Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Numerous new genes have recently been identified in genome-wide association studies for type 2 diabetes. Most are highly expressed in beta cells and presumably play important roles in their function. However, these genes account for only a small proportion of total risk and there are likely to be additional candidate genes not detected by current methodology. We therefore investigated islets from the polygenic New Zealand mouse (NZL) model of diet-induced beta cell dysfunction to identify novel genes and pathways that may play a role in the pathogenesis of diabetes.

Methods

NZL mice were fed a diabetogenic high-fat diet (HF) or a diabetes-protective carbohydrate-free HF diet (CHF). Pancreatic islets were isolated by laser capture microdissection (LCM) and subjected to genome-wide transcriptome analyses.

Results

In the prediabetic state, 2,109 islet transcripts were differentially regulated (>1.5-fold) between HF and CHF diets. Of the genes identified, 39 (e.g. Cacna1d, Chd2, Clip2, Igf2bp2, Dach1, Tspan8) correlated with data from the Diabetes Genetics Initiative and Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium genome-wide scans for type 2 diabetes, thus validating our approach. HF diet induced early changes in gene expression associated with increased cell-cycle progression, proliferation and differentiation of islet cells, and oxidative stress (e.g. Cdkn1b, Tmem27, Pax6, Cat, Prdx4 and Txnip). In addition, pathway analysis identified oxidative phosphorylation as the predominant gene-set that was significantly upregulated in response to the diabetogenic HF diet.

Conclusions/interpretation

We demonstrated that LCM of pancreatic islet cells in combination with transcriptional profiling can be successfully used to identify novel candidate genes for diabetes. Our data strongly implicate glucose-induced oxidative stress in disease progression.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1576-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: Expression profiling, Genome-wide association study, Glucotoxicity, Laser capture microdissection, Lipotoxicity, New Zealand obese mouse, Obesity, Oxidative phosphorylation, Pancreas

Introduction

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity has dramatically increased in recent years, driven by changes in environment and lifestyle interacting with genetic susceptibility. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAs) in large cohorts of patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity have revealed multiple new candidate genes for these metabolic diseases [1]. Interestingly, all of the susceptibility genes for obesity strongly implicate a role for the brain, whereas most of the diabetes susceptibility genes play a role in insulin secretion and beta cell function. However, these genes explain only a small portion of the individual risk of diabetes, and it is likely that there are more candidate genes not detected by current methodology.

Inbred mouse models have been used extensively to identify genetic risk factors for obesity and type 2 diabetes [2, 3]. Chronic hyperglycaemia is the main feature in the diabetic state, and glucotoxicity has been implicated as playing an important role in the development of type 2 diabetes [4]. Several different mechanisms have been proposed to explain the negative effects of chronic hyperglycaemia [5]. For instance, it has been proposed that elevated glucose levels lead to cellular stress, which might damage insulin-producing beta cells [6]. Nevertheless, the significance of data from transcriptional studies of islet cells is limited, since the arduous conventional collagenase digestion protocol for procuring pancreatic islets is known to alter gene expression patterns as observed in collagenase-isolated primary adipose cells [7–9]. In fact, collagenase digestion has been reported to induce a marked increase in expression of proinflammatory genes and of genes involved in hypoxia-induced stress and apoptosis, respectively, i.e. the very same pathways that have been implicated in the pathophysiology of glucose-induced beta cell death [8]. We recently introduced the New Zealand obese mouse (NZO) mouse strain as a suitable disease model for studying the role of dietary carbohydrates in the pathophysiology of high fat-diet induced diabetes [10]. In this model, a carbohydrate-containing high-fat diet (HF) is highly diabetogenic whereas a carbohydrate-free high-fat diet (CHF) protects from diabetes [10]. In the present study we isolated authentic pancreatic islets with laser capture microdissection (LCM) and performed genome-wide expression analyses with samples from HF- and CHF-treated animals. Our results support the concept that glucose-induced oxidative stress in islets is relevant for disease progression.

Methods

Experimental animals

Up to six male New Zealand (NZL)/LtJ mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, MA, USA) were housed per cage (macrolon type III) at a temperature of 22°C with a 12 h light–dark cycle (lights on at 06:00 hours). The animals were kept in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and all experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the State Ministry of Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry (State of Brandenburg, Germany). After weaning at 3 weeks, the animals received either a HF diet (10105721; Altromin, Lage, Germany) (14.6% [wt/wt] fat, 46.8% carbohydrates, 17.1% protein) or a CHF diet (10105789; Altromin) (30.2% [wt/wt] fat, 0% carbohydrates, 26.4% protein) diet. Throughout the study the animals had free access to food and water.

Analysis of body composition

Body composition and body weight were measured weekly. Body composition was measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (Echo MRI Whole Body Composition Analyzer; Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX, USA).

Blood glucose and plasma insulin

Blood glucose was measured weekly under non-fasting conditions in blood samples collected from the tail vein with a blood glucose meter (Ascensia Elite; Bayer Health Care, Leverkusen, Germany). Insulin levels were determined by ELISA (insulin mouse ultra-sensitive ELISA; DRG Instruments, Marburg, Germany).

Glucose tolerance tests

At 8 weeks, animals were fasted for 16 h before the experiment. Each animal received a single i.p. injection of glucose (20% solution, 2.0 g/kg body weight). Samples for determination of blood glucose and plasma insulin concentration were collected at 0, 7.5, 15, 30, 60, 120 and 240 min from the tail tip. Mice were kept in their accustomed cage and had free access to water.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Isolated islet RNA (20–50 ng) was amplified with a whole transcriptome amplification kit (TransPlex; Sigma-Aldrich, Seelze, Germany). The amplified cDNA was purified with a PCR clean-up kit (GenElute; Sigma-Aldrich). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with the 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). The PCR mix (25 µl) was composed of TaqMan universal PCR Master Mix (10 µl; Applied Biosystems), TaqMan-Probe (1 µl; Applied Biosystems) and 10 ng of cDNA per reaction. Relative gene expression was calculated by the ∆∆C t method with Actb as control gene [11]. Expression differences between groups were tested with Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test. p values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Laser capture microdissection and total RNA isolation

Pancreatic sections were prepared at 14 µm thickness using a cryostat (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and mounted on RNase-free membrane-coated slides (P.A.L.M., Wolfratshausen, Germany). Immediately before microdissection, sections were fixed in ethanol and then rehydrated in 75% and 50% ethanol (vol./vol.) for 30 s each. Sections were stained with filtered cresyl violet acetate (Ambion) for 1 min to allow for identification of islets. Next, sections were dehydrated with a graded alcohol series (50%, 75% and 100 % and 100% (vol./vol.), 30 s each). Finally, the slides were placed in HistoClear (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA, USA) for 2 min and left to air-dry under the hood. Out of ten evenly spaced Nissl-stained sections, 500 islets were dissected using a LCM system (P.A.L.M.). Samples were stored in 20 µl of RNAlater (Ambion). Total RNA was isolated from the LCM samples using an RNA extraction kit (RNAqueous Micro; Ambion) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations were determined using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop ND-1000; Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). Quality of the RNA was determined with BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Böblingen, Germany). The RNA integrity value was used as an indicator of RNA quality. Only samples with a RNA integrity value over 4.5 were used for further analysis. Analysis of the coefficients of variation of biological replicate hybridisations confirmed homogenous RNA preparations of sufficient quality for microarray experiments (Electronic supplementary material [ESM] Fig. 1).

Amplification and labelling of LCM-isolated islet RNA

For labelling of the isolated islet RNA we used an RNA amplification system (WT-Ovation Pico; NuGEN, San Carlos, CA, USA) with 100 ng RNA per reaction to produce labelled cDNA.

Hybridisation of Affymetrix microarrays

For genome-wide transcriptome analysis, we used the Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array platform (www.affymetrix.com/products_services/arrays/specific/mouse430_2.affx; version 09.01.2008). LCM-isolated islets from each mouse were processed separately. Labelled cDNA (5 µg) was hybridised on to each array. We analysed NZL samples from isolated islets and total pancreas with respect to two nutritional conditions induced by the HF and CHF diets.

Data processing

The pre-processing and analysis of the microarray data was performed with the R/BioConductor software platform [12]. Arrays for each individual case–control study were normalised using the GC RMA method [13]. Affymetrix gene chip annotations were adapted from latest genome annotations in version 9, based on Ensembl 42, and resulting in 15,758 Ensembl genes [14]. Additional annotation for the Ensembl genes is based on Ensembl 46. Presence tags were calculated following Affymetrix procedures. For quality control, we analysed the coefficient of variation of the raw probe fluorescence intensities for all biological replicates in the hybridisation experiments (ESM Fig. 1). Differential expression was judged by three criteria: (1) the gene is expressed in at least one of the samples, treatment or control. at p ≤ 0.05; (2) the fold-change is >4/3 or <3/4; and (3) the Welsh test p value is p < 0.05.

Identification of disease-related networks using enrichment analyses

Disease-related networks were investigated with two different types of functional information: (1) biological pathways [15] as provided by the KEGG database (www.genome.jp/kegg/; version 09.01.2008); and (2) functional categories using Gene Ontology annotations (Ensembl 41) [16]. These functional information terms define groups of associated genes. Using enrichment analyses with hypergeometric distribution [17], we were able to assign each annotation term a p value that reflects enriched occurrence of differentially expressed genes. In case of Gene Ontology terms, we included only genes with evidence codes inferred from direct assay (IDA), mutant phenotype (IMP), traceable author statement (TAS) or by curator (IC) in order to ensure a high confidence level.

Immunohistochemistry

Pancreatic tissue was fixed in 4.5% (w/v) formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin according to standard procedures. Sections (2 µm) were stained with haematoxylin. Endogenous peroxidase activity in the sectioned tissues was blocked with 3% (v/v) H2O2 and non-specific binding sites were blocked with non-immune goat serum. Subsequently, rabbit polyclonal antibody to carbohydrate-responsive element binding protein (ChREBP; 1:500; GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA) was applied and stained with biotin-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG and streptavidin–biotin–horseradish peroxidase complex (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and diaminobenzidine (Dako Diagnostika, Hamburg, Germany) as substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A ChREBP antibody/peptide complex (aa 800-852; NP_116569; GeneTex) served as control for non-specific binding.

Results

A carbohydrate-free high-fat diet protects from hyperglycaemia and beta cell failure

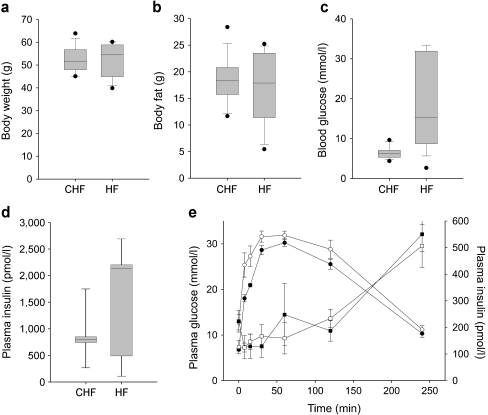

Male NZL mice were raised on two different diets, namely HF (35% calories from fat) and CHF (72% calories from fat). As illustrated in Fig. 1a, the body weight of the animals was similar on both diets, reaching approximately 55 g in week 17. NZL mice also developed a similar degree of obesity on both diets, with fat depots reaching 36% of total body weight (∼18 g total body fat; Fig. 1b). However, whereas most animals on the HF developed severe hyperglycaemia beginning at week 8, with blood glucose levels progressively increasing, animals on the CHF maintained normal glycaemia until the end of the dietary intervention (Fig. 1c, ESM Fig. 2). At week 8, animals from both diet groups displayed severe glucose intolerance and, as described earlier [18], a markedly blunted early-phase secretion of insulin in response to a glucose bolus (Fig. 1e). At week 17, the prevalence of diabetes (blood glucose levels >13.88 mmol/l) in HF mice was 63%. In contrast, no incidence of diabetes was observed in the CHF group (ESM Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A CHF diet protects from hyperglycaemia and diabetes. a Body weight of 17-week-old male NZL mice fed either HF or CHF. b Body fat content. c Blood glucose levels at week 17. d Plasma insulin levels at week 22. Values were derived from 14 to 16 animals per group. e Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test at week 8, five animals per group. Values are mean ± SE. White circles, CHF plasma glucose; black circles, HF plasma glucose; white triangles, CHF plasma insulin; black triangles, HF plasma insulin

Enrichment of transcripts in islets

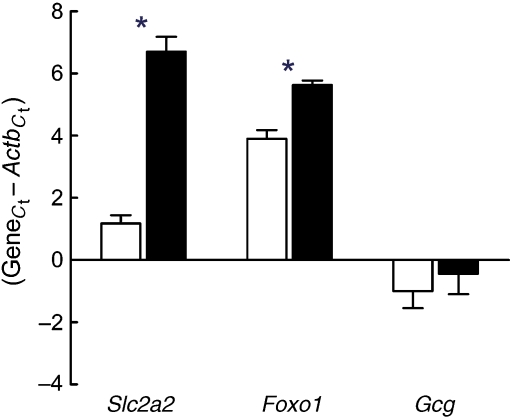

To assess the effectiveness of our islet isolation procedure, we performed quantitative real-time PCR with cDNA derived from laser-captured islets and cDNA from whole pancreas preparations. As shown in Fig. 2, the cDNAs for the islet-specific glucose transporter Slc2a2, Foxo1 and Gcg were enriched in islet preparations. To obtain a profile of global transcript abundance in islets, we compared whole-genome expression data from islets of 8-week-old CHF-fed mice with data obtained by hybridisation of RNA from total pancreas of matched animals. As expected, the list of the most abundant transcripts in islets included insulin, glucagon, islet amyloid polypeptide, carboxypeptidase E and other well established genes expressed in alpha and beta cells (ESM Table 1). Transcripts required for protein synthesis, protein secretion and oxidative phosphorylation were also highly abundant in the isolated islets. In contrast, the highest expression levels in total pancreas were observed for hydrolytic enzymes, including pancreatic proteases, lipases and nucleases (data not shown). To identify islet-specific transcripts, we calculated a simple enrichment score by dividing the median-normalised fluorescence intensities from islet and pancreas samples for each transcript. Of the ∼10,000 genes expressed, we identified 238 transcripts that were highly enriched (≥ tenfold) in islets vs total pancreas (ESM Table 2). The list of enriched transcripts includes numerous well-known genes thought to play critical roles in islet functions such as insulin production (e.g. Cpe, Pcsk1, Pcsk2) and secretion (e.g. Abcc8, Ucn3, Glp1r, Sst, Slc2a2, Snap25), and cell growth and differentiation (e.g. Pax6, Neurod1, Cdkn1b), as well as genes associated with type 2 diabetes in recent human genome-wide scans (Wfs1, Slc30a8; ESM Table 2). Conversely, ∼400 transcripts were highly enriched (≥ tenfold) in total pancreas vs islets, including the well-known pancreatic hydrolases, Cckar and members of the Reg gene family, all three of which have been implicated in islet cell regeneration (data not shown). However, expression of transcripts derived from exocrine pancreatic cells was greatly reduced in islet preparations (ESM Table 3). Yet, for a number of genes with robust islet-selective expression, the biological function is unknown.

Fig. 2.

Enrichment of selected islet genes in LCM samples. mRNA expression genes was determined by quantitative TaqMan RT-PCR for each gene and for Actb from LCM islets (white bars) and total pancreas (black bars) of 8-week-old mice. Expression levels are presented as change in C t or the cycle number of each gene subtracted from the cycle number of beta-actin (C t value 20.15) for the same cDNA sample. Lower numbers thus correspond to higher expression. Data are means ± SE from five CHF-fed NZL mice. *p ≤ 0.05

Comparison with GWAs for type 2 diabetes

Over recent years, GWAs have revealed numerous genetic loci, some of which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes, insulin secretion and beta cell survival. To determine how successful our approach was in identifying plausible novel candidates, we compared differentially expressed genes from our mouse model for diet-induced diabetes with previously reported single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with type 2 diabetes in humans. We used data from two publicly available genome-wide scans, the Diabetes Genetics Initiative (DGI) study [19] and the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (WTCCC) GWA for diabetes [20]. We compiled a list of 837 SNPs that map to 439 known human genes and are nominally associated with diabetes (p < 0.05) in both scans. Of the 430 mouse orthologue genes, 39 mouse genes were differentially expressed ≥1.5-fold) in our study (Table 1, ESM Fig. 3). Interestingly, the list includes two genes from genetic loci found to be associated with diabetes in recent GWAs, IGF2BP2 [20, 21] and TSPAN8-LGR5 [22], as well as CACNA1D, which is required for pancreatic beta cell generation in mice [23]. We selected nine differentially expressed genes and performed quantitative real-time PCR with RNA from LCM-isolated islets and with RNA from total pancreas. As illustrated in ESM Fig. 4, we were able to validate all five selected genes that were downregulated by the HF, including Dach1, Clip2, Cacna1d, Igf2bp2 and Chd2. In contrast, we were not able to confirm HF-induced upregulation of Ldlrad3, Sil1, Plekha1 and Pdia3 by quantitative real-time PCR.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed mouse islet genes with significant association with human type 2 diabetes in two genome-wide scans

| Symbol | Ratio | SNPs | DGI T2D | WTCCC T2D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/CHFa | Islets/pancreasb | IDc | ORd | p valuee | p valuef | |

| Abcc4 | 1.789 | 1.59 | rs1751052 | 1.179 | 0.026 | 0.018g |

| Arhgap24 | 1.516 | 1.170 | rs12640411 | 0.855 | 0.027 | 0.025g |

| rs12506596 | 0.846 | 0.018 | 0.024g | |||

| rs12644260 | 0.844 | 0.019 | 0.038g | |||

| rs4693716 | 0.849 | 0.023 | 0.026g | |||

| rs1384135 | 0.842 | 0.016 | 0.027g | |||

| rs1384134 | 0.840 | 0.017 | 0.026g | |||

| rs9884932 | 0.845 | 0.018 | 0.025g | |||

| rs10000472 | 0.845 | 0.018 | 0.026g | |||

| rs17389300 | 0.848 | 0.020 | 0.024g | |||

| Cacna1d h | 0.522 | 2.70 | rs12487452 | 0.796 | 0.018 | 0.024g |

| Camkk2 | 0.515 | 2.96 | rs9805130 | 0.841 | 0.004 | 0.044g |

| Car8 | 1.771 | 1.13 | rs10216440 | 0.833 | 0.026 | 0.001g |

| Chd2 h | 0.532 | 21.00 | rs1406712 | 1.379 | 0.039 | 0.023g |

| Clip2 h | 0.435 | 7.91 | rs2528994 | 1.118 | 0.020 | 0.021g |

| rs512023 | 1.098 | 0.029 | 0.042g | |||

| Cobll1 | 2.348 | 0.19 | rs6717858 | 0.892 | 0.027 | 0.026g |

| Ctnnd2 | 1.877 | 9.39 | rs6873671 | 1.138 | 0.025 | 0.034i |

| Esyt2 | 1.602 | 0.47 | rs3816465 | 1.198 | 0.037 | 0.009i |

| rs6873490 | 1.137 | 0.019 | 0.030i | |||

| Dach1 h | 0.352 | 8.78 | rs7991293 | 1.469 | 0.019 | 0.010i |

| Elf1 | 1.855 | 0.24 | rs9525438 | 1.143 | 0.034 | 0.018i |

| rs7799 | 1.143 | 0.028 | 0.005i | |||

| rs9532691 | 1.148 | 0.024 | 0.007i | |||

| Fam45a | 1.571 | 0.60 | rs4752250 | 0.856 | 0.043 | 0.005g |

| rs11198783 | 0.837 | 0.015 | 0.005g | |||

| Gnaq | 1.541 | 0.93 | rs6560613 | 0.777 | 0.034 | 0.007g |

| rs4745664 | 0.839 | 0.024 | 0.040g | |||

| H2-Ea | 1.806 | 0.41 | rs7194 | 0.872 | 0.041 | 0.045g |

| Hnrnpc | 1.582 | 0.87 | rs17092523 | 0.936 | 0.033 | 0.001i |

| rs4982437 | 0.914 | 0.021 | 0.010i | |||

| rs7495 | 0.929 | 0.028 | 0.005i | |||

| rs8009894 | 0.941 | 0.046 | 0.006i | |||

| rs7141230 | 0.938 | 0.039 | 0.004i | |||

| rs7147655 | 0.935 | 0.036 | 0.007i | |||

| Igf2bp2 h | 0.493 | 5.74 | rs4402960 | 1.110 | 0.034 | 0.002g |

| rs7651090 | 1.103 | 0.039 | 0.002g | |||

| Igf2r | 1.904 | 1.24 | rs10945645 | 0.780 | 0.007 | 0.039i |

| rs3798197 | 0.869 | 0.028 | 0.032i | |||

| rs9295119 | 0.836 | 0.040 | 0.012i | |||

| Inpp5d | 0.588 | 2.51 | rs10176895 | 0.7583 | 0.043 | 0.025g |

| rs10189488 | 0.735 | 0.018 | 0.035g | |||

| rs10200271 | 0.7084 | 0.022 | 0.045g | |||

| Klhl21 | 1.688 | 1.22 | rs1556036 | 1.122 | 0.031 | 0.008i |

| Ldlrad3 | 5.274 | 3.56 | rs12361738 | 0.869 | 0.020 | 0.023g |

| Lyar | 1.52 | 0.158 | rs2980089 | 1.217 | 0.016 | 0.05g |

| Mphosph6 | 1.941 | 0.96 | rs1862820 | 1.201 | 0.009 | 0.004g |

| Nampt | 1.584 | 0.48 | rs4730155 | 0.909 | 0.043 | 0.012g |

| Pdia3 | 3.384 | 0.50 | rs8040336 | 0.852 | 0.012 | 0.045g |

| Pdlim5 | 0.561 | 4.80 | rs6830074 | 0.804 | 0.047 | 0.003g |

| rs6812098 | 0.790 | 0.041 | 0.015g | |||

| Phactr1 | 0.525 | 33.9 | rs17617584 | 0.770 | 0.027 | 0.048g |

| rs9296486 | 0.794 | 0.009 | 0.043g | |||

| rs9296488 | 0.799 | 0.011 | 0.032g | |||

| rs9349350 | 0.802 | 0.012 | 0.023g | |||

| rs9357503 | 0.837 | 0.033 | 0.028g | |||

| rs9381439 | 0.804 | 0.013 | 0.035g | |||

| Ppfia3 | 0.6 | 4.41 | rs3764625 | 1.132 | 0.023 | 0.003g |

| Pkib | 2.289 | 1.52 | rs17084680 | 1.085 | 0.025 | 0.614g |

| Plekha1 | 2.424 | 0.51 | rs17103541 | 1.303 | 0.023 | 0.028g |

| Qpct | 3.93 | 0.52 | rs2255991 | 1.368 | 0.029 | 0.01805g,i |

| Sil1 | 1.951 | 0.57 | rs1560656 | 0.871 | 0.022 | 0.042i |

| Stxbp6 | 1.825 | 0.19 | rs17257773 | 1.352 | 0.006 | 0.024i |

| Tacr3 | 2.138 | 1.27 | rs1384401 | 0.828 | 0.011 | 0.015g |

| rs5005634 | 0.835 | 0.011 | 0.011g | |||

| rs7663664 | 0.821 | 0.009 | 0.010g | |||

| Tmem135 | 1.766 | 0.72 | rs10898589 | 1.428 | 0.018 | 0.044g |

| rs10898590 | 1.449 | 0.013 | 0.009g | |||

| Tspan8 | 3.993 | 1.35 | rs10506625 | 0.860 | 0.019 | 0.00007g |

| rs10506626 | 1.146 | 0.015 | 0.00002g | |||

| rs11178648 | 1.158 | 0.014 | 0.00005g | |||

| rs2270584 | 1.146 | 0.012 | 0.00002g | |||

| Ube2z | 1.759 | 0.94 | rs15563 | 0.903 | 0.031 | 0.028i |

| rs46522 | 0.906 | 0.040 | 0.025i | |||

| rs1994970 | 0.907 | 0.040 | 0.033i | |||

| rs4793992 | 0.904 | 0.043 | 0.029i | |||

| Xkr6 | 0.537 | 3.11 | rs7016385 | 1.115 | 0.033 | 0.019g |

Expression of genes was determined with mRNA from LCM islets and from total pancreas of 8-week-old mice

aOnly genes with a significant fold-change (p ≤ 0.05) were included

bRatio of median-normalised fluorescence intensities from islet and pancreas samples for each transcript

cOnly SNPs with p ≤ 0.05 in both GWAs [19, 20] were included

d,eOdds ratios and p values for association with type 2 diabetes in DGI study

fAs above (d,e) in WTCCC Study

gAdditive model; hdifferential expression validated by quantitative real-time; igeneral model

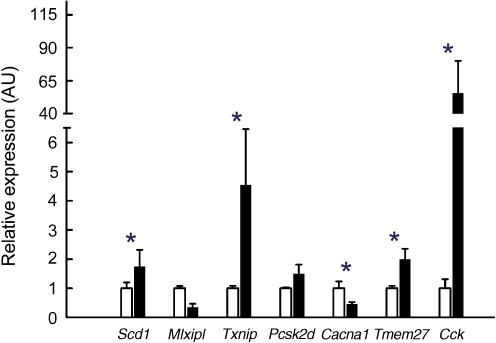

Diet-dependent differentially expressed genes

We identified 3,027 differentially expressed genes in islets of HF- and CHF-fed NZL mice. Of those, 2,109 genes showed at least 1.5-fold changes in gene expression, with 1,496 genes upregulated and expression of 613 genes decreased in response to the HF. We categorised the top 50 differentially expressed genes according to their known or putative biological function and grouped these genes into the following categories of genes involved in: (1) growth and development; (2) protein processing and secretion; (3) metabolism; and (4) signalling (Table 2). In the islets, HF induced gene expression changes associated with increased cell cycle progression, proliferation and differentiation, such as Cdkn1b, Tmem27 and Pax6 (Table 2). Also, several genes involved in insulin production and secretion were differentially regulated by the HF, such as Pcsk1 and Pcsk2 (Table 2). Moreover, known regulators of the cellular redox state such as Txnip, Cat, Gpx1 and Prdx1 to Prdx5 were increased up to fourfold in the islets of HF-fed animals (Table 2). From each of the four functional categories, growth and development, protein processing and secretion, metabolism, and signalling, we selected one to two differentially expressed genes and performed quantitative real-time PCR with RNA from LCM-isolated islets and RNA from total pancreas. As illustrated in Fig. 3, diet-induced changes in expression levels for Cacna1d, Cck, Mlxipl, Txnip and Tmem27 were validated by quantitative real-time PCR in LCM islets. However, the mRNA levels for Cacna1d, Mlxipl, Txnip and Tmem27 were not or only slightly changed by the diet in RNA from total pancreas, indicating that differential expression was restricted to islet cells (data not shown). Moreover, mRNA for Cck (HF-C t value in islets ∼25) was not detected in total pancreas.

Table 2.

Diet-dependent differentially expressed genes in islets

| Symbol per category | Description | Ratio (HF/CHF)a |

|---|---|---|

| Growth and development | ||

| Pax6 | Paired box gene 6 | 0.51 |

| Cdkn1b | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B | 0.40 |

| Pura | Purine rich element binding protein A | 0.37 |

| Dach1 | Dachshund 1 (Drosophila) | 0.35 |

| Metabolism | ||

| Gmds | GDP-mannose 4, 6-dehydratase | 5.02 |

| Ndufa1 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 1 | 4.80 |

| Sqle | Squalene epoxidase | 4.64 |

| Atp5b | ATP synthase, H+ transporting mitochondrial F1 complex, beta subunit | 4.40 |

| Prps1 | Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase 1 | 4.23 |

| Suclg1 | Succinate-CoA ligase, GDP-forming, alpha subunit | 4.14 |

| Pon3 | Paraoxonase 3 | 4.13 |

| Scd1 | Stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 1 | 2.80 |

| Pfkfb2 | 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 2 | 0.41 |

| Cyp4a10 | Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 10 | 0.35 |

| Chkb | Choline kinase beta | 0.34 |

| Eno3 | Enolase 3, beta muscle | 0.34 |

| Mlxipl | MLX interacting protein-like | 0.29 |

| Gmds | GDP-mannose 4, 6-dehydratase | 0.20 |

| Protein processing and secretion | ||

| Rps27l | Ribosomal protein S27-like | 5.05 |

| Psmb7 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type 7 | 4.85 |

| Vamp8 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein 8 | 3.15 |

| Pcsk1 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 | 2.73 |

| Pcsk2 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 2 | 1.92 |

| Vti1b | Vesicle transport through interaction with t-SNAREs 1B homologue | 1.88 |

| Vamp5 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein 5 | 0.40 |

| Sec24a | SEC24 related gene family, member A (S. cerevisiae) | 0.38 |

| Signalling | ||

| Cck | Cholecystokinin | 9.25 |

| Rheb | RAS-homologue enriched in brain | 4.82 |

| Dusp6 | Dual specificity phosphatase 6 | 4.26 |

| Cacna1d | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type, alpha 1D subunit | 0.52 |

| Rps6kb2 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 2 | 0.40 |

| Nlgn1 | Neuroligin 1 | 0.34 |

| Vipr1 | Vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 | 0.33 |

| P2ry6 | Pyrimidinergic receptor P2Y, G-protein coupled, 6 | 0.28 |

| Regulation of redox status | ||

| Txnip | Thioredoxin interacting protein | 4.14 |

| Prdx4 | Peroxiredoxin 4 | 3.10 |

| Prdx5 | Peroxiredoxin 4 | 2.74 |

| Cat | Catalase | 1.95 |

| Gpx1 | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | 2.26 |

| Other | ||

| Ctss | Cathepsin S | 12.98 |

| Cldn11 | Claudin 11 | 11.32 |

| Spp1 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | 4.55 |

| Alg5 | Asparagine-linked glycosylation 5 homolog | 4.54 |

| Tmem27 | Transmembrane protein 27 | 1.94 |

The top 44 differentially expressed genes (HF vs CHF) were categorised according to their known or putative biological function

aMean of five to six Affymetrix chips per condition; only genes with a significant fold-change were included (p ≤ 0.05)

Fig. 3.

Validation of differential expression in islets by quantitative real-time PCR. TaqMan quantitative PCR validation of genes differentially regulated between CHF (white bars) and HF (black bars). The change in expression is shown for selected genes involved in islet growth and development, protein processing and secretion, metabolism, and signalling. Values are normalised to Actb. Data are mean ± SE of five separate mice per group. *p ≤ 0.05

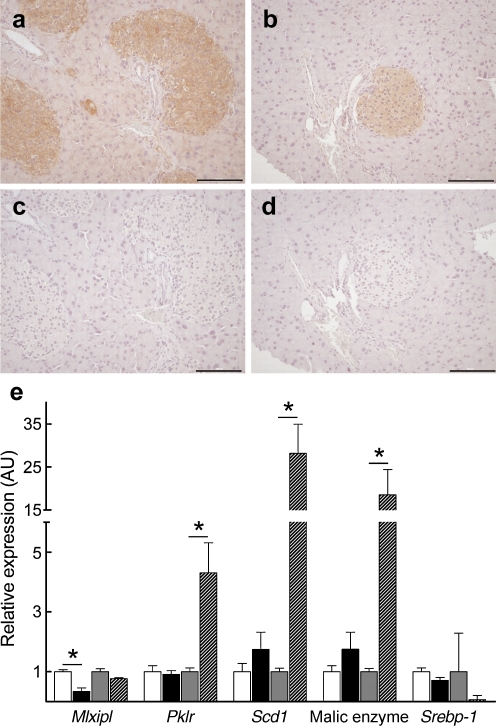

Interestingly, islet mRNA for Chrebp (also known as Mlxipl), a transcription factor that has emerged as a key determinant of lipid synthesis and a major mediator of hepatic conversion of glucose into fat [24], was also significantly decreased in response to the diabetogenic HF (Table 2), a finding validated by quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemical staining of pancreatic sections from NZL and C57BL/6J mice confirmed presence of ChREBP protein in islet cells (Fig. 4a–d), although we were unable to quantify its nuclear localisation. According to quantitative real-time PCR analysis, expression of Chrebp mRNA was comparable in liver and islet tissue. However, only in the liver of the animals, did the HF result in substantial upregulation of Pklr, Scd1 and malic enzyme, whereas no significant changes in gene expression levels were observed in the corresponding islets of the animals (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4.

Islet levels of ChREBP and regulation of lipogenic target genes. Immunohistochemical detection of ChREBP in pancreatic sections from male NZL mice. HF (a) and CHF fed (b) animals at week 8, with (c, d) respective controls with blocking peptide. e TaqMan quantitative PCR validation of ChREBP target genes in islets. Values are normalised to Actb. Data are mean ± SE of five separate mice per group; *p ≤ 0.05. White bars, CHF; black bars, HF; Grey bars, CHF liver; hatched bars, HF liver. Srebp-1 (also known as Srebf1)

Pathway analysis

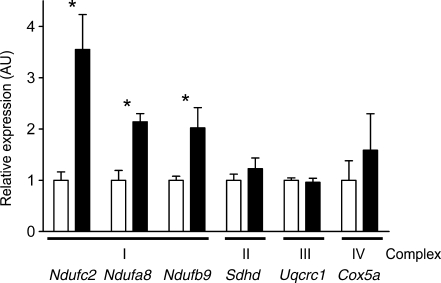

The set of differentially expressed genes was used to perform pathway analysis as described. Gene set enrichment of the most significant KEGG pathways revealed differential expression of genes involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, proteasome, ribosome, pyruvate metabolism, terpenoid biosynthesis, N-glycan biosynthesis, bisphenol A degradation and reductive carboxylate cycle (Table 3, ESM Table 4). Oxidative phosphorylation was the most significantly over-represented pathway (2.31E−12) whose expression was differentially regulated between HF and CHF. About half of the genes annotated for oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), proteasome and ribosome were differentially expressed in islets in response to the dietary regiment. In fact, the majority of these genes annotated for these three pathways were upregulated in response to HF (Table 3). To confirm this observation, we performed quantitative real-time PCR on six OXPHOS genes that are derived from complex I (Ndufa8, Ndufb9 and Ndufc2) and on one from each of complexes II, III and IV (Sdhd, Uqcrc2 and Cox5a, respectively). With the exception of Uqcrc1 from complex III, each transcript was upregulated in response to HF, with significant changes for Ndufa8, Ndufb9 and Ndufc2 (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Gene set enrichment analysis of 3,027 genes differentially regulated by HF and/or CHF diet in islets

| KEGG pathway description | p value | Seta | Sig.Setb | Sig.Set, upregulatedb | Sig.Set, downregulatedb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 2.31 × 10−12 | 96 | 49 | 46 | 3 |

| Proteasome | 1.41 × 10−7 | 25 | 17 | 17 | 0 |

| Ribosome | 0.00297 | 21 | 10 | 9 | 1 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 0.00639 | 37 | 14 | 12 | 2 |

| Terpenoid biosynthesis | 0.00708 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| N-Glycan biosynthesis | 0.00836 | 38 | 14 | 13 | 1 |

| Bisphenol A degradation | 0.0085 | 17 | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| Reductive carboxylate cycle | 0.0095 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

Only pathways with significant changes (p ≤ 0.01) were included

aNumber of genes in KEGG pathway; bdifferentially expressed genes

Fig. 5.

TaqMan quantitative PCR validation of OXPHOS genes in islets. The changes in expression of selected OXPHOS genes are shown. Values are normalised to Actb. Data are mean ± SE of five separate mice per group; *p ≤ 0.05. White bars, CHF; black bars, HF

Discussion

To identify potentially relevant candidate genes involved in type 2 diabetes, we used a model of beta cell failure, NZL mice, fed either a HF or a CHF diet. To gain insights into the pathophysiology of diet-induced beta cell failure and the metabolic pathways mediating downstream effects of the HF, we isolated pancreatic islets with LCM and performed genome-wide expression analyses. Consistent with previous findings [10, 25], our data clearly demonstrate the critical role of dietary carbohydrates in the pathophysiology of high fat-diet induced diabetes. In the obese NZL mice as well as the related NZO strain, a CHF protects from hyperglycaemia and beta cell failure, whereas a carbohydrate-containing HF diet is highly diabetogenic [10]. Since both diets induce a similar degree of adiposity and glucose intolerance, the beta cell toxicity is likely to be due to elevated glucose concentrations.

As expected, numerous genes known to be highly expressed in islets, such as insulin, glucagon and islet amyloid polypeptide, were also highly abundant in the LCM samples. In fact, about 2.5% of all transcripts expressed were highly enriched in islets cells compared with total pancreas. Moreover, many of those transcripts have not been linked to islet cell function previously and may therefore represent novel candidate genes with relevant functions in islet cell biology. Most importantly, however, islet RNA isolated with LCM is likely to reflect the transcriptome of these cells more accurately, compared with the conventional collagenase-digestion method used for islet isolation [7, 8]. In fact, the latter procedure has been reported to induce marked increases in gene expression of proinflammatory genes and of genes involved in hypoxia-induced stress and apoptosis, thereby severely impairing interpretation of expression data derived from metabolically stressed islet cells [7, 8]. Thus, LCM represents an ideal tool to obtain native islet samples without inducing the stress-response of islet isolation.

Recent GWAs have revealed numerous genetic loci associated with type 2 diabetes in humans [1]. So far, there has been a lack of functional data about the involvement of these variants in the pathogenesis of diabetes. However, most of these genes were found to be highly expressed in islets [1]. We identified 39 genes that are highly expressed in the pancreas and were differentially expressed in our mouse model of diet-induced diabetes and nominally associated with diabetes in two independent GWAs, the DGI study and the WTCCC scan for diabetes, respectively [19, 20], thus validating our approach (Table 1). Among these genes is CACNA1D, the voltage-dependent calcium channel, which has been shown to be required for pancreatic beta cell generation in mice [23]. Interestingly, the list also includes two loci that have been found to be associated with type 2 diabetes in recent GWAs, IGF2BP2 [19, 21] and TSPAN8-LGR5 [22]. With regard to the latter region, the most significant association with type 2 diabetes in a meta-analysis of three GWA scans was observed for rs7961581 (p = 1.1 × 10−9), which maps in the intergenic region between TSPAN8 and LGR5 [22]. In mouse islet cells, the diabetogenic HF increased expression of Tspan8 approximately fourfold, whereas Lgr5 expression was not changed (Table 3, data not shown). Thus, our data provide evidence that TSPAN8 is more likely to be functionally related to the development of type 2 diabetes than LGR5. It should be mentioned, however, that our approach has limitations, since we only took into account the two publicly available genome-wide scans on type 2 diabetes susceptibility genes. Moreover, the overlap of differentially expressed genes in islets and genes found in the two GWAs amounts roughly to the number expected by chance. However, this number is likely to be underestimated, because not all genes were tested for association with type 2 diabetes in the merged scans.

Exposure to HF resulted in a substantial number of differentially expressed genes in the islets, reflecting prominent changes of the expression pattern in response to the diet. In fact, the majority of these genes (>80%) were upregulated in HF islets. We have previously shown that in the prediabetic state, HF induces massive hyperglycaemia in the related NZO strain and compensatory hyperplasia of pancreatic islets [10, 26, 27]. Consistent with these data, HF induced gene expression changes associated with increased islet growth and insulin production, such as increased expression of Tmem27, the proapoptotic thioredoxin-interacting protein Txnip, Cck and Pcsk2, and downregulation of Cacna1d [23, 28–30].

Most strikingly, genes for OXPHOS were substantially upregulated by the HF, demonstrating enhanced oxidative metabolism in islets of animals receiving HF or high-carbohydrate diet. Moreover, the majority of enzymes for pyruvate metabolism and TCA cycle were significantly upregulated by the HF, suggesting an increased flux of fatty acid-derived acyl-CoA towards mitochondrial oxidation in the presence of dietary carbohydrates. Thus, increased availability of carbohydrates stimulates oxidative metabolism in islets, presumably by providing sufficient TCA intermediates in the mitochondrial matrix (anaplerosis).

Alterations in expression of OXPHOS genes has been regarded as a key change in the insulin-resistant state in human patients and animal models of type 2 diabetes [31–33]. Since OXPHOS is a major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, increased mitochondrial oxygen flux leads to increased formation of ROS [34–37]. ROS include highly reactive moieties, such as superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals, which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes [38, 39]. Consistent with elevated ROS production in HF islets, the gene expression of regulators of the cellular redox state, including catalase, glutathione peroxidase 1, peroxiredoxins and thioredoxin interacting protein, was increased, strongly implicating ROS in the early state of beta cell failure. Proteomic analysis of isolated islets may be used to further investigate the diet-induced alterations in OXPHOS gene expression and protein modifications in response to increased oxidative stress.

Among the most differentially expressed genes in response to the dietary intervention were the transcription factor Chrebp and the peptide hormone Cck. Interestingly, cholecystokinin mRNA, which was upregulated about tenfold by the HF, appears to be highly enriched in LCM islets. Recent evidence suggests that cholecystokinin acts as a proliferative signal on beta cells [28], implicating it in the compensatory hyperplasia of islet cells in the prediabetic state. ChREBP has been described as a transcriptional sensor for glucose in the liver, which becomes activated upon glucose stimulation and triggers production of lipogenic enzymes for conversion of glucose into fat [24]. We confirmed ChREBP protein production in islets by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4a–d). Moreover, Chrebp mRNA levels in islets and liver were comparable (Fig. 4e). Consistent with previous reports [24], HF-induced hyperglycaemia resulted in activation of ChREBP in the liver and subsequent induction of lipogenic enzymes, including acetyl-CoA carboxylase, fatty acid synthase, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 and liver-type pyruvate kinase (Fig. 4e and data not shown). Interestingly, in islets, ChREBP was considerably decreased in response to the diabetogenic HF, whereas transcription of ChREBP target genes was not affected, clearly indicating that in islets ChREBP controls different target genes than in the liver. In fact, a recent report demonstrated that ChREBP mediates glucose-induced expression of proapoptotic Txnip and induces H4 acetylation in beta cells, implicating a wider role of ChREBP beyond regulation of hepatic enzymes [40].

In summary, our data clearly demonstrate the critical role of dietary carbohydrates in the pathophysiology of HF-induced diabetes. LCM allows isolation of authentic pancreatic islet cells from their native tissue environment for genome-wide expression profiling. In islets, the diabetes-protective effect of a CHF diet correlates with reduced expression of genes for OXPHOS and antioxidants, suggesting a major contribution of ROS to diet-induced beta cell failure. Thus, our approach successfully identified candidate pathways and molecules that may play a role in the aetiology of type 2 diabetes.

Electronic supplementary materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 134 kb)

(PDF 255 kb)

(PDF 375 kb)

(PDF 144 kb)

(PDF 195 kb)

(PDF 33 kb)

(PDF 11 kb)

(PDF 94 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the European Union (EUGENE2, LSHM-CT-2004-512013; SysProt, LSHG-CT-2006-37457), the Gates Cambridge Trust and the UK Medical Research Council’s Centre for Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders (MRC-CORD).

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- CHF

Carbohydrate-free high-fat diet

- ChREBP

Carbohydrate-responsive element binding protein

- DGI

Diabetes Genetics Initiative

- GWA

Genome-wide association study

- HF

High-fat diet

- LCM

Laser capture microdissection

- NZO, NZL

New Zealand obese mouse strains

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- WTCCC

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium

Footnotes

T. Dreja and Z. Jovanovic contributed equally to this work, and H. Al-Hasani and G. S. H. Yeo also contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

G. S. H. Yeo, Email: gshy2@cam.ac.uk

H. Al-Hasani, Email: al-hasani@dife.de

References

- 1.Doria A, Patti ME, Kahn CR. The emerging genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2008;8:186–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt C, Gonzaludo NP, Strunk S, et al. A meta-analysis of QTL for diabetes-related traits in rodents. Physiol Genomics. 2008;34:42–53. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00267.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wuschke S, Dahm S, Schmidt C, Joost HG, Al-Hasani H. A meta-analysis of quantitative trait loci associated with body weight and adiposity in mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:829–841. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yki-Jarvinen H. Glucose toxicity. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:415–431. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-3-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poitout V, Robertson RP. Glucolipotoxicity: fuel excess and beta-cell dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:351–366. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ, van Haeften TW. Type 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy. Lancet. 2005;365:1333–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn YB, Xu G, Marselli L, et al. Changes in gene expression in beta cells after islet isolation and transplantation using laser-capture microdissection. Diabetologia. 2007;50:334–342. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0536-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marselli L, Thorne J, Ahn YB, et al. Gene expression of purified beta-cell tissue obtained from human pancreas with laser capture microdissection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1046–1053. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruan H, Zarnowski MJ, Cushman SW, Lodish HF. Standard isolation of primary adipose cells from mouse epididymal fat pads induces inflammatory mediators and down-regulates adipocyte genes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47585–47593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jurgens HS, Neschen S, Ortmann S, et al. Development of diabetes in obese, insulin-resistant mice: essential role of dietary carbohydrate in beta cell destruction. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1481–1489. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Z, Irizarry RA, Gentleman R, Martinez-Murillo F, Spencer F. A model based background adjustment for oligonucleotide expression arrays. JASA. 2004;99:909–917. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai M, Wang P, Boyd AD, et al. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e175. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HR KE, Kowald A, Wierling C, Lehrach H. Systems biology in practice. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cameron DP, Opat F, Insch S. Studies of immunoreactive insulin secretion in NZO mice in vivo. Diabetologia. 1974;10(Suppl):649–654. doi: 10.1007/BF01221999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saxena R, Voight BF, Lyssenko V, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science. 2007;316:1331–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeggini E, Weedon MN, Lindgren CM, et al. Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science. 2007;316:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1142364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, et al. A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science. 2007;316:1341–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1142382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Namkung Y, Skrypnyk N, Jeong MJ, et al. Requirement for the L-type Ca(2+) channel alpha(1D) subunit in postnatal pancreatic beta cell generation. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1015–1022. doi: 10.1172/JCI13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Postic C, Dentin R, Denechaud PD, Girard J. ChREBP, a transcriptional regulator of glucose and lipid metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:179–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leiter EH, Coleman DL, Ingram DK, Reynolds MA. Influence of dietary carbohydrate on the induction of diabetes in C57BL/KsJ-db/db diabetes mice. J Nutr. 1983;113:184–195. doi: 10.1093/jn/113.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plum L, Giesen K, Kluge R, et al. Characterisation of the mouse diabetes susceptibilty locus Nidd/SJL: islet cell destruction, interaction with the obesity QTL Nob1, and effect of dietary fat. Diabetologia. 2002;45:823–830. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0796-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plum L, Kluge R, Giesen K, Altmuller J, Ortlepp JR, Joost HG. Type 2 diabetes-like hyperglycemia in a backcross model of NZO and SJL mice: characterization of a susceptibility locus on chromosome 4 and its relation with obesity. Diabetes. 2000;49:1590–1596. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavine JA, Raess PW, Davis DB, et al. Overexpression of pre-pro-cholecystokinin stimulates beta-cell proliferation in mouse and human islets with retention of islet function. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2716–2728. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Akpinar P, Kuwajima S, Krutzfeldt J, Stoffel M. Tmem27: a cleaved and shed plasma membrane protein that stimulates pancreatic beta cell proliferation. Cell Metab. 2005;2:385–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Saxena G, Mungrue IN, Lusis AJ, Shalev A. Thioredoxin-interacting protein: a critical link between glucose toxicity and beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes. 2008;57:938–944. doi: 10.2337/db07-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sparks LM, Xie H, Koza RA, et al. A high-fat diet coordinately downregulates genes required for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2005;54:1926–1933. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Misu H, Takamura T, Matsuzawa N, et al. Genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately upregulated with fasting hyperglycaemia in livers of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:268–277. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takamura T, Misu H, Matsuzawa-Nagata N, et al. Obesity upregulates genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation in livers of diabetic patients. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2601–2609. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonawitz ND, Chatenay-Lapointe M, Pan Y, Shadel GS. Reduced TOR signaling extends chronological life span via increased respiration and upregulation of mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Metab. 2007;5:265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Houstis N, Rosen ED, Lander ES. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006;440:944–948. doi: 10.1038/nature04634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osmundsen H, Bremer J, Pedersen JI. Metabolic aspects of peroxisomal beta-oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1085:141–158. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(91)90089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urakawa H, Katsuki A, Sumida Y, et al. Oxidative stress is associated with adiposity and insulin resistance in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4673–4676. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cha-Molstad H, Saxena G, Chen J, Shalev A. Glucose-stimulated expression of TXNIP is mediated by CHREBP, p300 and histone H4 acetylation in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16898–16905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 134 kb)

(PDF 255 kb)

(PDF 375 kb)

(PDF 144 kb)

(PDF 195 kb)

(PDF 33 kb)

(PDF 11 kb)

(PDF 94 kb)