Abstract

Sustained (noninactivating) outward-rectifying K+ channel currents have been identified in a variety of plant cell types and species. Here, in Arabidopsis thaliana guard cells, in addition to these sustained K+ currents, an inactivating outward-rectifying K+ current was characterized (plant A-type current: IAP). IAP activated rapidly with a time constant of 165 ms and inactivated slowly with a time constant of 7.2 sec at +40 mV. IAP was enhanced by increasing the duration (from 0 to 20 sec) and degree (from +20 to −100 mV) of prepulse hyperpolarization. Ionic substitution and relaxation (tail) current recordings showed that outward IAP was mainly carried by K+ ions. In contrast to the sustained outward-rectifying K+ currents, cytosolic alkaline pH was found to inhibit IAP and extracellular K+ was required for IAP activity. Furthermore, increasing cytosolic free Ca2+ in the physiological range strongly inhibited IAP activity with a half inhibitory concentration of ≈ 94 nM. We present a detailed characterization of an inactivating K+ current in a higher plant cell. Regulation of IAP by diverse factors including membrane potential, cytosolic Ca2+ and pH, and extracellular K+ and Ca2+ implies that the inactivating IAP described here may have important functions during transient depolarizations found in guard cells, and in integrated signal transduction processes during stomatal movements.

At least two general classes of voltage-dependent K+ channels have been characterized in the plasma membrane of plant cells: hyperpolarization-activated inward-rectifying K+ channels (K+in), which mediate K+ influx (for review see refs. 1 and 2), and depolarization-activated outward-rectifying K+ channels (K+out), which mediate K+ efflux. K+out currents have been identified in a variety of cell types and plant species, such as guard cells of Vicia faba, maize, tobacco, and Arabidopsis (3–7); trap-lobe cells of Dionaea muscipula (8); Samanea and Mimosa pulvinar motor cells (9, 10); mesophyll cells of Arabidopsis and tobacco (11, 12), and root cells of various species (13–15). The most common property of these plant K+out currents is time- and voltage-dependent activation and lack of inactivation, with currents remaining stable for many minutes during continuous depolarization (16). These sustained K+out currents have been proposed to function as important pathways for prolonged K+ efflux during, for example, stomatal closing (3), leaf movements (9), and repolarization processes after depolarizations (for review see ref. 17).

Interestingly, an outward-rectifying K+ channel (KCO1) recently was cloned from Arabidopsis, which is activated by cytosolic Ca2+ when expressed in insect cells (18). The primary structure of KCO1 contains two pore-forming domains within one subunit, showing structural similarities to two pore-domain K+ channels isolated recently in yeast, Drosophila, and human (19–21). In maize suspension cells and Mimosa pulvinar cells K+out have been demonstrated to be activated by cytosolic Ca2+ (10, 22).

Depolarization-activated K+ channels have been found in many types of animal cells. These channels have diverse functions in these cell types, such as controlling neuronal excitability and hormone release (23). In animal cells, subsequent to channel activation by depolarization there is a process of channel inactivation with time courses ranging from ms to sec (A-type K+ channel; refs. 23–26). Inactivation is brought about by the channel entering in nonconducting (inactivated) states that are distinct from the closed states (23, 27). One prominent difference in the physiological properties of these K+ channels lies in their inactivation, which can be extremely diverse with respect to time course and can occur by multiple mechanisms (23). Differences in inactivation properties in many cases have a strong influence on the physiological response of the expressing cells (e.g., refs. 28 and 29).

In plant cells, K+ channels showing inactivation as described for A-type channels in animal cells have not been characterized in detail, although a transient outward-rectifying current component recently was observed in some tobacco guard cells, in addition to the sustained K+out currents (5). In the present study, we describe the detailed characterization of an outward-rectifying K+ current with inactivation and unexpected regulation mechanisms in Arabidopsis guard cells, which may have important functions in stomatal movements, such as in repolarization processes after transient depolarizations reported in guard cells (30, 31) and in short-term K+ efflux during regulation of stomatal apertures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Guard Cell Isolation.

A. thaliana plants were grown in a controlled environment growth chamber for 4–6 weeks, and guard cell protoplasts were isolated as described previously (7). In brief, two Arabidopsis leaves were blended. The epidermal strips were collected on a 292-μm mesh and then incubated in 10 ml of medium containing 1.3% cellulase R10 and 0.7% macerozyme R10 (Yakult Honsha, Tokyo), 0.1 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 500 mM d-mannitol, 0.5% BSA, 0.1% kanamycin sulfate, and 10 mM ascorbic acid-Tris (pH 5.5) for 16 hr at 22 ± 2°C on an orbital shaker. Isolated guard cell protoplasts were then collected, washed twice, and stored on ice for use.

Data Acquisition and Analysis.

Patch clamp electrodes were prepared from soft glass capillaries (Kimax 51, Kimble, Toledo, OH), and pulled on a multistage puller (model P-87, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Conventional whole-cell voltage-clamp was performed (32). Giga-ohm seals between electrode and plasma membrane were obtained by suction and usually appeared within 2–3 min. Cells were pulled up to the bath solution surface to reduce stray capacitance. Whole-cell configurations were established by applying increased continuous suction to the interior of the pipette. Guard cell protoplasts were voltage-clamped by using Axopatch 200 and Axopatch 1D amplifiers (Axon Instruments) (7). Data were analyzed by using axograph (version 3.5, Axon Instruments). Statistical analyses were performed by using excel (version 5.0; Microsoft). Data are the mean ± SEM.

Solutions.

The standard pipette solution contained 30 mM KCl, 70 mM K-glutamate, 2 mM MgCl2, 6.7 mM EGTA, 3.35 mM CaCl2, 5 mM Mg-ATP, and 10 mM Hepes-Tris, pH 7.1. The standard bath solution contained 30 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Mes-Tris, pH 5.6. Total CaCl2 concentrations in pipette solutions were changed to give indicated cytosolic free Ca2+ with 6.7 mM EGTA in all solutions. Free Ca2+ concentrations were calculated after accounting for ionic strength, temperature, and other parameters with Chelator software (Theo J.M. Schoenmakers, University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands). For pH experiments 6.7 mM EGTA and no CaCl2 were added to pipette solutions. For ion substitution experiments, CsCl and K-gluconate were used. Other changes of components in solutions are described in detail in the text and figure legends. Osmolalities of all solutions were adjusted to 485 mmol⋅kg−1 for bath solutions and 500 mmol⋅kg−1 for pipette solutions by addition of d-sorbitol. Ionic activities and liquid junction potentials were measured and corrected (33).

RESULTS

In Arabidopsis guard cell protoplasts, when the membrane potential was held at −40 mV and then pulsed to positive potentials, small outward whole-cell currents were observed (Fig. 1A). At the beginning of whole-cell recordings (before “rundown”) we found large noninactivating K+out currents in Arabidopsis guard cells (data not shown) that were analogous to recently reported K+out currents (6). These noninactivating K+out currents in V. faba guard cells have been reported to also show rundown (3). Because of this rundown of K+out currents, we were able to discern an additional type of outward current in the present study.

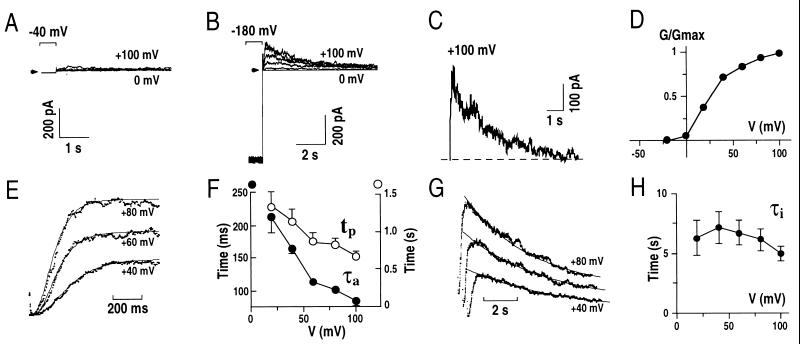

Figure 1.

Hyperpolarization before subsequent depolarization gives rise to transient outward currents in Arabidopsis guard cells. (A) Whole-cell outward currents recorded at positive potentials after a holding potential of −40 mV. (B) Whole-cell outward currents recorded in the same guard cell shown in A after a holding potential of −180 mV. Results similar to those in A and B were found in >100 guard cells. Membrane potentials were stepped from −180 mV to potentials ranging from +100 mV to 0 mV in −20 mV increments with an interval time between pulses of 30 sec in A and B. (C) Hyperpolarization recovered currents calculated by subtraction of current recorded in A from that in B at +100 mV. (D) Normalized transient outward peak conductance (G/Gmax) from experiments performed as in B plotted as a function of the applied membrane potentials. (E) Time course analysis of the transient outward current activation (see text). (F) Times to reach peak currents (tp) and activation time constants (τa) of transient outward currents plotted as a function of the applied membrane potentials. (G) Single exponential decay functions fitted to the inactivation of the transient outward currents. (H) Time constants of the decay (inactivation; τi) of transient outward currents plotted against the applied membrane potentials. The standard pipette solution and a bath solution with 30 mM KCl, 40 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2 were used in A–D (see Materials and Methods). Pipette solutions with nominally zero CaCl2 and a bath solution with 1 mM CaCl2 were used in E–H (see Materials and Methods). Arrows and dashed line show zero current levels.

Enhancement of a Transient Outward Current by Prehyperpolarization.

Because the resting potential in guard cells is negative of −100 mV (30, 31), in subsequent experiments the membrane potential was clamped to more hyperpolarized potentials before depolarizing voltage pulses. When the membrane potential was initially held at −180 mV, depolarizations caused transient outward currents (Fig. 1B). An example of difference currents between Fig. 1 A and B at +100 mV clearly shows that prehyperpolarization to −180 mV enhanced a transient outward current (Fig. 1C). The currents were activated at depolarizing potentials, and subsequently showed a decline during prolonged depolarization. As described later, this decline in currents corresponds to inactivation similar to transient voltage-dependent outward-rectifying K+ currents in animal cells (A-type current, IA; refs. 24–26). We therefore named the transient outward currents IAP (IA in planta).

The peak conductance-voltage relationship of IAP showed that the currents were activated at membrane potentials positive of ≈−20 mV under the imposed conditions (Fig. 1D). The time- and voltage dependence of activation and inactivation of IAP were analyzed. A sigmoidal rise of IAP was resolved after activation (Fig. 1E). The activation time course of currents at membrane potentials could be described by a simple equation:

|

where IL is an instantaneous current component; I∝ is the maximum current after activation, τa is the activation time constant, and P is modeled as the number of gating particles. The currents were well fitted by the equation described above when P = 4 (n = 5 cells). τa and the time for the currents to reach I∝(tp) at +40 mV were 165 ± 7 ms and 1.15 ± 0.16 sec, respectively (Fig. 1F; n = 5). τa and tp showed a voltage dependence, with increased depolarization resulting in more rapid activation. A single exponential decay function could be fitted to the inactivation of IAP (Fig. 1G). Inactivation times of IAP were significantly longer (τi = 7.16 ± 1.37 sec at +40 mV) than activation times and did not show a strong voltage-dependence (Fig. 1H; n = 5).

IAP Is Carried Mainly by K+.

Experiments were performed to test which ions carried IAP by ion substitution and reversal potential determination. Cytosolic ion substitution of K+ for Cs+, which is largely impermeable to most plant K+ channels (16, 34), completely abolished IAP (Fig. 2A). Hyperpolarization-activated K+in currents activated at potentials ranging from −120 to −180 mV were not abolished as expected for cytosolic K+ substitution by Cs+. Note that the lack of outward tail currents for K+in currents at depolarizing potentials (Fig. 2A) is consistent with strong unidirectional Cs+ block of K+in channels reported previously in V. faba guard cells and mesophyll cells of Avena sativa (16, 34). The lack of IAP with Cs+ in the cytosol suggested that IAP may be carried by K+ ions.

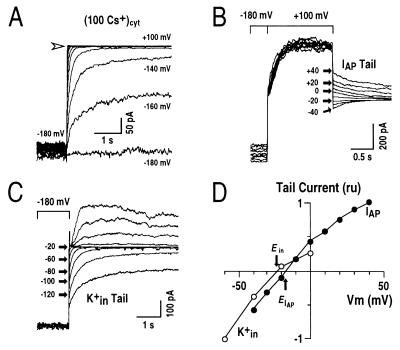

Figure 2.

Transient outward currents are carried mainly by K+. (A) Whole-cell current recordings under conditions with 100 mM Cs+ in the pipette solution. The voltage protocol was similar to that given in Fig. 1B (note large K+in currents at potentials negative of −100 mV). Arrow shows zero current level. (B) Tail current recordings of the transient outward currents. From a holding potential of −180 mV, transient outward currents were activated by a voltage step to +100 mV. Tail currents of the transient outward currents were recorded at the indicated membrane potentials (IAP Tail). (C) Tail currents of K+in currents recorded in the same cell as in B. After a prepulse potential of −180 mV, where K+in currents were activated, tail currents were recorded at the indicated membrane potentials ranging from −140 mV to +80 mV with +20 mV increments (K+in Tail). At increasingly depolarized tail potentials, the decay times of K+in current deactivation became shorter and therefore could be clearly distinguished from the transient outward currents. (D) Tail currents from recordings in B and C were plotted as a function of applied membrane potentials. ru, relative units. IAP tail currents and K+in tail currents were normalized by the currents at +40 mV and −60 mV, respectively. Pipette solutions with zero [Ca2+]i and the standard bath solution were used.

To further test this hypothesis, reversal potentials of these currents were determined by measuring tail currents. Fig. 2B shows typical tail currents recorded for IAP. From the holding potential of −180 mV, the membrane potential was stepped to +100 mV and IAP was activated. Before the currents were inactivated, the membrane potential was stepped back to more negative values. This protocol allowed the deactivation of IAP to be monitored. Fig. 2C shows typical tail currents recorded for K+in from the same cell. Tail current amplitudes of both IAP and K+in currents were quantitatively analyzed and plotted against corresponding membrane potentials (Fig. 2D). The reversal potentials for IAP and K+in currents were −18 ± 2.2 mV (n = 4) and −24 ± 1.6 mV (n = 6), respectively. Potassium ions were the only ions under the imposed conditions that had a significantly negative equilibrium potential (EK+ = −28.7 mV). The reversal potential therefore indicates that the outward IAP is carried mainly by K+. The 10.7 mV more positive reversal potential for IAP when compared with EK+ could be caused by Cl−, Ca2+, or Mg2+ permeation because ECl− ≈ 0 mV, ECa2+ > +120 mV and EMg2+ = 0 mV, which are all positive to EK+. After substitution of KCl by K-gluconate to reduce background anion currents, K+in reversed at −31.8 ± 2.0 mV (n = 8; EK+ = −30 mV), whereas the reversal potential of IAP was virtually unaffected (EIAP = −16.5 ± 2.6 mV; n = 3), indicating that IAP is not significantly anion permeable. Therefore, both ion substitution and reversal potential measurements show that the outward IAP is carried mainly by K+ with negligible anion permeability (35), and that K+in was more K+ selective than IAP. In additional experiments, increasing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration from 1 mM to 40 mM with either Cl− or gluconate as the anions caused a positive shift in the reversal potential of IAP (n = 12), showing that IAP channels have a permeability to Ca2+.

Effect of Extracellular Ca2+ and K+ on IAP.

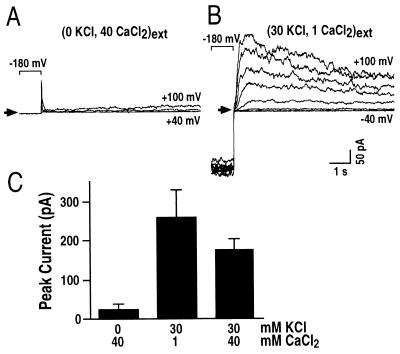

When K+ ions in the bath solution ([K+]o) were substituted by Ca2+, IAP was abolished (Fig. 3A). For these cells when the bath was then perfused with a solution containing 30 mM KCl and 1 mM CaCl2, IAP was restored (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that Ca2+ may inhibit IAP and/or [K+]o may be required for IAP activation. Further experiments were designed to test these possibilities by simultaneously adding both 30 mM K+ and 40 mM Ca2+ to the bath solution. Fig. 3C shows that increasing extracellular Ca2+ concentration from 1 mM (Center) to 40 mM (Right) decreased IAP amplitudes, suggesting an inhibitory effect of extracellular Ca2+ on IAP. Increasing [K+]o from 0 mM (Fig. 3C, Left) to 30 mM (Fig. 3C, Right) dramatically enhanced IAP amplitudes, indicating that [K+]o is required for IAP activation. Varying [K+]o (0, 1, 10, and 40 mM) confirmed that [K+]o activates IAP, whereas IAP activation potentials were not significantly shifted by varying [K+]o (n = 23; data not shown). This increase in outward K+ current, on increasing [K+]o is reminiscent of depolarization-activated K+ channels in animal cells (26). These characteristics of IAP are opposite to those described for the sustained K+out currents found in V. faba and Arabidopsis guard cells, where increasing [K+]o decreases K+out currents, via a positive shift in the activation potential (6, 16, 36).

Figure 3.

Extracellular Ca2+ inhibits IAP and extracellular K+ is required for IAP. (A) Whole-cell currents recorded in a bath solution with zero mM KCl and 40 mM CaCl2 show inhibition of IAP. (B) IAP was restored when the bath was perfused with a standard bath solution containing 30 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2. IAP was recorded in the same cell as in A. Similar results were found in eight cells. Arrows show zero current levels in A and B. (C) Average effects of extracellular Ca2+ and K+ concentrations on IAP (n = 5–8). A pipette solution with nominally zero Ca2+ and bath solutions with varying Ca2+ and K+ concentrations as indicated (in mM) were used.

IAP Recovery Is Dependent on the Degree and Duration of Prehyperpolarization.

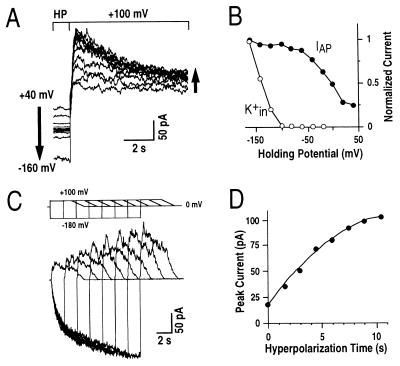

To quantitatively analyze the effect of negative prepulse holding potentials on recovery of IAP, experiments were designed to compare IAP peak amplitudes after various prepulse holding potentials ranging from +40 to −160 mV (Fig. 4A). The potential was held for 60 sec at the indicated holding potentials before depolarization to saturate IAP recovery. More negative holding potentials increased IAP recovery, demonstrating that a hyperpolarized membrane potential was required for IAP recovery (Fig. 4 A and B). IAP magnitudes reached a plateau for prepulse holding potentials more negative than ≈−100 mV (Fig. 4B). The midpoint of membrane potentials required for IAP recovery was ≈−20 mV under the imposed conditions. K+in currents were not required for IAP because IAP magnitudes were large at prepulse membrane potentials ranging from −40 to −100 mV, whereas at these potentials K+in currents were not activated. Thus these data demonstrate that physiological resting potentials negative of −100 mV favor the full recovery of IAP in Arabidopsis guard cells.

Figure 4.

IAP magnitudes are enhanced by more negative prepulse holding potentials and by longer hyperpolarization times. (A) IAP magnitudes were enhanced when prehyperpolarization potentials were more negative. Left arrow shows the changes of holding potentials, and right arrow indicates the associated increasing IAP amplitudes. Prehyperpolarizations ranged from +40 mV to −160 mV in increments of −20 mV. The interval time between pulses was 60 sec at holding potential (HP). (B) Normalized IAP peak amplitudes and K+in currents plotted against respective prepulse holding potentials for the data in A. Similar results were analyzed in three representative cells. (C) Increasing durations of prehyperpolarizations enhanced the magnitude of IAP. Data from a representative cell show increasing prehyperpolarization times at −180 mV. (Upper) Voltage protocol is shown. In the voltage protocol, voltage ramps were used after depolarization to stabilize the cells because large prolonged and repetitive depolarizing voltage pules often led to loss of whole-cell recordings. (D) IAP peak amplitudes plotted against respective prepulse hyperpolarization times from experiments performed as in C. Similar results were obtained in four cells. A pipette solution with nominally zero Ca2+ concentration and a standard bath solution were used.

The duration of prehyperpolarization required for IAP recovery was analyzed. Voltage protocols were used with increasingly prolonged prehyperpolarization times between pulses from zero to 10.5 sec (Fig. 4C, Upper). IAP peak amplitudes increased with increasing hyperpolarization times (Fig. 4 C and D). IAP peak amplitudes did not reach maximum levels even with 10.5 sec of prehyperpolarization. Maximum current levels could be reached only with approximately 20 sec of prehyperpolarization at −180 mV. The half prehyperpolarization time at −180 mV required for IAP recovery was 5.2 ± 1.7 sec (n = 4). The finding that IAP activation can be recovered by both the degree and duration of prehyperpolarization demonstrated that the decay of IAP during depolarization is analogous to inactivation found for A-type K+ channels in animal cells (23–26), as well as inactivation found for rapid anion channels (37) and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (38) in plant cells.

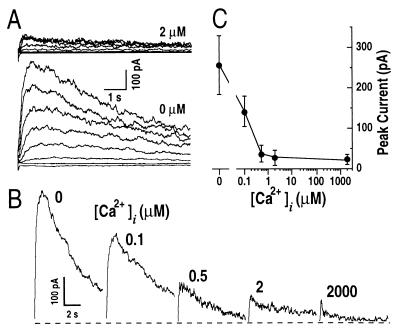

Cytosolic Ca2+ Inhibition of IAP.

Stimulus-induced increases in cytosolic Ca2+ play an important role in many plant signal transduction processes, for example in abscisic acid (ABA)-induced stomatal closing (39–41). The sustained K+out currents appear not to be modulated by physiological changes in cytosolic Ca2+ in guard cells (35, 42, 43). Unexpectedly, IAP was strongly inhibited by increases in cytosolic free Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i) in the physiological range (Fig. 5). IAP peak amplitudes were larger at nominally zero [Ca2+]i than those at 2 μM [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5A). This inhibition by [Ca2+]i was further tested over a range of [Ca2+]i from nominally zero to 2 mM and confirmed the strong down-regulation of IAP by [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5 B and C). The average effect of cytosolic Ca2+ shows an 8.9-fold ± 2.5-fold decrease of IAP by increasing [Ca2+]i from nominally zero to 2 μM (Fig. 5C). A Hill curve could be fitted to the data showing a Kd of ≈94 nM for a Hill coefficient of 1 (26). These data indicate that even small physiological changes in [Ca2+]i could efficiently up- and down-regulate IAP, which may imply an important physiological role of IAP in connection to Ca2+-dependent signal transduction pathways in Arabidopsis guard cells.

Figure 5.

Cytosolic free Ca2+ elevation inhibits IAP. (A) Representative whole-cell IAP recorded at [Ca2+]i of 2 μM (Upper) and nominally zero (Lower). The voltage protocol was as given in Fig. 1B. (B) IAP measured under various [Ca2+]i in the recording pipettes ranging from zero to 2,000 μM. Voltage protocol was the same as in Fig. 1B. Only current traces at +100 mV are shown. Dashed line shows zero current level. (C) Effect of [Ca2+]i on IAP peak amplitudes at +100 mV from experiments as performed in B (n = 5–12). Pipette solutions varied only in the free Ca2+ concentrations. The bath solution was the standard bath solution.

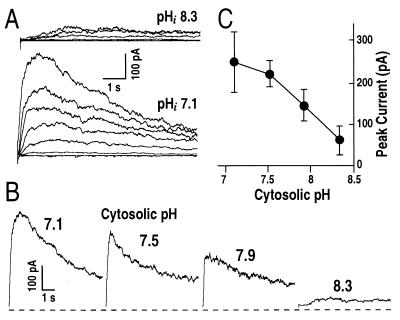

Inhibition of IAP by Cytosolic Alkaline pH.

ABA induces cytosolic alkalization (41, 44). Alkalization of cytosolic pH (pHi) has been found to up-regulate the sustained K+out currents in the plasma membrane of V. faba guard cells (44, 45). We therefore determined whether cytosolic alkalization affects IAP found in Arabidopsis guard cells.

Surprisingly, when pHi was shifted to more alkaline values from 7.1 to 8.3, IAP was dramatically decreased (Fig. 6). Examples of currents recorded at two different pHi values of 7.1 and 8.3 illustrate that pHi 8.3 inhibited IAP (Fig. 6A). Fig. 6B shows in more detail that IAP was decreased by cytosolic alkalization. Fig. 6C shows the decrease of IAP as pHi increased from 7.1 to 8.3. Besides the decreased current amplitudes with cytosolic alkalization, the half-activation time at +100 mV for IAP appeared to be dramatically increased from τa = 86 msec at pHi 7.1 to τa = 820 msec at pHi 8.3 (Fig. 6B). It is possible that IAP is completely inhibited by alkaline pHi and that the small currents recorded at pHi 8.3 (Fig. 6 A and B) correspond to a small residual sustained K+out currents (6) rather than IAP.

Figure 6.

Cytosolic alkaline pH inhibits IAP. (A) Representative IAP recorded under pHi 8.3 (Upper) and pHi 7.1 (Lower). (B) IAP at +100 mV measured under various pHi from 7.1 to 8.3. The voltage protocol was the same in A and B as given in Fig. 1B, but only current traces at +100 mV are shown in B. (C) Effect of pHi on IAP peak amplitudes at +100 mV from experiments as performed in B (n = 4–12). Pipette solutions with nominally zero free Ca2+ concentrations and varied pHi, and standard bath solution were used.

DISCUSSION

IAP shows functional characteristics different from the sustained plant K+out channels characterized in many cell types and the cloned Arabidopsis KCO1 channel. Several major differences are apparent between IAP and K+out currents. First, IAP is a higher plant K+ current that shows a pronounced inactivation with time (Fig. 1), a characteristic not seen for the noninactivating K+out currents (3–16). Second, the pH sensitivity of IAP is opposite to that of the K+out currents in V. faba guard cells: IAP is inhibited by alkaline cytosolic pH (Fig. 6), whereas K+out currents are enhanced by alkaline pH shifts (44, 45). Third, the regulation of IAP by [K+]o is also opposite to that of K+out and KCO1. Decreasing [K+]o shifts the activation potential of K+out to more negative values and enhances current amplitudes (6, 14, 16, 36). Similar results to K+out were observed for KCO1 expressed in insect cells (18). However, decreasing [K+]o did not greatly affect the activation potential of IAP and in addition decreased the amplitudes of IAP. In a recent study, two components of outward K+ currents, one showing instantaneous and another slow time-dependent activation with slight inactivation, have been characterized in Arabidopsis guard cells (6). Both the instantaneous and time-dependent currents were enhanced by decreasing [K+]o via a negative shift of activation potentials (6), which is opposite and therefore distinct from the time-dependent IAP. Finally, cytosolic Ca2+ in general does not regulate K+out currents in guard cells (35, 42, 43), and in some cells [Ca2+]i up-regulates K+out currents (10, 18, 22). IAP showed the unique characteristics of being down-regulated by physiological [Ca2+]i increases (Fig. 5).

IAP Has Properties Similar to A-Type K+ Channels in Animal Cells.

First, IAP inactivates with prolonged depolarization time (Fig. 1). Animal A-type K+ channels show variable inactivation with two distinct types of inactivation mechanisms, N-type and C-type (23, 46–48). N-type inactivation involves the binding of a tethered blocking particle, containing positively charged N-terminal amino acids to the cytoplasmic face of the channel (46, 47). The exact mechanisms of C-type inactivation (containing C-terminal amino acids) are unknown, but may involve a constriction of the outer mouth of the pore, preventing conduction (48, 49). The mechanisms of inactivation for IAP remain to be determined. Second, IAP was dependent on [K+]o (Fig. 3). Depolarization-activated K+ channel currents in animal cells are enhanced by increasing [K+]o (26). Furthermore, the recovery of A-type currents from both N-type and C-type inactivation is dependent on [K+]o (50, 51). Third, activation of IAP is voltage-dependent and the inactivation is voltage-independent at positive potentials (Fig. 1 F and H), which also has been reported for A-type channels (23). Fourth, the recovery of IAP activity from inactivated states is time- and voltage-dependent at negative potentials (Fig. 4), which resembles A-type channel recovery from both C-type and N-type inactivation (50, 51). Finally, IAP was reduced by increasing [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5). This property may be similar to A-type channels where after inactivation, high [Ca2+]i prevents K+ current reactivation (52). Whether IAP channels are structurally related to animal A-type K+ channels, however, remains unknown.

Possible Physiological Functions of IAP.

K+out channels in guard cells are proposed to serve as major sustained K+ efflux pathways, leading to full stomatal closure in response to strong stimuli such as long periods of dark and drought stress (1, 3). The prominent inactivation of IAP indicates that this current is unlikely to be involved in sustained K+ efflux lasting many minutes, but may be involved in short-term and transient K+ efflux as a signal leading to adjustments in stomatal apertures. For example, during ABA-induced stomatal closure, an initial transient efflux of K+ (Rb+) and Cl− is observed followed by a sustained efflux phase (53). It is possible that IAP contributes a component to this transient K+ efflux, which acts as a signal to initiate stomatal closing. A transient component of total outward current also was observed in some tobacco guard cells (5), suggesting that IAP may occur and function in other plant species. Furthermore, [K+]o was required for IAP, also implicating a physiological role for autoregulation of K+ currents by [K+]o as feed forward mechanism to enhance transient K+ efflux in Arabidopsis guard cells.

Potassium channels play a central role in controlling cell membrane potential (1, 2, 17, 23, 26). Repetitive transient depolarizations or oscillations have been observed in V. faba and Arabidopsis guard cells (30, 31, 54). These membrane potential oscillations have been proposed to function as a feedback mechanism for fine tuning of stomatal apertures (30, 31, 54). Rapid depolarization has been proposed to be initiated by anion channel activation, mediating anion efflux, in particular rapid anion channel activation (55). Interestingly, both rapid anion channel currents (56) and IAP (Fig. 6) show enhancement at more acidic pHi. Consistent with these findings, a recent study in Arabidopsis guard cells has demonstrated that buffering pHi to ≤pH 7.0 triggers repetitive rapid depolarizations (31). Furthermore, the repolarization time constants measured in guard cells (≈150 ms; refs. 30, 31, and 54) are similar to the activation time constants of IAP (τa ≈ 80–220 ms; Fig. 1), indicating that IAP could contribute to the repolarization process. Therefore, physiological membrane potential depolarizations may activate IAP in vivo, subsequently causing repolarization, suggesting that IAP may be an integral component of guard cell firing patterns as described for A-type channels in animal cells (26, 28, 29).

Both [Ca2+]i and pHi are important second messengers in guard cells (39–45). For instance, during ABA-induced stomatal closing increases of [Ca2+]i have been reported in guard cells (35, 39–41). However, it appears unlikely that IAP functions downstream of the Ca2+-dependent ABA signaling pathway, because ABA-induced increases of [Ca2+]i may inhibit IAP in Arabidopsis guard cells. Increases of [Ca2+]i in guard cells also have been observed during light-induced stomatal opening (41). [Ca2+]i has been suggested to function as a versatile signal transducer in guard cells that can affect both stomatal opening and closing (41). For example, Ca2+-dependent protein kinases activate vacuolar Cl− channel and malate uptake currents, which were suggested to function in Ca2+-dependent-stomatal opening (57). Therefore, Ca2+-permeable IAP may function in other Ca2+-dependent signal transduction pathways.

In conclusion, we present a characterization of an inactivating K+ channel current in a higher plant cell. The unique characteristics of IAP inactivation and regulation by diverse factors including membrane potential, cytosolic Ca2+, cytosolic pH, and extracellular K+ imply that IAP may have important roles in the adjustment of stomatal apertures during repetitive transient depolarizations, during early rapid phases of K+ efflux for stomatal closing, and/or during integrated signal transduction processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Thomine for help with data analysis, E. J. Kim for comments on the manuscript, and X.-F. Cheng for technical assistance. This research was supported by Department of Energy (94-ER20148) and National Science Foundation (MCB-9506191) grants (to J.I.S.). V.M.B.-A. was supported in part by a Pew Foundation Latin American fellowship, and G.J.A. was supported by a Human Frontier Science Program fellowship.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: [Ca2+]i, cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration; IAP, plant A-type K+ current; K+in, inward-rectifying K+ channel; K+out, outward-rectifying K+ channel; [K+]o, extracellular K+ concentration; pHi, cytosolic pH; ABA, abscisic acid.

References

- 1.Assmann S M. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:345–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schroeder J I, Ward J M, Gassmann W. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1994;23:441–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroeder J I, Raschke K, Neher E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4108–4112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairley-Grenot K A, Assmann S M. Planta. 1993;189:410–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00194439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong F, Leung J, Grabov A, Brearley J, Giraudat J, Blatt M R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9520–9524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roelfsema M R G, Prins H B A. Planta. 1997;202:18–27. doi: 10.1007/s004250050098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pei Z-M, Kuchitsu K, Ward J M, Schwarz M, Schroeder J I. Plant Cell. 1997;9:409–423. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iijima T, Hagiwara S. J Membr Biol. 1987;100:73–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02209142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moran N, Fox D, Satter R L. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:424–431. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoeckel H, Takeda K. J Membr Biol. 1995;146:201–209. doi: 10.1007/BF00238009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spalding E P, Slayman C L, Goldsmith M H M, Gradmann D, Bertl A. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:96–102. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomine S, Zimmermann S, Van Duijn B, Barbier-Brygoo H, Guern J. FEBS Lett. 1994;340:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schachtman D P, Tyerman S D, Terry B R. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:598–605. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.2.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts S K, Tester M. Plant J. 1995;8:811–825. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maathuis F J M, Sanders D. Planta. 1995;197:456–464. doi: 10.1007/BF00196667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeder J I. J Gen Physiol. 1988;92:667–683. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tester M. New Phytol. 1990;114:305–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1990.tb00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Czempinski K, Zimmermann S, Ehrhardt T, Müller-Röber B. EMBO J. 1997;16:2565–2575. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ketchum K A, Joiner W J, Sellers A J, Kaczmarek L K, Goldstein S A N. Nature (London) 1995;376:690–695. doi: 10.1038/376690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein S A N, Price L A, Rosenthal D N, Pausch M H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13256–13261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duprat F, Lesage F, Fink M, Reyes R, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. EMBO J. 1997;16:5464–5471. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ketchum K A, Poole R J. J Membr Biol. 1991;119:277–288. doi: 10.1007/BF01868732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:91–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagiwara S, Kusano K, Saito N. J Physiol (London) 1961;155:470–489. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neher E. J Gen Physiol. 1971;58:36–53. doi: 10.1085/jgp.58.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2nd Ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodgkin A L, Huxley A F. J Physiol (London) 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman D A, Magee J C, Colbert C M, Johnston D. Nature (London) 1997;387:869–875. doi: 10.1038/43119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debanne D, Guérineau N C, Gähwiler B H, Thompson S M. Nature (London) 1997;389:286–289. doi: 10.1038/38502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiel G, MacRobbie E A C, Blatt M R. J Membr Biol. 1992;126:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00233456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roelfsema M R G. Ph.D. thesis. The Netherlands: Assen; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamill O P, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth F J. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neher E. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:123–131. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kourie J, Goldsmith M H M. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:1087–1097. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.3.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schroeder J I, Hagiwara S. Nature (London) 1989;338:427–430. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blatt M R. J Membr Biol. 1988;102:235–246. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedrich R, Busch H, Raschke K. EMBO J. 1990;9:3889–3892. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thuleau P, Ward J M, Ranjeva R, Schroeder J I. EMBO J. 1994;13:2970–2975. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McAinsh M R, Brownlee C, Hetherington A M. Nature (London) 1990;343:186–188. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schroeder J I, Hagiwara S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9305–9309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irving H R, Gehring C A, Parish R W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1790–1794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blatt M R, Thiel G, Trentham D R. Nature (London) 1990;346:766–769. doi: 10.1038/346766a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lemtiri-Chlieh F, MacRobbie E A C. J Membr Biol. 1994;137:99–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00233479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blatt M R, Armstrong F. Planta. 1993;191:330–341. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miedema H, Assmann S M. J Membr Biol. 1996;154:227–237. doi: 10.1007/s002329900147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armstrong C M, Bezanilla F. J Gen Physiol. 1977;70:567–590. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.5.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoshi T, Zagotta W N, Aldrich R W. Science. 1990;250:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.2122519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi K L, Aldrich R W, Yellen G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5092–5095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panyi G, Sheng Z, Tu L, Deutsch C. Biophys J. 1995;69:896–903. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79963-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Demo S D, Yellen G. Biophys J. 1992;61:639–648. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81869-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levy D I, Deutsch C. Biophys J. 1996;71:3157–3166. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79509-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herrington J, Solaro C R, Neely A, Lingle C J. J Physiol. 1995;485:297–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacRobbie E A C. J Exp Bot. 1981;32:563–572. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gradmann D, Blatt M R, Thiel G. J Membr Biol. 1993;136:327–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00233671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kolb H A, Marten I, Hedrich R. J Membr Biol. 1995;146:273–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00233947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schulz-Lessdorf B, Lohse G, Hedrich R. Plant J. 1996;10:993–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pei Z-M, Ward J M, Harper J F, Schroeder J I. EMBO J. 1996;15:6564–6574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]