Introduction

Comparative sequence analysis suggests that the ydaF gene encodes a protein (YdaF) that functions as an N-acetyltransferase, more specifically, a ribosomal N-acetyltransferase. Sequence analysis using basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) suggests that YdaF belongs to a large family of proteins (199 proteins found in 88 unique species of bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes). YdaF also belongs to the COG1670,1 which includes the Escherichia coli RimL protein that is known to acetylate ribosomal protein L12. N-acetylation (NAT) has been found in all kingdoms.2 NAT enzymes catalyze the transfer of an acetyl group from acetyl-CoA (AcCoA) to a primary amino group. For example, NATs can acetylate the N-terminal α-amino group, the ε-amino group of lysine residues, aminoglycoside antibiotics, spermine/speridine, or arylalkylamines such as serotonin.3

The crystal structure of the alleged ribosomal NAT protein, YdaF, from Bacillus subtilis presented here was determined as a part of the Midwest Center for Structural Genomics. The structure maintains the conserved tertiary structure of other known NATs and a high sequence similarity in the presumed AcCoA binding pocket3–6 in spite of a very low overall level of sequence identity to other NATs of known structure.

Experimental

B. subtilis acetyltransferase YdaF protein preparation was performed following procedures described previously.7 The open reading frame of B. subtilis YdaF protein was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from E.coli DH 5α genomic DNA. The gene was cloned into the pMCSG78 using a modified ligation-independent cloning protocol.9 This process generated an expression clone producing a fusion protein with a N-terminal His6 tag and a Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease recognition site (ENLYFQ↓S). The fusion protein was overproduced in E. coli BL21-derivative harboring a plasmid encoding three rare E. coli tRNAs [Arg (AGG/AGA) and Ile (ATA)].

The purification procedure used buffers containing 50 mMN-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 10, 20, and 250 mM imidazole for the binding, wash, and elution buffers, respectively. The cells were lysed by sonication after adding fresh lysozyme at 1 mg/mL of final concentration in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation and passed through a pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA column (QIAGEN), and the bound protein was removed with elution buffer. The His6-tag was removed by cleavage with recombinant His-tagged TEV protease. The cleaved protein was then resolved from the His-tag and His-tagged TEV protease by passing the mixture through a second Ni2+-column. The sample buffer was exchanged into 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.6, 2mM dithiothreitol (DTT) using a PD-10 column (Amersham Biosciences) for the crystallization experiments.

The molecular weight of the protein in solution was determined by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex-200 10/30 column (Amersham Biosciences) calibrated with ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), and albumin (67 kDa) as standards. The calibration curve of Kav versus log molecular weight was prepared using the equation: Kav = (Ve – Vo)/(Vt – Vo), where Ve = elution volume for the protein, Vo = column void volume, and Vt = total bed volume.

Diffraction-quality crystals of selenomethionine (SeMet)-derivitized YdaF protein were grown at 22°C using vapor diffusion in hanging drops. The crystallization drops consisted of 2 μL of the protein at 8 mg/mL mixed with 2 μL reservoir solution of 10% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 6K, Na/KPO4 pH 6.0, NaCl 0.1M. Crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen with crystallization buffer plus 25% sucrose as cryoprotectant before data collection. The crystals are monoclinic, space group P21 (refer to Table I for complete details).

TABLE I.

Summary of YdaF Crystal Data, MAD Data Collection, and Refinement

| Unit cell parameters (angstroms, degrees) | a = 59.339 Å, b = 134.185 Å, c = 91.062 Å, α = γ = 90, β = 104.08 | ||

| Space group | P21 (num 4) | ||

| Molecular weight [183 residues (SeMet)] | 21,045 Da | ||

| Molecules per asymmetric unit (a.u.) | 6 | ||

| Selenomethionine residues per a.u. | 18 | ||

| MAD data | Edge Energy | Peak Energy | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9791 | 0.9792 | |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 3.1 | 3.0 | |

| Number unique reflections | 48,725 | 53,738 | |

| Overall data completeness (%) | 100.0 | 99.4 | |

| Overall data redundancy | 2.40 | 3.76 | |

| Overall Rmerge (%) | 10.2 | 8.6 | |

| Figure of merit (FOM) | 45.20 | ||

| Phasing power | 1.31 | 2.65 | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20.0–2.7 | ||

| Number of reflections (all) | 37,877 | ||

| Number of reflections (observed) | 36,669 | ||

| Percent reflections observed | 96.8 | ||

| σ Cutoff | 0.0 | ||

| Overall R-value (%) | 0.2468 | ||

| Free R-value (%) | 0.2855 | ||

| RMS deviations from ideal geometry | |||

| Bond length | 0.021 | ||

| Angle | 2.337 | ||

| Dihedral | 21.101 | ||

| Number of: | |||

| Protein non-hydrogen atoms | 8,614 | ||

| Water molecules | 19 | ||

| Chloride ions | 6 | ||

| Mean B-factor (Å2) | 30.7 | ||

| Ramachandran plot statistics (%) | |||

| Residues in most favored regions | 92.5 | ||

| Residues in additional allowed regions | 7.1 | ||

| Residues in generously allowed regions | 0.4 | ||

| Residues in disallowed region | 0.0 | ||

A two-wavelength multiple-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) data set was collected for the peak and edge energies, as determined from a fluorescence scan of a crystal containing SeMet-labeled YdaF protein. The data were processed with HKL2000 and the substructure was determined using the MAD method in SOLVE.10 This initial step was administered within the Automated Crystallographic System (ACrS).11 The resulting initial model was 48% complete. The substructure solution was then used to phase the structure within AutoSHARP, utilizing the Baysian statistical approach in SHARP.12 The resulting phases and refined substructure were submitted for density modification, phase extension, non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging, and auto tracing with RESOLVE,13–15 and the resulting initial model included 68% of the polypeptide chain.

Final refinement was completed with REFMAC16 using 24 translation, libration, and screw rotation tensor (TLS) groups17,18 in combination with restrained maximum-likelihood refinement. Manual model building was done using Quanta.19 Crystal characteristics, data collection, structure solution, and refinement statistics are shown in Table I.

Results and Discussion

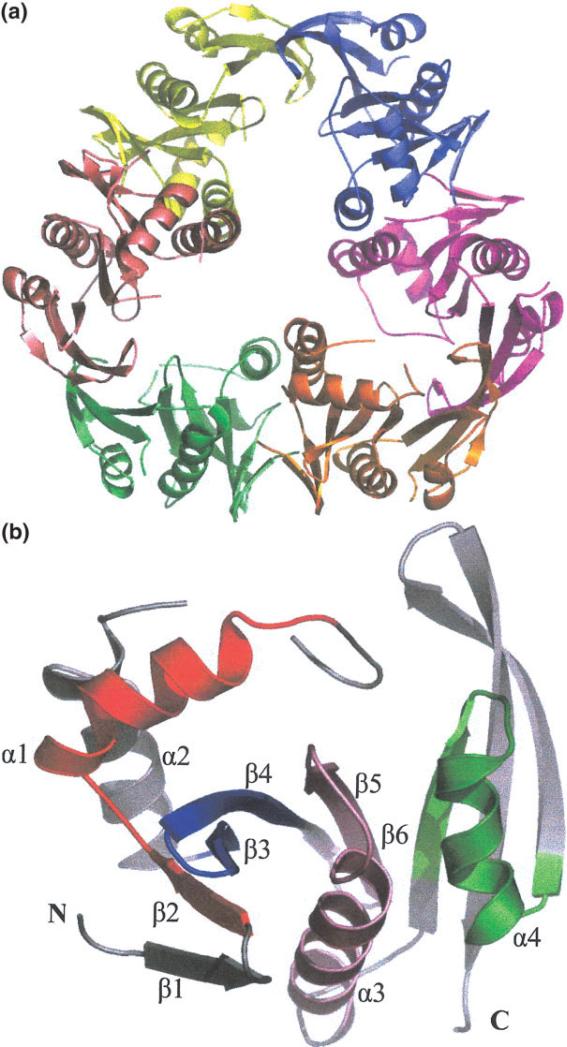

The crystal structure of YdaF protein reveals a hexameric unit with 32 symmetry [Fig. 1(a)]. This is consistent with the results of size exclusion chromatography that suggests the protein is a mixture of dimers and hexamers. The observed molecular weight of dimer is 48.8 kDa (expected 42.1 kDa) and molecular weight of hexamer is 128.3 kDa (expected 126.3 kDa). The ratio of dimer to hexamer observed under the conditions of the size exclusion chromatography experiment was 3:2. The crystal structure and solution measurements suggest YdaF is a trimer of dimers.

Fig. 1.

(a) Quaternary structure of YdaF hexamer. View approximately along 3-fold axis, with each of the monomer units represented in a different color. (b) YdaF monomer secondary structure is labeled α for α-helix and β for β-sheet from N- to C- terminus. Motifs A–D of acetyl transferase domain are color coded: pink (motif A), green (motif B), red (motif C), and blue (motif D).Figure generated using Pymol.23

The monomer unit is a α/β fold characteristic of acetyl transferase domain. The main β-sheet that runs antiparallel (β2–β5) with α-helices α1 and α2 to the left side of the β-sheet, α-helix α3 is cupped within the curved face of the main sheet and helix α4 is to the right of helix α3, which forms a cleft [Fig. 1(b)]. Structural comparisons were conducted via the DALI server20 and the top results were for other NATs with probability z scores as high as 12, although the sequence homology was only 14%. Upon examination of these similar structures, it was determined that the conserved motifs A–D were also present in the YdaF structure. Motifs A and B have been identified as the putative AcCoA binding site in the other NAT structures.3–6,21,22 Despite the overall low sequence similarity, this region of YdaF appears to exhibit both sequence and structural conservation. Superpositions of the structures found in the DALI search showed low deviation in the core region and higher deviations in the relative positions of helices α1 and α2.

COG1670 is functionally described as an N-acetyltransferase and related to the rimL gene, which encodes a ribosomal N-acetyltransferase that acetylates the ribosomal protein L12 to form L7 on the large ribosomal subunit. YdaF is a member of this COG. The sequence identity between YdaF and RimL is 29%, with 54% of the residues similar. The putative AcCoA binding site of RimL, motifs A and B have 66% and 55% sequence similarity, respectively. It is suspected that YdaF is the B. subtilis homologue of RimL.

Acknowledgments

Atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), with PDB-ID 1NSL. We wish to thank all members of the Structural Biology Center at Argonne National Laboratory for their help in conducting these experiments. This work was supported by the Protein Structure Initiative, NIH grant GM-62414 and JSB was partially supported by American Cancer Society fellowship GMC-98219.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polevoda B, Sherman F. N-terminal acetyltransferases and sequence requirements for N- terminal acetylation of eukaryotic proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:595–622. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus-Hill ML, Dutnall RN, Tafrov ST, Sternglanz R, Ramakrishnan V. Crystal structure of the histone acetyltransferase Hpa2: a tetrameric member of the Gcn5-related N-acetyltransferase superfamily. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1311–1325. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clements A, Rojas JR, Trievel RC, Wang L, Berger SL, Marmorstein R. Crystal structure of the histone acetyltransferase domain of the human PCAF transcriptional regulator bound to coenzyme A. EMBO J. 1999;18:3521–3532. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rojas JR, Trievel RC, Zhou J, Mo Y, Li X, Berger SL, Allis CD, Marmorstein R. Structure of Tetrahymena GCN5 bound to coenzyme A and a histone H3 peptide. Nature. 1999;401:93–98. doi: 10.1038/43487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trievel RC, Rojas JR, Sterner DE, Venkataramani RN, Wang L, Zhou J, Allis CD, Berger SL, Marmorstein R. Crystal structure and mechanism of histone acetylation of the yeast GCN5 transcriptional coactivator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8931–8936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8931. [comment] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang RG, Skarina T, Katz JE, Beasley S, Khachatryan A, Vyas S, Arrowsmith CH, Clarke S, Edwards A, Joachimiak A, Savchenko A. Structure of Thermotoga maritima stationary phase survival protein SurE: a novel acid phosphatase. Structure. 2001;9:1095–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00675-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stols L, Gu M, Dieckman L, Raffen R, Collart FR, Donnelly MI. A new vector for high-throughput, ligation-independent cloning encoding a tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site. Protein Expres Purif. 2002;25:8–15. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dieckman L, Gu M, Stols L, Donnelly MI, Collart FR. High throughput methods for gene cloning and expression. Protein Expres Purif. 2002;25:1–7. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunzelle JS, Shafaee JP, Yang X, Weigand S, Renz Z, Anderson WF. Automated crystallographic system for high-throughput protein structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;D59:1138–1144. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903008199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Fortelle E, Bricogne G. Maximum-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement for multiple isomorphous replacement and multiwavelength anomalous diffraction methods. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:472–494. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terwilliger TC. Reciprocal-space solvent flattening. Acta Crystal-logr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:1863–1871. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Discrimination of solvent from protein regions in native Fouriers as a means of evaluating heavy-atom solutions in the MIR and MAD methods. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:501–505. doi: 10.1107/S0907444998012657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terwilliger TC. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schomaker V, Trueblood KN. On rigid-body motion of molecules in crystals. Acta Crystallogr B. 1968;24:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schomaker V, Trueblood KN. Correlation of internal torsional motion with overall molecular motion in crystals. Acta Crystallogr B. 1998;54:507–514. [Google Scholar]

- 19.QUANTA . Molecular Simulations, Inc.; San Diego: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holm L, Sander C. The FSSP database of structurally aligned protein fold families. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3600–3609. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickman AB, Namboodiri MA, Klein DC, Dyda F. The structural basis of ordered substrate binding by serotonin N-acetyltransferase: enzyme complex at 1.8 Å resolution with a bisubstrate analog. Cell. 1999;97:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peneff C, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Bourne Y. The crystal structures of Apo and complexed Saccharomyces cerevisiae GNA1 shed light on the catalytic mechanism of an amino-sugar N-acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16328–16334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeLano WL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system,Version 0.88. DeLano Scientific LLC; San Carlos, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]