Abstract

Background

Volatile general anesthetics inhibit neurotransmitter release by an unknown mechanism. A mutation in the presynaptic SNARE protein syntaxin-1A was previously shown to antagonize the anesthetic isoflurane in C. elegans. The mechanism underlying this antagonism may identify presynaptic anesthetic targets relevant to human anesthesia.

Methods

Sensitivity to isoflurane concentrations in the human clinical range was measured in locomotion assays on adult C. elegans. Sensitivity to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor aldicarb was used as an assay for the global level of C. elegans neurotransmitter release. Comparisons of isoflurane sensitivity (measured by the EC50) were made by simultaneous curve-fitting and F-test as described by Waud.

Results

Expression of a truncated syntaxin fragment (residues 1-106) antagonized isoflurane sensitivity in C. elegans. This portion of syntaxin interacts with the presynaptic protein UNC-13, suggesting the hypothesis that truncated syntaxin binds to UNC-13 and antagonizes an inhibitory effect of isoflurane on UNC-13 function. Consistent with this hypothesis, overexpression of UNC-13 suppressed the isoflurane resistance of the truncated syntaxins, and unc-13 loss-of-function mutants were highly isoflurane resistant. Normal anesthetic sensitivity was restored by full-length UNC-13, by a shortened form of UNC-13 lacking a C2 domain, but not by a membrane-targeted UNC-13 that might bypass isoflurane inhibition of membrane translocation of UNC-13. Isoflurane was found to inhibit synaptic localization of UNC-13.

Conclusions

These data show that UNC-13, an evolutionarily-conserved protein that promotes neurotransmitter release, is necessary for isoflurane sensitivity in C. elegans and suggest that its vertebrate homologs may be a component of the general anesthetic mechanism.

Summary Statement: Mutations in unc-13, which encodes an evolutionarily conserved presynaptic protein, abolish isoflurane sensitivity. Genetic and cell biological evidence indicate that isoflurane blocks membrane targeting of the UNC-13 protein thereby inhibiting its promotion of neurotransmitter release.

Introduction

At clinical concentrations, volatile general anesthetics (VAs) like isoflurane have multiple electrophysiological effects that depress overall nervous system activity and likely contribute to their mechanism of action 1. By clinical concentrations, we mean concentrations of anesthetic that are in the range used in human clinical practice; 2 minimal alveolar concentration (MAC) of isoflurane produces an aqueous concentration of 0.62 mM. Thus, we operationally define anesthetic concentrations less than 0.6 mM as clinical concentrations. One of the actions of clinical concentrations of VAs is inhibition of neurotransmitter release 2. The mechanism of this inhibition is poorly understood. Release of glutamate and gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) from rat cortical synaptosomes is inhibited by VAs and inhibition of sodium channels blocks the effect of VAs on 4-aminopyridine-evoked release but not on basal release 3,4. VAs more efficaciously inhibit glutamate release compared to GABA release from synaptosomes. Sodium channel blockade does not explain the differential inhibition by VAs of the basal release of glutamate and GABA 3. In rat hippocampus, VAs have been shown to inhibit glutamatergic transmission by a primarily presynaptic mechanism 5. Subsequent studies confirmed a presynaptic VA action in the hippocampus and attributed approximately a third of the inhibition of glutamate release to a reduction in the action potential and by default the remainder of the effect to downstream targets such as the transmitter release machinery 6,7. As was found with synaptosomes, VAs selectively inhibited glutamate versus GABA release 6.

Consistent with a presynaptic anesthetic mechanism in the nematode C. elegans, we found in a screen through existing C. elegans mutants that mutations reducing levels of neurotransmitter release conferred hypersensitivity to the VAs halothane and isoflurane 8 and mutations increasing transmitter release conferred resistance 9-11. These results could be explained if VAs inhibited excitatory neurotransmitter release. Indeed, isoflurane and halothane both produced behavioral and pharmacological effects resembling mutants with reduced excitatory neurotransmission 8 in that anesthetized animals moved sluggishly and were resistant to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor aldicarb. Aldicarb increases the steady state level of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction and thereby produces a depolarizing neuromuscular blockade; mutations or drugs that reduce acetylcholine release confer resistance to aldicarb 12.

In testing all available viable alleles of genes known to regulate neurotransmitter release in C. elegans, we found one mutation in the C. elegans syntaxin-1A gene unc-64 that had an unexpected phenotype. unc-64(md130) (indicates a strain carrying the md130 mutation in the unc-64 gene) had reduced excitatory neurotransmission by behavioral, aldicarb sensitivity, and electrophysiological measurements 8,13, yet it was highly VA resistant 8. For example, its isoflurane EC50 was more than 5-fold that of wild type, making unc-64(md130) fully resistant to isoflurane concentrations in the clinical range. unc-64(md130) is 30-fold less sensitive to isoflurane than other unc-64 reduction-of-function alleles; thus, isoflurane resistance is not a general property of reduction of syntaxin function. The md130 mutation disrupts an intron donor splice sequence, resulting in a reduced level of full-length syntaxin and the production of novel truncated syntaxins 8. By Western blot, the relative ratio of full-length to truncated syntaxin is approximately 4:1 (Barbara Scott, B.S and CM Crowder, M.D., Ph.D, Dept. of Anesthesiology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA, written communication, March, 2007); thus, if truncated syntaxins are actually responsible for the anesthetic resistance, a relatively low total concentration of truncated syntaxin can antagonize anesthetic action.

Despite our previous report of isoflurane binding to syntaxin 14, several genetic results argue against the most direct model where the isoflurane resistance of the md130 mutation is due to deletion of the isoflurane binding sites on syntaxin. First, the isoflurane resistance phenotype of md130 is semidominant 8. Second, an unc-64 null mutation has no anesthetic phenotype as a heterozygote 8. In other words, unlike with the md130 mutation in the background, one copy of wild type syntaxin confers normal isoflurane sensitivity; thus, the md130 mutation does not behave genetically as if the isoflurane resistance is due to loss of a binding site. Third, structural and cell biological studies strongly support a model where the portion of syntaxin deleted by the md130 mutation is absolutely required for the normal function of syntaxin 15. Thus, in unc-64(md130), which expresses both wild type and truncated protein, the loss of binding of isoflurane to the truncated form would have no consequence since it cannot serve as a functional syntaxin anyway. Further, the remaining wild type syntaxin in the mutant would still bind isoflurane as usual and should be affected normally. Rather than the md130 mutation deleting an isoflurane binding site, the most parsimonious hypothesis is that these truncated syntaxins act essentially as VA antagonists against the anesthetic target. Here we show that truncated syntaxins do in fact antagonize isoflurane action, identify the likely protein target for truncated syntaxin, find that this protein is necessary for VA sensitivity, and show that VAs act to alter its synaptic localization. Thus, this protein fits criteria for a functional VA target.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans strains and transformants

A list of strains used in the work is given in Table 1. N2 var Bristol was the wild type strain and the genetic background for all mutants 16. tom-1(ok285) was obtained from the C. elegans knockout consortium; ok285 is a 1580 bp tom-1 deletion, which removes all or part of 4 exons in the center of the gene 17. tom-1(ok285) unc-13(e376);unc-64(js115);oxIs34 was constructed by selecting Unc non-Dpy progeny segregating from dpy-5(e51) + e376/+ ok285 + hermaphrodites and homozygosing for ok285 e376. unc-64(js115);oxIs34[unc-64(L166A/E167A);Pmyo-2::GFP]18 males were then crossed with ok285 e376 and the best moving Unc Green second generation progeny were clonally passaged. The presence of the homozygoustom-1(ok285) deletion was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the mutant gene; the homozygous js115 mutation was confirmed by outcrossing from oxIs34 and observing segregation of dead larval progeny on all second-generation broods. tom-1(ok285) unc-13(s69);unc-64(js115);oxIs34 was constructed similarly and was a gift from Janet Richmond, Ph.D., Department of Biological Sciences, University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA. For heterozygous unc-64(md130) animals, non-Unc non-Bli animals segregating from md130+/+bli-5 were used. mdIs3[unc-13(+);snb-1::GFP] is an integrant of mdEx43 19 and was a gift from Kenneth G. Miller, Ph.D. (Program in Molecular and Cell Biology, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK, USA). mdIs3;gcEx45[pTXmd130] and mdIs3;gcEx55[pTX1−107] were constructed by crossing gcEx45 or gcEx55 males into mdIs3 and passaging progeny with both Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) cotransformation markers until homozygous for mdIs3. unc-13(s69);oxIs78[myr::unc-13S::GFP;ccGFP] was a gift from Erik Jorgensen, Ph.D. and Kim Schuske, Ph.D., Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA and was generated by injection and integration of KP280 20; the presence of the myristoylation consensus sequence was confirmed by sequencing the integrated transgene. The truncated syntaxin transformants were generated by gonad injection of 50 – 100 ng/μl of the the particular pTX plasmid along with 40 ng/μl of the hypodermal GFP coinjection marker pPHgfp-1 21 into N2 and selection of stably transformed lines.

Table 1.

Strains list

| Strain | Genotype | Mutation | Transforming plasmid | Transforming protein | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | wild type | None | None | None | 16 |

| MC339 | unc-64(md130) | Truncated syntaxin1-227 +few novel aa + reduced wild type syntaxin | None | None | 8,13 |

| MC270 | md130 +/+ bli-5 | heterozygous md130 products | None | None | 8,13 |

| MC72 | unc-64(md130); gcEx5 | Truncated syntaxin1-227 +few novel aa + reduced wild type syntaxin | pTXfull-length = pTX21; pPH::GFP-1 | Full-length wild type UNC-64; hypodermal GFP | 8,13 |

| MC185 | gcEx85 | None | pTXmd130; pPH::GFP-1 | md130 product; hypodermal GFP | 21 |

| MC105 | gcEx95 | None | pTX1-258; pPH::GFP-1 | Truncated syntaxin residues 1-258; hypodermal GFP | 21 |

| MC153, MC155 | gcEx53, gcEx55 | None | pTX1-227; pPH::GFP-1 | Truncated syntaxin residues 1-227; hypodermal GFP | 21 |

| MC150, MC151, MC152, MC184, MC187 | gcEx50, gcEx51, gcEx52, gcEx84, gcEx87 | None | pTX1-158; pPH::GFP-1 | Truncated syntaxin residues 1-158; hypodermal GFP | 21 |

| MC139, MC158, MC159, MC232 | gcEx91, gcEx58, gcEx59, gcEx90 | None | pTX1-106; pPH::GFP-1 | Truncated syntaxin residues 1-106; hypodermal GFP | 21 |

| MC233, MC234, MC271 | gcEx92, gcEx93, gcEx94 | None | pTX1-86; pPH::GFP-1 | Truncated syntaxin residues 1-86; hypodermal GFP | 21 |

| MC176, MC177, MC178 | gcEx76, gcEx77, gcEx78 | None | pTX1-64; pPH::GFP-1 | Truncated syntaxin residues 1-64; hypodermal GFP | 21 |

| NM1968 | slo-1(js379 null) | Loss of SLO-1 BK channel | None | None | 9,26 |

| PS1762 | goa-1(sy192 lf) | Dominant negative Go-alpha protein | None | None | 11 |

| VC223 | tom-1(ok285 null) | Loss of tomosyn | None | None | 17 |

| EG1985 | unc-64(js115 null); oxIs34 | Loss of syntaxin | Punc-64(L166A/E167A); Pmyo-2::GFP | Open Syntaxin; pharynx GFP | 18 |

| MC272 | tomo-1(ok285 null); unc-64(js115 null); oxIs34 | Loss of tomosyn; Loss of syntaxin | Punc-64(L166A/E167A); Pmyo-2::GFP | Open Syntaxin; pharynx GFP | 17,18 |

| MC261 | tomo-1(ok285 null) unc-13(e376);unc-64(js115 null);oxIs34 | Loss of tomosyn; Reduction of UNC-13; Loss of syntaxin | Punc-64(L166A/E167A); Pmyo-2::GFP | Open Syntaxin; pharynx GFP | 17,18,19 |

| MC275 | tomo-1(ok285 null) unc-13(s69); unc-64(js115 null); oxIs34 | Loss of tomosyn; Loss of UNC-13; Loss of syntaxin | Punc-64(L166A/E167A); Pmyo-2::GFP | Open Syntaxin; pharynx GFP | 17,18,19 |

| MC344 | unc-10(md1117 null); unc-64(js115 null); oxIs34 | Loss of UNC-10 - RIM; Loss of syntaxin | Punc-64(L166A/E167A); Pmyo-2::GFP | Open Syntaxin; pharynx GFP | 45 |

| CB55 | unc-2(e55 null) | Loss of non-L-type Ca++ Channel | None | None | 29,36 |

| BC168 | unc-13(s69 null) | Loss of UNC-13 | None | None | 19 |

| CB376 | unc-13(e376 lf) | Reduction of UNC-13 | None | None | 19 |

| KP3299 | unc-13(s69 null); nuIs46 | Loss of UNC-13 | KP268[UNC-13S::GFP]; ccGFP | UNC-13S::GFP; coelomocyte GFP | 19,23 |

| EG2840 | unc-13(s69 null); oxIs78 | Loss of UNC-13 | KP280[myr::unc-13S::GFP]; ccGFP | Myristoylated UNC-13S::GFP; coelomocyte GFP | 19,20 |

| RM2333 | mdIs3 | None | C44E1; Psnb-1::GFP - integrant of mdEx43 | wild type UNC-13; neuronal GFP | 19 |

| MC273 | mdIs3;gcEx37 | None | C44E1; Psnb-1::GFP; pTXmd130; pPH::GFP-1 | wild type UNC-13; neuronal GFP; md130 truncated syntaxin; hypodermal GFP | 19,21 |

| MC274 | mdIs3;gcEx58 | None | C44E1; Psnb-1::GFP; pTX1-106; pPH::GFP-1 | wild type UNC-13; neuronal GFP; truncated syntaxin 1-106; hypodermal GFP | 19,21 |

More than one strain in a row represents multiple transformants with the same plasmid; If - loss-of-function but not necessarily null Is - indicated a chromosomally integrated array, Ex - indicates an extrachromosomal array; aa = amino acid

Plasmids constructs

The parent plasmid for all syntaxin plasmid constructs was pTX21, which contains a 12 kb PstI – MfeI rescuing genomic fragment from pTX20 13 inserted into pBluescript (KS−) and includes all known unc-64 transcripts and transcriptional regulatory regions. pTXmd130 was generated by polymerase chain reaction amplification from unc-64(md130) genomic DNA and insertion of an NheI – NsiI fragment spanning the md130 mutation into NheI – NsiI cut pTX21. pTX1−258, pTX1−227, pTX1−158, pTX1−106, pTX1−86, and pTX1−64 were all made by one or two rounds of oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene Quickchange, Stratagene, Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA) of pTX21 to generate a stop codon at the desired site. All plasmid constructs were sequenced to confirm the mutation.

Behavioral and drug assays

Locomotion was measured on 2% agar plates as the fraction of animals that dispersed in 40 minutes from the center of a 9.5 cm plate to the edge that was seeded with bacteria (the dispersal index) 10, by the rate of body bends 9, or by the speed of movement across an agar plate as described previously 22. unc-64(md130) is resistant in all three assays (Laura B. Metz, B.S., Dept. of Anesthesiology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA, written communication, March, 2007). However, the slow and slowest strains did not move well enough to disperse to the edge of the dispersal plates, and the slowest strains had weak and infrequent body bends that produce excessively variable results in body bend assays. Thus, we used the relatively easy body bends assay for slow strains and the highly quantitative but tedious speed assay for the slowest strains. The dispersal assay was used for normally moving strains. Aldicarb sensitivity was measured by the rate of paralysis on 0.35 mM aldicarb-containing agar plates 23. Isoflurane were delivered and the concentrations measured as described previously 24. Locomotion as measured by one of the three assays was plotted against anesthetic concentration; concentration/response data were fitted to a modified Hill equation to calculate EC50 (the anesthetic concentration at which the reduction in locomotion was half maximal) and slope 24.

Scoring of UNC-13::GFP puncta density

L4 larval stage animals were exposed on agar plates to 0 or 1 μg/ml phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) for 1 hour. Subsequently, the plates were placed into glass chambers containing 0 or 2 vol% isoflurane for an additional 1 hr then transferred rapidly by platinum wire onto a thin agarose pad into a fresh drop of M9 buffer 16 containing 0 or 1mM isoflurane (≈ 1.9 vol% isoflurane) and 10 mM azide. Agar pads were rapidly sealed with a glass coverslip. The dorsal nerve cord was imaged within five minutes of removal of worms from the glass chamber. Preliminary experiments showed that isoflurane without azide remained effective at producing sluggish movement under these conditions for at least five minutes (CM Crowder, M.D., Ph.D., Dept. of Anesthesiology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA, written communication, March, 2007). The Images were obtained on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc, Thornwood, NY, USA) using a 63X Plan-Apo 1.4na oil immersion lens and a Chroma 41017 Endow GFP filter set and captured using a Retiga Exi CCD camera coupled to Q-Capture Pro software (QImaging, Inc, Surrey, BC, Canada) with identical capture settings for all animals. Image files were coded and scored using Scion NIH image software (Scion, Corporation, Frederick, MD, USA) by an observer blinded to condition. For each animal, puncta were manually counted along the longest length of dorsal nerve cord in the focal plane. The distance of dorsal nerve cord scored was measured by conversion of pixel number to micrometers. Puncta density was then expressed for each animal as puncta/100 μm of dorsal nerve cord.

Statistical analysis

All statistical comparisons were made using GraphPad Prism 4 software (GraphPad, Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). EC50s were compared for statistical differences by simultaneous curve fitting as described by Waud 25 using GraphPad Prism 4. For a particular strain, EC50s were estimated by pooling all of the data for that strain; the error values following the EC50 values are the error of the fit. Locomotion rates were compared by two-sided t-test. GFP puncta density was compared by two-sided t-test. The threshold for statistical significance for all tests was set at p < 0.01.

Results

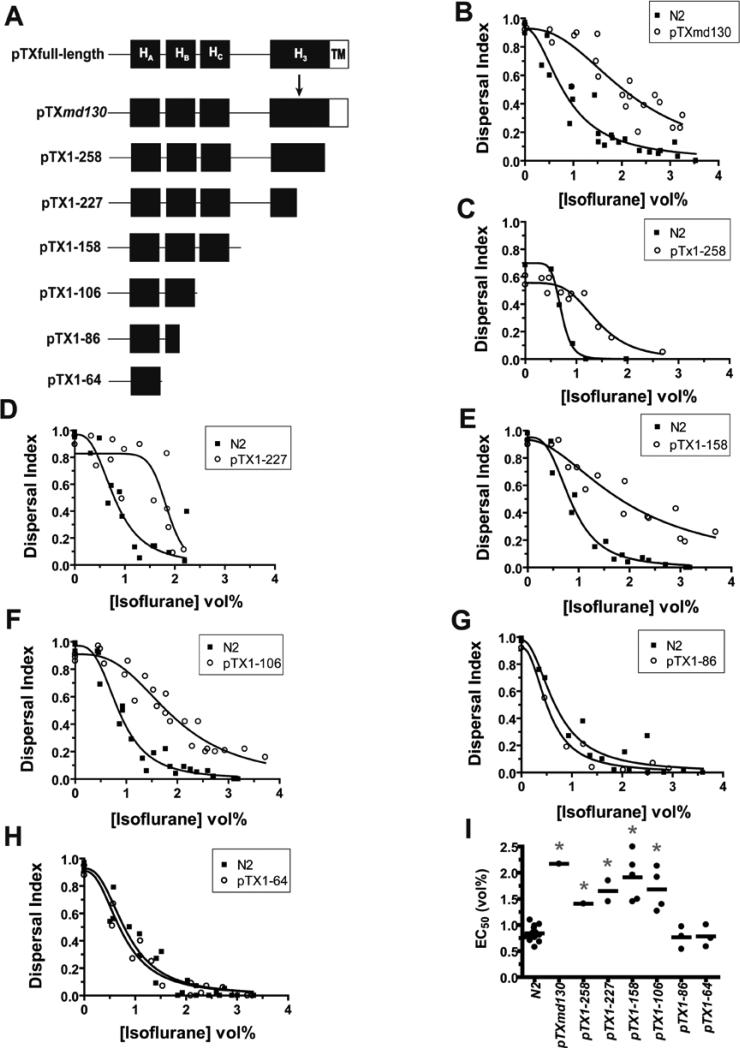

To test whether the truncated syntaxin was responsible for the VA resistance phenotype and, if so, to define the structural requirements for its antagonism, we generated a series of plasmids expressing truncated syntaxins under the native unc-64 promoter , and tested the isoflurane sensitivity of the transformed animals (fig. 1). As expected, transformation of wild type C. elegans with pTXmd130, which contains the original md130 mutation, conferred isoflurane resistance (fig. 1B,I). pTX1−258, which expresses a truncated syntaxin longer than that produced by md130 and without the additional amino acids produced by read through into the intron, also conferred isoflurane resistance (fig. 1C,I). Wild type animals transformed with pTX1−227, which introduces a stop codon immediately 5’ to the splice donor site mutated by md130, were also isoflurane resistant (fig 1D,I). The isoflurane resistance produced by both pTX1−258 and pTX1−227 demonstrates conclusively that truncated unc-64 syntaxin does antagonize VA action and that the novel amino acids produced by the original md130 mutation are not required for VA antagonism. Transformation with plasmids expressing increasingly smaller truncated syntaxins, pTX1−158, pTX1−106, showed that a fragment encoding only the HAB domains of syntaxin was sufficient to produce resistance (fig. 1E,F,I). However, further truncation removing all or half of HB, pTX1−64 or pTX1−86, abolished the VA resistance-conferring activity (fig. 1G,H,I). Thus, C-terminally truncated syntaxin does indeed antagonize VA action and only a relatively small N-terminal fragment is sufficient for this action. This syntaxin fragment does not include the Soluble NSF Attachment Protein Receptor ( SNARE) domain, encoded by residues 185 – 255, that is thought to interact with the majority of syntaxin-interacting proteins.

Fig. 1.

Syntaxin structural requirements for isoflurane antagonism. (A) Predicted syntaxin products generated from transforming plasmid constructs. The relative locations of the four helical domains, HA, HB, HC, and H3, and the C-terminal transmembrane domain, TM, are shown. pTXmd130 contains the g-a splice donor mutation in the 6th intron following codon 228 (position denoted by arrow) found in unc-64(md130) (B) Isoflurane sensitivity of locomotion (dispersal index) of a pTXmd130 transformed strain vs that of the concurrently tested wild-type strain N2. EC50s: N2 – 0.84 ± 0.09, pTXmd130 – 2.17 ± 0.18 - p < 0.0001. (C) Isoflurane sensitivity of pTX1−258 vs N2. EC50s: N2 – 0.71 ± 0.02, pTX1−258 – 1.41 ± 0.09 - p < 0.0001. (D) Isoflurane sensitivity of pTX1−227 vs N2. EC50s: N2 – 0.81 ± 0.10, pTX1−227 – 1.85 ± 0.09 - p < 0.0003. (E) Isoflurane sensitivity of pTX1−158 vs N2. EC50s: N2 – 0.86 ± 0.05, pTX1−158 – 1.96 ± 0.20 - p < 0.0001. (F) Isoflurane sensitivity of pTX1−106 vs N2. EC50s: N2 – 0.87 ± 0.05, pTX1−106 – 1.92 ± 0.09 - p < 0.0001. (G) Isoflurane sensitivity of pTX1−86 vs N2. EC50s: N2 – 0.68 ± 0.09, pTX1−86 – 0.54 ± 0.06 - p = 0.24. (H) Isoflurane sensitivity of pTX1−64 vs N2. EC50s: N2 – 0.75 ± 0.06, pTX1−65 – 0.83 ± 0.07 - p = 0.45. (I) Summary scatter plot of all transformants. Each point represents the EC50 derived from the pooled concentration response data for each independently transformed strain except for N2 where each point represents the EC50 for a particular experiment. * p < 0.01 for each transformed strain versus the concurrently measured N2 EC50. All comparisons by shared-parameter simultaneous curve-fitting.

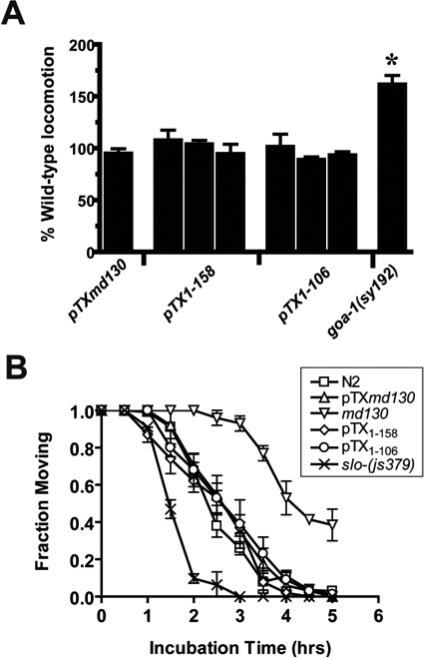

We have previously shown that mutations that increase transmitter release in C. elegans produce resistance to VAs 9,11. Thus, an alternative to the hypothesis that the truncated syntaxin is a direct VA antagonist is that it indirectly antagonizes VA action by increasing synaptic transmitter release. We tested this hypothesis by measuring the locomotion and aldicarb sensitivity of three truncated syntaxin-expressing constructs that confer isoflurane resistance. Hyperactive locomotion and aldicarb hypersensitivity are indicative of increased neurotransmitter release 12. None of the transformants were significantly hyperactive or hypersensitive to aldicarb (fig. 2A,B). Movement data for the hyperactive mutant, goa-1(sy192) is included as a positive control for hyperactivity 11. Data for the original unc-64(md130), which is aldicarb resistant due to reduced levels of wild type syntaxin8,13, and slo-1(js379), which has a loss of function mutation in the BK Ca++-activated K+ channel that negatively regulates transmitter release 9,26, are included for positive controls for aldicarb resistance and hypersensitivity, respectively. Thus, we conclude that increased release of neurotransmitter is unlikely to be the mechanism whereby the truncated syntaxins produce VA resistance. We hypothesize that the truncated syntaxin interacts with another protein that regulates VA sensitivity and thereby antagonizes VAs.

Fig. 2.

VA resistance not due to enhancement of locomotion or neurotransmitter release. (A) Locomotion rates of age synchronized young adults from strains transformed with pTXmd130 (MC168), pTX1−158 (MC150, MC151, and MC152), and pTX1−106 (MC158, MC159, and MC139) was measured by the number of body bends/minute and normalized to concurrent wild-type N2 values. Values are mean ± sem of > 10 animals. The hyperactive locomotion mutant, goa-1(sy192), is shown as a positive control 1. * - significantly different from 100% @ p < 0.01, two-tailed t-test. (B) Aldicarb sensitivity of a subset of truncated syntaxin transformants. The fraction of animals moving after various incubation times on agar plates containing 0.35 mM aldicarb. Each point represents the mean ± sem of triplicate measurements of at least 30 animals/measurement. The aldicarb hypersensitive/isoflurane resistant strain slo-1(js379) and the aldicarb resistant/isoflurane resistant unc-64(md130) strain are shown for comparison 2-4 .

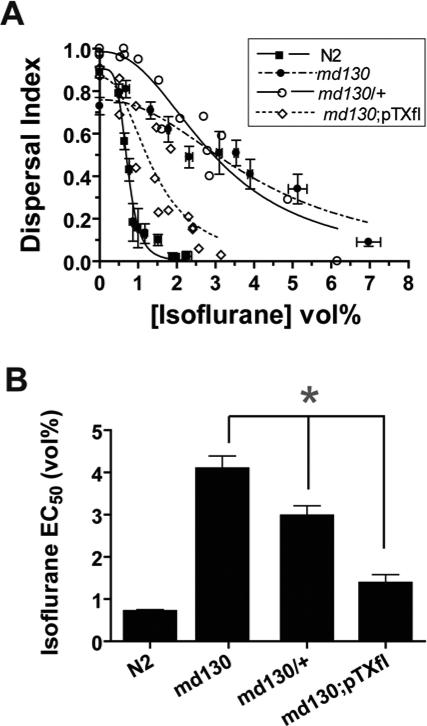

With what might the truncated syntaxin interact to antagonize VA action? We first considered whether the putative interacting protein also interacted with wild type syntaxin. If so, wild type syntaxin should compete with truncated syntaxin and restore VA sensitivity. Indeed, animals with one copy of the md130 mutation and one wild type allele were less resistant than homozygous md130 animal (fig. 3A,B). In addition, transformation of unc-64(md130) with a plasmid containing full-length syntaxin (pTXfl) partially rescues the VA resistance of md130. Thus, wild type and truncated syntaxin appear to compete for interaction with the putative protein controlling VA sensitivity.

Fig. 3.

Wild type syntaxin suppresses the VA resistance of truncated syntaxins. (A) Semidominance and rescue of the md130 isoflurane resistance. Locomotion measured by dispersal index is plotted as a function of [Isoflurane]. md130;pTX(fl) (MC72 – Table 1) is unc-64(md130) transformed with a full-length syntaxin genomic construct. md130/+ is heterozygous for the md130 mutation. (B) Summary of Isoflurane EC50's ± SE of the fit from A. * - p < 0.01

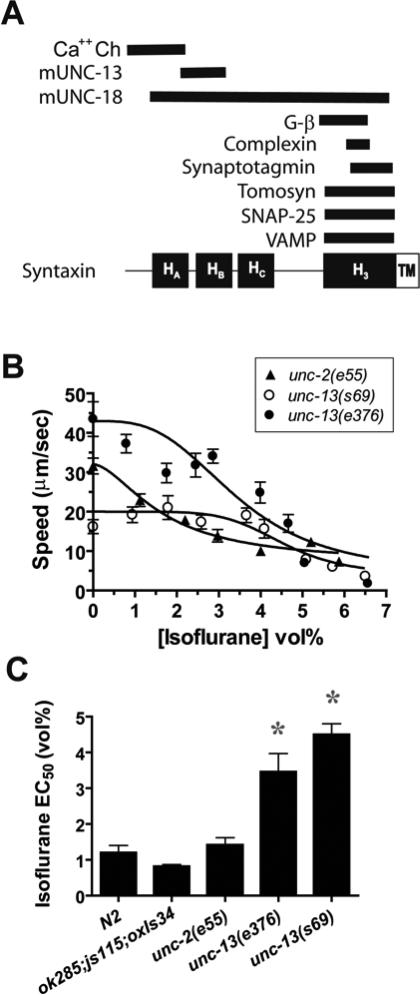

In vertebrates, two proteins that have been shown to interact with the N-terminal two helices of syntaxin are mUNC-13 and N-type calcium channels (fig. 4A) 27,28. C. elegans has one mUNC-13 homolog (UNC-13) and one N-type calcium channel (UNC-2). If one of these is the relevant VA target, a null mutant should be VA resistant. Both UNC-2 and UNC-13 promote transmitter release in C. elegans by a mechanism at least partially conserved in mammals 29-34. UNC-2 is thought to promote transmitter release by supplying calcium to the transmitter release machinery 29. The molecular mechanisms whereby UNC-13 promotes transmitter release are more complex. UNC-13 acts in steps after docking of synaptic vesicles with the presynaptic membrane and somehow prime vesicles so that they are competent for fusion 31. UNC-13's activity to promote vesicle fusion is partially dependent on interaction with syntaxin and may involve conversion of syntaxin from a closed conformation where the H3 helix containing the SNARE domain interacts tightly with its HABC domains to an open conformation where the H3 helix is free from its self interactions and available for binding to the SNARE domains of other SNARE proteins 18. However, catalyzing the transformation of syntaxin from a closed to open conformation does not appear to be the only function of UNC-13 35. We tested two severe unc-13 alleles19 and one null unc-2 allele29,36. In order to test the essentially paralyzed unc-13(lf) animals, we placed the unc-13 mutations in the background of three other mutations, tom-1(ok285 null), unc-64(L166A/E167A), and unc-64(js115 null). Both the tomosyn loss-of-function mutation, tom-1(ok285), and the unc-64(L166A/E167A) mutation, which favors the open conformation of syntaxin18, have been found to suppress partially the paralyzed phenotype of unc-13(lf) and when combined suppress the paralyzed unc-13(lf) phenotype adequately for anesthetic testing 17,37,38. Tomosyn is thought to form a complex with syntaxin, preventing its binding to the vesicular SNARE synaptobrevin/vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP) and thereby reducing neurotransmitter release 17. Open syntaxin may partially suppress unc-13(lf) by supplying the product of one of the normal functions of UNC-13, which is to convert closed syntaxin to open syntaxin 18. The unc-64(js115) mutation is included in the strain so that normal UNC-64 syntaxin does not compete with open syntaxin and thereby diminish the positive effect on locomotion of the unc-13 mutants 18.

Fig. 4.

UNC-13 is required for isoflurane sensitivity. (A) Proteins known to bind to syntaxin. The proteins are aligned with the syntaxin region, with which it binds. Ca++ Ch – N- and P- type calcium channels 5,6, mUNC-18 – mammalian UNC-18 7,8, mUNC-13 – mammalian UNC-13 9, Gβ – β-subunit of a G-protein 5, complexin 10,11, synaptotagmin 7, tomosyn 12, SNAP-25 13, Vesicle-associated Membrane Protein (VAMP) 13,14 (B) Isoflurane sensitivity of the locomotion of strains with loss-of-function mutations in unc-13 and unc-2. The full genotypes are: tom-1(ok285null) unc-13(s69lf);unc-64(js115 null);oxIs34[unc-64(L166A/E167A);Pmyo-2::GFP] , tom-1(ok285null) unc-13(e376lf);unc-64(js115 null);oxIs34[unc-64(L166A/E167A);Pmyo-2::GFP]/+, and unc-2(e55 null). Each point represents the mean ± sem of 10 animals. (C) Summary of Isoflurane EC50's ± SE of the fit from B. tom-1(ok285);unc-64(js115);oxIs34 is the genetic background for the unc-13 mutants and is shown for comparison along with the wild type strain N2. * - p < 0.01 vs N2 and ok285;js115;oxIs34

Both unc-13 alleles were highly isoflurane resistant (fig. 4B,C). The locomotion of the null unc-13 allele s69 was not significantly decreased by isoflurane at concentrations up to 4 vol%, a concentration that maximally reduced wild type locomotion. The partial loss-of-function e376 allele was less resistant than s69 but still highly resistant compared to the wild type strain or to the tom-1(ok285);unc-64(js115);oxIs34 genetic background control strain (fig. 4B,C). The unc-2 null mutant was fully sensitive to isoflurane with an isoflurane EC50 not significantly different from wild type (fig. 4B,C). These results shown that UNC-13 is required for isoflurane sensitivity and that the UNC-2 calcium channel is not.

Thus, UNC-13 is required for normal VA sensitivity, but is it the target of the truncated syntaxin as originally proposed? To examine this hypothesis, we tested the ability of overexpressed wild type UNC-13 (produced by mdIs3) to suppress the VA resistance of the truncated syntaxin (fig. 5), the presumption being that UNC-13 when in excess of truncated syntaxin should restore VA sensitivity. Overexpression of full-length UNC-13 did fully suppress the isoflurane resistance of both pTXmd130 and pTX1−107 (fig. 5A,B). However, full-length UNC-13 overexpression (mdIs3) did not significantly change isoflurane sensitivity in a wild type background (fig. 5B). These results are most directly explained if truncated syntaxin physically interacts with UNC-13 to block VA sensitivity and when UNC-13 is expressed in excess of truncated syntaxin, it becomes available for inhibition by VAs. Alternatively, UNC-13 overexpression might prevent interaction of the truncated syntaxin with some other unknown protein that is essential for VA sensitivity.

Fig. 5.

UNC-13 domains required for rescue of isoflurane sensitivity. (A) unc-13 constructs used to transform unc-13(s69) and the resultant protein products. mdIs3 is an integrated array of a genomic fragment encoding the entire unc-13 L + R coding sequence 15 the predicted locations of the Rab3a-interacting molecule (RIM) 16, calmodulin (CAM) 17, and syntaxin (Stx) 9 binding sites are indicated. nuIs46 is an integrated array encoding the M + R shortened form of UNC-13 – UNC-13S – that partially rescues locomotion and transmitter release 18. oxIs78 is an integrated array otherwise identical to nuIs46 except with a 51-nucleotide insertion at the 5’ end of the unc-13S coding sequence that encodes the N-terminal myristoylation sequence of the C. elegans Goα protein 19. (B) Suppression of isoflurane antagonism of truncated syntaxin by overexpression of UNC-13. Isoflurane EC50s measured by the body bend assay. mdIs3[unc-13(+)] is an integrant of the mdEx43 array 15 that overexpresses wild type UNC-13. * - p < 0.01 vs N2; † - p < 0.01 vs corresponding truncated syntaxin strain alone. (C) A null mutant of unc-10 RIM is not isoflurane resistant. The full genotype is unc-64(js115null); unc-10(md1117null); oxIs34[unc-64(L166A/E167A);Pmyo-2::GFP] 20. The isoflurane sensitivity of unc-64(js115 null);oxIs34 is shown for comparison. EC50s (vol%): N2 – 0.82 ± 0.09, js115;md1117;oxIs34 – 0.25 ± 0.03, js115;oxIs34 – 0.85 ± 0.16 (D) UNC-13S restores isoflurane sensitivity to unc-13(s69). EC50s: N2 = 0.72 ± 0.13, s69;nuIs46 = 0.77 ± 0.15 (E) animals expressing myr-UNC-13S are isoflurane resistant. EC50s: s69;nuIs46 = 0.77 ± 0.15, s69;oxIs78 = 3.40 ± 0.32. (F) Summary of isoflurane EC50's ± SE of the fit of the curves in D, E, and the body bend data for unc-13(s69);mdIs3. * - p < 0.01 vs N2. (G) myr-UNC-13s has wild-type sensitivity to aldicarb. The fraction of animals moving after various incubation times on agar plates containing 0.35 mM aldicarb. Each point represents the mean ± sem of triplicate measurements of at least 30 animals/measurement.

If UNC-13 is a VA target in C. elegans, how might binding of VAs disrupt UNC-13 function? mUNC-13 (mammalian UNC-13) has been shown to bind to Rab3a-interacting molecule (RIM) 39, calmodulin 40, and syntaxin 27 (fig. 5A), and these interactions promote synaptic transmission 34,35,40,41. Loss of function mutants of mouse RIM or the C. elegans homolog UNC-10 drastically reduces neurotransmitter release, and mammalian RIM has been implicated in cerebellar long term potentiation 42-45. In mice, calmodulin binding to mUNC-13 has been implicated in activity-dependent synaptic facilitation 40. Whether this function of calmodulin is conserved in C. elegans is unknown. In terms of VA action in C. elegans, a reasonable hypothesis is that VAs disrupt RIM or calmodulin binding to UNC-13 or directly alter RIM/calmodulin function in an UNC-13-dependent fashion. As for unc-13, unc-10 null mutants move slowly, and as for unc-13 mutants, this sluggishness is suppressed by open syntaxin 45, allowing testing of their anesthetic sensitivity. Both the unc-10(md1117 null);open syntaxin double mutant and the open syntaxin mutant alone were fully sensitive to isoflurane (fig. 5C). These results demonstrate that UNC-10 RIM is not required for isoflurane action and that isoflurane does not act by inhibiting the interaction of UNC-10 with UNC-13. Additionally, the normal sensitivity of open syntaxin-bearing animals argues against a mechanism where VAs inhibit UNC-13's promotion of the open form of syntaxin 18. Calmodulin null mutants are lethal in C. elegans. To test calmodulin's role, we measured the isoflurane sensitivity of animals transformed with a shortened form of UNC-13, UNC-13S (Fig. 5A), that lacks the calmodulin- and RIM-binding domains and partially rescues locomotion and transmitter release 20,23. Animals expressing UNC-13S were normally sensitive to isoflurane (fig. 5D,F), demonstrating that neither the UNC-10- nor calmodulin-binding domains are necessary for VA sensitivity.

Based on four previous observations, we considered the hypothesis that VAs might antagonize diacyl glycerol (DAG) binding to and/or activation of UNC-13. First, DAG enhances the transmitter release promoting activity of UNC-13 in C. elegans and in higher organisms 20,23,32. Second, VAs and anesthetic alcohols have been shown to antagonize DAG-binding to and activation of mammalian Protein kinase C (PKC), which contains a C1 domain homologous to that binding DAG in UNC-13 46,47. Third, anesthetic alcohols have been shown to bind to the C1 domain near the DAG binding pocket 46. Finally, we have previously shown that phorbol ester, a C1 domain agonist, antagonizes VAs in C. elegans 9.

To test whether VAs might act to block DAG activation of UNC-13, we made use of the ability of myristoylated UNC-13S (myr-UNC-13S) to promote transmitter release in C. elegans in a DAG-independent manner 20,23. If VAs act on UNC-13 to disrupt DAG binding or activation, myr-UNC-13S by targeting itself to the membrane in a DAG-independent manner should bypass the effect of VAs on UNC-13 and should therefore be VA resistant. Indeed, animals expressing myr-UNC-13S were highly isoflurane resistant compared to those expressing UNC-13S or full-length UNC-13 - unc-13(s69 lf);mdIs3 (fig. 5E,F). We considered the possibility that myr-UNC-13S is VA resistant because it has increased levels of neurotransmitter release compared to wild type. To test this hypothesis, we compared the aldicarb sensitivity of wild type, unc-13S, and myr-unc-13S strains (fig. 5G). myr-unc-13S animals had wild type aldicarb sensitivity whereas unc-13S animals were aldicarb resistant. Thus, a general increase in neurotransmitter release does not explain the resistance of myr-unc-13S. Rather, the most direct explanation of these results is that myristoylation of UNC-13S confers isoflurane resistance by bypassing isoflurane antagonism of DAG-mediated membrane targeting of UNC-13.

To test directly whether isoflurane acts on UNC-13 to antagonize DAG-mediated membrane targeting, we observed the effect of isoflurane on localization of an UNC-13S::GFP fusion protein. This fusion protein has previously been shown to concentrate at synapses in a DAG-dependent manner, where it is visible as distinct puncta that co-localize with other presynaptic proteins in C. elegans dorsal and ventral nerve cords 20,23,38. Thus, the density of puncta along the nerve cord is an indicator of the relative amount of presynaptic membrane-localized UNC-13. Isoflurane significantly reduced both basal and phorbol-ester stimulated UNC-13S::GFP puncta in the dorsal nerve cord (Fig. 6, Table 2). Thus, we conclude that isoflurane decreases DAG-mediated synaptic localization of UNC-13. Alternatively, isoflurane could decrease overall levels of UNC-13; our data do not exclude this possibility.

Fig. 6.

Isoflurane reduces synaptic UNC-13::GFP puncta. Representative images of segments of dorsal nerve cord from unc-13(s69);nuIs46[UNC-13S::GFP;ccGFP] L4 larval animals treated with (A) Air, no PMA (phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate), (B) isoflurane (2 vol%), no PMA, (C) Air, 1 μg/ml PMA, (D) isoflurane (2 vol%), 1 μg/ml PMA. Note synaptic puncta (example denoted by arrowhead) decreased in B and D relative to their respective air controls. scale bar = 20 μm.

Table 2.

Effect of isoflurane on UNC-13 localization

| Condition | Puncta/100 μm | Animals | p-value vs Air | p-value vs No PMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air, No PMA | 11.2 ± 0.5 | 43 | — | — |

| Iso, No PMA | 8.2 ± 0.5 | 54 | 0.00006 | — |

| Air, PMA | 14.2 ± 0.5 | 51 | — | 0.00004 |

| Iso, PMA | 10.8 ± 0.6 | 42 | 0.00002 | 0.0006 |

[Iso]=2 vol%, PMA = phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate[PMA] = 1 μg/ml; values are mean ± sem; Scorer blinded to condition; p-value by two-tailed test

Discussion

We have shown that a relatively short N-terminal syntaxin-1A fragment can fully antagonize the behavioral effects of clinical concentrations of the volatile anesthetic isoflurane in C. elegans. The antagonism is direct in that the truncated syntaxin had no apparent effect on locomotion or synaptic concentrations of acetylcholine as measured by aldicarb sensitivity. The specificity of the truncated syntaxin coupled with its dominant genetic behaviour argues that the truncated syntaxin is acting essentially as a pharmacological antagonist against the VA target. Working under this assumption, the question becomes to what is the truncated syntaxin binding to antagonize VAs? The number of proteins which have been shown to bind to this N-terminal segment of syntaxin is few. Testing of mutants of two such candidates showed that UNC-13 but not the non-L type Ca++ channel was essential for sensitivity to VAs in the clinically relevant concentration range. Consistent with UNC-13 as the target of the antagonistic activity of truncated syntaxin, overexpression of UNC-13 suppressed the VA resistance phenotype of truncated syntaxin. Finally, isoflurane appears to decrease synaptic localization of UNC-13, and animals with membrane targeted UNC-13 are isoflurane resistant. Thus, UNC-13 is required for VA sensitivity in C. elegans, is likely the protein to which the truncated syntaxin is binding, and its localization is inhibited by and important for isoflurane action. A schematic of our working model based on these data is shown in figure 7.

Fig. 7.

Working model of presynaptic mechanism of isoflurane in C. elegans. Diacyl glycerol – DAG (green circle) is known to bind to UNC-13 (blue rounded rectangle) and thereby increase the local concentration of UNC-13 at the presynaptic membrane 18,19,21,22. Membrane translocation of UNC-13 is thought to promote interaction with syntaxin and thereby promote fusion of synaptic vesicles and transmitter release. Isoflurane (orange triangle) antagonizes DAG-mediated membrane translocation of UNC-13, and myristoylated UNC-13, which promotes transmitter release in a DAG-independent manner 18,19, confers isoflurane resistance (Figs. 5, 6 & Table 2). Animals without UNC-13 are highly isoflurane resistant (Fig. 4). These three results can be explained by isoflurane binding to UNC-13 and antagonizing DAG binding or the effect of binding (indicated by crossed out arrow). Truncated syntaxin (red rectangle), which lacks its transmembrane domain, blocks isoflurane sensitivity (Fig. 1), presumably by competing with isoflurane for binding to UNC-13 (indicated by crossed out arrow) since UNC-13 overexpression can suppress the isoflurane resistance of truncated syntaxin.

The questions now posed by our findings are several including: why has UNC-13 not been previously implicated in anesthetic action, is UNC-13 a direct anesthetic target, and what might be the role, if any, of UNC-13 orthologs in vertebrate anesthesia? Multiple reasonable explanations can be posited as to why no direct evidence till now has implicated UNC-13/mUNC-13 in anesthetic action. First, the primary methodology for most anesthetic mechanism studies is electrophysiology. While multiple electrophysiological studies have shown that volatile anesthetics do inhibit neurotransmitter release in various preparations 2, no specific mUNC-13 inhibitors are available that might have implicated mUNC-13. Moreover, inhibition of UNC-13/mUNC-13 does not produce a distinct electrophysiological phenotype that would clearly implicate these proteins. Likewise, binding studies that might have identified UNC-13/mUNC-13 as a VA target are severely limited by the low affinity and high membrane partitioning of VAs. Indeed, no synaptic protein has been specifically identified in binding studies on crude membrane preparations despite the presence of relatively abundant proteins such as GABAA receptors, which are very likely to be direct VA targets 1.

UNC-13 has several properties suggesting that it is a direct and relevant anesthetic target in C. elegans. First, animals lacking UNC-13 are VA resistant. Resistance is neither a necessary nor sufficient feature of an anesthetic target because of the possibility of multiple targets, genetic redundancy, and indirect effects. Nevertheless, the high level resistance of the unc-13 mutants is consistent with the VA target being UNC-13. Second, a mutation in UNC-13 (a myristoylation sequence) that otherwise does not disrupt UNC-13 function confers isoflurane resistance, and UNC-13 synaptic localization appears to be decreased by isoflurane. These results are difficult to explain by an indirect model. One reasonable indirect model to consider is that VAs act to prevent production of DAG and thereby inhibit the function of UNC-13. Such an anesthetic mechanism would depend on UNC-13, be circumvented by myr-UNC-13S, and decrease UNC-13 synaptic localization. However, we have previously shown that a probable null mutation in egl-8, which encodes the only known phospholipase Cβ acting upstream of UNC-13 to stimulate transmitter release, is not as VA resistant as the unc-13 or truncated syntaxin mutants 9. Moreover, this mechanism does not explain the resistance produced by the truncated syntaxin. On the other hand, a model where the truncated cytoplasmic syntaxin competes with anesthetics for binding to UNC-13 is plausible and consistent with the existing data.

Is there any evidence that VAs bind to UNC-13 or its vertebrate homologs? While no binding experiments have been reported with UNC-13/mUNC-13, volatile anesthetics and anesthetic alcohols have been shown to inhibit PKC 48, which has a C1 domain structurally similar to the C1 domain in UNC-13. Subsequent studies found that anesthetic alcohols do bind to the C1 domain of bovine PKCα and compete for diacyl glycerol binding 47. More recently, a photoaffinity anesthetic alcohol labelled tyrosine 236 of the C1 domain of PKCδ 46. The X-ray crystal structure of the C1B domain of PKCδ places tyrosine 236 approximately 10Å from the diacyl glycerol binding pocket 46 and provides a structural explanation for how anesthetics might inhibit diacyl glycerol binding to the C1 domain. The structure of mUNC13-1 C1 domain has been compared to that of PKCδ by solution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and found to be generally similar with conservation of the location of the homologous tyrosine 49. However, a tryptophan residue was found to overlie the DAG-binding pocket in mUNC13-1 but not in PKCδ. This structural difference was proposed to account for the lower affinity of mUNC13-1 for phorbol esters. Thus, while anesthetic binding to the C1 domain of PKCα and PKCδ suggests that anesthetics are likely to also bind to the C1 domain of UNC-13/mUNC-13, the structural differences between the proteins offer the possibility that the affinities and/or effect of binding may differ between the homologous domains.

What might be the role of vertebrate UNC-13 homologs in general anesthesia? This question can be divided into two parts. First, in general, how might inhibition of neurotransmitter release contribute to general anesthesia? Second, specifically, what role might inhibition of vertebrate UNC-13 homologs play in the overall presynaptic anesthetic mechanism in vertebrates? Clearly, inhibition of excitatory neurotransmitter release could lead to an overall depression in nervous system function and contribute to a general anesthetic state. On the other hand, reducing inhibitory neurotransmitter release would counteract this effect and might actually increase arousal. In particular for volatile anesthetics, a block of inhibitory release would likely reduce anesthetic efficacy because of the well-established postsynaptic VA action of potentiation of ligand gating of inhibitory GABAA and glycine receptors. However, as outlined in the introduction, at clinical concentrations volatile general anesthetics including isoflurane selectively inhibit neurotransmitter release, reducing glutamate release significantly more than GABA release. Thus, VAs could reduce excitatory neurotransmission by its presynaptic mechanism while at the same time, because of minimal effect on inhibitory neurotransmitter release, potentiate postsynaptic inhibitory GABA and glycine currents and thereby synergistically depress central nervous system activity. Besides this potential for synergy, in particular brain regions such as the hippocampus, presynaptic excitatory inhibition appears to be a predominant effect 5,6,50. Thus, presynaptic effects could be particular critical for the amnestic effects of VAs.

As to what is the role of UNC-13 orthologs in presynaptic VA action in vertebrates, one must consider that VAs almost certainly act on other presynaptic targets besides UNC-13 homologs. Sodium channels have been strongly implicated as essential for a significant portion of VA presynaptic inhibition3,4,51. Thus, unlike in C. elegans, which lacks sodium channels, UNC-13 orthologs are unlikely to be the sole presynaptic VA target in mammals. However, the mammalian UNC-13 homologs, mUNC13-1, 2, and 3 have interesting distinct functional roles that could account for the synapse selective effects of VAs. Specifically, mUNC-13 isoforms are differentially expressed in GABA versus glutamate terminals. Release from the majority of glutamatergic terminals in mouse hippocampus requires the mUNC13-1 isoform whereas mUNC13-1 and mUNC13-2 function redundantly in GABAergic release at least in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus 52. In rat brain, mUNC13-1 is expressed throughout the central nervous system whereas mUNC-13-2 expression is restricted to the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. mUNC-13-3 appears to be expressed exclusively in the cerebellum 53. Intriguingly, mUNC13-1- and mUNC13-2-mediated release differ in their potentiation by DAG; mUNC13-1 is less efficaciously potentiated 52. These previous observations coupled with the results reported here suggest that mUNC13-1, the closest homolog to C. elegans UNC-13, may be more sensitive to VAs because its weak DAG potentiation is more efficaciously blocked by VAs compared to that of mUNC13-2. The availability of mouse knockout strains for each of the mUNC13 isoforms will allow testing of this hypothesis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Owais Saifee, M.D., Ph.D. and Mike Nonet, Ph.D., Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA for their seminal contributions to this work, Janet Richmond, Ph.D., Department of Biological Sciences, University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA for sharing of unpublished results and strains, and Kim Schuske, Ph.D. and Erik Jorgensen, Ph.D., Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA for the unpublished oxIs78 array. Supported by RO1 GM59781 from National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Bethesda, MD, USA and institutional funds.

References

- 1.Franks NP. Molecular targets underlying general anaesthesia. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S72–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perouansky M, Hemmings HC., Jr. In: Presynaptic actions of general anesthetics, Neural Mechanisms of Anesthesia. Antognini JF, Carstens EE, Raines DE, editors. Humana Press; Totowa: 2003. pp. 345–369. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westphalen RI, Hemmings HC., Jr. Volatile Anesthetic Effects on Glutamate versus GABA Release from Isolated Rat Cortical Nerve Terminals: Basal Release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:208–215. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.090647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westphalen RI, Hemmings HC., Jr. Volatile anesthetic effects on glutamate versus GABA release from isolated rat cortical nerve terminals: 4-aminopyridine-evoked release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:216–23. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacIver MB, Mikulec AA, Amagasu SM, Monroe FA. Volatile anesthetics depress glutamate transmission via presynaptic actions. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:823–34. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199610000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishikawa K, MacIver MB. Membrane and synaptic actions of halothane on rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons and inhibitory interneurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5915–23. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-05915.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikulec AA, Pittson S, Amagasu SM, Monroe FA, MacIver MB. Halothane depresses action potential conduction in hippocampal axons. Brain Res. 1998;796:231–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00348-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Swinderen B, Saifee O, Shebester L, Roberson R, Nonet ML, Crowder CM. A neomorphic syntaxin mutation blocks volatile-anesthetic action in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2479–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawasli AH, Saifee O, Liu C, Nonet ML, Crowder CM. Resistance to volatile anesthetics by mutations enhancing excitatory neurotransmitter release in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2004;168:831–43. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.030502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Swinderen B, Metz LB, Shebester LD, Crowder CM. A Caenorhabditis elegans Pheromone Antagonizes Volatile Anesthetic Action Through a Go-Coupled Pathway. Genetics. 2002;161:109–19. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Swinderen B, Metz LB, Shebester LD, Mendel JE, Sternberg PW, Crowder CM. Goalpha regulates volatile anesthetic action in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2001;158:643–55. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.2.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rand JB, Nonet ML. In: Synaptic transmission, C. elegans II. Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor: 1997. pp. 611–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saifee O, Wei L, Nonet ML. The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-64 locus encodes a syntaxin that interacts genetically with synaptobrevin. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1235–52. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagele P, Mendel JB, Placzek WJ, Scott BA, D'Avignon DA, Crowder CM. Volatile anesthetics bind rat synaptic snare proteins. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:768–78. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200510000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs--engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gracheva EO, Burdina AO, Holgado AM, Berthelot-Grosjean M, Ackley BD, Hadwiger G, Nonet ML, Weimer RM, Richmond JE. Tomosyn inhibits synaptic vesicle priming in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLOS Biology. 2006;4:1426–37. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richmond JE, Weimer RM, Jorgensen EM. An open form of syntaxin bypasses the requirement for UNC-13 in vesicle priming. Nature. 2001;412:338–41. doi: 10.1038/35085583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohn RE, Duerr JS, McManus JR, Duke A, Rakow TL, Maruyama H, Moulder G, Maruyama IN, Barstead RJ, Rand JB. Expression of multiple UNC-13 proteins in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3441–52. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lackner MR, Nurrish SJ, Kaplan JM. Facilitation of synaptic transmission by EGL-30 Gqalpha and EGL-8 PLCbeta: DAG binding to UNC-13 is required to stimulate acetylcholine release. Neuron. 1999;24:335–46. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80848-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoppe PE, Waterston RH. A region of the myosin rod important for interaction with paramyosin in Caenorhabditis elegans striated muscle. Genetics. 2000;156:631–43. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.2.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crowder CM, Westover EJ, Kumar AS, Ostlund RE, Jr., Covey DF. Enantiospecificity of cholesterol function in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44369–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100535200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nurrish S, Segalat L, Kaplan JM. Serotonin inhibition of synaptic transmission: Galpha(0) decreases the abundance of UNC-13 at release sites. Neuron. 1999;24:231–42. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowder CM, Shebester LD, Schedl T. Behavioral effects of volatile anesthetics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:901–12. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199610000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waud DR. On biological assays involving quantal responses. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 1972;183:577–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang ZW, Saifee O, Nonet ML, Salkoff L. SLO-1 potassium channels control quantal content of neurotransmitter release at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 2001;32:867–81. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00522-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Betz A, Okamoto M, Benseler F, Brose N. Direct interaction of the rat unc-13 homologue Munc-13-1 with the N-terminus of syntaxin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:2520–2526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarvis SE, Barr W, Feng ZP, Hamid J, Zamponi GW. Molecular determinants of syntaxin 1 modulation of N-type calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44399–407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathews EA, Garcia E, Santi CM, Mullen GP, Thacker C, Moerman DG, Snutch TP. Critical residues of the Caenorhabditis elegans unc-2 voltage-gated calcium channel that affect behavioral and physiological properties. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6537–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06537.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brose N, Rosenmund C, Rettig J. Regulation of transmitter release by Unc-13 and its homologues. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:303–11. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richmond JE, Davis WS, Jorgensen EM. UNC-13 is required for synaptic vesicle fusion in C. elegans. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:959–964. doi: 10.1038/14755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Betz A, Ashery U, Rickmann M, Augustin I, Neher E, Sudhof TC, Rettig J, Brose N. Munc13-1 is a presynaptic phorbol ester receptor that enhances neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;21:123–36. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maruyama IN, Brenner S. A phorbol ester/diacylglycerol-binding protein encoded by the unc-13 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:5729–5733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens DR, Wu ZX, Matti U, Junge HJ, Schirra C, Becherer U, Wojcik SM, Brose N, Rettig J. Identification of the minimal protein domain required for priming activity of Munc13-1. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2243–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madison JM, Nurrish S, Kaplan JM. UNC-13 Interaction with Syntaxin Is Required for Synaptic Transmission. Current Biology. 2005;15:2236–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schafer WR, Kenyon CJ. A calcium-channel homologue required for adaptation to dopamine and serotonin in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1995;375:73–8. doi: 10.1038/375073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dybbs M, Ngai J, Kaplan JM. Using Microarrays to Facilitate Positional Cloning: Identification of Tomosyn as an Inhibitor of Neurosecretion. PLoS Genetics. 2005;1:6–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McEwen JM, Madison JM, Dybbs M, Kaplan JM. Antagonistic Regulation of Synaptic Vesicle Priming by Tomosyn and UNC-13. Neuron. 2006;51:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Betz A, Thakur P, Junge HJ, Ashery U, Rhee JS, Scheuss V, Rosenmund C, Rettig J, Brose N. Functional interaction of the active zone proteins Munc13-1 and RIM1 in synaptic vesicle priming. Neuron. 2001;30:183–96. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Junge HJ, Rhee JS, Jahn O, Varoqueaux F, Spiess J, Waxham MN, Rosenmund C, Brose N. Calmodulin and Munc13 form a Ca2+ sensor/effector complex that controls short-term synaptic plasticity. Cell. 2004;118:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dulubova I, Lou X, Lu J, Huryeva I, Alam A, Schneggenburger R, Sudhof TC, Rizo J. A Munc13/RIM/Rab3 tripartite complex: from priming to plasticity? EMBO J. 2005;24:2839–2850. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schoch S, Castillo PE, Jo T, Mukherjee K, Geppert M, Wang Y, Schmitz F, Malenka RC, Sudhof TC. RIM1alpha forms a protein scaffold for regulating neurotransmitter release at the active zone. Nature. 2002;415:321–6. doi: 10.1038/415321a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castillo PE, Schoch S, Schmitz F, Sudhof TC, Malenka RC. RIM1alpha is required for presynaptic long-term potentiation. Nature. 2002;415:327–30. doi: 10.1038/415327a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lonart G, Schoch S, Kaeser PS, Larkin CJ, Sudhof TC, Linden DJ. Phosphorylation of RIM1alpha by PKA triggers presynaptic long-term potentiation at cerebellar parallel fiber synapses. Cell. 2003;115:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00727-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koushika SP, Richmond JE, Hadwiger G, Weimer RM, Jorgensen EM, Nonet ML. A post-docking role for active zone protein Rim. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:997–1005. doi: 10.1038/nn732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Das J, Addona GH, Sandberg WS, Husain SS, Stehle T, Miller KW. Identification of a General Anesthetic Binding Site in the Diacylglycerol-binding Domain of Protein Kinase C{delta}. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:37964–37972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slater SJ, Kelly MB, Larkin JD, Ho C, Mazurek A, Taddeo FJ, Yeager MD, Stubbs CD. Interaction of alcohols and anesthetics with protein kinase Calpha. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6167–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Slater SJ, Cox KJ, Lombardi JV, Ho C, Kelly MB, Rubin E, Stubbs CD. Inhibition of protein kinase C by alcohols and anaesthetics. Nature. 1993;364:82–4. doi: 10.1038/364082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen N, Guryev O, Rizo J. Intramolecular occlusion of the diacylglycerol-binding site in the c(1) domain of munc13-1(,). Biochemistry. 2005;44:1089–96. doi: 10.1021/bi0476127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winegar BD, MacIver MB. Isoflurane depresses hippocampal CA1 glutamate nerve terminals without inhibiting fiber volleys. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu X-S, Evers AS, Crowder CM, Wu L-G. Isoflurane inhibits transmitter release and the presynaptic action potential. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:663–670. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200403000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenmund C, Sigler A, Augustin I, Reim K, Brose N, Rhee JS. Differential control of vesicle priming and short-term plasticity by Munc13 isoforms. Neuron. 2002;33:411–24. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Augustin I, Betz A, Herrmann C, Jo T, Brose N. Differential expression of two novel Munc13 proteins in rat brain. Biochem J. 1999;337(Pt 3):363–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]