Abstract

The genetics of gene expression in recombinant inbred lines (RILs) can be mapped as expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs). So-called “genetical genomics” studies have identified locally-acting eQTLs (cis-eQTLs) for genes that show differences in steady state RNA levels. These studies have also identified distantly-acting master-modulatory trans-eQTLs that regulate tens or hundreds of transcripts (hotspots or transbands). We expand on these studies by performing genetical genomics experiments in two environments in order to identify trans-eQTL that might be regulated by developmental exposure to the neurotoxin lead. Flies from each of 75 RIL were raised from eggs to adults on either control food (made with 250 µM sodium acetate), or lead-treated food (made with 250 µM lead acetate, PbAc). RNA expression analyses of whole adult male flies (5–10 days old) were performed with Affymetrix DrosII whole genome arrays (18,952 probesets). Among the 1,389 genes with cis-eQTL, there were 405 genes unique to control flies and 544 genes unique to lead-treated ones (440 genes had the same cis-eQTLs in both samples). There are 2,396 genes with trans-eQTL which mapped to 12 major transbands with greater than 95 genes. Permutation analyses of the strain labels but not the expression data suggests that the total number of eQTL and the number of transbands are more important criteria for validation than the size of the transband. Two transbands, one located on the 2nd chromosome and one on the 3rd chromosome, co-regulate 33 lead-induced genes, many of which are involved in neurodevelopmental processes. For these 33 genes, rather than allelic variation at one locus exerting differential effects in two environments, we found that variation at two different loci are required for optimal effects on lead-induced expression.

Keywords: QTL, expression profiling, microarray, heavy metals, toxicogenomics

Introduction

Removal of lead from paint and gasoline has substantially reduced blood lead levels in the United States, but lead exposure still remains a serious public health problem [116]. Even if blood lead levels in children are below the current community action level (10 µg/dL), chronic lead exposure can impair cognitive function (e.g., [29,61,67,79,84,105,108,116]) and increase the likelihood of delinquency [34].

Chronic lead exposure has developmental and behavioral effects in both vertebrate and invertebrate animals. Among its effects are changes in motor activity levels in rhesus monkeys [68], rats [109] and Drosophila [50] and impairments in learning and memory in tadpoles [106], mice [107] and rats [3,43,59,81,82]. Despite considerable progress in understanding the physiological mechanisms of how lead affects neuronal plasticity during development [16,76,111] and in the adult [45,100,113,116], the genetic mechanisms lead disturbs are not well understood.

We thus decided to develop Drosophila melanogaster as a model for study of the behavioral, physiological and genetic effects of chronic lead exposure during development. Drosophila take up lead from the nutrient medium they are reared on [26] and the dose response curve for the lead body burden has a significant linear component [50]. As is the case for vertebrates, lead is toxic in Drosophila (larval LC50 (+/− standard error): 6.60 +/− 0.64 mM PbAc added to medium) and delays pre-adult development (lowest concentration extending larval development, 1.2 mM PbAc) without changing adult body weight [2]. Lead-dependent behavioral changes have been harder to demonstrate in Drosophila. An early study reported that, even at a high dose (3.07 mM PbAc), phototaxis, locomotion and learning are unaffected [2]. In sharp contrast, at very much lower doses courtship behavior (which is influenced by experience during the first few days of adult life [9,51,52]) shows biphasic lead-dependent changes: facilitation at low (10 and 40µM PbAc) doses and inhibition at higher (100 and 250 µM PbAc) ones [50]. Locomotor activity is also affected, but only at higher (250 µM PbAc) doses, and then only for males [50]. Furthermore, as is the case for mammals [17,27,28,64,80,94,111,116], lead affects synaptic development in Drosophila (100 µM PbAc; [83]). Recent evidence suggests that these synaptic effects may involve lead-dependent changes in calcium regulation (G. Lnenicka and D.M.R., submitted to Neurotoxicology). Finally, QTL analysis using the recombinant inbred lines (RILs) identified a site for lead-dependent changes in locomotor activity [53].

Toxicogenomic or pharmacogenomic studies generally involve administering various doses of a toxin or drug to an organism or cell line, and then measuring changes in expression of all, or nearly all genes using microarrays at either a single end point or as a time series (reviewed in [41]). If two compounds produce similar patterns of changed gene expression, they are said to have similar “fingerprints” suggesting that they function in a similar manner, for instance in a cell line [25] or in yeast [92]. As the cost of whole genome microarrays and other technologies to measure global gene expression levels has dropped, use of these approaches has become widespread. However, because they often identify toxin-dependent changes in expression for hundreds or even thousands of genes, it is difficult if not impossible to take the next step and validate all the results through follow-up genetic or molecular studies.

What is needed is an approach that reduces to a more manageable level the number of candidate toxin-regulated genes. Fortunately, a new multi-dimensional strategy, “genetical genomics,” has recently been developed to identify master modulatory loci that regulate the expression of dozens or hundreds of other genes [14,30,58,71,98]. Genetical genomics combines two methodologies: microarray-based whole transcriptome analyses and extracting quantitative trait loci (QTLs) using recombinant inbred lines (RILs) (see WebQTL at http://www.genenetwork.org for several examples of eQTL studies). Global gene expression levels are determined for each recombinant inbred line, and then QTL software (e.g ., R/QTL, [15]) is used to look for statistical association between specific chromosomal loci and transcript levels for all the genes. With this approach, regulation of many genes in an organism is linked by the QTL analysis to specific chromosomal loci, termed expression QTLs (eQTLs). The eQTLs affecting a gene’s steady-state mRNA levels can either be closely linked (cis-eQTLs) or unlinked, even on a different chromosome (trans-eQTLs) [14].

Drosophila has a number of features that are desirable in genetical genomic studies using multicellular organisms. First, the Drosophila genome (~125 Mbp; ~662 cM) is about one tenth the size of the rat or mouse genome, which would simplify re-sequencing large numbers of strains to identify quantitative trait nucleotides, and there is a wide array of genetic tools that allow one to quickly map and knock out the genes identified as eQTL peaks in flies [87]. Also, Drosophila recombinant inbred lines (RILs) are available that were made by mapping roo transposons in recombinants of two highly divergent parental strains, Oregon R (ORE) and Russian 2b (2B) [85]. While the C. elegans genome is even smaller, in C. elegans, organs are often present as multi-nucleated syncytia. In addition, they lack some epithelial properties and signaling pathways found in Drosophila and vertebrates, including humans [21,96]. Also, the entire C. elegans nervous system consists of just 302 identifiable neurons with all neuronal connections known (e.g ., [117]). Drosophila, on the other hand, shares important features with mammals including epithelial properties and a central nervous system that more closely resembles those of mammals. For example, the Drosophila brain consists of ~500,000 neurons [10] whose synaptic connections involve proteins that are highly conserved with those found in vertebrates [65] and, as in humans, the developing nervous system is affected by early experience [8,112].

We found that by using the new genetical toxicogenomic approach we could identify candidate regulatory loci underlying lead toxicity. Surprisingly, we identified a small number of trans-eQTLs, each of which apparently influences the expression of a large number of other genes in a lead-dependent manner. The eventual identification of lead-dependent master-modulatory genes will be profoundly important in deepening our understanding of the developmental and physiological consequences of lead exposure.

Results

Lead Alters the Regulation of cis-eQTLs and trans-eQTLs

We performed gene expression analyses of 18,952 probesets (using Affymetrix Dros2 gene expression arrays) in adult male Drosophila from 75 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) that were mapped with 82 polymorphic markers between the two parental strains, Oregon R (ORE) and Russian 2B (2B). The 18,952 probesets correspond to ~14,000 genes that have been validated in the latest genome browser and ~5,000 candidate regions that have not been validated as expressed genes. To avoid confusion, unless we are discussing a specific gene or genes, we will refer to the expression of probesets rather than genes because not all probesets correspond to validated genes. Expression analyses were performed from each RIL in the presence or absence of developmental and adult exposure to 250 µM lead acetate (see Materials and Methods; Supplementary Table S1 has the expression data for all for all 18,952 probesets for all 150 conditions).

We identified a total of 1,389 different probesets with cis-eQTL (i.e., within a 5 cM window; 0-to-4.99 cM, 5–9,99 cM, etc.). There are 405 cis-eQTL in control flies only, 544 in treated flies only, and 440 in both conditions (Table 1 and Fig. 1a; Supplementary Table S2 has the complete cis-eQTL gene lists and data). The criteria for significant cis-eQTL are that the permutation LOD scores have a P value of less than 0.0001 (this is the nominal P value of the LOD threshold based on 1,000 permutations of the strain labels), which corresponds to a False Discovery Rate (FDR) of about 4% using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Permutation LOD scores are calculated for each of the 18,952 probesets independently. The strain labels for the microarray data is permuted 1,000 times and a LOD score is calculated for each marker interval for each probeset. Some QTL studies use a LOD cutoff of 3-to-3.5 to indicate a “significant” QTL peak, but the permutation method for calculating the LOD scores is more robust because it depends on the P values which are calculated for each probeset independently. Consequently, for one probeset, a LOD score of 2.8 at one interval could have a P value of less than 0.0001, whereas, for a second probeset, a LOD score of 3.8 at some other interval is needed to reach this threshold. The idea behind permutation LOD score methodology is that the 40 highest LOD scores (out of 1,000 permutations) for a QTL at a particular interval represents the critical value that provides an FDR = 0.04 (4%), which is a measure of the experiment-wide type I errors (i.e., false positives). In other words, if there is a real relationship between a marker and a QTL, such as an eQTL, then only 4% of the permutations will have a higher LOD score at a particular interval than the experimental data. Permutation analyses have to be conducted to determine the LOD scores with this method because, since each probeset has a different result after 1,000 permutations, there is no mathematical method to determine permutation LOD scores directly for each probeset.

Table 1.

Number of genes and GO categories in control and lead-treated trans-eQTL transbands. The 5 control (con) and 7 lead-treated (trt) trans-eQTL transbands and their approxiamate cytological locations are indicated in the first column. The second column shows the location of a transband by linkage group and centimorgans (cM) (1 = X chromosome (bands 1–20), 2 = 2L and part of 2R (bands 21–60), 3 = distal 2R (bands 61–80), and 4 (chromosome 3 (bands 81–100). GO, is the most significant gene ontological (GO) category for the genes in the transband. The false discovery rate (FDR) is shown underneath. # permutations with this GO category, is the number of permutations (out of 200) that have a transband with significant GO (FDR ≤ 0.01).

| Transbands | cM | Number of genes |

GO (FDR) | # permutations with this GO category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| con_27B | 2_46 | 117 | Cell Cycle (0.01) |

0/200 |

| con_50DF | 2_161 | 152 | Alternative splicing (4.41E-06) |

19/200 |

| con_70C | 4_136 | 103 | None | |

| con_72A | 4_141 | 134 | Hydrolase (3.87E-04) |

17/200 |

| con_73D | 4_146 | 278 | Hydrolase (1.43E-26) |

17/200 |

| trt_3E | 1_11 | 245 | Developmental Protein (5.68E-03) |

15/200 |

| trt_30AB | 2_71 | 194 | Actin Binding (4.80 E-04) |

0/200 |

| trt_57F | 3_6 | 96 | Golgi apparatus (0.01) |

0/200 |

| trt_63A | 4_21 | 140 | Mitochondrial part (0.0022) |

14/200 |

| trt_65A | 4_31 | 98 | None | |

| trt_73D | 4_146 | 222 | Hydrolase (7.65E-12) |

17/200 |

| trt_77E | 4_156 | 103 | Carbohydrate metabolic process (3.45 E-15) |

2/200 |

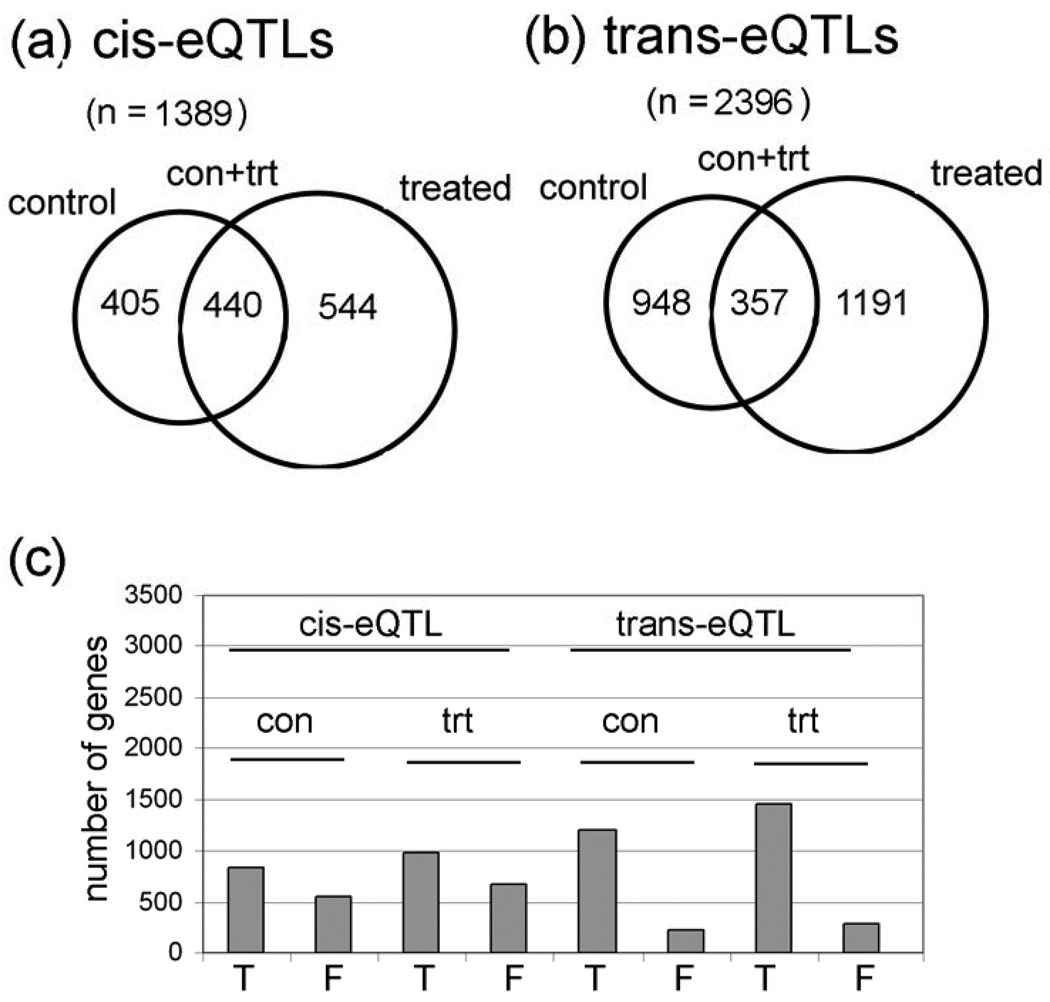

Figure 1. Control and lead-treated cis-eQTLs and trans-eQTLs.

(a) Venn diagrams of numbers of genes with cis-eQTLs and (b) trans-eQTLs in each category (con only, con + trt only, and treated only). Detailed information is in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Table S3. c, Graph of the number of true (T) and false (F) cis-eQTL based on outlier analyses of the 14 probes in each of the 18,000 Affymetrix probesets. Notice that cis-eQTL have a higher percentage of false eQTL than do trans-eQTL.

To further improve the data, we also eliminated potential “false eQTLs” that might be caused by single nucleotide polymorphisms at Affymetrix probe sites (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Table S2). Our method removes false eQTLs in genes that have one or more outlier probes in a probeset, presumably because the outliers correspond to probes that contain a SNP (see Materials and Methods). As expected, a much larger percentage of the cis-eQTLs are false by this criteria compared with trans-eQTLs (Fig. 1C). Since the Affymetrix II gene array that we used includes 18,952 probesets, the 1,389 cis-eQTL represent ~7% of the probesets.

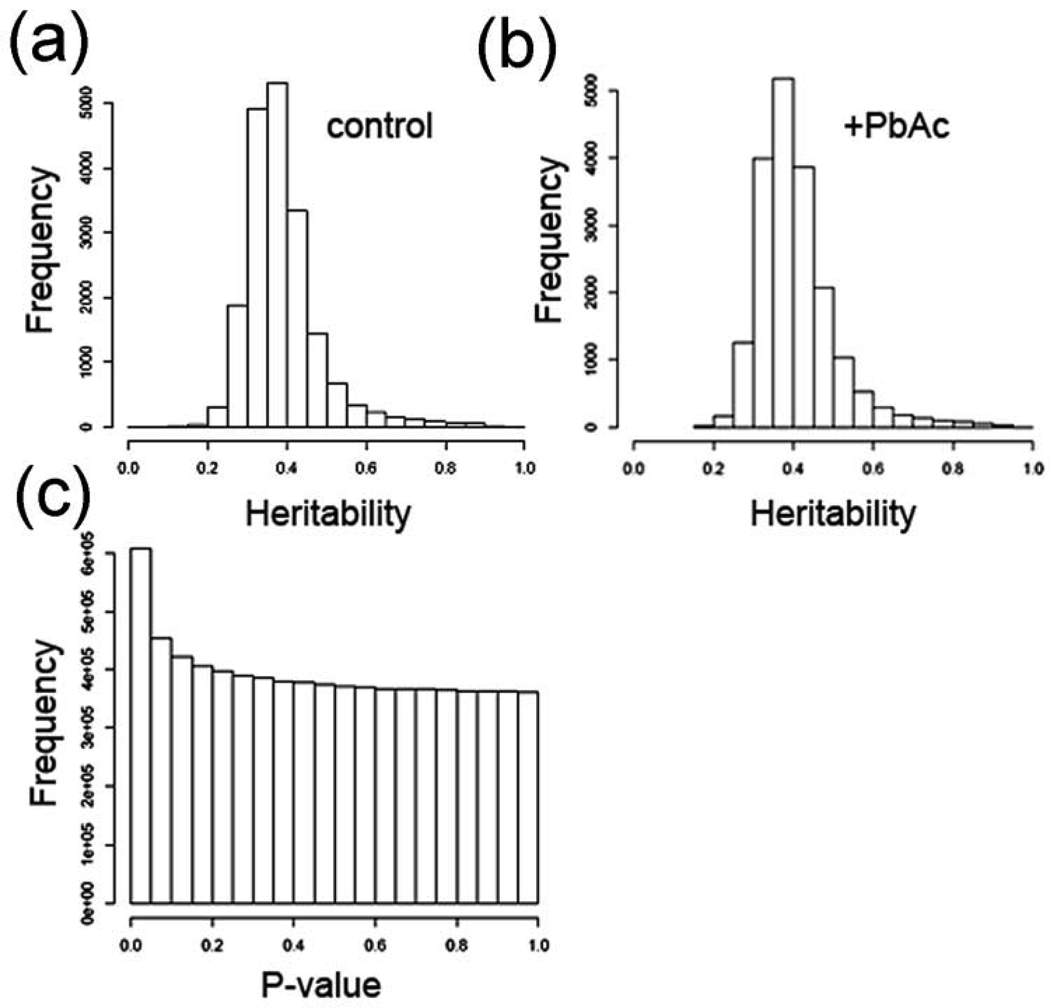

We identified a total of 2,396 probesets with trans-eQTLs (~13% of the probesets), 948 in control flies only, 1191 in lead-treated flies only, and 357 in both control and lead-treated flies (Fig. 1B; Table 1). As with cis-eQTLs, the criteria for significant trans-eQTLs are P values of < 0.0001 which corresponds to a FDR of about 4% (see Supplementary Table S3 for complete trans-eQTL probeset lists and data). This is consistent with published studies in other organisms. The mean heritability for steady-state mRNA levels is 38.7% without treatment effects, and heritability increased to 40.6% when treatment effects are considered (Fig. 2A and 2B). Heritability is the proportion of phenotypic variation (in our case, steady-state mRNA levels) in a population that is attributable to genetic variation among individuals, and “mean heritability” is the average heritability for all of the probesets. Heritability was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods). When all of the cis- and trans-eQTLs were analyzed, there are more eQTL with ‘significant’ P values (P < 0.05) than expected at random (Fig. 2C). A random event would have equal frequencies across the P value range (i.e., the bars would all be the same height), or possibly a dip in the number of P-values in the significant range (P < 0.05).

Figure 2. Heritability and P values for eQTL data.

(a) Heritability estimates without factoring in treatment (environment) effects. (b) Heritability estimates with treatment effects factored in. c, P values for all markers (82 markers), and every 5 cM between markers by all expression traits. As can be seen there are more ‘significant’ (P < 0.05) than expected at random.

Trans-eQTLs Identify Transbands (Hotspots) for Lead-Induced Changes in Gene Expression

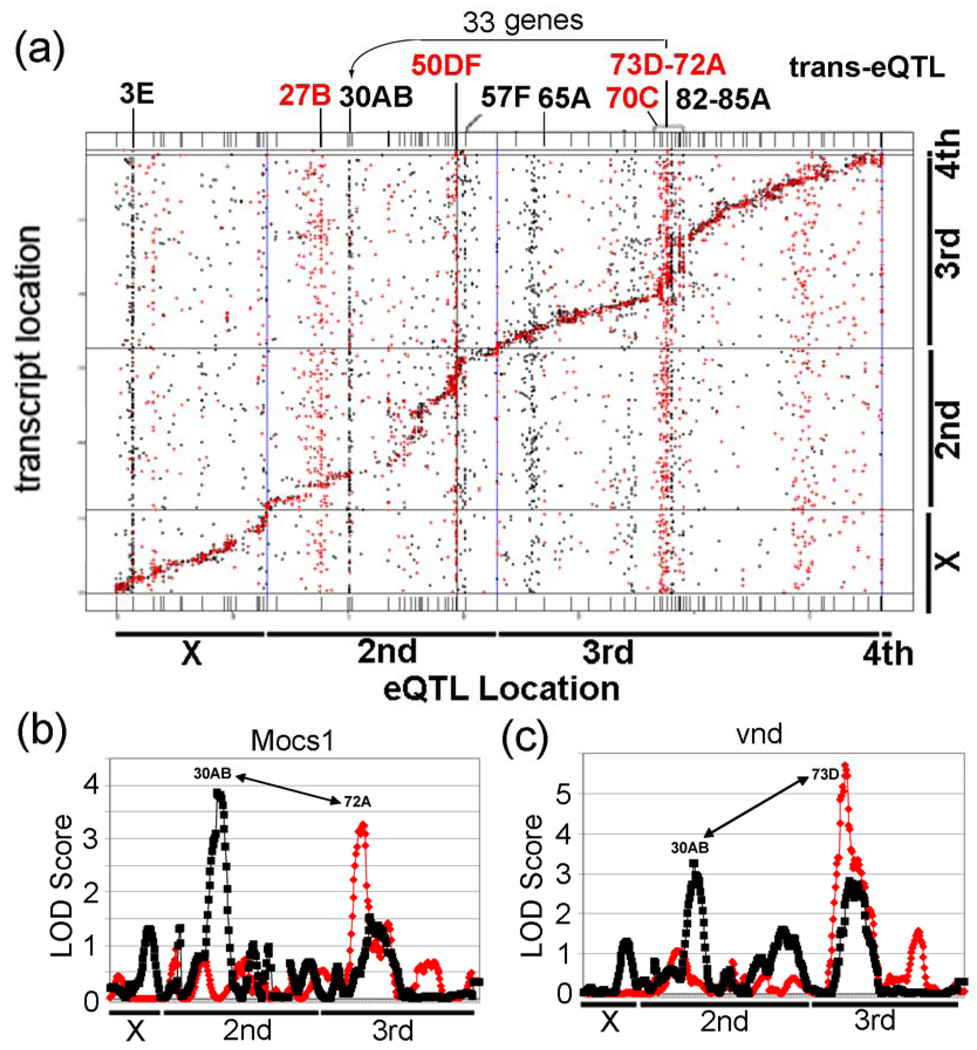

Our genetical toxicogenomic study identified 12 significant trans-eQTL “transbands” (5 in control samples and 7 in treated samples) at 11 different loci (the transband at 4_146 cM (73D) is located in both samples), each containing between 95 and 278 probesets (Table 1). A “transband” or “hotspot” is a group of trans-eQTLs that lie in a nearly vertical line (i.e., within a 5 cM window) in a “cis-trans-plot” that plots eQTL location on the x-axis and gene location on the y-axis (Fig. 3A). The nearly diagonal line corresponds to cis-eQTLs because these eQTLs coincide (i.e., within a 5 cM window) with the gene locations. Transbands are often interpreted as being a group of genes that are co-regulated by a master-modulatory gene that is encoded at the genomic location of the transband. The theory is that a DNA sequence polymorphism in a master modulatory gene (e.g., a deleterious SNP that decreases the activity of a transcriptional activator, such as by a missense mutation in the activating domain or a promoter mutation that decreases the expression of the master-modulatory gene) would cause all of the genes in a transband to be coordinately expressed at a low level when the master-modulatory protein has one genotype (i.e., it has the ‘bad’ SNP), but coordinately expressed at a high level when the master-modulatory protein has the other genotype (i.e., it has the ‘good’ SNP).

Figure 3. Results of a genetical genomics study of control and lead-treated from 75 RIL Drosophila lines.

(a) Locations of the eQTLs are represented on the x-axis and locations of transcripts (based on their chromosomal locations) are represented on the y-axis. eQTL locations for cis regulated genes every 5 cM are present along the diagonal. Notice the control trans-eQTL transbands at 27B, 50DF, 70C, and 73D–72A. Also, notice the lead induced transbands at 3E, 30AB, 57F, 65A, and 82D–85A. The genetic and physical maps of the lines are not perfectly aligned along the diagonal, due to regions with greatly reduced recombination in certain regions (bands 50–57 and 75–85) in the RILs compared to traditional crosses. It is not clear why these regions had reduced recombination. (b) Graphs of eQTL analysis of Mocs1, which is co-regulated by trans-eQTL at 30AB and 72A, and (c) vnd, which is co-regulated by trans-eQTL at 30AB and 73D. The LOD Score is the log of the probability distribution, as described in the Materials and Methods. Red, eQTL of genes from control flies. Black, eQTL of genes from lead-treated flies.

The size of the transbands was determined based on the number of probesets with significant trans-eQTL linkage in a 5 cM window in the experimental data. To find the minimum size of a transband, we determined that 96 probesets in a 5 cM window corresponds to P < 0.05, chi-squared test, so this was used as the minimum size. As shown in a “cis-trans-plot” of the eQTL data, untreated males have significant control trans-eQTL transbands at chromosomal regions 27B, 50DF, 70C, 72A and 73D (Fig. 3A (red); Supplementary Table S3). In contrast, males reared in lead-treated food have significant trans-eQTL transbands at chromosomal regions 3E, 30AB, 57F, 63A, 65A, 73D and 77E (Fig. 3A (black); Supplementary Table S3). This result suggests that the trans-regulation of most probesets in the trans-eQTL transbands (with the possible exception of 73D) differ between control and lead-treated flies. As is standard in Drosophila, unless otherwise indicated, we will refer to the transbands by their approximate cytological location rather than by cM linkage (e.g., 4_146, where 4 is the linkage group and 146 is in cM, corresponds roughly to 73D). As a technical note, chromosome 2 is split into two linkage groups (2 and 3) because of unlinked roo elements on the right arm of chromosome 2. The other chromosomes (X, 3, and 4) are single linkage groups.

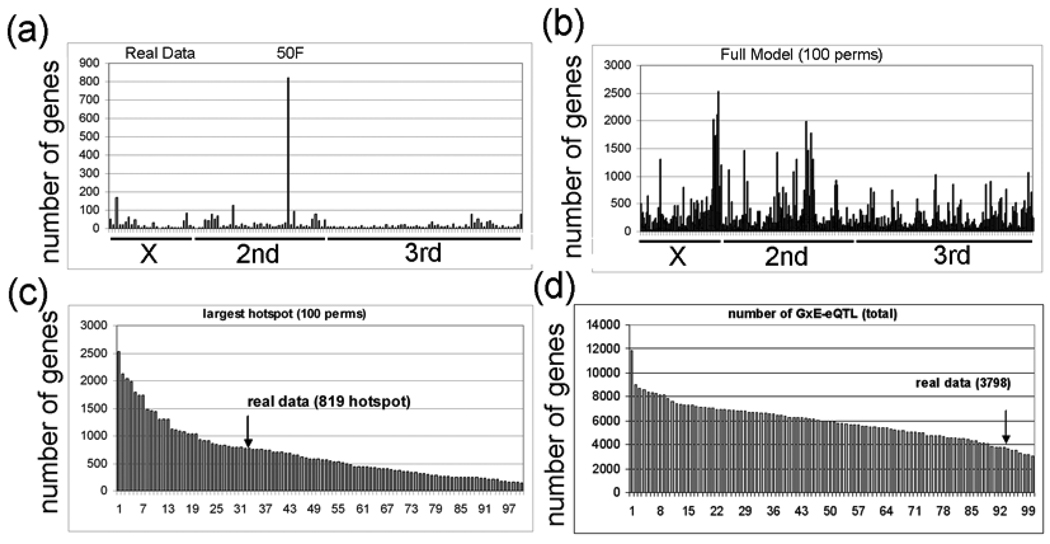

A possible explanation for the different genetic locations of most of the transbands in the two environments is that the transbands are correlation artifacts amongst co-expressed genes and are therefore false transbands [12]. In silico simulation studies have shown that false trans-eQTLs often cluster randomly to a small number of transbands because of artifacts in the architecture of the RILs [91]. In order to determine whether the transbands in Table 1 are true or false, we did 100 permutations of the strain labels of the 75 RILs of the data from the control-exposed flies (Fig. 4A,B) and another 100 permutations with the data from the lead-treated flies (Supplementary Fig. 4C,D; Supplementary Table S4) [12]. For each permutation, we analyzed: (1) the number of transbands, (2) the number of eQTLs, (3) the number of probesets that are the same (i.e., they ‘match’) in the control and lead-treated transbands, and (4) the size (total number of probesets with eQTLs) in all of the transbands. To be consistent with the experimental data, significant in silico permutation transbands have at least 95 probesets with an eQTL in a 5 cM window (i.e., 1–4.99 cM, 5–9.99 cM, etc.). The results are as follows:

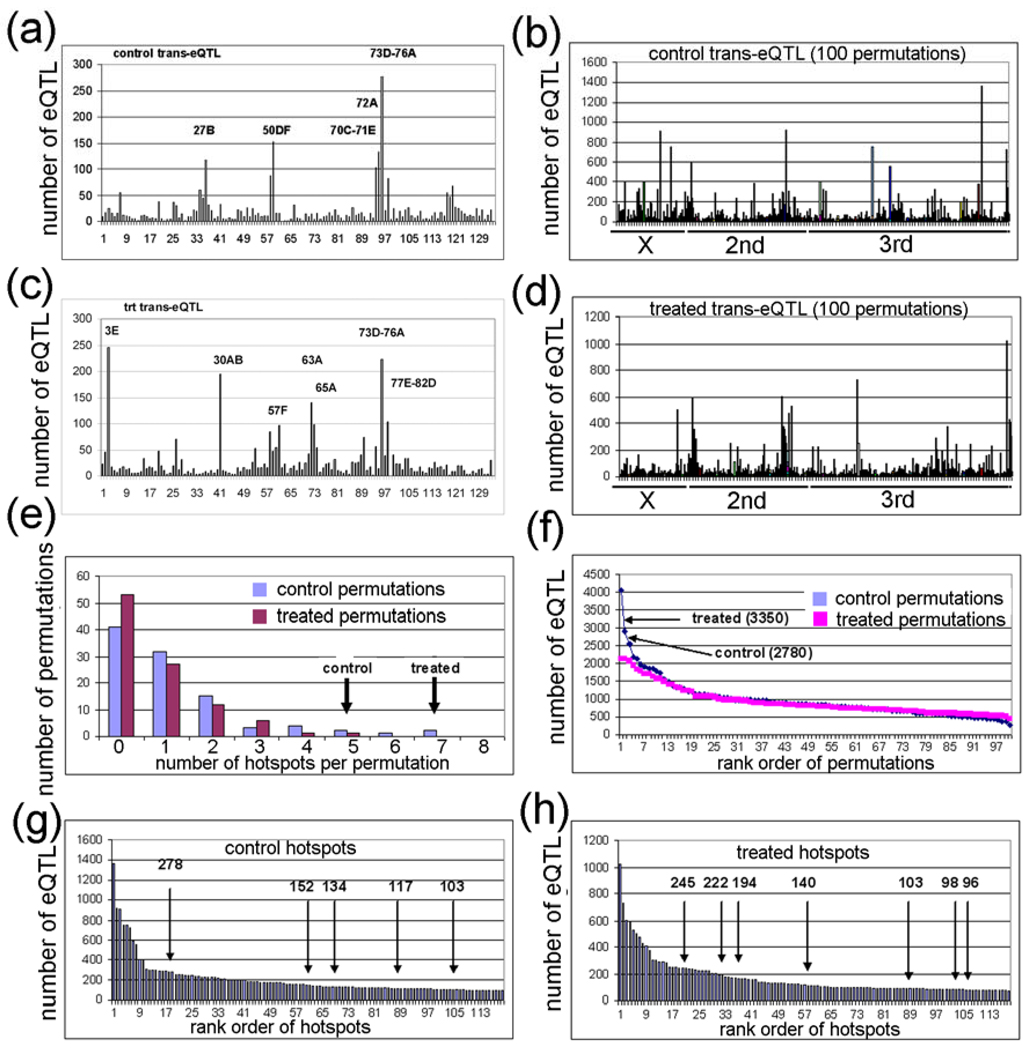

Figure 4. Permutation analysis of control and treated eQTL data.

(a,c) Plot of control and treated eQTL data showing genome location (x-axis) and the number of eQTL (y-axis). The 5 control and 7 treated eQTL transbands are indicated. (b,d) Plot of 100 control and 100 treated permutation analyses in which the RIL labels were randomized. (e) Plot of the number of transbands per permutation (x-axis) and the number of permutations with the corresponding number of transbands (y-axis). The experimental control and treated transband numbers are indicated (arrows). (f) Plot of the rank order of permutations (x-axis) versus the number of eQTL in the transband (y-axis). The number of eQTL in the control and treated transbands from the experimental data are indicated (arrows). (g,h) Plot of rank order of transbands (x-axis) versus the number of eQTL in the corresponding transband (y-axis). The control and treated transbands are indicated (arrows).

(1) The number of transbands was significantly larger for the experimental data (which we sometimes call “real data”) compared with the in silico permutation data (which we call “permutation data”) (P < 0.05, chi-squared test). Only 6 of the 200 permutations have greater than 4 transbands (3%), whereas, as mentioned above, there are 5 control transbands and 7 treated transbands in the experimental data. The largest number of transbands in the permutation data was 7, and this occurred one time (Fig. 4E). When the numbers of transbands in the control and treated datasets were added, there were 12 transbands in the real data but the largest number in the combined 100 permutations was 8 transbands (Supplementary Table S4).

(2) The number of eQTLs was significantly higher for the real data compared with the permutation data (P < 0.05, chi-squared test). Only 2 of the 200 permutations have greater than 2,780 eQTLs, whereas, there are 2,780 control eQTLs and 3,350 treated eQTLs in the real data. The false eQTLs were included in these analyses (i.e., the eQTLs are for probesets that have one or more outlier probes), but the real data and the permutation data have the same frequency of false eQTLs, so this probably will not affect the results. The largest two permutation transbands contain 4,040 and 2,921 eQTLs (Fig. 4F). When adding the number of eQTL in the control and treated datasets, there were 6,130 eQTL in the real data, but the largest number in the combined 100 permutations was 4,658 (Supplementary Table S4).

(3) The total number of matching probesets with eQTLs in control and treated transbands was significantly higher in the real data compared with the permutation data (P < 0.01, chi-squared test). There were a total of 225 matching probesets with eQTLs in the real data transbands (control versus treated), but the largest number of matching probesets with eQTLs in the permutation data transbands was 58 (control permutation 1 was compared with treated permutation 1, etc.). In fact, only 22 of the 100 permutation datasets had greater than one matching probeset with eQTLs in the transbands, and the total number of matching probesets with eQTLs in all 100 permutation datasets was only 223 (Supplementary Table S5). We analyzed the matching probesets with eQTLs in the real data more carefully and we identified 9 pairs of transbands that had 3 or more matching probesets with eQTLs in the transbands (Table 2). The largest match in the real data had 83 probesets with eQTLs which are regulated by the same transband at chromosome region 73D (4-146_73D) in both control and treated samples (Table 2). The same transband regulating one or more genes only occurred one time in the permutation dataset – one permutation had 11 genes regulated by the same transband in both control and lead-treated datasets (Supplementary Table S5).

Table 2.

Polarity of 5 control and 7 treated trans-eQTL transbands. The transband locations are in the first row (see Table 1). Polarity is determined in four manners (first row). For example, (B + Pb/B − Pb) is the ratio of the level of expression of a gene with the B genotype in the presence of lead over the level of expression of the same gene in the absence of lead. The ratio (n>1:n<1), where n>1 is the number of genes in a transband that have a relative increase in expression and n<1 is the number of genes in the same transband that have a relative decrease in expression.

| transband | B + Pb/B −Pb (n>1:n<1) |

O + Pb/O −Pb (n>1:n<1) |

O −Pb/B −Pb (n>1:n<1) |

O + Pb/B +Pb (n>1:n<1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| con_27B | (72:45) | (83:34)* | (71:46) | (34:83)* |

| con_50DF | (105:47)* | (38:114)* | (118:34)* | (85:67) |

| con_70C | (53:50) | (52:51) | (57:46) | (54:49) |

| con_72A | (105:29)* | (104:30)* | (108:26)* | (110:24)* |

| con_73D | (170:108)* | (170:108)* | (178:100)* | (176:102)* |

| trt_3E | (89:156)* | (61:184)* | (82:163)* | (60:185)* |

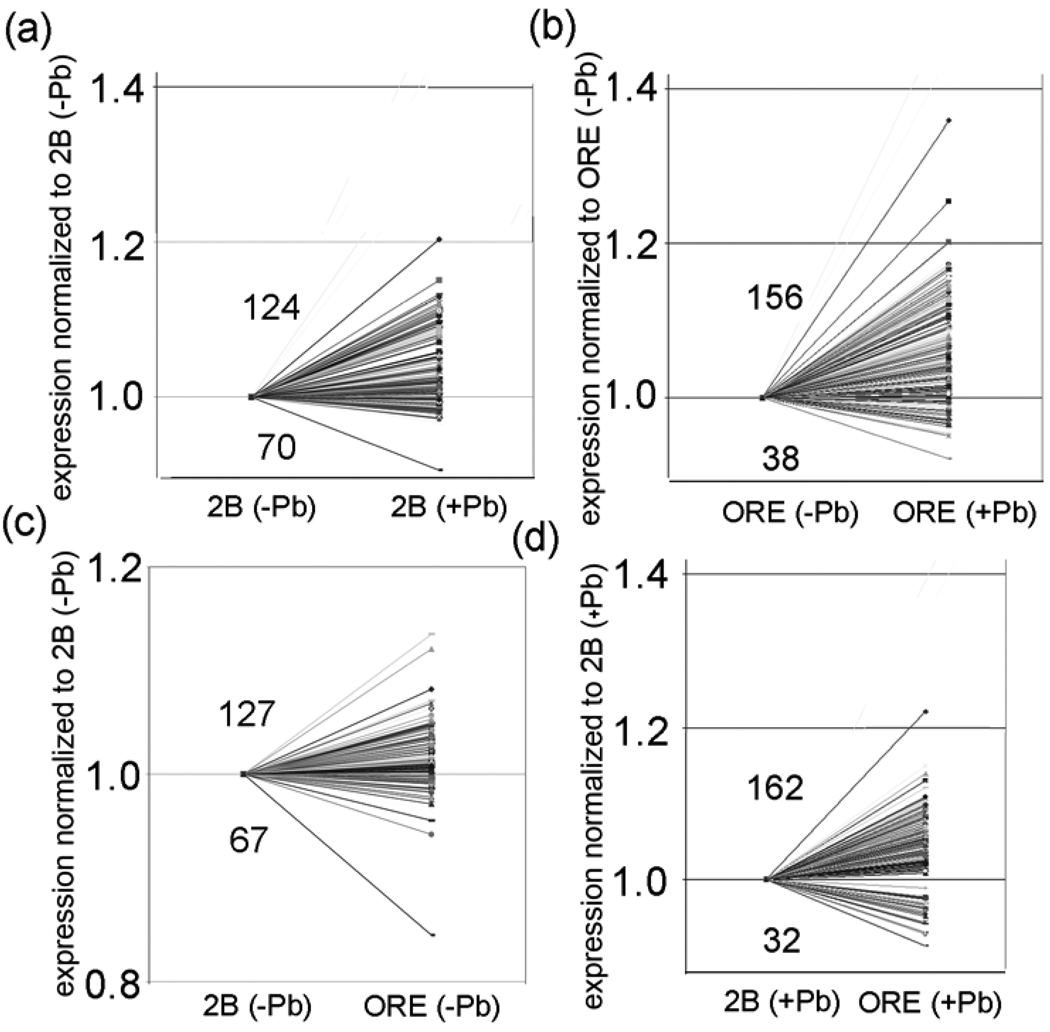

| trt_30AB | (124:70)* | (156:38)* | (127:67)* | (162:32)* |

| trt_57F | (21:75)* | (51:45) | (44:52) | (71:25)* |

| trt_63A | (75:65) | (32:108)* | (75:65) | (32:108)* |

| trt_65A | (33:65) | (17:81)* | (10:88)* | (11:87)* |

| trt_73D | (128:94)* | (125:97)* | (136:86)* | (138:84)* |

| trt_77E | (63:40) | (62:41) | (63:40) | (61:42) |

| Total | (1038:844)* | (951:931) | (1069:813)* | (994:888)* |

P < 0.001 (chi squared test). Bold text, indicates a significant enrichment in genes in a transband with a relative increase in expression. Red text, indicates a significant enrichment in genes in a transband with a relative decrease in expression.Total, the total number of genes in all 12 transbands that either increase or decrease expression in a column.

The number of matching probesets with eQTLs in two different transbands (in control versus treated) was also significantly higher in the real data compared with the permutation data (P < 0.05, chi-squared test). The largest category of matching probesets with eQTLs in the permutation data was in transbands that were separated by greater than 5 cM on the same chromosome or on different chromosomes. In this category, one permutation had 49 probesets with eQTLs, a second permutation had 26 probesets with eQTLs, and a third permutation had 18 probesets with eQTLs in two different transbands in the control and lead-treated permutation datasets. All of the remaining permutations had 13 or fewer probesets in two different transbands (Supplementary Table S5). This is in comparison to the 33 probests with eQTLs (corresponding to 33 genes) in the real data that were in the 30AB transband on chromosome 2 in the lead-treated dataset and in 2 adjacent transbands (72A and 73D) on chromosome 3 in the control dataset (Table 2). These 33 ‘co-regulated’ genes will be discussed further in a later section.

(4) The size of the transbands was NOT significantly higher for the real data compared with the permutation data (Fig. 4G,H). There were over 20 permutation transbands in the 200 simulations that were larger than the cutoff of 95 probesets with eQTLs. There would have to be over 800 genes with eQTLs in a transband to be a significant excess, but the largest transband in the real data was only 278 genes with eQTLs (Fig. 4G,H; Table 1).

The fourth analysis, that the transband size in the real data is not significantly higher than the permutation data, was not unexpected because, as mentioned above, false trans-eQTLs often cluster randomly to a small number of transbands [91]. Nevertheless, the significance of the first three analyses (the total number of transbands, the total number of probesets with eQTLs, and the total number of matching probesets with eQTLs) suggest that our other approaches (1–3) might be valid for identifying eQTLs, transbands, and co-regulated genes in the experimental data (see Discussion).

Some Transband Probesets are Polarized for Expression Based on Genotype and/or Treatment

In the cis-eQTL analysis, we eliminated false cis-eQTL artifacts that are caused by probe(s) in a probeset that poorly hybridize to the sample because of SNPs or other sequence mismatches. If the false cis-eQTLs are not eliminated, there would be an apparent ‘polarization’ of expression (steady state mRNA levels) based on genotype if one of the two parental strains was used to make the expression array [19]. However, in studies such as ours where neither parental strain has been sequenced, there should be no polarity for expression based on genotype because there are likely an approximately equal number of SNPs in ORE and 2B compared with the reference strain (y1; cn1 bw1 sp1) [1]. Fortunately, trans-eQTLs are less susceptible to this SNP-based artifact because, by definition, there are no SNPs that map to the probesets in a transband [19]. Therefore, polarization of expression with the genotype of genes in a transband as a dependent variable (which we call “polarization of expression based on genotype”) might indicate a common regulator for a majority of genes in a transband.

We calculated the polarity of expression based on both genotype and environment (+/− Pb). In these analyses, we found that expression of probesets with trans-eQTL overall show no polarity of expression based on genotype (data not shown). In other words, of the 2,396 total trans-eQTLs (see Fig. 1), the number of probesets that have higher steady-state mRNA levels when the genotype is ORE is approximately the same as when the genotype is 2B. However, the probesets in individual transbands often show such polarity, suggesting that steady-state mRNA levels are regulated by genes that are encoded at the transband loci. For example, if a transcription activator at a transband locus is expressed at a low level in 2B but at a high level in ORE, then there should be a polarity of expression where ORE relative expression is higher than 2B relative expression for all of the genes regulated by the activator in the transband.

We analyzed polarity of expression based on genotype in the 12 transbands by determining the ratio of the expression level of a probeset with one genotype over the expression level of the same probeset with the other genotype with the same environmental treatment. Specifically, we determined the ratio (ORE−Pb)/(2B−Pb) and (ORE+Pb)/(2B+Pb) for all of the probesets in the 12 transbands (Table 2). In the experimental data from flies with no lead treatment, 5 transbands are enriched in probesets that have higher expression in ORE (con_50DF, con_72A, con_73D, trt_30AB, and trt_73D) and 2 transbands have a significant enrichment in probesets that have higher expression in 2B (trt_3E and trt_65A) (P < 0.001, chi squared test; Table 2; Fig. 5C; Supplementary Table S3). In the lead-treatment group, 5 transbands have a significant enrichment in probesets that have higher expression in ORE (con_72A, con_73D, trt_30AB, trt_57F, and trt_73D) and 4 transbands have a significant enrichment in probesets that have higher expression in 2B (con_27B, trt_3E, trt_63A, and trt_65A) (P < 0.001, chi squared test; Table 2; Fig. 5D; Supplementary Table S3). Of the 12 transbands, only two did not show a polarity of expression based on genotype in at least one of the two environments (con_70C and trt_77E).

Figure 5. The transband at 30AB is polarized for genes that are induced by lead.

(a,b) More genes have an increase in relative expression when the transband has either the 2B (a) or the ORE (b) genotype in the presence of lead. This indicates that there is a significant polarity of increased expression for the probesets in the 30AB transband after lead exposure regardless of genotype. (c,d) When the 30AB transband has the ORE genotype, there is a polarization of increased expression in either the presence (a) or absence (d) of lead. This indicates that there is a significant polarization of increased expression for the probesets in the 30AB transband when the genotype is ORE regardless of environment. The polarization level of all of the hotspots is in Supplementary Table 3.

Since we analyzed relative expression levels in two environments, and only 1 of the transbands was present at the same location in both environments (con_73D and trt_73D), it seemed likely that some of the transbands might also be polarized for expression based on environment. For example, if a transband encodes a transcription activator that is induced by lead, then all of the genes in the transband would have higher relative expression levels in the lead-treatment group. To determine whether there is polarity for expression of probesets in a transband based on environment, we determined the ratios (2B+Pb)/(2B−Pb) and (ORE+Pb)/(ORE−Pb) for all of the probesets in the 12 transbands (Table 2). We determined that 5 transbands with the 2B genotype are significantly enriched in probesets that are upregulated by lead (con_50DF, con_72A, con_73D, trt_30AB, and trt_73D) and 2 transbands are significantly enriched in probesets that are down-regulated by lead (trt_3E and trt_57F) (P < 0.001, chi squared test; Table 2; Fig. 5B; Supplementary Table S3). We also determined that 5 transbands with the ORE genotype are significantly enriched in probesets that are upregulated by lead (con_27B, con_72A, con_73D, trt_30AB, and trt_73D) and 4 transbands are significantly enriched in probesets that are down regulated by lead (con_50DF, trt_3E, trt_63A, and trt_65A) (P < 0.001, chi squared test; Table 2; Fig. 5A; Supplementary Table S3).

We do not fully understand the reason for the polarization of gene expression in the transbands based on the genotype and/or the environment, but it suggests that trans-regulators with differing sensitivities to lead might be involved in co-regulating the genes in a transband (see Discussion). In the next section, we analyze this further by investigating specific probesets that are co-regulated by two different transbands in the two environments.

Co-Regulation of Genes by Two Different trans-eQTLs

As discussed in a previous section, further analysis of probesets from the real data identified a group of 33 probesets that are in two adjacent transbands on the 3rd chromosome in the control dataset (19 probesets at 4_141 cM (72A) and 14 probesets at 4_146 cM (73D)) and in a single transband at a different location on the 2nd chromosome in the lead-treated dataset (2_71 cM (30AB); Table 3; Supplementary Table S6). We refer to these 33 probesets as being “co-regulated” by two different trans-eQTLs. The proteins encoded by the 33 probesets (i.e., 33 genes) are involved in several potentially lead-related processes, such as heavy metal sequestration or storage (MtnA and Mocs1) [5,6,37,38], nervous system development and function (tsp2a, tsp42ec, tsp42er, CG4301, CG31720, CG5096, inx7, vnd) [42,66,103,110], detoxification (CG4562, CG10505, rtet) [78], and proteolysis (pcl, CG33127, κTry) [101] (Table 4).

Table 3. Genes regulated by transbands in both control and treated samples.

Shown are matches between trans-eQTL transbands in control and treated data. Only 3 control and 3 treated transbands had four or more matches in genes amongst the transbands. Control (con), treated trt, chromosome and map positions in cM (4–136, 4–141, 4–146, 2–71, and 4–156), and approximate cytological positions (70C–71E, 72A, 73D, 30AB, and 77E) are indicated.

| trt_2–71_30AB | trt_4–146_73D | trt_4–156_77E | |

|---|---|---|---|

| con_4–136_70C | 4 | 14 | 4 |

| con_4–141_72A | 19 | 25 | 3 |

| con_4–146_73D | 14 | 83 | 30 |

Table 4. Description of genes co-regulated by two trans-eQTL loci.

There are 19 probesets co-regulated by 72A and 30AB (CG14872 is represented by two probesets) and 14 genes co-regulated by 73D and 30AB.

| Co-regulated by 72A and 30AB |

Affy_ID | GO:Biological process | gene location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | CG14872 | 1623028_at, | Transporter activity | 88F7 |

| 2. | CG17544 | 1623069_s_at | Fatty acid metabolism, Pristenoyl-CoA oxidase | 37D4,5 |

| 3. | CG15347 | 1623761_at | ? | 7E11 |

| 4. | CG31087 | 1624569_at | Nuclear gene | 96D1 |

| 5. | CG4781 | 1625816_at | Protein binding | 60D10 |

| 6. | tsp2a | 1626767_at | Synapse formation, tetraspanin 2a | 1F4 |

| 7. | CG8907 | 1626881_at | ? | 89E8 |

| 8. | tsp42ec | 1630051_at | Synapse formation, Tetraspanin | 42E5 |

| 9. | CG4301 | 1630471_at | Ion transport, Ca-transporting ATPase | 14C4 |

| 10. | Mocs1 | 1631994_a_at | Mo utilization, Mo-cofactor binding protein (CG33048) | 68A4 |

| 11. | CG15422 | 1632575_at | Pathogenesis | 24D3 |

| 12. | pcl | 1633955_at | Proteolysis, Pepsinogen-like | 1B2 |

| 13. | pes | 1634913_s_at | Defense response, Scavenger receptor | 28D3 |

| 14. | tsp42er | 1634977_at | Synapse formation, Tetraspanin | 42E7 |

| 15. | CG11961 | 1637042_a_at | Peptidase activity | 56D1,2 |

| 16. | CG31720 | 1637306_at | Signal transduction, G-protein couple receptor | 31B1 |

| 17. | myo61F | 1638278_s_at | Vesicle-mediated transport, Cytoplasmic myosin | 61F6 |

| 18. | CG5096 | 1639478_at | Neuron development, Receptor in neurons | 31D11 |

| 19. | CG14872 | 1640720_a_at | Transporter activity | 88F7 |

|

Co-regulated by 73D and 30AB |

||||

| 20. | CG8062 | 1624181_at | Fatty acid biosynthesis Mono-carboxylic acid transporter | 18C2 |

| 21. | CG4562 | 1625778_at | Detoxification Toxin transporter | 92B4 |

| 22. | CG33127 | 1626718_at | Proteolysis Trypsin | 21B8 |

| 23. | CG6484 | 1626734_at | Glucose homeostasis, Glucose transporter | 54C10 |

| 24. | CG3987 | 1627047_at | Muscle development, Mesoderm development | 88E2 |

| 25. | RpA-70 | 1627380_at | Protein biosynthesis, Ribosomal protein A-70 | 84F6 |

| 26. | CG14299 | 1628826_at | Nuclear gene | 91C6 |

| 27. | kappaTry | 1632055_at | Proteolysis, Kappa trypsin, CG12388 | 47E3 |

| 28. | MtnA | 1632873_at | Metal transport, Metallothionine | 85E9 |

| 29. | vnd | 1635383_at | Neuron development, Ventral nervous system defective | 1B10 |

| 30. | CG1246 | 1638174_at | ? | 62E8 |

| 31. | inx7 | 1638225_a_at | Gap junction protein, Innexin 7 | 6E4 |

| 32. | CG3884 | 1638816_at | ? | 49E4 |

| 33. | CG10505 | 1639368_at | Detoxification, Toxin transporter | 57D7,8 |

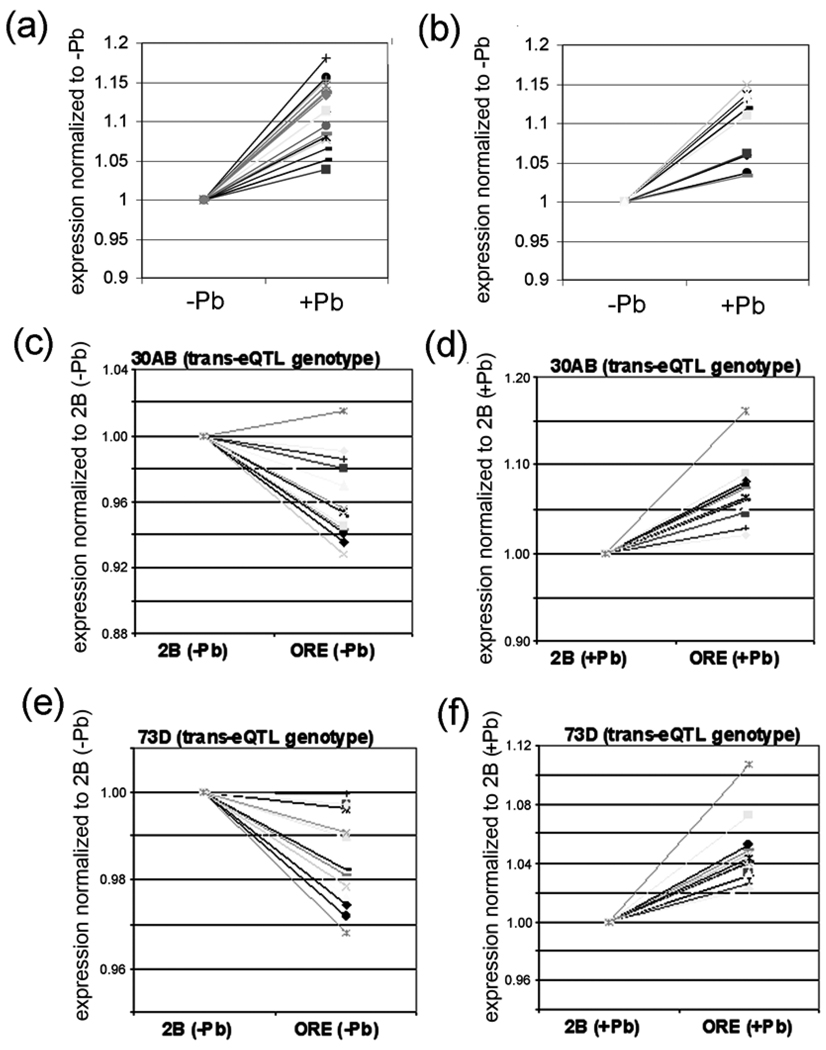

Comparison of the microarray signal intensities of these 33 genes co-regulated by the 2nd and 3rd chromosome transbands indicates that all 33 of them are significantly up-regulated by lead (Fig. 6A,B; Supplementary Table S6). Interestingly, there is approximately the same (or lower) expression when the 30AB transband has the ORE or the 2B genotype in the absence of lead (i.e., (ORE−Pb)/(2B−Pb) ≤ 1), but an increase in expression in ORE versus 2B in the presence of lead (i.e., (ORE+Pb)/(2B+Pb) > 1) (Fig. 6C,D; Supplementary Table S4). There is a similar pattern for the 72A or 73D transbands (Fig. 6E,F; Supplementary Table S6). Such “crossing of the lines” in this type of GxE plot is suggestive of a genotype-by-environment (GxE) interaction [44]. More rigorous GxE-eQTL analyses are described in the next two paragraphs.

Figure 6. Effect of lead on the expression of genes co-regulated by 30AB and 73D.

(a) All 19 genes that are co-regulated by 72A and 30AB show an increase in expression after lead exposure. (b) All 14 genes co-regulated by 73D and 30AB also show an increase in expression after lead exposure. The data in a and b is from the mean expression levels from the 75 RILs in the absence of lead and the mean levels from the 75 RILs in the presence of lead. (c–f) Effects of genotype and environment on the 14 genes co-regulated by the transbands located 30AB and 73D. The relative expression of the 14 genes with the indicated transband genotype was normalized to 1 and the effect of changing the hotpot genotype is shown. Notice that relative expression decreases slightly (except for one gene) in the absence of lead but increases in the presence of lead when the transband genotype changes from 2B to ORE. A similar pattern is seen for all 19 genes that are co-regulated by the transbands located at 72A and 30AB (Supplementary Table S4).

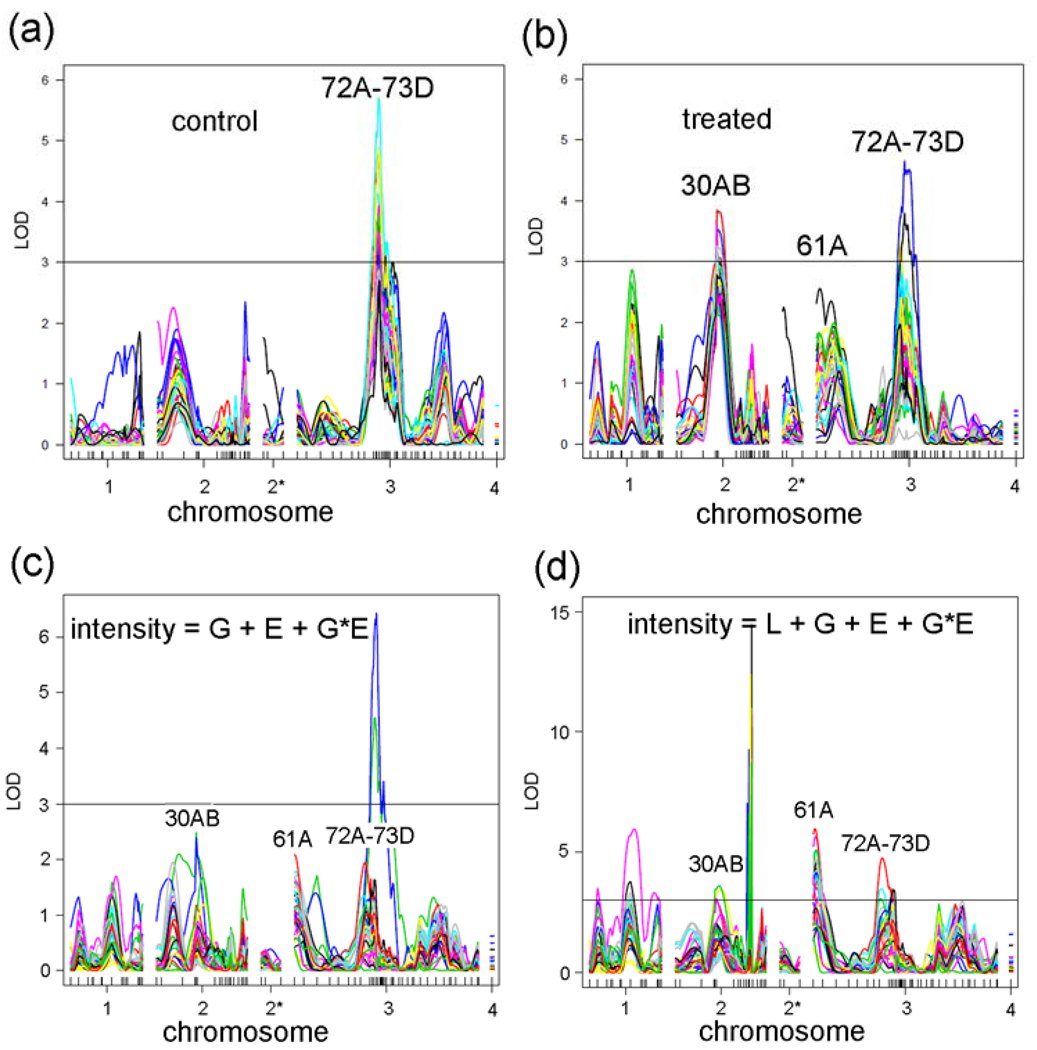

Log of distribution (LOD) plots of the 33 co-regulated genes shows a significant peak at 72A–73D in the control data and two significant peaks at 30AB and 72A–73D in the treated data (Fig. 7A,B). To determine whether there is a significant GxE interaction amongst the 33 genes co-regulated by two different trans-eQTLs, we performed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the model: intensity = G + E + GXE + error, where G is the genotype (ORE or 2B), E is the environment (control or lead), and “error” is the root mean square error. In a plot of the GXE term, this analysis indicates that there is no significant GXE peak at 30AB and a peak for 3 probesets at 72A–73D. “Significance” lines at LOD = 3 were drawn in Fig. 7 for reference because this LOD is a common threshold used in QTL studies. However, as discussed earlier, the “significance” was determined for each probeset by permutation analyses and differed for each probeset (see Materials and Methods). All of the peaks at 72A–73D in Fig. 7A are significant, and all of the peaks at 30AB and 72A–73D are significant in Fig. 7B (Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 7. QTL analyses of 33 genes co-regulated by two loci.

(a) eQTL graphs of 33 genes in control flies. (b) eQTL graphs of 33 genes in treated flies. (c) GxE graphs of 33 genes where Line (L) is not an independent covariate (intensity = G + E + GXE + error). (d) GxE graphs of 33 genes with the full model (intensity = L + G + E + GXE + error). Notice that more genes cross the LOD = 3 line at 30AB, 61A, and 72A–73D in the full model compared with c.

Next, using this ‘simple’ model (intensity = G + E + GXE + error), we calculated the GXE term for all 18,952 probesets. Interestingly, we identified a major GxE hotspot located at 50DF that contains 819 probesets (Fig. 8A). The most significant GO category that is enriched for the genes that correspond to the 819 probesets is “nervous system development” (FDR < E-10). Table 5 shows the 59 genes in this GO category, and all 59 of these genes are down-regulated by lead. However, the meaning of this result is not clear because very few of the 819 probesets (53) have a main effect eQTL located at 50DF, and the robustness of a GXE effect in the absence of a main effect is uncertain (see Discussion). The significance of the 819 probesets with GXE interactions in the ‘simple’ model is further questioned by analyzing GXE interactions in 100 permutations of the strain labels. We found that 34 permutations have GXE hotspots with greater than 819 probesets (Fig. 8B,C) and that 94 of the permutations have greater total numbers of GxE-eQTL (Fig. 8D).

Figure 8. Permutation analysis of the GxE-eQTL data.

a, The experimental GxE-eQTL data are plotted with eQTL location (x-axis) and number of probesets with eQTL at the corresponding location (y-axis) (intensity = G + E + GXE + error). The hotspot with 812 probesets at 50DF is indicated (50F). b, The GxE-eQTL results of 100 permutations is plotted (intensity = G + E + GXE + error). c, The rank order of GxE-eQTL hotspots (x-axis) in the 100 permutations is plotted versus the number of genes with eQTL in the largest transband (y-axis). The experimental data (real data) has 819 probesets in the largest transband. d, The rank order of the number of GxE-eQTL in the 100 permutations is plotted. Notice that most (94%) of the permutations have larger transbands than the experimental data (arrow).

Table 5. Nervous system development genes down-regulated by lead.

All 59 genes are down-regulated by the GxE-eQTL hotspot located at 50DF. The permutation LOD scores are shown. <3, NS (Not significant). For 8 of the genes, the LOD score is less than 3 and not significant.

| Gene Name (GO: nervous system development) |

LOD Score | Gene Name (GO: nervous system development) |

LOD Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABNORMAL | 4.4 | KUZBANIAN | 3.9 |

| CHEMOSENSORY JUMP 6 | |||

| ALK | <3, NS | LADYBIRD LATE | <3 |

| AMYLOID PROTEIN | 8.2 | LAMIN | <3 |

| PRECURSOR-LIKE | |||

| ANK2 | <3, NS | LEONARDO PROTEIN | 5.1 |

| BEATEN PATH IA | 5.8 | LIM1 | 3.4 |

| BEATEN PATH IIA | 5.3 | LONGITUDINALS | 3.4 |

| LACKING | |||

| BONUS | 4.3 | MASTERMIND | 8.3 |

| BROAD | 5.0 | MINIBRAIN | 4.4 |

| CACOPHONY | 6.0 | MUSCLEBLIND | 6.2 |

| CADHERIN-N | 7.9 | NETRIN-B | 6.4 |

| CHARLATAN | 5.8 | NEUROGLIAN | 6.9 |

| CHOLINE | 7.4 | OCELLILESS | 5.3 |

| ACETYLTRANSFERASE | |||

| CONNECTIN | 9.6 | PHYLLOPOD | 6.4 |

| COUCH POTATO | 5.1 | POINTED | 5.3 |

| CUT | 4.9 | PROTEIN SPLIT ENDS | 4.3 |

| DACHSHUND | 3.9 | PURITY OF ESSENCE | 4.8 |

| DERAILED | 4.9 | RETAINED | 3.6 |

| DICHAETE | 4.2 | RHOGAP-93B | <3, NS |

| DISCS LARGE 1 | 7.4 | RHOGAP-P190 | <3, NS |

| DLIC2 | <3, NS | ROUNDABOUT | 5.2 |

| DUMPY | 5.0 | SCABROUS | 8.2 |

| EMBRYONIC LETHAL, | 7.2 | SCALLOPED | 5.9 |

| ABNORMAL VISION | |||

| FASCICLIN 2 | 6.0 | SCRATCH | 6.7 |

| FRUITLESS | 4.2 | SCRIBBLER | 4.8 |

| G PROTEIN O 47A | 7.1 | STARRY NIGHT | 10.6 |

| G PROTEIN -SUBUNIT 13F | 5.1 | STILL LIFE | 5.0 |

| HOMOTHORAX | 6.0 | TRIO | <3, NS |

| INSULIN-LIKE RECEPTOR | 4.2 | TURTLE | 4.9 |

| KIN OF IRRE | 3.5 | VEIN | 6.3 |

| KRUPPEL | 3.8 |

Although the finding that the GxE-eQTL hotspot is enriched in neurodevelopmental genes is intriguing, the fact that few of the 33 genes regulated by trans-eQTL at 30AB or 72A–73D have GXE-eQTL LOD scores greater than 3 (Fig. 7C) suggests that the original ANOVA model is incomplete. Therefore, we added a new term to the model, L (Line, the RIL (roo number) designation), as a non-dependent covariate. The new model (which we will refer to as the ‘full model’) is: intensity = G + E + L + GXE + error (Fig. 7D). This full model indicates that a greater number of probesets have significant GXE peaks at 30AB and 72A–73D (compare Figs. 7C,D). Interestingly, the most significant peak is at 61A, which does not correspond to a main effect eQTL peak. As with the 50DF peak discussed above, the meaning of a GXE peak in the absence of a main effect peak is controversial. Because it is computationally extensive, we have not yet completed the permutation analysis of the GXE interactions with Line as a non-dependent covariate for all 18,952 probesets. However, the permutation LOD scores (with L as an independent covariate) for the 59 “nervous system development” genes are shown in Table 5 and all but 8 of them are significant (i.e., permutation LOD>3).

Discussion

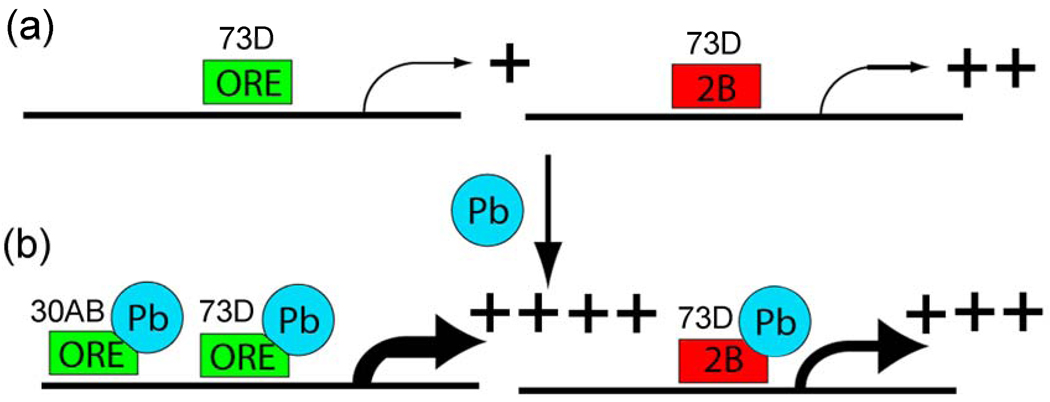

In the first genetical genomic study with RILs performed in insects, we show evidence that adult Drosophila melanogaster (fruit flies) have 12 major master modulatory trans-eQTLs that contain from 96 to 278 genes each, which places this organism somewhere between C. elegans and mice in terms of the number and complexity of the trans-eQTL targets (transbands) [14,72]. We extended the genetical genomics approach by comparing control flies with flies exposed to the developmental neurotoxin lead and identified transbands that differ in the two environments. The most interesting finding is that 33 genes are co-regulated by two transbands, one on the second chromosome at 30AB and one on the 3rd chromosome at either 72A or 73D which is located in the adjacent 5 cM window that was used to define transbands. Because the resolution of QTLs is often larger than 5 cM, it is likely that the 3rd chromosome transbands are the same locus, which for simplicity we will call the “73D transband” in Fig. 9 and in the following paragraphs.

Figure 9. Model for co-regulation by trans-eQTL at 30AB and 73D.

a, The hypothetical trans-activator encoded at the 73D transband locus (rectangle) is required for basal transcription of the 33 genes co-regulated by both 73D and 30AB in the absence of lead. In the presence of lead (Pb), the trans-activator encoded at the 73D transband locus further increases steady-state mRNA levels when it has either the ORE (green) or 2B (red) genotype. However, the trans-regulator encoded at the 30AB transband locus (oval) further increases steady-state mRNA levels only when it has the ORE genotype. A second possibility is that a “translational stabilizer” encoded at the 73D transband locus is required for basal stabilization of the mRNA for the 33 genes co-regulated by both 73D and 30AB in the absence of lead. In the presence of lead, the translational stabilizer encoded at the 73D transband locus further stabilizes target mRNA levels (i.e., protects from degradation) when it has either the ORE or 2B genotype. In this example, the translational stabilizer encoded at the 30AB transband locus further increases steady-state mRNA levels only when it has the ORE genotype. A third possibility is an “indirect model” in which signaling components upstream of the transcription or translation factors are regulated by lead. In this example, the signaling protein encoded at the 73D transband locus activates a transcription factor in either the presence or absence of lead. For example, the signaling protein encoded at the 30AB locus could inhibit a repressor of a transcription factor (R) better when it has the ORE genotype than when it has the 2B genotype. In all three models, Pb induces the highest steady state mRNA levels for the 33 targets genes when both 73D and 30AB loci have the ORE genotypes.

These 33 co-regulated genes show significant genotype-by-environment (GxE) interactions for both the 30AB transband and the 73D transband. We have recently shown by traditional phenotypic QTL analysis that the 30AB locus is involved in lead-dependent changes in locomotor activity, which we believe is an important validation of the 30AB eQTL transband [53]. We propose a model based on our data that a trans-regulator located at 73D increases expression of its target genes when it binds lead, regardless of the genotype of the 73D transband (Fig. 9A). In contrast, a second trans-regulator located at 30AB only increases expression (or somehow increases steady state levels of mRNAs via transcriptional or post-transcriptional mechanisms) of the co-regulated target genes in the presence of lead when it has the ORE genotype (Fig. 9B). This model can explain much of the data, but other possibilities exist. For example, the putative trans-regulator could increase the stability of the target gene mRNAs or there could be an indirect effect on steady-state mRNA levels. Fine-mapping the genes that underlie the QTLs, which will be aided by sequencing both of the ORE and 2B genomes, should help in determining the precise mechanism involved.

The first genetical genomics study that identified genes with significant GxE interactions was a study in C. elegans in which the authors identified a group of genes with trans-eQTL that are induced by heat shock, so called “plastic QTL” or pQTL [72]. Smith and Kruglyak recently did a detailed analysis of GxE-eQTL in yeast (which they call “gxeQTL”) grown in either glucose or ethanol as a sole carbon source [104]. Other laboratories have identified genotype-by-environment interactions in which the ‘environment’ is a different tissue (e.g ., brain versus liver [55]), but we believe that ours is the first ‘genetical toxicogenomic’ study that combines genetical genomics with toxicogenomics. The benefit of adding environmental perturbations in genetical genomics studies is discussed in a recent paper by Li and colleagues [73]. Interestingly, we identified a GxE-eQTL transband with 814 genes that does not correspond to a main-effect eQTL transband. Of these 814 genes, 59 of them are in the GO category ‘nervous system development,’ and 51 of these genes have significant GxE-eQTL when L (Line) is a non-dependent covariate. We are undertaking a study to identify all of the genes with GxE-eQTL in Drosophila, where L (line) is a non-dependent covariate, but this is beyond the scope of the present study. The meaning of a GxE-eQTL without a main-effect eQTL is controversial, and more work needs to be done to determine whether such GxE-eQTL are biologically meaningful.

We showed that there are 12 trans-eQTL transbands; 5 control transbands and 7 lead-treated transbands at 11 different loci (Table 1). The existence of trans-eQTL transbands has been validated in yeast [13,118], but there is controversy as to whether trans-eQTL transbands identified in other model organisms are real or correlation artifacts [30]. This has been illustrated by a simulation study that showed that the five most populated bins of expression data contained 20% of the significant, but spurious, trans-eQTLs [91]. One suggested solution, which we did in this manuscript, is to perform permutation analyses of the eQTL data (i.e., permuting the genotype assignments only and keeping the original expression values for all the samples) [12]. However, such permutation analyses, done by others, seemingly invalidate numerous of the previous studies if one only considers the size of the transband as the most important criterion [12]. Therefore, we have more extensively analyzed the permutations in our study and found that (1) the number of transbands, (2) the total number of eQTL, and (3) the number of identical genes in control and treated transbands might be more important criteria than the absolute size of the transband.

Another approach to validating transbands is to test gene expression for individual probesets within them for significant genetic correlation with variation among lines for functionally related traits assessed independently. The 30AB region of the Drosophila genome has been identified as both a behavioral QTL for changes in locomotion in response to lead treatment [53] and as a transband in the present study that regulates 194 probesets in response to lead. We can therefore search for individual probesets within the 30AB region showing variation in gene expression after lead exposure among roo lines that is correlated with variation among the same lines for their behavioral response to lead to further identify potential candidate genes for both the behavioral and transband eQTL. Any probesets identified in this manner can be further screened by correlating gene expression from candidate probesets linked to 30AB with gene expression from candidate probesets regulated from the 30AB transband.

For present purposes, we focused on 122 probesets that include 30AB and the proximate half of the adjacent regions 29F and 30D (measured by base-pair distances). We identified seven probesets among the 122 spanning 30AB that showed correlations at a level of p<0.05 (Table 6). We identified Ggamma30A (CG3694), involved in G-protein signal transduction and cell cycle regulation as the probeset in the 30AB region with gene expression most strongly correlated with both lead-induced behavioral changes and lead-induced changes in gene expression among those probesets regulated from 30AB. Ggamma30A has human and other mammalian orthologs with similar function, and has been associated in mice with gustation [57].

Table 6.

Candidate genes from 30AB that mediate the behavioral response to lead. We took gene expression data for 122 probesets nearest our behavioral QTL and asked whether or not strain differences in gene expression levels for these, individually, were correlated with the behavioral change induced by lead treatment. There were seven “significant” (e.g. unadjusted for alpha=0.05) correlations. Ggamma30A is represented twice by two different probesets, as indicated by the Affymetrix ID (Affy ID).

| Gene name | Correlation coefficient | P value | Protein function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cks30A (CG3738) | r=−0.266 | P=0.03 | amino acid phosphorylation, cell cycle regulation, histoblast morphogenesis |

| Ggamma30A (CG3694) Affy ID 1637526_S_at |

r=0.328 | P=0.007 | signal transduction via G-protein, visual perception |

| Ggamma30A (CG3694) Affy ID 1628754_S_at |

r=0.31 | P=0.011 | signal transduction via G-protein, visual perception |

| CG3838 | r=0.276 | P=0.024 | DNA binding |

| Nckx30C (CG18660) | r=0.309 | P=0.011 | ion transport: K, Na, Ca; compound eye development |

| CG9525 | r=−0.288 | P=0.018 | no known function |

| CG9573 | r=−0.328 | P=0.007 | protein binding |

Although these cursory analyses for purposes of discussion have not been corrected for multiple comparisons, they illustrate a simple and direct method for correlating functional traits associated with lead exposure to gene expression levels in response to lead as an independent method for screening candidate genes of interest within identified QTL. The combination of gene expression data and data on functional traits in the same RI lines provides a more precise method for a priori screening of candidate loci representing significant QTL than either method alone would allow. This approach should be able to increase the probability of identifying valid candidate loci represented by eQTL to facilitate confirmation by direct genetic methods such as deletion mapping and gene silencing, at least in cases where functional trait QTL are derived from strain differences in traits that are a direct function of strain differences in gene expression.

In the absence of data on functional traits and functionally related gene expression in the same RI lines, a priori identification of candidate genes for a QTL is limited to what is already known about the functions of closely linked loci. In the present case, examining the known, or predicted functions of the 122 genes closely linked to our behavioral QTL reveals one that is a strong candidate based on predicted function (CG3759: “laccase-like”) associated with defense against toxins, iron and copper binding (Flybase). Although gene expression from this probeset is not correlated with the behavioral response to lead, it may represent genetic variation that acts developmentally to mediate behavioral responses to lead at a physiological or anatomical level that does not depend on adult gene expression.

We have also measured variation among these roo lines for lead burden in response to the same lead treatment used here to assay gene expression in response to lead treatments, and have identified three significant QTL for this trait (unpublished) that do not overlap with either the behavioral QTL [53] or the transband eQTL identified here in response to lead treatment. This observation suggests that our transband pattern of gene expression in response to lead is not significantly dependent on strain variation in lead burden, although further analysis of individual probesets may reveal interesting associations.

Systematic analysis of genetic correlations among probesets for gene expression and functional trait expression in response to lead exposure may help identify specific candidate probesets of interest within each of the transband QTLs. Genetic validation of the putative trans-regulators in our transbands is required to authenticate this proposition, but, if validated, it represents a significant change in how to interpret eQTL analyses.

Limitations of genetical genomics studies

There are limitations common to all eQTL studies. For example, previous genetical genomics studies have determined that probeset expression levels are often apparently polarized for expression based on genotype – i.e., probesets of one genotype in the RILs have higher relative expression levels compared with probesets of the other genotype. For example, in studies with BXD mouse RILs, which were made from the C57BL/6J sequenced mouse strain (for which the probes were designed) and the DBA/2J strain, a significantly larger number of the probesets with the C57BL/6J genotype have an apparently higher relative expression level than with the non-sequenced genotype [19]. The apparent polarization of expression based on genotype is now a well-known design flaw of microarray experiments because probes that fail to hybridize to a gene because of a sequence mismatch could be erroneously scored as having lower expression [95]. We controlled for this by eliminating probesets that have “outlier probe(s)” with significantly lower signal(s) than the other probes in the probeset.

Another major limitation of the current genetical genomics study is that if the regulation of a lead-dependent master modulatory gene is identical in the progenitor strains ORE and 2B, then these master regulators would probably not be identified in our analysis. An approach that analyzes gene expression patterns in populations of flies, such as the quantitative-trait transcript technique [88,99], or an eQTL approach that uses more than two progenitor strains [40], will likely identify further GxE-eQTL transbands and lead-dependent master-modulatory genes.

A further limitation of our experimental design is that anatomic alterations are likely induced by either lead or genetics. For example, if some of the flies have a bigger brain (or any other tissue since we analyzed whole flies) then one would find up-regulation of brain (or some other tissue) associated genes. However, this would not necessarily be true if you compare only an equivalent amount of cells from the tissue in question. Therefore, as discussed as a general limitation of microarray design in whole organism studies [20], the observed effect would not be a transcription effect but rather is a function of strain differences occurring on a larger anatomic scale. We and others have observed that the lead concentration that we used causes developmental delays, but these developmental delays are not accompanied by changes in the adult body weight [2]. However, we and others have shown that certain traits such as triglyceride levels and body mass vary considerably in the RILs that we used in our studies [24,31]. Therefore, these caveats should be considered in the interpretation of our data and in similar studies.

Why did we use whole flies for these studies instead of heads or brains? The co-authors extensively discussed this issue before deciding on using whole flies. We thought that starting with whole flies is the best approach because lead has numerous physiological effects throughout the body, and not just in the nervous system. We also believed that lead could have global effects on gene expression in a conserved manner, but the neuronal effects would become manifest only in the nervous system. We also argued that if we decided to analyze only the head (of which over half is brain and eyes, which are also parts of the nervous system), then we might be throwing out interesting gene expression changes that occur in the PNS (e.g., ganglia) and other parts of the body. Futhermore, a criticism of mouse genetical genomics experiments that use whole brains is that smaller regions of the brain would have been preferred. For Drosophila, we believe the next step should be to repeat these studies with fly heads or, even better, specific types of neurons or brain regions by using a purification technique, such as the bacTRAP technique that was developed for purifying mouse Purkinje cells and other neuronal types [35,49,102].

Why did we only do one microarray experiment for each of the 75 RILs in the presence or absence of only one concentration of lead? The most obvious answer is that this would have been prohibitively expensive. However, the great advantage of genetical genomics studies over other types of gene expression studies with microarrays is that the most important unit of replication is the genotype of a particular genome region (ORE or 2B) and not the RIL. Since we performed 150 microarrays, we analyzed gene expression of the ORE genotype ~75 times and of the 2B genotype ~75 times for each region of the genome. Not many studies have run 75 replicate microarray experiments, but we have essentially done so in this study.

What is meant by a “significant” change in gene expression? We decided to go by P value (via two tailed t-test) rather than by absolute change in gene expression (e.g., a minimum 1.5-fold change used by many investigators). The main reason that some other studies use a threshold of 1.5 as being “significant” is that they wish to identify the genes that are likely important in a response, and it can be argued that a change in steady state mRNA levels of only 1.2 is unlikely to cause a significant change in protein levels. However, this is not the case in our studies because we are primarily interested in pathways (i.e., transbands) rather than individual genes, so we believe that “significance” by t-test is a more robust approach. Also, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, since we essentially replicated our studies ~75 times for the genotype of each region of the genome, a 1.2-fold change, which is a typical change in gene expression in a probeset in the transbands, can be very significant.

What is the cost effectiveness of doing genetical genomics in Drosophila versus mice or some other model organism? In general, the smaller the genome, the more powerful the genetical genomic studies can be. For example, genetical genomic studies done with a similar number of RILs in the small-genome organism Saccharomyces cerevisia have mapped cis-eQTL and transbands to the exact polymorphism [32]. Genetical genomics studies in C. elegans, which has a similar genome size as Drosophila melanogaster, can map eQTL to within 5 cM, which corresponds to dozens or hundreds of genes, but further fine-mapping studies can be quickly done to identify the exact polymorphisms responsible [77,97]. Genetical genomics studies have also been done extensively in rats and mice [7,36,70], which have a further 10-to-20-fold increase in genome size, but the precision of these studies is consequently much broader and fine mapping studies are much more difficult. Fortunately, next-generation “cheap sequencing” technologies have begun to enter the genetical-genomics field [11], and these techniques might soon allow these studies to become cost effective in mammalian models for even small laboratories.

Evolution in a toxic environment

Responses to stressors must play a vital role in evolution, and our results provide insights into mechanisms that may be involved. We identified several transbands that might contain master-modulatory proteins that are affected by lead in one genotype but are insensitive to lead in the other genotype. Since we started with only two parental lines, there might be many more such master modulatory proteins in the genome in a population of Drosophila that are similarly evolving. Another question is whether these same master-modulatory proteins uniquely acquired sensitivity to lead, which seems unlikely, or respond in similar manners to many environmental toxins. Toxin-induced changes in the regulation of these proteins might result in the development of a slightly “modified” nervous system that could enhance fitness in a contaminated environment. Consistent with this, lead-induced changes in mating and in fecundity in Drosophila [50] can be interpreted in terms of changes in resource allocation by the female that may, from a long-term perspective, be adaptive. The studies presented here show many promising new avenues for investigation.

There are several practical applications for the data generated in the study. The data will be deposited in the GeneNetwork website (http://www.genenetwork.org) so that other investigators can look for correlations between gene expression patterns and phenotypic traits. The GeneNetwork is an open resource and consists of a set of linked resources for systems genetics. It has been designed for integration of networks of genes, transcripts, and traits such as toxicity, cancer susceptibility, and behavior for several species. Phenotypic QTLs using the roo lines were identified in numerous other QTL mapping studies [46,47,60,69,75,89,114,115]. For sets of phenotypes, particularly those in Gene Network's databases (Drosophila phenotypes are not yet in this database), a variety of correlation analyses can be performed with the gene expression data. Trait values entered by users or retrieved from the databases can be correlated with any other database of phenotypes from the same mapping genetic reference panel, in our case, the roo lines. The future addition of our data and other Drosophila QTL data to GeneNetwork will be a tremendous boon to the Drosophila community and to the genetics community in general.

Materials and Methods

D. melanogaster stocks, growth, and RNA extraction

The 75 Drosophila roo lines were obtained from Trudy Mackay. To avoid batch effects [119], the growth of the flies, the RNA extraction and the order of running the arrays, and the fluidics well used for each array was completely randomized for the 75 lines in two treatments. Control food consisted of standard cornmeal, agar, sugar, yeast, and 250 µM NaAc [4]. Lead-contaminated food consisted of standard food plus 250 µM PbAc (lead exposure at this concentration has been shown to affect locomotion in adults [50]). Flies from each of the 75 roo lines (20 males and 20 females) were placed in a vial with 10 ml of food (control or PbAc) for 3 days at 25°C and allowed to lay eggs; the adults were subsequently discarded. Newly eclosed adult males were placed on the same medium (control or PbAc) as had been present during pre-adult development for 5–10 days before being used as subjects. Male progeny were pooled from each vial (65 males per vial) and frozen at −80°C. RNA samples were extracted in groups of 24 and arrays hybridization run in groups of 4 with 3 groups run per day. Effects of RNA extraction and array hybridizations day were examined by ANOVA and Support Vector approaches and no obvious day effects were observed (data not shown).

RNA extraction and hybridization

Total RNA was isolated following Trizol Manual (Invitrogen Life Technologies) with modifications made by Kevin Bogart and Justen Andrews at Indiana University. Frozen flies (50 mg) were homogenized with Poly Tron (Kinematica AG) in a 5 ml tube with 2 ml of Trizol. The homogenate was incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes followed by centrifuge at 12,000 rcf for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble debris. 1 ml supernatant was transferred to a new centrifuge tube and 0.2 ml chloroform was added. After shaking the tube vigorously by hand for 15 seconds, sample was incubated for 3 minutes at room temperature and then was centrifuged at 10,000 rcf for 15 minutes at 4°C. 0.54 ml aqueous phase was carefully transferred to a fresh RNAse-free tube and 0.45 ml isopropanol was added to each tube followed by vortexing. After 10 minutes incubation at room temperature, sample was centrifuged at 12,000 rcf for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was then removed and the pellet was washed with 1 ml 75% ethanol followed by centrifuge at 7,500 rcf for 5 minutes at 4°C. After the supernatant was removed and the pellet was air dried for 10 minutes at room temperature, the pellet was resuspended in 40 ul Rnase free water at the end. All RNA samples were lead-treated with DNase I in order to get rid of potential DNA contamination. The quality of each RNA sample was determined on 2100 Agilent Bioanalyser before proceeding RNA labeling.

RNA quality was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer. Since Drosophilia generate atypical peaks (18S RNA is absent) the 18S to 28S ratio was not studied, however the bioanalyzer results were used to determine if the RNA extraction was clean. Samples that failed were re-extracted from other flies. The RNA that passed the quality checks were run on the Affymetrix Drosophila genome 2 Array®. This array has 18,952 probesets and each probeset is composed of on average 14 probe pairs with 11 micron feature size.

Quality Control

The images were initially processed with MAS 5.0 for quality control. Multiple quality control steps were used. The images of all arrays were manually inspected for defects. The 3’/5’ ratio of Beta actin was verified as being between 1.5 and 3. The chip to chip Pearson’s correlation was examined (mean correlation < 0.91 to all other arrays set to being poor). The geography Index [63] and a deleted residual [93] approach was also used, and a cutoff of a KS-D of 0.15 was considered poor quality. These steps resulted in 3 arrays being excluded. These were the roo line 54 treated with lead and roo lines 11 and 211 with control treatment. These quality control steps resulted in the eQTL analysis being conducted on 73 control roo lines and 74 lead lines with a total of 72 lines being measured in both treatments.

Expression quantification

The arrays which passed quality control (n=147), were processed as a single group with Bioconductor using the RMA using the “justRMA function” for all studies in this paper.

Markers genotypes

Marker information for a total of the 75 roo lines which were typed for a total of 82 markers. Heterozygotes were set to missing in these lines.

Annotation

The annotation used in this experiment is that provided by Affymetrix’s Netaffx [18,74] for the Drosophila genome 2 array data March 27, 2006. A total of 18,147 probesets had physical genetic positions. 805 probesets without genetic position are included in the table of P values (Table S2 and Table S3), but are excluded from the eQTL figure (Fig. 2a). These 805 probesets without a position, had 7 significant locations in the control flies and 13 for the lead-treated flies.

Number of Replicates

We chose not to use replicates in this study, and instead devoted more resources to more lines. As a result, we were able to obtain measurements on 75 RILs under control conditions and 75 RILs under lead-treated conditions with only one microarray per line per condition (i.e., 150 microarray total analyses). If fewer than 75 RILs are used, or if one studies organisms with larger genomes, such as with the mouse BXD RILs which only have 30–40 commercially available lines [however, see [90]], then duplicate or triplicate microarrays would probably be necessary for each experimental condition to obtain statistically significant results. Also, if “collaborative cross” RILs are used, which were made by crossing multiple mouse inbred lines [22], then many more lines or replicates will be needed to match the power of using 75 RILs in simpler organisms such as yeast, Drosophila or C. elegans. What is important to understand in a genetical genomics experiment is that the unit of replication in the microarray analyses is the RI line and treatments and not the animal or the DNA aliquot. Therefore, if one has a sufficiently large number of RILs and a limited budget, then it is statistically more powerful to analyze more RILs with a single microarray per line than to conduct multiple microarrays on the same RI line.

Analysis

The expression values of the 147 arrays passing quality control were divided into their two groups, lead-treatment and control, with 73 or 74 in each. eQTL analysis was conducted on each of the two groups and then jointly with an interaction term between the treatment and locus (3 total analyses). The R/qtl [15] package was used to map QTL. Probabilities of putative QTL genotypes were computed in the 5 cM interval along the genome. Haley-Knott regression method [48] was used to map the QTL controlling the transcripts. Genome-wise significant level was established by permutation at 0.05 level [23] which corresponds to a P value of 0.0001. Genome wide significance was achieved at 2907 locations in the RMA processing control animals. The 2907 includes probesets that have significant linkage at more than one location in the genome. There were 3467 significant eQTLS in 3017 genes for the RMA processed and lead-treated flies (Figure 1).

Figures 2A and 2B show the heritability estimates for the data. Heritability is calculated in the narrow sense: 1/2Va/(1/2Va+Ve) where Va is the variance due to strain and Ve is the variance due to environment (error) [39]. Supplementary Figure S1a provides the heritability without treatment effects. Mean heritability is 38.7% (y = strain + error). Figure 2B provides the heritability with treatment effects. Mean heritability is 40.6% (y = strain + treatment + error).

Figure 2C shows the P values for all markers (82 markers), and every 5 cM between markers by all expression traits. As can be seen there are more ‘significant’ (P < 0.05) than expected at random. We calculated the conservative Benjamini-Hochberg FDR (1995) for the data, and determined the FDR based on all P values for all marker and trait combinations. As can been seen, at an alpha level of 0.0001, which is extensively used in this paper, the FDR is a bit more than 4% (Supplementary Table S3).

Enrichment Analysis