Abstract

Macrophages are an important source of inflammatory cytokines generated during the innate immune response, but in the microenvironment of certain tumors, macrophages promote tumor progression through their preferential secretion of cytokines that support tumor cell growth and suppress antitumoral immune responses. KSHV is the causative agent of KS and lymphomas preferentially arising in immunocompromised patients, and specific cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-10, have been implicated in KSHV-associated cancer pathogenesis. However, the contribution of KSHV-infected macrophages to the cytokine milieu within KSHV-related tumors is unclear. We found that individual KSHV-encoded miRNA induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion independently and additively by murine macrophages and human myelomonocytic cells. Bioinformatics analysis identified KSHV miRNA binding sites for miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7 within the 3′UTR of the basic region/leucine zipper motif transcription factor C/EBPβ, a known regulator of IL-6 and IL-10 transcriptional activation. Subsequent immunoblot analyses revealed that miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7 preferentially reduce expression of C/EBPβ p20 (LIP), an isoform of C/EBPβ known to function as a negative transcription regulator. In addition, RNA interference specifically targeting LIP induced basal secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 by macrophages. Taken together, these data support a role for KSHV miRNA in the programming of macrophage cytokine responses in favor of KSHV-related tumor progression.

Keywords: cytokines, virus, inflammation, cancer

Introduction

KSHV is the etiologic agent of PEL [1], MCD [2], and KS—the most common tumor associated with HIV infection and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in this population [3, 4]. Existing data suggest that cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-10, play an important role in cancer pathogenesis associated with KSHV, including the promotion of tumor cell growth and angiogenesis and the suppression of T cell activation [5,6,7,8]. Although KSHV-infected tumor cells are a primary source of these cytokines, other data suggest that KSHV-infected myeloid cells, including macrophages, may produce tumor-associated cytokines as well [9,10,11]. KSHV establishes infection within monocytes in the peripheral circulation [12] as well as monocytes and their mature macrophage counterparts in KSHV-associated tumors [13,14,15]. Additional studies have implicated specific KSHV-encoded genes, including the viral glycoprotein vOX2, in the regulation of IL-6 production by monocytes and macrophages [11]. However, the role of KSHV gene expression in the regulation of tumor-promoting cytokine production by myeloid cells requires further characterization.

Cellular miRNA have been implicated in the regulation of cytokine activation [16,17,18], and KSHV encodes 17 mature miRNA (KSHV miRNA) [19,20,21], but whether KSHV miRNA regulate cytokine expression is unknown. In this study, using complimentary murine and human cell culture systems, we found that KSHV infection and KSHV miRNA overexpression induce the preferential secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 by macrophages and myelomonocytic cells. Moreover, we found that this effect was mediated by two specific miRNA, miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7, in part through the down-regulation of LIP. These data offer important insights for the putative role of infected macrophages in KSHV-associated cancer pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

BCBL-1 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.05 mM β-ME, and 0.02% (wt/vol) sodium bicarbonate. Human myelomonocytic leukemia (MM6) cells (DSMZ, Germany) were cultured in RPMI-1640 media, supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.1 mM MEM nonessential amino acid solution (Gibco), and 0.01% OPI media supplement (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Murine macrophage (RAW cells) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and grown in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS. HeLa cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Flow cytometry

Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6, IL-10, MCP-1, IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-12p70, were quantified within culture supernatants using a commercially available cytokine bead array (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were analyzed using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur analytical flow cytometer and CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences).

ELISA

Quantification of IL-6 and IL-10 within supernatants from transfected RAW cell cultures was performed using quantikine mouse IL-6 or IL-10 immunoassay kits, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Quantification of IL-6 and IL-10 within supernatants from transfected MM6 cells was performed using human IL-6 or IL-10 ELISA kits, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA).

KSHV purification and infection

BCBL-1 cells were incubated with 0.6 mM valproic acid for 4–6 days, and KSHV was purified from the culture supernatants by ultracentrifugation at 20,000 g for 3 h, 4°C. The viral pellet was resuspended in 1/100 original vol in the appropriate culture media, and aliquots were frozen at –80°C. Target cells were incubated with concentrated virus in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at 37°C. Inactivated KSHV, used for negative controls, was prepared by incubating viral stocks with UV light for 10 min in CL-1000 UV cross-linker (UV peroxide). The concentration of infectious viral particles used in each experiment (MOI) was calculated as described previously [21, 22].

IFA

HeLa cells (1×104/eight-well chamber slide; Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) were incubated with serial dilutions of viral stocks in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at 37°C. Sixteen hours later, cells were fixed and permeabilized following incubation with 1:1 methanol:acetone for 10 min at –20°C. To reduce nonspecific staining, slides were incubated in blocking reagent (10% normal goat serum, 3% BSA, and 1% glycine) for 30 min. To identify expression of the KSHV-encoded LANA cells were incubated subsequently with 1:1000 dilution of an anti-LANA rat mAb (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA) for 1 h, followed by a goat anti-rat secondary antibody (1:100) conjugated to Texas Red (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at 25°C. Nuclei were counterstained subsequently with 0.5 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma-Aldrich) in 180 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Slides were examined at 60× magnification using a Nikon TE2000-E fluorescence microscope. LANA expression (LANA dots/cell) was determined following examination of cells from within five to six random fields in each experimental and control group.

Transfection assays

A 2.8-Kbp construct encoding 10 individual KSHV miRNA (pcDNA-miRNA) and luciferase reporter constructs encoding complimentary sequences for individual miRNA (pGL3-miRNA sensors) have been validated elsewhere for demonstrating expression of KSHV miRNA following transient transfection [23]. These constructs were kindly provided to our laboratory by Dr. Rolf Renne (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA) and used to transiently transfect RAW cells. For inhibition of mature miRNAs, 2′OMe RNA antagomirs, whose use for reducing KSHV miRNA expression is validated elsewhere [23], were designed and obtained from the manufacturer (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA). siRNAs targeting C/EBPβ and nontarget control siRNA were purchased from the manufacturer (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Cells were transfected with pcDNA-miRNA, pGL3-miRNA sensors, 2′OMe RNA antagomirs, siRNAs, empty pcDNA vectors for negative controls, or combinations of these in 12-well plates for 48 h using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For miRNA inhibitor assays, cells were transfected with a 2′OMe RNA antagomir targeting a KSHV miRNA, designated miR-K12-12, not encoded by the pcDNA-miRNA construct. For luciferase expression assays, cells were lysed with 100 μL lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and 20 μL aliquots from each lysate were analyzed for luciferase activity using a Berthold FB12 luminometer. Light units were normalized to total protein levels for each sample using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfection efficiency was determined further through cotransfection of a LacZ reporter construct, kindly provided by Dr. Yusuf Hannun (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA), and β-galactosidase activity was determined using a commercially available β-galactosidase enzyme assay system, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Two to three independent transfections were performed for each experiment, and all samples were analyzed in triplicate for each transfection.

TLR inhibition assays

RAW cells were transfected with 1 μg pcDNA-miRNA or pcDNA for negative controls, and 24 h following transfection, cells were treated for 3 h with 10 mM dsRNA-activated PKR inhibitor 2-AP (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) and incubated for an additional 24 h. In parallel experiments, transfected cells were incubated with 100 μM MyD88 inhibitory peptide or control peptide (Imgenex, San Diego, CA, USA) for 24 h, and then cytokine quantification was performed as above.

Immunoblots

Cells were lysed in buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF, and 5 mM Na3VO4. Total cell lysates (30 μg) were resolved by SDS–10% PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with rabbit antibodies specific for C/EBPβ (C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) for loading controls. Immunoreactive bands were developed by an ECL reaction, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA), visualized by autoradiography, and quantitated using Image-J software.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using the RNeasy Mini kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized from equal total RNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Coding sequences for genes of interest and β-actin (loading control) were amplified from 200 ng input cDNA and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Custom primer sequences used for amplification experiments (Eurofins MWG Operon, Huntsville, AL, USA) were as follows: IL-6 sense 5′ TGTGCAATGGCAATTCTGAT 3′; IL-6 antisense 5′ GGAAATTGGGGTAGGAAGGA 3′; IL-6Rα sense 5′ AGTTCCAGCTTCGATACCGAC 3′; IL-6Rα antisense 5′ GTATTGTCAGACCCAGAGCTG 3′; IL-10 sense 5′ AACATACTGCTAACCGACTC 3′; IL-10 antisense 5′ TGGCCTTGTAGACACCTT 3′; IL-10R1 sense 5′ GTTTGCTCCCATTCCTCG 3′; IL-10R1 antisense 5′ ATGCCGTCCATTGCTTTC 3′; IL-10R2 sense 5′ TTCAAGGGTTTCTTCTCG 3′; IL-10R2 antisense 5′ TTCGCTGATGATGCTTAGTT 3′; β-actin sense 5′ GGGAATGGGTCAGAAGGACT 3′; β-actin antisense 5′ TTTGATGTCACGCACGATTT 3′; KSHV ORF73 (LANA) sense 5′ TCCCTCTACACTAAACCCAATA 3′; KSHV ORF73 antisense 5′ TTGCTAATCTCGTTGTCCC 3′; KSHV ORF71 (vFLIP) sense 5′ GGGCACGGATGACAGGGAA 3′; KSHV ORF71 antisense 5′ TGTGATGGGCCGGAAAGG 3′. Amplification was performed in an iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) under conditions of 94°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. For real-time RT-PCR assays, fold change was determined through automated analyses using Bio-Rad iQ5 v2.0 software. Samples amplified in the absence of RT (“no-RT” samples) were used as controls for RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR, and these samples revealed no amplification of cellular or viral genes (data not shown).

KSHV miRNA target identification

3′UTR sequences of IL-6- and IL-10-associated genes were obtained from Ensemble (http://www.ensembl.org). 3′UTRs were analyzed to extract all potential KSHV miRNA binding sites using an ad hoc scanning program specifically developed to assess 3′UTR KSHV miRNA seed sequence matching, as validated in a previous study [24].

Statistical analysis

Significance for differences between experimental and control groups was determined using the two-tailed Student’s t-test (Excel 8.0), and P values <0.05 or <0.01 were considered significant or highly significant.

RESULTS

KSHV miRNA induce secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 by macrophages

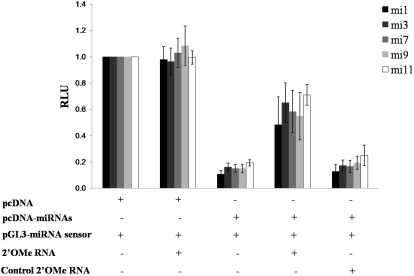

We used a BALB/c-derived murine macrophage cell line, RAW cells, as our host cell line for initial miRNA transfection assays. We chose these cells given the recent demonstration of KSHV infection of murine macrophages in vivo [25] and their amenability for gene transfer studies. For transfection experiments, we used a recently characterized construct (pcDNA-miRNA) [23] encoding 10 of the 17 known mature KSHV miRNA and validated the expression of individual miRNA in RAW cells through cotransfection of luciferase sensor vectors encoding complimentary sequences for mature miRNA (Fig. 1) as characterized elsewhere [23]. We also validated the ability of sequence-specific miRNA antagomirs (inhibitors) for reducing the expression of individual mature miRNA, as demonstrated previously [23] (Fig. 1). We observed a 50–60% reduction in the expression of each of five different miRNA in the presence of their respective antagomirs as compared with a control antagomir that had no effect on the expression of miRNA in these assays (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Murine macrophages express KSHV miRNA following transient transfection. RAW cells were transiently cotransfected with combinations of 1 μg empty control vector (pcDNA), 1 μg of a construct encoding 10 individual KSHV miRNA (pcDNA-miRNAs), 0.5 μg respective miRNA luciferase reporter constructs (pGL3-miRNA sensor), and 300 pmol 2′OMe RNA antagomirs targeting miR-K12-1 (mi1), miR-K12-3, miR-K12-7, miR-K12-9, miR-K12-11, or miR-K12-12 (the latter as a negative control, as miR-K12-12 is not expressed in the pcDNA-miRNA construct). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed for quantitation of luciferase expression normalized to total protein content (RLU). A reduction in luciferase expression denotes expression of mature miRNA. Error bars represent the sem for two independent experiments.

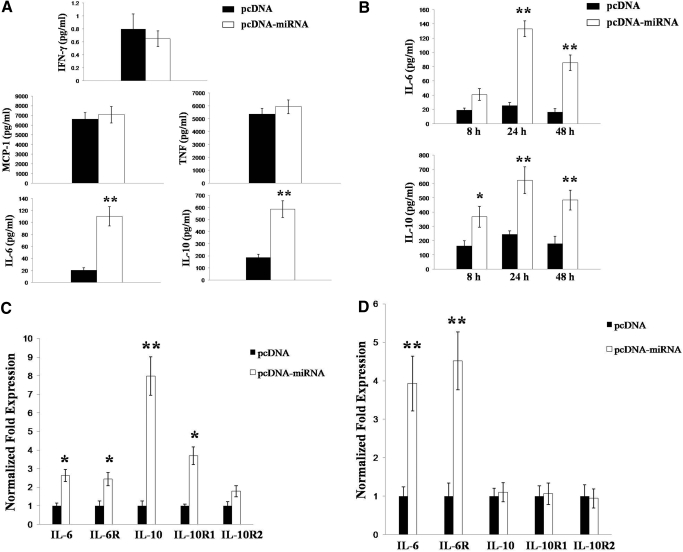

Next, we used a flow cytometry-based bead array to quantify release of multiple inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by miRNA-transfected macrophages. Compared with control transfectants, miRNA expression increased macrophage secretion of IL-6 (∼5.5-fold) and IL-10 (3-fold; Fig. 2A, P<0.01) significantly. Subsequent ELISA experiments confirmed that the increased secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 was maintained for 48 h after transfection (Fig. 2B, P<0.01). Furthermore, real-time RT-PCR analyses revealed that KSHV miRNA significantly induce macrophage expression of transcripts for IL-6, IL-10, and their respective receptor subunits (IL-6R and IL-10R1, Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

KSHV miRNA induce secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 by macrophages. RAW cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA or pcDNA-miRNA as above. (A) Twenty-four hours later, cytokines were quantified in culture supernatants using a flow cytometry-based bead array, per the manufacturer’s instructions. (B) In subsequent experiments, IL-6 and IL-10 secretion was quantified in culture supernatants by ELISA at different time-points following transfection. (C and D) Transcripts for IL-6, IL-10, and their respective receptor components were amplified by real-time RT-PCR 8 h (C) or 24 h (D) after transfection of RAW cells with pcDNA or pcDNA-miRNA. Normalized fold change, using no-RT samples and β-actin amplification for loading controls, was calculated using automated Bio-Rad iQ5 v2.0 software. Error bars represent the sem for two (A and B) or three (C and D) independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

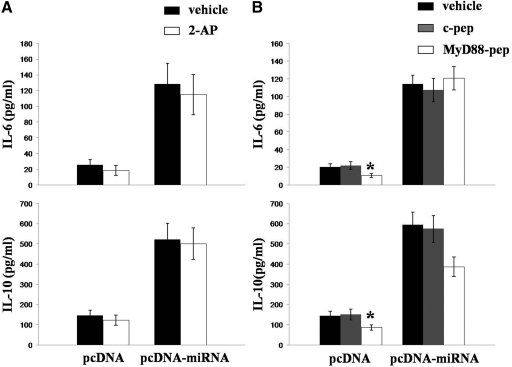

Induction of IL-6 and IL-10 by KSHV miRNA is independent of TLR pathways

Previous studies have indicated that IL-6 and IL-10 can be induced via stimulation of TLR pathways [26], and TLRs are activated by nucleic acids as part of the nonspecific innate immune response [27]. Therefore, it is conceivable that KSHV miRNA up-regulate IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages through nonspecific interactions between TLR and intermediates formed either during miRNA processing or miRNA targeting and repression of genes involved in TLR-initiated signaling. In fact, a recent study showed that IL-6 expression is up-regulated following KSHV activation of TLR3 [28]. To determine whether macrophage production of IL-6 and IL-10 induced by KSHV miRNA is mediated through TLR pathways, RAW cells were incubated with inhibitors of TLR pathways prior to transfection (Fig. 3). For these experiments, we used 2-AP, an inhibitor of the dsRNA-dependent PKR, whose activity is critical for TLR3 and TLR2/4 pathway activation [29, 30]. We also used a specific inhibitor of the adaptor protein MyD88, whose activity is critical for signal transduction following activation of a number of different TLRs, including the ssRNA-responsive TLR7/8 and TLR4 pathways [31,32,33]. Cells transfected with KSHV miRNA exhibited no significant reduction in their secretion of IL-6 or IL-10 following 2-AP (Fig. 3A) or MyD88 inhibitor (Fig. 3B) treatment. MyD88 inhibition reduced IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by control transfectants, presumably through a reduction in nonspecific TLR activation during transfection (Fig. 3B). Together, these data suggest that KSHV miRNA induction of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages is the result of cellular mRNA targeting by individual miRNA, individually or in combination.

Figure 3.

KSHV miRNA induction of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages is independent of TLR pathways. (A) RAW cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA or pcDNA-miRNA for 24 h, then incubated with 10 mM 2-AP or vehicle control for 3 h, and incubated for an additional 24 h. (B) In parallel, RAW cells were transfected as in A and then incubated with 100 μM of a control peptide or MyD88 inhibitor peptide for 24 h. Cytokines were quantified within culture supernatants by ELISA. Error bars represent the sem for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05.

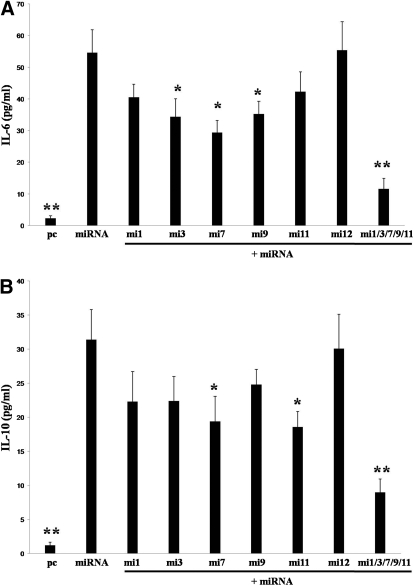

Specific KSHV miRNA induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by monocytes and macrophages

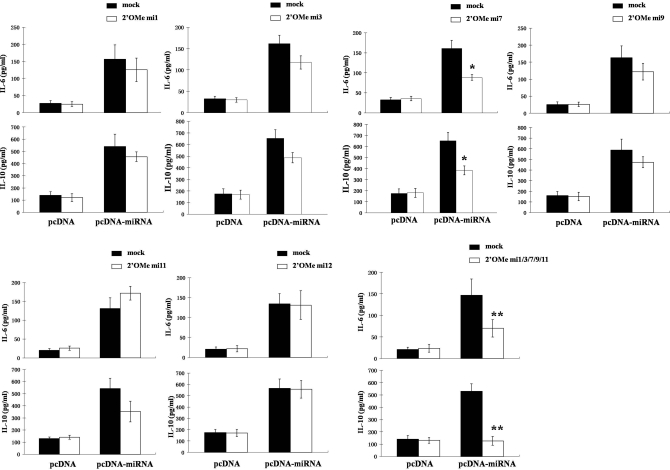

To explore further which KSHV miRNA may be involved in the regulation of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages, we cotransfected these cells with the pcDNA-miRNA construct and RNA antagomirs. A bioinformatics approach validated elsewhere [24] was used first to determine whether specific murine genes associated with IL-6 and IL-10 regulation contained 3′UTR binding sites for KSHV miRNA. As anticipated, multiple genes contained KSHV miRNA binding sites for which functional repression of these genes was predicted based on this analysis (data not shown). More specifically, this analysis predicted binding and functional repression of multiple genes by KSHV miR-K12-1, -3, -7, -9, and -11. Therefore, we designed RNA antagomirs for these five miRNAs to elucidate their individual and collective roles in KSHV miRNA induction of IL-6 and IL-10. For controls, we cotransfected cells with an RNA antagomir targeting KSHV miR-K12-12, one of the KSHV miRNA not encoded by the construct. Relative to control cells transfected with the miR-K12-12-specific antagomir for which there was no discernable change in IL-6 and IL-10 secretion, inhibition of miR-K12-1, -3, and -9 tended to repress IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by KSHV miRNA transfectants, although these differences were not significant (Fig. 4). Inhibition of miR-K12-11 resulted in augmentation of IL-6 secretion and repression of IL-10, although these changes were also not significant. However, inhibition of miR-K12-7 resulted in significant repression of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by KSHV miRNA transfectants (Fig. 4, P<0.05). Moreover, cotransfection of multiple miRNA antagomirs demonstrated additive and highly significant repression of IL-6 and IL-10 (Fig. 4, P<0.01). This suggests that multiple KSHV miRNA, through their targeting of different cytokine regulatory genes or redundant targeting of genes, induces secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 by macrophages.

Figure 4.

Individual KSHV miRNA differentially regulate IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages. RAW cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA or pcDNA-miRNA with additional transfection media (solid bars, “mock”) or inhibitors of individual KSHV miRNA (open bars; 2′OMe miX, where X=numeric designation of KSHV miRNA). Of note, the 2′OMe RNA antagomir targeting KSHV miR-K12-12, a miRNA not encoded by the pcDNA-miRNA construct, was used as a negative control. Forty-eight hours following transfection, cytokines were quantified in supernatants by ELISA. Error bars represent the sem for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To validate these findings, we incubated macrophages with purified KSHV virions to determine whether KSHV miRNA were expressed following infection of macrophages and whether viral miRNA induced cytokine secretion in this setting. By IFA, we observed expression of LANA within 8–15% of targeted RAW cells with a MOI of ∼10 (Fig. 5A), as well as expression of representative latent KSHV transcripts for LANA and vFLIP by RT-PCR (Fig. 5B). Despite the relatively low level of infection in these cells, we were able to discern variable expression of KSHV miRNA over time (Fig. 5C). In addition, KSHV induced secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 relative to cells incubated with UV-KSHV (Fig. 5D and 5E), further supporting the infection-dependent nature of IL-6 and IL-10 induction by KSHV for these cells. Moreover, transfection of KSHV-infected cells with specific RNA antagomirs repressed IL-6 (Fig. 5D) and IL-10 (Fig. 5E) secretion. Once again, miR-K12-7 inhibition or concurrent inhibition of multiple miRNA exhibited the greatest repression of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion in these assays.

Figure 5.

KSHV miRNA induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion following de novo infection of macrophages by KSHV. (A) For IFA, RAW cells were incubated with purified KSHV (K+) or UV-inactivated KSHV (K–) for 2 h (MOI ∼10), and then cells were fixed 16 h later, prior to their incubation with an anti-LANA mAb and a secondary antibody conjugated to Texas Red to identify the typical punctate intranuclear expression of KSHV LANA (red dots). (B) Sixteen hours after viral incubation, transcripts for LANA and vFLIP were amplified by RT-PCR, and β-actin was amplified as an internal control. (C) In parallel experiments, RAW cells were transfected with 0.5 μg pGL-miRNA sensors (mi-X=pGL sensor plasmid encoding compliment for miR-K12-X) overnight and then incubated with purified KSHV or UV-KSHV as above. Luciferase expression was quantified subsequently for cells collected 2 h or 24 h following viral incubation (p.i.), as outlined in Materials and Methods. (D and E) RAW cells were transfected with 300 pmol 2′OMe RNA targeting miRNA (miX=antagomir for miR-K12-X) for 48 h and then infected with purified KSHV. IL-6 (D) and IL-10 (E) were quantified within culture supernatants 24 h after viral incubation by ELISA. Error bars represent the sem for three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Next, we quantified IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by human cells following their transfection with KSHV miRNA. For these studies, we chose MM6 cells, a human myelomonocytic leukemia cell line amenable to gene transfer studies and shown previously to produce inflammatory cytokines [34, 35]. We found that expression of KSHV miRNA in these cells increased their secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 significantly (Fig. 6; P<0.01). Moreover, as in our prior studies, we found that inhibition of individual KSHV miRNA repressed IL-6 and IL-10 secretion. Concurrent inhibition of multiple miRNA suppressed IL-6 and IL-10 secretion significantly (Fig. 6; P<0.01).

Figure 6.

KSHV miRNA induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by human monocytes. MM6 cells were transiently cotransfected with 1 μg pcDNA or pcDNA-miRNA and 300 pmol 2′OMe miX, and the 2′OMe mi12 was used as a negative control as above. Supernatants were collected 48 h later and IL-6 (A) and IL-10 (B) quantified by ELISA. Error bars represent the sem for two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 relative to pcDNA miRNA transfectants.

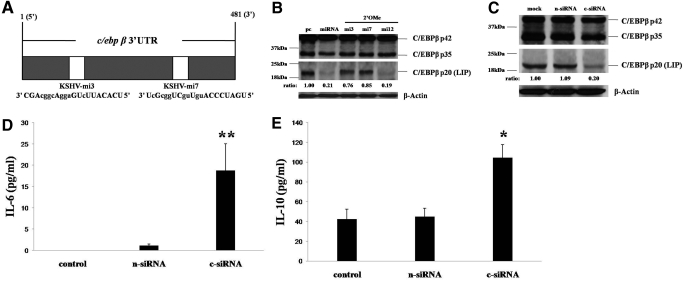

KSHV miRNA induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion through the targeting of the C/EBPβ LIP isoform

Our bioinformatics analysis identified KSHV miRNA binding sites for miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7 in the 3′UTR of the murine C/EBPβ gene (Fig. 7A), suggesting the possibility of functional repression of this gene by these two miRNAs. Subsequent analyses revealed that miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7 specifically suppress expression of LIP and only slightly affect expression of the other two C/EBPβ isoforms (p42 and p35) and that antagomirs targeting miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7 restored expression of LIP (Fig. 7B). To determine whether LIP regulates basal expression of IL-6 and IL-10 by macrophages, we transfected RAW cells with specific siRNA preferentially targeting LIP and found that this reduced LIP expression by 70–80% (Fig. 7C). We subsequently found that siRNA targeting of LIP significantly increased basal secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 by macrophages (Fig. 7, D and E).

Figure 7.

KSHV miRNA induce macrophage secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 through the down-regulation of C/EBPβ. (A) KSHV miRNA binding sites in the 3′UTR region of C/EBPβ. KSHV miRNA nucleotides with matching base pairs within the C/EBPβ 3′UTR (1–481 bp) are depicted in capital letters. (B) RAW cells were transfected with pcDNA (pc) or pcDNA-miRNA (miRNA) or cotransfected with pcDNA-miRNA and 2′OMe antagomirs (miX; X=miR-K12-X targeted by the antagomir). For Western blot analyses 24 h later, cell lysates were incubated with a C/EBPβ-specific antibody recognizing three independent isoforms of this protein (p42, p35, and LIP), and the intensity of immunoreactive bands for LIP was quantified relative to pcDNA control transfectants using Image-J software. (C) RAW cells were incubated with transfection reagent alone (mock) or control, nontarget siRNA (n-siRNA) or C/EBPβ-specific siRNA (c-siRNA). Twenty-four hours later, Western blot quantified C/EBPβ isoform expression as in B. β-Actin was quantified for loading controls for all Western blots. (D and E) IL-6 and IL-10 were quantified within supernatants from cultures in C by ELISA. Error bars represent the sem for two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Monocytes and macrophages are infected by KSHV within MCD and KS lesions [13,14,15, 36], and data support a potential role for KSHV-encoded mechanisms in the regulation of cytokine production by these cells [9,10,11, 28]. One study suggested that KSHV up-regulates expression of TLR3 and IL-6 activation by THP-1 myelomonocytic cells [28], although another study indicated that KSHV-encoded mechanisms actually down-regulate TLR4-mediated signal transduction [31]. Other studies support a role for the KSHV-encoded early lytic glycoprotein vOX2 in the regulation of cytokine responses by macrophages [9,10,11]. miRNAs are small (19–23 nucleotides in length), noncoding RNAs that bind target mRNA, marking them for degradation or post-transcriptional modification [37], and KSHV encodes 17 mature miRNAs, which are expressed within KSHV-infected cells and KS lesions [19,20,21, 38]. As cellular miRNAs have been implicated in the induction of cytokine activation [16,17,18], we sought to determine whether KSHV miRNAs induce the production of KSHV tumor-associated inflammatory cytokines by macrophages.

We found that KSHV miRNAs activate transcription and secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 by macrophages (Fig. 2) and myelomonocytic cells (Fig. 6). The relevance of these data was supported further by the observations that KSHV-miRNA are expressed following de novo infection of macrophages and that KSHV miRNA increase IL-6 and IL-10 secretion individually and collectively in this setting (Fig. 5). These observations were discernable despite a relatively low level of infection (10–15% infection efficiency) achieved within RAW cells, even using a relatively high MOI, as well as variable, time-dependent expression of KSHV-miRNA following infection of these cells (Fig. 5). Furthermore, UV-KSHV did not induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion (Fig. 5), and KSHV miRNA-specific antagomirs repressed IL-6 and IL-10 secretion (Fig. 4). These latter results concur with the lack of suppression of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion induced by miRNA transfection during their treatment with inhibitors of TLR pathways (Fig. 3) and suggest that the induction of IL-6 and IL-10 in these experiments was a result of miRNA targeting of cellular genes rather than nonspecific activation of TLR or other pathways by viral structural proteins or nucleic acids. We cannot exclude the possibility that KSHV-encoded homologous cellular IL-6, viral IL-6, also induced IL-6 secretion by macrophages infected by KSHV, as reported previously for other cell types [39, 40]. The human myelomonocytic cell line THP-1 also supports latent KSHV infection [28], but neither THP-1 cells nor MM6 cells were suitable for our studies to determine the role of KSHV miRNAs in cytokine secretion during de novo infection, as these cells secreted only minimal amounts of IL-6 and IL-10 following infection (not shown). Future studies using human monocytes or macrophages from different sources, as well as other KSHV-infected cell types relevant to KSHV cancer pathogenesis, may help shed light on the relative roles of KSHV-infected cells and KSHV miRNAs in the secretion of tumor-promoting cytokines within the microenvironment.

We transfected cells with miRNA antagomirs to determine the role of individual miRNA in the induction of IL-6 and IL-10. Inhibition of miR-K12-7 repressed secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 consistently and significantly within miRNA-transfected (Figs. 4 and 6) and KSHV-infected cells (Fig. 5). Inhibition of other miRNA also tended to repress IL-6 and IL-10 secretion in these assays, although to a lesser extent. These differences may have been a result of relative differences in the repression of IL-6 and IL-10 for different miRNA or to differences in the level of expression for miRNA in these cells. However, the general pattern of repression of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion for the five different miRNA antagomirs selected for these studies was similar for two miRNA-transfected cell lines and KSHV-infected macrophages. As each individual KSHV miRNA likely targets hundreds of genes [23, 24] and as we focused only on the role of miRNAs identified by our bioinformatics analysis that putatively target one or more preselected genes associated with cytokine regulation, additional studies are needed to characterize further the role of individual KSHV miRNA in regulating cytokine responses in macrophages and other myeloid cells. Not surprisingly, our data indicate that multiple KSHV miRNAs act cooperatively to induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages.

C/EBP transcription factor family members bind to the same CCAAT palindromic DNA sequence through homo- or heterodimerization with other family members [41]. Existing data suggest that C/EBPβ transactivates KSHV gene expression [42,43,44], but to our knowledge, a relationship between C/EBPβ and KSHV induction of cytokines has not been identified. C/EBPβ acts as a transcription regulator of a number of inflammatory intermediates secreted by macrophages and other myeloid cells, including IL-6 and IL-10, through its binding to specific promoter regions [45,46,47,48]. Interestingly, three C/EBPβ isoforms are translated from a single mRNA through the alternative use of three translation initiation codons within the same open reading frame [49]. One of these isoforms, C/EBPβ p20 or LIP, lacks a transactivation domain and is believed to function as a dominant-negative transcriptional repressor of activation by the other isoforms [49]. Our bioinformatics analyses revealed binding sites for two individual KSHV-encoded miRNA, miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7, within the 3′UTR of C/EBPβ (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, miR-K12-3 and miR-K12-7 selectively repressed basal expression of LIP within macrophages (Fig. 7B). The relevance of these findings was supported by the induction of macrophage secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 with suppression of LIP using C/EBPβ-specific siRNA (Fig. 7, C–E). Our present studies do not rule out the possibility that KSHV miRNA, rather than targeting C/EBPβ directly, target some other gene(s) whose downstream effect is a reduction in C/EBPβ expression. Alternatively, direct targeting of C/EBPβ may induce IL-6 and IL-10 expression through some mechanism other than a reduction in C/EBPβ interaction with cytokine promoter regions. For example, the exchange protein activated by the cAMP-C/EBPβ pathway inhibits IL-6 production via induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling-3, a negative regulator of IL-6R signaling [50]. Studies using site-directed mutagenesis would confirm whether KSHV miRNA target C/EBPβ directly and whether direct binding of C/EBPβ to cytokine promoter regions mediates the induction of IL-6 and IL-10 by KSHV miRNA. In addition, the role of KSHV miRNA in regulating LIP or other C/EBPβ isoforms and cytokine production during KSHV infection of a broader variety of cell types relevant to KSHV-related cancer pathogenesis requires further investigation.

To our knowledge, these are the first data implicating KSHV miRNA and virus-encoded miRNA more generally in the activation of IL-6 and IL-10 production by myeloid cells, which has important implications for KSHV pathogenesis. IL-6 and IL-10 are found in the tumor microenvironment and peripheral circulation of patients with KS, PEL, and MCD [5,6,7, 51] and inhibit differentiation of immature DC [8, 52, 53]. Moreover, IL-10 reduces T cell activation as part of the normal compensatory machinery for preventing excessive proinflammatory responses [52, 53]. In fact, IL-6 and IL-10 inhibit DC maturation to help PEL cells escape from host immune recognition [8] and simultaneously act as independent growth factors for these cells [5, 51]. IL-10 also inhibits cytokine production by activated Th1 cells, NK cells, and macrophages and represses macrophage cytotoxic activity [54, 55]. Furthermore, IL-6 enhances angiogenesis through the induction of vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor synthesis [56,57,58]. Additional studies are under way to determine whether KSHV-infected macrophage secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 influences T cell activation, including autologous or antigen-specific T cell responses, as well as other aspects of KSHV cancer pathogenesis.

In summary, our studies represent the first report detailing the selective induction of cytokine production by virus-encoded miRNA, specifically, the induction of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages. Moreover, we have identified one putative mechanism for this effect: KSHV miRNA suppression of LIP. This work has implications for how KSHV regulates macrophage function in the tumor microenvironment to promote KSHV-related cancer pathogenesis. Additional work may uncover new approaches for the restoration of immune responses or suppression of other cancer-promoting pathways induced by KSHV through the inhibition of these KSHV-macrophage interactions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K08-1CA103858 to C. H. P.), the South Carolina COBRE for Oral Health (P20-RR-017696 to C. H. P.), and the MUSC Hollings Cancer Center (Core Grant P30-CA-138313 to the Hollings Cancer Center). We thank Dr. Rolf Renne at the University of Florida and Dr. Yussuf Hannun at the Medical University of South Carolina for providing the pcDNA-miRNA and LacZ constructs, respectively.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 2-AP=2-aminopurine, 2′OMe=2′O-methyl, 3′UTR=3′ untranslated region, BCBL-1=body cavity-based lymphoma, DC=dendritic cell, IFA=immunofluorescence assay(s), KS=Kaposi’s sarcoma, KSHV=Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, LANA=latency-associated nuclear antigen, LIP=liver inhibitory protein, MCD=multicentric Castleman’s disease, miR-K12-(#)=KSHV-encoded microRNAs, miRNA=microRNA, MM6=Mono-Mac-6, MOI=multiplicity of infection, PEL=primary effusion lymphoma, PKR=protein kinase, RAW cell=RAW 264.7 cell, RLU=relative luciferase expression, siRNA=small interfering RNA, vFLIP=viral Fas-associated death domain-like IL-1β-converting enzyme inhibitory protein

References

- Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore P S, Said J W, Knowles D M. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals-Hatem D, Babinet P, d'Agay M F, Clauvel J P, Raphael M, Degos L. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1995;86:1276–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels E A, Biggar R J, Hall H I, Cross H, Crutchfield A, Finch J L, Grigg R, Hylton T, Pawlish K S, McNeel T S, Goedert J J. Cancer risk in people infected with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:187–194. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet F, Lewden C, May T, Heripret L, Jougla E, Bevilacqua S, Costagliola D, Salmon D, Chene G, Morlat P. Malignancy-related causes of death in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer. 2004;101:317–324. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K D, Aoki Y, Chang Y, Moore P S, Yarchoan R, Tosato G. Involvement of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and viral IL-6 in the spontaneous growth of Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus-associated infected primary effusion lymphoma cells. Blood. 1999;94:2871–2879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki Y, Yarchoan R, Braun J, Iwamoto A, Tosato G. Viral and cellular cytokines in AIDS-related malignant lymphomatous effusions. Blood. 2000;96:1599–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksenhendler E, Carcelain G, Aoki Y, Boulanger E, Maillard A, Clauvel J P, Agbalika F. High levels of human herpesvirus 8 viral load, human interleukin-6, interleukin-10, and C reactive protein correlate with exacerbation of multicentric Castleman disease in HIV-infected patients. Blood. 2000;96:2069–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirone M, Lucania G, Aleandri S, Borgia G, Trivedi P, Cuomo L, Frati L, Faggioni A. Suppression of dendritic cell differentiation through cytokines released by primary effusion lymphoma cells. Immunol Lett. 2008;120:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salata C, Curtarello M, Calistri A, Sartori E, Sette P, de Bernard M, Parolin C, Palu G. vOX2 glycoprotein of human herpesvirus 8 modulates human primary macrophages activity. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:698–706. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaee S A, Gracie J A, McInnes I B, Blackbourn D J. Inhibition of neutrophil function by the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus vOX2 protein. AIDS. 2005;19:1907–1910. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000189849.75699.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y H, Means R E, Choi J K, Lee B S, Jung J U. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus OX2 glycoprotein activates myeloid-lineage cells to induce inflammatory cytokine production. J Virol. 2002;76:4688–4698. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4688-4698.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirianni M C, Vincenzi L, Fiorelli V, Topino S, Scala E, Uccini S, Angeloni A, Faggioni A, Cerimele D, Cottoni F, Aiuti F, Ensoli B. γ-Interferon production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes from Kaposi’s sarcoma patients: correlation with the presence of human herpesvirus-8 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and lesional macrophages. Blood. 1998;91:968–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupin N, Fisher C, Kellam P, Ariad S, Tulliez M, Franck N, van Marck E, Salmon D, Gorin I, Escande J P, Weiss R A, Alitalo K, Boshoff C. Distribution of human herpesvirus-8 latently infected cells in Kaposi’s sarcoma, multicentric Castleman’s disease, and primary effusion lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4546–4551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valmary S, Richard P, Brousset P. Frequent detection of Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus in germinal centre macrophages from AIDS-related multicentric Castleman’s disease. AIDS. 2005;19:1229–1231. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000176225.56108.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasig C, Zietz C, Haar B, Neipel F, Esser S, Brockmeyer N H, Tschachler E, Colombini S, Ensoli B, Sturzl M. Monocytes in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions are productively infected by human herpesvirus 8. J Virol. 1997;71:7963–7968. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7963-7968.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M M, Moschos S A, Williams A E, Shepherd N J, Larner-Svensson H M, Lindsay M A. Rapid changes in microRNA-146a expression negatively regulate the IL-1β-induced inflammatory response in human lung alveolar epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:5689–5698. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrocca F, Visone R, Onelli M R, Shah M H, Nicoloso M S, de Martino I, Iliopoulos D, Pilozzi E, Liu C G, Negrini M, Cavazzini L, Volinia S, Alder H, Ruco L P, Baldassarre G, Croce C M, Vecchione A. E2F1-regulated microRNAs impair TGFβ-dependent cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:272–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen I, David M. MicroRNAs in the immune response. Cytokine. 2008;43:391–394. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S, Sewer A, Lagos-Quintana M, Sheridan R, Sander C, Grasser F A, van Dyk L F, Ho C K, Shuman S, Chien M, Russo J J, Ju J, Randall G, Lindenbach B D, Rice C M, Simon V, Ho D D, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nat Methods. 2005;2:269–276. doi: 10.1038/nmeth746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Lu S, Zhang Z, Gonzalez C M, Damania B, Cullen B R. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus expresses an array of viral microRNAs in latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5570–5575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408192102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samols M A, Hu J, Skalsky R L, Renne R. Cloning and identification of a microRNA cluster within the latency-associated region of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol. 2005;79:9301–9305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9301-9305.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adang L A, Tomescu C, Law W K, Kedes D H. Intracellular Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus load determines early loss of immune synapse components. J Virol. 2007;81:5079–5090. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02738-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samols M A, Skalsky R L, Maldonado A M, Riva A, Lopez M C, Baker H V, Renne R. Identification of cellular genes targeted by KSHV-encoded microRNAs. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e65. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalsky R L, Samols M A, Plaisance K B, Boss I W, Riva A, Lopez M C, Baker H V, Renne R. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. J Virol. 2007;81:12836–12845. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01804-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons C H, Adang L A, Overdevest J, O'Connor C M, Taylor J R, Jr, Camerini D, Kedes D H. KSHV targets multiple leukocyte lineages during long-term productive infection in NOD/SCID mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1963–1973. doi: 10.1172/JCI27249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. Antiviral signaling through pattern recognition receptors. J Biochem. 2007;141:137–145. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:131–137. doi: 10.1038/ni1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J, Damania B. Upregulation of the TLR3 pathway by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus during primary infection. J Virol. 2008;82:5440–5449. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02590-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardenberg G, Planelles L, Schwarte C M, van Bostelen L, Le Huong T, Hahne M, Medema J P. Specific TLR ligands regulate APRIL secretion by dendritic cells in a PKR-dependent manner. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2900–2911. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet M C, Daurat C, Ottone C, Meurs E F. The N-terminus of PKR is responsible for the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway by interacting with the IKK complex. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1865–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos D, Vart R J, Gratrix F, Westrop S J, Emuss V, Wong P P, Robey R, Imami N, Bower M, Gotch F, Boshoff C. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates innate immunity to Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:470–483. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assier E, Marin-Esteban V, Haziot A, Maggi E, Charron D, Mooney N. TLR7/8 agonists impair monocyte-derived dendritic cell differentiation and maturation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:221–228. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0705385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Gerondakis S. Coordinating TLR-activated signaling pathways in cells of the immune system. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:420–424. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen L N, Nilsen A M, Lovik M. The mycotoxins citrinin and gliotoxin differentially affect production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6, and the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:782–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonks A J, Cooper R A, Jones K P, Blair S, Parton J, Tonks A. Honey stimulates inflammatory cytokine production from monocytes. Cytokine. 2003;21:242–247. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli V, Sirianni M C, Mezzaroma I, Mastroianni C M, Vullo V, Andreoni M, Narciso P, Scalzo C C, Nardi F, Pistilli A, Lo Coco F. Human herpesvirus-8 in lymphomatous and nonlymphomatous body cavity effusions developing in Kaposi’s sarcoma and multicentric Castleman’s disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1999;3:357–363. doi: 10.1016/s1092-9134(99)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan C S, Ganem D. MicroRNAs and viral infection. Mol Cell. 2005;20:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall V, Parks T, Bagni R, Wang C D, Samols M A, Hu J, Wyvil K M, Aleman K, Little R F, Yarchoan R, Renne R, Whitby D. Conservation of virally encoded microRNAs in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in primary effusion lymphoma cell lines and in patients with Kaposi sarcoma or multicentric Castleman disease. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:645–659. doi: 10.1086/511434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Nicholas J. Signal transduction by human herpesvirus 8 viral interleukin-6 (vIL-6) is modulated by the nonsignaling gp80 subunit of the IL-6 receptor complex and is distinct from signaling induced by human IL-6. J Virol. 2006;80:10874–10878. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00767-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Osborne J, Bestetti G, Chang Y, Moore P S. Viral IL-6-induced cell proliferation and immune evasion of interferon activity. Science. 2002;298:1432–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.1074883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson C R, Sigler P B, McKnight S L. Scissors-grip model for DNA recognition by a family of leucine zipper proteins. Science. 1989;246:911–916. doi: 10.1126/science.2683088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F Y, Tang Q Q, Chen H, ApRhys C, Farrell C, Chen J, Fujimuro M, Lane M D, Hayward G S. Lytic replication-associated protein (RAP) encoded by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus causes p21CIP-1-mediated G1 cell cycle arrest through CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10683–10688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162352299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F Y, Wang S E, Tang Q Q, Fujimuro M, Chiou C J, Zheng Q, Chen H, Hayward S D, Lane M D, Hayward G S. Cell cycle arrest by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus replication-associated protein is mediated at both the transcriptional and posttranslational levels by binding to CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α and p21(CIP-1) J Virol. 2003;77:8893–8914. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8893-8914.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Tang Q, Maul G G, Yuan Y. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ori-Lyt-dependent DNA replication: dual role of replication and transcription activator. J Virol. 2006;80:12171–12186. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00990-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramji D P, Foka P. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: structure, function and regulation. Biochem J. 2002;365:561–575. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csoka B, Nemeth Z H, Virag L, Gergely P, Leibovich S J, Pacher P, Sun C X, Blackburn M R, Vizi E S, Deitch E A, Hasko G. A2A adenosine receptors and C/EBPβ are crucially required for IL-10 production by macrophages exposed to Escherichia coli. Blood. 2007;110:2685–2695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-065870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh Y, Chung Y M, Clark I A, Geczy C L, Hsu K. IL-10-dependent S100A8 gene induction in monocytes/macrophages by double-stranded RNA. J Immunol. 2009;182:2258–2268. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y W, Tseng H P, Chen L C, Chen B K, Chang W C. Functional cooperation of simian virus 40 promoter factor 1 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β and δ in lipopolysaccharide-induced gene activation of IL-10 in mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 2003;171:821–828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descombes P, Schibler U. A liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein, LAP, and a transcriptional inhibitory protein, LIP, are translated from the same mRNA. Cell. 1991;67:569–579. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarwood S J, Borland G, Sands W A, Palmer T M. Identification of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins as exchange protein activated by cAMP-activated transcription factors that mediate the induction of the SOCS-3 gene. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6843–6853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler H G, Meyer C, Gaidano G, Carbone A. Constitutive cytokine production by primary effusion (body cavity-based) lymphoma-derived cell lines. Leukemia. 1999;13:634–640. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarasinghe R, Tailor P, Tamura T, Kaisho T, Akira S, Ozato K. Induction of an anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, in dendritic cells after Toll-like receptor signaling. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:893–900. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corinti S, Albanesi C, la Sala A, Pastore S, Girolomoni G. Regulatory activity of autocrine IL-10 on dendritic cell functions. J Immunol. 2001;166:4312–4318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T R. Properties and functions of interleukin-10. Adv Immunol. 1994;56:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K W, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman R L, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson M B, Langley R R, Fidler I J. Interleukin-6, secreted by human ovarian carcinoma cells, is a potent proangiogenic cytokine. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10794–10800. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S P, Wu M S, Shun C T, Wang H P, Lin M T, Kuo M L, Lin J T. Interleukin-6 increases vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis in gastric carcinoma. J Biomed Sci. 2004;11:517–527. doi: 10.1007/BF02256101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee S H, Chu C Y, Chiu H C, Huang Y L, Tsai W L, Liao Y H, Kuo M L. Interleukin-6 induced basic fibroblast growth factor-dependent angiogenesis in basal cell carcinoma cell line via JAK/STAT3 and PI3-kinase/Akt pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:1169–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]