Abstract

Initiation of eukaryotic DNA synthesis occurs at origins of replication that are utilized with characteristic times and frequencies during S phase. We have investigated origin usage by evaluating the kinetics of replication factor binding in fission yeast and show that similar to metazoa, ORC binding is periodic during the cell cycle, increasing during mitosis and peaking at M/G1. At an origin, the timing of ORC binding in M and pre-RC assembly in G1 correlates with the timing of firing during S, and the level of pre-IC formation reflects its efficiency. Extending mitosis causes ORC to become more equally associated with origins and leads to genome-wide changes in origin usage, while overproduction of pre-IC factors increases replication of both efficient and inefficient origins. We propose that differential recruitment of ORC to origins during mitosis followed by competition among origins for limiting replication factors establishes the timing and efficiency of origin firing.

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, DNA synthesis begins at origins of replication throughout the genome. During each S phase, a cell utilizes a subset of its origins which fire at characteristic times, indicative of a program of origin usage (Aladjem, 2007). The frequency of origin usage in a population is defined as its efficiency. Origins of replication have been identified from yeast to human, but little is known about the regulation of their timing and efficiency, in particular how the steps in replication initiation are controlled to generate the replication program. In this paper we investigate the timing of origin firing and the efficiency of origin usage in a unicellular eukaryote, the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

Initiation of DNA replication requires the coordinated assembly of a number of components (reviewed in Bell and Dutta, 2002). First, ORC (Origin Recognition Complex) selects the sites for initiation by directly binding to origins. Next, in G1, Cdc6, Cdt1, and ORC recruit the MCM helicase, completing pre-RC (pre-replicative complex) formation. Finally, Cdc45 binding is necessary for loading the enzymes required for DNA synthesis, forming the pre-IC (pre-initiation complex) and bringing about replication initiation. The basic mechanism for initiation is conserved among organisms, but one major difference is the regulation of ORC. In budding yeast, ORC association with origins is constant during the cell cycle (Aparicio et al., 1997; Diffley, 1994), and re-replication is prevented by phosphorylation of specific subunits (Nguyen et al., 2001; Remus et al., 2005). In contrast, in Xenopus egg extracts, chromatin binding of ORC is low upon entry into mitosis, increasing at anaphase/telophase, and ORC is released from chromatin during S (Romanowski et al., 1996; Sun et al., 2002). In mammalian cells, Orc1 association with chromatin is low in mitosis, rebinding as cells exit M and enter G1 and dissociating from chromatin at the end of S (Li and DePamphilis, 2002); others find that Orc1 associates with chromatin as cells proceed through telophase (Okuno et al., 2001).

The DNA sequences that define origins vary more widely than the components required for replication. The most well-studied eukaryotic chromosomal replication origins are those of budding yeast, which were identified as autonomously replicating sequences (ARS) with an 11 bp ARS consensus sequence (ACS) essential for origin function (Broach et al., 1983; Stinchcomb et al., 1979). Most origins in budding yeast fire efficiently, on average once every two cell cycles (Friedman et al., 1997; Poloumienko et al., 2001; Yamashita et al., 1997). In contrast, origins in most other eukaryotes neither fire efficiently nor contain a strict consensus sequence (Aladjem, 2007). Metazoan origins have a more extended structure and may not have a specific sequence requirement, as replication occurs at a number of possible sites on DNA introduced into Xenopus eggs and egg extracts and in Drosophila early embryos (Hyrien and Mechali, 1992; Shinomiya and Ina, 1991). It has been difficult to define the elements that constitute a complex eukaryotic origin, although studies to map metazoan origins will help to clarify this issue (Lucas et al., 2007; Mesner et al., 2006).

The fission yeast is a useful system for studying eukaryotic origin usage. Nearly all potential origins have been identified, and as in metazoan eukaryotes, there is no known consensus sequence for origins (Feng et al., 2006; Hayashi et al., 2007; Heichinger et al., 2006). Origins in fission yeast consist of asymmetric A-T stretches of around 1 kb in length with multiple AT-hook motifs which serve as targets for ORC (Bell and Dutta, 2002). The study from our laboratory identified 401 strong and 503 putative origins that fire throughout S and are used with a continuum of efficiencies (Heichinger et al., 2006). Only a few origins are used as frequently as once in every two cell cycles, and most origins fire in less than one out of every ten cell cycles (Dai et al., 2005; Heichinger et al., 2006). Finally, there is a strong correlation between origin efficiency and timing: generally, efficient origins fire early in S, while inefficient origins are late-firing (Heichinger et al., 2006).

In this paper, we investigate the control of origin usage by determining the kinetics of replication factor binding and their effects on the replication program in fission yeast. Our results indicate that the timing and efficiency of origin firing is established during the mitosis of the previous cell cycle and the G1 prior to S phase, followed by competition among origins for limiting replication factors.

Results

Replication initiation at an efficient origin

We investigated the steps leading to fission yeast origin activation to determine if the timing of ORC binding, pre-RC formation, and pre-IC assembly influences origin firing. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was used to monitor replication factor binding at three origins (Fig. 1A): ori2004, an efficient and early-firing origin; ori2060, an inefficient and late-firing origin; and ars727, a cryptic origin that fires on a plasmid but not in its normal chromosomal context. Synchronized cultures were obtained by arresting cdc25-22 cells at 36.5°C for 4 hours in late G2 before releasing at 25°C for entry into mitosis (M), G1, and S phase (S) (Fig. 1B). Estimates for cell cycle phases by DAPI staining and FACS analysis showed that M occurred by 30 minutes and that S began around 50 minutes and proceeded until 80 minutes after shift to 25°C.

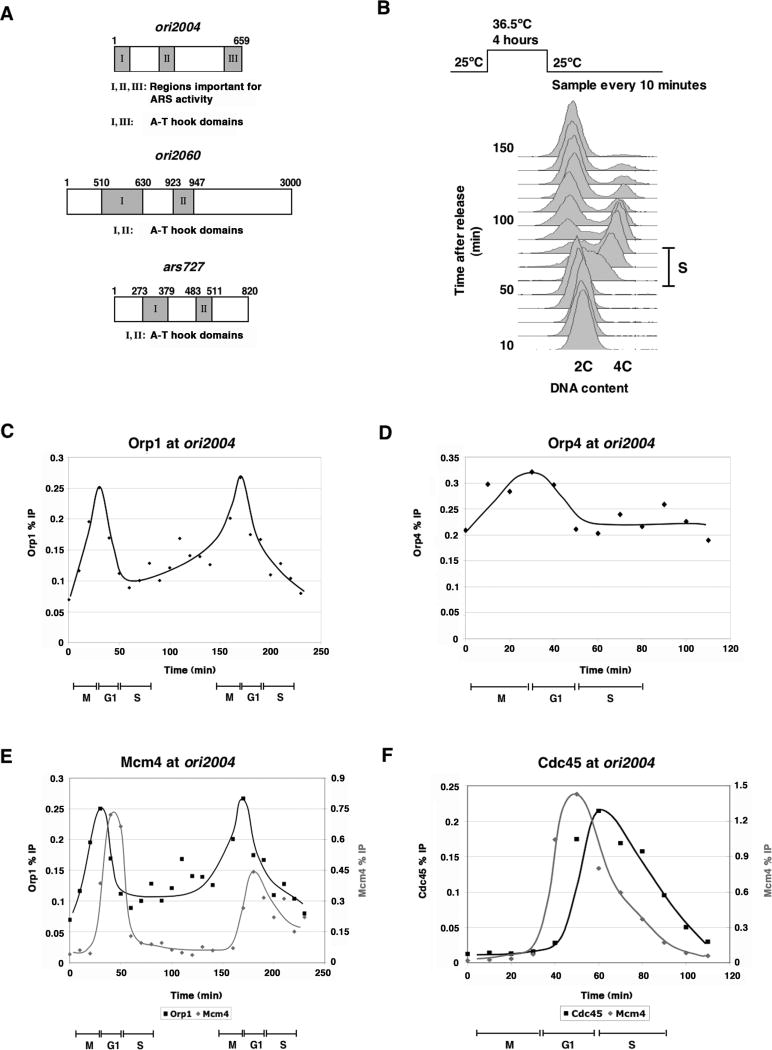

Figure 1. ChIP analysis of ORC, pre-RC and, pre-IC binding at ori2004.

A) Schematic of ori2004 and ori2060 (figure not drawn to scale). B) FACS analysis indicates that S occurs between 50 and 80 minutes after release from cdc25-22 arrest. C) Orp1 binding to ori2004 was assayed in a synchronous culture after release from cdc25-22 arrest. Each point represents the result of qPCR using primers over region III. Orp1 binding to ori2004 is periodic during the cell cycle, reaching a maximum at M/G1. D) Association of an integrated, fully functional Orp4-HA fusion with ori2004 as determined by ChIP. The same primers as in (C) were used. Orp4 shows similar timing and periodicity of binding at ori2004 as Orp1. E) Comparison of Orp1 and Mcm4 binding during the cell cycle. Each Mcm4 point represents the occupancy over region II of ori2004. F) The peak of Cdc45 association with ori2004 coincides with the start of replication, after maximal Mcm4 binding. IPs were performed from the same extracts, and each point represents the occupancy over region II of ori2004.

ori2004, which has an A-T content of 76% and contains two AT-hook motifs in regions I and III, has an efficiency of 50% in mitotic S and is one of the earliest firing origins (Okuno et al., 1997; Okuno et al., 1999). To determine Orp1 (the orthologue of Orc1 in other organisms) binding at ori2004, we immmunoprecipitated a fully functional orp1-HA fusion protein expressed from its endogenous locus (Grallert and Nurse, 1996). qPCR analysis showed that Orp1 bound specifically to ori2004, with a peak of binding at region III (Supp. Fig. 1A). Orp1 binding to ori2004 showed cell-cycle periodicity: in two successive cell cycles, levels of Orp1 binding reached a maximum around the M to G1 transition (Fig. 1C), 20 minutes before the start of replication. To ascertain whether other subunits of ORC exhibit this periodicity, we monitored the binding of Orp2 and Orp4 at ori2004. Both proteins showed similar kinetics of recruitment as Orp1, suggesting that the ORC complex binds periodically to ori2004, with maximal association occurring at M/G1 and reduced levels bound at other cell cycle stages (Fig. 1D, see Supp. Fig. 1B for Orp2 binding). These results should be compared with earlier studies that reported no major changes in ORC association with chromatin (Lygerou and Nurse, 1999) or with origins (Ogawa et al., 1999) during the cell cycle. In our present experiments, we used closely-spaced time points and qPCR assays which are more sensitive than the ethidium bromide staining of agarose gels used previously to assay ORC association with origins. We conclude that ORC binding to an early, efficient origin in fission yeast is periodic during the cell cycle, increasing during M and peaking at M/G1 before the start of S, behavior that is similar to metazoan eukaryotes (DePamphilis, 2005).

Next, we investigated the relationships between the periodicity of ORC binding, pre-RC formation, and pre-IC assembly. As a marker for pre-RC formation, recruitment of MCM was monitored using a polyclonal antibody to Mcm4 (Nishitani et al., 2000). Maximal binding of Mcm4 occurred in G1, after peak ORC binding and before S, and Mcm4 binding was sharply periodic during the cell cycle (Fig. 1E, Supp. Fig. 1C). Pre-IC assembly was assayed by the recruitment of a functional Cdc45-YFP fusion protein to ori2004. For the strain containing Cdc45-YFP, S phase was delayed by 10 minutes, beginning 60 minutes after release from cdc25-22 arrest (data not shown). Cdc45 bound to region II of ori2004 (Supp. Fig. 1D), and its association was sharply periodic and delayed by 10 minutes compared with maximal Mcm4 binding (Fig. 1F). The co-occupancy of Cdc45 and Mcm4 on region II supports the idea that Cdc45 and MCM form a complex and that Cdc45 primes the activity of the MCM helicase (Moyer et al., 2006; Zou and Stillman, 2000). Our data are consistent with previous work showing MCM and Cdc45 recruitment to ori2004 (Ogawa et al., 1999; Yabuuchi et al., 2006), and our higher temporal resolution allows the more precise determination of timing for the recruitment of ORC, pre-RC, and pre-IC to origins. We conclude that there is a temporal separation between the three steps, with maximum ori2004 binding of ORC at M/G1, of pre-RC in G1, and of pre-IC at G1/S.

Replication initiation at inefficient and inactive origins

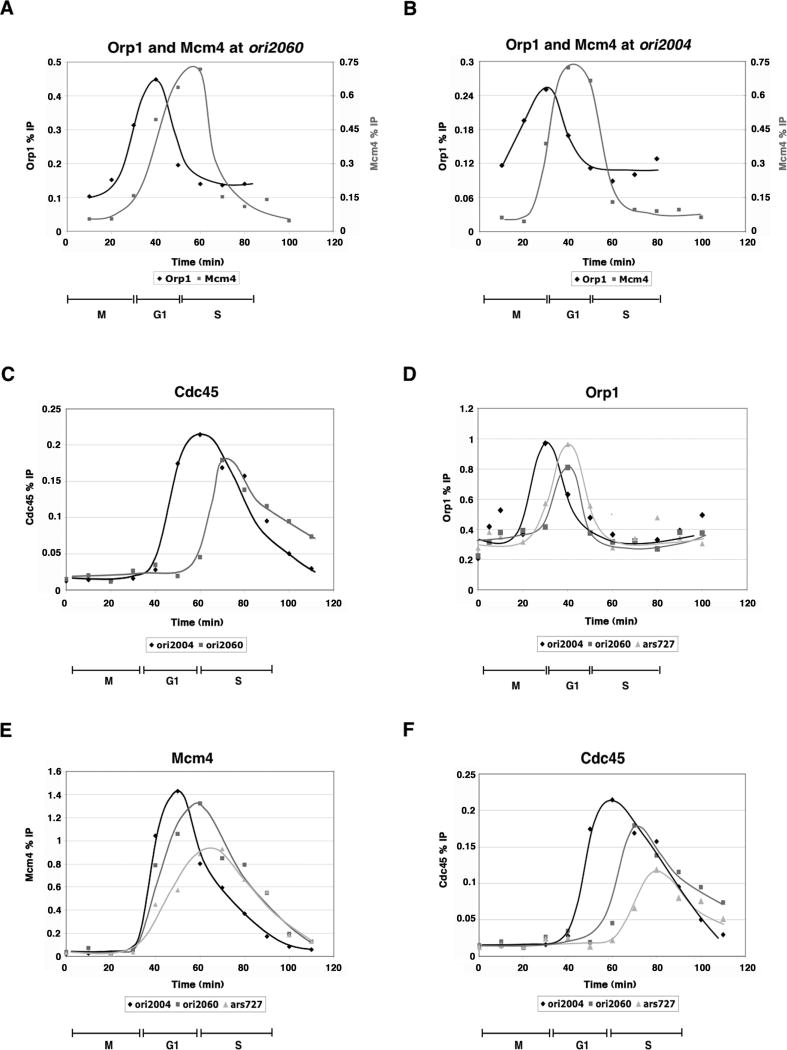

To determine if the kinetics of ORC, pre-RC and pre-IC recruitment contribute to the differences in the timing of origin firing, we analyzed these steps at ori2060. A schematic of this origin is shown in Figure 1A; ori2060 is 74% AT-rich and contains two strong AT-hook motifs. It is used at 10% efficiency and fires later in S, around 10 minutes after ori2004 (Heichinger et al., 2006); for reference, the length of S in fission yeast is around 30 minutes in a synchronous culture at 25°C (Fig. 1B). We assessed Orp1 and Mcm4 binding at ori2060 by ChIP, scanning a 2.5 kb region centered on ori2060. Orp1 bound periodically to a region between the two AT-hook motifs (Fig. 2A, Supp. Fig. 1E). Mcm4 binding was also periodic, reaching a maximum after the peak of ORC binding (Fig. 2A, Supp. Fig. 1F). However, compared to the timing of their binding to ori2004, maximal binding of both Orp1 and Mcm4 was delayed by around 10 minutes (compare Figs. 2A and 2B). In addition, we observed a 10 minute delay in the recruitment of Cdc45, similar to the delay in Mcm4 binding (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that a delay in ORC and pre-RC recruitment in mitosis and G1, respectively, results in a delay of origin firing during the subsequent S.

Figure 2. Pre-RC formation at an inefficient origin (ori2060) and an inactive origin (ars727).

A, B) Time course of Orp1 and Mcm4 binding at ori2060 and ori2004. For ori2060, each point represents the occupancy between the two AT-hook regions. Orp1 binding at ori2060 peaks around 40 minutes, while Mcm4 binding is maximal 50-60 minutes post-release from cdc25-22 arrest. ORC binding and pre-RC formation at ori2060 occur approximately 10 minutes later than at ori2004. C) Comparison of Cdc45 binding at ori2060 and ori2004. Maximal Cdc45 association at ori2060 is delayed compared to ori2004. D-F) Time course of Orp1 (D), Mcm4 (E), and Cdc45 (F) at ori2004, ori2060, and ars727 by ChIP shows a delay in ORC, pre-RC and pre-IC formation at late-firing and inefficient or inactive origins.

We also evaluated ars727, which functions as an autonomous replicating sequence on a plasmid (Maundrell et al., 1988). ars727 is 76% A-T rich and contains two AT-hook motifs, but it is inactive in its chromosomal context (Kim and Huberman, 2001). Our results showed a delay in Orp1 binding to ars727 compared with ori2004, similar to ori2060 (Fig. 2D). Mcm4 recruitment at ars727 was clearly delayed, occurring near the start of S (Fig. 2E). Cdc45 binding, which occurred halfway through S, showed a significant delay and a pronounced decrease at ars727 (Fig. 2F). The relatively high level of Cdc45 binding at an inactive origin is likely due to passive replication (see later). We conclude that ORC and pre-RC can be assembled at non-firing origins and that the timing of pre-RC assembly is delayed. As there are efficient origins on the chromosome near ars727, it is likely that by the time that ars727 is competent to recruit Cdc45, the region has already been passively replicated, preventing firing of the origin.

Reduction in ORC binding results in delayed pre-RC and pre-IC formation

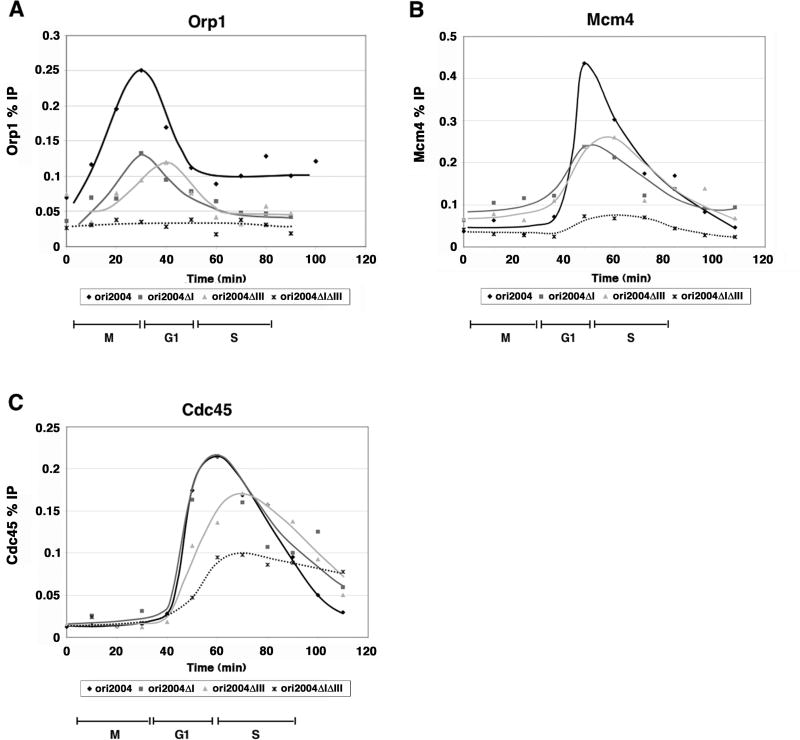

Our results suggest that the timing of ORC binding to origins is correlated with the timing of pre-RC and pre-IC binding and the timing of origin firing. We next asked whether changing the affinity of an origin for ORC affects its binding dynamics and pre-RC assembly. We utilized three deletions of ori2004: ori2004ΔI and ori2004ΔIII, lacking AT-hook motifs in regions I and III, respectively; and ori2004ΔIΔIII, lacking both AT-hook motifs. While deletion of either AT-hook motif alone does not dramatically affect origin activity, deletion of both motifs abolishes origin activity (Takahashi et al., 2003). Similar to intact ori2004, we find that Orp1 binding is periodic at both ori2004ΔI and ori2004ΔIII, peaking around M/G1 (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the increase in ORC binding does not require the presence of both AT-hook motifs. ori2004ΔI has no effect on the timing of the increase, but there is a delay in the peak of ORC binding at ori2004ΔIII. Consistent with published results, we observed little or no ORC binding in the doubly deleted ori2004ΔIΔIII mutant (Takahashi et al., 2003).

Figure 3. Reduction in ORC binding results in delays in pre-RC and pre-IC assembly.

A) Time course of Orp1 binding at wild type ori2004 and three mutant alleles: ori2004ΔI, ori2004ΔIII, and ori2004ΔIΔIII (see Figure 1A). For wild type and ori2004ΔI, each point represents the occupancy of Orp1 over region III; ori2004ΔIII occupancy was quantified using primers over region I, while ori2004ΔIΔIII was assayed using primers over region II. Orp1 binding is reduced in the single ori2004 mutants, absent in the double mutant, and specifically delayed in ori2004ΔIII. B, C) Comparison of Mcm4 and Cdc45 binding in wild type and ori2004 deletions. Primers over region II were used to determine occupancy for both Mcm4 (B) and Cdc45 (C). Mcm4 occupancy is reduced in the ori2004 mutants, and ori2004ΔIII shows a small delay in Mcm4 binding. Cdc45 binding is delayed in ori2004ΔIII and ori2004ΔIΔIII.

Next, we assessed Mcm4 and Cdc45 binding in these mutants. There is little effect on the timing of Mcm4 binding at ori2004ΔI although the peak level was significantly reduced. In contrast, ori2004ΔIII exhibited both delayed and reduced Mcm4 binding, and Mcm4 binding at ori2004ΔIΔIII was barely detectable (Fig. 3B). Similar to these results, the timing of Cdc45 binding was unaffected at ori2004ΔI, while it was delayed at ori2004ΔIII and ori2004ΔIΔIII (Fig. 3C). Moreover, Cdc45 levels were greatly reduced at ori2004ΔIΔIII (Fig. 3C). Analogous to ori2060 and ars727, the Cdc45 binding that we observe at ori2004ΔIΔIII is likely due to passive replication, as this mutant origin does not fire by 2-D gel analysis and binds little or no Orp1 and Mcm4 (Takahashi et al., 2003). The delay in Cdc45 binding to specific ori2004 deletions is reflected in the timing of replication at these origins. Replication at ori2004ΔIII and ori2004ΔIΔIII is delayed by 10 and 15 minutes, respectively (Supp. Fig. 2). These results indicate that ori2004 deletion mutants that reduce ORC binding can delay ORC binding, delay and reduce pre-RC and pre-IC formation, and delay the timing of replication.

Cdc45 recruitment correlates with origin efficiency

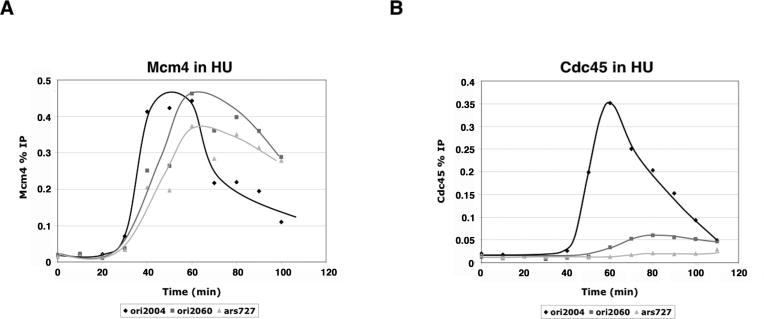

In the experiments described above, we observed high levels of Cdc45 binding at ori2060 and ars727 despite their inefficient usage, and we detected Cdc45 binding above background levels in regions adjacent to both ori2060 and ars727, suggesting that they are passively replicated (Supp. Fig. 3). To eliminate this complication, we released cells from cdc25-22 arrest into medium containing hydroxyurea (HU), which slows replication fork progression, limiting replication to a region around 10 kb centered on the origin (Heichinger et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2006). In contrast to budding yeast, the majority of origins are not subject to HU checkpoint repression in fission yeast (Hayashi et al., 2007; Heichinger et al., 2006; Mickle et al., 2007). Therefore, in our experiment, origin firing should still occur, but passive replication will be much reduced. We observed high levels of Mcm4 binding at all three origins, and the temporal sequence of pre-RC assembly was maintained (Fig. 4A). In contrast, levels of Cdc45 binding were drastically reduced at the late-firing and inefficient origins ori2060 and ars727 (Fig. 4B). The efficiencies of ori2004, ori2060 and ars727 are: 50%, 10%, <5% (Heichinger et al., 2006); if we assume linearity of the ChIP data and set the Cdc45 binding at ori2004 to 50%, then Cdc45 occupancy at ori2060 and ars727 is 10% and 4%, respectively. Therefore, we conclude that the level of Cdc45 bound at the origin in the presence of HU approximately reflects the efficiency of origin usage. We propose that in a normal S phase, the delay in pre-RC formation at a late-firing origin results in competition for a smaller pool of available replication factors that constitute the pre-IC. Furthermore, passive replication through the region inhibits delayed pre-IC formation at such an origin, resulting in reduced firing efficiency.

Figure 4. Mcm4 and Cdc45 binding in hydroxyurea (HU)-treated cells.

A) cdc25-22 synchronized cells were released into HU at 25°C for time course analysis. ChIP of Mcm4 at ori2004, ori2060, and ars727 show that pre-RC formation is generally not affected by HU treatment. B) HU treatment significantly reduces the maximal levels of Cdc45 binding at late-firing inefficient origins.

Reprogramming origin activity

Our data have revealed a correlation between the timing of ORC and MCM binding to origins and the timing of replication. We hypothesized that origins bind ORC during M with varying affinities, and that delays in ORC binding and pre-RC formation at late-firing origins result in low efficiencies due to these origins subsequently competing less effectively for limiting replication factors. To test this, we performed two sets of experiments. First, we investigated if equalizing ORC binding results in changes in origin efficiencies. Because the increase in ORC binding occurred during M, we surmised that extending M might result in origins accumulating ORC more equally, leading to more equal distribution of pre-RC and pre-IC assembly among origins. As a consequence, early origins might become less efficient and late origins more efficient. Second, we tested if there are limiting factors in replication by assessing if overproduction of candidate limiting factors would increase origin efficiency.

To extend M in cells, we used the drug MBC, which prevents microtubule polymerization and disrupts the mitotic spindle. MBC treatment of cells following synchronization using cdc25-22 prolonged mitosis and blocked S phase (Fig. 5A, left panel). Orp1 accumulated at ori2004, ori2060, and ars727 throughout the MBC treatment and reaches a maximum at the end of the extended M, confirming that ORC binding occurs during M (Fig. 5A, right panel). We found no detectable increase in the total cellular level of Orp1 protein during MBC treatment by Western analysis, suggesting that ORC is indeed redistributed among origins (data not shown). Mcm4 showed minimal binding (Supp. Fig. 4A), confirming that cells must enter G1 before pre-RC formation can take place and establishing that the increase in ORC binding can be uncoupled from MCM recruitment and pre-RC assembly.

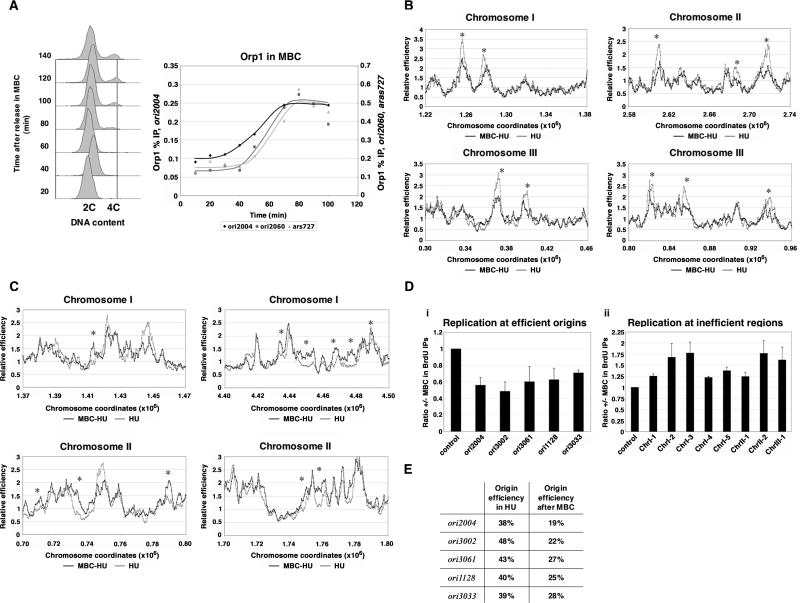

Figure 5. Extending mitosis alters origin efficiencies across the genome.

A) Left: FACS analysis of cells synchronized using cdc25-22 and released into MBC shows only a small susbset of cells entering S after 70 minutes. Right: ChIP of Orp1 from MBC-treated cells. Orp1 accumulates at ori2004, ori2060, and ars727 and remains bound during MBC treatment. B) Representative regions from array analyses showing reduction in the usage of early-firing efficient origins in cells treated with MBC and released into HU. MBC-treated and HU control cells are represented by black and gray lines, respectively. Asterisks mark reproducible decreases in three experiments. C) A subset of inefficient regions show increased BrdU incorporation after MBC treatment. Asterisks mark reproducible increases. D) Relative origin usage in MBC-treated samples and HU controls. BrdU IPs were assayed by qPCR. Bars represent the ratio of signal in MBC-treated to HU control samples, and a region that does not replicate in HU-treated cells was used for normalization. Values are averaged from three experiments, and error bars show the standard deviation. (i) The five efficient origins tested display reduced signals in the MBC samples. (ii) Eight low-efficiency regions, labeled by chromosome, show reproducible increases in replication after MBC treatment. (D) Origin efficiencies following MBC treatment. Replication efficiency was determined using qPCR of genomic DNA from both MBC-treated and HU-control cells. Values are averaged from three experiments.

Next, we assayed whether equalization of ORC binding led to equalization in origin usage. Origin efficiencies across the genome were determined in cells delayed in M using MBC. cdc25-22 cultures were arrested in G2 and treated with MBC 10 minutes before release into a synchronous cell cycle; after 65 minutes, MBC was washed out and cells released into media containing HU and BrdU. A schematic of the experimental design is shown in Supp. Fig. 4B, along with FACS profiles for the experiment. The efficiency of an origin can be assessed in HU-treated cultures, as origin firing can be measured in the absence of passive replication (Heichinger et al., 2006). BrdU-labeled fragments were isolated by immunoprecipitation of genomic DNA and hybridized to Affymetrix tiling arrays that cover the fission yeast genome at high resolution. These results were compared to the replication profile of cdc25-22 synchronized cells treated with HU but not with MBC, providing a control for normal origin efficiencies across the genome. This method allows the relative efficiency of origin usage genome-wide to be determined based on signal intensities from array hybridizations. Our results showed that many efficient early-firing origins were reduced in usage (Fig. 5B); of the top 50 most efficient origins (from Heichinger et al. 2006; Supp. Fig. 5), 86% were reduced in efficiency as assessed in three independent experiments. To confirm the results of the array analysis, we performed qPCR of BrdU IPs, and a significant reduction in efficiency was observed for all five origins tested in MBC treated cells (Fig. 5D). To determine actual origin efficiencies, we quantified unprocessed genomic DNA to compare the copy number of the five origins in MBC treated cells and HU controls using qPCR. These data show that after treatment with MBC, efficient origins replicate at around half of their normal efficiencies (Fig. 5E). In addition, some inefficient regions become replicated more efficiently (Fig. 5C). Results from three biological repeat experiments identified approximately 50 regions that showed reproducible increases in efficiency of replication, with an additional 50 regions that showed less pronounced increases. qPCR analysis of immunoprecipitated BrdU-labeled DNA at eight loci confirmed the increased usage (Fig. 5D). However, not all inefficient origins exhibited increased efficiencies; for example, ori2060 and ars727 efficiencies were largely unchanged (data not shown).

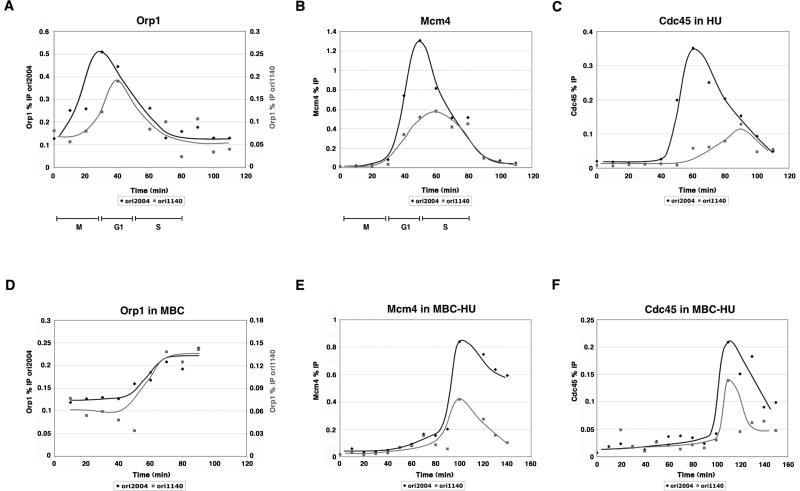

If the timing of ORC binding determines the timing and efficiency of origin firing, then pre-RC and pre-IC assembly should occur earlier at an origin whose efficiency has been increased as a result of MBC treatment. We characterized one such origin, ori1140 (Heichinger et al., unpublished results), for Orp1, Mcm4, and Cdc45 binding. During a synchronous cell cycle, we found that the binding of all three replication initiation factors occurred later at this origin than at ori2004 (Fig. 6A-C). After MBC treatment, we observed that ORC binding increased and reached a maximum at ori1140, suggesting equalization of ORC recruitment (Fig. 6D). We then assayed Mcm4 and Cdc45 binding in cells that undergo replication in the presence of HU after removal of MBC. Both Mcm4 and Cdc45 binding at ori1140 were advanced in timing after a prolonged mitosis, reaching a peak around the same time as at ori2004 (Fig. 6E-F). Therefore, equalizing ORC binding can advance the timing of pre-RC and pre-IC formation at a normally late-firing and inefficient origin.

Figure 6. Prolonging mitosis advances the timing of pre-RC and pre-IC formation at an induced origin, ori1140.

A-C) Time course of Orp1, Mcm4, and Cdc45 binding by ChIP shows that all three steps are delayed at ori1140 compared with ori2004. D) ChIP of Orp1 from MBC-treated cells. Orp1 accumulates at ori2004 and ori1140 and remains bound at the origin throughout the MBC treatment. E) The timing of Mcm4 and Cdc45 binding at ori1140 after MBC treatment and growth in HU is advanced and coincides with these events at ori2004.

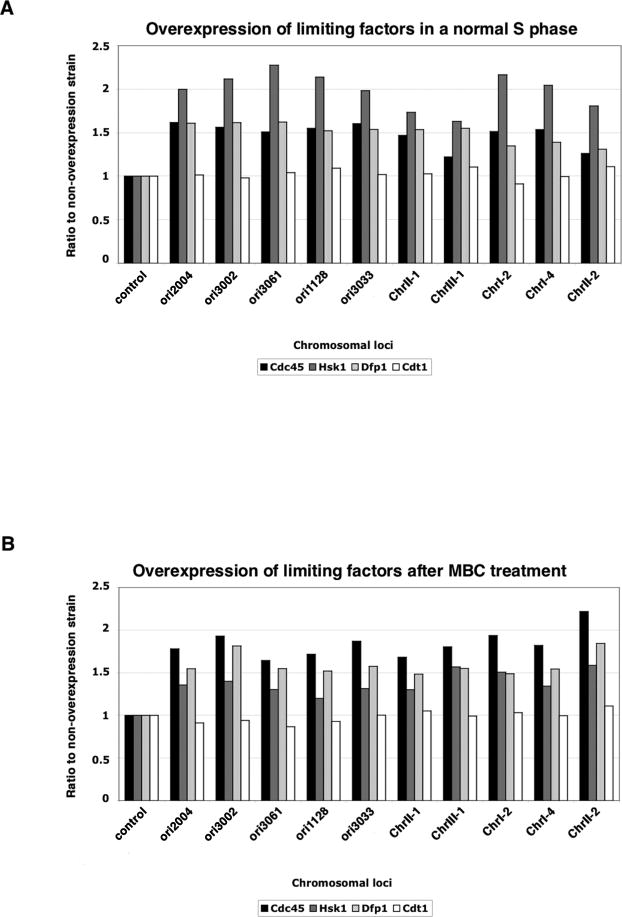

We have hypothesized that origin efficiencies are established by a combination of temporal regulation of ORC and pre-RC binding and limiting replication factors. If this is the case, then increasing the levels of these factors could lead to increased origin efficiency during S. We evaluated the effects of overproducing three factors involved in pre-initiation complex formation: Cdc45, Hsk1, and Dfp1. Hsk1, the homologue of the Cdc7 kinase, acts along with its activator Dfp1 to phosphorylate MCMs and Cdc45 to promote pre-IC assembly (Brown and Kelly, 1998). We expressed cdc45, hsk1, and dfp1 constitutively under the control of the thiamine-repressible nmt1 promoter in media lacking thiamine and evaluated the effect in cells treated with HU during a synchronous cell cycle. Replication is increased at a number of efficient and inefficient origins in strains overproducing Cdc45, Hsk1, of Dfp1 compared with a strain expressing wild type levels of these factors (Fig. 7A). In contrast, overexpression of the pre-RC component cdt1 from the nmt1 promoter does not increase replication from the tested origins (Fig. 7A, white bars). We also assessed replication in cells overproducing Cdc45, Hsk1, or Dfp1 that have been synchronized using cdc25-22 and treated with MBC followed by HU. This context allows us to determine whether origin efficiency can be similarly increased in an altered replication program. The results showed increased BrdU signal at a number of efficient and inefficient origins in strains overexpressing the candidate factors compared with non-overexpressing cells (Fig. 7B). Taken together, these data suggest that increasing levels of Cdc45, Hsk1, or Dfp1 result in increased replication from origins across the genome and therefore that their levels are normally limiting during S.

Figure 7. Overexpression of cdc45, hsk1, or dfp1 leads to increased replication.

A) BrdU signal is increased at efficient and inefficient origins in HU-treated synchronous cultures of strains overexpressing cdc45, hsk1, or dfp1. Bars represent the ratio of signal in overexpressing vs. wildtype cells, and a region that does not replicate in HU was used for normalization. Values are averaged from at least three experiments. B) Relative origin usage in cells constitutively overproducing Cdc45, Hsk1, or Dfp1 after MBC treatment. qPCR of BrdU IPs showed increased signal in overexpressing strains at both efficient and inefficient origins.

These results indicate that there is a redistribution of origin efficiencies among a number of origins after MBC treatment. We conclude that extending M so that ORC becomes more equally associated with a greater number of origins leads to an equilibration of origin efficiencies such that many efficient early origins are used less efficiently and a number of less efficient origins are used more efficiently. Moreover, we find that overproduction of potentially limiting factors that promote pre-IC formation results in increased replication from both efficient and inefficient origins, consistent with the hypothesis that competition among origins for these factors establishes origin efficiency.

Discussion

Our main results can be summarized as follows: 1) ORC binding to fission yeast origins is periodic in the cell cycle, rising during M and peaking at the M/G1 transition. Pre-RC formation is also periodic, rising and peaking in G1. 2) Compared to an early efficient origin (ori2004), ORC binding and pre-RC formation are delayed at a late inefficient origin (ori2060) and at a cryptic origin not used in it normal chromosomal context (ars727). 3) The extent of pre-IC formation at these three origins reflects the efficiency of their usage. 4) Decreasing ORC binding through removal of AT-hook motifs at ori2004 results in delays in pre-RC and pre-IC formation and delayed replication. 5) Delaying cells in M equalizes ORC binding and leads to changes in origin usage across the genome for many origins such that early efficient origins are utilized less efficiently, and some late inefficient origins are used more efficiently. 6) Overproduction of pre-IC factors Cdc45, Hsk1, or Dfp1 results in increased origin efficiency across the genome.

Peak ORC association with fission yeast origins at M/G1 is similar to the timing of ORC binding to origins in metazoa (DePamphilis, 2005). Our results contrast with conclusions from earlier studies in both budding and fission yeasts, which have reported an unchanging association of ORC with chromatin (Lygerou and Nurse, 1999) and origins (Aparicio et al., 1997; Ogawa et al., 1999). The differences between the present and earlier fission yeast results concerning origin binding are likely due to the increased temporal resolution and quantitative sensitivity of the experiments reported here. Using ChIP, we cannot exclude the possibility that a conformational change at the origin results in alterations in Orp1 ChIP signals. If this is the case, our results may reveal a specific event such as chromatin remodeling occurring at the origin during the M/G1 transition, prior to pre-RC formation. Our analysis also does not allow us to distinguish if all cells exhibit periodic ORC behavior at a given origin or if this occurs in a subpopulation of cells in which the origin is competent to fire.

Our work indicates that the timing of ORC and MCM binding during mitosis and G1 contributes to establishing the replication program during S. We show that pre-RCs are formed at origins regardless of their efficiencies, consistent with work from both budding and fission yeasts (Hayashi et al., 2007; Santocanale and Diffley, 1996), but that ORC binding and pre-RC formation are both delayed at a later firing origin. In contrast, no differences have been reported for MCM association with early and late firing origins in budding yeast (Aparicio et al., 1999). We also demonstrate that removal of AT-hook motifs in ori2004 which reduces ORC binding delays pre-RC and pre-IC formation as well as replication timing, suggesting that differences in affinity of origins for ORC during M play a role in the timing of origin firing during the S of the subsequent cell cycle.

We propose that delays in ORC and MCM binding during M and G1 lead to a non-equal association of Cdc45 and other replication factors among origins, thus establishing the replication timing program and determining the efficiency of origin usage. This can be understood if origins compete for a limited pool of replication factors such that origins at which ORC and pre-RC assemble late have a smaller number of these factors available to them. Consistently, we observe that the level of Cdc45 bound to an origin is closely related to origin efficiency; it should be noted that our results represent a population analysis and that Cdc45 may bind only to a subpopulation of active origins. Cdc45 has been suggested to be present in limiting quantities in human cells (Pollok et al., 2007), and the replication efficiency in Xenopus extracts correlates with the amount of Cdc45 on chromatin (Edwards et al., 2002). Moreover, a recent study using DNA combing has shown that Hsk1-Dfp1 in fission yeast regulates origin efficiency (Patel et al., 2008). Pre-IC formation at late origins may be restricted by decreasing levels of available factors as cells enter S and by passive replication through a region inactivating an origin so it cannot bind such factors. Therefore, the efficiency of an origin would be determined by both the timing of origin firing and its context in relation to other origins, with proximity to an early origin inactivating a late origin due to passive replication.

Our model proposes that the timing and therefore efficiency of origin firing are established by the recruitment of ORC to origins during M followed by competition among origins for limiting replication factors. ORC binding to origins may be determined by a combination of the primary sequence of an origin as well as its chromatin context. The timing of the increase in ORC binding during M and of pre-RC formation during G1 determines origin usage during the subsequent S. Our model could explain replication timing and efficiency as follows: ORC binding to early origins reaches a maximum at the exit of M, at which time ORC association with late origins is still low. At the beginning of G1, when MCM is competent to bind to origins, early origins have sufficient ORC to assemble a pre-RC, while late origins do not. Early origins with pre-RCs can then bind Cdc45 and other replication factors, which we suggest are present in limiting amounts. At late origins, ORC binding increases and reaches a maximum only later in G1, when they can then recruit MCMs. These origins complete pre-RC assembly toward the end of G1 and will be delayed for Cdc45 binding compared to early efficient origins, and it is this delay that results in a difference in replication timing. Late origins will also have a smaller pool of available Cdc45 for pre-IC formation, which decreases the likelihood of pre-IC formation and origin usage. Support for this model comes from our experiments prolonging M, which allows time for ORC to bind fully at more origins, reducing the differences in usage of many efficient and some inefficient origins. If ORC is limiting, as has been shown in budding yeast, then the equilibration of ORC binding may reflect a dynamic on-off process for ORC at origins during the prolonged M (Rowley et al., 1995). Alternatively, ORC may simply accumulate to a maximal level at both efficient and inefficient origins, allowing them to compete more equally for limiting replication factors. When mitosis is extended, a decrease in efficiency of many of the most frequently used origins is observed, while some inefficiently replicated regions become more active. Moreover, overproducing pre-IC factors Cdc45, Hsk1, or Dfp1 increases replication in both efficient and inefficient regions, suggesting that these proteins, among others, are limiting for replication.

The fact that we observe partial equilibration of origin efficiencies following MBC treatment may be due to the inaccessibility of an origin in its chromatin context. Certain regions of the fission yeast genome are generally repressed for origin activity, as reported by Heichinger et al. (2006) and Hayashi et al. (2006), and interestingly the MBC-induced origins identified in this study are mostly located outside these regions (Supp. Fig. 6). It is also possible that as some replication factors localize to nuclear foci (Meister et al., 2007), an origin may need to be positioned near a local pool for recruitment to occur. In addition, previous work investigating the program of origin firing in other organisms has implicated chromatin structure and histone modifications as important regulators. For example, acetylation status has been shown to change the pattern of origin firing, as deletion of the Rpd3 histone deacetylase in budding yeast results in increased histone acetylation and earlier firing of several origins (Aparicio et al., 2004; Vogelauer et al., 2002). These results are consistent with work in Drosophila follicle cells demonstrating that histones at active origins are hyperacetylated during the period of ORC binding and that RPD3 mutations result in redistribution of Orc2 in amplification stage cells (Aggarwal and Calvi, 2004). The timing of origin firing in fission yeast may likewise be regulated by chromatin modifications during the cell cycle, which modulate the affinity of an origin for ORC. In our experiments, delaying cells in mitosis may lead to a subset of late origins acquiring the same modifications as early origins, thus altering the origin firing program by allowing more equivalent binding of ORC.

Our work demonstrates that origin efficiency and timing in fission yeast are regulated by events that occur during mitosis of the previous cell cycle and suggests that competition for limiting factors by origins during G1 and S determines their activity. Support for aspects of this model comes from experiments in budding yeast where the late replication of origins at telomeres is established between mitosis and G1 (Raghuraman et al., 1997), in CHO cells where ORC binds chromatin during M/G1, and in mammalian nuclei introduced into Xenopus extracts where replication timing is established by early G1 (Dimitrova and Gilbert, 1999; Okuno et al., 2001). In human cells, time-lapse imaging studies have shown that Orc1 exhibits a distinctive localization pattern during G1 resembling the pattern of DNA replication that occurs during S (S. Prasanth and B. Stillman, unpublished results). Thus, it is possible that as in fission yeast, ORC binding and pre-RC assembly during M of the previous cell cycle and the G1 prior to S phase are key determinants for origin selection and the timing of origin firing in the cells of metazoan eukaryotes.

Materials and Methods

Strains and growth conditions

Standard media and methods were used (Hayles and Nurse, 1992; Moreno et al., 1991). Strains used in this study are listed in Supp. Table 1. cdc25-22 cells were synchronized by growing in minimal medium plus supplements (EMM4S) at 25°C to 1-2×106 cells/ml, shifting to 36.5°C for 4 hours to block cells in late G2, followed by release at 25°C. Samples for ChIP were taken every 10 minutes. For FACS, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol, and calcofluor staining was used to assess septation. Strains overexpressing cdc45, hsk1, and dfp1 from the nmt1 promoter were constructed by PCR integration (Bahler et al., 1998).

For MBC experiments, cells were synchronized using cdc25-22 at the restrictive temperature for 3 hours and 45 minutes. MBC was added at 50 μg/ml 10 minutes prior to the end of the arrest. For Figure 5A, cells were incubated with MBC after release to 25°C for the duration of the time course. For Figure 5B-E, cells were incubated with MBC at 25°C for 65 minutes before filtering and washing with EMM4S + 12 mM HU. Cultures were resuspended into EMM4S +12 mM HU + 300 mM BrdU to label newly synthesized DNA.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

ChIP was performed with some modifications to Martens and Winston (2002). Cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde and lysed in a FastPrep cell disruptor; extracts were sonicated using a Misonix microtip to ~300-400 bp DNA. The following antibodies were used: anti-HA (12CA5, 1 μl per IP), anti-MCM4 (1 μl per IP, Nishitani et al., 2000), and anti-GFP (1 μl per IP, gift of the Rout laboratory). For qPCR analysis, input DNA (at 1/100 dilution) and IP DNA were mixed with SYBR Green PCR mix (Applied Biosystems) and processed using an ABI 7900 or a Roche Lightcycler 480. The occupancy, or percent IP (%IP), was derived by relative quantification using the Ct or Cp values. % IP represents the ratio for a specific sequence of the amount of DNA associated with the immunoprecipitated protein to the total DNA used for the IP. For time course analysis, line graphs showing changes in % IP were hand-drawn. Sequences of PCR primers are listed in Supp. Fig. 7.

BrdU immunoprecipitation and array hybridizations

Cells were treated with 0.01% sodium azide and harvested by centrifugation. After washing with EDTA and TE, genomic DNA was prepared (Hoffman and Winston, 1987), purified using the Qiagen Genomic DNA kit, and sonicated to ~300-400 bp length. For IP, 4-5 μg DNA was mixed with 40 μl BrdU antibody (anti-mouse, BD Biosciences) followed Protein G beads (GE Healthcare). Washes and elution were performed according to the above ChIP protocol. For amplification, DNA was blunted using T4 DNA polymerase, followed by linker ligation and PCR amplification for 22 cycles and purification on a Qiagen PCR purification column (http://jura.wi.mit.edu/young_public/signaling/Protocols.html). 2 μg of DNA was fragmented to 50-100 bp in One-Phor-All Buffer Plus (GE Healthcare) using Genechip fragmentation reagent (Affymetrix) and biotin labeled using the BioArray Terminal Labeling Kit (Enzo Life Sciences) before hybridization to Affymetrix S. pombe tiling arrays.

Data Analysis

The tiling analysis software (TAS) package from Affymetrix was used to obtain linear signal intensity values. All poorly hybridized spots with values of 1.0 were removed from each dataset. Signal intensities from BrdU IPs for experimental samples were compared to control IPs using genomic DNA from cdc25-22 arrested cells by calculating the ratio of signal intensities for every spot with a value in both datasets. Smoothing of the dataset using the geometric mean was used over a window of 200 probes, or around 5 kb. The ratios were normalized to the median value of the smoothed dataset to provide a baseline for comparison among the different hybridizations. Three sets of experiments for mitotic HU replication efficiencies as well as MBC-HU treatment were performed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shah-an Yang for help with the bioinformatics analysis. We are grateful to Supriya Prasanth and Bruce Stillman for sharing unpublished data and to all the members of the Laboratory of Yeast Genetics and Cell Biology for critical reading of the manuscript. This study was supported by NIH Postdoctoral Fellowship GM075572, the Sydney and Stanley Shuman Postdoctoral Fellowship, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aggarwal BD, Calvi BR. Chromatin regulates origin activity in Drosophila follicle cells. Nature. 2004;430:372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature02694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aladjem MI. Replication in context: dynamic regulation of DNA replication patterns in metazoans. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:588–600. doi: 10.1038/nrg2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio JG, Viggiani CJ, Gibson DG, Aparicio OM. The Rpd3-Sin3 histone deacetylase regulates replication timing and enables intra-S origin control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4769–4780. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4769-4780.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio OM, Stout AM, Bell SP. Differential assembly of Cdc45p and DNA polymerases at early and late origins of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9130–9135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio OM, Weinstein DM, Bell SP. Components and dynamics of DNA replication complexes in S. cerevisiae: redistribution of MCM proteins and Cdc45p during S phase. Cell. 1997;91:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler J, Wu JQ, Longtine MS, Shah NG, McKenzie A, 3rd, Steever AB, Wach A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SP, Dutta A. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:333–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broach JR, Li YY, Feldman J, Jayaram M, Abraham J, Nasmyth KA, Hicks JB. Localization and sequence analysis of yeast origins of DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1983;47(Pt 2):1165–1173. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1983.047.01.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Kelly TJ. Purification of Hsk1, a minichromosome maintenance protein kinase from fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22083–22090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.22083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Chuang RY, Kelly TJ. DNA replication origins in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:337–342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408811102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePamphilis ML. Cell cycle dependent regulation of the origin recognition complex. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:70–79. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.1.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diffley JF. Eukaryotic DNA replication. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:368–372. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova DS, Gilbert DM. The spatial position and replication timing of chromosomal domains are both established in early G1 phase. Mol Cell. 1999;4:983–993. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MC, Tutter AV, Cvetic C, Gilbert CH, Prokhorova TA, Walter JC. MCM2-7 complexes bind chromatin in a distributed pattern surrounding the origin recognition complex in Xenopus egg extracts. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33049–33057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W, Collingwood D, Boeck ME, Fox LA, Alvino GM, Fangman WL, Raghuraman MK, Brewer BJ. Genomic mapping of single-stranded DNA in hydroxyurea-challenged yeasts identifies origins of replication. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:148–155. doi: 10.1038/ncb1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman KL, Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. Replication profile of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome VI. Genes Cells. 1997;2:667–678. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1520350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grallert B, Nurse P. The ORC1 homolog orp1 in fission yeast plays a key role in regulating onset of S phase. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2644–2654. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Katou Y, Itoh T, Tazumi A, Yamada Y, Takahashi T, Nakagawa T, Shirahige K, Masukata H. Genome-wide localization of pre-RC sites and identification of replication origins in fission yeast. Embo J. 2007;26:2821. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayles J, Nurse P. Genetics of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:373–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heichinger C, Penkett CJ, Bahler J, Nurse P. Genome-wide characterization of fission yeast DNA replication origins. Embo J. 2006;25:5171–5179. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman CS, Winston F. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;57:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyrien O, Mechali M. Plasmid replication in Xenopus eggs and egg extracts: a 2D gel electrophoretic analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1463–1469. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SM, Huberman JA. Regulation of replication timing in fission yeast. Embo J. 2001;20:6115–6126. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CJ, DePamphilis ML. Mammalian Orc1 protein is selectively released from chromatin and ubiquitinated during the S-to-M transition in the cell division cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:105–116. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.105-116.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas I, Palakodeti A, Jiang Y, Young DJ, Jiang N, Fernald AA, Le Beau MM. High-throughput mapping of origins of replication in human cells. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:770–777. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lygerou Z, Nurse P. The fission yeast origin recognition complex is constitutively associated with chromatin and is differentially modified through the cell cycle. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 21):3703–3712. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.21.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens JA, Winston F. Evidence that Swi/Snf directly represses transcription in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2231–2236. doi: 10.1101/gad.1009902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maundrell K, Hutchison A, Shall S. Sequence analysis of ARS elements in fission yeast. Embo J. 1988;7:2203–2209. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister P, Taddei A, Ponti A, Baldacci G, Gasser SM. Replication foci dynamics: replication patterns are modulated by S-phase checkpoint kinases in fission yeast. Embo J. 2007;26:1315–1326. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesner LD, Crawford EL, Hamlin JL. Isolating apparently pure libraries of replication origins from complex genomes. Mol Cell. 2006;21:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickle KL, Ramanathan S, Rosebrock A, Oliva A, Chaudari A, Yompakdee C, Scott D, Leatherwood J, Huberman JA. Checkpoint independence of most DNA replication origins in fission yeast. BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer SE, Lewis PW, Botchan MR. Isolation of the Cdc45/Mcm2-7/GINS (CMG) complex, a candidate for the eukaryotic DNA replication fork helicase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10236–10241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602400103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VQ, Co C, Li JJ. Cyclin-dependent kinases prevent DNA re-replication through multiple mechanisms. Nature. 2001;411:1068–1073. doi: 10.1038/35082600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani H, Lygerou Z, Nishimoto T, Nurse P. The Cdt1 protein is required to license DNA for replication in fission yeast. Nature. 2000;404:625–628. doi: 10.1038/35007110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Takahashi T, Masukata H. Association of fission yeast Orp1 and Mcm6 proteins with chromosomal replication origins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7228–7236. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno Y, McNairn AJ, den Elzen N, Pines J, Gilbert DM. Stability, chromatin association and functional activity of mammalian pre-replication complex proteins during the cell cycle. Embo J. 2001;20:4263–4277. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno Y, Okazaki T, Masukata H. Identification of a predominant replication origin in fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:530–537. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.3.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno Y, Satoh H, Sekiguchi M, Masukata H. Clustered adenine/thymine stretches are essential for function of a fission yeast replication origin. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6699–6709. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel PK, Arcangioli B, Baker SP, Bensimon A, Rhind N. DNA replication origins fire stochastically in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:308–316. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel PK, Kommajosyula N, Rosebrock A, Bensimon A, Leatherwood J, Bechhoefer J, Rhind N. The Hsk1(Cdc7) replication kinase regulates origin efficiency. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5550–5558. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollok S, Bauerschmidt C, Sanger J, Nasheuer HP, Grosse F. Human Cdc45 is a proliferation-associated antigen. Febs J. 2007;274:3669–3684. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poloumienko A, Dershowitz A, De J, Newlon CS. Completion of replication map of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome III. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3317–3327. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuraman MK, Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. Cell cycle-dependent establishment of a late replication program. Science. 1997;276:806–809. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remus D, Blanchette M, Rio DC, Botchan MR. CDK phosphorylation inhibits the DNA-binding and ATP-hydrolysis activities of the Drosophila origin recognition complex. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39740–39751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanowski P, Madine MA, Rowles A, Blow JJ, Laskey RA. The Xenopus origin recognition complex is essential for DNA replication and MCM binding to chromatin. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1416–1425. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00746-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley A, Cocker JH, Harwood J, Diffley JF. Initiation complex assembly at budding yeast replication origins begins with the recognition of a bipartite sequence by limiting amounts of the initiator, ORC. Embo J. 1995;14:2631–2641. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santocanale C, Diffley JF. ORC- and Cdc6-dependent complexes at active and inactive chromosomal replication origins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Embo J. 1996;15:6671–6679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomiya T, Ina S. Analysis of chromosomal replicons in early embryos of Drosophila melanogaster by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3935–3941. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchcomb DT, Struhl K, Davis RW. Isolation and characterisation of a yeast chromosomal replicator. Nature. 1979;282:39–43. doi: 10.1038/282039a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun WH, Coleman TR, DePamphilis ML. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the association between origin recognition proteins and somatic cell chromatin. Embo J. 2002;21:1437–1446. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Ohara E, Nishitani H, Masukata H. Multiple ORC-binding sites are required for efficient MCM loading and origin firing in fission yeast. Embo J. 2003;22:964–974. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelauer M, Rubbi L, Lucas I, Brewer BJ, Grunstein M. Histone acetylation regulates the time of replication origin firing. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1223–1233. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuuchi H, Yamada Y, Uchida T, Sunathvanichkul T, Nakagawa T, Masukata H. Ordered assembly of Sld3, GINS and Cdc45 is distinctly regulated by DDK and CDK for activation of replication origins. Embo J. 2006;25:4663–4674. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Hori Y, Shinomiya T, Obuse C, Tsurimoto T, Yoshikawa H, Shirahige K. The efficiency and timing of initiation of replication of multiple replicons of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome VI. Genes Cells. 1997;2:655–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1530351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, Stillman B. Assembly of a complex containing Cdc45p, replication protein A, and Mcm2p at replication origins controlled by S-phase cyclin-dependent kinases and Cdc7p-Dbf4p kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3086–3096. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3086-3096.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.