Abstract

Development of therapies to treat visual system dystrophies resulting from the degeneration of rod and cone photoreceptors may directly benefit from studies of animal models, such as the zebrafish, that display continuous retinal neurogenesis and the capacity for injury-induced regeneration. Previous studies of retinal regeneration in fish have been conducted on adult animals and have relied on methods that cause acute damage to both rods and cones, as well as other retinal cell types. We report here the use of a genetic approach to study progenitor cell responses to photoreceptor degeneration in the larval and adult zebrafish retina. We have compared the responses to selective rod or cone degeneration using, respectively, the XOPS-mCFP transgenic line and zebrafish with a null mutation in the pde6c gene. Notably, rod degeneration induces increased proliferation of progenitors in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and is not associated with proliferation or reactive gliosis in the inner nuclear layer (INL). Molecular characterization of the rod progenitor cells demonstrated that they are committed to the rod photoreceptor fate while they are still mitotic. In contrast, cone degeneration induces both Müller cell proliferation and reactive gliosis, with little change in proliferation in the ONL. We found that in both lines, proliferative responses to photoreceptor degeneration can be observed as 7 days post fertilization (dpf). These two genetic models therefore offer new opportunities for investigating the molecular mechanisms of selective degeneration and regeneration of rods and cones.

Keywords: genetics, zebrafish, retina, photoreceptors, regeneration

INTRODUCTION

Inherited photoreceptor dystrophies comprise a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders resulting in photoreceptor cell loss and blindness, for which there is currently no cure. Whereas diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa initially involve the selective degeneration of only rod photoreceptors, eventually leading to the loss of cones, other disorders such as achromatopsia result from the selective loss of cone photoreceptors (RetNet: http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/Retnet/). One potential therapeutic approach that is being intensively investigated involves retinal stem or progenitor cell transplantation, which aims to repopulate the diseased retina before the onset of photoreceptor degeneration. It is generally believed that regeneration in the mature retina will recapitulate the program of photoreceptor development; however, the details of this developmental program as well as the molecular signals that promote photoreceptor cell replacement and integration into an existing circuit remain to be elucidated. One valuable approach to better understand the mechanisms of tissue regeneration has been to study model organisms in which ongoing neurogenesis is a natural consequence of continued growth during adulthood.

The zebrafish, a diurnal animal, is well suited to studies of retinal degeneration, due to the large numbers of cones as well as rods, ease of genetic manipulation, and well developed genomic resources. Of particular importance for this study, in the mature zebrafish new retinal neurons, including photoreceptors, are generated throughout the life of the fish. Two mechanisms are primarily responsible for this continued neurogenesis. Most retinal neurons, including photoreceptors, are added to the existing retina from a population of mitotic progenitor cells that reside in the ciliary marginal zone (CMZ) at the retinal periphery. Additionally, new rod photoreceptors are produced in the central retina from a distinct population of mitotic cells, the rod progenitors (Johns and Fernald, 1981; Otteson and Hitchcock, 2003). Though relatively rare in number, rod progenitor cells can be identified based on their laminar position (at the base of the outer nuclear layer) (ONL), adjacent to the outer plexiform layer), their rounded morphology, and their expression of markers of proliferation such as proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) or incorporation of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU). However, few specific markers of rod progenitor cells have been identified. Rod progenitor proliferation is thought to be stimulated in the wild type retina by changes in rod density due to the retinal stretching that accompanies eye growth (Raymond et al., 1988); the growth-associated mitotic activity of the rod progenitors may be regulated by the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-I axis (Mack and Fernald, 1993; Otteson et al., 2002; Zygar et al., 2005). The rod progenitors themselves arise from slowly dividing stem cells in the inner nuclear layer (INL), which produce radially arranged clusters of fusiform-shaped cells that migrate from the INL to the ONL (Raymond and Rivlin, 1987; Julian et al., 1998; Otteson et al., 2001). It has recently been shown that in the wild type retina, a subset of neurogenic Müller glia are the source of these INL stem cells (Bernardos et al., 2007).

In response to retinal injury, the zebrafish, like other teleost fish, is able to regenerate multiple classes of retinal neurons (Otteson and Hitchcock, 2003; Fadool, 2003b). Work from several laboratories has shown that cells with properties of Müller glia are involved in this response, giving rise to the “neurogenic clusters” of proliferative cells observed in regenerating fish retinas (Kassen et al., 2007; Yurco and Cameron, 2005; Fausett and Goldman, 2006; Raymond et al., 2006; Bernardos et al., 2007; Fimbel et al., 2007). Depending on the site and nature of the damage, these clusters can regenerate neurons of the inner retina (Goldman, 2006; Fimbel et al., 2007), or the photoreceptors (Wu et al., 2001; Raymond et al., 2006; Bernardos et al., 2007).

Previous studies of photoreceptor regeneration in fish have relied on methods that cause acute retinal damage, such as intense light exposure (Vihtelic and Hyde, 2000; Bernardos et al., 2007), laser ablation (Braisted et al., 1994; Wu et al., 2001), thermal lesioning (Raymond et al., 2006), mechanical injury (Cameron, 2000; Fausett and Goldman, 2006), or application of metabolic poisons (Braisted and Raymond, 1992). One limitation of these techniques is that they do not selectively target just the rods or the cones, preventing dissection of any differential responses to degeneration between the two photoreceptor subtypes. One study reported that low doses of tunicamycin (an antibiotic) preferentially kill rod photoreceptors (Braisted and Raymond, 1993); however, other groups have reported that tunicamycin causes destruction of both rods and cones at lower doses and widespread retinal toxicity at higher doses (Fliesler et al., 1984; Anderson et al., 1988; Negishi et al., 1991). Furthermore, in addition to killing both rods and cones, these acute methods frequently result in focal lesions and almost certainly kill or damage cells of the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE). Finally, these treatments have all been applied to adult fish, with little or no investigation of the developmental onset of the retina’s regenerative capacity [which in other model organisms such as the chicken is limited to a narrow window of time following hatching (Fischer, 2005)]. To address these issues, a more precise genetic model system in which to study the selective regeneration of rods and cones, both in adult and in developing zebrafish, would be useful.

Our laboratory has characterized a transgenic line of zebrafish, the XOPS-mCFP line, which experiences selective degeneration of the rod photoreceptor cells due to the toxic effect of a rod-targeted fluorescent reporter gene (Morris et al., 2005). This rod degeneration results in a loss of rod-mediated electrophysiological responses, but does not cause any secondary cone pathology (Morris et al., 2005 and Supplementary Fig. 1). It is, however, accompanied by a significant increase in PCNA immunolabeling of rod progenitor cells, which we propose reflects an ongoing, elevated cycle of rod photoreceptor birth and death. Therefore, this line offers a unique opportunity to study the rod progenitors in more detail. Similarly, to examine the regenerative response to cone cell death, we have made use of a newly characterized zebrafish model of cone photoreceptor degeneration caused by a mutation in the pde6c gene (Stearns et al., 2007). This line displays cone photoreceptor degeneration and an absence of cone-mediated electrophysiological responses. However, few if any rod photoreceptors of adult pde6cw59 mutants degenerate secondarily to cone loss, nor have we detected loss of other retinal cell types examined thus far (Supplementary Fig. 2). Using these two genetic models we have been able to distinguish differences in the regenerative response to the selective loss of rods versus cones. We show that rod progenitors are molecularly distinct from other progenitor cells, even in the INL. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the proliferative response to both rod or cone degeneration can be observed as early as 7 dpf, a stage that precedes the appearance of rod progenitor cell proliferation in the wild type zebrafish retina. Finally, we show that rod progenitor proliferation, like the proliferation observed in the INL following cone degeneration, is truly in response to rod cell death rather than to a decrease in rod density. Therefore, our data support a model that involves distinct rod and cone regeneration pathways in the zebrafish retina.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Husbandry

Rearing, breeding, and staging of zebrafish (Danio rerio) were performed according to standard methods (Westerfield, 1995). The Tg(XRho:gap43-CFP)q13 line, referred to here as the XOPS-mCFP line, and the XOPS-GFP transgenic line have been described previously (Fadool, 2003a; Morris et al., 2005). The pde6cw59 mutant was isolated in an ENU-mutagenesis screen on the basis of its lack of an optokinetic response (Stearns et al., 2007). The lor mutant was isolated in an ENU-mutagenesis screen on the basis of its increased immunolabeling with rod-specific antibodies (Alvarez-Delfin et al., in preparation). For some experiments zebrafish were placed in fish water containing 0.5% BrdU (Sigma, St. Louis) for 2–16 h.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunolabeling of larval and adult retinal cryosections was performed as previously described (Morris et al., 2005). Images were obtained using either a Zeiss Axiovert fluorescence microscope or a Zeiss 510 confocal microscope out-fitted with a 40× C-Apochromat water immersion objective (N.A. 1.2).

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-BrdU (mouse, 1:500, Sigma); anti-PCNA (mouse, 1:100, Santa Cruz), 1D1, which recognizes rods (mouse, 1:50; Hyatt et al., 1996); 4C12, which also labels rods (mouse, 1:100; Fadool and Linser, unpublished); Zpr-1, which recognizes red-green double cones (mouse, 1:20, Oregon monoclonal bank); anti-PKCα, a marker of bipolar cells (rabbit, 1:100, Santa Cruz); anti-HuC/D, which labels ganglion cells and amacrine cells (mouse, 1:20, Invitrogen); anti-Nr2e3 (rabbit, 1:100; Chen et al., 2005; a generous gift from J. Nathans, Baltimore, MD); Zrf-1, which recognizes Müller glia (mouse, 1:10, Oregon monoclonal bank); and anti-carbonic anhydrase (CAZ), which also labels Müller glia (rabbit, 1:100; Peterson et al., 2001). Alexa fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were all used at a dilution of 1:200. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; 1:10,000, Sigma) to visualize cell nuclei.

Terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) was performed on retinal cryosections using the ApopTag Red In Situ Apoptosis Detection kit (Chemicon) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell Counts

To quantify the average number of BrdU+ cells in the ONL and INL of wild type, XOPS-mCFP, and pde6cw59 retinas, 10 μm cryosections were immunolabeled with anti-BrdU, counterstained with DAPI and imaged on a fluorescent microscope. The total number of BrdU+ cells visible in the ONL or INL of each retina on the section was counted. Sections were excluded from analysis if all nuclear and plexiform layers were not clearly visible or if the CMZ was not BrdU-positive. The following numbers of animals and sections were analyzed: wild type: 7 dpf, 3 animals, 28 sections; 10 dpf, 2 animals, 15 sections; 15 dpf, 4 animals, 24 sections for the ONL counts and 5 animals, 32 sections for the INL cell counts; XOPS-mCFP: 7 dpf, 4 animals, 29 sections; 10 dpf, 6 animals, 46 sections; 15 dpf, 5 animals, 53 sections for the ONL cell counts and 9 animals, 65 sections for the INL cell counts; pde6cw59 wt sibling: 7 dpf, 13 animals, 8 sections; 10 dpf, 10 animals, 20 sections; 15 dpf, 10 animals, 10 sections; pde6cw59 mutant: 7 dpf: 12 animals, 10 sections; 10 dpf: 4 animals, 12 sections; 15 dpf: 3 animals, 8 sections. Because the numbers of BrdU+ cells were often very low or zero for a section, the data were log transformed, and the significance of the results was assessed on the log transformed data at each age using a Student’s t test for two independent samples. For each experiment transgenic or mutant animals were compared with wild type siblings from the same clutch to avoid introducing artifactual variation.

In Situ Hybridization

Retinal cryosections were prepared as described above. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense probes were prepared by in vitro transcription with T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase (Roche) according the manufacturer’s instructions. Probes were hybridized to the sections overnight at 58°C at final concentration of 2 ng/μL. The sections were washed and incubated with anti-DIG-AP overnight at 4°C. Sections were then incubated in staining buffer containing NBT and BCIP for 15 min to 4 h at room temperature and imaged with bright field optics on a Zeiss Axoivert fluorescent microscope using the 40× objective.

Mosaic Analysis

Genetic mosaic animals were produced by cell transplantation as described previously (Link et al., 2000). Transplants were conducted at the blastula (1000-cell) stage. Donors were injected with lysine-fixable rhodamine-dextran dye to mark the transplanted cells. The transplants were analyzed at 24 hpf for successful incorporation of donor cells into the developing eye. The transplants were raised until 10 dpf and then prepared for cryosectioning and immunolabeling as described above.

RESULTS

Selective Degeneration of Cone Photoreceptors Induces an Increase in Progenitor Cell Proliferation in the INL and Müller Cell Activation

As mentioned above, previous studies of photoreceptor regeneration in teleost fish have largely relied on acute methods that kill rods and cones, and which also probably damage the RPE (Braisted et al., 1994; Vihtelic and Hyde, 2000; Wu et al., 2001; Raymond et al., 2006; Bernardos et al., 2007). While all of the studies have demonstrated an increase in proliferation in the INL in response to the damage, it is unclear whether this response was caused by the death of the rods, the cones, or by other collateral damage. To address this question, we have compared and contrasted cell proliferation in the pde6cw59 mutant, which harbors a mutation in the gene for the zebrafish cone cGMP-phosphodiesterase (Stearns et al., 2007), to proliferation in the XOPS-mCFP transgenic line, which carries a fluorescent reporter gene that is toxic to rod photoreceptors and which is associated with an increase in cell proliferation in the ONL (Morris et al., 2005 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

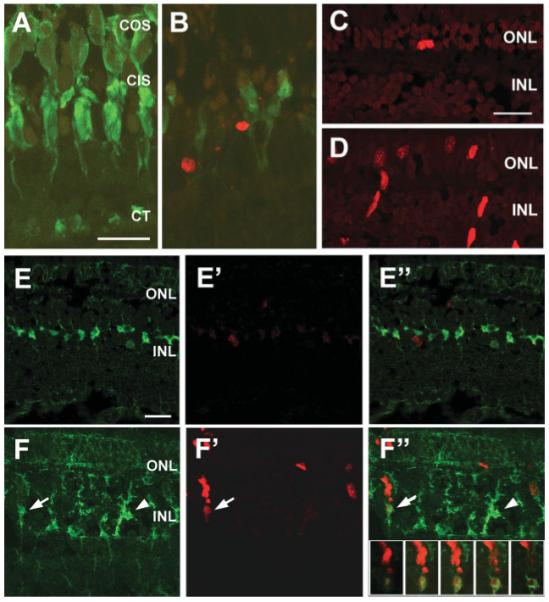

Homozygous pde6cw59 animals experience cone photoreceptor degeneration [Fig. 1(B) and Supplementary Fig. 2] and display an absence of cone-mediated electrophysiological responses. However, few if any rod photoreceptors of adult pde6cw59 mutants degenerate as a secondary effect of cone loss, and we have not detected loss of any other retinal cell type examined thus far (Supplementary Fig. 2). To determine whether there is an increase in photoreceptor progenitor cell proliferation in mutants, homozygous pde6cw59 animals were exposed to BrdU for 4 h prior to dissection. Subsequently, retinal cryosections were immunolabeled with anti-BrdU and with an antibody to zebrafish carbonic anhydrase (CAZ), which labels retinal Müller cells (Peterson et al., 2001). In adult pde6cw59 mutants, in addition to a qualitative increase in BrdU+ cells at the base of the ONL compared with the wild type siblings [Fig. 1(C,D)], we also observed an increase in BrdU+ cells in the INL [Fig. 1(D)]. The INL BrdU+ cells were often located in radially arrayed columns, very similar to the neurogenic clusters that have been described by others following acute retinal damage to the zebrafish retina. Importantly, some of the BrdU+ cells at the base of the INL clusters colocalized with CAZ immunoreactivity [Fig. 1(F”)], suggesting that at least some of the cells with properties of Müller glia had reentered the cell cycle. Additionally, immunolabeling with CAZ revealed that the morphology of other Müller cells was altered in the pde6cw59 mutant. Whereas in wild type siblings, Müller cell bodies were compact and horizontally aligned in the INL (Fig. 1(E)], in pde6cw59 mutants the Müller cells were less well organized and displayed a ”tree-trunk“ morphology [Fig. 1(F)]. In contrast, no change in Müller cell morphology is observed in response to selective degeneration of the rods in the XOPS-mCFP line (Morris et al. 2005 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Together, these data indicate that the selective degeneration of cones induces a proliferative response in the INL, and this response involves a subset of Müller glial cells, similar to what has been described previously for models of acute photoreceptor damage.

Figure 1.

Cell proliferation and Müller glial activation in the pde6cw59 mutant. (A-B) Retinal cryosections from wild type (A) and pde6cw59 mutant (B) 60 dpf adults were analyzed by TUNEL-labeling (red) and by immunolabeling for the double-cones (green). The pde6cw59 mutant retina displays a lack of mature cones and an increase in TUNEL+ cells in the ONL. COS, cone outer segments; CIS, cone inner segments; CT, cone terminals. (C-D) BrdU immunolabeling of retinal cryosections from wild type (C) and pde6cw59 adults (D). There is an increase in BrdU+ cells (red) in both the ONL and the INL of pde6cw59 mutants. (E-F) Immunolabeling of retinal cryosections from wild type (E-E”) and pde6cw59 (F-F”) adults with BrdU (red) and the Müller cell marker carbonic anhydrase (CAZ, green). Merged images are shown in (E”,F”). In the pde6cw59 mutant, Müller glia have a “tree trunk” morphology (arrowhead) indicative of reactive gliosis. In some clusters of BrdU+ cells, the basal-most BrdU+ cell colocalizes with Müller cell immunoreactivity (arrow). The inset in F” shows a series of confocal optical slices through the cell cluster indicated by the arrow. All scale bars, 20 μm.

Molecular Characterization of Rod Progenitor Cells

Our data from the pde6cw59 mutant concurs with previous studies of light-damaged photoreceptors, which showed that Müller glia can be stimulated to proliferate in response to acute photoreceptor damage. Those studies demonstrated that in response to photoreceptor cell death, Müller glia express numerous developmentally regulated genes (Raymond et al., 2006; Kassen et al., 2007). In contrast, rod degeneration in the XOPS-mCFP line is only associated with an increase in proliferation of the rod progenitor cells (Morris et al., 2005 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, the increased proliferation of the rod progenitors in the XOPS-mCFP line offers an excellent opportunity to molecularly characterize this population of cells in more detail.

We examined, by in situ hybridization of wild type and XOPS-mCFP adult retinal sections, the expression patterns of various markers of cell proliferation and of the photoreceptor lineage. In situ hybridization with a probe for rhodopsin mRNA (rho) clearly demonstrated the loss of rho-expressing cells in the ONL of XOPS-mCFP retinas [Fig. 2(A,B)]. In contrast, an increase in expression of cyclin D1 and PCNA [Fig. 2(C-F)], markers of mitotically active cells, was observed at the base of the ONL in XOPS-mCFP retinas when compared to wild type, in a position consistent with the location of the rod progenitors. We also observed a similar increase in the expression of neuroD, a bHLH transcription factor expressed in rod progenitor cells, nascent rod and cone photoreceptors, and amacrine cells, but not in mature photoreceptors (Hitchcock and Kakuk-Atkins, 2004; Ochocinska and Hitchcock, 2007) [Fig. 2(H)]. The expression of crx, a homeobox-containing transcription factor associated with photoreceptor differentiation, was also observed in presumptive rod progenitors in XOPS-mCFP retinas (data not shown). However, it was not possible to determine whether expression of crx was elevated relative to wild type retinas because crx is also present in mature cone photoreceptors and in cells of the INL (Liu et al., 2001). Genes of the Notch-Delta pathway have also been implicated in the regenerative response to rod and cone damage in zebrafish (Wu et al., 2001; Raymond et al., 2006). Surprisingly, we were not able to detect expression of Notch1a, Notch3, DeltaC, or DeltaB in the ONL by in situ hybridization methods (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Molecular characterization of zebrafish rod progenitor cells. In situ hybridization of retinal cryosections from wild type (left column) and XOPS-mCFP (right column) adults (22 months post fertilization) with probes for the indicated genes. Black bars indicate the position of the rod photoreceptor nuclei for each section. Note the decrease in rhodopsin expression (B) as well as the decrease in thickness of the rod nuclear layer in the XOPS-mCFP retinas. There is an increase in pre-sumptive rod progenitor cells expressing proliferation genes (cyclin D1, PCNA) and a gene associated with the photoreceptor lineage (neuroD) in XOPS-mCFP retinas. Rho, rhodopsin; cycD1, cyclin D1; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Nr2e3 Expression is Specific for Rod Progenitors in the INL and ONL

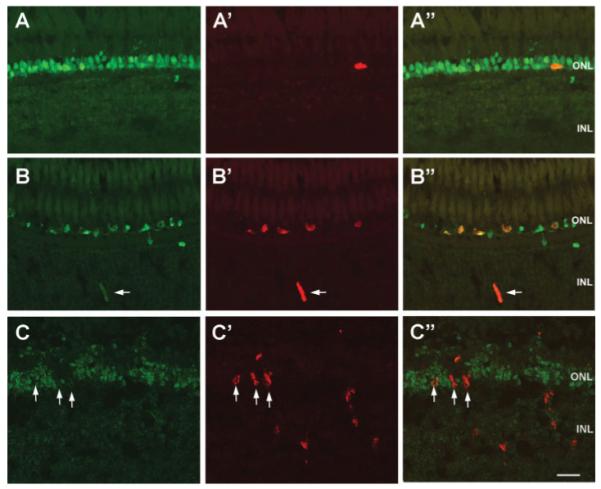

Because we did not observe expression of genes typically associated with multipotent retinal progenitors (i.e., Notch and Delta genes), but we did detect increased expression of cell cycle genes and neuroD in the region of the rod progenitors, we took advantage of the increase in rod progenitor proliferation in XOPS-mCFP animals to determine whether rod progenitors coexpress markers of differentiating rod photoreceptors. Nr2e3 is a transcription factor that in rodents and humans is expressed exclusively in postmitotic rod precursor cells and in mature rods (Mears et al., 2001; Swain et al., 2001; Bumsted O’Brien et al., 2004; Akimoto et al., 2006; Cheng et al., 2004, 2006). In zebrafish, Nr2e3 is expressed transiently in developing rods and cones in the embryonic retina, and exclusively in rods in the mature retina (Chen et al., 2005). We exposed wild type and XOPS-mCFP adult zebrafish to a short, two-hour pulse of BrdU (to specifically label only cells in S phase and prior to mitosis), and immunolabeled retinal sections with antibodies to BrdU and to zebrafish Nr2e3 (Chen et al., 2005). In mature, wild type retinas, Nr2e3 immunofluorescence was predominantly localized to the rows of rod nuclei in the ONL, but was not observed in cones [Fig. 3(A)]. In XOPS-mCFP retinas, we observed numerous Nr2e3+ cells that were scattered across a single layer of the ONL [Fig. 3(B)]. We also observed numerous BrdU+ cells in the ONL of XOPS-mCFP retinas, as described above. Interestingly, we found that in both wild type and XOPS-mCFP retinas, every BrdU+ rod progenitor cell was also positive for Nr2e3 [Fig. 3(A”,B”)]. Furthermore, we occasionally detected colocalization of BrdU and Nr2e3 in spindle-shaped progenitor cells located in the INL [Fig. 3(B)]. These data suggest that, in contrast to the mammalian rod photoreceptor pathway, mitotic rod progenitor cells in mature zebrafish express rod specification factors prior to exiting the cell cycle.

Figure 3.

Expression of Nr2e3 in wild type, XOPS-mCFP, and pde6cw59 retinas. Retinal cryosections from wild type (A-A”), XOPS-mCFP (B-B”), and pde6cw59 adults immunolabled for Nr2e3 (green) and BrdU (red). In the wild type retina, a single rod progenitor cell (arrow) is also Nr2e3+. All of the BrdU+ rod progenitor cells in the XOPS-mCFP retina, including a progenitor cell in the INL (arrow) are also Nr2e3+. None of the BrdU+ cells in the INL and the ONL (arrows) of the pde6cw59 mutant are positive for Nr2e3. Scale bar, 20 μm.

We also immunolabeled retinal sections from BrdU-treated adult pde6cw59 mutants with anti-Nr2e3. Nr2e3 immunoreactivity was observed only in the rod photoreceptor layer of pde6cw59 mutants [Fig. 3(C)]. The labeling appeared slightly less well organized than in wild type animals, possibly due to the cone cell death that had occurred. Interestingly, the BrdU+ cells in the INL and even many BrdU+ cells in the ONL did not colabel with the Nr2e3 antibody [Fig. 3(C”)]. These results suggest that although both rod and cone photoreceptor progenitor cells in the INL may arise from the same population of stem cells, those that are fated to become rods must segregate fairly early into an independent lineage.

Developmental Onset of the Proliferative Response to Rod or Cone Degeneration

Our results suggest that proliferation in response to rod death differs from proliferation in response to cone death. Rod degeneration in XOPS-mCFP animals and cone degeneration in pde6cw59 mutants occur during embryogenesis, soon after photoreceptor differentiation (Morris et al., 2005; Stearns et al., 2007). To determine the developmental onset of regenerative responses to rod or cone degeneration, wild type, transgenic, and mutant zebrafish larvae were incubated overnight in fish water containing BrdU. This method was sufficient to label the rod progenitor cells in the ONL, and to label a small number of proliferative progenitors in the INL, while simultaneously allowing for a temporal comparison of the onset of mitotic activity. Because the stem cells of the INL divide more slowly than the rod progenitors of the ONL, it is likely that we cannot detect all of the dividing cells by overnight BrdU exposure. However, limiting the incubation period to overnight reduces the chances that cells will progress through more than one round of cell division during the labeling period (Johns, 1982), or that labeled cells will have exited the cell cycle, terminally differentiated, and degenerated. It is worth noting that because rod progenitor mitotic activity is also related to the growth rate of the animal, numbers of mitotic rod progenitor cells can vary greatly from clutch to clutch. Therefore, for each experiment transgenic or mutant animals were compared with wild type siblings from the same clutch to avoid introducing artifactual variation.

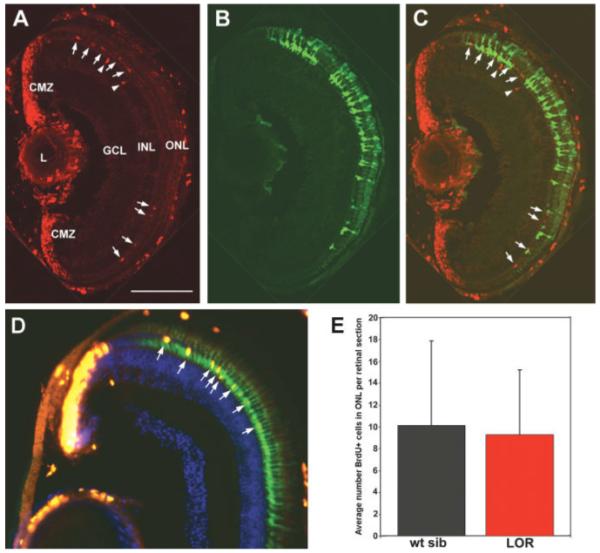

In wild type zebrafish, numerous BrdU-labeled cells were observed in the CMZ at every time point tested between 5 and 15 dpf. However, prior to 15 dpf, the majority of wild type retinal sections contained no BrdU+ cells in ONL [Fig. 4(A)], although this is a period marked by an approximate three-fold increase in the number of rhodopsin-positive cells (Fadool, 2003a). Fewer than 25% of wild type retinal sections contained one or two BrdU+ cells in the ONL at 7 and 10 dpf, with an overall average of one ONL BrdU+ cell every three sections, and one ONL BrdU+ cell every 15 sections, respectively [Fig. 5(A,B)]. In contrast, over 50% of retinal sections from XOPS-mCFP animals contained three or more BrdU+ rod progenitor cells in the ONL as early as 7 dpf [Fig. 5(A)], with a maximum of 8 and an overall average of 3.4 BrdU+ cells per retinal section in the ONL. The BrdU-labeled rod progenitors in XOPS-mCFP retinas were clustered in the dorsal region of the ONL at early stages [Fig. 4(B)], an area of greater rod density in older juveniles and adults (Fadool, 2003a; Vihtelic et al., 2006), although by 15 dpf the rod progenitors were detected throughout the central retina as well [Fig. 4(E)]. The number of rod progenitors in the ONL was significantly greater in XOPS-mCFP retinas than in wild type retinas at each time point tested [Fig. 5(A-C)]. Interestingly, no significant increase in BrdU+ cells was observed in the INL of XOPS-mCFP retinas when compared to wild type controls at any stage [compare Figs. 4(G,H); Fig. 5(D-F)]. Taken together, these data indicate that rod progenitor proliferation can be stimulated as early as 7 dpf in response to rod degeneration; however, in the absence of rod cell death, the rod progenitors or their antecedents are quiescent or dividing very slowly until some time between 10 and 15 dpf. Furthermore, it appears that the rod progenitors in the ONL are capable of responding to rod photoreceptor degeneration without increased activity of the stem or progenitor cells in the INL or the Müller cells (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Developmental maturation of rod progenitor and pde6cw59 proliferative responses. (A-F) Retinal cryosections from wild type (A, D), XOPS-mCFP (B, E), and pde6cw59 (C, F) zebrafish at 10 dpf (A-C) and 15 dpf (D-F). BrdU+ cells (red) are present in the dorsal outer nuclear layer (ONL) of XOPS-mCFP but not wild type or pde6cw59 retinas at 10 dpf and are more numerous than in wild type and pde6cw59 retinas at 15 dpf. Immunolabeling for rhodopsin (green) is included in D and E to demonstrate the lack of mature rods in the XOPS-mCFP line. (G-I) Retinal cryosections from 15 dpf wild type (G), XOPS-mCFP (H), and pde6cw59 (I) animals. While there are many BrdU+ cells (red) in the ONL of XOPS-mCFP retinas, there is no increase in BrdU labeling in the inner nuclear layer (INL). In contrast, a small but statistically significant increase is observed in the INL of pde6cw59 mutants. In A-I, nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue); for unknown reasons, the DAPI counterstain did not work well in pde6cw59 mutants and their wild type siblings. GCL, ganglion cell layer; L, lens. Scale bars: (A) 50 μm; (G) 20 μm.

Figure 5.

Quantification of BrdU+ cells in the ONL and INL of wild type, XOPS-mCFP, and pde6cw59 animals. Graphs in A-C show the percent of retinal sections at 7, 10, and 15 dpf for which the numbers of BrdU+ cells in the ONL, indicated on the x-axis, were observed. The inset shows the average number of BrdU+ cells in the ONL per retinal section for each group. Graphs in D-F show the percent of retinal sections at 7, 10, and 15 dpf for which the numbers of BrdU+ cells in the INL, indicated on the x-axis, were observed. The inset shows the average number of BrdU+ cells in the INL per retinal section for each group. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between wild type and XOPS-mCFP or wild type and pde6cw59 (student’s t-test calculated on log-transformed data; *: p < 0.005, **: p < 0.001).

In contrast to the XOPS-mCFP line, in the pde6cw59 mutants we did observe an increase in proliferation in the INL at every age relative to wild type siblings [Figs. 4(C,F,I) and 5(D-F)]. Although the overall numbers of BrdU+ cells in the INL were small, the changes in distribution were very consistent. Interestingly, larval pde6cw59 mutants did not display a robust or consistent increase in BrdU-labeled cells in the ONL relative to their wild type siblings [Figs. 4(C,F,I) and 5(A-C)]. Taken together, these data suggest that even at the larval stage, there is a segregation in the regenerative response to the death of rods versus cones.

Rod Progenitor Proliferation is not Inhibited by the Presence of Mature Rod Photoreceptors

In wild type fish, new rod photoreceptors are continually added to the central retina to maintain a constant density as the retina is stretched within the growing eye cup (Johns and Easter, 1977; Kock, 1982). Therefore, it is possible that the increase in rod progenitor proliferation observed in XOPS-mCFP animals results from a growth-associated mechanism that senses the decreased density of mature rods rather than from a bona fide regenerative response.

This hypothesis was tested in two ways. First, we performed genetic chimera analysis, using XOPS-mCFP animals as hosts, and XOPS-GFP animals (Fadool, 2003a) as donors, to determine if the presence of healthy rods in a XOPS-mCFP retina would cause a reduction in rod progenitor proliferation in the vicinity of the mature rods. In the XOPS-GFP line, rod photoreceptors express a GFP reporter gene, which causes no toxicity to the cells. By conducting cell transplantation experiments, we generated zebrafish with retinas that had a mixture of healthy and degenerating rod photoreceptors. Cells were transplanted from donor to host at the blastula stage, and animals that displayed significant incorporation of donor-derived cells into the eye (visualized by labeling donor cells with rhodamine-dextran) were raised to 10 dpf, a stage at which rod progenitor proliferation is not detectable in wild type retinas, but is significant in the dorsal region of XOPS-mCFP retinas [Fig. 4(B)]. The GFP reporter gene allowed identification of donor-derived rods, as the rhodamine-dextran label had diminished by 10 dpf. Chimeric animals were exposed to BrdU overnight prior to dissection.

Since XOPS-mCFP-containing rods die as soon as they differentiate, by 10 dpf there were no mature mCFP-positive rods in the retinas of chimeric animals. As expected, there were numerous BrdU+ cells in the ONL [Fig. 6(A-C)]. Retinas from chimeric animals also contained GFP-positive rods with a normal morphology that were derived from the XOPS-GFP donors. The numbers of GFP+ rods that were present in each chimeric retina varied considerably; some retinas contained a few GFP+ rods in a single cluster (data not shown), while others contained numerous GFP+ rods spread throughout the ONL [Fig. 6(B)]. Importantly, no difference was observed in the distribution of BrdU+ rod progenitors between XOPS-mCFP animals and chimeric animals [Fig. 6(A)]; even when considerable numbers of donor-derived rods were clustered in the dorsal retina, we observed BrdU+ rod progenitor cells among the GFP+ rods [Fig. 6(C)]. These results suggest that the presence of mature rods in the XOPS-mCFP retina was insufficient to suppress proliferation of the rod progenitor cells.

Figure 6.

Rod progenitor proliferation in genetic chimeric animals and the lor mutant. A-C: A representative retinal cryosection from a 10 dpf XOPS-mCFP host transplanted with XOPS-GFP donor cells at the blastula stage (see Methods for details). (A) BrdU immunolabeling demonstrates the presence of proliferative cells in the ciliary marginal zone (CMZ) and in the ONL (red). (B) Donor-derived GFP+ rods are located throughout the ONL of the host retina (green). (C) Merged image of (A) and (B). BrdU+ rod progenitor cells are clustered in the dorsal region of the ONL (arrows) and INL (arrowheads) among donor-derived GFP+ rods. L, lens; GCL, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) A representative retinal cryosection from a 15 dpf lor mutant. BrdU+ cells are shown in red (arrows); the rod photoreceptors display green fluorescence because the lor mutant was crossed onto the XOPS-GFP background. (E) Graph showing the average numbers of BrdU+ cells in the ONL of wild type siblings and lor mutants. There is no significant difference between the two.

To further rule out the hypothesis that rod progenitor proliferation in XOPS-mCFP animals is simply caused by a decreased density of healthy rods, we examined rod progenitor proliferation in lor mutant larvae, which display a dramatic increase in the numbers of rod photoreceptors relative to wild type animals (Alvarez-Delfin et al., in preparation, and Supplementary Fig. 4). We reasoned that if rod progenitor proliferation is regulated solely by density-dependent signaling mechanisms, there should be a decrease in BrdU+ cells in the ONL of lor retinas relative to their wild type siblings. However, when we examined lor retinal sections by BrdU immunolabeling, we observed no difference in the average number of BrdU+ cells at 15 dpf relative to wild type [Fig. 6(D,E)]. Taken together, these data suggest that the presence of dying rods is critical to eliciting the increase in rod progenitor proliferation observed in XOPS-mCFP animals. Furthermore, we propose that in wild type fish and in fish with excess rods, there is a basal level of rod progenitor proliferation that is independent of rod cell number.

DISCUSSION

Our approach to developing a system for studying photoreceptor cell regeneration has been to identify genetic models or transgenic lines that exhibit the selective loss of either rod or cone photoreceptors. Using this strategy we have made several unique observations regarding the zebrafish response to photoreceptor degeneration. First, we found that there are differences in the nature of the retina’s response to rod photoreceptor degeneration as opposed to cone degeneration or acute damage to the photoreceptor cell layer. These differences had been hinted at by previous work (Braisted and Raymond, 1993) but the present study has been able to test this idea directly, in the absence of acute damage to other cell types. Second, taking advantage of the increased number of proliferative rod progenitors in the XOPS-mCFP line, we observed that these mitotically active cells coexpress Nr2e3, a transcription factor associated with postmitotic rod precursors and differentiated rods in mammals. And third, we found that the regenerative response to rod or cone loss can be elicited as early as 7 dpf, a time when zebrafish larvae are visually active.

Our results demonstrate that selective degeneration of the rods does not involve Müller glial activation or stem cell proliferation in the INL, as was observed following cone degeneration (see Fig. 1) or in previous studies of photoreceptor damage (Wu et al., 2001; Yurco and Cameron, 2005; Fausett and Goldman, 2006; Raymond et al., 2006; Vihtelic et al., 2006; Bernardos et al., 2007). Rather, it is the rod progenitor cells of the ONL that respond to rod degeneration with an increase in mitotic activity. Our results suggest that, rather than existing solely to amplify the rod precursor pool in response to growth-associated changes in the ONL, the rod progenitor cells are capable of more complex interactions with the surrounding microenvironment.

Several studies have focused on the molecular characterization of the progenitor cells produced in the CMZ and in the INL in response to acute damage to rods and cones. Genes found to be expressed in INL progenitor cells in response to photoreceptor destruction include pax6, crx, N-cadherin, notch and delta genes, rx1, and vsx2/chx10 (Wu et al., 2001; Raymond et al., 2006; Bernardos et al., 2007). The expression of neuroD in the rod progenitor cells of the wild type teleost retina (Hitchcock and Kakuk-Atkins, 2004) has also been evaluated. However, none of the previous work has specifically examined rod progenitor cell gene expression in wild type versus degenerating retinas, due to the lack of a suitable genetic model of rod degeneration in zebrafish. We found that rod progenitors in wild type and XOPS-mCFP retinas express genes associated with the cell cycle (PCNA, cyclin D1) and with photoreceptor development (NeuroD, crx) but not genes associated with multipotent neural progenitors (e.g. notch and delta). We cannot rule out the possibility that the notch and delta genes we tested are expressed in rod progenitor cells at levels too low to be detected by in situ hybridization. Nevertheless, we favor an alternative hypothesis that notch and delta expression is restricted to multipotent cells, such as the neurogenic clusters of the INL, which are capable of regenerating numerous cell types, whereas the fate of the rod progenitors is already specified. This model is also supported by our results showing that rod progenitors (but not proliferative cells in pde6cw59 mutants) express Nr2e3, a rod determination factor that in mammals is expressed exclusively in post-mitotic differentiating rod photoreceptors. This result is particularly interesting in light of a recent report by MacLaren et al. (2006), which demonstrated that while both mitotic retinal progenitors and postmitotic rod precursors could differentiate into rhodopsin-expressing cells upon transplantation into a mouse model of retinal degeneration, only the postmitotic Nrl-positive cells could migrate to the appropriate position and integrate correctly into the host retina. While the successful integration of the postmitotic rod precursors is an exciting result, a similar approach to treating human photoreceptor degenerations is problematic, due to the low frequency of integration of postmitotic rod precursors and the difficulty of obtaining human fetal tissue at the correct ontogenetic stage. Our results have shown that in zebrafish, rod progenitors are both mitotic and express rod specification genes (e.g., Nr2e3, and presumably also Nrl). Therefore, a closer comparison of these two models may help to identify a set of genes whose expression confers both commitment to a photoreceptor cell fate and retention of mitotic activity.

One advantage of using genetic models of rod and cone degeneration is that progenitor responses can be studied over the animal’s lifetime, rather than during a discrete window following acute damage. When we examined the developmental onset of photoreceptor progenitor mitotic activity, we found that selective degeneration of the rods or the cones produced a significant proliferative response (in the ONL and the INL, respectively) as early as 7 dpf (see Fig. 5). It is interesting that rod progenitor cells were not detectable in wild type animals by BrdU immunolabeling before 10–15 dpf, but there was already a significant population of rod progenitors in the retinas of XOPS-mCFP animals at 7 dpf (Figs. 4 and 5). These results suggest that the significant numbers of rod photoreceptors that differentiate between 3 dpf and the time of appearance (by BrdU immunolabeling) of the first rod progenitors originate from a distinct pool of postmitotic precursor cells. However, because the XOPS-mCFP retinas displayed a much earlier onset of rod progenitor proliferation, perhaps a subset of embryonic rod progenitor cells is “set aside” early during development, but remains quiescent or divides very slowly until receiving the appropriate signals to increase proliferation. The presence of quiescent rod progenitors is consistent with the observation by Otteson et al. (2002) that a significant increase in rod progenitor mitotic activity can be stimulated in adult fish by intraperitoneal injection of growth hormone.

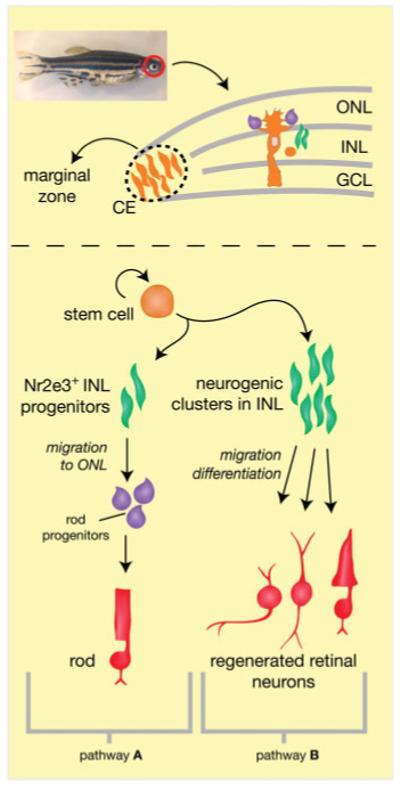

On the basis of previous work from others and on our current results, we propose a revised model for growth-associated and injury-induced neurogenesis in the zebrafish central retina, shown in Figure 7. In the wild type mature zebrafish retina, rod progenitor cells are generated from INL stem cells at a slow but detectable rate. The steady, baseline proliferation of the rod progenitors is principally influenced by the growth and health of the animal (Raymond et al., 1988; Mack and Fernald, 1993; Otteson et al., 2002; Zygar et al., 2005). We have shown here that rod photoreceptor cell death also selectively influences rod progenitor proliferation, and this response involves an increase in the numbers of rod progenitors in the ONL but not in the INL. Cones (as well as other retinal neurons) can also be generated from INL stem cells in response to photoreceptor damage or degeneration. In both cases, the stem cells of the INL are derived from a subset of Müller glia. On the basis of our results, we hypothesize that the Müller glia produce either two distinct stem cell populations (one that gives rise to the rod lineage and another that produces cones and inner retinal neurons), or that a single population of INL stem cells produces progenitor cells, a subset of which becomes committed shortly thereafter exclusively to the rod lineage. The hypothesis that rod and cone lineage commitment begins in the INL during photoreceptor regeneration is supported by data from the pde6cw59 mutant, where we found that although there were BrdU+ cells in the ONL of adult pde6cw59 mutant retinas, many of them (presumably the cone progenitors) were negative for Nr2e3 (see Fig. 3). Furthermore, although there is an increase in BrdU+ cells in the ONL of adult pde6cw59 mutants relative to wild type, mutant animals do not display an increase in the number of mature rod photoreceptors (Stearns et al., 2007), as might be expected if the progenitor cells of the ONL were equally capable of differentiating into either rods or cones.

Figure 7.

A model for persistent and injury- or degeneration-induced neurogenesis in the zebrafish central retina. In a wild type, uninjured retina, slowly dividing stem cells in the INL (orange), which are derived from a subset of neurogenic Müller glia, give rise to committed rod progenitor cells that express Nr2e3 (green, pathway A). The INL progenitors migrate to the ONL where they are further amplified as rod progenitor cells (purple) and differentiate into mature rods (red). In response to rod photoreceptor degeneration alone, the rod progenitors of pathway A increase their proliferation in the absence of proliferation in the INL. In response to degeneration of the cone photoreceptors, damage to both rods and cones, or death of other inner retinal neurons, Müller glia re-enter the cell cycle to produce neurogenic clusters (green, pathway B) in the INL that migrate to the correct laminar position and differentiate into multiple retinal cell types (red).

How is the teleost retinal microenvironment tuned to sense the loss of rods differently from the loss of cones? We do not currently know the precise mechanism that triggers proliferation of zebrafish retinal progenitors in response to photoreceptor degeneration. The progenitor cells may be responding to different sets of signaling molecules released by the rods or cones as they degenerate. Alternatively, since zebrafish cones establish synaptic connections earlier than rods, the proliferative response may be stimulated by abnormal synaptic transmission during development. It is unlikely that the regenerative response, at least for the rods, is triggered by a loss of cell–cell contact, because we did not observe a decrease in rod progenitor proliferation in the genetic chimeric animals or the lor mutants (see Fig. 6). One intriguing possibility is that the retina is responding to a loss or difference in metabolites produced by the visual cycle. Recent work in zebrafish has confirmed that an RPE65-independent pathway exists for the regeneration of cone 11-cis-retinal (Schonthaler et al., 2007). Furthermore, Mata et al. have proposed that such an alternate pathway for cone pigment regeneration would utilize enzymes expressed in Müller cells (Mata et al., 2002). If this is the case, perhaps the Müller cells are stimulated to respond to cone degeneration by alterations to cone retinoid metabolism, whereas the loss of the rods, which rely only on the RPE for their visual cycle, would not provoke this response. While an answer to this question awaits further experimentation, it would be interesting to determine whether there are qualitative differences in the INL of mammalian retinas experiencing rod degeneration versus cone degeneration. If so, this could indicate that therapeutic interventions for retinal degenerative diseases will need to be different depending on the primary photoreceptor affected. The genetic models of rod or cone degeneration that we have described in this study could provide much needed resources to identify the cellular processes associated with photoreceptor replacement and the incorporation of new neuronal elements into an existing retinal circuit.

Supplementary Material

Rods degenerate in XOPS-mCFP animals but other retinal cell types are unaffected. Retinal cryosections from wild type (A, C, E, G) and XOPS-mCFP (B, D, F, H) adults (6 months post fertilization) were immunolabeled with the following antibodies: 1D1 (A-B), which labels rhodopsin; Zpr-1 (C, D), which labels the double-cones; PKC-α (E, F) which labels bipolar cells; and Hu-C/D (G, H) which labels ganglion cells and amacrine cells. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Cones degenerate in pde6cw mutants but other retinal neurons are present. Retinal cryosections from wild type (A, C, E, G) and pde6cw (B, D, F, H) adults (60 dpf) were immunolabeled with the following antibodies: 1D1 (A-B), which labels rhodopsin; Zpr-1 (C, D), which labels the double-cones; PKC-α (E, F) which labels bipolar cells; and Hu-C/D (G, H) which labels ganglion cells and amacrine cells. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Lack of reactive gliosis in XOPS-mCFP retinas. Retinal cryosections from 40 dpf wild type (A) and XOPS-mCFP (B) animals immunolabled for PCNA (red) and the Müller cell marker Zrf-1. The Müller glia from XOPS-mCFP retinas do not colocalize with PCNA immunoreactivity, nor is there a change in morphology compared to wild type. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Increase in rod photoreceptors in the lor mutant. Wild type (A) and lor mutants (B) were whole mount immunolabeled with the rod-specific 4C12 antibody at 5 dpf; dissected retinas were imaged by confocal microscopy. In the lor mutant rod photoreceptors are so crowded at the back of the retina that the only gap visible is at the location of optic nerve exit (small black hole).

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; contract grant numbers: R01 EY017753, EY015165.

Contract grant sponsor: Women in Math, Science, and Engineering program at Florida State University.

The authors thank Gina Rockholt for animal care, Charles Badland for assistance with the figures, and the staff of the Biological Science Imaging Resources Facility at Florida State University for assistance with confocal microscopy.

Footnotes

This article contains supplementary material available via the Internet at http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/suppmat/1932-8451/suppmat/

REFERENCES

- Akimoto M, Cheng H, Zhu D, Brzezinski JA, Khanna R, Filippova E, Oh EC, et al. Targeting of GFP to newborn rods by Nrl promoter and temporal expression profiling of flow-sorted photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3890–3895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508214103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Williams DS, Neitz J, Fariss RN, Fliesler SJ. Tunicamycin-induced degeneration in cone photoreceptors. Vis Neurosci. 1988;1:153–158. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardos RL, Barthel LK, Meyers JR, Raymond PA. Late-stage neuronal progenitors in the retina are radial Muller glia that function as retinal stem cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7028–7040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1624-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braisted JE, Raymond PA. Regeneration of dopaminergic neurons in goldfish retina. Development. 1992;114:913–919. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.4.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braisted JE, Raymond PA. Continued search for the cellular signals that regulate regeneration of dopaminergic neurons in goldfish retina. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;76:221–232. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braisted JE, Essman TF, Raymond PA. Selective regeneration of photoreceptors in goldfish retina. Development. 1994;120:2409–2419. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumsted O’Brien KM, Cheng H, Jiang Y, Schulte D, Swaroop A, Hendrickson AE. Expression of photoreceptor-specific nuclear receptor NR2E3 in rod photoreceptors of fetal human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2807–2812. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DA. Cellular proliferation and neurogenesis in the injured retina of adult zebrafish. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17:789–797. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800175121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Rattner A, Nathans J. The rod photoreceptor-specific nuclear receptor Nr2e3 represses transcription of multiple cone-specific genes. J Neurosci. 2005;25:118–129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3571-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Aleman TS, Cideciyan AV, Khanna R, Jacobson SG, Swaroop A. In vivo function of the orphan nuclear receptor NR2E3 in establishing photoreceptor identity during mammalian retinal development. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2588–2602. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Khanna H, Oh EC, Hicks D, Mitton KP, Swaroop A. photoreceptor-specific nuclear receptor NR2E3 functions as a transcriptional activator in rod photoreceptors. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1563–1575. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadool JM. Development of a rod photoreceptor mosaic revealed in transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2003a;258:277–290. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadool JM. Rod genesis in the teleost retina as a model of neural stem cells. Exp Neurol. 2003b;184:14–19. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausett BV, Goldman D. A role for alpha1 tubulin-expressing Muller glia in regeneration of the injured zebrafish retina. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6303–6313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0332-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fimbel SM, Montgomery JE, Burket CT, Hyde DR. Regeneration of inner retinal neurons after intravitreal injection of ouabain in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1712–1724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5317-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ. Neural regeneration in the chick retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24:161–182. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliesler SJ, Rapp LM, Hollyfield JG. photoreceptor-specific degeneration caused by tunicamycin. Nature. 1984;311:575–577. doi: 10.1038/311575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock P, Kakuk-Atkins L. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor neuroD is expressed in the rod lineage of the teleost retina. J Comp Neurol. 2004;477:108–117. doi: 10.1002/cne.20244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt GA, Schmitt EA, Fadool JM, Dowling JE. Retinoic acid alters photoreceptor development in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13298–13303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns PR. Formation of photoreceptors in larval and adult goldfish. J Neurosci. 1982;2:178–198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-02-00178.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns PR, Easter SS., Jr. Growth of the adult goldfish eye. II. Increase in retinal cell number. J Comp Neurol. 1977;176:331–341. doi: 10.1002/cne.901760303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns PR, Fernald RD. Genesis of rods in teleost fish retina. Nature. 1981;293:141–142. doi: 10.1038/293141a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian D, Ennis K, Korenbrot JI. Birth and fate of proliferative cells in the inner nuclear layer of the mature fish retina. J Comp Neurol. 1998;394:271–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassen SC, Ramanan V, Montgomery JE, T Burket C, Liu CG, Vihtelic TS, Hyde DR. Time course analysis of gene expression during light-induced photoreceptor cell death and regeneration in albino zebrafish. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67:1009–1031. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kock JH. Neuronal addition and retinal expansion during growth of the crucian carp eye. J Comp Neurol. 1982;209:264–274. doi: 10.1002/cne.902090305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BA, Fadool JM, Malicki J, Dowling JE. The zebrafish young mutation acts non-cell-autonomously to uncouple differentiation from specification for all retinal cells. Development. 2000;127:2177–2188. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.10.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Shen Y, Rest JS, Raymond PA, Zack DJ. Isolation and characterization of a zebrafish homologue of the cone rod homeobox gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack AF, Fernald RD. Regulation of cell division and rod differentiation in the teleost retina. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;76:183–187. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90206-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren RE, Pearson RA, MacNeil A, Douglas RH, Salt TE, Akimoto M, Swaroop A, et al. Retinal repair by transplantation of photoreceptor precursors. Nature. 2006;444:203–207. doi: 10.1038/nature05161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata NL, Radu RA, Clemmons RC, Travis GH. Isomerization and oxidation of vitamin A in cone-dominant retinas: A novel pathway for visual-pigment regeneration in daylight. Neuron. 2002;36:69–80. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00912-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears AJ, Kondo M, Swain PK, Takada Y, Bush RA, Saunders TL, Sieving PA, et al. Nrl is required for rod photoreceptor development. Nat Genet. 2001;29:447–452. doi: 10.1038/ng774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AC, Schroeter EH, Bilotta J, Wong RO, Fadool JM. Cone survival despite rod degeneration in XOPS-mCFP transgenic zebrafish. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4762–4771. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi K, Sugawara K, Shinagawa S, Teranishi T, Kuo CH, Takasaki Y. Induction of immunoreactive proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in goldfish retina following intravitreal injection with tunicamycin. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;63:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90068-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochocinska MJ, Hitchcock PF. Dynamic expression of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor neuroD in the rod and cone photoreceptor lineages in the retina of the embryonic and larval zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:1–12. doi: 10.1002/cne.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otteson DC, Hitchcock PF. Stem cells in the teleost retina: Persistent neurogenesis and injury-induced regeneration. Vision Res. 2003;43:927–936. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00400-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otteson DC, D’Costa AR, Hitchcock PF. Putative stem cells and the lineage of rod photoreceptors in the mature retina of the goldfish. Dev Biol. 2001;232:62–76. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otteson DC, Cirenza PF, Hitchcock PF. Persistent neurogenesis in the teleost retina: Evidence for regulation by the growth-hormone/insulin-like growth factor-I axis. Mech Dev. 2002;117:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RE, Fadool JM, McClintock J, Linser PJ. Muller cell differentiation in the zebrafish neural retina: Evidence of distinct early and late stages in cell maturation. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429:530–540. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010122)429:4<530::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Rivlin PK. Germinal cells in the goldfish retina that produce rod photoreceptors. Dev Biol. 1987;122:120–138. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Barthel LK, Bernardos RL, Perkowski JJ. Molecular characterization of retinal stem cells and their niches in adult zebrafish. BMC Dev Biol. 2006;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Hitchcock P, Palopoli M. Neuronal cell proliferation and ocular enlargement in Black Moor goldfish. J Comp Neurol. 1988;276:231–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.902760207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonthaler H, Lampert J, Isken A, Rinner O, Mader A, Gesemann M, Oberhauser V, et al. Evidence for RPE65-independent vision in the cone-dominated zebrafish retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1940–1949. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns G, Evangelista M, Fadool JM, Brockerhoff SE. A mutation in the cone-specific pde6 gene causes rapid cone photoreceptor degeneration in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13866–13874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3136-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain PK, Hicks D, Mears AJ, Apel IJ, Smith JE, John SK, Hendrickson A, et al. Multiple phosphorylated isoforms of NRL are expressed in rod photoreceptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36824–36830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihtelic TS, Hyde DR. Light-induced rod and cone cell death and regeneration in the adult albino zebrafish (Danio rerio) retina. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:289–307. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(20000905)44:3<289::aid-neu1>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihtelic TS, Soverly JE, Kassen SC, Hyde DR. Retinal regional differences in photoreceptor cell death and regeneration in light-lesioned albino zebrafish. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:558–575. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book. University of Oregon Press; Eugene, OR: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wu DM, Schneiderman T, Burgett J, Gokhale P, Barthel L, Raymond PA. Cones regenerate from retinal stem cells sequestered in the inner nuclear layer of adult goldfish retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2115–2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurco P, Cameron DA. Responses of Muller glia to retinal injury in adult zebrafish. Vision Res. 2005;45:991–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygar CA, Colbert S, Yang D, Fernald RD. IGF-1 produced by cone photoreceptors regulates rod progenitor proliferation in the teleost retina. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;154:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Rods degenerate in XOPS-mCFP animals but other retinal cell types are unaffected. Retinal cryosections from wild type (A, C, E, G) and XOPS-mCFP (B, D, F, H) adults (6 months post fertilization) were immunolabeled with the following antibodies: 1D1 (A-B), which labels rhodopsin; Zpr-1 (C, D), which labels the double-cones; PKC-α (E, F) which labels bipolar cells; and Hu-C/D (G, H) which labels ganglion cells and amacrine cells. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Cones degenerate in pde6cw mutants but other retinal neurons are present. Retinal cryosections from wild type (A, C, E, G) and pde6cw (B, D, F, H) adults (60 dpf) were immunolabeled with the following antibodies: 1D1 (A-B), which labels rhodopsin; Zpr-1 (C, D), which labels the double-cones; PKC-α (E, F) which labels bipolar cells; and Hu-C/D (G, H) which labels ganglion cells and amacrine cells. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Lack of reactive gliosis in XOPS-mCFP retinas. Retinal cryosections from 40 dpf wild type (A) and XOPS-mCFP (B) animals immunolabled for PCNA (red) and the Müller cell marker Zrf-1. The Müller glia from XOPS-mCFP retinas do not colocalize with PCNA immunoreactivity, nor is there a change in morphology compared to wild type. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Increase in rod photoreceptors in the lor mutant. Wild type (A) and lor mutants (B) were whole mount immunolabeled with the rod-specific 4C12 antibody at 5 dpf; dissected retinas were imaged by confocal microscopy. In the lor mutant rod photoreceptors are so crowded at the back of the retina that the only gap visible is at the location of optic nerve exit (small black hole).