We have been exploring a strategy for the synthesis of small molecules having properties that increase the probability of success in all facets of probe- and drug-discovery pipelines – including discovery, optimization and manufacturing.[1] This strategy involves: 1) the synthesis of building blocks having functionality suitable for subsequent “coupling” and “pairing” steps, 2) intermolecular coupling reactions that join the building blocks in all stereochemical combinations and 3) intramolecular pairing reactions that join different combinations of functional groups yielding diverse skeletons.[2] Here, we describe a multicomponent coupling reaction that we believe will be well suited for the coupling phase of this strategy since, among others, it yields complex and diverse α-pyrones, which are core elements found in many biologically active compounds.[3]

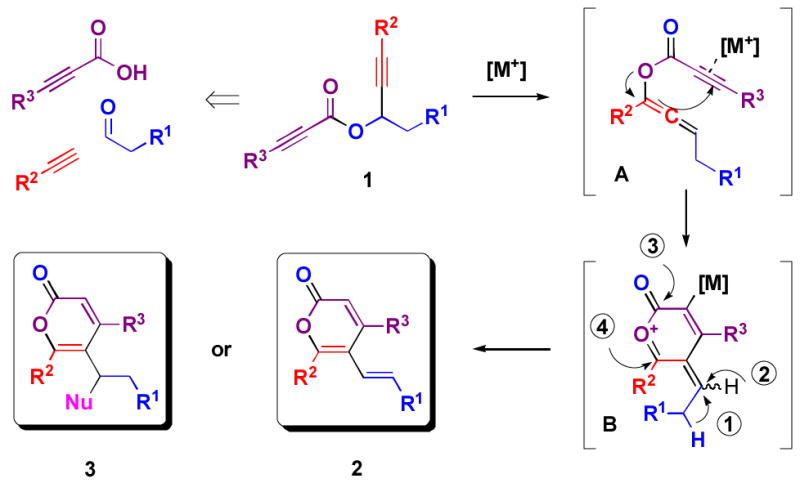

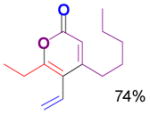

Convergent syntheses[4] of α-pyrones have traditionally involved the lactonization of ketoesters.[5] Transition metal-catalyzed cycloaddition[6] and annulation reactions[7] are recent alternatives that have attracted much attention, but most are limited by the resulting poor regioselectivity or the requirement for harsh reaction conditions. We envisioned that the readily accessible propargyl propiolate 1 could be converted to different products via a cascade process (Figure 1).[8] Late transition-metal catalyzed [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of 1 would generate an enyne allene A.[9] A 6-endo-dig cyclization would be induced by the activation of the alkyne moiety in A to furnish the oxocarbenium intermediate B. In one possible pathway, elimination (➀, Figure 1) would afford a vinyl α-pyrone 2. We anticipated that the intermediate B could also be trapped by a variety of nucleophiles. We hypothesized that we could control the trapping of electrophilic intermediate B, which can in principle be attacked at three distinct sites (➁, ➂ and ➃, Figure 1) by using different nucleophiles and reaction conditions. We describe the successful realization of many of these concepts.

Figure 1.

Syntheses of trisubstituted α-pyrones via transition metal-catalyzed cascade reactions.

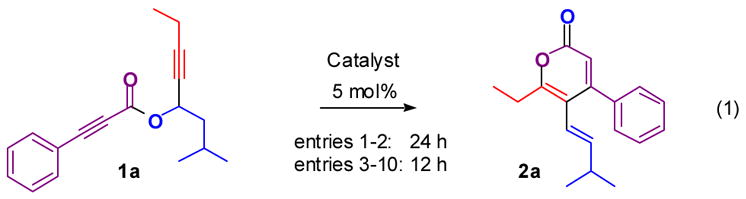

A similar [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement followed by 6-endo-dig cyclization cascade has been reported by Toste and coworkers for the synthesis of aromatic ketones.[9a] Stimulated by this result, we attempted to use the reported silver(I) catalysts to achieve the rearrangement of 1a (Table 1, entry 1). The desired vinyl α-pyrone 2a, however, was obtained in low yield. In contrast, the widely used cationic Au(I) catalyst (entry 2)[10] at room temperature provided 2a in 61% yield. At higher temperatures, 2a was obtained in 81% yield (entry 3) while a comparison experiment using only 5% AgSbF6 afforded a low yield of 2a (entry 4). Increasing the temperature in 1,2-dichloroethane led to a decreased yield (entry 5). 10% pyridine was added in hope of accelerating the elimination pathway (entry 6), but this resulted instead in the inhibition of the reaction, presumably by inactivation of the cationic gold catalyst by pyridine coordination.[11] Polar or coordinating solvents decreased the reaction efficiency and acetonitrile inhibited the reaction (supporting information).[10b] The reaction mixture converted to a gel when THF was used as the solvent (entry 7), presumably due to the polymerization of THF induced by reactive cationic species.[12] Three other Au(I) species were tested (entries 8–10), but none was superior to [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgSbF6 used in the model reaction.

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions for the rearrangement of 1a into 2a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Conditions | Yield [%]a | |

| 1a | 2a | |||

| 1 | AgSbF6b | CH2Cl2, RT | 95 | trace |

| 2 | [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgSbF6 | CH2Cl2, RT | 0 | 61 |

| 3 | [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgSbF6 | CH2Cl2, reflux | 0 | 81 |

| 4 | AgSbF6 | CH2Cl2, reflux | 25 | 11 |

| 5 | [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgSbF6 | 1,2-DCE, 60°C | 0 | 67 |

| 6 | [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgSbF6c | CH2Cl2, RT | 96 | 0 |

| 7 | [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgSbF6 | THF, 40°C | -- | --d |

| 8 | [(Ph3PAu)3O]BF4e | CH2Cl2, reflux | 95 | 0 |

| 9 | [(Ph3P)AuNTf2] | CH2Cl2, reflux | 0 | 45 |

| 10 | [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgOTf | CH2Cl2, reflux | 0 | 48 |

Isolated yields after column chromatography.

2 mol % PPh3, 1.5 equiv. MgO as additive.

10 mol % pyridine as additive.

The reaction mixture became vigorous and solidified.

2 mol % catalyst.

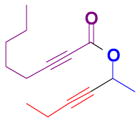

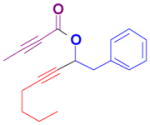

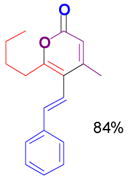

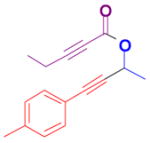

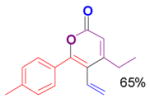

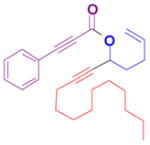

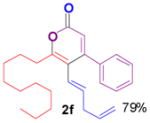

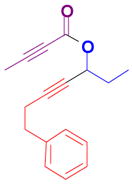

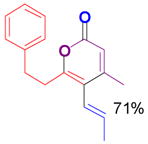

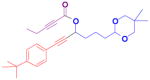

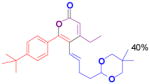

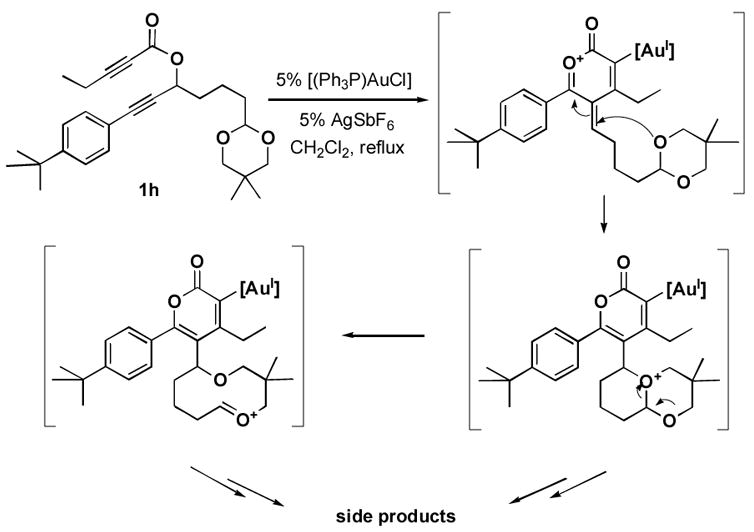

The rearrangement of propargyl propiolates 1b–1f gave the desired vinyl α-pyrones 2b–2g in 65–84% yields (Table 2). We note that the olefin moiety in 1f did not interfere with the cascade reaction despite the precedent of reactions involving 1,6-enynes.[10b,13] Substrate 1h resulted in a less efficient reaction, yielding 2h in only 40% yield, likely due to an intramolecular attack of the cationic intermediate by the ketal oxygen.[14]

Table 2.

Gold(I)-catalyzed rearrangement of propargyl propiolates to vinyl α-pyronesa

| Substrate | Product | Substrate | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

1b |

2b |

1c |

2c |

1d` |

2d |

1e |

2e |

1f |

2f |

1g |

2g |

1h |

2h |

||

Reaction conditions: propargyl propiolate (0.05 M), [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgSbF6 (5 mol %), CH2Cl2, reflux, 12 h.

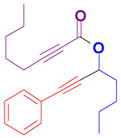

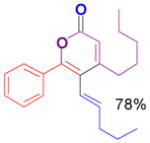

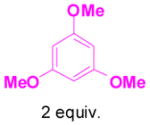

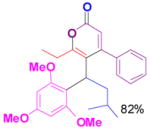

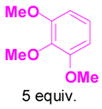

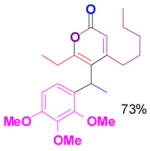

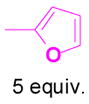

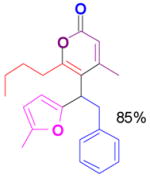

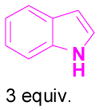

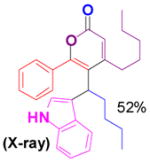

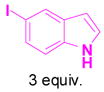

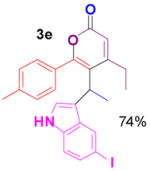

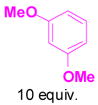

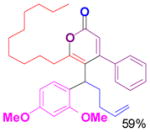

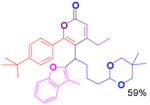

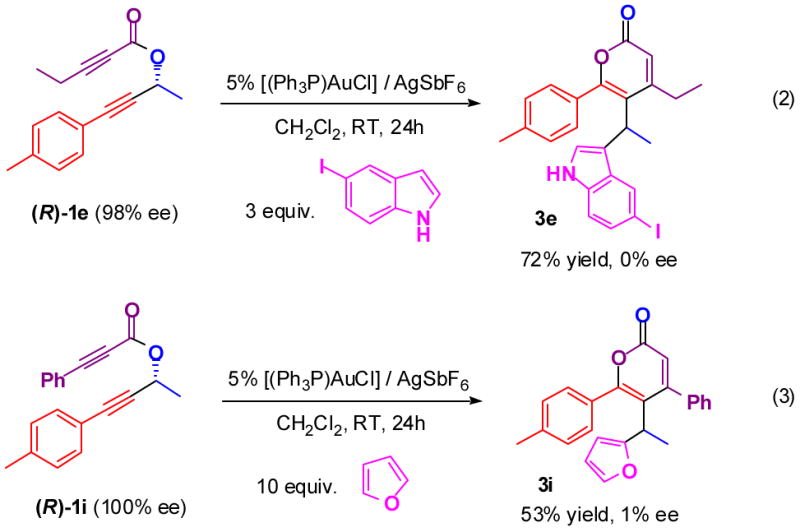

We have also determined that the cationic intermediate B can be trapped by electron-rich arenes and heteroarenes in a Friedel-Crafts-type reaction. Performing the model reaction with 5 mol % [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgSbF6 at room temperature in the presence of 2 equivalents of trimethoxybenzene afforded the α-pyrone 3a in 82% yield (Table 3). None of the rearrangement product 2a, or the products resulting from the nucleophilic attack at the other two positions (➂ and ➃, Figure 1) was observed. The addition of the aromatic ring to the alkyne[15] does not interfere with the tandem reaction. 3a was not detected when α-pyrone 2a was subjected to the reaction conditions, indicating that 2a is not an intermediate in the formation of 3a. Electron-rich aromatics and heteroaromatics, such as indole, furan and benzofuran, are also suitable nucleophiles in the Friedel-Crafts-type reaction, affording 3b–3h in 59–85% yields (Table 3). We note that 3a–3h mimic the structure motif of diarylmethanes, which have a broad spectrum of biological activities.[16] The structure of 3d was verified by X-ray analysis.[17]

Table 3.

Gold(I)-catalyzed syntheses of trisubstituted α-pyrones from propargyl propiolatesa

| Substrate/Nu | Product | Substrate/Nu | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

1a+ |

3a |

1b+ |

3b |

1c+ |

3c |

1d+ |

3d |

1e+ |

3e |

1f+ |

3f |

1g+ |

3g |

1h+ |

3h |

Reaction conditions: propargyl propiolate (0.05 M), nucleophile, [(Ph3P)AuCl]/AgSbF6 (5 mol %), CH2Cl2, room temperature, 24 h.

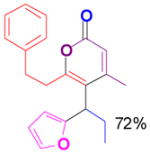

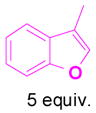

When the enantiopure propargyl propiolates (R)-1e and (R)-1i were subjected to the same reaction conditions in the presence of electron-rich heteroarenes, racemates of 3e and 3i were obtained (Figure 2). This result suggests that the nucleophile bonds to both enantiofaces of the oxocarbenium B with equal facility (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Racemic products result from non-racemic propargyl propiolates.

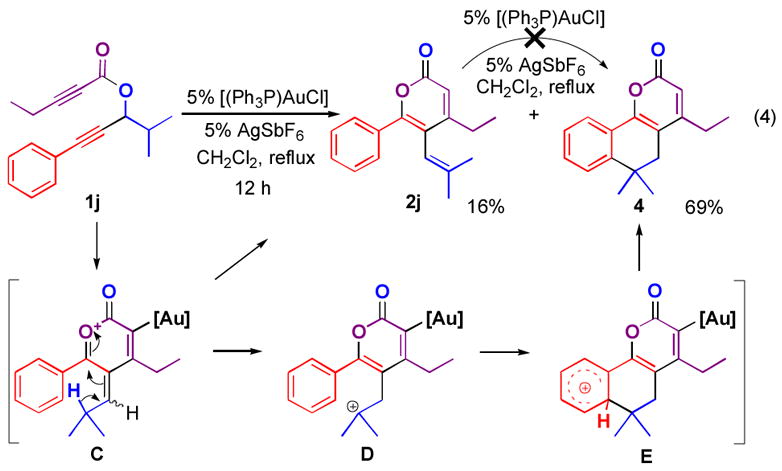

When 1j was subjected to the reaction conditions, tri-substituted α-pyrone 2j was obtained in only 16% yield, while the major product, tricyclic compound 4, was obtained in 69% yield (Figure 3). Since 2j was not converted into 4 when resubjected to the same conditions, 4 apparently results from a 1,2-hydride shift in intermediate C, yielding tertiary carbocation D, which is trapped by the phenyl group in an intramolecular Friedel-Crafts reaction.[18]

Figure 3.

Cascade process yielding a tricyclic α-pyrone.

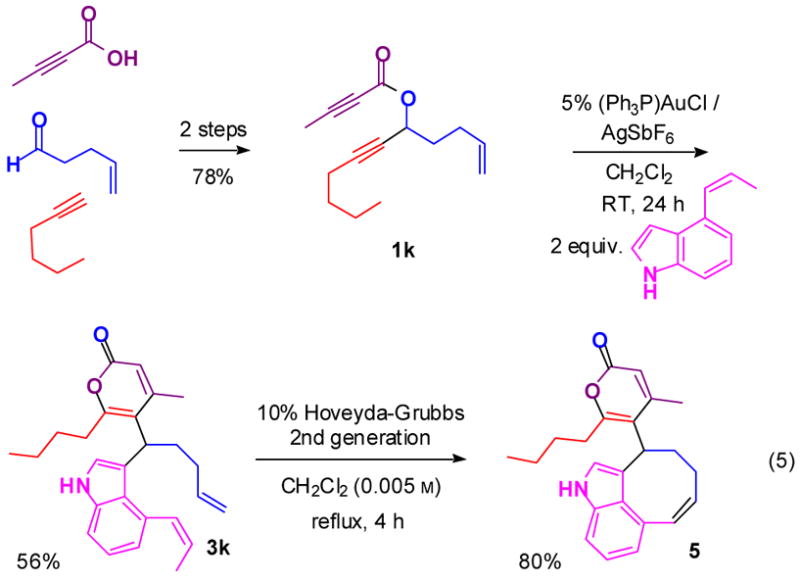

Considering that the propargyl propiolates used in these multicomponent coupling reactions can be readily synthesized from terminal alkynes and aldehydes, which are among the most highly varied and abundant building blocks, we anticipate that this coupling reaction will be well suited for the strategy noted in the Introduction. Two additional observations reinforce this expectation. Our preliminary studies suggest that trapping the intermediate oxocarbenium ion with alcohol-based nucleophiles results in attack at the lactone carbonyl carbon, resulting in an alternative skeleton (manuscript in preparation). Secondly, strategic placement of suitable functionality in the building blocks allows functional group-pairing reactions that enable further skeletal diversification. To illustrate, coupling product 3k undergoes a ring-closing metathesis to yield the polycyclic α-pyrone 5 (Figure 4). We are currently exploring the potential of these reaction processes in diversity syntheses and determining the assay performance of the resulting products using many small-molecule screens.

Figure 4.

Intramolecular functional group-pairing reaction involving substituents attached to distinct building blocks prior to the intermolecular coupling reaction (c.f., “Build/Couple/Pair strategy”[2]).

Supplementary Material

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Footnotes

The NIGMS-sponsored Center of Excellence in Chemical Methodology and Library Design (Broad Institute CMLD) enabled this research. We thank Ben Stanton, Arturo Vegas and Drs. Weiping Tang, Thomas Nielsen and Xiang Wang for helpful discussions. T. L. thanks Chris Johnson at Broad Institute for the help with SFC/MS. S.L.S. is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

We dedicate this paper with admiration and affection to Professor Yoshito Kishi on the occasion of his 70th birthday

References

- 1.For examples, see: Kumagai N, Muncipinto G, Schreiber SL. Angew Chem. 2006;118:3717–3720. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600497.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3635–3638. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600497.Spiegel DA, Schroeder FC, Duvall JR, Schreiber SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14766–14767. doi: 10.1021/ja065724a.

- 2.Nielsen TE, Schreiber SL. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Dickinson JM. Nat Prod Rep. 1993;10:71–98. doi: 10.1039/np9931000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Steyn PS, van Heerden FR. Nat Prod Rep. 1998;15:397–413. doi: 10.1039/a815397y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) McGlacken GP, Fairlamb IJ. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:369–385. doi: 10.1039/b416651p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Salomon CE, Magarvey NA, Sherman DH. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:105–121. doi: 10.1039/b301384g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) van Raaij MJ, Abrahams JP, Leslie AG, Walker JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6913–6917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Wu PL, Hsu YL, Wu TS, Bastow KF, Lee KH. Org Lett. 2006;8:5207–5210. doi: 10.1021/ol061873m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Clark BR, Capon RJ, Lacey E, Tennant S, Gill JH. Org Lett. 2006;8:701–704. doi: 10.1021/ol052880y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Lee JC, Lobkovsky E, Pliam NB, Strobel G, Clardy J. J Org Chem. 1995;60:7076–7077. [Google Scholar]; i) Thaisrivongs S, Janakiraman MN, Chong KT, Tomich PK, Dolak LA, Turner SR, Strohbach JW, Lynn JC, Horng MM, Hinshaw RR, Watenpaugh KD. J Med Chem. 1996;39:2400–2410. doi: 10.1021/jm950888f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke MD, Schreiber SL. Angew Chem. 2004;116:48–60. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:46–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Jung ME, Hagenah JA. J Org Chem. 1987;52:1889–1902. [Google Scholar]; b) Dieter RK, Fishpaugh JR. J Org Chem. 1988;53:2031–2046. [Google Scholar]; c) Douglas CJ, Sklenicka HM, Shen HC, Mathias DS, Degen SJ, Golding GM, Morgan CD, Shih RA, Mueller KL, Scurer LM, Johnson EW, Hsung RP. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:13683–13696. [Google Scholar]; d) Ma S, Yu S, Yin S. J Org Chem. 2003;68:8996–9002. doi: 10.1021/jo034633i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hachiya I, Shibuya H, Shimizu M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:2061–2063. [Google Scholar]; f) Gilbreath SG, Harris CM, Harris TM. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:6172–6179. doi: 10.1021/ja00226a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Fukuyama T, Higashibeppu Y, Yamaura R, Ryu I. Org Lett. 2007;9:587–589. doi: 10.1021/ol062807n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kishimoto Y, Mitani I. Synlett. 2005:2141–2146. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Hua R, Tanaka M. New J Chem. 2001;25:179–184. [Google Scholar]; b) Larock RC, Doty MJ, Han X. J Org Chem. 1999;64:8770–8779. doi: 10.1021/jo9821628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For reviews, see: Tietze LF. Chem Rev. 1996;96:115–136. doi: 10.1021/cr950027e.Parsons PJ, Penkett CS, Shell AJ. Chem Rev. 1996;96:195–206. doi: 10.1021/cr950023+.Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:1619–1665.Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2143–2173.Padwa A, Bur SK. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:5341–5378. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.158.

- 9.a) Zhao J, Hughes CO, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7436–7437. doi: 10.1021/ja061942s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang S, Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8414–8415. doi: 10.1021/ja062777j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sromek AW, Kel’in AV, Gevorgyan V. Angew Chem. 2004;116:2330–2332. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2280–2282. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Shigemasa Y, Yasui M, Ohrai S, Sasaki M, Sashiwa H, Saimoto H. J Org Chem. 1991;56:910–912. [Google Scholar]; e) Cariou K, Mainetti E, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:9745–9755. [Google Scholar]; (f) Yu M, Zhang G, Zhang L. Org Lett. 2007;9:2147–2150. doi: 10.1021/ol070637o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For recent applications, see: Zhang L, Wang S. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1442–1443. doi: 10.1021/ja057327q.Toullec PY, Genin E, Leseurre L, Genêt JP, Michelet V. Angew Chem. 2006;118:7587–7590. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601980.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:7427–7430. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601980.Park S, Lee D. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10664–10665. doi: 10.1021/ja062560p.Gorin DJ, Dubé P, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14480–14481. doi: 10.1021/ja066694e.Lian JJ, Chen PC, Lin YP, Ting HC, Liu RS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11372–11373. doi: 10.1021/ja0643826.Lee JH, Toste FD. Angew Chem. 2007;119:930–932.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:912–914. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604006.Lin CC, Teng TM, Odedra A, Liu RS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3798–3799. doi: 10.1021/ja069171f.Gorin DJ, Toste FD. Nature. 2007;446:395–403. doi: 10.1038/nature05592.

- 11.Thwaite SE, Schier A, Schmidbaur H. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2004;357:1549–1557. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi S, Morikawa K, Saegusa T. Macromolecules. 1975;8:386–390. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Nieto-Oberhuber C, Muñoz MP, Buñuel E, Nevado C, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Angew Chem. 2004;116:2456–2460. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2402–2406. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nevado C, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:2627–2635. doi: 10.1002/chem.200204646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) López S, Herrero-Gómez E, Pérez-Galán P, Nieto-Oberhuber C, Echavarren AM. Angew Chem. 2006;118:6175–6178. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:6029–6032. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Nieto-Oberhuber C, López S, Muñoz MP, Cárdenas DJ, Buñuel E, Nevado C, Echavarren AM. Angew Chem. 2005;117:6302–6304. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:6146–6148. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Mézailles N, Ricard L, Gagosz F. Org Lett. 2005;7:4133–4136. doi: 10.1021/ol0515917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Lee SI, Kim SM, Choi MR, Kim SY, Chung YK, Han WS, Kang SO. J Org Chem. 2006;71:9366–9372. doi: 10.1021/jo061254r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

14.A possible pathway for additional reaction products is:

- 15.a) Ferrer C, Echavarren AM. Angew Chem. 2006;118:1123–1127. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1105–1109. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ferrer C, Amijs CHM, Echavarren AM. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:1358–1373. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Reetz MT, Sommer K. Eur J Org Chem. 2003:3485–3496. [Google Scholar]; d Shi Z, He C. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3669–3671. doi: 10.1021/jo0497353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Singh MM. Med Res Rev. 2001;21:302–347. doi: 10.1002/med.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Long YQ, Jiang XH, Dayam R, Sanchez T, Shoemaker R, Sei S, Neamati N. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2561–2573. doi: 10.1021/jm030559k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hsin LW, Dersch CM, Baumann MH, Stafford D, Glowa JR, Rothman RB, Jacobson AE, Rice KC. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1321–1329. doi: 10.1021/jm010430f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CCDC-650319 (3d) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. See the Supporting Information for further details.

- 18.a) Nieto-Oberhuber C, López S, Echavarren AM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6178–6179. doi: 10.1021/ja042257t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Harrison TJ, Patrick BO, Dake GR. Org Lett. 2007;9:367–370. doi: 10.1021/ol062939g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.