Abstract

Background

The 90-kDa heat-shock proteins (Hsp90) have rapidly evolved into promising therapeutic targets for the treatment of several diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Hsp90 is a molecular chaperone that aids in the conformational maturation of nascent polypeptides, as well as the rematuration of denatured proteins.

Discussion

Many of the Hsp90-dependent client proteins are associated with cellular growth and survival and, consequently, inhibition of Hsp90 represents a promising approach for the treatment of cancer. Conversely, stimulation of heat-shock protein levels has potential therapeutic applications for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases that result from misfolded and aggregated proteins.

Conclusion

Hsp90 modulation exhibits the potential to treat unrelated disease states, from cancer to neurodegenerative diseases, and, thus, to fold or not to fold, becomes a question of great value.

The heat-shock proteins are an important class of prosurvival proteins that are intimately involved in cell survival, stress response, and protein management. The 90-kDa heat-shock protein (Hsp90) is one of the most widely studied heat-shock proteins and it has emerged as therapeutic target for the treatment of several diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [1–13]. Many proteins involved in signal-transduction pathways associated with cancer are Hsp90 client proteins. Inhibition of Hsp90 by cytotoxic agents has the capacity to disrupt these pathways associated with cancerous cell proliferation and survival [12,14,15]. Additionally, Hsp90 is capable of suppressing protein aggregation, solubilizing protein aggregates and targeting protein clients for degradation. Induction of the heat-shock response by small molecules may facilitate the clearance of toxic aggregates responsible for neurodegenerative diseases and, consequently, Hsp90 has emerged more recently as a target for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases that result from misfolded and aggregated proteins [16].

Properties, structure & function of Hsp90

Properties

The Hsp90 molecular chaperones are responsible for the post-translational maturation of many proteins as well as the solubilization of protein aggregates and the refolding of denatured proteins [12,17–20]. Hsp90 represents one of the most prevalent molecular chaperones in eukaryotic cells, comprising 1–2% of total cytosolic proteins [1,17,21]. Although there are 17 genes that encode for Hsp90 in the human genome, only six of these produce the four functional isoforms [22–24]. The two most predominant Hsp90 isoforms are Hsp90α and Hsp90β, which are found primarily in the cytosol. Hsp90α is induced upon exposure to stress, whereas Hsp90β is constitutively active and is considered a housekeeping chaperone. The genes for both Hsp90α and Hsp90β are located on chromosome 4 and are regulated through independent transcriptional events [22]. Hsp75/TRAP-1 is another homologue located in the mitochondrial matrix [22]. The 94-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP)94 is induced in response to declining glucose levels and resides in the endoplasmic reticulum [22,25,26].

Structure

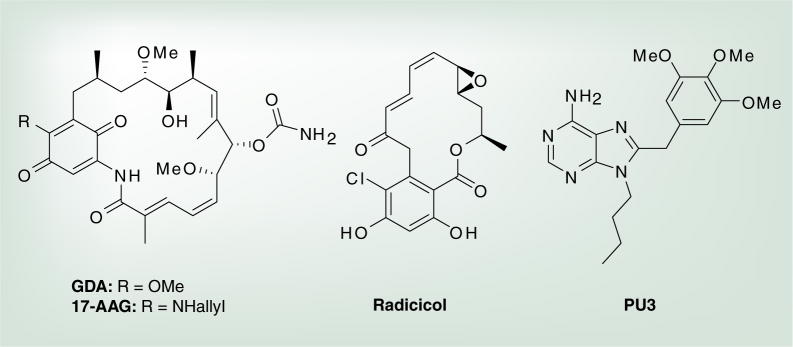

The Hsp90 monomer is composed of four domains: a highly conserved N- and C-terminal domain, a middle domain and a charged linker region that connects the N-terminal and middle domains [24,27–30]. The 25-kDa N-terminal domain is responsible for binding ATP in a unique bent conformation that is reminiscent of other members of the gyrase, Hsp90, histidine kinase and MutL (GHKL) superfamily [31]. Proteins in this family share a common Bergerat ATP-binding fold, named appropriately after Agnes Bergerat who first identified this motif in 1997 [32]. This motif consists of four-interstranded β-sheets and three α-helices in a helix–sheet–helix orientation, wherein the ATP-binding site exists and manifests interactions with residues in the loop region that connects the α-helices and β-sheets [31]. In addition to ATP, several co-chaperones and some Hsp90 inhibitors bind to this region. Example compounds that bind competitively with ATP to the N-terminal ATP-binding site include the natural products geldanamycin (GDA) and radicicol and 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) and compounds of the purine scaffold (Figure 1) [33–36].

Figure 1.

Hsp90 N-terminal inhibitors.

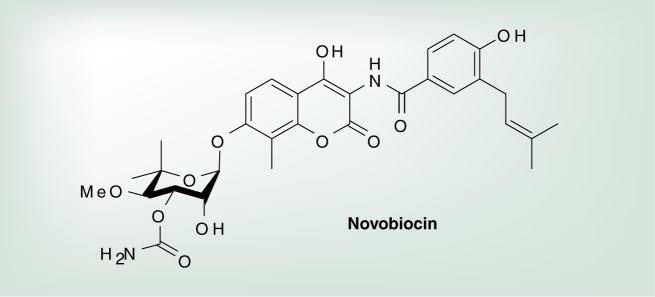

The 12-kDa C-terminal domain is responsible for homodimerization of Hsp90 into its biologically active form [8,27,29,37]. The C-terminal domain is also responsible for coordinating interactions with several Hsp90 partner proteins, specifically the Hsp70–Hsp90 organizing protein that contains a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-recognition sequence recognized by both Hsp90 and the related chaperone Hsp70 [38,39]. The C-terminal domain also contains a putative nucleotide-binding site; however, the C-terminal ATP-binding site functions to facilitate nucleotide exchange at the N-terminus and does not manifest ATPase activity [40]. The coumarin antibiotics, such as novobiocin and chlorobiocin (Figure 2) [41], as well as cisplatin [42], bind to this site and disrupt Hsp90 function.

Figure 2.

Hsp90 C-terminal natural product inhibitor.

The 40-kDa middle region, linked to the N-terminus by a highly charged linker, is responsible for binding the γ-phosphate of ATP when bound to the N-terminal binding pocket. This region is also important for the recognition and binding of client proteins and co-chaperones. It is largely amphipathic in nature and can mediate interactions with various proteins [18,43]. The middle domain also appears to play a key role in mediating Hsp90’s N-terminal ATPase activity, as deletion of this region significantly retards Hsp90’s inherent ATPase activity, suggesting coordination of ATP hydrolysis by the entire protein, which may be conformationally driven [18].

Function

Hsp90 not only aids the conformational maturation of nascent polypeptides and activation of receptors under normal cellular conditions but, under stressful conditions, such as elevated temperature, abnormal pH or nutrient deprivation, Hsp90 can be overexpressed and aid the rematuration of denatured proteins in conjunction with Hsp70 [44–46]. Evidence suggests that expression of Hsp90 and other heat-shock proteins is mediated by the transcription factor HSF1. Under normal conditions, Hsp90 binds HSF1, preventing HSF1 release and transcriptional activation of the heat-shock response. However, it has been postulated that, under cellular stress, the HSF1/Hsp90 complex is disassembled and HSF1 trimerizes and ultimately translocates to the nucleus, wherein it binds to the heat-shock binding elements and initiates transcription of the heat-shock genes that encode for Hsp27, Hsp40, Hsp70 and Hsp90 [47–59].

The mechanism by which Hsp90 mediates the maturation of nascent polypeptides remains unresolved. There are a number of proteins that combine to form a competent heteroprotein complex, regarded as the Hsp90 protein-folding machine. Numerous co-chaperones, immunophillins and partner proteins bind the Hsp90 scaffold to form the competent protein-folding machinery, as denoted in Table 1 [60–86].

Table 1.

Hsp90-associated proteins that comprise the Hsp90 protein-folding machinery.

| Co-chaperone or cofactor | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Ahal | Stimulates ATPase activity | [61] |

| Cdc37 | Mediates activition of protein kinase substrates | [62] |

| CHIP | Involved in degradation of unfolded client proteins | [63,64] |

| CRN | Ubiquitin ligase (E3) involved in client protein degradation | [65] |

| Cyclophilin-40 | Peptidyl prolyl isomerase | [66,67] |

| FKBP51 and 52 | Peptidyl prolyl isomerase | [67,68] |

| Hop | Mediates interaction between Hsp90 and Hsp70 | [69,70] |

| Hsp40 | Stabilizes and delivers client protein to Hsp90 folding machine | [71,72] |

| Hsp70 | Stabilizes and delivers client protein to Hsp90 folding machine | [73–75] |

| NASP | Stimulates ATPase activity | [76] |

| p23 | Stabilizes closed, clamped substrate bound conformation | [30] |

| PP5 | Protein phosphatase | [77–79] |

| Sgt1 | Client adaptor, involved in client recruitment | [80] |

| Tah1 | Weak affect on ATPase activity | [81] |

| Tom70 | Facilitates translocation of preproteins into mitochondrial matrix | [82,83] |

| Tpr2 | Involved in ATP hydrolysis and substrate release | [84,85] |

| WISp39 | Regulates p21 stability | [86] |

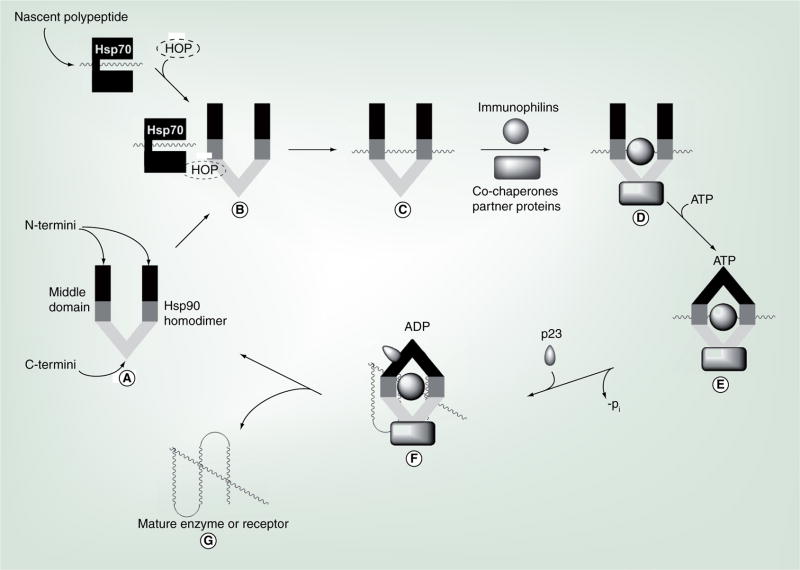

A polypeptide substrate can obtain conformational maturity by proceeding through various complexes and conformations that are mediated by the Hsp90 machine (Figure 3) [87]. Succinctly, the nascent polypeptide exits the ribosome and is stabilized by an Hsp70/Hsp40/ADP complex that prevents side-chain interactions, which can otherwise lead to aggregation [74]. This complex is often further stabilized by the Hsp70-interacting protein (HIP) or, alternately, Bcl2-associated athanogene (BAG) homologues that facilitate exchange of ADP for ATP, resulting in concomitant release of the polypeptide substrate and dissociation of the complex [88,89]. In the case of telomerase and steroid hormone receptors, Hsp-organizing protein (HOP), which contains tetre-tricopeptide repeats (TPRs) that are recognized by both Hsp70 and Hsp90, binds the Hsp70/protein complex and Hsp90 (Figure 3B), promoting transfer of the unfolded protein from Hsp70 to the Hsp90 homodimer, resulting in dissociation of Hsp70, HIP and HOP [38,39,90–92]. After this, immunophilins and co-chaperones bind Hsp90 to form a heteroprotein complex (Figure 3D), which binds ATP at the N-terminus and wraps around the bound client protein substrate (Figure 3) [93]. N-terminal dimerization occurs and p23 is recruited to the complex to stabilize the clamped, protein substrate-bound conformation, modulating ATP hydrolysis (Figure 3F) [17]. Activator of Hsp90 ATPase homologue 1 (AHA1) then stimulates Hsp90’s inherent ATPase activity [21]. In an uncharacterized process, the client protein undergoes topological rearrangement to produce the bioactive conformation, which is subsequently released from the Hsp90 protein-folding machinery (Figure 3G) [68,94].

Figure 3. The Hsp90-mediated protein-folding process.

HOP: Hsp-organizing protein; Hsp: Heat-shock protein.

Therapeutic roles for Hsp90

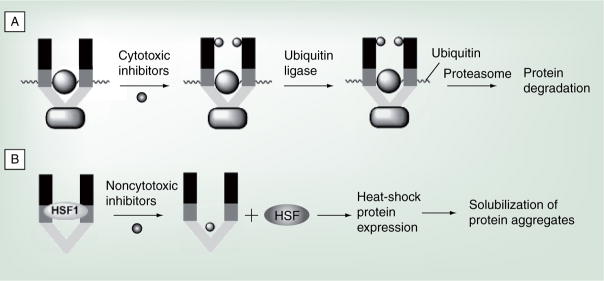

Hsp90 is responsible for the conformational maturation of many nascent polypeptides. In addition, the Hsp90 protein-folding machinery assists in the solubilization and refolding of aggregated and denatured proteins. As a result, small-molecule Hsp90 modulators can exert differing activities. Inhibition of Hsp90 by cytotoxic agents results in the degradation of Hsp90 client proteins by preventing the formation of the productive, closed, clamped conformation between Hsp90 and substrate, thereby targeting the complex for ubiquitinylation and proteasomal degradation [63,95,96]. Compounds that manifest such activities possess excellent therapeutic potential for the treatment of cancer because multiple signaling cascades can be simultaneously disrupted via Hsp90 inhibition (Figure 4A) [10]. In contrast, induction of Hsp90 expression by nontoxic molecules can lead to increased chaperone levels that minimize the accumulation of aggregated proteins [97,98]. Small molecules that induce Hsp expression represent novel approaches for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), as well as multiple sclerosis (MS) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Modulation of Hsp90 via small molecules.

Proposed mechanisms of Hsp90 modulation for the treatment of (A) cancer and (B) neurodegenerative diseases.

Cancer

In the past, therapeutic strategies for the treatment of cancer have focused on disruption of individual oncogenic enzymes and receptors. Newer paradigms for cancer chemotherapy have evolved to use combination therapies comprised of multiple drugs, each of which targets an individual protein. An alternative approach has been made available through Hsp90 inhibitors, which allows for simultaneous disruption of multiple signaling pathways, thus exerting a combinatorial attack on transformed cell machinery. Consequently, Hsp90 inhibition represents a new and powerful therapeutic approach towards the treatment of cancer [2,21]. In 2000, Hanahan and Weinberg described the six hallmarks of cancer manifested by alteration of key regulatory proteins, enzymes and receptors that become hijacked by malignant cells [99]. These hallmarks include:

Self-sufficiency in growth signals

Insensitivity to antigrowth signals

Evasion of apoptosis

Limitless replicative potential

Sustained angiogenesis

Tissue invasion/metastasis

As shown in Table 2, disruption of the Hsp90 protein-folding machinery directly affects all six hallmarks of cancer by preventing maturation of proteins associated directly with each hallmark [1,15,96]. No other cellular target has been ascribed to effect all hallmarks of cancer, beyond Hsp90, making it one of the most sought after cancer targets at this time [100].

Table 2.

Hsp90-dependent proteins associated with the six hallmarks of cancer.

| Hallmark | Client protein(s) |

|---|---|

| Self-sufficiency in growth signals | Raf-1, AKT, Her2, MEK, Bcr-Abl |

| Insensitivity to anti-growth signals | Plk, Wee1, Myt1, CDK4, CDK6, |

| Evasion of apoptosis | RIP, AKT, mutant p53, c-MET, Apaf-1, survivin |

| Limitless replicative potential | Telomerase (h-Tert) |

| Sustained angiogenesis | FAK, AKT, Hif-1α, VEGFR, Flt-3 |

| Tissue invasion/metastasis | c-MET |

Due to the overwhelming need to fold over-expressed and mutated proteins, it is not surprising that Hsp90 and associated chaperones are elevated in human cancers [101,102]. More interesting, it has been demonstrated that Hsp90 in cancer cells exhibits a higher affinity for inhibitors than Hsp90 from normal cells, providing an opportunity to develop drugs that exhibit high differential selectivity [1]. In tumor cells, Hsp90 resides in a heteroprotein complex bound to both client proteins and co-chaperones, whereas Hsp90 in nontransformed cells resides in the homodimeric state [103,104]. As stated earlier, it is the heteroprotein complex that exhibits higher affinity for ATP. Consequently, small molecules that bind competitively with ATP bind and prohibit the maturation process with higher selectively for the Hsp90 machinery present in malignant cells.

Hsp90 inhibitors have been the subject of many clinical trials for the treatment of cancer and, currently, the GDA derivative 17-AAG is in Phase II clinical trials [105–109]. Toxicity of the benzoquinone-containing compound 17-AAG is of concern; however, new formulations and structural analogues have improved tolerability [11,110–115]. Inhibition of Hsp90 is an exciting therapeutic target for the treatment of cancer and results from current clinical trials will significantly impact future cancer treatment strategies. As several reviews have focused on the implications of Hsp90 as a therapeutic target for the treatment of cancer [2,11,21,59,96,113,116,117], the remainder of this review is focused on Hsp90 as a target for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases are diseases that arise from cell death that occurs in the CNS, including neurons associated with movement, sensory, memory and decision-making [118]. Neuronal cell death in these diseases has a variety of origins, but one important commonality is the accumulation of misfolded proteins that result in cytotoxicity. Because molecular chaperones prevent protein aggregation, refold denatured proteins and solubilize protein aggregates, it has been proposed that the heat-shock proteins may be viable therapeutic targets for treatment of numerous neurodegenerative diseases, examples of which are provide in Table 3 [3].

Table 3.

Neurodegenerative diseases and pathogenic proteins associated with aggregation.

| Disease | Protein |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | Amyloid-β, tau |

| Parkinson’s disease | α-synuclein |

| Huntington’s disease | Mutant huntingtin |

| Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy | Mutant androgen receptor |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Mutant superoxide dismutase-1 |

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common neurodegenerative disorder, affecting more than 10% of the population aged 65 years and older, and nearly 30 million people worldwide [119,120]. The senile dementia observed in patients with AD is marked by a loss of memory, language and reasoning, ultimately affecting many aspects of their lives [120]. Pathologically, AD is caused by formation of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the extra (tau aggregates) and intracellular (Aβ aggregates) space of neurons and synapses. There are several hypotheses to describe how these aggregates cause disease. One scenario is that these oligomers are toxic to neuronal cells. However, it has also been postulated that Aβ plaques can initiate immune response by the recruitment of microglia and subsequent astrocytosis [120–123]. Current therapies for AD involve cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA receptor antagonists, which only slow disease progression [119,120]. Meanwhile, inhibition of β- and γ-secretase, which are the proteases responsible for producing the protein fragments susceptible to aggregation, and immunotherapies targeting the protein aggregates themselves are being explored [124]. Recently, Hsp90 emerged as a novel target for the treatment of AD. The rationale behind such an approach is based on the premise that small-molecule inhibitors of Hsp90 induce expression of the heat-shock proteins, which ultimately lead to solubilization of protein aggregates, refolding of misfolded proteins and directing misfolded proteins and protein aggregates to the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway for degradation. Alternative hypotheses suggest that Hsp90 can prevent fibril formation by binding and stabilizing the susceptible polypeptides [125].

In 2003, Dou and coworkers demonstrated that upregulation of the heat-shock proteins that occur upon administration of the N-terminal Hsp90 inhibitor GDA resulted in decreased formation of NFTs, decreased levels of aggregated tau and an increase in soluble tau in both the hippocampus of transgenic mice containing mutant tau and in tissue samples from the brain of AD patients [126]. Under nonpathogenic conditions, tau enhances microtubule stability [127]. However, in AD, hyperphosphorylation of tau is observed and causes dissociation of microtubules, allowing incorporation into NFTs [98,126]. These researchers demonstrated that the level of microtubule-associated tau increased after treatment with GDA. A reduction in microtubule-associated tau was observed alongside a concomitant increase in cytosolic aggregated tau in cells treated with Hsp90- and Hsp70-targeted siRNA [126].

Human H4 neuroglioma cells were treated with synthetic Hsp90 inhibitors to investigate the effects of Hsp90 inhibition on both tau levels and heat-shock response [128]. It was observed that several inhibitors induced heat-shock response, as evidenced by elevated levels of Hsp70, Hsp40 and Hsp27. Cells treated with these same compounds also exhibited decreased levels of tau, indicating a reciprocal relationship between tau and heat-shock levels. No toxicity was observed in these studies, which has been one of the limiting factors in the development of Hsp90 inhibitors such as GDA [128], because GDA induces client protein degradation at the same concentration it induces heat-shock response. Additionally, an Hsp90 inhibitor of the purine scaffold, EC102, caused reduction of aberrant tau in the brain of a mouse transgenic for tauopathy following intraperitoneal injection. This result is promising as the inhibitor crossed the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and reduced tau levels without toxicity to the mice [129].

Additional rationale for the treatment of AD involves regulation of tau phosphorylation to decrease hyperphosphorylated tau, which exhibits the potential to incorporate into NFTs. Luo and coworkers demonstrated that inhibition of Hsp90 can lead to decreased tau aggregates and hyperphosphorylated tau in vivo [130]. This degradation of phosphorylated tau by Hsp90 is mediated by the co-chaperones CHIP, a ubiquitin ligase and Akt [129,131]. The effect of Hsp90 inhibition on p35 levels was also examined, as p35 is an important activator of cyclin-dependent protein 5, which contributes to phosphorylation of tau [132]. Treatment with Hsp90 inhibitors caused decreased levels of p35, presumably resulting from increased degradation of p35 [130,133]. In a similar approach, Dou and coworkers demonstrated that Hsp90 inhibition can reduce the levels of GSK3β, a kinase responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of tau and subsequent reduction of tau phosphorylation [133]. Preventing hyperphosphorylation of tau prevents dissociation from microtubules and appears to prevent formation of hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates. Attenuating the activity of kinases through Hsp90 is of significant importance, as the number of kinases in the human proteome makes selective targeting of kinases difficult.

An alternative treatment for AD may involve regulation of Aβ formation and aggregation. In in vitro studies performed, it was observed that recombinant Hsp70/Hsp40 and Hsp90 were able to suppress Aβ aggregate formation. Synthetic Aβ pretreated to increase aggregation was treated with both purified recombinant Hsp70/Hsp40 and Hsp90 in the presence of ATP. Hsp90 and the Hsp70/Hsp40 complex inhibited Aβ formation and slowed the rate of aggregation in a chaperone concentration-dependent manner [134]. Additionally, Hsp40/Hsp70 and Hsp90’s ATPase activity was necessary for inhibition of protein aggregation. Experiments performed using ATPγS (an ATP analogue that is hydrolyzed at a much slower rate) inhibited the anti-aggregation properties of the chaperone machine, especially in the case of Hsp70/Hsp40, as Hsp90’s effect on aggregation was not significantly affected by ATPγS. Two mechanisms by which the heat-shock proteins inhibit Aβ assembly have been proposed. In one model, the chaperone binds misfolded amyloid in an ATP-independent manner, preventing it from aggregation. This model is consistent with the observed dependency on Hsp90 ATPase activity. Alternatively, the chaperone may bind Aβ in an ATP-dependent manner, changing Aβ’s conformation to one that is less susceptible to aggregation [134].

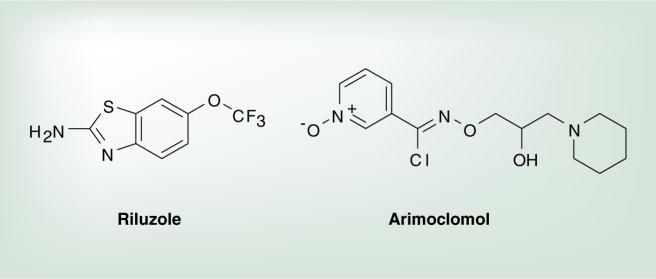

Although GDA is a potent inhibitor of Hsp90 and is the standard control used in Hsp90 inhibitory assays, its therapeutic window is very narrow because it manifests cytotoxicity. Therefore, efforts have been made to identify more suitable small-molecule inhibitors, specifically, those with the potential to cross the BBB, which is required for the treatment of neurological diseases. In the Blagg Laboratory, a novobiocin analogue, A4, was developed that demonstrated exceptional promise as a neuroprotective agent with no signs of toxicity at 100 μM (Figure 5) [135]. In freshly prepared neuronal cells treated with Aβ alone, significant toxicity was observed; however, embryonic primary neurons treated with Aβ in the presence of A4 showed significantly decreased toxicity in a dose-dependent manner. Additionally, A4 was evaluated in the rhodamine 123 assay and results indicated that A4 is not a substrate for the P-glycoprotein pump and has the potential to permeate the BBB, because time-dependent linear transport across a brain microvessel endothelial layer was observed [135].

Figure 5.

Neuroprotective Hsp90 inhibitor.

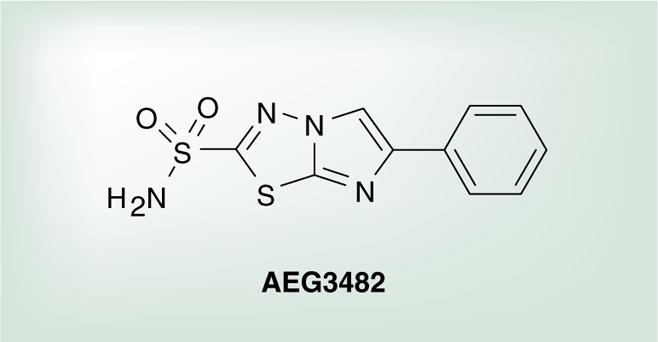

An additional aspect of Hsp90 inhibition is its effect on Hsp70 expression and, ultimately, on c-jun JNK signaling. The JNK pathway is important in neuronal apoptosis and, if inhibited, may hinder the progression of neurodegeneration [136]. It has previously been reported that Hsp70 can bind and inhibit JNK, resulting in a reduction of the number of cells undergoing apoptosis [4,7]. Salehi and coworkers were able to demonstrate that a small-molecule inhibitor of Hsp90, AEG3482 (Figure 6), causes activation of the heat-shock response, including Hsp70 expression, leading to blockade of JNK activation and, ultimately, evasion of apoptosis [137]. It has now been shown that Hsp90 inhibitors not only prevent tau and Aβ aggregation and cause resolubilization of already formed aggregates, but also prevent apoptosis that leads to neurodegeneration.

Figure 6.

Neuroprotective Hsp90 inhibitor.

In summary, it has been observed that Hsp90 inhibition can affect several mechanistic pathways involved in AD. Inhibition of Hsp90 has been shown to decrease tau phosphorylation caused by decreased GSK3β levels, increase the levels of microtubule-associated tau, decrease tau aggregates, decrease Aβ aggregate levels and prevent Aβ aggregate formation and toxicity. Therefore, Hsp90 inhibitors may offer a promising new approach toward the treatment of AD.

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease is a movement disorder best characterized by a loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra resulting in tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia and occasionally akinesia. Biochemically, PD is characterized by the formation of Lewy bodies, which are spherical masses composed of aggregated α-synuclein, which is a soluble cytoplasmic protein with unknown function [138,139]. Current therapies for PD include neurotransmitter-replacement therapy and dopamine agonists; however, these treatments are complicated by undesired side effects. Over the last decade, Hsp90 inhibitors have emerged as potential therapeutic options for PD.

Perhaps the most significant contribution to this area was by Bonini and coworkers in 2002. Transgenic Drosophila expressing both α-synuclein and Hsp70 were used to investigate the effect of Hsp70 expression on neuronal loss, as flies transgenic for α-synuclein exhibited PD-like neuronal loss. After 20 days, Drosophila expressing both α-synuclein and Hsp70 showed no loss of dopaminergic neurons. Immunoblot studies confirmed that Hsp70 expression did not alter the expression of α-synuclein, indicating that Hsp70 effectively protected neurons from α-synuclein toxicity. Conversely, Drosophila transgenic for mutant Hsp70 and α-synuclein showed acceleration of dopaminergic loss [140]. Hsp70 also exhibited an effect on Lewy body formation; Drosophila co-expressing both α-synuclein and Hsp70 did not manifest Lewy body formation, whereas flies expressing α-synuclein demonstrated an increase in both the size and number of inclusions. Later in 2002, this finding was linked to Hsp90 as Drosophila expressing α-synuclein were treated with the Hsp90 inhibitor GDA. These Drosophila also showed protection from α-synuclein toxicity as the number of dopaminergic neurons remained constant over the 20-day experiment with an increase in Hsp70 levels [141]. Similarly, in 2004, mice transgenic for Hsp70 overexpression and α-synuclein exhibited a decline in the amount of both high-molecular-weight and detergent-insoluble α-synuclein, which appear to be the species responsible for protein aggregation and toxicity. In an in vitro model, the overexpression of Hsp70 led to both reduced α-synuclein and cytotoxicity [142]. Additionally, in a mouse model of PD induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), GDA was shown to reduce dopaminergic neuronal death if administered before MPTP induction of PD-like symptoms. The observed reduction in toxicity was correlative with increased Hsp70 levels that occurred in response to Hsp90 inhibition [143]. These combined results demonstrated that Hsp90-mediated activation of Hsp70 expression is a viable approach towards the treatment of PD and has been demonstrated in both in vivo and in vitro models.

Using a vastly different approach, the effects of Hsp90 inhibition on leucine-rich repeat kinase (LRRK)2 was investigated by Wang and coworkers. Mutations in the LRRK2 gene have been linked to autosomal-dominant PD and, presumably, these mutations are associated with toxicity-associated function. Although some researchers have targeted the gene product itself, Wang and coworkers sought to downregulate the activity of this kinase through Hsp90 inhibition. Hsp90 forms a complex with mutant LRRK2, and treatment of cells overexpressing LRRK2 with GDA caused disruption of the LRRK2/Hsp90 complex. Treatment with GDA caused decreased levels of the LRRK2 mutant gene product, indicating potential degradation through the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway [144,145].

By directly reducing the amount of α-synuclein or Lewy body-induced toxicity or by mediating an alternate pathway such as the LRRK2 pathway, Hsp90 inhibition exhibits great promise for PD. Although Hsp90 inhibitors have not been evaluated clinically for the treatment of PD, there is potential for these agents if toxic side effects can be minimized.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

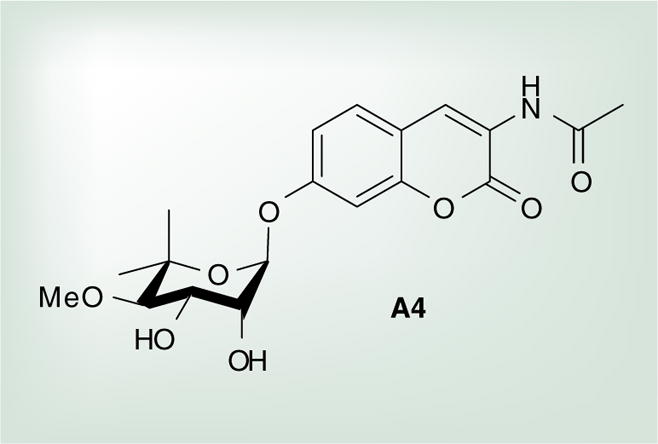

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a very aggressive neurodegenerative disease. This disease is marked by the degeneration of motor neurons in the spinal cord and motor cortex, which ultimately leads to complete loss of voluntary muscle movement, paralysis and death caused by respiratory depression. The survival rate among individuals diagnosed is only 10% and death usually ensues within 1–5 years following diagnosis. The causes of ALS are highly speculative and some data link protein misfolding, oxidative stress and glutamate toxicity. In addition, a gene mutation has also been linked to familial ALS that accounts for roughly 10% of the cases. This mutation occurs on the Cu/Zn SOD1 gene, whose gene product is responsible for converting the superoxide anion into molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, and is susceptible to aggregation when mutated [146]. Little is known regarding the etiology and pathology of ALS and, accordingly, there are few drugs to treat ALS. Riluzole is currently the only therapeutic agent approved by the US FDA for ALS (Figure 7). Riluzole is a glutamate antagonist that prolongs survival by 3–6 months and does not aid in the reversion of neurodegeneration [147]. Current therapeutic research has focused upon other antiglutamate agents, antioxidants and antiapoptotic compounds. However, compounds that attenuate heat-shock response have gained considerable attention in recent years as an alternative approach. Although heat-shock protein are upregulated in ALS, it is believed that they are sequestered into protein aggregates. It has been proposed that heat-shock protein inhibitors that induce heat-shock response will increase heat-shock protein levels, resulting in disaggregation, ultimately benefiting ALS patients.

Figure 7.

Currently used drug for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, riluzole, and the Hsp90 inhibitor arimoclomol.

Arimoclomol, which is currently in clinical trials for the treatment of ALS, has emerged as a promising drug that exerts its activity by inducing heat-shock protein expression (Figure 7) [148]. Using SOD1 mutant mice, the efficacy of arimoclomol as a therapeutic agent to treat ALS was examined. Transgenic mice were treated with arimoclomal starting at the age of 35 days and, at 120 days, the number of functional motor units in each extensor digitorum longus muscle was determined. SOD1 mutant mice treated with arimoclomol exhibited a 73% increase in motor unit survival compared with SOD1 mice left untreated, indicating disease progression is hindered upon treatment with arimoclomol. The effect of arimoclomol on motor neuron survival in the sciatic motor pool was also investigated in SOD1 mutant mice. Mice treated with arimoclomal exhibited almost twice the number of motor neurons than untreated mice. In addition, SOD1 mutant mice treated with arimoclomal had an 18% increase in lifespan after disease onset compared with untreated SOD1 mutant mice. In investigating the origin of arimoclomal’s activity, the authors found that the spinal cords of SOD1 mutant mice had increased levels of phosphorylated HSF1, which is indicative of prolonged HSF1 activation leading to increased expression of Hsp70 and Hsp90 [149]. Additionally, arimoclomal (also known as BRX-220) could induce upregulation of heat-shock proteins and can rescue motor neurons from cell death. Rat pups subjected to sciatic nerve crush at birth were also treated with BRX-220. These mice had increased motor neuron survival and increased functional motor units, which was directly associated with increased expression of Hsp90 and Hsp70 [150]. This work is indicative of the potential for Hsp90 inhibitors as neuroprotective agents against ALS.

In a primary cell culture of motor neurons expressing mutant SOD1, the effect of the active form of HSF1 and of several Hsp90 inhibitors on cell viability and heat-shock protein expression was investigated. Motor neurons were microinjected with a plasmid encoding the active form of HSF1, and increased levels of heat-shock proteins were observed. Additionally, induced expression of the active form of HSF1 in motor neuron cell cultures co-expressing mutant SOD1 led to increased motor neuron survival and a reduced number of SOD1 inclusions [151]. The work summarized herein demonstrates the pharmacological potential of Hsp90 inhibitors for the treatment of ALS. Hsp90 inhibitors were able to protect motor neurons, delay disease progression and increase life expectancy in a mouse model of ALS, a disease for which few treatment options exist.

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system attacks the CNS. One of the primary pathological presentations of MS is the demyelination of axons in the CNS, resulting in electrical dysfunction of the information-carrying axons. Oligodendrocytes are the cells responsible for maintaining the myelin sheath and, in MS, both the cells and remylination become compromised. It has been postulated that destruction of the myelin sheath is the consequence of an immune system-mediated attack by lymphocytes that have gained unauthorized access to the CNS via the BBB. This attack results in activation of the inflammatory process and recruitment of other cells from the immune system [152,153]. Patients suffering with MS experience a myriad of symptoms but, most commonly, sensory, visual and motor impairments are observed. The prognosis of patients with MS largely depends upon the age at diagnosis and the type of MS diagnosed. There are various forms of treatment for patients with MS, the first of which is management of acute systematic attacks and the second is modification of the disease to prevent future attack. The first involves administration of corticosteroids, while the latter includes treatment with interferons, immunosuppresants or antibodies [153]. Hsp90 inhibitors have been implicated as a potential therapeutic alternative as heat-shock response is intimately involved with the inflammatory cascade.

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a useful model of MS, can be induced by administration of CNS-derived antigens and has been successfully accomplished in several species [154]. Mice primed to develop EAE treated with GDA demonstrated a decrease in disease development and, in a separate study, mice treated with 17-AAG after EAE disease onset exhibited diminished symptoms. In the same study, rat astrocytes and C6 glioma cells were treated with either GDA or 17-AAG and induction of heat-shock response was observed, simultaneous with a reduction in NOS2 mRNA levels. NOS2 is responsible for the production of nitric oxide and contributes to inflammation and the development of disease. Additionally, an increase in IκBα mRNA levels was observed in astrocytes treated with 17-AAG; IκBα is an inhibitory protein of the transcription factor NF-κB that controls many of the immune and inflammatory processes and may regulate the transcription of NOS2 [155]. Other in vitro studies in glial cells indicated that 17-AAG inhibited the inflammatory response to endotoxin lipopolysaccharide, as measured by reduced nitrite production and reduced IL-1β release [156].

Although the evidence is preliminary, Hsp90 inhibitors have potential therapeutic applications for MS. Hsp90 inhibitors were effective at slowing disease progression in mice models of EAE and they diminished symptoms if given after disease onset. These results have been reported to result from Hsp90’s mediation of the inflammatory cascade through transcriptional control of HSF1.

Polyglutamine diseases

Polyglutamine diseases (polyQ) are mainly inherited neurodegenerative diseases that are characterized by a CAG repeat in the gene encoding the deleterious protein. These expansions of glutamine cause protein misfolding and eventual aggregation resulting in neuronal toxicity. Nine inherited neurodegenerative diseases of this type have been identified, including spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), Huntington’s disease (HD), Machado-Joseph disease and spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA). Hsp90 inhibitors have been investigated as therapeutic strategies for several of the polyQ diseases, and initial results pertaining to SBMA and HD are discussed herein.

Spinal & bulbar muscular atrophy

Also known as Kennedy’s disease, SBMA mainly effects males and is thought to be linked to a polyQ expansion of the androgen receptor (AR) gene. Symptoms of this disease include gynecomastia, testicular failure, proximal muscular atrophy, weakness, and bulbar and limb muscle twitch [157], resulting from nuclear inclusions of mutant AR in the brainstem motor nuclei, spinal motor neurons, skin and testis of patients suffering from SMBA [158,159]. SMBA is an X-linked genetic disease and, consequently, effects men more often than women. Current treatments for SMBA include both disease-modifying and symptom-eleviating therapies and, as with other neurodegenerative diseases, attenuation of the molecular chaperone system has potential application for the treatment of SBMA. Unique to this neurodegerative disease is that the AR relies upon Hsp90 for its stabilization, regulation, degradation, nuclear translocation and ligand-binding affinity, and Hsp90 inhibitors have been shown to induce degradation of AR in various studies [160].

In a cultured neuronal model of SMBA, Hsp70 and Hsp40 overexpression resulted in reduced cytotoxicity and aggregate formation, accomplished by co-expressing Hsp70, Hsp40 and mutant AR [161,162]. In a similar study, cells expressing mutant AR and Hsp70 exhibited decreased levels of insoluble AR mutant protein. These cells also increased mutant AR degradation via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway [161,162]. In 2003, an animal model utilizing transgenic mice with both SMBA-like symptoms and Hsp70 overexpression corroborated in vitro observations. These mice had less motor impairment and reduced levels of mutant AR nuclear localization. Additionally, monomeric mutant AR was reduced, likely as a result of Hsp90-mediated ubiquitinylation and proteasomal degradation [163]. In a 2005 study, Waza et al. investigated the effects of 17-AAG on mutant AR protein aggregation in both cell culture and SMBA transgenic mice. In vitro, SH-SY5Y cells expressing mutant AR were treated with 17-AAG and exhibited decreased levels of mutant monomeric AR without alteration of AR mRNA levels. SMBA transgenic mice treated with 17-AAG also manifested less motor impairment compared with untreated mice. 17-AAG-treated mice also exhibited selective degradation of mutant AR in both the spinal cord and muscles compared with wild-type [164]. Hsp90 inhibitors that manifest the capacity to attenuate heat-shock protein levels may have therapeutic potential for treating SMBA, implicating Hsp90 as a viable target for polyQ diseases.

Huntington’s disease

Huntington’s disease is an inherited neurodegerative disease marked by a polyglutamine expansion of the gene encoding for huntingtin protein. After cleavage into fragments containing the polyglutamine repeat, the mutant huntingtin protein is susceptible to aggregation and manifests cytotoxicity, which leads to the pathogenesis of this disease. Pathologically, HD is characterized by neurodegeneration and atrophy in the corpus striatum, resulting in motor impairment, reduced coordination and, often, behavioral modification. As a result, the only clinical treatments for HD are symptomatic [165]. Similar to other neurodegenerative diseases, the pharmacological induction of heat-shock response offers a potential solution for the management of HD.

In 2000, transgenic Drosophila expressing a huntingtin-like protein comprised of an 127Q stretch, as a model for HD, were subjected to genetic screening to elucidate gene products that can modulate toxicity of the polyQ protein. HDJ1, the Drosophila homologue of Hsp40, was identified as a mediator of polyQ, because this protein suppressed polyQ toxicity [166]. After identification of a heat-shock protein as a modulator of mutant huntingtin toxicity, subsequent in vitro and in vivo models of HD were used to study the effects of heat-shock response on HD pathogenesis. Two different cell lines co-expressing a mutant huntingtin protein and a molecular chaperone, either GroEL (a bacterial chaperone) or Hsp104 (a yeast heat-shock protein), exhibited decreased aggregate formation and associated toxicity compared with cells expressing mutant huntingtin alone [167]. In another in vitro model, COS-1 cells expressing HDQ72 were treated with GDA, which manifested a dose-dependent inhibition of protein aggregation. Additionally, immunoblot analysis of these cells showed co-localization of both Hsp70 and Hsp40 with mutant huntingtin protein. Cells co-expressing mutant huntingtin and Hsp70 resulted in a 30–40% reduction in aggregation, while cells co-expressing both Hsp70 and Hsp40 produced a 60–80% decrease, indicating cooperativity between these two heat-shock proteins [168,169]. These data explain the disappointing results observed with a R6/2 transgenic mouse model of HD that overexpressed Hsp70 alone: Hsp70 was observed to be increased, however, there was little effect on the number and size of inclusions, brain weight, striatal volume or premature mortality [170]. The lack of activity observed by Hsp70 overexpression is presumably a consequence of not inducing the Hsp40 co-chaperone and therefore prohibiting Hsp70’s neuroprotective activity in this model. Schaffar and coworkers investigated the effects of an Hsp70/Hsp40 complex on mutant huntingtin and the effects on huntingtin coaggregation with other proteins. One of the proteins prone to coaggregation is the TATA box-binding protein, which is important for transcription activation. Hsp70/Hsp40 effectively inhibited deactivation of TATA box-binding protein by mutant huntingtin and prevented or minimized coaggregation [168]. Additionally, Hsp70 and Hsp40 were found to reduce the formation of spherical and annular oligomers of a mutant huntingtin fragment, which are believed to be precursors of fibril formation. Hsp70/Hsp40 appear to interact with monomeric mutant huntingtin, altering the conformation to one that is less prone to aggregation, most likely into spherical or annular oligomers [171]. In 2004, researchers evaluated the effect of Hsp90 inhibitors GDA and radicicol in the R6/2 mouse model of HD. Slice cultures from the hippocampal region of R6/2 were examined and it was observed that GDA and radicicol induced Hdj1 and Hsp70 expression, and modestly delayed the aggregation of huntingtin by increasing solubility of the huntingtin fragments. These studies, along with the other in vitro investigations of heat-shock response, demonstrate that Hsp90 inhibition may be a suitable target in the management of HD.

Conclusion

Hsp90 is a molecular chaperone responsible for the conformational maturation of nascent polypeptides and it may cooperate with Hsp70 to bring about the refolding of misfolded or denatured proteins. Inhibition of Hsp90 has the potential to treat unrelated disease states ranging from cancer to neurodegenerative diseases. Inhibition of Hsp90 by cytotoxic agents offers exciting promise for the treatment of cancer, which results in degradation of Hsp90-dependent client proteins directly associated with all six hallmarks of cancer. As a therapeutic target, Hsp90 inhibitors posses the ability to attack cancer through multiple signaling nodes simultaneously, resulting in a combinatorial attack that may be equivalent to the administration of multiple drugs. By contrast, modulation of Hsp90 by noncytotoxic small molecules results in disassembly of the HSF-1/Hsp90 complex, resulting in the overexpression of heat-shock proteins. The heat-shock proteins resulting from this response include Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp40 and Hsp27, and exhibit the ability to solubilize aggregated proteins that are often the causes or contributors to many neurodegenerative diseases. Consequently, Hsp90 represents a unique and exciting therapeutic target for the development of Hsp90 modulators that offer the potential to treat several disease states via a single protein target.

Future perspective

Hsp90 inhibitors for the treatment of cancer will be focused upon progress towards the development of agents that exhibit reduced toxicity compared with the ansamycin-based molecules, such as 17-AAG. Additionally, since cytotoxic inhibitors that bind the N-terminal ATP pocket induce heat-shock response, the scheduling of these drugs clinically will have to be thoroughly assessed, because each successive dose can result in increased Hsp90 levels. A potential alternative to the use of N-terminal inhibitors will be the development of cytotoxic C-terminal inhibitors, which do not induce the heat-shock response. As a consequence, these agents may be clinically more accessible and provide straightforward dosing and scheduling protocols.

The development of Hsp90 inhibitors for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases remains in its infancy. Significant investigations are necessary to determine the clinical relevance of Hsp90 modulators for the treatment of this class of diseases. Development of inhibitors that induce heat-shock response without cytotoxicity is of great interest to the Hsp90 community and will continue to be an active area of research. Perhaps the first Hsp90 inhibitor to be used for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases will enter clinical trials within the next few years and results obtained from these studies will be critical to future explorations that target these diseases via Hsp90 modulation.

Executive summary

The 90-kDa heat-shock protein (Hsp90) is a potential therapeutic target for cancer and several neurodegenerative diseases.

Inhibition of Hsp90 by cytotoxic agents results in the disruption of multiple signaling cascades associated with oncogenic progression.

Hsp90 is elevated in cancer cells and has higher affinity for Hsp90 inhibitors.

Hsp90 inhibitors are currently in clinical trials for the treatment of cancer and further progress is made towards Hsp90 inhibitors with reduced toxicity.

Modulation of Hsp90 by small-molecule inhibitors results in the induction of heat-shock response, which manifests therapeutic potential for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases caused by aggregation and toxicity of misfolded proteins.

Hsp90 inhibition has been shown to decrease tau levels, increase the levels of microtubule-associated tau, decrease tau aggregates, decrease Aβ aggregate levels and prevent Aβ aggregate formation and toxicity.

Hsp90 inhibition leads to a reduction in α-synuclein or Lewy body-induced toxicity associated with Parkinson’s disease.

Hsp90 inhibitors have also been implicated as potential therapeutics for the treatment of Huntington’s disease, spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy, multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Acknowledgments

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the NIH Training Grant (T32 GM008545) on Dynamic Aspects in Chemical Biology (Laura B Peterson) and NIH CA109265. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Glossary

- Hsp90

A 90-kDa molecular chaperone and heat-shock protein responsible for the post-translational maturation of proteins, solubilization of protein aggregates and refolding of misfolded proteins

- Cancer

A class of diseases characterized by uncontrolled growth, invasion and metastasis

- Neurodegenerative disease

Disease arising from cell death in the CNS that results in altered movement, sensory, memory and decision-making

- Molecular chaperone

A class of proteins involved in the folding and assembly of other proteins, including transcription factors, enzymes and receptors

- Heat-shock response

Cellular response to stress caused by increased temperature, alteration of pH or nutrient deprivation. Induced largely by the transcriptional events mediated by HSF1, which result in the upregulation of heat-shock protein family members

- Hsp90 Modulators

Small molecules capable of modulating Hsp90’s chaperone machinery

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Zhang H, Burrows F. Targeting multiple signal transduction pathways through inhibition of Hsp90. J Mol Med. 2004;82:488–499. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0549-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop SC, Burlison JA, Blagg BSJ. Hsp90: a novel target for the disruption of multiple signaling cascades. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:369–388. doi: 10.2174/156800907780809778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhury S, Welch TR, Blagg BSJ. Hsp90 as a target for drug development. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:1331–1340. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallo KA. Targeting Hsp90 to halt neurodegeneration. Chem Biol. 2006;13:115–116. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaacs JS, Xu WS, Neckers L. Heat shock protein as a molecular target for cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(3):213–217. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maloney A, Workman P. Hsp90 as a new therapeutic target for cancer therapy: the story unfolds. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2002;2(1):2–24. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meriin AB, Sherman MY. Role of molecular chaperones in neurodegenerative disorders. Int J Hyperther. 2005;21(5):403–419. doi: 10.1080/02656730500041871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly A, Blagg BSJ. Novobiocin and additional inhibitors of the Hsp90 C-terminal nucleotide binding pocket. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(26):2702–2717. doi: 10.2174/092986708786242895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Messaoudi S, Peyrat JF, Brion JD, Alami M. Recent advances in Hsp90 inhibitors as antitumor agents. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2008;8(7):761–782. doi: 10.2174/187152008785914824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taldone T, Gozman A, Maharaj R, Chiosis G. Targeting Hsp90: small-molecule inhibitors and their clinical development. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(4):370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearl LH, Prodromou C, Workman P. The Hsp90 molecular chaperone: an open and shut case for treatment. Biochem J. 2008;410:439–453. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soti C, Nagy E, Giricz Z, Vigh L, Csermely P, Ferdinandy P. Heat shock proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Brit J Pharmacol. 2005;146:769–780. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yonehara M, Minami Y, Kawata Y, Nagai Y, Yahara I. Heat-induced chaperone activity of HSP90. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2641–2645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richter K, Buchner J. Hsp90: chaperoning signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2001;188:281–290. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Workman P, Burrows F, Neckers L, Rosen N. Drugging the cancer chaperone Hsp90: combinatorial therapeutic exploitation of oncogene addiction and tumor stress. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1113:202–216. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solit DB, Chiosis G. Development and application of Hsp90 inhibitors. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13(12):38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratt WB, Toft DO. Regulation of signaling protein function and trafficking by the Hsp90/Hsp70-based chaperone machinery. Exp Biol Med. 2003;228:111–133. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer P, Prodromou C, Hu B, et al. Structural and functional analysis of the middle segment of Hsp90: implications for ATP hydrolysis and client protein and cochaperone interactions. Mol Cell. 2003;11:647–658. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiosis G, Vilenchik M, Kim J, Solit D. Hsp90: the vulnerable chaperone. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9(20):881–888. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sreedhar AS, Csermely P. Novel roles of Hsp90 inhibitors and Hsp90 in: redox regulation and cytoarchitecture. Rec Res Devel Life Sci. 2003;1:153–171. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitesell L, Lindquist SL. Hsp90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:761–772. doi: 10.1038/nrc1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen B, Piel WH, Gui L, Bruford E, Monteiro A. The Hsp90 family of genes in the human genome: insights into their divergence and evolution. Genomics. 2005;86:627–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sreedhar AS, Kalmar E, Csermely P. Hsp90 isoforms: functions, expression and clinical importance. FEBS Lett. 2004;562:11–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(04)00229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishna P, Gloor G. The Hsp90 family of proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:238–246. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0238:thfopi>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Csermely P, Schnaider T, Soti C, Prohaszka Z, Nardai G. The 90-kDa molecular chaperone family structure, function, and clinical applications. a comprehensive review. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;79(2):129–168. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorger PK, Pelham HR. The glucose-regulated protein grp94 is related to heat shock protein hsp90. J Mol Biol. 1987;194:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nemoto T, Sato N, Iwanari H, Yamashita H, Takegi T. Domain structures and immunogenic regions of the 90-kDa heat-shock protein (Hsp90) J Biol Chem. 1997;272(42):26179–26187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young JC, Schneider C, Hartl FU. In vitro evidence that Hsp90 contains two independent chaperone sites. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01363-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prodromou C, Pearl LH. Structure and functional relationships of Hsp90. Curr Cancer Drug Tar. 2003;3:301–323. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali MMU, Roe SM, Vaughan CK, et al. Crystal structure of an Hsp90–nucleotide–p23/Sba1 closed chaperone complex. Nat Med. 2006;440(20):1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature04716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dutta R, Inouye M. GHKL, an emergent ATPase/kinase superfamily. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:24–28. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergerat A, Massy Bd, Gadelle D, Varoutas P-C, Nicolas A, Forterre P. An atypical topoisomerase II from archaea with implications for meiotic recombination. Nature. 1997;386:414–417. doi: 10.1038/386414a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roe SM, Prodromou C, O’Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Structural basis for inhibition of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone by the antitumor antibiotics radicicol and geldanamycin. J Med Chem. 1999;42:260–266. doi: 10.1021/jm980403y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitesell L, Mimnaugh EG, De Costa B, Myers CE, Neckers LM. Inhibition of heat shock protein HSP90–pp60v–src heteroprotein complex formation by benzoquinone ansamycins: essential role for stress proteins in oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8324–8328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stebbins CE, Russo AA, Schneider C, Rosen N, Hartl FU, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of an Hsp90–geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent. Cell. 1997;89:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiosis G. Discovery and development of purine-scaffold Hsp90 inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6(11):1183–1191. doi: 10.2174/156802606777812013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nemoto T, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Ota M, Takagi T, Yokoyama K. Mechanism of dimer formation of the 90-kDa heat-shock protein. Eur J Biochem. 1995;233:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.001_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carrello A, Ingley E, Minchin RF, Tsai S, Ratajczak T. The common tetratricopeptide repeat acceptor site for steroid receptor-associated immunophilins and Hop is located in the dimerization domain of Hsp90. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(5):2682–2689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das AK, Cohen PTW, Barford D. The structure of the tetratricopeptide repeats of protein phosphatase 5: implications for TRP-mediated protein–protein interactions. EMBO J. 1998;17(5):1192–1199. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soti C, Vermes A, Haystead TAJ, Csermely P. Comparative analysis of the ATP-binding sites of Hsp90 by nucleotide affinity cleavage: a distinct nucleotide specificity of the C-terminal ATP-binding site. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:2421–2428. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcu MG, Schulte TW, Neckers L. Novobiocin and related coumarins and depletion of heat shock protein 90-dependent signalling proteins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):242–248. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itoh H, Ogura M, Komatsuda A, Wakui H, Miura AB, Tashima Y. A novel chaperone-activity-reducing mechanism of the 90-kDa molecular chaperone Hsp90. Biochem J. 1999;343:697–703. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huai Q, Wang H, Liu Y, Kim H-Y, Toft D, Ke H. Structures of the N-terminal and middle domains of E. coli Hsp90 and conformational changes upon ADP binding. Structure. 2005;13:579–590. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrarini M, Heltai S, Zocchi MR, Rugarli C. Unusual expression and localization of heat-shock proteins in human tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 1992;51(4):613–619. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910510418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nathan DF, Vos MH, Lindquist S. In vivo functions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp90 chaperone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12949–12956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider C, Sepp-Lorenzino L, Nimmesgern E, et al. Pharmacologic shifting of a balance between protein refolding and degredation mediated by Hsp90. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14536–14541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rabindran SK, Wisniewski J, Li L, Li GC, Wu C. Interaction between heat shock factor and Hsp70 is insufficient to suppress induction of DNA-binding activity in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(10):6552–6560. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi Y, Mosser DD, Morimoto RI. Molecular chaperones as HSF1-specific transcriptional repressors. Gene Dev. 1998;12:654–666. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trinklein ND, Murray JI, Hartman SJ, Botstein D, Myers RM. The role of heat shock transcription factor 1 in the genome-wide regulation of the mammalian heat shock response. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(3):1254–1261. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zou J, Guo Y, Guettouche T, Smith DF, Voellmy R. Repression of heat shock transcription factor HSF1 activation by Hsp90 (Hsp90 complex) that forms a stress-sensitive complex with HSF1. Cell. 1998;94:471–480. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zou J, Rungger D, Voellmy R. Multiple layers of regulation of human heat shock transcription factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(8):4319–4330. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim HR, Kang HS, Kim HD. Geldanamycin induces heat shock protein expression through activation of HSF1 in K562 erythroleukemic cells. IUBMB Life. 1999;48:429–433. doi: 10.1080/713803536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shamovsky I, Ivannikov M, Kandel ES, Gershon D, Nudler E. RNA-mediated response to heat shock in mammalian cells. Nature. 2006;440:556–560. doi: 10.1038/nature04518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ali A, Bharadwaj S, O’Carrol R, Ovsenek N. Hsp90 interacts with and regulates the activity of heat shock factor 1 in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4949–4960. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bharadwaj S, Ali A, Ovsenek N. Multiple components of the Hsp90 chaperone complex function in regulation of heat shock factor 1 in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8033–8041. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo Y, Guettouche T, Fenna M, et al. Evidence for a mechanism of repression of heat shock factor 1 transcriptional activity by a multichaperone complex. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45791–45799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marchler G, Wu C. Modulation of Drosophila heat shock transcription factor activity by the molecular chaperone DroJ1. EMBO J. 2001;20:499–509. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao C, Hashiguchi K, Kondoh W, Du W, Hata J, Yamada T. Exogenous expression of heat shock protein 90 kDa retards the cell cycle and impairs the heat shock response. Exp Cell Res. 2002;275:200–214. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitesell L, Bagatell R, Falsey R. The stress response: implications for the clinical development of Hsp90 inhibitors. Curr Cancer Drug Tar. 2003;3:349–358. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caplan AJ. What is a co-chaperone? Cell Stress Chaperones. 2003;8:105–107. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0105:wiac>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lotz GP, Lin H, Harst A, Obermann WM. Aha1 binds to the middle domain of Hsp90, contributes to client protein activation, and stimulates the ATPase activity of the molecular chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17228–17235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vaughan CK, Mollapour M, Smith JR, et al. Hsp90-dependent activation of protein kinases is regulated by chaperone-targeted dephosphorylation of Cdc37. 2008;31(6):886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Connell P, Ballinger CA, Jiang J, et al. The co-chaperone CHIP regulates protein triage decisions mediated by heat-shock proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:93–96. doi: 10.1038/35050618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murata S, Minami Y, Minami M, Chiba T, Tanaka K. CHIP is a chaperone-dependent E3 ligase that ubiquitylates unfolded protein. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:1133–1138. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hatakeyama S, Matsumoto M, Yada M, Nakayama KI. Interaction of U-box-type ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) with molecular chaperones. Genes Cells. 2004;9(6):533–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoffmann K, Handschumacher RE. Cyclophilin-40: evidence for a dimeric complex with hsp90. Biochem J. 1995;307(1):5–8. doi: 10.1042/bj3070005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pirkl F, Buchner J. Functional analysis of the Hsp90-associated human peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerases FKBP51, FKBP52 and Cyp40. J Mol Biol. 2001;308:795–806. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen S, Sullivan WP, Toft DO, Smith DF. Differential interactions of p23 and the TRP-containing proteins Hop, Cyp40, FKBP52 and FKBP51 with Hsp90 mutants. Cell Stress Chaperon. 1998;3(2):118–129. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0118:diopat>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen S, Smith DF. Hop as an adaptor in the heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and hsp90 chaperone machinery. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:35194–35200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johnson BD, Schumacher RJ, Ross ED, Toft DO. Hop modulates hsp70/hsp90 interactions in protein folding. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3679–3686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hernández MP, Chadli A, Toft DO. Hsp40 binding is the first step in the Hsp90 chaperoning pathway for the progesterone receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11873–11881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Minami Y, Minami M. Hsc70/Hsp40 chaperone system mediates the Hsp90-dependent refolding of firefly luciferase. Genes Cells. 1999;4:721–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Freeman BC, Morimoto RI. The human cytosolic molecular chaperones hsp90, hsp70 (hsc70) and hdj-1 have distinct roles in recognition of a non-native protein and protein refolding. EMBO J. 1996;15:2969–2979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Frydman J. Folding of newly translated proteins in vivo: the role of molecular chaperones. Ann Rev Biochem. 2001;70:603–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hutchison KA, Dittmar KD, Czar MJ, Pratt WB. Proof that hsp70 is required for assembly of the glucocorticoid receptor into a heterocomplex with hsp90. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5043–5049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alekseev OM, Widgren EE, Richardson RT, O’Rand MG. Association of NASP with HSP90 in mouse spermatogenic cells: stimulation of ATPase activity and transport of linker histones into nuclei. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2904–2911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen M-S, Silverstein AM, Pratt WB, Chinkers M. The tetratricopeptide repeat domain of protein phosphatase 5 mediates binding to glucocorticoid receptor heterocomplexes and acts as a dominant negative mutant. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32315–32320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Conde R, Xavier J, McLoughlin C, Chinkers M, Ovsenek N. Protein phosphatase 5 is a negative modulator of heat shock factor 1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(32):28989–28996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Silverstein AM, Galigniana MD, Chen MS, Owens Grillo JK, Chinkers M, Pratt WB. Protein phosphatase 5 is a major component of glucocorticoid receptor. hsp90 complexes with properties of an FK506-binding immunophilin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16224–16230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Catlett MG, Kaplan KB. Sgt1p is a unique co-chaperone that acts as a client adaptor to link Hsp90 to Skp1p. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(44):33739–33748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Millson SH, Vaughan CK, Zhai C, et al. Chaperone ligand-discrimination by the TPR-domain protein Tah1. Biochem J. 2008;413(2):261–268. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fan AC, Bhangoo MK, Young JC. Hsp90 functions in the targeting and outer membrane translocation steps of Tom70-mediated mitochondrial import. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33313–33324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Young JC, Hoogenraad NJ, Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones Hsp90 and Hsp70 deliver preproteins to the mitochondrial import receptor Tom70. Cell. 2003;112:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brychzy A, Rein T, Winklhofer KF, Hartl FU, Young JC, Obermann WM. Cofactor Tpr2 combines two TPR domains and a J domain to regulate the Hsp70/Hsp90 chaperone system. EMBO J. 2003;22:3613–3623. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moffatt NS, Bruinsma E, Uhl C, Obermann WM, Toft DO. Role of the cochaperone Tpr2 in Hsp90 chaperoning. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8203–8213. doi: 10.1021/bi800770g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jascur T, Brickner H, Salles-Passador I, et al. Regulation of p21(WAF1/CIP1) stability by WISp39, a Hsp90 binding TPR protein. Mol Cell. 2005;17:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Walter S, Buchner J. Molecular chaperones-cellular machines for protein folding. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2002;41:1098–1113. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020402)41:7<1098::aid-anie1098>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hohfeld J, Jentsch S. GrpE-like regulation of the Hsc70 chaperone by the anti-apoptotic protein BAG-1. EMBO J. 1997;16(20):6209–6216. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sondermann H, Scheufler C, Schneider C, Hohfeld J, Hartl FU, Moarefi I. Structure of a Bag/Hsc70 complex: convergent functional evolution of Hsp70 nucleotide exchange factors. Science. 2001;291:1553–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1057268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Forsythe HL, Jarvis JL, Turner JW, Elmore LW, Holt SE. Stable association of Hsp90 and p23, but not Hsp70, with active human telomerase. J Biol Chem. 2001;19(276):15571–15574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kosano H, Stensgard B, Charlesworth MC, McMahon N, Toft D. The assembly of progesterone receptor-Hsp90 complexes using purified proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(49):32973–32979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murphy PJM, Kanelakis KC, Galigniana MD, Morishima Y, Pratt WB. Stoichiometry, abundance, and functional significance of the Hsp90/Hsp70-based multiprotein chaperone machinery in reticulocyte lysate. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(32):30092–30098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Prodromou C, Panaretou B, Chohan S, et al. The ATPase cycle of Hsp90 drives a molecular ‘clamp’ via transient dimerization of the N-terminal domains. EMBO J. 2000;19(16):4383–4392. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ratajczak T, Carrello A. Cyclophilin 40 (CyP-40), mapping of its Hsp90 binding domain and evidence that FKBP52 competes with CyP-40 for Hsp90 binding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(6):2961–2965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ballinger CA, Connell P, Wu Y, et al. Identification of CHIP, a novel tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein that interacts with heat shock proteins and negatively regulates chaperone functions. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4535–4545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Workman P. Combinatorial attack on multistep oncogenesis by inhibiting the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cancer Lett. 2004;206:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Muchowski PJ. Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and neurodegeneration: a critical role for molecular chaperones? Neuron. 2002;35:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00761-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Muchowski PJ, Wacker JL. Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Neckers L. Chaperoning oncogenes: Hsp90 as a target of geldanamycin. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006;172:259–277. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29717-0_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jameel A, Skilton RA, Campbell TA, Chander SK, Coombes RC, Luqmani YA. Clinical and biological significance of Hsp89α in human breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1992;50(3):409–415. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910500315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yufu Y, Nishimura J, Nawata H. High constitutive expression of heat shock protein 90α in human acute leukemia cells. Leuk Res. 1992;16(6–7):597–605. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(92)90008-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chiosis G, Huezo H, Rosen N, Mimnaugh E, Whitesell L, Neckers L. 17AAG: low target binding affinity and potent cell activity – finding an explanation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104▪.Kamal A, Thao L, Sensintaffar J, et al. A high-affinity conformation of Hsp90 confers tumour selectivity on Hsp90 inhibitors. Nature. 2003;425:407–410. doi: 10.1038/nature01913. Demonstrates differential selectivity of cancer cells over normal cells by the 90-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) inhibitors due to high-affinity conformation of Hsp90 with inhibitors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schnur RC, Corman ML, Gallaschun RJ, et al. erB-2 oncogene inhibition by geldanamycin derivatives: synthesis, mechanism of action, and structure-activity relationships. J Med Chem. 1995;38:3813–3820. doi: 10.1021/jm00019a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schnur RC, Corman ML, Gallaschun RJ, et al. Inhibition of the oncogene product p185erbB-2 in vitro and in vivo by geldanamycin and dihydrogeldanamycin derivatives. J Med Chem. 1995;1995(38):3806–3812. doi: 10.1021/jm00019a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Banerji U, O’Donnell A, Scurr M, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4152–4161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Modi S, Stopeck AT, Gordon MS, et al. Combination of trastuzumab and tanespimycin (17-AAG, KOS-953) is safe and active in trastuzumab-refractory Her2 overexpressing breast cancer: a Phase I dose-escalation study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(34):5410–5417. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Solit DB, Osman I, Polsky D, et al. Phase II trial of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:8302–8307. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Banerji U. Preclinical and clinical activity of the molecular chaperone inhibitor 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin in malignant melanoma. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2003;44:677. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Neckers L, Ivy SP. Heat shock protein 90. Curr Opin Oncol. 2003;15:419–424. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sausville EA. Clinical development of 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin. Curr Cancer Drug Tar. 2003;3:377–383. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Banerji U. Heat shock protein 90 as a drug target: some like it hot. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:9–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Taldone T, Sun W, Chiosis G. Discovery and development of heat shock protein 90 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17(6):2225–2235. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sharp S, Workman P. Inhibitors of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone: current status. Adv Cancer Res. 2006;95:323–348. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)95009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Powers MV, Workman P. Inhibitors of the heat shock response: biology and pharmacology. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3758–3759. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.McDonald E, Workman P, Jones K. Inhibitors of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone: attacking the master regulator in cancer. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:1091–1107. doi: 10.2174/156802606777812004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ross CA, Poirier MA. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med. 2004:S10–S17. doi: 10.1038/nm1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer disease: mechanistic understanding predicts novel therapies. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:627–638. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, et al. GMCe: inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, et al. Diffusible, nonfibriallar ligands derived from Aβ1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tanzi RE, Bertram L. Twenty years of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell. 2005;120:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]