Abstract

The active movement of cells from subendothelial compartments into the bloodstream (intravasation) has been recognized for several decades by histologic and physiologic studies, yet the molecular effectors of this process are relatively uncharacterized. For extravasation, studies based predominantly on static transwell assays support a general model, whereby transendothelial migration (TEM) occurs via chemoattraction toward increasing chemokine concentrations. However, this model of chemotaxis cannot readily reconcile how chemokines influence intravasation, as shear forces of blood flow would likely abrogate luminal chemokine gradient(s). Thus, to analyze how T cells integrate perivascular chemokine signals under physiologic flow, we developed a novel transwell-based flow chamber allowing for real-time modulation of chemokine levels above (luminal/apical compartment) and below (abluminal/subendothelial compartment) HUVEC monolayers. We routinely observed human T cell TEM across HUVEC monolayers with the combination of luminal CXCL12 and abluminal CCL5. With increasing concentrations of CXCL12 in the luminal compartment, transmigrated T cells did not undergo retrograde transendothelial migration (retro-TEM). However, when exposed to abluminal CXCL12, transmigrated T cells underwent striking retro-TEM and re-entered the flow stream. This CXCL12 fugetactic (chemorepellant) effect was concentration-dependent, augmented by apical flow, blocked by antibodies to integrins, and reduced by AMD3100 in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, CXCL12-induced retro-TEM was inhibited by PI3K antagonism and cAMP agonism. These findings broaden our understanding of chemokine biology and support a novel paradigm by which temporospatial modulations in subendothelial chemokine display drive cell migration from interstitial compartments into the bloodstream.

Keywords: chemotaxis, fugetaxis, intravasation, CXCL12, transendothelial migration, shear stress, fluid shear

Introduction

The discovery of chemokines has yielded a substantial understanding of the process(es) governing leukocyte migration. Derived mostly from results of Boyden chamber studies—in which cell migration, through a membrane or endothelial barrier, is measured in response to chemokines placed in the lower well of a transwell—a multistep cascade model has emerged, whereby cells emigrating from the bloodstream adhere to vascular endothelium and then transmigrate following a path of increasing concentrations of chemokines [1,2,3]. Although this model has been validated experimentally as an accurate description of molecular events in diapedesis and has become the paradigm for cell migration in general, it does not explain how cells can exit tissues to enter the circulation. Indeed, although the movement of cells from the subendothelial compartment into the blood-flow stream has been recognized for several decades by physiologic studies [4,5,6,7] and by histologic analysis [8, 9], little is known about the molecular effectors mediating this process. A greater understanding of chemokine traffic signals at the endothelial interface is of paramount importance in elucidating cell navigation patterns in host defense, as well as in the export of mature thymocytes from the thymus, in “mobilization” of hematopoietic stem cells from the marrow and in hematogenous metastasis of solid malignancies.

In general, the study of cell migration from subendothelial compartments into the bloodstream has been hindered by the lack of assay systems that recapitulate the physiology of the endothelial interface. Although it is used widely for assessing chemotactic responses, the Boyden chamber assay system does not mirror physiologic events in cell migration. Importantly, chemokine signals that govern extravasation are not delivered under the static conditions used in Boyden chambers but occur physiologically under conditions of hemodynamic shear stress. Moreover, Boyden chamber assays can only assess chemotactic response(s) to subendothelial chemokines. Recent studies showing that CXCL12 (stromal cell-derived factor 1) can be displayed on the endothelial surface in association with heparan sulfate [10], that endothelial cells store and secrete chemokines [11], and that platelets can deposit CXCL12 dynamically [12] have heightened interest in defining how luminal and abluminal chemokine presentations regulate cellular migration at the endothelial interface.

We and others [13,14,15] have analyzed chemokine effects on leukocyte transmigration in parallel plate-based flow chamber systems under simulated blood-flow conditions. Such studies have exposed a paradox in chemokine function that was unanticipated based on results from Boyden chamber studies: TEM can be triggered by chemokines presented solely on the apical surface of the endothelium. More specifically, using a novel TEMC, which allows a more physiologically relevant presentation of chemokines above and below the endothelium, we observed that display of the chemokine CXCL12 on the apical endothelium alone under hemodynamic shear conditions was sufficient to drive TEM of T cells in the absence of subendothelial chemokine deposits [15]. These data suggested that CXCL12 could act as a chemorepellant, effectively driving leukocytes away from a “chemoattractant.”

To better define the role of perivascular chemokines in regulating leukocyte TEM under physiologic flow conditions, we further modified the chamber to allow dynamic changes in subendothelial chemokine levels. In this study, we investigated the effects of altering subendothelial CXCL12 concentrations on human T cell retention following transmigration. Our data show that CXCL12 effects on T cell movement under hemodynamic flow conditions are dose-dependent and defined temporally, favoring chemoattraction (chemotaxis) or chemorepulsion (fugetaxis), resulting in bidirectional movement of T cells across the endothelial barrier depending on the spatial concentration of the chemokine and the kinetics of its presentation. These results provide the first evidence that transmigrating T cells can integrate multiple chemokine signals at the endothelial interface and reverse their coordinate trajectory. Our findings thus suggest a “reverse multistep model”, whereby dynamic temporospatial alterations in chemokine gradients can mediate cellular trafficking between extravascular and vascular compartments and unveil a role, unappreciated previously, for chemokine-mediated chemorepulsion as an effector of this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents

Human fibronectin, PE-conjugated anti-CD3 mAb (SK7, mouse IgG1), APC-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb (RPA-T4, mouse IgG1), FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 mAb (RPA-T8, mouse IgG1), FITC-conjugated anti-human CCR5 mAb (2D7, mouse IgG2a), and APC-conjugated anti-human CXCR4 mAb (12G5, mouse IgG2a) were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). TNF-α and anti-human CD49d mAb (2B4, a VLA-4 function-blocking mouse IgG1) were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Murine anti-human CD11a mAb (TS1/22, a LFA-1 function-blocking IgG1) was obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Recombinant human chemokines CXCL12 and CCL5 were obtained from Fitzgerald Industries International (Concord, MA, USA) and EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA), respectively. AMD3100, wortmannin, 8-Br-cAMP, and 8-Br-cGMP were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Blood was obtained from healthy volunteers after informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and under a protocol approved by the institutional review board of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Partners Human Research Committee, Boston, MA, USA).

Cell isolation and culture

CD3+, CD3+CD4+, and CD3+CD8+ T cells were isolated by negative selection from citrated whole peripheral blood using RosetteSep human T cell, human CD4+ T cell, and human CD8+ T cell enrichment cocktails, respectively (StemCell, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and gradient centrifugation over Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich) under pathogen-free conditions. Isolated cells were then maintained in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% FBS (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) and 100 U/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) for 24 h as described [15]. HUVECs, isolated as described [16], were obtained from the Vascular Biology Core Facility of the Department of Pathology of Brigham and Women’s Hospital. HUVECs were cultured in Medium 199 (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ, USA), supplemented with 20% FBS (Mediatech), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml heparin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 50 μg/ml endothelial cell growth supplement (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA, USA).

Flow cytometry (FACS) analysis

After 24 h of culture, CD3+, CD3+CD4+, and CD3+CD8+ T cells (from isolation described above) were washed with PBS (pH 7.4), pelleted by centrifugation at 855 RCF for 3 min, and resuspended at 107/ml in PBS (pH 7.4). Aliquots of 106 cells were double-stained with FITC anti-CCR5/APC anti-CXCR4 or triple-stained with PE anti-CD3/APC anti-CD4/FITC anti-CD8 at 4°C. After incubation for 30 min in the dark, cells were washed in PBS (pH 7.4), centrifuged at 855 RCF for 3 min, and resuspended in 200 μL PBS (pH 7.4). Chemokine receptor and CD receptor expressions were monitored by a FC500 MPL flow cytometer with MXP acquisition software and analyzed with CXP analysis software (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) in a gate corresponding to lymphocytes, as defined by the size and granularity parameters.

Real-time TEM analysis in a transwell flow chamber

In our previous report, we configured an acrylic flow chamber (called the “TEMC”) to hold a transwell insert on which an endothelial monolayer was cultured, creating an apical compartment and a subendothelial compartment [15]. For this study, the TEMC was modified to include access ports to the subendothelial compartment of the chamber, thus allowing dynamic, real-time changes to chemokine concentrations in the subendothelium (see Fig. 1A). HUVECs (Passage 2 or 3) were plated at 50% confluence onto the underside of transwell inserts (transwell-clear, 0.4 μm pores, Corning, Corning, NY, USA), which had been coated with 20 μg/ml fibronectin and were then grown to complete confluence over 48 h. Confluent HUVECs were stimulated for 6 h with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) to up-regulate expression of cell adhesion molecules mediating leukocyte transmigration. HUVEC-transwell inserts were then placed into the flow chamber and mounted on the stage of an overhead phase-contrast microscope (Eclipse E-600, Nikon, Japan) connected to a digital signal processing charged coupled device camera (ELMO Manufacturing Corp., Japan). The insert was then rinsed and filled with TEM medium (HBSS with 1 mM calcium chloride, 1 mM magnesium chloride, 5 mM HEPES, and 1 mg/ml BSA) alone or TEM medium containing 100 ng/ml CCL5 as the initial subendothelial chemokine component. For apical chemokine presentation, the HUVEC-coated side of the inserts was overlaid with CXCL12 at 10 ng/ml for 5 min and was then washed extensively before T cell perfusion at defined shear stress via flow generated by a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA).

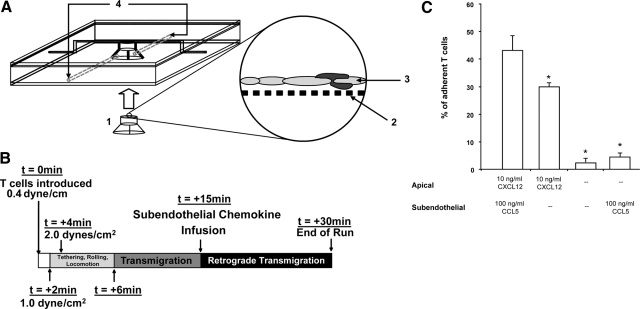

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the modified TEMC and TEM in the presence or absence of chemokine. (A) The TEMC, which consists of a central acrylic block with a central opening to fit a transwell [1] containing a cell impermeable membrane with 0.4 μm pore [2], on which a HUVEC monolayer [3] has been generated. The chamber is secured with two thin sheets of acrylic. To maintain a watertight seal, two sheets of rubber are sandwiched between each acrylic piece. A groove is made in the upper rubber sheet to create a lane running over the endothelial monolayer. The modifications to the chamber are the additions of two ports [4], leading to the subendothelial compartment of the chamber. (B) Timeline for experiments. At t = 0 min, T cells were introduced into the chamber at a flow rate of 0.4 dyne/cm2 and were exposed to a gradient consisting of apical 10 ng/ml CXCL12 and subendothelial 100 ng/ml CCL5. At t = 2 min, shear stress was increased to 1.0 dyne/cm2. At t = 4 min, shear stress was increased again to 2.0 dynes/cm2 and was maintained subsequently. Between t = 4 min and 10 min, T cells locomoted upon endothelial surface and underwent TEM. Where relevant (i.e., introduction of subendothelial chemokine), the volume in the subendothelial compartment was exchanged at t = 15 min; retro-TEM typically commenced within 1 min after chemokine exchange. Assays were terminated at t = 30 min. (C) Forward TEM with the presence of CXCL12 on the endothelial surface. Assays were initiated with 10 ng/ml CXCL12 apically and 100 ng/ml subendothelial CCL5 or with 10 ng/ml CXCL12 on the apical surface alone. The percentage of endothelial-adherent T cells undergoing forward TEM was assessed within 15 min. Data are means ± sem of at least four experiments. *, P < 0.0002, in comparison, to group with 10 ng/ml apical CXCCL12 and 100 ng/ml subendothelial CCL5; Student’s t-test.

For all experiments, T cells were perfused in TEM medium into the apical chamber at a density of 4 × 106 cells/ml and allowed to settle over the HUVEC monolayer while under flow at 0.4 dyne/cm2 for 2 min. Shear stress was then adjusted to 1.0 dyne/cm2 for 2 min to allow lymphocyte accumulation on the monolayer. Thereafter, shear stress was increased to 2.0 dynes/cm2, a physiologically relevant level shown to support TEM (see Fig. 1B). All experiments were performed at 37°C and video-recorded (HS-U748 video recorder, Mitsubishi Digital Electronics America, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) for subsequent off-line analysis.

Classification of cellular motion in the transwell flow chamber

“Detachment” was defined for T cells that made rolling or brief stationary contact with the endothelial surface and then were released during the period of observation. “Firm adhesion” was defined for T cells that were arrested on the endothelium for the duration of the assay. “Locomotion” was defined for T cells that exhibited morphological changes and displayed motility across the endothelial surface, notably in directions deviating from the direction of flow. TEM was defined for T cells that made rolling contact, adhered to the endothelium, underwent locomotion, and subsequently transmigrated through the endothelium. “retro-TEM” was defined for transmigrated T cells, which upon subendothelial chemokine substitution, remained stationary briefly or exhibited locomotion below the endothelial layer and then transmigrated to the apical compartment (surface of the endothelium).

TEM and retro-TEM were measured through off-line analysis of the video recordings of real-time events in each trial. For TEM, rolling T cells were categorized as detaching from the endothelial monolayer, remaining stationary during the entire period of visualization (i.e., showing firm adherence), and locomoting from the site of initial (transient) stationary attachment with subsequent TEM. Transmigrated cells were identified further as remaining stationary underneath the endothelial barrier or undergoing subsequent retro-TEM upon fresh subendothelial chemokine infusion. Only transmigrated T cells that were present beneath the endothelium before subendothelial chemokine infusion were examined for retro-TEM. In addition, only T cells completely visible in the field of view throughout the entire trial were analyzed. Immediately upon completion of retro-TEM, T cells displayed spherical morphology similar to that of arrested T cells on the endothelial surface that did not undergo initial locomotion or TEM; thereafter, T cells typically underwent locomotion on the endothelial surface or became detached and entered the flow stream (exiting the field of vision). Rarely (<5% of retro-TEM cells), the T cells would engage in locomotion and undergo TEM, usually at a different location on the endothelial monolayer.

Analysis of effects of increasing concentrations of subendothelial CXCL12 on the retention of transmigrated T cells

Transmigration of T cells under the induction of 10 ng/ml apical CXCL12 combined with 100 ng/ml subendothelial CCL5 was observed for 15 min (see Fig. 1B). Thereafter, the medium in the subendothelial compartment was removed immediately and replaced with media containing varying concentrations of CXCL12 (10 ng/ml, 25 ng/ml, 50 ng/ml, 75 ng/ml, 100 ng/ml, or 1 μg/ml). For replacement of subendothelial chemokine, the initial volume contained in the subendothelial compartment was removed. The subendothelial compartment was flushed twice gently with media containing no chemokine. Thereafter, media containing the relevant concentration of CXCL12 were injected into the subendothelial chamber for over 15 s. In each case, all subendothelial compartment manipulations were completed within 1 min without interruption of flow, and shear stress in the apical compartment was maintained constant at 2.0 dynes/cm2. Throughout all experiments, a video recording was maintained during the period of chemokine replacement and then continued for the remaining 15 min.

Analysis of rapid flux of luminal CXCL12 concentration on subendothelial T cells

Transmigration of T cells under the induction of 10 ng/ml apical CXCL12 combined with 100 ng/ml subendothelial CCL5 was observed for 10 min. Afterward, flow was stopped, and CXCL12 was injected into the luminal compartment at the final concentration of 100 ng/ml or 250 ng/ml. After 5 min of incubation, flow was resumed immediately at 2.0 dynes/cm2. A video recording was maintained throughout the period of CXCL12 injection and incubation, and continued for the remaining 15 min.

CXCR4 signaling, integrin function, and intracellular signaling in retro-TEM

Experimental assays were initiated with apical 10 ng/ml CXCL12 and subendothelial 100 ng/ml CCL5. At t = 10 min, AMD3100 (final concentration of 2 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml), anti-CD49d mAb (final concentration of 20 μg/ml), anti-CD11a (final concentration of 20 μg/ml), wortmannin (final concentration 40 μM), or 8-Br-cAMP or 8-Br-cGMP (final concentrations 3 mM) was added to the subendothelial chamber. After 5 min of incubation, at t = 15 min, the medium in the subendothelial chamber was replaced with media containing 100 ng/ml CXCL12 alone. A video recording was maintained throughout the period of inhibitor incubation and chemokine replacement, and continued for the remaining 15 min.

Chamber sampling and measurement of the CXCL12 and CCL5 gradients

To measure the kinetics of the CXCL12 and the CCL5 gradients across the endothelial monolayer, sampling runs were conducted with initial apical 10 ng/ml CXCL12 and initial subendothelial 100 ng/ml CCL5. Sampling runs contained transwells with HUVEC monolayers and input T cells, and migratory events during sampling runs were not included in the analysis. To sample the medium at various time-points, syringes were attached to the apical port (not shown in device diagram) and subendothelial port. After removing dead volume, small aliquots of media were removed from the luminal and the abluminal compartments at 2, 5, 20, 16, 20, 25, and 30 min. CXCL12 or CCL5 concentrations were measured by ELISA (Quantikine, R&D Systems).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using a Student’s t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Real-time analysis of T cell migration in response to perivascular chemokine gradients

To allow real-time changes in subendothelial chemokine presentation, the original TEMC design was modified to include subendothelial port access (Fig. 1A). Using this new chamber, we first analyzed the extent of T cell TEM using experimental conditions reported previously [15]. Viewed under real-time with video microscopy and recording for off-line analysis, human T cell transmigration was examined using 10 ng/ml CXCL12 presented alone on the apical surface or apical 10 ng/ml CXCL12 combined with 100 ng/ml CCL5 in the subendothelial compartment. By flow cytometry, the expressions of CXCR4 and CCR5 on isolated peripheral T cells were 97.7% ± 1.1% and 29.0% ± 4.2%, respectively, and 26.6% ± 4.2% of T cells expresses both chemokine receptors.

Similar to previous results using the original TEMC without subendothelial port access [15], reproducible T cell tethering and rolling, conversion to transient arrest, locomotion, and then TEM were observed. The efficiency and kinetics of T cell adhesion and transmigration did not differ from prior results (Fig. 1C) [15]. T cell locomotion on the HUVEC monolayer occurred within the first 2 min of initiating physiological shear stress of 2 dynes/cm2, and T cell transmigratory events were observed consistently within 6 min of physiologic shear stress (Fig. 1B). Consistent with our previous results, we observed that 43.0% ± 9.9% of adherent T cells underwent TEM within 6 min of initiating physiologic shear stress using the combination of apical 10 ng/ml CXCL12 and subendothelial 100 ng/ml CCL5; although more transmigration was observed with this combination of chemokines, apical presentation of 10 ng/ml CXCL12 alone was sufficient to drive TEM (29.6% ± 1.4% of adherent T cells; Fig. 1C). Also, consistent with our previous findings, minimal transmigration of adherent T cells was observed in the absence of initial CXCL12 on the apical surface, regardless of the presentation of subendothelial CCL5 (Fig. 1C).

The finding that apical presentation of CXCL12 alone cues T cells to undergo TEM prompted us to investigate the effects of dynamic changes in subendothelial CXCL12 presentation on transmigrated T cells. Accordingly, we altered the subendothelial chemokine gradient post-TEM with the introduction of varying concentrations of CXCL12 to the subendothelial chamber. With removal of CCL5 and exposure to ≥10 ng/ml CXCL12 within the subendothelial compartment, transmigrated T cells strikingly reversed direction, retro-migrating to the apical side of the HUVEC monolayer within 1–4 min of CXCL12 exposure (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Movies). Following retro-TEM, T cells underwent locomotion on the endothelial surface with subsequent detachment and re-entry into the flow stream. The extent of retro-TEM varied with subendothelial CXCL12 concentration, showing a twofold increase between 10 ng/ml and 100 ng/ml (P = 0.0023) with an apparent plateau at 100 ng/ml, as there were only slight increases in retro-TEM events with 250 ng/ml, 500 ng/ml, and 1 μg/ml CXCL12 concentration (Fig. 2A). Addition of medium alone to the subendothelial compartment did not induce retro-TEM (Fig. 2A), indicating that this process was not a result of changes in CCL5 levels alone, apical shear forces in the absence of subendothelial chemokine, and/or pressure fluctuations created from the infusion of liquid into the subendothelial compartment itself. Notably, whereas administration of CXCL12 in the subendothelial compartment induced retro-TEM, administration of CXCL12 at concentrations of 100 ng/ml or 250 ng/ml in the apical compartment did not induce transmigrated T cells to undergo retro-TEM (data not shown). The observed retro-TEM induced by subendothelial CXCL12 was blocked significantly with the addition of function-blocking anti-CD11a mAb (compared with isotype mAb, 1.5% ± 0.6% of adherent T cells underwent retro-TEM) and with anti-CD49d mAb (compared with isotype mAb, 2.5% ± 0.5% of adherent T cells underwent retro-TEM). These mAb to LFA-1 and VLA-4 were shown previously to block forward transmigration in the TEMC system [15]. Collectively, our results show a dose- and integrin-dependent effect of CXCL12 to induce cellular emigration away from the subendothelium and into the luminal flow stream.

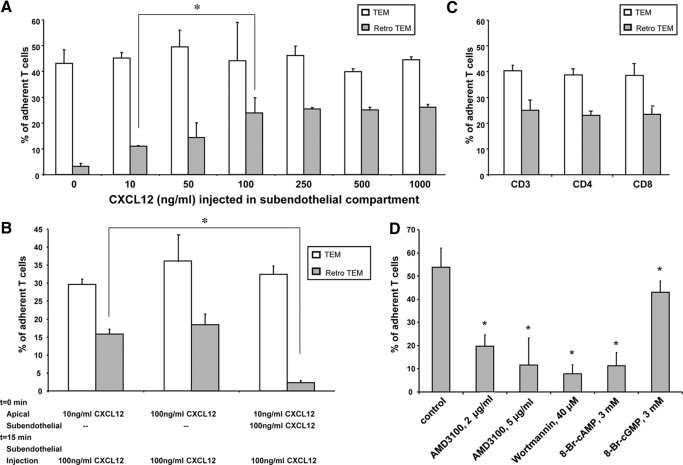

Figure 2.

Retro-TEM in response to infusion of CXCL12 in subendothelial compartment. (A) Retro-TEM under increasing concentrations of CXCL12. All assays were initiated with 10 ng/ml CXCL12 apically and 100 ng/ml subendothelial CCL5. The percentage of endothelial-adherent T cells undergoing TEM (open bars) was assessed within 15 min. Thereafter, the subendothelial compartment was flushed and injected with increasing concentrations of CXCL12 (shown on the x-axis), and subsequent retro-TEM (shaded bars) was determined. Data are mean ± sem of at least three experiments. *, P = 0.0023, for comparison, as shown by bracket; Student’s t-test. (B) Transmigration and retro-TEM under CXCL12 gradients. Assays were initiated with 10 ng/ml apical CXCL12 and 100 ng/ml subendothelial CXCL12 or with 10 ng/ml apical CXCL12 alone. The percentage of endothelial-adherent T cells undergoing TEM (open bars) was assessed within 15 min. Thereafter, the subendothelial compartment was flushed and injected with 100 ng/ml CXCL12, and retro-TEM (shaded bars) was then determined. Data are mean ± sem of at least three experiments. *, P = 0.0001, for comparison, as shown by bracket; Student’s t-test. (C) Transmigration and retro-TEM of T cell subsets. All assays were initiated with 10 ng/ml apical CXCL12 and 100 ng/ml subendothelial CCL5. Isolated total CD3, CD4, or CD8 T cells were used as the input cells (shown on the x-axis). The percentage of endothelial-adherent T cells undergoing TEM (open bars) was assessed within 15 min. Thereafter, the subendothelial compartment was flushed and injected with 100 ng/ml CXCL12, and subsequent retro-TEM (shaded bars) was determined. Data are mean ± sem of at least three experiments. (D) Inhibition of retro-TEM. Assays were initiated with 10 ng/ml CXCL12 in the apical compartment and 100 ng/ml CCL5 in the subendothelial compartment. At t = 13 min, AMD3100 (2 μg or 5 μg/ml), wortmannin (40 μM), or 8-Br-cAMP (3 mM) or 8-Br-cGMP (3 mM) was injected into the subendothelial compartment under continuous fluid shear in the apical compartment. At t = 15 min, the subendothelial chamber was flushed and replaced with medium containing 100 ng/ml CXCL12. The percentage of transmigrated T cells that underwent retro-TEM was then determined. Data are mean ± sem of at least three experiments. *, P < 0.01, in comparison to control group; Student’s t-test.

To further define the temporospatial effects of subendothelial CXCL12 presentation on T cell TEM and retro-TEM, we tested the effects of 10 ng/ml apical CXCL12 on T cell transmigration, with and without initial subendothelial 100 ng/ml CXCL12. In contrast to the observed chemorepellent effect from sudden subendothelial exposure of CXCL12, T cells underwent robust TEM when exposed initially to 100 ng/ml CXCL12 in the subendothelial compartment (Fig. 2B). Notably, replacement of initial subendothelial 100 ng/ml CXCL12 with (fresh) 100 ng/ml CXCL12 at 15 min did not induce retro-TEM. However, where there had been no prior subendothelial CXCL12 (e.g., 10 ng/ml apical presentation alone), the addition of 100 ng/ml CXCL12 into the subendothelial chamber at 15 min of the experimental run induced subendothelial T cells to undergo striking retro-TEM (Fig. 2B). Altogether, these findings indicate that acute temporal and spatial changes in expression of a given chemokine across an endothelial barrier can yield competing attractant and repellant actions on transmigrating T cells.

Retro-TEM of T cell subsets

To determine whether the observed retro-TEM is specific to a subset of circulating peripheral T cells, parallel studies were performed using total CD3 cells and CD4 and CD8 subsets, isolated by negative selection from peripheral blood, allowing for >95% purity of respective CD receptor expressions (data not shown). Notably, although flow cytometry showed that the three isolated cell populations displayed similar levels of CXCR4 expression, CD4 cells displayed a lower level, and CD8 cells displayed a higher level of CCR5 expression compared with that of (total) CD3 cells—CD4: 96.9% ± 1.9% CXCR4+, 23.0% ± 7.2% CCR5+, 20.8% ± 5.0% double-positive; CD8: 94.7% ± 5.9% CXCR4+, 36.3% ± 3.5% CCR5+, 33.3% ± 2.5% double-positive. Nonetheless, the induction of forward TEM with an initial combination apical 10 ng/ml CXCL12 and subendothelial 100 ng/ml CCL5 did not differ between CD4 and CD8 cells (39.0% ± 1.8% and 38.8% ± 2.3% of adherent cells, respectively) and was comparable with the forward TEM induction of isolated pan-T cells (Fig. 2C, open bars). Upon precipitous changes in subendothelial chemokine presentation from 100 ng/ml CCL5 to 100 ng/ml CXCL12, transmigrated cells from CD4 and CD8 subsets underwent retro-TEM of a similar scale to that of CD3 cells (CD4: 23.2% ± 1.2%, CD8: 23.6% ± 2.2%, CD3: 25.3% ± 4.1% of adherent cells; Fig. 2C, shaded bars). The similarity in these physiological findings was consistent with the similar expression patterns of CXCR4 on the three isolated T cell populations.

AMD3100, wortmannin, and 8-Br-cAMP inhibit retro-TEM

To evaluate more specifically the role of CXCL12 in observed retro-TEM, we inhibited the CXCL12 receptor, CXCR4, using the antagonist AMD3100 [17, 18]. Following a standard experimental run using apical 10 ng/ml CXCL12 and subendothelial 100 ng/ml CCL5, we exposed transmigrated T cells to varying concentrations of AMD3100 5 min before infusion of 100 ng/ml CXCL12 into the subendothelial compartment. The percentage of subendothelial cells that underwent retro-TEM was reduced 2.7-fold with 2 μg/ml AMD3100 pretreatment (P <0.0001) and inhibited 4.6-fold with 5 μg/ml of the antagonist (P <0.0001; Fig. 2D). These data provide direct evidence that engagement of CXCR4 mediates retro-TEM.

Continuing further, we explored elements of the intracellular signaling pathway involved in retrograde transmigration including PI3Ks and intracytoplasmic cyclic nucleotides. After a standard run using apical 10 ng/ml CXCL12 and subendothelial 100 ng/ml CCL5, transmigrated T cells were exposed to wortmannin, 8-Br-cAMP, or 8-Br-cGMP, placed in the subendothelial compartment 5 min before presentation of 100 ng/ml CXCL12 into the subendothelial compartment. Although a little over one-half (53.8% ± 8.3) of the transmigrated subendothelial T cells underwent retro-TEM after being subjected to high concentrations of CXCL12 alone, preincubation of transmigrated T cells with 40 μM wortmannin, an inhibitor of PI3Ks, reduced the incidence of retro-TEM 6.8-fold (to 7.9% ± 3.8, P<0.0001; Fig. 2D). Similarly, preincubation with 3 mM 8-Br-cAMP, a cAMP analog, reduced retro-TEM 4.7-fold (to 11.4% ± 5.7, P<0.0001; Fig. 2D). However, preincubation with 3 mM 8-Br-cGMP, an analog of cGMP, reduced TEM modestly (to 43.1% ± 4.9, P<0.0001; Fig. 2D). Together, these data show that CXCL12-triggered retro-TEM is a PI3K-dependent process and is mediated by dampened intracellular cyclic nucleotide levels.

Defining the CXCL12 and CCL5 gradients across the HUVEC layer

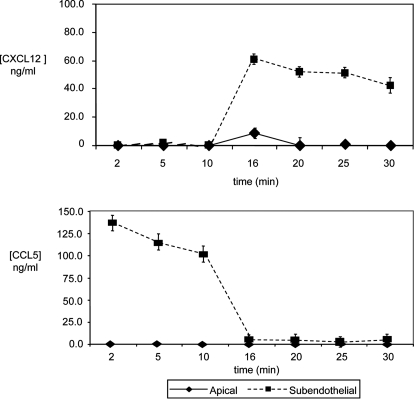

In view of the finding that retro-TEM of T cells varied with CXCL12 concentration in the subendothelial compartment, we sought to define the chemokine gradients of CXCL12 and CCL5 under fluid shear conditions that guided directional migration of T cells. Starting with initial concentrations of 10 ng/ml CXCL12 apically and 100 ng/ml subendothelial CCL5, runs were performed in a similar manner to previous experiments with changing of subendothelial chemokine at 15 min with 100 ng/ml CXCL12 (Fig. 1B). During the course of these experiments, samples from the flow stream (luminal) and subendothelial (abluminal) compartments were taken at various time-points described in the Materials and Methods. ELISA results revealed that within 1 min of changing the chemokines within the subendothelial chamber (i.e., with the introduction of CXCL12 at a concentration of 100 ng/ml at 15 min of experimentation), there was a dramatic increase in CXCL12 concentration abluminally (∼60 ng/ml) with only a modest rise (<10 ng/ml) of the CXCL12 concentration in the luminal compartment (Fig. 3A). This newly established, high abluminal CXLC12 concentration remained constant for the remaining 15 min, whereas the luminal CXCL12 concentration returned to baseline (0 ng/ml) rapidly (i.e., by t = 20 min). These ELISA results show directly that addition of CXCL12 to the subendothelium created a rather stable gradient, where CXCL12 concentrations were markedly higher abluminally compared with luminally. In contrast, as expected, CCL5 concentration gradients across the HUVEC monolayer showed a reciprocal temporal pattern to that of CXCL12. During the initial 15 min of T cell TEM, wherein CCL5 was presented subendothelially, CCL5 concentrations were high in the abluminal compartment and undetectable in the luminal compartment (Fig. 3A). After removal from the subendothelial compartment (at 15 min), CCL5 levels approached 0 ng/ml concentration and uniformly remained undetectable in the luminal and abluminal compartments through the final 15 min of the experimental run.

Figure 3.

CXCL12 and CCL5 concentrations in apical and subendothelial compartments in the presence of shear. Sampling runs were performed with 10 ng/ml CXCL12 and 100 ng/ml CCL5 at t = 0 min. From t = 0 min to 2 min, the shear force was 0.4 dyne/cm2. Shear stress was then adjusted to 1.0 dyne/cm2 for t = 2–4 min. Thereafter, shear stress was increased to and maintained at 2.0 dynes/cm2. At t = 15 min, the subendothelial compartment was flushed and replaced with medium containing 100 ng/ml CXCL12. Samples were obtained in the apical and subendothelial compartments at 2, 5, 10, 16, 20, 25, and 30 min and analyzed for levels of CXCL12 and CCL5 by ELISA. Data are mean ± sem of at least three experiments.

T cell retro-TEM is optimal under apical shear

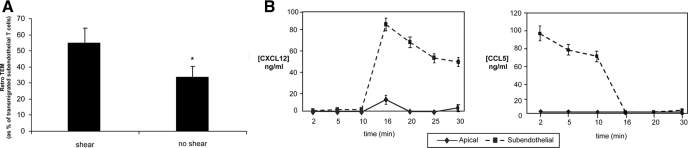

In prior studies, we found that (forward) TEM of T cells exposed to apical and subendothelial chemokines is markedly attenuated in the absence of shear [15]. To examine whether shear affects CXCL12-induced retro-TEM, we analyzed retro-TEM under static conditions, using identical apical CXCL12 and subendothelial CCL5 conditions as described above but with the flow stopped immediately after the infusion of subendothelial CXCL12 at 100 ng/ml. Fugetaxis-driven retro-TEM was also observed under static conditions (33.3% ± 6.2% of transmigrated subendothelial T cells) but was markedly less than that observed in the presence of shear (54.3% ± 10.9% of transmigrated subendothelial T cells; P = 0.019; Fig. 4A), despite the fact that the chemokine gradient patterns without shear were similar to the gradient patterns of experiments with shear (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Presence of shear increases the efficiency of retro-TEM. (A) Retrograde migration with or without shear. Assays were performed with initial 10 ng/ml apical CXCL12 and 100 ng/ml subendothelial CCL5. At t = 15 min, the subendothelial compartment was flushed and replaced with medium containing 100 ng/ml CXCL12. Flow was continued (shear) or stopped immediately (no shear), and the percentage of transmigrated subendothelial T cells that underwent retro-TEM was then determined. Data are mean ± sem of at least three experiments. *, P = 0.019, comparing TEM in the presence versus absence of shear; Student’s t-test. (B) CXCL12 and CCL5 concentrations in apical and subendothelial compartments in the absence of shear. Sampling runs were performed with 10 ng/ml CXCL12 and 100 ng/ml CCL5 at t = 0 min. Throughout the entirety of the runs, no shear stress was applied. At t = 15 min, the subendothelial compartment was flushed and replaced with medium containing 100 ng/ml CXCL12. Samples were obtained in apical and subendothelial compartments at 2, 5, 10, 16, 20, 25, and 30 min and analyzed for levels of CXCL12 and CCL5 by ELISA. Data are mean ± sem of at least three experiments.

DISCUSSION

The current multistep paradigm of cell migration holds that circulating cells undergo an ordered cascade of adhesive interactions coupled with biochemical signals, resulting ultimately in cellular emigration from blood to target tissue. In this model, cellular trajectory through the endothelium and into the tissue compartment and subsequent intraparenchymal localization of extravasated cells are driven by an increasing chemical gradient generated predominantly by chemokines, favoring cellular motion toward the encountered chemokine(s) [19, 20]. The data presented here compel a reassessment of the chemoattractant effects of chemokines implicit in this model: We show that competing attractant/repellant signals delivered by chemokines can trigger T cells to reverse direction after traversing the endothelium. Importantly, under physiologic flow conditions, our data show that T cells, which have transmigrated (extravasated) in response to chemotactic signals of a given chemokine (CCL5), undergo chemorepellent-driven reverse TEM (intravasation) when exposed to a newly encountered chemokine (CXCL12) in the subendothelial space. Our findings thus provide new insights about how temporal changes in three-dimensional chemokine presentation, integrin occupancy events, and shear-transduced mechanical signaling could drive a dynamic exchange of cells between vascular and extravascular compartments at the endothelial interface.

Although the intravasation of cells from the subendothelial compartment into the blood-flow stream is well-recognized [4,5,6,7,8,9, 21], there is essentially no information about how this process is initiated. The wide variety of chemokines identified to date has led to a generally held view that the navigational vector of migrating leukocytes reflects the integration of “orienting” chemoattractant signals delivered by these agents [20]. However, our results here show that exposure to subendothelial CXLC12 can induce recently immigrated T cells to flee the subendothelial compartment and return to the endothelial surface, with subsequent re-entry into the flow stream. Conversely, sudden increases in apical CXCL12 levels do not provoke recently transmigrated T cells to return to the apical surface. The observed fugetaxis-driven retro-TEM from subendothelial CXCL12 perturbation is mediated by engagement of integrins LFA-1 and VLA-4, as function-blocking mAb directed to CD11a and CD49d, respectively, were each inhibitory of retro-TEM. This process is dependent on the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis as seen by abrogation in the presence of AMD3100 and by the correlation of similar CXCR4 expression levels of isolated T cell subsets with similar levels of CXCL12-induced retro-TEM. In addition, retro-TEM was enhanced significantly by hemodynamic fluid shear. Furthermore, exposure of transmigrated T cells to wortmannin and to 8-Br-cAMP each blocked retro-TEM, indicating that this process is mediated by PI3K- and cAMP-dependent signaling cascades. The distinct inhibition profile of reverse TEM in response to an intracytoplasmic cAMP agonist is consistent with CXCL12 acting as a chemorepellent across the endothelial barrier, as prior studies have shown that elevated intracytoplasmic cAMP concentrations counteract CXCL12-mediated leukocyte and neuronal growth cone chemorepulsion [22,23,24,25].

Altogether, these results suggest a reverse multistep model, wherein: (Step 1) Discrete chemokine receptor occupancy in response to microenvironmental variations in abluminal chemokine(s) induces (Step 2) fugetactic integrin-, PI3K-, and cAMP-dependent adhesive interactions mediating (Step 3) cellular intravasation into the flow stream. Thus, in contrast to the extravasation multistep paradigm in which “Step 1” is mediated by engagement of shear-resistant adhesion molecules under hemodynamic conditions, and “Step 2” encompasses chemokine effects, our data suggest that the cascade of intravasation is initiated by chemokine signaling. Notably, retro-TEM was not observed upon sudden addition of CXCL12 in the subendothelium under conditions where T cells had undergone TEM initially in the presence of 10 ng/ml apical CXCL12 and 100 ng/ml CXCL12 in the subendothelial compartment (see Fig. 2B). These findings suggest that cells extravasating through an endothelial monolayer into an environment of high concentration of a given chemokine such as CXCL12 can become desensitized to the relevant chemokine. Thus, additional expression of CXCL12 cannot induce intravasation, in contrast to when a heterologous chemokine such as CCL5 is the subendothelial chemokine. These observations underscore the intricate biology of chemokine receptor engagement, revealing the complexity of not only the spatial but also the temporal and combinatorial patterns of local perivascular chemokine expression on directional transendothelial cell migration.

Our results indicate that hemodynamic shear stress across the apical endothelial surface promotes the retro-TEM induced by exposure of T cells to high concentrations of CXCL12 in the subendothelial compartment. The significantly augmented (twofold) retro-TEM observed in the presence of continuous apical fluid flow did not result from shear-induced differences in chemokine presentation, as there were no differences in the chemokine gradients established across apical and subendothelial compartments in the presence or the absence of shear (compare Figs. 3A and 4B). In the presence of fluid shear, recently immigrated subendothelial T cells may be “primed” structurally for transmigration: Our prior results [15] revealed a critical role for shear forces in supporting the elaboration of endothelial-probing podosome extensions from the T cell body, consistent with findings in other cells [26]. During retro-TEM, fluid shear could also provide orienting external forces, driving the elaboration of incipient podosome extensions, disrupting actin networks upstream [27], and polarizing focal adhesion complexes downstream [26]. Future studies using real-time, high-resolution microscopy should provide greater insight into the interplay between biophysics (hydrodynamics) and the morphology of podosome extensions.

Based on our dataset, we introduce the concept that rapid changes in chemokine levels in the subendothelium could mediate a volley of cells between vascular and extravascular compartments. In particular, our results suggest that dynamic elevation(s) in abluminal CXCL12 levels would prompt the emigration/intravasation of T cells at the perivascular interface. Relatively high concentrations of CXCL12 have been found in certain tissues such as bone marrow and thymus, far exceeding that found in the vasculature [22, 28, 29]. Importantly, T cells regularly exit these tissues, suggesting that this emigration could result from localized high levels of CXCL12 exerting chemorepellent effects [22, 28], and there is direct evidence that CXCR4 signaling contributes to fugetactic exit of mature T cells from the thymus [22, 28, 30]. Dynamic changes in abluminal CXCL12 levels could occur readily, such as with platelet activation within denuded endothelium [12]. In addition, treatment with the sulfated polysaccharide fucoidan rapidly displaces CXCL12 sequestered on heparan sulfate proteoglycans on endothelial cell surfaces [10] or on extracellular matrix within the bone marrow [31, 32]. These findings, together with evidence that endothelial cells secrete heparanase [33] and that heparanase releases heparan sulfate-bound CXCL12 [34], suggest that sudden increases in interstitial CXCL12 levels could occur natively. Furthermore, chemokines can be stored in specialized secretory granules in tissue resident cells (e.g., mast cells), in leukocytes (e.g., neutrophils), and in endothelial cells themselves [11], any or all of which could mobilize precipitously their stored contents and increase relevant chemokine levels in the perivascular interstitial space [35,36,37]. Fugetaxis effects may extend to chemokines other than CXCL12, and importantly, eotaxin-3, CXCR3 ligands, and IL-8 have each been shown to act as chemorepellents for human monocytes, dendritic cells, and neutrophils, respectively [25, 36, 38]. Notably, in addition to CXCL12, luminal display of CCL21 has been shown to mediate lymphocyte TEM via fugetaxis under flow conditions [39].

Collectively, our findings suggest that chemokine effects at the endothelial interface could reflect a complex tapestry, ranging from chemotaxis (chemoattraction) and fugetaxis (chemorepulsion), mediating cellular extravasation and intravasation. Viewed in this light, the endothelial interface would serve not as a one-way exit but rather as a dynamic bidirectional portal. Significant T cell infiltrates with a diverse TCR repertoire are found in perivascular areas of normal tissues, such as skin under resting conditions [40], indicating that there may be steady-state T cell cycling between blood and tissue at the endothelial interface. Thus, the canonical view that lymphocyte recirculation requires extravasation, afferent lymphatic vessel-mediated flow to lymphoid compartments, and subsequent efferent lymphatic vessel/thoracic duct drainage back into the vascular compartment may be restricted [41]. Dynamic shuttling at the endothelial interface could function in parallel to orchestrate lymphocyte reassortment and redistribution to and from vascular and interstitial compartments. As such, the capability of perivascular chemokine traffic signals to govern leukocyte intravasation and extravasation under hemodynamic flow conditions has important implications for regulation of host defense and inflammation. Indeed, in vivo time-lapse imaging of neutrophils in zebrafish has shown directed intravasation of extravascular cells after tissue injury, resulting in the resolution phase of the inflammatory responses [21]. Accordingly, the classical histopathologic finding of perivascular leukocytic infiltrates in target tissue(s) of inflammatory reactions could reflect a staging area for cell exchange between the vascular and parenchymal compartments. Dynamic forward/reverse gear-shifting in trafficking leukocytes induced by competing attractant and repellant abluminal chemokine navigation signals could help regulate site-specific immunity, mitigating collateral tissue damage, and could be exploited therapeutically to blunt effector T cell infiltration of allografts [42]. Furthermore, beyond implications in immunology and host defense, analysis of temporospatial chemokine effects at the endothelial interface involving other blood-borne cells such as hematopoietic stem cells and cancer cells could provide new mechanistic insights into the molecular basis of stem cell mobilization and cancer metastasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M. C. P. was supported by Public Health Service grant RO1 AI49757 and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. R. S. was supported by RO1 HL60528, RO1 HL73714, and RO1 CA121335. We thank Ron Yip and Dr. Elda Righi for their assistance with the CXCL12 and CCL5 ELISA assays.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 8-Br-cAMP/cGMP=8-bromo-cAMP/cGMP, APC=allophycocyanin, RCF=realized centrifugal force, retro-TEM=retrograde transendothelial migration, t=time, TEM=transendothelial migration, TEMC=transendothelial migration chamber

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

References

- Springer T A. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher E C. Specificity of leukocyte-endothelial interactions and diapedesis: physiologic and therapeutic implications of an active decision process. Res Immunol. 1993;144:695–698. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(93)80053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher E C. Leukocyte-endothelial cell recognition: three (or more) steps to specificity and diversity. Cell. 1991;67:1033–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernstrom U, Glyllensten L, Larsson B. Venous output of lymphocytes from the thymus. Nature. 1965;207:540–541. doi: 10.1038/207540b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J, Johnson R J, Mooney A, Hugo C, Gordon K, Savill J. Neutrophil fate in experimental glomerular capillary injury in the rat. Emigration exceeds in situ clearance by apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:223–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Itoi M, Tsukamoto N, Kubo H, Amagai T. The perivascular space as a path of hematopoietic progenitor cells and mature T cells between the blood circulation and the thymic parenchyma. Int Immunol. 2007;19:745–753. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condeelis J S, Wyckoff J, Segall J E. Imaging of cancer invasion and metastasis using green fluorescent protein. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1671–1680. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro I, Olah I. Penetration of thymocytes into the blood circulation. J Ultrastruct Res. 1967;17:439–451. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(67)80134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushiki T. A scanning electron-microscopic study of the rat thymus with special reference to cell types and migration of lymphocytes into the general circulation. Cell Tissue Res. 1986;244:285–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00219204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L, Salvucci O, Cardones A R, Hwang S T, Aoki Y, De La Luz Sierra M, Sajewicz A, Pittaluga S, Yarchoan R, Tosato G. Selective expression of stromal-derived factor-1 in the capillary vascular endothelium plays a role in Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis. Blood. 2003;102:3900–3905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oynebraten I, Bakke O, Brandtzaeg P, Johansen F E, Haraldsen G. Rapid chemokine secretion from endothelial cells originates from 2 distinct compartments. Blood. 2004;104:314–320. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellos K, Langer H, Daub K, Schoenberger T, Gauss A, Geisler T, Bigalke B, Mueller I, Schumm M, Schaefer I, Seizer P, Kraemer B F, Siegel-Axel D, May A E, Lindemann S, Gawaz M. Platelet-derived stromal cell-derived factor-1 regulates adhesion and promotes differentiation of human CD34+ cells to endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2008;117:206–215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.714691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinamon G, Shinder V, Alon R. Shear forces promote lymphocyte migration across vascular endothelium bearing apical chemokines. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:515–522. doi: 10.1038/88710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinamon G, Alon R. Real-time in vitro assay for studying chemoattractant-triggered leukocyte transendothelial migration under physiological flow conditions. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;239:233–242. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-435-2:233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber T H, Shinder V, Cain D W, Alon R, Sackstein R. Shear flow-dependent integration of apical and subendothelial chemokines in T-cell transmigration: implications for locomotion and the multistep paradigm. Blood. 2007;109:1381–1386. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-032995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe E A, Nachman R L, Becker C G, Minick C R. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:2745–2756. doi: 10.1172/JCI107470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donzella G A, Schols D, Lin S W, Este J A, Nagashima K A, Maddon P J, Allaway G P, Sakmar T P, Henson G, De Clercq E, Moore J P. AMD3100, a small molecule inhibitor of HIV-1 entry via the CXCR4 co-receptor. Nat Med. 1998;4:72–77. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schols D, Este J A, Henson G, De Clercq E. Bicyclams, a class of potent anti-HIV agents, are targeted at the HIV coreceptor fusin/CXCR-4. Antiviral Res. 1997;35:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(97)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxman E F, Campbell J J, Butcher E C. Multistep navigation and the combinatorial control of leukocyte chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1349–1360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxman E F, Kunkel E J, Butcher E C. Integrating conflicting chemotactic signals. The role of memory in leukocyte navigation. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:577–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias J R, Perrin B J, Liu T X, Kanki J, Look A T, Huttenlocher A. Resolution of inflammation by retrograde chemotaxis of neutrophils in transgenic zebrafish. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1281–1288. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznansky M C, Olszak I T, Foxall R, Evans R H, Luster A D, Scadden D T. Active movement of T cells away from a chemokine. Nat Med. 2000;6:543–548. doi: 10.1038/75022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M A, Beattie C E. Attraction versus repulsion: modular receptors make the difference in axon guidance. Cell. 1999;97:821–824. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80793-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Ming G, He Z, Lehmann M, McKerracher L, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo M. Conversion of neuronal growth cone responses from repulsion to attraction by cyclic nucleotides. Science. 1998;281:1515–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp W G, Yadav R, Irimia D, Upadhyaya A, Samadani A, Hurtado O, Liu S Y, Munisamy S, Brainard D M, Mahon M J, Nourshargh S, van Oudenaarden A, Toner M G, Poznansky M C. Neutrophil chemorepulsion in defined interleukin-8 gradients in vitro and in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:539–554. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0905516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Butler P, Wang Y, Hu Y, Han D C, Usami S, Guan J L, Chien S. The role of the dynamics of focal adhesion kinase in the mechanotaxis of endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3546–3551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052018099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnet S, Ananthakrishnan R, Mogilner A, Meister J J, Verkhovsky A B. Weak force stalls protrusion at the leading edge of the lamellipodium. Biophys J. 2006;90:1810–1820. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.064600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vianello F, Kraft P, Mok Y T, Hart W K, White N, Poznansky M C. A CXCR4-dependent chemorepellent signal contributes to the emigration of mature single-positive CD4 cells from the fetal thymus. J Immunol. 2005;175:5115–5125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, Nagler A, Lahav M, Peled A, Habler L, Ponomaryov T, Taichman R S, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Fujii N, Sandbank J, Zipori D, Lapidot T. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznansky M C, Olszak I T, Evans R H, Wang Z, Foxall R B, Olson D P, Weibrecht K, Luster A D, Scadden D T. Thymocyte emigration is mediated by active movement away from stroma-derived factors. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1101–1110. doi: 10.1172/JCI13853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney E A, Priestley G V, Nakamoto B, Collins R G, Beaudet A L, Papayannopoulou T. Mobilization of stem/progenitor cells by sulfated polysaccharides does not require selectin presence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6544–6549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney E A, Lortat-Jacob H, Priestley G V, Nakamoto B, Papayannopoulou T. Sulfated polysaccharides increase plasma levels of SDF-1 in monkeys and mice: involvement in mobilization of stem/progenitor cells. Blood. 2002;99:44–51. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edovitsky E, Lerner I, Zcharia E, Peretz T, Vlodavsky I, Elkin M. Role of endothelial heparanase in delayed-type hypersensitivity. Blood. 2006;107:3609–3616. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel A, Zcharia E, Vagima Y, Itkin T, Kalinkovich A, Dar A, Kollet O, Netzer N, Golan K, Shafat I, Ilan N, Nagler A, Vlodavsky I, Lapidot T. Heparanase regulates retention and proliferation of primitive Sca-1+/c-Kit+/Lin– cells via modulation of the bone marrow microenvironment. Blood. 2008;111:4934–4943. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellme S, Morgelin M, Tapper H, Mellqvist U H, Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. Localization of human neutrophil interleukin-8 (CXCL-8) to organelle(s) distinct from the classical granules and secretory vesicles. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:564–573. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0505248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie P, Paoletti S, Clark-Lewis I, Uguccioni M. Eotaxin-3 is a natural antagonist for CCR2 and exerts a repulsive effect on human monocytes. Blood. 2003;102:789–794. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo R C, Spencer L A, Dvorak A M, Weller P F. Mechanisms of eosinophil secretion: large vesiculotubular carriers mediate transport and release of granule-derived cytokines and other proteins. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:229–236. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0707503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrgruber N, Groger M, Meraner P, Kriehuber E, Petzelbauer P, Brandt S, Stingl G, Rot A, Maurer D. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell recruitment by immobilized CXCR3 ligands. J Immunol. 2004;173:6592–6602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimonaka M, Katagiri K, Nakayama T, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Yoshie O, Kinashi T. Rap1 translates chemokine signals to integrin activation, cell polarization, and motility across vascular endothelium under flow. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:417–427. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R A, Chong B, Mirchandani N, Brinster N K, Yamanaka K, Dowgiert R K, Kupper T S. The vast majority of CLA+ T cells are resident in normal skin. J Immunol. 2006;176:4431–4439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin Y H, Sackstein R, Cai J P. Lymphocyte-homing receptors and preferential migration pathways. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1991;196:374–380. doi: 10.3181/00379727-196-43201a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papeta N, Chen T, Vianello F, Gererty L, Malik A, Mok Y T, Tharp W G, Bagley J, Zhao G, Stevceva L, Yoon V, Sykes M, Sachs D, Iacomini J, Poznansky M C. Long-term survival of transplanted allogeneic cells engineered to express a T cell chemorepellent. Transplantation. 2007;83:174–183. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000250658.00925.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.