Abstract.

The MDR superfamily with ~350-residue subunits contains the classical liver alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), quinone reductase, leukotriene B4 dehydrogenase and many more forms. ADH is a dimeric zinc metalloprotein and occurs as five different classes in humans, resulting from gene duplications during vertebrate evolution, the first one traced to ~500 MYA (million years ago) from an ancestral formaldehyde dehydrogenase line. Like many duplications at that time, it correlates with enzymogenesis of new activities, contributing to conditions for emergence of vertebrate land life from osseous fish. The speed of changes correlates with function, as do differential evolutionary patterns in separate segments. Subsequent recognitions now define at least 40 human MDR members in the Uniprot database (corresponding to 25 genes when excluding close homologues), and in all species at least 10888 entries. Overall, variability is large, but like for many dehydrogenases, subdivided into constant and variable forms, corresponding to household and emerging enzyme activities, respectively. This review covers basic facts and describes eight large MDR families and nine smaller families. Combined, they have specific substrates in metabolic pathways, some with wide substrate specificity, and several with little known functions.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary material is available in the online version of this article at springerlink.com (doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8587-z) and is accessible for authorized users.

Keywords. Dehydrogenases, reductases, enzyme superfamily, evolution, bioinformatics

Introduction

The superfamily of MDR (medium-chain dehydrogenase/reductase) proteins is formed by zinc-dependent ADHs (alcohol dehydrogenases), quionone reductases, leukotriene B4 dehydrogenase, and many more families. The family has grown considerably in recent years, and as of October 2007 it had close to 11 000 members in the Uniprot database [1]. Disregarding species variations, there is still considerable multiplicity, with at least 25 members in humans, excluding close homologues. Compared to an investigation five years ago [2], the total number of known MDR members in all species has increased about 10-fold. Roughly half of the MDR proteins can be grouped into large families with hundreds of members, while about 1000 forms belong to small clusters with 10 or fewer members each. Thus, the MDR superfamily is now showing a spread resembling the complexity of the SDR (short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase) superfamily [3]. This is a new characteristic of MDR, not detectable until now when many data from large-scale genome projects exist.

The first-characterised member was the class I type of mammalian ADH, for which the primary structure was reported already in 1970 [4]. Subsequently detected MDR members included sorbitol DH [5], a crystallin, metabolic enzymes and a synaptic protein [6]. The latter report also coined the term MDR [6] to distinguish this protein family from that of SDR with its typically smaller (∼250 residue) subunits and no metal dependence [7]. This split between two protein types, giving rise to a basic multiplicity of many activities, was seen already in the 1970s when the first data on Drosophila ADH showed subunit patterns separate from those of the Zn-dependent ADHs [8]. In parallel with these family distinctions deduced from whole-subunit similarities, the distribution of domain similarities, and the ancestral nucleotide binding units discerned from three-dimensional data [9–11] led to a number of repeated sequence similarities, also seen early [12] within this whole class of DHs/reductases/kinases in general.

The MDR proteins typically consist of two domains, where the C-terminal domain is coenzyme-binding with the ubiquitous Rossmann fold [10] of an often six-stranded parallel β-sheet sandwiched between α-helices on each side. The N-terminal domain is substrate binding with a core of antiparallel β-strands and surface-positioned α-helices, showing distant homology with the GroES structure [13]. The domains are separated by a cleft containing a deep pocket which accommodates the cofactor and the active site.

In this report, we review the different MDR families, observe common characteristics of the members and emphasise evolutionary aspects of this superfamily.

Divergence within the MDR superfamily

Presently, there are 10888 members of the MDR superfamily, as judged from Uniprot entries, which contain the Pfam [14] domains PF00107 (zinc-binding DH) and PF08240 (alcohol DH GroES-like domain). A number of MDR members are multi-proteins, and some Uniprot entries contain multiple proteins. Therefore, we decided to focus only on the MDR units for the subsequent comparisons. From the 10 888 MDR members, we could extract 9756 MDR proteins, excluding partial sequences shorter than 250 amino acid residues. In order to get an overview of the relationships within this large superfamily, we have clustered and counted the proteins at different identity levels; i.e. at each level the MDR proteins are redundancy-reduced so that all sequences have pairwise identities below the threshold of that level (Table 1).

Table 1.

MDR members in Uniprot as of October 2007 in total and at various redundancy-reduction levels.

| Level | MDR domains |

|---|---|

| Total | 9756 |

| 99% | 7982 |

| 90% | 6593 |

| 60% | 3005 |

| 30% | 476 |

The numbers represent MDR domains.

We then notice a substantial decrease in number already at the 99% identity level, where about 20% of all characterised MDRs are eliminated, representing closely related forms or duplicates. At the 90% level, we find about two-third of all members. At the 30% identity level, we find 476 members, corresponding to about 5% of the total number. Here we will in most cases find only one representative for each MDR family, and we can therefore estimate the total number of MDR families to be around 500. Of these families, we find that only 8 have 200 or more members, and therefore are the most widespread of the MDR proteins. Together they represent 3165 proteins in the database, corresponding to about a third of all MDR forms characterised. The majority of sequence clusters (334 families) presently have 10 or fewer members.

MDR families

The MDR superfamily can be divided into separate families, based upon sequence similarities. For each of the 8 families corresponding to the most widespread forms, we have derived a hidden Markov model (HMM, [15]) which can be used for subsequent database searches in order to find further members. We have created additional HMMs for some MDR families of special interest, for instance those with representatives from the human species. The number of currently detected members for each of these MDR families is shown in Table 2. The largest MDR families are currently the ADH and CAD (cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase) families. However, the description in this review reflects the current situation, and as future genome projects and environmental sequencing projects (e.g. [16]) will contribute to an immense increase of structural information, the number of MDR forms and their family sizes are also expected to increase. It should be noticed that the functional importance of each MDR family is not correlated with the size of the family. If anything, it might even be the opposite, since the strictest substrate specificity is often associated with housekeeping enzymes of low multiplicity (cf. Table 3, below). Functionally, higher vertebrates have at least 11 separate MDR activity types (Fig. 4, below).

Table 2.

Number of members of the MDR families discussed as detected in the Uniprot sections Swissprot and TrEMBL with the corresponding HMMs at the stringent E-value level of 1e-100 or better.

| Family | Members | Swissprot | TrEMBL |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADH | 931 | 99 | 832 |

| CAD | 520 | 35 | 485 |

| LTD | 427 | 15 | 413 |

| TADH | 330 | 40 | 290 |

| YHDH | 295 | 1 | 294 |

| BPDH | 229 | 3 | 226 |

| PDH | 218 | 18 | 200 |

| TDH | 215 | 49 | 166 |

| BurkDH | 67 | 0 | 67 |

| MCAS | 58 | 1 | 57 |

| MECR | 49 | 13 | 36 |

| VAT1 | 39 | 6 | 33 |

| QOR | 28 | 8 | 20 |

| ACR | 25 | 4 | 21 |

| DOIAD | 16 | 7 | 6 |

| QORL | 14 | 3 | 11 |

| RT4I | 10 | 3 | 7 |

Table 3.

Characteristic differences in properties between ‘constant’ and ‘variable’ oligomeric DHs.

| ADH III | ADH non-III | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary structure | Constant | Variable (∼3–5 × III) |

| Segment variability | Non-functional (at 2 sites) | Functional (at 3 sites) |

| Multiplicity | Often single form(s) | Often multiple forms |

| Main substrate specificity | Strict | Wide |

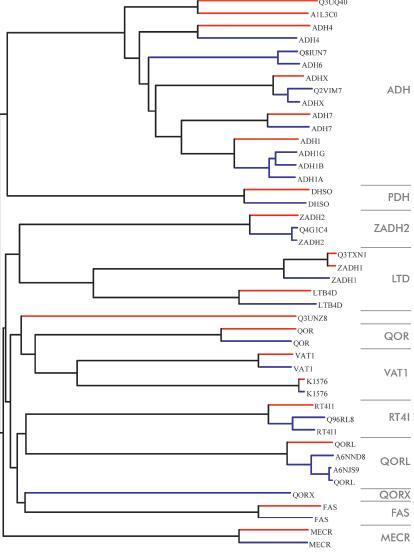

Figure 4.

Dendrogram of human and mouse MDR forms. Blue lines represent human MDRs and red lines mouse MDRs. At the right, MDR families are shown in grey. Labels show the Uniprot name excluding species designation. Tree drawn using the NJPlot program [113]. A complete tree with bootstrap values and full Uniprot identifiers is shown in Supplement Figure 3.

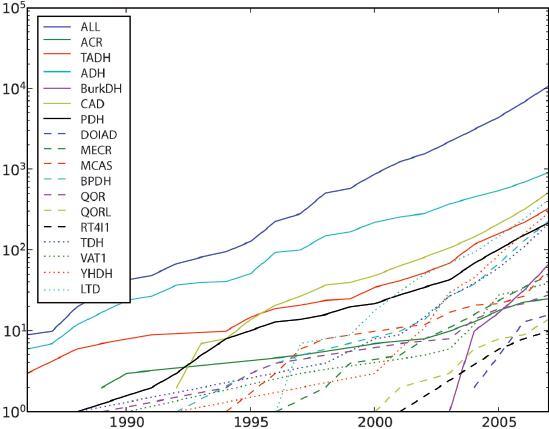

Knowledge of multiplicities within the MDR superfamily is steadily increasing (Fig. 1). In 1983, ADH and YADH (now TADH) were the only MDR families in the databases. In the latter half of the 1980s, the PDH (polyol DH) family became noticeable, followed by the first members of the TDH (threonine DH), QOR (quinone oxidoreductase), VAT (vesicle amine transport), ACR (acyl-CoA reductase) and CAD(cinnamyl ADH) families. In the early 1990s, the first members of the functionally uncharacterised BPDH and YHDH families were ascribed. In the mid-1990s, the first MECR (mitochondrial trans-2-enoyl-CoA-reductase, previously known as ‘protein for mitochondrial respiratory function’) and LTD (leukotriene B4 dehydrogenase) members were characterised, as was the first MCAS (mycocerosic acid synthesis protein) member. Between 2000 and 2004, the MDR superfamily has seen the addition of the four families of QORL (quinone oxidoreductase-like proteins), RT4I1 (Nogo-interacting mitochondrial proteins), BURK (DHs from Burkholderia bacteria) and DOIAD (deoxy-scylloinosamine dehydrogenases). In the following, we present the different MDR families with short descriptions and key references. Some of these MDR families were reviewed earlier [2, 17].

Figure 1.

Diagram showing number of members in MDR families versus the year of sequence appearance in the Uniprot database. The curve ALL shows the total number of MDR members. The years used in the diagram are those corresponding to when the sequence was entered into Uniprot (Swissprot or TrEMBL). There might be a lag period from the time of the original sequence report to the occurrence in the database.

Highly widespread MDR families

At least eight MDR families are large, each with presently more than 200 members, and in total 3165 known proteins, thus corresponding to about one-third of the MDR superfamily members.

1. The ADH family

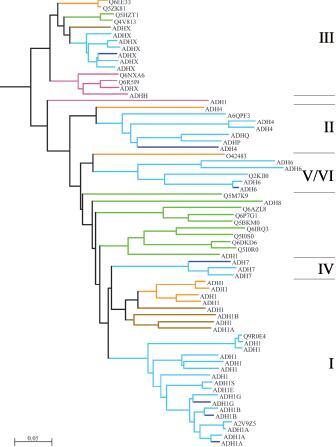

Based upon the present multiple sequence alignment and dendrogram of all MDR forms, ADH constitutes a natural family, encompassing animal ADH, plant ADH and FADH (glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase, also known as class III ADH). The ADH family as an entity is also supported by our HMM analyses. The ancestral form appears to be FADH, which is present in all kingdoms of life, and the sole form present in non-vertebrate animals [18]. The dendrogram in Figure 2 may appear to suggest that classes II and V/VI emerged early, but the data for these classes are few. Disregarding the little known forms, class I ADH from fish branches off first. This duplication was timed to have occurred in early vertebrate evolution by extrapolation from structural divergence already at the stage when an amphibian ADH was characterised [19]. This conclusion was confirmed when the first osseous fish ADH was characterised, showing class-mixed properties [20], even more fine-tuned at ∼500 MYA when early chordate ADHes had been characterised [18], and further established when class I was not found in cartilaginous fish, originating just before the III/I split [21]. The data also show that class III, with its formaldehyde dehydrogenase activity, is the most constant ADH form [22] and that class I, with its typical alcohol DH activity in liver, is the evolving form, illustrating evolution of a new enzyme activity (enzymogenesis) [22]. These two activity types are correlated with specific differences in evolutionary rates at both the entire protein level and the level of functional segments [23].

Figure 2.

Dendrogram of vertebrate ADH forms. Lines are coloured according to vertebrate classes: blue=human, light blue=mammal, orange=bird, green=amphibian, brown=reptile, violet=fish. Labels show the Uniprot name excluding species designation. Roman numbers indicate ADH classes. Tree drawn using the NJPlot program [113]. Some branches are very short with low bootstrap values due to lack of data. The exact branching order might therefore change when more data become available. A complete tree with bootstrap values and full Uniprot identifiers is shown in Supplement Figure 1. Furthermore, Supplement Figure 2 shows a dendrogram, calculated in the same manner, showing all animal ADH forms.

The MDR-ADHs have served as a model system, showing that repeated duplicatory events can be traced, and that mechanistic segments can be discerned and correlated with emergence of functions. The patterns obtained, with evolutionarily ‘constant’ and ‘variable’ classes within the same enzyme family, were further shown to apply also to other multi-form DHs [24], and in fact to many oligomeric enzymes in general. The overall constant enzymes were found to correspond to the ancestral activities, often constituting basic, metabolic housekeeping enzymes, while the variable enzymes corresponded to the evolving forms, exhibiting enzymogenesis [22] (Table 3). The difference in evolutionary speed between constant and variable forms of the same enzyme type was often about threefold (as for class I [variable] and class III [constant] ADH) but can approach fivefold (as for class II [25] versus III ADH). Similarly, the variable segments that do exist in the constant (ancestral) enzymes (class III ADH) are spatially superficial or elsewhere non-functional (‘unimportant’ segments), as for proteins in general. In contrast, the variable segments in the overall variable enzymes are functional, illustrating the evolution of new activities, as shown by ADH class I, where the variable segments constitute parts of the active site, the subunit interaction area and zinc binding regions. This is summarised in Table 3, which shows that functional properties of enzymes can be readily deduced from internal patterns of evolutionary changes in oligomeric enzymes [23, 26].

The distinction of the early gene duplication at ∼500 MYA in the MDR-ADH system established many rules applicable to the evolution of oligomeric enzymes in general. It also showed the presence of repeated recent duplications giving rise to isozymes. In Baltic cod (Cadus callarias) and Japanese rice fish (Oryzias latipes) only one form is seen, while in zebrafish (Danio rerio) there exist three forms with less than 90% pairwise identity. This type of duplicatory pattern is again typical of the class I enzymes, and is also seen in the mammalian ADH class I forms, where the human isozymes have three types of chain (and corresponding genes), horse two and rat one. Thus, this whole group of oligomeric enzymes appears to exhibit a correlation between the accumulation of point mutations and those of gene duplications, giving a pattern in which the constant, basic enzyme forms appear to be less multiple, and the evolving, variable isoforms more multiple (Table 3).

The next radiation in the MDR-ADH line apparently forms the foundation for the branching of the class II ADH line, with members from both birds and mammals, including humans (Fig. 2). Class IV deviates from class I at a later stage, presently estimated to a time between amphibians and birds [27]. Class IV has hitherto only been reported from mouse, rat and humans.

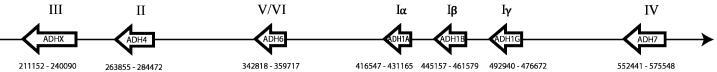

The duplications mentioned above explain the pattern of human ADHs (Fig. 3), with seven ADH forms: class I (with three isoforms ADH1A, ADH1B and ADH1G), class II, class III, class IV and class V. Class I is the typical liver enzyme (1A also of foetal expression) with activity towards many alcohols, including ethanol. Class II is predominantly also expressed in liver but less abundant and not much studied. Class III is the ubiquitous GSH-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase. Class IV is an ADH of stomach and other organs, and class Vis expressed in human foetal liver [23, 27, 28]. Further duplications have occurred in other animal lines. For example, birds have an additional liver ADH form, first detected in chicken [29], but isolated from feral pigeon [21] and shown to be functionally much like class I [21, 29], although not much further studied. The dendrogram (Fig. 2) reveals other additional, ‘outliers’, e.g. the NADP-dependent ADH8 from claw frog (Rana perezii) [30].

Figure 3.

Human ADH gene arrangement on chromosome 4. The arrows schematically indicate the chromosomal location of human ADH genes. The Swissprot ID (excluding ‘_HUMAN’) is given within the arrow, while class designations are given above the arrows. Chromosomal coordinates [103 for each gene are given below the arrows.

2. The TADH family — tetrameric ADHs

The yeast versus liver ADH relationships are historically interesting to follow. Early on, these two enzymes were considered quite separate in the ‘bible’ of that time (‘The Enzymes’, 2nd edition, [31]) and had different cysteine residues reactive towards labelling reagents [32, 33], but were given the same Enzyme Commission number (EC 1.1.1.1) when that system was introduced. Later on, a clear relationship between liver and yeast ADHs was established [34], the common yeast ADH characterised [35] and subsequently many additional forms. Overall, most of the yeast ADHs, versus the liver enzymes, lack an internal segment, affecting subunit interactions [36] and hence the quaternary structure. They are therefore often tetrameric, versus the dimeric nature of the liver ADHs, and are now again naturally distinguished (as here) as a separate subfamily, TADH. This family consists of yeast ADH and closely related bacterial ADHs. The crystallographic structure of classical yeast ADH was determined fairly late [37], but now several TADHs have been determined in 3D structure.

In yeast, three ADHs have long been known — two closely related cytosolic (YADH1 and YADH2) and one mitochondrial (YADH3) (cf. [38–40]). These YADHs are tetrameric. YADH1 is the constitutive enzyme which is expressed during fermentation [41] and upregulated by glucose, while YADH2 is the oxidative enzyme, the expression of which is repressed by glucose [38]. YADH1 is the major alcohol dehydrogenase in growing baker’s yeast [40]. Mitochondrial YADH3 is expressed at very low levels compared to YADH1 and YADH2 [42]. The YADH5 form was characterised from the yeast genome project and found to be distantly related to YADH1—3. Furthermore, yeast has YADH4, which is an iron-dependent enzyme and does not belong to the MDR family [43]. Similarly, in the fungus Emericella nidulans (Aspergillus nidulans), there are also multiple ADH forms [44]. ADH1 is active in ethanol utilisation and is induced by ethanol, while ADH2 has unknown function and is repressed by ethanol. The ADH3 form is induced by anaerobiosis and has been suggested to be of importance for survival at peroids of water logging [45].

The YADH enzymes are active with primary, unbranched, aliphatic alcohols, with ethanol as the best substrate [40]. Furthermore, allyl alcohol and cinnamyl alcohol are good substrates [46]. YADH also has weak aldehyde dehydrogenase activity, which probably has gem-diol as its natural substrate [40].

The bacterial ADHs of the TADH family stem from a number of species, representing both Gram-negative and Gram-positive forms. However, apart from the bacterial and yeast forms, the TADH family also has two members from the worm Caenorhabditis elegans.

3. The PDH family — polyol DHs

PDHs also have an early history in our tracing of the MDR family relationships. Thus, the sorbitol DH versus ADH relationships constituted a considerable extension of the MDR family and were the base for distinguishing MDR as a superfamily containing several enzyme forms [7]. Similarly, another PDH, the prokaryotic ribitol DH [47] and its relationships with Drosophila ADH [48], helped to define the other superfamily [7], SDR, in the MDR/SDR pair of superfamilies [49]. These two protein types established early that parallel evolution of similar enzyme activities was a characteristic of many DHs. SDR and MDR are now known to complement each other and to contribute an extensive redundancy of DHs in metabolic pathways.

The PDH family contains sorbitol DH (SDH) and xylitol DH(XDH). SDH (EC 1.1.1.14), also known as glucitol DH, polyol DH or L-iditol DH, catalyses the interconversion of L-iditol and L-sorbose and that of D-glucitol and D-fructose. The enzyme also acts on related sugar alcohol substrates. XDH (EC 1.1.1.9) catalyses the interconversion of xylitol and D-xylulose. The three-dimensional structure of an SDH is available [50], confirming SDH to be a tetramer binding only one zinc ion per subunit, since it does not possess the structural zinc binding loop of the ADH family, which was already defined from the chemical analyses [5, 51]. SDHs are present in bacteria, yeast and animals, suggesting an important function in a wide range of life forms. In the fungus Apergillus, multiple forms of PDH exist. In insects, we also see multiple PDH forms. In mammals, SDH is expressed in many internal tissues, including the prostate, thyroid, liver, pancreas, kidney and testis [28, 52].

4. The CAD family — cinnamyl ADHs

The CAD family encompasses cinnamyl ADHs (EC 1.1.1.195) and mannitol dehydrogenases (MTDs). The CADs are important in lignin biosynthesis in plant cell walls, where they reduce cinnamaldehydes into cinnamyl alcohols in the last step of the monolignol pathway [53]. Each CAD monomer binds two zinc ions and uses NADPH as cofactor. A three-dimensional structure for a CAD representative is available [54]. CAD is active with several p-hydroxycinnamyl aldehydes to produce p-coumaryl, coniferyl and sinapyl alcohols.

The CAD and MTD forms divide before the speciation of different plants, and several plants have both enzyme types. Furthermore, many CADs show species-specific multiplicity, analogous to ADHs in mammals.

CAD genes have been observed to be duplicated in some angiosperms [55, 56]. In Arabidopsis 9 CAD genes have been identified [57], and in rice 12 CAD genes are present [58]. The individual roles of these multiple enzymes are still not clarified, but recent studies have added important information [59], showing that CAD genes are not expressed only in lignifying tissues but also in various non-lignifying zones, which might indicate a role in plant defence. Furthermore, some CAD members show no CAD catalytic activity in vitro but are expressed in lignin-forming tissues, possibly indicating different biochemical roles [59].

Mannitol dehydrogenase (MTD) oxidises mannitol to mannose [60]. These enzymes from Arabidopsis and parsley were initially described as ELI3 pathogen-related proteins [61]. The MTDs might provide an additional source of carbon and energy for response to pathogen attacks, thus forming an adaptation to environmental stress [60]. The MTD enzyme exists as a monomer [62, 63]. This is different from other MDR members, which are dimers or tetramers.

Interestingly, the CAD family is not limited to plants. Single distantly related members also exist in other species. There are two such enzymes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ADH6 and ADH7), described to have aldehyde reductase activity [64, 65]. These enzymes have high activity with cinnamaldehyde, but since yeast does not synthesise lignin, it seems likely that the physiological function is different. One function might be to maintain the NADP+/NADPH balance or to participate in the formation of fusel alcohols [65].

A CAD member is also known from slime mold. Furthermore, some prokaryotic enzymes have been found to be distantly related to the CAD family. Examples include proteins from Escherichia coli (YJGB_ECOLI and YAHK_ECOLI) and Mycobacteriae (ADHC_MYCTU and ADHC_MYCBO). The function of these is still unclear. One distantly related member (YL498_MIMIV) originates from Mimivirus [66], which is a very large virus, and has a particle size comparable to that of Mycoplasma, is a double-stranded DNA virus and grows in amoebae.

5. The LTD family — leukotriene DHs

This is an MDR family of great interest in human eicosanoid physiology. The LTD family has two mammalian enzyme groups, one with leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase (LTB4D) activity, and the other, denoted ZADH1, with hitherto unknown function.

The LTB4D enzymes have LTB4D and 15-ketoprostaglandin 13-reductase (PGR) activity. These enzymes act specifically on the 12(R)-hydroxy group of leukotriene B4 [67]. The LTB4D/PGR enzymes are reported to predominantly have PGR activity [68]. The enzyme is widely expressed in liver, kidney, intestine, spleen and stomach [68]. In another tissue expression study, human LTB4D was mainly found in bronchial epithelial cells [28]. PGR is a critical enzyme that irreversibly inactivates all types of prostaglandins. The substrate specificity includes prostaglandins E1, E2 and F2α. The preceding step of prostaglandin inactivation is dependent on 15-hydroxyprostaglandin DH, which is a member of the SDR superfamily.

There are LTB4D forms down to the fish line, compatible with the presence of eicosanoids in fish [69]. Analogously, the MAPEG (membrane-associated proteins in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism) superfamily has many family members down to the fish line [70]. LTB4D homologues are also found in insects.

Furthermore, the LTD family has members from yeasts, plants and bacteria. The Arabidopsis thaliana members P1_ARATH and P2_ARATH have been ascribed a role in defence against oxidative stress [71]. The bacterial YNCB from E. coli is an NADP+-dependent dehydrogenase.

The three-dimensional structure of LTB4D/PGR is known [72]. This MDR member binds no zinc, causing the substrate and coenzyme binding to be different from those of most other MDR members. Instead, the enzyme bears some similarities with the QOR structures.

The not yet functionally characterised ZADH1 forms are found down to fish and worm. Tissue distribution shows that this type of protein is expressed in many tissues, e.g. kidney, liver, pancreas, prostate and heart [73].

6. The TDH family — threonine DHs

TDH (EC 1.1.1.103) oxidises threonine to l-2-amino-3-oxobutanoate in the presence of NAD+. The MDR type TDH family has only bacterial members. Mammalian TDHs are of a different kind, belonging to the SDR superfamily [74]. This multiple enzymogenesis of the same activity from different superfamilies is again analogous to the situation for ADHs and PDHs, where different forms belong to either of these two superfamilies.

7. The BPDH family

The tentatively named BPDH family (bacterial and plant DHs) has 229 members from bacteria and plants. However, in spite of the large number of members, the function of these proteins is still unknown. The BPDH members are found in over 150 species, of which some 30-odd species have multiple forms of these MDR enzymes.

8. The YHDH family

This family is provisionally named after its E. coli member yhdH. All hitherto known 295 members of this family are bacterial, thus far found in close to 200 species. Nearly 20 species have multiple YHDH enzymes. Also for this large family, the function is still unknown. The E. coli sequence was reported to be adjacent to the gene encoding biotin carboxylase and might be co-regulated with that gene [75].

Additional MDR families of special interest

As mentioned above, the MDR superfamily consists of close to 500 families, of which all but the 8 most widespread currently have fewer than 200 members and the majority fewer than 10 members. The latter are thus of restricted occurrence, reported from particular life forms, and presently attract limited general interest. All cannot be presented here, but some, including most of those having members from the human species, are outlined below. Several of these families are likely to be of great importance in humans and in mammals, regulating neural functions (Nogo-interacting proteins, family 16, below), nuclear receptor functions (MECR proteins, family 12), fatty acid synthesis (ACR, family 13) and other metabolic steps.

9. VAT1 — vesicle amine transport protein 1

The first described member of the family of VAT1 was from the electric ray Torpedo californica. It has been reported to have ATPase activity and to bind ATP and calcium [76, 77]. The VAT1 family has members in animals from fish, amphibians and mammals. A human VAT1 homologue has also been reported to display ATPase activity [78]. VAT1 is found in mouse epidermis and in rat pituitary sprague [28]. In zebra-fish, a VAT1 homologue has been cloned and its expression pattern has been investigated [79]. It shows expression associated with neuronal and brain development — early expression in the trigeminal nuclei and later in neuron clusters, epiphysis and hindbrain. In addition, VAT1 homologue expression appears in the maturing retina and pharyngeal cavity.

Also belonging to the VAT1 family, but at a separate evolutionary branch, we find in human and mouse a protein named K1576, which is mainly expressed in the hypothalamus but also in the cerebellum and caudate nucleus [28]. Corresponding proteins are present in amphibians, fish and insects. The bifurcation between the VAT1 branch and the K1576 branch is before the fish line, indicating separate functions for these two proteins already about 500 million years ago, as in the case of the ADH class I/III split in animals.

10. QOR — quinone oxidoreductase

QOR has enzymatic activity with quinones [80]. The QOR family has members from mammals [81], birds, amphibians, fish and worms. Some bacterial forms are also included in the QOR family. In humans, QOR is expressed in lymphoblasts and in foetal liver [28].

There are distantly related QOR homologues in plants, but present sequence comparisons do not group these together with the QOR family. The function of these might be protection against diamide compounds [cf. 82].

The three-dimensional structure of E. coli QOR [83] shows the typical MDR fold but without the structural zinc binding loop, compatible with a tetrameric structure, similar to SDHs and yeast ADHs. The structure shows that the strictly conserved Tyr46 (E. coli numbering) is coenzyme binding, while the strictly conserved Tyr52 is likely to be substrate binding.

11. QORL — quinone oxidoreductase like protein

As a separate family, there are QOR-like proteins. One human member is named zeta-crystallin-like 1 (CRYZL1, QORL). The function is not yet revealed, but the protein is expressed in several tissues, such as heart, brain, skeletal muscle, kidney, pancreas, liver and lung [84]. QORL proteins are found in species from fish and upwards along the evolutionary tree. There are a few MDR members annotated as QOR like proteins mainly dependent upon sequence similarity to ZCR/QOR but without any described function. When now many more MDR forms are known, some of the early annotated QOR-like members show closer relationships with other MDR members and future reannotation seems probable.

12. MECR — mitochondrial trans-2-enoyl-CoA-reductase

The MECR family contains mitochondrial trans-2-enoyl-CoA-reductases. These were previously known as MRF1, mitochondrial respiratory function 1 proteins [85]. MECR is also known as nuclear receptor binding factor-1 (NRBF-1). Its function has been suggested to be a transcription factor regulating the expression of genes for mitochondrial respiratory proteins [86].NRBF-1 has been shown to interact with several nuclear receptors — TRβ, RARα, RXRα, PPARα and HNF-4 — binding to the activated forms of these receptors.

In yeast, MRF1 activity was later shown to be a trans-2-enoyl thioester reductase (ETR) in the fatty acid synthesis of the mitochondrion [87]. The enzyme reduces trans-2-enoyl-CoA to acyl-CoA with substrate specificity of C6–C16, using NADPH as coenzyme. MECR members are present in plants, insects, worms, fish and mammals. The human enzyme in mainly expressed in skeletal and heart muscle [87]. In C. elegans, there are two different MECR forms, showing 39% pairwise identity.

13. ACR — acyl-CoA reductase

The ACR part of the multi-domain fatty acid synthase (FAS) is an MDR enzyme. ACR members are found in mammals, birds, fish, worms and insects. In Drosophila, there are two forms of fatty acid synthases, differing by 60–62%. In mouse, FAS is expressed in brown fat, adipose tissue, mammary gland, ovary and adrenal gland [28]. Notably, one of the FAS domains is β-ketoacyl reductase, which belongs to the SDR superfamily, again demonstrating that these two superfamilies are functionally often combined.

14. MCAS — mycocerosic acid synthesis protein

Distantly related to the ACR family, there is an MDR protein which is part of the multifunctional protein for mycocerosic acid synthesis (MCAS) [88]. This synthesis involves elongation of acyl-CoA with methylmalonyl-CoA, thus bearing functional similarities with the fatty acid synthesis in mammals. The family mainly consists of Mycobacterium members.

15. DOIAD — 2-deoxy-scyllo-inosamine DH

The DOIAD family members have 2-deoxy-scylloinosamine DH activity, of importance for synthesis of neomycin B, butirosin B, gentamycin, tobramycin and kanamycin [89,90]. The DOIAD members are parts of multigene clusters in Streptomyces and Bacillus species. Members are also found in Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium, Micromonospora, Arthrobacter and Pelobacter.

16. RT4I1 — Nogo-interacting mitochondrial protein

RT4I1 is a Nogo-interacting mitochondrial protein (NIMP) [91]. Nogo is a potent inhibitor of regeneration following spinal cord injury. NIMP is found in neurons and astrocytes [91]. Comparing the NIMP sequences between human, mouse and bovine, we see that the catalytic domain is much more conserved than the coenzyme binding domain [91], which indicates a critical function of this domain in NIMP. RT4I1 is present in species from fish and upwards through evolution. In humans, we find two closely related forms.

17. BurkDH — DHs from Burkholderia and other bacteria

The tentatively named BurkDH family is formed by 50-odd proteins from Burkholderia, Yersinia, Clostridium, Mycobacterium, Pseudomonas and other bacteria. Most sequences hitherto are from Burkholderia. All sequences of the BurkDH family have been identified from genome projects, and the functions of these proteins have not yet been investigated.

Small groups of MDR members

In addition to the 17 MDR families outlined above, there are a number of MDR forms with just a few known homologues. Some of these appear to have special properties of particular interest as mentioned below.

ADH_THEBR is found in a small group of NADP dependent bacterial ADHs (including ADH_CLOBE and ADH_MYCPN) and NADP-dependent ADH from the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica (ADH1_ENTHI, [92]). The ADH from Clostridium beijerinckii is an NADP-dependent ADH with a preference for secondary alcohols [93].

A small family is formed by GSH-independent formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FADH) with bacterial members having FADH activity that, in contrast to the common FADH described under ADH above, is not glutathione-dependent. This enzyme has been characterised in Pseudomonas putida (FADH_PSEPU) [94]. Its three-dimensional structure shows a typical MDR fold but with a long insertion in the C-terminal domain shielding the NAD molecule, thus contributing to tight cofactor binding, which apparently makes it possible to oxidise and reduce aldehydes without releasing the cofactor [95].

There is also an NAD(P)-dependent FADH from the marine methanotroph Methylobacter marinus (FADH_METMR) [96]. It does not belong to the FADH family but shows closer relationship to the GSH-independent FADHs.

ZADH2 has presently been found only in humans and mouse and not yet characterised in detail. TP53I3 is expressed in smooth muscle and BM-CD33 myeloid [28]. BDH1_YEAST is an NAD-dependent (2R,3R)-2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase (BDH) [97]. Its closest relative is YAG1_YEAST.

IDND_ECOLI is involved in the pathway for catabolism of l-idonic acid, where the MDR member is responsible for the reversible oxidation of l-idonate to 5-ketogluconate [98]. FDEH_PSEPU is a plasmidencoded 5-exo-hydroxycamphor DH in Pseudomonas putida [99], catalysing the formation of 2,5-diketocamphane. Benzyl ADH from Pseudomonas putida (XYLB_PSEPU) [100] also forms a separate group. ADH_RALEU is a fermentative, multifunctional ADH from Alcaligenes eutrophus [101].

MDRs in complete genomes

During the last decade, many genome projects worldwide have contributed to a vast knowledge of protein sequences. This makes it possible to perform largescale investigations of sequence patterns (cf. [102]) and provides increased information about protein family members and their evolution. Early in 2007, close to 400 complete genomes were available in the databases [103–105]. We have used this information to investigate the number of MDR forms in the various genomes. The general impression is that on the average 0.2% of all protein-coding genes in an organism are MDR enzymes. However, there is a large span, ranging from nearly 0 to 0.85%. The species with the highest proportion of MDR enzymes are different Mycobacterium species, Rhodococcus and Rubrobacter. Among those with no or only few MDRs, we find genomes with low numbers of open reading frames, e.g. Mycoplasma and Clamydia, and several of these do not have complete metabolism but act as parasites. In the human genome, there are 0.78% MDR forms.

The genomes with the largest number of MDR forms (Table 4) originate from plants. One reason is the tetraploidicity of these genomes, which contributes to several closely related forms. When correcting for such redundancy by elimination of identical, or closely related, sequences, the number of different forms drops considerably, as can be seen in the different columns in Table 4. For instance, the plant numbers are down to 1/4 after redundancy reduction to the 40% level.

Table 4.

The 10 species with the largest number of MDR forms in Uniprot.

| Redundancy level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Code | Total | 99% | 90% | 60% | 40% | 25% |

| Aspergillus niger | ASPNG | 120 | 120 | 120 | 109 | 76 | 32 |

| Vitis vinifera | VITVI | 119 | 107 | 95 | 49 | 29 | 20 |

| Aspergillus oryzae | ASPOR | 110 | 110 | 110 | 99 | 72 | 34 |

| Oryza sativa Japonica Group | ORYSJ | 101 | 96 | 83 | 47 | 24 | 14 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | PSEAE | 90 | 44 | 29 | 28 | 23 | 11 |

| Aspergillus terreus NIH2624 | ASPTN | 89 | 89 | 89 | 84 | 70 | 33 |

| Burkholderia mallei | BURMA | 82 | 30 | 24 | 21 | 16 | 7 |

| Phaeosphaeria nodorum | PHANO | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 68 | 34 |

| Emericella nidulans | EMENI | 80 | 80 | 80 | 77 | 65 | 31 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | LISMO | 78 | 15 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 5 |

The total number and the number at different levels of redundancy reduction are shown. Clearly, there is a drop in number for several organisms already at the 99 and 90% levels, indicating small variations leading to an increase in the number of MDR forms. At the 25% level, indicative of different MDR families, most organisms have around 20 different forms.

We have also analysed the occurrence of the different MDR families in the complete genomes (Table 5). We find that in archaeal organisms, there are only a few MDR representatives. In bacteria, the most frequent MDR form is ADH, but still only 36% of the genomes have such a representative. The second most frequent family is YHDH, present in 31% of the genomes. About 25% of the bacterial genomes show CAD, TADH, LTD, TDH and BPDH members. In eukaryotes, most of the MDR families are frequently represented. We find ADH at the top, present in 79% of the eukaryotic genomes, followed by PDH (68%), MECR (66%) and LTD (54%). Although high numbers, these values, especially the ADH value, are lower than perhaps expected, since in direct analyses, ADH family members are highly widespread. Notably, eukaryotes missing ADH in the genome databases are some invertebrates, single-cell plants, parasites living in higher cells, or little-studied forms. The rule of widespread ADH members is therefore still applicable, but may perhaps not apply to all lower eukaryotes, or MDR-ADH may be replaced with SDR-ADH, compatible with the mixed presence of these two families in metabolic pathways as noticed above.

Table 5.

Occurrence of MDR families in completed genomes.

| Subfamily | Total | Bacteria | Archaea | Eukaryota |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACR | 18 (0.035) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 (0.32) |

| ADH | 199 (0.38) | 155 (0.36) | 0 (0) | 44 (0.79) |

| BPDH | 100 (0.19) | 97 (0.22) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.054) |

| BurkDH | 24 (0.046) | 24 (0.055) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| TADH | 130 (0.25) | 114 (0.26) | 0 (0) | 16 (0.29) |

| CAD | 139 (0.27) | 123 (0.28) | 2 (0.071) | 14 (0.25) |

| DOIAD | 2 (0.0039) | 2 (0.0046) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| LTD | 142 (0.27) | 110 (0.25) | 2 (0.071) | 30 (0.54) |

| MCAS | 12 (0.023) | 12 (0.028) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| MECR | 37 (0.071) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 37 (0.66) |

| PDH | 68 (0.13) | 29 (0.067) | 1 (0.036) | 38 (0.68) |

| QOR | 20 (0.039) | 2 (0.0046) | 0 (0) | 18 (0.32) |

| QORL | 15 (0.029) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15 (0.27) |

| RT4I | 17 (0.033) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 17 (0.30) |

| TDH | 107 (0.21) | 103 (0.24) | 4 (0.14) | 0 (0) |

| VAT1 | 20 (0.039) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20 (0.36) |

| YHDH | 134 (0.26) | 133 (0.31) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.018) |

| Total number of genomes | 519 | 435 | 28 | 56 |

The numbers report genomes with at least one representative of the family. Boldface indicates that 25% or more of the genomes have family members.

Human MDRs

There were 40 human MDR members in the Uniprot database as of November 2007. Removing proteins with more than 98% identity reduces this number to 25 forms. Looking at the dendrogram of human and mouse MDR forms (Fig. 4) we find 11 groups of equidistantly related MDR families. The largest of these is the ADH family with 9 members (one each of human class Iα, Iβ, Iγ, II, IV, and two each of class III and V/VI). However, these annotations still correspond to only 7 genes. The next largest group is the QORL family with three functionally not characterised quinone reductase-like forms. Furthermore, we find the VAT1 family with two forms, the human VAT1 homologue and the K1576 protein. The LTD family has LTB4D and the ZADH1 as members. Also, the RT4I1 family has two human members.

As a single species-specific MDR enzyme in humans, we find QORX_HUMAN, which seems to be human-specific, lacking any close homologue in mouse, chicken and zebrafish (Fig. 4). Analogously, there is one MDR form that seems to be specific for mouse, Q3UNZ8, not present in humans.

Looking at the chromosomal localisation of human ADHs (Table 6), we find that only the ADHs are clustered. All other MDR forms in humans are located on different chromosomes or separated by several tens of million base pairs. The gene arrangement of ADHs has recently been reviewed [106].

Table 6.

Chromosome localisation of human MDRs.

| Uniprot ID | Chromosome localisation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | Begin (bp) | End (bp) | |

| MECR_HUMAN | 1 | 29391972 | 29430041 |

| QOR_HUMAN | 1 | 74943758 | 74971347 |

| QORX_HUMAN | 2 | 24153809 | 24161426 |

| ADHX_HUMAN | 4 | 100211152 | 100240090 |

| ADH4_HUMAN | 4 | 100263855 | 100284472 |

| ADH6_HUMAN | 4 | 100342818 | 100359717 |

| ADH1A_HUMAN | 4 | 100416547 | 100431165 |

| ADH1B_HUMAN | 4 | 100445157 | 100461579 |

| ADH1G_HUMAN | 4 | 100476672 | 10049294 |

| ADH7_HUMAN | 4 | 100552441 | 100575548 |

| RT4I1_HUMAN | 6 | 107125596 | 107184066 |

| LTB4D_HUMAN | 9 | 113365074 | 113401917 |

| ZADH1_HUMAN | 14 | 73388424 | 73421915 |

| DHSO_HUMAN | 15 | 43102644 | 43154330 |

| K1576_HUMAN | 16 | 76379984 | 76571504 |

| VAT1_HUMAN | 17 | 38420148 | 38427985 |

| FAS_HUMAN | 17 | 77629504 | 77649395 |

| ZADH2_HUMAN | 18 | 71039477 | 71050105 |

| QORL_HUMAN | 21 | 33883520 | 33936094 |

MDRs in thermophiles

Several MDR forms have been found in thermophilic organisms. These thermostable variants are found at several places in the MDR evolutionary tree, indicating that this environmental adaptation has appeared multiple times through evolution. Some thermostable ADHs are found in the TADH family (ADH_SULSO, ADH1_BACST), while others are found together with another group of bacterial ADHs (ADH_THEBR).

The three-dimensional structure of ADH from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus is available, revealing interesting structural properties [107].The orientation of the domains is different than that common in other MDRs, thus providing a larger interdomain cleft [107]. The enzyme is reported as a tetramer in the crystallographic studies, but a dimer in the initial protein characterisation [108]. Characterisation of wild-type Sulfolobus ADH has shown the presence of both dimeric and tetrameric forms [109].The existence of a tetrameric state at the same time as this ADH has both the catalytic and the structural zinc ions deviates from the general pattern seen among other members of the MDR superfamily. One of the structural zinc ligands is glutamic acid instead of cysteine. A similar residue exchange is found in archaeal glucose dehydrogenase from Thermoplasma acidophilum [110] where an aspartic acid residue replaces a cysteine residue. Removal of the structural zinc in Sulfolobus ADH reduces the structural stability [108,109] similarly to the case for yeast ADHs [111]. In human class III ADH, replacement of one of the structural cysteine residues by glutamic acid has also been shown to decrease the stability of the protein [112]. Thus, the structural zinc might be important in the folding or the folding process [107].

General conclusions

The MDR superfamily shows a considerable multiplicity with several families demonstrating gene duplications at multiple levels during evolution. Both MDR and SDR have versatile properties, are composed of building blocks and constitute metabolically important enzymes, as well as regulatory proteins in several systems. Parallel enzymogenetic events have formed the same enzyme activity in different manners, such that an activity can be contributed by MDR enzymes in some species and by SDR enzymes in others. Similarly, some multi-enzyme complexes have components of both MDR and SDR members. For several MDR members, the functions are still unknown. This also applies to a few of the large families, providing possibilities for future discoveries of interesting results. Several MDR members, including ADH, appear to be important in protection against toxic compounds and other forms of environmental stress.

Structurally, the MDR superfamily shows a variety of quaternary structures, ranging from monomers (MTD), via dimers and trimers, to tetramers. Furthermore, the zinc dependence is also variable, between 0, 1 and 2 ions per subunit in different families.

The coenzyme-binding domain is of the abundantly occurring Rossmann fold-type and the catalytic domain is distantly homologous to GroES [13]. Thus, the modular architecture and the mosaic composition of proteins in general are clearly illustrated also in the MDR superfamily.

Finally, the multiplicity, redundancy, and functional inter-relationships of several MDR, SDR and other DH families are impressive. For a metabolically functional pair, like alcohol DH and aldehyde DH jointly forming the acid from an alcohol, there are many functional combinations. In part, this explains interpretational difficulties in functional assignments of several activities. However, it also appears to be the structural basis allowing these DH pairs more or less in parallel to participate in both regulatory fine-tuning of important steps, like formation of differentiating retinoic acid in key developmental functions, and mass conversions of external and environmentally abundant substrates like ethanol and toxic components.

Electronic supplementary material. Supplementary material is available in the online version of this article at springerlink.com (DOI 10.1007/s00018-008-8587-z) and is accessible for authorized users.

Electronic supplementary material

Below are the electronic supplementary materials.

Acknowledgement

Much of the support for the work from the laboratories of the authors regarding MDR and SDR structures, functions and relationships has been gratefully obtained from the Swedish Research Council and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

References

- 1.Bairoch A., Apweiler R., Wu C. H., Barker W. C., Boeckmann B., Ferro S., Gasteiger E., Huang H., Lopez R., Magrane M., et al. TheUniversal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D154–159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordling E., Jörnvall H., Persson B. Mediumchain dehydrogenases/reductases (MDR): family characterizations including genome comparisons and active site modelling. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:4267–4276. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavanagh, K. L., Jörnvall, H., Persson, B. and Oppermann, U. (2008) The SDR superfamily: functional and structural diversity within a family of metabolic and regulatory enzymes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci., DOI 10.1007/s00018-008-8588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Jörnvall H. Horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase: the primary structure of the protein chain of the ethanol-active isoenzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 1970;16:25–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeffery J., Cederlund E., Jörnvall H. Sorbitol dehydrogenase: the primary structure of the sheep-liver enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984;140:7–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persson B., Zigler J. S., Jr., Jörnvall H. A superfamily of medium-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (MDR): sub-lines including zeta-crystallin, alcohol and polyol dehydrogenases, quinone oxidoreductase enoyl reductases, VAT-1 and other proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;226:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jörnvall H., Persson M., Jeffery J. Alcohol and polyol dehydrogenases are both divided into two protein types, and structural properties cross-relate the different enzyme activities within each type. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:4226–4230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz M. F., Jörnvall H. Structural analyses of mutant and wild-type alcohol dehydrogenases from Drosophila melanogaster. Eur. J. Biochem. 1976;68:159–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossmann M. G., Liljas A., Brändén C.-I., Banaszak L. J. Evolutionary and structural relationships among dehydrogenases. In: Boyer P. D., editor. The Enzymes, vol. 11. 3rd ed. New York: Academic Press; 1975. pp. 61–102. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao S. T., Rossmann M. G. Comparison of super-secondary structures in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;76:241–256. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohlsson I., Nordstrom B., Brändén C.-I. Structural and functional similarities within the coenzyme binding domains of dehydrogenases. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;89:339–354. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jörnvall H. Differences between alcohol dehydrogenases. Structural properties and evolutionary aspects. Eur. J. Biochem. 1977;72:443–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taneja B., Mande S. C. Conserved structural features and sequence patterns in the GroES fold family. Protein Eng. 1999;12:815–818. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.10.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bateman A., Coin L., Durbin R., Finn R. D., Hollich V., Griffiths-Jones S., Khanna A., Marshall M., Moxon S., Sonnhammer E. L., et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32Databaseissue:D138–141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eddy S. HMMER: profile HMMs for protein sequence analysis. St. Louis: Univ. Washington; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venter J. C., Remington K., Heidelberg J. F., Halpern A. L., Rusch D., Eisen J. A., Wu D., Paulsen I., Nelson K. E., Nelson W., et al. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science. 2004;304:66–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1093857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riveros-Rosas H., Julian-Sanchez A., Villalobos-Molina R., Pardo J. P., Pina E. Diversity, taxonomy and evolution of medium-chain dehydrogenase/reductase superfamily. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:3309–3334. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canestro C., Albalat R., Hjelmqvist L., Godoy L., Jörnvall H., Gonzalez-Duarte R. Ascidian and amphioxus Adh genes correlate functional and molecular features of the ADH family expansion during vertebrate evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 2002;54:81–89. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cederlund E., Peralba J. M., Pares X., Jörnvall H. Amphibian alcohol dehydrogenase, the major frog liver enzyme: relationships to other forms and assessment of an early gene duplication separating vertebrate class I and class III alcohol dehydrogenases. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2811–2816. doi: 10.1021/bi00225a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danielsson O., Eklund H., Jörnvall H. Themajor piscine liver alcohol dehydrogenase has class-mixed properties in relation to mammalian alcohol dehydrogenases of classes I and III. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3751–3759. doi: 10.1021/bi00130a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jörnvall H., Shafqat J., Astorga-Wells J., Jonsson A., Norin A., Bergman T., Hirschberg D., Hjelmqvist L., Keung W.-M. MDR alcohol dehydrogenases: novel forms and possibilities. In: Weiner H., Plapp B., Lindahl R., Maser E., editors. Enzymology and Molecular Biology of Carbonyl Metabolism. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press; 2006. pp. 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danielsson O., Jörnvall H. 'Enzymogenesis': classical liver alcohol dehydrogenase origin from the glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:9247–9251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danielsson O., Atrian S., Luque T., Hjelmqvist L., Gonzalez-Duarte R., Jörnvall H. Fundamental molecular differences between alcohol dehydrogenase classes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4980–4984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin S. J., Vagelopoulos N., Wang S. L., Jörnvall H. Structural features of stomach aldehyde dehydrogenase distinguish dimeric aldehyde dehydrogenase as a ‘variable’ enzyme. ‘Variable’ and ‘constant’ enzymes within the alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase families. FEBS Lett. 1991;283:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80559-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hjelmqvist L., Estonius M., Jörnvall H. The vertebrate alcohol dehydrogenase system: variable class II type form elucidates separate stages of enzymogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:10904–10908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Persson B., Bergman T., Keung W. M., Waldenstrom U., Holmquist B., Vallee B. L., Jörnvall H. Basic features of class-I alcohol dehydrogenase: variable and constant segments coordinated by inter-class and intra-class variability: conclusions from characterization of the alligator enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;216:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parś X., Cederlund E., Moreno A., Hjelmqvist L., Farres J., Jörnvall H. Mammalian class IV alcohol dehydrogenase (stomach alcohol dehydrogenase): structure, origin, and correlation with enzymology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:1893–1897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation, GNF SymAtlas v1.2.4.

- 29.Kedishvili N. Y., Gough W. H., Chernoff E. A., Hurley T. D., Stone C. L., Bowman K. D., Popov K.M., Bosron W. F., Li T. K. cDNA sequence and catalytic properties of a chick embryo alcohol dehydrogenase that oxidizes retinol and 3beta,5alpha-hydroxysteroids. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:7494–7500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peralba J. M., Cederlund E., Crosas B., Moreno A., Julia P., Martinez S. E., Persson B., Farrés J., Parés X., Jörnvall H. Structural and enzymatic properties of a gastric NADP(H)-dependent and retinal-active alcohol dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26021–26026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sund H., Theorell H. Alcohol dehydrogenase. In: Boyer P. D., editor. The Enzymes. 2nd ed. New York: Academica; 1963. p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li T. K., Vallee B. L. Active-center peptides of liver-alcohol dehydrogenase. I. The sequence surrounding the active cysteinyl residues. Biochemistry. 1964;3:869–873. doi: 10.1021/bi00894a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris I. Structure and catalytic activity of alcohol dehydrogenases. Nature. 1964;203:30–34. doi: 10.1038/203030a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jörnvall H. Partial similarities between yeast and liver alcohol dehydrogenases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1973;70:2295–2298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.8.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jörnvall H. The primary structure of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1977;72:425–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jörnvall H., Eklund H., Brändén C.-I. Subunit conformation of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:8414–8419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramaswamy S., Kratzer D.A., Hershey A.D., Rogers P.H., Arnone A., Eklund H., Plapp B. V. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic studies of Saccharomyces cerevisiae alcohol dehydrogenase I. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;235:777–779. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wills C., Jörnvall H. Amino acid substitutions in two functional mutants of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. Nature. 1979;279:734–736. doi: 10.1038/279734a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saliola M., Shuster J. R., Falcone C. The alcohol dehydrogenase system in the yeast, Kluyveromyces lactis. Yeast. 1990;6:193–204. doi: 10.1002/yea.320060304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leskovac V., Trivic S., Pericin D. The three zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenases from baker's yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2002;2:481–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2002.tb00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young T., Williamson V., Taguchi A., Smith M., Sledziewski A., Russell D., Osterman J., Denis C., Cox D., Beier D. The alcohol dehydrogenase genes of the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation, structure, and regulation. Basic Life Sci. 1982;19:335–361. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4142-0_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young E. T., Pilgrim D. Isolation and DNA sequence of ADH3, a nuclear gene encoding the mitochondrial isozyme of alcohol dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1985;5:3024–3034. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.11.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williamson V. M., Paquin C. E. Homology of Saccharomyces cerevisiaeADH4to an iron-activated alcohol dehydrogenase from Zymomonas mobilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1987;209:374–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00329668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunter G. D., Jones I. G., Sealy-Lewis H.M. The cloning and sequencing of the alcB gene, coding for alcohol dehydrogenase II, in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Genet. 1996;29:122–129. doi: 10.1007/BF02221575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelly J. M., Drysdale M. R., Sealy-Lewis H.M., Jones I. G., Lockington R. A. Alcohol dehydrogenase III in Aspergillus nidulans is anaerobically induced and post-transcriptionally regulated. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1990;222:323–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00633836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green D.W., Sun H.W., Plapp B. V. Inversion of the substrate specificity of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:7792–7798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore C. H., Taylor S. S., Smith M. J., Hartley B. S. Atlas of Protein Sequence and Structure. 1974;5(suppl.3):68. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thatcher D. R., Sawyer L. Secondary-structure prediction from the sequence of Drosophila melanogaster (fruitfly) alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochem. J. 1980;187:884–886. doi: 10.1042/bj1870884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jörnvall H., Persson B., Krook M., Atrian S., Gonzalez-Duarte R., Jeffery J., Ghosh D. Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR) Biochemistry. 1995;34:6003–6013. doi: 10.1021/bi00018a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pauly T. A., Ekstrom J. L., Beebe D. A., Chrunyk B., Cunningham D., Griffor M., Kamath A., Lee S. E., Madura R., McGuire D., et al. X-ray crystallographic and kinetic studies of human sorbitol dehydrogenase. Structure. 2003;11:1071–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeffery J., Chesters J., Mills C., Sadler P. J., Jörnvall H. Sorbitol dehydrogenase is a zinc enzyme. EMBO J. 1984;3:357–360. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeffery J., Jörnvall H. Sorbitol dehydrogenase. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1988;61:47–106. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sibout R., Eudes A., Mouille G., Pollet B., Lapierre C., Jouanin L., Seguin A. Cinnamyl alcohol Dehydrogenase-C and -D are the primary genes involved in lignin biosynthesis in the floral stem of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2059–2076. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.030767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Youn B., Camacho R., Moinuddin S. G., Lee C., Davin L. B., Lewis N. G., Kang C. Crystal structures and catalytic mechanism of the Arabidopsis cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenases AtCAD5 and AtCAD4.Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:1687–1697. doi: 10.1039/b601672c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knight M. E., Halpin C., Schuch W. Identification and characterisation of cDNA clones encoding cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase from tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992;19:793–801. doi: 10.1007/BF00027075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brill E. M., Abrahams S., Hayes C. M., Jenkins C. L., Watson J. M. Molecular characterisation and expression of a wound-inducible cDNA encoding a novel cinnamylalcohol dehydrogenase enzyme in lucerne (Medicago sativa L.) Plant Mol. Biol. 1999;41:279–291. doi: 10.1023/a:1006381630494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sibout R., Eudes A., Pollet B., Goujon T., Mila I., Granier F., Seguin A., Lapierre C., Jouanin L. Expression pattern of two paralogs encoding cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenases in Arabidopsis: isolation and characterization of the corresponding mutants. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:848–860. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tobias C. M., Chow E. K. Structure of the cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase gene family in rice and promoter activity of a member associated with lignification. Planta. 2005;220:678–688. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim S. J., Kim K.W., Cho M. H., Franceschi V. R., Davin L. B., Lewis N. G. Expression of cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenases and their putative homologues during Arabidopsis thaliana growth and development: lessons for database annotations? Phytochemistry. 2007;68:1957–1974. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williamson J.D., Stoop J.M., Massel M.O., Conkling M.A., Pharr D. M. Sequence analysis of a mannitol dehydrogenase cDNA from plants reveals a function for the pathogenesis-related protein ELI3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:7148–7152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kiedrowski S., Kawalleck P., Hahlbrock K., Somssich I. E., Dangl J. L. Rapid activation of a novel plant defense gene is strictly dependent on the Arabidopsis RPM1 disease resistance locus. EMBO J. 1992;11:4677–4684. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stoop J. M., Pharr D. M. Partial purification and characterization of mannitol: mannose 1-oxidoreductase from celeriac (Apium graveolens var. rapaceum) roots. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992;298:612–619. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stoop J.M., Williamson J. D., Conkling M. A., Pharr D. M. Purification of NAD-dependent mannitol dehydrogenase from celery suspension cultures. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1219–1225. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Larroy C., Fernandez M. R., Gonzalez E., Pares X., Biosca J. A. Characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae YMR318C (ADH6) gene product as a broad specificity NADPH-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase: relevance in aldehyde reduction. Biochem. J. 2002;361:163–172. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larroy C., Pares X., Biosca J. A. Characterization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae NADP(H)-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase (ADHVII), amember of the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase family. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:5738–5745. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raoult D., Audic S., Robert C., Abergel C., Renesto P., Ogata H., La Scola B., Suzan M., Claverie J. M. The 1.2-megabase genome sequence of Mimivirus. Science. 2004;306:1344–1350. doi: 10.1126/science.1101485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yokomizo T., Izumi T., Takahashi T., Kasama T., Kobayashi Y., Sato F., Taketani Y., Shimizu T. Enzymatic inactivation of leukotriene B4 by a novel enzyme found in the porcine kidney: purification and properties of leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:18128–18135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamamoto T., Yokomizo T., Nakao A., Izumi T., Shimizu T. Immunohistochemical localization of guinea-pig leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase/15-ketoprostaglandin 13-reductase. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:6105–6113. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pettitt T. R., Rowley A. F., Barrow S. E. Synthesis of leukotriene B and other conjugated triene lipoxygenase products by blood cells of the rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989;1003:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(89)90090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bresell A., Weinander R., Lundqvist G., Raza H., Shimoji M., Sun T. H., Balk L., Wiklund R., Eriksson J., Jansson C., et al. Bioinformatic and enzymatic characterization of the MAPEG superfamily. FEBS J. 2005;272:1688–1703. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Babiychuk E., Kushnir S., Belles-Boix E., Van Montagu M., Inze D. Arabidopsis thaliana NADPH oxidoreductase homologs confer tolerance of yeasts toward the thioloxidizing drug diamide. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26224–26231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hori T., Yokomizo T., Ago H., Sugahara M., Ueno G., Yamamoto M., Kumasaka T., Shimizu T., Miyano M. Structural basis of leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase/15-oxo-prostaglandin 13-reductase catalytic mechanism and a possible Src homology 3 domain binding loop. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:22615–22623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang L., Zhang F., Huo K. Cloning and characterization of a novel splicing variant of the ZADH1 gene. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2003;103:79–83. doi: 10.1159/000076293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Edgar A. J. The human L-threonine 3-dehydrogenase gene is an expressed pseudogene. BMC Genet. 2002;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li S. J., Cronan J. E., Jr. The gene encoding the biotin carboxylase subunit of Escherichia coli acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:855–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levius O., Linial M. fromTorpedo synaptic vesicles is a calcium binding protein: a study in bacterial expression systems. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1993;13:483–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00711457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Linial M., Levius O. The protein VAT-1 from Torpedo electric organ exhibits an ATPase activity. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;152:155–157. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90506-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hayess K., Kraft R., Sachsinger J., Janke J., Beckmann G., Rohde K., Jandrig B., Benndorf R. Mammalian protein homologous to VAT-1 of Torpedo californica: isolation from Ehrlich ascites tumor cells, biochemical characterization, and organization of its gene. J Cell Biochem. 1998;69:304–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loeb-Hennard C., Cousin X., Prengel I., Kremmer E. Cloning and expression pattern of vat-1 homolog gene in zebrafish. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2004;5:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rao P. V., Zigler J. S., Jr. Zeta-crystallin from guinea pig lens is capable of functioning catalytically as an oxidoreductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1991;284:181–185. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90281-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rao P.V., Gonzalez P., Persson B., Jörnvall H., Garland D., Zigler J. S., Jr. Guinea pig and bovine zetacrystallins have distinct functional characteristics highlighting replacements in otherwise similar structures. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5353–5362. doi: 10.1021/bi9622985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mano J., Babiychuk E., Belles-Boix E., Hiratake J., Kimura A., Inze D., Kushnir S., Asada K. A novel NADPH:diamide oxidoreductase activity in Arabidopsis thaliana P1 zeta-crystallin. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:3661–3671. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thorn J. M., Barton J. D., Dixon N. E., Ollis D. L., Edwards K. J. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli QOR quinone oxidoreductase complexed with NADPH. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;249:785–799. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim M. Y., Lee H. K., Park J. S., Park S. H., Kwon H. B., Soh J. Identification of a zeta-crystallin (quinone reductase)-like 1 gene (CRYZL1) mapped to human chromosome 21q22.1. Genomics. 1999;57:156–159. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yamazoe M., Shirahige K., Rashid M. B., Kaneko Y., Nakayama T., Ogasawara N., Yoshikawa H. A protein which binds preferentially to single-stranded core sequence of autonomously replicating sequence is essential for respiratory function in mitochondrial of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:15244–15252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Masuda N., Yasumo H., Furusawa T., Tsukamoto T., Sadano H., Osumi T. Nuclear receptor binding factor-1 (NRBF-1), a protein interacting with awide spectrum of nuclear hormone receptors. Gene. 1998;221:225–233. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miinalainen I. J., Chen Z. J., Torkko J. M., Pirila P. L., Sormunen R. T., Bergmann U., Qin Y. M., Hiltunen J. K. Characterization of 2-enoyl thioester reductase from mammals: an ortholog of YBR026p/MRF1'p of the yeast mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis type II. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20154–20161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mathur M., Kolattukudy P. E. Molecular cloning and sequencing of the gene for mycocerosic acid synthase, a novel fatty acid elongating multifunctional enzyme, from Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:19388–19395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang F., Haydock S. F., Mironenko T., Spiteller D., Li Y., Spencer J. B. The neomycin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces fradiae NCIMB 8233: characterisation of an aminotransferase involved in the formation of 2-deoxystreptamine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:1410–1418. doi: 10.1039/b501199j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kudo F., Yamamoto Y., Yokoyama K., Eguchi T., Kakinuma K. Biosynthesis of 2-deoxystreptamine by three crucial enzymes in Streptomyces fradiae NBRC 12773. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2005;58:766–774. doi: 10.1038/ja.2005.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hu W. H., Hausmann O. N., Yan M. S., Walters W. M., Wong P. K., Bethea J. R. Identification and characterization of a novel Nogo-interacting mitochondrial protein (NIMP) J. Neurochem. 2002;81:36–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kumar A., Shen P. S., Descoteaux S., Pohl J., Bailey G., Samuelson J. Cloning and expression of anNADP(+)-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase gene of Entamoeba histolytica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:10188–10192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ismaiel A. A., Zhu C. X., Colby G. D., Chen J. S. Purification and characterization of a primary-secondary alcohol dehydrogenase from two strains of Clostridium beijerinckii. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:5097–5105. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5097-5105.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ito K., Takahashi M., Yoshimoto T., Tsuru D. Cloning and high-level expression of the glutathione-independent formaldehyde dehydrogenase gene from Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:2483–2491. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2483-2491.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tanaka N., Kusakabe Y., Ito K., Yoshimoto T., Nakamura K. T. Crystal structure of formaldehyde dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas putida: the structural origin of the tightly bound cofactor in nicotinoprotein dehydrogenases. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;324:519–533. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Speer B. S., Chistoserdova L., Lidstrom M. E. Sequence of the gene for aNAD(P)-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase (class III alcohol dehydrogenase) from a marine methanotroph Methylobacter marinus A45. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1994;121:349–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gonzalez E., Fernandez M. R., Larroy C., Sola L., Pericas M. A., Pares X., Biosca J. A. Characterization of a (2R,3R)-2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase as the Saccharomyces cerevisiae YAL060W gene product: disruption and induction of the gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35876–35885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bausch C., Peekhaus N., Utz C., Blais T., Murray E., Lowary T., Conway T. Sequence analysis of the GntII (subsidiary) system for gluconate metabolism reveals a novel pathway for l-idonic acid catabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:3704–3710. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3704-3710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Aramaki H., Koga H., Sagara Y., Hosoi M., Horiuchi T. Complete nucleotide sequence of the 5-exo-hydroxycamphor dehydrogenase gene on the CAM plasmid of Pseudomonas putida (ATCC 17453) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1174:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shaw J. P., Rekik M., Schwager F., Harayama S. Kinetic studies on benzyl alcohol dehydrogenase encoded by TOL plasmid pWWO: a member of the zinc-containing long chain alcohol dehydrogenase family. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:10842–10850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jendrossek D., Steinbuchel A., Schlegel H. G. Alcohol dehydrogenase gene from Alcaligenes eutrophus: subcloning, heterologous expression in Escherichia coli, sequencing, and location of Tn5 insertions. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:5248–5256. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.11.5248-5256.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bresell A., Persson B. Characterization of oligopeptide patterns in large protein sets. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:346. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Flicek P., Aken B. L., Beal K., Ballester B., Caccamo M., Chen Y., Clarke L., Coates G., Cunningham F., Cutts T., et al. Ensembl 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D707–714. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wheeler D. L., Barrett T., Benson D. A., Bryant S. H., Canese K., Chetvernin V., Church D. M., Dicuccio M., Edgar R., Federhen S., et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D13–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Peterson J. D., Umayam L. A., Dickinson T., Hickey E. K., White O. The Comprehensive Microbial Resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:123–125. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gonzalez-Duarte R., Albalat R. Merging protein, gene and genomic data: the evolution of the MDR-ADH family. Heredity. 2005;95:184–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]