Abstract

Background & Aims

The neonatal receptor for immunoglobulin (Ig)G (FcRn) protects monomeric IgG from catabolism in parenchymal and hematopoietic cells. In dendritic cells, FcRn also promotes presentation of antigens in association with IgG. Since IgGs with anti-bacterial specificity are a hallmark of inflammatory bowel disease, we sought to determine their significance and relationship to FcRn expression in antigen presenting cells, focusing on IgGs specific for flagellin.

Methods

Levels of circulating anti-flagellin IgG were induced in wild-type and FcRn−/− mice, followed by induction of colitis with dextran sodium sulfate (DSS). Bone marrow chimera models were used to localize the site of FcRn action.

Results

Wild-type mice that received anti-flagellin IgG exhibited more severe colitis following administration of DSS, compared to mice that received control IgG. Wild-type mice immunized with flagellin exhibited significantly more severe colitis in response to DSS administration than that observed in similarly treated FcRn−/− mice. In chimera studies, FcRn−/− mice given wild-type bone marrow and immunized with flagellin exhibited significantly more colitis than wild-type mice given FcRn−/− bone marrow and immunized with flagellin. Serum anti-flagellin IgG levels were similar in both sets of chimeric mice, consistent with the equal participation of hematopoietic and non-hematopoeitic cells in FcRn-mediated IgG protection.

Conclusions

Anti-bacterial IgG antibodies are involved in the pathogenesis of colitis; this pathway requires FcRn in antigen presenting cells, the major subset of hematopoietic cells that express FcRn.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), the two major clinical forms of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), are chronic, immunologically mediated inflammatory disorders of the intestinal tract. Recent evidence indicates that IBD is caused by an inappropriate and dysregulated host immune response to the complex enteric microbiota in a genetically susceptible host.1 Evidence that the microbiota are the drivers of this aberrant immune response in humans comes from both the beneficial therapeutic effects of antibiotics in subsets of IBD patients2 and recent findings that genes associated with innate immune recognition (e.g. NOD2), the autophagic processing of bacteria (e.g. ATG16L1 and IRGM) and the sensitivity of the epithelium to bacterial products due to aberrant regulation of the unfolded protein response (e.g. XBP1) are risk factors for development of IBD.3-4 The importance of the commensal microbiota is more directly supported by studies in a variety of mouse models in which spontaneous chronic colitis is dependent upon the presence of bacteria and does not occur in the germ-free state.5-6 Although the specific microorganisms remain to be defined, an analysis of antibody and T cell responses in both humans and mouse models have shown that specific bacterial antigens are targets of the immune response. In Crohn’s disease, for example, IgG antibodies can be detected that are specific for distinct bacterial antigens such as flagellins primarily associated with Clostridia sp.7 and particular outer membrane proteins associated with Escherichia sp.8 Marked elevation of IgG antibodies specific for bacterial antigens is a characteristic hallmark of not only both human CD and UC but is also observed in many mouse models of intestinal inflammation.7, 9-12 In IBD, there is a switch from a mucosal immune system that is characterized by a predominance of IgA antibodies to one that is characterized by a predominance of plasma cells dedicated to IgG production.13 Such observations support the notion that in IBD a defective interplay exists between the mucosal immune system and the gut microbiota. However, the role that these IgG antibodies play in the pathogenesis of the intestinal inflammation associated with IBD has not been investigated.

One bacterial antigen to which IgG antibodies are directed in CD that is of particular interest is flagellin, a common bacterial antigen, that has been shown to be a dominant antigen in CD.7, 14 Flagellin is the principal structural component of bacterial flagella present in all motile bacteria, including a variety of commensal bacteria. Flagellin is a potent activator of the innate immune system through specific binding to the pattern recognition receptor Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5). Immune responses to flagellin, as represented by flagellin-specific IgG antibodies, are detected in approximately 50% of CD patients7 and elevated flagellin antibody levels are associated with a more severe disease phenotype.15 This latter association with clinical disease activity could be interpreted in one of several ways. One possibility is the IgG anti-flagellin antibodies are themselves pathogenic. Alternatively, such IgG antibody elevations may reflect a regulatory pathway that occurs in response to severe disease. We therefore hypothesized that an investigation of bacterial IgG anti-flagellin responses in a model of colitis that reflects the conditions associated with human IBD, a breakdown in the epithelial barrier in the context of chronically elevated anti-flagellin antibodies, might be a means to both understand the biologic function of anti-bacterial IgG antibodies characteristic of IBD but also the mechanism of action.

In these studies, we focused on the relationship between IgG anti-flagellin antibodies and the neonatal receptor for IgG, FcRn. FcRn is a major histocompatibility complex class I-related molecule that is expressed in adult life within parenchymal cells including hepatocytes, endothelia and epithelia of numerous mucosal surfaces including the intestines, and hematopoietic cells; specifically monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DC) and possibly B cells.16, 17 FcRn expression is developmentally regulated in a cellular and tissue specific fashion as shown by dramatic downregulation in intestinal epithelial cell expression in rodents (mouse and rats) but not most other mammalian species studied including humans. FcRn binds to the Fc domain of IgG at acidic pH (pH < 6.0) but not at neutral pH (pH > 7.0)18 and functions in the bidirectional transport of IgG across polarized epithelia19, 20 and a related cell biologic process that is associated with the protection of monomeric IgG from degradation.21 This occurs because FcRn diverts IgG from lysosomes in both parenchymal (e.g. endothelia) and hematopoietic cells thus protecting the latter from catabolism making FcRn responsible for the long serum half-life of IgG.22-24 In contrast, FcRn expressed within professional antigen presenting cells (APC) such as DC has recently been shown to play an important role in directing polymeric antigen-antibody complexes to lysosomes thereby promoting the processing and presentation of antigens contained within immune complexes.24

We therefore investigated whether or not IgG anti-flagellin antibodies were pathogenic in colitis and the role of FcRn as either a regulator of IgG half-life and/or antibody mediated antigen presentation which would be expected to facilitate adaptive immune functions and inflammation. To do so, we established a model in which we were able to gain temporal control of humoral immune responses to flagellin in order to mimic conditions that would be present in humans with IBD. Specifically, we conferred antigen specificity to the dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) mouse model of colitis which is typically driven by innate immune mechanisms. By immunizing mice to bacterial flagellin prior to DSS administration, we were able to confer high levels of anti-flagellin IgG antibodies and antigenic specificity to the immune response consequent to the disruption of the intestinal epithelial cell barrier. In this manner, we were able to show that IgG anti-bacterial (i.e. flagellin) antibodies are pathogenic but only in the presence of FcRn expression within hematopoietic cells.

Materials and Methods

Induction and evaluation of colitis

Seven to twelve-week-old female specific-pathogen-free C57Bl/6 mice or congenic Ly5.1+ C57Bl/6 (Jackson Laboratory) were studied with the approval of the animal facility at Harvard Medical School. FcRn−/− mice previously described22 were backcrossed 11 generations onto the C57Bl/6 background. The eGFP transgenic mice were kindly provided by Dr. Ulrich von Andrian, Harvard Medical School. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) (molecular weight 35,000–50,000, MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) solution (4%, wt/vol) was administered as drinking water for 7 days to induce acute colitis.

Severity of colitis was evaluated by body weight change and histological score. Total colon was removed and the distal 5 cm was used for routine histological evaluation of tissue damage, representative sections were microscopically evaluated by a pathologist in a blinded fashion according to the assessment system reported by ten Hove et al.25 For the detection of mouse CD11c, tissues were snap frozen and subjected to immunohistochemical staining using PE conjugated hamster anti-CD11c antibodies (BD Pharmingen) and examined by confocal microscopy (MRC1024 laser scanning confocal system).

Serum total IgG, anti-flagellin IgG and cytokine secretion ELISA

Total IgG levels in the serum were assessed by a sandwich ELISA as previously described20. Serum anti-flagellin IgG were assessed by ELISA coated with 500 ng/well of flagellin purified from Salmonella typhimurium (InvivoGen), detected with goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP conjugate (BD Pharmingen) and developed with tetramethylbenzidine substrate. Endpoint titers were expressed as the relative values compared to the standard serum used in all assays.

For cytokine ELISA, full thickness colonic tissue specimens were homogenized in PBS containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Mini-Complete; Roche). After centrifugation, total protein content of the supernatants was determined by the BCA protein assay (Pierce) and murine IL-12p70, IFN-γ, and IL-10 protein levels were determined using ELISA kits (BD Pharmingen).

Bone marrow chimera mice and rabbit IgG half-life study

Bone marrow chimera mice were created as previously described.24 In brief, six-week old mice were lethally irradiated (2 × 6 Gy) and reconstituted i.v. with 5×106 bone marrow cells. Eight weeks after reconstitution, chimerism was determined by flow cytometric evaluation of Ly5.1 and Ly5.2 expression and mice that were greater than 90% chimeric for the transferred bone marrow were administered 200 μg rabbit polyclonal IgG (Lampire) i.v.. The first blood samples were taken 2 h post transfer and thereafter daily. Sera were assayed with an ELISA specific for rabbit IgG.

Flagellin immunization and serum IgG enrichment

Wild-type CB57Bl/6, FcRn−/− or bone marrow chimeric mice were immunized with either flagellin, ovalbumin (OVA) or PBS subcutaneously in the presence of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA, Sigma) followed by a second immunization with the same antigen 14 days later. Fifty-six days after the first immunization mice were bled and IgG was purified from the serum with the Melon Gel IgG Purification Kit (Pierce).

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined by a 2-tailed Student’s t test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Flagellin specific IgG antibodies are induced during and after DSS colitis

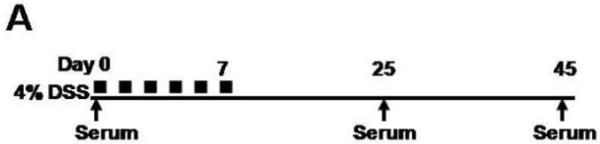

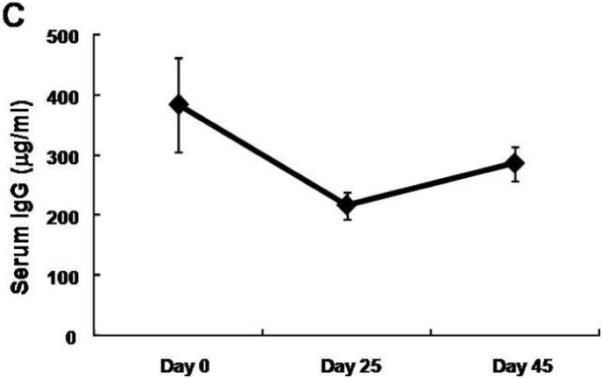

We first examined whether an IgG response to flagellin is observed in wild-type mice during the course of intestinal inflammation caused by DSS administration. We induced colitis in wild type C57Bl/6 mice with 4% DSS in drinking water for seven days, a condition that is known to cause epithelial damage, and monitored the development of flagellin-specific IgG antibodies (Fig. 1A). As shown in figure 1B, the serum flagellin-specific IgG levels, which were not detectable at baseline prior to inflammation, rose steadily from day 25 after the initiation of DSS colitis, until day 45 a time when the intestinal epithelial cell barrier is restored and inflammation ceases to exist.26 In comparison, during the course of active intestinal inflammation between day 0 and day 25, the total serum IgG levels decreased slightly, presumably due to extensive leakage into the intestinal lumen, with a return of the total IgG levels to baseline levels after the cessation of active inflammation between day 25 and day 45 (Fig. 1C). Thus, over time, an increasing fraction of the total IgG antibodies in mice exposed to DSS represent those with anti-flagellin and presumably other specificities that are directed at the endogenous commensal microbiota. Moreover, these anti-flagellin antibodies occur as a consequence of a single episode of intestinal inflammation with kinetics that is typical of a primary immune response. These studies support our hypothesis that invasion of bacterial antigens into the lamina propria due to compromise of the epithelial barrier, and subsequent immunological responses are accompanied by elicitation of specific IgG anti-bacterial antibodies.

Figure 1. Anti-Flagellin IgG is only detectable during the recovery phase of DSS colitis.

A. Overview of the experimental protocol. B. Serum anti-flagellin IgG levels measured by ELISA increased 25 and 45 days after a 7 day DSS exposure. C. Total serum IgG levels measured by ELISA decreased slightly during the same period. The average values of eight mice are shown and all error bars denote standard error of the mean.

Anti-flagellin IgG antibodies are pathogenic

Both the resolution phases of acute DSS colitis, as shown above, and human chronic IBD are characterized by the presence of circulating anti-flagellin and other bacterially directed IgG antibodies.7, 8, 15 We therefore sought to determine whether these bacterial antigen specific IgG antibodies protect against or promote the development of inflammation. Since anti-flagellin IgG antibodies are not present in wild-type mice prior to the DSS administration, we wished to confer to such mice anti-flagellin IgG antibody levels characteristic of mice previously exposed to DSS (as shown in Fig. 1B). As a source of anti-flagellin specific IgG antibodies, we used IgG antibodies harvested from wild-type C57Bl/6 mice having been hyperimmunized with bacterial flagellin purified from Samonella typhimurium.

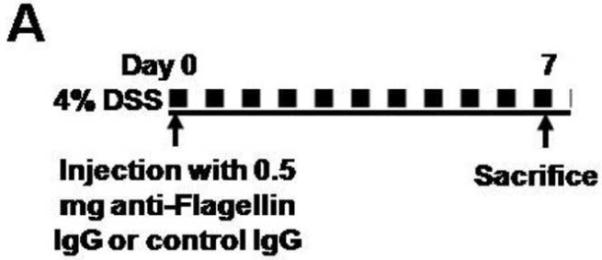

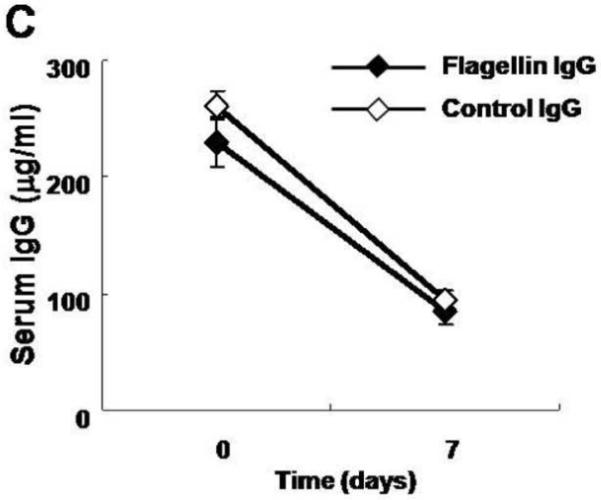

Wild-type mice were administered 0.5 milligrams of IgG derived from either flagellin immunized or non-immunized mice (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2B, by two hours after administration (day 0 time-point), mice that received IgG from hyperimmune mice achieved high serum levels of anti-flagellin IgG antibodies in contrast to mice that received IgG antibodies from nonimmunized animals. The total amount of IgG antibodies in the serum after the passive transfer was similar in both groups (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Anti-Flagellin IgG exacerbates colonic injury in DSS colitis.

A. Overview of the experimental protocol. Wild-type C57Bl6 mice were used. B. Serum anti-flagellin IgG level was detectable only in mice that received anti-flagellin IgG. C. Total serum IgG levels were similar in both groups of mice. D. Body weight loss was more pronounced in wild type mice that received anti-flagellin IgG (n=8) during DSS colitis compared to mice that received control IgG (n=7). E. Histological score of colonic tissue was higher in mice injected with anti-flagellin IgG. All error bars denote standard error of the mean and asterisk indicates P<0.05.

Both groups of mice were then administered 4% DSS in their drinking water for seven days and the development of colitis was monitored. Despite rapidly falling serum titers of flagellin IgG (Fig. 2B) due to a combination of normal IgG catabolism and colitis-induced intestinal leakage (Fig. 2C and data not shown), mice that received the flagellin-specific IgG antibodies experienced significantly more severe colitis as defined by weight loss (Fig. 2D) and significantly worse quantitative evidence of pathologic injury at day 7 of DSS exposure (Fig. 2E). These data show that passive administration of flagellin specific IgG to a naïve animal promotes the development of intestinal inflammation suggesting a pathogenic role for anti-bacterial IgG antibodies in experimental colitis.

FcRn deficient mice are protected from flagellin IgG mediated DSS colitis

The aforementioned studies show that if the intestinal epithelial cell barrier is breeched in the presence of high titer anti-flagellin IgG antibodies that the subsequent inflammation will be more severe. Such a scenario is typical of chronic colitis in human IBD wherein chronic elevated levels of IgG harboring anti-bacterial specificities including those that are directed at flagellin7 and other bacterial antigens are observed.10 We therefore sought to establish a mouse model system in which intestinal epithelial cell barrier disruption occurs in a host with concomitant and sustained high titer circulating anti-flagellin IgG antibodies.

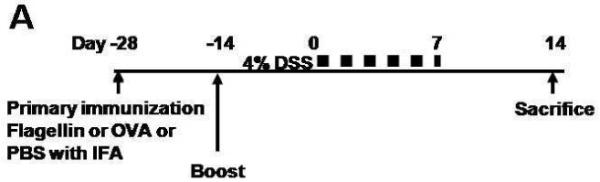

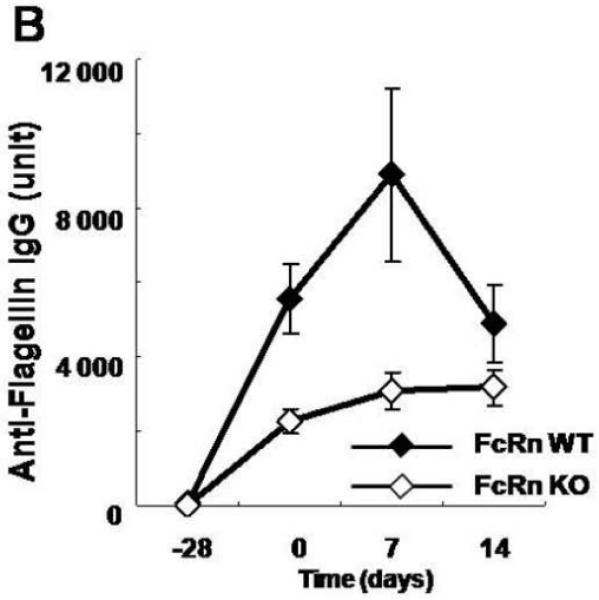

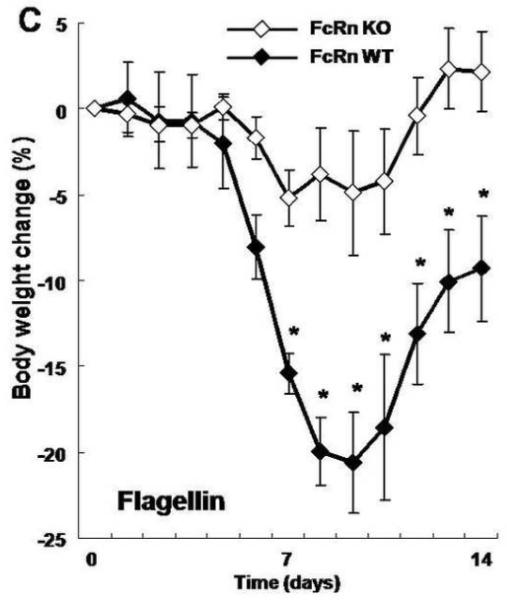

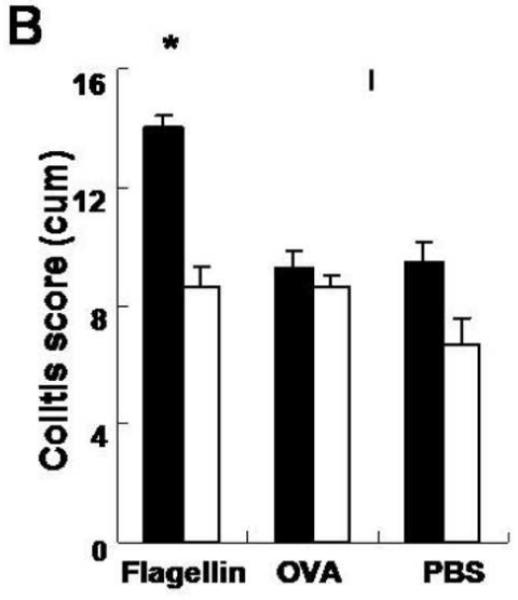

To do so, we conferred antigen specificity to the DSS colitis model. Specifically, as described schematically in Figure 3A, we hyperimmunized either wild-type CB57Bl/6 or FcRn−/− mice with two rounds of either flagellin, ovalbumin (OVA) or PBS subcutaneously. Based upon the kinetics of antibody formation observed in wild-type mice (Fig. 1B), one month after the initial immunization, we then administered 4% DSS in the drinking water to disrupt the epithelial barrier during a time when sensitization to flagellin and the development of anti-flagellin IgG antibodies had occurred and monitored the development of colitis. Consistent with prior studies (Figs. 1B and 2B), in the absence of immunization and / or intestinal inflammation, wild-type and FcRn−/− mice exhibited insignificant levels of anti-flagellin IgG antibodies in the serum (Fig 3B; −28 days). The immunization regime applied, however, resulted in robust flagellin specific serum IgG responses that lasted throughout the DSS colitis experiment and actually increased during the period of inflammation. This was in contrast to the rapid loss of anti-flagellin IgG observed during colitis after passive IgG transfer (Fig. 2B). Thus, in this experimental model, colitis occurred in the presence of very high anti-flagellin IgG antibody titers. It is important to note that after immunization, the anti-flagellin IgG levels in the FcRn−/− mice was significantly lower than that observed in the wild-type mice, in accordance with earlier reports showing decreased IgG responses in FcRn−/− animals upon immunization.22 Notably, however, these levels were still considerable and comparable with the maximum flagellin IgG levels observed after passive transfer (Fig. 2B). Despite this sustained high level of flagellin specific IgG antibodies in FcRn−/− mice, this group was protected from the exacerbation of DSS colitis observed in flagellin-hyperimmunized wild-type mice as demonstrated by less severe weight loss (Fig. 3C) and lower histological colitis score (Fig. 4A and 4B). Wild-type or FcRn−/− mice that were immunized with an irrelevant antigen, OVA (Fig. 4B and Fig. 3D), or those that received PBS (Fig. 4B and Fig. 3E), exhibited no differences in DSS colitis demonstrating that the exacerbation observed in wild-type mice was not caused by increased IgG levels in general or by adverse effects caused by the IFA. Taken together, these results show that exacerbation of DSS colitis in hyperimmunized animals is caused by flagellin specific IgG in a pathway that requires the presence of FcRn.

Figure 3. FcRn deficient mice are protected from flagellin IgG mediated DSS colitis.

A. Overview of the experimental protocol. B. After two rounds of flagellin immunization, serum anti-flagellin levels were increased in both wild type (n=8) and FcRn-deficient mice (n=8) during DSS colitis. C. Body weight loss was significantly more severe in wild type mice during DSS colitis. D. Body weight change was similar in wild type (n=6) and FcRn deficient mice (n=6) during DSS colitis after immunization with OVA. E. Body weight change was similar in wild type (n=6) and FcRn deficient mice (n=6) during DSS colitis after immunization with PBS. All error bars denote standard error of the mean and an asterisk indicates P<0.05.

Figure 4. Severity of DSS induced colitis is decreased in FcRn deficient mice.

A. Representative histology of wild type and FcRn-deficient mice on day 14 of the DSS colitis. B. Histological scores of colonic tissue on day 14 of the DSS exposure was evaluated in a blinded fashion by a pathologist. C. Histology of colitis lesion in KO→WT and WT→KO chimeras immunized with either flagellin or PBS. D. Histological score of the colonic tissue KO→WT (n=8, filled columns) and WT→KO (n=7, open columns) chimera immunized with either flagellin or PBS.

Colitis provoked by anti-flagellin specific IgG is mediated by FcRn expressed by myeloid cells

In the murine adult large intestine, FcRn expression is mainly limited to the lamina propria due to post-neonatal down-regulation of FcRn expression in rodent epithelial cells.27, 28 In the lamina propria, two major cell types express FcRn, endothelial cells and hematopoietic cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells that are both professional antigen presenting cells (APC). FcRn is not expressed by T cells or NK cells in either mouse or humans.23, 24, 29 Moreover, it has also been recently shown that FcRn in myeloid cells is functional and related to both the protection of monomeric IgG from catabolism23 and, oppositely, the degradation of multimeric IgG/antigen complexes and the promotion of antigen presentation.24 Thus, the protection from colitis that was observed in the FcRn−/− mice after immunization to flagellin in comparison to the wild-type mice could be due to either decreased flagellin specific IgG levels and their phlogistic properties per se secondary to increased IgG catabolism (and loss of monomeric IgG protection) and/or decreased antigen presentation normally mediated by IgG/flagellin complexes and thus a blunted inflammatory response. In order to distinguish between these two possibilities and to delineate whether FcRn-expressing hematopoietic or parenchymal cell types was responsible for the exacerbation of DSS colitis in the context of flagellin-specific IgG antibodies, we generated bone marrow chimeric mice.

As summarized in Table I, we established mice in which FcRn is expressed in both cells types (WT→WT), in APC only (WT→KO), in endothelial and other parenchymal cells only (KO→WT), or in neither cell types (KO→KO). Since FcRn expressed in parenchymal cells and bone marrow derived APC contribute approximately equally to the protection of IgG from catabolism23, 24, it would be predicted that IgG levels would be normal in WT→WT chimeras and markedly deficient in KO→KO chimeras (Table I). In contrast, whereas both WT→KO and KO→WT chimeras would exhibit similar but diminished IgG levels due to a loss of IgG protection in parenchymal (endothelial) and myeloid cells, respectively, only the KO→WT chimera would exhibit decreased FcRn-mediated antigen presentation (Table I). Thus, if IgG-dependent, FcRn-mediated antigen presentation was responsible for the development of DSS colitis after flagellin hyperimmunization as would be expected based on the protection from colitis observed in FcRn−/− mice (Fig. 3C) despite relatively high anti-flagellin antibody levels (Fig. 3B), it would be predicted that the colitis observed in the WT→KO chimeras would be greater than that observed in the KO→WT chimeras despite similar flagellin-specific IgG levels. (Table I)

Table I.

Expected expression of FcRn, IgG levels and experimental outcomes in the bone marrow chimeras

| FcRn in APC |

FcRn in parenchyma |

Serum IgG level |

Flagellin IgG / DSS colitis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KO→KO | − | − | + | − |

| KO→WT | − | + | ++ | + |

| WT→KO | + | − | ++ | +++ |

| WT→WT | + | + | +++ | +++ |

We first examined the fate of passively administered rabbit IgG to determine whether these bone marrow chimeras behaved as expected with respect to the catabolism of IgG. As shown in Fig. 5A, the serum half-lives of rabbit IgG was prolonged in WT→WT chimeras and markedly diminished in the KO→KO chimeras in agreement with previously published data.23, 24 In contrast, diminished but similar rates of IgG degradation were observed in the WT→KO and KO→WT chimeras. These studies show that the bone marrow chimeras behaved as predicted (Table I) and confirmed the importance of both the parenchyma and hematopoietic cells in determining the fate of IgG in the circulation.

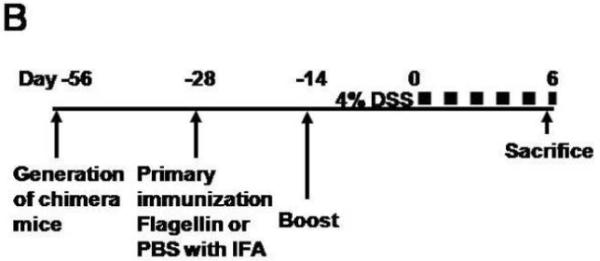

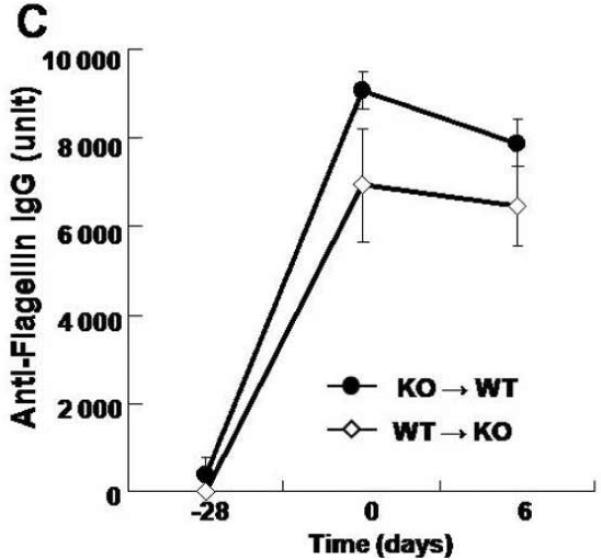

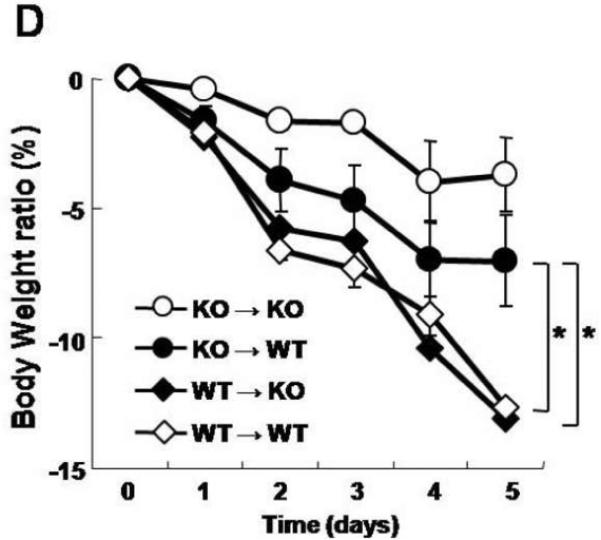

Figure 5. Colitis provoked by anti-flagellin specific IgG is mediated by FcRn expressed in myeloid cells.

A. Bone marrow chimeric mice were generated with wild-type and FcRn-deficient mice. Serum levels of the passively transferred rabbit IgG was followed daily in each group (n=4) by ELISA. B. Overview of the experimental protocol. C. The serum anti-flagellin IgG levels measured by ELISA were similar in FcRn KO→WT chimera (n=8) and WT→KO chimera (n=7). D. Body weight loss was significantly higher in WT→KO (n=7) and WT→WT (n=7) groups compared with the KO→WT (n=8) and KO→KO (n=4) groups during DSS colitis immunized with flagellin. E. The levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-12p70, IFN-γ and IL-10, expressed as pg per mg total protein, in colonic tissue homogenates of KO→WT (filled columns) and WT→KO chimera (open columns) were measured by ELISA. All error bars denote standard error of the mean and an asterisk indicates P<0.05.

We next pursued the same serums of flagellin immunizations in the bone marrow chimeras followed by DSS administration (Fig. 5B) to examine the role of IgG and/or FcRn in hematopoietic cells during the course of the colitis that is initiated by barrier disruption in the context of high circulating levels of anti-bacterial IgG antibodies. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, significant numbers of chimeric bone marrow derived CD11c-positive cells could be detected in lamina propria confirming successful reconstitution of this compartment. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 5C, both the WT→KO and KO→WT chimeras exhibited sustained high levels of flagellin-specific IgG antibodies 28 days after immunization and during the period of DSS. However, as measured by body weight changes, the colitis associated with DSS administration was significantly more severe in the WT→KO group, which contained FcRn in hematopoietic but not parenchymal cells, compared to that observed in the KO→WT group (Fig. 5D) despite similar levels of flagellin specific IgG (Fig. 5C). Such differences between the WT→KO and KO→WT chimeras were confirmed by macroscopic (Fig. 4C) and quantitative microscopic evaluation (Fig. 4D) and assessment of inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 5E). This latter evaluation showed a significant increase in IL12-p70 expression but not IFN-γ or IL-10, suggesting hematopoietic cell activation in the WT→KO chimeras in comparison to the KO→WT chimeras. In fact, the severity of the colitis that was observed in the WT→KO group wherein FcRn expression was limited to the hematopoeitic cells was similar to that observed in the WT→WT chimera. Thus, the severe colitis that was observed occurred independently of FcRn expression in parenchymal cells. The differences observed between the various groups of chimeras were absent in PBS control groups that received IFA only (data not shown). These results show that flagellin specific IgG is pathogenic but only in the presence of FcRn expression within hematopoietic cells.

Discussion

The biologic meaning of the increase of IgG antibodies that are directed against commensal bacteria antigens in human IBD has been largely unknown. By focusing on IgG responses to flagellin antigen, a dominant commensal antigen in CD, we now show that when the intestinal epithelial cell barrier is disrupted in the presence of these antibodies, as would be predicted to occur in IBD, inflammation is enhanced, and not down-regulated as would be predicted by a regulatory pathway. Moreover, our studies reveal that the IgG anti-flagellin antibodies are not directly pathogenic in and of themselves but rather that their pathogenicity derives from their ability to interact with FcRn within antigen presenting cells (APC) since these are the major subsets of hematopoietic cells that express FcRn.23, 29 This not only pinpoints IgG antibodies against bacterial antigens as being important mediators of IBD but predicts that they largely do so by their ability to activate hematopoietic cells through expression of FcRn as shown by increases of IL-12p70 and/or promotion of bacterial antigen presentation. Given that FcRn expression within hematopoietic cells is restricted to professional APC, it is likely that these subsets of cells are mainly responsible for these observed effects. In addition, we have recently observed that FcRn within dendritic cells functions in antigen presentation by directing antigen-antibody complexes into lysosomes wherein antigen processing and presentation to T cells is enhanced.24 Whether this occurs through an association between invariant chain and FcRn as recently described30 remains to be determined but is consistent with FcRn’s involvement in antigen presentation. It is therefore likely that the interaction of IgG antibodies presumably as immune complexes with flagellin also enhance antigen presentation and adaptive immune functions as a means to promote inflammation. Consistent with this, in other studies, we have observed that IgG antibodies to commensal bacterial antigens derived from Escherichia coli within the intestinal lumen can drive adaptive immune responses using ovalbumin as the nominal antigen through expression in E. coli.28 It remains to be defined whether IgG anti-bacterial antibodies enhance inflammation strictly through direct FcRn-mediated activation of APC, through trans-signaling from T cells as a consequence of FcRn-facilitated antigen presentation and/or through activation of T cells leading to pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion.

These studies have a number of implications for understanding the role of IgG antibodies, FcRn and anti-flagellin immune responses and their relationship with IBD. It can be predicted that diminishing anti-bacterial IgG antibody levels by targeting FcRn will be therapeutically beneficial in IBD. Since FcRn plays a major role in establishing the steady-state half-life of monomeric IgG by diverting these away from lysosomes and into a recycling pathway that allows IgG antibodies to avoid degradation within both parenchymal cells such as the endothelium and hematopoietic cells themselves23, 24, factors that disrupt this relationship between IgG and FcRn would be expected to diminish IgG antibodies and their ability to drive APC activation and antigen presentation. Therapy with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) blocks circulating IgG interactions with FcRn as one of its mechanisms of action31 and has shown some limited efficacy in both DSS colitis in rodents32 and uncontrolled human clinical studies in patients with IBD.33 Our studies further indicate that the beneficial effects of IVIG in DSS colitis are likely to involve blockade of anti-bacterial IgG interactions with FcRn in APC as shown here. Other means to block FcRn include anti-FcRn antibodies34, antibodies that are engineered to bind FcRn with high, pH independent affinity (so-called “Abdegs”35) or novel cyclic peptides with high affinity for FcRn.36 Therapeutic blockade of FcRn would be predicted to ameliorate IBD by causing decreased IgG anti-bacterial (flagellin) antibody levels as well as diminish immune-complex dependent antigen presentation by APC that is mediated by FcRn as shown by our bone marrow chimera experiments.

Our studies also have some interesting implications for understanding the role of anti-flagella responses that are observed in CD. Flagella represent a major group of antigens that are present in numerous bacterial strains that normally colonize the gastrointestinal tract. Flagellin, the major component structure of flagella, is a highly conserved molecule that potently interacts with both the innate and the adaptive immune system. Flagellin is detected in the host by a specific pattern recognition receptor, Toll like receptor 5 (TLR5) that is prominently expressed on the basolateral surface of polarized gut epithelia.37 Given this basolateral localization, flagellated commensal bacteria would not normally be expected to activate this receptor in the presence of a functional intestinal epithelial barrier. In contrast to other TLR agonists, flagellin does not seem to be a potent activator of classical antigen presenting cells and TLR5-deficient mice exhibit increased colitis suggesting that innate immune receptor engagement by flagellin is protective in IBD.38 On the other hand, flagellin is also a major target of the immune response that characterizes human IBD. Specifically, IgG anti-flagella antibodies, as well as other bacterially directed IgG antibodies, have recently been shown to be associated with CD.7,14 This is consistent with the concept that a loss of tolerance to the commensal bacteria and to flagellin in particular exists in human IBD as manifest by a switch from an IgA to an IgG-predominant response. However, the role of bacterial antigen-specific IgG antibodies in the pathogenesis of IBD has so far been unknown as noted. In the present study, we now show that the presence of flagellin-specific IgG during inflammation derived from DSS-provoked breakdown of the intestinal epithelial cell barrier significantly exacerbates the DSS-induced colitis in a pathway that involves IgG through its ability to interact with FcRn within APC, the major FcRn-bearing subset of hematopoietic cells. Given previous observations24, we hypothesize that this is due to the ability of FcRn in dendritic cells to enhance IgG-mediated antigen presentation as discussed further below.

To show the latter, we modified the DSS colitis model to possess antigen specificity for flagellin. Transient colitis in susceptible murine strains induced by the administration of DSS in drinking water is a useful model for human IBD.1 The primary function of DSS is the disruption of the intestinal epithelial cell barrier, leading to the exposure of immune cells, especially myeloid cells, residing in the lamina propria to luminal bacterial antigens.1 As such, the DSS colitis model has largely been applied as a model of innate immunity and consistent with this DSS can induce inflammation in RAG-deficient and Scid mice.39 The subsequent immune responses that are mounted against the bacterial antigens result in a clinical and histological colitis that resembles human IBD. However, this animal model has several shortcomings. In contrast to the chronic features of human IBD, the DSS colitis model when applied as a single course is transient, with an acute inflammatory phase that lasts only a few weeks followed by a complete recovery. In addition, DSS colitis does not model the role of the humoral components of the response as typically manifest in human IBD by elevated IgG antibody responses to bacterial antigens such as flagella.7 In the current studies, we observed that flagella-specific IgG was not detectable before and during the induction of DSS colitis, but appeared during the recovery phase at approximately three weeks after DSS exposure. To assign antigen specificity to the DSS model and allow for an evaluation of the humoral component of the immune response in colitis pathogenesis, we modified this model to include an adaptive component that was directed against flagellin. This allowed for an evaluation of the effects of IgG anti-flagellin antibodies when the intestinal epithelial cell barrier was disrupted; the situation typical of IBD in humans. We accomplished this by passive or active immunization against flagellar antigens prior to DSS-exposure. In either case, WT mice that had detectable levels of anti-flagellin IgG at the time of DSS induction exhibited significantly worsened clinical and pathological colitis. Such a modification of the DSS colitis model as applied here should be useful to others assessing responses to other potentially IBD-associated antigens.

DSS colitis studies in bone marrow chimera mice showed that despite comparable flagellin IgG levels, mice expressing FcRn in myeloid cells but deficient in FcRn expression in endothelial and epithelial cells (WT→KO group) exhibited more severe DSS-colitis compared to mice lacking FcRn expression in myeloid cells but having normal FcRn levels in endothelial and epithelial cells (KO→WT group). Previous studies have shown that transgenic over-expression of FcRn in mouse intestinal epithelial cells to model humans which express significant FcRn within intestinal epithelial cells in adult life19, 40 results in trans-epithelial transport of IgG, such that circulatory IgG can be first transported into the gut lumen and later trafficked back to the basolateral side bound with luminal (bacterial) antigens.27 Indeed, in these studies it has been shown that FcRn can mediate the transport of commensal bacterial antigens derived from E. coli and pathogenic bacterial antigens derived from Citrobacter rodentium across the epithelial cell.28 However, in non-genetically manipulated adult WT mice, the expression levels of FcRn in intestinal epithelial cells is exceedingly low due to a striking down-regulation of FcRn expression at the end of the neonatal period.27 Thus, FcRn mediated antigen retrieval is not likely to be an important mechanism for the observed pathogenic effects of flagellin-specific IgG in the DSS colitis model as applied here. The fact that the body weight loss was equally severe in bone marrow chimera groups with similar FcRn expression in hematopoietic cells but disparate FcRn expression in the parenchymal cells (compare WT→KO with WT→WT groups) supports this notion. Our colitis data in bone marrow chimera mice rather indicates that the pathogenic effect of flagellin-specific IgG is mediated by the specific expression of FcRn in bone marrow derived cells. Earlier studies have shown that myeloid cells such as dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages, but not T and B cells, are the only cells within the hematopoietic lineage that express FcRn23, 24, 29; although recent studies suggest that human B cells may express FcRn.17 A recent study has shown that FcRn expressed in dendritic cells plays a crucial role in lysosomal trafficking and antigen presentation of IgG-antigen immune-complexes.24 While we did not identify the specific subset of DCs responsible for the observed effect, the specific FcRn-mediated enhancement of processing and presentation of immune complex delivered antigen within this cell population is likely to be the main mechanism responsible for the pathogenic effect of flagellin-specific IgG in DSS colitis in our model.

In the current work, we showed by transfer of anti-flagellin enriched IgG that flagellin-specific IgG antibodies were by themselves pathogenic, in the absence of pre-activated flagellin-specific T cells. Given the anti-inflammatory effect of flagellin engagement to the innate receptor TLR5 38, it is conceivable that anti-flagellin antibodies could aggravate disease by sequestering flagellin and thus interfering with the down-regulatory effects of this bacterial antigen. However, the fact that FcRn-deficient mice were largely protected from colitis exacerbation despite high levels of anti-flagellin IgG, points to interference with the adaptive immune response as the most likely mechanism by which anti-flagellin IgG antibodies promotes inflammation. Earlier studies have found normal T cells responses upon immunization in FcRn-deficient mice 22, nevertheless, these mice were largely protected from anti-flagellin IgG mediated colitis exacerbation despite presumably normal flagellin-specific T cell responses elicited by active flagellin immunization. These results suggest that the presence of flagellin-specific T cells alone is not sufficient to elicit pathological inflammatory responses. Flagellin-specific T cells, and possibly other T cells with anti-bacterial specificities, require adequate (re-)activation by efficient APC activation and antigen presentation which requires FcRn-mediated antigen presentation of immune-complexes containing anti-flagellin IgG antibodies.

In summary, we have shown that the IgG response to a model commensal bacterial antigen, flagellin, that characterizes human IBD plays a pathogenic role in a pathway that is strictly dependent upon the disruption of the intestinal epithelial cell barrier and exposure to bacterial antigen, bacterial antigen specific IgG and FcRn within bone marrow derived cells. These studies not only resolve a long-term conundrum on the role of bacterially directed IgG responses, but pinpoint IgG and FcRn as important therapeutic targets in the treatment of IBD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Lian-Ee Ch’ng for assistance in preparation of the manuscript. R.S.B. and W.I.L. were supported by NIH DK53056 and the Harvard Digestive Diseases Center (DK034854). R.S.B. was supported by NIH DK44319 and DK51362. W.I.L. was supported by Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

Grant Support

R.S.B. and W.I.L. were supported by NIH DK53056 and the Harvard Digestive Diseases Center (DK034854). R.S.B. was supported by NIH DK44319 and DK51362. W.I.L. was supported by Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- CD

Crohn’s Disease

- DC

dendritic cell

- DSS

dextran sodium sulfate

- FcRn

neonatal Fc receptor

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IFA

incomplete Freund’s adjuvant

- KO

FcRn knockout

- OVA

ovalbumin

- UC

ulcerative colitis

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Strober W, Fuss IJ, Blumberg RS. The immunology of mucosal models of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:495–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutherland L, Singleton J, Sessions J, et al. Double blind, placebo controlled trial of metronidazole in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1991;32:1071–1075. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.9.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho JH. The genetics and immunopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:458–466. doi: 10.1038/nri2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134:743–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onderdonk AB, Hermos JA, Bartlett JG. The role of the intestinal microflora in experimental colitis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:1819–1825. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.11.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elson CO, Cong Y, McCracken VJ, et al. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease reveal innate, adaptive, and regulatory mechanisms of host dialogue with the microbiota. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:260–276. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lodes MJ, Cong Y, Elson CO, et al. Bacterial flagellin is a dominant antigen in Crohn disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1296–1306. doi: 10.1172/JCI20295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landers CJ, Cohavy O, Misra R, et al. Selected loss of tolerance evidenced by Crohn’s disease-associated immune responses to auto- and microbial antigens. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:689–699. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDermott RP, Nash GS, Bertovich MJ, et al. Alterations of IgM, IgG, and IgA Synthesis and secretion by peripheral blood and intestinal mononuclear cells from patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:844–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Standaert-Vitse A, Branche J, et al. IBD serological panels: facts and perspectives. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1561–1566. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Tonegawa S, et al. Alteration of a polyclonal to an oligoclonal immune response to cecal aerobic bacterial antigens in TCRα mutant mice with inflammatory bowel disease. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1387–1394. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.9.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandwein SL, McCabe RP, Cong Y, et al. Spontaneously colitic C3H/HeJBir mice demonstrate selective antibody reactivity to antigens of the enteric bacterial flora. J Immunol. 1997;159:44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandtzaeg P, Halstensen TS, Kett K, et al. Immunobiology and immunopathology of human gut mucosa: humoral immunity and intraepithelial lymphocytes. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1562–1584. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sitaraman SV, Klapproth JM, Moore DA, III, et al. Elevated flagellin-specific immunoglobulins in Crohn’s disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G403–G406. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00357.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Targan SR, Landers CJ, Yang H, et al. Antibodies to CBir1 flagellin define a unique response that is associated independently with complicated Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:2020–2028. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mi W, Wanjie S, Lo ST, et al. Targeting the neonatal Fc receptor for antigen delivery using engineered Fc fragments. J Immunol. 2008;181:7550–7561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodewald R. pH-dependent binding of immunoglobulins to intestinal cells of the neonatal rat. J Cell Biol. 1976;71:666–669. doi: 10.1083/jcb.71.2.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickinson BL, Badizadegan K, Wu Z, et al. Bidirectional FcRn-dependent IgG transport in a polarized human intestinal epithelial cell line. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:903–911. doi: 10.1172/JCI6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida M, Claypool SM, Wagner JS, et al. Human neonatal Fc receptor mediates transport of IgG into luminal secretions for delivery of antigens to mucosal dendritic cells. Immunity. 2004;20:769–783. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junghans RP, Anderson CL. The protection receptor for IgG catabolism is the beta 2-microglobulin-containing neonatal intestinal transport receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5512–5516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roopenian DC, Christianson GJ, Sproule TJ, et al. The MHC class I-like IgG receptor controls perinatal IgG transport, IgG homeostasis, and fate of IgG-Fc-coupled drugs. J Immunol. 2003;170:3528–3533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akilesh S, Christianson GJ, Roopenian DC, et al. Neonatal FcR expression in bone marrow-derives cells functions to protect serum IgG from catabolism. J Immunol. 2007;179:4580–4588. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiao SW, Kobayashi K, Johansen FE, et al. Dependence of antibody-mediated presentation of antigen on FcRn. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9337–9342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ten Hove T, van den Blink B, Pronk I, et al. Dichotomal role of inhibition of p38 MAPK with SB 203580 in experimental colitis. Gut. 2002;50:507–512. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuchiya T, Fukuda S, Hamada H, et al. Role of γδT Cells in the inflammatory response of experimental colitis mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:5507–5513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simister NE, Mostov KE. An Fc receptor structurally related to MHC class I antigens. Nature. 1989;337:184–187. doi: 10.1038/337184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida M, Kobayashi K, Kuo TT, et al. Neonatal Fc receptor for IgG regulates mucosal immune responses to luminal bacteria. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2142–2151. doi: 10.1172/JCI27821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, Meng G, Dickinson BL, et al. MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor for IgG is functionally expressed in monocytes, intestinal macrophages, and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:3266–3276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye L, Liu X, Rout SN, et al. The MHC class II-associated invariant chain interacts with the neonatal Fcγ receptor and modulates its trafficking to endosomal/lysosomal compartments. J Immunol. 2008;181:2572–2585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akilesh S, Petkova S, Sproule TJ, et al. The MHC class I-like Fc receptor promotes humorally mediated autoimmune disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1328–1333. doi: 10.1172/JCI18838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shintani N, Nakajima T, Nakakubo H, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment of experimental colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium in rats. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;108:340–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-1021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine DS, Fischer SH, Christie DL, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for active, extensive, and medically refractory idiopathic ulcerative or Crohn’s colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu L, Garcia AM, Santoro H, et al. Amelioration of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis in rats by neonatal FcR blockade. J Immunol. 2007;178:5390–5398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ober RJ, et al. Engineering the Fc region of immunoglobulin G to modulate in vivo antibody levels. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1283–1288. doi: 10.1038/nbt1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mezo AR, McDonnell KA, Hehir CA, et al. Reduction of IgG in nonhuman primates by a peptide antagonist of the neonatal Fc receptor FcRn. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2337–2342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708960105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhee SH, Im E, Riegler M, et al. Pathophysiological role of Toll-like receptor 5 engagement by bacterial flagellin in colonic inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13610–13615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502174102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vijay-Kumar M, Sanders CJ, Taylor RT, et al. Deletion of TLR5 results in spontaneous colitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3909–3921. doi: 10.1172/JCI33084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Axelsson LG, Landstrom E, Goldschmidt TJ, et al. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) induced experimental colitis in immunodeficient mice: effects in CD4+-cell depleted, athymic and NK-cell depleted SCID mice. Inflamm Res. 1996;45:181–191. doi: 10.1007/BF02285159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Israel EJ, Taylor S, Wu Z, et al. Expression of the neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, on human intestinal epithelial cells. Immunology. 1997;92:69–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.