SUMMARY

Bacterial and eukaryotic plant pathogens deliver effector proteins into plant cells to promote pathogenesis. Bacterial pathogens containing type III protein secretion systems are known to inject many of these effectors into plant cells. More recently, oomycete pathogens have been shown to possess a large family of effectors containing the RXLR motif, and many effectors are also being discovered in fungal pathogens. Although effector activities are largely unknown, at least a subset suppress plant immunity. A plethora of new plant pathogen genomes that will soon be available thanks to next‐generation sequencing technologies will allow the identification of many more effectors. This article summarizes the key approaches used to identify plant pathogen effectors, many of which will continue to be useful for future effector discovery. Thus, it can be viewed as a ‘roadmap’ for effector and effector target identification. Because effectors can be used as tools to elucidate components of innate immunity, advances in our understanding of effectors and their targets should lead to improvements in agriculture.

INTRODUCTION

Plant pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, oomycetes and nematodes, secrete proteins, referred to as effectors, into plant cells to favour parasitism (Block et al., 2008; Davis et al., 2008; Ellis et al., 2009; Tyler, 2009; Zhou and Chai, 2008). Although the vast majority of effector activities and host targets remain unknown, at least a subset suppress innate immune responses (Abramovitch et al., 2006; Boller and He, 2009; Espinosa and Alfano, 2004; Hein et al., 2009). This suppression activity means that effectors can be used as tools to identify important components of innate immunity and can potentially lead to innovative strategies for crop improvement. For this article, the term ‘effector’ will be limited to proteins secreted by pathogens and translocated into plant cells where they exert specific functions, usually in collusion with other effectors exported by the same secretion/export system. Many effectors only subtly modify the host cell to sway the pathogen–plant interaction to the pathogen's advantage. They are often functionally redundant with other co‐secreted effectors. This narrow definition is similar to that recently used in a review on bacterial animal pathogen effectors (Galan, 2009) and is distinct from a more inclusive effector definition used in a recent review on plant pathogen effectors (Hogenhout et al., 2009). The inclusive effector definition includes all pathogen proteins and small molecules that alter host cell structure and function. Although both definitions are appropriate, the narrower effector definition allows for a more focused discussion on the future research on plant pathogen effectors in this article.

A myriad of important discoveries regarding plant pathogen effectors have been made in the 25 years since the first plant pathogen effector was discovered by Staskawicz et al. (1984). Many of these discoveries are associated with bacterial pathogen type III protein secretion systems (T3SSs): for example, the seminal discovery of hrp genes (Lindgren et al., 1986), which were identified because they were required for both the defence‐related hypersensitive response (HR) and pathogenicity, and were later shown to encode a T3SS present in many eukaryotic‐associated bacteria (Van Gijsegem et al., 1993). Another critical advance was the discovery that type III effectors were injected into plant cells, because it revealed that their plant targets were intracellular (Alfano and Collmer, 1996). More recently, the RXLR (arginine, any amino acid, leucine and arginine) motif in the N‐terminus of some oomycete effectors was discovered, allowing for many more oomycete effectors to be identified (Birch et al., 2008; Tyler, 2009).

What new discoveries will be made in the next 25 years and what technologies and/or approaches will allow them to be realized? One thing is for sure—next‐generation sequencing technologies will provide the genome sequences of multiple strains of many plant pathogen species, greatly accelerating effector discovery. For newly sequenced pathogens, the initial focus will be to identify effector inventories and the translocation strategies that allow effector delivery into plant cells. For plant pathogens for which this is already established, the next decade promises to reveal plant targets of these effectors and the strategies that pathogens use to attack plants. We are therefore entering an exciting period for molecular plant pathology as we may learn the fundamental reasons why some organisms are pathogens, as well as important factors controlling host specificity and nonhost resistance.

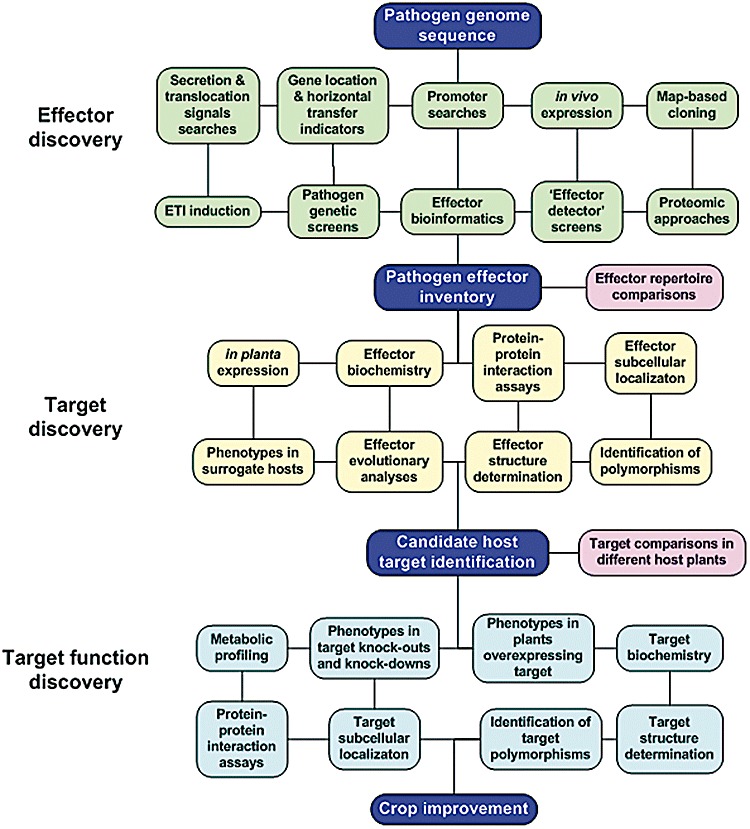

This article summarizes the techniques and approaches likely to be used to identify plant pathogen effectors and their targets. New technologies or discoveries will of course also have an impact on effector research. However, effector and effector target discovery and confirmation will require multiple approaches. Figure 1 shows a flowchart summarizing these approaches and is referred to throughout this article. It represents a ‘roadmap’ for future research on plant pathogen effectors. The best starting point on this roadmap is at the genome sequence of a pathogen, which allows the most approaches to be employed. However, several approaches can be used without the benefit of sequence data. Important stops along the way are the identification of effector targets and how effector–target interactions promote the pathogenesis of plants. The final destination of this road trip is to exploit the information gained to engineer plants with increased pathogen resistance.

Figure 1.

‘Roadmap’ for discovery of plant pathogen effectors and their targets. The flowchart shows the approaches used for effector discovery (green boxes), target discovery (yellow boxes) and target function discovery (light blue boxes). Starting, intermediate and stopping points in the flowchart are depicted as dark blue boxes. Pink boxes depict comparisons that can be carried out after effector repertoires and targets have been isolated that may give insights to virulence and nonhost resistance. The lines connecting each box indicate that it may be used in combination with other approaches in the network, not necessarily just the adjacent boxes. Useful tools for studying eukaryotic effectors are the ‘effector detector’ screens that fuse candidate effectors to type III secretion signals, such that they are injected into plant cells by a bacterial strain containing a type III protein secretion system (Rentel et al., 2008; Sohn et al., 2007). Effectors can be expressed transiently or transgenically in planta to determine whether they produce phenotypes, such as enhanced susceptibility to pathogens, or whether they suppress plant innate immunity outputs. T‐DNA knock‐out and RNA interference knock‐down plants or plants over‐expressing effector targets can be used to determine target function and to confirm that they are effector targets. See text for additional details.

EFFECTOR DISCOVERY

The inundation of plant pathogen genome sequences is expected to result in the identification of a large number of plant pathogen effectors over the next decade. Considering that bacterial plant pathogen strains can have greater than 30 effectors each and oomycete strains several hundred (Lindeberg et al., 2006; Tyler et al., 2006), thousands of novel effectors may exist in bacteria, fungi, oomycetes and nematodes. The majority of bacterial effectors appear to suppress innate immunity (Block et al., 2008; Boller and He, 2009; Guo et al., 2009; Zhou and Chai, 2008). A clear exception is the large family of transcription activator‐like (TAL) effectors found mostly in Xanthomonas pathogens. These effectors induce the transcription of susceptibility genes in the host plant (Kay and Bonas, 2009). Plant innate immunity can also be suppressed by several eukaryotic effectors (Bos et al., 2006; Dou et al., 2008a; Houterman et al., 2008; Sohn et al., 2007), but it is too early to know whether this is a common effector activity. The techniques currently employed to identify effectors are summarized in the top portion of Fig. 1. Additional bioinformatics approaches are greatly needed to more efficiently identify effectors, their activities and targets. Select approaches are discussed in more detail below.

The tried and true approach

A classic strategy to identify effector genes is to determine whether they induce effector‐triggered immunity (ETI) when expressed in a virulent pathogen strain (Chisholm et al., 2006). Indeed, it is this approach, pioneered by Staskawicz and colleagues, that was used to identify the first plant pathogen effector that this issue is commemorating (Staskawicz et al., 1984). This tried and true approach is particularly successful because the main ETI response tracked, production of an HR, is easily and rapidly evaluated in the laboratory. A protein capable of inducing ETI was classically referred to as an avirulence (Avr) protein. It has become clear that many Avr proteins are effector proteins that plants have evolved the ability to recognize with resistance (R) proteins (Jones and Dangl, 2006). Map‐based cloning based on ETI induction is an effective strategy to isolate avr genes from eukaryotic pathogens (Ellis et al., 2009; O'Connell & Panstruga, 2006; Panstruga and Dodds, 2009). Another useful variation is to screen a collection of candidate effectors for their ability to induce ETI, as performed by Catanzariti et al. (2006). These authors identified a set of Melampsora lini genes induced in the haustoria (specialized pathogen structures that invaginate into plant cells) and found that several elicited the HR and co‐segregated with independent avr loci. This classic approach will probably continue to be included in various effector hunting strategies.

Location, location, location

Comparative genomics can allow the identification of effector genes based on their location. For example, effector genes in bacterial pathogens are often clustered in pathogenicity islands (PAIs) (Kim and Alfano, 2002). These PAIs can be on plasmids or integrated into the chromosome. One common site for PAI integration is within or adjacent to tRNA genes. In addition, PAIs are often associated with mobile DNA elements (Hacker and Kaper, 2000). Thus, new effector genes can be identified by scanning genomes for regions of atypical GC content, codon usage and other relevant nucleotide statistics (Juhas et al., 2009). Although this approach is less well established in eukaryotic pathogens, similar approaches are becoming important. For example, the AvrLm1 effector gene from the fungal pathogen Leptosphaeria maculans is located in a gene‐poor heterochromatin‐like region of the genome (Fudal et al., 2007; Gout et al., 2006; Kamoun, 2007), suggesting that effector genes may be flanked by long intergenic regions. In addition, there are also examples in which fungal and oomycete effector genes are clustered (Kamper et al., 2006; Win et al., 2007). Therefore, genomes could be searched for both of these characteristics to identify or at least enrich for novel effectors.

It has to get out before it can get in

Type III effectors from the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae have secretion signals that share common biochemical characteristics in their N‐terminal 50 amino acids (Collmer et al., 2002; Guttman et al., 2002; Petnicki‐Ocwieja et al., 2002). These characteristics allowed a bioinformatics search of the P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genome, yielding candidate effectors that were directly tested for their ability to be secreted and/or translocated (Guttman et al., 2002; Petnicki‐Ocwieja et al., 2002). More recently, other sequence‐based bioinformatics tools have been developed to identify type III effector genes across bacterial genera (Arnold et al., 2009; Samudrala et al., 2009).

Researchers identifying effectors in fungal and oomycete pathogens have screened expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and genomes for genes encoding proteins with putative N‐terminal type II secretion signals (Ellis et al., 2009; Panstruga and Dodds, 2009). This has been extremely useful in conjunction with other approaches to enrich for effector genes. For example, Kemen et al. (2005) identified the Rust transferred protein 1 (Uf‐RTP1p) by isolating Uromyces fabae haustorium‐specific cDNAs using differential hybridization, which they then screened for putative type II secretion signals. A similar approach was used to identify a group of effectors from Phytophthora infestans, called crinklers, based on the presence of a putative secretion signal and a leaf‐crinkling and cell death phenotype when they were transiently expressed in plants (Kamoun, 2007; Torto et al., 2003). However, fungal effectors have been identified that do not have N‐terminal type II secretion signals (Ridout et al., 2006), highlighting the need for additional effector search criteria.

A major advance in effector research, as noted above, was the recognition that many oomycete effectors possess an RXLR motif (Birch et al., 2006; Rehmany et al., 2005; Tyler et al., 2006). This allowed the genomes of Phytophthora species and Hyaloperonospora parasitica to be searched for both a putative N‐terminal secretion signal and an RXLR motif, facilitating the identification of oomycete effectors. Importantly, the RXLR motif is related to the ‘Pexel’ motif present in the N‐termini of effectors from the malaria parasite Plasmodium (Hiller et al., 2004; Marti et al., 2004), which implicated the RXLR motif in translocation into plant cells. Oomycete researchers have recently confirmed that the RXLR motif is required for translocation into plant cells (Dou et al., 2008b; Whisson et al., 2007). The identification of additional searchable secretion/translocation signals or motifs will be important in identifying other types of eukaryotic effector.

Looking for known unknowns

There are many examples of the identification of effectors based on their similarity to known proteins or the presence of known domains or motifs. This includes similarities to effectors (usually Avr proteins) from other pathogens, to enzymes or to the presence of eukaryote‐like domains and motifs (Armstrong et al., 2005; Collmer et al., 2002; Fouts et al., 2002; Poueymiro and Genin, 2009). One of the first clues that type III effectors from bacterial plant pathogens were injected into plant cells was the recognition that the Xanthomonas AvrBs3 effector family possesses functional nuclear localization signals (NLSs) (Van den Ackerveken et al., 1996; Yang and Gabriel, 1995). Although members of this effector family were already identified, the recognition of NLS motifs led to the discovery that they were injected into plant cells (Van den Ackerveken et al., 1996) and acted as transcriptional activators (Zhu et al., 1999). In addition, a family of Ralstonia solanacearum type III effectors was identified, in part, because of their plant‐specific leucine‐rich repeat (LRR) motifs (Cunnac et al., 2004). These effectors, named GALAs after conserved amino acids within the LRRs, were later shown to contain putative F‐box domains and, therefore, potentially to interfere with the plant ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (2006, 2007).

Searching for eukaryote‐like motifs in candidate effector genes in prokaryote genomes is obviously easier than searching for them in eukaryotic genomes. However, it is still possible to employ this strategy to search for eukaryotic effectors if combined with other search criteria. For example, Mueller et al. (2008) first searched the Ustilago maydis genome for putative secretion signals and then winnowed down the candidates by searching for domains and motifs needed for proteins to function in the apoplast or inside eukaryotic cells. From the latter, they identified putative effectors possessing NLSs, zinc finger domains or RING domains, which suggested that they act inside plant cells.

Turn on only when needed

It is no wonder that energy‐efficient microbes have evolved ‘green’ strategies to tightly regulate genes that are needed for specific purposes, such as survival and growth in plant tissue. Effector genes have been identified as a result of their in planta induction. Bacterial T3SSs (including effectors) are induced in plants by known regulatory proteins (Tang et al., 2006). One strategy to identify type III effector genes is to identify promoters and/or genes dependent on these regulatory proteins (Buttner et al., 2003; Collmer et al., 2002; Cunnac et al., 2004; Furutani et al., 2009). In P. syringae, the alternate sigma factor HrpL binds to a conserved sequence in type III promoters, called the Hrp box. Searching for Hrp boxes in P. syringae genomes allowed for the identification of many P. syringae effectors (Fouts et al., 2002; Guttman et al., 2002; Zwiesler‐Vollick et al., 2002).

Essentially, the identification of type III effector genes from bacterial genome data has become fairly straightforward. This usually involves searching for type III‐related promoters, N‐terminal secretion signal characteristics and/or determining whether their expression is dependent on a specific regulatory system. However, one lingering complication is that type III‐secreted extracellular accessory proteins are also identified by these criteria, and therefore, if the protein is not similar to known accessory proteins or if it does not have similarity to eukaryote‐like domains, further consideration is needed to determine whether it is an injected effector or an extracellular accessory protein.

Eukaryotic pathogens also appear to induce their effectors during infection (Dodds et al., 2009). Various subtractive hybridization approaches will continue to be attractive for the identification of eukaryotic effectors. With next‐generation sequencing technologies becoming available and more affordable, one approach will probably be the sequencing of cDNA libraries from pathogens grown on plants (or plant‐mimicking conditions) versus a control medium.

TARGET DISCOVERY

The next critical juncture for effector research is target identification. To date, the only plant targets identified have been for bacterial effectors (Block et al., 2008; Boller and He, 2009; Zhou and Chai, 2008). However, several oomycete effectors have been shown to suppress innate immunity, and the enzymatic activities for two fungal effectors are known (Dodds et al., 2009). With the current and rapid identification of effectors from oomycetes and fungi, it is likely that eukaryotic effector targets will soon be found and targets for bacterial effectors should continue to be identified. Several proven strategies for the identification of plant targets are discussed below and are included with other strategies in the middle portion of Fig. 1.

Guilt by association

The most productive approach for the identification of effector targets has been protein–protein interaction assays. The Arabidopsis RIN4 protein, a plant pathogen effector target, was identified on the basis of its interaction with the P. syringae AvrB type III effector in a yeast two‐hybrid (Y2H) system (Mackey et al., 2002). RIN4 was subsequently shown to interact with the effectors AvrRpm1 and AvrRpt2 (Axtell and Staskawicz, 2003; 2003, 2002) and the R proteins RPS2, RPM1 and RPS2 (Axtell and Staskawicz, 2003; 2003, 2002). Y2H approaches have also been successful in showing that the P. syringae AvrPto and AvrPtoB effectors interact with the tomato Pto kinase (Kim et al., 2002; Tang et al., 1996). More recently, co‐immunoprecipitation approaches have shown that these effectors interact with and disable pathogen‐associated molecular pattern (PAMP) receptors (Gimenez‐Ibanez et al., 2009; Gohre et al., 2008; Shan et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2007). Targets identified in this manner require confirmation of the identified interactions using complementary approaches. In this regard, a new in planta spilt luciferase system shows promise (Chen et al., 2008).

In the right place at the right time

Some effectors interact too weakly or transiently with their targets for protein–protein interaction approaches to be useful. The in planta subcellular localization of effectors can provide clues to their function and target identity. Bacterial, oomycete and fungal effectors have been localized to the plant nucleus (Deslandes et al., 2003; Kanneganti et al., 2007; Kay and Bonas, 2009; Kemen et al., 2005), suggesting potential functions such as transcriptional regulation and nucleocytoplasmic trafficking. Many bacterial effectors localize to the plasma membrane (Dowen et al., 2009; Nimchuk et al., 2000; Robert‐Seilaniantz et al., 2006; Shan et al., 2000). The co‐localization of potential targets with their effectors increases the likelihood that they are bona fide targets. The importance of determining an effector's site of action is also illustrated by the P. syringae HopI1 effector, which localizes to chloroplasts (Jelenska et al., 2007). HopI1 suppresses innate immunity, alters chloroplast thylakoid structure and reduces salicylic acid accumulation—all plausible effects considering HopI1's subcellular localization. It is apparent that microscopy and biochemical fractionation approaches will continue to be an important aid for the determination of effector functions and targets.

Change is for the best

There is a fascinating evolutionary struggle between pathogens and plants in which effectors are under selection to evade detection by plant R protein‐based surveillance systems, whilst maintaining their virulence activities, and R proteins adapt to acquire and maintain effector recognition (Ma and Guttman, 2008). Several examples exist which indicate that eukaryotic effectors change to avoid direct recognition by R proteins. For example, Dodds et al. (2006) have shown that selected sites within the AvrL567 effector from M. lini allow it to evade direct recognition by R proteins. The selection pressure is less clear for the bacterial effectors. Bacterial effectors are under selection to avoid ‘guarded’ plant targets or possible direct recognition by R proteins. Both eukaryotic and bacterial effectors may also be under selection to acquire the ability to recognize novel virulence targets. Whatever the case, next‐generation sequencing technologies will provide the sequence for many effector gene alleles, making it possible to identify polymorphisms within effector families. These polymorphisms are likely to help us hone in on important regions within effectors.

TARGET FUNCTION DISCOVERY

In some cases, effector targets have turned out to be proteins already known to be involved in plant immunity. This includes the RIN4 protein targeted by the type III effectors AvrRpt2, AvrRpm1 and AvrB (Axtell and Staskawicz, 2003; 2003, 2002), and the PAMP receptor kinases targeted by AvrPto and AvrPtoB (Gimenez‐Ibanez et al., 2009; Gohre et al., 2008; Shan et al., 2008; Xiang et al., 2008). AvrB has also been reported to target the RAR1 protein (Shang et al., 2006), which is a protein found in R protein complexes. In other cases, the identification of effector targets has revealed a novel component of innate immunity. For example, the P. syringae HopM1 and HopU1 effectors target AtMin7 (Nomura et al., 2006), involved in vesicle trafficking, and AtGRP7 (Fu et al., 2007), a glycine‐rich RNA‐binding (GR‐RBP) protein, respectively. These targets essentially identified vesicle trafficking and the activities of GR‐RBP as important components of innate immunity. Once novel effector targets are discovered, a similar battery of approaches can be used to determine their function in pathogen–plant interactions. Many of these are listed in the bottom portion of Fig. 1.

The identification of pathogenicity phenotypes in plants lacking and over‐expressing the target may determine the extent to which the target is involved in innate immunity or other plant processes co‐opted by pathogens. Plants over‐expressing the target or expressing a target that no longer interacts with the effector may lead to greater resistance to biotic stress. Studies of target protein polymorphisms and their relationship to effector efficacy will indicate whether the target is under evolutionary pressure to diversify. This will not only validate the target's importance, but also illustrate the co‐evolutionary dynamic between the pathogen and its host.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Molecular plant pathologists are on the verge of the identification of thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of pathogen effectors. Improvements in bioinformatics approaches will be critical for handling and analysing this deluge of information. This information promises to answer some of the long‐standing questions of plant pathology—Why can some organisms infect plants? What factors control host specificity and nonhost resistance? At least part of the answer to these questions will probably be found in the effector repertories possessed by different plant pathogens. However, given that some effectors induce ETI, whereas others suppress it, and that these activities may be altered by effector polymorphisms, it is probably unlikely that the effector repertoire alone will answer these questions. Instead, extensive molecular characterization will be needed to determine the activity of each effector and, from this, patterns should emerge that will shed important light on the above questions.

The other fascinating question that will soon be explored is what host processes are targeted by these newly discovered effectors. Will they primarily target plant innate immunity, as do the majority of bacterial type III effectors (Boller and He, 2009; Guo et al., 2009)? Do effectors target host processes that allow for water and nutrient acquisition? Bioinformatics approaches will be important for the identification of effector function and targets. It is satisfying to realize that effector target identification will probably result in novel biotechnology applications and improvements in agriculture. Research advances in molecular plant–microbe interactions over the past 25 years, together with important technological advances, have paved an excellent road, which should allow for major research progress in the near future. And to paraphrase the songwriter Willie Nelson—I just can't wait to get on the effector road again.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Anna Block for reviewing the manuscript. Research in my laboratory is currently being supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (Award No. MCB‐0544447), United States Department of Agriculture (2007‐35319‐18336), National Institutes of Health (Award No. 1R01AI069146‐01A2) and funds from the Center for Plant Science Innovation at the University of Nebraska.

REFERENCES

- Abramovitch, R.B. , Anderson, J.C. and Martin, G.B. (2006) Bacterial elicitation and evasion of plant innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 601–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano, J.R. and Collmer, A. (1996) Bacterial pathogens in plants: life up against the wall. Plant Cell, 8, 1683–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angot, A. , Peeters, N. , Lechner, E. , Vailleau, F. , Baud, C. , Gentzbittel, L. , Sartorel, E. , Genschik, P. , Boucher, C. and Genin, S. (2006) Ralstonia solanacearum requires F‐box‐like domain‐containing type III effectors to promote disease on several host plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 14620–14625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angot, A. , Vergunst, A. , Genin, S. and Peeters, N. (2007) Exploitation of eukaryotic ubiquitin signaling pathways by effectors translocated by bacterial type III and type IV secretion systems. PLoS Pathog 3, e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M.R. , Whisson, S.C. , Pritchard, L. , Bos, J.I. , Venter, E. , Avrova, A.O. , Rehmany, A.P. , Bohme, U. , Brooks, K. , Cherevach, I. , Hamlin, N. , White, B. , Fraser, A. , Lord, A. , Quail, M.A. , Churcher, C. , Hall, N. , Berriman, M. , Huang, S. , Kamoun, S. , Beynon, J.L. and Birch, P.R. (2005) An ancestral oomycete locus contains late blight avirulence gene Avr3a, encoding a protein that is recognized in the host cytoplasm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 7766–7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, R. , Brandmaier, S. , Kleine, F. , Tischler, P. , Heinz, E. , Behrens, S. , Niinikoski, A. , Mewes, H.W. , Horn, M. and Rattei, T. (2009) Sequence‐based prediction of type III secreted proteins. PLoS Pathog 5, e1000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell, M.J. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2003) Initiation of RPS2‐specified disease resistance in Arabidopsis is coupled to the AvrRpt2‐directed elimination of RIN4. Cell, 112, 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch, P.R. , Boevink, P.C. , Gilroy, E.M. , Hein, I. , Pritchard, L. and Whisson, S.C. (2008) Oomycete RXLR effectors: delivery, functional redundancy and durable disease resistance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch, P.R. , Rehmany, A.P. , Pritchard, L. , Kamoun, S. and Beynon, J.L. (2006) Trafficking arms: oomycete effectors enter host plant cells. Trends Microbiol. 14, 8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block, A. , Li, G. , Fu, Z.Q. and Alfano, J.R. (2008) Phytopathogen type III effector weaponry and their plant targets. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller, T. and He, S.Y. (2009) Innate immunity in plants: an arms race between pattern recognition receptors in plants and effectors in microbial pathogens. Science, 324, 742–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos, J.I. , Kanneganti, T.D. , Young, C. , Cakir, C. , Huitema, E. , Win, J. , Armstrong, M.R. , Birch, P.R. and Kamoun, S. (2006) The C‐terminal half of Phytophthora infestans RXLR effector AVR3a is sufficient to trigger R3a‐mediated hypersensitivity and suppress INF1‐induced cell death in Nicotiana benthamiana . Plant J. 48, 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner, D. , Noel, L. , Thieme, F. and Bonas, U. (2003) Genomic approaches in Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria allow fishing for virulence genes. J. Biotechnol. 106, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzariti, A.M. , Dodds, P.N. , Lawrence, G.J. , Ayliffe, M.A. and Ellis, J.G. (2006) Haustorially expressed secreted proteins from flax rust are highly enriched for avirulence elicitors. Plant Cell, 18, 243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. , Zou, Y. , Shang, Y. , Lin, H. , Wang, Y. , Cai, R. , Tang, X. and Zhou, J.M. (2008) Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein–protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiol. 146, 368–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, S.T. , Coaker, G. , Day, B. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2006) Host–microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell, 124, 803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collmer, A. , Lindeberg, M. , Petnicki‐Ocwieja, T. , Schneider, D. and Alfano, J.R. (2002) Genomic mining type III secretion system effectors in Pseudomonas syringae yields new picks for all TTSS prospectors. Trends Microbiol. 10, 462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnac, S. , Occhialini, A. , Barberis, P. , Boucher, C. and Genin, S. (2004) Inventory and functional analysis of the large Hrp regulon in Ralstonia solanacearum: identification of novel effector proteins translocated to plant host cells through the type III secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E.L. , Hussey, R.S. , Mitchum, M.G. and Baum, T.J. (2008) Parasitism proteins in nematode–plant interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deslandes, L. , Olivier, J. , Peeters, N. , Feng, D.X. , Khounlotham, M. , Boucher, C. , Somssich, I. , Genin, S. and Marco, Y. (2003) Physical interaction between RRS1‐R, a protein conferring resistance to bacterial wilt, and PopP2, a type III effector targeted to the plant nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 8024–8029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, P.N. , Lawrence, G.J. , Catanzariti, A.M. , Teh, T. , Wang, C.I. , Ayliffe, M.A. , Kobe, B. and Ellis, J.G. (2006) Direct protein interaction underlies gene‐for‐gene specificity and coevolution of the flax resistance genes and flax rust avirulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103: 8888–8893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, P.N. , Rafiqi, M. , Gan, P.H. , Hardham, A.R. , Jones, D.A. and Ellis, J.G. (2009) Effectors of biotrophic fungi and oomycetes: pathogenicity factors and triggers of host resistance. New Phytol. 183, 993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou, D. , Kale, S.D. , Wang, X. , Chen, Y. , Wang, Q. , Wang, X. , Jiang, R.H. , Arredondo, F.D. , Anderson, R.G. , Thakur, P.B. , McDowell, J.M. , Wang, Y. and Tyler, B.M. (2008a) Conserved C‐terminal motifs required for avirulence and suppression of cell death by Phytophthora sojae effector Avr1b. Plant Cell, 20, 1118–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou, D. , Kale, S.D. , Wang, X. , Jiang, R.H. , Bruce, N.A. , Arredondo, F.D. , Zhang, X. and Tyler, B.M. (2008b) RXLR‐mediated entry of Phytophthora sojae effector Avr1b into soybean cells does not require pathogen‐encoded machinery. Plant Cell, 20, 1930–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowen, R.H. , Engel, J.L. , Shao, F. , Ecker, J.R. and Dixon, J.E. (2009) A family of bacterial cysteine protease type III effectors utilizes acylation‐dependent and ‐independent strategies to localize to plasma membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15 867–15 879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J.G. , Rafiqi, M. , Gan, P. , Chakrabarti, A. and Dodds, P.N. (2009) Recent progress in discovery and functional analysis of effector proteins of fungal and oomycete plant pathogens. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, A. and Alfano, J.R. (2004) Disabling surveillance: bacterial type III secretion system effectors that suppress innate immunity. Cell. Microbiol. 6, 1027–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouts, D.E. , Abramovitch, R.B. , Alfano, J.R. , Baldo, A.M. , Buell, C.R. , Cartinhour, S. , Chatterjee, A.K. , Ascenzo, M.D. , Gwinn, M. , Lazarowitz, S.G. , Lin, N.‐C. , Martin, G.B. , Rehm, A.H. , Schneider, D.J. , Van Dijk, K. , Tang, X. and Collmer, A. (2002) Genomewide identification of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 promoters controlled by the HrpL alternative sigma factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 2275–2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.Q. , Guo, M. , Jeong, B.R. , Tian, F. , Elthon, T.E. , Cerny, R.L. , Staiger, D. and Alfano, J.R. (2007) A type III effector ADP ribosylates RNA‐binding proteins and quells plant immunity. Nature, 447, 284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudal, I. , Ross, S. , Gout, L. , Blaise, F. , Kuhn, M.L. , Eckert, M.R. , Cattolico, L. , Bernard‐Samain, S. , Balesdent, M.H. and Rouxel, T. (2007) Heterochromatin‐like regions as ecological niches for avirulence genes in the Leptosphaeria maculans genome: map‐based cloning of AvrLm6. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 20, 459–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furutani, A. , Takaoka, M. , Sanada, H. , Noguchi, Y. , Oku, T. , Tsuno, K. , Ochiai, H. and Tsuge, S. (2009) Identification of novel type III secretion effectors in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan, J.E. (2009) Common themes in the design and function of bacterial effectors. Cell Host. Microbe, 5, 571–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez‐Ibanez, S. , Hann, D.R. , Ntoukakis, V. , Petutschnig, E. , Lipka, V. and Rathjen, J.P. (2009) AvrPtoB targets the LysM receptor kinase CERK1 to promote bacterial virulence on plants. Curr. Biol. 19, 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohre, V. , Spallek, T. , Haweker, H. , Mersmann, S. , Mentzel, T. , Boller, T. , De Torres, M. , Mansfield, J.W. and Robatzek, S. (2008) Plant pattern‐recognition receptor FLS2 is directed for degradation by the bacterial ubiquitin ligase AvrPtoB. Curr. Biol. 18, 1824–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gout, L. , Fudal, I. , Kuhn, M.L. , Blaise, F. , Eckert, M. , Cattolico, L. , Balesdent, M.H. and Rouxel, T. (2006) Lost in the middle of nowhere: the AvrLm1 avirulence gene of the Dothideomycete Leptosphaeria maculans . Mol. Microbiol. 60, 67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M. , Tian, F. , Wamboldt, Y. and Alfano, J.R. (2009) The majority of the type III effectory inventory of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 can suppress plant immunity. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 1069–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, D.S. , Vinatzer, B.A. , Sarkar, S.F. , Ranall, M.V. , Kettler, G. and Greenberg, J.T. (2002) A functional screen for the type III (Hrp) secretome of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae . Science, 295, 1722–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, J. and Kaper, J.B. (2000) Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54, 641–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein, I. , Gilroy, E.M. , Armstrong, M.R. and Birch, P.R. (2009) The zig–zag–zig in oomycete–plant interactions. Mol. Plant Pathol. 10, 547–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, N.L. , Bhattacharjee, S. , Van Ooij, C. , Liolios, K. , Harrison, T. , Lopez‐Estrano, C. and Haldar, K. (2004) A host‐targeting signal in virulence proteins reveals a secretome in malarial infection. Science, 306, 1934–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogenhout, S.A. , Van der Hoorn, R.A. , Terauchi, R. and Kamoun, S. (2009) Emerging concepts in effector biology of plant‐associated organisms. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houterman, P.M. , Cornelissen, B.J. and Rep, M. (2008) Suppression of plant resistance gene‐based immunity by a fungal effector. PLoS. Pathog. 4, e1000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelenska, J. , Yao, N. , Vinatzer, B.A. , Wright, C.M. , Brodsky, J.L. and Greenberg, J.T. (2007) A J domain virulence effector of Pseudomonas syringae remodels host chloroplasts and suppresses defenses. Curr. Biol. 17, 499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D. and Dangl, J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature, 444, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhas, M. , Van Der Meer, J.R. , Gaillard, M. , Harding, R.M. , Hood, D.W. and Crook, D.W. (2009) Genomic islands: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 376–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun, S. (2007) Groovy times: filamentous pathogen effectors revealed. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10, 358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamper, J. , Kahmann, R. , Bolker, M. , Ma, L.J. , Brefort, T. , Saville, B.J. , Banuett, F. , Kronstad, J.W. , Gold, S.E. , Muller, O. , Perlin, M.H. , Wosten, H.A. , De Vries, R. , Ruiz‐Herrera, J. , Reynaga‐Pena, C.G. , Snetselaar, K. , McCann, M. , Perez‐Martin, J. , Feldbrugge, M. , Basse, C.W. , Steinberg, G. , Ibeas, J.I. , Holloman, W. , Guzman, P. , Farman, M. , Stajich, J.E. , Sentandreu, R. , Gonzalez‐Prieto, J.M. , Kennell, J.C. , Molina,. L. , Schirawski, J. , Mendoza‐Mendoza, A. , Greilinger, D. , Munch, K. , Rossel, N. , Scherer, M. , Vranes, M. , Ladendorf, O. , Vincon, V. , Fuchs, U. , Sandrock, B. , Meng, S. , Ho, E.C. , Cahill, M.J. , Boyce, K.J. , Klose, J. , Klosterman, S.J. , Deelstra, H.J. , Ortiz‐Castellanos, L. , Li, W. , Sanchez‐Alonso, P. , Schreier, P.H. , Hauser‐Hahn, I. , Vaupel, M. , Koopmann, E. , Friedrich, G. , Voss, H. , Schluter, T. , Margolis, J. , Platt, D. , Swimmer, C. , Gnirke, A. , Chen, F. , Vysotskaia, V. , Mannhaupt, G. , Guldener, U. , Munsterkotter, M. , Haase, D. , Oesterheld, M. , Mewes, H.W. , Mauceli, E.W. , DeCaprio, D. , Wade, C.M. , Butler, J. , Young, S. , Jaffe, D.B. , Calvo, S. , Nusbaum, C. , Galagan, J. and Birren, B.W. (2006) Insights from the genome of the biotrophic fungal plant pathogen Ustilago maydis . Nature, 444, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti, T.D. , Bai, X. , Tsai, C.W. , Win, J. , Meulia, T. , Goodin, M. , Kamoun, S. and Hogenhout, S.A. (2007) A functional genetic assay for nuclear trafficking in plants. Plant J. 50, 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, S. and Bonas, U. (2009) How Xanthomonas type III effectors manipulate the host plant. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemen, E. , Kemen, A.C. , Rafiqi, M. , Hempel, U. , Mendgen, K. , Hahn, M. and Voegele, R.T. (2005) Identification of a protein from rust fungi transferred from haustoria into infected plant cells. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 18, 1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.F. and Alfano, J.R. (2002) Pathogenicity islands and virulence plasmids of bacterial plant pathogens In: Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology (Hacker J. ed), pp. 127–147. Berlin: Springer‐Verlag. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J. , Lin, N.‐C. and Martin, G.B. (2002) Two distinct Pseudomonas effector proteins interact with the Pto kinase and activate plant immunity. Cell, 109, 589–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeberg, M. , Cartinhour, S. , Myers, C.R. , Schechter, L.M. , Schneider, D.J. and Collmer, A. (2006) Closing the circle on the discovery of genes encoding Hrp regulon members and type III secretion system effectors in the genomes of three model Pseudomonas syringae strains. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 1151–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, P.B. , Peet, R.C. and Panopoulos, N.J. (1986) Gene cluster of Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola controls pathogenicity of bean plants and hypersensitivity on nonhost plants. J. Bacteriol. 168, 512–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W. and Guttman, D.S. (2008) Evolution of prokaryotic and eukaryotic virulence effectors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, D. , Belkhadir, Y. , Alonso, J.M. , Ecker, J.R. and Dangl, J.L. (2003) Arabidopsis RIN4 is a target of the type III virulence effector AvrRpt2 and modulates RPS2‐mediated resistance. Cell, 112, 379–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, D. , Holt, B.F., III , Wiig, A. and Dangl, J.L. (2002) RIN4 interacts with Pseudomonas syringae type III effector molecules and is required for RPM1‐mediated resistance in Arabidopsis . Cell, 108, 743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti, M. , Good, R.T. , Rug, M. , Knuepfer, E. and Cowman, A.F. (2004) Targeting malaria virulence and remodeling proteins to the host erythrocyte. Science, 306, 1930–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, O. , Kahmann, R. , Aguilar, G. , Trejo‐Aguilar, B. , Wu, A. and De Vries, R.P. (2008) The secretome of the maize pathogen Ustilago maydis . Fungal Genet. Biol. 45 (Suppl 1), S63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimchuk, Z. , Marois, E. , Kjemtrup, S. , Leister, R.T. , Katagiri, F. and Dangl, J.L. (2000) Eukaryotic fatty acylation drives plasma membrane targeting and enhances function of several type III effector proteins from Pseudomonas syringae . Cell, 101, 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, K. , Debroy, S. , Lee, Y.H. , Pumplin, N. , Jones, J. and He, S.Y. (2006) A bacterial virulence protein suppresses host innate immunity to cause plant disease. Science, 313, 220–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell, R.J. and Panstruga, R. (2006) Tête à tête inside a plant cell: establishing compatibility between plants and biotrophic fungi and oomycetes. New Phytol. 171, 699–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panstruga, R. and Dodds, P.N. (2009) Terrific protein traffic: the mystery of effector protein delivery by filamentous plant pathogens. Science, 324, 748–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petnicki‐Ocwieja, T. , Schneider, D.J. , Tam, V.C. , Chancey, S.T. , Shan, L. , Jamir, Y. , Schechter, L.M. , Janes, M.D. , Buell, C.R. , Tang, X. , Collmer, A. and Alfano, J.R. (2002) Genomewide identification of proteins secreted by the Hrp type III protein secretion system of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 7652–7657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poueymiro, M. and Genin, S. (2009) Secreted proteins from Ralstonia solanacearum: a hundred tricks to kill a plant. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehmany, A.P. , Gordon, A. , Rose, L.E. , Allen, R.L. , Armstrong, M.R. , Whisson, S.C. , Kamoun, S. , Tyler, B.M. , Birch, P.R. and Beynon, J.L. (2005) Differential recognition of highly divergent downy mildew avirulence gene alleles by RPP1 resistance genes from two Arabidopsis lines. Plant Cell, 17, 1839–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentel, M.C. , Leonelli, L. , Dahlbeck, D. , Zhao, B. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2008) Recognition of the Hyaloperonospora parasitica effector ATR13 triggers resistance against oomycete, bacterial, and viral pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 1091–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout, C.J. , Skamnioti, P. , Porritt, O. , Sacristan, S. , Jones, J.D. and Brown, J.K. (2006) Multiple avirulence paralogues in cereal powdery mildew fungi may contribute to parasite fitness and defeat of plant resistance. Plant Cell, 18, 2402–2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert‐Seilaniantz, A. , Shan, L. , Zhou, J.M. and Tang, X. (2006) The Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 type III effector HopF2 has a putative myristoylation site required for its avirulence and virulence functions. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samudrala, R. , Heffron, F. and McDermott, J.E. (2009) Accurate prediction of secreted substrates and identification of a conserved putative secretion signal for type III secretion systems. PLoS Pathog 5, e1000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L. , He, P. , Li, J. Heese, A. , Peck, S.C. , Nurnberger, T. , Martin, G.B. and Sheen, J. (2008) Bacterial effectors target the common signaling partner BAK1 to disrupt multiple MAMP receptor‐signaling complexes and impede plant immunity. Cell Host Microbe 4, 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L. , Thara, V.K. , Martin, G.B. , Zhou, J. and Tang, X. (2000) The Pseudomonas AvrPto protein is differentially recognized by tomato and tobacco and is localized to the plant plasma membrane. Plant Cell, 12, 2323–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y. , Li, X. , Cui, H. , He, P. , Thilmony, R. , Chintamanani, S. , Zwiesler‐Vollick, J. , Gopalan, S. , Tang, X. and Zhou, J.M. (2006) RAR1, a central player in plant immunity, is targeted by Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 19 200–19 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, K.H. , Lei, R. , Nemri, A. and Jones, J.D. (2007) The downy mildew effector proteins ATR1 and ATR13 promote disease susceptibility in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Cell, 19, 4077–4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staskawicz, B.J. , Dahlbeck, D. and Keen, N.T. (1984) Cloned avirulence gene of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea determines race‐specific incompatibility on Glycine max (L.) Merr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 81, 6024–6028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X. , Frederick, R.D. , Zhou, J. , Halterman, D.A. , Jia, Y. and Martin, G.B. (1996) Physical interaction of AvrPto and the Pto kinase defines a recognition event involved in plant disease resistance. Science, 274, 2060–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X. , Xiao, Y. and Zhou, J.M. (2006) Regulation of the type III secretion system in phytopathogenic bacteria. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 1159–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torto, T.A. , Li, S. , Styer, A. , Huitema, E. , Testa, A. , Gow, N.A. , Van West, P. and Kamoun, S. (2003) EST mining and functional expression assays identify extracellular effector proteins from the plant pathogen Phytophthora . Genome Res. 13, 1675–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, B.M. (2009) Entering and breaking: virulence effector proteins of oomycete plant pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 11, 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, B.M. , Tripathy, S. , Zhang, X. , Dehal, P. , Jiang, R.H. , Aerts, A. , Arredondo, F.D. , Baxter, L. , Bensasson, D. , Beynon, J.L. , Chapman, J. , Damasceno, C.M. , Dorrance, A.E. , Dou, D. , Dickerman, A.W. , Dubchak, I.L. , Garbelotto, M. , Gijzen, M. , Gordon, S.G. , Govers, F. , Grunwald, N.J. , Huang, W. , Ivors, K.L. , Jones, R.W. , Kamoun, S. , Krampis, K. , Lamour, K.H. , Lee, M.K. , McDonald, W.H. , Medina, M. , Meijer, H.J. , Nordberg, E.K. , Maclean, D.J. , Ospina‐Giraldo, M.D. , Morris, P.F. , Phuntumart, V. , Putnam, N.H. , Rash, S. , Rose, J.K. , Sakihama, Y. , Salamov, A.A. , Savidor, A. , Scheuring, C.F. , Smith, B.M. , Sobral, B.W. , Terry, A. , Torto‐Alalibo, T.A. , Win, J. , Xu, Z. , Zhang, H. , Grigoriev, I.V. , Rokhsar, D.S. and Boore, J.L. (2006) Phytophthora genome sequences uncover evolutionary origins and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science, 313, 1261–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ackerveken, G. , Marois, E. and Bonas, U. (1996) Recognition of the bacterial avirulence protein AvrBs3 occurs inside the host plant cell. Cell, 87, 1307–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gijsegem, F. , Genin, S. and Boucher, C. (1993) Conservation of secretion pathways for pathogenicity determinants of plant and animal bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 1, 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisson, S.C. , Boevink, P.C. , Moleleki, L. , Avrova, A.O. , Morales, J.G. , Gilroy, E.M. , Armstrong, M.R. , Grouffaud, S. , Van West, P. , Chapman, S. , Hein, I. , Toth, I.K. , Pritchard, L. and Birch, P.R. (2007) A translocation signal for delivery of oomycete effector proteins into host plant cells. Nature, 450, 115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Win, J. , Morgan, W. , Bos, J. , Krasileva, K.V. , Cano, L.M. , Chaparro‐Garcia, A. , Ammar, R. , Staskawicz, B.J. and Kamoun, S. (2007) Adaptive evolution has targeted the C‐terminal domain of the RXLR effectors of plant pathogenic oomycetes. Plant Cell, 19, 2349–2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, T. , Zong, N. , Zou, Y. , Wu, Y. , Zhang, J. , Xing, W. , Li, Y. , Tang, X. , Zhu, L. , Chai, J. and Zhou, J.M. (2008) Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPto blocks innate immunity by targeting receptor kinases. Curr. Biol. 18, 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. and Gabriel, D.W. (1995) Xanthomonas avirulence/pathogenicity gene family encodes functional plant nuclear targeting signals. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 8, 627–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. , Shao, F. , Li, Y. , Cui, H. , Chen, L. , Li, H. , Zou, Y. , Long, C. , Lan, L. , Chai, J. , Chen, S. , Tang, X. and Zhou, J.M. (2007) A Pseudomonas syringae effector inactivates MAPKs to suppress PAMP‐induced immunity in plants. Cell Host Microbe, 1, 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.M. and Chai, J. (2008) Plant pathogenic bacterial type III effectors subdue host responses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W. , Yang, B. , Wills, N. , Johnson, L.B. and White, F.F. (1999) The C terminus of AvrXa10 can be replaced by the transcriptional activation domain of VP16 from the herpes simplex virus. Plant Cell, 11, 1665–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwiesler‐Vollick, J. , Plovanich‐Jones, A.E. , Nomura, K. , Bandyopadhyay, S. , Joardar, V. , Kunkel, B.N. and He, S.Y. (2002) Identification of novel hrp‐regulated genes through functional genomic analysis of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genome. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1207–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]