Abstract

Several pathologic conditions are associated with hemolysis, i.e. release of ferrous (Fe(II)) hemoglobin from red blood cells. Oxidation of cell-free hemoglobin produces (Fe(III)) methemoglobin. More extensive oxidation produces (Fe(III)/Fe(IV) O) ferryl hemoglobin. Both cell-free methemoglobin and ferryl hemoglobin are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of hemolytic disorders. We show hereby that ferryl hemoglobin, but not hemoglobin or methemoglobin, acts as a potent proinflammatory agonist that induces vascular endothelial cells in vitro to rearrange the actin cytoskeleton, forming intercellular gaps and disrupting the integrity of the endothelial cell monolayer. Furthermore, ferryl hemoglobin induces the expression of proinflammatory genes in endothelial cells in vitro, e.g. E-selectin, Icam-1, and Vcam-1, through the activation of the nuclear factor κB family of transcription factors. This proinflammatory effect, which requires actin polymerization, involves the activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase and the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. When administered to naïve mice, ferryl hemoglobin induces the recruitment of polymorphonuclear cells, demonstrating that it acts as a proinflammatory agonist in vivo. In conclusion, oxidized hemoglobin, i.e. ferryl hemoglobin, acts as a proinflammatory agonist that targets vascular endothelial cells.

O) ferryl hemoglobin. Both cell-free methemoglobin and ferryl hemoglobin are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of hemolytic disorders. We show hereby that ferryl hemoglobin, but not hemoglobin or methemoglobin, acts as a potent proinflammatory agonist that induces vascular endothelial cells in vitro to rearrange the actin cytoskeleton, forming intercellular gaps and disrupting the integrity of the endothelial cell monolayer. Furthermore, ferryl hemoglobin induces the expression of proinflammatory genes in endothelial cells in vitro, e.g. E-selectin, Icam-1, and Vcam-1, through the activation of the nuclear factor κB family of transcription factors. This proinflammatory effect, which requires actin polymerization, involves the activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase and the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. When administered to naïve mice, ferryl hemoglobin induces the recruitment of polymorphonuclear cells, demonstrating that it acts as a proinflammatory agonist in vivo. In conclusion, oxidized hemoglobin, i.e. ferryl hemoglobin, acts as a proinflammatory agonist that targets vascular endothelial cells.

Hemoglobin (Hb) is a tetrameric (α2β2) hemoprotein that accounts for 97% of the total dry content of red blood cells in mammals, where it acts essentially as a gas sensor/carrier (for review, see Ref. 1). When confined inside red blood cells, α2β2 Hb tetramers are kept in a reduced (Fe(II)/ferrous) form (for review, see Ref. 1). However, there are a variety of pathological conditions, e.g. malaria (caused by Plasmodium infection), dengue hemorrhagic fever (caused by Flavivirus infection), trauma, ischemia reperfusion injury, organ transplantation, renal failure, sickle cell anemia, or thalassemias, that are associated with hemolysis (for review, see Ref. 2). When hemolysis occurs, cell-free Hb α2β2 tetramers dissociate into αβ dimers, which are oxidized into ferric (Fe(III)) Hb, i.e. methemoglobin (MtHb)7 (3, 4). Sustained exposure of cell-free Hb to reactive oxygen species, e.g. H2O2, can lead to the formation of (Fe(IV) O) Hb, referred to here as ferrylHb (5, 6). This unstable oxidized form of Hb can return to the ferric (Fe(III)) state through protein electron transfer in which tyrosine 42 in the Hb α chains acts as a redox center, cycling between the tyrosine and the tyrosyl radical while delivering electrons to ferryl heme (6–8). Tyrosyl radicals can form covalent dityrosine bonds leading to inter- and intramolecular cross-linking and to ferrylHb polymerization (7, 9). In addition, tyrosyl radicals can catalyze other reactions, in which oxidation products are released via fragmentation and/or proteolysis (10). Although ferrylHb is thought to act in a pro-oxidant and cytotoxic manner (11) its pathophysiological effects remain poorly understood. We reasoned that because of the physical location at the interface between blood and tissues, vascular endothelial cells (EC) might be the main cellular target for putative pathophysiological effects of ferrylHb.

O) Hb, referred to here as ferrylHb (5, 6). This unstable oxidized form of Hb can return to the ferric (Fe(III)) state through protein electron transfer in which tyrosine 42 in the Hb α chains acts as a redox center, cycling between the tyrosine and the tyrosyl radical while delivering electrons to ferryl heme (6–8). Tyrosyl radicals can form covalent dityrosine bonds leading to inter- and intramolecular cross-linking and to ferrylHb polymerization (7, 9). In addition, tyrosyl radicals can catalyze other reactions, in which oxidation products are released via fragmentation and/or proteolysis (10). Although ferrylHb is thought to act in a pro-oxidant and cytotoxic manner (11) its pathophysiological effects remain poorly understood. We reasoned that because of the physical location at the interface between blood and tissues, vascular endothelial cells (EC) might be the main cellular target for putative pathophysiological effects of ferrylHb.

Under inflammatory conditions EC become activated, promoting vasoconstriction and thrombosis as well as leukocyte chemotaxis, adhesion, and transmigration (for review, see Ref. 12). This proinflammatory response results from the expression of immediate-early responsive genes encoding vasoconstrictive (e.g. endothelin 1/2), pro-thrombotic (e.g. tissue factor), proinflammatory (e.g. interleukin-1 and -6), and chemotactic (e.g. interleukin-8) as well as adhesive (e.g. intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1/CD54), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1/CD106), E-selectin/CD62E, and P-selectin/CD62P molecules (for review, see Ref. 12). Expression of these genes is regulated primarily at the transcriptional level via activation of the nuclear factor κ B (NF-κB) family of transcription factors (13, 14).

NF-κB comprises five family members, i.e. NF-κB1/p105, NF-κB2/p100, RelA/p65, RelB, and c-Rel that can form active homo- or heterodimers (for review, see Ref. 15). Under homeostasis, these NF-κB dimers are kept in an inactive form based on their constitutive sequestration by cytoplasmic inhibitors of NF-κB molecules, namely IκBα (16), IκBβ, IκBγ IκBϵ, and Bcl-3 (for review, see Ref. 15). Most proinflammatory agonists that elicit EC activation target IκB molecules for phosphorylation (17), ubiquitination (18), and proteolytic degradation by the 26 S proteasome pathway (19, 20). This allows for rapid nuclear translocation and binding of the NF-κB dimers to DNA “κB motifs” in the promoter of NF-κB-dependent genes (for review, see Ref. 15). Some NF-κB family members, such as p65/RelA, must be further phosphorylated (21) (for review, see Ref. 22) to elicit transcriptional activity as well as to afford specificity for subsets of NF-κB-dependent genes (21).

As reported hereby, ferrylHb acts as a proinflammatory agonist in EC through activation of the NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling transduction pathways. Based on this observation we propose that oxidized cell-free Hb might contribute to the pathologic outcome of hemolytic disorders.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

Wild type and Tlr2−/−, 4−/−, and 9−/− C57BL/6 mice were maintained at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with guidelines from the Animal User and Institutional Ethical Committees of this institute. Mice were used between 6 and 8 weeks of age. Tlr2−/−, 4−/−, and 9−/− mice were provided originally by Dr. Shizuo Akira Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University, Japan.

Cell Culture

Pooled human umbilical vein EC (HUVEC; Clonetics, Zurich, Switzerland or VEC Technologies Inc., Herndon, VA) were cultured on gelatinized plates in EBM-2 (Cambrex BioScience, Wokingham, UK) supplemented with 1% heparin, 0.04% hydrocortisone, 50 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate/amphotericin, 0.1 ng/ml ascorbic acid, 0.5% human fibroblast growth factor B, 0.1% human recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor, 0.1% human recombinant epidermal growth factor, 0.1% insulin-like growth factor, and 2% heat-inactivated FCS (Clonetics). HUVEC were passaged 1/3 and used between passages 4 and 5 2 days post-confluence. Murine monocytic cell line J774 (ECACC) was cultured in complete RPMI (10% FCS, 2 mm l-glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). Bone marrow-derived monocyte/macrophages (Mø) were obtained from naive BALB/c mice by flushing the marrow from femurs and tibias. The marrow plugs were disrupted into a single cell suspension and cultured in RPMI (20% FCS, 2 mm l-glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 30% supernatant from L929 cells) for 6 days. On day 6 of culture cells were cultured in complete RPMI (10% FCS) and used on day 7 in the experimental assays.

Hb Solutions

Hb at different redox states, i.e. (Fe(II)) Hb, (Fe(III)) MtHb, and ferrylHb, were prepared as described (3). Briefly, Hb was isolated from fresh blood drawn from healthy volunteers using ion-exchange chromatography on a DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B column (Sigma-Aldrich). MtHb was generated by incubation (30 min, 25 °C) of purified Hb with a 1.5-fold molar excess of K3Fe(CN)6 (Sigma-Aldrich) over heme. FerrylHb was obtained by incubation (1 h, 37 °C) of Hb with a 10-fold H2O2 molar excess (Sigma-Aldrich) over heme. After oxidation, both MtHb and ferrylHb were dialyzed (3×, 3 h, 100× saline volume, 4 °C) to remove K3Fe(CN)6 and H2O2, separated into aliquots, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until used. Purity of each Hb preparation was evaluated by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining. Hb polymerization was detected by Western blot using a chicken anti-human polyclonal Hb antibody (ab17542, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Hb redox state was assessed by UV-visible spectra recorded on a Shimadzu UV-3100 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Duisburg, Germany) with 1-cm quartz cells (Hellma, Jena, Germany). Hb dityrosine content was detected by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence detection as described (10). Briefly, 100 nmol of Hb was precipitated with 20% of trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation (5 min, 1500 × g) the pellet was hydrolyzed overnight (100 °C in 6 mol/liter hydrochloric acid), the liquid was evaporated, and the residue was dissolved in methanol and injected to HPLC using a reverse phase C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5-mm particle size) and fluorescence detection (λEx = 280 nm, λEm = 410 nm, Merck). The mobile phase consisted of 20% methanol and 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid in water. The flow rate was 1 ml/min. All reagents were HPLC grade (Merck). Dityrosine standard was prepared as described (10). Briefly, 10 mmol/liter l-tyrosine was reacted with 1 mmol/liter H2O2 in the presence of 1 μmol/liter horseradish peroxidase at pH 9.5 for 18 h at 37 °C. The enzyme was removed by ultrafiltration, and the filtrate was evaporated. The residue was dissolved in ethanol and chromatographed on a silica thin layer plate (20 × 20 cm) with an eluent of butanol:acetic acid:water (4:2:1 v/v%). The fluorescent band with an RF = 0.25 was excised and extracted with methanol and used as a dityrosine standard. Protein concentration in Hb preparations was determined spectrophotometrically, as described (4). Endotoxin content was analyzed by Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Bio Whittaker, Inc., Walkersville, MD). To measure H2O2 concentration, ferrylHb was filtered (Microcon YM-3 column; Millipore) (60 min at 14 °C, 21,000 × g) to remove proteins (molecular mass > 3 kDa), and the H2O2 in flow-through was measured using a fluorometric detection kit (Assaydesign; Stressgen) in three different preparations of ferrylHb in triplicate.

Cell Treatments and Reagents

Polymyxin B sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) was mixed (15–30 μg/ml) with vehicle, ferrylHb (20 μm), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (100 ng/ml) (30 min, 37 °C). LPS (Escherichia coli serotype 0127:B8) (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen). Catalase (Calbiochem, Merck) was incubated with ferrylHb or vehicle (30 min, 37 °C). Hemin (iron protoporphyrin IX) (Frontier Scientific Inc., Logan, UT) was prepared as described (23). c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor 1 (l-stereoisomer, Alexis Biochemicals, Lausanne, Switzerland) and p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (Calbiochem) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and added to the culture medium 30 min before further treatment and left until the end of the experiments. Cytochalasin D and latrunculin B (LatB) (Calbiochem) were dissolved in DMSO and added to the culture medium 30 min before ferrylHb or LPS and left until the end of the experiments. Jasplakinolide (Calbiochem) was dissolved in DMSO. Actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in PBS (100 μg/ml) and added to culture medium 30 min before the addition of ferrylHb or LPS and left until the end of the assay. Cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in ethanol (100 μg/ml) and added to culture medium at 10 μg/ml. Human recombinant TNF (Research and Development, Minneapolis, MN) was diluted in PBS, 0.1% bovine serum albumin and added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 50 ng/ml. Pervanadate (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared as described (24).

Immunocytochemistry

Confluent HUVEC grown in gelatinized glass coverslips were washed in PBS, fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (20 min, 25 °C), and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). F-actin and DNA were stained with TRITC-labeled phalloidin (50 ng/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (20 ng/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), respectively. Cells were analyzed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMRA2, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Fluorescence was detected at λEx = 535/50 nm and λEm = 610/75 nm for TRITC, λEx = 480/50 nm and λEm = 527/30 nm for ferrylHb, and λEx = 360/40 nm and λEm = 470/40 nm for 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Images were acquired using Metamorph v4.6r5 software (Universal Imaging Corp., Downingtown, PA) and analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH; Bethesda, MD).

siRNA and Transient Transfections

p38 siRNA (sc-29433) and control siRNA (sc-36869, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), JNK1, and JNK2 siRNAs (l-003514-00 and l-003505-00, Dharmacon, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used at 50 pmol/well of a 12-well plate. HUVEC were transfected at 75–85% confluence according to the Invitrogen siRNA protocol for HUVEC. Briefly, 50 pmol of siRNA were mixed with 4 μl of Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) in 100 μl of serum free EBM-2 and incubated for 20 min at 25 °C. During this period the growth medium from HUVEC was removed, and cells were placed in 400 μl of serum free EBM-2. Then 100 μl of Oligofectamine/siRNA transfection mixture was added per well (3 h), and transfection was stopped (250 μl of complete EBM-2 containing 6% FCS). Transfection efficiency (typically 90–100%) was monitored 24 h thereafter, and medium was replaced by complete EBM-2, 2% FCS. All experiments were carried out 72 h after siRNA transfections.

Recombinant Adenovirus Transduction and Reporter Assays

HUVEC at 80–90% confluence were co-transduced with recombinant adenovirus encoding a NF-κB luciferase reporter (Photinus pyralis luciferase gene under the control of a synthetic promoter containing five binding motifs for NF-κB (5′-GGGGACTTTCC-3′; NF-κB-luc), IκBα dominant negative mutant (IκBα-S32A/S36A; IκBα DNM)(Vector Biolabs, Philadelphia, PA) plus a recombinant adenovirus encoding β-galactosidase (LacZ) (a kind gift from Dr. R. Gerard; University of Texas Southwest Medical Center, Dallas, TX) essentially as described (14, 25). Experiments were performed 48 h after adenovirus transduction. Luciferase expression was quantified using a single (firefly) luciferase assay system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). β-Galactosidase expression was quantified using Galacto-Light Plus β-Galactosidase Reporter Gene Assay System according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Tropix Inc., Bedford, MA). Both luciferase and β-galactosidase were measured using a Microlumat Plus luminometer (LB96V, Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Assays were performed in triplicate, and luciferase values were normalized to β-galactosidase. Normalized luciferase activity is shown in arbitrary units.

ELISA

VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin protein expression were measured by cellular ELISA, as described elsewhere (25). IL-8 was detected using human IL-8 ELISA (BD Biosciences). Murine IL-6 and TNF were detected with mouse IL-6 and TNF ELISA sets, respectively (BD Biosciences).

Oxidative Stress

Intracellular free radical content was measured by flow cytometry using 5 μm 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate acetyl ester (CM-H2DCFDA, Molecular Probes) as described (26). Cellular thiobarbituric acid reactive substances were measured according to the manufacturer's instructions (OXI-TEC, Alexis, Nottingham, UK).

Cell Extracts and Western Blot Analysis

HUVEC were lysed (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm Na2EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich)), and proteins were resolved (8–12% SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blotted with antibodies directed against human E-selectin (sc-14011, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), VCAM-1 (sc-8304, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), ICAM-1 (BBA3, R&D Systems), p65/RelA (sc-372, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-p65-Ser-536 (#3031, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), IκBα (sc-371, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-IκBα-Ser-32/36 (#9246, Cell Signaling), stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK)/JNK (#9252, Cell Signaling), phospho-SAPK/JNK-Thr-183/Tyr-185 (#9251, Cell Signaling), p38 (#9212, Cell Signaling), phospho-p38-Thr-180/Tyr-182 (#9211, Cell Signaling), or anti-IκBα-phospho-Tyr-42 antibody (ab24783, Abcam). To ascertain equivalent protein loading, membranes were stripped and re-probed with a mouse anti-human α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (T9026, Sigma-Aldrich). Lamin A/C monoclonal antibody (sc-7292, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as a loading control in nuclear extracts. Primary antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (Pierce). Peroxidase activity was visualized using the SuperSignal® West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce). Digital images were obtained using Kodak Image Station 440CF apparatus (Eastman Kodak Co.). Images were captured using Adobe Photoshop® software, and relative levels of protein expression were quantified using ImageJ® 1.29 software (National Institutes of Health).

Quantitative Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

cDNA was obtained from total RNA isolated from HUVEC or mouse livers, as described (26, 27). The relative number of mRNA transcripts was assessed using Light Cycler real-time quantitative PCR (Roche Applied Science) using FastStart DNA SYBR Green I mix (Roche Applied Science). Transcript number was calculated using a 2−ΔΔCT method (relative number) or quantified as an absolute value using standard cDNA plasmids encoding the same sequences as those amplified by PCR. Results were normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine-phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt). PCR primers used to quantify human mRNA transcripts were: 5′-GGAGAACCCAGATAGACAG-3′ and 5′-CCTTCACATAAATAAACCCC-3′ for Vcam-1, 5′-TCACCTATGGCAACGACTC-3′ and 5′-GATGGGCAGTGGGAAAGTG-3′ for Icam-1, 5′-ATGTGGAATGATGAGAGGTG-3′ and 5′-AACTGGGATTTGCTGTGTC-3′ for E-selectin, and 5′-GGCGTCGTGATTAGTGATG-3′ and 5′-ACTTCGTGGGGTCCTTTTC-3′ for Hprt. PCR primers used to quantify murine mRNA transcripts were described elsewhere (26).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Two days post-confluent HUVEC were exposed to ferrylHb (20 μm; 6 h), and nuclear extracts were prepared as described (14). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay was performed with the IgκB probe (sense 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′). The oligonucleotide was labeled by phosphorylation with [γ-32P]ATP. Mobility shift was visualized in the form of autoradiographs.

Viability Assays

HUVEC were treated with ferrylHb (20 μm) or cycloheximide plus TNF (8 h), a potent pro-apoptotic stimulus to EC (27). Cells were washed in PBS and detached (37 °C, 5 min) with 0.125% trypsin, 0.05% EDTA solution (Invitrogen). Digestion was stopped (PBS, 10% FCS), and cells were pelleted (200 × g, 4 °C, 3 min), washed (PBS, 3% FCS), and co-stained with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated annexin V (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) plus propidium iodide (0.5 μg/ml, P-4170, Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Annexin V and propidium iodide fluorescence were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc. Ashland, OR). Alternatively, viability was assessed by a crystal violet assay as described (14).

Mouse Peritonitis

C57BL/6 mice (female, 6–8 weeks of age) were injected intraperitoneally with 2 μmol/kg Hb, MtHb, or ferrylHb in 200 μl of apyrogen PBS. Control mice received PBS only. After 16 h mice were sacrificed by CO2 exposure, and murine peritoneal leukocytes were harvested by peritoneal lavage using ice-cold apyrogen calcium and magnesium-free PBS containing 2% FCS (v/v) and analyzed by flow cytometry. The total number of cells was assessed using a fixed number of latex beads (Beckman Coulter, Paris, France) and co-acquired with a pre-established volume of the cellular suspensions. The number of peritoneal polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells was evaluated using R-phycoerythrin-conjugated rat anti-mouse Ly-6G (Gr1; CD11b) (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) and biotin anti-mouse neutrophils monoclonal antibody (CL8993B, Cedarlane, Hornby, Ontario, Canada). Cells were co-stained with propidium iodide (0.5 μg/ml) to exclude dead cells. Fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry, and data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± S.D. or S.E. of independent in vitro or in vivo experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student's t test when the data follow Gaussian distributions, an assumption tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov method. When the data do not follow Gaussian distributions, the Mann-Whitney U test was used instead. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test were used for comparison between values from more than two different groups. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

FerrylHb Induces Actin Rearrangement and Intercellular Gap Formation in EC

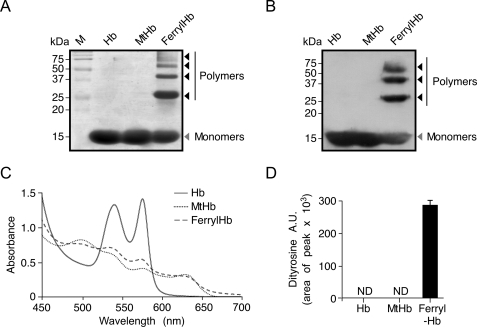

Cell-free ferrous Hb was purified from human blood of healthy donors and used to generate MtHb and ferrylHb (4). Relative purity of each Hb preparation was higher than 95%, as determined by silver staining after SDS/PAGE separation (Fig. 1A). Contrary to Hb and MtHb, ferrylHb polymerized, as detected by silver staining (Fig. 1A) and Western blot (Fig. 1B), which is consistent with previous reports (28). Ferrous Hb was in the reduced state, whereas MtHb and ferrylHb were in the oxidized state, as assessed by spectrophotometry (Fig. 1C). FerrylHb contained dityrosine groups, as detected by HPLC (Fig. 1D), whereas dityrosine groups were undetectable in Hb or MtHb (Fig. 1D). Presumably, formation of dityrosine bonds accounts for ferrylHb polymerization (Fig. 1, A and B) (28).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of purified Hb, MtHb, and ferrylHb solutions. Purified human Hb, MtHb, and ferrylHb (20 μm each) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and silver stained (A) or transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (B), and Hb α chains were detected by Western blot using an anti-Hb α antibody. M indicates protein molecular mass standards. C, visible spectra of Hb, MtHb, and ferrylHb showing reduced (Fe(II)) ferrous Hb versus oxidized (Fe(III)) MtHb and ferrylHb. D, dityrosine content in Hb, MtHb, and ferrylHb detected by HPLC. Results are shown as mean arbitrary units (A.U.) ± S.D. (n = 3 samples). ND indicates not detectable.

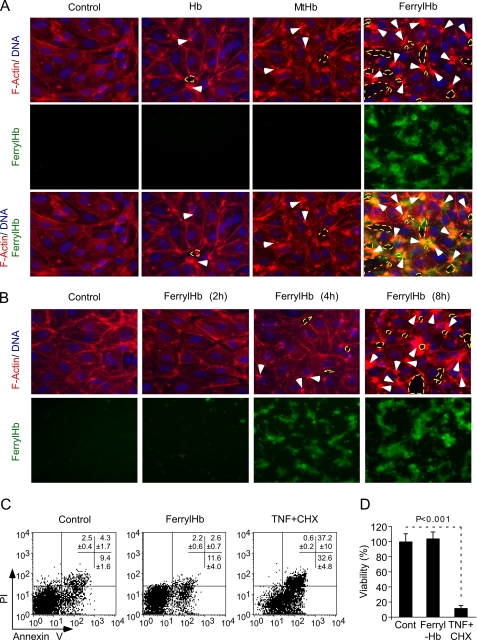

To assess whether cell-free Hb exerts biologic effects on vascular EC, post-confluent HUVEC were exposed in vitro to ferrous Hb, MtHb, or ferrylHb and analyzed by fluorescent microscopy. FerrylHb induced actin polymerization in EC, as revealed by the formation of filamentous actin (F-actin) bundles, i.e. stress fibers, in areas juxtaposed to the deposition of ferrylHb aggregates (Fig. 2, A and B). Neither Hb nor MtHb led to the formation of F-actin stress fibers in EC (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, ferrylHb, but not ferrous Hb or MtHb, led to the formation of intercellular gaps that disrupted the integrity of the EC monolayer (Fig. 2, A and B). Overlay of ferrylHb aggregates with F-actin and intercellular gaps (Fig. 2A) suggests that these events might be functionally linked; namely, that aggregation of ferrylHb triggers actin polymerization and formation of intercellular gaps. These effects of ferrylHb were not associated with EC apoptosis, and/or necrosis, as assessed by surface phosphatidylserine expression or permeability to propidium iodide (Fig. 2C) and as confirmed by crystal violet (vital) staining (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

FerrylHb disrupts EC monolayer integrity. A, confluent HUVEC were exposed (8 h) to Hb, MtHb, or ferrylHb (20 μm) or vehicle (control). F-actin (phalloidin-TRITC; red), DNA (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, blue), and ferrylHb auto fluorescence (green) are shown. B, confluent HUVEC were exposed to ferrylHb or vehicle (control) and stained as in A. White arrows in A and B indicate F-actin bundles, and dashed yellow circles indicate intercellular gaps; images are 400×, representative of three independent experiments, each in triplicate. C, confluent HUVEC were untreated (Control) or exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm) or cycloheximide (CHX; 10 μg/ml) plus TNF (50 ng/ml). Viability was assessed by annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining and monitored by flow cytometry. D, HUVEC were treated as in C, and viability was assessed by crystal violet staining. Data show the mean ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 3 independent experiments. p value was calculated using unpaired Student's t test.

FerrylHb Induces the Expression of Proinflammatory Genes in EC

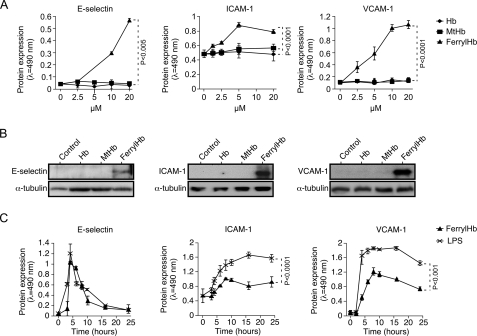

When exposed to ferrylHb in vitro, EC up-regulated the expression of the proinflammatory adhesion molecules E-selectin (CD62), ICAM-1 (CD54), and VCAM-1 (CD106), as assessed by cellular ELISA (Fig. 3A) and Western blot (Fig. 3B). This effect was dose-dependent in that increasing concentrations of ferrylHb led to higher levels of expression of these adhesion molecules (Fig. 3A). When used at the same concentrations, neither ferrous Hb nor MtHb induced the expression of these adhesion molecules in EC (Fig. 3, A and B).

FIGURE 3.

FerrylHb induces the expression of adhesion molecules in EC. A, confluent HUVEC were exposed (8 h) to increasing concentration of Hb, MtHb, ferrylHb, or vehicle, and E-selectin, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 protein expression was detected by cellular ELISA. B, confluent HUVEC were exposed (8 h) to Hb, MtHb, or ferrylHb (20 μm), and E-selectin, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 protein expression was detected in whole cell lysates by Western blot. Immunoblots are representative of three independent experiments. C, confluent HUVEC were exposed to ferrylHb (20 μm) or LPS (100 ng/ml), and E-selectin, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 protein expression was detected by cellular ELISA. Results in A and C are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 3 independent experiments. ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test were used to calculate p values in A. p values in C were calculated by using unpaired Student's t test.

We compared the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb to that of a well established proinflammatory agonist, namely LPS (29). FerrylHb (20 μm) and LPS (100 ng/ml) induced similar levels of E-selectin expression in EC (Fig. 3C), with maximal protein expression occurring within 4–5 h after ferrylHb or LPS exposure, followed by a decrease to basal levels 16–24 h thereafter (Fig. 3C). Induction of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression by ferrylHb was significantly lower, as compared with LPS (Fig. 3C), even though the kinetic of expression of these adhesion molecules was quite similar (Fig. 3C).

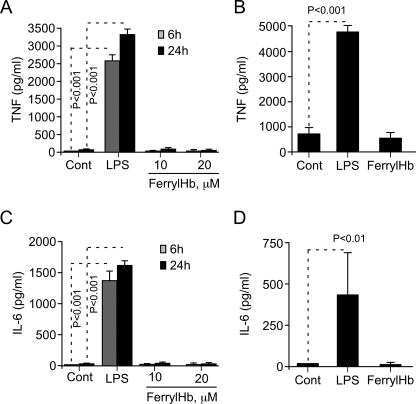

When exposed to ferrylHb, Mø did not induce the expression of proinflammatory genes as assessed for TNF (Fig. 4, A and B) and IL-6 (Fig. 4, C and D), two proinflammatory cytokines that play an essential role in the effector phase of inflammatory responses. Similar results where obtained using either primary Mø (bone marrow-derived) (Fig. 4, A and C) or the monocytic cell line J774 (Fig. 4, B and D). This suggests that the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is somehow restricted to EC.

FIGURE 4.

FerrylHb does not evoke a proinflammatory response in Mø. A, bone marrow-derived Mø were left untreated (Cont) or exposed to LPS (10 ng/ml) or to ferrylHb. TNF concentration in cell culture supernatant was measured by ELISA. B, the monocytic J774 cell line was left untreated or exposed to LPS (100 ng/ml; 24 h) or ferrylHb (20 μm; 24 h). TNF concentration was measured as in A. Bone marrow-derived Mø (C) or monocytic J774 cells (D) were treated as in A and B, respectively, and IL-6 concentration was measured in cell culture supernatant by ELISA. Results are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3) from one representative experiment of three. p values were calculated using ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test.

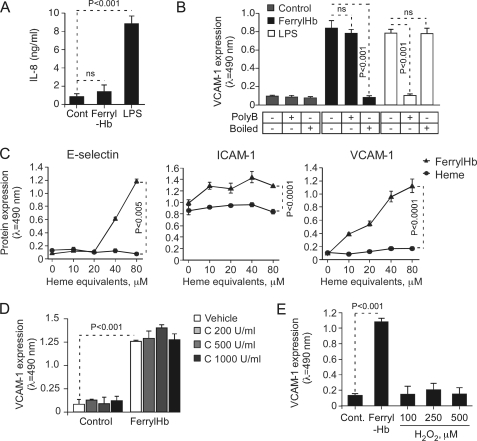

We tested whether ferrylHb induces the expression of proinflammatory genes other than those encoding for adhesion molecules. Contrary to LPS, however, ferrylHb failed to induce the expression/secretion of the chemokine IL-8 in EC (Fig. 5A). This suggests that ferrylHb and LPS induce the expression of different subsets of proinflammatory genes in EC, presumably acting via distinct mechanisms.

FIGURE 5.

The proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is not attributable to putative contaminants. A, confluent HUVEC were exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm) or LPS (100 ng/ml), and IL-8 concentration in culture supernatant was measured by ELISA. Results shown are the mean values ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 4 independent experiments. B, HUVEC were treated as in A, and when indicated (+) ferrylHb and LPS where preincubated (30 min) with polymixin B (polyB) or subjected to heat inactivation (80 °C; 20 min). VCAM-1 protein expression was measured by cellular ELISA. Results shown are the mean values ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 4 independent experiments. n.s., not significant. C, confluent HUVEC were exposed to equivalent molar amounts of ferrylHb or heme, and E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 protein expression was detected by cellular ELISA. Results shown are the mean values ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 3 independent experiments. D, confluent HUVEC were treated with vehicle alone or vehicle exposed to catalase (37 °C; 30 min) (Control) or to ferrylHb (8 h; 20 μm) alone or ferrylHb exposed to catalase. VCAM-1 protein expression was measured by cellular ELISA. Results are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 3 independent experiments. E, confluent HUVEC were left untreated (Cont) or exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm) or to H2O2, and VCAM-1 expression was measured by cellular ELISA. Results shown are the mean values ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 3 independent experiments. p values shown in A, B, D, and E were calculated using ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. p values in C were calculated by using unpaired Student's t test.

The Proinflammatory Effect of FerrylHb Is Not because of Putative Contaminants

Cell-free Hb can synergize with LPS (30, 31), raising the possibility that the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb might be because of a putative contamination by LPS, i.e. endotoxin. This possibility was discarded based on the following set of observations. First, the endotoxin content of purified ferrylHb was <2 pg/ml, which fails to induce the expression of proinflammatory genes in EC (32). Second, polymyxin B, a molecule that binds to and inactivates endotoxin (33), did not suppress the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb but did so for LPS, as assessed by VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 5B). Third, heat denaturation suppressed the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb but did not interfere with that of LPS, as assessed by VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 5B). These observations support the notion that ferrylHb induces the expression of proinflammatory genes in EC via a mechanism that is not attributable to a putative endotoxin contamination.

We tested whether the proinflammatory effects of ferrylHb could be attributed to heme release from ferrylHb, which could act as a proinflammatory agonist in EC (34). However, free heme failed to induce the expression of E-selectin, ICAM-1, or VCAM-1 in EC (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is not attributable to heme release from its globin chains. In keeping with this notion, MtHb, which can release its heme groups as does ferrylHb (3, 34), fails to induce the expression of E-selectin, ICAM-1, or VCAM-1 in EC (Fig. 3, A and B).

Because ferrylHb is generated through oxidation of ferrous Hb by H2O2, we asked whether the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is because of trace amounts of H2O2 that could synergize with ferrylHb to support this effect. We have excluded this possibility based on the observation that (i) purified ferrylHb contains less than 1 nm H2O2, (ii) preincubation of ferrylHb with catalase, an enzyme that converts H2O2 into H2O, did not suppress the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb, as assessed by VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 5D), and (iii) H2O2 (100–500 μm) failed to induce the expression of VCAM-1 in EC (Fig. 5E).

FerrylHb induced a mild accumulation of free radicals in EC, as detected by flow cytometry using the free radical probe 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate acetyl ester (supplemental Fig. 1A) as well as by the production of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, a marker of lipid peroxidation (supplemental Fig. 1B). However, the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb was not inhibited by the antioxidants N-acetylcysteine or butylated hydroxyanisole (tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole) (supplemental Fig. 1C–E), suggesting that accumulation of free radicals is not a major mechanism via which ferrylHb exerts its proinflammatory effects in EC.

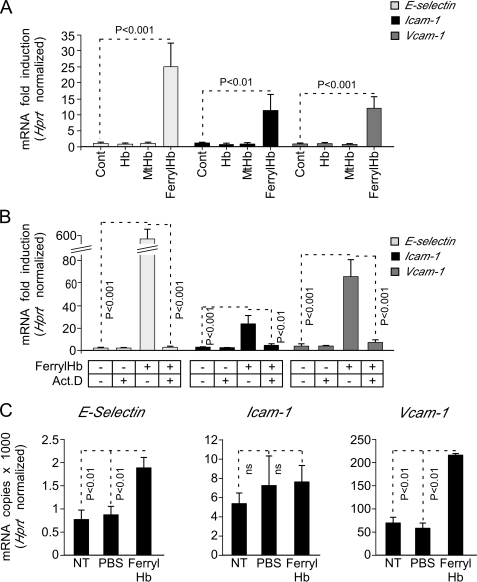

The Proinflammatory Effect of FerrylHb Is Regulated Transcriptionally

Upon exposure to ferrylHb, EC up-regulated the expression of mRNAs encoding E-selectin, Icam-1, and Vcam-1, as assessed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 6A). Expression of these mRNAs increased from 2 to 5 h after ferrylHb exposure, decreasing thereafter to regain basal levels (data not shown). FerrylHb did not modulate the expression of mRNA encoding Hprt. Moreover, neither ferrous Hb nor MtHb induced the expression of E-selectin, Icam-1, or Vcam-1 mRNAs, as compared with untreated EC (Fig. 6A). Inhibition of gene transcription by actinomycin D suppressed the up-regulation of mRNAs encoding E-selectin, Icam-1, and Vcam-1 in response to ferrylHb (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these data suggest that ferrylHb induces the expression of these mRNAs via a mechanism regulated at the transcriptional level, i.e. inhibited by actinomycin D.

FIGURE 6.

FerrylHb induces the transcription of proinflammatory genes. A, confluent HUVEC were exposed (4 h) to Hb, MtHb, ferrylHb (20 μm), or vehicle (Cont) and E-selectin, Icam-1, and Vcam-1 mRNA expression was quantified by qRT-PCR. B, confluent HUVEC were pretreated or not with actinomycin D (5 μg/ml; 30 min) and exposed (4 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm) or vehicle (Cont). E-selectin, Icam-1, and Vcam-1 mRNA expression was quantified by qRT-PCR. Values are normalized to the expression of mRNA encoding the housekeeping gene Hprt and are shown as a mean fold-induction versus control ± S.D. (n = 3), from 1 of 3 experiments. Act.D, actinomycin D. C, C57BL/6 mice were either not treated (NT) or received vehicle (intravenous PBS) or ferrylHb (intravenous; 8 μmol/kg in 200 μl of apyrogenic PBS). E-selectin, Icam-1, and Vcam-1 mRNA expression was quantified in the liver by qRT-PCR. Values are shown as the number of E-selectin, Icam-1, or Vcam-1 per Hprt mRNA molecules ± S.D. (n = 4 per group) in 1 of 2 experiments. p values were calculated using ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. NT, not treated.

We asked whether ferrylHb induces in vivo the expression of adhesion molecules associated with EC activation. When administered into naïve mice (intravenous), ferrylHb induced the expression of mRNA encoding E-selectin, Icam-1, and Vcam-1, as assessed in the liver by qRT-PCR (Fig. 6C). Because expression of some of these adhesion molecules, i.e. E-selectin, is restricted to vascular EC, this observation supports the notion that in a similar manner to what occurs in vitro, ferrylHb can induce in vivo the expression of proinflammatory genes in EC.

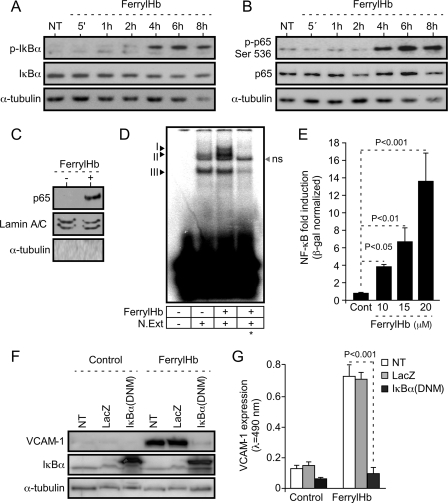

The Proinflammatory Effect of FerrylHb Acts via Activation of the NF-κB Family of Transcription Factors

Most of the proinflammatory genes expressed during EC activation are regulated at the transcriptional level via activation of the NF-κB family of transcription factors (13, 14). In keeping with this notion, ferrylHb led to sustained phosphorylation and partial degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor molecule IκBα, as assessed in EC by Western blot (Fig. 7A). FerrylHb also induced phosphorylation of p65/RelA, i.e. Ser-536 (Fig. 7B), a NF-κB family member critically involved in the regulation of the expression of proinflammatory genes associated with EC activation (14). FerrylHb led to p65/RelA nuclear translocation (Fig. 7C) and NF-κB binding to DNA κB binding motifs (Fig. 7D), as assessed by Western blot and electrophoretic mobility shift assay, respectively. FerrylHb induced by 4–16-fold NF-κB transcriptional activity in EC, as assessed using a synthetic NF-κB-luciferase reporter (Fig. 7E). This effect was dose-dependent in that higher concentrations of ferrylHb led to increased NF-κB activity (Fig. 7E). The proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb was suppressed when EC were transduced with a recombinant adenovirus encoding a dominant negative mutant form of IκBα, as assessed by VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 7, F and G). Taken together, these observations reveal that the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb occurs through a mechanism dependent on the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB.

FIGURE 7.

FerrylHb activates NF-κB in EC. A and B, confluent HUVEC were exposed to ferrylHb (20 μm) for increasing periods of time or untreated (NT), and proteins were detected in whole-cell extracts by Western blot. C, confluent HUVEC were exposed (6 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm) or not (−), and p65/RelA was detected in nuclear extracts by Western blot. Lamin A/C and α-tubulin were used as nuclear and cytoplasmic markers, respectively. Immunoblots are representative of three independent experiments. D, confluent HUVEC were treated as in C, and nuclear NF-κB binding to DNA κB probe was detected by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Arrows I, II, and III indicate specific binding to the DNA κB probe. The asterisk indicates competition (20×) with non-radiolabeled κB DNA probe. ns, not specific. N.Ext, Nuclear extract. E, confluent HUVEC co-transduced with NF-κB-Luc and CMV-LacZ recombinant adenovirus were exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb or not (Cont). Luciferase was normalized to β-galactosidase units and results are shown as the mean fold-induction versus control (not exposed to ferrylHb) ± S.D. (n = 3), from 1 of 3 independent experiments. p values were calculated with ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. F, confluent HUVEC were co-transduced or not (NT) with LacZ or IκBα(DNM) recombinant adenovirus and exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm) or not (Control). Proteins were detected in whole cell lysates by Western blotting. Immunoblots are representative of three independent experiments. G, confluent HUVEC were treated as in F, and VCAM-1 was detected by cellular ELISA. Results are the mean values ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 4 independent experiments. p value was calculated with unpaired Student's t test.

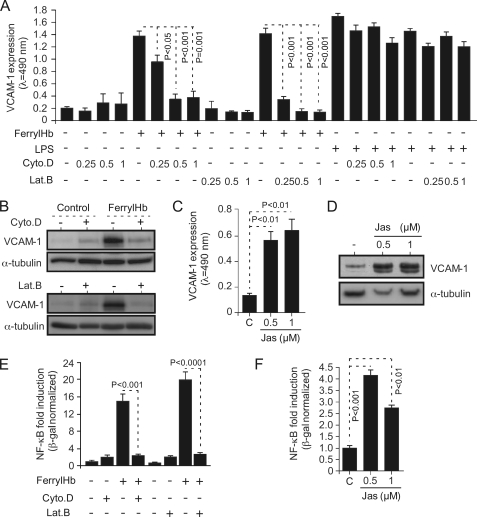

The Proinflammatory Effect of FerrylHb Is Dependent on Actin Polymerization

Given that ferrylHb induces actin polymerization (Fig. 2, A and B), we asked whether this effect is functionally linked to its proinflammatory effect, i.e. induction of adhesion molecule expression (Fig. 3). Pharmacological inhibition of actin polymerization by cytochalasin D (35) suppressed the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb, as assessed by VCAM-1 expression in EC (Fig. 8, A and B). The effect of cytochalasin D was dose-dependent, with higher concentrations reducing further ferrylHb-driven VCAM-1 expression in EC (Fig. 8A). Moreover, the effect of cytochalasin D was specific in that cytochalasin D failed to inhibit the proinflammatory effect of LPS, as assessed by VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 8A). Similar results were obtained using LatB, a compound that alters the actin-monomer subunit interface to prevent its polymerization (36) (Fig. 8, A and B). The effect of LatB was also dose-dependent, with higher concentrations increasing its inhibitory effect of ferrylHb-driven VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 8A). The effect of LatB was specific in that it did not inhibit LPS-driven VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 8A). We assessed whether actin polymerization is sufficient per se to induce the expression of proinflammatory genes associated with EC activation. VCAM-1 expression was induced in EC exposed to jasplakinolide, an actin-stabilizing toxin that polymerizes actin (37) (Fig. 8, C and D).

FIGURE 8.

The proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is dependent on actin polymerization. A, confluent HUVEC were exposed to cytochalasin D (Cyto.D; 0.25–1 μm; 30 min), LatB (0.25–1 μm; 30 min), or vehicle (−) and not further treated (−) or exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm) or LPS (100 ng/ml). VCAM-1 expression was detected by cellular ELISA. B, confluent HUVEC were treated with cytochalasin D (0.5 μm; 30 min; +), latrunculin B (0.5 μm; 30 min; +) or vehicle (−) and not further treated (Control) or exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm). Proteins were detected in whole cell lysates by Western blotting. C and D, confluent HUVEC were exposed (8 h) to jasplakinolide (Jas) or to vehicle (C), and VCAM-1 protein expression was measured by cellular ELISA (C) or by Western blotting (D). E, confluent HUVEC were transduced (48 h) with NF-κB-Luc and LacZ recombinant adenovirus, treated with cytochalasin D (0.5 μm; 30 min; +), latrunculin B (0.5 μm; 30 min; +), or vehicle (−), and then not further treated (−) or exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm). Luciferase was normalized to β-galactosidase units, and values are represented as mean fold-induction versus control non-treated cells ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 3 independent experiments. p values were calculated with the unpaired Student's t test. F, confluent HUVEC were transduced as in E and either not treated, treated (8 h) with jasplakinolide, or vehicle (C), and the rest of the procedure was done as in E. Results in A, C, E, and F are the mean values ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 3 independent experiments. p values were calculated with ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. Immunoblots in B and D are representative of three independent experiments.

Having established that the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is dependent on actin polymerization (Fig. 8, A–D) as well as on NF-κB activation (Fig. 7), we asked whether these two events are functionally linked. Both cytochalasin D and LatB suppressed NF-κB activation by ferrylHb, as assessed in EC transduced with a synthetic NF-κB luciferase reporter (Fig. 8E). This suggests that actin polymerization acts “upstream” of NF-κB in the signaling transduction pathway via which ferrylHb induces the expression of proinflammatory genes in EC. Moreover, actin polymerization by jasplakinolide induced a mild but significant activation of NF-κB in EC, as assessed using a NF-κB luciferase reporter (Fig. 8F). Taken together, these observations reveal that ferrylHb exerts proinflammatory effects in EC via a mechanism dependent on actin polymerization.

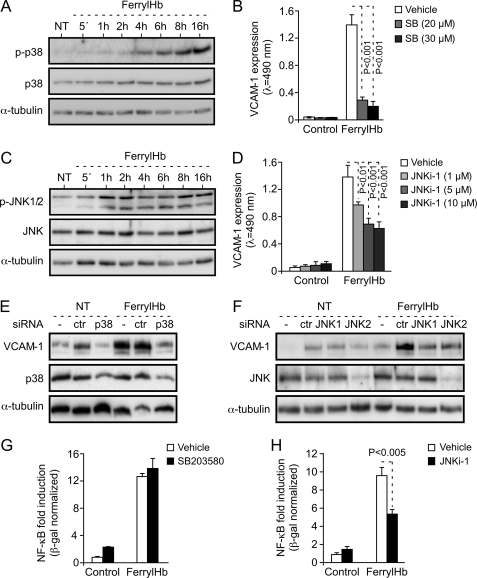

The Proinflammatory Effect of FerrylHb Is Dependent on the Activation of the p38 MAPK and JNK Signaling Transduction Pathways

FerrylHb induced the activation of the p38 MAPK signal transduction pathway in EC, first detected within 2–4 h after ferrylHb exposure and increasing thereafter until 16 h, the last time point analyzed (Fig. 9A). Pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAPK activation by the pyridine imidazole SB203580 suppressed the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb, i.e. ∼90% reduction in VCAM-1 protein expression (Fig. 9B). FerrylHb also induced the activation of the JNK signal transduction pathway in EC, first detected 1 h after ferrylHb exposure and increasing thereafter until 16 h, the last time point analyzed (Fig. 9C). Pharmacological inhibition of JNK activation by l-stereoisomer (JNKi-1) reduced by ∼50% the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb, as assessed by VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 9D).

FIGURE 9.

The proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is dependent on the activation of the p38 MAPK and JNK. A, confluent HUVEC were either untreated (NT) or exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm) for increasing periods of time, and proteins were detected in whole cell lysates by Western blotting. B, confluent HUVEC were exposed to the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 or to vehicle and not further treated (Control) or exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm). VCAM-1 was detected by cellular ELISA. C, confluent HUVEC were treated as in A, and proteins were detected in cell lysates by Western blot. D, confluent HUVEC were pretreated with JNKi-1 or with vehicle, and the rest of the procedure was done as in B. Results in B and D are the mean values ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 3 independent experiments. p values were calculated with ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. E, confluent HUVEC were not transfected (−) or transfected with control (ctr) or anti-p38 MAPK siRNA and exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm) or to vehicle (NT). Proteins were detected as in A. Control cells (−) received transfection reagent Oligofectamine. F, confluent HUVEC were not transfected (−) or transfected with control (ctr) or anti-JNK1 or -JNK2 siRNA. The rest of the procedure was the same as in E. Immunoblots in A, C, E, and F are representative of three independent experiments. G and H, confluent HUVEC were transduced with NF-κB-Luc and LacZ recombinant adenovirus, treated with SB203580 (G), JNKi-1 (H), or vehicle and not further treated (Control) or exposed (8 h) to ferrylHb (20 μm). Luciferase was normalized to β-galactosidase units and shown as the mean fold-induction versus control ± S.D. (n = 3) from 1 of 3 independent experiments. p values in G and H were calculated with the unpaired Student's t test.

The involvement of the p38 and JNK signal transduction pathways in the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb was confirmed by targeting specifically these kinases using siRNA. Inhibition of p38 MAPK expression suppressed the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb, i.e. >95% reduction in VCAM-1 protein expression, as compared with control siRNA (Fig. 9E). Targeting JNK1 and JNK2 expression with siRNAs also inhibited the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb, i.e. ∼40% decrease in VCAM-1 protein expression, as compared with control siRNA (Fig. 9F). These observations reveal that activation of p38 MAPK and JNK is required to sustain the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb in EC. It should be noted that the antibody used to detect JNK1/2 in HUVEC appears to detect predominantly the JNK2 isoform (Fig. 9, C and F). However, an anti-JNK1 siRNA, which does not suppress JNK2 expression (Fig. 9F), appears to be as efficient as an anti-JNK2 siRNA in inhibiting the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb in EC, thus suggesting that JNK1 and JNK2 are both required to sustain the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb. Of notice as well, the transfection reagents, i.e. Oligofectamine and siRNAs, induced per se the expression of VCAM-1 in EC (Fig. 9, E and F). This effect was not related to siRNA specificity, it was observed using Oligofectamine alone (Fig. 9E) or Oligofectamine plus nonspecific siRNA (Fig. 9, E and F).

We then asked whether p38 MAPK or JNK activation is required to support NF-κB activation and/or the expression of proinflammatory genes in response to ferrylHb. Pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAPK by SB203580 failed to inhibit NF-κB activation in EC (Fig. 9G) under the same experimental conditions leading to VCAM-1 inhibition (Fig. 9B). This suggests that p38 MAPK and NF-κB activation act independently of each other to promote the transcription/expression of proinflammatory genes in response to ferrylHb. Pharmacological inhibition of JNK by JNKi-1 inhibited by 40% the activation of NF-κB by ferrylHb (Fig. 9H). This suggests that ferrylHb induces the activation of NF-κB via a mechanism involving the activation of JNK.

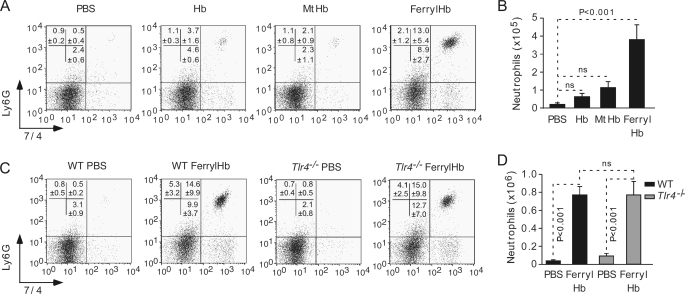

FerrylHb Acts as a Proinflammatory Agonist in Vivo

We asked whether ferrylHb exerts proinflammatory effects in vivo such as when administered into the peritoneal cavity of naïve C57BL/6 mice, a well established experimental model of “sterile” inflammation (38, 39). FerrylHb induced a robust inflammatory response, revealed by an average 19-fold increase in the number of peritoneal Ly6G+7/4+ PMN cells, as compared with vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 10, A and B). This effect was not observed using equimolar amounts of Hb or MtHb (Fig. 10, A and B), which is in keeping with the observation that Hb or MtHb do not exert proinflammatory effects in EC in vitro (Fig. 3). To test whether the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is because of LPS, i.e. endotoxin, we assessed whether this effect is lost in mice lacking the LPS receptor Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), i.e. C57BL/6.Tlr4−/− mice (40). FerrylHb led to similar levels of PMN cell influx into the peritoneal cavity of Tlr4−/− versus wild type Tlr4+/+ mice (Fig. 10, C and D), which discards the possibility that the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is because of a putative endotoxin contamination and, thus, supports the notion that ferrylHb is a bona fide proinflammatory agonist.

FIGURE 10.

FerrylHb is proinflammatory in vivo. Naïve C57BL/6 mice received a bolus administration (intraperitoneal) of Hb, MtHb, or ferrylHb or PBS. A, representative dot blots of peritoneal Ly-6G+ 7/4+ PMN cells 16 h after stimulus. B, mean number of Ly-6G+ 7/4+ PMN cells ± S.E. (PBS, n = 11; Hb, n = 5; MtHb, n = 9; ferrylHb, n = 15) plotted from three independent experiments. ns, not significant. C, representative dot blots of peritoneal Ly-6G+ 7/4+ PMN cells in C57BL/6.Tlr4+/+ versus C57BL/6.Tlr4−/− mice 16 h after ferrylHb administration. D, mean number of Ly-6G+ 7/4+ PMN cells ± S.E (Tlr4+/+/PBS, n = 11; Tlr4+/+/ferrylHb, n = 12; Tlr4−/−/PBS and Tlr4−/−/ferrylHb, n = 9), plotted from three independent experiments. p values were calculated with ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test.

DISCUSSION

Several pathological conditions are associated with varying levels of hemolysis and, therefore, with more or less extensive accumulation of cell-free Hb in plasma (for review, see Ref. 2). Under homeostasis, the deleterious effects of cell-free Hb are controlled by haptoglobin (41), a plasma protein that binds cell-free Hb with high affinity (42), promoting its recognition by the CD163 receptor expressed by hemophagocytic Mø (43) (for review, see Ref. 44). Hb degradation in Mø induces the expression of heme oxygenase-1 (43), which catabolizes the heme prosthetic groups of Hb into CO, iron, and biliverdin (45) and then converted, by biliverdin reductase, into the antioxidant bilirubin (46). The cytoprotective and antioxidant effects associated with heme catabolism by heme oxygenase-1 (for review, see Ref. 47, 48) are key in maintaining the homeostatic control of cell-free Hb, as revealed in Hmox1-deficient mice (49) as well as in the one case of HMOX1 deficiency reported in humans (50). This notion is further supported by the observation that the main clinical feature of human HMOX1 deficiency is severe chronic intravascular hemolysis associated with oxidation of cell-free Hb (51) and the development of micro- and macroangiopathies (52).

Under inflammatory conditions, cell-free Hb can react with reactive oxygen species, such as H2O2 produced by activated PMN cells or Mø (3, 53). This reaction can generate, in addition to MtHb, an unstable oxidized form of Hb, i.e. ferrylHb (4–6), detected in humans under physiologic (54) and pathophysiologic conditions (55–57). Contrary to other forms of Hb, ferrylHb undergoes intermolecular cross-linking of its globin chains via oxidation of tyrosine residues that can form dityrosine covalent bonds (Fig. 1). The resulting ferrylHb multimers have reduced affinity toward haptoglobin (9, 28), bypassing the homeostatic control of cell-free Hb exerted by the haptoglobin-CD163-heme oxygenase-1 scavenging pathway.

We hypothesized that the oxidized forms of Hb might exert proinflammatory effects in vascular EC. As demonstrated hereby, ferrylHb but not MtHb can exert proinflammatory effects in EC that are not associated with its previously established cytotoxic effects in EC (11) (Fig. 2, C and D).

MtHb has been suggested to exert proinflammatory effects in EC (58). However, our data suggests that this proinflammatory effect is attributable to a contamination of commercially available MtHb by endotoxin (58), a common artifact in these type of studies (59). We found that commercially available MtHb (58) can contain up to 40 ng of endotoxin/mg of protein (data not shown), which is more than 2000 times the amount of endotoxin in the Hb preparations used in our study. Moreover, the proinflammatory effect of MtHb (58) is ablated using endotoxin-free MtHb (Fig. 3) and cells lacking the endotoxin receptor, i.e. TLR4 also fail to respond to commercially available MtHb (supplemental Fig. 2). Together, these observations argue that the previously proinflammatory effects of MtHb (58) is most probably because of an endotoxin contamination rather than to MtHb itself.

When exposed in vitro to ferrylHb (5–20 μm), EC rearrange their actin cytoskeleton, as revealed by the formation of F-actin stress fibers/bundles (Fig. 2, A and B). This is associated with the formation of intercellular gaps disrupting the integrity of the EC monolayer (Fig. 2, A and B), a highly deleterious event that promotes unfettered extravascular leakage and exposes the pro-coagulant sub-endothelial matrix to the clotting cascade (60).

When exposed in vitro to ferrylHb, EC up-regulate the rate of transcription of several proinflammatory genes, i.e. E-selectin, Icam-1, and Vcam-1 (Figs. 3 and 6, A and B) through activation of the NF-κB family of transcription factors (Fig. 7) via a mechanism that is not totally clear. FerrylHb causes a modest and delayed (i.e. 4–8 h after stimulation) phosphorylation of IκBα at Ser-32/36 (Fig. 7A), leading to a similarly modest and delayed degradation of IκBα (Fig. 7A) that does not seem to account for the observed induction of NF-κB nuclear translocation (Fig. 7, C and D) and activity (Fig. 7E). One possible explanation for this would be that ferrylHb triggers IκBα phosphorylation at Tyr-42, leading to NF-κB activation without the need for IκBα degradation (61). However, ferrylHb leads to a very modest IκBα Tyr-42 phosphorylation in EC (supplemental Fig. 3), which discards this possibility. An alternative explanation might be that IκBα phosphorylation in response to ferrylHb would occur at a cluster of C-terminal phosphoacceptors, leading to robust activation of NF-κB despite the modest degradation of IκBα, as observed in response to UV radiation (62). This atypical pathway of NF-κB activation is mediated by the stress-responsive casein kinase II (α and β) (62). Whether ferrylHb induces the activation of NF-κB in EC through the activation of casein kinase II remains to be tested.

In addition, from NF-κB, ferrylHb activates other signal transduction pathways that are required to sustain its proinflammatory effect (Fig. 9). This is the case for p38 MAPK, which promotes the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb (Fig. 9, A, B, and E) without modulating NF-κB activity (Fig. 9G) via a mechanism that remains to be established. Activation of JNK by ferrylHb is part of another signal transduction pathway involved in the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb (Fig. 9, C, D, and F). Contrary to p38 MAPK, however, JNK activation modulates NF-κB activity (Fig. 9H) via a mechanism that remains to be established.

Inhibition of actin polymerization by cytochalasin D significantly decreases (∼40%) p38 MAPK activation in response to ferrylHb (supplemental Fig. 4A), suggesting that actin polymerization acts upstream of p38 MAPK in the signal transduction pathway induced by ferrylHb and leading to the expression of adhesion molecules in EC. On the other hand, cytochalasin D enhanced JNK activation in response to ferrylHb (supplemental Fig. 4B), suggesting that actin polymerization in response to ferrylHb has opposite effects on the p38 MAPK and JNK signal transduction pathways, activating p38 MAPK while inhibiting JNK activation. The mechanisms underlying these effects remain to be established.

The proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb can be dissociated from its pro-oxidant activity (supplemental Fig. 1) and as such is refractory to antioxidants such as catalase (Fig. 5D), N-acetylcysteine or butylated hydroxyanisole (tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole) (supplemental Fig. 1, C–E). Furthermore, this proinflammatory effect is not attributable either to heme release from ferrylHb (Fig. 5C), to generation of free radicals, i.e. H2O2 (data not shown), or putative contaminants such as endotoxin (Figs. 5B and 10, C and D) or H2O2 (Fig. 5E).

Activation of NF-κB and expression of proinflammatory genes in response to ferrylHb is dependent on actin polymerization (Fig. 8). This would suggest that ferrylHb might require phagocytosis, a process regulated through actin polymerization, to exert its proinflammatory effect in EC. This notion is consistent with the observation that other endogenous proinflammatory agonists such as uric acid crystals require phagocytosis to act in a proinflammatory manner (38). Alternatively, however, ferrylHb might exert proinflammatory effects in EC through activation of a signal transduction pathway involving actin polymerization (Fig. 8, E and F), as is the case for thrombin, an endogenous proinflammatory agonist that induces the expression of adhesion molecules in EC through the activation of NF-κB by a signal transduction pathway involving actin polymerization (3, 53). These two possibilities are not mutually exclusive.

Given that ferrous Hb and MtHb do not mimic the proinflammatory effects of ferrylHb (Figs. 2A, 3, A and B, 6A, and 10, A and B), it is likely that ferrylHb undergoes specific “conformational” modifications to become proinflammatory (63). This notion is consistent with the observation that, contrary to Hb or MtHb, ferrylHb forms multimeric hydrophobic aggregates (Figs. 1, A and B and 2A). Hydrophobicity has been proposed to act as a common molecular denominator recognized by innate germ line-encoded pattern recognition receptors (59). Engagement of pattern recognition receptors elicits inflammatory responses through activation of signal transduction pathways that include those activated by ferrylHb in EC, e.g. NF-κB, JNK, and p38 MAPK (64).

These observations suggest that, in a similar manner to other endogenous proinflammatory agonists, e.g. uric acid (35, 36, 52) or peptide amyloid-β (65), ferrylHb might act as an endogenous proinflammatory ligand recognized by innate pattern recognition receptors. One possibility would be that ferrylHb is recognized by NOD-like receptors that form multimeric cytoplasmic complexes, i.e. inflammasomes, linking recognition of proinflammatory ligands to proteolytic activation of proinflammatory cytokines, e.g. IL-1 (for review, see Ref. 66). This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb is exerted in vivo via a mechanism involving the IL-1/IL-1R signal transduction pathway (data not shown). Contrary to other proinflammatory agonists, however, ferrylHb does not seem to elicit proinflammatory effects in innate immune cells such as Mø (Fig. 4) or dendritic cells (data not shown), as tested in vitro. This suggests that ferrylHb targets specifically EC via a mechanism that has not been established but that could rely on the expression of a specific receptor recognizing ferrylHb. The observation that ferrylHb, but not ferrous Hb or MtHb, can elicit inflammatory responses in mice (Figs. 6C and 10, A and B) supports the notion that ferrylHb might act as an endogenous proinflammatory agonist in vivo.

Although we have not demonstrated unequivocally that the proinflammatory effect of ferrylHb in vivo acts via the same mechanisms that are operative in vitro, this is likely to be the case, as ferrylHb can induce in vivo the expression of adhesion molecules associated with EC activation (Fig. 6C), which are required to sustain recruitment of PMN cells (67) as triggered by ferrylHb in vivo.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that ferrylHb acts as a proinflammatory agonist in EC, suggesting that oxidation of cell-free Hb and in particular production of ferrylHb might be an important component in the pathogenesis of inflammatory conditions associated with hemolysis and EC activation such as is the case for thrombotic microangiopathies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nuno Moreno and Barbara Fekete (Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência) for expert support with cell imaging, Josef Anrather (Dept. of Neurology and Neuroscience, Weill Cornell Medical College), Fritz H. Bach (Harvard Medical School), and Florence Janody (Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência) for critically reviewing the manuscript, and members of the “Inflammation Laboratory” (Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência) for input and support.

This work was supported by Grants POCTI/BIA-BCM/56829/2004, POCTI/SAU-MNO/56066/2004, and POCTI/SAU/56066/2007 from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal, European Commission's Sixth Framework Program, XENOME (LSHB-CT-2006-037377), and the GEMI fund (Linde Healthcare) (to M. P. S.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–4.

- MtHb

- methemoglobin

- EC

- endothelial cells

- Hb

- hemoglobin

- ferrylHb

- oxidized Hb

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein EC

- ICAM-1

- intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IκBα

- NF-κB inhibitor

- JNK

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Mϕ

- monocyte/macrophages

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- PMN

- polymorphonuclear

- VCAM-1

- vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- Hprt

- hypoxanthine-guanine-phosphoribosyltransferase

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- FCS

- fetal calf serum

- HPLC

- high performance liquid chromatography

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- LatB

- latrunculin B

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- IL

- interleukin

- DNM

- dominant negative mutant

- TLR4

- Toll-like receptor 4.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schechter A. N. (2008) Blood 112, 3927–3938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rother R. P., Bell L., Hillmen P., Gladwin M. T. (2005) JAMA 293, 1653–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balla J., Jacob H. S., Balla G., Nath K., Eaton J. W., Vercellotti G. M. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 9285–9289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winterbourn C. (1985) Reactions of Superoxide with Hemoglobin, CRC, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giulivi C., Davies K. J. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 231, 490–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giulivi C., Cadenas E. (1998) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 24, 269–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeder B. J., Grey M., Silaghi-Dumitrescu R. L., Svistunenko D. A., Bülow L., Cooper C. E., Wilson M. T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30780–30787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maples K. R., Kennedy C. H., Jordan S. J., Mason R. P. (1990) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 277, 402–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuoka N., Sugiyama H., Ishibashi N., Wang D. H., Masuoka T., Kodama H., Nakano T. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21728–21734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giulivi C., Davies K. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24129–24136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman D. W., Breyer R. J., 3rd, Yeh D., Brockner-Ryan B. A., Alayash A. I. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 275, H1046–H1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pober J. S., Sessa W. C. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 803–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wrighton C. J., Hofer-Warbinek R., Moll T., Eytner R., Bach F. H., de Martin R. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 1013–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soares M. P., Muniappan A., Kaczmarek E., Koziak K., Wrighton C. J., Steinhäuslin F., Ferran C., Winkler H., Bach F. H., Anrather J. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 4572–4582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins N. D. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 49–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baeuerle P. A., Baltimore D. (1988) Science 242, 540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown K., Gerstberger S., Carlson L., Franzoso G., Siebenlist U. (1995) Science 267, 1485–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Z., Hagler J., Palombella V. J., Melandri F., Scherer D., Ballard D., Maniatis T. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 1586–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henkel T., Machleidt T., Alkalay I., Krönke M., Ben-Neriah Y., Baeuerle P. A. (1993) Nature 365, 182–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traenckner E. B., Wilk S., Baeuerle P. A. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 5433–5441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anrather J., Racchumi G., Iadecola C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 244–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L. F., Greene W. C. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brouard S., Otterbein L. E., Anrather J., Tobiasch E., Bach F. H., Choi A. M., Soares M. P. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 192, 1015–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huyer G., Liu S., Kelly J., Moffat J., Payette P., Kennedy B., Tsaprailis G., Gresser M. J., Ramachandran C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 843–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soares M. P., Seldon M. P., Gregoire I. P., Vassilevskaia T., Berberat P. O., Yu J., Tsui T. Y., Bach F. H. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 3553–3563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seldon M. P., Silva G., Pejanovic N., Larsen R., Gregoire I. P., Filipe J., Anrather J., Soares M. P. (2007) J. Immunol. 179, 7840–7851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva G., Cunha A., Grégoire I. P., Seldon M. P., Soares M. P. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 1894–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallelian F., Pimenova T., Pereira C. P., Abraham B., Mikolajczyk M. G., Schoedon G., Zenobi R., Alayash A. I., Buehler P. W., Schaer D. J. (2008) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 1150–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colucci M., Balconi G., Lorenzet R., Pietra A., Locati D., Donati M. B., Semeraro N. (1983) J. Clin. Invest. 71, 1893–1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth R. I. (1994) Blood 83, 2860–2865 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su D., Roth R. I., Yoshida M., Levin J. (1997) Infect. Immun. 65, 1258–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaneko M., Hayashi J., Saito I., Miyasaka N. (1996) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 16, 1047–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Appelmelk B. J., Su D., Verweij-van Vught A. M., Thijs B. G., MacLaren D. M. (1992) Anal. Biochem. 207, 311–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagener F. A., Eggert A., Boerman O. C., Oyen W. J., Verhofstad A., Abraham N. G., Adema G., van Kooyk Y., de Witte T., Figdor C. G. (2001) Blood 98, 1802–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper J. A. (1987) J. Cell Biol. 105, 1473–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morton W. M., Ayscough K. R., McLaughlin P. J. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 376–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bubb M. R., Senderowicz A. M., Sausville E. A., Duncan K. L., Korn E. D. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14869–14871 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinon F., Pétrilli V., Mayor A., Tardivel A., Tschopp J. (2006) Nature 440, 237–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi Y., Evans J. E., Rock K. L. (2003) Nature 425, 516–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoshino K., Takeuchi O., Kawai T., Sanjo H., Ogawa T., Takeda Y., Takeda K., Akira S. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 3749–3752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owen J. A., Silberman H. J., Got C. (1958) Nature 182, 1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melamed-Frank M., Lache O., Enav B. I., Szafranek T., Levy N. S., Ricklis R. M., Levy A. P. (2001) Blood 98, 3693–3698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kristiansen M., Graversen J. H., Jacobsen C., Sonne O., Hoffman H. J., Law S. K., Moestrup S. K. (2001) Nature 409, 198–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferreira A., Balla J., Jeney V., Balla G., Soares M. P. (2008) J. Mol. Med. 86, 1097–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tenhunen R., Marver H. S., Schmid R. (1968) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 61, 748–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stocker R., Yamamoto Y., McDonagh A. F., Glazer A. N., Ames B. N. (1987) Science 235, 1043–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soares M. P., Bach F. H. (2009) Trends Mol. Med. 15, 50–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otterbein L. E., Soares M. P., Yamashita K., Bach F. H. (2003) Trends Immunol. 24, 449–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poss K. D., Tonegawa S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10919–10924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yachie A., Niida Y., Wada T., Igarashi N., Kaneda H., Toma T., Ohta K., Kasahara Y., Koizumi S. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 129–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeney V., Balla J., Yachie A., Varga Z., Vercellotti G. M., Eaton J. W., Balla G. (2002) Blood 100, 879–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawashima A., Oda Y., Yachie A., Koizumi S., Nakanishi I. (2002) Hum. Pathol. 33, 125–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiss S. J. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 2947–2953 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Svistunenko D. A., Patel R. P., Voloshchenko S. V., Wilson M. T. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7114–7121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vollaard N. B., Reeder B. J., Shearman J. P., Menu P., Wilson M. T., Cooper C. E. (2005) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 39, 1216–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reeder B. J., Sharpe M. A., Kay A. D., Kerr M., Moore K., Wilson M. T. (2002) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30, 745–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ziouzenkova O., Asatryan L., Akmal M., Tetta C., Wratten M. L., Loseto-Wich G., Jürgens G., Heinecke J., Sevanian A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18916–18924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu X., Spolarics Z. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 285, C1036–C1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seong S. Y., Matzinger P. (2004) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 469–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu K. K., Thiagarajan P. (1996) Annu. Rev. Med. 47, 315–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Imbert V., Rupec R. A., Livolsi A., Pahl H. L., Traenckner E. B., Mueller-Dieckmann C., Farahifar D., Rossi B., Auberger P., Baeuerle P. A., Peyron J. F. (1996) Cell 86, 787–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kato T., Jr., Delhase M., Hoffmann A., Karin M. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jia Y., Buehler P. W., Boykins R. A., Venable R. M., Alayash A. I. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4894–4907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Medzhitov R., Preston-Hurlburt P., Janeway C. A., Jr. (1997) Nature 388, 394–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Halle A., Hornung V., Petzold G. C., Stewart C. R., Monks B. G., Reinheckel T., Fitzgerald K. A., Latz E., Moore K. J., Golenbock D. T. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 857–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martinon F., Mayor A., Tschopp J. (2009) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 229–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bullard D. C., Qin L., Lorenzo I., Quinlin W. M., Doyle N. A., Bosse R., Vestweber D., Doerschuk C. M., Beaudet A. L. (1995) J. Clin. Invest. 95, 1782–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.