Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this secondary analysis was to examine the effects of modafinil on the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and residual excessive sleepiness with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) use. We also explored the association of improvement of functional status with the presenting level of subjective sleepiness.

Methods:

Data were pooled from 2 randomized placebo-controlled studies (4-week and 12-week interventions) of modafinil in patients with residual sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale score ≥ 10 on CPAP).

Results:

The analysis included 480 patients (FOSQ efficacy data n = 442 patients), 292 in the modafinil group and 188 in the placebo group. The mean age (SD) of the analyzed sample was 49.7 (9.2) years; 76% were men. Following administration with modafinil, there were greater improvements from baseline in the Total score (p < 0.0001) as well as 4 of the 5 domains (p < 0.05), compared with placebo. A greater proportion of patients who received modafinil were considered responders, compared with patients who received placebo (45% vs 25%; p < 0.001). Responder analysis based on the individual FOSQ domain items demonstrated that 18 of the 30 FOSQ items increased by at least 1 point for significantly more patients who received modafinil (p < 0.05). Improvements in functional status were not found to depend on patients' degree of subjective sleepiness at baseline.

Conclusion:

In this secondary analysis of data from patients with OSA and excessive sleepiness despite CPAP use, modafinil was associated with improvements in patients' functional outcomes and their ability to engage in a broad array of everyday activities.

Citation:

Weaver TE; Chasens ER; Arora S. Modafinil improves functional outcomes in patients with residual excessive sleepiness associated with CPAP treatment. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(6):499-505.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea, OSA, continuous positive airway pressure, CPAP, modafinil, residual excessive sleepiness, persistent sleepiness, Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire, Epworth Sleepiness Scale

Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSA) has been shown to be associated with substantial morbidity and increased mortality.1–8 A condition as common as diabetes, OSA is estimated to occur in 2% to 4% of middle-aged adults.9 Excessive sleepiness is a common and often debilitating symptom of OSA in which sleep is disturbed or fragmented by repeated arousals caused by partial or complete airway obstruction.3 This hypersomnolence can result in profound impairment in daytime functioning, psychosocial dysfunction, cognitive impairment, decreased vigilance, and diminished quality of life.3, 10–14 Moreover, patients with OSA are at increased risk for having work-related and automobile accidents.3, 15–19

The first-line treatment for OSA is nasal continuous airway pressure (CPAP),20 which has been shown to be effective in alleviating the underlying obstruction as well as reducing patients' excessive sleepiness and improving their functioning and health-related quality of life.13, 21–26 However, even among those who use CPAP as recommended through the night, some experience residual excessive sleepiness.14, 27, 28 Indeed, in a recent study, 22% of those who used CPAP for 6 or more hours per night reported excessive sleepiness, and 52% had objective evidence of physiologic sleepiness, as measured by the Multiple Sleep Latency Test.14

Modafinil, a wakefulness-promoting agent, has been shown to improve wakefulness in patients with OSA who remain excessively sleepy despite CPAP use. In this population, multiple double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have shown that modafinil consistently improves wakefulness on objective measures of excessive sleepiness, patients' overall clinical condition, patients' ability to sustain attention, and enhances quality of life.29–31 Chemically and pharmacologically distinct from the central nervous system stimulants,32, 33 modafinil has been shown to have a lower abuse potential and lower risk for causing adverse cardiovascular events.34

The purpose of the current study was to examine further the effect of modafinil on daily functioning, a component of quality of life, of patients with OSA experiencing residual excessive sleepiness despite CPAP use using data from 2 previously conducted placebo-controlled studies. Specifically, we examined the changes from baseline in the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), a measure of daily functioning, using the Total score and individual domain scores to identify FOSQ responders among the entire OSA study population. We also explored the association between improvement in functional status and patients' subjective level of sleepiness at baseline.

METHODS

The original study design and results of the 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies used to conduct the secondary analysis have been reported elsewhere.29–31 Posthoc analyses were based on the pooled results from these 2 studies.

Instruments

Daily Functioning

Daily functioning was measured by the FOSQ.35 Designed specifically to assess the impact of excessive sleepiness on daily tasks and roles, this self-administered validated instrument consists of 30 questions about individual items, divided into 5 domains: activity level (9 questions), vigilance (7 questions), intimacy (4 questions), general productivity (8 questions), and social outcome (2 questions).35 The range of scores is 5 to 20 for the Total score and 1 to 4 (1 = Yes, extreme difficulty; 4 = No, no difficulty) for each of the 5 domains. Each domain score is a mean of 1 to 4 on each of the individual item questions; higher scores indicate greater functioning.

The FOSQ has been shown to discriminate successfully between normal subjects and those seeking medical attention for a sleep problem, while demonstrating excellent internal reliability (Cronbach's α coefficients for the reliability of internal consistency [i.e., the degree to which each item relates to other items within a scale] range from 0.86 to 0.91 for the individual domains and 0.95 for Total scale).35 In the current FOSQ responder analysis, the criteria for clinically meaningful changes were based on the instrument's previously reported test-retest reliability (coefficients ranged from 0.81 to 0.90 for the 5 domains and 0.90 for the total measure). They were defined as follows: a change of 2 or greater on the Total score and a change of 1 or greater on the individual items.35

Other Assessments

The Maintenance of Wakefulness Test36 was used to objectively assess sleepiness. Patients were instructed to see how long they could stay awake when placed in a dark room. Mean sleep latency (i.e., time to onset of sleep) was calculated from latencies obtained during four 20-minute sessions. Changes in self-reported sleepiness were measured using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS).37, 38

The ESS is a well-validated and reliable instrument that has been used extensively in sleep apnea research to measure how likely patients with sleep disorders are to fall asleep in 8 situations previously determined to be soporific—some more so than others.37, 38 A score is produced by summing the responses for each item, with scores ranging from 0 to 24. Scores of 10 or greater have a sensitivity of 93.5% and specificity of 100% to distinguish pathologic from normal daytime sleepiness.38

Overall clinical condition was assessed with the Clinical Global Impression of Severity.39 This scale, completed by a practitioner, employs a 7-item Likert scale (1 = normal, not ill; 7 = extremely ill) to document the clinician's impression of the patient's overall disease state and response to treatment.

Procedure

For this secondary analysis, data were pooled from 2 previously conducted, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group studies (4-week and 12-week intervention, respectively) of modafinil in patients with residual excessive sleepiness, defined as an ESS score of 10 or greater on CPAP treatment. Details of the methodology of these studies are reported elsewhere29, 30 and are briefly summarized below.

The 4-week study,29 conducted at 22 centers in the United States, included patients aged 28 to 76 years with an ESS score of at least 10 despite regular use of CPAP treatment. Efficacy of CPAP, defined as an apnea-hypopnea index less than 10, was confirmed based on 2 nights of home monitoring using the ResMed Autoset T™ device (ResMed Corporation, San Diego, CA) set to the participant's prescribed pressure. Adherence to therapy, defined as at least 4 hours per night on a minimum of 5 out of 7 objectively monitored nights, was confirmed over a 3-week period prior to randomization. Participants were then randomly assigned to receive either modafinil or placebo during the 4-week double-blind period. The modafinil group received a daily dose of modafinil of 200 mg for 1 week, followed by modafinil, 400 mg per day, for the remainder of the study.

The 12-week study,30 conducted at 38 centers in the United States and 4 centers in the United Kingdom, included patients 24 to 70 years of age with excessive sleepiness (ESS score ≥ 10) despite CPAP use who were randomly assigned to receive once-daily modafinil, 200 mg or 400 mg, or placebo over the 12-week double-blind period. Based on a 2-week preenrollment assessment of CPAP use and treatment efficacy, as described above, patients were stratified into 3 subpopulations—CPAP compliant ( ≥ 4 hours per night on ≥ 70% of objectively monitored nights), partially CPAP compliant ( ≥ 4 hours per night on > 30% of objectively monitored nights) and nonusers of CPAP. Nonusers of CPAP were subsequently excluded from the efficacy analyses.

In both of these studies, patients were excluded if, at screening or baseline, they had any active or clinically significant chronic psychiatric disorder requiring routine medication (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were permitted, if the patient was on a stable dose) or reported any history of hospitalization for a psychiatric disorder; gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, hepatic, renal, hematologic, neoplastic, endocrine, or neurologic disorder/disease; hypertension; obstructive respiratory disease; central hypoventilation; glaucoma; or insulin-dependent diabetes.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from all patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug and had at least 1 postbaseline FOSQ assessment. The mean change from baseline in the FOSQ variables, including the Total score and 5 individual domain scores, was analyzed. Integrated FOSQ data were analyzed by an analysis of covariance model using the Total score and the 5 domain scores. The model included treatment (200 mg, 400 mg, or placebo) as the main effect, site (protocol) as a random effect, and baseline as a covariate if there was no treatment-by-baseline interaction at the 0.1 level. Treatment-by-baseline interaction for each analysis was tested in a separate model by adding treatment-by-baseline interaction in the above-mentioned model. Significant treatment-by-baseline interaction was observed in the analysis for the change in vigilance score so the change in this score was analyzed using an analysis of variance model without having baseline as a covariate. All p values were not adjusted for multiplicity. Participants were considered to be “responders” to modafinil treatment if their Total score increased by at least 2 points and each individual domain score by at least 1 point. Those whose Total score did not change by at least 2 points and who did not get worse compared with baseline were considered to be “stable.” “Nonresponders” were those without a 2-point or greater change in Total score and a decrease in each individual domain score. The responder rate based on Total score of both dose cohorts was analyzed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test controlling for study center.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

In total, the analysis included 480 patients—292 in the modafinil group and 188 in the placebo group (safety analysis set). FOSQ efficacy data were available for 442 patients: 263 for the modafinil group and 179 for the placebo group. Baseline characteristics of the combined samples are presented in Table 1. The mean (SD) age of the analyzed sample was 49.7 (9.2) years, and 76% were men. Despite the use of CPAP therapy and because of the inclusion criteria for excessive sleepiness (ESS ≥ 10), the majority of patients in the OSA studies were at least moderately ill at baseline, as determined by the Clinical Global Impression of Severity assessment, and had residual excessive sleepiness, as shown on both objective and subjective measures. The mean baseline scores ranged from 13.1 to 13.8 on the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test, and the mean ESS scores ranged from 14.6 to 15.7. Mean sleep efficiency (time asleep as a percentage of total time in bed), as determined by polysomnography, was 85.8% for the patients at baseline.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics of the 480 Patients with OSA in the Combined Study Populations

| Demographic or baseline characteristic | Modafinil, 200 mg (n = 109) | Modafinil, 400 mg (n = 183) | All Modafinil (n = 292) | Placebo (n = 188) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 48.0 ± 10.0 | 49.2 ± 8.7 | 48.7 ± 9.2 | 50.6 ± 9.6 |

| Range | 24–68 | 28–76 | 24–76 | 28–72 |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 94 (86) | 135 (74) | 229 (78) | 139 (74) |

| Women | 15 (14) | 48 (26) | 63 (22) | 49 (26) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 96 (88) | 161 (88) | 257 (88) | 166 (88) |

| Black | 7 (6) | 15 (8) | 22 (8) | 13 (7) |

| Other | 6 (6) | 7 (4) | 13 (4) | 9 (5) |

| Weight, kg | 109.5 ± 23.4 | 110.3 ± 24.4 | 110.0 ± 24.0 | 109.6 ± 24.1 |

| Sleep efficiency, %ab | 86.7 ± 8.4 | 86.5 ± 10.8 | 86.6 ± 10.0 | 84.6 ± 12.4 |

| CGI-S ratingb | ||||

| Not recorded | 0 | 21 (13) | 21 (8) | 22 (12) |

| Normal/mildly ill/slightly ill | 36 (36) | 41 (25) | 77 (29) | 44 (24) |

| Moderately ill | 45 (45) | 69 (41) | 114 (43) | 85 (47) |

| Markedly ill/severely or extremely ill | 18 (18) | 36 (22) | 54 (20) | 29 (16) |

Data are presented as number (%) or mean ± SD. OSA refers to obstructive sleep apnea.

Time spent asleep as a percentage of time in bed.

Sleep efficiency and Clinical Global Impression severity (CGI-S) data are from the efficacy evaluable set; age, sex, race, and weight data are from the safety analysis set.

Functional Outcomes

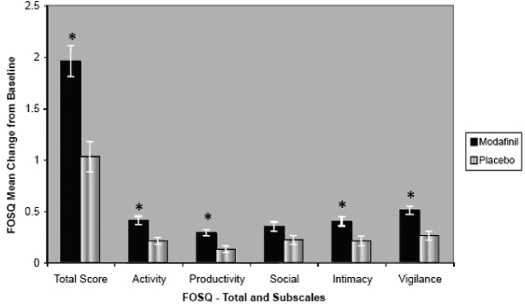

Analysis of pooled data from the 4-week and 12-week OSA studies demonstrated that modafinil significantly improved Total score and individual domain scores compared with placebo (p < 0.05) (Figure 1). The respective mean (SD) changes from baseline following administration of modafinil and placebo were 1.96 (2.45) versus 1.03 (1.96) for Total score (p < 0.0001), 0.41 (0.60) versus 0.21 (0.47) for Activity Level (p = 0.002), 0.29 (0.47) versus 0.13 (0.43) for Productivity level (p = 0.0007), 0.35 (0.73) versus 0.22 (0.58) for Social Outcome (p = 0.13), 0.40 (0.68) versus 0.22 (0.61) for Intimacy and Sexual Relationships (p = 0.01), and 0.51 (0.62) versus 0.26 (0.58) for Vigilance (p < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Mean change from baseline in Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ) Total and individual domain scores for the combined populations with obstructive sleep apnea in the studies. p < 0.05 versus placebo. Values are shown as SEM.

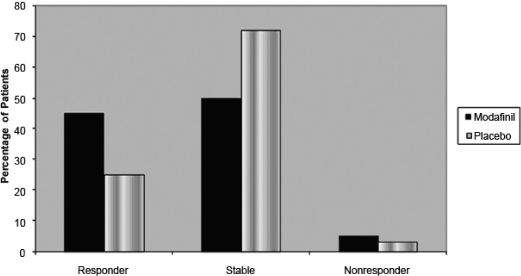

Among the combined OSA study populations, a significantly greater proportion of patients who received modafinil were considered responders, compared with patients who received placebo (45% vs 25%; p < 0.001) (Figure 2). Additionally, the responder analysis demonstrated that, for a significantly greater proportion of patients who received modafinil (p < 0.05), scores on 18 of the 30 individual item questions increased at least 1 point, including 5 of 9 items relating to activity level, 4 of 8 items relating to productivity level, 2 of 4 items relating to intimacy, 2 of 2 items relating to social outcome, and 5 of 7 items relating to vigilance (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Responders among the combined populations with obstructive sleep apnea in the studies based on changes from baseline in Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ) Total Score. Participants were considered to be “responders” to modafinil treatment if their Total score increased by ≥ 2 points and each individual domain score by ≥ 1 point. Those whose Total score did not change by ≥ 2 points and did not worsen compared with baseline were considered to be “stable.” “Nonresponders” were those without a ≥ 2-point change in Total score and a decrease in each individual domain score.

Table 2.

Responders Among the Combined Population of Patients with OSA Based on Changes from Baseline in Individual FOSQ Subscale Items

| Subscale and questions | Modafinil n = 263 | Placebo n = 179 |

|---|---|---|

| Activity Level | ||

| Do you have difficulty doing work around the house (for example, cleaning house, doing laundry, taking out the trash, repair work) because you are sleepy or tired? | 112 (44)a | 53 (30) |

| Do you have difficulty doing things for your family or friends because you are too sleepy or tired? | 95 (36) | 60 (34) |

| Has your relationship with family, friends or work colleagues been affected because you are sleepy or tired? | 96 (37) | 62 (35) |

| Do you have difficulty exercising or participating in a sporting activity because you are too sleepy or tired? | 90 (39)a | 41 (27) |

| Do you have difficulty being as active as you want to be in the evening because you are sleepy or tired? | 138 (53)a | 65 (36) |

| Do you have difficulty being as active as you want to be in the morning because you are sleepy or tired? | 106 (40) | 62 (35) |

| Do you have difficulty being as active as you want to be in the afternoon because you are sleepy or tired? | 141 (54)a | 71 (40) |

| Do you have difficulty keeping pace with others your own age because you are sleepy or tired? | 115 (46)a | 54 (32) |

| How would you rate your general level of activity? | 76 (29) | 42 (24) |

| General Productivity | ||

| Do you have difficulty concentrating on the things you do because you are sleepy or tired? | 123 (47)b | 58 (32) |

| Do you generally have difficulty remembering things because you are sleepy or tired? | 114 (44)b | 49 (27) |

| Do you have difficulty finishing a meal because you become sleepy or tired? | 14 (5) | 8 (5) |

| Do you have difficulty working on a hobby (for example, sewing, collecting, gardening) because you are sleepy or tired? | 100 (40) | 54 (31) |

| Do you have difficulty getting things done because you are too sleepy or tired to drive or take public transpiration? | 77 (31)b | 33 (20) |

| Do you have difficulty taking care of financial affairs and doing paperwork (for example, writing checks, paying bills, keeping financial records, filling out tax forms, etc.) because you are sleepy or tired? | 86 (35) | 47 (28) |

| Do you have difficulty performing employed or volunteer work because you are sleepy or tired? | 98 (40) | 53 (32) |

| Do you have difficulty maintaining a telephone conversation because you become sleepy or tired? | 70 (27)b | 33 (19) |

| Intimate Relationships and Sexual Activity | ||

| Has your intimate or sexual relationship been affected because you are sleepy or tired? | 95 (42)b | 40 (27) |

| Has your desire for intimacy or sex been affected because you are sleepy or tired? | 96 (41) | 48 (31) |

| Has your ability to become sexually aroused been affected because you are sleepy or tired? | 87 (36)b | 36 (23) |

| Has your ability to “come” (have an orgasm) been affected because you are sleepy or tired? | 54 (23) | 33 (21) |

| Social Outcome | ||

| Do you have difficulty visiting with your family or friends in your home because you become sleepy or tired? | 109 (42)b | 53 (30) |

| Do you have difficulty visiting with your family or friends in their home because you become sleepy or tired? | 105 (41)b | 49 (28) |

| Vigilance | ||

| Do you have difficulty operating a motor vehicle for short distances (less than 100 miles) because you become sleepy or tired? | 93 (36) | 50 (28) |

| Do you have difficulty operating a motor vehicle for long distances (greater than 100 miles) because you become sleepy or tired? | 112 (45)b | 53 (31) |

| Do you have difficulty watching a movie or videotape because you become sleepy or tired? | 123 (47)b | 64 (36) |

| Do you have difficulty enjoying the theater or a lecture because you become sleepy or tired? | 129 (53)b | 61 (37) |

| Do you have difficulty enjoying a concert because you become sleepy or tired? | 85 (42) | 46 (33) |

| Do you have difficulty watching TV because you are sleepy or tired? | 122 (47)b | 52 (29) |

| Do you have difficulty participating in religious services, meetings or a group or club because you are sleepy or tired? | 111 (50)b | 54 (33) |

Data are presented as number (%). FOSQ refers to the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

p < 0.05.

Responder is defined as a subject having a 1-point or greater change from baseline.

In these patients with OSA and residual excessive sleepiness despite CPAP use, improvements in functional status were not found to depend on the degree of subjective sleepiness at baseline. When divided into quartiles based on the baseline ESS score, the mean change from baseline in Total score and individual domains following modafinil administration was generally similar across the combined studies population and was consistently greater with modafinil than with placebo (Table 3).

Table 3.

Change from Baseline in FOSQ Total and Individual Subscale Scores for the Combined Population from the OSA Studies Based on Quartile Analysis of Baseline Level of Subjective Sleepinessa

| Combined OSA Studies Population |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 ESS ≤ 12 | Quartile 2 ESS 12–15 | Quartile 3 ESS ≥ 15–17 | Quartile 4 ESS ≥ 17 | |

| FOSQ Total Score | ||||

| All modafinil | 1.82 (2.36) | 2.09 (2.33) | 1.98 (2.42) | 1.96 (2.79) |

| Placebo | 0.98 (1.96) | 0.84 (1.92) | 1.23 (1.89) | 1.17 (2.20) |

| Activity Level | ||||

| All modafinil | 0.42 (0.65) | 0.46 (0.52) | 0.39 (0.57) | 0.33 (0.68) |

| Placebo | 0.19 (0.45) | 0.15 (0.49) | 0.30 (0.48) | 0.24 (0.47) |

| General Productivity | ||||

| All modafinil | 0.29 (0.43) | 0.31 (0.45) | 0.30 (0.45) | 0.28 (0.57) |

| Placebo | 0.08 (0.40) | 0.08 (0.41) | 0.19 (0.47) | 0.22 (0.43) |

| Vigilance | ||||

| All modafinil | 0.49 (0.61) | 0.51 (0.55) | 0.53 (0.59) | 0.51 (0.73) |

| Placebo | 0.10 (0.53) | 0.27 (0.54) | 0.41 (0.63) | 0.34 (0.60) |

| Social Outcome | ||||

| All modafinil | 0.29 (0.69) | 0.40 (0.73) | 0.37 (0.75) | 0.34 (0.77) |

| Placebo | 0.33 (0.66) | 0.14 (0.50) | 0.18 (0.43) | 0.23 (0.71) |

| Intimate Relationships and Sexual Activity | ||||

| All modafinil | 0.32 (0.63) | 0.46 (0.67) | 0.29 (0.64) | 0.52 (0.78) |

| Placebo | 0.30 (0.60) | 0.24 (0.56) | 0.17 (0.46) | 0.09 (0.84) |

Data are presented as mean (SD), as determined by Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores (ESS). FOSQ refers to Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

DISCUSSION

This secondary analysis of data pooled from previously reported studies of patients with excessive sleepiness associated with OSA,27–29 showed that modafinil improved patient functioning, as assessed by the FOSQ, and was consistent with results from the individual studies. This manuscript extends previous work by utilizing a large multisite cohort to examine the reduction in residual sleepiness following treatment with modafinil compared with placebo in those who are adherent users of CPAP treatment. Further, this paper provides the first responder analyses, providing specific cutpoints for improvement following treatment and demonstration of the extent and global response across specific functional areas when treated with modafinil, compared with placebo.

The functional improvements observed in this analysis of the combined double-blind, placebo-controlled OSA studies (n = 446) reflect the previous findings of the individual studies, in which significant improvements for patients who received modafinil were seen in Total score and in the individual domains of Activity Level and Vigilance (in both of the studies)30, 31 and General Productivity (in 1 of the studies).30 Additionally, in a 12-week, open-label, study extension of the 4-week double-blind study, patients maintained these improvements in sleep-related functional status, with additional significant improvement in Total score and in each of the 5 FOSQ domains of everyday living.40 Collectively, the findings of these studies differ from a small, 4-week, crossover study of 30 patients with excessive sleepiness associated with OSA despite CPAP therapy that found no significant improvement in FOSQ-assessed quality of life following modafinil use.41 The small sample size, with presumed lack of power, may account for the differences between findings from this study and our study, as well as from previous reports of the benefits of modafinil on daily functioning.

Patients' subjective sleepiness, as measured by the ESS, has been associated with quality-of-life outcomes in a number of studies.38, 42 In a previous study of patients with OSA, FOSQ scores showed a significant correlation with ESS scores.14, 43 Among the patients with OSA included in the current analysis, the severity of baseline subjective sleepiness, as measured by the ESS, was found to predict daytime functional outcomes; however, it was not significantly related to improvement on the FOSQ at the final visit in patients who received modafinil. That is, regardless of subjective severity of sleepiness at baseline, modafinil improved Total and domain scores, compared with placebo.

The current analysis highlights both the significant level of excessive sleepiness and its substantial negative impact on the daily functioning and quality of life of patients with OSA. Results of our secondary analysis of data pooled from previous double-blind studies confirm that modafinil improves functional outcomes in patients with residual excessive sleepiness despite adequate CPAP therapy. The improvement in FOSQ domains following administration of modafinil, particularly the domains of activity level and vigilance, are likely the result of the ability of the drug to improve wakefulness. The results are consistent with the modafinil-related improvements in objective and subjective measures of sleepiness, patients' overall clinical condition, and patients' ability to sustain attention demonstrated in the previous double-blind studies.29–31 In patients with OSA and residual excessive sleepiness despite regular CPAP use, modafinil treatment was associated with improvements in patients' functional outcomes, including activity, productivity, intimacy, and vigilance and in their ability to engage in a broad array of everyday activities, as confirmed through analysis of data pooled from studies lasting up to 12 weeks. Longer-term studies examining the impact of modafinil on sleep-related functional status would provide additional confirmation of the modafinil-related functional improvements in patients with OSA and residual excessive sleepiness.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Financial support for this secondary analysis was provided by Cephalon, Inc. The original studies were sponsored by Cephalon, Inc. The statistical analyses were performed by Cephalon, Inc. Dr. Weaver has received research support from and participated in a symposium sponsored by Cephalon. The other authors have indicated no other financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Graphics were constructed by BioScience Communications, Inc., New York, NY.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research. (National Academy of Sciences) Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tasali E, Mokhlesi B, Van Cauter E. Obstructive sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes: interacting epidemics. Chest. 2008;133:496–506. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1217–39. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young T, Peppard P, Palta M, et al. Population-based study of sleep-disordered breathing as a risk factor for hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1746–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365:1046–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sateia MJ. Neuropsychological impairment and quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24:249–59. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(03)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nowak M, Kornhuber J, Meyrer R. Daytime impairment and neurodegeneration in OSAS. Sleep. 2006;29:1521–30. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munoz A, Mayoralas LR, Barbe F, Pericas J, Agusti AG. Long-term effects of CPAP on daytime functioning in patients with sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:676–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15d09.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindberg E, Berne C, Elmasry A, Hedner J, Janson C. CPAP treatment of a population-based sample--what are the benefits and the treatment compliance? Sleep Med. 2006;7:553–60. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30:711–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teran-Santos J, Jimenez-Gomez A, Cordero-Guevara J. The association between sleep apnea and the risk of traffic accidents. Cooperative Group Burgos-Santander. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:847–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindberg E, Carter N, Gislason T, Janson C. Role of snoring and daytime sleepiness in occupational accidents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2031–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.11.2102028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulfberg J, Carter N, Edling C. Sleep-disordered breathing and occupational accidents. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:237–42. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellen RL, Marshall SC, Palayew M, Molnar FJ, Wilson KG, Man-Son-Hing M. Systematic review of motor vehicle crash risk in persons with sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George CF. Sleep apnea, alertness, and motor vehicle crashes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:954–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-629PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gay P, Weaver T, Loube D, Iber C. Evaluation of positive airway pressure treatment for sleep related breathing disorders in adults. Sleep. 2006;29:381–401. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faccenda JF, Mackay TW, Boon NA, Douglas NJ. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in the sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:344–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2005037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giles TL, Lasserson TJ, Smith BH, White J, Wright J, Cates CJ. Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD001106. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001106.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall NS, Barnes M, Travier N, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure reduces daytime sleepiness in mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnoea: a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2006;61:430–4. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.050583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkinson C, Davies RJO, Mullins R, Stradling JR. Comparison of therapeutic and subtherapeutic nasal continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomised prospective parallel trial. The Lancet. 1999;353:2100–05. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hack M, Davies RJ, Mullins R, et al. Randomised prospective parallel trial of therapeutic versus subtherapeutic nasal continuous positive airway pressure on simulated steering performance in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax. 2000;55:224–31. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.3.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMahon JP, Foresman BH, Chisholm RC. The influence of CPAP on the neurobehavioral performance of patients with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome: a systematic review. Wis Med J. 2003;102:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black J. Sleepiness and residual sleepiness in adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;136:211–20. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santamaria J, Iranzo A, Ma Montserrat J, de Pablo J. Persistent sleepiness in CPAP treated obstructive sleep apnea patients: evaluation and treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pack AI, Black JE, Schwartz JR, Matheson JK. Modafinil as adjunct therapy for daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1675–81. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2103032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black JE, Hirshkowitz M. Modafinil for treatment of residual excessive sleepiness in nasal continuous positive airway pressure-treated obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Sleep. 2005;28:464–71. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinges DF, Weaver TE. Effects of modafinil on sustained attention performance and quality of life in OSA patients with residual sleepiness while being treated with nCPAP. Sleep Med. 2003;4:393–402. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin JS, Hou Y, Jouvet M. Potential brain neuronal targets for amphetamine-, methylphenidate-, and modafinil-induced wakefulness, evidenced by c-fos immunocytochemistry in the cat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14128–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saper CB, Scammell TE. Modafinil: a drug in search of a mechanism. Sleep. 2004;27:11–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myrick H, Malcolm R, Taylor B, LaRowe S. Modafinil: preclinical, clinical, and post-marketing surveillance--a review of abuse liability issues. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16:101–9. doi: 10.1080/10401230490453743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weaver TE, Laizner AM, Evans LK, et al. An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep. 1997;20:835–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitler MM, Gujavarty KS, Browman CP. Maintenance of wakefulness test: a polysomnographic technique for evaluation treatment efficacy in patients with excessive somnolence. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1982;53:658–61. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(82)90142-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johns MW. Sensitivity and specificity of the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT), the maintenance of wakefulness test and the epworth sleepiness scale: failure of the MSLT as a gold standard. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:5–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guy W. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs. Clinical Global Impressions. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz JR, Hirshkowitz M, Erman MK, Schmidt-Nowara W. Modafinil as adjunct therapy for daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea: a 12-week, open-label study. Chest. 2003;124:2192–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kingshott RN, Vennelle M, Coleman EL, Engleman HM, Mackay TW, Douglas NJ. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial of modafinil in the treatment of residual excessive daytime sleepiness in the sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:918–23. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.2005036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beusterien KM, Rogers AE, Walsleben JA, et al. Health-related quality of life effects of modafinil for treatment of narcolepsy. Sleep. 1999;22:757–65. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrer M, Vilagut G, Monasterio C, Montserrat JM, Mayos M, Alonso J. Measurement of the perceived impact of sleep problems: the Spanish version of the functional outcomes sleep questionnaire and the Epworth sleepiness scale. Med Clin (Barc) 1999;113:250–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]