Abstract

The structure and unfolding of metal-free (apo) human wild-type SOD1 and three pathogenic variants of SOD1 (A4V, G93R, and H48Q) that cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis have been studied with amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange and mass spectrometry. The results indicate that a significant proportion of each of these proteins exists in solution in a conformation in which some strands of the β-barrel (i.e. β2) are well protected from exchange at physiological temperature (37 °C), whereas other strands (i.e. β3 and β4) appear to be unprotected from hydrogen/deuterium exchange. Moreover, the thermal unfolding of these proteins does not result in the uniform incorporation of deuterium throughout the polypeptide but involves the local unfolding of different residues at different temperatures. Some regions of the proteins (i.e. the “Greek key” loop, residues 104–116) unfold at a significantly higher temperature than other regions (i.e. β3 and β4, residues 21–53). Together, these results show that human wild-type apo-SOD1 and variants have a partially unfolded β-barrel at physiological temperature and unfold non-cooperatively.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)3 is the most common motor neuron disease in the United States, and the occurrence is predominantly sporadic and without a known cause. Approximately 10% of cases are familial, however, and 20% of these familial cases are caused by mutations in the gene that encodes the antioxidant enzyme copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) (1, 2). Over 90% of these mutations encode single amino acid substitutions but some encode insertions, deletions, and C-terminal truncations. A large amount of experimental evidence has shown that mutations of SOD1 induce ALS by imparting a toxic function to the protein that is hypothesized to be an increased propensity to misfold and self-assemble into oligomeric structures (3–6).

There now are >120 known ALS mutations of SOD1 that give rise to a similar clinical pathology. ALS mutations have diverse effects on the properties of the SOD1 polypeptide. Some decrease the thermal stability of folded SOD1, whereas others increase thermal stability (7, 8); and some diminish the affinity for Cu2+ or Zn2+ (each subunit of the SOD1 homodimer can coordinate one Cu2+ and one Zn2+ ion), whereas others do not perturb metal binding (2, 9). Other ALS mutations (i.e. C146R) inhibit the formation of the native intramolecular disulfide between Cys57 and Cys146 (10). ALS mutant SOD1 proteins that lack this disulfide bond or that cannot coordinate copper or zinc have lower conformational stability (2, 11) and, possibly, a higher propensity to aggregate than wild-type holo-SOD1 (10).

Two well recognized mechanisms by which an amino acid substitution can promote the aggregation of a protein is by lowering the free energy of unfolding and by reducing the cooperativity of folding (12). The destabilization of a protein's native fold or a reduction in cooperativity can render hydrophobic residues or hydrogen bond donors and acceptors more available for non-native intermolecular interactions that initiate and propagate aggregation (13).

In this work, we describe our investigation of the solution structure of three ALS variants of SOD1 (A4V, G93R, and H48Q) and human wild-type (hWT) SOD1 by measuring their rates of amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX) with mass spectrometry (13–16). We were able to document the exchange of hydrogen on the backbone amide and not the more rapidly exchanging functionalities such as alcohol or amine groups. Our goal was to test the hypothesis that ALS-linked mutations that are located in different regions of the protein can lead to a common region of structural perturbation. This similarity has been observed for various pathogenic variants of lysozyme that cause amyloidosis (13).

Recent work from our laboratory has shown that SOD1 can convert to amyloid fibrils under physiologically relevant conditions and that a small amount of disulfide-reduced hWT apo-SOD1 can initiate fibrillation in apo and partially metalated forms of SOD1 (17). We have also observed that more stable forms of SOD1 (i.e. disulfide-intact apo-SOD1) that do not initiate aggregation do, however, become incorporated into the propagating fibril after initiation.

We are therefore interested in identifying regions of disulfide-intact apo-SOD1 (WT and ALS mutants) that might facilitate the intermolecular interactions that occur during the propagation of fibrillation. We are also interested in studying the structural properties of SOD1 during thermal unfolding as opposed to chaotrope-induced unfolding. The high throughput capabilities of mass spectrometry enabled us to examine the structure and unfolding of all four proteins quickly using a standard protocol.

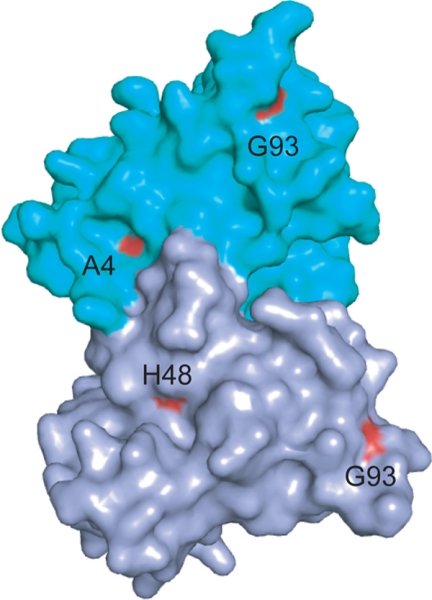

We have chosen to study these three ALS variants based upon several criteria, including the location of each amino acid substitution in the three-dimensional structure of the folded protein, and based upon how the variants fit into our previous classification of ALS mutations into “metal-binding region” and “wild type-like” (2). The A4V substitution occurs at the dimer interface (Fig. 1), distal to the metal-binding region; this WT-like substitution does not diminish the metal-binding abilities of SOD1. There are many ALS substitutions like this, but we chose A4V because it is the most common substitution that is encountered in SOD1-linked ALS cases in North America. The G93R substitution is also a WT-like protein, but the substitution occurs distal to the dimer interface; the effects of substitutions at Gly93 are important for two more reasons. First, Gly93 is the most highly substituted residue in SOD1-linked ALS. Six different mutations result in the substitution of Gly93. Second, Gly93 is thought to function as a “β-barrel plug” that is critical to maintaining the native structure of folded SOD1. The H48Q substitution involves a histidine that normally plays a role in binding the copper ion found at the active site; this metal-binding region substitution greatly diminishes the ability of SOD1 to coordinate Cu2+ at this site and will likely prevent the protein from fully maturing into its holo form.

FIGURE 1.

Surface rendering of x-ray crystal structure of dimeric hWT SOD1 (Protein Data Bank code 2V0A). The three ALS-associated amino acid substitutions studied occur in different regions of the folded protein (colored red). Ala4 is at the dimer interface and does not perturb metal binding. Gly93 is located away from the dimer interface and does not perturb metal binding. His48 is a copper-coordinating residue, and mutation at this site greatly diminishes the ability of the polypeptide to bind copper ion.

Because each of the three selected ALS variants is routinely isolated from yeast expression systems with different stoichiometric equivalents of Cu2+ and Zn2+ cofactors (2, 9), it is necessary to demetalate each variant to study the apo forms of these proteins. Studying the metal-free protein is important because apo-SOD1 represents the least stable form of SOD1 and possibly the state that is most prone to aggregation in vivo; moreover, studying the proteins that are at the same state of metalation (e.g. metal-free) allows a valid comparison of how each amino acid substitution affects the structure of the protein separately from how each substitution might affect metal coordination.

We report that similar regions of the β-barrel are locally unfolded in both hWT and ALS variant SOD1 proteins. For example, each ALS variant protein, as well as the hWT protein, incorporates deuterium rapidly at residues 21–53 at physiological temperatures, whereas other regions of the β-barrel (i.e. residues 7–20) remain protected from deuteration even at elevated temperature. These locally unfolded β-strands could participate in intermolecular interactions that initiate or propagate the aggregation of SOD1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

hWT, G93R, A4V, and H48Q SOD1 Apoproteins

Recombinant proteins were expressed and purified from yeast, demetalated, and characterized as described previously (14). Mass spectral analysis confirmed the identity of each and revealed >95% purity. The proteins were handled and stored as described previously (14).

Global HDX

Deuterated potassium phosphate buffer (10 mm), pD 7.4, was prepared as described previously (14). A fresh aliquot of buffer was used for each experiment. Global HDX was initiated by diluting solutions of SOD1 samples (800 μm) 1:10 (v/v) into deuterated phosphate buffer at 10 °C. The samples were incubated at this temperature for 2 h, and mass measurements were made on an aliquot of the solution to measure the level of deuterium incorporation. The temperature of the remaining solution was then increased by 2 °C using a MiniCycler PCR machine (MJ Research). After a 3-min equilibration period, another sample of protein was removed and analyzed by mass spectrometry (7). The temperature was then increased another 2 °C, and the process was repeated.

Site-specific HDX

Protein solutions (20 μl of 800 μm) and deuterated phosphate buffer (300 μl) were first individually equilibrated at 10 °C in thin-walled PCR tubes. HDX was initiated by transferring 180 μl of deuterated phosphate buffer into the tube containing the protein. The resulting solution was mixed, sealed, and incubated at 10 °C for 2 h.

Following incubation, a 20-μl aliquot of solution was removed and frozen with liquid N2 and then stored on dry ice. The temperature on the PCR machine was increased by 5 °C, and the remaining protein solution was allowed to equilibrate for 4 min. Another aliquot was then removed, flash-frozen, and stored on dry ice. This process was repeated until all the solution had been consumed. To determine the maximum degree of deuterium incorporation that can be achieved under these conditions, experiments were also conducted with thermally denatured protein that was heated to 75 °C for 5 min in the deuterated incubation buffer.

Pepsin Digestion

Solutions of pepsin and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride were prepared as described previously (14). A sample of previously HDX-treated protein was first removed from the dry ice and allowed to thaw at 10 °C for 4.5 min. Following this, further HDX was quenched; proteolysis was simultaneously initiated by the addition of pepsin solution; and the sample was analyzed as described previously (14). In the case of H48Q apo-SOD1, digestion by soluble pepsin was slow, and it was necessary to digest the protein with immobilized pepsin in the presence of 3 m guanidine hydrochloride.

Immobilized pepsin digestion cartridges were prepared as follows. 75 μl of immobilized pepsin (Pierce) was dispensed into spin filter cartridges and centrifuged briefly at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and 460 μl of 100 mm potassium phosphate, pH 2.4, was added to each cartridge. The cartridges were centrifuged again, and the supernatants were discarded. This washing process was repeated again, and the cartridges were stored at −70 °C.

3 m guanidine hydrochloride was prepared in 100 mm potassium phosphate, pH 2.4. A few minutes before commencing each digestion, a small magnetic stir bar was added to an immobilized pepsin cartridge, and the cartridge was placed in an insulated container on ice and allowed to warm to 0 °C for a few minutes. 40 μl of ice-cold 3 m guanidine hydrochloride and 7 μl of 500 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride was then added, and stirring was initiated. Following a 4.5-min thaw at 10 °C, a 20-μl protein aliquot was added, and the mixture was allowed to stir for 10 min at 0 °C. The cartridge was then centrifuged at 0 °C, and the supernatant was analyzed as described previously (14).

Electrospray Ionization-Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

The solutions obtained via both soluble and immobilized pepsin digestion were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, and the data were analyzed as described previously (14).

RESULTS

Global HDX of SOD1 Apoproteins

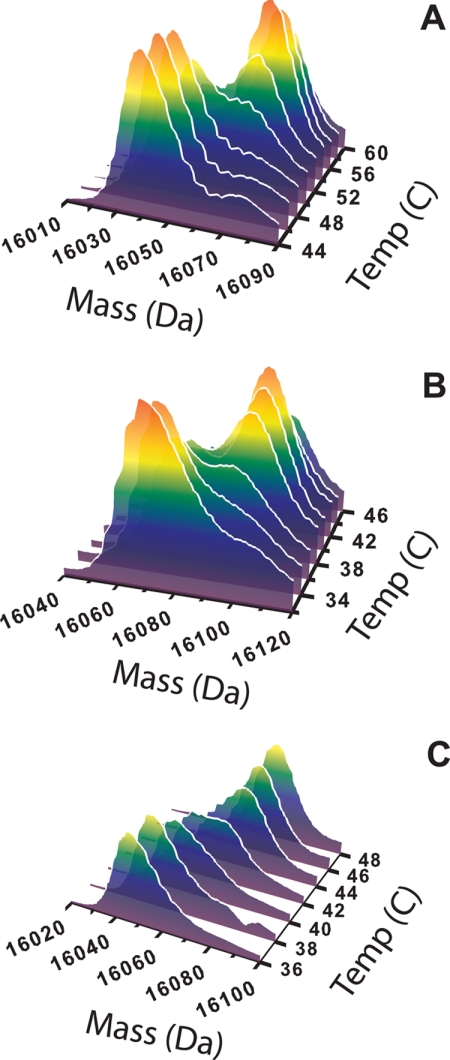

An apparent equilibrium level of deuterium incorporation was established after a 2-h incubation of all SOD1 apoproteins in deuterated buffer (10 °C) as verified by a nearly constant molecular mass of the intact protein as a function of time. The mass of each SOD1 protein was ∼20 Da less than the mass of the fully deuterated protein (prepared by thermal denaturation), indicating that ∼20 backbone amides are structured and retain protons that do not undergo exchange (because of restricted solvent accessibility and/or hydrogen bonding (18–20) or variations in the electrostatic potential at the surface of the protein (21, 22)). At this temperature, the molecular mass reconstructs for the intact proteins are unimodal and symmetrical, with no substantial contribution present from the fully exchanged, perdeuterated protein. As the temperature is increased, slow and gradual increases in masses are observed due to the incorporation of additional deuterium. The mass reconstructs for hWT SOD1 remain unimodal and symmetrical until the temperature approaches the melting transition temperature (52 °C) of hWT apo-SOD1 (7). At this temperature, the reconstruct becomes bimodal with the appearance of a new mass peak corresponding to the fully deuterated protein (Fig. 2A). In the case of the A4V mutant, the presence of the fully exchanged form appears at 36 °C (Fig. 2B), whereas in the case of the H48Q apoprotein, the fully exchanged form appears at 42 °C (Fig. 2C). In the case of hWT and A4V SOD1, the isotopic envelopes for the protected and fully exchanged form are resolved into two distinguishable peaks. However, in the case of the H48Q mutant, these peaks cannot be resolved.

FIGURE 2.

Molecular mass reconstructs for hWT (A), A4V (B), and H48Q (C) SOD1 that depict the thermal unfolding of each apoprotein in 90% D2O. In the case of hWT SOD1, the mass reconstruct remains unimodal until 52 °C, the melting point of the apoprotein as determined by DSC. In the case of A4V, the fully exchanged form appears at 36 °C, and in H48Q, the fully exchanged form appears at 42 °C. The fully deuterated, unfolded form of each ALS variant protein begins to emerge at a temperature that is ∼6 °C below the melting point (Tm) of each protein as determined by DSC (Tm = 42 °C for A4V and 46 °C for H48Q).

HDX in hWT and ALS Mutant SOD1 Proteins at Residues 7–20 (Loop I, β2-Strand) and 104–116 (Loop IV)

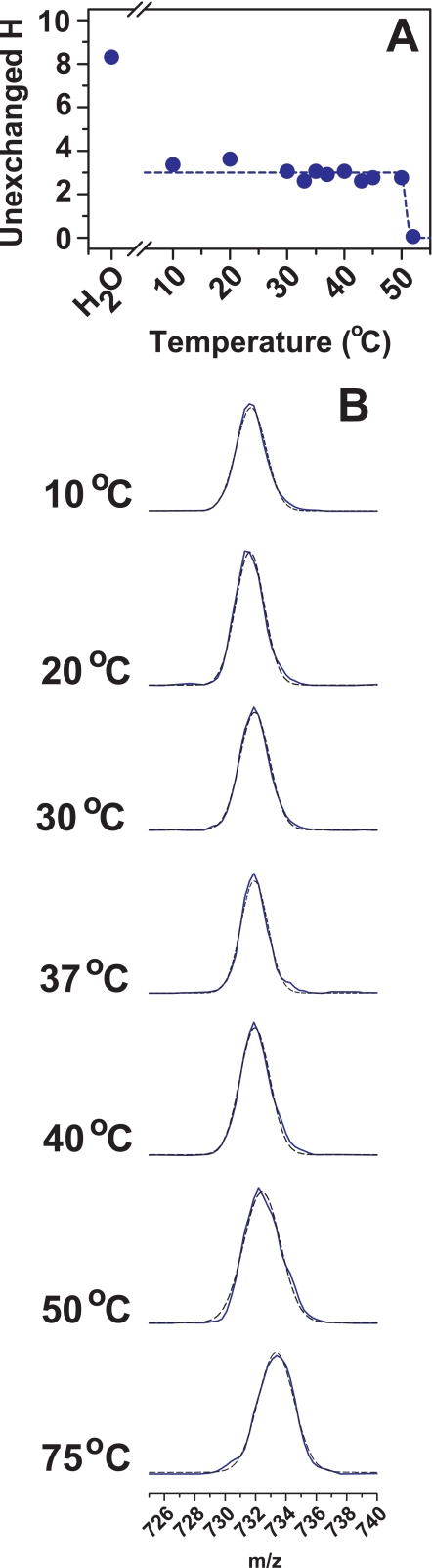

As the temperature of solutions containing hWT and mutant SOD1 apoproteins is increased to <50 °C, the shape of the peak of the [MH2]2+ ion for peptides 7–20 and 104–116 remains unimodal and symmetrical (Fig. 3 shows data for hWT apopeptide 7–20). The incorporation of deuterium begins to occur rapidly for hWT SOD1 at ∼50 °C (only 2 °C below the Tm measured by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (7)). Residues 7–20 for H48Q and G93R SOD1 apoproteins are also protected from exchange at elevated temperature (e.g. >37 °C): the SOD1 proteins do not begin to populate states that incorporate deuterium into this region until the incubation temperature is within ∼2 °C of the DSC melting points for these proteins (47 and 44 °C, respectively (7)). Likewise, the shapes of the peaks for the [MH2]2+ ions for these proteins remain unimodal and symmetrical throughout the temperature range. In contrast, residues 7–20 of A4V SOD1 become perdeuterated at 35 °C (although the global melting temperature for A4V apo-SOD1 is >40 °C (7); see supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 3.

A, HDX profiles for the peptide containing residues 7–20 from hWT apo-SOD1 showing deuterium incorporation (in terms of a decreasing number of unexchanged protons) as a function of temperature. In the cases in which a bimodal mass distribution is present, the degree of deuterium incorporation into the protected (incompletely exchanged) species is plotted. The data are fitted with three-parameter sigmoidal curves to determine the temperatures at which the degree of protection exhibited by the more protected forms decrease to 50% of the low temperature value. For reference, the number of unexchanged protons for protein dissolved in water at 20 °C is shown. B, regions of the mass spectra showing the doubly charged [MH2]2+ ions for this peptide obtained from hWT apo-SOD1 during the course of the D2O incubation (blue lines). The black dashed lines represent the fitting of a Gaussian curve to the observed peak; when a bimodal mass distribution was observed, the dashed lines depict the two-component Gaussian curves that yield the experimentally observed peak when added.

As observed in residues 7–20, the degree of incorporation of deuterium into residues 104–116 is similar for both H48Q and G93R; throughout the temperature regime, the shape of the [MH2]2+ ions remains unimodal, and the degree of HDX is temperature-independent until 43 °C for both proteins. In the case of the A4V mutant, however, both of these regions of the protein are destabilized and perdeuterated at 35 °C (supplemental Fig. S1).

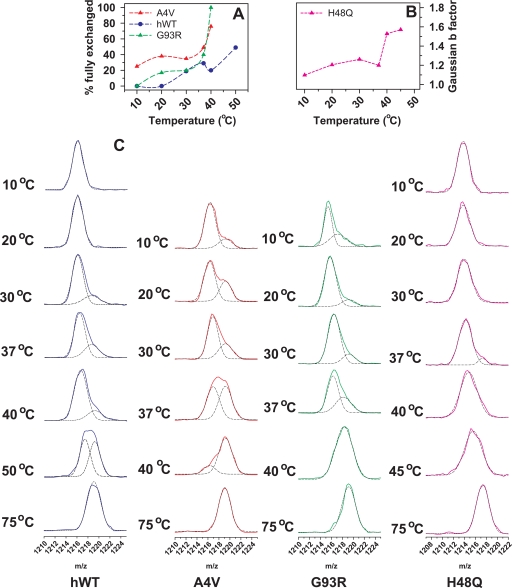

HDX in hWT and Mutant SOD1 Proteins at Residues 21–53 (Loops II and III, β3- and β4-Strands)

The shape of the [MH3]3+ ion for peptide 21–53 from hWT SOD1 is unimodal and symmetrical at temperatures below 25 °C (Fig. 4), suggesting that this region of the protein undergoes HDX via an EX2 process. At temperatures of 30 °C and above, however, the peak becomee bimodal, and a heavier peak contributes to 10–20% of the total signal intensity. This heavier peak has an m/z value consistent with the perdeuterated peptide. This bimodal distribution suggests the presence of a minor subpopulation exchanging via an EX1 mechanism (14), i.e. this subpopulation of hWT SOD1 is locally unfolded in a region that includes residues 21–53.

FIGURE 4.

HDX profiles for the triply charged [MH3]3+ peptide ion formed from residues 21–53 from SOD1 apoproteins. A, profiles of the fractions of fully exchanged peptide 21–53 are shown as a function of temperature for the hWT, A4V, and G93R SOD1 proteins. In this plot, the percentages of fully exchanged peptides are determined by the fractional area under the deconvoluted m/z curves. In the case of H48Q SOD1, the m/z curve cannot be reliably deconvoluted into two populations. B, the peak width for the [MH3]3+ peptide ion as a function of temperature for this region of H48Q SOD1 is plotted. The peak width is measured in terms of the b parameter yielded from a four-parameter Gaussian curve fitting. C, a plot of the regions of the mass spectra shows the shapes of the m/z curves for all four SOD1 proteins. The black dashed lines represent a Gaussian curve fitting of the observed peak. In the event of a bimodal mass distribution, the dashed lines depict the component Gaussian curves that in summation yield the observed peak.

The degree of incorporation of deuterium into residues 21–53 in all three ALS variants is different from that of hWT SOD1. For example, in the G93R mutant, the shape of the [MH3]3+ ion for peptide 21–53 is bimodal even at 10 °C. At this temperature, the higher m/z peak makes a substantial (∼30%) contribution to the overall signal intensity from the peptide. The perdeuterated form of this peptide increases in intensity at 20 °C, and its contribution to the total signal intensity increases as the temperature is increased to 37 °C. By 40 °C, the perdeuterated mass peak represents >90% of the overall signal intensity. In the case of A4V, the HDX behavior is very similar in this region as well, except that the perdeuterated peptide is present at lower temperature (e.g. 10 °C) (Fig. 4).

In contrast to hWT SOD1 and the WT-like mutants, the mass of peptide 21–53 from H48Q does not exhibit a bimodal shape until 37 °C. At 37 °C, however, the intensity of the signal for the fully deuterated peptide 1–53 is low (and much lower than observed with hWT SOD1) (Fig. 4).

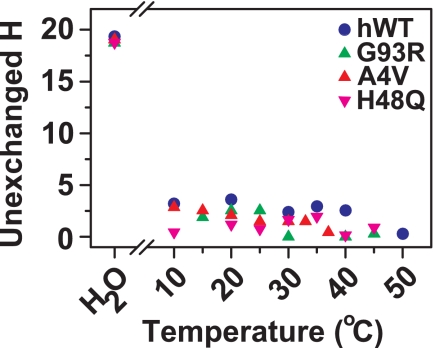

HDX in hWT and Mutant SOD1 Proteins at Residues 117–144 (Loop IV)

In both hWT and all mutant SOD1 apoproteins examined, this region of the structure (primarily made up of the electrostatic loop but also containing a few residues of the β7- and β8-strands) exhibits no protection from perdeuteration even at 10 °C (Fig. 5). A similar result was reported previously for metal-free A4V and hWT apo-SOD1 at 4 °C (14).

FIGURE 5.

Residues 117–144 of hWT, A4V, G93R, and H48Q apo-SOD1 (containing the electrostatic loop) exchange at a similarly rapid rate and are equally disordered in all four proteins. This plot shows that residues 117–144 from all four proteins retain only approximately two unexchanged hydrogens (of ∼19) after 2 h in 90% D2O at 10 °C and pD 7.4. Aliquots of each protein were then heated to 20, 30, 40, and 50 °C. The two unexchanged hydrogen in residues 117–144 for each protein are exchanged with solvent at 50 °C. The data points labeled H2O refer to the mass of the peptide comprising residues 117–144 in H2O.

It has been reported recently, based on electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry and HDX, that the electrostatic loop of SOD1 exchanges faster in several ALS mutant proteins than in hWT SOD1 (2); all of the SOD1 proteins studied were in the “as-isolated” metalation states. A complication in that study is that such as-isolated SOD1 proteins isolated from Escherichia coli or yeast are incompletely metalated and therefore heterogeneous. Such samples consist of mixtures of SOD1 proteins with different amounts of metal ions bound (e.g. Zn1Cu1, Zn2Cu1, Zn1Cu2, Zn2Cu0, etc.). Each derivative is therefore likely to have different rates of HDX and different rates of proteolysis. In the present study, we compared homogenous samples of SOD1 apoproteins (i.e. Zn0Cu0), and we report that the electrostatic loop is not destabilized in A4V, G93R, and H48Q mutant apo-SOD1 compared with hWT apo-SOD1. In fact, this loop is equally disordered in hWT, A4V, G93R, and H48Q apo-SOD1 (Fig. 5). Considering that the electrostatic loop is disordered in apo-SOD1 and becomes folded upon the coordination of copper and zinc (according to NMR (23, 24) and x-ray crystallography (25)), it is not surprising that a substitution that lowers the affinity of SOD1 for metals will prevent this region from folding (at least to some degree). It should also be noted that a destabilization of the electrostatic loop of ALS mutant SOD1 cannot be considered a common property (26) of ALS mutant SOD1 proteins because this region is not even present in the C-terminal truncation mutants of SOD1 that do cause ALS (8).

DISCUSSION

Measuring the thermal unfolding of hWT SOD1 with global HDX and mass spectrometry yielded results that are quantitatively consistent with thermal unfolding experiments measured with DSC (7); an analysis of thermal unfolding of SOD1 with both methods revealed that the protein unfolds cooperatively near 52 °C. Interestingly, in global melt experiments, hWT SOD1 does not appreciably exhibit a fully exchanged form until the incubation temperature reaches 52 °C. In contrast, all three mutant proteins examined in this work indicate that a substantial population has undergone complete exchange at a temperature ∼6 °C below their respective melting temperatures; this complete exchange of hydrogen with deuterium at temperatures so far below the Tm suggests that the ALS mutant proteins unfold more non-cooperatively than the hWT protein.

Measuring the HDX of local regions of SOD1 with acid quenching and proteolysis showed, however, that the thermal unfolding of SOD1 is not entirely cooperative: residues 21–53 of all four proteins begin to unfold at a lower temperature than residues 104–116 or 7–20. In addition, other regions such as 117–144 are never “folded” (even at 10 °C), as demonstrated by the rapid deuteration seen in all three proteins.

Structural Rigidity in the Greek Key Loop (Residues 104–116) and β2-Strand (Residues 7–20) of hWT and ALS Variant SOD1

Despite the fact that the intrinsic rate of amide hydrogen exchange is predicted to change by a factor of 100 as temperature is increased from 10 to 50 °C (27–29), the rate of HDX of residues 7–20 does not change for hWT SOD1 across this temperature range. This result indicates that, throughout the temperature range, this region of the hWT apoprotein remains structured with its residues folded into a stable hydrogen-bonding arrangement. Residues 7–20 and 104–116 seem to unfold “last” and therefore may function as linchpins or anchor points for the folded SOD1 protein. This finding is consistent with NMR structural studies on the monomeric Q133M2SOD protein that have shown that this region is characterized by low root mean square deviation values for both protein backbone and residue heavy atoms (24).

In both G93R and H48Q SOD1, residues 7–20 display a rate of HDX that is similarly independent of temperature as in hWT SOD1, i.e. the degree of deuterium incorporation is constant from 10 °C up to 37 °C, where a gradual sigmoidal decrease in protection begins. In contrast, the A4V variant exhibits similar temperature independence below 30 °C, but above 30 °C, deuterium begins to be more rapidly incorporated into residues 7–20. The low thermostability of A4V and the proximal location of the substitution to residues 7–20 explain this temperature dependence; the A4V protein has the lowest Tm value of the four proteins studied in this work: hWT Tm = 52.5 °C, H48Q Tm = 47.35 °C, G93R Tm = 44.3 °C, and A4V Tm = 40.5 °C (7).

hWT and ALS Variant SOD1 Have a Partially Unfolded β-Barrel at 37 °C

At physiological temperature, it must be remembered that there is no subpopulation of hWT apo-SOD1 that is fully deuterated at residues 7–20 or 104–116 (e.g. locally unfolded at residues 7–20 or 21–53). The hWT SOD protein that is becoming fully deuterated at residues 21–53 is therefore unfolding at residues 21–53 at a rate sufficient for the incorporation of deuterons, whereas other residues such as 7–20 and 104–116 are not unfolding at rates that allow the incorporation of deuterons into the backbone. We therefore refer to hWT SOD1 as being “partially unfolded.” Because the region that is partially unfolded includes two β-strands (β3 and β4) and because other β-strands (β2) are not partially unfolded and protected from HDX, we describe the hWT SOD1 protein as having a partially unfolded β-barrel at physiological temperature.

The abundance of hWT apo-SOD1 that has a partially unfolded β-barrel remains constant between 30 and 45 °C (e.g. the ratio of signal intensity of lighter and heavier peaks in Fig. 4 is a constant 3:1). The static nature of this bimodal mass distribution suggests that the local unfolding of the β-barrel at residues 21–53 is slower than the intrinsic rate of amide HDX for an unstructured polypeptide (∼103 min−1) at physiological temperature.

Similar to hWT SOD1, all three mutant SOD1 proteins examined contain a subpopulation that undergoes partial unfolding of the β-barrel so as to allow for complete isotopic exchange of residues 21–53. Nonetheless, the dynamics of this region in all three mutants is clearly distinguishable from that of the hWT protein. For example, residues 21–53 of G93R exchange similarly to hWT SOD1 below 37 °C, but the intensity for fully exchanged peptide dramatically increases in G93R above 37 °C such that the locally unfolded G93R protein is the predominant species at 40 °C. The temperature at which this type of transition occurs for each protein correlates with, but does not equal, the melting transition temperature for each protein that was measured previously with DSC (7).

Previous work from our laboratory showed that A4V apo-SOD1 undergoes a slow unfolding at residues 21–53 at 4 °C (14). However, at this temperature, the unfolding process is sufficiently slow that the completely deuterated form never exceeds the protected form after 300 min in D2O. At higher temperatures, the localized unfolding of residues 21–53 becomes more pronounced in A4V SOD1. At 37 °C, for example, ∼50% of the A4V proteins are completely deuterated; at 40 °C, this fraction increases to ∼90%.

The metal-binding region mutant H48Q exhibits behavior in this region that is similar to that of G93R, A4V, and hWT SOD1. Approximately ∼15% of H48Q is fully deuterated at residues 21–53 at 37 °C; between 40 and 45 °C, a majority of H48Q SOD1 proteins are completely deuterated at residues 21–53.

We point out that a recent investigation by Agar et al. (26) into the structure of hWT and ALS mutant SOD1 proteins (including A4V) failed to detect the type of local unfolding that we detected herein with hWT, G93R, and H48Q apo-SOD1 and that we detected in our previous study of A4V apo-SOD1 (7). As already mentioned, this discrepancy could be due to the fact that the study by Agar et al. involved metalated A4V (1.62 eq of zinc and 0.22 eq of copper) and that the local unfolding that we observed in the β-barrel (the bimodal mass distribution that we observed for residues 21–53) might occur only in metal-free A4V SOD1. In addition to being metalated, the A4V protein was also studied at 4 °C in the study by Agar et al. Local unfolding of apo-A4V SOD1 has been detected at 4 °C (26); however, this temperature might be too low to observe local unfolding in the metalated form of A4V, which is expected to be more structurally rigid and thermostable than A4V apo-SOD1. Unfortunately, because we do not have access to the original mass spectra of the peptides from any protein, we cannot independently analyze the symmetry of the molecular ions of the peptides from the study by Agar et al.

Conclusions

The results presented here provide clues as to the regions of SOD1 that are sampling unfolded states at physiological temperature and that are potentially able to interact with other SOD1 subunits and/or be restructured during fibrillation. Specifically, subpopulations of hWT and mutant SOD1 show complete exchange in segment 21–53 at 37 °C, suggesting that the conformational flexibility in this region could allow, perhaps be necessary, for the ability of soluble SOD1 to self-assemble into oligomeric structures such as amyloid protofibrils. Preventing the local unfolding of the β-barrel of hWT or ALS variant SOD1 at residues 21–53 could be an important aim in the design of pharmacological agents that prevent the oligomerization and fibrillation of SOD1 in vivo (30–32).

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants NS-049134, DK46828, and GM28222.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures” and Fig. S1.

- ALS

- amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- hWT

- human wild-type

- HDX

- hydrogen/deuterium exchange

- DSC

- differential scanning calorimetry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosen D. R., Siddique T., Patterson D., Figlewicz D. A., Sapp P., Hentati A., Donaldson D., Goto J., O'Regan J. P., Deng H. X., Rahmani Z., Krizus A., Mckenna-Yasek D., Cayabyab A., Gaston S. M. (1993) Nature 362, 59–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valentine J. S., Doucette P. A., Zittin Potter S. (2005) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 563–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston J. A., Dalton M. J., Gurney M. E., Kopito R. R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 12571–12576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J., Xu G., Borchelt D. R. (2002) Neurobiol. Dis. 9, 139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurney M. E., Pu H., Chiu A. Y., Dal Canto M. C., Polchow C. Y., Alexander D. D., Caliendo J., Hentati A., Kwon Y. W., Deng H. X., Chen W., Zhai P., Sufit R. L., Siddique T. (1994) Science 264, 1772–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw B. F., Lelie H. L., Durazo A., Nersissian A. M., Xu G., Chan P. K., Gralla E. B., Tiwari A., Hayward L. J., Borchelt D. R., Valentine J. S., Whitelegge J. P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8340–8350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez J. A., Shaw B. F., Durazo A., Sohn S. H., Doucette P. A., Nersissian A. M., Faull K. F., Eggers D. K., Tiwari A., Hayward L. J., Valentine J. S. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10516–10521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw B. F., Valentine J. S. (2007) Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 78–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayward L. J., Rodriguez J. A., Kim J. W., Tiwari A., Goto J. J., Cabelli D. E., Valentine J. S., Brown R. H., Jr. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15923–15931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oztug Durer Z. A., Cohlberg J. A., Dinh P., Padua S., Ehrenclou K., Downes S., Tan J. K., Nakano Y., Bowman C. J., Hoskins J. L., Kwon C., Mason A. Z., Rodriguez J. A., Doucette P. A., Shaw B. F., Selverstone Valentine J. S. (2009) PLoS One 4, e5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnesano F., Banci L., Bertini I., Martinelli M., Furukawa Y., O'Halloran T. V. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47998– 48003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiti F., Dobson C. M. (2006) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 333–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumoulin M., Canet D., Last A. M., Pardon E., Archer D. B., Muyldermans S., Wyns L., Matagne A., Robinson C. V., Redfield C., Dobson C. M. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 346, 773–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw B. F., Durazo A., Nersissian A. M., Whitelegge J. P., Faull K. F., Valentine J. S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18167–18176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith D. L., Deng Y., Zhang Z. (1997) J. Mass Spectrom. 32, 135–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z., Post C. B., Smith D. L. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 779–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chattopadhyay M., Durazo A., Sohn S. H., Strong C. D., Gralla E. B., Whitelegge J. P., Valentine J. S. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18663–18668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner G., Wüthrich K. (1982) J. Mol. Biol. 160, 343–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner G., Wüthrich K. (1979) J. Mol. Biol. 134, 75–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner G., Wüthrich K. (1978) Nature 275, 247–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson J. S., LeMaster D. M., Hernández G. (2006) Biophys. J. 91, L93–L95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson J. S., Hernández G., LeMaster D. M. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 6178–6188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Assfalg M., Banci L., Bertini I., Turano P., Vasos P. R. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 330, 145–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banci L., Bertini I., Cramaro F., Del Conte R., Viezzoli M. S. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 9543–9553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strange R. W., Antonyuk S., Hough M. A., Doucette P. A., Rodriguez J. A., Hart P. J., Hayward L. J., Valentine J. S., Hasnain S. S. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 328, 877–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molnar K. S., Karabacak N. M., Johnson J. L., Wang Q., Tiwari A., Hayward L. J., Coales S. J., Hamuro Y., Agar J. N. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30965–30973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishna M. M., Hoang L., Lin Y., Englander S. W. (2004) Methods 34, 51–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishna N. R., Goldstein G., Glickson J. D. (1980) Biopolymers 19, 2003–2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krishna N. R., Huang D. H., Glickson J. D., Rowan R., 3rd, Walter R. ( 1979) Biophys. J. 26, 345–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ray S. S., Nowak R. J., Brown R. H., Jr., Lansbury P. T., Jr. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3639–3644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee V. M. (2002) Neurobiol. Aging 23, 1039–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bieler S., Soto C. (2004) Curr. Drug Targets 5, 553–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.