |

| AAC02706 | 2 | Polygalacturonase precursor [A. parasiticus] | P49575 | 1e-37 | |

| Expansin | AAC01185 | 2 | Expansin-like protein [B. xylophilus] | BAG16537 | 5e-42 |

| AAC01434 | 1 | Expansin-like protein [B. xylophilus] | BAG16537 | 5e-25 | |

| AAC01592 | 1 | Expansin-like protein [B. xylophilus] | BAG16537 | 8e-25 | |

| AAC02804 | 1 | Expansin-like protein [B. xylophilus] | BAG16537 | 5e-51 | |

| 1,3-Glucanase | AAC00494 | 2 | Glcosyl hydrolase 16 precursor [Pedobacter sp.] | ZP_02027413 | 8e-42 |

| Chitinase | AAC00552 | 2 | Conserved hypothetical protein [Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus] | XP_001849531 | 7e-09 |

| AAC01706 | 2 | Chitinase family member [C. elegans] | NP_508588 | 3e-45 | |

| AAC02660 | 1 | Putative chitinase [Ascaris suum] | AAK93964 | 4e-75 | |

Eight cellulase genes were present in 8 different A. avenae clusters and in all cases homologues were found in other plant parasitic nematodes. One cellulase gene (AAC01152) was identified as a contig of six individual ESTs. Two clusters (AAC00199 and AAC00801) contained 2 ESTs each and remaining cellulase clusters were present as a singleton. Two types of pectin degrading enzymes: pectate lyase and polygalacturonase were identified (Table 4). While all transcripts encoding pectate lyase genes were identified as singletons, polygalacturonase clusters contained either single or two individual ESTs. The features of the sequences of cellulase and pectate lyase are discussed in more detail below.

In addition to the plant cell-wall-degrading enzymes, we identified genes encoding expansin-like proteins in the A. avenae dataset. Expansins and expansin-like proteins have recently been described in several plant parasitic nematodes [19,31-33] and it is thought that these proteins disrupt non-covalent bonds in the plant cell wall, enhancing the activity of other enzymes such as cellulases. All four expansin-like transcripts were identified as a best match with the expansin genes from the B. xylophilus [19].

Two different types of genes, β-1,3-endoglucanase and chitinase, that could encode enzymes, important in degradation of the fungal cell wall were identified. A gene encoding a β-1,3-endoglucanase has been cloned and characterized from B. xylophilus [17] and is thought to aid fungal feeding in this nematode. Chitinase, an enzyme responsible for breakdown of β-1,4-glycosidic bonds within chitin, has been found in wide ranges of nematodes. Since chitin is known to be present in the eggshell [57] and the microfilarial sheath [58] of nematodes, it has been suggested that chitinases have a role in remodeling processes during the molting of filariae and in the hatching of larvae from the eggshell [59,60]. However, the existence of large families of chitinases in the free-living nematode C. elegans suggests that these enzymes may also fulfill other functions [61]. In the plant parasitic nematode, Heterodera glycines, chitinase was found to be expressed in the subventral oesophageal gland cells of the parasitic stages of this nematode, suggesting a role in parasitism but not in hatching [62]. The fungal feeding plant parasitic B. xylophilus also contains chitinase [15]. Since β-1,3-glucan and chitin are the two major structural polysaccharides of the fungal cell-wall, it is possible that fungal feeding nematodes like B. xylophilus and A. avenae secrete these enzymes in order to metabolize or soften the fungal cell wall as part of the feeding process.

Characterisation of genes encoding cellulases and pectate lyases; analysis of sequences, phylogentics and expression analysis

Cellulase and pectate lyase have been identified and characterized in a wide range of plant parasitic nematodes [16,18,20-29]. The presence of genes encoding cell-wall-degrading enzymes in A. avenae opens up a new avenue for further molecular studies aimed at understanding their functional role in this nematode and investigating the origin and evolution of these genes within the Nematoda. We therefore cloned the full length cDNA and genomic sequences of two putative cellulases (named Aa-eng-1 and Aa-eng-2) and two putative pectate lyases (named Aa-pel-1 and Aa-pel-2) and compared these sequences to those from other plant parasitic nematodes.

The full-length sequences of the cellulases were identified from two plasmid clones whose EST sequences are part of cluster, AAC001152 (Table 4). Although, six individual ESTs, form a contig to represent this cluster, one EST was selected as it showed a slightly different nucleotide sequence from the other five ESTs. Two different plasmid clones containing the full length cDNA sequences of the cellulases were subsequently selected and sequenced using the specific primers listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Primers used in the analysis of cell-wall-degrading enzymes

| Primers | Sequence (5' to 3') | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Eng1-0F | CTCTACGGGATGAAGTGTCT | In situ hybridization, amplification of cDNA and gDNA of Aa-eng-1 and Aa-eng-2 |

| Eng1-0R | TTAACAAAAGCGGTACAAG | In situ hybridization, amplification of cDNA and gDNA of Aa-eng-1 and Aa-eng-2 |

| Eng1-1F | GCTCAAGGTCGTCGTCGAGG | Sequencing of cDNA and gDNA of Aa-eng-1 and Aa-eng-2 |

| Eng1-10F | GGCATCTCCGAGGCCGACG | Sequencing of gDNA of Aa-eng-1 and Aa-eng-2 |

| Eng1-10R | CTTGCCGTACTCCTGCGCGAT | Sequencing of gDNA of Aa-eng-1 and Aa-eng-2 |

| Eng2-20R | GCTACTTTGCTGGTCCACGT | Sequencing of gDNA of Aa-eng-2 |

| Pel1-0F | TCCGACGACAACGTCAACCA | In situ hybridization, amplification of cDNA and gDNA of Aa-Pel-1 |

| Pe11-0R | AAACCCTCAGCATGTTTGATAC | In situ hybridization, amplification of cDNA and gDNA of Aa-Pel-1 |

| Pel1-1F | TCGAGAACGTCTGGTGGGA | Sequencing of cDNA and gDNA of Aa-Pel-1 and Aa-Pel-2 |

| Pe11-10F | CTTGGAGGTACGCTTCGTACG | Sequencing of gDNA of Aa-Pel-1 |

| Pe11-10R | TGACCTTCTTCGCCGCAGTG | Sequencing of gDNA of Aa-Pel-1 |

| Pe11-20F | GAAATGGTACGATTAGTCCTG | Sequencing of gDNA of Aa-Pel-1 |

| Pe12-0F | TCAGTCGGACAGCTTTTCCTC | Amplification of cDNA and gDNA of Aa-Pel-2 |

| Pe12-0R | AGCAGGCATTTCGTCGACAC | Amplification of cDNA and gDNA of Aa-Pel-2 |

| Pe12-10F | CGAGATGGCACGGGTGCCGA | Sequencing of gDNA of Aa-Pel-2 |

| Pe12-10R | CGTAGCGAGAAATTTTCGATCA | Sequencing of gDNA of Aa-Pel-2 |

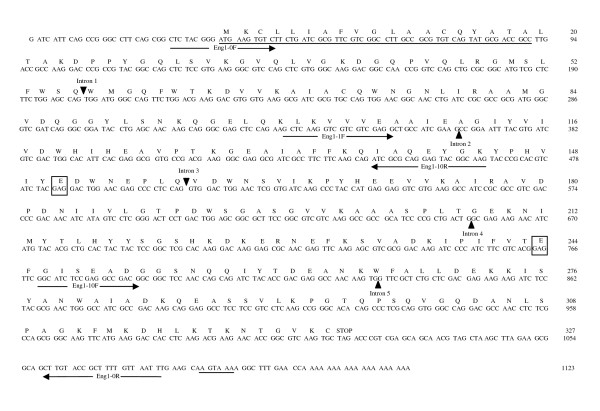

The Aa-eng-1 cDNA was 1,104 bp in length (excluding the polyA tail) and included a 981-bp open reading frame (ORF) that could encode a protein of 327 amino acids with an ATG start codon at position 35 and a TGA stop codon at position 1,016 (Fig. 5). The complete cDNA of Aa-eng-2 was 1,107 bp in length and also contained a potential ORF of 327 amino acids with an ATG start codon at position 35 and TGA stop codon at 1,016. A signal peptide of 19 amino acids is predicted by SignalP [63] at the N terminus of the deduced AA-ENG-1 and AA-ENG-2 polypeptides. The predicted molecular masses of the putative mature proteins were 34.130 kDa and 34.059 kDa respectively and the theoretical pI value was 6.2 for both proteins. The AA-ENG-1 and AA-ENG-2 proteins contained a catalytic domain homologous to GHF5 β-1,4-endoglucanases as predicted by PRODOM [64]. The deduced amino acid sequences showed highest similarity with the GHF5 endoglucanase from the migratory plant parasitic nematode Radopholus similis (GenBank Accession No. [ABV54446]). The highest non-nematode similarities of both AA-ENG-1 and AA-ENG-2 were with the β-1,4-endoglucanase from Cytophaga hutchinsoni (cellulolytic gliding bacterium; GenBank Accession No. [YP_678708]). AA-ENG-1 and AA-ENG-2 share 99% identity in their amino acid sequences.

Figure 5.

Aa-eng-1cDNA sequence and predicted amino acid sequences. The predicted signal peptide for secretion and polyadenylation signal sequence are underlined. Predicted positions of the five intron sequences identified are indicated by darkened triangles. Primers used for obtaining the full length cDNA sequence and genomic amplification are indicated by arrows. The amino acids within the boxes represent the predicted active site residues.

Genomic clones of Aa-eng-1 and Aa-eng-2 were obtained by PCR amplification using gene-specific primers (Table 5) and genomic DNA as template. The Aa-eng-1 and Aa-eng-2 genomic DNA products were1,518 bp and 1,522 bp long respectively from the ATG to the stop codon. The position of exon/intron boundaries of the genomic sequences were determined by aligning the genomic sequences with the corresponding cDNA sequences. All introns were bordered by canonical cis-splicing sequences [65]. Five introns were identified in Aa-eng-1 (Fig. 5) of which four introns were small (40 bp to 85 bp) a feature commonly found in nematodes [66]. Only the first intron was larger (319 bp). Five introns were also identified in Aa-eng-2. The first intron was 337 bp long and the length of remaining four introns ranged from 40 to 72 bp. The intron positions of Aa-eng-1 and Aa-eng-2 genes were identical to each other.

Sequence alignment of the two endoglucanases from A. avenae with GHF5 endoglucanases from nematodes and other organisms revealed that both AA-ENG-1 and AA-ENG-2 possess a consensus pattern of GHF5 endoglucanases in their primary amino acid sequences in which two glutamic acids residues are the predicted proton donor and mucleophile/base of the catalytic site (Fig. 5) which is also true for all previously described nematode GHF5 endoglucanases. In addition to the catalytic domain some of these proteins contain a cellulose binding domain (CBD) joined to the catalytic domain through a linker peptide. The GHF5 endoglucanase genes isolated from plant parasitic nematodes have also different structures: all have a signal peptide and catalytic domain, some have an additional linker and CBD and others only have a linker but no CBD [25,67]. However, neither peptide linkers nor CBD domains were present in the two GHF5 endoglucanases isolated from A. avenae. Expansins from cyst nematodes have also been shown to contain a CBD, but no such domains were predicted in other sequences within the EST dataset, including the putative expansins.

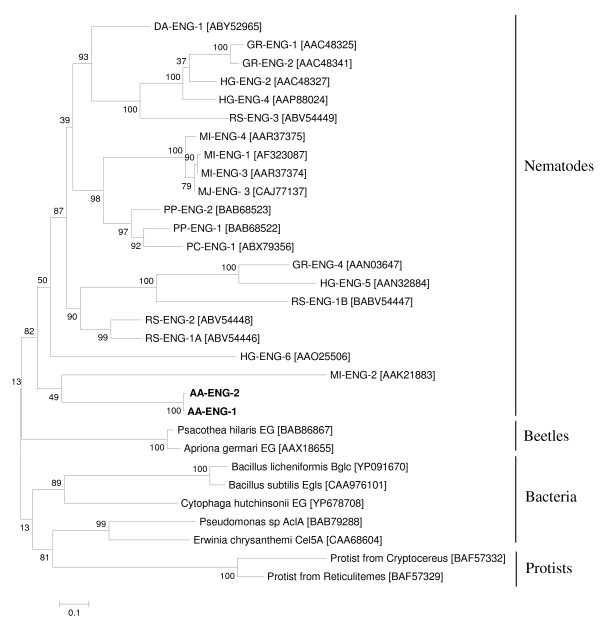

A phylogenetic tree was generated from an alignment of the β-1,4-endoglucanase protein sequences from AA-ENG-1, AA-ENG-2, cyst and root-knot nematodes, the migratory plant-parasitic nematodes R. similis, Pratylenchus penetrans, Pratylenchus coffeae and Ditylenchus africanus and GHF5 cellulases from phytophagous beetles, bacteria and protists (Fig. 6). AA-ENG-1 and AA-ENG-2 clustered into a larger group of protein sequences including all nematode GHF5 cellulases, indicating that A. avenae cellulases are closely related to those of the Tylenchida. This analysis supports the idea that all nematode GHF5 cellulases evolved from a GHF5 sequence acquired by a common ancestor of this group.

Figure 6.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree of GHF5 catalytic domains based on the protein sequences using the maximum likelihood method. The GHF5 proteins from A. avenae (AA-ENG-1 and AA-ENG-2) are labeled in bold. GenBank accession numbers of GHF5 proteins from Meloidogyne incognita (MI-ENG-1, MI-ENG-2, MI-ENG-3 and MI-ENG-4), Pratylenchus penetrans (PP-ENG-1 and PP-ENG-2), Pratylenchus coffeae (PC-ENG-1), Radopholus similis (RS-ENG-1A, RS-ENG-1B, RS-ENG-2 and RS-ENG-3), Globodera rostochiensis (GR-ENG-1, GR-ENG-2 and GR-ENG-4), Heterodera glycines (HG-ENG-2, HG-ENG-4, HG-ENG-5 and HG-ENG-6), Ditylenchus africanus (DA-ENG-1), beetles, bacteria and protists are indicated in brackets. The bootstrap values are calculated from 1000 replicates. The scale bar represents 10 substitutions per 100 amino acid positions.

The β-1,4-endoglucanases are the largest family of cell-wall-degrading enzymes that have been identified in parasitic nematodes to date. Over the last decade, a large number of GHF5 endoglucanases have been identified and extensively studied in plant parasitic Tylenchida including cyst and root-knot nematodes [20-25]. Genes encoding β-1,4-endoglucanases have also been found in Bursaphelenchus spp but these enzymes are most similar to GHF45 cellulases from fungi [16]. The presence of GHF5 cellulases within A. avenae (as opposed to GHF45 cellulases) provides further support for the suggestion that this nematode is more closely related to the Tylenchida than to Bursaphelenchus and its relatives.

Although the presence of GHF5 cellulases within A. avenae can be readily explained given the phylogenetic arguments above, the presence of a β-1,3-endoglucanase is more surprising. These enzymes act to metabolise the fungal cell wall and have been previously described in Bursaphelenchus spp. Such genes are not usually present in animals and it was suggested that the Bursaphelenchus genes were acquired by horizontal gene transfer from bacteria [17].

No such genes are present in root-knot nematodes (for which two genome sequences are available) or other Tylenchida. It is possible that a fungal feeding common ancestor of Aphelenchoidea and Tylenchida possessed this gene but that more "advanced" plant parasites have subsequently lost it. Further sequencing within both nematode groups is required to resolve this issue.

All the transcripts potentially encoding pectate lyases were identified as singletons (Table 4). Two full-length cDNA sequences of pectate lyases, designated Aa-pel-1 and Aa-pel-2, were identified from the plasmid clones corresponding to the cluster IDs AAC01649 and AAC03048 respectively. The complete cDNA of Aa-pel-1 was 821 bp in length and contained an ORF of 247 amino acids with a putative ATG start codon at position 30 and TAA stop codon at position 771. A signal peptide of 18 amino acids is predicted by SignalP [63] at the N-terminus of the putative AA-PEL-1 amino acid sequence. The mature protein has a predicted molecular mass of 24.250 kDa and theoretical pI of 8.93.

The full-length Aa-pel-2 cDNA was 838 bp long and contained an ORF of 249 bp with an ATG start codon at position 31 and a TAA stop codon at position 778. An N-terminal signal sequence of 19 amino acids predicted by SignalP [63]. The molecular mass and theoretical pI value of the putative AA-PEL-2 protein were 24.329 kDa and 9.12 respectively. AA-PEL-1 has 61% identity to AA-PEL-2.

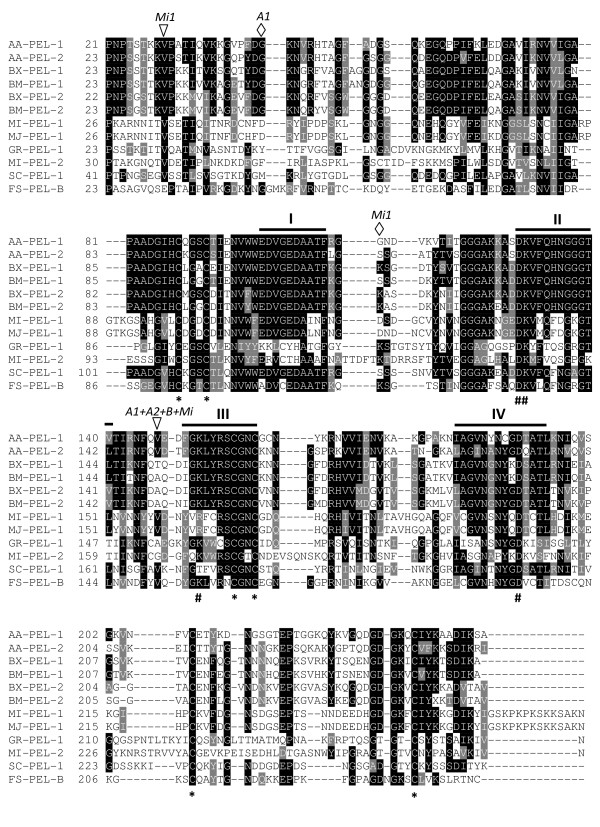

To obtain genomic sequences, the entire coding regions of Aa-pel-1 and Aa-pel-2 gene were amplified from A. avenae gDNA using gene specific primers (Table 5). Analysis of these sequences showed that the Aa-pel-1 and Aa-pel-2 genes were 1,860 and 1,221 bp long respectively from the ATG to the stop codon. Two introns (468 bp and 651 bp) were identified in Aa-pel-1 whereas Aa-pel-2 contained only one intron (690 bp) (Fig. 7). All introns were bordered by canonical cis-splicing sequences [65]. The position of the second intron of Aa-pel-1 was identical to the intron in Aa-pel-2.

Figure 7.

Multiple sequence alignment of A. avenae pectate lyase protein sequences (AA-PEL-1 and AA-PEL-2) with the sequences of pectate lyases from plant parasitic nematodes, bacterium, and a fungus. BX-PEL-1 [BAE48369], BX-PEL-2 [BAE48370] from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus; BM-PEL-1 [BAE48373], and BM-PEL-2 [BAE48375] from Bursaphelenchus mucronatus; MI-PEL-1 [AAQ09004] and MI-PEL-2 [AAQ97032] from Meloidogyne incognita; MJ-PEL-1 [AAL66022] from Meloidogyne javanica; GR-PEL-1 [AAF80747] from Globodera rostochiensis; SC-PEL-1 [NP625403] from Streptomyces coelicolor and FS-PEL-B [AAA8738] from Fusarium solani. Identical residues are highlighted in black and functionally conserved are in gray. Black bars (I to IV) indicate the conserved regions characteristic of PL3 pectate lyases. Very highly conserved charged residues are indicated beneath the alignment by a number symbol (#), while an asterisk (*) indicates conserved cysteine residues. The positions of the intron in AA-PEL-1 and AA-PEL-2 are indicated by A1 and A2 respectively, that in BX-PEL-1/2 and BM-PEL-1/2 by B, and those in MI-ENG-1 by Mi1. Triangles and diamonds represent phase 0 and 1 introns, respectively.

The intron position in the A. avenae genes (Aa-pel-1 and Aa-pel-2) were compared with other nematode pectate lyase genes. The pectate lyase genes from Bursaphelenchus species (Bx-pel-1/2 and Bm-pel-1/2) each have one intron in their coding region at the same position [18]. This position is also identical to the common intron position of the A. avenae genes (Fig. 7). Moreover, one of the three introns of Mi-pel-1 from M. incognita is at the same position as that in the A. avenae and Bursaphelenchus genes. Gr-pel-1 from G. rostochiensis has six introns and Mi-pel-2 from M. incognita has two introns. Gr-pel-1 and Mi-pel-2 share two intron positions but none of the introns of these genes have the same position as that in the A. avenae genes (not shown).

A protein homology search using the deduced amino acid sequences of AA-PEL-1 and AA-PEL-2 using BLASTP indicated high similarity to the pectate lyases belonging to the the polysaccharide lyase family 3 (PL3) from plant parasitic nematodes, bacteria and fungi. Multiple sequence alignment of AA-PEL-1 and AA-PEL-2 with the best matches confirmed that both A. avenae sequences contained the four highly conserved regions characteristic of PL3 pectate lyases in bacteria and fungi as well as 8-10 cysteine residues and four charged residues (Fig. 7) that are potentially involved in catalysis [26,68]. AA-PEL-1 and AA-PEL-2 were most similar to the pectate lyases (BX-PEL1/2 and BM-PEL1/2) from the pinewood nematodes B. xylophilus and B. mucronatus (52 to 59% identity for the AA-PEL-1 and 53 to 63% identity for AA-PEL-2) [18]. A. avenae sequences shared 23 to 33% identity with pectate lyases (MI-PEL-1, MI-PEL-2, MJ-PEL-1 and GR-PEL-1) from cyst and root-knot plant parasitic nematode spp [28,29], and 39 to 45% identity with the sequences from two microbes (Fig. 7).

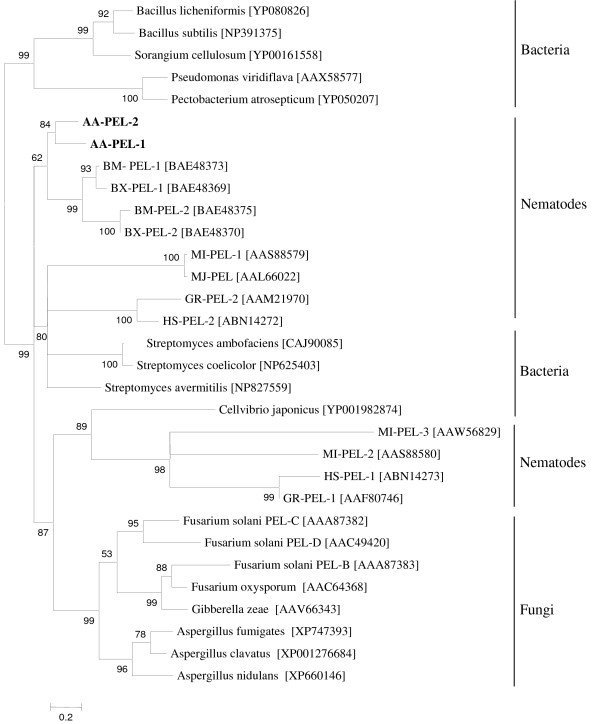

A phylogenetic tree was generated from an alignment of A. avenae pectate lyase sequences with selected proteins belonging to PL3 from bacteria, fungi, and nematodes using the maximum likelihood method (Fig. 8). Both Aa-pel-1 and Aa-pel-2 were clustered with the Bursaphelenchus genes. Other nematode sequences were not monophyletic but were clustered into distinct clades.

Figure 8.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree of selected polysaccharide lyase family 3 proteins generated using maximum likelihood analysis. The PL3 proteins from A. avenae (AA-PEL-1 and AA-PEL-2) are labeled in bold. GenBank accession numbers of PL3 proteins from Bursaphelenchus mucronatus (BM-PEL-1 and BM-PEL-2), Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (BX-PEL-1 and BX-PEL-2), Meloidogyne incognita (MI-PEL-1, MI-PEL-2 and MI-PEL-3), Meloidogyne javanica (MJ-PEL), Globodera rostochiensis (GR-PEL-1 and GR-PEL-2), Heterodera schachtii (HS-PEL-1 and HS-PEL-2), bacteria and fungi are indicated in brackets. The bootstrap values are calculated from 1000 replicates. The scale bar represents 20 substitutions per 100 amino acid positions.

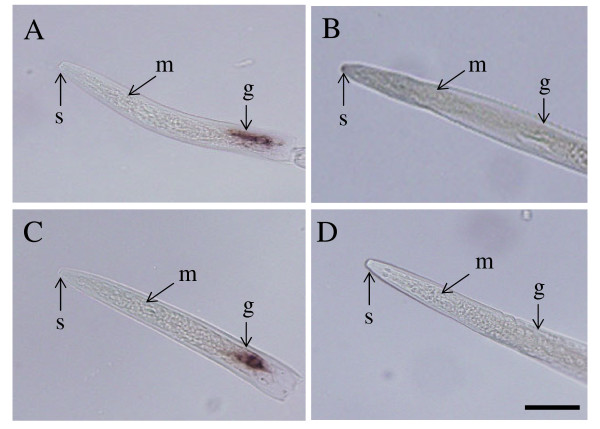

The pectate lyase genes from A. avenae are more similar to the Bursaphelenchus genes compared to those from cyst and root-knot nematodes (Figs. 7 and 8). The identical position of the common intron of the A. avenae genes (Aa-pel-1 and Aa-pel-2) and introns within pectate lyase genes from Bursaphelenchus and M. incognita (Fig. 7) suggests that pectate lyase genes from a wide range of plant parasitic nematodes have the same origin. To determine which A. avenae cells express GHF5 endoglucanases and pectate lyases, in situ mRNA hybridisation was performed (Fig. 9). Digoxigenin-labeled antisense probes generated from Aa-eng-1 and Aa-pel-1 specifically hybridized with the transcripts in the esophageal gland cells of A. avenae (Figs. 9A and 9C). Staining was observed in juvenile and adult nematodes rather than being restricted to a specific life stages. No hybridisation was observed with the control (sense) cDNA probes of Aa-eng-1 or Aa-pel-1 (Figs. 9B and 9D).

Figure 9.

Localization of Aa-eng-1 and Aa-pel-1 transcripts in the esophageal gland cells of A. avenae by in situ hybridisation. Nematode sections were hybridized with antisense (A) and sense (B) Aa-eng-1 digoxigenin-labeled cDNA probes. Hybridisation was also carried out with digoxigenin-labeled antisense (C) and sense (D) Aa-pel-1 cDNA probes. G, esophageal glands; S, stylet; M, metacorpus. The bar indicates a length of 20 μm.

As a part of the complex process of parasitism, a wide range of plant parasitic nematodes use endogenous β-1,4-endoglucanases and pectate lyases to degrade two abundant constituents of the plant cell wall and thus facilitate their migration through host tissues. The presence of signal peptides in the deduced amino acid sequences of the endoglucanases and pectate lyase from A. avenae coupled with their expression in the esophageal glands suggest that both enzymes have a similar role in A. avenae. The presence of such genes in A. avenae suggests that this nematode can enter and migrate through plant tissues and may also be able to feed on plant cell contents. This is backed up by the observation that A. avenae is known to feed on plant tissue in culture [13,14]. A. avenae may therefore have a wide ranging diet that includes fungi and plant tissues. This, coupled with the position of this nematode as a basal member of a clade that includes a wide range of plant parasitic nematodes, provides further support for the idea that plant parasitism has evolved from fungal feeding and suggests that A. avenae, may be a very primitive plant feeder.

Conclusion

The 5,076 ESTs identified in this study represent the first attempt to define the A. avenae gene set and represents over 2,200 genes. This collection of ESTs represents a starting point for studies in a number of different fundamental and applied areas. A summary of the assignment of nonredundant ESTs to functional categories as well as their relative abundance are listed and discussed. A substantial number of putative Aphelenchus-specific genes were found that do not share similarity with known genes and some of these may be highly expressed, based on their abundance in the EST dataset. The presence of genes encoding a battery of cell-wall-degrading enzymes in A. avenae and their similarities with the genes from other plant parasitic nematodes suggest that this nematode can act not only as a fungal feeder but also as a plant parasite. The gene structures of GHF5 cellulase and PL3 pectate lyase from A. avenae, their phylogenetics and comparative analyses with similar genes from other parasitic nematodes provides information that helps understand the evolutionary origins of these genes within the Nematoda. Further studies on genes encoding cell-wall-degrading enzymes in A. avenae will accelerate our understanding of the complex evolutionary histories of plant parasitism and the use of genes obtained by horizontal gene transfer from prokaryotes.

Methods

Biological material

The AaF1 isolate of A. avenae was cultured on fungi, Botrytis cinerea for 2-3 weeks at 25°C and then extracted for 3 h at 25°C using the modified Baermann funnel technique [69]. Separated, mixed life stage, nematodes were cleaned by flotation on a 30% (wt/vol) sucrose solution followed by three washes with 0.5× PBST [70]. Nematodes were stored at -80°C until use.

Isolation of total RNA, cDNA synthesis and cDNA library construction

Total RNA from mixed stage A. avenae was isolated using Sepasol (Nakalai). Analysis of the total RNA on a denaturing agarose gel showed a smear from 50 to 3,000 bp with two distinct bands of ribosomal RNA. Poly(A)+ RNA was extracted from total RNA using a FastTrack® MAG micro mRNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using the SMART PCR cDNA amplification method (Clontech) with a NotI oligo-dT primer (5' AACTGGAAGAATTCGCGGCCGCAGGAATTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT). SalI/SmaI adaptors (Takara) were added to double stranded cDNA which was digested with NotI and size fractionated using a cDNA Size Fractionation Column to remove small cDNA (< 500 bp) (Invitrogen). The appropriate fractions containing cDNA were pooled and ethanol precipitated. Inserts were directionally cloned into NotI and SalI sites of the pSPORT1 vector, and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α cells. The cDNA library was designated as Aamk.

EST generation

Individual transformants (n = 5,472) from the plasmid library were picked into 96 well plates containing 0.5 ml of LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. A small aliquot of each culture was stored at -80°C after being mixed with same volume of 25% glycerol in LB. Plasmid DNA was isolated and purified using FB glass fiber plates (Millipore) using the glass bead method described in [71]. cDNA inserts were sequenced from the 5' end using the M13-T7 primer (5'-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3') and the BigDye terminator ver. 3.1 kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Raw sequence trace data from the 3100 sequencer were processed in an automated pipeline, the trace2dbEST package [72]. Before submitting them to the public database (DDBJ), sequences were processed to assess quality, remove vector sequence, contaminants and cloning artifacts and to identify BLAST similarities.

Clustering and sequence analysis

Clustering was performed using PartiGene, a software pipeline designed to analyze and organize EST data sets [72]. Sequences were clustered into groups (putative genes) on the basis of sequence similarity using CLOBB [73]. Clusters were assembled to yield consensus sequences using Phrap (P. Green, unpublished data). Each consensus sequence was subjected to BLAST analysis against the GenBank non-redundant protein database.

Comparative analyses were performed with cluster sequences as queries versus multiple databases including C. elegans Wormpep v.203 protein database [46]. Protein databases for 'other nematode' and 'non-nematodes' were generated in-house for similarity searches. The 'other nematode'database contained all available protein sequences from nematodes other than C. elegans and A. avenae as well as nematode ESTs in GenBank (April 30, 2009), translated into peptide sequences (in TBLASTX analysis). The 'non-nematode' database comprises amino acid sequences from the complete non-redundant protein database (April 30, 2009) excluding those from nematodes. Homologues to cluster sequences were identified via comparisons against WormBase and non-redundant protein databases using the BLASTX algorithm. The TBLASTX algorithm with default parameters was used to compare the A. avenae cluster sequences to ESTs from other nematodes. Each cluster sequence of A. avenae was assigned a 'statistically significant' match if the E-value from the BLAST output of the sequence alignment was < 1e-05. The program SimiTri [48] was used for the comparison (at the amino acid sequence level) of A. avenae cluster sequences with data in C. elegans, other nematode and non-nematode protein sequence databases, providing a two dimensional display of relative similarity relationships among the three different datasets. "Fragmentation" defined as the representation of a single gene by multiple non-overlapping clusters, was estimated by comparing A. avenae cluster sequences with C. elegans [39].

Gene ontology (GO)

Cluster sequences were classified into Gene Ontology functional categories [54] based on BLAST similarities to known genes in the NCBI Swiss-Prot protein sequence (Swiss-Prot) and using the BLAST2GO annotation tool [55,56] with an E-value cut-off of 1e-05 and summarized according to their biological processes, molecular functions and cellular components. To obtain the complete GO mapping, a node sequence filter in the GO graph was used 50 for biological process, 20 for molecular function, and 20 for the cellular component. The multi-level pie charts were generated using sequence cut-offs of 140, 50 and 40 for biological process, molecular function and cellular components respectively.

Identification of genes encoding cell-wall-degrading enzymes and sequence analyses

BLASTX searches against the GenBank database were used to identify A. avenae clusters encoding potential cell-wall-degrading enzymes. To obtain full length sequences of genes, the plasmid clones from which each of these sequences were obtained were identified and re-sequenced both directions using designed primers (Table 5) in order to obtain the full-length cDNA sequences. The genomic coding region of each cDNA clone was obtained by PCR amplification from A. avenae genomic DNA, using pairs of gene-specific primers flanking each open reading frame. PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and sequenced using standard protocols.

Signal peptide predictions were made using the SignalP program [63]. Protein theoretical pI and molecular mass were predicted using the "Compute pI/MW tool" available at ExPASy http://br.expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html. Sequence alignments were made with a multiple alignment program, MAFFT version 6 http://align.bmr.kyushu-u.ac.jp/mafft/software/about.html and output was produced using BOXSHADE 3.21 http://align.bmr.kyushu-u.ac.jp/mafft/software/about.html

Phylogenetic analyses

The phylogenetic analyses of the catalytic domains of the GHF5 proteins and PL3 proteins were performed on the Phylogeny.fr platform [74] and comprised the following steps. Sequences were aligned with MAFFT (v. 6) configured for highest accuracy (MAFFT with E-INS-i option). Prior to the phylogenetic analysis, signal peptide sequences and other N and C terminal extentions peculiar to individual taxa were excluded. In total 337 and 249 characters were used for GHF5 endoglucanase and pectate lyase respectively for phylogenetic anlaysis. The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using the maximum likelihood method implemented in the PhyML program (v3.0 aLRT). The JTT substitution model was selected assuming an estimated proportion of invariant sites (of 0.018) and 4 gamma-distributed rate categories to account for rate heterogeneity across sites. The gamma shape parameter was estimated directly from the data (gamma = 1.603). Reliability for internal branch was assessed using the aLRT test (SH-Like). Graphical representation and edition of the phylogenetic tree were performed with TreeDyn (v198.3).

In situ hybridisation

In situ hybridisation was performed as described previously[75]. PCR products were generated from the plasmid stocks of the cDNA clones of Aa-eng-1 and Aa-pel-1 using gene specific primers (Table 5). Sense or antisense stra nds were labelled with digoxigenin by asymmetric PCR and hybridised to fixed, permeabilised fragments of mixed stage A. avenae. After washing to remove unbound probe, specifically hybridising probe was detected using Alkaline-phosphatase conjugated Anti-Digoxigenin antibody and NBT/BCIP stock solution (Roche Diagnostics). Specimens were examined with differential interference microscopy (Nikon).

Sequence Data

All EST sequences described in this article have been deposited in the dbEST division of GenBank under the accession numbers [GenBank:GO 479265] - [GenBank: GO484340]. The mRNA and gDNA sequences of GHF5 and PL3 have been deposited in the DDBJ under the accession numbers [DDBJ: AB495300 (Aa-eng-1 mRNA)], [DDBJ:AB495301 (Aa-eng-1 gDNA)], [DDBJ:AB495302 (Aa-eng-2 mRNA)], [DDBJ:AB495303 (Aa-eng-2 gDNA)], [DDBJ:AB495304 (Aa-pel-1 mRNA)], [DDBJ:AB495305 (Aa-pel-1 gDNA)], [DDBJ:AB495306 (Aa-Pel-2 mRNA)] and [DDBJ:AB495307 (Aa-pel-2 gDNA).

Authors' contributions

NK and TK conceived and designed the research plan and executed all of the experiments. HO provided the A. avenae isolate used in this study. HO and JTJ coordinated the project. NK wrote the manuscript. TK contributed to the bioinformatics analysis and assisted in preparing the manuscript. JTJ interpreted results, provided valuable assistance in preparing the manuscript. All authors contributed to, read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Venn diagram illustrating the distribution of BLAST hits for "other nematode" (other than C. elegans) specific A. avenae cluster sequences. Positive hits were identified for the BLASTX and TBLASTX searches of 137 sequences (Fig. 3) and matches were found in "plant parasitic", "animal parasitic and other", and "free living" nematodes. Thirty four A. avenae cluster sequences produced significant match (E < 1e-5) only to sequences from plant parasitic nematodes.

A. avenae transcripts similar to stress-response genes related to desiccation. BLASTX searches (E < 1e-5) of 2,700 cluster sequences against non redundant protein databases allowed identification of some genes that can encode proteins or enzymes known to be associated with desiccation-stress of nematodes.

Gene Ontology mappings (using GO slim terms) for A. avenae clusters. Note that individual GO categories can have multiple mappings. To obtain the complete GO mapping, a node sequence filter in the GO graph was used 50 for biological process, 20 for molecular function, and 20 for the cellular component.

Contributor Information

Nurul Karim, Email: nkarim@affrc.go.jp.

John T Jones, Email: jjones@scri.ac.uk.

Hiroaki Okada, Email: hokada@affrc.go.jp.

Taisei Kikuchi, Email: kikuchit@affrc.go.jp.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Asuka Shichiri for technical assistance. NK is supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Postdoctoral Fellowship for foreign researchers. TK has been funded by Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists (B) 18780032. JTJ is supported by Scottish Executive Environment and Rural Affairs Department. This work was supported by a grant to TK and JTJ from the Royal Society of Edinburgh and by funding through ERASMUS MUNDUS programme 2008-102 (EUMAINE).

References

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard JS. The use of Caenorhabditis elegans in parasitic nematode research. Parasitology. 2004;128(Suppl 1):S49–S70. doi: 10.1017/S003118200400647X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ley P, Blaxter M. In: Biology of Nematodes. Donald LL, editor. London, UK: Taylor and Francis; 2002. Systematic position and phylogeny; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Barker KR. On the disease reduction and reproduction of the nematode Aphelenchus avenae on isolates of Rhizoctonia solani. Plant Dis Reptr. 1964;48:428–432. [Google Scholar]

- Klink JW, Barker KR. Effect of Aphelenchus avenae on the survival and pathogenic activity of root-rotting fungi. Phytopathology. 1968;58:228–232. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CL, Russel C, Foster CD, Mcnew RW. Aphelenchus avenae, a potential biological control agent for root rot fungi. Plant Disease. 1981;65:423–424. [Google Scholar]

- Choo PH, Estey RH. Control of the damping-off disease of pea by Aphelenchus avenae. Indian J Nematol. 1985;15:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi N, Choi DR. Biological control of soil pests by mixed application of entomopathogenic and fungivorous nematodes. J Nematol. 1991;23:175–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne J, Tunnacliffe A, Burnell A. Plant desiccation gene found in nematode. Nature. 2002;416:3. doi: 10.1038/416038a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailor DP, Schleder EG. Nematodes associated with Minnesota corps 11. Nematodes associated with corn, barley, oats, rye, and wheat. Plant Dis Reptr. 1959;43:329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland JR. Failure of the nematode Aphelenchus avenae to parasitize conifer seedling roots. Plant Dis Reptr. 1967;51:367–369. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner G. The status of nematode Aphelenchus avenae Bastian, 1865 as plant parasite. Phytopathology. 1936;26:294–295. [Google Scholar]

- Chin DA, Estey RH. Studies on the pathogenicity of Aphelenchus avenae Bastian, 1865. Phytoprotection. 1966;47:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Barker KR, Darling HM. Reproduction of Aphelenchus avenae on plant tissue in culture. Nematologica. 1965;11:162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Aikawa T, Kosaka H, Pritchard L, Ogura N, Jones JT. Expressed sequence tag (EST) analysis of the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and B. mucronatus. Mol Biochem Parasit. 2007;155:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Jones JT, Aikawa T, Kosaka H, Ogura N. A family of glycosyl hydrolase 45 cellulases from the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. FEBS Lett. 2004;572:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Shibuya H, Jones JT. Molecular and biochemical characterization of an endo-beta-1,3-glucanase from the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus acquired by horizontal gene transfer from bacteria. Biochem J. 2005;389:117–125. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Shibuya H, Aikawa T, Jones JT. Cloning and characterization of pectate lyases expressed in the esophageal gland of the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:280–287. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Hongmei Li, Karim N, Kennedy MW, Moens M, Jones JT. Identification of putative espansin-like genes form the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, and evolution of the expansin gene family within the Nematoda. Nematology. 2009;11:355–364. doi: 10.1163/156854109X446953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smant G, Stokkermans JP, Yan Y, de Boer JM, Baum TJ, Wang X, Hussey RS, Gommers FJ, Henrissat B, Davis EL. Endogenous cellulases in animals: isolation of beta-1, 4-endoglucanase genes from two species of plant-parasitic cyst nematodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4906–4911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YT, Smant G, Stokkermans J, Qin L, Helder J, Baum T, Schots A, Davis E. Genomic organization of four beta-1,4-endoglucanase genes in plant-parasitic cyst nematodes and its evolutionary implications. Gene. 1998;220:61–70. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso MN, Favery B, Piotte C, Arthaud L, de Boer JM, Hussey RS, Bakker J, Baum TJ, Abad P. Isolation of a cDNA encoding a beta-1,4-endoglucanase in the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita and expression analysis during plant parasitism. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1999;12:585–591. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.7.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YT, Smart G, Davis E. Functional screening yields a new beta-1,4-endoglucanase gene from Heterodera glycines that may be the product of recent gene duplication. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2001;14:63–71. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Allen R, Maier T, Davis EL, Baum TJ, Hussey RS. Identification of a new β-1,4-endoglucanase gene expressed in the esophageal subventral gland cells of Heterodera glycines. J Nematol. 2002;34:12–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledger TN, Jaubert S, Bosselut N, Abad P, Rosso MN. Characterization of a new β-1,4-endoglucanase gene from the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita and evolutionary scheme for phytonematode family 5 glycosyl hydrolases. Gene. 2006;382:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popeijus H, Overmars H, Jones J, Blok V, Goverse A, Helder J, Schots A, Bakker J, Smant G. Degradation of plant cell walls by a nematode. Nature. 2000;406:36–37. doi: 10.1038/35017641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer JM, McDermott JP, Davis EL, Hussey RS, Popeijus H, Smant G, Baum TJ. Cloning of a putative pectate lyase gene expressed in the subventral esophageal glands of Heterodera glycines. J Nematol. 2002;34:9–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle EA, Lambert KN. Cloning and characterization of an esophageal-gland-specific pectate lyase from the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15:549–556. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.6.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Dong R, Allen R, Davis EL, Baum TJ, Hussey RS. Developmental expression and molecular analysis of two Meloidogyne incognita pectate lyase genes. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaubert S, Laffaire JB, Abad P, Rosso MN. A polygalacturonase of animal origin isolated from the root- knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. FEBS Lett. 2002;522:109–112. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02906-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Kudla U, Roze EH, Goverse A, Popeijus H, Nieuwland J, Overmars H, Jones JT, Schots A, Smant G. Plant degradation: a nematode expansin acting on plants. Nature. 2004;427:30. doi: 10.1038/427030a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudla U, Qin L, Milac A, Kielac A, Maissen C, Overmars H, Popeijus H, Roze E, Petrescu A, Smant G. Origin, distribution and 3D-modelling of Gr-EXPB1, an expansin from the potato cyst nematode Globodera rostochiensis. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2451–2457. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roze E Overmars H Mitreva M Bakker J Smant G Identification and characterization of expansin-like proteins from the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne chitwoodi Mol Plant Microbe Interact in press 16673939

- Scholl EH, Thorne JL, McCarter JP, Bird DM. Horizontally transferred genes in plant-parasitic nematodes: a high-throughput genomic approach. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R39. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-6-r39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JT, Furlanetto C, Kikuchi T. Horizontal gene transfer from bacteria and fungi as a driving force in the evolution of plant parasitism in nematodes. Nematology. 2005;7:641–646. doi: 10.1163/156854105775142919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holterman M, Wurff A van der, Elsen S van den, van Megen H, Bongers T, Holovachov O, Bakker J, Helder J. Phylum-wide analysis of SSU rDNA reveals deep phylogenetic relationships among nematodes and accelerated evolution toward crown Clades. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1792–1800. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldal BH, Debenham NJ, De Ley P, De Ley IT, Vanfleteren JR, Vierstraete AR, Bert W, Borgonie G, Moens T, Tyler PA. An improved molecular phylogeny of the Nematoda with special emphasis on marine taxa. Mol Phylogent Evol. 2007;42:622–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Megen H, Elsen S van den, Holterman M, Karssen G, Mooyman P, Bongers T, Holovachov O, Bakker J, Helder J. A phylogenetic tree of nematodes based on about 1,200 full length small subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Nematology. 2009;11:927–950. doi: 10.1163/156854109X456862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitreva M, McCarter JP, Martin J, Dante M, Wylie T, Chiapelli B, Pape D, Clifton SW, Nutman TB, Waterston RH. Comparative genomics of gene expression in the parasitic and free-living nematodes Strongyloides stercoralis and Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Res. 2004;14:209–220. doi: 10.1101/gr.1524804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman CH, Bird DM, Williamson VM, Rokhsar DS, Burke M, Cohn J, Cromer J, Diener S, Gajan J, Graham S. Sequence and genetic map of Meloidogyne hapla: A compact nematode genome for plant parasitism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14802–14807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805946105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad P, Gouzy J, Aury JM, Castagnone-Sereno P, Danchin EG, Deleury E, Perfus-Barbeoch L, Anthouard V, Artiguenave F, Blok VC. Genome sequence of the metazoan plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audic S, Claverie JM. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 1997;7:986–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RD, Winterrowd CA, Hatzenbuhler NT, Shea MH, Favreau MA, Nulf SC, Geary TG. Cloning of a cDNA encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase from Haemonchus contortus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:285–294. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90226-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary TG, Winterrowd CA, Alexander-Bowman SJ, Favreau MA, Nulf SC, Klein RD. Ascaris suum: cloning of a cDNA encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. Exp Parasitol. 1993;77:155–161. doi: 10.1006/expr.1993.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JT, Smant G, Blok VC. SXP/RAL2 proteins of the potato cyst nematode Globodera rostochiensis: secreted proteins of the hypodermis and amphids. Nematology. 2000;2:887–893. doi: 10.1163/156854100750112833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wombase. http://wormbase.org/

- Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D16–D20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson J, Blaxter M. SimiTri - visualizing similarity relationships for groups of sequences. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:390–395. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btf870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano I, WU Z, Nakada T, Matsuo A, Takahashi Y. Molecular cloning and characterization of a serine proteinase inhibitor from Trichinella spiralis. Parasitology. 2001;123:77–83. doi: 10.1017/S0031182001008010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford L, Guiliano DB, Oksov Y, Debnath AK, Liu J, Williams SA, Blaxter ML, Lustigman S. Characterization of a Novel Filarial Serine Protease Inhibitor, Ov-SPI-1, from Onchocerca volvulus, with Potential Multifunctional Roles during Development of the Parasite. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40845–40856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal K, Walton LJ, Tunnacliffe A. LEA proteins prevent protein aggregation due to water stress. Biochem J. 2005;388:151–157. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal TZ, Glazer I, Koltai H. Differential gene expression during desiccation stress in the insect-killing nematode Steinernema feltiae IS-6. J Parasitol. 2003;89:761–766. doi: 10.1645/GE-3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari BN, Wall DH, Adams BJ. Desiccation survival in an Antarctic nematode:molecular analysis using expressed sequenced tags. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT. Gene ontology:tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BlastGo. http://www.blast2go.de/

- Brydon LJ, Gooday GW, Chappell LH, King TP. Chitin in egg shells of Onchocerca gibsoni and Onchocerca volvulus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1987;25:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(87)90090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman JA, Piessens WF. Chitin synthesis and sheath morphogenesis in Brugia malayi microfilariae. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1985;17:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(85)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam R, Kaltmann B, Rudin W, Friedrich T, Marti T, Lucius R. Identification of chitinase as the immunodominant filarial antigen recognized by sera of vaccinated rodents. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1441–1447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K, Brydon LJ, Chappell LH, Gooday GW. Chitinolytic activities in Heligmosomoides polygyrus and their role in egg hatching. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;58:317–323. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovici CR, Roubin R, Coulier F, Pontarotti P, Birnbaum D. The family of Caenorhabditis elegans tyrosine kinase receptors: similarities and differences with mammalian receptors. Genome Res. 1999;9:1026–1039. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.11.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Allen R, Maier T, McDermott J, Davis E, Baum T, Hussey R. Characterisation and developmental expression of a chitinase gene in Heterodera glycines. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:1293–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, Heijne Gv, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodom. http://prodom.prabi.fr/prodom/current/html

- Spieth J, Lawson D. Overview of gene structure. WormBook. http://www.wormbook.org/chapters/www_overviewgenestructure/overviewgenestructure.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal T, Steward K. In: C. elegans II. Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR, editor. Cold Spring Harbor laboratory press; 1997. RNA processing and gene structure; pp. 117–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyndt T, Haegeman A, Gheysen G. Evolution of GHF5 endoglucanase gene structure in plant-parasitic nematodes: no evidence for an early domain shuffling event. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:305. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchik V, Robert-Baudouy J, Hugouviux-Cotte-Pattat N. Pectate lyase PelI of Ervinia chrysanthemi 3937 belongs to a new family. J Bacteriol. 1999;179:7321–7330. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7321-7330.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southey JF. Laboratory Methods for Work with Plant and Soil Nematodes. London: H.M. Stationery Off; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Browne JA, Dolan KM, Tyson T, Goyal K, Tunnacliffe A, Burnell AM. Dehydration-specific induction of hydrophilic protein genes in the anhydrobiotic nematode Aphelenchus avenae. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:966–975. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.4.966-975.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dederich DA, Okwuonu G, Garner T, Denn A, Sutton A, Escotto M, Martindale A, Delgado O, Muzny DM, Gibbs RA. Glass bead purification of plasmid template DNA for high throughput sequencing of mammalian genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e32. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson J, Anthony A, Wasmuth J, Schmid R, Hedley A, Blaxter M. PartiGene--constructing partial genomes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1398–1404. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson J, Guiliano DB, Blaxter M. Making sense of EST sequences by CLOBBing them. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]